Abstract

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, many behavior analysts have temporarily transitioned to providing services using a telehealth model. This has required them to rapidly shift their treatment modality. The purpose of this article is to provide a review of some available technologies to support telehealth that will allow behavior analysts to conduct direct observation from a remote location. We reviewed 3 technologies that can be used for telehealth: (a) web cameras, (b) Swivl, and (c) telepresence robots. Features of each of these technologies are compared, and the benefits and drawbacks of each are reviewed. Sample task analyses for using each technology are also provided. Finally, tips for using telehealth with families are provided.

Keywords: technology, telehealth, telepresence robot, Swivl

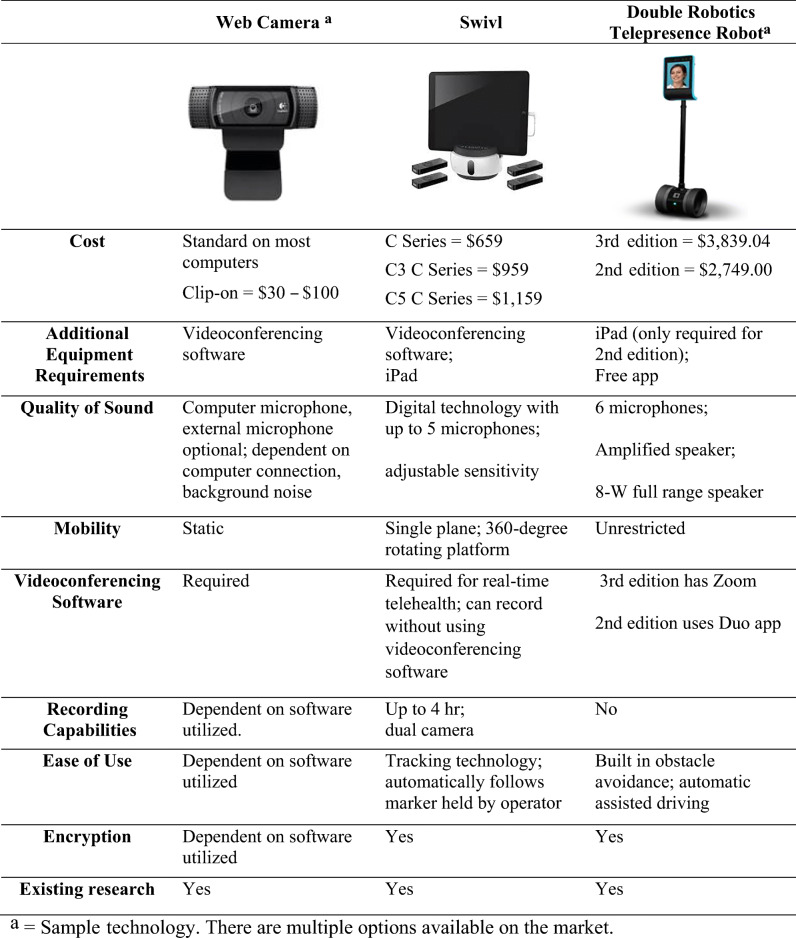

Traditionally, center-based applied behavior analysis (ABA) therapy is delivered in a face-to-face format across several sessions; however, given the recent COVID-19 pandemic, many behavior analysts practicing in ABA centers have temporarily been authorized to provide services using a telehealth model. This rapid change in service delivery has posed unique challenges for behavior analysts and families with loved ones who were receiving ABA services in centers or schools. One of the most pressing concerns is that behavior analysts commonly rely on direct observation of behavior to make data-based decisions regarding client treatment plans. The shift to a telehealth model in light of the COVID-19 pandemic requires behavior analysts to quickly adapt the manner in which many have been providing services. Although many behavior analysts may be familiar with various technologies, they may struggle to identify the benefits and limitations of each technology in terms of providing telehealth. Selecting an appropriate technology that allows behavior analysts to stay true to the science of behavior analysis is prudent. The purpose of this article is to provide a review of some available technologies to support telehealth that will allow behavior analysts to conduct direct observation from a remote location. The three technologies reviewed are (a) web cameras, (b) the Swivl, and (c) telepresence robots. Features of these technologies will be described and compared, including the benefits and drawbacks of each (see Table 1). Sample task analyses for using each technology are also provided.

Table 1.

Comparison of Telehealth Technologies

aSample technology. There are multiple options available on the market.

Telehealth Research

Telehealth is a model of service delivery that utilizes telecommunications and information technology to provide access to health care, assessment, diagnosis, intervention, consultation, supervision, and education (Nickelson, 1998). Although more commonly associated with psychiatric and psychological services (Vandenbos & Williams, 2000), telehealth is a growing area of research in the fields of education and ABA. Ferguson et al. (2018) conducted a systematic review of telehealth interventions for 28 individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Intervention characteristics employed across telehealth studies were functional analyses, naturalistic teaching, behavior supports, preference assessments, and comprehensive training packages about behavior-analytic principles (Ferguson et al., 2018). Given the positive outcomes across participants and studies, results from the review suggested that telehealth can be an acceptable platform for behavior-analytic interventions and assessments. Information regarding the type of technology used to conduct the telehealth interventions, however, was limited. Only a small number of studies provided extensive information describing the technology. Of those studies, the most common technology used was videoconferencing software with webcams to provide didactic training and video coaching (Ferguson et al., 2018).

In one study, Wacker et al. (2013) conducted functional analyses via telehealth with 20 children between the ages of 19 and 80 months who displayed problem behavior. Using telehealth software, the behavioral consultant sat at a computer with a webcam that received video and audio from a regional pediatric clinic located miles away. The behavioral consultant was able to remotely move the camera up, down, and side to side so that the parent and child remained visible at all times. The behavioral consultant trained parents via teleconferencing about the study’s purpose and procedures and also interviewed the parent about his or her child’s problem behaviors. Last, the behavioral consultant coached and supported the parent in conducting a functional analysis to identify the maintaining variable of the problem behavior. For 18 out of 20 participants, the behavioral consultant identified environmental variables as the maintaining variable for problem behaviors with interrater agreement of over 90%. Results from the study suggested that behavioral consultants can collaborate with parents and conduct functional analyses effectively and efficiently via telehealth.

Telehealth Technologies

Even though telehealth has been the subject of research for decades, with some early work involving the use of telephones to support parent trainings (e.g., Patterson, 1974) or “bug-in-ear” technology to provide real-time coaching (e.g., Bowles & Nelson, 1976), exponential advancements in technology have provided a range of available technologies to support telehealth, from low tech to high tech. Despite research in support of telehealth, many behavior analysts may express some hesitation using telehealth technologies due to an unfamiliarity with the available technologies. In the following sections, we outline three technologies (i.e., webcam, Swivl, and telepresence robots) that behavior analysts can use when implementing ABA services via a telehealth model that allow for direct observation, as well as uses for videoconferencing software. We conclude with a brief discussion of ethical considerations, as well as general tips for emplying teleheath technologies.

Web Cameras

Web cameras are commonplace today and are a standard feature on many laptop and desktop monitors. A web camera uses videoconferencing software to transmit video in real time. If an older laptop or desktop screen is still used, cost-effective clip-on web cameras can be installed with relative ease (see Table 1). Clip-on web cameras can plug into a computer, but others are wireless and use Wi-Fi. Headphones and an external microphone are sometimes used to enhance sound quality. There are a number of available features for web cameras, including built-in microphones, lights to notify the user when the web camera is on, tilting and panning, and autofocus. When selecting an external web camera, these features should be considered. External web cameras are inexpensive and accessible to most users. In fact, the most basic web cameras can be purchased for approximately $20.

Web cameras are the most easily accessible of the technologies reviewed. They are built into most devices (e.g., laptops, cell phones, tablets) and are inexpensive to purchase independently as a clip-on device. Web cameras have very minimal setup requirements. Initial setup generally comprises downloading the desired application and allowing it to access the computer’s microphone and camera. After this, accessing the web camera’s basic functions becomes automated upon use. A benefit of purchasing an external web camera is the ability to position the camera to obtain a better view of the environment, as opposed to a fixed internal web camera that is positioned to capture the computer user’s face.

A notable limitation of web cameras is behavior analysts’ inability to fully immerse in their clients’ environment. The web camera provides a limited view of the environment. The quality of the picture and sound is impacted by one’s Internet connection. Furthermore, an external microphone may need to be purchased. Additionally, external cameras can be confusing to clip on and navigate during early use.

Tips for use

A sample task analysis for using a Logitech™ web camera is provided (Appendix A). When selecting an external web camera, behavior analysts should suggest a camera that has an indicator light that lets clients know when they are being recorded. The consultee (e.g., parent, client) should be provided with training for turning the camera on and off and operating the software. At the end of each session, ensure that the camera is turned off to protect privacy. Clients may choose to place a small piece of painter’s tape over the camera lens. If using a videoconferencing application that provides clinicians one universal meeting link, be sure to “lock” the meeting when all parties are present.

Research support

A number of studies have been conducted in which web cameras were used. In one study conducted by Simacek, Dimian, and McComas (2017), the researchers utilized web cameras for training and coaching caretakers on the implementation of a functional communication intervention for three children with developmental disabilities. Functional assessments were also conducted virtually prior to the intervention, and all three children acquired the communication responses targeted in the study. Results indicated caretakers were able to implement the intervention successfully across various settings. Furthermore, caretakers rated the treatment as acceptable.

Swivl

A Swivl (https://www.swivl.com/) is a video consultation device with the ability to rotate 360 degrees in order to follow and record the presenter with a connected tablet (e.g., iPad). The presenter wears a transmitter on a lanyard that emits a signal to the device to notify it of the wearer’s movement (Swivl, n.d.). The device also serves as a stand for the tablet when used as the recording device. A microphone is built into the transmitter to record the presenter’s speech, and additional transmitters can be synced to the device to record more than one individual. Real-time video can be streamed with other users by using the Swivl in tandem with a videoconference application (Swivl, n.d.). After recording, videos can be accessed through the Swivl app on the tablet, as well as through the Swivl website on a computer. Users are then able to review, annotate, and ask questions about the recorded sessions.

There are several benefits for behavior analysts choosing to use a Swivl for telehealth. The Swivl is a good option for telehealth when the behavior analyst wants to directly observe the client in the environment. One of the most notable benefits is the ability of the Swivl to move 360 degrees. Because of the transmitter lanyard, the camera does not need to be manually readjusted. Furthermore, the transmitter lanyard includes a microphone, which greatly improves the audio quality. There are also several video options available. ABA therapy sessions can be conducted using the live-feed option, or sessions can be video recorded and viewed at a later time by the behavior analyst. The ability to annotate sessions is unique to the Swivl and may be an option for tech-savvy parents who would benefit from feedback.

Compared to webcams, the Swivl may be cost prohibitive. The device is more expensive than a webcam and requires the use of an external tablet, which may also need to be purchased. Despite the cost, the Swivl may be a good long-term purchase for ABA providers, as it has utility for supervision, home-based therapy, and clinic-based interventions. Another potential limitation of the Swivl is the use of the transmitter lanyard. Although parents would likely be comfortable wearing the lanyard, an individual with autism spectrum disorder may refuse. Finally, signals between the transmitter and the device can be easily obstructed when the individual with the transmitter lanyard moves out of range or due to Internet connectivity issues. These issues may impact sound and video quality.

Tips for use

A task analysis for setting up the Swivl is provided (Appendix B). The Swivl should be set up in a high-traffic area where a 360-degree view is possible. It is best to set the Swivl up on a table that is in the middle of the room. One important consideration is to determine the best person to wear the lanyard. For example, if the behavior analyst would like to observe the client’s behaviors, the client should wear the lanyard. If observing the client is not as important for the session, the parent can wear the lanyard. When using the Swivl, sound quality may be jeopardized in noisy settings. Behavior analysts should be aware that the Swivl (n.d.) provides users with setup suggestions in order to maintain the video and audio quality of recordings, and the microphone has features to help the user minimize background noise in recordings.

Research support

The Swivl has been used in a number of studies (e.g., Johnson, Zheng, Crawford, & Moylan, 2019; McCoy, Lynam, & Kelly, 2018). Most of the available studies have evaluated the use of a Swivl in school-based research. In a pilot study conducted by Franklin et al. (2018), researchers recruited teachers from public schools to set up and use a Swivl in their classrooms and report strengths and weaknesses found when using the technology. Participants noted its ease of use, both in setting up the device and accessing recordings; however, Internet connectivity was a reported issue.

Telepresence Robots

A telepresence robot is a videoconferencing screen (e.g., tablet) that is mounted on a wheeled base that can be controlled from a remote location, allowing for a more physical virtual presence than the two other technologies described. There are a variety of vendors that sell telepresence robots. Of the three technologies, telepresence robots can have the highest cost. The most basic telepresence robots are similar in cost to the Swivl; however, some sell for up to $30,000. The available features vary greatly depending on the cost; however, for the purposes of behavior-analytic telehealth, the more basic models are likely adequate. Double Robotics (n.d.) offers some of the more affordable telepresence robots.

The primary benefit of the telepresence robot is the ability of the behavior analyst to have a more physical virtual presence. The behavior analyst can control the robot from a remote location and can navigate through the environment. This physical presence of the robot may be helpful for developing and maintaining rapport with parents. Furthermore, the ability to navigate through the environment may be especially useful in high-stakes or high-risk cases. Although the telepresence robot is the most expensive option, it may be a good long-term investment for ABA centers, especially those centers that plan to continue telehealth or those that provide supervision to therapists providing home-based and school-based therapy. The supervising behavior analyst can provide feedback and training without leaving the ABA clinic. The telepresence robot requires the use of a secure app where data are encrypted. Third-party videoconferencing software is not required. Finally, families clearly determine when the behavior analyst can be virtually present, as the client is required to log in to the app in order for the behavior analyst to navigate the robot in the environment.

There are several potential limitations of using telepresence robots. Most notably is their cost. Given the cost, this may only be an option for practitioners who already have telepresence robots. The telepresence robot is more complicated to set up initially; however, once it is set up, parents only need to log in to the tablet. The telepresence robot typically requires a strong high-speed Internet connection, which may not be available in certain communities (e.g., rural). The telepresence robot must be plugged into an electrical outlet to maintain a battery charge when not in use. Finally, the telepresence robot is more obtrusive than the other technologies, and clients may be more reactive to the technology.

Tips for use

Parents should be provided with a task analysis to set up the telepresence robot. A sample task analysis for setting up the Double Robotics Duo 2 telepresence robot is provided (Appendix C). The use of a remote control (e.g., PS4™ controller), as opposed to the keys on the computer, may help with navigation. The behavior analyst should “test-drive” the telepresence robot before using the robot in homes. Although the robot is not necessarily difficult to navigate, it does require some practice. Consider the goals of the therapy session, and reserve the use of a telepresence robot for high-needs cases.

Research support

Fischer, Bloomfield, Clark, McClelland, and Erchul (2019) conducted a study to evaluate how three-step prompting impacted student compliance in special education classrooms. Two telepresence robots were used and operated remotely by consultants and research assistants to observe the environment. The researchers found that problem-solving teleconsultation using a telepresence robot was an effective means of increasing compliance and had high levels of acceptability for all participants and moderate levels of treatment integrity. Teacher participants reported that the telepresence robot was an acceptable manner by which consultation services were provided.

Videoconferencing Software

Many of the technologies that are used for telehealth require the use of third-party videoconferencing software. There is a range of available videoconferencing products, and each has different features (e.g., encryption, ability to record). Videoconferencing software should be selected based on the user’s needs. Fischer, Schultz, Collier-Meek, Zoder-Martell, and Erchul (2018) reviewed videoconferencing technology that has been cited in the school consultation literature. Features of the technology were reviewed, including the cost, computer compatibility, number of users, on-screen document sharing, integrated cloud storage, instant messaging, and compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA, 1974; HIPAA, 1996). As there are with any online platform, there are ethical considerations related to confidentiality. To the extent possible, behavior analysts should select platforms that are compliant with HIPAA and FERPA. For a discussion of the ethical considerations regarding using teleconsultation, readers should review Fischer, Collins, Dart, and Radley (2019).

Ethical Considerations

Traditionally, behavior analysts have not delivered services to clients using a telehealth model, as managed health care providers require direct contact with clients. Furthermore, much center-based ABA occurs in a one-on-one or small-group format. Therefore, telehealth is a new treatment modality for many behavior analysts. Regardless of the technology selected, there are a number of ethical considerations for implementing ABA therapy via a telehealth model that are outside of the scope of this article. Behavior analysts are encouraged to read Cox, Plavnick, and Brodhead (2020) for a discussion of ethical considerations related to providing ABA services given the COVID-19 pandemic. Behavior analysts are further encouraged to seek out training opportunities for using a telehealth model. A number of providers are currently offering online training for using a telehealth model.

General Telehealth Tips

In addition to selecting a technology to support telehealth, there are a number of additional considerations that behavior analysts may find helpful. The following strategies are suggested when using telehealth for the first time, regardless of the technology selected:

Obtain informed consent for using telehealth.

Consider privacy and confidentiality. Advise parents of the limitations to privacy and confidentiality when using the Internet.

Assess the family’s comfort and familiarity with the technology.

Introduce the family to the technology via a phone conversation.

Provide video recorded and written instructions to set up the technology.

Keep the technology set up in the home to manage reactivity.

Check in with the parent/client to make sure it is a good time to observe prior to turning on the technology.

Summary

Given the recent COVID-19 pandemic, many behavior analysts are temporarily transitioning from school- and center-based ABA therapy services to using a telehealth model. Although telehealth is widely used in other fields (e.g., medicine), it is less practiced in the field of behavior analysis. As a result, behavior analysts have needed to rapidly transition to a model of service delivery in which many have little experience. As behavior analysts transition to using telehealth to support clients during the pandemic, there are a number of considerations, including the selection of technology. Behavior analysts may find the use of webcams, Swivls, or telepresence robots useful in facilitating telehealth.

Appendix A

Sample Task Analysis for Using Webcam: Logitech Web Camera

Setup

Open the Logitech box.

Remove the Logitech device.

Pull down the flexibility clip/base of the Logitech device and secure it onto the top of your computer where the built-in camera generally is.

- Open Skype for Business.

- Log in with your Outlook information.

Plug in the Logitech device to the computer’s USB port.

- A pop-up should appear asking if you would like to use the Logitech device as your preference. Select yes.

- If the pop-up does not appear:

-

i.Click “Skype for Business” in the top-left corner of the computer screen;

-

ii.Select “preferences”; and

-

iii.Ensure the “microphone” and “camera” are set to Logitech Webcam C930e.

-

i.

Flip open the privacy cover.

- Position the Logitech camera to capture your face and/or the setting.

- To do this:

-

i.Click “Skype for Business” in the top-left corner of the computer screen;

-

ii.Select “preferences”; and

-

iii.Select “audio/video.”

-

i.

Click on “contacts” to select who to call.

Click on the video camera image (“Start a video call”).

Teardown

Click the red phone symbol (“hang up”).

Click “Skype for Business” at the top-left corner of your computer screen.

Click “Sign Out.”

Click “Skype for Business” at the top-left corner of the computer screen.

Click “Quit Skype for Business.”

Close the privacy cover on the Logitech device.

Unplug the Logitech device from the computer.

Take the Logitech device from where it is resting on the computer.

Close the flexibility clip/base of the Logitech device.

Return the Logitech device to its box.

Close the Logitech box.

Appendix B

Sample Task Analysis for Using Swivl

Setup

Unzip the Swivl container.

Remove the white cord and Swivl from the case and place them on a flat surface.

Insert the USB on the white cord into the USB port on the back side of the Swivl.

Connect the opposite end of the white cord to the charging port on the iPad.

Insert the iPad into the Swivl.

Press and hold the power button on the Swivl.

Open the Swivl app.

Remove the small remote on top of the Swivl.

Hold the power button on the remote for 3–4 s. The LEDs on the remote will light up, and the bottom LED will flash red as it searches for the base. Both lights on the remote should turn green, indicating that it paired with this base. The Primary Marker is the one that the base will respond to and track.

Swivl follows movement of the remote via sensors on the front of the remote and the front of the Swivl. Practice moving the Swivl with the remote.

Tap the button on the middle-left side of the screen. The word “zoom” should pop up. Click the word zoom. This will take you to a new app.

Select “new meeting.”

Select “start meeting.”

Click “Participants” in the upper-right corner.

Click “Invite”; this is how you would conduct a live consultation.

Teardown

Press and hold the power button on the Swivl to turn it off.

Place the small remote back on the Swivl.

Disconnect the USB from the iPad and Swivl, and place cord back into the Swivl container.

Set the iPad aside.

Put the Swivl back into the case and zip it shut.

Appendix C

Sample Task Analysis for Using a Telepresence Robot: Double Robotics Duo Telepresence Robot

Setup

Set the Double box down on a flat surface and undo all six tabs.

Remove the iPad case located in the right corner of the box and set it aside. The iPad spacer is inside the case.

Remove the white cardboard box and set it aside. This will not be used during setup.

Remove the audio kit and camera kit and set them aside.

Remove the foam “puzzle piece” from on the middle-right end of the box to gain access to the telepresence robot

Take the telepresence robot out of the box and place it standing up on a flat surface. The side with “Double” on it is the front of the robot.

Open the audio kit and take it out of its box.

Slide the back of the audio kit off.

Position the audio kit on top of the pole and place the speaker at the front with the cords facing up. Ensure the speaker is a few inches from the top of the pole.

Slide the back portion of the audio kit upward along the pole so that it fits together with the front and secures the speaker.

Place one cord of the audio kit into the top of the pole.

Pick up the iPad case. Inside the case is a spacer. Slide the spacer out of the iPad case.

Insert the iPad into the spacer. Line up the volume button with the gap in the spacer.

Set aside the spacer and remove the camera kit from its box.

Locate the USB port inside the iPad case. Plug the USB cord on the camera kit into the USB port inside the iPad case. You will have to thread the cord through the top of the case in order to properly do this.

Making sure the cord is neatly tucked; you may now slide in your iPad upside down into the iPad case.

Plug the camera kit into the charging port of the iPad.

Insert the iPad case into the robot.

Remove the bolt and wrench located in the audio kit.

Take the long bolt and insert it behind the iPad head through the opening at the top.

Tighten it with the hex wrench until it is firmly in place.

Plug the hanging cord from the audio kit into the headphone jack on the iPad.

Pairing Bluetooth

Turn on the telepresence robot by holding down the power button on the bottom back side of the robot (hold down for about 3 s).

The front LED should start flashing blue, indicating that it is ready to pair with the iPad.

Go to your iPad’s Settings > Bluetooth and locate your Double under the Devices list. Tap to pair. After a few seconds, your Double should pair with the iPad.

If a pop-up appears on the iPad asking to pair/communicate with the Double, click “allow.”

Open the Double app on the iPad.

Instructions for the Behavior Analyst

Using a device connected to Wi-Fi, open Chrome.

Go to www.drive.doublerobotics.com.

Log in.

Click on the active robot.

Use the arrow keys to navigate the robot.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This project was not funded.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bowles PE, Nelson RO. Training teachers as mediators: Efficacy of a workshop versus the bug-in-the-ear technique. Journal of School Psychology. 1976;14(1):15–26. doi: 10.1016/0022-4405(76)90058-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D. J., Plavnick, J., & Brodhead, M. T. (2020, March 31). A proposed process for risk mitigation during the COVID-19 pandemic. 10.31234/osf.io/buetn [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Double Robotics. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.doublerobotics.com/

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974, 20 U.S.C. § 1232g (1974).

- Ferguson, J., Craig, E. A., & Dounavi, K. (2018). Telehealth as a model for providing behaviour analytic interventions to individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 582–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fischer A, Bloomfield B, Clark R, McClelland A, Erchul W. Increasing student compliance with teacher instructions using telepresence robot problem-solving teleconsultation. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology. 2019;7:158–172. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2018.1470948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Collins T, Dart E, Radley K. Technology applications in school psychology consultation, supervision, and training. New York, NY: Routledge; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Schultz B, Collier-Meek M, Zoder-Martell K, Erchul W. A critical review of videoconferencing software to support school consultation. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology. 2018;6(1):12–22. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2016.1240129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin R, Mitchell J, Walters K, Livingston B, Lineberger M, Putman C, Karges-Bone L. Using Swivl robotic technology in teacher education preparation: A pilot study. TechTrends. 2018;62:184–189. doi: 10.1007/s11528-017-0246-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), Pub. L. No. 104-191, § 264, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996). [PubMed]

- Johnson ES, Zheng Y, Crawford AR, Moylan LA. Developing an explicit instruction special education teacher observation rubric. Journal of Special Education. 2019;53(1):28–40. doi: 10.1177/0022466918796224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy, S., Lynam, A., & Kelly, M. (2018). A case for using Swivl for digital observation in an online or blended learning environment. International Journal on Innovations in Online Education, 2(2). 10.1615/IntJInnovOnlineEdu.2018028647.

- Nickelson DW. Telehealth and the evolving health care system: Strategic opportunities for professional psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1998;29(6):527–535. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.29.6.527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Interventions for boys with conduct problems: Multiple settings, treatments, and criteria. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42(4):471–481. doi: 10.1037/h0036731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simacek, J., Dimian, A., & McComas, J. (2017). Communication intervention for young children with severe neurodevelopmental disabilities via telehealth. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(3), 744–767. 10.1007/s10803-016-3006-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Swivl. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.Swivl.com/

- VandenBos, G. R., & Williams, S. (2000). The Internet versus the telephone: What is telehealth anyway?. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31(5), 490–492.

- Wacker, D. P., Lee, J. F., Dalmau, Y. C. P., Kopelman, T. G., Lindgren, S. D., Kuhle, J., et al. (2013). Conducting functional analyses of problem behavior via telehealth. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46(1), 31–46. 10.1007/s10882-012-9314-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]