Corresponding Author

Key Words: betrixaban, deep vein thrombosis, implementation science, pulmonary embolism, rivaroxaban, venous thrombosis, VTE prevention, VTE thromboprophylaxis

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis during medical or surgical hospitalization occurs almost by rote when patients are admitted for care. Pre-designed order sets pop up on the computer screen, and VTE prophylaxis is often bundled with measures to prevent stomach ulcers or constipation. The system generally works well. Those patients who receive orders for pharmacologic prophylaxis with low-dose low–molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or minidose unfractionated heparin rarely develop major in-hospital deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE). (This is not the case for hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease-2019 [COVID-19], who routinely develop DVT or PE, despite the administration of conventional low-dose anticoagulation. However, this is not the topic of this editorial.)

General and orthopedic surgeons took the lead in developing the concept of in-hospital VTE prophylaxis. Their idea was counterintuitive and initially controversial. Give patients a low dose of injected LMWH or heparin before the surgical incision, and continue prophylaxis for at least 1 week. Fortunately, the benefits of decreased PE and DVT outweighed the risk of major bleeding. In 1986, a decade after the first landmark VTE prophylaxis trial (1), in-hospital VTE prophylaxis for both surgical and medical patients received widespread consensus approval and endorsement at a large consensus conference convened by the National Institutes of Health (2). The clock moved slowly. It took 11 years to garner the credibility of this approach across the health care community.

When surgeons realized that some of their patients who had “perfect” operations had DVT or died of PE within weeks after hospital discharge, they undertook trials of extended-duration VTE prophylaxis after hospital discharge. Patients undergoing major cancer surgery, total hip replacement, and total knee replacement benefited from VTE prophylaxis for approximately 1 month following discharge. Of great importance is that the surgical community rapidly adopted extended-duration VTE prophylaxis as the norm, not the exception. This has not been the case with medical patients.

The narrative is different for medical patients discharged with common diagnoses such as heart failure, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive lung disease. Two anticoagulant drugs have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for extended-duration VTE prophylaxis: betrixaban, in 2017; and rivaroxaban, in 2019. Most health care providers are not familiar with betrixaban, an anti-Xa agent that received FDA approval after the landmark APEX (Acute Medically Ill VTE Prevention With Extended Duration Betrixaban) trial (3). Rivaroxaban, approved by the FDA for extended-duration VTE prophylaxis on the basis of the MAGELLAN (Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis in Medically Ill Patients) trial (4), has not received much uptake for this indication so far. Rivaroxaban was FDA-approved with a caveat that 5 criteria serve as exclusions because of possible major bleeding: 1) active gastroduodenal ulcer; 2) recent bleeding; 3) active cancer; 4) history of severe bronchiectasis or pulmonary cavitation; and 5) dual antiplatelet therapy.

In this issue of the Journal, Spyropoulos et al. (5) publish an important substudy of MARINER (Medically Ill Patient Assessment of Rivaroxaban Versus Placebo in Reducing Post-Discharge Venous Thrombo-Embolism Risk). Their original MARINER study showed that rivaroxaban compared with placebo halved the rate of symptomatic VTE during the first 5 weeks following hospital discharge (6). The current report extends these findings after analyzing 4,909 rivaroxaban-treated patients and 4,913 patients assigned to placebo. In the context of post-hospital VTE prophylaxis, rivaroxaban reduced the combined secondary endpoint of symptomatic VTE, myocardial infarction, nonhemorrhagic stroke, and cardiovascular death by 28%. The individual components of the composite endpoint trended in the same direction, favoring rivaroxaban over placebo, with the exception of myocardial infarction. The number of rivaroxaban versus placebo patients was as follows: symptomatic leg DVT (2 vs. 10), symptomatic nonfatal PE (4 vs. 11), myocardial infarction (13 vs. 8), nonhemorrhagic stroke (13 vs. 24), and cardiovascular death (39 vs. 42).

The theme of reduction of overall cardiovascular events, including VTE, was also observed with betrixaban. A betrixaban substudy of APEX reported a 31% reduction of the combined endpoint of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death compared with standard prophylaxis using enoxaparin, 40 mg daily for 6 to 14 days (7). The findings with rivaroxaban and betrixaban suggest that we should abandon a silo approach for the prevention of venous or arterial thrombosis and promote a holistic strategy to vascular disease.

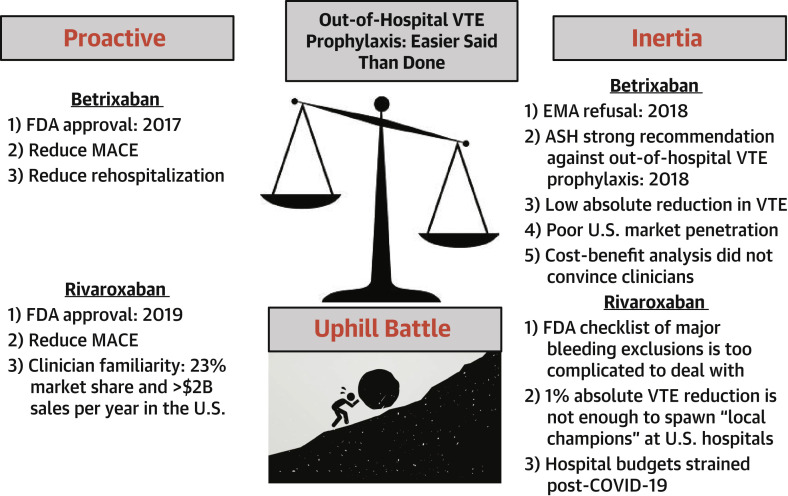

Implementation of the lessons from APEX and MARINER will be an uphill journey (Figure 1 ). The American Society of Hematology guidelines recommend against the use of extended-duration anticoagulant prophylaxis after hospital discharge (8). Those physicians who advocate for out-of-hospital VTE prophylaxis will have to convince their colleagues on the hospital formulary committees. The impression remains that this effort would benefit only a small number of patients with VTE. The report by Spyropoulos et al. (5) in the Journal informs us that VTE outcomes are interwoven with cardiovascular death and stroke outcomes.

Figure 1.

Out-of-Hospital VTE Prophylaxis

It has been challenging to convince U.S. health care providers to “buy in” to the concept of extended-duration venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis after hospitalization for medical illnesses. Multiple factors have favored inertia over proactive champions of out-of-hospital pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. The struggle for implementation appears to be uphill. In Homer’s Odyssey, Sisyphus was punished in Hades by having to repeatedly roll a huge boulder up a hill (clinical trials leading to approval of betrixaban and rivaroxaban by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [FDA]), only to have it roll down again as soon as he had brought it to the summit (inertia prevails). ASH = American Society of Hematology; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease-2019; EMA = European Medicines Agency; MACE = major adverse cardiac event.

Footnotes

Dr. Goldhaber has reported that he has no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. P.K. Shah, MD, served as Guest Editor-in-Chief for this paper.

The author attests they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the author's institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACCauthor instructions page.

References

- 1.Kakkar V.V., Corrigan T.P., Fossard D.P., Sutherland I., Thirwell J. Prevention of fatal postoperative pulmonary embolism by low dose of heparin: an international multicentre trial. Lancet. 1975;306:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevention of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Natl Inst Health Consens Dev Conf Consens Statement. 1986;6:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen A., Harrington R.A., Goldhaber S.Z. Extended thromboprophylaxis with betrixaban in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:534–544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen A., Spiro T.E., Büller H.R. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:513–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spyropoulos A.C., Ageno G.W., Albers G.W. Post-discharge prophylaxis with rivaroxaban reduces fatal and major thromboembolic events in medically ill patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3140–3147. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spyropoulos A.C., Ageno W., Albers G.W. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis after hospitalization for medical illness. N Engl J Med. 2019;379:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nafee T., Gibson C.M., Yee M.K. Reduction of cardiovascular mortality and ischemic events in acute medically ill patients. Circulation. 2019;139:1234–1236. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schünemann H.J., Cushman M., Burnett A.E. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2:3198–3225. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]