To the Editor,

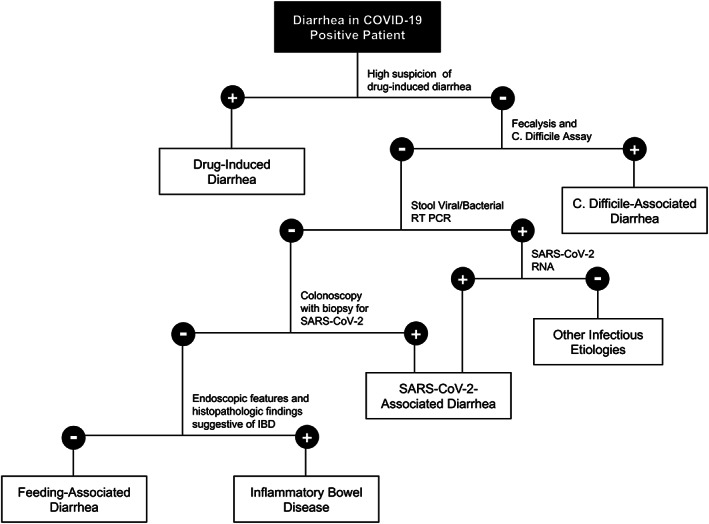

We have read with great interest the recent publication of Dr. Wong and colleagues. 1 They reviewed on different manifestations of COVID‐19 in the digestive system with diarrhea being among the more commonly presented. Since the pandemic has begun, there have been an increasing number of COVID‐19 patients reported to have such symptom. 2 We hypothesize that it might be due to the growing knowledge of GI‐related symptoms in COVID‐19, thereby resulting to higher index of suspicion. However, we aim to highlight that diarrhea can also be due to other etiologies, and negative implications in the management could occur if it is misdiagnosed as SARS‐CoV‐2‐associated right away. We also propose an algorithm in the work‐up of diarrhea in a COVID‐19 patient.

Evidence show that SARS‐CoV‐2 virus can actively infect and replicate in the GI tract through the angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors. 1 With such pathophysiologic mechanism, it is believed to disrupt the normal intestinal flora, leading to GI symptoms which include diarrhea. 3 A recent meta‐analysis of 10 676 patients with COVID‐19 have shown that diarrhea has a pooled prevalence of 7.7% (95% CI 7.2–8.2). 4 It is characterized to be more commonly non‐dehydrating, not high volume or clinically severe and typically up to thrice daily. 5 The timing of its presentation varies with 55.2% of 146 patients presenting with diarrhea after admission while 22.2% with diarrhea before diagnosis. 5 Mean duration of symptoms is 4 days and varied between 1 and 14 days.

It is important to note that the diarrhea in COVID‐19 patients is not always SARS‐CoV‐2‐associated. It can be multifactorial or of other etiologies given the patient setting of being on multiple drugs and prolonged hospitalizations. Here, we emphasize that is important to know the etiology of diarrhea as it would dictate the appropriate management (Fig. 1). Firstly, drug‐induced diarrhea is common among COVID‐19 patients as administered medications such as hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, remdesivir, and several antibiotics can cause diarrhea as their side effect. 6 It usually presents with watery stools of mild severity and resolves with the discontinuation of the offending drug. As patients are often on prolonged hospitalization, Clostridium difficile ‐associated diarrhea can also be likely. It is caused by C. difficile , an anaerobic, Gram‐positive toxigenic bacteria and can present with florid watery stools associated with abdominal cramps and fever. 7 Intake of antibiotics is also a risk factor. It is diagnosed by obtaining a C. difficile assay and treated with oral vancomycin. In pre‐pandemic studies, 60% of critically ill patients are reported to have signs of enteral feeding intolerance which can manifest as diarrhea. 8 Feeding‐associated diarrhea usually presents with watery stools after feeding, but it is recommended to rule out other etiologies first prior to its diagnosis. If the work‐up is negative and symptoms persist despite given an anti‐diarrheal agent, the feeding formula or feeding method can be changed. 9 Other infectious etiologies of diarrhea can be worked up with fecalysis and an RT‐PCR of the stool. For patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), it would be potentially difficult to determine IBD flares as the etiology of diarrhea given the endoscopy risks during the pandemic. Nevertheless, there have been reviews showing the role of fecal calprotectin to confirm intestinal inflammation and IBD flares. 10

FIGURE 1.

Proposed algorithm in the work‐up of diarrhea in a COVID‐19 positive patient.

SARS‐CoV‐2‐associated diarrhea is usually a diagnosis of exclusion unless the virus is detected in biopsy or stool specimens. 2 However, this is not readily available especially in the low‐resource settings. Currently, there is no specific treatment for SARS‐CoV‐2‐associated diarrhea, and its management is mainly based on supportive care. No evidence on the efficacy of anti‐diarrheal drugs is available, but adequate rehydration remains the cornerstone of treatment. In China, probiotics is recommended for severe COVID‐19 disease to mitigate intestinal dysbiosis and possibly reduce secondary infection. 4

While diarrhea can signal the suspicion of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, we highlight the importance of going back to the basics of right clinical judgment with the aid of available diagnostic work‐ups. As we become more vigilant in this growing pandemic, may our clinical eye not turn blind as we may miss treating the real problem after all.

Aguila, E. J. T. , Cua, I. H. Y. , and Dumagpi, J. E. L. (2020) When do you say it's SARS‐CoV‐2‐associated diarrhea?. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 35: 1652–1653. 10.1111/jgh.15141.

References

- 1. Wong SH, Lui RNS, Sung JJY. Covid‐19 and the digestive system. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020; 35: 744–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. D'Amico F, Baumgart DC, Danese S, Peyrin‐Biroulet L. Diarrhea during COVID‐19 infection: pathogenesis, epidemiology, prevention and management. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8 April 2020. 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pan L, Mu M, Ren HG et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID‐19 patients with digestive symptoms in Hubei, China: a descriptive, cross‐sectional, multicenter study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020; 115: 766–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sultan S, Altayar O, Siddique SM. AGA Institute rapid review of the GI and liver manifestations of COVID‐19, meta‐analysis of international data, and recommendations for the consultative management of patients with COVID‐19. Gastroenterology 2020. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tian Y, Rong L, Nian W, He Y. Review article: gastrointestinal features in COVID‐19 and the possibility of fecal transmission. Aliment Pharmacol Therap 2020; 51: 843–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xia L, Wu K. Gastroenterology practice in COVID‐19 pandemic. World Gastroenterol Org 2020. https://worldgastroenterology.org/publications/e-wgn/gastroenterology-practice-in-covid-19-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- 7. Starr J. Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ 2005; 331: 498–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mentec H, Dupont H, Bocchetti M, Cani P, Ponche F, Bleichner G. Upper digestive intolerance during enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: frequency, risk factors and complications. Crit. Care Med. 2001; 29: 1955–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tatsumi H. Enteral tolerance in critically ill patients. J. Intensive Care 2019; 7. 10.1186/s40560-019-0378-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mago S, Vaziri H, Tadros M. The utility of fecal calprotectin in the era of COVID‐19 pandemic. Gastroenterology 2020. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]