Abstract

Obesity is a complex syndrome with multifactorial etiopathogenesis, multifaceted clinical presentations, multidimensional therapeutic approaches, and multipronged treatment strategies. These create the need for a person-centred approach to the management of obesity. This opinion piece explores the spectrum of person-centred obesity care. The authors describe the person-centred nature of techniques used to detect obesity, the thresholds used to diagnose it, the tools (treatment strategies) used to manage it, and the therapeutic outcomes aimed for. The discussion highlights the vast spectrum of obesity and its impact on health, and underscores the need for healthcare professionals to take a person-centred approach to its evaluation and management.

Keywords: BaroSixer, metabolic syndrome, obesity, overweight, patient, centred care, patient satisfaction, SECURED

Obesity, defined as the presence of excess body fat, is a major public health problem which appears to have become endemic to the human race.1 Owing to its multifactorial etiopathogenesis, clinical manifestations and comorbidities, the management of obesity can be more challenging than that of other chronic medical conditions. Although there has been much debate surrounding whether obesity is a disease in itself, or just a contributor to other diseases, obesity does fit the criteria for disease definition and thus has been officially recognised as such by several medical associations, societies and international health organisations.2 The definition and classification of obesity has not been standardised; the criteria used differs according to the geographical location and ethnicity of the patient.3 In addition, the utility of body mass index (BMI) in diagnosing obesity is not an infallible means of assessment.4 The recognition of obesity in patients classified as being of ‘normal weight’ according their BMI, highlights the shortcomings of the measure.5

There is much more to obesity than just a number; the metabolic, musculoskeletal, and psychological functioning associated with body weight all contribute to the impact of obesity on health and quality of life.6 Even those with normal weight who demonstrate cardio-metabolic obesity associations are at greater risk of mortality compared to those who may be obese as defined by their BMI, but have normal metabolic health.7 Patients who fit within the latter category, who do not show metabolic abnormalities such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and dysglycaemia, are often referred to as being ‘metabolically healthy obese’ (MHO).8,9 Several meta-analyses have previously confirmed a positive association between an MHO phenotype and the risk of cardiovascular events, although the precise definition of MHO is yet to be described.8,9

When it comes to treating obesity, modern bariatrics sometimes confuses, rather than clarifies, clinical decision making, and treatment is often associated with unsatisfactory outcomes for those living with obesity, as well as their health care providers.10 Various fad diets, behavioural therapies, unproven medical treatments and aggressive surgical ‘cures’, along with their often-exorbitant expense, all compete for a place in the expanding portfolio of promoted ‘quick-fix’ treatments. The proliferation of such approaches contributes to the confusion surrounding obesity care.10

Person-centred care

Chronic disease management, based upon the biopsychosocial model of health, encompasses the importance of person-centred care. Though person-centred care is followed in various endocrine and metabolic conditions, such as diabetes, hypothyroidism and menopause, its relevance is not highlighted in obesity. The relatively few articles on the person-centred management of obesity focus on the psychosocial aspect of nursing and are limited to case reports or series.11,12

In this editorial, we propose a robust framework to facilitate the use of person-centred techniques and tools, as well as targets and therapies, in obesity. Each person living with obesity is different, thus obesity management should be individualised. Through this discussion, we hope to focus the attention on person-specific needs and to help healthcare providers craft appropriate strategies that are able to fulfil these needs.

Techniques

Person-centred obesity care begins with screening and diagnosis. Conventionally, BMI has been used to evaluate obesity, with ethno-specific value cut-offs for Asia-Pacific populations as proposed by The World Health Organization.3,13 These cut-offs, which are lower than those for Caucasians, reflect a higher risk of metabolic complications at lower BMI levels in this ethnic group. In spite of using these criteria, there is a subset of people with normal weight obesity that can be identified only by measuring body fat composition.4 There may be people who are more concerned about waist circumference, or waist hip ratio, rather than overall weight or BMI.2 It is imperative, therefore, to develop more accurate means of diagnosing obesity. Until this is done, multiple anthropometric and non-invasive markers, including waist circumference and body fat percentage, may be used to ensure person-centric diagnosis.

The ‘4M’ approach

Screening should not be limited to anthropometry alone as obesity can impact the body in various ways. The ‘4M’ approach advocated by Canadian Obesity Association differentiates between metabolic and mechanical (musculoskeletal) dysfunction, and highlights the deleterious impact of weight on financial health. The four ‘M’s are: metabolic, mental, mechanical and monetary factors. The influence of these factors on health varies not only from person to person, but also from time to time and this must be taken into account when planning treatment.14

The Edmonton Obesity Staging System

The Edmonton Obesity Staging System (EOSS) provides a rational and pragmatic means of assessing individuals with obesity. The EOSS grades obesity into Stages 0–4. Stage 0 is indicated in persons with No apparent risk factors, physical symptoms, psychopathology, functional limitations and/or impact on well-being related to obesity. Stage 1 implies the presence of obesity-related subclinical risk factors, and mild physical symptoms, psychopathology, functional limitations and/or impairment of well-being. Stage 2 obesity is defined if established vascular-metabolic and/or psychological obesity-related dysfunction are noted. Stage 3 obesity suggests the presence of end-organ damage (such as myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, significant psychopathology, etc.) and Stage 4 obesity suggests severe, potentially end-stage, obesity-related disabilities.15

EOSS enables a holistic approach to obesity, viewing the person not only through a numerical prism that focuses on weight and waist measurements, but as a whole being, with physical, mental and emotional needs. EOSS highlights both biomedical and psychological aspects of obesity, thus acknowledging the biopsychosocial model of health.

The SECURED model

We propose the SECURED (Severity of obesity, Expected prognosis, Comorbid conditions, Urgency of control, Risk of complications, Environmental factors, Dysfunction & disability) model to manage obesity in a holistic manner. The SECURED model includes a seven-pronged evaluation of weight and its complications, and helps plan an individualised approach to therapy (Table 1). Individuals experiencing severe conditions comorbid to obesity, a high level of dysfunction/disability and/or an urgent need for treatment (e.g., the presence of a life- or organ-threatening complication) justify aggressive management. In contrast, if the expected benefit/lifespan outcome for a patient is poor, if there is a risk of iatrogenic complications, and/or if there are other environmental factors at play, a more cautious approach to treatment may be warranted.

Table 1: SECURED model for person-centred obesity care.

| S | Severity of obesity | Body mass index, waist circumference |

| E | Expected prognosis | Expected life span |

| C | Expected life span | Metabolic, mechanical and mood disturbances |

| U | Urgency of control | Biomedical or psychosocial issues that require early weight control |

| R | Risk of complications | Risk of malnutrition, gall stones, other complications due to rapid weight loss |

| E | Environmental factors | Socioeconomic factors influencing life with obesity |

| D | Dysfunction and disability | Biopsychosocial dysfunction and disability due to obesity |

SECURED is similar in philosophy to EOSS, but it does not try to split patients into separate artificial compartments. As well as the conventional biomedical aspects of obesity, the SECURED approach includes environmental and iatrogenic factors as important aspects to be considered in the management of obesity. The SECURED model encourages the treating physician to perform a risk/benefit analysis prior to planning any intervention and thus acts as an aid to clinical decision making, rather than as a mere classification rubric.

Thresholds and tools

Neither EOSS nor SECURED suggest specific thresholds for diagnosis, therapy initiation, or therapy intensification (Table 2). Using EOSS as a basic framework, however, we suggest the following: EOSS Stages 0 and 1 are targets for primordial and primary prevention, which are best achieved by lifestyle modification and behavioural therapy. EOSS Stage 2 requires secondary prevention, which can be offered through meal replacement and medical weight loss therapies. For EOSS Stages 3 and 4, tertiary prevention is needed. Along with behavioural and medical intervention, bariatric surgery may be required. It must be noted that this suggestion needs to be interpreted by the healthcare provider in the context of the individual patient.15,16 It is also noteworthy that management of any comorbid metabolic, mechanical and mood disorders should continue concurrently and this is often best done in a multi-disciplinary clinic setting.17

Table 2: Person-centred intervention thresholds – suggested scheme.

| Edmonton Obesity Stage | Metabolic, psychological status | Level of prevention | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No risk factors | Primordial | Lifestyle modification |

| 2 | Risk factors present | Primary | Behavioural therapy |

| 3 | Significant complications | Secondary | Medical therapy/surgery |

| 4 | Severe complications | Tertiary | Bariatric surgery |

Targets

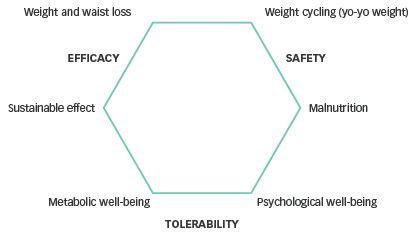

The targets for obesity management should be as person-centred as any proposed treatment. The aim of weight loss is not just to achieve an ideal number. An ideal weight or waist circumference should not represent an end-goal, instead, it is a means of attaining a eumetabolic, eufunctional, euthymic state. In this regard, our suggested model for setting targets, the ‘BaroSixer’ model (Figure 1), mirrors the WHO’s sempiternal definition of health. This hexad, which is similar to existing models in diabetes care, is based upon the game of cricket, in which a ‘sixer’ represents the highest score possible with a single ball.

Figure 1: The ‘BaroSixer’ model for setting targets in obesity management.

The BaroSixer lists six arms of therapy, of these, two are related to efficacy (best achievable weight, best achievable waist circumference), two to safety (avoidance of yo-yo weight pattern/weight cycling and avoidance of malnutrition) and two to tolerability (metabolic wellbeing and psychological wellbeing). Whatever the tools used, our aim should be to score a ‘sixer’ for each person living with obesity. It is important to carry out a realistic assessment of achievable goals; the maximum possible healthy weight loss must be discussed and agreed with the patient, and documented.

Though several guidelines have been published by national and international bodies for the clinical management of obesity, only a few of them emphasise patient-centric management.18–20 A recently published paper by the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) provides a comprehensive algorithm for the personalised management of obesity, for general practitioners.21 Models such as SECURED and BaroSixer would help in the simple and inclusive implementation of such guidelines. Evidence on the utility and impact of using similar structured models is provided from the long term follow-up data following EOSS staging.16

Summary

To summarise, we propose a simplified yet comprehensive approach for the evaluation and management of obesity. The SECURED and the BaroSixer models offer value in managing obese individuals, and may help improve patient satisfaction as well as outcomes. These models should also serve as useful learning tools for obesity care providers of all disciplines.

Funding Statement

Support: No funding was received in the publication of this article.

References

- 1.Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB. et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 Years. N Eng J Med. 2017;377:13–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilov D, Kilov G. Philosophical determinants of obesity as a disease. Obes Rev. 2018;19:41–8. doi: 10.1111/obr.12597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapoor N, Furler J, Paul TV. et al. Ethnicity-specific cut-offs that predict co-morbidities: the way forward for optimal utility of obesity indicators. J Biosoc Sci. 2019:1–3.. doi: 10.1017/S0021932019000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapoor N, Furler J, Paul TV. et al. The BMI-adiposity conundrum in South Asian populations: need for further research. J Biosoc Sci. 2019;51:619–21. doi: 10.1017/S0021932019000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapoor N, Furler J, Paul TV. et al. Normal weight obesity: an underrecognized problem in individuals of South Asian descent. Clin Ther. 2019;41:1638–42. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradshaw PT, Stevens J. Invited commentary: limitations and usefulness of the metabolically healthy obesity phenotype. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182:742–4. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahakyan KR, Somers VK, Rodriguez-Escudero JP. et al. Normal-weight central obesity: implications for total and cardiovascular mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:827–35. doi: 10.7326/M14-2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caleyachetty R, Thomas GN, Toulis KA. et al. Metabolically healthy obese and incident cardiovascular disease events among 3.5 million men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1429–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng R, Zhou D, Zhu Y. The long-term prognosis of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality for metabolically healthy obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70:1024–31. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukhra R, Kaur T, Krishan K, Kanchan T. Overweight and obesity: a major concern for health in India. Clin Ter. 2018;169::e199–201. doi: 10.7417/CT.2018.2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberti di Sarsina P, Iseppato I. Person-centred medicine: towards a definition. Forsch Komplementmed. 2010;17:277–8. doi: 10.1159/000320603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peyrot M, Burns KK, Davies M. et al. Diabetes Attitudes Wishes and Needs 2 (DAWN2): a multinational, multi-stakeholder study of psychosocial issues in diabetes and person-centred diabetes care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:174–84. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults – the evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl. 2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma AM. The 5A model for the management of obesity. CMAJ. 2012;184:1603. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.112-2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez Urbistondo D, Martinez JA. Usefulness of the «Edmonton Obesity Staging System» to develop precise medical nutrition. Rev Clin Esp. 2017;217:97–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rce.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Padwal RS, Pajewski NM, Allison DB, Sharma AM. Using the Edmonton obesity staging system to predict mortality in a population-representative cohort of people with overweight and obesity. CMAJ. 2011;183:E1059–66. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapoor N, Chapla A, Furler J. et al. Genetics of obesity in consanguineous populations – a road map to provide novel insights in the molecular basis and management of obesity. EBioMedicine. 2019;40:33–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM. et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22((Suppl. 3)):1–203. doi: 10.4158/EP161365.GL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH. et al. Pharmacological management of obesity: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:342–62. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM. et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129((25 Suppl. 2)):S102–38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durrer Schutz D, Busetto L, Dicker D. et al. European practical and patient-centred guidelines for adult obesity management in primary care. Obes Facts. 2019;12:40–66. doi: 10.1159/000496183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]