Abstract

Aims

The UK government aims to develop alcohol care teams (ACTs) that provide care for alcohol dependence in general hospital settings. Service descriptors have been identified to support the development of ACTs. The aim of this study was to use Delphi panel principles to identify the clinical competencies required to provide these elements of service.

Methods

We formed an expert consensus panel of 24 senior clinical alcohol practitioners, leaders and experts by experience drawn from all regions of England. The study was divided into three distinct phases: (a) a review and synthesis of current literature in this area, (b) a face-to-face meeting of the expert panel and (c) subsequent iterations to refine the competencies until consensus was reached.

Results

Our initial search strategy resulted in 555 competency statements being extracted from a range of national clinical professional and occupational standards and other sources. The research team refined these statements to 98 competencies in advance of the expert meeting. The panel identified 14 additional statements and reduced the number of competencies to 78. Subsequent iterations finalized 72 competencies across the 8 service descriptors.

Conclusions

Drawing on the existing published resources and clinical experience, the expert panel has provided consensus on the core clinical competencies required for alcohol care teams in caring for hospitalized patients with alcohol use disorders. Whilst it is acknowledged that the range of current provision is variable, these competencies provide a template for clinical practice and the development of multidisciplinary ACTs.

BACKGROUND

Alcohol use is a leading risk factor of all-cause mortality and morbidity exerting a significant impact on the economic and health service burden throughout the world (Williams et al., 2018). Globally it is estimated that excessive alcohol use accounts for 5.3% of deaths and 5.1% of the burden of disease (World Health Organization, 2019).

Effective clinical responses need to be implemented for the range of alcohol-related clinical conditions, accidents, violence and self-harm within acute inpatient care settings and emergency departments (ED) (Jones and Bellis, 2013). The prevalence of alcohol use disorders (AUD) found within hospitals will be determined by community prevalence and the local health service configuration (Busby et al., 2017; Brennan et al., 2019). A systematic review of 65 studies involving 100,980 individuals, drawn from 17 countries, identified a prevalence of self-reported AUD of 15.6% amongst emergency department attenders and 16.5% within hospital ward admissions (Roche et al., 2006), whereas a multistate study of 459,599 patients in medical care settings in the USA found a 22.7% prevalence of AUD (Madras et al., 2009). A more recent systematic review within the UK hospital system taken from 124 studies, reporting on 1,657,614 patients, identified a prevalence for ‘harmful drinking’ of 19.8% and 10.3% for alcohol dependence (Roberts et al., 2019).

Patients with AUD place a disproportionate impact and cost on healthcare systems due to the need for ED and inpatient management of alcohol-related harms including chronic medical conditions, mental health disorders, injuries and social problems (Phillips et al., 2019). Meeting the care needs of these diverse patient groups is challenging amongst a non-specialist workforce often ill-equipped to address the complex and coexisting presentations (Roberts and Drummond, 2019). Internationally there has been a drive to enhance the quality of care for those with AUD admitted to general (acute) hospital care. The accrediting body for hospitals in the USA has adopted the screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) procedures into their most recent quality outcome measures (Joint Commission, 2019). Similarly, as part of the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England, 2019), the UK government has prioritized the development of alcohol care teams (ACTs) within general hospitals in England with the aim of improving care and reducing alcohol-related harms.

ACTs have been developed in the acute UK hospitals largely in response to the escalation in wholly attributable alcohol-related hospital admissions characterized by mental and behavioural disorders due to alcohol (ICD-10 F10 diagnostic codes; World Health Organization, 1992) and alcohol liver disease (ICD-10 K70 diagnostic codes) (NICE, 2016). Models, and impact, of multidisciplinary ACTs in delivering integrated alcohol treatment pathways in collaboration with community services have previously been described (Moriarty, 2011; 2019). However, to date, the implementation of ACTs within the UK NHS has been variable with models of services differing significantly (Public Health England, 2014). The aim is to develop ACTs that provide specialist care for patients with alcohol dependence and alcohol-related complications in general hospital settings. ACTs will be multidisciplinary teams, with strategic medical leadership. Eight core clinical components have been identified as essential roles of the ACT (NHS England and Improvement, 2019). The aim of this study was to use Delphi panel principles to develop consensus on the clinical competencies and skills required by the team aligned to the eight components required to deliver an effective, evidence-based service.

METHODS

A multidisciplinary expert panel of 24 senior clinical alcohol practitioners, leaders and experts by experience drawn from all regions of England was convened to inform the development of clinical competencies for the expansion of new alcohol care teams within the NHS in England. Panel members were co-opted from hospital-based alcohol services and related organizations and included nine clinical nurse specialists currently practicing in hospital-based alcohol teams, eight nurse leaders with experience in workforce development in alcohol services, three consultant psychiatrists, two experts by experience, one professor of nursing and a consultant physician.

The study was divided into three distinct phases: a review and synthesis of current literature in this area, a face-to-face meeting of the expert panel and subsequent iterations to refine the competencies until consensus was reached.

Literature review and synthesis

A structured search of existing published journal articles, policy documents and professional standard documents relating to practice skills, knowledge and competencies for the assessment and management of AUDs in general hospital settings was conducted.

The aim was to extract existing practice statements and standards to inform the initial expert panel meeting. Statements meeting the inclusion criteria related to specialist clinical practice in the assessment and care of adults that might be delivered within an acute hospital were included. Excluded were statements and standards relating to specialist clinical practice not usually delivered in ACTs (i.e. group therapy), statements related to sub-specialisms (i.e. maternal health, children and young people) and generic statements related to professional practice (i.e. communication, record-keeping).

Two members of the research team independently rated a random selection of 30% of extracted practice statements against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The inter-rater correlation was assessed using the kap command in STATA 15, and the level of agreement was 0.71. Using the ranges suggested by Landis and Koch (1977), it was identified that substantial agreement between raters (0.61–0.80) had been achieved, which would allow for the remaining practice statements to be reviewed by one rater. Duplicate statements were removed. The remaining practice statements were adapted and rephrased to form clinical competence statements.

Expert panel meeting

The practice statements extracted from the literature review were circulated in advance of the meeting to all panel members together with a reference list. Panel members were asked to review competency statements, which supported clinical practice aligned to the eight core clinical components (NHS England and Improvement, 2019).

At the meeting, the first task for the panel was to identify any omissions for inclusion in the list of practice statements. Members then divided into small groups to refine statements for the proposed clinical setting and consider the removal of any practice statements that were irrelevant or over specialized. Finally, using web-based technology (Vevox.app), panel members gave anonymous ratings on all remaining practice statements using a scale of agreement: strongly disagree = 1, disagree = 2, neither agree or disagree = 3, agree = 4 and strongly agree = 5.

Observers from NHS England and Improvement and Public Health England attended the panel meeting to support members in understanding the aims of ACTs as set out in the NHS Long Term Plan but did not form part of the consensus group.

Subsequent iterations for refinement and consensus development

Following the meeting, the competence document was updated based on feedback and voting at the meeting, and further refinement of competency statements through email communication continued with the panel until consensus was agreed. The documents were sent to panel members, with updated summary scores and comments, and using the same rating scale, members were asked to choose the relevant rating and provide further comments as necessary. A unanimous score of 4 or more endorsed the practice statement for inclusion in the final list of clinical competencies.

RESULTS

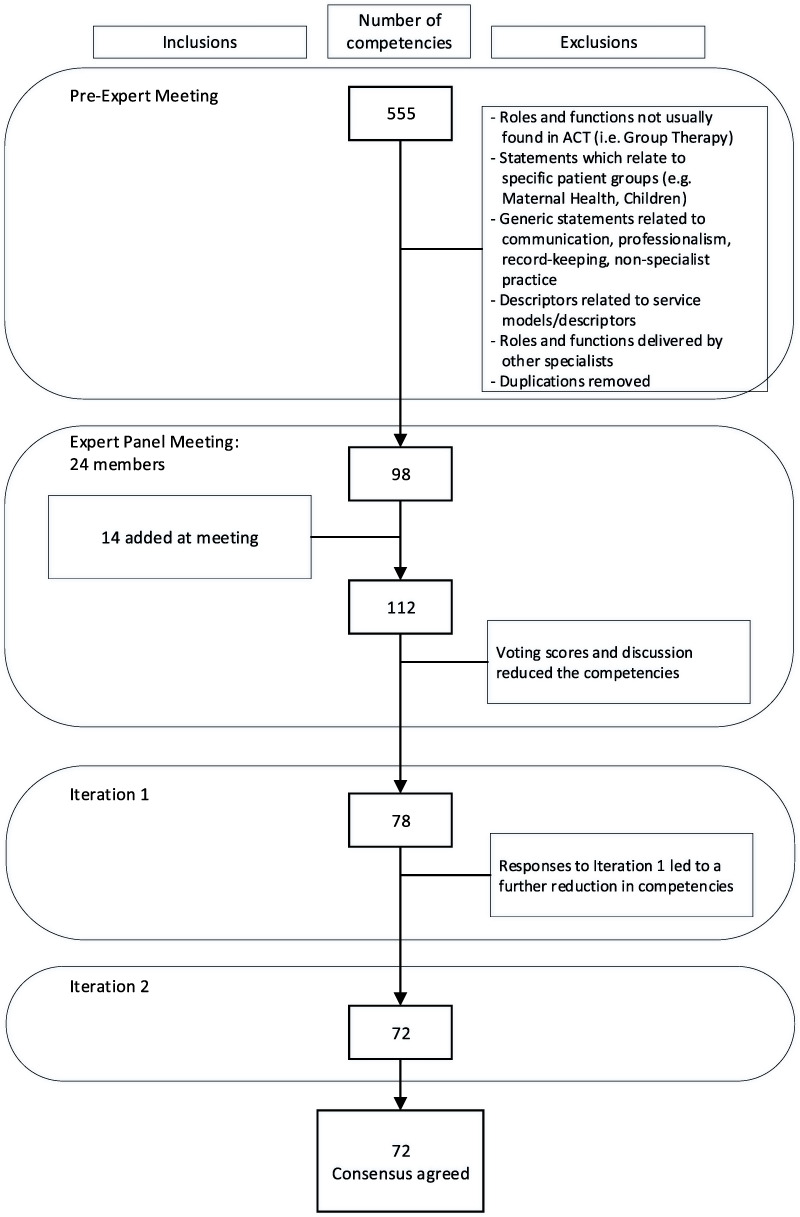

Our initial search strategy resulted in 555 practice statements being extracted from a range of national and international clinical professional and occupational standards and other sources (a full list of source materials can be found in Supplementary Table 1). From this, following good inter-rater reliability (Kapp = 0.71) of 166 (30%) practice statements, a total of 98 competency statements for submission to the expert panel were identified (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Process of endorsement and exclusions of clinical competency statements.

The expert panel members identified 14 additional competency statements for inclusion in the review relating to themes including assessing mental capacity, working with vulnerable groups and end of life care; advanced skills in assessing cognitive impairment; enhanced knowledge of medication interactions; and additional leadership skills to support the development of ACTs. Panel ratings and discussion identified further refinements to competencies. The research team reviewed all suggestions and comments and submitted 78 clinical competencies for review by the expert panel. Feedback was received from 14 (58.3%) of panel members. The final iteration of 72 clinical competencies was endorsed by 20 (83.3%) panel members with scores of 4 or more. An overview of the agreed clinical competencies aligned to the eight core components for multidisciplinary alcohol care teams is described in Table 1. The full statement list of clinical competencies is available in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 1.

Overview of clinical competencies for the care of hospitalized patients with alcohol use disorders aligned to the core service components for multidisciplinary alcohol care teams in England

| No. | Core service components for multidisciplinary alcohol care teams (ACT) in England (NHS England & Improvement, 2019) | No of competence statements (N = 72) | Overview of included competencies*‘The ACT possesses the specialist knowledge, skills and behaviours to…’ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Case Identification/alcohol identification and brief advice (IBA) | 1 | Oversee the provision of training to deliver IBA in the hospital. It is able to provide leadership in relation to professional development requirements, identifying local champions and ensuring access to appropriate resources including written information |

| 2 | Triage & comprehensive alcohol assessment | 2–12 | Undertake an appropriate assessment of the patient’s condition |

| a. Triage Assessment | 4 | Make an assessment to prioritise care, understand importance of information from third parties, and act on risk. | |

| b. Comprehensive Assessment | 2 | Conduct a comprehensive alcohol assessment and monitor progress. | |

| c. Goals and Care Planning | 5 | Work with patients to inform an appropriate and acceptable management plan. | |

| 3 | Specialist nursing and medical care planning | 13–32 | Provide the specialist advice and care to facilitate evidence based, high quality treatment across the hospital system. |

| a. Implementing Planned Care | 2 | Determine an appropriate treatment plan and facilitate implementation | |

| b. Advisory Roles and Functions | 15 | Support the management of patients with the most complex needs in a wide range of clinical situations. | |

| c. Relapse Prevention | 3 | Ensure patients with moderate/severe dependence are assessed appropriate relapse prevention medication. | |

| 4 | Management of medically-assisted alcohol withdrawal (MAAW) | 33–50 | Oversee the identification and management of all aspects of medically assisted withdrawal, and its complications, across a range of clinical presentations |

| 5 | Provision of psychosocial interventions | 51–56 | Offer evidence based psychosocial interventions based on a sound knowledge of the theories and treatment of addiction |

| a. Provision of Motivational Enhancement Therapy | 4 | Deliver a range of psychosocial approaches to engage patients to address their AUD | |

| b. Supporting Families | 2 | Assess the needs of carers and families and what is available to them locally | |

| 6 | Planning safe discharge, including referral to community services | 57–62 | Facilitate the safe discharge and/ transfer of care to the community, working with relevant professionals, agencies and carers as appropriate |

| 7 | Clinical leadership by a senior clinician with dedicated time for the team | 63–68 | Work strategically with key stakeholders within the hospital system and wider community, to monitor the effectiveness of treatment pathways and develop evidence-based research |

| 8 | Provision of trust-wide education and training in relation to alcohol | 69–72 | Set up and run educational and training modules for all staff in the identification and management of alcohol use disorders |

*For full statement list see Supplementary Table 2

DISCUSSION

Drawing on the existing published resources and clinical experience, the expert panel provided consensus on the core clinical competencies required for ACTs in caring for hospitalized patients with alcohol use disorders. As the composition of current provision is variable (Public Health England, 2014), the identified clinical competencies provide a benchmark for the recruitment, training and support for ACTs.

A suitably qualified workforce drawn from different professional groups will be required to deliver the eight components of alcohol care teams and related competencies described here. The development of multidisciplinary alcohol care teams in accordance with these clinical competencies will require professionals to be proficient in the assessment and treatment of alcohol use disorders and related complications in addition to possessing knowledge and expertise in the application of relevant legislation pertaining to the mental capacity and safeguarding. It will be essential that ACT staff are able to quickly develop therapeutic working relationships with patients and their families and carers through the use of effective communication skills and promotion of patient-centred care. The requirements to train other health professionals in the care of AUD extend the role of the ACT into the provision of health promotion, training and teaching of specialist clinical skills across a diverse non-specialist workforce. Effective leadership is a prerequisite for the implementation of evidence-based practice through the development of applied research across health systems and outside more specialist addiction services with potentially different patient characteristics. Strategic vision for the development of an ACT within any healthcare system will require collaboration with other care providers and funders to ensure the needs of the target population are addressed, and outcomes reported. Successful implementation of an ACT based on this NHS model will require appropriate training and organizational support from the hospital management team (Johnson et al., 2010; Makdissi and Stewart, 2013; Moriarty, 2019).

These competencies were structured around the ACT core service descriptors, incorporating skills, knowledge and attitudes. Generic statements relating to the attitudes and values required for professional practice, working with this group, are implicit in the competencies defined. A strength, and possible limitation of this study, was the literature search to support the focus of the expert panel. Rather than using multiple rounds and iterations to generate statements de novo by the panel, this study used existing national guidelines and professional practice standards to inform the initial drafting of an over inclusive set of potentially relevant clinical competencies, drawn from related addiction literature. Whilst this identifies a possible selection bias, the information collected by the research team was drawn from a wide variety of evidence-based resources, including specific practice standards indicating a pre-existing level of consensus across professional groups and national guidance. This enabled a more focussed debate, which identified additional clinical competencies for review. Panel membership consisted primarily of specialist alcohol nurses and four doctors, whilst a different matrix of professions may have identified alternative competencies; the eight core clinical components provided a clear structure within which to work, and the final set of competencies was similar to those outlined by the British Society of Gastroenterology (NICE, 2016). A strength of employing Delphi principles was that a range of experts in a specific area, and our high threshold for consensus (everyone rating each statement at least 4 or more) over a number of iterations, means the 72 competencies agreed upon are likely to be robust.

Future research should focus on assessing the current hospital-based workforce against these competencies to determine the existing training needs of staff providing specialist care. Ensuring robust processes whereby skills can be acquired and clinical quality of ACTs assessed is an essential next step in developing this clinical service framework.

Globally, much of the evidence comes from patients managed in specialist addiction services, and so there is a need to test the validity of the currently accepted evidence in patient groups managed in acute settings, who may have very different clinical characteristics. The development of ACTs able to consistently deliver and evaluate interventions in this group is an important step.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This is an independent research funded by NHS England and Improvement with support from Public Health England and the Royal College of Psychiatrists. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, Department of Health or Royal College of Psychiatrist. TP is part-funded by National Institute for Health Research, Clinical Research Network for Yorkshire and The Humber.

Members of the Alcohol Care Team Clinical Competency Expert Panel were Annabel Bouteloupe Wandsworth Consortium Drug and Alcohol Service; Gill Campbell Turning Point; Prof Carmel Clancy Middlesex University and International Nurses Society on Addictions; Arlene Copland Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust; John Crome Essex Partnership University Trust; Dr Ed Day University of Birmingham Institute for Mental Health; Dr Jonathan Dewhurst Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust; Louise Dunn University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust; Judith Durkin County Durham Drug and Alcohol Recovery Service, Spectrum CIC; Anya Farmbrough University Hospitals Southampton NHS Foundation Trust; Ms Moya Forsythe Better Lives, Islington’s Drug and Alcohol Service; David Henstock Derbyshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust; Mark Holmes Humankind Charity; Claire James Change Grow Live; Dr Nicola Kalk South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London; Christopher McGowan Whiston Hospital; Dr Kieran Moriarty British Society of Gastroenterology; Louisa Morley Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust; Nicola Oldham Pinderfields Hospital; Dr Margaret Orange Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust; Dr Lynn Owens Royal Liverpool Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust and The University of Liverpool; Ms Shantelle Quashie Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, Dr D G Taylor West London NHS Trust; and Graeme White Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

FUNDING

This project was funded by NHS England and Improvement with support from Public Health England and the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

GOVERNANCE AND ETHICS

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and was evaluated by, and considered exempt from, ethical committee oversight at the University of Southampton.

CONTRIBUTIONS

JS devised the study with TP advising on the methods. TP conducted the search strategy with TP and JS independently rating the practice statements against inclusion/exclusion criteria. JS facilitated and AP co-ordinated the panel meeting and collection of data from experts. TP drafted the manuscript with contributions from JS and AP.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

References

- Brennan A, Hill-McManus D, Stone T et al. (2019) Modeling the potential impact of changing access rates to specialist treatment for alcohol dependence for local authorities in England: the specialist treatment for alcohol model (STreAM). J Stud Alcohol Drugs 96–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby J, Purdy S, Hollingworth W (2017) How do population, general practice and hospital factors influence ambulatory care sensitive admissions: a cross sectional study. BMC Fam. Pract. 18:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Jackson R, Guillaume L et al. (2010) Barriers and facilitators to implementing screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. J. Public Health 33:412–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission (2019) Substance Use chart abstracted measures available via: https://www.jointcommission.org/measurement/measures/substance-use/ [Accessed 15 Dec 2019]

- Jones L, Bellis MA (2013) Updating England-Specific Alcohol-Attributable Fractions. Liverpool: Centre for Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics 363–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D et al. (2009) Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend. 99:280–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makdissi R, Stewart SH (2013) Care for hospitalized patients with unhealthy alcohol use: a narrative review. Addict Sci Clin Pract 8:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty KJ. (2011) Collaborative liver and psychiatry care in the Royal Bolton Hospital for people with alcohol-related disease. Front Gastroenterol 2:77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty KJ. (2019, 2019) Alcohol care teams: where are we now? Frontline gastroenterology. Front Gastroenterol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS England (2019) The NHS Long-Term Plan. London: NHS England. [Google Scholar]

- NHS England & Improvement (2019) Alcohol Care Teams: Core Service Descriptor. NHS England & Improvement and Public Health England; Available at:https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ACT-core-service-descriptor-051119.pdf [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016) Quality and productivity: proven case study In Alcohol Care Teams: Reducing Acute Hospital Admissions and Improving Quality of Care. The British Society of Gastroenterology and the Royal Bolton Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips T, Coulton S, Drummond C (2019) Burden of alcohol disorders on emergency department attendances and hospital admissions in England. Alcohol Alcohol. 54:516–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England (2014) Alcohol Care in England's Hospitals: An Opportunity not to be Wasted. London: Public Health England. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts E, Drummond C (2019) Alcohol related hospital admissions: locking the door after the horse has bolted. BMJ Opin 07available via https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2019/07/30/alcohol-related-hospital-admissions-locking-door-horse-bolted/. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts E, Morse R, Epstein S et al. (2019) The prevalence of wholly attributable alcohol conditions in the United Kingdom hospital system: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Addiction 114:1726–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche AM, Freeman T, Skinner N (2006) From data to evidence, to action: findings from a systematic review of hospital screening studies for high-risk alcohol consumption. Drug Alcohol Depend. 83:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R, Alexander G, Armstrong I et al. (2018) Disease burden and costs from excess alcohol consumption, obesity, and viral hepatitis: fourth report of the lancet standing commission on liver disease in the UK. Lancet 391:1097–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (1992) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2019) Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.