Abstract

Aim.

Previous studies suggest that Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Children (MBCT-C) is feasible and may improve anxiety and emotion regulation in youth with anxiety disorders at-risk for bipolar disorder. However, controlled studies are warranted to replicate and extend these findings.

Methods.

In the current study, 24 youth with anxiety disorders who have at least one parent with bipolar disorder participated in a MBCT-C treatment period (n = 24; Mage = 13.6, 75% girls, 79% White) with a subset also participating in a prior psychoeducation waitlist control period (n = 19 Mage = 13.8, 68% girls, 84% White). Participants in both the waitlist and MBCT-C periods completed independently-rated symptom scales at each time point. Participants in the waitlist period received educational materials 12 weeks prior to the beginning of MBCT-C.

Results.

There were significantly greater improvements in overall clinical severity in the MBCT-C period compared to the waitlist period, but not in clinician- and child-rated anxiety, emotion regulation or mindfulness. However, increases in mindfulness were associated with improvements in anxiety and emotion regulation in the MBCT-C period, but not the waitlist period.

Conclusions.

Findings suggest that MBCT-C may be effective for improving overall clinical severity in youth with anxiety disorders who are at-risk for bipolar disorder. However, waitlist controlled designs may inflate effect sizes so interpret with caution. Larger studies utilizing prospective randomized controlled designs are warranted.

Keywords: anxiety, bipolar disorder, MBCT-C, mindfulness, youth

Introduction

Child and adolescent offspring of parents with bipolar disorder have an increased risk for developing bipolar disorder compared to age-matched peers, with rates ranging from 15 to 33% in some studies (Chang, Steiner, & Ketter, 2000; Henin et al., 2005). In addition, these at-risk youth exhibit poor emotion regulation and higher rates of psychopathology, particularly anxiety disorders, in early childhood and adolescence, which further increases the risk for the later development of bipolar disorder (Chang et al., 2000; Geller, Zimerman, Williams, Bolhofner, & Craney, 2001; Henin et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2007). Complicating the clinical picture even further, antidepressants are commonly used to treat anxiety disorders in youth (Connolly and Bernstein 2007; Strawn et al. 2012), but may accelerate the onset of mania (Reichart & Nolen, 2004) and are poorly tolerated in “at-risk” youth (Strawn et al. 2014). Thus, it is critical to identify psychosocial interventions aimed at bolstering self-regulation and adaptive coping skills in order to reduce anxiety and possible forestall the development of bipolar disorder in these at-risk youth (Hawke, Provencher, & Arntz, 2011).

One such method that shows promise is Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), a skills-based intervention that integrates mindfulness training with cognitive-behavioral theory (Segal, Teasdale, & Williams, 2004). The fundamental component of MBCT is mindfulness, defined as present moment awareness with an attitude of openness and nonjudgment (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Mindfulness involves relating to internal experiences, such as thoughts and emotions, as transient mental events as opposed to threatening experiences that warrant avoidance or other maladaptive responses (Sears, Tirch, & Denton, 2011). Mindfulness skills (e.g., acceptance, nonjudgmental awareness) have been shown to improve emotion regulation processes associated with psychopathology (e.g., worry, rumination), resulting in reduced depressive and anxiety symptoms in clinical and non-clinical populations (Chiesa & Serretti, 2011; Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, 2010; Kuyken, Crane, & Dalgleish, 2012; Piet & Hougaard, 2011; Segal et al., 2004; Teasdale et al., 2000).

Adapted directly from MBCT, Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Children (MBCT-C) is a 12-week manualized group therapy designed to promote mindfulness skills in children ages 8–12 (Semple & Lee, 2011). MBCT-C fosters present-moment awareness of thoughts, emotions and bodily sensations by allowing children to ‘-drop into-’ their senses (e.g., hearing, touch), and encourages them to notice rather than struggle with thoughts and emotions (Semple & Lee, 2011). In contrast to traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), rather than challenging the content of thoughts, MBCT-C aims to help children change their relationship to thoughts, emotions and bodily sensations (Sears, 2015). Through a variety of mindfulness exercises (e.g., body scan, breathing exercises), children begin to recognize the transient nature of thoughts and emotions, and as a result, develop the freedom to consciously choose adaptive responses, rather than engaging in automatic and habitual maladaptive behaviors that serve to perpetuate negative emotional states (Hayes, Follete, & Linehan, 2004; Sears, 2015).

MBCT-C has been shown to improve anxiety, inattention and emotional dysregulation in non-clinical samples (Lee, Semple, Rosa, & Miller, 2008; Semple, Lee, Rose, & Miller, 2010; Semple, 2005, 2010). However, few research studies, to date, have examined the effects of MBCT-C among clinical populations. In order to address this gap, our research group recently examined the effects of MBCT-C among ten youth (ages 9–16) with anxiety disorders who were at risk for bipolar disorder (Cotton et al., 2015). In addition to high levels of feasibility, acceptability and usefulness, MBCT-C was associated with improvements in both clinician- and youth-rated anxiety and parent-rated emotional regulation. Moreover, improvements in mindfulness were associated with decreases in clinician- and youth-rated anxiety symptoms, suggesting that changes in mindfulness may serve as an explanatory mechanism for improved anxiety symptoms in this group. We also found that MBCT-C was associated with increased activation in brain structures (i.e., bilateral insula, lentiform nucleus, thalamus, and left anterior cingulate) that promote interoception and processing of internal stimuli while viewing emotional stimuli, and that these activation changes were correlated with decreases in anxiety (Strawn et al., 2016).

Despite promising findings, the lack of a control group in these studies precludes our ability to reliably conclude that these improvements were due to specific treatment effects as opposed to nonspecific treatment factors. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to extend previous work (Cotton et al., 2015) by comparing the effects of MBCT-C vs. a psychoeducational waitlist control on symptoms of anxiety, emotion regulation, mindfulness and overall clinical severity in a sample of youth with an anxiety disorder who have a familial risk of bipolar disorder. We hypothesized that, compared to the waitlist period, subjects during the MBCT-C period would exhibit greater improvements in clinician- and child-rated anxiety, emotion regulation, mindfulness and clinical severity. Furthermore, we hypothesized that improved anxiety, emotion regulation and clinical severity would be significantly associated with increases in mindfulness during the MBCT-C period but not the waitlist period.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 24 youth recruited from an ongoing study cohort of individuals at risk for bipolar disorder (NIMH CIDAR grant #: 1 P50 MH077138 01A1), and from community practitioners (see Table 1 for sample demographics). Participants were included by: 1) being 9–18 years old; 2) having at least one biological parent with bipolar I disorder; 3) meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, or panic disorder as determined by the Washington University Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U KSADS; Geller, Zimerman, Williams, Bolhofner, Craney, et al., 2001); 4) having a Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS; Research Units of Pediatric Psychopharmacology [RUPP], 2002) five item scale score ≥10 at screening and baseline; 5) being fluent in English; and 6) agreeing to participate in at least 75% of sessions. Participants were excluded by: 1) a previously documented intellectual disability; 2) previously participating in any mindfulness-based treatment; 3) having a substance use disorder other than nicotine or caffeine in the past 3 months; 4) judged clinically to be at suicidal risk as defined as having active suicidal ideation, intent, plan, or serious attempt within the past 30 days, or a baseline Children’s Depression Rating Scale (CDRS; Poznanski, Cook, & Carroll, 1979; Poznanski, Cook, Carroll, & Corzo, 1983) suicide item score >3; 5) concurrent treatment with psychotropic medication, with the exception that concurrent antidepressants and/or ADHD medications would be permitted only if no medication adjustments were made during the 30 days prior to screening or were anticipated during the course of the study; 6) initiating psychotherapy within 2 months prior to screening or planning to initiate psychotherapy during study participation. Adolescents who presented with a current anxiety disorder despite longer-term psychotherapy (i.e., >2 months) were included since they were still exhibiting active symptoms. For participants who entered the study in psychotherapy, type and frequency of therapy remained constant during the study; 7) any lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder (mania, hypomania, or bipolar not otherwise specified), cyclothymia, schizophrenia, or another psychotic disorder; 8) symptoms that required admission to an inpatient psychiatric unit, as determined by a study clinician; or 9) anxiety symptoms resulting from acute medical illness or acute intoxication or withdrawal from drugs or alcohol as determined by medical evaluation or symptom resolution.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics

| Variable | Waitlist Sample | MBCT Sample |

|---|---|---|

| Total Enrolled | 19 | 24 |

| Sex, n (%), girls | 13(68) | 18(75) |

| Age, n (%) | ||

| 9 | 2(11) | 2(8) |

| 10 | 2(11) | 3(13) |

| 11 | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| 12 | 2(11) | 2(8) |

| 13 | 1(5) | 2(8) |

| 14 | 2(11) | 5(21) |

| 15 | 5(26) | 5(21) |

| 16 | 1(5) | 1(4) |

| 17 | 3(16) | 3(13) |

| 18 | 1(5) | 1(4) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 16(84) | 19(79) |

| Anxiety Disorders,a n (%) | ||

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 18(95) | 22(92) |

| Social Anxiety Disorders | 5(26) | 9(38) |

| Separation Anxiety | 3(16) | 3(13) |

| Specific Phobias | 3(16) | 3(13) |

| Panic Disorder with Agoraphobia | 1(5) | 1(4) |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 1(5) | 1(4) |

| Concomitant medications, n (%) | ||

| Stimulant | 3(16) | 5(21) |

| Antidepressant | 8(42) | 10(42) |

| Supplementb | 3(16) | 5(21) |

| Concomitant psychotherapy, n (%) | 6(32) | 8(33) |

Note.

Some participants had multiple anxiety diagnoses

Supplements included melatonin, omega-3, vitamin D, iron, and magnesium. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding. The 19 in the waitlist period are the same participants in the MBCT period, plus an additional 5 participants that did not complete the waitlist period.

Measures

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV present/lifetime (SCID-P/L) was administered by clinicians with diagnostic reliability (diagnostic kappa > .9) to determine a parental diagnosis of bipolar disorder. At baseline, the WASH-U KSADS (Geller et al., 2001) was administered to determine presence of a current anxiety disorder in youth and the PARS (RUPP, 2002) was used for anxiety symptom severity. Eligible participants completed the following measures during waitlist and MBCT-C treatment periods:

State-Trait Anxiety Index (STAI; Southam-Gerow, Flannery-Schroeder, & Kendall, 2003). The STAI is a measure of youth-rated trait (STAI-T) and state (STAI-S) anxiety.

Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS; RUPP, 2002) is a measure of clinician-rated anxiety and anxiety-related functional impairment and was completed by clinicians with established interrater reliability.”

Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields & Cicchetti, 1995). The ERC is a 24-item measure of parental perceptions of their child’s lability/negativity (e.g., “exhibits wide mood swings”) and ability to regulate emotions (e.g., “can modulate excitement in emotionally arousing situations”), with higher scores reflecting greater ability to regulate emotions.

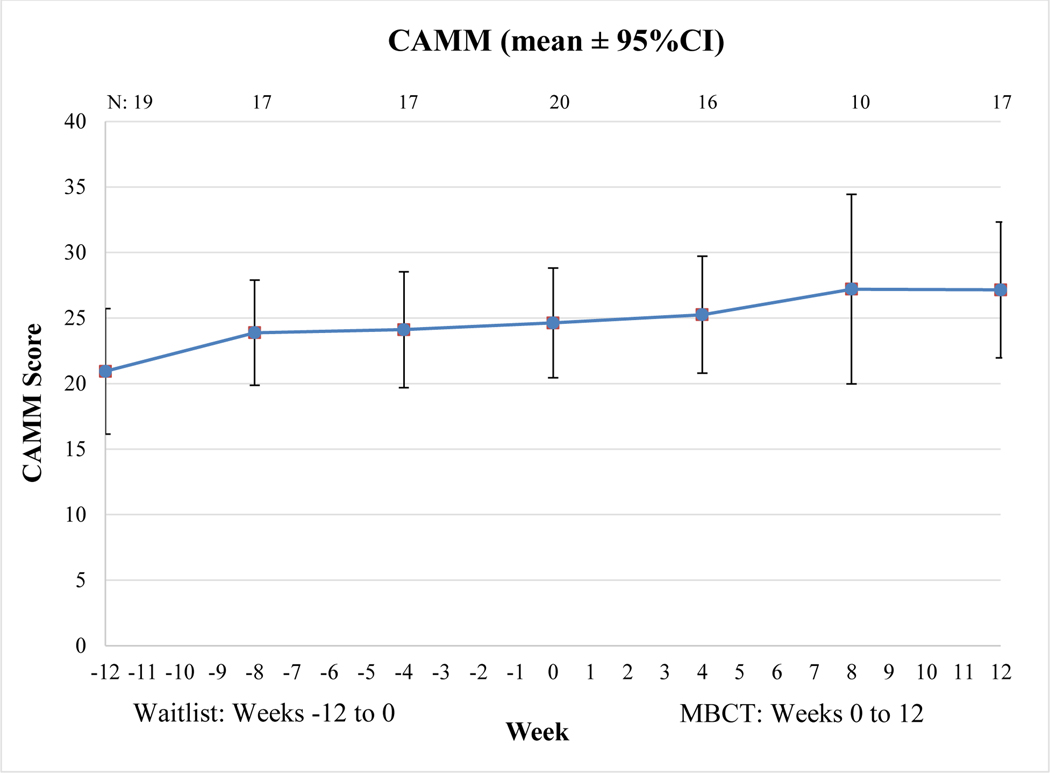

Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM; Greco, Baer, & Smith, 2011). The CAMM is a 10-item measure of youth-rated mindfulness. The CAMM assesses present moment awareness (e.g. “At school, I walk from class to class without noticing what I’m doing”) and nonjudgmental awareness (e.g., “I tell myself that I shouldn’t feel the way I’m feeling”). Higher scores reflect higher levels of mindfulness.

Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI; Guy, 1976). The CGI is a measure of clinician-rated overall illness severity. Clinicians rate the severity of illness on a 7-point scale (1 = normal, not at all ill to 7 = among the most extremely ill), taking all information into account, including the participant’s history, symptoms, and functioning. The CGI was completed by either a psychiatrist or clinical research professionals with interrater reliability and experience with the rating scales being administered.

The STAI-S, PARS, and CGI were completed at baseline, weeks 4, 8, and 12 in the waitlist period, and weekly in the MBCT-C treatment period. The ERC and CAMM were completed at baseline, and weeks 4, 8, and 12 in waitlist and treatment periods. The STAI-T was administered at baseline and week 12 of waitlist and MBCT-C treatment periods.

Procedure

After risks, benefits and alternatives to study procedures were explained, the child and their parent or guardian provided assent and written informed consent, respectively. Methods and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board. Participants in the MBCT-C treatment period were enrolled into one of four groups based on their time of enrollment and age to account for age-appropriate differences in language and teaching methods and were therefore not randomly assigned. Three of these four groups participated in the waitlist period. The age range and sample size of the four groups were: Group 1, 10–14 yrs., n = 5; Group 2, 15–18 yrs., n = 7; Group 3, 9–12 yrs., n = 6; Group 4, 13–17 yrs., n = 6. The first group did not participate in the waitlist period due to time constraints for completing the study. Indeed, by allowing this first group to skip the waitlist period, we were able to start two groups concurrently at the beginning of the study (see Figure 1 for participant flow diagram).

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Diagram

Note. Participants were discontinued after being lost to follow-up (n=2), withdrawing consent (n=4), and reporting an adverse event (n=1; hospitalization). Reasons for screen failure included concomitant medication (n = 2), exclusionary family history (n = 1), diagnosis of bipolar disorder NOS (n = 1), and lost to follow-up prior to enrollment (n = 3).

MBCT-C Intervention Group (MBCT-C).

The 12 weekly, 75-minute MBCT-C group sessions were facilitated by two masters-level therapists, each with training in MBCT-C. Though MBCT-C was designed for youth ages 8–12, we included youth up to age 18 to reflect the patient population in our outpatient clinic. Given that there was no existing manualized mindfulness-based intervention for youth ages 13–18 at the time of this study, we made minor adaptations to the protocol to explain the concepts in developmentally appropriate language (i.e., for youth 13–18; Semple & Lee, 2011). Ongoing supervision for the facilitators was provided by a clinical psychologist and expert in mindfulness, including MBCT (RWS).

Psychoeducation Waitlist Control Group.

Nineteen of the 24 study participants participated in a 12-week waitlist period in which they received psychoeducational materials prior to participation in the active MBCT-C treatment protocol. During the 12-week period, participants attended baseline and weeks 4, 8, and 12 visits and completed identical ratings to those completed during the MBCT-C intervention period. At each study visit during the 12-week period, participants and families received educational materials from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2008) about mood and anxiety disorders in youth, bipolar disorders, familial risk for bipolar disorder, and treatment strategies for anxiety and depression in youth. For those youth who participated in the waitlist period, week 12 ratings served as baseline ratings for the MBCT-C treatment period.

Data Analysis

Frequencies and descriptive statistics were examined for all variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were used to compare change in outcome measures between MBCT period and waitlist period using all available data. In these models, the only factor was week, which included all waitlist and MBCT time points. The mean difference of interest was the difference in the change scores from the waitlist and MBCT periods (i.e., MBCT [week 12 – week 0] – waitlist [week 12 – week 0]). Demographic variables were not considered as covariates in the models as waitlist and MBCT-C samples consisted of mostly similar subjects and, thus, were balanced on these variables (e.g., mean age waitlist period = 13.8; mean age MBCT-C period = 13.7). Also, for exploratory purposes, models were used to examine the changes in all outcome measures within each period. The models included correlated error terms to allow for repeated measures design. A repeated measures regression analysis was considered, but our hypothesis of different responses in the waitlist and MBCT-C periods (i.e., different slopes for a fitted regression line) would violate the linearity assumption of the regression model. Effect sizes were calculated using the t-statistic and degrees of freedom [(effect size = 2 x t-statistic/square root (degrees of freedom)]. Pearson correlations were used to examine associations between changes from baseline to endpoint in mindfulness (CAMM) and other outcome variables in both waitlist and MBCT periods. All statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level of 0.05 and performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary,NC).

Results

See Table 2 for ANOVA and within period t-test results. See Figures 2 and 3 for a graphical representation of mean clinician-rated anxiety (PARS) and mindfulness (CAMM) scores, respectively, over the course of waitlist and MBCT-C treatment periods.

Table 2.

Within and Between Period Changes in Anxiety, Emotion Regulation, Mindfulness and Clinical Severity in the Waitlist and Treatment Periods

| Variable | Baseline M (± SD) † | Endpoint M (±SD) † | Within period p-value | Within period effect size | Between period change (95% CI) ‡ | Between period effect size | Between period p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician-rated anxiety (PARS) | |||||||

| Waitlist | 12.1±4.5 | 9.6±4.4 | 0.12 | −.23 | −1.6 (−7.3, 4.0) | −0.08 | 0.56 |

| MBCT-C | 9.6±4.4 | 5.6±5.7 | 0.01 | −.36 | |||

| Child-rated state anxiety (STAI) | |||||||

| Waitlist | 34.4±7.1 | 34.1±6.9 | 0.89 | −.02 | 0.7 (−7.2, 8.6) | 0.03 | 0.86 |

| MBCT-C | 34.1±6.9 | 34.6±9.0 | 0.87 | .02 | |||

| Child-rated trait anxiety (STAI) | |||||||

| Waitlist | 40.8±9.7 | 37.8±10.2 | 0.10 | −.62 | −2.7 (−8.4, 2.9) | −0.36 | 0.32 |

| MBCT-C | 37.8±10.2 | 31.2±10.2 | <0.01 | −1.19 | |||

| Emotional lability (ERC) | |||||||

| Waitlist | 31.8±6.2 | 29.7±6.6 | 0.45 | −.17 | −0.9 (−7.8, 6.1) | −0.06 | 0.81 |

| MBCT-C | 29.7±6.6 | 28.5±6.1 | 0.34 | −.22 | |||

| Emotion regulation (ERC) | |||||||

| Waitlist | 23.8±4.7 | 24.3±4.6 | 0.61 | .12 | −1.0 (−6.0, 4.0) | −0.09 | 0.69 |

| MBCT-C | 24.3±4.6 | 23.8±5.3 | 0.85 | −.04 | |||

| Mindfulness (CAMM) | |||||||

| Waitlist | 20.9±9.9 | 24.6±9.0 | <0.01 | .58 | −1.9 (−7.9, 4.1) | −0.13 | 0.54 |

| MBCT-C | 24.6±9.0 | 27.2±10.1 | 0.39 | .19 | |||

| Clinical global severity (CGI-S) | |||||||

| Waitlist | 3.3±.8.0 | 3.4±1.0 | 0.92 | −.01 | −1.0 (−2.1, 0.0) | −0.29 | 0.05 |

| MBCT-C | 3.4±1.0 | 2.3±1.2 | <0.01 | −.44 | |||

Note.

Endpoint in the waitlist period = baseline in the MBCT-C period.

MBCT-C (week 12 - week 0) - Waitlist (week 12- week 0); negative values indicate greater reductions in MBCT-C period as compared to the Waitlist period. PARS: Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; ERC: Emotion Regulation Checklist; CAMM: Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure; CGI-S: Clinical Global Impression-Severity.

Figure 2.

Mean PARS Scores in Waitlist and Treatment Periods

Figure 3.

Mean CAMM Scores in Waitlist and Treatment Periods

There was a significant difference between the waitlist and MBCT-C periods in terms of improvement in overall clinical severity (CGI-S; p = .05), with the MBCT-C period showing a greater reduction in CGI-S rating. Contrary to our hypothesis, there were no significant differences between waitlist and MBCT-C periods for clinician- and child-rated anxiety, emotion regulation or mindfulness. Within period change for all outcomes were examined for exploratory purposes. There was a significant improvement in clinician-rated anxiety during the MBCT-C period (p = .01) but not the waitlist period (p = .12) and a significant improvement in child-rated trait anxiety during the MBCT-C period (p < .01) but not during the waitlist period (p = .10), though these changes were not significant between periods. There was a significant difference in clinical severity within the MBCT-C period (p < .01), but not within the waitlist period (p = .92). Of note, there was significant improvement in mindfulness in the waitlist period (p < .01), but not the MBCT-C period (p = .39), though there was no significant difference between periods. Changes in mindfulness were significantly associated with changes in child-rated state anxiety (r = −.51, p = .04), child-rated trait anxiety (r = −.75, p < .01) and emotion regulation (r = .57, p = .03) in the MBCT-C period but not the waitlist period.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to replicate and extend previous work (Cotton et al., 2015) by examining the effects of MBCT-C on anxiety symptoms, emotion regulation, mindfulness and global clinical severity among youth with anxiety disorders at-risk for bipolar disorder with the addition of a psychoeducational waitlist control period for comparison. Consistent with prediction, youth in MBCT-C period demonstrated greater improvements in overall clinical severity than during the waitlist period. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to demonstrate that MBCT-C is associated with decreases in global symptom severity in a clinical population, which is particularly noteworthy given that overall clinical severity has been shown to be associated with disorder-specific symptoms, overall well-being and quality of life across a wide-range of adult and child populations (e.g., Bandelow, Baldwin, Dolberg, Anderson & Stein, 2006).

Inconsistent with prediction, however, the MBCT-C treatment period did not significantly differ from the waitlist period in terms of changes in clinician- and child-rated anxiety, emotion regulation or mindfulness. Importantly, participants did demonstrate clinically meaningful improvements over the course of the entire 24-week period of the clinical trial, from time of waitlist entry to time of study completion. This may be due to the fact that youth with psychopathology experience a sense of relief by simply being enrolled in a clinical trial involving contact with clinicians/researchers (Finniss, Kaptchuk, Miller & Benedetti, 2010), and that regular attention given with routine assessments, even during the waitlist period, oftentimes results in a noticeable level of improvement (Arrindell, 2001). Participants in the waitlist period also received psychoeducational materials, which may have resulted in symptom improvement prior to initiating MBCT-C. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that waitlist controls may themselves inflate effect sizes and exaggerate potential benefits – potentially even acting as nocebos (Furukawa et al. 2014). In addition, because most participants in the MBCT-C period also completed the waitlist period, ceiling effects following the waitlist period may have precluded the ability to detect meaningful changes for some outcomes in the MBCT-C period. This finding may also be due, in part, to the relatively small sample size in the current study, limiting our power to detect meaningful differences across waitlist and MBCT-C groups. On the contrary, MBCT-C may simply not be effective for improving anxiety symptoms and emotion regulation in this at-risk group. Future work should employ more rigorously controlled designs to further examine the efficacy of MBCT-C in this population.

Notably, when changes were examined within each period for exploratory purposes, there were significant improvements in mindfulness within the waitlist period but not the MBCT-C period, though this improvement was not significantly different between periods. This may be partially explained whereby children in the waitlist period were asked to rate their symptoms each week and were also provided with weekly educational material regarding symptomatology, thereby increasing attention towards internal experiences. Therefore, improvements in mindfulness in the waitlist period may have resulted in little room for improvement in the MBCT-C period (i.e., ceiling effect). However, when examining the correlations between changes in mindfulness and changes in all outcomes, improvements in mindfulness were associated with improvements in anxiety and emotion regulation in the MBCT-C period but not the waitlist period. This suggests that paying attention to internal experiences in a nonjudgmental manner, as modeled in MBCT-C, as opposed to paying attention without this attitudinal component (as children were asked to do in the waitlist period), may be necessary for symptom improvement.

While this is the first known controlled trial of MBCT in pediatric patients with anxiety disorders who are at risk for developing bipolar disorder, there are limitations. First, the inherent limitations of waitlist designs are salient and need to caution interpretations, particularly the evidence that waitlist designs may exaggerate potential benefits. Furthermore, participants were not randomized, and there may be clinical benefit in simply knowing that the treatment period is forthcoming in waitlist designs. Moreover, in order to maximize our sample size due to limited time, and to provide treatment to all participants, a majority of the participants in the waitlist period also completed the MBCT-C treatment period. Indeed, most participants completed both the waitlist and MBCT-C treatment periods, which may have resulted in ceiling effects for some outcomes prior to initiating the MBCT-C treatment period. Therefore, future work should employ more rigorous study designs (e.g., RCTs) in order to reliably examine the efficacy of MBCT-C. Second, the current sample was relatively homogenous regarding demographics, limiting the generalizability of findings and primary versus secondary outcomes were not specified as the study was more exploratory in nature. Third, the small sample size likely limited our ability to detect significant differences across waitlist and treatment groups. Fourth, patients with mild anxiety symptoms (i.e., PARS score ≥10) were enrolled in this study relative to other studies of psychotherapy in anxious youth (Walkup et al. 2008) wherein PARS scores >15 are generally required for study entry. This may have decreased the likelihood of “response” (Ginsburg et al. 2011) during both waitlist and treatment periods. Fifth, raters for the clinician administered measures were not blinded to condition, which may have resulted in bias. Lastly, therapist fidelity was not formally assessed and should be in future trials.

Results from the current study suggest that MBCT-C may be effective for improving global clinical severity among anxious youth with a familial risk for bipolar disorder. Future studies utilizing a more rigorous, randomized design with larger sample sizes are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded with support from the Depressive and Bipolar Disorder Alternative Treatment Foundation (DBDAT) (Delbello and Cotton, Co-PIs). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: Dr. DelBello has received research support from Otsuka, Lundbeck, Sunovion, Pfizer, Johnson and Johnson, Supernus, Sunovion and Consulting/Advisory Board/Honoraria from Pfizer, Lundbeck, Sunovion, Supernus, Johnson and Johnson, Neuronetics, Akili. Dr. Strawn has received research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIMH/NIEHS) as well as Edgemont, Eli Lilly, Forest, Shire, Lundbeck, Neuronetics. He has received material support from Genesight/Assurex Health and receives royalties from the publication of two texts (Springer) and serves as an author for UpToDate and an Associate Editor for Current Psychiatry. Dr. Sears has written a number of books on and regularly presents workshops on mindfulness and MBCT. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Each child and their parent or legal guardian provided assent and written informed consent, respectively

Data Availability: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychology. (2008). Facts for Families. Retrieved from www.aacap.org

- Arrindell WA (2001). Changes in waiting-list patients over time: Data on some commonly-used measures. Beware! Behavior Research Therapy, 39, 1227–1247. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelow B, Baldwin DS, Dolberg OT, Andersen HF, & Stein DJ (2006). What is the threshold for symptomatic response and remission for major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder?. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67, 1–478. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody J, & Baer RA (2009). How long does a mindfulness-based stress reduction program need to be? A review of class contact hours and effect sizes for psychological distress. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 627–638. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary N (2002). SAS Institute Inc. USA, SAS for Windows Release, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Chang KD, Steiner H, & Ketter TA (2000). Psychiatric phenomenology of child and adolescent bipolar offspring. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescscent Psychiatry, 39, 453–460. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, & Serretti A (2011). Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 187, 441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly SD, & Bernstein GA (2007). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 267–83. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246070.23695.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S, Luberto CM, Sears R, Strawn J, Stahl L, Wasson R, Blom T, & Delbello M (2015). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for youth with anxiety disorders at risk for bipolar disorder: A pilot trial. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 10, 426–434. doi: 10.1111/eip.12216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finniss DG, Kaptchuk TJ, Miller F, & Benedetti F (2010). Biological, clinical, and ethical advances of placebo effects. The Lancet, 375, 686–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61706-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa TA, Noma H, Caldwell DM, Honyashiki M, Shinohara K, Imai H, Chen P, Hunot V, & Churchill R (2014). Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 130, 181–92. doi: 10.1111/acps.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, & Craney JL (2001). Bipolar disorder at prospective follow-up of adults who had prepubertal major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 125–127. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, DelBello MP, & Soutullo C (2001). Reliability of the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) mania and rapid cycling sections. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescscent Psychiatry, 40, 450–455. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco LA, Baer RA, & Smith GT (2011). Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: development and validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM). Psychological Assessessment, 23, 606–614. doi: 10.1037/a0022819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg GS, Kendall PC, Sakolsky D, Compton SN, Piacentini J, Albano AM, et al. (2011). Remission after acute treatment in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: Findings from the CAMS. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 806–813.doi: 10.1037/a0025933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W (1976). ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. US Department of Health, and Welfare, 534–537. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Follete VM, & Linehan M (2004). Mindfulesness and Acceptance: Expanding the Cognitive-Behavioral Tradition. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, & Strosahl K (1996). Experimental avoidance and behavioral disorders: a functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1152–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawke LD, Provencher MD, & Arntz A (2011). Early Maladaptive Schemas in the risk for bipolar spectrum disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 133, 428–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henin A, Biederman J, Mick E, Sachs GS, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Siegel RS, et al. (2005). Psychopathology in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a controlled study. Biolgical Psychiatry, 58, 554–561. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.6.1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, & Oh D (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Crane R, & Dalgleish T (2012). Does mindfulness based cognitive therapy prevent relapse of depression? BMJ, 345, e7194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Semple R, Rosa D, & Miller L (2008). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Children: Results of a Pilot Study. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 22, 15–28. doi: 10.1891/0889.8391.22.1.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piet J, & Hougaard E (2011). The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 1032–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Cook SC, & Carroll BJ (1979). A depression rating scale for children. Pediatrics, 64, 442–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Cook SC, Carroll BJ, & Corzo H (1983). Use of the Children’s Depression Rating Scale in an inpatient psychiatric population. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 44, 200–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichart CG, & Nolen WA (2004). Earlier onset of bipolar disorder in children by antidepressants or stimulants? An hypothesis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 78, 81–84. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00180-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group. (2002). The Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS): Development and psychometric properties. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 1061–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Williston SK, & Rollins LG (2015). Mindfulness and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sears R (2015). Building Competence in Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sears RW, Tirch DD, & Denton RB (2011). Mindfulness in Clincial Practice. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press. [Google Scholar]

- Segal Z, Teasdale, & Williams, J. (2004). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy: Theoretical Rationale and Empirical Status In Hayes S, Follete V & Linehan M (Eds.), Mindfulesness and Acceptance (pp. 45–65). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Semple R, & Lee J (2011). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Anxious Children: A Manual for Treating Childhood Anxiety. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Semple R, Lee J, Rose D, & Miller L (2010). A Randomized Trial of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Children: Promoting Mindful Attention to Enhance Social-Emotional Resiliency in Children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 218–229. [Google Scholar]

- Semple RJ (2005). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Children: A Randomized Group Psychotherapy Trial Developed to Enhance Attention and Recude Anxiety. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Columbia University; New York. [Google Scholar]

- Semple RJ (2010). Does mindfulness meditation enhance attention? A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 1, 121–130. doi: 10.1007/s12671-010-0017-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, & Cicchetti D (1997). Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology, 33, 906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh MK, DelBello MP, Stanford KE, Soutullo C, McDonough-Ryan P, McElroy SL, & Strakowski SM (2007). Psychopathology in Children of Bipolar Parents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 102, 131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Flannery-Schroeder EC, & Kendall PC (2003). A psychometric evaluation of the parent report form of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children--Trait Version. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 17, 427–446. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00223-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawn JR, Adler CM, McNamara RK, Welge JA, Bitter SM, Mills NP, . . . DelBello MP (2014). Antidepressant tolerability in anxious and depressed youth at high risk for bipolar disorder: a prospective naturalistic treatment study. Bipolar Disorders, 16, 523–530. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawn JR, Cotton S, Luberto CM, Patino LR, Stahl LA, Weber WA, . . . DelBello MP (2016). Neural Function Before and After Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Anxious Adolescents at Risk for Developing Bipolar Disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26, 372–379. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawn JR, Sakolsky DJ, & Rynn M (2012). Psychopharmacologic treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 21, 527–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Williams JM, Ridgeway VA, Soulsby JM, & Lau MA (2000). Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, et al. (2000). Ginsburg GS, Rynn MA, McCracken J, Waslick B, Iyengar S, March JS, Kendall PC: Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. New England Journal of Medicine, 359, 2753–2766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]