Abstract

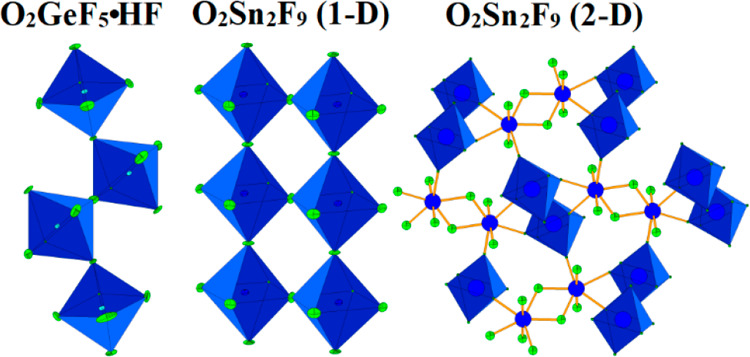

By treating gaseous, liquid, or solid fluorides with UV-photolyzed O2/F2 mixtures and by treating solid oxides with UV-photolyzed F2 (or O2/F2 mixtures) in liquid anhydrous HF at ambient temperature, we investigated the possibility of the preparation of O2MIIIF4 (M = B, Fe, Co, Ag), O2MIVF5 (M = Ti, Sn, Pb), (O2)2MIVF6 (M = Ti, Ge, Sn, Pb, Pd, Ni, Mn), O2MIV2F9 (M = Sn), O2MVF6 (M = As, Sb, Au, Pt), O2MV2F11 (M = Pt), O2MVIF7 (M = Se), (O2)2MVIF8 (M = Mo, W), and O2MVIIF8 (M = I). The approach has been successful in the case of previously known O2BF4, O2MF6 (M = As, Sb, Au; Pt), O2GeF5, and (O2)2(Ti7F30). Novel compounds O2GeF5·HF, α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D), and the HF-solvated and nonsolvated forms of β-O2Sn2F9 (2-D) were synthesized and their crystal structures determined using single-crystal X-ray diffraction. The crystal structures of all of these materials arise from the condensation of octahedral MF6 (M = Ge, Sn) units. The anion in the crystal structure of O2GeF5·HF is comprised of infinite ([GeF5]−)∞ chains of GeF6 octahedra that share common vertices. The HF molecules and O2+ cations are located between the chains. The crystal structure of α-O2SnF9 (1-D) is constructed from [O2]+ cations and polymeric ([Sn2F9]−)∞ anions which appear as two parallel infinite chains comprised of SnF6 units, where each SnF6 unit of one chain is connected to a SnF6 unit of the second chain through a shared fluorine vertex. The single-crystal structure determination of [O2][Sn2F9]·0.9HF reveals that it is comprised of two-dimensional ([Sn2F9]−)∞ grids with [O2]+ cations and HF molecules located between them. The 2-D grids have a wavelike conformation. The ([Sn2F9]−)∞ layer contains both six- and seven-coordinated Sn(IV) atoms that are interconnected by bridging fluorine atoms. A new, more complex [O2]+ salt, O2[Hg(HF)]4[SbF6]9, was prepared. In its crystal structure, the Hg atoms bridge to SbF6 units to form a 3-D framework. The O2+ cations are located inside the voids while the HF molecules are bound to Hg atoms through the F atom. Attempts to prepare several chlorine analogues of O2+ fluorine salts (i.e., O2TiCl5 and O2MCl6 (M = Nb, Sb)) failed.

Short abstract

Reactions between fluorides and/or oxides and UV-irradiated F2 and/or F2/O2 mixtures were carried out in anhydrous hydrogen fluoride at ambient temperature to prepare O2+ salts. The crystal structures of O2GeF5·HF and O2GeF5 consist of infinite polymeric ([GeF5]−)∞ anions. The O2Sn2F9 salt exhibits polymorphism consisting of a 1-D phase built from double chainlike ([Sn2F9]−)∞ anions and a 2-D phase built from layerlike anions. The latter also exists as a solvated form O2Sn2F9·nHF. The crystal structure of O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9 is isotypic to that of H3O[Cd(HF)]4(SbF6)9. The Hg atoms are bridged by SbF6 groups forming a 3-D framework with O2+ cations located inside the voids. The HF molecules are bound to Hg atoms through the F atom.

Introduction

Dioxygenyl salts are useful reagents for the oxidation of organic compounds to the corresponding cation radicals.1,2 The O2AsF6 and O2SbF6 are capable of oxidizing C6F6 and C5F5N to C6F6+, yielding [C6F6]+[MF6]− (M = As, Sb)3,4 or [C6F5N]+[MF6]− (M = As),5 respectively. The preparations of substituted and hydrogen-containing fluoroaryl cations (i.e., [C6F5X]+, X = H, CF3 or C6F5; [1,4-C6F4(CF3)2]+; [2,3,5,6-C6F4X2]+, X = H or CF3; [2,4,6-C6H3F3]+; [1,2,4,5-C6H2Cl4]+) as [AsF6]−, [SbF6]−, or [Sb2F11]− salts also have been reported.6,7 Other examples include the preparation of tertiary amine cation radicals8 and the oxidations of N,N,N,N-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine, 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane, and 1,5-dithiacyclooctane to the corresponding radical cations as shown by EPR spectroscopy.9 The reaction of (CF3)2NO with O2SbF6 produces CF3 radicals at low temperature.10 Displacement reactions between O2MF6 and suitable amphoteric molecules produce free O2F radicals which generate atomic fluorine in situ upon decomposition.11 A one-step reaction between carbon monoxide and dioxygenyl salts yields oxalyl fluoride [FC(O)C(O)F].12 The removal of radon and radioactive noble gas isotopes of xenon from contaminated atmospheres through the use of O2SbF6 was also studied.13,14 The reactivity of azides toward various dioxygenyl salts was investigated in the scope of research on highly energetic materials.15

The first dioxygenyl salt, O2PtF6, was reported by Bartlett and Lohmann in 1962.16,17 It was initially erroneously identified as PtOF4,18 which is not surprising given that the [O2]+ cation as the [PtF6]− anion were unknown at that time. It now appears that the dioxygenyl salt, O2BF4, may have been prepared at the same time, although the nature of this material was not elucidated at that time.19 After more than half a century, the number of known [O2]+ salts is still limited to approximately 25 examples.20,21 Almost two-thirds of them are O2MF6 and O2M2F11 (M = M5+) compounds. In addition to O2MF6 (M = Sb,22 Au,22−25 Rh,25 Ru,22,26 Pt22,27), only the crystal structures of O2BF4,28 (O2)2Ti7F30,29 O2Mn2F9,30 O2Ni(AsF6)3,20 and O2(H3Pd2F12)21 have been reported.

A convenient way to prepare dioxygenyl fluoride salts is by UV photolysis of gaseous, liquid, or solid fluorides with O2/F2 and by UV photolysis of oxides with F2 (or O2/F2 mixtures) in liquid anhydrous HF at ambient temperature.31 Applying this general method, we systematically investigated the possibility of the preparation of new or already known O2MIIIF4, O2MIVF5, (O2)2MIVF6, O2MIV2F9, O2MVF6, O2M2VF11, O2MVIF7, (O2)2MVIF8, and O2MVIIF8 compounds. We also investigated the possibility of preparing new, more complex [O2]+/metal mixed-cation salts of hexafluoridoantimonate(V). The results of this study are described in the present work.

Results and Discussion

Reactions between the corresponding fluoride, oxides, and/or metals and UV-irradiated F2 or F2/O2 mixtures were carried out in anhydrous hydrogen fluoride (aHF) at ambient temperature (Table 1). Two additional experiments were done in the absence of a solvent. The presence of O2+ in the solid state is easily detected by Raman spectroscopy.20,24,47

Table 1. Products Observed Resulting from the Reactions of the Corresponding Fluorides, Oxides, and/or Metals and UV-Irradiated F2 or F2/O2 Mixtures Carried out in aHF at Ambient Temperature.

| desired product | reactant 1 | reactant 2 | observed productsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| O2MIIIF4 | BF3 | O2/F2 | O2BF4b |

| O2MIIIF4 | FeF3 | O2/F2 | FeF3 |

| O2MIIIF4 | CoF2 | O2/F2 | CoF3 |

| O2MIIIF4 | AgF2 | O2/F2 | Ag3F8 |

| O2MIVF5 | TiO2 | F2 | (O2)2Ti7F30 |

| O2MIVF5 | SnO2 | F2 | O2Sn2F9·0.9HF, α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D)c |

| O2MIVF5 | PbO2 | F2 | PbF4 |

| (O2)2MIVF6 | TiO2 | O2/F2 | (O2)2Ti7F30 |

| (O2)2MIVF6 | SnO2 | O2/F2 | α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D), β-O2Sn2F9 (2-D), O2Sn2F9·0.9HFc |

| (O2)2MIVF6 | PbO2 | O2/F2 | PbF4 |

| (O2)2MIVF6 | GeF4 | O2/F2d | O2GeF5 |

| (O2)2MIVF6 | GeF4 | O2/F2 | O2GeF5·HFe |

| (O2)2MIVF6 | Pd2F6 | O2/F2 | O2PdF5/undefined [O2+]-saltf |

| (O2)2MIVF6 | NiF2 | O2/F2 | NiF2/NiF2+x |

| (O2)2MIVF6 | MnF2 | O2/F2 | undefined [O2+]-salt |

| O2M2IVF9 | SnO2 + SnF4 | F2 | α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D), O2Sn2F9·0.9HFc |

| O2MVF6 | AsF5 | O2/F2 | O2AsF6g |

| O2MVF6 | SbF3/SbF5 | O2/F2 | O2SbF6g |

| O2MVF6 | AuF3 | O2/F2 | O2AuF6g |

| O2MVF6 | Pt | O2/F2 | O2PtF6/Pt |

| O2M2VF11 | PtO2, Pt | F2 | no reaction |

| O2MVIF7 | SeO2 | F2 | SeF6 (?)h |

| (O2)2MVIF8 | MoO3 | O2/F2 | MoOF4 |

| (O2)2MVIF8 | WO3 | O2/F2 | WF6 (?)i |

| (O2)2MVIF8 | WF6 | O2/F2c | WF6 (?)i |

| O2MVIIF8 | IF5 | O2/F2 | IF7 (?)j |

| O2MVIIF8 | IF5 | O2/F2c | IF7 (?)j |

Products were identified by Raman spectroscopy and/or single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. There is always a possibility that phases present in minor amounts were overlooked.

Reference (20).

Two phases with the same empirical chemical formula O2SnF9 were obtained. The anion of the first one has a chainlike structure and the second one a layerlike structure. To distinguish between them, the former is designated as 1-D (one-dimensional) and the latter as 2-D (two-dimensional). Additionally, there is a third phase, that is, the HF solvated form of 2-D O2Sn2F9 (i.e., O2Sn2F9·0.9HF).

Formed in the absence of aHF solvent.

Single crystals were grown from saturated HF solutions at T < −10 °C.

The attempt to grow single crystals from an orange solution at T < −5 °C resulted in an orange-red undefined product of very poor crystallinity, whereas the insoluble material corresponded to a mixture of O2PdF5 and an undefined [O2+]-salt as shown by Raman spectroscopy.

Reference (31).

When isolation was attempted at room temperature (RT), everything pumped away; SeF6 is a colorless gas at RT.

When isolation was attempted at RT, everything pumped away; WF6 is a colorless liquid at RT.

When isolation was attempted at RT, everything pumped away; IF7 is a colorless gas at RT.

Attempted Syntheses of O2MIIIF4 (M = B, Fe, Co, Ag)

The reported syntheses of O2BF4 include the reaction between BF3 and O2F2.28 The resulting O2BF4 salt decomposes above 0 °C. When the synthesis is done in liquid aHF in a FEP reaction vessel (Table 1), the volatile compounds can be easily pumped away at low temperature and pure O2BF4 can be recovered in a quantitative yield (Figure S1, see the Supporting Information).

Attempts to prepare O2+ analogues of KMF4 (M = Fe, Co)32 failed (Table 1). Only the corresponding trifluorides were recovered after isolation at room temperature.

An attempt to prepare the previously reported O2AgF4 salt33 also failed, although O2AgF4 is claimed to have been obtained in some reactions of O2F2 with silver compounds in ClF5 solution. The reaction between AgF2 and a UV-irradiated mixture of F2/O2 (Table 1) resulted in Ag3F8 (i.e., the mixed-oxidation-state Ag[AgF4]2 fluoride34 (Figure S2, see the Supporting Information).

Attempted Syntheses of O2MIVF5 (M = Ti, Sn, Pb)

Two examples of O2MIVF5 compounds are known from the literature. The first is O2GeF5 prepared by UV photolysis of a GeF4/O2/F2 mixture in quartz at −78 °C, which is unstable at 25 °C.35 The second is O2PdF5, isolated from a deep orange solution presumed to contain (O2)2PdF6 dissolved in aHF.36

Since they already contain the required n(O)/n(M) = 2:1 molar ratio as in O2MIVF5, the corresponding dioxides MO2 (M = Ti, Sn, Pb) were used as starting materials (Table 1). The reaction between TiO2 and F2 in the presence of UV-light in aHF yielded only the previously known (O2)2(Ti7F30) salt,29 whereas in the case of PbO2, only PbF4 was recovered (Table 1 and Figure S3, see the Supporting Information). An attempt to synthesize O2SnF5 in a similar manner resulted in two phases of the novel O2[Sn2F9] compound (Figure S3, see Supporting Information).

Attempted Syntheses of (O2)2MIVF6 (M = Ge, Ti, Sn, Pb, Pd, Ni, Mn)

Dioxygenyl salts containing doubly charged mononuclear counterions (i.e., [MF6]2–, M = Mn, Ni) were prepared by metathetical reactions between 2O2SbF6 and Cs2MF6 (M = Mn, Ni) in aHF solution at −45 °C.37 The resulting compounds are marginally stable up to about 10 °C. Addition of a solution of a highly soluble salt A2PdF6 (A = K, Cs) in aHF to a solution of O2AsF6 in aHF at −30 °C yielded precipitates of AAsF6 and a deep orange solution presumed to contain (O2)2PdF6.36 Attempts to isolate the latter salt by removal of aHF at −60 °C always resulted in the O2 and F2 loss and the recovery of O2PdF5. However, further crystallizations at T < −70 °C resulted in the growth of single crystals of [O2][H3Pd2F12].21 It has been claimed that (O2)2SnF6 was obtained by the reaction of O2F2 with SnF4.38 However, this reaction is of low yield and poor reproducibility.

The products of the reactions between MO2 (M = Ti, Sn, Pb) and UV-irradiated F2 in the presence of an excess of O2 and in aHF solvent were identical to those obtained in attempts to prepare O2MF5 compounds where no additional O2 was used (Table 1). Reactions with TiO2 gave (O2)2(Ti7F30)29 and reactions with SnO2 yielded [Sn2F9]− salts. In the case of PbO2, only PbF4 was recovered.

The reaction between GeF4 and F2/O2 exposed to UV light in the absence of solvent (Table 1) resulted in the previously known O2GeF5 salt (Figure S4, see the Supporting Information).35 When the reaction was carried out in liquid HF and single crystals were grown from a saturated HF solution at T < −10 °C, the HF solvated form of O2GeF5 was obtained (i.e., O2GeF5·HF). A similar attempt to grow single crystals from an orange solution prepared by reaction of Pd2F6 and a UV-irradiated F2/O2 mixture in aHF, and further crystallization at T < −5 °C, resulted in an orange-red, poorly crystalline product that was unsuitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurements, and the insoluble material corresponded to O2PdF536 and an undefined [O2+]-salt (Figure S5, see the Supporting Information).

When the NiF2/F2/O2 mixture was irradiated with UV light, aHF-insoluble, pale yellow-green NiF2 turned black on the surface. This suggests that NiF2 is partially fluorinated to NiF2+x (x ≤ 1). The same phenomenon was observed when NiF2 was exposed to UV-irradiated F2 in aHF in the absence of O2.31 The Raman spectrum of the product resulting from the reaction of MnF2 with F2/O2 in the presence of a UV source in aHF showed a vibrational band at 1827 cm–1, which could be assigned to O2+ (Figure S6, see the Supporting Information). The ν(O2+) band occurs at 1805 cm–1 in the Raman spectrum of (O2)2MnF6,37 and that of O2Mn2F930 at 1838 cm–1. In addition, during the syntheses of MnF4 by photodissociated F2 and MnF2 or MnF3 in aHF, a broad band at 1834 cm–1 was sometimes observed.39 This indicates that, in addition to (O2)2MnF6 and O2Mn2F9, at least two more O2+/Mn4+ fluoride salts must exist, although their compositions remain an open question.

Attempted Syntheses of O2MIV2F9 (M = Sn)

There is only one previously known example of an O2MIV2F9 salt, i.e., O2Mn2F9, which was first prepared by treating MnO2 or MnFx (x = 2, 3, 4) with an F2/O2 mixture under quite drastic conditions (p(F2)/p(O2) ≈ 300–3500 atm, T ≈ 300–550 °C).30

In this work, we were able to prepare an analogue of an O2MIV2F9 compound with tin by carrying out a chemical reaction between SnO2, SnF2 (molar ratio 1:1), and UV-irradiated F2 in liquid aHF at ambient temperature (Figure S7, see Supporting Information).

Attempted Syntheses of O2MVF6 (M = As, Sb, Au, Pt)

Because the O2MVIF6 salts are among the most studied O2+ salts,17,22−27 we did not place a great deal of emphasis on further examples. The O2MVIF6 (M = As, Sb, Au) salts can be conveniently prepared by treating MF3 (M = As, Sb, Au) or MF5 (M = As, Sb) with a UV-irradiated F2/O2 mixture in aHF (Table 1).31 Since AsF5 is a gas and SbF5 is a liquid at room temperature, O2AsF6 and O2SbF6 can be prepared photochemically (even by exposure to daylight40) directly from the corresponding binary fluorides, O2, and F2 in the absence of HF22,41 or by other approaches (using O2F242 or high-temperature syntheses22,43). Therefore, the synthetic method is a matter of choice. When the syntheses are done in liquid aHF in FEP reaction vessels, the volatiles can be easily removed at low or ambient temperature and pure O2MF6 (M = As, Sb, Au) salts are recovered in quantitative yields. The attempt to prepare O2PtF6 by treating Pt metal with a UV-irradiated O2/F2 mixture in aHF was only partially successful. The desired compound was formed (Figure S8, see the Supporting Information), but the yield was low. A much more facile synthesis of pure O2PtF6 without the demanding synthesis of PtF6, or the use of high-pressure fluorination, has recently been reported.44

Attempted Syntheses of O2MV2F11 (M = Pt)

In addition to O2MVIF6, O2MV2F11 is the second most prevalent group of O2+ salts that is described in the literature.41,45−47 Based on vibrational spectroscopic data, their structures consist of O2+ cations and dimeric M2F11– anions.47 The only crystal structure that has been determined from single-crystal X-ray diffraction data for this class of O2+ salts is O2Pt2F11, but a complete structure determination has never been published.48 Our attempt to prepare O2Pt2F11 by reaction between PtO2/Pt (molar ratio 1:1) and UV-irradiated F2 in aHF failed (Table 1).

Attempted Syntheses of O2MVIF7 (M = Se), (O2)2MVIF8 (M = Mo, W), and O2MVIIF8 (M = I)

There is no indication in the literature for the formation of [SeF7]−, whereas [MF7]− (M = W, Mo) are well-known.49 Tungsten hexafluoride can add two fluoride anions to form [WF8]2–, but [MoF8]2– has not yet been observed.49 The [IF8]− anion has been observed in the crystal structure of [NO(NOF)2][IF8].50 There are reports of the syntheses of NOMF7 (M = Mo, W) and (NO)2WF8.51 A brief mention of analogous O2+ salts is limited to the possible existence of O2MoF7 and O2WF7,38 although these data have not been confirmed. All of our attempts to synthesize O2+ salts of the [MVIF7]− (M = Se), [MVIF8]2– (M = Mo, W) or [MVIIF8]− (M = I) anions failed (Table 1). In each case, nothing remained in the reaction vessels after volatile compounds had been removed under vacuum at room temperature. It can be assumed that the WF6 (starting material or formed by fluorination of WO3) and IF7 (formed by fluorination of IF5) were simply pumped off at room temperature. The chemical reaction between MoO3 and the UV-irradiated F2/O2 mixture resulted in a colorless solution from which a colorless material was recovered. Its Raman spectrum was identical to the reported Raman spectrum of solid MoOF4, which was obtained by cooling its melt (Figure S9, see the Supporting Information).52 A very weak vibrational band at 1850 cm–1 was sometimes observed, indicating the presence of an unknown O2+ salt.

Attempted Syntheses of (O2)2Hg2F(SbF6)5 and (O2)2Hg2(SbF6)6

In the case of more complex O2+ salts, only O2Ni(AsF6)3 has been reported thus far.20 Because the synthesis and crystal data of (O2)2Hg2F(SbF6)553 have never been published, we were interested in determining if it is possible to prepare this compound in liquid aHF by reaction between O2SbF6, HgF2, and SbF5 (formed in situ by fluorination of SbF3 with elemental F2) in the required molar ratio, 2:2:3. We also explored the possibility of preparing (O2)2Hg2(SbF6)6 by using a larger amount of SbF5 [n(O2SbF6)/n(HgF2)/n(SbF5) = 2:2:4]. In both cases, the growth of crystals from saturated aHF solutions resulted in single crystals of O2SbF6, Hg(HF)(SbF6)2,54 and previously unknown O2SbF6·([Hg(HF)][SbF6]2)4 (better formulated as O2[Hg(HF)]4[SbF6]9). The pure phase can be obtained when the appropriate starting ratio [n(O2SbF6)/n(HgF2)/n(SbF5) = 1:4:8] is used (Figure S10, see the Supporting Information).

Attempted Syntheses of O2MVCl6, O2MIVCl5, and (O2)2SO4

Since all known O2+ salts are based on fluorides, it is clear that nonoxidizable anions are required to stabilize O2+. We were interested in determining what would happen when SbCl5/Cl2/O2, TiCl4/Cl2/O2/HCl, and NbCl5/Cl2/O2/HCl mixtures are exposed to UV-light. Both SbCl5 and TiCl4 are liquids, but NbCl5 is a solid at room temperature. In the cases of TiCl4 and SbCl5, the formation of yellow solids was observed (Figure S11, see the Supporting Information). The absence of vibrational bands in the 1800–1870 cm–1 region of the Raman spectra of the isolated solids showed that no O2+ salts were formed. This was also the case when NbCl5 was used as the starting material. Therefore, the products were not investigated further.

The relative oxidizing strength of O2+ has been estimated to be close to that of Ag2+(solv) (i.e., cationic Ag2+ in aHF solution).55 A metathetical reaction between K2SO4 and Ag(SbF6)2 in aHF yields AgIISO4.56 Our similar attempt to prepare (O2)2SO4 by a metathetical reaction between K2SO4 and 2O2SbF6 in aHF also failed. Only KSbF6 was recovered upon isolation of the solid at −15 °C.

Crystal Structures of O2SnF9 (1-D and 2-D), O2SnF9·0.9HF, O2GeF5·HF, and O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9

The corresponding crystal data and refinement results for α- and β-O2SnF9 (1-D and 2-D), O2SnF9·0.9HF, O2GeF5·HF, and O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9 are summarized in Table 2, and the unit cell parameters of O2GeF5 are also provided.

Table 2. Summary of Crystal Data and Refinement Results of α- and β-O2SnF9 (1-D, 2-D), O2SnF9·0.9HF, O2GeF5·HF, and O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9 Compounds and Unit Cell Data for O2GeF5.

| chemical formula | O2GeF5·HFa | O2Sn2F9·0.9HF | β-O2Sn2F9 (2-D) |

| Fw (g/mol) | 219.60 | 460.39 | 440.42 |

| crystal system | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| space group | I2/a | P21/c | P21/c |

| a (Å) | 9.8444(8) | 8.9497(5) | 9.1318(9) |

| b (Å) | 8.0274(6) | 10.5235(5) | 9.8027(5) |

| c (Å) | 13.1030(12) | 8.7920(4) | 8.7741(6) |

| α (deg) | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β (deg) | 110.774(10) | 94.401(5) | 105.334(8) |

| γ (deg) | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| V (Å3) | 968.14(15) | 825.61(7) | 757.46(10) |

| Z | 8 | 2 | 4 |

| T (K) | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| R1b | 0.0278 | 0.0351 | 0.0569 |

| wR2c | 0.0722 | 0.0944 | 0.158 |

| chemical formula | α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D) | O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9 |

| Fw (g/mol) | 440.42 | 3036.14 |

| crystal system | orthorhombic | monoclinic |

| space group | Immm | C2/c |

| a (Å) | 4.0473(3) | 21.0387(6) |

| b (Å) | 8.0199(4) Å | 10.2412(3) |

| c (Å) | 11.4491(8) | 21.1577(6) |

| α (deg) | 90 | 90 |

| β (deg) | 90 | 99.489(2) |

| γ (deg) | 90 | 90 |

| V (Å3) | 371.63(4) | 4496.3(2) |

| Z | 2 | 4 |

| T (K) | 200d | 150 |

| R1b | 0.0152 | 0.0364 |

| wR2c | 0.0362 | 0.0860 |

For nonsolvated O2GeF5, only the unit cell was determined: monoclinic, P21/n, a = 6.070(2) Å, b = 4.993(1) Å, c = 13.197(4) Å, β = 96.93(3)°, V = 397.2 Å3, Z = 4, T = 150 K.

R1 = Σ||F0| – |Fc||/Σ|F0| for I > 2σ(I).

wR2 = [Σ[w(F02 – Fc2)2]/Σw(F02)2]1/2.

Crystal structure determined at 296 K is the same as at 200 K.

Crystal Structures Containing Polymeric [GeF5]− Anions

Besides the well-known octahedral [GeF6]2– anion, only two other examples of fluoridogermanate(IV) anions have been described. The first is the polymeric chainlike ([GeF5]−)∞57 anion and the second is the [Ge3F16]4– oligomer.58 Both are built from GeF6 octahedra which share common vertices.

O2GeF5·HF

Low-temperature crystallization (Table 1) of the product of the reaction between GeF4 and a UV-irradiated F2/O2 mixture in aHF resulted in the single crystals of O2GeF5·HF (Table 2). The crystal structure consists of infinite polymeric ([GeF5]−)∞ anions, which appear as zigzag single chains of GeF6 octahedra (Figure 1) linked by cis-vertices and O2+ cations and HF molecules located between the chains (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Geometry of ([GeF5]−)∞ anions in O2GeF5·HF and hydrogen bonding between HF molecules and the polymeric anions. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Figure 2.

Unit cell and packing of anions, cations, and HF molecules in the crystal structure of O2GeF5·HF.

The crystal structure of ClO2GeF5 also contains infinite polymeric ([GeF5]−)∞ anions appearing as zigzag single chains of GeF6 octahedra linked by cis-vertices.57 However, despite the same motif in the GeF5 chain, the conformations of ([GeF5]−)∞ anions in ClO2GeF5 and O2GeF5·HF are different (Figure S12, see the Supporting Information). The geometry of the ([GeF5]−)∞ chains in ClO2GeF5 is similar to that observed for ([MnF5]−)∞ in XeF5MnF559 and ([TiF5]−)∞ in [C(NH2)3]4[H3O]4[Ti4F20][TiF5]4,60 whereas the geometry of the ([GeF5]−)∞ anion in O2GeF5·HF is closer to that of ([TiF5]−)∞ determined in A[TiF5], A[TiF5]·HF (A = Na, K, Rb, Cs)61 and [enH2]0.5[TiF5] (en = ethylenediamine).62 In the crystal structure of O2GeF5·HF, there is one crystallographically unique germanium atom coordinated by six crystallographically independent fluorine atoms, resulting in slightly distorted GeF6 octahedra. The Ge–Ft bond lengths between germanium atoms (Ge) and terminal fluorine atoms (Ft) range from 1.729(2) Å to 1.7545(19) Å and are shorter than the bonds between Ge and the bridging fluorine atoms (Fb): 1.8817(3) Å for Ge–F6 and 1.8934(9) Å for Ge–F7. They are comparable to those observed in ClO2GeF5 and XeF5GeF5 [Ge–Ft = 1.728(3)–1.75(2) Å and Ge–Fb = 1.887(1)–1.890(1) Å]. The observed Ge–F6–Ge and Ge–F7–Ge angles are 180.0° and 140.04(13)°, respectively. Thus, the zigzag chains of ([GeF5]−)∞ anions in O2GeF5·HF are oriented along the a-axis (Figure 1). Each GeF6 octahedron of the ([GeF5]−)∞ chain has one interaction with one HF molecule by means of a hydrogen bond, where the (Ge−)F4···(H−)F1 distance is 2.511 Å.

O2GeF5

The reaction between GeF4 and F2/O2 exposed to UV-light in the absence of solvent (Table 1) resulted in crystalline O2GeF5 (Figure S4, see the Supporting Information). Since numerous repeated attempts to obtain good quality X-ray diffraction data were unsuccessful, only the unit cell is reported (Table 2). Preliminary results show that the geometry of the anion is the same as that in the HF-solvated form, O2GeF5·HF, i.e., both compounds consist of polymeric ([GeF5]−)∞ chainlike anions of the same geometry. It can be concluded that O2GeF5·HF prepared at low temperature releases HF at elevated temperature to form O2GeF5. This is in accordance with the formula unit volumes (VF.U.) of both compounds: O2GeF5; VF.U = 99.3 Å3 and O2GeF5·HF; VF.U = 121.0 Å3. The difference of 21.7 Å3 can be attributed to the presence of HF in the latter.

Crystal Structures Containing ([Sn2F9]−)∞ Double Chainlike and Layerlike ([Sn2F9]−)∞ Anions

Raman spectroscopy indicates that the chemical reactions of SnO2 or a SnO2/SnF4 mixture with a UV-irradiated F2 or O2/F2 mixture in aHF always resulted in two or three phases (Figure S7, see the Supporting Information), which was confirmed by their single-crystal X-ray structures. The crystal structures of three unique O2+ salts, all containing polymeric ([Sn2F9]−)∞ anions, were determined. Two of them have the same empirical chemical formula, O2SnF9. The anion in the first salt has a chainlike structure, and the second salt has a layerlike structure. To distinguish them, the former is designated as 1-D (one-dimensional) and the latter as 2-D (two-dimensional). The third phase is the HF solvated form of 2-D O2Sn2F9 (i.e., 2-D O2Sn2F9·0.9HF). Bearing in mind that the Rb analogue of NaTi2F9 exists as the HF solvated form RbTi2F9·HF,61 the existence of a double chain-like 1-D O2Sn2F9·nHF structure cannot be ruled out.

The layered, polymeric ([Sn5F24]4–)∞ anion determined in [XeF5]4[Sn5F24] is the only example of a structurally characterized Sn(IV) fluoride compound that so far does not consist of only [SnF6]2– anions.63 Characterizations of other fluoridostannate(IV) anions have been limited to vibrational and NMR spectroscopy (tetrameric [Sn4F20]4– and dimeric [Sn2F10]2– oligomers).64,65 Compounds with empirical composition [N2F][Sn2F9] and [N2F3][SnF5] have also been reported.66,67 The former most likely does not have a monomeric structure but is more likely present as an oligomer [Sn4F18]2– or polymeric infinite, double ([Sn2F9]−)∞ chain, while the latter most probably has chainlike geometry similar to the ([TiF5]−)∞ anions observed in titanium-based compounds.61 With 18 different structurally characterized oligomeric and polymeric fluoridotitanate(IV) anions [TinF4n+x]x− (n, x ≥ 1), the chemistry of TiF4 has been much more extensively investigated60−62 than those of GeF4 and SnF4.

α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D)

The polymeric ([Sn2F9]−)∞ anions in α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D) appear as two parallel, infinite zigzag chains comprised of SnF6 units, where each SnF6 unit of one chain is connected to a SnF6 unit of the second chain through a shared fluorine vertex (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

([Sn2F9]−)∞ anion in the crystal structure of α-O2[Sn2F9] (1-D). Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

The geometries of such polymeric ([M2F9]−)∞ anions have been previously observed in various [Ti2F9]− salts.60,61 However, there is one significant difference. In those compounds, the Ti–Fb–Ti angles within the individual chains, which form double chainlike ([Ti2F9]−)∞ anions, are in the 150–160° range, while the Ti–Fb–Ti angles where the titanium atoms belong to two neighboring chains are in the 140–164° range. The corresponding Sn–Fb–Sn angles in ([Sn2F9]−)∞ are more open. The Sn1–F3–Sn1 angles within the individual chains are equal to 170.7(2)°), and the angles, where the Sn atoms belong to two neighboring chains, are linear (Sn1–F4–Sn1 = 180°).

The Sn atom is coordinated by six fluorine atoms. The three Sn–Fb bond lengths between tin and the bridging fluorine atoms are elongated (2 × Sn1–F3 = 2.0303(3) Å, Sn1–F4 = 2.0374(4) Å) in comparison with the three Sn–Ft bonds between tin and the terminal fluorine atoms (2 × Sn1–F1 = 1.898(2) Å, Sn1–F4 = 1.909(4) Å).

The negative charge of ([Sn2F9]−)∞ anions is compensated by partially disordered O2+ cations located between the chains (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Unit cell and packing of anions, cations, and HF molecules in the crystal structure of α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D).

O2[Sn2F9]·0.9HF

Dioxygenyl nonafluoridodistannate(IV) also crystallized from saturated HF solution as the solvate, O2[Sn2F9]·0.9HF. The single-crystal structure determination of O2[Sn2F9]·0.9HF reveals that its structure is different from that of O2[Sn2F9] (1-D). The anions resemble that determined in [XeF5]4[Sn5F24].63 In both compounds (1) the anions consist of two-dimensional (2-D) grids, i.e., ([Sn5F24]4–)∞ and ([Sn2F9]−)∞, respectively (Figure S13, see Supporting Information), and the [XeF5]+ or O2+ cations and HF molecules, respectively, are located between the grids (Figure 5). (2) Both types of 2-D grids have wavelike conformations (Figure S13, see Supporting Information), (3) Both the ([Sn5F24]4–)∞ and ([Sn2F9]−)∞) layers contain six- and seven-coordinated Sn(IV) interconnected by bridging fluorine atoms, and (4) SnF7 polyhedra in both cases share one edge forming dimer (Figure 6 and Figure S14, see Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

Two-dimensional ([Sn2F9]−)∞ grids with a wavelike conformation with the O2+ cations and HF molecules located between them in the crystal structure of O2[Sn2F9]·0.9HF.

Figure 6.

([Sn2F9]−)∞) layer in the crystal structure of O2[Sn2F9]·0.9HF contains both six- and seven-coordinated Sn(IV) interconnected by bridging fluorine atoms (view perpendicular to the layer, along the a-axis).

The Sn–F bond lengths in O2Sn2F9·0.9HF (2-D), α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D), and [XeF5]4[Sn5F24]63 can be divided into several groups (Table 3, Figure 7). The Sn–Fb(−Sn) bonds (Fb = fluorine atoms that bridge two Sn atoms) are longer in seven-coordinated (2.057(4)–2.1120(5) Å) than in six-coordinated Sn(IV) (1.992(6)–2.0374(4) Å). The Sn–Fb(···Xe) bonds, where F is involved in secondary bonding interactions with [XeF5]+ cations or in hydrogen bonding with HF molecules, are shorter (1.919(5)–1.963(6) Å) but longer than the Sn–Ft bonds (Ft = terminal fluorine atoms) of the seven- (1.879(6)–1.883(6) Å) and six-coordinated Sn atoms (1.898(2)–1.909(4) Å).

Table 3. Geometrical Parameters of Layerlike (2-D) ([Sn2F9]−)∞ and the Chainlike (1-D) Anions in the Crystal Structures of O2[Sn2F9]·0.9HF (2-D) and O2[Sn2F9] (1-D) and Literature Data for ([Sn5F24]4–)∞ Observed in [XeF5]4[Sn5F24].

| C.N. | bond/Å | [XeF5]4[Sn5F24]a | O2Sn2F9·0.9HF (2-D) | α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Sn–Ft | 1.879(6)/1.883(6) | 1.880(4)/1.887(4) | |

| 6 | Sn–Ft | 1.907(4)/1.909(4) | 1.898(2)–1.909(4) | |

| 6 | Sn–Fb···(H–F) | 1.933(4) | ||

| 6 | Sn–Fb···(XeF5) | 1.919(5)–1.963(6) | ||

| 6 | Sn–Fb(−Sn) | 1.992(6)/2.002(5) | 1.999(4)–2.010(4) | 2.0303(3)–2.0374(4) |

| 7 | Sn–Fb(−Sn) | 2.068(6)–2.120(5) | 2.057(4)–2.095(4) |

Reference (63).

Figure 7.

Coordination of two crystallographically unique Sn(IV) atoms and the secondary bonding interactions between SnF6 octahedra and HF molecules in the crystal structure of O2Sn2F9·0.9HF (2-D). Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Symmetry operations are (i) 2 – x, −1/2 + y, 3/2 – z; (ii) 2 – x, −y, 1 – z; (iii) x, 1/2 – y, 1/2 + z; and (iv) x, 1/2 – y, −1/2 + z.

HF molecules are bound to 2-D grids through F–H···F hydrogen bonds (H···F 1.84 Å, F···F 2.552(7) Å, F···H–F angle 140°). The position of the HF molecule is partially filled, which is likely due to the relative weakness of the above-mentioned hydrogen bonding.

β-O2[Sn2F9] (2-D)

The third product that resulted from the reaction between SnO2 or SnO2/SnF4 mixture and a UV irradiated F2 or O2/F2 mixture in aHF is HF-free O2[Sn2F9] which is denoted by β-O2[Sn2F9] (2-D). Unfortunately, the same problems as those encountered in the case of unsolvated O2GeF5 were observed, i.e., attempts to obtain good quality X-ray diffraction data failed (Table 2). The geometry of the anion is the same as that of solvated O2Sn2F9·0.9HF (2-D), i.e., a layerlike ([Sn2F9]−)∞) anion that is present in both compounds. The formula unit volume of O2Sn2F9 (1-D) is smaller than that of O2Sn2F9 (2-D). For the former, VF.U. = 185.82 Å3 at 200 K, and for the latter, VF.U. = 189.37 Å3 at 150 K (Table 2). Because of better packing, O2Sn2F9 (1-D) should be a more thermodynamically stable product.

Crystal Structure of O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9

The crystal structure of O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9 is isotypic with that of H3O[Cd(HF)]4(SbF6)9.68 It exhibits a complex three-dimensional structure consisting of two crystallographically unique Hg atoms, five crystallographically independent SbF6 groups, and one HF molecule bound to Hg atoms through its F atom. They form a complex framework with O2+ cations located inside the voids (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Unit cell and packing of anions, cations, and HF molecules in the crystal structure of O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9.

The Hg1 and Hg2 atoms both possess a square antiprismatic spheres comprised of seven fluorine atoms belonging to seven SbF6 units and the F atom of the HF molecule. The Hg1–F bond lengths lie in a narrow range, 2.386(5)–2.370(5) Å. The coordination sphere of Hg2 is noticeably distorted; its shape deviates significantly from an ideal square antiprism, and the Hg2–F distances are 2.367(5)–2.451(5) Å.

Four SbF6– anions play a role in μ3-bridging, being bound to three Hg cations in a mer-arrangement, and a SbF6– moiety built up around the Sb5 atom displays a μ4-bridge (Figure 9). The lengths of the terminal Sb–F bonds of the Sb1 to Sb4 polyhedra vary from 1.838(5) to 1.859(6) Å. Notable elongations of Sb3–F33 (1.862(5) Å) and especially Sb4–F43 and Sb1–F13 bonds to 1.868(5) and 1.870(5) Å, respectively, may be attributed to the influence of F–H···F(−SbF5) bond formation (F33···H2, 2.13 Å; F43···H1, 1.99 Å; F13···H2, 2.04 Å). The lengths of bridging Sb–F bonds are 1.891(5)–1.912(5) Å. In the case of the Sb6 coordinating sphere, the two terminal Sb–F bonds, 1.840(8) and 1.862(7) Å, and the bridging Sb–F contacts vary from 1.881(5) to 1.895(5) Å. Each of two HF molecules are bound to the corresponding metal center with Hg–F distances of 2.367(5) and 2.386(5) Å forming rather strong F–H···F hydrogen bonds as noted above. The large increased thermal ellipsoids of oxygen atoms and the short O···O distance of 0.89(2) Å are a consequence of significant orientational disorder of the O2+ cation.

Figure 9.

Part of the crystal structure of O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9 showing the environments of both Hg centers and the O2+ cation. Fluorine atoms around Sb (with the exception of Sb1) atoms are omitted for clarity. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Symmetry operations are (i) −x, 2 – y, 1 – z; (ii) 1 – x, 1 – y, 1 – z; (iii) x, 1 – y, 1/2 + z; (iv) x, −1 + y, z; (v) x, 1 – y, −1/2 + z; (vi) 1/2 – x, 1/2 – y, 1 – z; and (vii) 1/2 – x, 1/2 + y, 1/2 – z.

O2+ Bond Lengths

A list of the O–O bond lengths determined in various O2+ salts (including this work) is given in Table 4.

Table 4. O–O Distances (Å) in O2+ Salts Determined by Single Crystal X-Ray Diffraction Data (O2PtF6 Was Studied Also Using Neutron-Diffraction Data from a Polycrystalline Sample).

| O2+ salt | O–O (Å) | T/K | ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9 | 0.89(2) | 150 | this work |

| O2SbF6 | 0.95 | RT | (22) |

| (O2)2Ti7F30 | 0.96 | 153 | (29) |

| O2GeF5·HF | 1.013(4) | 150 | this work |

| O2H3Pd2F12 | 1.014(4) | 140 | (21) |

| O2Ni(AsF6)3 | 1.018(12) | 173 | (20) |

| O2Sn2F9·0.9HF | 1.046(9) | 150 | this work |

| α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D) | 1.062(14) | 200 | this work |

| O2Mn2F9 | 1.10 | 123 | (30) |

| 0.96 | 293 | (30) | |

| O2RhF6a | 1.1107(16) | 133 | (25) |

| β-O2AuF6 | 0.97 | RT | (22) |

| α-O2AuF6a | 1.079(27) | 104 | (23) |

| 1.068(30) | 151 | (24) | |

| 1.1091(28) | 133 | (25) | |

| O2RuF6 | 1.00 | RT | (22) |

| 1.125(17) | 146 | (26) | |

| 1.12(4) | 298 | (26) | |

| O2PtF6 | 0.91(3)/1.21(17)/1.40b | RT | (27) |

| 0.96 | RT | (22) | |

| free O2+ | 1.1227 | (69) |

Rare examples of O2+ salts with ordered O2+ cations.

From a neutron diffraction study. Various models were tested in an attempt to interpret the experimental data resulting in O–O distances ranging from 0.91 to 1.4 Å. A definitive value for the O–O bond length was not determined, but according to the authors, the model yielding a value of 1.21(17) Å represents the most satisfactory value for the structure of O2PtF6.

The reported O–O bond lengths of O2+ span the absurdly short value of 0.89(2) Å to values close to that observed for the gas-phase O2+ cation (1.1227 Å). Their comparison can be difficult due to the large uncertainty of their values. The determination of O–O bond lengths of O2+ is often problematic because of the partial or complete disorder of the O2+ cation in the crystal structures of O2+ salts. For example, the first reported value for O–O bond length in O2RuF6 was 1.00 Å (at RT).22 A 3-fold disordering of O2+ yielded a more realistic value of 1.12(4) Å (at 298 K).26 Closer inspection of thermal ellipsoids of oxygen atoms in O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9 (Figure 9) reveals unusual enlarged and elongated thermal ellipsoids consistent with oxygen atoms that exhibit static or dynamic disorders. A similar situation occurs in the cases of O2GeF5·HF, α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D), and O2Sn2F9·0.9HF. Applying of libration corrections did not result in significant elongation of O–O bonds. More fruitful was an attempt to split oxygen atom positions in α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D) salt. The resulting O–O distance appears to be more adequate, i.e., 1.06(1) Å instead of 0.97(1) Å, for a model without O2+ disordering.

Conclusions

Photochemical reactions of UV-irradiated O2/F2 mixtures with solid, liquid, or gaseous fluorides, and oxides with UV-irradiated F2 (or O2/F2 mixtures) in anhydrous HF are a convenient way to synthesize O2+ salts (Table 5).

Table 5. List of Reported of O2+ Salts (Including This Work) Together with ν(O2+) Values Recorded by Raman Spectroscopy.

| O2+ salt | ν(O2+)a | crystal structure | ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| molecular O2 | 1580 | (70) | |

| (O2)2NiF6 | 1801 | (37) | |

| (O2)2MnF6 | 1805 | (37) | |

| O2PdF5 | 1820 | (36), this work | |

| O2RhF6 | 1825 | y | (23, 25, 26, 47) |

| β-O2AuF6 | 1835b | y | (24, 47), this work |

| α-O2AuF6 | 1838c | y | (24) |

| O2Mn2F9 | 1838 | y | (30) |

| O2RuF6 | 1838 | y | (22, 26, 47) |

| O2PtF6 | 1838 | y | (16, 17, 22, 27, 44, 47), this work |

| O2V2F11 | 1839 | (71) | |

| O2BiF6 | 1849 | (43, 47) | |

| O2GeF5 | 1849 | yd | (35), this work |

| α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D) | 1849 | y | this work |

| O2Bi2F11 | 1853 | (43) | |

| O2NbF6 | 1853 | (43) | |

| (O2)2Ti7F30 | 1857 | y | (29), This work |

| O2AsF6 | 1858 | (41, 42, 47, 55), this work | |

| O2Nb2F11 | 1858 | (43, 47) | |

| O2Ta2F11 | 1858 | (43, 47) | |

| O2BF4 | 1860 | y | (28), this work |

| O2SbF6 | 1861 | y | (22, 45, 47), this work |

| O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9 | 1861 | y | this work |

| (O2)2Hg2F(SbF6)5 | 1863 | y | (53) |

| O2Sb2F11 | 1864 | (45, 47) | |

| O2Ni(AsF6)3 | 1866 | y | (20) |

| gaseous O2+ | 1876.4 | (69) | |

| O2Pt2F11 | yd | (48) | |

| [O2][H3Pd2F12] | y | (21) | |

| O2AgF4 | yd | (33) | |

| O2GeF5·HF | y | this work |

In addition to those given in Table 5, a few others have been mentioned in the literature. The addition of a solution of highly soluble salts A2PdF6 (A = K, Cs) in aHF to a solutions of O2AsF6 in aHF at −30 °C yield precipitates of AAsF6 and deep orange solutions presumed to contain (O2)2PdF6.36 Attempts to isolate these salts by removal of aHF at −60 °C always resulted in the loss of O2 and F2 and recovery of O2PdF5.36 However, further crystallizations at T < −70 °C resulted in the growth of single crystals of [O2][H3Pd2F12].21 The (O2)2SnF6, O2MoF7 and O2WF7 salts have been reported for the reactions between O2F2 and SnF4 and WF6 or MoF6, respectively.38 However, these reactions are of low yield and poor reproducibility. The compound, O2PF6, slowly decomposes at −80 °C and rapidly at room temperature, giving O2, F2 and PF5.42,73 The existence of O2VF6, O2CrF6, O2Ru2F11, and O2M3F16 (M = Sb, Nb, Ta) still await confirmation.46,71,74 Reported formulation, O2PdF6,75 is most probably O2PdF5,36 whereas O2[CrF4Sb2F11],76 which was claimed to be prepared by oxidation of O2 with CrF5·2SbF5, is in reality a mixture of O2Sb2F11 and CrF4.77

Determination of the single-crystal X-ray structure of O2GeF5·HF showed that its structure consists of infinite polymeric ([GeF5]−)∞ anions, which appear as zigzag single chains of GeF6 octahedra linked by cis-vertices and O2+ cations and HF molecules located between the chains. The ([GeF5]−)∞ anion of O2GeF5 appears to have the same structural motif as that of O2GeF5·HF.

Three different O2+ salts, all containing polymeric ([Sn2F9]−)∞ anions, were isolated and their structured determined. Two of them have the same empirical chemical formula as O2Sn2F9. The anion in α-O2Sn2F9 (1-D) has a chainlike structure, and the anion in β-O2Sn2F9 (2-D) has a layerlike structure. The third phase is the HF solvated form of 2-D O2Sn2F9 (i.e., O2Sn2F9·0.9HF). Besides the layered polymeric ([Sn5F24]4–)∞ anion determined in [XeF5]4[Sn5F24],63 these salts provide new examples of structurally characterized Sn(IV) fluoride compounds which do not only consist of [SnF6]2– anions.

The complex O2+ salt O2[Hg(HF)]4[SbF6]9 was prepared by reaction between O2SbF6, HgF2, and SbF5 in anhydrous aHF. Its crystal structure is isotypic to that of (H3O)[Cd(HF)]4(SbF6)9.68

Experimental Section

Caution! Anhydrous HF and some fluorides are highly toxic and must be handled in a well-ventilated hood, and protective clothing must be worn at all the times.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Commercially available reagents BF3 (Union Carbide Austria GmbH, 99.5%), FeF3 (Alfa Aesar, 97% min), CoF2 (Johnson Matthey GmbH, 99%), TiO2 (Koch-Light Laboratories Ltd., 99.5%), SnO2 (E. Merck AG, Darmstadt, pure), PbO2 (Riedel de Haën), GeF4 (Cerac, Incorporated, 99.99%), NiF2 (Alfa Products, 99.5%), MnF2 (Alfa Aesar, 99%), SnF4 (Alfa Aesar, 99%), SbF3 (Merck KGaA, ≥99%), Pt (Aldrich, ≥99.9%), PtO2 (Aldrich), SeO2 (Fluka AG, Buchs SG, >98%), WO3 (Merck), MoO3 (Merck, 99.5%), WF6 (ABCR, 99%), SbCl5 (Merck, >99%), TiCl4 (Acros Organics, 99.9%), NbCl5 (Alfa Aesar, 99.95%), HCl, and Cl2 were used as supplied. AgF2, AuF3, and Pd2F6 were synthesized by the reaction of AgNO3 (Fisher Chemical), AuCl3 (Alfa Aesar, 99.99%), and Pd sponge (Aldrich 99.9%), respectively, with elemental fluorine F2 (Solvay Fluor and Derivate GmbH, 99.98%) in aHF (Linde AG, Pullach, Germany, 99.995%) at ambient temperature.31 Arsenic pentafluoride was prepared as described previously,78 and IF5 was from our stock. HgF2 was obtained by high temperature (230 °C) static fluorination of HgCl2 (Alfa Aessar, 99.5%) in a 100 mL nickel autoclave.

Synthetic Apparatus

All manipulations were carried out under anhydrous conditions. Nonvolatile materials were handled in a M. Braun glovebox in an argon atmosphere, where the quantity of water did not exceed 0.5 ppm. Gaseous F2, O2, and AsF5 and volatile compounds, such as aHF and WF6, were handled on a vacuum line constructed from nickel and PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene).

Vessels used for syntheses and single-crystal growth were manufactured from tetrafluoroethylene-hexafluoropropylene block-copolymer (FEP; Polytetra GmbH, Germany) tubes. The reaction vessel was comprised of a tube (i.d. 16 mm, o.d. 19 mm) that was heat-sealed on one end and equipped with a PTFE valve on the other flared end. The crystallization vessel consisted of two FEP tubes: one 16 mm i.d. × 19 mm o.d. and the other 4 mm i.d. × 6 mm o.d. Each tube was heat-sealed on one end and attached via linear PTFE connectors to a connecting PTFE T-part at 90°. The PTFE valve was attached to the T-part at 180° to the 19 mm o.d. tube. All PTFE portions of valve were enclosed in brass with threads that prevented deformation of the PTFE portions of the valve and simplified their connection to reaction vessels and to the vacuum system. Magnetic stirring bars, clad in PTFE, were placed inside the reaction vessels. The temperature gradient between the two arms of the crystallization vessels was maintained by cooling a wider arm of a vessel in Huber Ministat 230 (to −33 °C) and Thermo Fisher Scientific EK 90 (to −60 °C) cryostats.

Prior to use, all reaction and crystallization vessels were dried under dynamic vacuum and passivated with elemental fluorine F2 (Solvay Fluor and Derivate GmbH, 99.98%) at 1 bar for 2 h. Anhydrous HF (Linde AG, 99.995%) was treated with K2NiF6 (Advance Research Chemicals Inc., 99.9%) for several hours before use and was usually kept in FEP vessels above K2NiF6.

Synthesis and Crystal Growth

Various amounts (50–200 mg) of solid starting reagents were loaded into reaction vessels inside a drybox (Table S1 in the Supporting Information). Gaseous and liquid reagents were added on a vacuum line. Solvent (HF, 5–10 mL) was condensed onto the reactant at 77 K, and the reaction mixture was warmed to ambient temperature. Fluorine was slowly added to the reaction vessel at ambient temperature until a pressure of 6 bar was attained. A medium-pressure mercury lamp (Hg arc lamp, 450 W, Ace Glass, USA) was used as the UV source.31 The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 1–5 days at ambient temperature. All volatiles were slowly pumped off at ambient temperature. After characterization, the powdered product was transferred to a crystallization vessel where aHF (6–10 mL) was condensed onto the product at 77 K. The solvent and product were warmed to ambient temperature and the resulting clear solution was decanted into the 6 mm o.d. side arm. Evaporation of the solvent from this side arm was carried out by maintaining a temperature gradient of ∼10–20 °C between both tubes for several weeks. Slow distillation of aHF from the 6 mm o.d. tube into the 19 mm o.d. tube resulted in crystal growth inside the 6 mm o.d. tube. Several solutions of dissolved products were allowed to crystallize without prior isolation and characterization.

Crystals were treated in different ways. Some crystals were immersed in perfluorodecalin (melting point 263 K) inside a drybox, selected under a microscope, and mounted on the goniometer head of the diffractometer in a cold nitrogen stream. Others were sealed in quartz capillaries used for the structure determination at room temperature and recording of Raman spectra at several random positions. A special method was applied in order to isolate crystals of O2GeF5·HF that are not stable at ambient temperature. For this, a small portion (1–2 mL) of cold perfluorinated oil (perfluorodecaline C10F18) was injected inside the narrower FEP tube to cover the crystals. After that, crystals covered with cold oil were selected under a microscope and mounted on the goniometer head of the diffractometer in a cold nitrogen stream.

Characterization Methods

Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectra with a resolution of 0.5 cm–1 were recorded at room temperature on a Horiba Jobin Yvon LabRam-HR spectrometer equipped with an Olympus BXFM-ILHS microscope. Samples were excited by the 632.8 nm emission line of a He–Ne laser with a regulated power in the range 20–0.0020 mW, which gave 17–0.0017 mW focused on a 1 μm spot through a 50× microscope objective on the top surface of the sample. Single crystals or powdered material were mounted in the glovebox in previously vacuum-dried quartz capillaries, which were initially sealed with Halocarbon 25-5S grease (Halocarbon Corp.) inside the glovebox and later heat-sealed in an oxygen–hydrogen flame outside the glovebox.

Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction Analysis

Single-crystal X-ray data for O2Sn2F9 (1-D and 2-D), O2Sn2F9·0.9HF, O2GeF5·HF, O2GeF5, and O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9 were collected on a Gemini A diffractometer equipped with an Atlas CCD detector, using graphite monochromated MoKα radiation. The data were treated using the CrysAlisPro software suite program package.79 Analytical absorption corrections were applied to all data sets. The structure of O2Sn2F9 (1-D) was solved using the SHELXS program.80 All other structures were solved using the dual-space algorithm of the SHELXT81 program implemented in the Olex crystallographic software.82 Structure refinement was performed with SHELXL-2014 software.83 The figures were prepared using DIAMOND 4.6 software.84 Hydrogen atoms in the structures of O2Sn2F9·0.9HF, O2GeF5·HF, and O2[Hg(HF)]4(SbF6)9 were placed on ideal positions and refined as the riding atoms with relative isotropic displacement parameters. The common occupancy of atoms belonging to the HF molecule in the O2Sn2F9·0.9HF structure was refined using a free variable.

Crystals of O2GeF5 and O2Sn2F9 (2-D) compounds were of extremely poor quality. In the case of O2Sn2F9 (2-D), the crystal structure was completely solved and refined to a reasonable R-factor value. However, the structure suffers from residual electron densities having peaks that are too high. Only the structural motif was identified in the case of O2GeF5 salt with a very high R-value (∼20%) for the completed model.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency (Research Core Funding No. P1-0045; Inorganic Chemistry and Technology).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03518.

Raman spectra of the products obtained by photochemical reactions of UV-irradiated F2 (or O2/F2 mixture) with solid, liquid, or gaseous fluorides or oxides in anhydrous HF; photos of the yellow solids formed after SbCl5/Cl2/O2 and TiCl4/Cl2/O2/HCl mixtures were irradiated by UV-light; geometries of the ([GeF5]−)∞ anions determined in the crystal structures of O2GeF5·HF and [ClO2][GeF5]; two-dimensional ([Sn2F9]−)∞ and ([Sn5F24]4–)∞ grids with a wavelike conformation found in O2[Sn2F9]·0.9HF and [XeF5]4[Sn5F24] (PDF)

Accession Codes

CCDC 1964935–1964938 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Riddlestone I. M.; Kraft A.; Schaefer J.; Krossing I. Taming the cationic beast: Novel developments in the synthesis and application of weakly coordinating anions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13982–14024. 10.1002/anie.201710782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly N. G.; Geiger W. E. Chemical Redox Agents for Organometallic Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 877–910. 10.1021/cr940053x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson T. J.; Tanzella F. L.; Bartlett N. The preparation and characterization of radical cation salts derived from perfluorobenzene, perfluorotoluene, and perfluoronaphtalene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 4937–4943. 10.1021/ja00276a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shorafa H.; Mollenhauer D.; Paulus B.; Seppelt K. The two structures of the hexafluorobenzene radical cation C6F6●+. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 5845–5847. 10.1002/anie.200900666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Züchner K.; Richardson T. J.; Glemser O.; Bartlett N. The pentafluoropyridine cation C5F5N+. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1980, 19, 944–945. 10.1002/anie.198009441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molski M. J.; Mollenhauer D.; Gohr S.; Paulus B.; Khanfar M. A.; Shorafa H.; Strauss S. H.; Seppelt K. Halogenated benzene cation radicals. Chem. - Eur. J. 2012, 18, 6644–6654. 10.1002/chem.201102960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molski M. J.; Khanfar M. A.; Shorafa H.; Seppelt K. Halogenated benzene cation radicals. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 3131–3136. 10.1002/ejoc.201201691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinnocenzo J. P.; Banach T. E. Dioxygenyl hexafluoroantimonate: a useful reagent for preparing cation radical salts in good yield. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 6063–6065. 10.1021/ja00279a078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinnocenzo J. P.; Banach T. E. Deprotonation of tertiary amine cation radicals. A direct experimental approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 8646–8653. 10.1021/ja00205a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christe K. O.; Schack C. J.; Wilson R. D.; Pilipovich D. Reactions of the (CF3)2NO radical with strong oxidizers. J. Fluorine Chem. 1974, 4, 423–431. 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)85292-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christe K. O.; Wilson R. D.; Goldberg I. B. Some observations on the reaction chemistry of dioxygenyl salts and on the blue and purple compounds believed to be ClF3O2. J. Fluorine Chem. 1976, 7, 543–549. 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)82572-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pernice H.; Willner H.; Eujen R. The reaction of dioxygenyl salts with 13CO. Formation of F13C(O)13C(O)F. J. Fluorine Chem. 2001, 112, 277–281. 10.1016/S0022-1139(01)00512-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L. Removal of xenon and radon from contaminated atmospheres with dioxygenyl hexafluoroantimonate O2SbF6. Nature 1973, 243, 30–32. 10.1038/243030a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L.; Hohorst F. A. Collection of radon with solid oxidizing reagents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1982, 16, 419–422. 10.1021/es00101a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holfter H.; Klapötke T. M.; Schulz A. High energetic materials: reaction of azides with dioxygenyl salts. Propellants, Explos., Pyrotech. 1997, 22, 51–54. 10.1002/prep.19970220111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett N.; Lohmann D. H. Dioxygenyl hexafluoroplatinate(V) O2+[PtF6]−. Proc. Chem. Soc. 1962, 115–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett N.; Lohmann D. H. Fluorides of the noble metals. Part II. Dioxygenyl hexafluoroplatinate(V), O2+[PtF6]−. J. Chem. Soc. 1962, 5253–5261. 10.1039/jr9620005253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett N.; Lohmann D. H. Two new fluorides of platinum. Proc. Chem. Soc. 1960, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless E.; Smith I. C.. Inorganic high-energy oxidizers; Dekker, New York, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Mazej Z.; Goreshnik E. Syntheses and characterization of ANi(AsF6)3 (A = H3O+, O2+, NO+, NH4+, K+, Rb+, and Cs+) compounds. J. Fluorine Chem. 2009, 130, 399–405. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2009.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marx R.; Seppelt K. Structure investigations on oxygen fluorides. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 19659–19662. 10.1039/C5DT02247A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graudejus O.; Müller B. G. Zur kristallstruktur von O2+MF6– (M = Sb, Ru, Pt, Au). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1996, 622, 1076–1082. 10.1002/zaac.19966220623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I.-C.; Seppelt K. Gold pentafluoride: structure and fluoride ion affinity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 3690–3693. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J. F.; Schrobilgen G. J. Structural and vibrational characterization of [KrF][AuF6] and α-[O2][AuF6] using single crystal X-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy and electron structure calculations. J. Fluorine Chem. 2003, 119, 109–124. 10.1016/S0022-1139(02)00220-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drews T.; Supel J.; Hagenbach A.; Seppelt K. Solid state structures of transition metal hexafluorides. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 3782–3788. 10.1021/ic052029f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botkovitz P.; Lucier G. M.; Rao R. P.; Bartlett N. The crystal structure of O2+RuF6– and the nature of O2RhF6. Acta Chim. Slov. 1999, 46, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ibers J. A.; Hamilton W. C. Crystal structure of O2PtF6: a neutron-diffraction study. J. Chem. Phys. 1966, 44, 1748–1752. 10.1063/1.1726934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. N.; Curtis; Goetschel New crystal data on dioxygenyl tetrafluoroborate, O2BF4. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1971, 4, 261–262. 10.1107/S002188987100685X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller B. G. Zur kenntnis von [O2]22+[Ti7F30]2-. J. Fluorine Chem. 1981, 17, 489–499. 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)82255-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller B. G. Zur kenntnis von [O2]+[Mn2F9]−. J. Fluorine Chem. 1981, 17, 409–421. 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)82245-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazej Z. Photochemical Syntheses of Fluorides in Liquid Anhydrous Hydrogen Fluoride. In Modern Synthesis Processes and Reactivity of Fluorinated Compounds; Groult H., Leroux F., Tressaud A., Eds.; Elsevier: London, 2017; p 587. [Google Scholar]

- Plews M. R.; Yi T.; Lee J.; Chan E.; Freeland J. W.; Nordlund D.; Cabana J. Synthesis and X-ray absorption spectroscopy of potassium transition metals fluoride nanocrystals. CrystEngComm 2019, 21, 135–144. 10.1039/C8CE01349G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselev Yu.M.; Popov A. I.; Buharin K. V.; Timakov A. A.; Korobov M. V. Synthesis and properties of dioxygenyl tetrafluorargentate(III) (originally in Russian). Zh. Neorg. Khim. 1988, 33, 3205–3207. [Google Scholar]

- Graudejus O.; Wilkinson A. P.; Bartlett N. Structural features of Ag[AuF4]2 and Ag[AuF6] and the structural relationship of Ag[AgF4]2 and Au[AuF4]2 to Ag[AuF4]2. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 1545–1548. 10.1021/ic991178t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christe K. O.; Wilson R. D.; Goldberg I. B. Dioxygenyl pentafluorogermanate(IV), O2+GeF5–. Inorg. Chem. 1976, 15, 1271–1274. 10.1021/ic50160a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucier G. M.; Shen C.; Elder S. H.; Bartlett N. Facile routes to NiF62–, AgF4–, AuF6–, and PtF6–, salts using O2+ as a source of O2F in anhydrous HF. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 3829–3834. 10.1021/ic971603n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougon R. A.; Christe K. O.; Wilson W. W. Dioxygenyl salts containing double charged mononuclear counterions. J. Fluorine Chem. 1985, 30, 237–239. 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)80892-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bantov D. V.; Suhoverhov V. F.; Mihailov Ju.N. Investigations of reactions between dioxidifluoride with higher fluorides of some elements (originally in Russian). Izv. Sib. Otd. Akad Nauk SSSR, ser. Khim. Nauk. 1968, 2, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mazej Z. Room temperature syntheses of MnF3, MnF4 and hexafluoromanganete(IV) salts of alkali cations. J. Fluorine Chem. 2002, 114, 75–80. 10.1016/S0022-1139(01)00566-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shamir J.; Binenboym J. Photochemical synthesis of dioxygenyl salts. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1968, 2, 37–38. 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)86990-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Šmalc A.; Lutar K. On the photosynthesis of dioxygen(1+) hexafluoroarsenate in the systems O2-F2-AsF5, OF2-AsF5 and O2-OF2-AsF5. J. Fluorine Chem. 1977, 9, 399–408. 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)82172-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young A. R.; Hirata T.; Morrow S. I. The preparation of dioxygenyl salts from dioxygen difluoride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 20–22. 10.1021/ja01055a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A. J.; Falconer W. E.; Griffiths J. E.; Sunder W. A.; Vasile M. J. Syntheses and some properties of dioxygenyl fluorometallate salts. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1974, 1129–1133. 10.1039/dt9740001129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudel S. S.; Kraus F. A facile synthesis of pure O2PtF6. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2015, 641, 2404–2407. 10.1002/zaac.201500616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKee D. E.; Bartlett N. Dioxygenyl salts O2+SbF6– and O2+Sb2F11– and their convenient laboratory syntheses. Inorg. Chem. 1973, 12, 2738–2740. 10.1021/ic50129a050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sunder W. A.; Quinn A. E.; Griffiths J. E. Oxygen analysis of O2MF6 and O2M2F11 salts. J. Fluorine Chem. 1975, 6, 557–570. 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)81693-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J. E.; Sunder W. A.; Falconer W. E. Raman spectra of O2+MF6–, O2+M2F11– and NO+MF6– salts: M = As, Sb, Bi, Nb, Ta, Ru, Rh, Pd, Pt, Au. Spectrochiomica Acta A 1975, 31, 1207–1216. 10.1016/0584-8539(75)80175-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graudejus O.; Krämer O.; Müller B. G., Crystal structure of compounds O2+MF6– (M = Sb, Pt, Ru, Au) and O2+[Pt2F11]−. In 11th European Symposium on Fluorine Chemistry, Bled, Slovenia, September 17–22, 1995; p 179.

- Seppelt K. Molecular Hexafluorides. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 1296–1306. 10.1021/cr5001783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahjoub A.-R.; Seppelt K. The structure of IF8–. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 876–878. 10.1002/anie.199108761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sunder W.A.; Wayda A. L.; Distefano D.; Falconer W.E.; Griffiths J.E. Syntheses and Raman spectra of nitrosyl fluorometallate salts. J. Fluorine Chem. 1979, 14, 299–325. 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)82974-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie I. R.; Livingston K. M. S.; Reynolds D. J.; Ozin G. A. Vibrational spectra of some oxide halides of the transition elements with particular reference to gas-phase and single-crystal Raman spectroscopy. J. Chem. Soc. A 1970, 1210–1216. 10.1039/j19700001210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R.; Müller B. G. Synthesis and structure of the new dioxygenyl-compound. In 15th International Symposium on Fluorine Chemistry, Vancouver, Canada, August 2–7, 1997; p 92.

- Seppelt K. Metal-xenon complexes. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2003, 629, 2427–2430. 10.1002/zaac.200300226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucier G.; Shen C.; Casteel W.J.; Chacon L.; Barlett N. Some chemistry of high oxidation state transition metal fluorides in anhydrous HF. J. Fluorine Chem. 1995, 72, 157–163. 10.1016/0022-1139(94)00401-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski P. J.; Derzsi M.; Mazej Z.; Jagličić Z.; Gaweł B.; Łasocha W.; Grochala W. AgIISO4: A genuine sulfate of divalent silver with anomalously strong one-dimensional antiferromagnetic interactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1683–1686. 10.1002/anie.200906863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallouk T. E.; Desbat B.; Bartlett N. Structural studies of salts of cis and trans μ-fluoro-bridged polymers of GeF5– and of the GeF5– monomer. Inorg. Chem. 1984, 23, 3160–3166. 10.1021/ic00188a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern Y.; Zischka F.; Kornath A. Diprotonation of guanidine in superacidic solutions. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 17311–17317. 10.1002/chem.201803726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazej Z.; Goreshnik E.; Jagličić Z.; Filinchuk Y.; Tumanov N.; Akselrud L. G. Photochemical synthesis and characterization of xenon(VI) hexafluoridomanganates(IV). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 2017, 2130–2137. 10.1002/ejic.201700054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shlyapnikov I. M.; Goreshnik E. A.; Mazej Z. Guanidinium perfluoridotitanate(IV) compounds: structural determination of an oligomeric [Ti6F27]3– anion, and an example of a mixed-anion salt containing two different fluoridotitanate(IV) anions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 2018, 5246–5257. 10.1002/ejic.201801207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shlyapnikov I. M.; Goreshnik E. A.; Mazej Z. Increasing structural dimensionality of alkali metal fluoridotitanates(IV). Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 1976–1987. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlyapnikov I. M.; Goreshnik E. A.; Mazej Z. Syntheses and the crystal chemistry of the perfluoridotitanate(IV) compounds templated with ethylenediamine and melamine. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2019, 489, 255–262. 10.1016/j.ica.2019.02.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazej Z.; Goreshnik A. Crystal structures of photochemically prepared (Xe2F11)2(MF6) (M = Sn, Pb) and (XeF5)4(Sn5F24) containing six- and seven-coordinated tin(IV). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 2019, 1265–1272. 10.1002/ejic.201801558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christe K. O.; Schack C. J.; Wilson R. D. Synthesis and characterization of (NF4)2SnF6 and NF4SnF5. Inorg. Chem. 1977, 16, 849–854. 10.1021/ic50170a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W. W.; Vij A.; Vij V.; Bernhardt E.; Christe K. O. Polynitrogen chemistry: preparation and characterization of (N5)2SnF6, N5SnF5, and N5B(CF3)4. Chem. - Eur. J. 2003, 9, 2840–2844. 10.1002/chem.200304973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christe K. O.; Dixon D. A.; Grant D. J.; Haiges R.; Tham F. S.; Vij A.; Vij V.; Wang T.-H.; Wilson W. W. Dinitrogen difluoride chemistry. Improved syntheses of cis- and trans-N2F2, synthesis and characterization of N2F+Sn2F9–, ordered crystal structure of N2F+Sb2F11–, high-level electronic structure calculations of cis-N2F2, trans-N2F2, F2N = N, and N2F+, and mechanism of the trans-cis isomerization of N2F2. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 6823–6833. 10.1021/ic100471s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christe K. O.; Schack C. J. Chemistry and structure of N2F3+ salts. Inorg. Chem. 1978, 17, 2749–2754. 10.1021/ic50188a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tavčar G.; Mazej Z. Crystal structures of mixed oxonium–cadmium(II) salts with [SbF6] –/ [Sb2F11] – anions: From complex chains to layers and three-dimensional frameworks. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2011, 377, 69–76. 10.1016/j.ica.2011.07.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg G.Molecular spectra and molecular structure. I. Spectra of diatomic molecules; D. Van Noastrand Co., Inc.: Princeton, NJ, 1950; p 560. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock H. D.; Herzberg L. Fine Structure of the Red System of Atmospheric Oxygen Bands. Astrophys. J. 1948, 108, 167–190. 10.1086/145062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J. E.; Edwards A. J.; Sunder W. A.; Falconer W. E. Raman study of the O2F2 + VF5 reaction: isolation and identification of an unstable reaction intermediate. J. Fluorine Chem. 1978, 11, 119–142. 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)81012-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazej Z.; Ponikvar-Svet M.; Liebman J. F.; Passmore J.; Jenkins H. D. B. Nitrosyl and dioxygenyl cations and their salts – similar but further investaigation needed. J. Fluorine Chem. 2009, 130, 788–791. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2009.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon I. J.; Brabets R. I.; Uenishi R. K.; Keith J. N.; McDonough J. M. New dioxygenyl compounds. Inorg. Chem. 1964, 3, 457. 10.1021/ic50013a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon I. J. Kinetics of synthesis and decomposition reactions of ionic compounds containing N-F cations. U.S. Gov. Res. Develop. Rep. 1969, 69, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer W. E.; DiSalvo F. J.; Edwards A. J.; Griffiths J. E.; Sunder W. A.; Vasile M. J. Dioxygenyl hexafluoropalladate(V) O2+PdF6–: a quinquelent compound of palladium. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1976, 28, 59–60. 10.1016/0022-1902(76)80595-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. D.; Loehr T. M.; Gard G. L. The chemistry of chromium pentafluoride II. Reactions with inorganic systems. J. Fluorine Chem. 1976, 7, 19–32. 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)83979-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bougon R.; Wilson W. W.; Christe K. O. Synthesis and characterization of NF4CrF6 and reaction chemistry of CrF5. Inorg. Chem. 1985, 24, 2286–2292. 10.1021/ic00208a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazej Z.; Žemva B. Synthesis of arsenic pentafluoride by static fluorination of As2O3 in a closed system. J. Fluorine Chem. 2005, 126, 1432–1434. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2005.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agilent Technologies. CrysAlisPro, version 1.171.37.31; (release January 1, 2014 CrysAlis171.NET).

- Sheldrick G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2008, A64, 112–122. 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. SHELXT - Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Adv. 2015, A71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov O. V.; Bourhis L. J.; Gildea R. J.; Howard J. A. K.; Puschmann H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. 10.1107/S0021889808042726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, C71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal Impact. Diamond - Crystal and Molecular Structure Visualization, http://www.crystalimpact.com/diamond.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.