Abstract

Background:

Two million adolescents experience suicidal ideation (SI) or suicide attempt (SA) annually, and they frequently present to emergency departments. Delays in transfer to inpatient psychiatric units increasingly lead to “boarding” in ED and inpatient medical units. We sought to understand adolescents’ perspectives during boarding hospitalizations to gain insight into helpful practices and targets for improvement.

Methods:

Using convenience sampling, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 27 adolescents hospitalized for SI or SA, while they were awaiting transfer to an inpatient psychiatric facility. Interviews were recorded and transcribed, with thematic analysis organized using NVivo 11.

Results:

Eight themes emerged: (1) Supportive clinical interactions, (2) Information needs, (3) Repetitive inquiries (4) Safety, (5) Prior hospital experiences, (6) Activities and boredom, (7) Physical comfort, and (8) Emotions. Adolescents experienced the hospital as a safe environment, were relieved to be receiving help to reduce their suicidal thoughts or behaviors, and expressed appreciation for compassionate clinicians. They emphasized the value of physical comfort, staying occupied, and information about what to expect. Reports of embarrassment and discomfort about repeated inquiries from the clinical team, and unanswered questions about what would occur during the planned inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, were common.

Conclusions:

Perspectives of adolescents seeking care for SI or SA are an important source of information for healthcare systems seeking to improve hospital care. Clinicians can relieve distress of adolescents awaiting psychiatric hospitalization by focusing on compassionate connection, minimizing repeated inquiries, and providing complete and concrete information about treatment plans.

Introduction

Two million US adolescents experience suicidal ideation (SI) or a suicide attempt (SA) each year, and suicide is the second leading cause of death among 10- to 24-year-olds.1 Adolescents are increasingly visiting medical emergency departments (EDs) with SI and/or SA, where they typically receive an initial medical evaluation.2 Those who require further psychiatric evaluation and treatment are often transferred to inpatient psychiatric units, but limited bed availability can lead to transfer delays even after medical needs have been met.3 In order to ensure the safety of young people at risk of suicide, many institutions house them in EDs or inpatient medical units for observation while awaiting transfer to an inpatient psychiatric unit, a practice commonly referred to as “boarding4.”

Observation in medical EDs and inpatient units helps to ensure physical safety, but medical units are not equipped to provide definitive psychiatric care, and staff may not be well-trained in the care of patients with SI or SA.4,5 Further, whereas there are resources available to guide acute management of suicidal patients in EDs,6,7 there is no current consensus on best practices for the care of patients who are boarding. In particular, little is known about how children and adolescents experience their time in the hospital while boarding, despite the fact that this healthcare encounter represents a chance to engage young people in care. Experiences with boarding have the potential to influence future treatment, as prior research has established that both positive and negative experiences with mental health care affect willingness to seek future care.8–10 In light of the fact that some young people experience recurrent SI or SA,11 understanding factors that promote or discourage positive engagement with the health care system surrounding SI or SA is an important goal.

In keeping with prior efforts to incorporate adolescent perspectives into care models,12,13 we sought to gather information about the perspectives and experiences of young people with SI or SA who were boarding in an ED or medical unit while awaiting inpatient psychiatric treatment. The study’s primary objectives were to understand: (1) how adolescents perceived interactions with the clinical team, (2) which clinical practices felt beneficial, and (3) what adolescents thought should be changed about the hospital stay.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted at a 535-bed freestanding children’s hospital in the mid-Atlantic US, which serves as an urban community hospital and a national referral center. There is no inpatient psychiatric unit. For patients presenting to the ED with SI and/or SA, the usual care process begins with evaluation by an ED physician, social worker, and psychiatrist to determine the severity of physical and mental health concerns. Patients requiring medical treatment are admitted to a medical floor. Patients requiring inpatient psychiatric treatment are typically transferred to one of five psychiatric hospitals in the region. When no inpatient psychiatric unit bed is available within several hours, the patient is admitted to a medical inpatient or observation unit. The patient is then cared for by a general medical team, mental health consultation service, pediatric nursing staff, and continuous 1:1 safety observer. Rounds are most often conducted without the patient or family present, and individual clinicians inform patients and families of updates after rounds. Most safety observers are psychiatric technicians (i.e., bachelor’s-prepared hospital employees with training in mental health or child development).

Participants and Procedures

Study procedures were approved by the hospital’s institutional review board. Patients were eligible for study participation if they were: 1) aged 9 to 21 years, 2) hospitalized for SI and/or SA, medically cleared, and awaiting transfer to an inpatient psychiatric unit, and 3) able to complete an interview in English. Patients were ineligible to participate if they had significant cognitive impairment, aggression, or self-injury during the hospitalization, were in the custody of juvenile justice or social services, or if the medical team considered the patient inappropriate to approach for research.

During the rolling recruitment period from September 2017 to May 2018, we enrolled 27 adolescents in the study. Research staff explained the study verbally and obtained written assent from participants and written consent from guardians, including permission from both to audio-record interviews. In accordance with state law, participants 14 years and older also provided written consent to allow mental health information obtained from the electronic health record and disclosed in interviews to be used in the research. Youth received a $20 gift card for participating in the study.

Data Collection

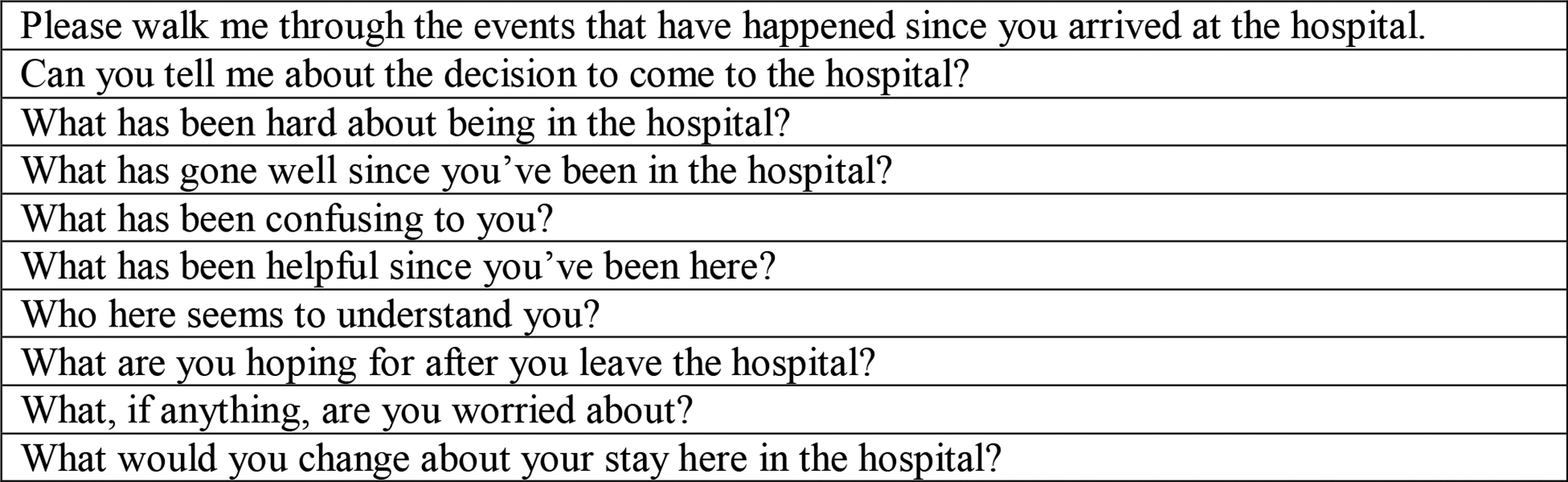

Four graduate-student or master’s-prepared trained interviewers conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews (see Figure 1). Interviews lasted approximately one hour and asked the adolescents to describe: (1) events leading up to the hospitalization, (2) how adolescents perceived interactions with the clinical team, (3) which clinical practices felt beneficial, (4) positive or negative feelings about their care and hospital stay, and (5) what they would change about their hospital stay. In addition, adolescents self-reported sociodemographic information using an electronic tablet. Research staff obtained indication for hospitalization (SI or SA), psychiatric diagnoses,14 physical chronic conditions,15 and physical complex chronic conditions,16 payer information, and length of stay (i.e., time from ED arrival to hospital discharge) from the electronic health record.

Figure 1.

Sample Interview Questions

Data Analysis

Following transcription, two trained coders independently reviewed and coded each interview transcript to identify themes, using the principles of directed content analysis.17 All members of the study team reviewed all transcripts and codes and met at regular intervals to discuss emerging themes. Coding discrepancies were resolved through discussion to reach consensus. One-fifth of interview transcripts were independently coded by 2 coders to establish inter-rater reliability, resulting in Cohen’s kappa of 0.98. In keeping with principles of thematic saturation,18 the study team achieved consensus that thematic saturation was reached after 6 successive additional interviews had not added new themes. NVivo 11 (QSR International; Melbourne, Australia) was used in organizing the thematic analysis.19

Results

Patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are displayed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. SI (n=22) was more common than SA (n=5) in this relatively diverse group of young people. The most common clinical diagnosis was a depressive disorder, and although none carried a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder, more than half of participants had a documented traumatic experience, such as a sexual assault or death of a close family member. Median length of stay was 2 days [IQR: 2–3].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Adolescents “Boarding” While Awaiting Inpatient Psychiatric Treatment for Suicidal Ideation or Suicide Attempt (N=27)

| Characteristica | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| 9–14 years | 18 (67) |

| 15–18 years | 9 (33) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 12 (44) |

| Female | 11 (41) |

| Transgender or gender non-conforming | 4 (15) |

| Race | |

| White | 12 (44) |

| African American | 10 (37) |

| Other | 2 (8) |

| More than one race | 3 (11) |

| Hispanic/Latino Ethnicity | 1 (4) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 21 (77) |

| Bisexual | 1 (4) |

| Lesbian | 1 (4) |

| Queer | 1 (4) |

| Other | 3 (11) |

| School type | |

| Public | 21 (78) |

| Private | 2 (7) |

| Technical | 1 (4) |

| Not reported | 3 (11) |

| Family owns a car | 21 (78) |

| Family owns a home | 16 (59) |

| Payer | |

| Medicaid | 16 (59) |

| Private insurance | 11 (41) |

Information was self-reported by adolescents, except payer (obtained from electronic health record).

Table 2.

Treatment and Clinical Characteristics of Adolescents Awaiting Inpatient Psychiatric Treatment (N=27)

| Characteristica | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Reason for admission | |

| Suicidal ideation | 22 (81) |

| Suicide attempt | 5 (19) |

| Length of stay in daysb, median (IQR) | 2 (2–3) |

| Required acute medical treatment | 5 (19) |

| Previous inpatient psychiatric hospitalization | 10 (37) |

| Psychiatric diagnosesc | |

| Depressive disorder | 20 (74) |

| Anxiety disorder | 8 (30) |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 5 (19) |

| Bipolar disorder or schizophrenia | 3 (11) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 4 (15) |

| History of trauma | 15 (55) |

| Physical health conditions | |

| Chronic, non-complexd | 7 (26) |

| Complex chronice | 3 (11) |

Data were obtained from the electronic health record.

Represents time from admission to discharge date, regardless of whether participants required initial medical care.

Identified using a previously-published classification system. Categories are not mutually exclusive, so percentages do not sum to 100.

Identified using the Chronic Condition Indicator system,15 excluding Complex Chronic Conditions.

Identified using the Complex Chronic Condition classification system.16

Eight themes emerged: (1) Supportive clinical interactions, (2) Information needs, (3) Repetitive inquiries (4) Safety, (5) Prior hospital experiences, (6) Activities and boredom, (7) Physical comfort, and (8) Emotions. Additional quotes illustrating these themes can be found in Table 3.

Table 3:

Key Thematic Areas and Sample Statements from Adolescents’ Descriptions of their Hospital Experiences while Awaiting Inpatient Psychiatric Treatment

| Supportive Clinical Interactions | “I feel like the people who are here with me for hours on end, because they understand. Even witnessing the way I interact with my parents and just listening, they understand my frustrations and everything because I am talking to them the entire day.” |

| Information Needs | |

| “Well, at my [previous hospitalization], they really sugar coated it. I really wish that they would have told me what other types of kids were going to be there. I really wish they would have told me what the place was like, because when I got there it was definitely much, much worse than they made it out to be.” | |

| Repetitive Inquiries | |

| “Everybody was asking me questions about… how I got here and stuff like that. It made me feel overwhelmed and bad about myself.” | |

| Safety | “I feel better. Because at first, I was scared, but now, I’m not scared.” |

| Prior Hospital Experiences | “I don’t know if I’m gonna get needles or not. I am very scared of needles.” |

| Activities and Boredom | “I am kind of bored and just like a lot of sitting and just like I know I can’t really get up and then just walk around. And I started thinking that I don’t want to be here then I just get upset and stuff.” |

| Physical Comfort | “The blankets are like the thinnest. And I’ve gotten used to the temperature, but it’s really cold in here.” |

| Emotions | “I’ve been less stressed, which means no suicidal thoughts.” |

Supportive Clinical Interactions

When asked what was going well during their hospitalization, about half of adolescents mentioned communication with clinicians. Several practices contributed to adolescents expressing feelings of trust and safety. Specifically, adolescents felt more secure when clinicians described the processes of the ED visit, pediatric hospitalization, and inpatient psychiatric hospitalization to them; this helped them feel less stressed about the current hospitalization and plan for an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. For example, one young man explained: “[the psychiatrist] really knows more about what’s going to go on at the other hospital…So, me listening to him helped.”

Participants felt grateful towards clinicians who showed compassion and interest in their well-being. Adolescents who felt reassured by the clinicians that they would receive help reported a higher degree of comfort with their provider than those who did not perceive their provider as reassuring. In particular, participants reported feeling comfortable with clinicians who communicated transparently and described both medical and mental health clinicians as approachable, nice, and easy to talk to.

Adolescents also experienced high comfort with 1:1 staff observers. Many patients described that the 1:1 observer helped them understand the reason for their hospitalization and process emotions. One participant said, “The second the [1:1 psych tech] walked in, they cracked me up. They made me – they really honestly made my day so much better.”

Information Needs

Most adolescents had unanswered questions, and some noted that lack of information caused them anxiety. For example, one adolescent stated: “I just want to know what’s happening. That would put my mind at ease, but I am not really getting anything. So that’s freaking me out.” Adolescents expressed interest in receiving information about psychiatric hospitalization in several content areas: food, visitation, length of stay, entertainment, daily activities and schedules, location, clinicians providing treatment, types of therapy provided, and the physical structure and layout of inpatient psychiatric units.

Some adolescents felt uncertain whether they had received all pertinent information, including one who remarked: “I feel like there’s some nurses and doctors who understand that I’m not a little kid and I can handle information. Then there’s others – I guess it’s a children’s hospital, so I guess they’re just used to having – talking to younger kids and just like not giving me all the information.”

On the other hand, adolescents who did feel well-informed reported that this contributed positively to their experience. When asked what was helpful during the hospitalization, one participant noted, “the nurses telling me what’s going on” and “the psychiatrist who told me I’m going to another hospital to get help.”

Repetitive Inquiries

Many participants described feelings of stress, anxiety, and embarrassment when they were asked repeatedly by different clinicians to explain their health history and reason for hospitalization. Adolescents who felt remorse over their suicidal crisis cited heightened anxiety when having to repeat the story of why they presented to the ED. As one patient reported, “The first time it felt nice to be able to get everything out. But then after the second time of having to say everything, it was just like I didn’t want to talk. I was starting to feel like I had just explained this and I didn’t want to keep having to explain it.” In addition to the repetitive inquiries, patients described feeling intimidated by having to interact with a large number of staff and confused about the roles of different team members.

Safety

Most participants described feeling relieved, or in one adolescent’s words, “safe and secure,” while they were in the medical hospital. One participant reported feeling glad about being in the hospital, because she “didn’t want to just go home and be yelled at.” Another recounted feeling relieved that she had “no suicidal thoughts” since coming to the hospital.

Several participants raised concerns about physical safety in the psychiatric unit. One adolescent shared, “I’m just scared of the other kids because I know there’s kids that’s worse than me. I don’t want them to hurt me or anything.” Another participant described that she had “seen videos of abandoned hospitals and stuff, and it was creepy.”

Some expressed concerns about how they would stay safe once leaving a hospital environment. As one adolescent stated, “In the hospital… I’m not gonna really have to deal with any of the problems on a regular basis that I did at the house or at school. So it’s gonna be like all fine and dandy and I’m gonna have a plan. And then once I step out it’s gonna be like welcome to real life.”

Prior Hospital Experiences

Many adolescents compared their current hospitalization with prior medical hospital experiences. For some patients, being in a medical hospital felt familiar and comfortable: “I was actually here in the summer because I had [surgery] and I got it done here. I always loved [this hospital].” For other patients, fears related to prior medical experiences emerged; several patients worried about the possibility of painful treatment.

Others recounted worries related to negative experiences during prior inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, such as witnessing children become violent, receive injectable medications, or be placed in physical restraints. Finally, some patients expressed concerns about whether they would be able to maintain their privacy and dignity, recounting previous experiences where they felt they had not been treated fairly or respectfully.

Activities and Boredom

Participants appreciated opportunities to engage in activities alone or with other adolescents. Most participants reported enjoying individual activities, such as making crafts, playing video games, and watching TV. Several reported that interacting with child life specialists or creative arts therapists felt beneficial to them. Many used their or a family member’s smartphone to access social media or send text messages to friends. Adolescents reported feeling bored and distressed when they were not engaged in activities or conversation.

Physical Comfort

Participants commented on privacy, hospital amenities, and personal hygiene. Bedding and temperature were common concerns. One participant shared a positive experience: “My sister was able to visit to give me pants, so that’s nice. It’s also good that I’m allowed to shower even if I can’t be by myself in the room.” Many compared the physical environment in their current hospital room with the environment in other healthcare facilities, both favorably and unfavorably.

Emotions

Most participants reported that their emotions had become more positive since arriving in the hospital. One adolescent said: “When I first came in, I realized that I was kinda a little bit more scared and tensed up and not really wanting to do anything. But now, I’m kinda calm and feel comfortable.” Another reported that being in the hospital had given her a break from daily life stressors. Some adolescents acknowledged difficulty expressing emotions. In one participant’s words, “you put on a facade or a mask or a character while you’re in the hospital.”

Some patients shared negative or difficult emotions. They acknowledged stressors at home, and some expressed feelings of guilt or remorse about their mental health crisis. One patient who had made a suicide attempt shared, “I regret the decision I made.” Other adolescents acknowledged it felt difficult to know that their loved ones were worried about them.

Many participants expressed hopes for the future. Common themes included adolescents looking forward to returning to school and seeing their friends and family. One adolescent shared: “I just want this all to be over and just go home.”

Discussion

In this investigation of young people’s experiences with “boarding” in a medical hospital following ED presentation for SI or SA, we found that adolescents experienced several aspects of clinical care as supportive. Many felt safe in the hospital and had positive emotions associated with being hospitalized. Patients felt most comfortable when clinicians conveyed understanding of the patient’s concerns and provided specific information about the treatment plan, and they reported that engaging in leisure activities helped relieve distress. In addition, many patients believed that interacting with a 1:1 staff observer helped them process emotions and understand the hospital experience. At the same time, adolescents pointed out opportunities for improving clinical care: they felt overwhelmed by repetitive inquiries from the clinical team; they had unanswered questions about the medical hospital’s care processes; and they had questions about what to expect after their planned transfer to an inpatient psychiatric unit. These novel insights into suicidal adolescents’ healthcare experiences can help clinical teams design patient-centered care for adolescents hospitalized in medical units during mental health crises.

It is notable that many of the aspects of care that felt especially supportive to adolescents, including compassionate staff, opportunities to stay occupied with activities, and efforts to ensure physical comfort, are consistent with patient-centered hospital care in general. Our findings underscore that even in hospitals where mental health specialists are not readily available, general medical clinicians can provide young people with substantial benefit if they ensure high-quality routine hospital care. Clinicians may feel reassured and empowered knowing that young people with SI or SA have many of the same basic needs as those experiencing a general medical illness or emergency, and thus it is possible to provide valuable services to patients even without specialty mental health training.

At the same time, our findings highlight that patients with SI or SA have unique needs. Particularly in cases where SI or SA are related to a recent traumatic stressor, strategies to reduce the number of times an adolescent is asked to discuss upsetting events is likely to minimize patient distress. This is in keeping with current “mental health first aid” best practices, which acknowledge the importance of allowing individuals to open up at their own pace.20

Given that patients who are boarding are awaiting transfer to inpatient psychiatric care, it is understandable that they have additional information needs. Educational materials or directed conversations could help adolescents better understand the processes of clinical care.21–24 Clinicians can elicit questions or practice a teach-back method to determine whether young people have unanswered questions or concerns. A visual educational resource, such as a video or slideshow, could improve adolescents’ knowledge of what to expect in local psychiatric hospitals. For example, such a resource could include photographs of psychiatric unit physical spaces, examples of schedules and activities, and information about specific expectations. If such a resource is created in partnership with local psychiatric units, this could help clinical teams initiate some of the expectations that will be enforced in psychiatric units (e.g., daily schedules, limiting social media access) while the adolescent is boarding in a medical hospital. Opportunities to visit psychiatric hospital units and interact with their staff can help medical clincians feel equipped to explain the psychiatric hospitalization.

Ensuring commitment to patient-centered care for patients who are boarding requires an organizational commitment to SI/SA patients in the vulnerable waiting period between a suicidal crisis and the next phase of care, even in units not designed for psychiatric specialty care. A new policy statement from The American College of Emergency Physicians calls for all ED staff to be trained in child mental health issues including SA,25 and our findings suggest that mental health skills training for the staff who complete 1:1 safety observation and other staff caring for SI/SA patients may be especially high-yield. In the hospital where this study was conducted, teams caring for a high proportion of adolescents with psychiatric illness have invested in professional development opportunities to learn advanced mental health skills for nursing and pediatric staff, including Crisis Prevention Institute training26 and Trauma Informed Care training.27 All psychiatric technicians and some nurses receive introductory training in applied behavior analysis. Numerous other training opportunities exist for general clinicians, including those offered through the Resource for Advancing Children’s Health (REACH) Institute.28

Several study limitations warrant consideration. We did not capture the perspectives of several categories of vulnerable adolescents: those from limited English proficiency families, in the juvenile justice system or in the custody of social services, or with aggression. In addition, we conducted the study at a nationally-known children’s hospital, where the care is tailored towards children and adolescents. Young people presenting to general EDs and hospitals without a pediatric focus may have different experiences, and our findings on the value of provider kindness, efforts to create a sense of safety, and sensitivity to information needs are likely to be particularly important to consider when caring for young people in other settings.

Future research to understand the perspectives of patient family members will also be important, particularly given that parent perspectives have been shown to influence willingness to engage in future mental health care for children.8–10 Understanding the perspectives of clinicians caring for safety observation patients is a critical step toward identifying barriers to and facilitators of effective care.

Conclusion

Children and adolescents with SI or SA who are awaiting psychiatric treatment have unique needs, and understanding their perspectives and experiences can help medical hospital leaders develop safe, effective, and patient-centered safety protocols and staff training.

Acknowledgments:

We acknowledge Jennifer Whittaker for her assistance with her assistance in conducting study interviews.

Funding Source: This study was funded by Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Division of General Pediatrics. Dr. Doupnik was supported by K23MH115162 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Statement: There are no disclosures to report.

Conflict of Interest Statement: There are no conflicts to report.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National suicide statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/statistics/index.html. 2016. Accessed February 20, 2019.

- 2.Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008–2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20172426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blader JC Acute inpatient care for psychiatric disorders in the United States, 1996 through 2007. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(12):1276–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fieldston E, Jonas J, Scharko AM. Boarding of pediatric psychiatric patients is a no-fly zone for value. Hospital Pediatrics. 2014;4(3):133–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claudius I, Donofrio JJ, Lam CN, Santillanes G. Impact of boarding pediatric psychiatric patients on a medical ward. Hospital Pediatrics. 2014;4(3):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun TH, Mace SE, & Katz ER Executive Summary: Evaluation and Management of Children and Adolescents With Acute Mental Health or Behavioral Problems. Part I: Common Clinical Challenges of Patients With Mental Health and/or Behavioral Emergencies. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161571–e20161571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betz ME, & Boudreaux ED Managing Suicidal Patients in the Emergency Department. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2016;67(2):276–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerkorian D, McKay M, Bannon WM. Seeking help a second time: parents’/caregivers’ characterizations of previous experiences with mental health services for their children and perception of barriers to future use. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006; 76(2):161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becker KD, Boustani M, Gellatly R, Chorpita BF. Forty Years of Engagement Research in Children’s Mental Health Services: Multidimensional Measurement and Practice Elements. Journal of Clincial Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2018;47(1):1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gopalan G, Goldstein L, Klingenstein K, Sicher C, Blake C, McKay MM. Engaging families into child mental health treatment: updates and special considerations. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;19(3):182–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S, et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mollen CJ, Barg FK, Hayes KL, Gotcsik M, Blades NM, Schwarz DF. Adolescent input for designing an emergency department-based intervention about emergency contraception: results from an in-depth interview study. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2009;25(10):625–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mollen CJ, Fernando M, Hayes KL, Barg FK. Pregnancy, contraception and emergency contraception: the language of urban adolescent young women. Journal of Pediatric Adolescent Gynecology. 2012;25(4):238–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zima BT, Rodean J, Hall M, Bardach NS, Coker TR, & Berry JG (2016). Psychiatric Disorders and Trends in Resource Use in Pediatric Hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20160909–e20160909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) for ICD-10-CM. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic_icd10/chronic_icd10.jsp. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- 16.Feinstein JA, Russell S, DeWitt PE, Feudtner C, Dai D, Bennett TD. R Package for Pediatric Complex Chronic Condition Classification. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(6):596–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1990. Print. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mason M Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2010;11(3). Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1428/3028. Accessed May 21, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11, 2015.

- 20.Kelly CM, Jorm AF, Kitchener BA. Development of mental health first aid guidelines on how a member of the public can support a person affected by a traumatic event: a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(49). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ambresin A, Bennett KB, Patton GC, Sanci LA, Sawyer SM. Assessment of youth-friendly health care: a systematic review of indicators drawn from young people’s perspectives. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013; 52(6):670–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britto MT, Gail BS, Robert FD, et al. Specialists understanding of the health care preferences of chronically ill adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;40(4):334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byczkowski T, Linda MK, Maria TB. Family experiences with outpatient care: do adolescents and parents have the same perceptions? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47(1):92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viner RM. Do adolescent inpatient wards make a difference? Findings from a national young patient survey. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):749–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pediatric Mental Health Emergencies in the Emergency Department. Policy Statement. American College of Emergency Physicians. September 2018. Available at: https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/pediatric-mental-health-emergencies-in-the-emergency-medical-services-system/. Accessed May 21, 2019: [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crisis Prevention Institute. CPI Resources. Available at: https://www.crisisprevention.com/Resources. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- 27.The Trauma Informed Care Project. TIC Resources: Trauma Informed Care. Available at: http://www.traumainformedcareproject.org/resources.php. Accessed May 21, 2019

- 28.The REACH Institute. Available at: http://www.thereachinstitute.org/. Accessed May 21, 2019.