Abstract

Background:

The longevity of a stentless valve in a younger population (20–60 years old) is unknown.

Methods:

From 1992–2015, 1947 patients underwent aortic valve/root replacement for aortic stenosis, insufficiency, root aneurysm or aortic dissection with stentless bioprosthesis (median size: 26 mm). 105 patients were <40, 528 were 40–59, 860 were 60–74, and 454 were ≥75 years at operation. This data was obtained through chart review, administered surveys and the national death index.

Results:

Thirty-day mortality rate was 2.6%. During follow up, 807 (41%) of patients expired before reoperation, 993 (51%) were alive without reoperations due to deterioration and 113 patients (5.8%) underwent reoperation for structural valve deterioration (SVD). After adjusting death and reoperation for non-SVD causes as competing risk, the cumulative incidence of reoperation was significantly different between the younger groups (<40, 40–59) and the older groups (60–74, ≥75) p<0.0001, but not inside the younger (<40 vs 40–59) or older (60–74 vs. ≥75) group. The significant hazard ratio of reoperation for <40 vs ≥75 was 12, <40 vs 60–74 was 4, 40–59 vs 60–74 was 3, and 40–59 vs ≥75 was 9, p≤0.01. The 10-and 15-year survival in the whole cohort was 53% and 29%.

Conclusions:

The stentless aortic valve provides satisfactory durability as a conduit for aortic valve/root replacement for patients who prefer a bioprosthesis. However, it should be judiciously considered for patients <60 years due to increased incidence of reoperation for structural valve deterioration.

Classifications: Aortic valve, Aortic Root Replacement, Reoperation

The majority of stentless valves have been used in elderly patients (> 60 years) [1,3–5] with high freedom of structural valve deterioration (SVD) and reoperation [1,3–5]. There is limited data of the longevity of stentless valves in younger patients between ages 20–60 years. Limited reports with small numbers of patients younger than 60 years showed there was no significant difference of the reoperation rate between elderly patients (>60–65 years old) and younger patients (<60 years old) [5–7]. However, a recent study demonstrated that SVD developed earlier in younger patients, with a SVD rate of 57% at 15 year follow up in patients less than 40 years old [8].

In this study, we examined the long-term survival, the risk factors for reoperation for structural valve deterioration, and the risk factors for all-time mortality after surgery over a 23-year span for the Freestyle bioprosthetic valve (Medtronic Inc. Minneapolis, MN) in 1,947 patients with 633 patients < 60 years of age. It is known that stented bioprostheses have a higher risk of SVD and reoperation in younger people [9]. We hypothesize patient’s age has a negative impact on the longevity of the stentless valve; the younger the patients, the higher the risk of reoperation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Michigan Medicine and a waiver of informed consent was obtained.

Patient Selection

Between 1992 and 2015, 1,947 patients underwent aortic valve or aortic root replacement with first-time use of Freestyle stentless bioprosthetic valve. Indications for operation were aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency, aortic dissection, or root aneurysm. Patients undergoing replacement due to endocarditis were excluded from the study. Patients were divided into 4 age groups: <40 (n=105), 40–59 (n=528), 60–74 (n=860), and ≥75 (n=454).

Data Collection

Data was obtained from Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) from Michigan Medicine’s Cardiac Surgery Data Warehouse to identify study cohort and to determine peri-operative characteristics. Data collection was supplemented with medical record review. Events of reoperation included surgical aortic valve replacement or transcatheter aortic valve replacement for all aortic valve/aortic root pathology, such as: valve deterioration, prosthetic valve endocarditis, root aneurysm/pseudoaneurysm and thrombosis of the stentless valve. All living patients with a known address (n=1354) were mailed a questionnaire or contacted by phone through December 2015. Survival was obtained through the National Death Index database through December 31, 2015[10], as well as medical record review and questionnaire response.

Operative Technique

The operative indications were: aortic stenosis (1168, 60%), aortic insufficiency (393, 20%), aortic root aneurysm (227, 12%), or aortic dissection (101, 5%). All patients underwent primary replacement of the aortic valve/root with a Freestyle bioprosthesis conduit. Operative implantation of the Freestyle valve was completed through the following mechanism: subcoronary (12, 0.6%), modified inclusion or root inclusion (1812, 93%), total root replacement (60, 3.1%), or undocumented (63, 3.2%). The inclusion technique was to implant the whole Freestyle root inside the native aortic root. The proximal suture line was to sew the sewing ring of the Freestyle root to the basal ring of native aortic root with 2–0 ethabond in interrupted fashion. Two holes were created at the left and right coronary sinuses and the coronary ostia were implanted as end-to-side fashion. The Freestyle root and native root matched at the sinotubular junction and anastomosed together as distal suture line. Less than 1% cases were done with inclusion technique. Modified inclusion technique is to scallop the left and right coronary sinuses of the Freestyle root. The coronary artery implantation was slightly easier in modified inclusion technique than inclusion technique since the left and right coronary sinuses of Freestyle root were resected. Total root replacement was performed as a Bentall procedure. The Freestyle root was rotated 120-degrees clockwise. The sewing ring of the Freestyle root was anastomosed to the aortic valve annulus with pledgeted 2–0 ethabond sutures in interrupted horizontal mattress fashion around the annulus in an everting suture fashion. Two coronary arteries were implanted as individual buttons in an end-to-end fashion. The subcoronary implantation and modified inclusion were used for aortic valvulopathy needing valve replacement only. Modified inclusion was also used for non-coronary sinus dilation, such as in patients with bicuspid aortic valve, or to enlarge the aortic root by incising the non-coronary sinus and implanting a larger valve size. The inclusion root was used in type A aortic dissections. Total root was used mainly for aortic root aneurysms, especially in patients with connective tissue disease.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) for continuous data and as number (%) for categorical data. For comparisons of categorical variables across age groups, chi-square tests or fisher exact tests were used accordingly to the expected cell counts. For comparisons of continuous variables across age groups, kruskal-wallis rank sum tests were used when variables were not normally distributed. The normality distribution of continuous variables was checked with Shapiro-Wilk tests. Bonferroni correction was used to adjust multiple comparisons in the descriptive tables. Kaplan-Meier method was used for crude survival curves estimate for time to death since primary operation. The log-rank test was used to compare survival between groups. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to calculate the adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence interval for survival by adjusting for age, gender, primary indication, COPD, hypertension, previous cardiac surgery, preoperative congestive heart failure, renal failure on dialysis, and coronary artery disease. In the COX model for death, preoperative congestive heart failure, renal failure on dialysis, and coronary artery disease violated the assumption of proportional hazard and were used as strata. Adjusting for death and reoperation for other reasons as a competing risk factor, cumulative incidence (CI) curves were generated to assess reoperation rates for SVD over time. Cause-specific Cox regression model was used to assess the risk factor for reoperation including age, gender, primary indications for initial operation, renal failure on dialysis, hypertension, and bicuspid aortic valve. Proportional hazard assumptions were checked and passed in this COX model for reoperation. P values of less than 0.05 (2-tailed) were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic and Preoperative Data

The patients were predominantly male with median age of 66 years. The older two groups of patients had more hypertension, diabetes mellitus, CAD, COPD, but less BAV; more previous CABG, but less aortic or aortic valve surgery compared to the younger two groups. (Table 1, Supplemental Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Preoperative Outcomes

| Variables | Total Stentless Valve Replacement | Age | p-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <40 | 40–59 | 60–74 | ≥75 | |||

| (n=1947) | (n=105) | (n=528) | (n=860) | (n=454) | ||

| Gender (female) | 606 (31) | 30 (29) | 121 (23) | 263 (31) | 192 (42) | <0.001 |

| Pre-existing Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 1240 (64) | 30 (29) | 269 (51) | 603 (70) | 338 (74) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 352 (18) | 5 (5) | 62 (12) | 192 (22) | 93 (21) | <0.001 |

| CAD | 753 (39) | 4 (3.8) | 125 (24) | 380 (44) | 244 (54) | <0.001 |

| CHF | 889 (46) | 54 (51) | 235 (45) | 389 (45) | 211 (47) | 0.599 |

| COPD | 328 (17) | 10 (9.5) | 60 (11) | 177 (21) | 81 (18) | <0.001 |

| Renal Failure on Dialysis | 30 (1.5) | 3 (2.9) | 9 (1.7) | 17 (2) | 1 (0.2) | 0.055 |

| BAV | 719 (37) | 70 (67) | 285 (54) | 284 (33) | 80 (18) | <0.001 |

| Marfan Syndrome | 13 (0.7) | 1 (1) | 9 (1.7) | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.0039 |

| LVEF | 0.004 | |||||

| >60% | 709 (36) | 32 (30) | 181 (34) | 322 (37) | 174 (38) | |

| 40–60% | 972 (50) | 60 (57) | 275 (52) | 430 (50) | 207 (45) | |

| 20–40% | 191 (9.8) | 8 (7.6) | 53 (10) | 75 (8.7) | 55 (12) | |

| <20% | 75 (3.9) | 5 (4.8) | 19 (3.6) | 33 (3.8) | 18 (4.0) | |

| Previous Cardiac Surgery | ||||||

| AV Replacement | 148 (7.6) | 17 (16) | 46 (8.7) | 70 (8.1) | 15 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| AV Repair | 22 (1.1) | 9 (8.6) | 11 (2.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Aortic Root Replacement | 53 (2.7) | 6 (5.7) | 23 (4.4) | 18 (2.1) | 6 (1.3) | 0.004 |

| Ascending Aorta or Arch Replacement | 28 (1.4) | 2 (1.9) | 17 (3.2) | 6 (0.7) | 3 (0.7) | 0.001 |

| CABG | 164 (8.4) | 1 (1.0) | 26 (4.9) | 92 (11) | 45 (9.9) | <0.001 |

Data presented as median (25 %, 75 %) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data. P-value < 0.05 defined as statistically significant difference between the four age groups. Abbreviations: AV, aortic valve; Asc, BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

After Bonferroni correction, p<0.003 was considered significant.

Intraoperative Data

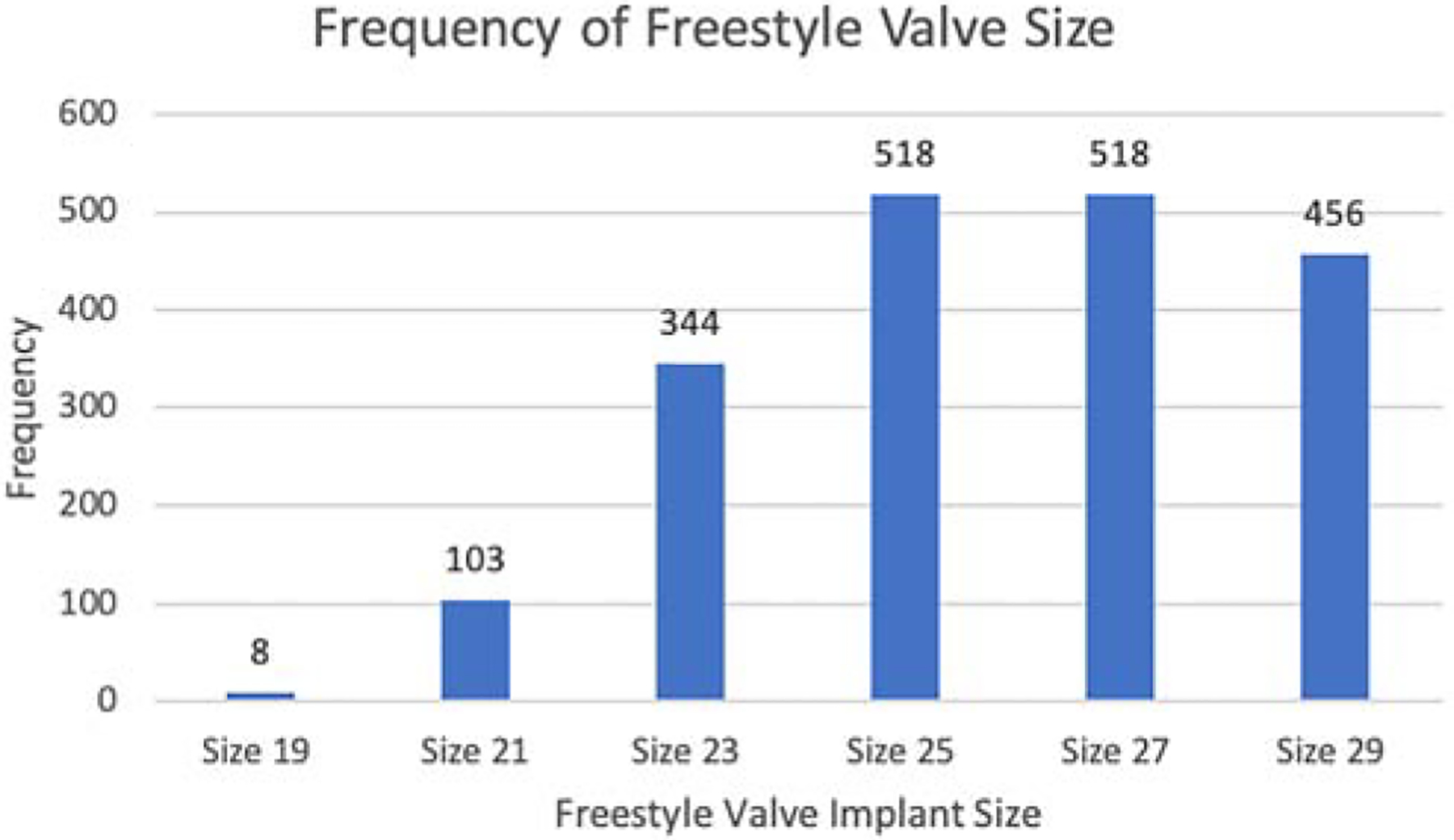

The modified inclusion procedure was the most frequently used technique of implantation (93%) with median size of 26 mm. (Figure 1). The implanting technique of the Freestyle valve was not different among the four groups. (Table 2).

Figure 1:

The distribution of the size of Freestyle valve implanted.

Table 2.

Intraoperative Outcomes

| Variables | Stentless Valve Replacement | Age | p-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <40 | 40–59 | 60–74 | ≥75 | |||

| (n=1947) | (n=105) | (n=528) | (n=860) | (n=454) | ||

| Primary Indication for Operation | <0.001 | |||||

| Aortic Insufficiency | 393 (20) | 41 (39) | 140 (27) | 157 (18) | 55 (12) | |

| Aortic Stenosis | 1168 (60) | 38 (36) | 260 (49) | 522 (61) | 348 (77) | |

| Aortic Root Aneurysm | 227 (12) | 10 (9.5) | 83 (16) | 107 (12) | 27 (5.9) | |

| Aortic Dissection | 101 (5) | 9 (8.6) | 35 (6.6) | 45 (5.2) | 12 (2.6) | |

| Unknown | 58 (3) | 7 (6.7) | 10 (1.9) | 29 (3.4) | 12 (2.6) | |

| Concomitant Procedures | ||||||

| CABG | 429 (22) | 1 (1) | 69 (13) | 236 (27) | 123 (27) | <0.001 |

| Mitral Valve Surgery | 186 (9.6) | 5 (4.8) | 45 (8.5) | 76 (8.8) | 60 (13) | 0.012 |

| Tricuspid Valve Surgery | 70 (3.6) | 1 (1.0) | 17 (3.2) | 36 (4.2) | 16 (3.5) | 0.361 |

| Ascending Aorta or Arch Replacement | 769 (40) | 51 (49) | 254 (48) | 352 (41) | 112 (25) | <0.001 |

| CPB Time (minutes) | 181 (149, 223) | 170 (149, 210) | 180 (153, 220) | 184 (150, 229) | 177 (143, 214) | 0.015 |

| Clamp Time (minutes) | 144 (117, 179) | 138 (115, 171) | 146 (121, 179) | 147 (119, 183) | 139 (112, 173) | 0.005 |

| Blood Transfusion, PRBC (units) | 2 (1, 4) | 2 (0,3) | 2 (0,4) | 2 (1,5) | 4 (2,5) | <.0001 |

| 0 | 691 | 55(52.4) | 257 (48.7) | 294 (34.2) | 85 (18.7) | <.0001 |

| 1–2 units | 460 | 25 (23.8) | 123 (23.3) | 213 (24.8) | 99 (21.8) | |

| 3–4 units | 404 | 14 (13.3) | 73 (13.8) | 167 (19.4) | 150 (33.0) | |

| > 4 units | 392 | 11 (10.5) | 75 (14.2) | 186 (21.6) | 120 (26.4) | |

| Implant Size (mm) | 26 (25, 27) | 27 (25, 29) | 27 (25, 29) | 25 (25, 27) | 25 (23, 27) | <0.001 |

| Technique of Freestyle | 0.441 | |||||

| Modified Inclusion | 1812 (93) | 98 (93) | 494 (94) | 792 (92) | 428 (94) | |

| Total Root | 60 (3.1) | 3 (2.9) | 21 (4.0) | 28 (3.3) | 8 (1.8) | |

| Subcoronary | 12 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.4) | 7 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Unknown | 63 (3.2) | 3 (2.9) | 11 (2.1) | 33 (3.8) | 16 (3.5) | |

Data presented as median (25 %, 75 %) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data. P-value < 0.05 defined as statistically significant difference between the four age groups. Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; PRBC, packed red blood cells.

After Bonferroni correction, p<0.0045 was considered significant.

Perioperative Outcomes

The operative mortality was 3.3% and not significantly different among the groups. The older two groups had longer ventilation time and higher rate of atrial fibrillation. (Table 3). The risk factors for operative mortality were female, acute type A aortic dissection, and preoperative CAD, COPD, and renal failure. (Supplemental Table 1)

Table 3.

Postoperative Outcomes

| Variables | Stentless Valve Replacement | Age | p-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <40 | 40–59 | 60–74 | ≥75 | |||

| (n=1947) | (n=105) | (n=528) | (n=860) | (n=454) | ||

| Hours to Extubation | 11 (5, 18) | 1 (1, 380) | 241 (1, 542) | 291 (11, 571) | 314 (112, 601) | <0.001 |

| Reoperation for Bleeding/Tamponade | 77 (4.0) | 5 (4.8) | 18 (3.4) | 31 (3.6) | 23 (5.1) | 0.503 |

| MI | 8 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 5 (1.1) | 0.13 |

| CVA | 40 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.9) | 20 (2.3) | 15 (3.3) | 0.026 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 718 (37) | 10 (9.5) | 150 (28) | 340 (40) | 218 (48) | <0.001 |

| CHB or Pacemaker | 81 (4.2) | 6 (5.7) | 19 (3.6) | 35 (4.1) | 21 (4.6) | 0.725 |

| Post-op Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 1 (0.8, 1.1) | 1 (0.9, 1.2) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) | <0.001 |

| New Onset Renal Failure | 64 (3.3) | 5 (4.8) | 20 (3.8) | 51 (5.9) | 18 (4.0) | 0.235 |

| 30-day Mortality | 51 (2.6) | 1 (1) | 7 (1.3) | 23 (2.7) | 19 (4.2) | 0.028 |

| Operative Mortality | 65 (3.3) | 3 (2.9) | 11 (2.1) | 31 (3.6) | 20 (4.4) | 0.217 |

Data presented as n (%) for categorical data. P-value <0.05 defined as statistically significant difference between the four age groups.

Abbreviations: CHB, complete heart block; CVA, cerebral vascular accident; MI, myocardial infarction. We used standard STS definition for all complications. Operative Mortality defined as death in hospital or death within 30 days after procedure.

After Bonferroni correction, p<0.005 was considered significant.

Long term Outcomes

Reoperation

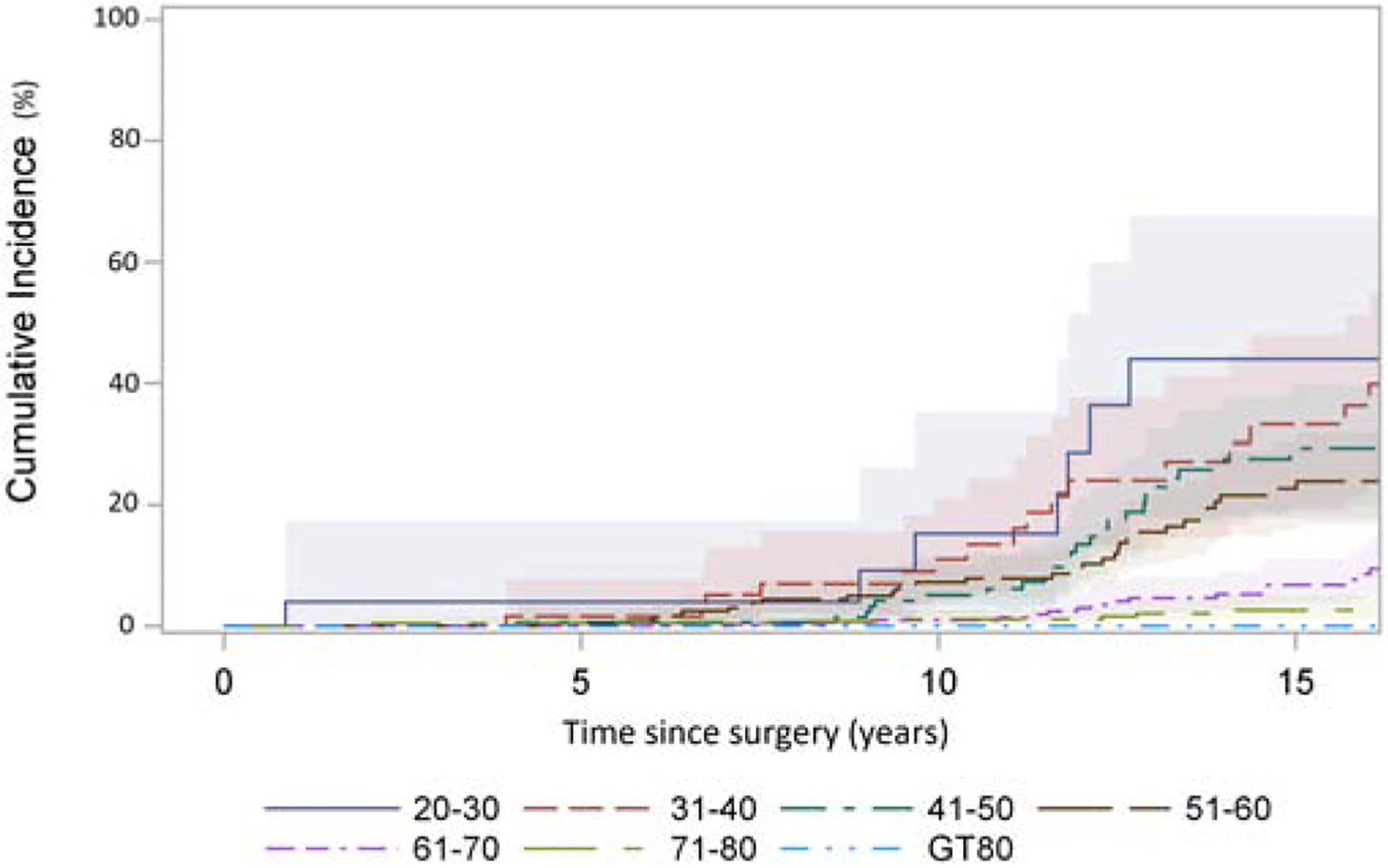

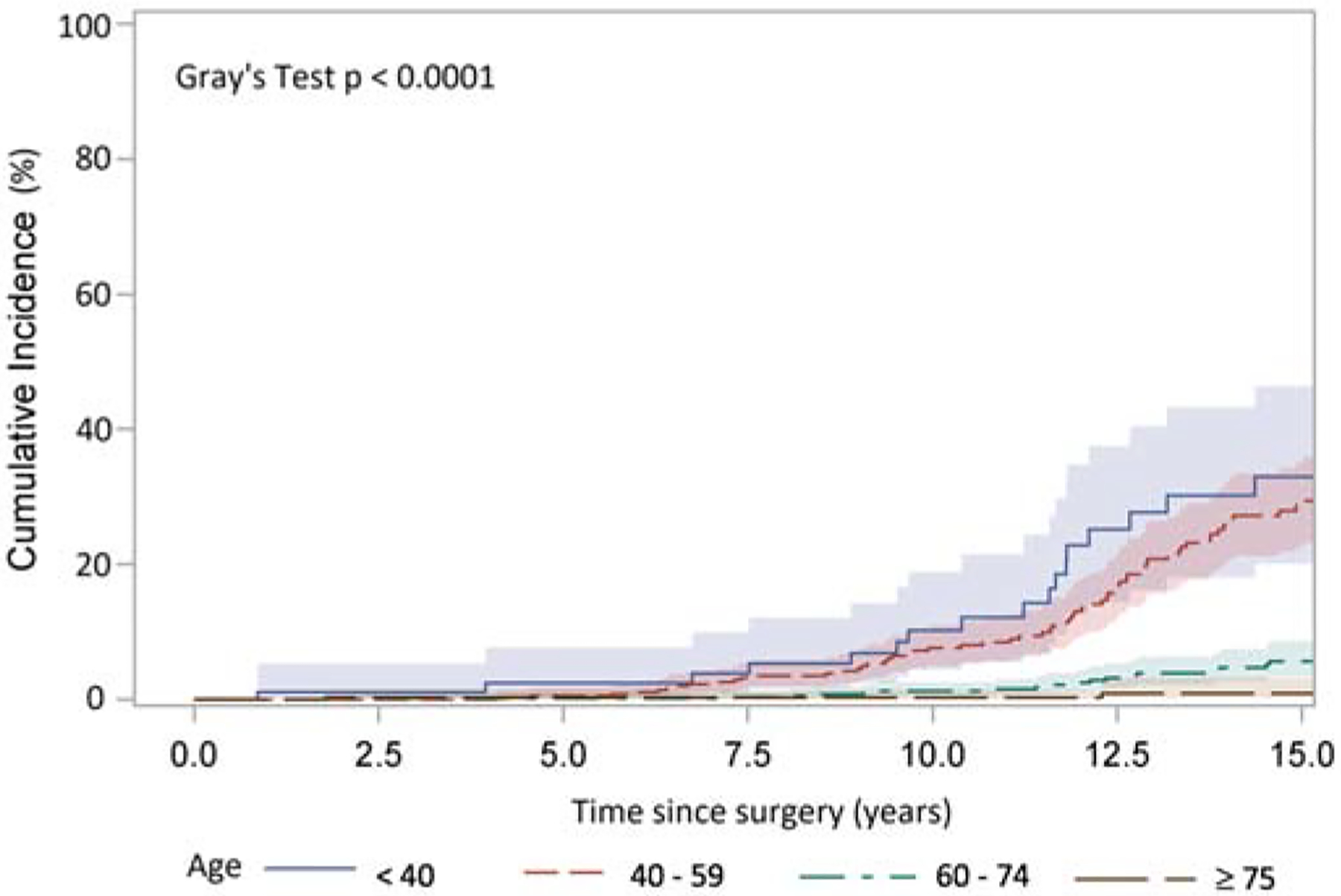

In the total cohort (n=1,947), 77% (n=1,504) had known information regarding reoperation. During our follow up period, we identified 147 patients had reoperation, 807 patients expired, and 993 patients were alive without any reoperation until their last follow up time. In patients with known status of reoperation, 113 were due to SVD and 34 due to non-SVD related causes such as endocarditis, thrombosis, aneurysm/dissections, or were unknown. There was no significant difference in CI of reoperation by age cohort younger than 60 (20–30 vs. 31–40 vs. 41–50 vs. 51–60, or <40 vs. 40–59, p>0.05) , but there was a significant difference between age groups <40 or 40–59 vs. 60–74 or ≥75 (all p≤0.003). (Figure 2A, 2B). The CI of reoperation at 10 years for patients <40 was 12%, 40–59 7.6%, 60–74 1.2%, and ≥75 years at operation 0.9%. (Figure 2B). The hazard ratios for reoperation were significant for age groups and BAV. (Table 4).

Figure 2:

Cumulative incidence (CI) of reoperation after implantation of Freestyle valve in different age group adjusting death and reoperation for other reasons as a competing factor. A: patients grouped by age with incremental of 10 years: 20–30(28 patients), 31–40(90 patients), 41–50(204 patients), 51–60(353 patients), 61–70(574 patients), 71–80(537 patients), and >80(161 patients). Among the patients <60 years, there was no significant difference in CI of reoperation by age cohort (20–30 vs. 31–40 vs. 41–50 vs. 51–60). There was significant difference of CI in patients of 51–60 vs. 61–70, p<0.0001, 61–70 vs. 71–80, p<0.01, but no significant difference 71–80 vs. >80 years. B: patients grouped by age <40 years (105 patients), 40–59 years (528 patients), 60–74 years (860 patients), and ≥75 (454 patients) years. There was significant difference in CI of reoperation in patients of age <40 vs 60–74 p<0.0001, <40 vs ≥75 p=0.001, 40–59 vs 60–74 p<0.0001, and 40–59 vs ≥75 p=0.003, but no significant difference between <40 vs 40–59, and 60–74 vs ≥75.

Table 4:

Risk factors for reoperations.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| <40 vs 40–59 | 1.35 | 0.80–2.28 | 0.26 |

| <40 vs 60–74 | 4.07 | 2.14–7.73 | <.0001 |

| <40 vs ≥75 | 11.6 | 2.59–51.65 | 0.001 |

| 40–59 vs 60–74 | 3.01 | 1.85–4.89 | <.0001 |

| 40–59 vs ≥75 | 8.55 | 2.04–35.88 | 0.003 |

| 60–74 vs ≥75 | 2.84 | 0.66–12.16 | 0.16 |

| BAV | 2.03 | 1.30–3.16 | 0.002 |

| Female Gender | 0.75 | 0.48–1.18 | 0.21 |

| Hypertension | 0.93 | 0.62–1.41 | 0.74 |

| Dialysis | 3.51 | 0.46–26.6 | 0.22 |

| Aortic Insufficiency* | 0.80 | 0.51–1.26 | 0.34 |

| Root Aneurysm* | 1.18 | 0.69–2.01 | 0.55 |

| Acute Type A Aortic Dissection* | 0.69 | 0.27–1.77 | 0.44 |

Reference group: Aortic Stenosis

Abbreviations: BAV: bicuspid aortic valve

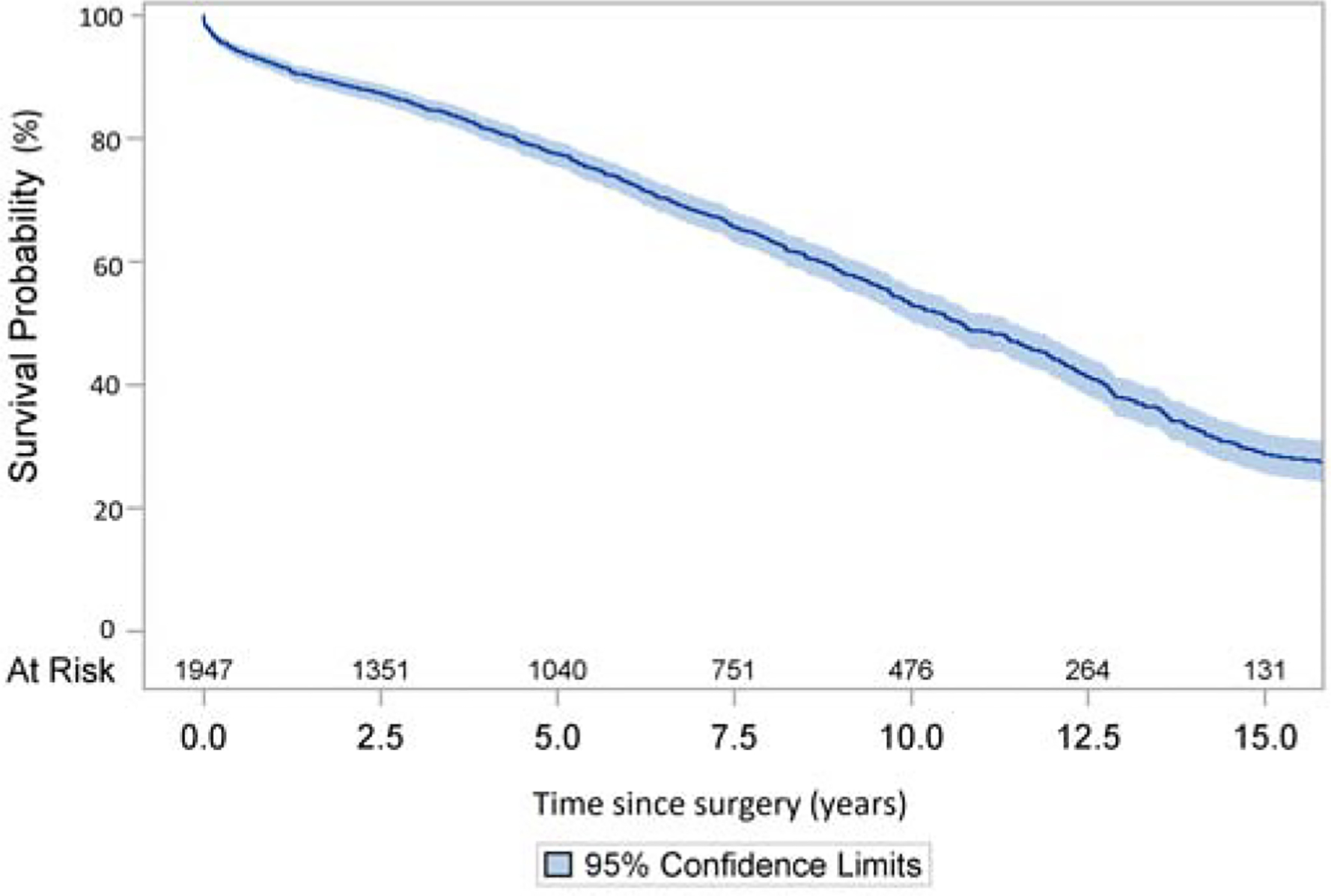

Long-term survival

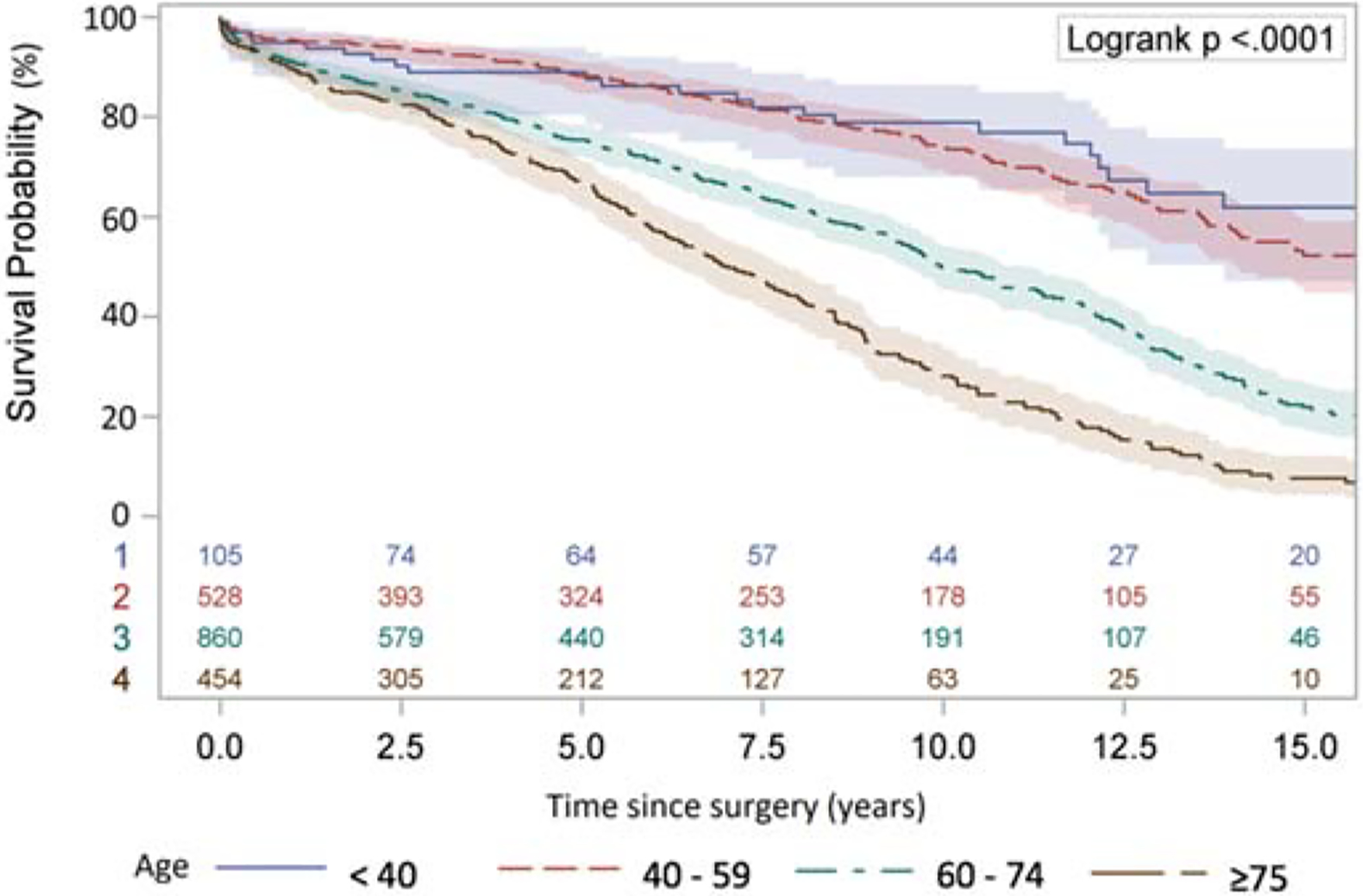

The follow-up time was 6.3±5.1 years. The Kaplan-Meier 10- and 15-year survival for the whole cohort was 53% and 29%. (Figure 3A), which decreased significantly in the two older age groups. (Figure 3B, Supplemental Figure 3). The risk factors of late mortality after surgery included age, aortic dissection, aortic stenosis as primary indication compared to aortic insufficiency or aortic root aneurysm, COPD, hypertension, and previous cardiac surgery. (Table 5).

Figure 3:

Long-term survival (Kaplan-Meier analysis) of patients with aortic valve replacement with Freestyle Bioprosthesis. A: The whole cohort. B: Separate cohorts divided by age <40, 40–59, 60–74, and ≥75.

Table 5:

Risk factors for late mortality

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| <40 vs 40–59 | 0.78 | 0.50–1.20 | 0.26 |

| <40 vs 60–74 | 0.42 | 0.27–0.64 | <0.0001 |

| <40 vs ≥75 | 0.25 | 0.16–0.38 | <0.0001 |

| 40–59 vs 60–74 | 0.54 | 0.44–0.66 | <0.0001 |

| 40–59 vs ≥75 | 0.32 | 0.26–0.39 | <0.0001 |

| 60–74 ≥75 | 0.60 | 0.51–0.70 | <0.0001 |

| Female Gender | 1.15 | 0.99–1.33 | 0.07 |

| Aortic Insufficiency* | 0.74 | 0.61–0.91 | 0.005 |

| Root Aneurysm* | 0.66 | 0.51–0.86 | 0.002 |

| Acute Type A Aortic Dissection* | 1.21 | 0.86–1.70 | 0.27 |

| COPD | 1.75 | 1.47–2.08 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1.22 | 1.05–1.42 | 0.01 |

| Previous Cardiac Surgery | 1.65 | 1.38–1.97 | <0.0001 |

Reference group: Aortic Stenosis.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

COMMENT

In this study, we found the operative mortality rate (3.3%) for freestyle implantation was low. The 10-year and 15-year survival were 53% and 29%. The CI of reoperation for SVD was significantly different between the younger (<40, 40–59) and older (60–74, ≥75) groups, but not inside the younger (<40 vs. 41–59) or older (60–74 vs. ≥75) groups. (Figure 2, Table 4).

Although stentless valve has better hemodynamics than stented valve, it is not popularly used. One of the reasons is that the implantation of stentless valve is more complex than stented valve. No matter which stentless technique (inclusion/modified inclusion or total root replacement) is used there are additional suture lines required and coronary artery reimplantation. Our operative mortality rate (3.3%) appears comparable with other studies in the literature which include 300 or more cases whose mortality rate ranges from 3.4 to 8% [7,11,12,13], though our study did not include patients with endocarditis. The incidence of complete heart block requiring pacemaker in our study was 4%, which was half of the reported incidence [4]. Our results show Freestyle valve implantation can be performed with good outcomes. The mortality rate of reoperation for degenerated or infected stentless valve is also low (1–2%) at our center [2]. However, the implantation of a stentless valve and the reoperation are both definitely more complex than those for a stented valve.

The overall 10- and 15-year survival in the whole cohort was 53% and 29%, which is consistent with other reports in the literature [3,4,14,15]. Compared to patients with aortic insufficiency or aortic root aneurysm as primary indication for aortic valve replacement, patients with aortic stenosis as primary indication had a significantly higher risk (1.4 or 1.5 times higher, respectively) of late mortality after Freestyle valve implantation, which was similar to the risk of late mortality in patients with acute type A aortic dissection. (Table 5). This finding suggested that aortic stenosis patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy may have more difficulty with ventricular remodeling and recovery than a dilated cardiomyopathy resulting from aortic insufficiency or no cardiomyopathy in patients with an aortic root aneurysm and mild/moderate valve pathology. We have followed the appropriate AHA/ACC guidelines over time for the treatment of aortic stenosis, which include severe symptomatic aortic stenosis or asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis with decreased left ventricular ejection fraction, development of pulmonary hypertension or critical aortic stenosis [16]. Those conditions indicate end stage aortic stenosis with a severely damaged left ventricle. Based on current AHA/ACC guidelines, we might be too late for replacing the stenotic aortic valve to allow for the ventricular recovery.

It was not surprising that younger patients had a higher CI of reoperation due to SVD (Figure 3A and 3B) during follow-up after surgery, which was similar to what is reported in the literature [3]. Surprisingly, the CI was very obvious between the patients <60, and >60, but not among patients <60. (Figure 2B). Even in the patients between 20–30 years of age, the 10-year cumulative risk was <20% and only 7.8% for all patients <60 years of age (Figure 2A, Supplemental Figure 2). This finding suggests Freestyle valve could be a valid choice for patients younger than 40, especially as it does provide better hemodynamics.

The most common mechanism for structural valve deterioration is fracture of the cusps resulting in aortic insufficiency [2,3]. Unlike a living aortic valve, the Freestyle valve is a processed non-living porcine aortic valve that cannot repair itself. Compared to older patients, younger patients are more active, have higher heart rates and can generate greater dynamic forces with each heartbeat, which may cause earlier degeneration necessitating a shorter time span until reoperation. Another interesting finding was that bicuspid aortic valve was an independent risk factor for SVD compared to trileaflet aortic valve. This mechanism remains unknown.

Our study has limitations as a retrospective study. The follow-up for the reoperation was not 100%, which could underestimate the cumulative incidence of reoperation. However, the majority of patients who had Freestyle valves implanted at our institution are followed long term in our aortic clinic. They are educated on Freestyle durability and therefore had their degeneration diagnosed early in its course and underwent reoperation. The CI of reoperation we used in this study would underestimate the rate of SVD of the Freestyle valve. Additionally, we only included patients without endocarditis.

In conclusion, implantation of a Freestyle valve can be safely performed with low operative mortality. The age inversely affects the longevity of the Freestyle aortic valve. We should be cautious when offering a Freestyle valve to patients <60 years of age when they need aortic valve/root replacement. However, in younger patients who cannot have a mechanical valve for medical reasons which prohibit long term anticoagulation or are not willing or responsible enough to take anticoagulation, the Freestyle valve is still a good option.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Whole cohort age distribution at time of operation

Supplemental Figure 2: Cumulative incidence (CI) of reoperation after implantation of Freestyle aortic valve in patients younger or equal to 60 years and older than 60 years. The cumulative incidence of reoperation was significantly higher in patients <60 years (n=675) compared to patients older than 60 (n=1272) at 10 and 15 years. (7.8% vs. 1.1% and 27.7% vs 4.4%, respectively, p<0.0001).

Supplemental Figure 3: Long-term survival (Kaplan-Meier analysis) of patients with aortic valve replacement with Freestyle Bioprosthesis in patients ≤60 and >60 years.

Supplemental Table 1: Logistic model for operative mortality.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bach DS, Kon ND, Dumesnil JG, Sintek CF, Doty DB. Ten-Year Outcome After Aortic Valve Replacement with the Freestyle Stentless Bioprosthesis. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;80:480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang B, Patel HJ, Norton EL, et al. Aortic Valve Reoperation After Stentless Bioprosthesis: Short- and Long-Term Outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;106:521–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohammadi S, Tchana-Sato V, Kalavrouziotis D, et al. Long-term clinical and echocardiographic follow-up of the freestyle stentless aortic bioprosthesis. Circulation 2012;126:S198–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider AW, Putter H, Hazekamp MG, et al. Twenty-year experience with stentless biological aortic valve and root replacement: Informing patients of risks and benefits. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2018;53:1272–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzola A, Mauro MD, Pellone F, et al. Freestyle aortic root bioprosthesis is a suitable alternative for aortic root replacement in elderly patients: a propensity score study. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:1185–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bach DS, Metras J, Doty JR, Yun KL, Dumensnil JG, Kon ND. Freedom from structural valve deterioration among patients aged < or = 60 years undergoing Freestyle stentless aortic valve replacement. J Heart Valve Dis 2007;16:649–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohammadi S, Baillot RG, Voisine P, Mathieu P, Dagenais F. Structural deterioration of the Freestyle aortic valve: mode of presentation and mechanisms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;132:401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider AW, Putter H, Hazekamp MG, et al. Twenty-year experience with stentless biological aortic valve and root replacement: Informing patients of risks and benefits. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 2018;53:1272–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammermeister K, Sethi GK, Henderson WG, Grover FL, Oprian C, Rahimtoola SH. Outcomes 15 years after valve replacement with a mechanical versus a bioprosthetic valve: Final report of the Veterans Affairs randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:1152–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for disease control and prevention; national center for health statistics. National death index. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ndi/index.htm. December 27, 2017.

- 11.Sherrah AG, Edelman JB, Thomas SR, et al. The freestyle aortic bioprosthesis: a systematic review. Heart Lung Circ 2014;23:1110–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ennker IC, Albert A, Dalladaku F, Rosendahl U, Ennker J, Florath I. Midterm outcome after aortic root replacement with stentless porcine bioprostheses. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 2011;40:429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amabile N, Bical OM, Azmoun A, Ramadan R, Nottin R, Deleuze PH. Long-term results of Freestyle stentless bioprosthesis in the aortic position: A single-center prospective cohort of 500 patients. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2011;148:1903–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ennker J, Meilwes M, Pons-Kuehnemann J, et al. Freestyle stentless bioprosthesis for aortic valve therapy: 17-year clinical results. Asian Cardiovascular and Thoracic Annals 2016;24:868–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherrah AG, Jeremy RW, Puranik R, et al. Outcomes following freestyle stentless aortic bioprosthesis implantation: The Australian experience up to 10 years. Heart Lung Circ 2016;24:82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation 2014;129:521–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Whole cohort age distribution at time of operation

Supplemental Figure 2: Cumulative incidence (CI) of reoperation after implantation of Freestyle aortic valve in patients younger or equal to 60 years and older than 60 years. The cumulative incidence of reoperation was significantly higher in patients <60 years (n=675) compared to patients older than 60 (n=1272) at 10 and 15 years. (7.8% vs. 1.1% and 27.7% vs 4.4%, respectively, p<0.0001).

Supplemental Figure 3: Long-term survival (Kaplan-Meier analysis) of patients with aortic valve replacement with Freestyle Bioprosthesis in patients ≤60 and >60 years.

Supplemental Table 1: Logistic model for operative mortality.