Abstract

Recovery of liver mass to a healthy liver donor by compensatory regeneration after partial hepatectomy (PH) is a prerequisite for liver transplantation. Synchronized cell cycle reentry of the existing hepatocytes after PH is seemingly a hallmark of liver compensatory regeneration. Although the molecular control of the PH-triggered cell cycle reentry has been extensively studied, little is known about how the synchronization is achieved after PH. The nucleolus-localized protein cleavage complex formed by the nucleolar protein Digestive-organ expansion factor (Def) and cysteine proteinase Calpain 3 (Capn3) has been implicated to control wounding healing during liver regeneration through selectively cleaving the tumor suppressor p53 in the nucleolus. However, whether the Def-Capn3 complex participates in regulating the synchronization of cell cycle reentry after PH is unknown. In this report, we generated a zebrafish capn3b null mutant (capn3b∆19∆14). The homozygous mutant was viable and fertile, but suffered from a delayed liver regeneration after PH. Delayed liver regeneration in capn3b∆19∆14 was due to disruption of synchronized cell proliferation after PH. Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of nuclear proteins revealed that a number of negative regulators of cell cycle are accumulated in the capn3b∆19∆14 liver after PH. Moreover, we demonstrated that Check-point kinase 1 (Chk1) and Wee1, two key negative regulators of G2 to M transition, are substrates of Capn3. We also demonstrated that Chk1 and Wee1 were abnormally accumulated in the nucleoli of amputated capn3b∆19∆14 liver. In conclusion, our findings suggest that the nucleolar-localized Def-Capn3 complex acts as a novel regulatory pathway for the synchronization of cell cycle reentry, at least partially, through inactivating Chk1 and Wee1 during liver regeneration after PH.

Keywords: Def, Capn3; Chk1; Wee1; Nucleolus; Cell cycle; Liver regeneration; Partial hepatectomy; Zebrafish

Background

Liver regeneration after PH is an outstanding model to study the synchronization of cell cycle reentry and progression of cell cycle because a seemingly synchronized hepatocyte proliferation is induced after PH (Mao et al. 2014; Kan et al. 2009; Goessling et al. 2008; Michalopoulos 2007; Fausto et al. 2006). Previous reports have shown that in mice, DNA replication peaks at certain time point, and the reentry into mitosis is further controlled by circadian clock, probably through G2-M check point protein kinase Wee1, a downstream effector of Chk1, thus ensures the synchronization of cell cycle progression (Schibler 2003; Matsuo et al. 2003). However, the exact regulatory mechanism of cell cycle synchronization is not well established.

Nucleolus is the subcellular organelle primarily responsible for ribosome synthesis in an eukaryotic cell (Boisvert et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2012). However, studies have shown that 70% of the nucleolar proteins are unrelated to ribosome biogenesis (Ahmad et al. 2009). These proteins and even some of those involved in ribosome production have been shown to participate in cellular processes such as cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, cell senescence and apoptosis (Diesch et al. 2014). Moreover, increasing evidence has demonstrated that certain proteins tend to accumulate in the nucleoli under stress conditions, indicating the importance of nucleolus in regulating protein homeostasis (Frottin et al. 2019). As an evidence supporting this point, we recently demonstrated that the nucleolar protein Def recruits cysteine protease Capn3 (Capn3b in zebrafish) into the nucleolus to form the Def-Capn3 complex. This complex specifically mediates the cleavage of its downstream substrates including the tumor suppressor p53 to regulate cell cycle progression and liver development (Tao et al. 2013; Guan et al. 2016). Therefore, the turnover of p53 is not only controlled by the proteasome-dependent pathway (Tai and Benchimol 2009) but also a proteasome-independent pathway mediated by the Def-Capn3 complex (Tao et al. 2013; Guan et al. 2016). Interestingly, Def-Capn3 also cleaves the ribosome biogenesis factor Mpp10 to regulate the small subunit assembly (Zhao et al. 2019). However, whether the Def-Capn3 complex regulates cell cycle progression by targeting other key factors is still largely unknown.

We previously reported that def+/− mutant liver formed a scar at the amputation site after PH due to the activation of constitutive inflammatory response mediated by p53 and its downstream gene HMGB1 (Zhu et al. 2014). Over-inflammatory response activates the TGF-β signaling which finally leads to fibrosis at the wounding site (Zhu et al. 2014). However, whether the Def-Capn3 complex participates in regulating the cell cycle synchronization after PH is unknown. In this report, based on studying a zebrafish capn3b null mutant (capn3b∆19∆14), we found that the capn3b∆19∆14 mutant suffered from a delayed liver regeneration due to disruption of the synchronized cell proliferation after PH. Proteomics data revealed that some negative regulators of cell cycle are accumulated in the capn3b∆19∆14 liver after PH. Molecular analysis showed that Chk1 and Wee1 are abnormally accumulated in the nucleoli of the amputated capn3b∆19∆14 liver. Biochemical study demonstrated that Chk1 and Wee1 are the substrates of Capn3. These data suggest that the Def-Capn3 complex plays an important role in regulating liver regeneration after PH.

Methods

Zebrafish lines and maintenance

Zebrafish wild-type (WT) and all relevant mutants used in this study were in the AB background. The zebrafish def−/− (defhi429) mutant line was as previously described (Chen et al. 2005). capn3b∆19 mutant was generated using transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN) technique with strand sequences capn3b-TAL(R) GGCAGAAGAACAGAAGT and capn3b-TAL(L) AACTCACTGAAGCTGCTCCGC. In the capn3b∆19 genetic background, CRISPR-Cas9 technology was adopted to generate the capn3b∆19∆14 mutant using a specific gRNA (5′-GAATGATGTCATCCTGAAGAGG-3′) against the 3rd exon of the capn3b gene. Fish were raised and maintained according to the standard procedure recommended at http://zfin.org/.

Plasmid construction, mRNA synthesis, mRNA injection and western blot analysis

The construction of the HA-p53R143H and Myc-def plasmids has been described previously (Tao et al. 2013). The chk1 and wee1 full length cDNAs derived from the total RNA extracted from 12 h post-fertilization (hpf) zebrafish embryos were cloned into the pCS2+ vector with an HA-tag, respectively, using primers as listed in Table S1. HA-chk1Δ and HA-wee1S44A was constructed through site-directed mutagenesis using the primer pairs listed in Table S1 (Watanabe et al. 2004a). For mRNA injection, mRNAs were synthesized in vitro using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kit (Ambion). The methods for protein extraction from zebrafish embryos and western blot analysis were as described previously (Chen et al. 2005; Gong et al. 2015).

Whole-mount RNA in situ hybridization (WISH) and liver size measurement

For WISH, Digoxigenin (DIG) (Roche Diagnostics) was used to label the liver fatty acid binding protein (fabp10a) and trypsin probes as previously described (Zhao et al. 2019). WISH performance and liver size measurement were performed as described previously (Chen et al. 2005; Lo et al. 2003).

PH and measurement of the liver versus body ratio (LBR)

Fish of different ages were used for PH. The PH and measurement of the LBR were as described previously (Kan et al. 2009) The survival rates of the wild-type (WT) and capn3b∆19∆14 fish after surgery were greater than 95% after PH in all of the experiments described in this report.

Cryosectioning and immunofluorescent staining

Zebrafish cryosections were prepared as described previously (Guan et al. 2016). Antibodies against Fibrillarin (Abcam, ab4566, 1:600), zebrafish Bhmt (1:200) (Gao et al. 2018), Capn3b(1:200) (mouse monoclonal antibody, generated by Abmart), Chk1 and Wee1 (1:200) (rabbit polyclonal antibodies, generated by Hangzhou Hua-An Biotechnology Company) were used for immunostaining. After tissue sectioning and storing at − 80 °C, the cryosections were rehydrated with two washes of PBS-triton (PBS plus 0.2% Triton X-100) for 5 min (min) each. For the staining of nucleolar proteins, cryosections were incubated in 0.01 M Sodium Citrate for 5 min at 95-100oC. After cooling down to room temperature, cryosections were washed twice with PBB-triton (PBS-triton plus 0.5% BSA). The sections were then blocked by 20% goat serum in PBB-triton for 1 h (hr) at room temperature. After a brief wash with PBB, the sections were incubated overnight with primary antibody at the desired concentration diluted in PBB-triton 4 °C. After 3 washes with PBB-triton, sections were incubated with secondary antibodies (1:500) and DAPI (1:800) in PBB-triton for 1 h. After 3 washes with PBB-triton, the sections were finally mounted in 80% glycerol and covered with cover-slip for image acquisition under a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000).

EdU incorporation assay

EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine,1 nl, 10 mM) was injected into the abdominal cavity of an adult fish (0.5 mg EdU /0.1 g body weight). 24 h after injection, the fish were fixed in 4% PFA for 12 h before proceeding to cryosectioning. Incorporated EdU was detected by Alexa Fluor 488 Azide (Life Technologies, A10266) under a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000).

Nuclei isolation and nuclear protein extraction

Zebrafish liver dissection and nuclei isolation was as described (Guan et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2019). The liver tissue of zebrafish was carefully dissected under a pose microscope and put into pre-cooled low permeability solution buffer A (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT) for 20 min on ice. The liver cells were dispersed by repeated pipetting using a 5 mL pipette. The dispersed cells were homogenized manually using a glass pestle and centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet (nuclei) was resuspended with buffer A followed by another centrifugation at 2000 g for 10 min at 4 °Cfor removing the lipid layer. The pellet was resuspended and then loaded to a 40μmcell strainer (Sangon Biotech F613461) for removing remaining tissue mass. The collected flow through solution mainly contained nuclei (approximately 90%) judged from examining the solution under a microscope (Olympus U-tv0.63XC). The isolated nuclei were centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min at 4 °C and were ruptured by sonicating for fifteen 5-seocnds (5-s) bursts (with 15-s intervals between bursts) at 40% amplitude in IP lysis buffer (containing ‘cell lysis buffer for Western and IP’ and 1 × cOmplete) containing 1.5% SDS. After centrifugation at 12000 g for 15 min, the supernatant was collected and boiled at 100 °C for 10 min and then subjected to mass spectrometry (MS) analysis.

Protein digestion, TMT-labelling, RP-HPLC, LC-MS and data analysis

For MS samples preparation, the lysates (200 μg protein for each sample) were reduced with 100 mM DTT at 37 °C for 1 h (h). After reduced, the lysates were transferred to the Microcon YM-30 centrifugal filter units ((EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA), and replaced with 200ul UA (8 M Urea, 100 mM Tris. Cl pH 8.5) twice. After buffer replaced, the proteins were alkylated with 55 mM iodoacetamide (IAA, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) in UA at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. The UA buffer was then replaced with 0.1 M triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO), and digested with sequencing grade trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) (1:50 (w: w)) at 37 °C overnight. The resultant tryptic peptides were labeled with acetonitrile-dissolved TMT reagents (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) by incubation at room temperature in dark for 2 h. The labeling reaction was stopped by 5% hydroxylamine, and equal amount of labeled samples were mixed together. Offline basic RP-HPLC was performed using a Waters e2695 separations HPLC system coupled with a phenomenex gemini-NX 5u C18 column (250 × 3.0 mm, 110 Å) (Torrance, CA, USA). The sample was separated with a 97 min basic RP-LC gradient as previously described. A flow rate of 0.4 mL/min was used for the entire LC separation. The separated samples were collected into 10 fractions, and completely dried with a SpeedVac concentrator and stored at − 20 °C for further analysis. After desalted by StageTip, the peptides were re-suspended in 0.1% formic acid (FA) and analyzed by a LTQ Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL Waltham, MA) coupled online to an Easy-nLC 1000 in the data-dependent mode. The LC was run with mobile phases containing buffer A (0.1% FA) and buffer B (100% ACN, 0.1% FA). The peptides were separated by a capillary analytic column (length: 25 cm, inner diameter: 150 μm) packed with C18 particles (diameter: 1.9 μm) in a 90-min non-linear gradient (3%–8% B for 10 min, 8%–20% B for 60 min, 20%–30% B for 8 min, 30%–100% B for 2 min, and 100% B for 10 min) with a flow rate of 600 nl/min. The positive ion mode was used for MS measurements, and the spectra were acquired across the mass range of 300–1800 m/z. Higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) was used to fragment the fifteen most intense ions from each MS scan.

For analyzing the LC-MS data, the database search was performed for all raw MS files using the software MaxQuant (version 1.6). The Danio rerio proteome sequence database downloaded from Uniprot was applied to searching the data. The parameters used for the database search were set up as follows: The type of search: MS2; The protease used for protein digestion: trypsin; The type of isobaric labels: 6-plex TMT; The minimum reporter parent ion interference (PIF): 0.75; The minimum score for unmodified peptides: 15. Default values were used for all other parameters. Only proteins with no less than two quantified peptides were used for further analysis. DAVID Bioinformatics Database (v6.7) was used to identify proteins for most enriched GO term.

Statistical analysis

For statistic analysis, comparisons were made using the Student’s t-test assuming a two-tailed distribution, with significance being defined as p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.001 (***), no significance (NS).

Results

capn3b mutant is defective in liver development under stress conditions

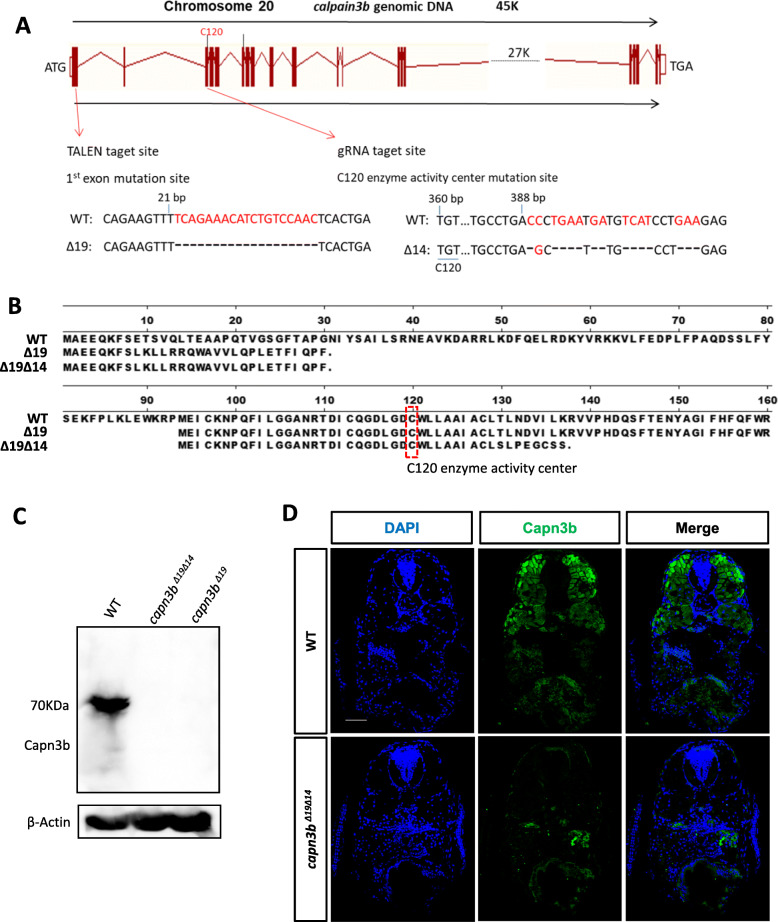

The transcript of the capn3b∆19 mutant gene (harboring a 19 bp deletion in the exon1) (Fig. 1a) is predicted to encode a 30 amino acids (aa) long peptide containing the N-terminal 8aa of Capn3b and additional 22aa (Fig. 1b). However, there is another ATG after the capn3b∆19 mutation which might serve as an alternative translation start codon to encode a Capn3b variant with truncation of the N-terminal 93aa (Figure S1B). To avoid the production of this variant (Tao et al. 2013; Sorimachi et al. 1993; Ono et al. 2016), we designed a gRNA targeting the exon3 in the background of capn3b∆19. The new mutant now carried a 14 bp-deletion in the exon3 in addition to the 19 bp-deletion in the exon1 (designated as capn3b∆19∆14) (Fig. 1a). The 14 bp-deletion in capn3b∆19∆14 disrupted the putative variant (Fig. 1b), (Zhao et al. 2019). Protein analysis showed that both 5dpf-old capn3b∆19 and capn3b∆19∆14 embryos lacked Capn3b (Fig. 1c), (Zhao et al. 2019). In mouse and human, Capn3 is mainly expressed in the muscle (Kramerova et al. 2008; Ono et al. 2006; Richard et al. 1995). Immunostaining of Capn3b protein showed that zebrafish Capn3b was highly expressed in the muscle and was also detected in other organ/tissues in WT. As expected, Capn3b was undetectable in the capn3b∆19∆14 embryos at 5dpf (Fig. 1d), demonstrating that capn3b∆19∆14 is a null mutation.

Fig. 1.

Generation of capn3b null mutant allele. a Generation of the capn3bΔ19Δ14 mutant allele. Upper panel: diagram showing the genomic structure of the zebrafish capn3b gene and the two mutated sites in capn3bΔ19Δ14 generated by TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9 approaches, respectively. Vertical bar: exon; line connecting vertical bar: intron. Lower panel: highlighting the 19 bp deletion (red letters) in 1st exon generated by the TALEN approach (on the left) and 14 bps deletion (red letters) in 3rd exon by the CRISPR-Cas9 approach (on the right), respectively. The position of nucleotide in the capn3b open reading frame (ORF) from the translation start codon ATG is provided. C120, Capn3b activity center. b Predicted peptide encoded by the capn3bΔ19 (∆19) and capn3bΔ19Δ14 (Δ19Δ14) mutant mRNA, respectively. The Δ19 mutation leads to an early stop codon in the capn3b ORF and resulted in a 30 amino acids (aa) long polypeptide, however, the Δ19 mutation potentially allows the ATG codon encoding M94 residue of WT Capn3b to be used as an alternative translation start codon to translate an N-terminus truncated peptide which harbors the activity center C120. The Δ19Δ14 mutation creates a new early stop codon in the presumed variant initiated from M94 after C120, therefore, capn3bΔ19Δ14 is likely a null allele. c Western blotting analysis of Capn3b in WT, capn3b capn3bΔ19Δ14, capn3bΔ19 at 5dpf. β-Actin: loading control. d Immunostaining of Capn3b in WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 mutant embryos at 5dpf. Scale bar: 50 μm

Similar to capn3 knockout (KO) mice (Kramerova et al. 2004), capn3b∆19∆14 mutant were viable and fertile. We compared the liver development between WT and capn3b∆19∆14 in different rearing density by WISH using the liver marker fabp10a (Ribas et al. 2017). When grown at a lower density (60 embryos/9 cm-diametre dish), the size of the capn3b∆19∆14 liver was significantly smaller than that of WT at both 3dpf and 5dpf (Fig. 2a, left panel). Surprisingly, when grown at a higher density (120 embryos/9 cm-diametre dish), the size of the capn3b∆19∆14 liver was significantly larger than that of WT at both 3dpf and 5dpf (Fig. 2a, right panel). Interestingly, it appeared that the development of the WT liver but not the capn3b∆19∆14 liver was more sensitive to the condition of higher rearing density (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Defective development of capn3b mutant zebrafish under environment stress. a, b WISH using the fabp10a probe on 3dpf- and 5dpf-old WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 embryos grown at the low (60 embryo/dish) (left panel) and high (120cm2/dish) (right panel) rearing density in a 9 cm-diameter dish (a). In (b), the data of liver sizes were compared between 3dpf- and 5dpf-old WT or between 3dpf- and 5dpf-old capn3bΔ19Δ14 mutant embryos under low (L) and high (H) rearing intensity. c WISH using the fabp10a and trypsin probes on WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 embryos at 2dpf and 3dpf. Embryos were shifted to 34.5 °C at 12 hpf till the time of sample harvesting. Numerator/denominator: number of embryos displayed the shown phenotype over total number of genotyped embryos. d Photo images showing the curved body phenotype displayed by the 3dpf-old capn3bΔ19Δ14 mutant but not WT embryos grown at 34.5 °C. e Body lengths of 6-, 8- and 12-months-old WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 fish. f LBR of 6- and 12-months-old WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 fish. Student’s T-test for statistical analyses, *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001

Next, we grew WT and capn3b∆19∆14 zebrafish embryos under a higher temperature (34.5 °C) from 12hpf. WISH using fabp10a and exocrine pancreatic marker trypsin showed that the development of both liver and exocrine pancreas in the capn3b∆19∆14 embryos were severely retarded at 2dpf, however, were surprisingly recovered at 3dpf (Fig. 2c). Moreover, at 3dpf, high temperature-treated capn3b∆19∆14 embryos had curved body (Fig. 2d), which is likely associated with the role of Capn3 in the muscle (Richard et al. 1995; Kramerova et al. 2004).

capn3b mutant exhibits shortened body length and alteration in the liver to body ratio

We noticed that the capn3b∆19∆14 adult fish is smaller than the WT control fish. Indeed, measurement of the body lengths showed that the WT fish continued to grow from 6 months (average 31.38 mm) to 8 months (average 32.04 mm) and to 12 months (average 33.71 cm) (Fig. 2e). In contrast, the growth of capn3b∆19∆14 fish was obviously retarded from 6 months (30.58 mm) to 8 months (29.58 mm) and 12 months (29.59 mm) (Fig. 2e). LBR is relatively constant in zebrafish (Kan et al. 2009; Zhu et al. 2014). We checked the LBR of adult WT and capn3b∆19∆14 fish. LBR in WT did not show significant difference between 6 and 12 months (Fig. 2f). In contrast, the capn3b∆19∆14 fish exhibited a higher LBR at 12 months than 6 months (Fig. 2f), probably due to shortened body length or failure in maintaining the liver homeostasis. Taken together, these results showed that, as the capn3-KO mice (Kramerova et al. 2004), the growth of capn3b∆19∆14 fish is sensitive to environmental stresses.

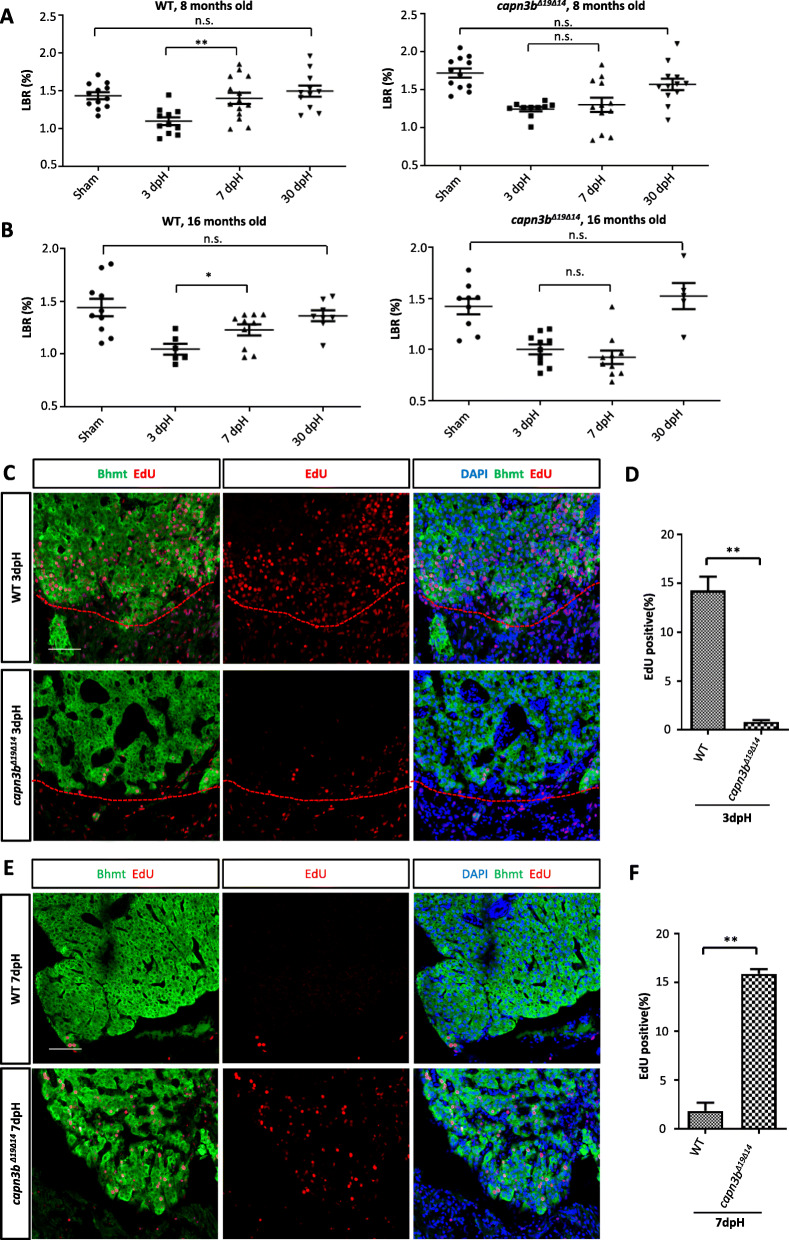

capn3b mutant suffers from delayed liver regeneration due to delayed cell proliferation after PH

Adult zebrafish liver comprises two dorsal lobes and one ventral lobe (Kan et al. 2009; Zhu et al. 2014). Previous reports have shown that, in zebrafish, hepatocyte proliferation starts in 2-3 days after resecting almost the entire ventral lobe (~ 40% of the liver mass) and that the liver weight can be fully restored within 7 days post hepatectomy (dpH) (Kan et al. 2009; Zhu et al. 2014). We conducted PH on the ventral lobe (applied in all PH in this work) on 8-months-old adult WT and capn3b∆19∆14 fish. The sham group only had their abdominal skin cut through. LBR was used to evaluate liver regeneration. We examined zebrafish at 3dpH, 7dpH and 30dpH and found that LBR was recovered within 7dpH in the WT group (Fig. 3a, left panel). In contrast, the LBR failed to be fully restored at 7dpH but was restored to the normal at 30dpH in capn3b∆19∆14 fish (Fig. 3a, right panel). We also performed PH in 16-months-old fish and found that the LBR in WT was largely restored at 7dpH and was fully restored to the normal at 30dpH (Fig. 3b, left panel). For the 16-months-old capn3b∆19∆14 fish, as for the 8-months-old fish, the LBR was not restored at 7dpH but regained their LBR at 30dpH (Fig. 3b, right panel). Taken together, the data demonstrated that capn3b∆19∆14 fish was delayed in liver regeneration after PH.

Fig. 3.

Delayed hepatocyte proliferation in capn3bΔ19Δ14 at the resection site after PH. a, b Comparison of LBRs at 3-, 7- and 30-dpH in WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 fish operated at the age of 8-months-old (a) or16-months-old (b). Sham control: cut through the abdominal skin only. c-f Co-staining of EdU and Bhmt (liver marker) at the wounding site of the liver in WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 fish at 3dpH (c) and 7dpH (e). Red dashed line: outlining the cutting site. DAPI: staining nuclei. Scale bar: 50 μm. Corresponding statistical data of the EdU-positive cells were provided (d, 3dpH; f, 7dpH). EdU was injected 24 h before harvesting at 3dpH or 7dpH. Three sections per fish and total three fish were evaluated for each genotype in each case. Student’s T-test for statistical analyses, *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01

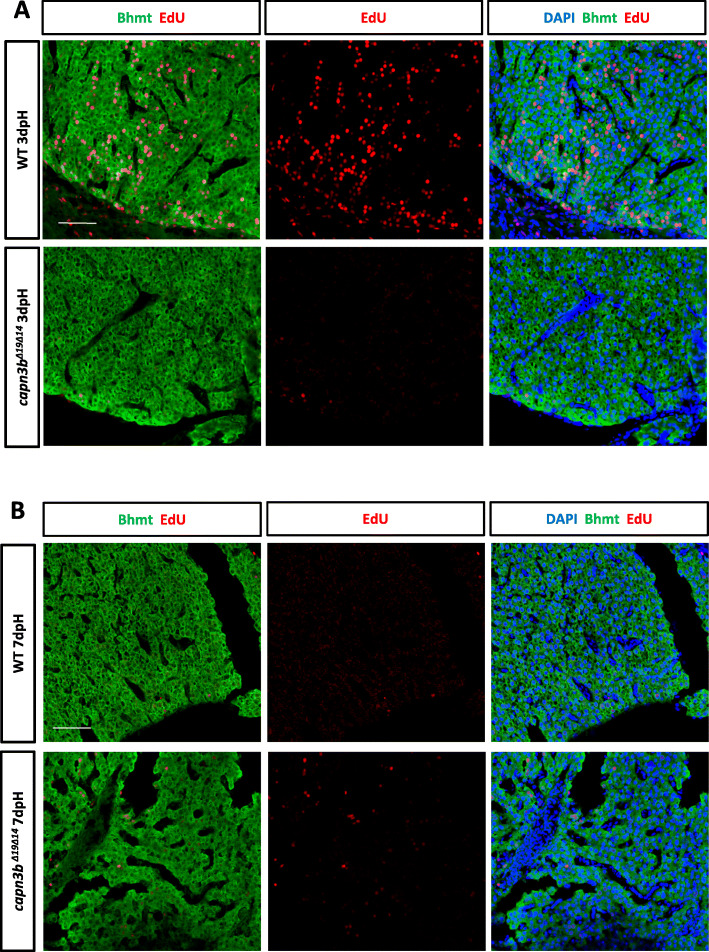

We examined cell proliferation in the amputated region by abdominally injecting EdU into the amputated WT and capn3b∆19∆14 fish at 2dpH and harvested the liver at 3dpH for staining of EdU and Bhmt (marker for hepatocytes). We calculated the EdU-positive cells out of total DAPI-positive cells. The results showed that, as reported previously (Kan et al. 2009; Zhu et al. 2014), WT hepatocytes were actively undergoing proliferation (14.28% EdU-positive cells) at 3dpH (Fig. 3c, d). In contrast, the capn3b∆19∆14 liver had very few EdU-positive cells (0.81%) at 3dpH (Fig. 3c, d). We also found that the proliferation of hepatocytes was active in the deeper region (away from the amputated site) in WT but not in capn3b∆19∆14 PH-liver at 3dpH (Fig. 4a). Therefore, cell cycle reentry in both amputated and deeper region in capn3b∆19∆14 fish was arrested/delayed at 3dpH.

Fig. 4.

Delayed hepatocyte proliferation in capn3bΔ19Δ14 in the deeper region after PH. a, b Co-staining of EdU and Bhmt (hepatocyte marker) for analyzing proliferating hepatocytes in the deeper region away from the amputated site in WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 at 3dpH (a) and 7dpH (b). DAPI: staining nuclei

Next, we injected EdU at 6dpH and harvested the liver at 7dpH. There were almost no proliferating hepatocytes in WT both in the amputated (1.86%) (Fig. 3e, f) and deeper region (Fig. 4b), demonstrating the completion of liver regeneration at 7dpH. On the other hand, in capn3b∆19∆14 fish, proliferation of hepatocytes seemingly has just begun in the amputated region (15.88% EdU-positive cells) (Fig. 3e, f). Intriguingly, in the deeper region, cell proliferation seemingly has not yet fully activated in capn3b∆19∆14 fish (Fig. 4b). Whether cell proliferation would be activated later in the deeper region remains unknown. Therefore, cell cycle reentry was not only delayed but also unsynchronized in capn3b∆19∆14 after PH.

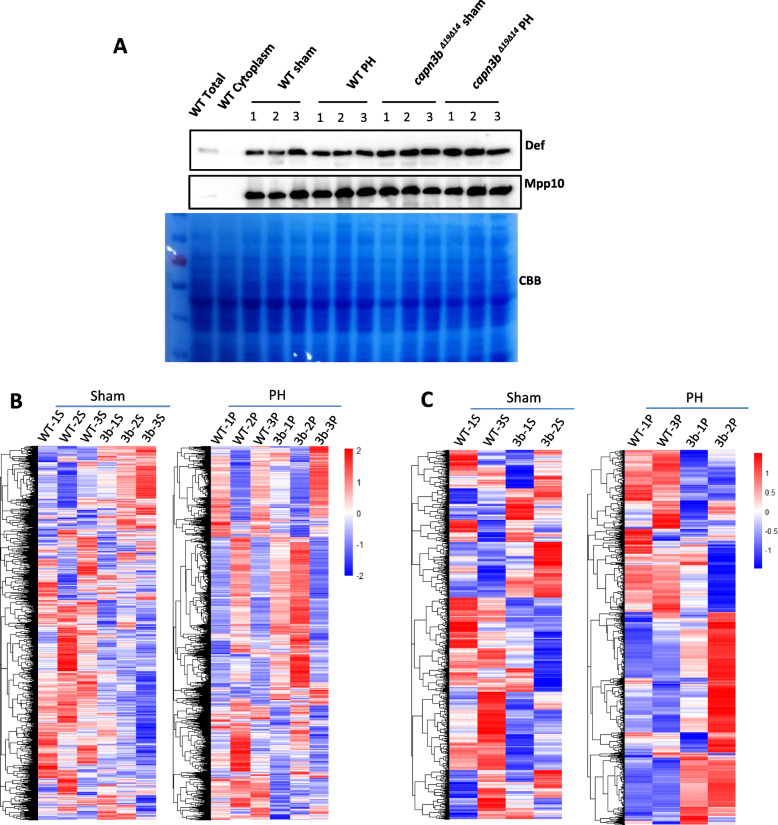

Proteome analysis reveals the involvement of cell cycle negative regulators in early regeneration of capn3b∆19∆14 liver after PH

We previously showed that the Def-Capn3 complex cleaves proteins such as p53 and Mpp10 to regulate cell cycle (Tao et al. 2013; Guan et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2019). To determine the proteins involved in the delay of capn3b∆19∆14 liver regeneration, we isolated liver nuclei from WT sham, capn3b∆19∆14 sham, WT PH, and capn3b∆19∆14 PH fish (each with three repeats, each repeat containing 8 male fish) at 3dpH for protein extraction. All nuclear protein samples were enriched with nucleolar proteins Def and Mpp10 when compared with the total protein extract and cytoplasmic protein fraction from WT livers (Fig. 5a). Total nuclear proteins were subjected to MS analysis (Table S2 and S3). Heat map clustering analysis of the MS data showed that three WT sham samples were clearly distinctive from three capn3b∆19∆14 sham samples (Fig. 5b, left panel). The MS data from two WT PH samples (WT-1P and WT-3P) were clearly distinctive from two capn3b∆19∆14 PH samples (3b-1P and 3b-2P) (Fig. 5b, right panel). We chose the best fit clustering groups (for sham samples, WT-1S, WT-3S, 3b-1S and 3b-2S were used, for PH samples, WT-1P, WT-3P, 3b-1P and 3b-2P were used) for further analysis (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Clustering analysis of the mass spectrometry data of nuclear proteins from WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 samples. a Western blot analysis of protein in the isolated nuclei from WT sham, WT PH, capn3bΔ19Δ14 sham and capn3bΔ19Δ14 PH, three repeats for each group, for each repeat the livers from eight female fish were used. b Heat map clustering analysis of three independent WT sham samples (WT-1S, WT-2S, WT-3S) and three independent capn3bΔ19Δ14 mutant sham samples (3b-1S, 3b-2S, 3b-3S) (left panel), and of three independent WT PH samples (WT-1P, WT-2P, WT-3P) and three independent capn3bΔ19Δ14 mutant PH samples (3b-1P, 3b-2P, 3b-3P) (right panel). Each repeat contained nuclear proteins extracted from 8 female fish. c Heat map clustering analysis of WT-1S, WT-3S, 3b-1S and 3b-2S (left panel), and of WT-1P, WT-3P, 3b-1P, 3b-2P (right panel)

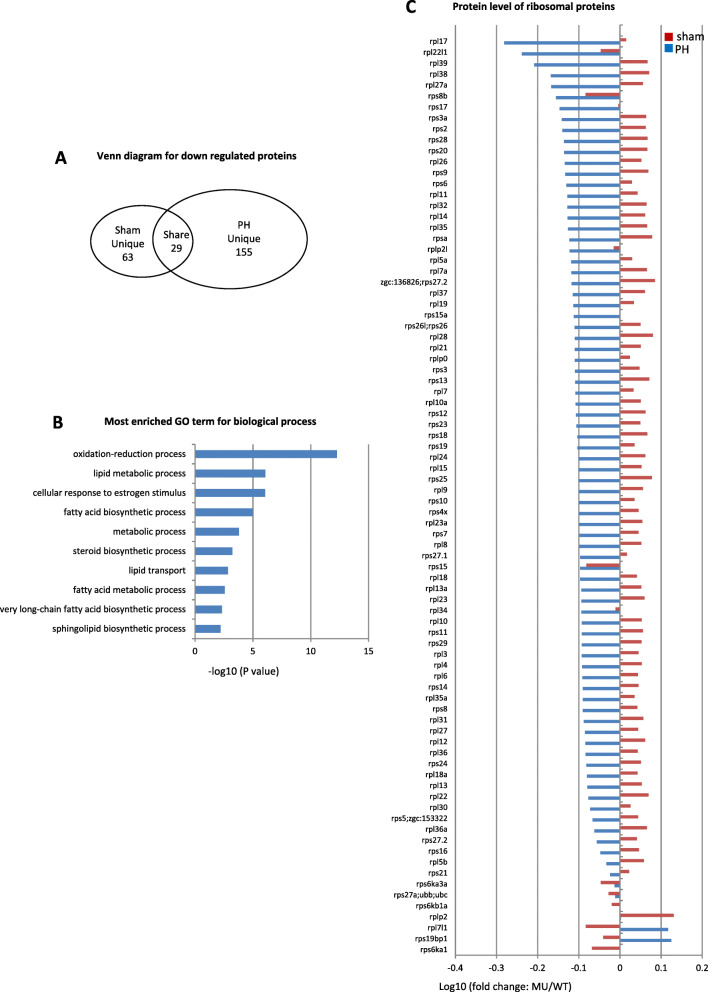

For the down-regulated proteins (cutoff value: WT verse capn3b∆19∆14 ≥ 1.45 folds), a total of 92 and 184 down-regulated proteins were identified for the capn3b∆19∆14 sham (Table S4) and PH samples (Table S5), respectively, while 29 proteins (Table S6) were shared between capn3b∆19∆14 sham and PH samples (Fig. 6a). Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the 155 proteins uniquely downregulated in capn3b∆19∆14 PH samples showed that most of the proteins were involved in metabolic and lipid biosynthesis processes in the category of biological process (Fig. 6b). Majority of ribosomal proteins were also down-regulated in capn3b∆19∆14 PH samples (Fig. 6c). Since active proliferating cells demand higher energy supply and ribosome biogenesis, these results support the observation that cell cycle reentry is not activated in capn3b∆19∆14 at 3dpH (Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Fig. 6.

Down-regulation of proteins related to lipid metabolism and ribosomal function in capn3bΔ19Δ14 at 3dpH. a Venn diagram showing the number of ‘Sham unique’, ‘PH unique’ and ‘Shared’ proteins down-regulated in capn3bΔ19Δ14 (cutoff value: WT/MU > 1.45). b Top 10 categories obtained from GO analysis of biological process for the 155 uniquely downregulated proteins in capn3bΔ19Δ14 at 3dpH. c Comparison of the change (in log10 value of the ratio of MU/WT) of 84 ribosomal proteins between the PH-group and sham-group at 3dpH

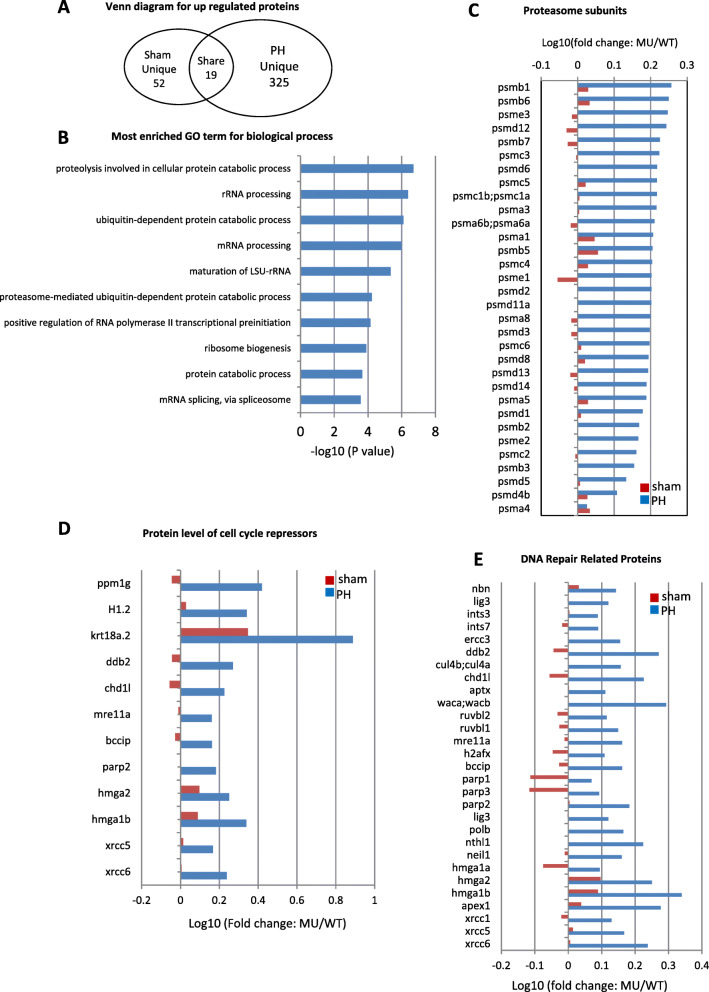

For the upregulated proteins (cutoff value: capn3b∆19∆14 verse WT ≥ 1.45 folds), a total of 71 and 344 upregulated proteins were identified in capn3b∆19∆14 sham (Table S7) and PH samples (Table S8), respectively, while 19 proteins (Table S9) were shared (Fig. 7a), suggesting that different proteomes were mobilized between WT and capn3b∆19∆14 PH samples. For 325 uniquely upregulated proteins in capn3b∆19∆14 PH samples, GO analysis showed that many proteolysis-related proteins fell into the biological process category (Fig. 7b). Further analysis of 32 26S proteasome subunits in the MS data showed that there was no significant difference between WT and mutant sham samples, however, 31 subunits were significantly accumulated in capn3b∆19∆14 PH samples (Fig. 7c). GO analysis also revealed that rRNA processing related proteins were upregulated in capn3b∆19∆14 PH samples (Fig. 7b), probably due to requirement of extra number of ribosomes for protein biosynthesis to cope with the activation of proteolysis activity in capn3b∆19∆14 PH fish. Alternatively, depletion of Capn3 might have led to accumulation of its direct or indirect targets that might act as a cue to trigger the activation of the 26S proteasome pathway.

Fig. 7.

Up-regulation of proteins related to 26S proteasome and cell cycle arrest in capn3bΔ19Δ14 at 3dpH. a Venn diagram showing the number of ‘Sham unique’, ‘PH unique’ and ‘Shared’ proteins up-regulated in capn3bΔ19Δ14 (cutoff value: MU/WT > 1.45). b Top 10 categories obtained from GO analysis of biological process for the 325 uniquely up-regulated proteins in capn3bΔ19Δ14 at 3dpH. c-e Comparison of the change (in log10 value of the ratio of MU/WT) of 32 26S proteasome subunits (c), 12 cell cycle negative regulators (d) and 29 DNA-repair related proteins (e) between the PH-group and sham-group at 3dpH

Interestingly, several negative regulators of cell cycle, including PPM1G (2.63 folds), DDB2 (1.87 folds) and H1.2 (linker histone) (2.20 folds), were found to be upregulated in capn3b∆19∆14 PH samples (Fig. 7d). PPM1G, the phosphatase of p27, functions to stabilize p27 through dephosphorylating p27 at T198 site thus to inhibit cell cycle progression (Sun et al. 2016). DDB2 is able to facilitate IR-induced phosphorylation of Chk1, thus causing cell cycle arrest (Zou et al. 2016). H1.2 augments global association of pRb with chromatin, enhances transcriptional repression by pRb, and facilitates pRb-dependent cell-cycle arrest (Munro et al. 2017). In addition, many DNA-repair related proteins were upregulated in capn3b∆19∆14 PH samples (Fig. 7e). We failed to identify cyclins and CDKs in our MS data, probably due to relatively low expression of these proteins. Therefore, the delay of cell cycle reentry in capn3b∆19∆14 PH fish is likely due to up-regulation of proteins involved in repressing cell cycle and down-regulation of proteins involved in metabolic activities.

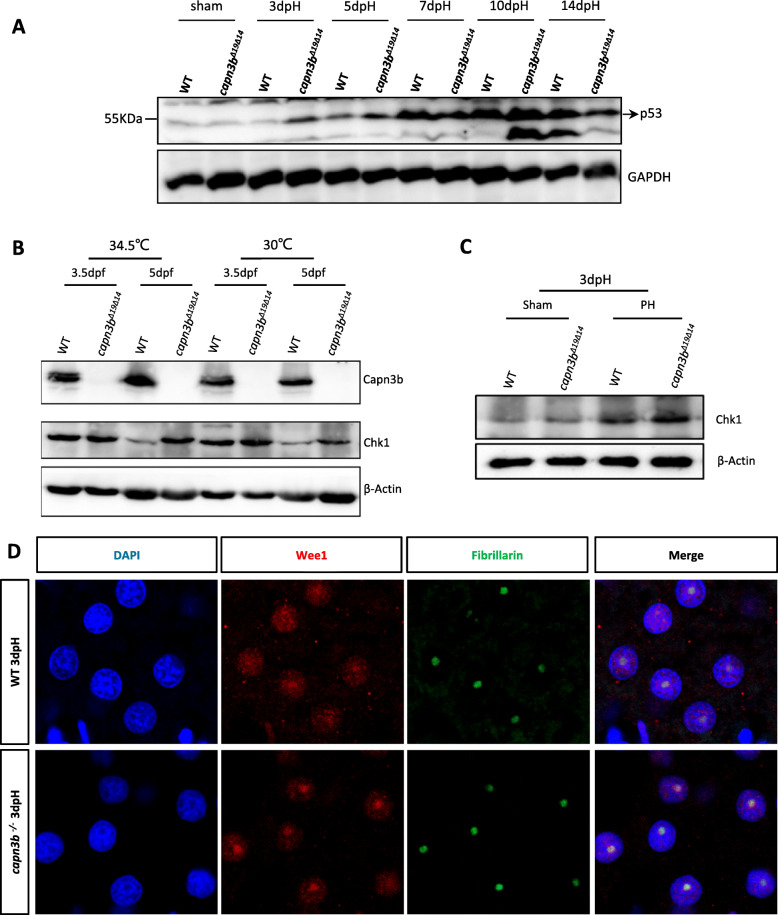

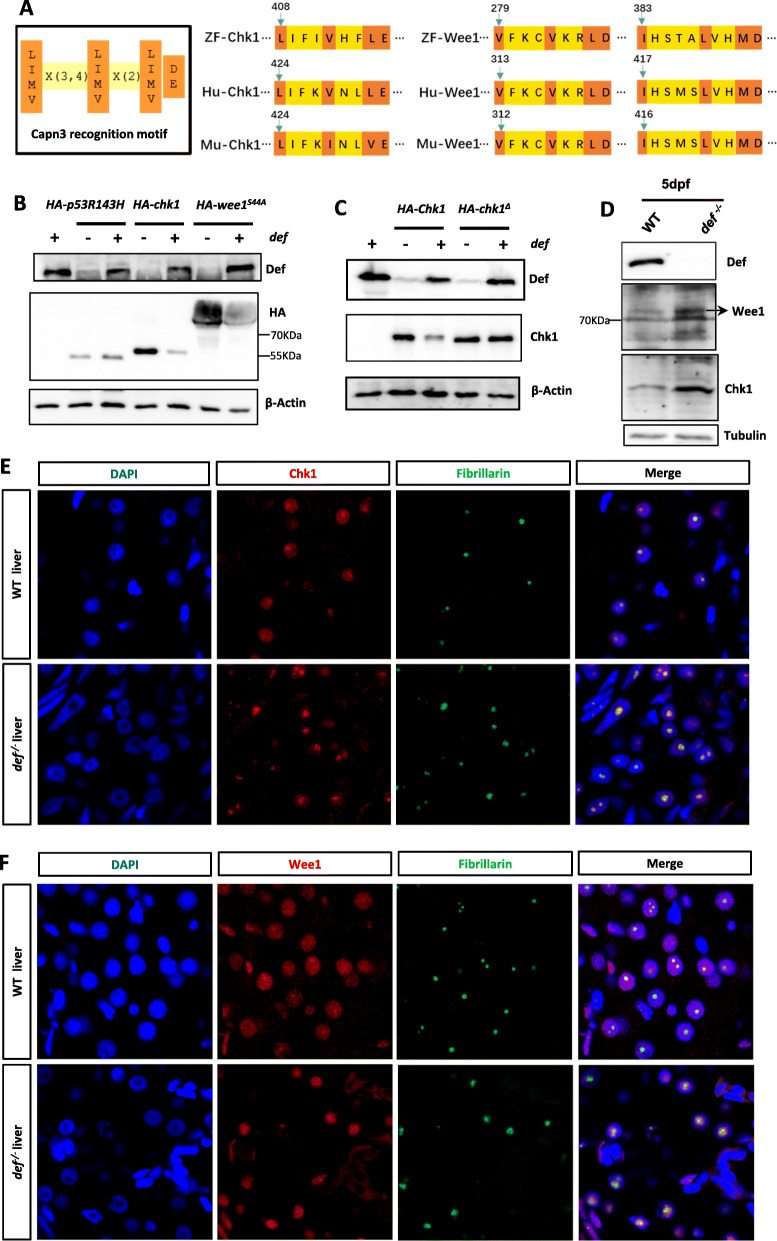

Chek1 and Wee1 are substrates of the Def-Capn3 complex

Western blot analysis showed that p53, a key negative regulator of cell cycle, was accumulated in the capn3b∆19∆14 PH samples at 3dpH (Fig. 9a). However, we could not identify p53 protein signatures in our MS data, likely due to its low expression beyond the detection limit of MS. To overcome this limitation, we sought to identify Capn3 substrates based on predicting Capn3 recognition motif [LIMV] X (Goessling et al. 2008; Michalopoulos 2007) [LIMV] X (Kan et al. 2009) [LIMV] [DE] among a group 15 of selected cell cycle related proteins (Fig. 8a, left panel; Table S10). We found that Chk1 contained one and Wee1 protein contained two Capn3 recognition motifs which are highly conserved among human, mouse and zebrafish (Fig. 8a, middle and right panels). Chk1 and Wee1 are important G2-M transition check-point proteins which can be activated by phosphorylation upon internal or external stresses (Barnum and O'Connell 2014). Previous studies of the turnover of these two proteins have mostly focused on the proteasome degradation pathway (Zhang et al. 2005; Watanabe et al. 2004b). To determine whether Chk1 and Wee1 are indeed the substrates of the Def-Capn3 complex, we co-injected different combinations of mRNA into WT embryos at the one-cell stage and extracted total proteins at 8hpf. Protein analysis showed that, as expected (Tao et al. 2013; Guan et al. 2016), the p53 mutant protein p53R143H is resistant to the Def-mediated degradation. In contrast, co-injection of chek1 or wee1S44A mRNA with def mRNA greatly downregulated the protein levels of both Chk1 and Wee1S44A (a stable form of Wee1) (Fig. 8b). We then generated a plasmid expressing a Chk1 mutant protein (Chk1Δ) in which the Capn3 recognition motif was deleted. Co-injection experiment showed that the Chk1Δ mutant protein was resistant to Def-mediated degradation (Fig. 8c).

Fig. 9.

Hepatic accumulation of Chk1 and Wee1 in capn3bΔ19Δ14 at 3dpH. a Elevation of p53 protein level in capn3bΔ19Δ14 after PH. Western blot analysis of p53 at different time point after PH as indicated. Total proteins were extracted from the liver tissues of sham, 3dpH, 5dpH, 7dpH, 10dpH and 14dpH, respectively. GAPDH, loading control. b Western blot of Capn3b and Chk1 in WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 mutant embryos at 3.5dpf and 5dpf grown at 30 °C and 34.5 °C, respectively. The embryos were shifted to 34.5 °C at 12hpf till the time of harvesting. β-Actin: loading control. c Western blot of Chk1 in WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 sham and PH groups at 3dpH group. Fibrillarin: loading control. d Co-immunostaining of Wee1 and Fibrillarin in the liver of WT and capn3bΔ19Δ14 mutant fish at 3dpH. DAPI: staining nuclei

Fig. 8.

Chk1 and Wee1 are substrates of the Def-Capn3b complex. a Diagram showing the Capn3 recognition motif (left panel) and the locations of this motif in zebrafish, human and mouse Chk1 (middle panel) and Wee1 (right panel) proteins. b, c Western blot of Def, HA-p53R143H, HA-Chk1 and HA-Wee1S44A in WT embryos injected with HA-p53R143H, HA-Chk1 or HA-Wee1S44A mRNA combined with or without def mRNA (b). Western blot of HA-Chk1 and HA-Chk1Δ in WT embryos injected with HA-Chek1or HA-Chek1Δ mRNA combined with or without def mRNA (c). Total proteins were extracted at 8-h post-injection. β-Actin: loading control. d Western blot of the endogenous Chk1 and Wee1 proteins in WT and def−/− mutant embryos at 5dpf. Tubulin: loading control. e, f Co-immunostaining of Chk1 (e) or Wee1 (F) with Fibrillarin in the liver of WT with def−/− at 5dpf. DAPI: stain nuclei

Next, we examined Chk1 and Wee1 in the def−/− mutant at 5dpf and found that both proteins were up-regulated (Fig. 8d), as did the p53 protein (Tao et al. 2013). Co-immunostaining of Fibrillarin (Fib) (a nucleolar marker) with Chk1 or Wee1 revealed that while both Chk1 and Wee1 were distributed in the nucleoplasm and nucleolus in WT these two proteins were mainly enriched in the nucleoli in the def−/− mutant (Fig. 8e, f), as did the p53 protein (Tao et al. 2013).

Capn3b depletion enhances Chk1 and Wee1 accumulation after PH

To determine the status of Chk1 in capn3b∆19∆14, we first examined the levels of Chk1 proteins in capn3b∆19∆14 embryos at 3.5dpf and 5dpf grown at 30 °C and 34.5 °C, respectively. Although no obvious difference was observed between WT and capn3b∆19∆14 embryos at 3dpf Chk1 protein was greatly accumulated in capn3b∆19∆14 embryos at 5dpf at both rearing conditions (Fig. 9b).

Next, we examined Chk1 protein in the liver of WT and capn3b∆19∆14 PH fish at 3dpH. The result showed that the expression levels of Chk1 were lower in both WT and capn3b∆19∆14 sham groups than in the livers of PH fish (Fig. 9c), suggesting that PH promotes the accumulation of Chk1. However, the liver of capn3b∆19∆14 PH fish accumulated much more Chk1 proteins than did the WT PH fish (Fig. 9c). Finally, we performed immunostaining experiment to determine the status of Wee1 protein in regenerating liver at 3dpH. We found that, in WT, Wee1 protein was distributed in the nucleus with certain degree of enrichment in the nucleolus (Fig. 9d, upper panels). In contrast, Wee1 protein was mainly accumulated in the nucleolus in the capn3b∆19∆14mutant liver at 3dpH (Fig. 9d, lower panels). These results indicate that both Chk1 and Wee1 might be, at least in part, responsible for the delayed liver regeneration in capn3b∆19∆14 PH-fish.

Discussion

We have previously proposed that the Def-Capn3 complex might serve as a nucleolar checkpoint for cell proliferation by selective inactivation of cell cycle-related substrates such as p53 during early organogenesis (Guan et al. 2016). In this report, we strengthened the above point by demonstrating that the Def-Capn3b complex is capable to cleave Chk1 and Wee1, two well-defined negative regulators of cell cycle.

In the context of liver regeneration after PH, we found that depletion of Capn3 delayed liver regeneration by disrupting the synchronization of cell cycle reentry, possibly through accumulating Chk1, Wee1, p53, PPM1G and other negative regulators. Notably, PPMG1 is known to stabilize Chk1 protein and Wee1 is a downstream effector of Chk1 (Sun et al. 2016), therefore, it is reasonable to propose that Chk1 and Wee1 likely play a key role in delaying cell proliferation during the regeneration of the capn3b∆19∆14 PH-liver. The MS data showed that the levels of 31 subunits of the 26S proteasome complex were elevated in the capn3b∆19∆14 PH-liver. It is imaginable that the activated proteasome pathway could gradually degrade the accumulated negative regulators of cell cycle in the capn3b∆19∆14 PH-liver although the synchronization of cell proliferation was probably compromised. This might explain why the capn3b∆19∆14 PH-liver finally regained its mass at 30dpH.

Based on our data, we propose that PH will activate the cell cycle reentry program in hepatocytes but meanwhile will impose a restriction on cell cycle progression by triggering the expression of negative regulators of cell cycle such as p53, Chk1 and Wee1. Although these proteins are subjected to proteasome pathway mediated degradation the synchronization of cell cycle reentry is achieved by the Def-Capn3b pathway which functions to inactivate these proteins more promptly. Since the Def-Capn3b pathway mediated substrate cleavage is independent of the ubiquitination pathway we believe the Def-Capn3b pathway plays a unique function in the regulation of cell cycle progression during liver regeneration after PH. Based on the fact that the Def-Capn3 pathway also operates in human cells (Tao et al. 2013; Guan et al. 2016), it is envisaged that the Def-Capn3 pathway likely plays a role in regulating liver regeneration in mammals.

Zebrafish genome contains 19 calpain homologous genes (Tao et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2019). These calpain homologs might compensate for the loss-of-function of Capn3b in capn3b∆19∆14, which nicely explains why the capn3b∆19∆14 fish is viable and fertile (Ma et al. 2019). However, the growth of capn3b∆19∆14 fish is retarded, including a small liver at the fry stage and short body length at the adult stage. The growth retardation is exaggerated in response to environmental stresses such as high rearing intensity or high temperature. These observations suggest that gene compensation in the capn3b∆19∆14 fish is conditional. This is consistent with the observation that Def mainly recruits Capn3b but not its closer homolog Capn3a to the nucleolus (Tao et al. 2013). It would be interesting to explore the extent of gene compensation for different genes under different conditions in the future. Interestingly, the capn3b∆19∆14 fish displayed an LBR largely similar to the WT fish, suggesting that the delay of liver regeneration in capn3b∆19∆14 fish after PH is genuinely attributed to the depletion of Capn3b. Future work is required to generate capn3 KO mouse for determining whether this is also the case in mammals after PH.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. List of primers for plasmid construction.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Full MS data for six sham protein samples.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Full MS data for six PH protein samples.

Additional file 4: Table S4. 92 proteins downregulated in capn3∆14∆19 sham samples.

Additional file 5: Table S5. 184 downregulated in capn3∆14∆19 PH samples.

Additional file 6: Table S6. 29 downregulated proteins shared in capn3∆14∆19 sham and PH samples.

Additional file 7: Table S7. 71 upregulated proteins in capn3∆14∆19 sham samples.

Additional file 8: Table S8. 344 upregulated proteins in capn3∆14∆19 PH samples.

Additional file 9: Table S9. 19 upregulated proteins shared in capn3∆14∆19 sham and PH samples.

Additional file 10: Table S10. Predicting Capn3 recognition sites in cell-cycle related proteins.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jun Chen and all other members in JRP lab for their invaluable suggestions.

Abbreviations

- Capn3

Calpain3

- Chk1

Check-point kinase 1

- DDB2

DNA damage bingding protein 2

- Def

Digestive-organ expansion factor

- dpf

days-post-fertilization

- dpH

days-post-hepatectomy

- GO

Gene ontology

- fabp10a

liver fatty acid binding protein

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- PH

Partial hepatectomy

- PPM1G

Protein phosphatase 1G

- TALEN

Transcription activator-like effector nucleases

- WT

Wild-type

Authors’ contributions

FC, YCW and JRP designed the experiments. FC, DLH, HS and CG performed the zebrafish experiments. YCW performed the MS experiment. FC and JRP analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China and the Natural Science Foundation of China in the order of 2018YFA0800502, 31830113 and 2017YFA0504501.

Availability of data and materials

Dataset described in this work can be downloaded from the supplementary Tables S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9 and S10 from the journal website. Materials request should be addressed to the corresponding author: pengjr@zju.edu.cn.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were conducted according to the guidelines of “Regulation for the Use of Experimental Animals in Zhejiang Province” with a permit issued by the Animal Ethics Committee in Zhejiang University (ETHICS CODE Permit NO. ZJU2011-1-11-009Y).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Yingchun Wang, Email: ycwang@genetics.ac.cn.

Jinrong Peng, Email: pengjr@zju.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13619-020-00049-1.

References

- Ahmad Y, Boisvert FM, Gregor P, Cobley A, Lamond AI. NOPdb: Nucleolar proteome database--2008 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D181–D184. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnum KJ, O'Connell MJ. Cell cycle regulation by checkpoints. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1170:29–40. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0888-2_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert FM, van Koningsbruggen S, Navascues J, Lamond AI. The multifunctional nucleolus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:574–585. doi: 10.1038/nrm2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Ruan H, Ng SM, Gao C, Soo HM, Wu W, et al. Loss of function of def selectively up-regulates Delta113p53 expression to arrest expansion growth of digestive organs in zebrafish. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2900–2911. doi: 10.1101/gad.1366405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diesch J, Hannan RD, Sanij E. Perturbations at the ribosomal genes loci are at the Centre of cellular dysfunction and human disease. Cell Biosci. 2014;4:43. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-4-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausto N, Campbell JS, Riehle KJ. Liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2006;43:S45–S53. doi: 10.1002/hep.20969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frottin F, Schueder F, Tiwary S, Gupta R, Korner R, Schlichthaerle T, et al. The nucleolus functions as a phase-separated protein quality control compartment. Science. 2019;365:342. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw9157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C, Zhu ZH, Gao YQ, Lo LJ, Chen J, Luo LF, et al. Hepatocytes in a normal adult liver are derived solely from the embryonic hepatocytes. J Genet Genom. 2018;45:173–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goessling W, North TE, Lord AM, Ceol C, Lee S, Weidinger G, et al. APC mutant zebrafish uncover a changing temporal requirement for wnt signaling in liver development. Dev Biol. 2008;320:161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.05.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L, Gong H, Pan X, Chang C, Ou Z, Ye S, et al. p53 isoform Delta113p53/Delta133p53 promotes DNA double-strand break repair to protect cell from death and senescence in response to DNA damage. Cell Res. 2015;25:351–369. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Huang D, Chen F, Gao C, Tao T, Shi H, et al. Phosphorylation of Def regulates Nucleolar p53 turnover and cell cycle progression through Def recruitment of Calpain3. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan NG, Junghans D, Belmonte JCI. Compensatory growth mechanisms regulated by BMP and FGF signaling mediate liver regeneration in zebrafish after partial hepatectomy. FASEB J. 2009;23:3516–3525. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-131730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramerova I, Kudryashova E, Spencer MJ. Null mutation of calpain 3 (p94) in mice causes abnormal sarcomere formation in vivo and in vitro. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1373–1388. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramerova I, Kudryashova E, Wu B, Ottenheijm C, Granzier H, Spencer MJ. Novel role of calpain-3 in the triad-associated protein complex regulating calcium release in skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3271–3280. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo J, Lee SC, Xu M, Liu F, Ruan H, Eun A, et al. 15,000 unique zebrafish EST clusters and their future use in microarray for profiling gene expression patterns during embryogenesis. Genome Res. 2003;13:455–466. doi: 10.1101/gr.885403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Zhu P, Shi H, Guo L, Zhang Q, Chen Y, et al. PTC-bearing mRNA elicits a genetic compensation response via Upf3a and COMPASS components. Nature. 2019;568:259–263. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1057-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao SA, Glorioso JM, Nyberg SL. Liver regeneration. Transl Res. 2014;163:352–362. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo T, Yamaguchi S, Mitsui S, Emi A, Shimoda F, Okamura H. Control mechanism of the circadian clock for timing of cell division in vivo. Science. 2003;302:255–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1086271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalopoulos GK. Liver regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:286–300. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Hookway ES, Floderer M, Carr SM, Konietzny R, Kessler BM, et al. Linker histone H1.2 directs genome-wide chromatin Association of the Retinoblastoma Tumor Suppressor Protein and Facilitates its Function. Cell Rep. 2017;19:2193–2201. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y, Ojima K, Shinkai-Ouchi F, Hata S, Sorimachi H. An eccentric calpain, CAPN3/p94/calpain-3. Biochimie. 2016;122:169–187. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y, Torii F, Ojima K, Doi N, Yoshioka K, Kawabata Y, et al. Suppressed disassembly of autolyzing p94/CAPN3 by N2A connectin/titin in a genetic reporter system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18519–18531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas L, Valdivieso A, Diaz N, Piferrer F. Appropriate rearing density in domesticated zebrafish to avoid masculinization: links with the stress response. J Exp Biol. 2017;220:1056–1064. doi: 10.1242/jeb.144980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard I, Broux O, Allamand V, Fougerousse F, Chiannilkulchai N, Bourg N, et al. Mutations in the Proteolytic-enzyme Calpain-3 cause limb-girdle muscular-dystrophy type-2a. Cell. 1995;81:27–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schibler U. Liver regeneration clocks on. Science. 2003;302:234–235. doi: 10.1126/science.1090810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorimachi H, Toyamasorimachi N, Saido TC, Kawasaki H, Sugita H, Miyasaka M, et al. Muscle-specific Calpain, P94, is degraded by autolysis immediately after translation, resulting in disappearance from muscle. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10593–10605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Wang G, Wrighton KH, Lin H, Songyang Z, Feng XH, et al. Regulation of p27(Kip1) phosphorylation and G1 cell cycle progression by protein phosphatase PPM1G. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6:2207–2220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai E, Benchimol S. TRIMming p53 for ubiquitination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11431–11432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905997106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao T, Shi H, Guan Y, Huang D, Chen Y, Lane DP, et al. Def defines a conserved nucleolar pathway that leads p53 to proteasome-independent degradation. Cell Res. 2013;23:620–634. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Luo Y, Hong YH, Peng JR, Lo LJ. Ribosome biogenesis factor Bms1-like is essential for liver development in Zebrafish. J Genet Genom. 2012;39:451–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Arai H, Nishihara Y, Taniguchi M, Watanabe N, Hunter T, et al. M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCFbeta-TrCP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Arai H, Nishihara Y, Taniguchi M, Watanabe N, Hunter T, et al. M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCF beta-TrCP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YW, Otterness DM, Chiang GG, Xie W, Liu YC, Mercurio F, et al. Genotoxic stress targets human Chk1 for degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Mol Cell. 2005;19:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Chen Y, Chen F, Huang D, Shi H, Lo LJ, et al. Sas10 controls ribosome biogenesis by stabilizing Mpp10 and delivering the Mpp10-Imp3-Imp4 complex to nucleolus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:2996–3012. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Chen J, Xiong JW, Peng J. Haploinsufficiency of Def activates p53-dependent TGFbeta signalling and causes scar formation after partial hepatectomy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou N, Xie G, Cui T, Srivastava AK, Qu M, Yang L, et al. DDB2 increases radioresistance of NSCLC cells by enhancing DNA damage responses. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:14183–14191. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5203-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. List of primers for plasmid construction.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Full MS data for six sham protein samples.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Full MS data for six PH protein samples.

Additional file 4: Table S4. 92 proteins downregulated in capn3∆14∆19 sham samples.

Additional file 5: Table S5. 184 downregulated in capn3∆14∆19 PH samples.

Additional file 6: Table S6. 29 downregulated proteins shared in capn3∆14∆19 sham and PH samples.

Additional file 7: Table S7. 71 upregulated proteins in capn3∆14∆19 sham samples.

Additional file 8: Table S8. 344 upregulated proteins in capn3∆14∆19 PH samples.

Additional file 9: Table S9. 19 upregulated proteins shared in capn3∆14∆19 sham and PH samples.

Additional file 10: Table S10. Predicting Capn3 recognition sites in cell-cycle related proteins.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset described in this work can be downloaded from the supplementary Tables S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9 and S10 from the journal website. Materials request should be addressed to the corresponding author: pengjr@zju.edu.cn.