Abstract

Background

Macrophages play pivotal roles in tumor progression and the response to anticancer therapies, including radiotherapy (RT). Dual oxidase (DUOX) 1 is a transmembrane enzyme that plays a critical role in oxidant generation.

Methods

Since we found DUOX1 expression in macrophages from human lung samples exposed to ionizing radiation, we aimed to assess the involvement of DUOX1 in macrophage activation and the role of these macrophages in tumor development.

Results

Using Duox1−/− mice, we demonstrated that the lack of DUOX1 in proinflammatory macrophages improved the antitumor effect of these cells. Furthermore, intratumoral injection of Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages significantly enhanced the antitumor effect of RT. Mechanistically, DUOX1 deficiency increased the production of proinflammatory cytokines (IFNγ, CXCL9, CCL3 and TNFα) by activated macrophages in vitro and the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II in the membranes of macrophages. We also demonstrated that DUOX1 was involved in the phagocytotic function of macrophages in vitro and in vivo. The antitumor effect of Duox1−/− macrophages was associated with a significant increase in IFNγ production by both lymphoid and myeloid immune cells.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that DUOX1 is a new target for macrophage reprogramming and suggest that DUOX1 inhibition in macrophages combined with RT is a new therapeutic strategy for the management of cancers.

Keywords: immunotherapy, interferon inducers, macrophages, radiotherapy, radioimmunotherapy

Background

The roles of macrophages in tumor and healthy tissue responses to radiotherapy (RT) are well known and macrophages are considered a target to improve the therapeutic index of RT.1 2 RT is able to reprogram tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) from an anti-inflammatory phenotype into a proinflammatory phenotype, exerting antitumor activity.1 In healthy tissue, anti-inflammatory macrophages promote radio-induced tissue toxicity.2 As professional phagocytic cells, macrophages use oxidative burst products (reactive oxygen species (ROS)) to eliminate pathogens.3 ROS are produced by NADPH oxidase (NOX) enzymes, which comprise five NOX (1 to 5) and two dual oxidases (DUOX), DUOX1 and DUOX2.4 In contrast to those of DUOXs, the roles of several NOXs, such as NOX2, in macrophage activation, polarization and responses to RT have been reported.5 6 DUOX 1 is a calcium-dependent transmembrane enzyme that mainly produces hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).4 7 The deregulation of DUOX1 activity induces redox system dysregulation that leads to tumorigenesis.8 In human thyroid cells, DUOX1 is involved in radio-induced DNA damage.9 Pioneering studies by the Van der Vliet group showed that DUOX1 was involved in EGF/EGFR pathway regulation, and EGFR signaling is known for its protumoral role in lung cancers.8 Despite these reports, the roles of DUOX1 in immune cells have not been thoroughly explored. Given the importance of the redox system in host immune defense against both pathogens and tumor cells,3 it is conceivable that DUOX1 is involved in immune cell functions. Interestingly, DUOX1 is expressed in both human monocyte-derived macrophages10 and T cells.11 Moreover, we found that macrophages in lung tissue samples from patients treated with RT expressed DUOX1. To investigate the involvement of DUOX1 in macrophage function during tumor progression and tumor responses to RT, we used DUOX1-deficient (Duox1−/−) mice.12 We showed that DUOX1 modulates the secretory profile, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II membrane expression and phagocytotic function of macrophages. We also found that DUOX1 deficiency improved the antitumor function of proinflammatory macrophages in vivo. Furthermore, Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages enhanced the efficacy of RT against both MC38 and TC1/Luc subcutaneous tumors. Interestingly, we showed that the antitumor effect of DUOX1 inhibition in proinflammatory macrophages combined with RT was associated with significant production of IFNγ by tumor-infiltrating lymphoid (CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and natural killers (NKs)) and myeloid cells (macrophages, Ly6Chigh monocytes and dendritic cells (DCs)).

Methods

Animal models

Animal procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the Ethical Committee CEEA 26 and in accordance with recommendations for the proper use and care of laboratory animals. For the subcutaneous tumor model, female C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) were purchased from Janvier Laboratories (France) and housed in the Gustave Roussy animal facility.

For bone marrow studies, Duox1−/− mice, which were previously described,12 were used. Duox1−/− mice were backcrossed onto the C57BJ/6F background for more than five generations to obtain wild-type (WT) littermates as a control. The mice on the C57BL/6F background were from Charles River Laboratories (France). Mice were housed in a pathogen-free facility at Gustave Roussy.

Bone morrow isolation and differentiation into macrophages

The femur and tibia of Duox1−/− and WT mice (8–10 weeks old) were flushed, and bone marrow was obtained. Erythrocytes were lysed using ACK Lysing Buffer (Gibco) for 5 min at room temperature. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifugation (400g, 20°C, 5 min), the cells were suspended and cultured in DMEM-F12 supplemented with both fetal bovine serum (FBS; 10%) and penicillin/streptomycin (1%). Bone marrow cells were incubated in the indicated medium at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 30 min. Then, the adherent cells (macrophage precursors) were washed using PBS, and the non-adherent cells were discarded. The adherent cells were incubated in fresh medium (DMEM-F12 containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) supplemented with either recombinant mouse GM-CSF or recombinant mouse M-CSF (R&D) at a concentration of 250 ng/mL. Recombinant GM-CSF was used to induce proinflammatory bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs), and recombinant M-CSF was used to induce anti-inflammatory BMDMs.13 After 6 days of culture, the BMDMs were a homogeneous adherent population14 and used for subsequent experiments.

Cytokine/chemokine array

Cytokine and chemokine concentrations in culture supernatants from in vitro–activated BMDMs and tumor tissue samples were profiled at Eve Technologies (Calgary, Canada). Protein extracts from tumor tissue samples were prepared by homogenization in RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete; Roche). The protein extracts were diluted to 4 mg/mL and analyzed at Eve Technologies using the multiplex Mouse Cytokine Array/Chemokine immunoassay, ref. MD31.

In vivo and in vitro phagocytosis assays

For phagocytosis assays, FluoSpheres Carboxylate-Modified Microspheres, 0.2 µm, red fluorescent (580/605), 2% solids (ThermoFisher) were used.

In vitro assay: 1 µL of FluoSpheres was added to 2×106 BMDMs (WT or Duox1−/−). Thirty minutes later, FluoSphere uptake by the BMDMs was assessed by flow cytometry.

Intraperitoneal injection of FluoSpheres: 200 µL of diluted FluoSpheres (1:20, in physiological serum) was injected intraperitoneally into WT or Duox1−/− mice. Two hours later, peritoneal lavage was performed for peritoneal macrophage isolation. FluoSphere uptake by peritoneal macrophages was assessed by flow cytometry.

Subcutaneous tumor model

For tumor engraftment, 106 MC38 cells or 5×105 TC1/Luc cells (luciferase-expressing TC1/Luc cells were generated by the HPV16 E6/E7 and c-H-ras retroviral transduction of lung epithelial cells of C57BL/6 origin) in a 50 µL volume (PBS) were injected subcutaneously. On day 8 (MC38 tumor model) or day 7 (TC1/Luc tumor model) post tumor cell injection, the tumors had reached ~100 mm3, and the mice were randomly allocated to different treatment groups. Tumor size was measured with an electronic caliper. Tumor volume was estimated from two-dimensional tumor measurements (volume=length×width2/2). The ethical endpoint for survival was a tumor volume exceeding 1200 mm3.

Tumor irradiation

Subcutaneous tumors were locally irradiated using a Varian Tube NDI 226 (X-ray machine; 250 keV, tube current: 15 mA, beam filter: 0.2 mm Cu). A single dose of 8 Gy was locally administered to the tumors.

Intratumoral injection of BMDMs

Mice were immobilized through anesthesia exposure (2% isoflurane). BMDMs or PBS (as a control) was injected into the tumor at 3.5×105 cells/100 mm3/25 µL (PBS).

BMDM staining using CellTracker

BMDMs were incubated for 45 min with CellTracker Green CMFDA Dye (ThermoFisher) at 37°C. Then, the BMDMs were washed and used in subsequent experiments.

Tumor dissociation

Tumors were digested using the Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) for 40 min at 37°C and 1500 rpm. The cells from the tumors were filtered using cell strainers (70 µm; Miltenyi Biotech) and used for flow cytometry experiments.

Flow cytometry staining protocol

For Fc receptor blocking, cell suspensions were incubated with purified anti-mouse CD16/32 (clone 93; BioLegend) for 10 min at 4°C.

For BMDM staining, anti-CD45 (30-F11), anti-F4/80 (BM8), anti-CD11c (N418), anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-ICAM-1 (YN1/1.7.4), anti-H-2Ld/H-2Db (MHC I, 28-14-8), anti-I-A/I-E (MHC II, M5/114.15.2), anti-CD206 (C068C2), anti-CD40 (3/23) and anti-CD71 (C2, BioLegend) were used at the appropriate dilutions.

Anti-CD45 (30-F11), anti-F4/80 (BM8) and anti-CD64 (X54-5/7.1) antibodies were used for staining of peritoneal macrophages, which were identified as CD45+ F4/80+ CD64+ cells. For tumor-infiltrating immune cell staining, anti-CD45 (REA737), anti-Ly6G (REA526), anti-CD11c (REA754; Miltenyi Biotec), anti-CD11b (M1/70; BD Horizon), anti-Ly6C (HK 1.4) and anti-D64 (X54-5/7.1; BioLegend) antibodies were used to identify macrophages (CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G− Ly6C−/low CD64+), inflammatory monocytes (CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G− Ly6Chigh CD64+) and cDC1 (CD45+ CD11b− CD11chigh Ly6G− Ly6C− CD64−). Anti-CD45 (REA737), anti-CD4 (REA604), anti-CD8 (REA983), anti-NK1.1 (REA1162), anti-CD25 (REA568; Miltenyi Biotec) and anti-CD11b (M1/70; BioLegend) antibodies were used to identify CD4+ T cells (CD45+ CD11b− CD4+), CD8+ T cells (CD45+ CD11b− CD8+), NK cells (CD45+ CD11b− NK1.1+) and regulatory T cells (CD45+ CD11b− CD4+ CD25+). Anti-PD-1 (REA802) and anti-CTLA4 (REA984; Miltenyi Biotec) antibodies were used. For membrane staining, cells were incubated with the antibody panel at the adapted concentrations for 20 min at 4°C. Then, cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at 4°C and permeabilized using Perm/Wash Buffer (BD Perm/Wash) for intracellular cytokine staining. Anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2; BD Horizon) was used. For intracellular staining, cells were pre-activated before membrane staining using Cell Activation Cocktail (with Brefeldin A; Biolegend) for 2 hours at 37°C. Propidium iodide (PI; Merck) was used to identify dead cells.

Absolute number calculations for different cell populations were performed by adding a fixed number (10,000) of non-fluorescent 10 µm Polybead Carboxylate Microspheres (Polysciences) to each sample, and the absolute number was defined according to the following formula: number of cells=number of acquired cells×10,000/number of acquired beads. The obtained cell number was extrapolated to the tumor weight for each sample.

Samples were acquired on an LSR Fortessa X20 (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with FACSDiva software, and data were analyzed with FlowJo V.10.0.7 software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism V.7. Student’s t-test was used to detect differences between two groups. One-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA were used to detect differences among multiple treatment groups. A p value equal to or less than 0.05 was considered significant (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001). Data are expressed as the mean±SEM.

Results

DUOX1 controls macrophage differentiation, activation and secretion in vitro

Immunohistological staining of lung biopsies from irradiated and non-irradiated patients revealed that DUOX1 was expressed in tissue-infiltrating macrophages (CD163+) (online supplementary file 1, figure S1), and there was strong staining in macrophages from irradiated tissue. We aimed to investigate whether DUOX1 is involved in macrophage activation and responses to microenvironmental stimuli.

jitc-2020-000622supp001.pdf (109.2KB, pdf)

jitc-2020-000622supp002.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

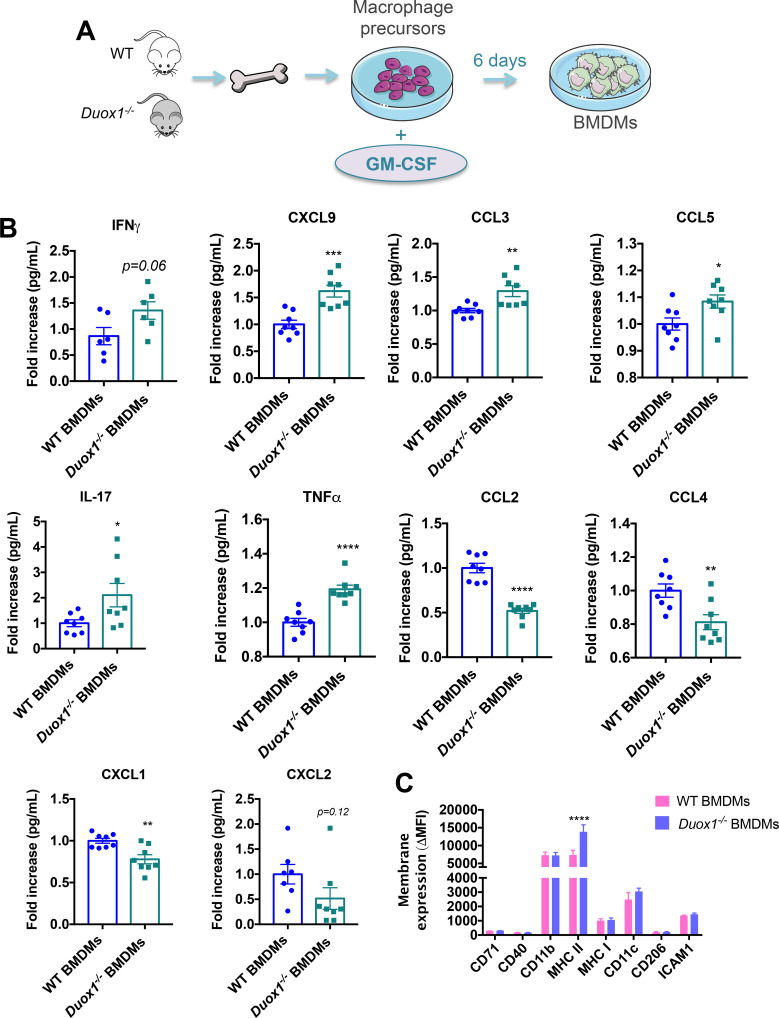

Bone marrow from WT and DUOX1-deficient (Duox1−/−) C57BL6 mice was harvested to isolate macrophage precursors, which were treated in vitro using GM-CSF to induce the proinflammatory BMDMs13 (figure 1A). The quantification of the supernatants showed that 6 days after in vitro activation, GM-CSF-activated Duox1−/− BMDMs increased the secretion of IFNγ, CXCL9, CCL3, CCL5, IL-17 and TNFα and decreased secretion of CCL2, CCL4, CXCL1 and CXCL2, compared with GM-CSF-activated WT BMDMs (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

DUOX1 controls macrophage differentiation, activation and secretion in vitro. (A) Macrophage precursors from WT or Duox1−/− bone marrow were cultured for 6 days in the presence of recombinant GM-CSF. (B) Supernatants from cultured bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) were analyzed for cytokine secretion. Data were obtained from two independent experiments and are represented as the mean±SEM. n=6–8, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 (Student’s t-test). (C) The phenotype of cultured BMDMs was analyzed by flow cytometry. Data were obtained from two independent experiments and are represented as the mean±SEM. n=4, ****p<0.0001 (two-way ANOVA).

Subsequently, we wanted to determine if DUOX1 deficiency could modify the membrane expression profile of activated BMDMs. Interestingly, we showed that MHC class II was more highly expressed in the GM-CSF-activated Duox1−/− BMDMs than in the GM-CSF-activated WT BMDMs (figure 1C). As expected, GM-CSF-activated Duox1−/− BMDMs exhibited significantly less H2O2 production than WT BMDMs (online supplementary file 1, figure S2). Macrophage precursors from WT and Duox1−/− mice was also treated in vitro using M-CSF to induce an anti-inflammatory phenotype13 (online supplementary file 1, figure S3A), and we determined the cytokine profile in the supernatants. We found that the secretome of M-CSF-activated BMDMs showed a decreased effect due to DUOX1 deficiency (online supplementary file 1, figure S3B). Similar to that observed for cytokine secretion, no differences in the macrophage phenotype were observed between M-CSF-activated WT BMDMs and Duox1−/− BMDMs (online supplementary file 1, figure S3C).

jitc-2020-000622supp003.pdf (251KB, pdf)

jitc-2020-000622supp004.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

Altogether, our results show that DUOX1 is involved in GM-CSF-induced proinflammatory macrophage activation and affects the secretory profile in response to microenvironmental stimuli in vitro.

DUOX1 controls the phagocytotic function of macrophages both in vitro and in vivo

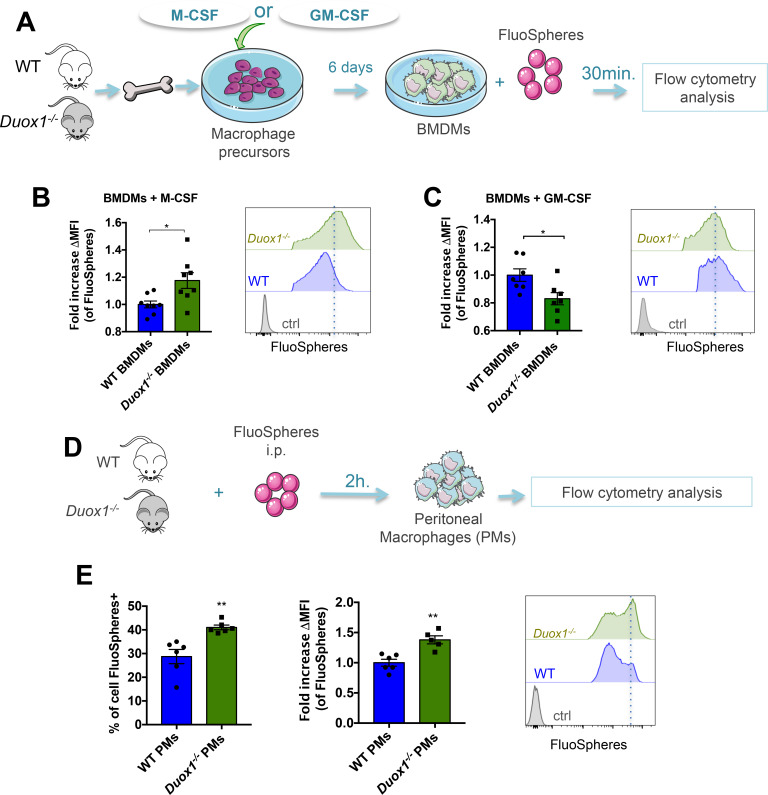

To investigate whether DUOX1 is involved in macrophage phagocytosis, we added fluorescent beads to M-CSF or GM-CSF-differentiated BMDMs for 30 min (figure 2A). Flow cytometry showed that anti-inflammatory Duox1−/− BMDMs performed more phagocytosis than anti-inflammatory WT BMDMs, as demonstrated by their increased uptake of fluorescent beads (figure 2B); in contrast, proinflammatory Duox1−/− BMDMs exhibited lower phagocytotic function than proinflammatory WT BMDMs (figure 2C).

Figure 2.

DUOX1 controls the phagocytotic function of macrophages both in vitro and in vivo. (A) Macrophage precursors from WT or Duox1−/− bone marrow were cultured in the presence of either M-CSF or GM-CSF. After 6 days, fluorescent beads (FluoSpheres) were added to the bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) for 30 min. (B and C, left panels) M-CSF (B) and GM-CSF (C) cultured BMDMs were analyzed by flow cytometry for their ability to take up the FluoSpheres, which is represented as the fold increases in mean fluorescence intensity (∆MFI=MFI of the specific fluorescence of beads−MFI of control (non-treated BMDMs)). The right panels show histograms of FluoSphere− (Ctrl) and FluoSphere+ BMDMs. Data were obtained from two independent experiments and are represented as the mean±SEM. n=7–8, *p<0.05 (Student’s t-test). (D) FluoSpheres were injected intraperitoneally into WT and Duox1−/− mice. (E, left panel) Two hours later, the percentage of peritoneal macrophages (PMs) that had taken up the FluoSpheres was analyzed by flow cytometry. The middle panel represents the uptake capacity of FluoSpheres by PMs, which is represented as the fold increase in the MFI ((∆MFI=MFI of the specific fluorescence of beads−MFI of control (non-treated PMs)). The right panel shows the histograms of FluoSphere+ PMs. Data were obtained from two independent experiments and are represented as the mean±SEM. n=4–6, **p<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

We then confirmed the involvement of DUOX1 in phagocytotic function in vivo by injecting fluorescent beads intraperitoneally into WT and Duox1−/− mice (figure 2D). Flow cytometry analysis showed that compared with WT peritoneal macrophages, Duox1−/− peritoneal macrophages had significantly increased uptake of FluoSpheres (figure 2E). A similar trend was observed in lung macrophages when FluoSpheres were administered intranasally (online supplementary file 1, figure S4A), suggesting that Duox1−/− alveolar and interstitial macrophages (AMs and IMs, respectively) perform more phagocytosis than WT AMs and IMs (online supplementary file 1, figure S4B and S4C).

jitc-2020-000622supp005.pdf (811.1KB, pdf)

DUOX1 decreases the antitumor effect of proinflammatory macrophages

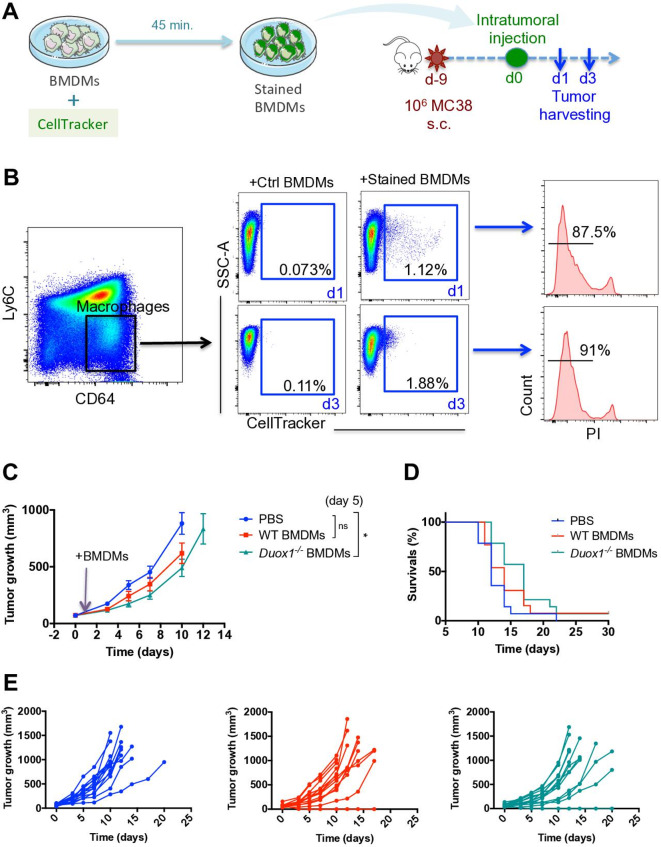

To investigate whether DUOX1 is involved in the antitumor function of proinflammatory macrophages, proinflammatory WT and Duox1−/− BMDMs were injected intratumorally into established MC38 subcutaneous tumors. To differentiate the BMDMs from other tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), we used CellTracker to stain them in vitro (figure 3A). Subcutaneous tumors were analyzed 1 and 3 days after BMDM injection. On both days 1 and 3, BMDMs could still be distinguished from TAMs and were still detectable as live functional cells, as demonstrated by the exclusion of PI (figure 3B). Tumor growth analysis showed that compared with PBS treatment, proinflammatory WT BMDMs induced a slight delay in tumor growth on day 5 post BMDM injection (figure 3C). Interestingly, Duox1−/− BMDMs induced a significant reduction in tumor growth compared with that in PBS-injected mice (figure 3C). At later time points, the growth of tumors injected with either WT or Duox1−/− BMDMs proceeded similarly to that of tumors in other treatment groups, resulting in comparable survival rates among all groups, even though a trend toward improved survival was observed in the Duox1−/− group (figure 3D). In striking contrast, when MC38 tumor cells were injected into WT and Duox1−/− mice, no difference in tumor growth was observed (online supplementary file 1, figure S5A), suggesting that the systemic deletion of DUOX1 does not impact tumor establishment or progression.

Figure 3.

DUOX1 decreases the antitumor effect of proinflammatory macrophages. (A) Macrophage precursors from WT or Duox1−/− bone marrow were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF to induce proinflammatory bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs). After 6 days, CellTracker dye was added to the proinflammatory BMDM culture for 45 min. The stained BMDMs were injected intratumorally into MC38 subcutaneous tumors. (B, left and middle) On days 1 and 3 after intratumoral injection, tumor-associated macrophages were analyzed for CellTracker staining by flow cytometry. (B, right) Histograms of CellTracker+ BMDMs stained with propidium iodide (PI) are shown. (C) Tumor growth was monitored in wild-type (WT) mice treated with PBS, WT proinflammatory BMDMs or Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDMs. (D) The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the treated mice are shown. (E) Tumor growth is shown for individual mice in each treatment group. Data were obtained from three independent experiments and are represented as the mean±SEM. n=13–14, ****p<0.0001 (two-way ANOVA).

jitc-2020-000622supp006.pdf (831.5KB, pdf)

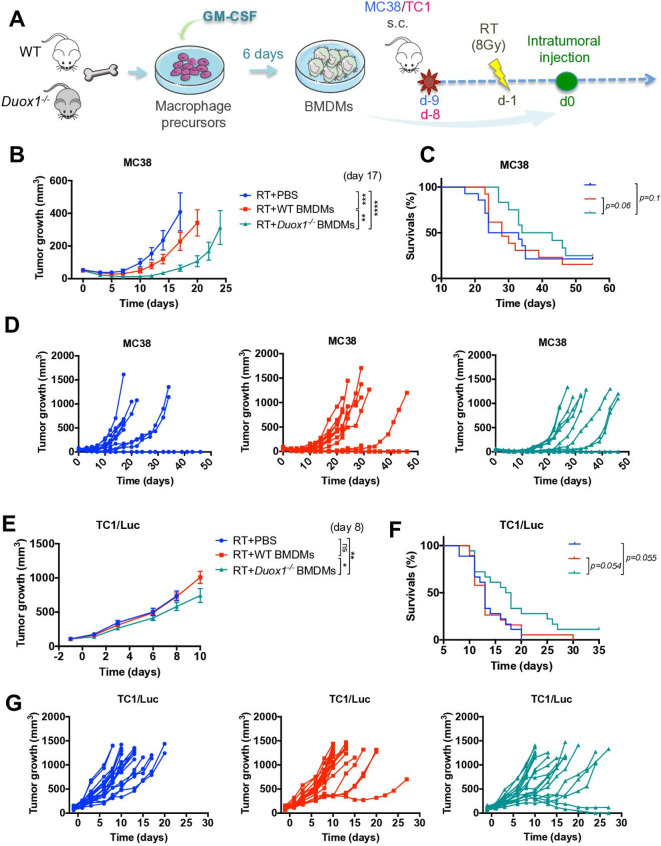

RT enhances the antitumor effect of Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages

Macrophages are key players in the responses of tumors to radiotherapy and exert either antitumor or protumor effects according to their phenotype.15 Subsets of macrophages with an immunosuppressive/anti-inflammatory phenotype can limit the efficacy of RT.16 17 We demonstrated that DUOX1 reduced the proinflammatory properties of macrophages in vitro (figure 1), and we therefore hypothesized that DUOX1 could be involved in macrophage-mediated mechanisms of resistance to RT. To evaluate this hypothesis, MC38 subcutaneous tumors were irradiated at 8 Gy, and 1 day later, WT or Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDMs were injected intratumorally (figure 4A). Compared with control PBS injection, proinflammatory WT BMDM injection into irradiated tumors induced a significant reduction in tumor volume at day 17. Interestingly, proinflammatory Duox1−/− BMDMs exerted an enhanced antitumor effect, and a significant reduction in the tumor volumes was observed at day 17 (when all mice were still alive) compared with those in both PBS-injected mice and BMDM WT-injected mice (figure 4B), and a delay in tumor regrowth was also observed (figure 4D). Furthermore, the injection of Duox1−/− BMDMs but not WT BMDMs improved the survival of irradiated mice compared with that of PBS-injected mice (figure 4C). In contrast, when MC38 tumor cells were injected into WT and Duox1−/− mice, the irradiation of established tumors produced no difference in tumor growth (online supplementary file 1, figure S5B). In order to confirm the Duox1−/− macrophage-mediated antitumor effect, TC1/Luc subcutaneous tumor model was used. Tumors were irradiated at 8 Gy, and 1 day later, WT or Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDMs were injected intratumorally (figure 4A). Compared with control PBS injection, proinflammatory WT BMDM injection into irradiated tumors had no effect in tumor volume, while proinflammatory Duox1−/− BMDMs exerted a significant antitumor effect at day 8 (when all mice were still alive) (figure 4E), and a delay in tumor regrowth was also observed (figure 4G). Furthermore, the injection of Duox1−/− BMDMs improved the survival of irradiated mice compared with that of WT BMDMs and PBS-injected mice (figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Radiotherapy (RT) enhances the antitumor effect of Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages. (A) Macrophage precursors from WT or Duox1−/− bone marrow were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF to induce proinflammatory bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs). After 6 days, the proinflammatory BMDMs were injected intratumorally into MC38 or TC1/Luc subcutaneous tumors 1 day after local tumor irradiation (RT) at 8 Gy. (B and E) Tumor growth in wild-type (WT) mice treated with RT+PBS, RT+WT proinflammatory BMDMs or RT+Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDMs was monitored in MC38 and TC1/Luc tumors, respectively. (C and F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for treated mice are shown in MC38 and TC1/Luc tumors, respectively. (D and G) Tumor growth is shown for individual mice in each treatment group in MC38 and TC1/Luc tumors, respectively. Data were obtained from three independent experiments (MC38 tumor model, n=13–14) or two independent experiments (TC1/Luc tumor model, n=18–19) and are represented as the mean±SEM. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 (two-way ANOVA).

Our data clearly showed an antitumor effect mediated by proinflammatory Duox1−/− BMDMs combined with RT.

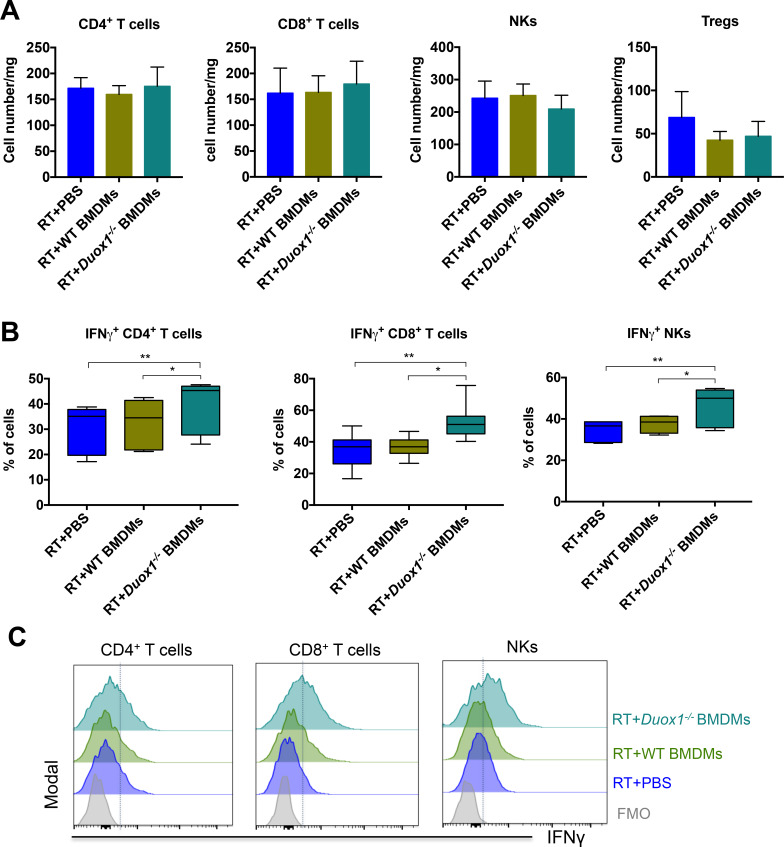

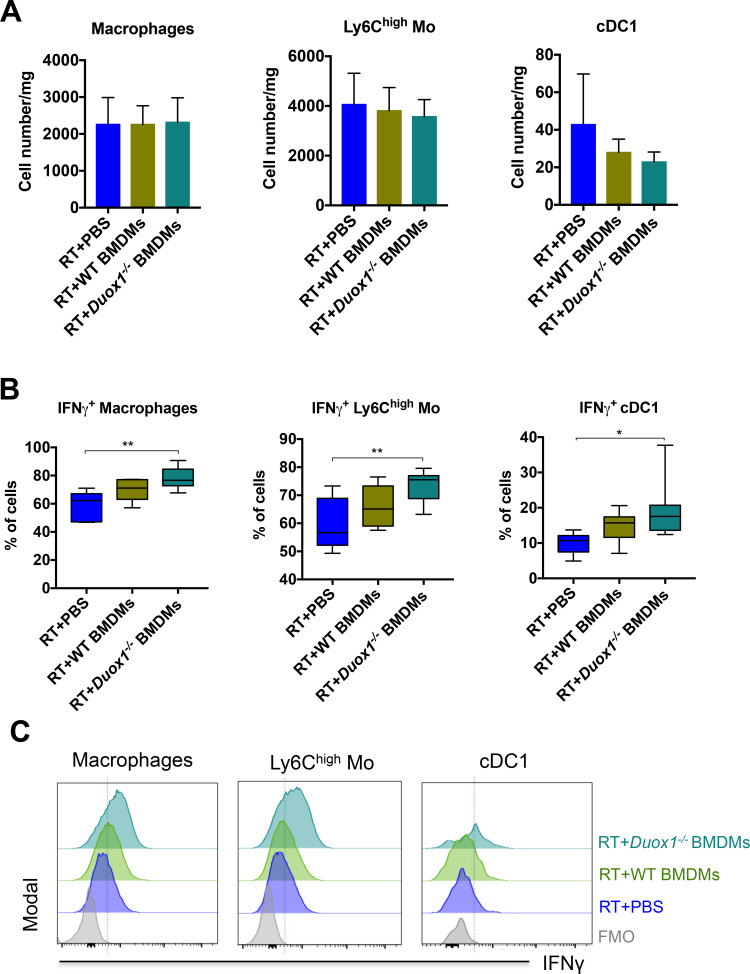

Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages induced IFNγ production by lymphoid and myeloid cells in the irradiated tumor

We performed flow cytometry analysis to characterize the tumor-infiltrating immune cell populations following BMDM injection in order to better understand the role of DUOX1 in macrophages after radiotherapy. Irradiated tumors were collected 3 days after BMDM injection to characterize the early immune response because at this time point, the difference in tumor size among the groups was still homogeneous (figure 4B). Our results showed that Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDMs had no effect on the total numbers of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, NKs or regulatory T cells (Tregs, figure 5A). We observed significant increases in the percentages of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and NKs producing IFNγ in irradiated tumors injected with Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDMs compared with the other treatment groups (figure 5B). Furthermore, myeloid cell analysis showed that the total numbers of macrophages, inflammatory monocytes (Ly6high Mo) and type 1 conventional dendritic cells (cDC1) were not affected regardless of the treatment approach (figure 6A). However, the percentages of macrophages, Ly6Chigh Mo and cDC1 producing IFNγ were increased in the tumors treated with the Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDMs post RT compared with those given the other treatments (figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages induce IFNγ production by lymphoid cells in irradiated tumors. Three days after bone marrow–derived macrophage (BMDM) injection, the tumors were harvested, and lymphoid immune cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) The numbers of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, natural killers (NKs) and Tregs are presented for each treated group. (B) The percentages of IFNγ+ tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and NKs are shown. (C) Representative histograms of IFNγ+ tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and NKs are shown. Data were obtained from two independent experiments and are represented as the mean±SEM. n=7–8, *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (two-way ANOVA).

Figure 6.

Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages induce IFNγ production by myeloid cells in irradiated tumors. Three days after bone marrow–derived macrophage (BMDM) injection, the tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) The numbers of tumor-infiltrating macrophages, Ly6high Mo and cDC1 are shown. (B) The percentages of IFNγ+ tumor-infiltrating macrophages, Ly6high Mo and cDC1 are presented for each treatment group. (C) Representative histograms of IFNγ+ tumor-infiltrating macrophages, Ly6high Mo and cDC1 are shown. Data were obtained from two independent experiments and are represented as the mean±SEM. n=7–8, *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (two-way ANOVA).

We analyzed the membrane expression of the inhibitory coreceptors cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen (CTLA) 4 and programmed cell death (PD)−1 on lymphoid cells at the indicated time (3 days post BMDM injection), and we showed that, in contrast to WT proinflammatory BMDMs, Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDMs post RT induced a decrease in CTLA4 expression on Tregs, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and NKs (online supplementary file 1, figure S6A). Further, Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDM injection post RT induced a trend toward decreased expression levels of PD-1 on Tregs compared with WT proinflammatory BMDM injection (online supplementary file 1, figure S6B).

jitc-2020-000622supp007.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

Subsequently, we performed cytokine profiling of tumors 3 days after BMDM injection and showed increasing trends in the IFNγ levels in tumor tissue receiving RT plus Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDMs (online supplementary file 1, figure S7). No differences were observed in the levels of type 2 T helper (Th2) cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-13.

jitc-2020-000622supp008.pdf (411.5KB, pdf)

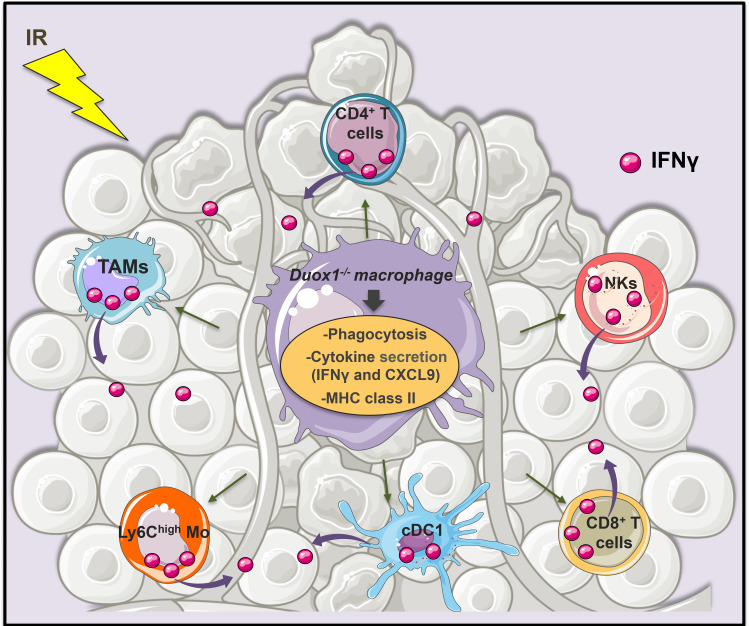

Taken together, our results suggest that DUOX1 inhibition could be a new target to induce IFNγ production after tumor irradiation (figure 7).

Figure 7.

DUOX1 involvement in the IFNγ-associated antitumor effect of macrophages post radiotherapy. DUOX1 deficiency increased the production of proinflammatory cytokines (such as IFNγ and CXCL9) and the membrane expression of MHC-II by activated macrophages in vitro. DUOX1 was also involved in the phagocytotic function of macrophages. Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophage injection into irradiated tumors promotes lymphoid and myeloid cell activation and IFNγ production, leading to an efficient antitumor response.

Discussion

Here, we describe for the first time the involvement of DUOX1, one of the main oxidant-generating enzymes, in macrophage activation, secretion and antitumor function, highlighting a role for oxidative burst in immune system activation during tumor development. Our main findings can be summarized as follows: (1) DUOX1 impacts two important functions in macrophages: phagocytosis and cytokine secretion; (2) DUOX1 enhances MHC class II membrane expression in macrophages; (3) DUOX1 deletion in macrophages improves their antitumor function and ameliorates the tumor response to RT; (4) the transfer of Duox1−/− macrophages post RT enhances IFNγ production by tumor-infiltrating myeloid and lymphoid immune cells.

The involvement of oxidative burst in both immune system activation and tumor development has already been described,3 18 but the roles of DUOX1 in these processes are poorly understood. In innate immunity, oxidative burst products (ROS) play pivotal roles in host defense and homeostasis. For example, superoxide (O2−·) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are used by professional phagocytic cells to eliminate pathogens.3 O2−· is produced by NOXs 1–5, but H2O2 is produced by DUOX proteins, which were initially identified in the thyroid gland as the main source of H2O2.4 Accordingly, our results showed that DUOX1 deletion in macrophages significantly decreased macrophage production of H2O2. DUOX1 has been previously shown to be expressed in human macrophages.10 Accordingly, our results showed that DUOX1 was also expressed in macrophage infiltrating human lung tissue previously exposed to ionizing radiation. Even though the staining intensity was elevated in these areas, the limited amount of human material available prevented us from evaluating if DUOX1 expression was actually upregulated by ionizing radiation in patients. Such analyses deserve attention and are planned for work with larger cohorts.

The role of DUOX1 in immune cells has been previously reported,10 11 19 but it remains poorly understood. Interestingly, our results showed for the first time that DUOX1 was involved in the phagocytotic function of macrophages. Furthermore, our results demonstrated that Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages enhanced the membrane expression of MHC class II, suggesting that Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages show enhanced activity as antigen-presenting cells and increase the priming of T cells. However, Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages also decrease their phagocytotic functioning in vitro and increased their secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ. Interestingly, IFNγ has been reported to suppress phagocytosis in proinflammatory macrophages20 and to upregulate MHC class II expression in macrophages.21 Furthermore, IFNγ is known to promote the antitumor effect of RT.22 Accordingly, our data showed a trend toward increased levels of IFNγ in tumor treated with RT and Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages. In addition, our data showed that Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages increased the secretion of CXCL9, which is a chemokine that promotes the migration of tumor-infiltrating T cells to cDC1-enriched areas to facilitate T-cell priming.23 Further, our results demonstrated that the percentage of IFNγ-producing cDC1, which are key orchestrators of the immune response through T cell priming,24 25 was increased in tumors injected with Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages. Since T cells are known to be recruited to irradiated MC38 tumors,26 the intratumoral injection of Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDMs could thus favor T-cell priming and contribute to the observed improvement in the tumor response to RT. In agreement with the improved activation of T cells, the IFNγ-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were increased in tumors injected with Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages post RT. Furthermore, our results showed a decreased expression levels of CTLA4, an inhibitory costimulatory molecule,24 on lymphoid cells in irradiated tumors treated with Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages, suggesting an increase in the potency of T cells.

DUOX1 deletion in proinflammatory macrophages improved the antitumor effect of these cells, but intratumoral injection of Duox1−/− proinflammatory BMDMs alone was not sufficient to increase the survival rate of mice, likely because the lifespan of injected BMDMs is limited and the amplitude of their effect on tumor growth was not sufficient to drive durable responses. Irradiation of the tumor bed before Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophage injection into the tumor induced a significant delay in tumor growth and also an improved survival rate, suggesting that the higher amplitude of the antitumor effect induced by this combined treatment resulted in a prolonged antitumor response. This induced antitumor effect could be sustained by the increased IFNγ production by lymphoid (CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and NKs) and myeloid cells (macrophages, Ly6Chigh Mo and cDC1).

The role of DUOX1 in cancers is controversial, and several previous studies reported that DUOX1 involvement in cancers depends on the tumor tissue or cell type.9 27–29 Our results demonstrated that in contrast to experiments performed by transferring macrophages, those involving the subcutaneous injection of MC38 cells into WT and Duox1−/− mice showed no difference in tumor progression between the two mouse strains, suggesting that systemic deletion of DUOX1 had no clear antitumor effect. This discrepancy could be explained by different roles for DUOX1 in tumor macrophages versus other cell types. Interestingly, it has been reported that DUOX1 activation seems to be important for enhancing and sustaining further TCR signaling in T cells,11 suggesting that the systemic deletion of DUOX1 could decrease the activation of tumor-infiltrating T cells. These data indicate that systemic targeting of DUOX1, as would occur with the use of non-cell type-targeted inhibitors, does not represent a promising approach. Tissue/cell-specific targeting of DUOX1, such as the use of liposome-based formulations, could constitute an alternative strategy. Specific reprogramming of TAMs through DUOX1 targeting could indeed be a novel and promising antitumor strategy that could synergize with the known effects of RT.1

It appears counterintuitive to inhibit oxidative stress to boost the efficacy of RT, as it is well known that free oxygen radicals are mediators of DNA damage induced by irradiation and represent the basic mechanism by which RT eliminates tumor cells.30 However, the excessive and long-term activation of proteins contributing to oxidative stress, such as DUOX1, leads to an imbalance in the redox system equilibrium, which subsequently induces tissue, cell toxicities and biological disorders.4 30

Conclusion

In summary, our study identifies novel roles for DUOX1, one of the main oxidant-generating enzymes, in macrophage activation, polarization and antitumor function. Duox1−/− proinflammatory macrophages enhance the efficacy of RT, and this antitumor effect is associated with IFNγ production by local lymphoid and myeloid cell subsets. Our work sheds new light on the role of a component of the oxidative system, namely, DUOX1, in the antitumor immune response and indicates that DUOX1 is a potential target for reprogramming TAMs toward an antitumor phenotype to improve the efficacy of RT.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the Institut National du Cancer (INCA 2014-1-PL-BIO-03). The authors thank Patrick Gonin, Karine Ser-Le Roux, Mathieu Ayassamy, Mélanie Polrot (PFEP platform), Olivia Bawa, Hélène Rocheteau (PETRA platform), Yann Lecluse, Philippe Rameau and Cyril Catelain (PFIC platform) at Gustave Roussy for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. Author names Winchygn Liu and Ruy A Louzada were incorrectly spelt as Wincgygn Liu and Ruy Andrade Louzada. Additionally, the orcid ID for Ruy A Louzada was added.

Contributors: LM designed the study, performed the experiments, analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. MGDT performed experiments, PH performed experiments and reviewed the manuscript, and SB performed experiments. RAL, CC, RC and WL provided technical support. CD provided the Duox1−/− mice and reviewed the manuscript. MM supervised the study and wrote the manuscript. ED supervised the study and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by funds from the Institut National du Cancer (INCA 2014-1-PL-BIO-03).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. All free text entered below will be published.

References

- 1.Klug F, Prakash H, Huber PE, et al. . Low-dose irradiation programs macrophage differentiation to an iNOS+/M1 phenotype that orchestrates effective T cell immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2013;24:589–602. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meziani L, Mondini M, Petit B, et al. . Csf1R inhibition prevents radiation pulmonary fibrosis by depletion of interstitial macrophages. Eur Respir J 2018;51:1–3. 10.1183/13993003.02120-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rada B, Leto TL. Oxidative innate immune defenses by Nox/Duox family NADPH oxidases. Contrib Microbiol 2008;15:164–87. 10.1159/000136357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ameziane-El-Hassani R, Schlumberger M, Dupuy C. NADPH oxidases: new actors in thyroid cancer? Nat Rev Endocrinol 2016;12:485–94. 10.1038/nrendo.2016.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Q, Allouch A, Paoletti A, et al. . NOX2-dependent ATM kinase activation dictates pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype and improves effectiveness to radiation therapy. Cell Death Differ 2017;24:1632–44. 10.1038/cdd.2017.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Q, Choksi S, Qu J, et al. . NADPH oxidases are essential for macrophage differentiation. J Biol Chem 2016;291:20030–41. 10.1074/jbc.M116.731216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forteza R, Salathe M, Miot F, et al. . Regulated hydrogen peroxide production by Duox in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;32:462–9. 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0302OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little AC, Hristova M, van Lith L, et al. . Dysregulated redox regulation contributes to nuclear EGFR localization and pathogenicity in lung cancer. Sci Rep 2019;9:4844. 10.1038/s41598-019-41395-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ameziane-El-Hassani R, Talbot M, de Souza Dos Santos MC, et al. . NADPH oxidase DUOX1 promotes long-term persistence of oxidative stress after an exposure to irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:5051–6. 10.1073/pnas.1420707112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rada B, Park JJ, Sil P, et al. . NLRP3 inflammasome activation and interleukin-1β release in macrophages require calcium but are independent of calcium-activated NADPH oxidases. Inflamm Res 2014;63:821–30. 10.1007/s00011-014-0756-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon J, Shatynski KE, Chen H, et al. . The nonphagocytic NADPH oxidase DUOX1 mediates a positive feedback loop during T cell receptor signaling. Sci Signal 2010;3:ra59. 10.1126/scisignal.2000976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donkó A, Ruisanchez E, Orient A, et al. . Urothelial cells produce hydrogen peroxide through the activation of DUOX1. Free Radic Biol Med 2010;49:2040–8. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Overmeire E, Stijlemans B, Heymann F, et al. . M-CSF and GM-CSF receptor signaling differentially regulate monocyte maturation and macrophage polarization in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res 2016;76:35–42. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valledor AF, Hsu L-C, Ogawa S, et al. . Activation of liver X receptors and retinoid X receptors prevents bacterial-induced macrophage apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:17813–8. 10.1073/pnas.0407749101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meziani L, Deutsch E, Mondini M. Macrophages in radiation injury: a new therapeutic target. Oncoimmunology 2018;7:e1494488. 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1494488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mondini M, Loyher P-L, Hamon P, et al. . CCR2-dependent recruitment of Tregs and monocytes following radiotherapy is associated with TNFα-mediated resistance. Cancer Immunol Res 2019;7:376–87. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu J, Escamilla J, Mok S, et al. . CSF1R signaling blockade stanches tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells and improves the efficacy of radiotherapy in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2013;73:2782–94. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szatrowski TP, Nathan CF. Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer Res 1991;51:794–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Oliveira S, López-Muñoz A, Candel S, et al. . ATP modulates acute inflammation in vivo through dual oxidase 1-derived H2O2 production and NF-κB activation. J Immunol 2014;192:5710–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.1302902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarique AA, Logan J, Thomas E, et al. . Phenotypic, functional, and plasticity features of classical and alternatively activated human macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2015;53:676–88. 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0012OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giroux M, Schmidt M, Descoteaux A. IFN-γ-induced MHC class II expression: transactivation of class II transactivator promoter IV by IFN regulatory factor-1 is regulated by protein kinase C-α. J Immunol 2003;171:4187–94. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mills BN, Connolly KA, Ye J, et al. . Stereotactic body radiation and interleukin-12 combination therapy eradicates pancreatic tumors by repolarizing the immune microenvironment. Cell Rep 2019;29:406–21. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kastenmüller W, Brandes M, Wang Z, et al. . Peripheral prepositioning and local CXCL9 chemokine-mediated guidance orchestrate rapid memory CD8+ T cell responses in the lymph node. Immunity 2013;38:502–13. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engelhardt JJ, Boldajipour B, Beemiller P, et al. . Marginating dendritic cells of the tumor microenvironment cross-present tumor antigens and stably engage tumor-specific T cells. Cancer Cell 2012;21:402–17. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, et al. . The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu Rev Immunol 2013;31:563–604. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones KI, Tiersma J, Yuzhalin AE, et al. . Radiation combined with macrophage depletion promotes adaptive immunity and potentiates checkpoint blockade. EMBO Mol Med 2018;10:e9342. 10.15252/emmm.201809342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luxen S, Belinsky SA, Knaus UG. Silencing of DUOX NADPH oxidases by promoter hypermethylation in lung cancer. Cancer Res 2008;68:1037–45. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ling Q, Shi W, Huang C, et al. . Epigenetic silencing of dual oxidase 1 by promoter hypermethylation in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res 2014;4:508–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho SY, Kim S, Son M-J, et al. . Dual oxidase 1 and NADPH oxidase 2 exert favorable effects in cervical cancer patients by activating immune response. BMC Cancer 2019;19:1078. 10.1186/s12885-019-6202-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montay-Gruel P, Meziani L, Yakkala C, et al. . Expanding the therapeutic index of radiation therapy by normal tissue protection. Br J Radiol 2019;92:20180008. 10.1259/bjr.20180008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2020-000622supp001.pdf (109.2KB, pdf)

jitc-2020-000622supp002.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

jitc-2020-000622supp003.pdf (251KB, pdf)

jitc-2020-000622supp004.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

jitc-2020-000622supp005.pdf (811.1KB, pdf)

jitc-2020-000622supp006.pdf (831.5KB, pdf)

jitc-2020-000622supp007.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

jitc-2020-000622supp008.pdf (411.5KB, pdf)