Abstract

Drug-induced serious adverse reaction is an unpleasant event with high rate of mortality. Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis are most common among the serious adverse drug reactions. There is no selective drug therapy for the management of serious adverse drug reactions-associated mucocutaneous blisters. The use of N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of mucocutaneous blisters has limited evidence worldwide. Three cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis or Stevens–Johnson Syndrome-associated mucocutaneous blisters are presented in this study where intravenous N-acetylcysteine (600 mg, every 8 h) was given in early hospitalization hours for the treatment of mucocutaneous fluid-filled blisters. Here, one patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis received intravenous immunoglobulin along with intravenous N-acetylcysteine and the other two patients (toxic epidermal necrolysis/Stevens–Johnson Syndrome) received only N-acetylcysteine intravenously. In response, mucocutaneous fluid-filled blisters stopped progressing within 48 h and were healed within 2 weeks of admission in the intensive care unit. Thus, intravenous N-acetylcysteine with or without having intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of serious adverse drug reactions-associated mucocutaneous blisters may be an effective therapeutic option for better clinical outcome.

Keywords: Serious adverse drug reactions, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, mucocutaneous blister, N-acetylcysteine

Introduction

Serious adverse drug reactions (SADRs) are defined as drug-induced noxious and unintended life-threatening events with a high rate of mortality.1 Cutaneous disorders are immune-mediated reactions, manifest in 10%–30% of all adverse drug reactions (ADRs),2 and occur in 2%–3% of all hospital admitted patients.3 Severe skin lesions such as mucocutaneous blisters due to SADRs, including Stevens–Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), are the serious consequences of the drug reaction considered as life-threatening event.2 These mucocutaneous fluid-filled blisters are very painful, act as the source of secondary infections, and at present, except some supportive medications, there is no standard drug therapy for the treatment of these severe skin lesions.2,3

N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a cysteine derivative, is used as an anti-inflammatory agent, mucolytic agent, antioxidant, and precursor of glutathione (GSH) synthesis.4 Use of NAC in the effective management of SJS/TEN-induced mucocutaneous blisters is an uncommon practice. Here, we present three SADR cases (two TEN cases and one SJS case) where mucocutaneous blisters were early treated with intravenous NAC-associated therapeutic management, successfully.

Case 1

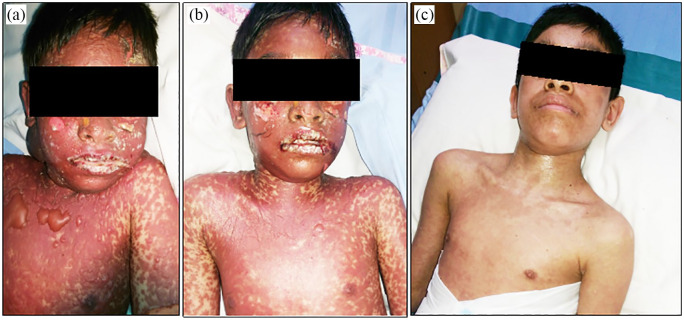

A 16-year-old girl admitted in our intensive care unit (ICU) with a history of taking cefuroxime /clavulanic acid (500 mg/125 mg, every 12 h, orally) 3 days ago at home, and after 48 h, she developed cefuroxime-induced TEN manifested by fluid-filled mucocutaneous blisters all over her body; hemorrhagic crusting of the vermillion zone of the lips (Figure 1(a)) with oral mucosal bleeding; and bilateral conjunctivitis. At the time of admission, she was found with fever (101°F), mild respiratory distress, increased heart rate (125 beats/min), elevated serum bilirubin level (2.4 mg/dL), increased serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level (30 mg/dL), increased serum creatinine level (2.1 mg/dL), raised serum bicarbonate level (24 mEq/L), raised blood pH (7.49), myalgia, and altered level of consciousness with a reduced Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score (E3V4 M4). Some large fluid-filled blisters were erupted revealing painful raw areas. Approximately 50%–55% of the total body surface area (estimated) of that patient was detached due to the reaction. Her calculated severity-of-illness score in toxic epidermal necrosis (SCORTEN) scale value was 3, estimating a 35.3% chance of mortality. Intravenous NAC (600 mg, every 8 h) was started within 2 h after admission for blister treatment. In addition to NAC, she also received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG; dose: 1 g/kg of body weight for 2 consecutive days). Within 2 days of admission, all the blisters stopped progressing (Figure 1(b)), oral-mucosal bleeding stopped, and no new blister regenerated. She was discharged from ICU on her 12th day of ICU admission, while significant re-epithelialization of the erupted skin (Figure 1(c)) was found all over her body.

Figure 1.

(a) Mucocutaneous blisters at the time of admission in ICU. (b) Healing of fluid-filled blisters after 48 h of admission. (c) Complete re-epithelialization of the lesions on 12th day of admission.

Case 2

A 12-year-old boy had a history of taking intravenous Ceftriaxone (1 g, every 24 h) 2 days before developing TEN at another hospital. On the second day of the development of TEN-event, he got admission in our pediatric ICU, and was found with fluid-filled mucocutaneous blisters in his chest, face, and neck; hemorrhagic crusting of the vermillion zone of the lips (Figure 2(a)) with oral mucosal bleeding; and bilateral conjunctivitis. In addition, he had fever (101°F), myalgia, increased heart rate (130 beats per minute), mild respiratory distress, increased serum creatinine level (1.9 mg/dL), increased serum BUN level (33 mg/dL), elevated serum bicarbonate level (26 mEq/L), raised blood pH (7.51), and reduced consciousness level (GCS score: E3V4 M5). Approximately 35%–40% of total body surface area (estimated) of that patient was detached due to the reaction. His calculated SCORTEN scale value was 3, which estimated 35.3% chance of mortality. On day 1 in ICU, early NAC (600 mg, intravenously, every 8 h) was started for the treatment of TEN-induced blisters. Due to financial inability, the patient did not agree to receive IVIG on doctor’s advice. After 48 h, the progression of the fluid-filled blisters stopped and no further blister developed (Figure 2(b)). A significant recovery of skin eruptions (Figure 2(c)) was found on day 9 of NAC therapy and he was discharged after 16 days of NAC-therapy.

Figure 2.

(a) Mucocutaneous blisters at the time of admission in ICU. (b) Healed blisters after 48 h of admission. (c) Day 9 of admission with complete re-epithelialization of the lesions.

Case 3

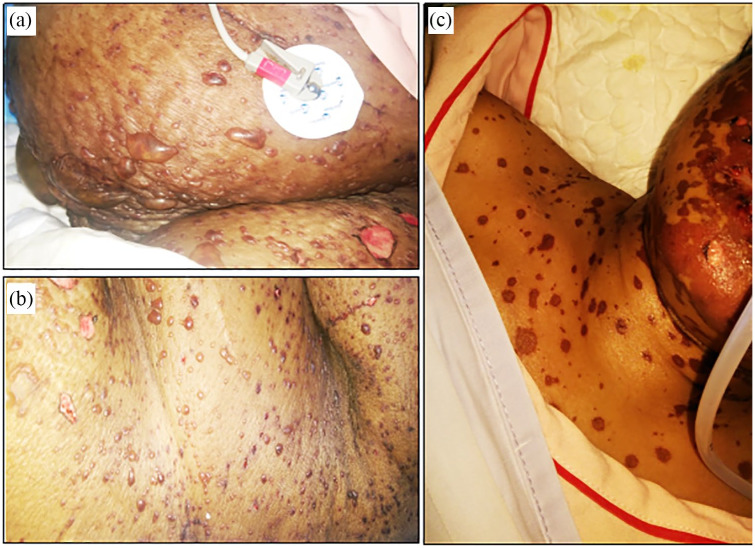

A 52-year-old female patient experienced phenytoin-induced SJS, and was admitted in our ICU with mucocutaneous fluid-filled blisters mostly in her chest, abdomen, and face (Figure 3(a)); oral mucosal bleeding; and bilateral conjunctivitis. She had premorbid hypertension, but no history of diabetes. During admission, she was found with elevated level of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT; 328 IU/L), increased serum bilirubin level (1.9 mg/dL), fever (102°F), mild respiratory distress, tachycardia (140 beats per minute), elevated serum creatinine level (2.4 mg/dL), raised blood pH (7.50), increased blood glucose level (17.2 mmol/L), myalgia, and altered level of consciousness with a declined GCS score (E4V3 M5). Less than 10% of total body surface area (estimated) of that patient was detached due to the reaction. Intravenous NAC (600 mg, intravenously, every 8 h) was given to the patient within 4 h of admission in ICU. Doctor advised IVIG with intravenous NAC, but the patient declined the use of IVIG because of her financial inability. Within 48 h of ICU admission, the blisters stopped further progression (Figure 3(b)), no new blister was formed, and hepatic functions returned to the normal range. A significant improvement in the healing of blisters was observed on day 4 (Figure 3(c)) with NAC therapy, clinically she was found sound, and was discharged to the general ward after her 12th day of admission in the ICU.

Figure 3.

(a) Mucocutaneous blisters at the time of admission in ICU. (b) Healed blisters after 48 h of admission. (c) Day 4 of admission with suppressed skin lesions.

Discussion

Drug-induced SADRs including SJS or TEN are potential life-threatening reactions most frequently characterized by extensive epidermal and mucosal epithelial destruction.1,2 In TEN, skin involvement is >30%, whereas in SJS it is <10%, and SJS/TEN overlap is involved with 10%–30% of the total body skin.1,2 SADRs can be developed even by single drug product manifesting common clinical features, including acute mucocutaneous skin lesions, hemorrhagic crusted lips, oral mucosal bleeding, and conjunctivitis.5 In our reported three cases, these common features were present significantly.

Early hospitalization, age of the patient, and total affected skin area mostly regulates the mortality rate in SJS/TEN.2 The study showed that in 74%–94% of SADRs cases, the reaction was triggered by medications and antibiotics were found to be the most common cause.5 Our two TEN (case 1 and case 2) cases were triggered by antibiotics—cefuroxime/clavulanic acid and ceftriaxone, and case 3 (SJS) was triggered by phenytoin.

SJS and TEN are delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions triggered by drugs and are primarily manifested with “influenza-like” symptoms including malaise and fever, followed by painful cutaneous lesions, mucosal bleeding, and other systemic symptoms.6 The actual mechanism behind developing SJS/TEN-induced severe skin reactions is still not clear. To date, scientists believe that skin keratinocytes undergo frequent apoptosis through multiple phases in SJS/TEN. Phase I is involved with the immunogenic role of xenobiotics. Phase II is the step of early apoptosis that causes production of potential electrophilic metabolites, disrupts the electron transfer chain inside the mitochondria, and generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that works as a second messenger enhancing the gene transcription process of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and CD95 proapoptotic systems.7 In phase III, the cytokine TNF-α works as an autocrine factor on the surrounding healthy cells, and epidermal destruction takes place. In phase IV, through a slow nonapoptotic mechanism, disrupted cells with ruptured mitochondria are necrotized leading to formation of mucocutaneous blisters.5 In addition, a drug can activate Fas ligands (FasL) distributed in a variety of cells including keratinocytes and binding of FasL to Fas receptors on cells activate the release of caspases inducing cell apoptosis, vigorously.8 FasL-mediated release of perforin and granzyme B through activating the natural killer cells and cytotoxic T-cells (CD8) further potentiates the cell apoptosis process.9

There are numerous SJS/TEN treatment and management guidelines worldwide. Hence, withdrawal of the responsible drug, early hospitalization, and a bundle of supportive care preferably under ICU management are highly required to minimize SJS/TEN-associated complications or rate of mortality.1–3,5 Here, intravenous NAC with (case 1) or without (case 2 and 3) IVIG, a similar therapeutic outcome (blisters formation stopped within 48 h and blisters were healed completely within 1 week of NAC therapy) was observed in all three cases. In 1997, intravenous NAC was used in a patient with anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome and treated successfully.10 NAC (300 mg/kg of body weight/day) intravenously was used in two middle-aged patients with TEN and the eruption was stabilized with complete reepithelialization within 7 days without having any IVIG therapy.11 Two reports demonstrated that TEN caused by different drugs were successfully treated with intravenous NAC in addition with IVIG in adult patients.5,12 A lamotrigine-induced TEN (non-responsive to IVIG) event was successfully treated in a 10-year-old epileptic girl, where intravenous NAC was concomitantly added to its management.13 All the patients of this study were self-paying patients at Square Hospital (a tertiary-level fully private hospital), and they agreed to the use of NAC for its very low price in comparison to IVIG.

NAC has the ability to boost the level of GSH. The nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), a nuclear transcription factor induced by TNF-α and interleukin (IL)-6, potentiates the inflammatory mediators in skin lesions. NAC inhibits the release of kappa-B and potentiates the buffering ability of GSH, and thus suppresses the progression of inflammation in skin lesions.5 The study found that in the early phase of an SADR event, the severity of skin lesions is significantly associated with a high level of cytokines and chemokine receptors, including a high level of TNF-α and interferon (IFN)-γ potentiating epidermal necrosis; interleukin (IL)-2, IL-5, IL-13 provoking mucocutaneous immunoinflammation processes; receptor 3 for C-C chemokines (CCR3); and receptor 4 for C-x-C chemokines (CXCR4) inducing more inflammatory cells in the lesional skin.14 The pivotal role of NAC in these cellular immunoinflammatory processes is still not clear, but in our cases, proper care and intravenous NAC-associated medication management resulted in a satisfactory clinical outcome in the treatment of SJS/TEN-induced mucocutaneous blisters. Dose-dependent common side effects of intravenous NAC are bronchospasm, angioedema, and hypotension.15 Patients’ inadequate clinical data and limited number of cases are the major limitation of this study. Some randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are highly required at this moment to justify the actual role of NAC in the management of drug-induced severe skin lesions.

In conclusion, early management of mucocutaneous blisters induced by SADRs, including SJS/TEN with appropriate drugs is highly required to reduce event-associated complications and mortality rate. However, unavailability of such standard drugs for this purpose is a limitation worldwide. The use of intravenous NAC alone or with IVIG in the early stage of developing fluid-filled blisters associated with SADRs may be effective to reduce the severity and related complications of these skin lesions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the authority of Square Hospitals Ltd. for giving permission and to all the patients of these case reports for giving their consent to publish this report.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval to report this case series was obtained from Square Hospital Ethical Committee (Approval No./ID: CR-090219SH).

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients/legally authorized representative of patients for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Md Jahidul Hasan  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7038-6437

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7038-6437

References

- 1. Gautron S, Wentzell J, Kanji S, et al. Characterization of serious adverse drug reactions in hospital to determine potential implications of mandatory reporting. Can J Hosp Pharm 2018; 71(5): 316–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nguyen KD, Tran TN, Nguyen MT, et al. Drug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in vietnamese spontaneous adverse drug reaction database: a subgroup approach to disproportionality analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther 2019; 44(1): 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nandha R, Gupta A, Hashmi A. Cutaneous adverse drug reactions in a tertiary care teaching hospital: a north Indian perspective. Int J Appl Basic Med Res 2011; 1(1): 50–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mokhtari V, Afsharian P, Shahhoseini M, et al. A review on various uses of N-acetyl cysteine. Cell J 2017; 19(1): 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saavedra C, Cárdenas P, Castellanos H, et al. Cephazolin-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis treated with intravenous immunoglobulin and N-acetylcysteine. Case Reports Immunol 2012; 2012: 931528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lerch M, Mainetti C, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, et al. Current perspectives on Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2018; 54(1): 147–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lam A, Randhawa I, Klaustermeyer W. Cephalosporin induced toxic epidermal necrolysis and subsequent penicillin drug exanthem. Allergol Int 2008; 57(3): 281–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nagata S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell 1997; 88: 355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iwai K, Miyawaki T, Takizawa T, et al. Differential expression of bcl-2 and susceptibility to anti-Fas-mediated cell death in peripheral blood lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils. Blood 1994; 84: 1201–1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Redondo P, de Felipe I, de la Peña A, et al. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: treatment with N-acetylcysteine. Br J Dermatol 1997; 136(4): 645–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vélez A, Moreno JC. Toxic epidermal necrolysis treated with N-acetylcysteine. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46: 469–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Claes P, Wintzen M, Allard S, et al. Nevirapine-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis and toxic hepatitis treated successfully with a combination of intravenous immunoglobulins and N-acetylcysteine. Eur J Intern Med 2004; 15(4): 255–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yavuz H, Emiroglu M. Toxic epidermal necrolysis treated with N-acetylcysteine. Pediatr Int 2014; 56: e52–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caproni M, Torchia D, Schincaglia E, et al. Expression of cytokines and chemokine receptors in the cutaneous lesions of erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol 2006; 155(4): 722–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mahmoudi GA, Astaraki P, Mohtashami AZ, et al. N-acetylcysteine overdose after acetaminophen poisoning. Int Med Case Rep J 2015; 8: 65–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]