According to the most recent WHO estimates, Brazil has the highest number of diagnosed COVID-19 cases in the Americas Region after the United States [1]. Community transmission has been documented throughout all federal units (26 states and Federal district).

Since the beginning of pandemic, many organizations have raised concerns with the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), low observance of social distancing measures, and scarce availability of diagnostic tests in Brazil [2,3]. MoH recommended use of diagnostic swabs be reserved for severe cases with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) [4]. No specific federal recommendations on case finding among health workers (HW) currently exist.

Data from other countries have clearly indicated that HW are disproportionally affected by COVID-19 and can be carriers of the disease. In Italy, 20 618 COVID-19 cases have been reported so far among HW (10.4% of total cases) [5]. The Italian National Federation of Medical Doctors and Odontologists has reported 151 deaths among doctors [6]. These data do not include other HW categories such as nurses or midwives. In US, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 9282 COVID-19 cases confirmed among HW [7] among these 723 (8%-10%) were hospitalized and 184 (2%-5%) required intensive care unit (ICU) admission.

In defense of HW safety, the Brazilian Federal Council of Medicine (FCM) has taken several measures. HW safety guidelines have been widely circulated, with hospital inspections carried out to verify their implementation. An online platform has been established for professionals to report shortcomings of resources, such as lack of PPE in workplaces, either public or private. Finally, the FCM is advocating for expanding criteria for COVID-19 diagnostic tests to all symptomatic HW [8].

Yet frontline workers are dangerously ill-equipped due to decades of underinvestment in the public health sector and limited access to appropriate PPE and training [9,10]. The Brazilian Federal Council of Nursing highlighted around 4800 reports of lack of PPE made by associate members since the beginning of pandemic. In the same time period, there have been more than 4600 sick leaves for “influenza-like symptoms” and 32 deaths among nurses, numbers significantly higher than usual trends [10]. Brazilian media have claimed that the number of COVID-19 cases and related deaths among HW, in particular in selected states such as São Paulo and Maranhão, is rapidly increasing [11].

Photo: Brazilian Federal Council of Medicine online platform for reporting shortcomings of resources (eg, personal protective equipment) in workplaces. Used with permission kindly provided by Brazilian Federal Council of Medicine.

Open Knowledge Brazil (OKBR), a civil society organization that operates in support of open-access data of public interest, ranked Brazilian states with a “Transparency index”, evaluating 13 criteria related to content, format and level of detail of information disclosed via official portals during COVID-19 pandemic [12]. Despite improvements in the last weeks, on 22 April only four (15.3%) Brazilian states published data on the availability of COVID-19 diagnostic tests, while 11 (42.3%) provided data on incidence of new ARDS cases [12]. The “Transparency index” had a major impact on public opinion in Brazil, and civil public legal action was taken against San Paulo state using these data. However, the Transparency index does not include availability of data on COVID-19 among HW to evaluate states.

We report here the results of a rapid review performed by systematically screening each of the 27 federal health department websites and COVID-19 dedicated portals in order to identify specific policies for HW health screening and testing, and related HW morbidity and mortality data. Data collection procedures were integrated by research on social networks. Data are updated on 27 April 2020.

Results indicated that Pernambuco, a state in Northeast, was the first to develop a policy to perform diagnostic swabs among all symptomatic HW on 4 April 2020, giving priority to HW in ICUs and emergency departments. Policies in other states were less clear, with limited availability on official websites. Major investments were made in rapid tests for qualitative antibody detection whose accuracy is still unclear.

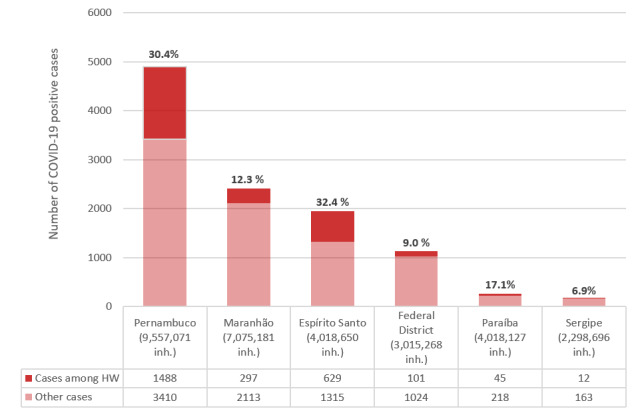

Information regarding COVID-19 confirmed cases among HWs was available in the official bulletins of only six (22.2%) Brazilian Federal states (Figure 1). As expected based on current policies, a significantly higher number of cases was detected in Pernambuco compared to other states, with a high prevalence in HW (30.8% of total cases). As many states are currently implementing massive rapid test programs, increased numbers of COVID-19 cases among HW are expected in coming weeks.

Figure 1.

COVID-19 positive cases among health workers by Brazilian federal state. HW – health worker. Note: only six states had data available on health worker infection; Pernambuco state has a policy for HW testing. Data sources: State epidemiological bulletins, accessed 27 April 2020 [13-19].

These data demonstrate a lack of a homogeneous, transparent, and comprehensive surveillance system for COVID-19 cases among Brazilian HW during the current pandemic. Coordinated policies are needed to increase HW protection, and availability of surveillance data, to protect both HW and the entire Brazilian population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rebecca Lundin for the English language review.

Ethical statement: This article does not contain any studies involving human participants.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Authorship contributions: EPV conceived the paper in discussion with LCVCD and ML. LSL, MFSP and EPV collected data. EPV drafted the initial manuscript and all authors reviewed/edited the manuscript for critically important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The authors completed the ICMJE Unified Competing Interest form (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Accessed: 30 April 2020.

- 2.Conselho Nacional de Saúde – Brasil. NOTA PÚBLICA: CNS defende manutenção de distanciamento social conforme define OMS (08/04/2020). Available: https://conselho.saude.gov.br/ultimas-noticias-cns/1102-nota-publica-cns-defende-manutencao-de-distanciamento-social-conforme-define-oms. Accessed: 20 April 2020.

- 3.PAHO. COVID-19: PAHO Director calls for “extreme caution” when transitioning to more flexible social distancing measures. Available: https://www.paho.org/en/news/14-4-2020-covid-19-paho-director-calls-extreme-caution-when-transitioning-more-flexible-social. Accessed: 20 April 2020.

- 4.BRASIL. Diretrizes para Diagnóstico e Tratamento da COVID-19. Versão 1. Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovação e Insumos Estratégicos em Saúde – SCTIE. Brasília – DF, 6 de abril de 2020.

- 5.Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Epidemia COVID-19. “Sorveglianza integrata COVID-19 in Italia”. Aggiornamento 27 aprile 2020. Available: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Infografica_27aprile%20ITA.pdf. Accessed: 28 April 2020.

- 6.Federazione Nazionale degli Ordini dei Medici Chirurghi e degli Odontoiatri. Elenco dei Medici caduti nel corso dell’epidemia di Covid-19. Available: https://portale.fnomceo.it/elenco-dei-medici-caduti-nel-corso-dellepidemia-di-covid-19/. Accessed: 27 April 2020.

- 7.Characteristics of Health Care Personnel with COVID-19 — United States February 12–April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:477-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conselho Federal de Medicina. PANDEMIA COVID-19: Notas e esclarecimentos do CFM. Available: http://portal.cfm.org.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=28634 Accessed: 22 April 2020.

- 9.Confederação Nacional dos Trabalhadores na Saúde – Brasil. Profissionais de saúde estão expostos e sem proteção. Available: https://cnts.org.br/noticias/profissionais-de-saude-estao-expostos-e-sem-protecao/. Accessed: 20 April 2020.

- 10.COFEN. Conselho Federal de Enfermagem. “Mais de 4 mil profissionais foram contaminados pela COVID-19” (20/04/2020). Available: http://www.cofen.gov.br/mais-de-4-mil-profissionais-de-enfermagem-foram-contaminados-pela-covid-19_79240.html. Accessed: 20 April 2020.

- 11.Atual RB. “Sindicato registra morte de 16 trabalhadores da saúde pela covid-19 em São Paulo” (13/04/2020). Available: https://www.redebrasilatual.com.br/trabalho/2020/04/trabalhadores-saude-covid-19/ Accessed: 20 April 2020.

- 12.Brasil OK. (OKBR). Índice de Transparência da Covid-19. Available: https://www.ok.org.br/projetos/indice-de-transparencia-da-covid-19/. Accessed: 27 April 2020.

- 13.Epidemiológico B. COVID-19. Secretaria de Estado da Saúde do Maranhão (Boletim atualizado até às 18h – 26/04/2020. Portal da Saúde. Available: http://www.saude.ma.gov.br/boletins-covid-19/. Accesses: 27 April 2020.

- 14.Governo do Estado do Espírito Santo. Painel COVID-19 do Espírito Santo. Available: https://coronavirus.es.gov.br/painel-covid-19-es. Accessed: 27 April 2020.

- 15.Secretaria de Saúde de Pernambuco. ATUALIZAÇÕES EPIDEMIOLÓGICAS SES/PE. Informe Epidemiológico Coronavírus (COVID-19). Nº 56 – Pernambuco 26/04/2020. Available: https://www.cievspe.com/novo-coronavirus-2019-ncov. Accessed: 27 April 2020.

- 16.Secretaria de Saúde de Pernambuco. Secretaria-Executiva de Vigilância em Saúde. Covid-19: Nota orienta testagem de profissionais (04/04/2020). Available: http://portal.saude.pe.gov.br/noticias/secretaria-executiva-de-vigilancia-em-saude/covid-19-nota-orienta-testagem-de-profissionais. Accessed: 20 April 2020.

- 17.Secretaria de Estado da Saúde. Gerência Executiva de Vigilância em Saúde. COVID-19 SES-PB, Boletim Epidemiológico n.10 (21/04/2020). Available: https://paraiba.pb.gov.br/diretas/saude/consultas/vigilancia-em-saude-1/boletins-epidemiologicos. Accessed 27 April 2020.

- 18.Governo do Estado de Sergipe. Secretaria de Estado da Saúde de Sergipe. Boletins. Availablet: https://todoscontraocorona.net.br/boletins/. Accessed: 27 April 2020.

- 19.Secretaria de Saúde do Distrito Federal. Boletins Informativos sobre Coronavirus (COVID-19) (SVS/DIVEP/CIEVES). Informe n° 55 – 26 abril 2020. Available: http://www.saude.df.gov.br/boletinsinformativos-divep-cieves/. Accessed: 28 April 2020.