Abstract

The complete folate biosynthesis pathway exists in the genome of a rickettsial endosymbiont of Ixodes pacificus, Rickettsia monacensis strain Humboldt (formerly known as Rickettsia species phylotype G021). Recently, our lab demonstrated that the folA gene of strain Humboldt, the final gene in the folate biosynthesis pathway, encodes a functional dihydrofolate reductase enzyme. In this study, we report R. monacensis strain Humboldt has a functional GTP cyclohydrolase I (GCH1), an enzyme required for the hydrolysis of GTP to form 7,8-dihydroneopterin triphosphate in the folate biosynthesis pathway. The GCH1 gene of R. monacensis, folE, share homology with the folE gene of R. monacensis strain IrR/Munich, with a nucleotide sequence identity of 99%. Amino acid alignment and comparative protein structure modeling have shown that the FolE protein of R. monacensis has a conserved core subunit of GCH1 from the T-fold structural superfamily. All amino acid residues, including conserved GTP binding sites and zinc binding sites, are preserved in the FolE protein of R. monacensis. A recombinant GST-FolE protein from R. monacensis was overexpressed in E. coli, purified by affinity chromatography, and assayed for enzyme activity in vitro. The in vitro enzymatic assay described in this study accorded the recombinant GCH1 enzyme of R. monacensis with a specific activity of 0.81 U/mg. Our data suggest folate genes of R. monacensis strain Humboldt have the potential to produce biochemically active enzymes for de novo folate synthesis, addressing the physioecological underpinnings behind tick-Rickettsia symbioses.

Keywords: Rickettsia monacensis strain Humboldt, Ixodes pacificus, folE gene, GTP cyclohydrolase I

INTRODUCTION

Folate, also known as Vitamin B9, plays a central role in cell division in all living organisms. Folates function in single-carbon transfer reactions in the biosynthesis of thymidylate and purines as well as in the biochemical conversion of homocysteine to methionine (Tjong and Mohiuddin, 2019). The production of folates by endosymbiotic bacteria is well reported in studies of arthropods, specifically where host diets are low in micronutrients (Baumann, 2005; Husnik, 2018). It has also been demonstrated that extracellular gut symbionts can play a role in providing folates and other micronutrients to their respective arthropod hosts (Engel and Moran, 2013; Nikoh et al., 2011).

Tick-borne diseases continue to be a growing concern in the United States. In the Western United States and western Canada, the causative agents of diseases including Lyme borreliosis and anaplasmosis are carried by Ixodes pacificus, the western black-legged tick (Lane et al., 1994; Richter et al., 1996). The ectoparasitic I. pacificus is restricted to a diet of mammalian blood, which is often lacking in vital micronutrients including B vitamins (Duron et al., 2018; Hunter et al., 2015). Despite their limited access to dietary micronutrients and incapability of endogenous biosynthesis of key micronutrients including water-soluble compound folates, as revealed by tick genome sequencing (NCBI Bioproject Accession number PRJNA34667), I. pacificus can survive for extended periods of time without blood feeding (Padgett and Lane, 2001). For ticks, blood meals are required for growth and molting in nymphs and larvae as well as gamete production in adults. The acquisition of a blood meal is accompanied by morphological changes of tick tissues associated with rapid engorgement of adult females (Sonenshine, 1993; Tajeri et al., 2016).

The specific influences that tick endosymbionts have on the internal processes and behavioral activities of their host remain largely unexplored. Detailed exploration of these microorganisms could help facilitate the unravelling of the interconnected physiologies between ticks and their endosymbionts, and will shed light on factors affecting tick fitness. To this end, the characterization of R. monacensis strain Humboldt (formerly known as Rickettsia species phylotype G021) (Alowaysi et al., 2019), an endosymbiotic Rickettsia species living within the tissues of I. pacificus has been initiated (Bagheri et al., 2017; Phan et al., 2011). The sequencing of DNA extracted from ticks revealed dominating levels of rickettsiae (Benson et al., 2004; Budachetri et al., 2016). R. monacensis strain Humboldt is a member of the spotted fever group rickettsiae (Phan et al., 2011) that is present in almost all I. pacificus ticks (Cheng et al., 2013), is inherited matrilineally, and is sustained throughout the tick life cycle (Cheng et al., 2013). Interestingly, the burden of R. monacensis is significantly increased upon blood meal acquisition across the life cycle of I. pacificus (Cheng et al., 2013).

We have reported genetic and in vitro biochemical data that allow us to suppose a role for R. monacensis strain Humboldt in the metabolic biosynthesis of folates in I. pacificus. Specifically, identification of the complete folate biosynthesis pathway in the genome of R. monacensis, and the subsequent verification in vitro of dihydrofolate reductase activity from the recombinant rickettsial FolA enzyme, would suggest the pathway is functional (Bodnar et al., 2018; Hunter et al., 2015). Furthermore, the recent genome sequencing project of R. monacensis strain Humboldt confirmed that the bacterium has the genetic capacity for de novo folate biosynthesis (GenBank accession numbers SRX476327, SRX476328, SRX476329) (Alowaysi et al., 2019). These recent reports, in the context of the limited metabolic capabilities, low-micronutrient diet, and life cycle of I. pacificus, provide indications of folate production by R. monacensis.

For this study, rickettsial FolE, the first enzyme in the folate biosynthesis pathway, was used to expand upon the characterization of the de novo folate biosynthesis capacity of R. monacensis. The cloning and annotation of the folE gene, followed by the isolation and in vitro assaying of the FolE protein’s function are reported here.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tick collection and DNA extraction

In March 2012, questing ticks from Humboldt County, California (GPS coordinate: N 40 55.200 W 123 50.400) were collected by blanket dragging and morphologically verified to be I. pacificus by light microscopy (Furman and Loomis, 1984). A single female adult I. pacificus was homogenized using a RNase-Free Disposable Pellet pestle (Fisher Scientific, Tampa, FL) in liquid nitrogen and DNA was extracted using alkaline hydrolysis, as described previously (Bodnar et al., 2018; Guy and Stanek, 1991). DNA concentration of the extracted tick DNA was measured by a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and stored at −20°C.

PCR amplification of the folE gene of R. monacensis strain Humboldt

The following primers were designed to amplify the whole open reading frame of the folE gene of R. monacensis strain Humboldt: forward primer 5’-GATAGACCTATGTCAAATGAGTAAACCAACTAGAGAAGAAGCT–3′ and reverse primer 5’-GTTAGACCCGTGTCAATTACCTTTTCGAGGTAAGGTTTAAAAACT-3’ (Elim Biopharmaceuticals, Hayward, CA), with the PshAI restriction site underlined. 60 ng of DNA extracted from I. pacificus was mixed with 2X EconoTaq Plus Green Master Mix (0.1 units/μl EconoTaq DNA polymerase, 50 mM Tris-HCL, pH 9.0, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 200 μM dNTPs, 5 mM MgCl2) (Lucigen, Middleton, WI), and forward and reverse primers (1 μM each). The PCR, conducted on a MJ research PTC-200 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), was exposed to a single cycle of 94°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 52.8°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 45 s. The final extension was at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR product was electrophoresed on 1% agarose in 1X TAE buffer (40 mM Tris, pH 8.6, 20 mM acetate, 1 mM EDTA) and visualized under UV light after ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) staining. A negative PCR control was prepared with water instead of tick DNA.

Construction of an expression plasmid for the folE gene of R. monacensis strain Humboldt and DNA sequencing

To overexpress FolE protein of R. monacensis in E. coli, the expression vector used was pET-41a(+) (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), which facilitates the expression of the protein as a fusion product tagged with N-terminal GST. The cloning procedure has been described previously (Bodnar et al., 2018). Briefly, the folE PCR fragment of R. monacensis and pET-41a(+) plasmid was digested with PshAI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Ligation of the gel-purified rickettsial folE PCR amplicon in the plasmid was completed with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), generating pET41a(+)−folE clone. After ligation, the reaction mix was transformed into competent E. coli strain NovaBlue (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Kanamycin resistant colonies were then cultured in LB broth plus 100 mg/L kanamycin. The Wizard Plus SV Minipreps DNA Purification System (Promega, Madison, WI) was used for plasmid purification. The insert of the pET41a(+)-folE clone was sequenced at Elim Biopharmaceuticals (Elim Biopharmaceuticals, Hayward, CA) with the following vector specific primers: forward primer 5’- AAGAAACCGCTGCTGCTAAA-3′ and reverse primer 5’- AGCTCCGTCGACAAGCTT-3’ (Elim Biopharmaceuticals, Hayward, CA).

Homology finding and structural analysis

The nucleotide sequence of the folE gene from this study was compared with the nucleotide sequence of the previously deposited folE gene of Rickettsia species phylotype G021 (GenBank accession number KT225570, submitted as Rickettsia endosymbiont of I. pacificus) (Hunter et al., 2015) and other homologous sequences (Suppl. Table 1) by BLAST. Since the identity between R. monacensis strain Humboldt and phylotype G021 is 100%, but only KT225570 has its 5’ UTR sequence, a putative promoter of the folE gene was identified in the nucleotide sequence of KT225570 using Softberry’s BPROM on www.softberry.com. The folE open reading frame (ORF) was identified by use of the ORF Finder at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/. In addition, structural and functional domains of the FolE protein of R. monacensis were identified via NCBI CD-Search at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi.

Homology modeling of the FolE protein of R. monacensis was constructed on SWISS-MODEL homology modeling server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/). The template for the homology modeling was Thermus thermophilus GCH1 (RCSB Protein Data Bank: 1WUR). The GCH1 protein of the FolE protein of R. monacensis was modelled based on previous structural determination on T. thermophilus (Tanaka et al., 2005).

In addition, multiple sequences were aligned using amino acid sequences of the FolE protein of R. monacensis and its orthologs with structures available in the RCSB Protein Data Bank. The multiple sequence alignment of the GCH1 protein sequences was created using Clustal Omega.

Expression of recombinant GST-FolE fusion protein in E. coli

Overexpression of GST-FolE protein in E. coli was done using the pET system (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), following the company’s instructions. E. coli BL21(DE3) strain (F– ompT hsdSB (rB–mB–) gal dcm (DE3)) (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) were transformed with the pET41a(+)−folE plasmid and grown in 100 mL of LB broth with 100 mg/L kanamycin. Once an optical density of 0.5 at 590 nm was reached, Isopropyl-beta- D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Gold Biotechnology, St. Louis, MO) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM and the culture continued to shake at 37°C for 4 hours. The culture was then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min, and the cell pellets were resuspended in 5 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The cell suspension was subjected to sonication and centrifuged at 4°C for 30 min at 16,100 × g. The insoluble fraction was resuspended in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.6, plus 10% N-lauroyl sarcosinate (sarkosyl) (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium) and 10 mM beta-ercaptoethanol (β-ME) (Fisher Scientific, Tampa, FL). The sample was incubated overnight on a rocker at room temperature and the soluble and insoluble fractions were separated by centrifugation at 16,100 × g for 90 min at 4°C.

Purification of recombinant GST-FolE fusion protein

Affinity purification of GST-FolE protein was done using GST-affinity resin (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), following the company’s instructions. After treatment with sarkosyl, solubilized GST-FolE was diluted 1:5 into TBS, and sarkosyl was sequestered by the addition of 40 mM (3-((3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio)-1-propanesulfonate) (CHAPS) (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium), 4% Triton X-100 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 10 mM β-ME, and 20 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), along with 1 mM PMSF and 1 mM HALT protease cocktail (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). The sample was mixed at room temperature on a rocker for 30 min before incubation with GST Bind Resin (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) at room temperature while rocking for 2 hours. The resin was washed with 10 mL of GST Bind/Wash Buffer (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. Proteins were eluted using 5 mL of elution buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 10.2 mM reduced glutathione) (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) plus 1 mM Triton X-100 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. Protein concentration was determined using absorbance at 280 nm, and eluates were stored in 20% glycerol at −80°C.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot

Protein levels were determined by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Samples of the overexpression and purification of the GST-FolE protein in SDS sample buffer (750 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 40% glycerol, 0.002% Bromophenol blue, 8% SDS, 5% β-ME) were electrophoresed across a 12% Criterion TGX polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in running buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 8.3, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS) at 200 V for 55 minutes. Proteins were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (Fisher Scientific) and documented using an AlphaImager HP (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA) with transilluminating white light. The overexpression of GST-FolE was verified by Western blot using a PVDF (polyvinyl difluoride) membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and probing with a 1:500 dilution of mouse monoclonal anti-GST antibody (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 2 hours at room temperature. The membrane was then incubated with a 1:20,000 dilution of Immun-Star Goat Anti-Mouse-Horse Radish Peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature followed by documentation using Clarity Western ECL Substrates (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and the C-Digit digital imager (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE).

In vitro enzyme assay

The recombinant GST-FolE fusion protein of R. monacensis was tested for GTP cyclohydrolase I (GCH1) activity on a SpectraMax i3x plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at 37°C for 60 min using the absorbance at 330 nm associated with the reaction product (7,8-dihydroneopetrin triphosphate; DHNTP) and a molar extinction coefficient of 6,300 M−1 (Thony et al., 1992). Reactions, carried out in duplicates, contained 1 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.9, 1 mM KCl, 1 mM GTP (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and purified enzyme at various concentrations (100 μg, 125 μg, 150 μg, 175 μg, and 200 μg) in a 96-well Costar clear UV microplate (Corning, Corning, NY) in final volumes of 200 μL. One unit of enzyme is defined as the amount required to produce 1 μmol of DHNTP per minute. For the GCH1 assay at different temperatures, the reaction was carried out at 25°C, 32°C, and 37°C using 100 μg of recombinant GST-FolE.

A buffer only control and GST-GltA recombinant protein served as two negative controls in the assay. Briefly, the gltA gene of R. monacensis strain Humboldt, which encodes for citrate synthetase, was also cloned in pET41a(+). The GST-GltA recombinant protein was overexpressed in BL21 (DE3) E. coli and purified by affinity chromatography, as previously described (Bodnar et al., 2018).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

For this study, rickettsial FolE, the first enzyme in the folate biosynthesis pathway, was used to expand upon the characterization of R. monacensis strain Humboldt regarding de novo biosynthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin. The 7,8-dihydroneopterin triphosphate-synthesizing enzyme GTP cyclohydrolase I from R. monacensis was shown to be functional. All together, the description, in silico assessment of the protein structure, overexpression, purification, and functional characterization of recombinant GST-FolE protein of R. monacensis are reported.

Following sequencing of the pET41a(+)−folE plasmid, the resulting nucleotide sequence of the folE gene of R. monacensis strain Humboldt was compared to the GenBank database by BLASTn. BLAST results confirmed that the nucleotide sequence of the folE gene of R. monacensis is identical to the folE sequence of Rickettsia species phylotype G021 (renamed to R. monacensis strain Humboldt in 2019, GenBank accession number KT225570) (Alowaysi et al., 2019). The homolog with the closest nucleotide identity to folE of R. monacensis strain Humboldt belonged to R. monacensis strain IrR/Munich (99% identity, GenBank accession number LN794217) (Oren and Garrity, 2019; Simser et al., 2002). Among the other rickettsiae displaying homology were R. australis strain Cutlack (91% identity, CP003338), R. akari strain Hartford (91%, CP000847), and other spotted fever group rickettsiae (Suppl. Table 1). These results confirmed our previous phylogenetic tree analysis findings that the folE gene of R. monacensis strain Humboldt, formerly Rickettsia species phylotype G021, is highly homologous to the folE gene of spotted fever group rickettsiae (Hunter et al., 2015). In addition to defining sequence homology, BPROM prediction of bacterial promoters of the folE gene of R. monacensis revealed probable E. coli sigma-70-like promoter sequences of TTGATG and TGTTAAAGT, with an interval of 14 bp, corresponding to the −35 and −10 regions, respectively (Suppl. Fig. 1). Overall, annotation of the folE nucleotide sequence suggested that R. monacensis strain Humboldt possesses a functional folE gene.

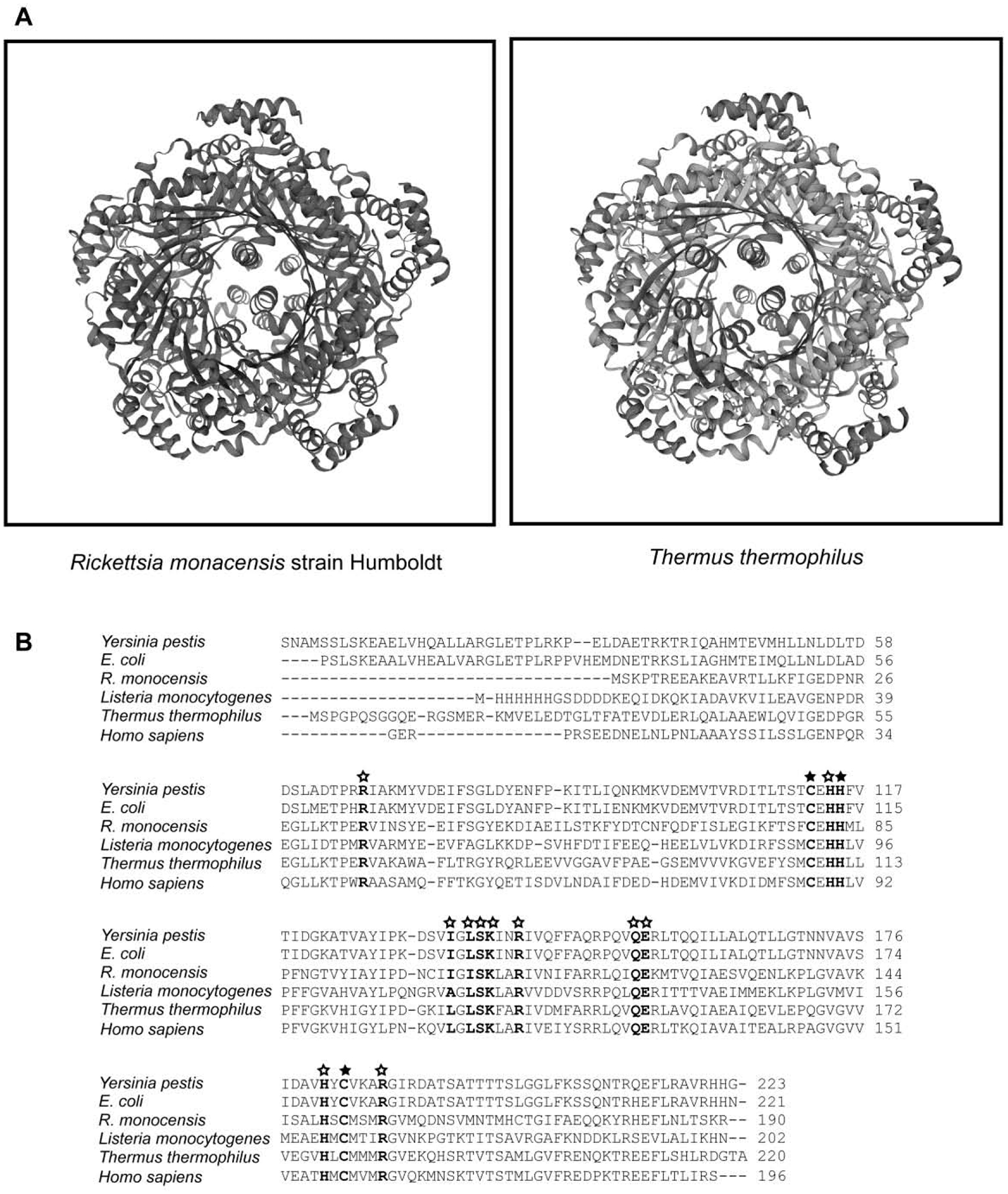

Analysis of the folE nucleotide sequence using NCBI’s BLASTx tool revealed a conserved core subunit of GTP cyclohydrolase I (GCH1) from a tunneling-fold (T-fold) structural superfamily (Fig. 1a) (Colloc’h et al., 2000). The GCH1 protein, which is one of the five proteins within the T-Fold superfamily, is responsible for catalyzing the conversion of GTP into 7,8-dihydroneopetrin triphosphate (Paranagama et al., 2017; Yim and Brown, 1976). Comparative protein structure modeling was carried out using a Swiss-Model web-based server between R. monacensis strain Humboldt and Thermus thermophilus as well as other GCH1 proteins with structures available in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (Tanaka et al., 2005). Based on structure homology modeling, the FolE protein of R. monacensis resembles other GCH1 proteins in exhibiting pentameric rings with a tunnel in the middle. This five-fold symmetry has a central β-barrel sandwiched by peripheral α-helices. Overall, the structure modeling confirms the FolE protein of R. monacensis is a GCH1 protein (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1:

Comparative protein structure modeling and sequence alignment between the GCH1 of Rickettsia monacensis strain Humboldt and other GCH1 proteins from prokaryotes and eukaryotes. 1A) The protein structure modeling of the GCH1 protein of R. monacensis strain Humboldt showed similar overall structure with other GCH1 proteins with structures available in the RCSB Protein Data Bank. 1B) Multiple alignment of GCH1 protein sequences using Clustal Omega. Amino acids residues that coordinate with the zinc ion are highlighted in bold and shown with filled stars. Other amino acids residues for the GTP binding sites of the GCH1 proteins are highlighted in bold and shown with empty stars.

An alignment of amino acid sequences of GCH1 proteins showed that the C-terminal part and the central region, in which the conserved core subunit of GCH1 proteins is located, are highly homologous between the GCH1 protein of R. monacensis strain Humboldt and other GCH1 proteins (Fig. 1b). The amino acid sequence alignment also showed that amino acid residues which coordinate directly with zinc ions at the active sites of the GCH1 proteins, are all conserved in the GCH1 protein of R. monacensis. Specifically, the residues of the GCH1 protein of R. monacensis are Cys- 80 (corresponding to Cys-110 of E. coli GCH1 protein, accession number 1FBX_A), His-83 (His-113), and Cys-151 (Cys-181) (Auerbach et al., 2000; Nar et al., 1995) (Fig. 1b). In addition, all residues of the GCH1 protein of R. monacensis that participate in formation of the product dihydroneopterin triphosphate, specifically His-82 (His-112 of E. coli GCH1 protein) and His-149 (His-179), are identical to other GCH1 proteins (Tanaka et al., 2005). Eleven residues established for predicting the GTP binding sites are all conserved in the GCH1 protein of R. monacensis. Specifically, the eleven residues are Arg-35 of the GCH1 protein of R. monacensis (Arg-65 of E. coli GCH1 protein), His-82 (His-112), Ile-102 (Ile-132), Leu-104 (Leu-134), Ser-105 (Ser-135), Lys-106 (Lys-136), Arg-109 (Arg-139), Gln-121 (Gln-151), Glu-122 (Glu-152), His-149 (His-179), and Arg-155 (Arg-185) (Fig. 1b) (Kumpornsin et al., 2014; Nar et al., 1995). It was previously reported that all eleven residues are involved in interacting with GTP, either by the side chain or backbone of the residues (Paranagama et al., 2017).

The GCH1 amino acid sequence alignment in this study and other published works demonstrate wide phylogenetic distribution of the GCH1 proteins in prokaryotes and eukaryotes (Paranagama et al., 2017). However, recent phylogenomics studies revealed that many rickettsiae are incapable of producing certain B vitamins (Driscoll et al., 2017). In fact, remarkable reductive genomic evolution is evident across the Rickettsiales (Darby et al., 2007; Diop et al., 2019), with Rickettsiaceae displaying the greatest metabolic loss (Fuxelius et al., 2007; Nakayama et al., 2008). These deficiencies are well established for Rickettsia, where genomic studies have consistently confirmed a reduced metabolic capacity (Gillespie et al., 2008), especially surrounding the synthesis of B vitamins, pentose phosphates, and other cofactors (Renesto et al., 2005). These vital molecules include thiamine, riboflavin, flavin adenine dinucleotide, biotin, glutathione, and the B vitamin pyridoxal phosphate (Driscoll et al., 2017). There are phylogenetic indications suggestive of a once functional tetrahydrofolate synthesis pathway existing in rickettsiae (Driscoll et al., 2017). However, a general deterioration of the folate pathway has been demonstrated in many rickettsial genomes (Driscoll et al., 2017; Hunter et al., 2015). Conversely, rickettsial acquisition of foreign genes by horizontal transfer is a constant process, and DNA containing metabolic elements has a high tendency for genetic mobility (Diop et al., 2019; El Karkouri et al., 2016; Merhej et al., 2011). It has been suggested that conjugation genes are commonly present in genomes of the genus Rickettsia and that horizontal gene transfer of the conjugation genes occurs extensively in Rickettsia (Diop et al., 2019; Weinert et al., 2009). The reacquisition of functional folate genes by Rickettsia has not been explored. The fact that R. monacensis strain Humboldt maintains functional genes of the folate pathway amidst a high propensity, even among very close relatives, for metabolic reduction again suggests considerable selection for these genes.

It was recently proposed that the lack of a complete folate pathway in Rickettsia necessitates the uptake of tetrahydrofolate from their host (Driscoll et al., 2017). However, no transporters (Eitinger et al., 2011; Erkens et al., 2012; Rodionov et al., 2009) known to be involved in importing folate in prokaryotes (Xu et al., 2013), were identified (Driscoll et al., 2017), and it is well established that B vitamins are below nutritional levels in strict, hematophagous diets (Akman et al., 2002; Hosokawa et al., 2010; Nikoh et al., 2014). The conclusions drawn about folate biosynthesis and R. monacensis strain Humboldt from this strictly genetic analysis were largely disaffirmed when our lab successfully demonstrated in vitro reduction of 7,8-dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate by the purified recombinant FolA enzyme from R. monacensis (Bodnar et al., 2018). The work by Driscoll et al. (2017) demonstrates that rickettsial metabolomics, especially surrounding vitamin acquisition, remain inadequately understood.

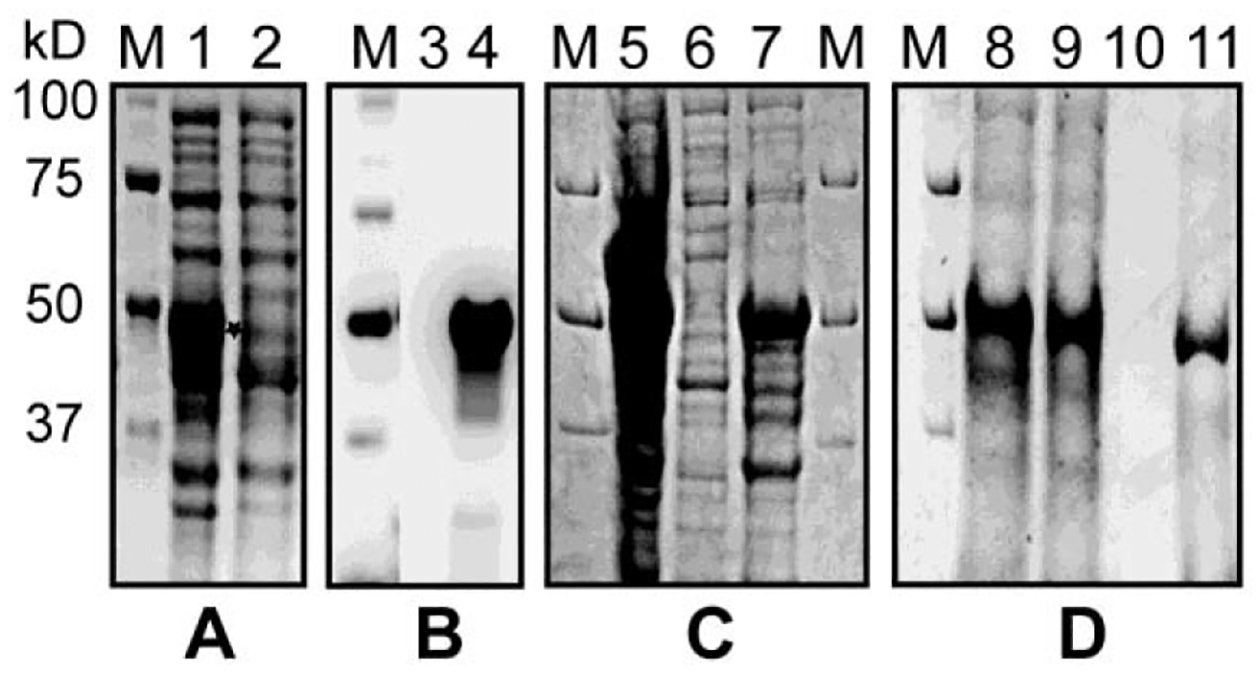

Recombinant FolE of R. monacensis was overexpressed using the pET-41a(+) expression vector and BL21 (DE3) E. coli as the heterologous host. Early log-phase induction with 1 mM IPTG and incubation at 37°C for 4 hours were optimal conditions for overexpressing recombinant GST-FolE of R. monacensis. Recombinant GST-FolE migrated as anticipated by SDS-PAGE at 49 kDa (Fig. 2a). Expression of the recombinant GST-FolE protein was verified by Western blot using an anti-GST monoclonal antibody (Fig. 2b). Because the majority of recombinant GST-FolE of R. monacensis had formed inclusion bodies (Fig. 2c), we used techniques described by Tao et al. (Tao et al., 2010) for solubilization for subsequent purification. This involved solubilization with 10% sarkosyl, followed by refolding by dilution under reducing conditions. GST-fusion proteins cannot bind to the GSH affinity ligand in the presence of sarkosyl, so CHAPS and Triton X-100 were added to the diluted sample to sequester sarkosyl away from the GST tag during affinity purification (Tao et al., 2010). Based on Coomassie staining, it was estimated that the purity of the GST-FolE of R. monacensis, after the affinity chromatography purification, was about 90% (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

Expression and purification of recombinant GST-FolE protein of Rickettsia monacensis strain Humboldt in E. coli (DE3). Samples of FolE expression culture lysates in E. coli were electrophoresed across a 12% Criterion TGX polyacrylamide gel followed by stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 and visualized with transilluminating white light or transferred to PVDF and probed with anti-GST antibody for Western blotting. A) Coomassie blue staining of total protein expression of GST-FolE, visualized on a 12% polyacrylamide gel. M: Molecular markers (Bio-Rad); Lane 1: IPTG-induced FolE expression culture lysate. The star shows the location of overexpressed GST-FolE protein; Lane 2: Culture lysate from uninduced control of E. coli. B) Western blot of GST-FolE protein, visualized on a PVDF membrane with chemiluminescent detection. M: Molecular markers; Lane 3: Culture lysate from uninduced control of E. coli. Lane 4: IPTG-induced FolE expression culture lysate; C) Coomassie blue staining of soluble expression of recombinant GST-FolE protein of strain Humboldt. Overexpressed GST-FolE lysates were sonicated and soluble and insoluble fractions were separated. M: Molecular markers; Lane 5: IPTG-induced FolE expression culture lysate; Lane 6: Soluble fraction; Lane 7: Insoluble fraction. D) The recombinant GST-FolE protein was purified by affinity column. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and stained by Coomassie blue staining. M: Molecular markers; Lane 8: IPTG-induced FolE expression culture lysate; Lane 9: Flow through; Lane 10: Wash; Lane 11: Eluate.

To demonstrate the function of the purified GST-FolE protein of R. monacensis strain Humboldt, GCH1 enzyme activity was measured at 37°C, which is a standard temperature for GCH1 assays (Kolinsky and Gross, 2004; Thony et al., 1992; Werner et al., 1996). The in vitro GCH1 assay directly measures the accumulation of DHNTP over time since DHNTP has a significantly greater absorbance at 330 nm than GTP (Bracher et al., 2001). At 37°C, a linear increase in absorbance over a 60 min time period was observed, indicating DHNTP accumulation (Fig. 3a). Of the five GST-FolE concentrations tested (100 μg, 125 μg, 150 μg, 175 μg, 200 μg, in duplicates), 150 μg proved optimal for determination of specific activity. It was estimated that 150 μg GST-FolE of R. monacensis had a specific GCH1 activity of 0.81 U/μg, which is comparable to the specific activity of other bacterial GCH1 proteins (De Saizieu et al., 1995; Yim and Brown, 1976) but is a considerably higher value than that reported for the GCH1 protein of Nocardia species and E. coli (Bracher et al., 1998; He et al., 2004). In contrast, there was relatively no increase in absorbance at 330 nm for the two negative controls (the GST-GltA recombinant protein and buffer control) (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

In vitro assay of GCH1 activity from recombinant GST-FolE protein from Rickettsia monacensis strain Humboldt. A) This graph represents the specific activity assays for FolE using different concentrations of the recombinant GST-FolE protein of R. monacensis strain Humboldt (in duplicates). All assays measured the absorbance of light at 330 nm for 60 min at 37°C using a SpectraMax i3x plate reader. The GCH1 activity of R. monacensis strain Humboldt GST-FolE protein at concentration of 100 μg, 125 μg, 150 μg, 175 μg, and 200 μg is shown with filled triangle, empty triangle, filled circle, empty circle, and empty diamond, respectively. The GST-GltA and the buffer control is shown as filled diamond and filled star, respectively. OD: optical density at 330 nm. B) An increase in OD330 at 10 mins intervals over 60 mins at 25°C, 32°C, and 37°C was used to measure the formation of 7,8-dihydroneopterin triphosphate using a SpectraMax i3x plate reader. OD: optical density. The GCH1 activity of R. monacensis strain Humboldt GST-FolE protein at 37°C, 32°C, and 25°C is shown with filled circle, filled triangle, and empty circle, respectively. The buffer control is shown as empty triangle

Hard ticks thrive in habitats that allow them to feed on a wide range of vertebrate hosts. Since R. monacensis live in ovaries, midguts, and other tissues of I. pacificus (Phan et al., 2011; Bagheri, 2017), the bacterium must have the ability to colonize in ticks with two different temperatures: ambient temperature and vertebrate body temperature. Flat ticks are subject to greater variations in ambient temperature (Greenfield, 2011), whereas engorged ticks experience a rapid increase in temperature inside the midgut as a result of blood meal. Since acquisition of a blood meal by I. pacificus significantly increases the burden of R. monacensis in ticks, and folate is important for cell growth and division (Cheng et al., 2013), we tested if the function of GST-FolE protein of R. monacensis is up-regulated in response to the temperature increase. Temperature effects on FolE activity were tested by recording the absorbance change of the reaction at 25°C, 32°C, and 37°C, using 100 μg of purified enzyme in each reaction. The highest activity was seen at 37°C, with 25°C and 32°C yielding similar, lower activities (Fig. 3b). These data coincide with a previous report describing an increase in FolE enzyme activity associated with rising temperature up to 50°C (Kumpornsin et al., 2014). Moreover, the optimal temperature of bacterial GCH1 enzyme has been reported to be within a range of 40°C–56°C (He and Rosazza, 2003; Yoo, Han, Ko, & Bang, 1998). As a matter of fact, differential gene expression of the GTP cyclohydrolase I gene has been reported in Ehrlichia canis, a bacterium in Rhipicephalus ticks (Dias et al., 2019). This is important because the digestion of blood is accompanied by the growth of new cuticle and visceral tissues in the tick (Sonenshine, 1993), and therefore drives a need for increased folate production corresponding to a higher enzyme activity at 37°C. Still, all three temperatures tested stimulated substantially greater product formation than the buffer-only negative control (Fig. 3b).

Folate has been reported to contribute to the fitness of the Tsetse fly (Snyder and Rio, 2015). However, a report demonstrating the lack of thiamin synthesis genes in the I. pacificus-associated bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, suggests that the growth of bacteria in ticks is not dependent on the ability of endogenous generation of all vitamins. Also, B. burgdorferi viability is unaltered under conditions of thiamin deficiency (Zhang et al., 2016), suggesting an intricate complexity existing within the evolutionary forces of bacteria and ticks (Howick and Lazzaro, 2014). There are vast differences in the genetic capabilities of bacterial symbionts of ticks, differences that may have helped shape the evolutionary trajectories of tick hosts (Hunter et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016).

The cloning and annotation of the folE gene, followed by the overexpression and in vitro enzymatic assaying of the recombinant GST-FolE protein, demonstrate that the FolE of R. monacensis is a GCH1 protein of the folate biosynthesis pathway. The results of this study, along with our previous report of dihydrofolate reductase enzyme of the FolA protein of strain Humboldt, strengthen the hypothesis that R. monacensis strain Humboldt plays a functional role in the micronutrient acquisition process of I. pacificus; specifically, the synthesis of the vital metabolic co-factor folate. Importantly, I. pacificus also plays host to non-rickettsial organisms that demonstrate genetic potential for producing essential micronutrients including folate (Swei and Kwan, 2017).

CONCLUSIOS

This work has helped bridge our understanding of the interactions driving bacteria-tick relationships. In particular, the production of a folate precursor by an enzyme of R. monacensis strain Humboldt was confirmed. By showing the functionality of the folE gene, we have reinforced the body of evidence supporting the idea of de novo folate synthesis by R. monacensis. There is special importance in demonstrating the function of FolE; it initiates the first reaction in folate biosynthesis, regulating pathway flux by committing GTP to pterin synthesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Core Research Facility of Humboldt State University for the support in performing in vitro enzymatic assay. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [1 R15 AI099902-01].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in this study.

REFERENCES

- Akman L, Yamashita A, Watanabe H, Oshima K, Shiba T, Hattori M, Aksoy S, 2002. Genome sequence of the endocellular obligate symbiont of tsetse flies, Wigglesworthia glossinidia. Nat. Genet 32, 402–407. doi: 10.1038/ng986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alowaysi M, Chen J, Stark S, Teague K, LaCourse M, Proctor J, Vigil K, Corrigan J, Harding A, Li J, Kurtti T, Zhong J, 2019. Isolation and characterization of a Rickettsia from the ovary of a Western black-legged tick, Ixodes pacificus. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 10, 918–923. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach G, Herrmann A, Bracher A, Bader G, Gutlich M, Fischer M, Neukamm M, Garrido-Franco M, Richardson J, Nar H, Huber R, Bacher A, 2000. Zinc plays a key role in human and bacterial GTP cyclohydrolase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 97, 13567–13572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240463497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri G, Lehner JD, Zhong J, 2017. Enhanced detection of Rickettsia species in Ixodes pacificus using highly sensitive fluorescence in situ hybridization coupled with Tyramide Signal Amplification. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 8, 915–921. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann P, 2005. Biology bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts of plant sap-sucking insects. Annu. Rev. Microbiol 59, 155–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson MJ, Gawronski JD, Eveleigh DE, Benson DR, 2004. Intracellular symbionts and other bacteria associated with deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis) from Nantucket and Wellfleet, Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 70, 616–620. doi: 10.1128/aem.70.1.616-620.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar JL, Fitch S, Rosati A, Zhong J, 2018. The folA gene from the Rickettsia endosymbiont of Ixodes pacificus encodes a functional dihydrofolate reductase enzyme. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 9, 443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher A, Eisenreich W, Schramek N, Ritz H, Gotze E, Herrmann A, Gütlich M, Bacher A, 1998. Biosynthesis of pteridines. NMR studies on the reaction mechanisms of GTP cyclohydrolase I, pyruvoyltetrahydropterin synthase, and sepiapterin reductase. J. Biol. Chem 273, 28132–28141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher A, Schramek N, Bacher A, 2001. Biosynthesis of pteridines. Stopped-flow kinetic analysis of GTP cyclohydrolase I. Biochemistry 40, 7896–7902. doi: 10.1021/bi010322v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budachetri K, Gaillard D, Williams J, Mukherjee N, Karim S, 2016. A snapshot of the microbiome of Amblyomma tuberculatum ticks infesting the gopher tortoise, an endangered species. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 7, 1225–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng D, Lane RS, Moore BD, Zhong J, 2013. Host blood meal-dependent growth ensures transovarial transmission and transstadial passage of Rickettsia sp phylotype G021 in the western black-legged tick (Ixodes pacificus). Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 4, 421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng D, Vigil K, Schanes P, Brown RN, Zhong J, 2013. Prevalence and burden of two rickettsial phylotypes (G021 and G022) in Ixodes pacificus from California by real-time quantitative PCR. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 4, 280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colloc’h N, Poupon A, Mornon JP, 2000. Sequence and structural features of the T-fold, an original tunnelling building unit. Proteins 39, 142–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby AC, Cho NH, Fuxelius HH, Westberg J, Andersson SG, 2007. Intracellular pathogens go extreme: genome evolution in the Rickettsiales. Trends Genet. 23, 511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Saizieu A, Vankan P, van Loon AP, 1995. Enzymic characterization of Bacillus subtilis GTP cyclohydrolase I. Evidence for a chemical dephosphorylation of dihydroneopterin triphosphate. Biochem. J 306, 371–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias F, Couto J, Ferrolho J, Seron GS, Bell-Sakyi L, Antunes S, Domingos A, 2019. Folate pathway modulation in Rhipicephalus ticks in response to infection. Transbound. Emerg. Dis doi: 10.1111/tbed.13231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diop A, Raoult D, Fournier PE, 2019. Paradoxical evolution of rickettsial genomes. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 10, 462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll TP, Verhoeve VI, Guillotte ML, Lehman SS, Rennoll SA, Beier-Sexton M, Rahman MS, Azad AF, Gillespie JJ, 2017. Wholly Rickettsia! Reconstructed Metabolic Profile of the Quintessential Bacterial Parasite of Eukaryotic Cells. MBio 8. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00859-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duron O, Morel O, Noel V, Buysse M, Binetruy F, Lancelot R, Loire E, Ménard C, Bouchez O, Vavre F, Vial L, 2018. Tick-Bacteria Mutualism Depends on B Vitamin Synthesis Pathways. Curr. Biol 28, 1896–1902 e1895. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitinger T, Rodionov DA, Grote M, Schneider E, 2011. Canonical and ECF-type ATP-binding cassette importers in prokaryotes: diversity in modular organization and cellular functions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 35, 3–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Karkouri K, Pontarotti P, Raoult D, Fournier PE, 2016. Origin and Evolution of Rickettsial Plasmids. PLoS One 11, e0147492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P, Moran NA, 2013. The gut microbiota of insects - diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 37, 699–735. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkens GB, Majsnerowska M, ter Beek J, Slotboom DJ, 2012. Energy coupling factor-type ABC transporters for vitamin uptake in prokaryotes. Biochemistry 51, 4390–4396. doi: 10.1021/bi300504v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman DP, Loomis EC, 1984. The ticks of California (Acari:Ixodida). Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuxelius HH, Darby A, Min CK, Cho NH, Andersson SG, 2007. The genomic and metabolic diversity of Rickettsia. Res. Microbiol 158, 745–753. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JJ, Williams K, Shukla M, Snyder EE, Nordberg EK, Ceraul SM, Dharmanolla C, Rainey D, Soneja J, Shallom JM, Vishnubhat ND, Wattam R, Purkayastha A, Czar M, Crasta O, Setubal JC, Azad AF, Sobral BS, 2008. Rickettsia phylogenomics: unwinding the intricacies of obligate intracellular life. PLoS One 3, e2018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield BPJ, 2011. Environmental parameters affecting tick (Ixodes ricinus) distribution during the summer season in Richmond Park, London. Bioscience Horizons: Int. J. Stud. Res. 4, 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Guy EC, Stanek G, 1991. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Lyme disease by the polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Pathol 44, 610–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He A, Rosazza JP, 2003. GTP cyclohydrolase I: purification, characterization, and effects of inhibition on nitric oxide synthase in nocardia species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 69, 7507–7513. doi: 10.1128/aem.69.12.7507-7513.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He A, Simpson DR, Daniels L, Rosazza JP, 2004. Cloning, expression, purification, and characterization of Nocardia sp. GTP cyclohydrolase I. Protein Expr. Purif 35, 171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa T, Koga R, Kikuchi Y, Meng XY, Fukatsu T, 2010. Wolbachia as a bacteriocyte-associated nutritional mutualist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 769–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911476107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howick VM, Lazzaro BP, 2014. Genotype and diet shape resistance and tolerance across distinct phases of bacterial infection. BMC Evol. Biol 14, 56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DJ, Torkelson JL, Bodnar J, Mortazavi B, Laurent T, Deason J, Thephavongsa K, Zhong J, 2015. The Rickettsia Endosymbiont of Ixodes pacificus Contains All the Genes of De Novo Folate Biosynthesis. PLoS One 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husnik F, 2018. Host-symbiont-pathogen interactions in blood-feeding parasites: nutrition, immune cross-talk and gene exchange. Parasitology 145, 1294–1303. doi: 10.1017/S0031182018000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolinsky MA, Gross SS, 2004. The mechanism of potent GTP cyclohydrolase I inhibition by 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine: requirement of the GTP cyclohydrolase I feedback regulatory protein. J. Biol. Chem 279, 40677–40682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpornsin K, Kotanan N, Chobson P, Kochakarn T, Jirawatcharadech P, Jaruampornpan P, Yuthavong Y, Chookajorn T, 2014. Biochemical and functional characterization of Plasmodium falciparum GTP cyclohydrolase I. Malar. J 13, 150. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane RS, Brown RN, Piesman J, Peavey CA, 1994. Vector competence of Ixodes pacificus and Dermacentor occidentalis (Acari: Ixodidae) for various isolates of Lyme disease spirochetes. J. Med. Entomol 31, 417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merhej V, Notredame C, Royer-Carenzi M, Pontarotti P, Raoult D, 2011. The rhizome of life: the sympatric Rickettsia felis paradigm demonstrates the random transfer of DNA sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol 28, 3213–3223. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Yamashita A, Kurokawa K, Morimoto T, Ogawa M, Fukuhara M, Urakami H, Ohnishi M, Uchiyama I, Ogura Y, Ooka T, Oshima K, Tamura A, Hattori M, Hayashi T, 2008. The Whole-genome sequencing of the obligate intracellular bacterium Orientia tsutsugamushi revealed massive gene amplification during reductive genome evolution. DNA Res. 15, 185–199. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsn011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nar H, Huber R, Auerbach G, Fischer M, Hosl C, Ritz H, Bracher A, Meining W, Eberhardt S, Bacher A, 1995. Active site topology and reaction mechanism of GTP cyclohydrolase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 92, 12120–12125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoh N, Hosokawa T, Moriyama M, Oshima K, Hattori M, Fukatsu T, 2014. Evolutionary origin of insect-Wolbachia nutritional mutualism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, 10257–10262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409284111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoh N, Hosokawa T, Oshima K, Hattori M, Fukatsu T, 2011. Reductive evolution of bacterial genome in insect gut environment. Genome Biol. Evol 3, 702–714. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren A, Garrity G, 2019. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 69, 2627–2629. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett KA, Lane RS, 2001. Life cycle of Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae): timing of developmental processes under field and laboratory conditions. J. Med. Entomol 38, 684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranagama N, Bonnett SA, Alvarez J, Luthra A, Stec B, Gustafson A, Iwata-Reuyl D, Swairjo MA, 2017. Mechanism and catalytic strategy of the prokaryotic-specific GTP cyclohydrolase-IB. Biochem. J 474, 1017–1039. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20161025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan JN, Lu CR, Bender WG, Smoak RM III, Zhong J, 2011. Molecular Detection and Identification of Rickettsia Species in Ixodes pacificus in California. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 11, 957–961. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renesto P, Ogata H, Audic S, Claverie JM, Raoult D, 2005. Some lessons from Rickettsia genomics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 29, 99–117. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter PJJRBK, Madigan JE, Barlough JE, Dumler JS, Brooks DL, 1996. Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) as a vector of Ehrlichia equi (Rickettsiales: Ehrlichieae). J. Med. Entomol 33, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov DA, Hebbeln P, Eudes A, ter Beek J, Rodionova IA, Erkens GB, Slotboom DJ, Gelfand MS, Osterman AL, Hanson AD, Eitinger T, 2009. A novel class of modular transporters for vitamins in prokaryotes. J. Bacteriol 191, 42–51. doi: 10.1128/JB.01208-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simser JA, Palmer AT, Fingerle V, Wilske B, Kurtti TJ, Munderloh UG, 2002. Rickettsia monacensis sp. nov., a spotted fever group Rickettsia, from ticks (Ixodes ricinus) collected in a European city park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 68, 4559–4566. doi: 10.1128/aem.68.9.4559-4566.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder AK, Rio RV, 2015. “Wigglesworthia morsitans” Folate (Vitamin B9) Biosynthesis Contributes to Tsetse Host Fitness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 81, 5375–5386. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00553-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenshine DE, 1993. Biology of Ticks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swei A, Kwan JY, 2017. Tick microbiome and pathogen acquisition altered by host blood meal. ISME J. 11, 813–816. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajeri S, Razmi G, Haghparast A, 2016. Establishment of an Artificial Tick Feeding System to Study Theileria lestoquardi Infection. PLoS One. 11, e0169053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Nakagawa N, Kuramitsu S, Yokoyama S, Masui R, 2005. Novel reaction mechanism of GTP cyclohydrolase I. High-resolution X-ray crystallography of Thermus thermophilus HB8 enzyme complexed with a transition state analogue, the 8-oxoguanine derivative. J. Biochem 138, 263–275. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao H, Liu W, Simmons BN, Harris HK, Cox TC, Massiah MA, 2010. Purifying natively folded proteins from inclusion bodies using sarkosyl, Triton X-100, and CHAPS. Biotechniques 48, 61–64. doi: 10.2144/000113304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thony B, Leimbacher W, Burgisser D, Heizmann CW, 1992. Human 6-pyruvoyltetrahydropterin synthase: cDNA cloning and heterologous expression of the recombinant enzyme. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 189, 1437–1443. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90235-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjong E, Mohiuddin SS, 2019. Biochemistry, Tetrahydrofolate StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Tjong+%26+Mohiuddin%2C+2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert LA, Welch JJ, Jiggins FM, 2009. Conjugation genes are common throughout the genus Rickettsia and are transmitted horizontally. Proc. Biol. Sci 276, 3619–3627. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G, Wachter H, 1996. High-performance liquid chromatographic methods for the quantification of tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthetic enzymes. J. Chromatogr. B. Biomed. Appl 684, 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Zhang M, Zhao Q, Yu F, Guo H, Wang C, He F, Ding J, Zhang P, 2013. Crystal structure of a folate energy-coupling factor transporter from Lactobacillus brevis. Nature 497, 268–271. doi: 10.1038/nature12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim JJ, Brown GM, 1976. Characteristics of guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase I purified from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem 251, 5087–5094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo JC, Han JM, Ko OH, Bang HJ, 1998. Purification and characterization of GTP cyclohydrolase I from Streptomyces tubercidicus, a producer of tubercidin. Arch. Pharm. Res 21, 692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Bian J, Deng Y, Smith A, Nunez RE, Li MB, Pal U, Yu AM, Qiu W, Ealick SE, Li C, 2016. Lyme disease spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi does not require thiamin. Nat. Microbiol 2, 16213. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.