Abstract

Context:

RJ is a natural bee product and is known to have remarkable health benefits. The objective was to evaluate its antimicrobial potential against periodontopathic bacteria and compare the same with chlorhexidine.

Aims:

The aim was to evaluate and compare the antimicrobial activity of royal jelly (RJ) with chlorhexidine against the periodontopathic bacteria (aerobic and anaerobic) in subgingival plaque.

Materials and Methods:

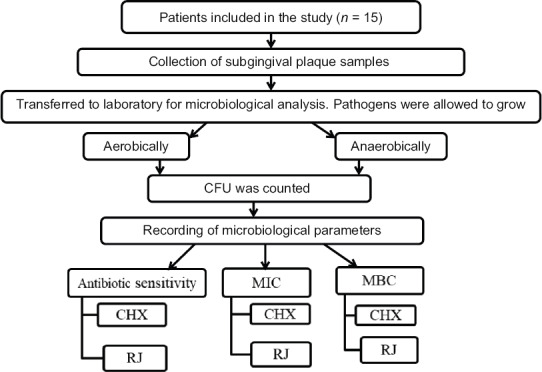

Subgingival plaque samples of 15 chronic periodontitis patients were taken, and clinical parameters were evaluated. Inhibitory effect of RJ and chlorhexidine was investigated “in vitro” on the growth of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria by colony count, minimum inhibitory concentration, and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) by the method of serial broth dilution.

Statistical Analysis Used:

ANOVA statistical analysis was used in this study.

Results:

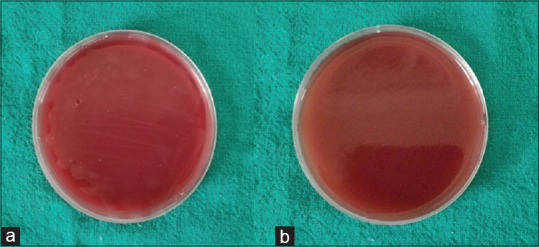

Subgingival anaerobic bacteria predominate (colony-forming unit). Chlorhexidine is more sensitive in inhibiting aerobic and anaerobic bacteria (at concentration 50 μg/100 μl). A higher concentration of RJ is required to have an inhibitory effect. MBC of chlorhexidine shows no growth on blood agar plates, whereas minimum bacterial growth is seen around the RJ.

Conclusions:

Chlorhexidine (gold standard) has a higher inhibitory effect in the case of chronic periodontitis; however, RJ can also be used as an alternative but at higher concentration and lesser dilution. Evaluation of the quality, quantity and the biological activity of RJ is a necessity and must be done before its “in vivo” application.

Keywords: Aerobic bacteria, anaerobic bacteria, chlorhexidine, royal jelly

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease is a multifactorial inflammatory disease of the dentogingival complex that is associated with subgingival biofilm consisting mainly of anaerobic bacterial species. The documented clinical experiments indicate that certain periodontopathogens, most of which are anaerobes, when present even in very small quantities effectuate inflammation of the periodontium. The key periodontopathogens, such as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Tannerella forsythia, and Porphyromonas gingivalis, are conceptualized to be one of the factors that are strongly associated with the pathogenesis of the active periodontitis.[1] The clinical evidence shows that deep periodontal pockets and significant attachment loss can be considered as characteristic manifestations of chronic periodontitis.[2]

The treatment aims at reducing the utter periodontal load by supragingival and subgingival mechanical debridement along with antibiotic therapy as an adjuvant.[3] The evolution of antimicrobial resistance is a global concern that is threatening our ability to provide treatment, resulting in high morbidity, high mortality, and increased health-care costs.[4] To minimize the emergence and spread, attention has been accorded toward research and development of newer antimicrobials derived from nature. Furthermore, efforts have been made for the development of contemporary methods for the prevention and treatment of periodontal disease and to discover alternatives of antibiotics that will exclude their excessive use as they have their side effects.[3]

Throughout human history, there has been enormous use of natural products in medicine. One such natural medicine is “apitherapy” that involves the use of honeybee products for health benefits. Apitherapy or “bee therapy” (from the Latin word “apis” which means “bee”) is referred to as an alternative branch of medicine that involves the art and science of treatment and healing through products made by honeybees. This includes the use of honey, propolis, pollen, royal jelly (RJ), and bee venom.[5] The utility of honeybee products has won considerable attention over the past few years for their effective antibacterial potential.

RJ, or bee's milk, is a creamy product secreted by the hypopharyngeal and mandibular salivary glands of worker bees Apis mellifera (Apidae) for the nourishment of bee larvae from hatching till the 3rd day of life and queen bees for the entire life. It is a yellowish-white, viscous secretion with a characteristic smell of phenol and is highly acidic in nature (PH value: 3.4–4.5).[6] It possesses numerous beneficial medicinal properties among which the quality of being an antimicrobial is emphasized in this study.[7] The glandular secretion is chemically composed of mostly water, followed by proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, vitamins, and minerals.[3] Protein components that have significant antimicrobial potential are major RJ proteins, royalisin, jellenies, and enzymes such as glucose oxidase. These are effective antimicrobials against Gram-positive bacteria; jellenies are also effective against Gram-negative bacteria and yeasts.

Chlorhexidine being a gold standard antiplaque agent is a potent inhibitor of bacteria due to its bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity. Its superior antiplaque action is attributed to the property of substantivity. However, long-term use is not encouraged due to its side effects such as staining and reduced taste sensation which can be surmounted by RJ.[8]

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) is the lowest concentration of antimicrobial agent that will inhibit the visible growth of bacteria after overnight incubation (this period is extended for anaerobes as they have longer incubation time). Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) is the lowest concentration of antimicrobial agent that will prevent the growth of bacteria after subculturing on antibiotic-free media.[3]

Clinical relevance of the study

This study aims to put forward a new herbal product RJ, which has antimicrobial properties by evaluating and comparing the antimicrobial activity of RJ with that of chlorhexidine against periodontopathic bacteria (aerobic and anaerobic) in subgingival plaque by carrying out antimicrobial sensitivity test, MIC, and MBC.

The results of the study proved that the RJ was capable to inhibit the bacteria found in the subgingival plaque. It has more efficacy for anaerobic bacteria and can combat the periodontopathogens. Therefore, it can be used as a successful alternative to synthetic antimicrobials. The dosage and safety of RJ must be considered before its possible in vivo application for successful nonsurgical therapeutic modality of the management of chronic periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients reporting to the department of periodontology with the chief complaint of bleeding gums and gingival recession were included in the study. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the institution. Clinical parameters taken in consideration were determination of pocket depth using Williams probe, calculating plaque index and gingival index.[9,10] Systemically healthy individuals who were diagnosed with chronic periodontitis, having probing pocket depth of >5 mm, plaque index of 2 or 3, gingival index of 2 or 3, and community periodontal index (CPI) of 3 or 4, were included in the study.

Patients using antibiotics in the past 6 months who underwent scaling in the past 6 months, patients who were allergic to active ingredients, pregnant or lactating women, and patients undergoing any surgical procedure of periodontal or gingival diseases were excluded from the study.

The RJ tablets of 0.6 g each were used which were commercially available (by forever living).

The 0.6 g of chlorhexidine was used for each sample size.

A total of 15 patients having chronic periodontitis were included in the study. Subgingival plaque of patients was collected with the help of cotton swabs or with a probe [Figure 1] stored in phosphate-buffered saline solution and transferred to the laboratory within an hour for microbiological analysis of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria along with antibiotic sensitivity and minimum inhibitory and bactericidal concentration. Samples were vortexed for 10s, and a series of four 10-fold dilutions of each sample were prepared. Ten milliliters of each dilution was seeded on brain–heart infusion (BHI) agar plates and trypticase soy agar plates and labeled. A sample on BHI media was incubated for 2–4 days at 37°C under aerobic conditions for aerobic bacteria and yeasts, under 5%–10% carbon dioxide (CO2) atmosphere for aerobic/anaerobic facultative bacteria. The sample inoculated on trypticase soy agar media was incubated for 5–9 days at 37°C under strictly anaerobic conditions within an anaerobic system (N2 85%, H2 5%, and CO2 10%) using anaerobic gas jar and gas pack for anaerobe obligate and facultative bacteria. Following the incubation period, a number of colony-forming units (CFUs) were counted using a colony counter.

Figure 1.

Collection of subgingival plaque

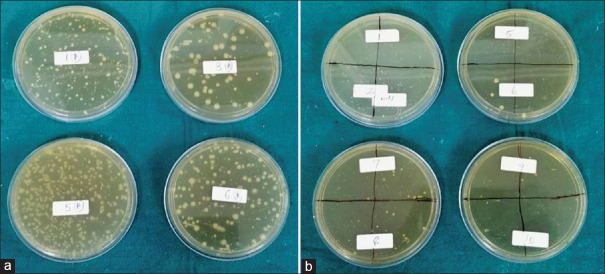

The number of black-pigmented CFUs was counted on plates both from aerobic and anaerobic conditions. CFU was calculated as the number of colonies per 10 μl at the minimum dilution with clear, separate, and countable colonies.

The antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by referring Kirby–Bauer standard disk diffusion method, using antimicrobial disks of chlorhexidine and RJ. These tablets were inoculated on the BHI media plates showing the growth of aerobic bacteria and on trypticase soy agar media plates showing the growth of anaerobic bacteria. Further plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and the sensitivity of these tablets was determined by calculating the inhibition zone using Vernier caliper around these tablets.[11,12]

MIC was done to determine the efficacy of RJ over chlorhexidine using a broth dilution method. In the initial tube, 380 μl of BHI broth and 20 μg of RJ were added. Nine dilution samples of BHI broth were prepared. 200 μl of BHI broth was added in all nine sample tubes. In the first sample tube, 200 μl of dilution from the initial tube was added, and this was considered as 10−1 dilution. From a 10−1 diluted tube, 200 μl was transferred to the second tube to make 10−2 dilution. The serial dilution was repeated up to 10−9 dilution for each sample. Similar serial dilutions were made for chlorhexidine also.

From grown plates of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, the colony was taken and added into 2 mL of BHI broth. In each serially diluted tube of RJ and chlorhexidine, 200 μl of both aerobic and anaerobic culture suspensions was added. These tubes were incubated for 24 h at 37° C, and turbidity was observed.[13]

Further, to check for the MBC, the dilutions of MIC showing sensitivity were inoculated on blood agar for 24 and 48 h at 37°C for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, respectively, and checked for the growth obtained.

RESULTS

The values obtained for the clinical parameters of the 15 patients examined and included in the study were as follows: pocket depth ≥5 mm, plaque index 2 or 3, gingival index 2 or 3, and CPI 3 or 4.

The collected subgingival plaque samples from the patients when inoculated on BHI agar and trypticase soy agar media showed the growth of both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, respectively. Results were expressed as mean colony functional units (± standard deviation) of total bacteria.

Results showed that the mean of CFU of aerobic bacteria at four-fold dilution is 55.8 CFU and for anaerobic bacteria at four-fold dilution is 262.8, which are statistically significant (P < 0.05) indicating a predomination of anaerobic bacteria in subgingival plaque as compared to aerobic bacteria [Table 1 and Figure 2]. Moreover, there was more isolation of Gram-positive bacteria (aerobic and anaerobic) than Gram-negative bacteria (aerobic and anaerobic), which was confirmed by Gram's stain.

Table 1.

Mean of colony-forming unit in both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria

| Type of bacteria | Mean of CFU | P |

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic bacteria | 55.8×10-4 | ≤0.05 (significant) |

| Anaerobic bacteria | 262.8×10-4 |

P≤0.05 is considered statistically significant. CFU – Colony-forming unit

Figure 2.

(a) Growth of anaerobic bacteria on trypticase soy agar media (b) Growth of aerobic bacteria on brain–heart infusion agar media

Disks of chlorhexidine and RJ were used in this study to check the sensitivity of aerobic and anaerobic bacterial colonies. This was determined as a clear halo was formed around the disks. Formed clear halo is measured using a Vernier caliper from the center of the tablets to the periphery of the halo. Results showed that inhibition zone formed around chlorhexidine tablets on anaerobic bacteria was 7 mm, whereas inhibition zone around RJ tablets on anaerobic bacteria was 9.75 mm indicating the effectiveness of RJ tablets in inhibiting the growth of anaerobic bacteria in comparison to chlorhexidine, or in other words, anaerobic bacteria are more sensitive to RJ tablets in comparison to chlorhexidine [Figure 3].

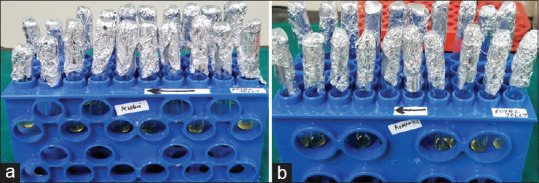

Figure 3.

Antibiotic sensitivity test inhibition zone around chlorhexidine tablet (pink) is 7 mm; inhibition zone around royal jelly tablet (orange) is 9.75 mm

The MIC of RJ and chlorhexidine was checked for both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. RJ showed clear inhibitory effects for both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria at dilution 25 μg/ml and 12.5 μg/ml, respectively, whereas chlorhexidine showed a clear inhibitory effect at 3.25 μg/ml dilution for anaerobic bacteria and at 6.25 μg/ml dilution for aerobic bacteria [Table 2 and Figure 4]. These results indicated that a higher concentration of RJ is required to show its inhibitory effects on both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in comparison to chlorhexidine.

Table 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentration of royal jelly and chlorhexidine obtained for anaerobic and aerobic bacteria at varying dilutions

| Type of bacteria | 100 | 50 | 25 | 12.5 | 6.25 | 3.25 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic | ||||||||||

| Royal jelly | S | S | S | S | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Chlorhexidine | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | R | R | R |

| Aerobic | ||||||||||

| Royal jelly | S | S | S | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Chlorhexidine | S | S | S | S | S | R | R | R | R | R |

S – Sensitive; R – Resistant

Figure 4.

Minimum inhibitory concentration of royal jelly and chlorhexidine obtained for anaerobic (a) and aerobic bacteria (b) at varying dilutions

Further dilution which was sensitive for RJ and chlorhexidine (range: 3.25 μg/ml to 100 μg/ml) to anaerobic bacteria was inoculated on blood agar plates. No growth was seen for chlorhexidine dilutions, whereas the minimum growth was seen for RJ dilutions [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Minimum bactericidal concentration showing no growth for (a) chlorhexidine and minimum growth for (b) royal jelly

DISCUSSION

Chronic periodontitis is a multifactorial infection that results in the destruction of periodontal tissues. The primarily important etiological agent of chronic periodontitis is bacterial plaque, which harbors a variety of pathogenic bacteria known as periopathogens or periodontopathogens. The key periopathogens responsible are anaerobic bacteria as follows: Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Tannerella forsythia, Treponema denticola, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and the relative anaerobe Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. The main clinical manifestations of chronic periodontitis are gingival inflammation, the presence of periodontal pockets, connective tissue attachment loss, and subsequent loss of alveolar bone. Subgingival biofilm harbors bacteria, specifically anaerobic bacteria. They cause inflammation by acting on fibroblasts, epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and extracellular matrix components. They also stimulate the production of inflammatory mediators by affecting the immune cells.[2]

Gram-positive bacteria being the early colonizers are present in the initial course of the disease. As the inflammation progresses, Gram-negative bacteria dominate, and the Fusobacterium nucleatum plays a crucial role as a bridging microorganism. The probable reason for the predominance of the anaerobic bacteria in the subgingival plaque is that early colonizers consume oxygen, and therefore, there is an overall reduction in the level of free oxygen in the biofilm environment which is favorable for the growth of anaerobes. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia are the pathogenic bacteria found in mature plaque at sites that exhibit progressing periodontitis. As the gingival inflammation progresses, there is a subsequent increase in the number of subgingival bacteria and also their invasion in the pocket epithelium and underlying tissues.[1]

Further, in our study, we evaluated the antimicrobial property of RJ and compared it with that of chlorhexidine. In the antibiotic sensitivity test, inhibition zone was formed around both RJ and chlorhexidine tablets indicating their antimicrobial property in inhibiting the anaerobic bacteria. No such inhibition zones were seen around aerobic bacteria as the growth of aerobic bacteria is very less in the subgingival plaque. The results of our study are in accordance with the study done by Jain et al. in the year 2016 where they explained the inhibitory properties of chlorhexidine which is the proven most effective antiplaque agent. It has bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects along with the property of substantivity in the oral cavity.[11] Any bacteria adhering to the tooth surface are challenged by chlorhexidine molecules by altering the integrity of the cell membrane of bacteria. This bacteriostatic effect of this bisbiguanide is what makes it the gold standard.[8] Therefore, it has been put forth that chlorhexidine acts by damaging the cell membrane of prokaryotes and by disrupting the cytoplasmic constituents.

Moreover, along with the gold standard, the antimicrobial properties of RJ were also explained which are due to high osmotic pressure, physical properties, and enzymatic glucose oxidation reaction. Due to its high osmotic pressure, it can extract water from bacterial cells and cause them to die. Possible mechanisms that are responsible for the inhibitory activity of RJ are due to the presence of flavonoids and hydrogen peroxide. Its low pH and high osmolarity are due to its sugar concentration. All types of saturated sugar syrups tend to reduce microbial growth due to their high osmolarity. Hydrogen peroxide is the main antibacterial substance produced by an enzymatic reaction from honey. According to Jain et al. honey-based product, RJ had shown the greatest antibacterial activity at 100% concentration.[14]

MIC and MBC are significant diagnostic aids to confirm the resistance of microbes to antibacterial drugs and also to monitor the efficacy of newer antimicrobials. Bacterial species express varying MICs and MBCs with different antimicrobials. Sensitive strains will have relatively lower values in comparison with resistant strains. The stipulated concentration of antimicrobial drug in the blood should exceed the MIC by a factor of 2–8 times to offset the tissue barriers that restrict access to the infected site. In the present study, the MIC and MBC values of chlorhexidine and RJ were obtained for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.

The present in vitro antibacterial assessment study is focused on an interventional approach designed to conduct a clinical trial for detecting the beneficial effects of RJ on patients at risk for periodontitis. However, in vitro values of MIC and MBC may not hold good for in vivo studies due to their inherent limitations. The growth of microorganisms in vitro is exponential, whereas the growth in vivo can be very slow to none. MIC and MBC do not indicate the true activity of the drug at the locus of infection, in vitro MIC and MBC serves as substitute markers attempting to quantify the drug activity.

The most preferred treatment modality for periodontal disease is mechanical debridement of biofilm. However, mechanical removal of biofilm cannot completely remove all periodontal pathogens from the tooth surface due to the anatomical complexity of the roots (furcation areas and root concavities) and bacteria invading the periodontal supporting tissue. Therefore, systemic or local antibiotics are employed to overcome this problem. However, antibiotic resistance exhibited by biofilm is a global concern.[11] Thus, as per the results obtained, it was concluded that the RJ was active against the periodontal pathogens tested and it has a high efficacy as an antimicrobial agent for anaerobic bacteria present in subgingival plaque. Since RJ is an herbal product and has minimal side effects, it can work in synergism with chlorhexidine and other antiplaque agents as well. The requirement for a standardized method for quality evaluation of RJ, i.e., qualitative, quantitative, and biological activity, is a necessity. Furthermore, the dosage and safety of RJ must be tested before its possible in vivo application.

Clinical relevance of the study

The study aims to highlight the medicinal use of a new herbal product RJ which has antimicrobial properties. This study evaluates the antimicrobial potential of RJ and also compares it with the antimicrobial potential of gold standard chlorhexidine. This is evaluated by performing microbiological analysis and tests such as antibiotic sensitivity, MIC, and MBC [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

The figure represents a flowchart depicting the study design

The results of the study show that the RJ is capable to inhibit the bacteria found in the subgingival plaque. It has more efficacy for anaerobic bacteria and can combat the periodontopathogens. Therefore, it can be used as a successful alternative to synthetic antimicrobials.

The dosage and safety of RJ must be considered before its possible in vivo application for successful nonsurgical therapeutic modality of the management of chronic periodontitis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Popova C, Dosseva-Panova V, Panov V. Microbiology of periodontal diseases. A review. Biotechnol Biotec Eq. 2013;27:3754–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zkaradkiewicz KA, Karpinski MT. Microbiology of chronic periodontitis. JBES. 2013;3:M14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coutinho D, Karibasappa NS, Mehta SD. Royal jelly antimicrobial activity against periodontopathic bacteria. J Interdiscip Dent. 2018;8:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gambogou B, Khadimallah H, Bouacha M, Ameyapoh YA. Antibacterial activity of various honey monofloral and polyfloral from different regions of algeria against uropathogenic Gram-negative bacilli. J Apither. 2018;4:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahuja V, Ahuja V. Apitherapy – A sweet approach to dentaldiseases – Part I: Honey. J Adv Dent Res. 2010;1:2229–4112. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balkanska R, Zhelyazkova I, Ignatova M. Physico-chemical quality characteristics of royal jelly from three regions of Bulgaria. JASTA. 2012;4:302–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavel IC, Marghitas AL, Bobis O, Dezmirean SD, Sapcaliu AA, Radoi I, et al. Biological activities of royal jelly – Review. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2011;44:108–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azeez AR, Mahmood MS, Mahmood W. The effect of chlorhexidine mouth wash and visible blue light on Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis of patients with chronic periodontitis (an in-vitro study) IOSR-JDM. 2014;13:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Löe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38(Suppl):610–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hefti AF. Periodontal probing. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1997;8:336–56. doi: 10.1177/10454411970080030601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biemer JJ. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing by the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1973;3:135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balouiri M, Sadiki M, Ibnsouda SK. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J Pharm Anal. 2016;6:71–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews JM. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48(Suppl 1):5–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.suppl_1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain A, Bhaskar DJ, Gupta D, Agali C, Gupta V, Gupta RK, et al. Comparative evaluation of honey, chlorhexidine gluconate (0.2%) and combination of xylitol and chlorhexidine mouthwash (0.2%) on the clinical level of dental plaque: A 30 days randomized control trial. Perspect Clin Res. 2015;6:53–7. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.148819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]