Abstract

Background: We conducted a multicenter, randomized trial of early integrated palliative and oncology care in patients with advanced cancer to confirm the benefits of early palliative care (PC) seen in prior single-center studies.

Methods: We randomly assigned patients with newly diagnosed incurable cancer to early integrated palliative and oncology care (n = 195) or usual oncology care (n = 196) at sites through the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. Patients assigned to the intervention were expected to meet with a PC clinician at least monthly until death, whereas usual care patients consulted PC on request. The primary endpoint was the change in quality of life from baseline to week 12 per the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G). Secondary outcomes included anxiety, depression, and communication about prognosis and end-of-life care.

Results: Due to significant morbidity and a high proportion of measures that were not completed within the protocol window or for unknown reasons, the rate of missing data was high. We anticipated that 70% of patients (n = 280) would complete the FACT-G at baseline and week 12, but only 49.3% (n = 193/391) completed the measure. Delivery of the intervention was also suboptimal, as 14.9% (n = 29/195) of intervention patients had no PC visits by week 12. Intervention patients reported a mean 3.35 (standard deviation [SD] = 14.7) increase in FACT-G scores from baseline to week 12 compared with usual care patients who reported a 0.12 (SD = 12.7) increase from baseline (p = 0.10).

Conclusion: This study highlights the difficulties of conducting multicenter trials of supportive care interventions in patients with advanced cancer. Clinical Trials Registration: NCT02349412.

Keywords: cancer, palliative care, quality of life

Introduction

Multiple randomized trials have demonstrated a wide range of benefits with early involvement of palliative care (PC) for patients with serious cancers.1–10 The majority of trials in patients with cancer have demonstrated improvements in patients' quality of life (QOL) with early involvement of PC.1–7,9 Additional reported benefits of early PC for patients include reduced symptom burden, fewer depression symptoms, greater utilization of hospice services, and enhanced communication about end-of-life (EOL) care.1–4,9,11 A meta-analysis concluded that PC was associated with improvements in QOL and symptom burden for patients with serious illnesses, including cancer.12 However, this meta-analysis and several prior reviews noted substantial heterogeneity in the methodological quality and rigor of many trials.12–14

The challenges of conducting PC trials in patients with serious illnesses have been well documented in the literature, including the inability to blind participants and study staff to group assignment as well as the high rates of participant attrition and missing data due to progressive disease and death.12,13,15 In addition to these methodical challenges, the delivery and practice of PC across clinical sites varies significantly.16,17 Studies published to date have included a range of delivery models, such as consultative or integrated PC, with substantial variation in the nature, timing, and duration of PC involvement.16 Lastly, most PC trials in patients with cancer have been conducted as single-site trials, limiting the generalizability of study findings.

Addressing the limitations of prior research, we conducted a multicenter, randomized trial of an early integrated palliative and oncology care model in patients with advanced lung and noncolorectal gastrointestinal (GI) cancer. To ensure the generalizability of study findings, we utilized an intervention manual and included both academic hospitals and community-based sites. The primary aim of this study was to confirm the improvements in QOL with early PC for patients with advanced cancer.

Methods

Study design

We enrolled patients with newly diagnosed, incurable cancer from National Cancer Institute (NCI) Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology (“Alliance”) community and academic sites in a nonblinded, randomized trial of early PC integrated with oncology care versus usual oncology care. Sites interested in participating completed a questionnaire and interview with the study lead PC clinician (V.J.) to select sites that were sufficiently integrated with oncology and had adequate staffing to comply with study procedures. Based on the questionnaires and interviews, we selected nine academic and nine community sites (including NCI Community Oncology Research Program [NCORP] minority/underserved community sites). The study protocol was IRB approved by the participating sites, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Participants

Patients were eligible if they were within eight weeks of diagnosis of incurable lung (nonsmall cell, small cell, or mesothelioma) or noncolorectal GI (pancreatic, esophageal, gastric, hepatobiliary, or unknown GI primary) cancer. Patients were required to receive their care at a participating site, be at least 18 years old, have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 to 2, and be able to read and respond to questions in English. Oncology clinicians identified eligible patients who were not receiving treatment with curative intent and invited them to participate. Consented patients were asked if they had a family member or friend who planned to accompany them to visits to participate as a caregiver in the trial. Patients without a caregiver were eligible for the trial.

Participating sites were required to have PC clinics with at least six months of experience providing care in the outpatient oncology setting, be led by a board-certified PC physician or advanced practice nurse (APN), and have the capacity to perform PC visits at the cancer practice on the same day as patients' oncology visits. At least one member of the PC team was required to complete a web-based training on the early integrated PC model, review the intervention manual, and train other clinicians at their site.

Random assignment

Patients were randomly assigned to study group in a 1:1 fashion, stratified by cancer type and participation of a caregiver, using the Oncology Patient Enrollment Network and the Pocock and Simon dynamic allocation procedure.18

Study procedures

The evidence-based PC practice model was detailed in the intervention manual that was included in the protocol.19–21 The manual outlined the content and timing of following domains of early PC across the illness trajectory: developing and maintaining the therapeutic relationship with patients and caregivers; assessing and treating patients' symptoms; providing support and reinforcement of coping with advanced cancer in patients and caregivers; assessing and enhancing prognostic awareness and illness understanding in patients and caregivers; assisting with treatment decision making; and planning for EOL care.

The study protocol stated that patients assigned to early PC should meet with a PC physician or APN in the cancer center within four weeks of enrollment and at least monthly until death, in conjunction with patients' scheduled oncology visits. If an in-person visit was not possible, the PC clinician was permitted to contact the patient via telephone. A member of the PC team was required to see patients who were hospitalized.

Patients assigned to usual oncology care were able to meet with a PC clinician on request by the oncologist, patient, or caregiver.

Outcome measures

We measured QOL with the 27-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G), which assesses physical, functional, emotional, and social well-being in the past week. Higher scores indicate better QOL.22 We assessed patients' mood with the 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which consists of two subscales assessing anxiety and depression symptoms in the past week.23 Subscale scores range from 0 (no distress) to 21 (maximum distress). We used the Prognosis and Treatment Perceptions Questionnaire to measure patients' understanding of their prognosis and report of their communication with oncologists.24 This measure includes 13 items assessing patients' information preferences, perception of their prognosis, and communication about their prognosis and EOL care. Caregiver outcomes will be presented in a separate publication.

Data collection

As per Alliance procedures, patients were to complete a demographic questionnaire and baseline self-report measures after study registration. Study measures were to be administered in-person, via telephone, or by mail at baseline and then at weeks 6, 12, and 24. The protocol permitted a window of two weeks before or after each time point for completion of measures. Study staff were not blinded to the study arm.

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical analysis by using SAS Version 9.4M3. Data obtained through May 5, 2018 were included. The primary outcome was the change in FACT-G from baseline to week 12. A change of at least four to five points on the FACT-G is considered clinically meaningful.25 We estimated that with 280 patients, the study would have 80% power to detect a four-point difference in the change in FACT-G scores from baseline to week 12 (standard deviation [SD] = 11.87) with a two-sided alpha of 5%. Based on previous studies, we estimated a missing data rate of 20–30% so we increased our sample size to 400 patients.1,2 Data collection and statistical analyses were conducted by the Alliance Statistics and Data Center.

We first conducted available case analyses using analysis of covariance models controlling for baseline criterion scores to compare changes in QOL and mood between groups from baseline to week 12 and 24. We used Fisher's exact test and chi-square tests to compare responses on the Prognosis and Treatment Perceptions Questionnaire. Our protocol also included a plan for utilizing pattern mixture models to account for missing data. However, the rates of missing data at weeks 12 and 24 were 50.6% and 62.1%, respectively, and such modeling techniques provide unreliable and potentially biased estimates when >50% of the data are missing.26,27 This concern is particularly relevant in PC studies, as outcome data are often not missing at random, but due to disease progression and death.28 We, therefore, present only available case analyses, without the use of imputation methods to account for missing data.

Results

Study conduct

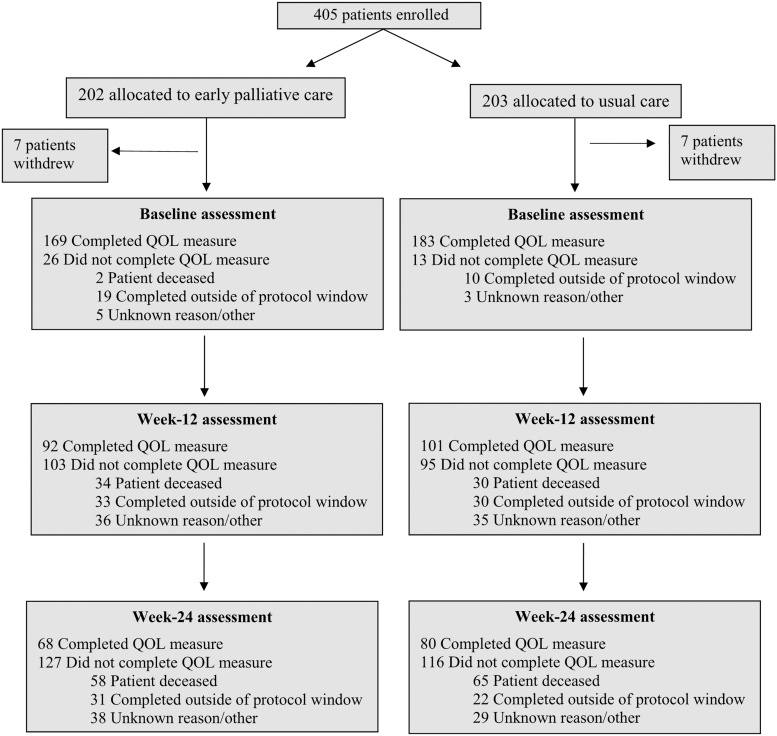

Sites enrolled 405 patients between June 25, 2015 and April 10, 2017 (Fig. 1). Supplementary Table S1 includes the number of patients enrolled at each site in an anonymized fashion. We do not have data on the number of eligible patients seen at the participating institutions during the enrollment period given that clinicians identified and enrolled patients without documenting the number of potentially eligible participants. Of 405 registered patients, 14 withdrew from the study after providing written informed consent. Slightly less than half of the patients (49.3%, n = 193/391) completed the primary outcome measure at baseline and at week 12, with the majority of missing data due to either data collected outside of the protocol window or unknown reasons (34.3%, n = 134/391) or death (16.4%, n = 64/391). Only 37.8% (n = 148/391) of patients completed the primary outcome measure at both baseline and week 24 with 30.7% (n = 120/391) of missing data due to either data collected outside of the protocol window or unknown reasons and 31.5% (n = 123/391) due to death. There was substantial variation in the proportion of patients included in the analysis cohort and the proportion of patients who were deceased by study site at each time point, as shown in Supplementary Table S2.

FIG. 1.

Consort diagram. The term “completed outside of protocol window” refers to measures that were completed outside of the four-week data collection period. The term “unknown reason” was attributed for missing data with no explanation on the study case report form. QoL, quality of life.

Participant characteristics

Study participants had a mean age of 65.2 years and more than half were male (Table 1). The majority had lung cancer. Most participants had an ECOG PS of 1, and a greater number of patients with ECOG PS 2 were assigned to the early PC study group. The median survival was 10.0 (95% confidence interval: 8.7–11.5) months.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Variable | Early palliative care (N = 195), Mean (SD) or n (%) | Usual care (N = 196), Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.5 (9.4) | 65.0 (10.7) |

| Male Gender | 114 (58.5%) | 107 (54.6%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 148 (75.9%) | 155 (79.1%) |

| Black | 24 (12.3%) | 22 (11.2%) |

| Unknown | 12 (6.2%) | 9 (4.6%) |

| Asian | 9 (4.6%) | 6 (3.1%) |

| American Indian | 2 (1.0%) | 2 (1.0%) |

| Native Hawaiian | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.0%) |

| Hispanic/Latino Ethnicity | 8 (4.1%) | 6 (3.1%) |

| Religion | ||

| Catholic | 61 (31.3%) | 62 (31.6%) |

| Other | 45 (23.1%) | 49 (25.0%) |

| Protestant | 48 (24.6%) | 44 (22.4%) |

| None | 10 (5.1%) | 18 (9.2%) |

| Jewish | 10 (5.1%) | 10 (5.1%) |

| Muslim | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Missing | 20 (10.3%) | 12 (6.1%) |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married/partner | 120 (61.6%) | 116 (59.2%) |

| Divorced/separated | 31 (15.9%) | 31 (15.8%) |

| Widowed | 18 (9.2%) | 24 (12.2%) |

| Single | 16 (8.2%) | 18 (9.2%) |

| Missing | 10 (5.1%) | 7 (3.5%) |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 73 (37.4%) | 81 (41.4%) |

| Some or completed college | 79 (40.5%) | 72 (36.7%) |

| Graduate school | 30 (15.4%) | 31 (15.8%) |

| Missing | 13 (6.6%) | 12 (6.1%) |

| Cancer type | ||

| Lung | 118 (60.5%) | 116 (59.2%) |

| Esophageal/gastroesophageal junction/gastric | 15 (7.7%) | 18 (9.2%) |

| Hepatic/biliary/pancreatic/unknown primary | 62 (31.8%) | 62 (31.6%) |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 47 (24.1%) | 41 (20.9%) |

| 1 | 108 (55.4%) | 127 (64.8%) |

| 2 | 40 (20.5%) | 28 (14.3%) |

| Participating caregiver | 134 (68.7%) | 136 (69.4%) |

| FACT-G | 73.6 (15.8) | 74.0 (17.0) |

| HADS depression subscale | 5.4 (4.2) | 5.8 (4.2) |

| HADS anxiety subscale | 7.2 (3.3) | 7.2 (3.7) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SD, standard deviation.

Intervention delivery

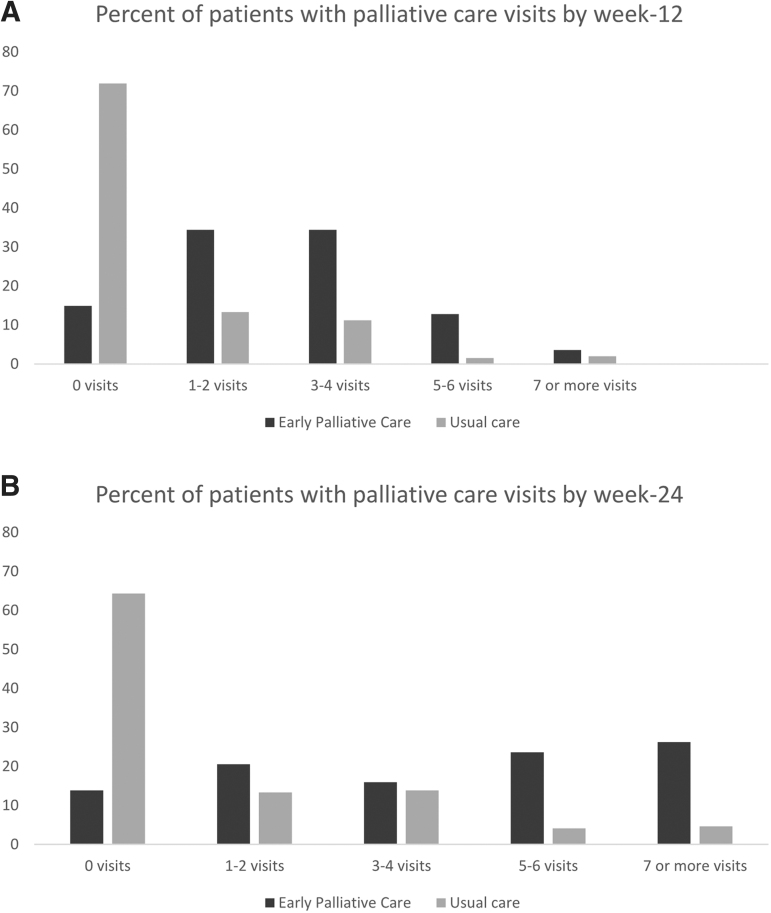

The mean number of PC visits for patients assigned to early PC was 2.8 (range 0–18) by 12 weeks and 4.4 (range 0–18) by 24 weeks. Figure 2 depicts the number of PC visits by study group at 12 and 24 weeks. By week 12, 14.9% (n = 29/195) of patients assigned to early PC had no visits. By 24 weeks, patients assigned to the intervention were expected to have participated in a minimum of five PC visits per the study protocol. However, in the subset of early PC patients who were alive at 24 weeks, only 66.4% (n = 75/113) had participated in at least five visits with a PC clinician. There was substantial variation in intervention delivery by study site, as shown in Supplementary Table S3. Of the usual care patients who were alive at each time point, 22.7% (n = 35/154) and 25.9% (n = 30/116) had a PC visit by week 12 and 24, respectively.

FIG. 2.

PC delivery. (A) Percent of patients with PC visits by week-12. Bars represent the percent of patients in each study group according to the number of PC visits within 12 weeks of study participation. (B) Percent of patients with PC visits by week 24. Bars represent the percent of patients in each study group according to the number of PC visits within 24 weeks of study participation. PC, palliative care.

QOL and mood

Patients assigned to early PC reported a mean 3.35-point improvement in FACT-G scores from baseline to 12 weeks compared with usual care patients who reported a 0.12-point increase (Table 2). At 24 weeks, patients assigned to early PC reported a 3.80-point improvement in FACT-G scores from baseline whereas usual care patients reported a 0.69-point increase (Table 3). These changes were not significantly different between groups at either time point. Similarly, the changes in HADS depression scores from baseline to weeks 12 and 24 did not differ between study groups (Tables 2 and 3). However, patients assigned to early PC reported a mean 1.13-point decrease in HADS anxiety scores from baseline to 12 weeks compared with usual care patients who reported a 0.32-point decrease from baseline (p = 0.03) (Table 2). Although the decrease in HADS anxiety scores from baseline to 24 weeks was larger in patients assigned to early PC compared with usual care patients, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.06; Table 3).

Table 2.

Intervention Effects on Change in Outcomes from Baseline to Week 12

| Early palliative care |

Usual care |

Mean difference between groups (95% CI) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean change from baseline (SD) | N | Mean change from baseline (SD) | |||

| FACT-G | 92 | 3.35 (14.7) | 101 | 0.12 (12.7) | 3.23 (−0.67 to 7.13) | 0.10 |

| HADS-Depression | 100 | 0.54 (4.0) | 112 | 0.46 (3.6) | 0.08 (−0.94 to 2.09) | 0.88 |

| HADS-Anxiety | 100 | −1.13 (2.7) | 111 | −0.32 (2.8) | −0.81 (−1.54 to −0.07) | 0.03 |

CI, confidence interval.

Table 3.

Intervention Effects on Change in Outcomes from Baseline to Week 24

| Early palliative care |

Usual care |

Mean difference between groups (95% CI) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean change from baseline (SD) | N | Mean change from baseline (SD) | |||

| FACT-G | 68 | 3.80 (15.3) | 80 | 0.69 (13.3) | 3.12 (−1.54 to 7.77) | 0.19 |

| HADS-Depression | 75 | 0.37 (3.8) | 84 | 0.26 (3.6) | 0.11 (−1.04 to 1.27) | 0.85 |

| HADS-Anxiety | 75 | −1.23 (3.5) | 84 | −0.21 (3.3) | −1.01 (−2.07 to 0.05) | 0.06 |

Only participants with available data on the individual study measure at baseline and 12 or 24 weeks were included.

Prognostic understanding and communication about EOL care

Due to the degree of missing data at week 24, we examined prognostic understanding and communication only at week 12. Study groups did not differ in patients' information preferences and satisfaction with communication (Table 4). However, patients assigned to early PC were more likely to have discussed their wishes about the care they would want to receive if they were dying compared with those who received usual care (30.3% vs. 14.5% p = 0.006).

Table 4.

Intervention Effects on Prognostic Understanding and Communication About End-of-Life Care at Week 12

| Early palliative care | Usual care | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is your preference for details of information about your diagnosis and treatment? | N = 102 | N = 110 | 0.61 |

| I prefer not to hear a lot of details | 7 (6.9%) | 7 (6.4%) | |

| I want to hear details only in certain situation, such as when tests are abnormal or when treatment decisions need to be made | 25 (24.5%) | 21 (19.1%) | |

| I want to hear as many details as possible in all situations related to my cancer and its treatment | 70 (68.6%) | 82 (74.5%) | |

| How do you feel about the amount of information you know about your prognosis? | N = 101 | N = 112 | 0.64 |

| I wish I had more information about my prognosis | 29 (28.7%) | 30 (26.8%) | |

| I now have about the right information | 71 (70.3%) | 79 (70.5%) | |

| I wish I had less information about my prognosis | 1 (1.0%) | 3 (2.7%) | |

| How helpful has knowing about prognosis been for you? | N = 87 | N = 99 | 0.60 |

| Extremely helpful | 42 (48.3%) | 44 (44.4%) | |

| Not at all to very helpful | 45 (51.7%) | 55 (55.6%) | |

| How likely do you think it is that you will be cured of your cancer? | N = 98 | N = 110 | 0.08 |

| No chance (0% chance) | 18 (18.4%) | 11 (10.0%) | |

| Very unlikely (less than 10%) to extremely likely (more than 90%) | 80 (81.6%) | 99 (90.0%) | |

| Have you and your oncologist discussed any particular wishes you have about the care you would want to receive if you were dying? | N = 99 | N = 110 | 0.006 |

| Yes | 30 (30.3%) | 16 (14.5%) | |

| No | 69 (69.7%) | 94 (85.5%) |

Discussion

As the first multicenter, randomized PC trial through an NCI National Clinical Trials Network group, this study underscores the challenges of conducting PC research in seriously ill patients. Although the study design and methods were based on well-conducted single-site randomized trials, both the degree of morbidity in the study sample and difficulties with data collection led to substantial methodological limitations. This trial failed to meet the primary endpoint of demonstrating improvements in QOL with early PC. However, the estimated sample size did not account for the high morbidity in the sample and degree of missing data; thus, the trial was underpowered to demonstrate a difference in the primary outcome. Importantly, these findings highlight the difficulties in implementing supportive care interventions and collecting participant-reported data in patients with advanced cancer.

Prior studies of early PC interventions utilized systematic approaches, such as medical record review or tumor boards, to ensure all potentially eligible patients were identified for study participation.1–3 Our study protocol did not stipulate comprehensive screening procedures and relied on oncologists to identify eligible patients. We anticipated that oncologists would offer study participation to the majority of patients who met the eligibility criteria. However, the characteristics of the study cohort and variation in survival across study sites suggest that some clinicians were more likely to offer the study to patients who they perceived needed early PC. Specifically, the study cohort was slightly older, had worse baseline QOL, depression, and anxiety scores, and shorter survival than prior studies.2,4 Thus, the study cohort was not representative of patients with advanced lung and GI cancer due to the lack of a systematic approach to identify participants, which likely introduced selection bias in the sample. Systematic approaches for identifying and enrolling patients in supportive care trials, including having research staff approach patients for study participation, may minimize the burden on oncology clinicians and ensure a more generalizable study sample, but this requires significant clinical trial infrastructure and trained study staff.

A significant limitation of this trial was the high rate of missing patient-reported measures. As noted earlier, we observed a higher than anticipated mortality rate, which contributed to the degree of missing data. Nonetheless, the majority of the missing data was due either to data collected outside of the protocol window or for unknown reasons. We also observed substantial variation in data collection across study sites. In studies of patients with advanced cancers, it is necessary to define and adhere to time points for the collection of measures such as QOL, as these outcomes worsen over time as a patient's illness progresses.28 A high proportion of the missing data in this trial was due to the measures being collected outside of the protocol-defined window, suggesting that it was difficult for the clinical trial staff to collect participant-reported measures within these time frames. The combination of attrition due to death and missing data at weeks 12 and 24 led to only 49% and 38% of the study sample being assessed at these time points, respectively. The extent of missing data in this multicenter trial is substantially greater than what has been reported in prior single-center trials, with the majority of studies including primary outcome data on at least 70% of study participants at 12 weeks.2–5,8

Thus, multicenter trials of supportive care interventions in which patient-reported measures are the primary study endpoints require systematic procedures to ensure rigorous collection of these essential outcomes. Dedicated clinical staff and use of electronic methods to collect data may minimize missing patient-reported data.29,30

We also experienced difficulties with the implementation of the PC intervention. According to the study protocol, patients assigned to early PC should have met with a PC clinician at least monthly throughout their illness. However, 15% of patients had no PC visits by 12 weeks, with 14% having no visits by 24 weeks. Although some patients who did not have a PC visit may have died, this attrition is unlikely to account for all patients who had no visits. In our recent single-center trial in the same patient population, the mean number of PC visits by 24 weeks was 6.5, in contrast to the mean of 4.4 visits reported in the current trial.4 Therefore, intervention delivery was less robust than planned and highlights the challenges of scheduling monthly PC visits over the course of a patient's lifetime. This study underscores the need for dedicated clinical trial infrastructure to conduct PC studies successfully. Future multicenter PC trials should consider the use of telehealth to minimize burden on clinical trial staff, and potentially patients, and maximize intervention delivery.

Due to the high rate of missing data, this trial did not have adequate power to detect a significant difference in patient QOL at 12 weeks. In addition, recent studies have suggested that the 12-week time point is too early to observe QOL differences in an advanced cancer population.3,4 Although we aimed at examining patient-reported outcomes at 24 weeks as a secondary endpoint, the available case data at this time point were insufficient to detect differences between groups. Given the extent of missing data, we could not conduct the planned analysis by using pattern mixture modeling, as this approach would provide an unreliable and potentially biased estimate.26,27 In addition, both the less robust intervention delivery for patients assigned to early PC and the use of PC among patients assigned to usual care may have impacted our ability to detect differences between study groups. Notably, we did find differences in anxiety symptoms and communication about EOL care preferences favoring the early PC study group. However, due to the study limitations, these results should be reproduced in a more rigorously conducted clinical trial with a cluster randomized design to minimize contamination.

As the evidence-base grows, multisite trials represent an exciting opportunity to learn about the benefits of PC for diverse patients in a variety of clinical settings. However, as our trial demonstrates, well-designed studies can fail in execution, making interpretation of findings difficult. Successful implementation of PC research requires well-defined study procedures to identify and recruit eligible study participants, administer participant-reported measures, and monitor intervention delivery. Future studies should consider a hybrid efficacy-implementation design to enable greater understanding of barriers and facilitators to intervention delivery and data collection.

Supplementary Material

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding Information

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UG1CA189823 (Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology NCORP Grant), U10CA180836, U10CA180857, U10CA180867, and UG1CA189863.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.K.: CompleteCare, Vivtex, Amorsa Therapuetics; A.K.: Acclivity Health, Prepped Health; M.R.: Merck; E.J.R.: Helsinn, BASF, Napo, American Imaging Mangement, Imuneering, Heron; C.L.: PledPharma, Disarm Therapeutics, Asahi Kasei, and Metys Pharmaceuticals; Others: none.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. : Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:834–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vanbutsele G, Pardon K, Van Belle S, et al. : Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:394–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall'Agata M, et al. : Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: Results from a multicentre, randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer 2016;65:61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, et al. : Emergency department-initiated palliative care in advanced cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:591–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. : Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1438–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al. : Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;316:2094–2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jordhoy MS, Fayers P, Saltnes T, et al. : A palliative-care intervention and death at home: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2000;356:888–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. : Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:394–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. : Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016;316:2104–2114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, et al. : Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: A systematic review. JAMA 2008;299:1698–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Temel JS: Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? A review of the evidence. J Support Oncol 2011;9: 87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jordhoy MS, Kaasa S, Fayers P, et al. : Challenges in palliative care research; recruitment, attrition and compliance: Experience from a randomized controlled trial. Palliat Med 1999;13:299–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hui D, Bruera E: Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:159–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith AK, Thai JN, Bakitas MA, et al. : The diverse landscape of palliative care clinics. J Palliat Med 2013;16:661–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pocock SJ, Simon R: Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics 1975;31:103–115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jacobsen J, Jackson V, Dahlin C, et al. : Components of early outpatient palliative care consultation in patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med 2011;14:459–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoerger M, Greer JA, Jackson VA, et al. : Defining the elements of early palliative care that are associated with patient-reported outcomes and the delivery of end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1096–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Back AL, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. : Clinician roles in early integrated palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A qualitative study. J Palliat Med 2014;17:1244–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. : The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:570–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP: The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1983;67:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Park ER, et al. : Associations among prognostic understanding, quality of life, and mood in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 2014;120:278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cella D, Hahn EA, Dineen K: Meaningful change in cancer-specific quality of life scores: Differences between improvement and worsening. Qual Life Res 2002;11:207–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schlomer GL, Bauman S, Card NA: Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. J Couns Psychol 2010;57:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rubin DB: Introduction in Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li Z, Tosteson TD, Bakitas MA: Joint modeling quality of life and survival using a terminal decline model in palliative care studies. Stat Med 2013;32:1394–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Basch E, Dueck AC, Rogak LJ, et al. : Feasibility of implementing the patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events in a multicenter trial: NCCTG N1048. J Clin Oncol 2018:JCO2018788620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Denis F, Lethrosne C, Pourel N, et al. : Randomized trial comparing a web-mediated follow-up with routine surveillance in lung cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.