Abstract

Introduction:

JUUL is a closed-system e-cigarette that uses disposable pods with high concentrations of nicotine. JUUL use among youth arose exponentially since 2015, thus, it is essential to understand youths’ reasons for liking/disliking JUUL to inform the regulation of the product.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in 4 high schools in Connecticut in 2018 (N=3170). The survey assessed JUUL use in the past month and reasons for liking/disliking JUUL, which included pharmacological effects (e.g., subjective nicotine and/or flavor effects), product characteristics (e.g., flavors, nicotine, shape), peer influence (e.g., friends’ use), comparisons to other e-cigarettes (e.g., lower harm), and concealability (e.g., hide from authority).

Results:

30.2% (N=956) were past-month users who used a JUUL on an average of 13.6 days (SD=11.7; 25% reported daily use). The top reasons for liking JUUL were: “it gives me a buzz” (52%), “I like the flavors” (43%), and “my friends use it” (36%). The top reasons for disliking JUUL were: “the pods are expensive” (57%), “nicotine is too high” (20%), and “it gives me a headache” (18%). Regression models indicated that liking JUUL because of the buzz, ability to help concentrate, nicotine level, and ease of hiding it from teachers were associated with more days of use in the past month, while peer influence was negatively associated. Furthermore, disliking the high cost of pods was associated with more frequent use.

Conclusions:

Comprehensive policies that regulate device characteristics that appeal to youth (e.g., nicotine level, flavors) are needed to prevent JUUL use among youth.

Keywords: e-cigarettes, youth, regulation, prevention, appeal

1. INTRODUCTION

Youth e-cigarette use is a major public health concern (USDHHS, 2016). US national data show that past-month e-cigarette use among adolescents doubled between 2017 and 2018 (11% to 21%) (Gentzke et al., 2019). This surge in use likely is driven by the rising popularity of pod-mod devices, most notably JUUL (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2019; Vallone et al., 2018). Nielson sales data in the U.S.A. showed that the sale of JUUL comprised 29% of the total e-cigarette sales in 2017, which is the greatest market share among all e-cigarettes (King et al., 2018).

JUUL is a rechargeable, closed-system e-cigarette that uses disposable pods containing flavored e-liquids with high concentrations of nicotine salts (initially available in 5%, with 3% introduced more recently). According to Juul Labs, the nicotine in a 5% pod is comparable to one pack of cigarettes (Juul Labs, 2019). While the acute and long-term health effects of JUUL use largely remain unknown, there is significant concern about exposing youth to high nicotine concentrations through JUUL (Goniewicz et al., 2018). Nicotine adversely impacts the developing brain (Yuan et al., 2015), and youth who use high nicotine in e-cigarettes are at heightened risk of developing nicotine dependence and progressing to combustible tobacco use (Goldenson et al., 2017) or other addictive substances (England et al., 2015). Concerns also have been raised about exposure to flavor chemicals like formaldehyde and acetaldehyde through eliquids (Erythropel et al., 2019; USDHHS, 2016). Thus, there is a critical need to reduce JUUL’s youth appeal. Furthermore, the data on JUUL’s youth appeal can be used to support Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s regulatory initiatives around tobacco products, which includes JUUL (FDA, 2018).

Adults report that JUUL is appealing because of friends’ use, curiosity, similarity to cigarettes, and device features such as its small size and vapor cloud (Leavens et al., 2019; Nardone et al., 2019). However, reasons for liking or disliking JUUL have not been examined in adolescents. It has been speculated that JUUL is attractive to youth because of appealing flavors (e.g., mango, cool mint) that are available in their disposable pods and the device’s sleek design, which resembles a USB flash drive (Barrington-Trimis and Leventhal, 2018). Furthermore, youth are sharing on social media how easy it is to conceal their JUUL use in school (Allem et al., 2018), suggesting that the ability to conceal JUUL from authority figures also may appeal to youth.

In the current study, we examined the reasons for liking and disliking JUUL among adolescent JUUL users to identify factors that contribute to youth appeal. Based on prior research on both positive and negative subjective nicotine effects (Mantey et al., 2017) and appeal of e-cigarettes among youth (Kong et al., 2015; Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2019; Morean et al., 2018a), we examined several constructs including pharmacological effects (e.g., feeling of “buzz”/headrush), product characteristics (e.g., flavors, nicotine, shape/size of the device), peer influence (e.g., friends use/don’t use it), concealability (i.e., hide from parents/teachers), and comparisons to other e-cigarettes (e.g., perceived harm). We also examined whether reasons for liking and disliking JUUL were associated with JUUL use frequency (i.e., number of days of use in the past 30 days). We hypothesized that constructs for liking would be associated with more frequent JUUL use and constructs for disliking would be associated with less frequent use.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

Of the 3730 students who attended school on the days of survey administration, 3170 participants (52.4% female, mean age 15.9 [SD=1.29], 60.4% White) completed the survey (response rate 85.0%).

2.2. Procedures

The Yale School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the participating high schools approved the study. Twenty-minute anonymous, computerized surveys assessing tobacco product use were conducted in 4 high schools (spring/fall 2018) from different distinct District Reference Groups, which are school groupings based on socioeconomic status of students in Connecticut (Connecticut School Finance Project, 2016). Two weeks prior to administering the survey, information sheets describing the study’s purpose and procedures were mailed to parents/guardians, who could decline their child’s participation by contacting research/school staff (n=3 declined).

Prior to survey administration, the research staff informed students that participation was voluntary and anonymous, and survey completion was considered assent/consent. Qualtrics Surveys were administered on Samsung Galaxy tablets during health or English classes. Students received a stylus for participating.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Current JUUL use

JUUL use was assessed using a picture of a JUUL device and JUUL pods and a brief written description: “rechargeable with USB charger; has pods that insert in device.” Students were coded as “current JUUL user” if they responded to using JUUL on ≥ 1 day/past month to the question: “Approximately how many days out of the past 30 days did you use a JUUL?”

2.3.2. Reasons for liking JUUL

Reasons for liking JUUL were assessed with a question, “What do you like about using a JUUL? (Select all that apply).” Response options included items assessing 1) pharmacological effects (i.e., “It gives me a buzz”, “It helps me concentrate”, “It gives me energy”, “It helps me control my appetite”, “It helps me lose weight”); 2) positive product characteristics (i.e., “I like the flavors”, “I like the size of the JUUL”, “I like the nicotine level”, “It is easy to change pods”, “I like the shape of the JUUL”); 3) peer influence (i.e., “My friends use it”); 4) comparison to other e-cigarettes (i.e., “I believe that it’s less harmful than other e-cigarettes”, “I like that it produces less vapor than other e-cigs”); 5) concealability (i.e., “It is easy to hide from my parents”, “It is easy to hide from my teachers”); and 6) “other” (with the option to write in a response).

2.3.3. Reasons for disliking JUUL

Reasons for disliking JUUL were assessed with a question, “What do you dislike about using a JUUL? (Select all that apply)” Response options included items assessing 1) adverse pharmacological effects (i.e., “It gives me a headache”, “It makes me jittery or shaky”, “The headrush is too strong”); 2) negative product characteristics (i.e., “The pods are expensive”, “Nicotine is too high”, “I don’t like the flavors”, “There aren’t many flavor options”); 3) peer influence (i.e., “My friends don’t use it”); 4) “none of the above”; and 5) “other” (with the option to write in a response).

2.3.4. Covariates

Covariates included sex (female, male), age, race (White vs. non-White), current use of e-cigarette device(s) other than JUUL, and current use of non-e-cigarette tobacco product(s).

Current use of other e-cigarette device(s) other than JUUL was assessed with a question, “Approximately how many days out of the past 30 days did you use [an e-cigarette device]?” Separate questions were asked for cigalike/e-hookah, vape pen, pod system, mods/advanced personal vaporizers, and other pod devices. Students reporting any past month use of any of these devices were coded as currently using e-cigarette devices other than JUUL and students reporting “no” to all questions asking if they had used other e-cigarette devices other than JUUL were coded as not using other e-cigarette devices.

Current use of non-e-cigarette tobacco product was assessed with a question, “Approximately how many days out of the past 30 days did you use [a tobacco product]?” Separate questions assessed use of cigarettes, cigarillos, smokeless tobacco, hookah, and blunts, and questions included a picture and a brief description of each product. Students reporting past-month use of any tobacco product were coded as currently using other tobacco product(s), and students reporting no past-month use of all tobacco products or “no” to all questions asking if they had use each tobacco product in the past month were coded as not currently using other tobacco products.

2.4. Data analysis

We conducted two multivariable models separately analyzing reasons for liking and reasons for disliking as predictors of frequency of JUUL use in the past month. Each model adjusted for covariates including school, demographics (i.e., sex, race [White vs. non-White], age), current use of other e-cigarette devices (yes/no) and current use of non-e-cigarette tobacco products (yes/no). We checked for multicollinearity between independent variables using variance inflation factor (VIF). VIF between independent variables was low and ranged from 1.0 to 2.9, which does not indicate the presence of multicollinearity.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics and JUUL use

Of the total sample (N=3170), 30.2% (n=956) were current JUUL users. See Table 1 for demographic characteristics, current use of other e-cigarette devices, and current use of other tobacco products for the total sample and by JUUL use status. Relative to non-JUUL users, current JUUL users were more likely to be White (vs. non-white), older, use other e-cigarettes, and use other tobacco products (ps<0.0001). Current JUUL users reported using JUUL on an average of 13.6 days (SD=11.7) in the past month, with 25% reported daily use.

Table 1:

Demographic and JUUL use and other e-cigarette/tobacco use characteristics

| Total sample (N=3170) | Non-Users (69.8%, n=2213)a | Current JUUL Users (30.2%; n=956)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 52.3 | 52.0 | 53.0 |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 60.3 | 57.1 | 68.1 |

| Hispanic | 16.4 | 16.8 | 15.7 |

| Multi-race | 9.7 | 9.8 | 9.5 |

| Black | 7.6 | 9.3 | 3.7 |

| Other | 5.8 | 7.0 | 3.0 |

| Age (M, SD) | 15.9, 1.3 | 15.7, 1.3 | 16.2, 1.3 |

| Past-30-day JUUL use (M, SD) | -- | -- | 13.6, 11.7 |

| Past-30-day use of other e-cigarette devices (%) | 24.1 | 5.5 | 67.1 |

| Past-30-day use of other tobacco products (%) | 19.5 | 7.3 | 47.6 |

Note:Bold font indicates statistical difference (p < 0.05) between non-users and current users.

One participant was missing data on JUUL use status.

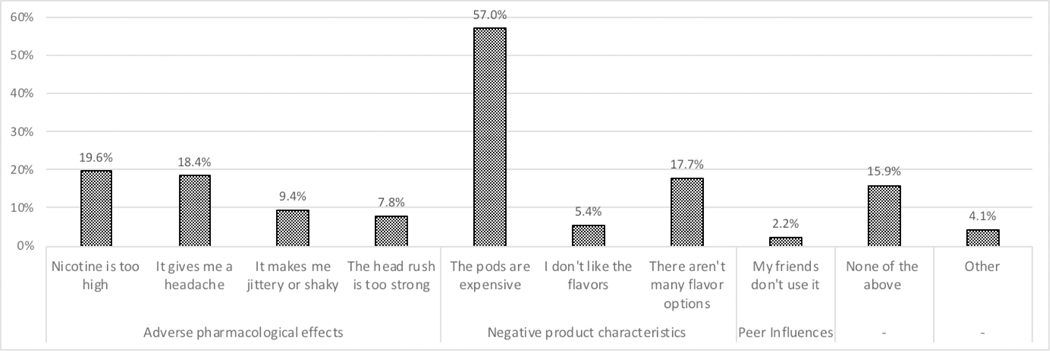

3.2. Reasons for liking JUUL

The top reasons for liking JUUL among current JUUL users were: “it gives me a buzz” (52.2%), “I like the flavors” (42.7%), and “my friends use it” (36.1%). The majority of written “other” responses were related to using JUUL to help manage anxiety and stress. Other responses for liking JUUL included the ability to do vape tricks, looking “cool,” to manage boredom (“it helps with boredom”), good smell, and being addicted to it.

In the adjusted regression model (Table 2), endorsement of liking JUUL because of getting a buzz (β=0.17, p< 0.001), the ability to concentrate (β=0.08, p= 0.007), the nicotine level (β=0.10, p= 0.003), ease of hiding it from teacher (β=0.09, p=0.028), and “other” (β=0.06, p=0.021) were associated with JUUL use frequency in the past month. Additionally, endorsement of liking JUUL because their friends use it was negatively associated with JUUL use frequency in the past month (β=−0.12, p<0.001). Other items were not significantly associated with JUUL use frequency.

Table 2.

Associations between reasons for liking JUUL and frequency of JUUL use in the past month.

| Reasons for liking | Adjusted Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | β | ||

| Pharmacological effects | It gives me a buzz. | 4.08 (4.46) | 0.17 |

| It helps me concentrate. | 2.44 (0.91) | 0.08 | |

| It gives me energy. | 1.23 (1.07) | 0.04 | |

| It helps me control my appetite. | 2.52 (1.40) | 0.06 | |

| It helps me lose weight. | 2.23 (1.83) | 0.04 | |

| Positive product characteristics | I like the flavors. | 0.62 (0.73) | 0.03 |

| I like the size of the JUUL. | 0.59 (1.17) | 0.02 | |

| I like the nicotine level. | 3.03 (1.03) | 0.10 | |

| It is easy to change pods. | 1.87 (1.04) | 0.07 | |

| I like the shape of the JUUL. | 0.14 (1.30) | 0.00 | |

| Peer influence | My friends use it. | −2.75 (0.69) | −0.12 |

| Comparison to other e-cigs | I believe that it’s less harmful than other e-cigarettes. | 0.28 (0.85) | 0.01 |

| I like that it produces less vapor than other e-cigarettes. | −0.56 (1.16) | −0.02 | |

| Concealability | It is easy to hide from my parents. | −0.31 (1.18) | −0.01 |

| It is easy to hide from my teachers. | 2.86 (1.30) | 0.09 | |

| “Other” | 4.11 (1.78) | 0.06 | |

Note:Bold font indicates statistically significant difference, p≤ 0.05. The model controlled for school, sex, age, race current use of other e-cigarette devices, and current other tobacco use other than e-cigarettes.

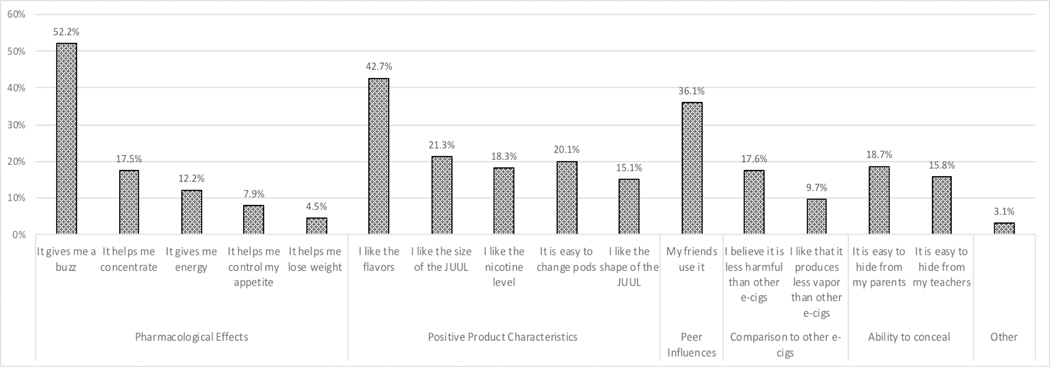

3.3. Reasons for disliking

The top reasons for disliking JUUL among current JUUL users were: “the pods are expensive” (57.0%) followed by “nicotine is too high” (19.6%) and “it gives me a headache” (18.4%). “Other” responses mostly included negative health effects (e.g., “it’s bad for you,” nausea), parental disapproval, and that it’s illegal. See Figure 2 for rates of endorsement of all reasons for disliking JUUL. In the adjusted regression model, endorsement of disliking JUUL because of the high cost of pods was associated with JUUL use frequency in the past month (β=0.17, p=0.003). No significant associations were observed between endorsement of other reasons for disliking JUUL and frequency of use in the past month.

Figure 2.

Reasons for disliking JUUL among current JUUL users Note: Participants were instructed to select all that apply so the sum of percentages may be greater than 100%. Current use is defined as using JUUL ≥ 1 days in the past 30 days.

4. DISCUSSION

This study is the first to examine specific reasons for liking and disliking JUUL and how endorsement of these reasons relates to JUUL use frequency among current JUUL users (i.e., past-month users) in a sample of high-school youth. Among current JUUL users, the most frequently endorsed reasons for liking JUUL were getting a “buzz,” appealing flavors, and use by friends. The most frequently endorsed reason for disliking JUUL was the perception that JUUL pods were expensive, followed by “nicotine is too high”, and “it gives me a headache.”

We observed that items related to liking JUUL because of nicotine level and nicotine effects (i.e., feeling buzzed, ability to concentrate) were associated with more frequent use over the past month. The finding that youth are reporting liking JUUL for the nicotine effects is concerning because nicotine is a known psychoactive stimulant with high addiction potential (De Biasi and Dani, 2011), and using JUUL has been shown to result in high levels of nicotine exposure among youth (Goniewicz et al., 2018). Furthermore, nicotine has neurotoxic effects in the adolescent brain and can lead to nicotine dependence (Yuan et al., 2015).

Our evidence suggests that reducing nicotine levels in JUUL may be an important step toward reducing youth appeal. However, it is also important to note that nicotine effects may also be a deterrent to use for some youth since a subsample endorsed disliking JUUL due to nicotine effects (e.g., headache, high nicotine levels). These findings raise other concerns about the recent availability of the 3% JUUL pods, as the lower nicotine concentration may attract adolescents who dislike effects associated with the stronger, 5% strength. Future studies should examine how different nicotine concentrations impact youth initiation and progression of JUUL use behaviors. Additionally, our previous studies indicate that youths’ knowledge of and their understanding of nicotine levels in e-cigarettes, including JUUL varies (Morean et al., 2019; Morean et al., 2016), so more effort is needed to educate youth about different levels of nicotine and their effects.

We also observed that the ability to hide the device from teachers was related to frequent JUUL use. This finding is consistent with the findings from college students who like the ability to vape indoors in colleges (Nardone et al., 2019) and the social media findings that showed that youth are Tweeting about using JUUL as a discreet way to vape in schools (Allem et al., 2018). Taken together, these findings suggest that school staff and teachers should be informed of JUUL to prevent youth from using it in schools.

Other highly endorsed reasons for liking JUUL included liking the flavors and friends’ use, consistent with prior youth e-cigarette and tobacco research. For instance, appealing e-cigarette flavors is the primary reason for youth e-cigarette initiation (Kong et al., 2015), and preferring sweet e-liquids and using more flavors is associated with more frequent use among adolescents (Morean et al., 2018a). Furthermore, our finding that peer JUUL use was a reason for liking JUUL is consistent with research demonstrating that peer use plays an important role in combustible tobacco use among youth (Simons-Morton and Farhat, 2010). Unexpectedly, we did not observe an association between liking JUUL because of the flavors and frequency of JUUL use, and furthermore, peer influence was inversely associated with the number of days of JUUL use. This leads us to speculate that perhaps use of flavors and use by friends lead to experimentation with JUUL and other product characteristics associated with nicotine effects sustain use. Future studies should examine how these reasons predict different stages of use from initiation to progression of regular use.

We observed that the top reason for disliking JUUL among current JUUL users was the perception that pods are expensive. However, endorsement of disliking this reason was associated with frequent use in the past month. Perhaps users who use JUUL frequently purchase and own their own device and pods, and therefore may be more likely to be dissatisfied with the cost. Given the strong literature showing that increasing cigarette prices through taxation is a particularly effective youth cigarette smoking prevention strategy (Carpenter and Cook, 2008; Lantz et al., 2000), future studies should also examine how increasing taxes on JUUL could influence youths’ continued use as well as preventing initiation.

Of note, we observed that current use of JUUL was high (30.2%) among adolescents in our sample. This high use rate may be due to asking specifically about JUUL use rather than about e-cigarette use more broadly (Morean et al., 2018b). Our prior work showed that many youth do not consider JUUL to be an e-cigarette (Morean et al., 2019) and often use the term like “juuling” to refer to JUUL use. Thus, asking about e-cigarette use without specifying brand used could result in lower estimate of prevalence rate (Morean et al., 2019; Morean et al., 2018b).

4.1. Limitations

Several study limitations should be considered. First, the study was conducted in high schools in southeastern Connecticut, which may limit generalizability. However, evidence from our regional studies has closely corresponded to national survey data over the years (Camenga et al., 2018; Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2015). Second, while we selected liking/disliking response options based on existing literature, we did not examine other potential reasons including whether youth were using a JUUL to quit smoking, to help them concentrate in class/improve school grades, or because of exposure to marketing influences targeting youth. Interestingly, youth who selected “other” as a reason for liking JUUL used more frequently in the past month than those who did not select this response option. The majority of the written responses to “other” response option included the ability to manage stress and anxiety, as well as responses related to conducting vape tricks, looking cool, smelling good, managing boredom, and being addicted to it. Future studies should assess these reasons as well as additional reasons for liking JUUL to further understand youth appeal. Third, we focused on JUUL given its popularity among youth (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2019). However, other pod-mod devices like Suorin and PHIX deserve future attention. Finally, we examined reasons for liking/disliking JUUL among current users who already used the product and are familiar with the product to better understand the factors that influence appeal; additional research is needed to understand how features of this device appeal to non-users who are susceptible to future use to inform prevention efforts.

4.2. Conclusions

Our study findings suggest that current youth JUUL users endorse the nicotine effects such as feeling “buzzed,” the flavors, and peer use as the primary reasons for liking JUUL. The most frequently endorsed reason for disliking JUUL was the high cost of the pods. Moreover, we observed that factors associated with nicotine effects and nicotine level and the ability to hide JUUL from teachers were associated with more frequent use in the past month. These findings should be taken into consideration in the development of regulatory policies and prevention efforts. Regulations should focus on lowering the level of nicotine below the addiction threshold, reducing appealing flavors, and increasing taxes on JUUL. National media campaigns should focus on educating youth and school personnel about the negative effects of nicotine on the developing brain and on other acute and long-term effects of nicotine exposure. Finally, treatment programs that focus on helping youth manage nicotine addiction and quit JUUL and other e-cigarette use are also needed.

Figure 1.

Reasons for liking JUUL among current JUUL users Note: Participants were instructed to select all that apply so the sum of percentages may be greater than 100%. Current use is defined as using JUUL ≥ 1 days in the past 30 days.

Table 3.

Associations between reasons for disliking JUUL and frequency of JUUL use in the past 30 days.

| Reasons for disliking | Adjusted Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | β | ||

| Adverse pharmacological effects | Nicotine is too high. | −2.58 (1.39) | −.09 |

| It gives me a headache. | −0.15 (1.55) | −0.01 | |

| It makes me jittery or shaky. | 0.05 (2.06) | 0.00 | |

| The head rush is too strong. | −2.10 (2.20) | −0.05 | |

| Negative product characteristics | The pods are expensive. | 4.09 (1.37) | 0.17 |

| I don’t like the flavors. | −1.01 (2.20) | −0.02 | |

| There aren’t many flavor options. | 0.35 (1.54) | 0.01 | |

| Peer influence | My friends don’t use it. | −1.07 (3.08) | −0.02 |

| None of the above | 2.08 (1.68) | 0.08 | |

| “Other” | 0.52 (2.24) | 0.01 | |

Note:Bold font indicates statistically significant difference, p≤ 0.05. The model controlled for school, sex, age, race, current use of other e-cigarette devices, and current other tobacco use other than e-cigarettes.

HIGHLIGHTS.

The top reason for liking JUUL among youth was feeling the “buzz.”

The top reason for disliking JUUL among youth was the high cost of the pods.

Liking nicotine effects and ability to hide from teachers predicted JUUL use.

Liking peer use of JUUL was negatively associated with JUUL use.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This study was funded by grants P50DA036151 and U54DA036151 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). The content is solely the responsible of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the FDA.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Morean consults for Gofire, Inc with a restricted stock agreement. All other co-authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allem J-P, Dharmapuri L, Unger JB, Cruz TB, 2018. Characterizing JUUL-related posts on Twitter. Drug Alcohol Depend 190, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Leventhal AM, 2018. Adolescents’ use of “pod mod” e-cigarettes — Urgent concerns. N Engl J Med 379, 1099–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camenga DR, Morean ME, Kong G, Krishnan-Sarin S, Simon P, Bold KW, 2018. Appeal and use of customizable e-cigarette product features in adolescents. Tob Regul Sci 4, 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C, Cook PJ, 2008. Cigarette taxes and youth smoking: New evidence from national, state, and local Youth Risk Behavior Surveys. J Health Econ 27, 287–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connecticut School Finance Project, 2016. http://ctschoolfinance.org/assets/uploads/files/DRGOne-Pager-FINAL.pdf.accessed on 5/15/19.

- De Biasi M, Dani JA, 2011. Reward, addiction, withdrawal to nicotine. Annu Rev Neurosci 34, 105–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England LJ, Bunnell RE, Pechacek TF, Tong VT, McAfee TA, 2015. Nicotine and the developing human: a neglected element in the electronic cigarette debate. Am J Prev Med 49, 286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erythropel HC, Davis LM, De Winter TM, Jordt SE, Anastas PT, O’Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, Zimmerman JB, 2019. Flavorant-solvent reaction products and menthol in JUUL e-cigarettes and aerosol. Am J Prev Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA, 2018. Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on new enforcement actions and a Youth Tobacco Prevention Plan to stop youth use of, and access to, JUUL and other e-cigarettes. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fdacommissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-new-enforcement-actions-and-youth-tobaccoprevention.accessed on 5/17/19.

- Gentzke AS, Creamer M, Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Willis G, Jamal A, King BA, 2019. Vital Signs: Tobacco product use among middle and high school students — United States, 2011–2018. MMWR 68, 157–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenson NI, Leventhal AM, Stone MD, McConnell RS, Barrington-Trimis JL, 2017. Associations of electronic cigarette nicotine concentration with subsequent cigarette smoking and vaping levels in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr 171, 1192–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goniewicz ML, Boykan R, Messina CR, Eliscu A, Tolentino J, 2018. High exposure to nicotine among adolescents who use Juul and other vape pod systems (‘pods’). Tob Control, tobaccocontrol-2018–054565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juul Labs, 2019. https://www.juul.com/.accessed on 04/11/2019.

- King BA, Gammon DG, Marynak KL, Rogers T, 2018. Electronic cigarette sales in the United States, 2013–2017. JAMA 320, 1379–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S, 2015. Reasons for electronic cigarette experimentation and discontinuation among adolescents and young adults. Nic Tob Res 17, 847–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Jackson A, Morean ME, Kong G, Bold KW, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Simon P, Wu R, 2019. E-cigarette devices used by high-school youth. Drug Alcohol Depend 194, 395–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean ME, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Kong G, 2015. E-cigarette use among high school and middle school students in Connecticut. Nic Tob Res 17, 810–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE, Wasserman J, Pollack HA, Berson J, Ahlstrom A, 2000. Investing in youth tobacco control: a review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tob Control 9, 47–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavens ELS, Stevens EM, Brett EI, Hébert ET, Villanti AC, Pearson JL, Wagener TL, 2019. JUUL electronic cigarette use patterns, other tobacco product use, and reasons for use among ever users: Results from a convenience sample. Addict Behav 95, 178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantey DS, Harrell MB, Case K, Crook B, Kelder SH, Perry CL, 2017. Subjective experiences at first use of cigarette, e-cigarettes, hookah, and cigar products among Texas adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend 173, 10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Bold KW, Kong G, Gueorguieva R, Camenga DR, Simon P, Jackson A, Cavallo DA, Krishnan-Sarin S, 2019. Adolescents’ awareness of the nicotine strength and e-cigarette status of JUUL e-cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend 204, 107512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Butler ER, Bold KW, Kong G, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Simon P, O’Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, 2018a. Preferring more e-cigarette flavors is associated with e-cigarette use frequency among adolescents but not adults. PLos ONE 13, e0189015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Jackson A, Cavallo DA, Kong G, Bold KW, Simon P, Krishnan-Sarin S, Camenga DR, 2018b. Querying about the use of specific e-cigarette devices may enhance accurate measurement of e-cigarette prevalence rates among high school students. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S, 2016. Nicotine concentration of e-cigarettes used by adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend 167, 224–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardone N, Helen GS, Addo N, Meighan S, Benowitz NL, 2019. JUUL electronic cigarettes: Nicotine exposure and the user experience. Drug Alcohol Depend 203, 83–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Farhat T, 2010. Recent findings on peer group influences on adolescent smoking. J Prim Prev 31, 191–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS, 2016. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults. A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Vallone DM, Bennett M, Xiao H, Pitzer L, Hair EC, 2018. Prevalence and correlates of JUUL use among a national sample of youth and young adults. Tob Control, tobaccocontrol-2018–054693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M, Cross SJ, Loughlin SE, Leslie FM, 2015. Nicotine and the adolescent brain. J Physiol 593, 3397–3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]