Abstract

Cell migration plays a critical role in vascular homeostasis. Under noxious stimuli, endothelial cells (ECs) migration always contributes to vascular repair, while enhanced migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) will lead to pathological vascular remodeling. Moreover, vascular activities are involved in communication between ECs and VSMCs, between ECs and immune cells, et al. Recently, Ma et al. (2015) discovered a novel migration-dependent organelle “migrasome,” which mediated release of cytoplasmic contents, and this process was defined as “migracytosis.” The formation of migrasome is precisely regulated by tetraspanins (TSPANs), cholesterol and integrins. Migrasomes can be taken up by neighboring cells, and migrasomes are distributed in many kinds of cells and tissues, such as in blood vessel, human serum, and in ischemic brain of human and mouse. In addition, the migrasome elements TSPANs are wildly expressed in cardiovascular system. Therefore, TSPANs, migrasomes and migracytosis might play essential roles in regulating vascular homeostasis. In this review, we will discuss the discoveries of migration-dependent migrasome and migracytosis, migrasome formation, the basic differences between migrasomes and exosomes, the distributions and functions of migrasome, the functions of migrasome elements TSPANs in vascular biology, and discuss the possible roles of migrasomes and migracytosis in vascular homeostasis.

Keywords: cell migration, migrasome, migracytosis, tetraspanins, vascular homeostasis

Blood Vessels and Vascular Homeostasis

The vasculature is one of the first functional organs to form during embryogenesis and matures into a closed cardiovascular system, adding up to about 90,000 km in total length in adults (Eelen et al., 2018). Structurally, blood vessels are primarily made up of three layers: tunica interna (intima), tunica media (media), and tunica externa (adventitia), which is a network of connective tissue, including collagen fibers, fibroblasts, vasa vasorum, nerve endings, progenitor/stem cells, myofibroblasts, pericytes, lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells et al. (Moos et al., 2005; Hu and Xu, 2011; Campbell et al., 2012; Wilting and Chao, 2015; Halper, 2018; Zhang Y. et al., 2018); while lymphatic capillaries are thin-walled vessels of approximately 30–80 μm in diameter, composed of a single layer of oak-leaf-shaped lymphatic ECs that differ in many ways from blood vascular ECs (Alitalo, 2011). Almost all tissues, except for cartilage, cornea and lens et al., in the body rely on blood vessels for a continuous supply of nutrients and oxygen, and on lymphatic vessels to collect excess protein-rich fluid that has extravasated from blood vessels and transport it back into blood circulation, and these vessels provide gateways for immune surveillance (Alitalo, 2011; Potente et al., 2011; Eelen et al., 2018). Additionally, blood vessels take part in controlling systemic pH and temperature homeostasis (Eelen et al., 2018).

During adult life, the maintenance of vascular homeostasis is the result of balancing vascular damage and injury with repair and regeneration, while also integrating environmental cues to optimize vascular function and blood vessel growth, thus ensuring adequate supply of oxygen and nutrients to tissues, and maintaining other functions mentioned above (Marsboom and Rehman, 2018). Vascular remodeling denotes morphological changes and reorganization of vessel wall structure, morphologically, all three layers of the arterial wall are concurrently affected by neointimal hyperplasia, medial thickening, and adventitial fibrosis attributable to the interaction of leukocyte recruitment, VSMCs accumulation, and endothelial recovery, in response to various noxious stimuli, such as hemodynamic stress, mechanical injury, inflammation, or hypoxia et al. (Schober, 2008; Zhang et al., 2016, 2017). All these lead to decrease in cross-sectional vessel diameters and increase in the thickness of the arterial wall. Therefore, vascular homeostasis maintenance is an active process, involved in the growth, migration and death of vascular cells, activation of immune cells in vasculature, as well as the generation and degradation of ECM, all these coordinate with environmental cues to maintain the function of blood vessels (Moos et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2014; Zhang and Dong, 2014; Zhang and Li, 2017).

Cell Migration in Development, Immune Defense and Vascular Homeostasis

Cell migration plays an essential role in a variety of physiological and pathological processes (Le Clainche and Carlier, 2008). During developmental processes, cell migration is fundamental to the establishment of the embryonic architecture like gastrulation (Keller, 2005), and migration is also required for neural crest cells colonization (Szabo and Mayor, 2018). Recently, Yu Li group indicated that migration-dependent migrasomes release developmental cues, including Cxcl12, into defined locations in embryos to modulate organ morphogenesis during zebrafish gastrulation (Jiang et al., 2019). The immune defensive function of most immune cells depends on their ability to migrate through complex microenvironments, either randomly to patrol for the presence of antigens or directionally to reach their next site of action (Moreau et al., 2018). In cardiovascular system, ECs migration occurs during vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, and also in damaged vessels to restore vessel integrity, VSMCs migrate to the intima and proliferate to contribute to neointimal lesions under pathophysiological conditions (Michaelis, 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). Therefore, cell migration is the key event during the regulation of vascular homeostasis.

The Discoveries of Migration-Dependent Migrasome and Migracytosis

Porter et al. (1945) and Taylor and Robbins (1963) have observed the long projections from the surface of cells, and long tubular structures as migrating cells retracted from the substratum, respectively. Oppenheimer and Humphreys (1971), Culp and Black (1972), and Terry and Culp (1974) isolated the specific macromolecules, which remain on substrates after treating with chelating agents. Morphological and biochemical analyses showed that these SAMs are finger-like extensions and contain relatively large amounts of cell surface components that participate in cell adhesion, such as fibronectin, proteoglycans, and gangliosides (Rosen and Culp, 1977; Culp et al., 1979; Rollins and Culp, 1979; Murray and Culp, 1981; Mugnai et al., 1984; Barletta et al., 1989). SAMs are analogous to the retraction fibers of migrating cells that are also enriched with TSPANs (Penas et al., 2000; Zhang and Huang, 2012; Yamada et al., 2013). Besides TSPANs, SAMs also contain large amounts of TSPANs associated proteins, but not focal adhesion proteins, and thus resemble the footprints (Yamada et al., 2013). Although these structures wildly present in different cell types, however, they have received little attention, their structure, characterization and function are less well-known.

Ma et al. (2015) observed and characterized an extracellular membrane-bound vesicular structure, which are PLSs relate to cells. They found that a cell will leave retraction fibers behind it, and vesicles grow on the tips or at the intersections of retraction fibers during the process of migration; eventually, the retraction fibers break up, and PLSs, as a package of vesicles and cytosolic contents enclosed within a single limiting membrane, are released into the medium or directly taken up by surrounding cells (da Rocha-Azevedo and Schmid, 2015; Ma et al., 2015). The formation of these PLSs is dependent on both migration and actin polymerization, thus, they named these PLSs “migrasomes,” which average lifespan is about 400 min, this migration-dependent release mechanism is named “migracytosis” (Ma et al., 2015).

The Molecular Mechanism of Migrasomes Formation

As migrasomes are membrane structures, therefore, membrane-localized proteins and the organization of membrane are essential for migrasomes formation. TSPANs family, which includes 33 members in human beings (Hemler, 2008; Rubinstein, 2011), are abundant in membranes of various types of endocytic organelles and in exosomes (Zoller, 2009; van Niel et al., 2018), and are also essential components of migrasomes (Table 1). TSPANs contain a number of shared structural features, including TM1, TM2, TM3 and TM4, a very short intracellular loop (typically four amino acids) between TM2 and TM3, a short ECL1 between TM1 and TM2, a large ECL2 between TM3 and TM4, short amino- and carboxy-terminal tails, and a large central pocket inside the intramembranous region bounded by the four transmembrane helices (Hemler, 2005; Zoller, 2009; Zimmerman et al., 2016; Umeda et al., 2020). The Glu219 in TSPAN28 is the critical residue for cholesterol molecule binding at the central cavity, TSPAN10 also possesses a polar residue in this position, while most other TSPANs have a polar residue one helical turn earlier, with other cholesterol-binding residues highly conserved throughout evolution, offering a potential mechanism for how TSPANs might detect cholesterol or other membrane lipids (Zimmerman et al., 2016). The TEMs, including TSPANs, a set of TSPANs-associated proteins and a high concentration of cholesterol, is a functional unit in cell plasma membranes (Yanez-Mo et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2019). The physiological and pathological functions of TSPANs family genes have been investigated and confirmed by the established TSPANs KO mice (Supplementary Table 1).

TABLE 1.

The basic characteristics of migrasomes and exosomes.

| Indexes | Exosomes | Migrasomes | References |

| Diameters | 30–200 nm | 0.5–3 μm | Ma et al., 2015; Pegtel and Gould, 2019 |

| Contents | Membrane organizers, enzymes, lipids, chaperon proteins, intracellular trafficking proteins, cell adhesion proteins, signal transduction proteins, cell-type-specific proteins, biogenesis factors, histones, nucleic acids (DNA: mtDNA, dsDNA, ssDNA, viral DNA; RNA: mRNA, miRNA, Pre-miRNA, Y-RNA, circRNA, mtRNA, tRNA, tsRNA, snRNA, snoRNA, piRNA), amino acids, glycoconjugates, and metabolites et al. | Vesicles, membrane proteins, contractile proteins, cytoskeleton proteins, enzymes, chaperon proteins, vesicle traffic proteins, receptors, cell adhesion proteins, extracellular proteins, DNA or RNA binding proteins, complement system proteins, signal transduction proteins, lipids, et al. | Ma et al., 2015; Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018; van Niel et al., 2018; Pegtel and Gould, 2019; Kalluri and LeBleu, 2020 |

| TSPANs profiles | TSPAN6, 8, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, et al. | TSPAN4, TSPAN7, et al. | Ma et al., 2015; van Niel et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2019; Pegtel and Gould, 2019 |

| Classical membrane markers | TSPAN28, TSPAN29, TSPAN30, TSG101, et al. | TSPAN4, TSPAN7, Integrin α5 and β1, et al. | Ibrahim and Marban, 2016; Wu et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2019 |

| Specific protein markers | SUMF2, LAMP1 | NDST1, PIGK, CPQ, EOGT | Ma et al., 2015; Ibrahim and Marban, 2016; Zhao et al., 2019 |

| Release | By fusion of MVBs with plasma membrane | By breaking the retraction fibers | Ma et al., 2015 |

mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA; miRNA, microRNA; circRNA, circular RNA; mtRNA, mitochondrial RNA; tRNA, transfer RNA; tsRNAs, tRNA-derived small RNAs; snRNA, small nuclear RNA; snoRNA, small nucleolar RNA; piRNA, PIWI-interacting RNA; TSG101, tumor susceptibility gene 101; SUMF2, sulfatase modifying factor 2; LAMP1, lysosomal associated membrane protein 1; NDST1, bifunctionalheparan sulfate N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase 1, PIGK, phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis, class K, CPQ, carboxypeptidase Q; EOGT, EGF domain-specific O-linked N-acetylglucosaminetransferase; MVB, multivesicular bodies.

During the discovery of migrasomes, Yu Li group identified that TSPAN4 is abundant in migrasomes membrane, and acts as the clearest migrasomes marker (Ma et al., 2015). Overexpression of TSPAN1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 13, 18, 25, 26, 27, and 28 enhance the formation of migrasomes, and TSPAN1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 18, 27, and 28 have strong effects (Huang et al., 2019). KO of TSPAN4 impairs migrasomes formation in MGC-803 cells and NRK, while deficiency of TSPAN4 in L929 cells did not impair migrasomes formation, presumably due to the presence of other migrasomes-forming TSPANs (Huang et al., 2019). TSPAN4, TSPAN7, cholesterol and integrins are necessary for migrasomes formation (Wu et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2019). TSPAN4 in migrasomes is about four times higher than in retraction fibers, cholesterol is enriched about 40-fold in migrasomes relative to retraction fibers, and integrins are highly enriched on migrasomes and are only present at very low levels on retraction fibers (Wu et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019). The activated integrin α5 is mainly enriched on the bottom side of migrasomes while TSPAN4 is on the upper side (Wu et al., 2017). Mechanistically, when a cell migrates, integrins enable cell migration and the correct pairing of integrin with its specific ECM partner protein provides the adhesion for retraction fiber tethering, and retraction fibers are formed at the back of the migrating cells (Wu et al., 2017). The mechanical stress exerted along the retraction fibers triggers clustering of TSPANs, such as TSPAN4, TSPAN7, and cholesterol molecules, leading to the formation of “TEMAs,” which enriched causes stiffening of the plasma membrane, thus, facilitating a new migrasome formation (Huang et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2019; Tavano and Heisenberg, 2019).

The Basic Differences Between Migrasomes and Exosomes

Both migrasomes and exosomes are the extracellular membrane-bound vesicular structures, however, the comparison of migrasomes and exosomes proteomics indicates that the two structures share only 27% (158) proteins, and there is still much difference among size, contents, TSPANs expression profiles, classical membrane markers, specific protein markers, and the process of release (da Rocha-Azevedo and Schmid, 2015; Ma et al., 2015; Ibrahim and Marban, 2016; Wu et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018; Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018; van Niel et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2019; Jeppesen et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2019; Pegtel and Gould, 2019; Zhao et al., 2019; Kalluri and LeBleu, 2020; Table 1).

Based on these above, TSPAN4/7 and integrin α1, α3, α5, β1 et al., which are expressed in the membrane of migrasomes, can act as essential structure markers for migrasomes (Ma et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2017; Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2019). NDST1, PIGK, CPQ and EOGT, which are enriched in migrasomes, but are absent or barely detectable in exosomes, are specific protein markers for migrasomes (Zhao et al., 2019). The transmission electron microscopy is used to detected ultrastructure of migrasomes in situ within cultured cells (Chen et al., 2018). A recent study by Yu Li group indicated that WGA is a probe for convenient, rapid detection of migrasomes in both fixed and living cells (Chen et al., 2019). The detail methods for visualizing migrasomes have also been described in two articles of “Detection of Migrasomes” and “WGA is a probe for migrasomes” by Yu Li group (Chen et al., 2018, 2019).

The Distributions and Functions of Migrasomes

Studies in the past 5 years indicated that migrasomes are distributed in many cell types in vitro, including NRK, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF and NIH3T3), mouse melanoma cell (B16), mouse embryonic stem cells, mouse hippocampal neurons and mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages, and murine microglia, human keratinocyte (HaCaT), human breast cancer cell (MDA-MB-231), human colon cancer cell (HCT116), human adenocarcinoma cell (SW480), human gastric carcinoma cell (MGC803), human ovarian adenocarcinoma cell (SKOV-3) (Ma et al., 2015; Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018). Moreover, migrasomes are also distributed in various organs, such as human stroke specimens, mouse eye, rat lung, rat/mouse intestine (Ma et al., 2015; Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018; Figure 1). They tend to be present inside cavity such as pulmonary alveoli or blood vessel, for example, in intestine, migrasomes are inside blood capillaries or lymph capillaries, in the lamina propria of ileum crypts, or in connective tissue (Ma et al., 2015). The mice model study indicate that migrasomes can be detected in the brain of the ischemic hemispheres of mice feeding standard diet, and high-salt diet induces massive migrasomes formation in microglia/macrophages and leads to reduce numbers of anti-inflammatory F4/80+-microglia/macrophages and astrocytes after cerebral ischemia (Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018). F4/80+-migrasomes are co-localized with NeuN, which is expressed in nuclei and cytoplasm of neurons, and there is a significant correlation between the extent of migrasome formation and the number of shrunk neurons (Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018). These findings suggest that migrasome, which incorporates and dispatches the cytosol of surrounding neurons, might act as a novel, sodium chloride-driven mechanism in acute ischemic stroke pathophysiology (Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018). However, the precise regulatory mechanisms between migrasome formation and neuronal loss still need further investigation. Recently, the physiological roles of migrasomes in living animals has been investigated by using the zebrafish embryo as a model system, the results indicated that migrasomes were enriched on a cavity underneath the embryonic shield where they served as chemoattractants to ensure the correct positioning of dorsal forerunner cells vegetally next to the embryonic shield, thus coordinating organ morphogenesis during zebrafish gastrulation (Jiang et al., 2019). Surprisingly, Yu Li group found that migrasomes are present in human serum, but their origin and function are not clear (Zhao et al., 2019). Therefore, to discuss and investigate its roles in vascular biology is an interesting topic.

FIGURE 1.

The organization and distributions of migrasomes. Migrasome, which is an extracellular membrane-bound vesicular structure and includes cytosolic proteins and small vesicles in the cavity, is organized by TSPANs, cholesterol, and integrins. The matching of specific integrin-ECM pairs determine when and where migrasome can be generated in vivo. They are distributed in human blood and stroke specimens; in mouse brain and eye, rat lung, rat/mouse intestine; in zebrafish embryo. They are also found in numerous cancer cells, such as MDA-MB-231, SKOV-3, HCT116, SW480, MGC803, B16; in normal rat or mouse cells, including NRK, NIH3T3, mouse embryonic stem cells, hippocampal neurons and bone marrow-derived macrophages, and microglia; and in HaCaT in vitro.

The Current Understanding of Tetraspanins Family in Vascular Homeostasis

Migracytosis, a cell migration-dependent mechanism for releasing intracellular contents into external environment, and migrasomes, the vesicular structures that mediate migracytosis, are involved in cell–cell communications, as that the releasing contents can be taken up by surrounding cells (Ma et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018). Based on their distribution in vivo and in vitro, it seems that they may play essential roles in maintaining vascular homeostasis. However, there are few literatures discussed the functions of migrasomes and migracytosis in blood vessel. Therefore, to understand the vascular function of TSPANs, which are the key elements of migrasomes, may help us to investigate and understand the possible roles of migrasomes and migracytosis in vascular homeostasis in the near future.

Bailey et al. (2011) have investigated TSPANs expression at the mRNA level in human ECs by analyzing largescale transcriptomic data from publicly available SAGE experiments. They found that HUVECs expressed 23 TSPANs and human liver endothelium expressed 17 TSPANs. The RNA-seq analyses and RNA-arrays for TSPANs family genes expressed in HCASMCs, MASMCs and mouse carotid arteries indicate that all TSPANs except for TSPAN16 and TSPAN19 are detectable in these cells and tissue (Zhao et al., 2017). More than one half of TSPANs family genes are significantly reduced by TGF-β1, while only TSPAN2, 12, 13, and 22 are up-regulated, and TSPAN2 shows the most dramatic change by TGF-β1 (Zhao et al., 2017). Myocardin, which is another master regulator of VSMCs differentiation, increases 8 TSPANs genes expression, including TSPAN2, 7, 10, 11, 12, 15, 21, 33, and TSPAN2 showed the greatest up-regulation (Zhao et al., 2017). The expression profiles of TSPANs family genes in ECs and VSMCs indicate that they may play critical roles in vascular biology, such as migration (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

The effects of TSPANs in vascular cells migration.

| TSPANs | Expression | Migration | References |

| TSPAN2 | HUVECs, HCASMCs, MASMCs | HCASMCs↓ | Bailey et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2017 |

| TSPAN27 | HUVECs, HDMECs, HRCECs, MLUECs, MLVECs, HCASMCs, MASMCs | HUVECs↓, MLU/VECs↓ | Nagao and Oka, 2011; Wei et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2017 |

| TSPAN8 | HUVECs, RAECs, HCASMCs, MASMCs | RAECs↑ | Nazarenko et al., 2010; Bailey et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2017 |

| TSPAN12 | HUVECs, HLVECs, MRVECs, HCASMCs, MASMCs | HUVECs↑ | Bailey et al., 2011; Bucher et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2017; Zhang C. et al., 2018 |

| TSPAN24 | HUVECs, HLVECs, MLUECs, iBRECs, HDLECs, HMEC-1, HCASMCs, MASMCs | HUVECs↑, MLUECs↑ | Yanez-Mo et al., 1998; Deissler et al., 2007; Takeda et al., 2007; Bailey et al., 2011; Iwasaki et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2017 |

| TSPAN28/30 | HUVECs, HLVECs, HSVECs, HMAECs, iBRECs, HDLECs, HCASMCs, MASMCs | HUVECs↑ | Yanez-Mo et al., 1998; Klein-Soyer et al., 2000; Deissler et al., 2007; Bailey et al., 2011; Iwasaki et al., 2013; Tugues et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2017 |

| TSPAN29 | HUVECs, HLVECs, HSVECs, HMAECs, iBRECs, HDLECs, HCASMCs, MCASMCs, MASMCs | HUVECs↑, HSVECs↑, HMAECs↑, HCASMCs↑, HDLECs↑, iBRECs↑ | Yanez-Mo et al., 1998; Klein-Soyer et al., 2000; Deissler et al., 2007; Kotha et al., 2009; Bailey et al., 2011; Iwasaki et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2017 |

| TSPAN3/4/5/6/7/9/13/14/18/25/31 | HUVECs, HLVECs, HCASMCs, MASMCs | ? | Bailey et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2017 |

| TSPAN11/15/23 | HUVECs, HCASMCs, MASMCs | ? | Bailey et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2017 |

| TSPAN17 | HLVECs, HCASMCs, MASMCs | ? | Bailey et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2017 |

| TSPAN1/10/20/21/22/26/32/33 | HCASMCs, MASMCs | ? | Zhao et al., 2017 |

| TSPAN19 | HUVECs | ? | Bailey et al., 2011 |

HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; HCASMCs, human coronary artery smooth muscle cells; MASMCs, mouse aortic smooth muscle cells; HDMECs, human dermal microvascular endothelial cells; HRCECs, human retinal capillary endothelial cells; MLUECs, mouse lung endothelial cells; MLVECs, mouse liver endothelial cells; RAECs, rat aortic endothelial cells; HLVECs, human liver endothelial cells; MRVECs, mouse retinal vascular endothelial cells; iBRECs, microvascular endothelial cells of the bovine retina; HDLECs, human dermal lymphatic endothelial cells; HMEC-1, human microvascular endothelial cell line-1; HSVECs, human saphenous vein endothelial cells; HMAECs, human mammary artery endothelial cells; MCASMCs, mouse carotid artery smooth muscle cells.

TSPAN2 is extensively expressed in medial layer VSMCs of aortas, bladder, brain, lung, skeletal muscle, stomach, heart, spleen, kidney and liver, however, the levels of TSPAN2 is decreased in mouse carotid arteries after ligation injury and in failed human arteriovenous fistula samples after occlusion by dedifferentiated neointimal VSMCs (Zhao et al., 2017). TSPAN2 acts as a suppressor of VSMCs proliferation and migration, and plays important role in the pathogenesis of occlusive vascular diseases (Zhao et al., 2017). Mechanistically, transcription of TSPAN2 in VSMCs is regulated by 2 parallel pathways, TGF-β1/SMAD and myocardin/serum response factor, via distinct binding sites in the vicinity of the TSPAN2 promoter (Zhao et al., 2017). Additionally, the single-nucleotide polymorphism located in the regulatory region (G allele at rs12122341) of TSPAN2 is strongly associated with atherosclerosis in large arteries (Ninds Stroke Genetics Network [SIGN] and International Stroke Genetics Consortium [ISGC], 2016). However, the function of TSPAN2 in ECs is not clear.

TSPANC8 subgroup, which have the eight cysteine residues in their large extracellular loops, includes TSPAN5, 10, 14, 15, 17, and 33 (Matthews et al., 2018). TSPAN5 is highly expressed in neocortex, hippocampus, amygdala and in Purkinje cells in the cerebellum of mouse (Garcia-Frigola et al., 2000), and its expression is prominent in both atrial and trabeculated ventricular chambers of the heart on embryonic day 10, indicated that it might be involved in heart development (Garcia-Frigola et al., 2001). TSPAN14 is the major TSPANs of TSPANC8 subgroup in HUVECs and is essential for normal ADAM10 surface expression and activity, while TSPAN33 is the major TSPANs of TSPANC8 subgroup in the erythrocyte lineage and is essential for normal ADAM10 expression (Haining et al., 2012). The vascular functions of TSPANC8 subgroup members still need further investigation.

TSPAN18 is highly expressed in ECs, TSPAN18-knockdown ECs have impaired Ca2+ mobilization, and impaired histamine- and thrombin-induced von Willebrand Factor release (Noy et al., 2019). Mechanistically, TSPAN18 interacts with Orai1, which is a major entry route for extracellular Ca2+ in non-excitable cells (Noy et al., 2019). Thus, TSPAN18 is essential for Ca2+ homeostasis and inflammatory responses in ECs.

Among TSPANs, TSPAN8, TSPAN24, TSPAN12, and TSPAN29 are the main TSPANs family members that facilitate angiogenesis (Hemler, 2014; Bucher et al., 2017; Heo and Lee, 2020). Gesierich et al. (2006) firstly reported that TSPAN8 is the strongest angiogenesis inducer, as that overexpression of TSPAN8 in tumor cells markedly increases angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro, and co-culture of TSPAN8 knockdown tumor cells or the exosomes-depleted supernatant with HUVECs markedly inhibit HUVECs tube formation in vitro (Gesierich et al., 2006; Akiel et al., 2016). Mechanistically, the tumor cells released exosomes containing TSPAN8 are taken up by target cells via ligands for TSPAN8-associated molecules, and induce angiogenic gene transcription and modulate the RNA profile in ECs or adjacent fibroblasts, and exosomes expressing TSPAN8-CD49d complex preferentially bind ECs, thus initiating an angiogenic loop by inducing TSPAN8 itself expression on sprouting ECs (Gesierich et al., 2006; Nazarenko et al., 2010; Mu et al., 2020). The contribution of TSPAN8 and TSPAN24 on angiogenesis has also been confirmed by TSPAN8-KO mice, TSPAN24-KO mice and TSPAN8/24 double-KO mice (Takeda et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2018a, b) (Supplementary Table 1). Mechanistically, promotion of angiogenesis by tumor-derived exosomes and rescue of impaired angiogenesis in KO mice by wild type-serum exosomes depend on the association of TSPAN8 and TSPAN24 with GPCR and RTK in ECs and tumor cells (Zhao et al., 2018b; Mu et al., 2020). Most importantly, the TSPAN24-integrin complex as a functional unit, and the YRSL motif of TSPAN24 plays key role in TSPAN24-mediated angiogenesis (Sincock et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2002; Zuo et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011; Peng et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2016). Based on its effects on angiogenesis, TSPAN24 gene delivery promotes angiogenesis and improves skin temperature in rat hindlimb ischemia model (Liu et al., 2011), enhances myocardial angiogenesis and improves left ventricular function in rat acute myocardial infarction model (Wang et al., 2006; Fu et al., 2015), and the beneficial effect of TSPAN24 on myocardial angiogenesis has also been confirmed in a pig myocardial infarction model (Zuo et al., 2009). In contrast, the oxygen-induced retinal neovascularization and angiogenesis in three tumors models are not decreased in TSPAN24-null mice (Takeda et al., 2007; Deng et al., 2012; Copeland et al., 2013a; Li et al., 2013), indicated that the contributions of TSPAN24 in angiogenesis might be models/diseases dependent. TSPAN24 maintains vascular stability by balancing the forces of cell adhesion and cytoskeletal tension as that TSPAN24 deficiency increases actin cytoskeletal traction by elevating RhoA signaling and diminishes actin cortical meshwork by decreasing Rac1 activity (Zhang et al., 2011). Similar to its influence in angiogenesis, the effect of TSPAN24 on vascular permeability might also be model-dependent as that TSPAN24 deletion did not affect VEGF-induced vascular permeability (Takeda et al., 2011). Moreover, TSPAN24 acts as a molecular linker between MT1-MMP and α3β1 integrin in ECs: MT1-MMP, through its hemopexin domain, associates tightly with TSPAN24, thus forming α3β1 integrin/TSPAN24/MT1-MMP ternary complexes, which is essential for a normal pattern of MT1-MMP-dependent collagenolysis (Yanez-Mo et al., 2008). Thus, TSPAN24 is a key regulator of MT1-MMP in mediating endothelial homeostasis.

TSPAN12, which is expressed in retinal vasculature, has been extensively investigated in ophthalmology (Junge et al., 2009; Nikopoulos et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2011; Seo et al., 2016; Bucher et al., 2017; Lai et al., 2017; Zhang C. et al., 2018). Physiologically, TSPAN12 acts as a key regulator for retinal vascular development by activating NDP- but not Wnt-induced FZD4/β-catenin signaling, early loss of TSPAN12 in ECs causes lack of intraretinal capillaries and increased the expression of ECs-specific adhesion molecule cadherin5, consistent with premature vascular quiescence, late loss of TSPAN12 strongly impairs BRB maintenance without affecting vascular morphogenesis, pericyte coverage, or perfusion, thus, the endothelial TSPAN12 contributes to vascular morphogenesis and BRB formation in developing mice and BRB maintenance in adult mice (Junge et al., 2009; Zhang C. et al., 2018). Mechanistically, TSPAN12 is an essential component of the NDP receptor complex and interacts with FZD4 and NDP via its extracellular loops, consistent with an action as co-receptor that enhances FZD4 ligand selectivity for NDP, which signaling is required for normal retinal angiogenesis and BRB function (Lai et al., 2017). Based on its role in retinal angiogenesis during development, mutations in TSPAN12 or large deletions of TSPAN12 cause familial exudative vitreoretinopathy in human (Nikopoulos et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2011; Seo et al., 2016), in contrast, the anti-TSPAN12 antibody, which inhibits ECs migration and tube formation, ameliorates vasoproliferative retinopathy via suppressing β-Catenin signaling in rodent models of retinal neovascular disease (Bucher et al., 2017). The function of TSPAN12 in retinal vasculature, especially in retinal ECs, is relatively clear; however, its functions in large arteries are not fully understood.

TSPAN29 promotes angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis via forming functional complexes between VEGFR-3 and integrin α5 and α9, therefore, tumor-induced and inflammation-induced lymphangiogenesis, and tumor-induced angiogenesis are decreased in TSPAN29-KO mice (Iwasaki et al., 2013) (Supplementary Table 1). Intravitreous injections of siRNA-TSPAN29 or anti-TSPAN29 antibodies are therapeutically effective for laser-induced retinal and choroidal neovascularization in mice, and injecting siRNA-TSPAN29 markedly suppresses HGF- or VEGF-induced subconjunctival angiogenesis in vivo (Kamisasanuki et al., 2011). Using anti-TSPAN29 monoclonal antibody, three independent experiments revealed that TSPAN29 participates in ECs migration during wound repair in vitro, and TSPAN29 is required for platelet-induced HUVECs proliferation (Klein-Soyer et al., 2000; Ko et al., 2006; Deissler et al., 2007). Mechanistically, TSPAN29, TSPAN28, and TSPAN24 localize at cell–cell junctions of ECs and are associated with each other and those of TSPAN29 and TSPAN24 with α3β1 integrin, which are essential for ECs motility, as that monoclonal antibodies directed to both TSPAN24 and TSPAN28 as well as monoclonal antibody specific for α3 integrin, are able to inhibit ECs migration in the process of wound healing (Yanez-Mo et al., 1998). However, another study indicated that ablation of TSPAN29 does not affect proliferation, apoptosis or angiogenesis in primary prostate tumors (Copeland et al., 2013b). Similar to TSPAN24, TSPAN29-dependent angiogenesis might also be model-dependent and perhaps other TSPANs compensates for the absence of TSPAN29 (Hemler, 2014). TSPAN29 also associates with integrins in VSMCs (Scherberich et al., 1998), the neutralization antibody for TSPAN29 reduces the proliferation and migration of VSMCs, and results in a 31% reduction in neointima formation in a mouse carotid ligation injury model, in contrast, overexpression of TSPAN29 leads to 43% increase in neointima (Kotha et al., 2009). To further understand how TSPAN29 regulate adverse VSMCs phenotypes, Herr et al. (2014) used TSPAN29 lentiviral shRNA to knockdown TSPAN29 expression in VSMCs, and found that TSPAN29 deficiency is sufficient to profoundly disrupt cellular actin arrangement and endogenous cell contraction by interfering with RhoA signaling.

In contrast to TSPAN8/12/24/29, ECs TSPAN27 restrains pathologic angiogenesis (Wei et al., 2014). Deficiency of TSPAN27 significantly enhances the migration and invasion of ECs, and markedly increases vascular morphogenesis to various stimuli, however, slightly promotes ECs proliferation and survival (Wei et al., 2014). Mechanistically, TSPAN27 modulates CAMs trafficking by preventing lipid raft aggregation and dissociating CAMs from lipid rafts, and TSPAN27-ganglioside-CD44 signaling restrains angiogenesis by inhibiting ECs adhesiveness and motility (Wei et al., 2014). Therefore, the balance of these TSPANs in regulating angiogenesis is critical for vascular homeostasis.

TSPAN30, which is localized in late endosomes/lysosomes and on the plasma membrane in ECs, contributes to several cell functions relevant to initiation and progression of angiogenesis, such as adhesion and migration of vascular ECs, mechanistically, TSPAN30 associates with both integrin β1 and VEGFR-2 to form functional complexes to modulate VEGFR2 signaling and internalization (Tugues et al., 2013). TSPAN30 also colocalizes with von Willebrand factor and P-selectin to reside in the membrane of Weibel-Palade bodies of ECs (Vischer and Wagner, 1993). Similarly, TSPAN30 coclusters with P-selectin on the plasma membrane of activated ECs, it is thus an essential cofactor to leukocyte recruitment by endothelial P-selectin (Doyle et al., 2011). Other TSPANs are also known to organize leukocyte adhesion molecules into microdomains (Ley, 2011). For example, TSPAN24 and TSPAN29 are components of the endothelial docking structure for adherent leukocytes by their association with ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in ECs (Barreiro et al., 2005). However, their requirement for leukocyte adhesion is not as stringent as that of TSPAN30 (Ley, 2011). TSPAN28, a putative receptor for hepatitis C virus, is up-regulated in ECs of early atherosclerotic lesions, and it has the potential to substantially enhance monocyte adhesion via relocalizing and increasing membrane clustering of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (Pileri et al., 1998; Rohlena et al., 2009). Moreover, TSPAN28 interaction with Rac1 through its cytoplasmic C-terminal region limits the GTPase activation within the plasma membrane during cell adhesion and migration (Tejera et al., 2013). As described above, overexpression of TSPAN28 can enhance migrasomes formation in NRK (Huang et al., 2019), however, whether TSPAN28 can influence migrasomes formation in vascular cells has not been investigated.

Perspective

TSPANs family, which is known to be important in vesicle formation and targeting of vesicles to recipient cell, is involved in a multitude of biological processes, such as development, fertilization, platelet aggregation, parasite and viral infection, immune response induction, metastasis suppression and tumor progression, ophthalmology, synaptic contacts at neuromuscular junctions, maintenance of skin integrity (Hemler, 2003; Levy and Shoham, 2005; Zoller, 2009; Bailey et al., 2011; Rana and Zoller, 2011; Charrin et al., 2014; Colombo et al., 2014; van Niel et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2019). Moreover, TSPANs are widely expressed in hematopoietic and vascular cells, such as ECs and VSMCs, and are also participated in both physiological and pathological processes related to thrombosis, hemostasis, angiogenesis and vascular injuries (including vascular cells migration), thus emerging novel roles in regulating vascular biology (Zhang et al., 2009; Table 2).

As we have discussed above, migrasomes are organized by TSPANs, cholesterol, integrins and other unidentified molecules, and migracytosis releases cellular contents at a specific location, these cellular contents can be taken up by other cells which travel to that site, indicates that biochemical and spatial information from outgoing cells can be acquired by incoming cells (Ma et al., 2015; Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2019). Considered that migrasomes are distributed in blood vessel, human serum, and in infarcted brain parenchyma of human stroke patients, the contraction and relaxation, vascular repair, and immune responses occurred in blood vessels require vascular cells or immune cells migration, and the localized communication between ECs and VSMCs, and between ECs and immune cells, et al. (Ma et al., 2015; Eelen et al., 2018; Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2019), thus, there is not surprising that migration-dependent migrasomes and migracytosis might play important roles in these processes and act as novel players in mediating vascular homeostasis.

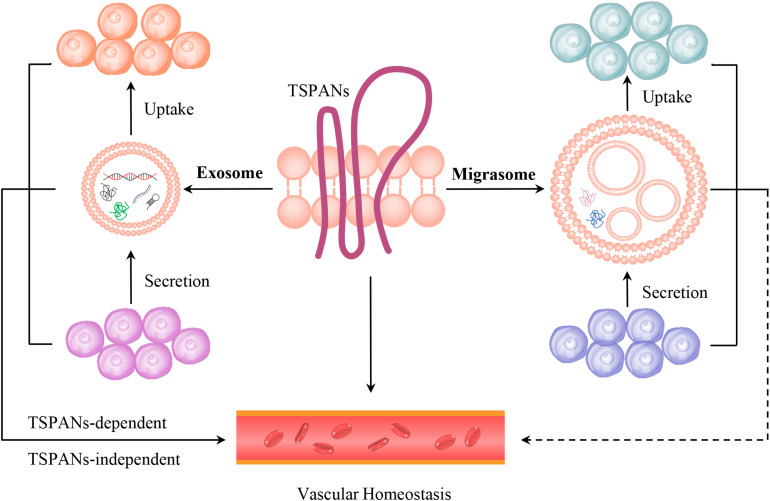

It should be noticed that TSPANs are expressed in the membranes of both exosomes and migrasomes (da Rocha-Azevedo and Schmid, 2015; Ma et al., 2015; Ibrahim and Marban, 2016; Wu et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018, 2019; Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2019; Pegtel and Gould, 2019; Tavano and Heisenberg, 2019; Zhao et al., 2019). The exosomes play essential roles in ECs dysfunction and regeneration, VSMCs migration, ischemic heart disease, cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis by transferring their bioactive cargos, such as microRNAs and proteins (Ibrahim and Marban, 2016; Barile et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2018; Tong et al., 2018; Baruah and Wary, 2019; Ranjan et al., 2019). Moreover, cancer cells released exosomes containing TSPAN8 are critical for angiogenesis, as that they can be taken up and initiate angiogenic genes transcription and modulate the RNA profile in ECs or adjacent fibroblasts (Gesierich et al., 2006; Nazarenko et al., 2010; Mu et al., 2020). However, it is not known whether the tumor cells-expressed migraomses can be taken up by ECs in vivo, and influence tumor-induced angiogenesis and subsequently tumor growth, and what will happen if these tumor-derived migrasomes reaches organs distant from the tumor? These should be carefully investigated in the near future. Therefore, exosomes- or migrasomes-dependent or independent effects of TSPANs, the TSPANs-dependent or independent effects of exosomes or migrasomes in modulating vascular biology, and the relationships between exosomes and migrasomes in regulating vascular homeostasis should be distinguished and investigated (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The models of TSPANs, exosomes and migrasomes in vascular homeostasis. TSPANs are the key organizators of both exosome and migrasome. TSPANs can regulate vascualr homeostasis directly. Exosomes, which contain selected proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, amino acids, glycoconjugates and metabolites et al., are secreted by one cell and taken up by another cell, thus transferring signals through cell–cell communication and influencing vascular homeostasis in TSPANs-dependent or independent manners. Migrasomes, which are distributed in blood circulation and blood vessel, contain bioactive cargos, and are also secreted by one cell and taken up by the surrounding cells. Therefore, migrasomes might influence vascular homeostasis via cell–cell communication.

The formation of migrasome depends on the matching of specific integrin-ECM pairs, there are 18 α and 8 β integrins in mammals, and each ECM protein has a specific spatial and temporal distribution pattern in a given organism, which will determine when and where migrasome can be generated in vivo (Wu et al., 2017). As we have mentioned above, migrasomes display temporal and spatial distributions during the development of zebrafish embryos (Jiang et al., 2019). The percentage of containing in migrasomes is organ-, tissue- or cell type-dependent. Migrasomes in ischemic brain are mainly composed of contractile proteins actin and myosin, cytoskeleton and annexin proteins, while enzymes are the most (31%) contents and much of them are involved in metabolic processes in migrasomes from NRK (Ma et al., 2015; Schmidt-Pogoda et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2019). The zebrafish embryonic migrasomes are enriched for a host of chemokines, morphogens, cytokines and growth factors, including Tgfβ2, Il1β, PdgfD, Cxcl12b, Wnt11, Mydgf, DllD, Cxcl12a, Bmp1, Wnt8a, Chd, Bmp7a, Cxcl18a.1, Wnt5b, Lefty1 and Bmp2, and migrasomes regulate organ morphogenesis by delivering Cxcl12a/b for Cxcl12a (ligand)-Cxcr4b (receptor) signaling (Jiang et al., 2019). However, the compositions of vascular migrasomes, the origins and targets of migrasomes in human serum, and the pathways of migrasomes entering the circulatory system are not clear (Zhao et al., 2019). Are migrasomes in human serum related to certain cardiovascular diseases, and can they be used as a diagnostic marker (Zhao et al., 2019)? Therefore, these seem that the possible roles of migrasomes and migracytosis in cardiovascular system might be mainly dependent on their origins, compositions, levels, temporal distribution patterns, and locations.

Author Contributions

YZ and HY contributed to concept and idea. YZ, JZ, and YX prepared the figures and tables. YZ, JW, YD, SZ, and JX wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to all of the authors whose invaluable work we could not discuss or cite in this review due to space constraints. We should thank Bi Mingmin and Fang Chun for the technical preparation of figures.

Abbreviations

- BRB

blood–retina barrier

- CAMs

cell adhesion molecules

- circRNA

circular RNA

- CPQ

carboxypeptidase Q

- dsDNA

double-stranded DNA

- ECs

endothelial cells

- ECL1

extracellular loop 1

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EOGT

EGF domain-specific O-linked N-acetylglucosaminetransferase

- FZD4

Frizzled-4

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- HCASMCs

human coronary artery smooth muscle cells

- HDLECs

human dermal lymphatic endothelial cells

- HDMECs

human dermal microvascular endothelial cells

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- HLVECs

human liver endothelial cells

- HMAECs

human mammary artery endothelial cells

- HMEC-1

human microvascular endothelial cell line-1

- HRCECs

human retinal capillary endothelial cells

- HSP

heat shock protein

- HSVECs

human saphenous vein endothelial cells

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- iBRECs

microvascular endothelial cells of the bovine retina

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- KO

knockout

- LAMP1

lysosomal associated membrane protein 1

- MASMCs

mouse aortic smooth muscle cells

- MCASMCs

mouse carotid artery smooth muscle cells

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblast

- miRNA

microRNA

- MLUECs

mouse lung endothelial cells

- MLVECs

mouse liver endothelial cells

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MRVECs

mouse retinal vascular endothelial cells

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- mtRNA

mitochondrial RNA

- MT1-MMP

membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase

- MVB

multivesicular bodies

- NDP, norrie disease protein

also referred to as norrin

- NDST1

bifunctionalheparan sulfate N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase 1

- NeuN

Neuronal Nuclei

- NRK

normal rat kidney cell

- PDGF-BB

platelet derived growth factor-BB

- PIGK, phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis

class K

- piRNA

PIWI-interacting RNA

- PLSs

pomegranate-like structures

- RAECs

rat aortic endothelial cells

- RTK

Receptor tyrosine kinase

- SAGE

serial analysis of gene expression

- SAMs

substrate-attached materials

- siRNA-TSPAN29

TSPAN29-specific small interfering RNA

- snoRNA

small nucleolar RNA

- snRNA

small nuclear RNA

- ssDNA

single-stranded DNA

- SUMF2

sulfatase modifying factor 2

- TEMs

TSPAN-enriched microdomains

- TEMAs

tetraspanin- and cholesterol-enriched macrodomains

- TM1

transmembrane region 1

- tRNA

transfer RNA

- TSG101

tumor susceptibility gene 101

- TSPANs

tetraspanins

- tsRNAs

tRNA-derived small RNAs

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR-3

VEGF receptor 3

- VSMCs

vascular smooth muscle cells

- WGA

wheat-germ agglutinin.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by Project funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2019M653238, the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, grant numbers 2018A030313657 and 2018A030313733, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 81900376 and 81901447, and Guangdong famous Traditional Chinese Medicine inheritance studio construction project, grant number 20180137.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2020.00438/full#supplementary-material

References

- Akiel M. A., Santhekadur P. K., Mendoza R. G., Siddiq A., Fisher P. B., Sarkar D. (2016). Tetraspanin 8 mediates AEG-1-induced invasion and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. FEBS Lett. 590 2700–2708. 10.1002/1873-3468.12268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alitalo K. (2011). The lymphatic vasculature in disease. Nat. Med. 17 1371–1380. 10.1038/nm.2545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey R. L., Herbert J. M., Khan K., Heath V. L., Bicknell R., Tomlinson M. G. (2011). The emerging role of tetraspanin microdomains on endothelial cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39 1667–1673. 10.1042/BST20110745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barile L., Moccetti T., Marban E., Vassalli G. (2017). Roles of exosomes in cardioprotection. Eur. Heart. J. 38 1372–1379. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barletta E., Mugnai G., Ruggieri S. (1989). Morphological characteristics and ganglioside composition of substratum adhesion sites in a hepatoma cell line (CMH5123 cells) during different phases of growth. Exp. Cell Res. 182 394–402. 10.1016/0014-4827(89)90244-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro O., Yanez-Mo M., Sala-Valdes M., Gutierrez-Lopez M. D., Ovalle S., Higginbottom A., et al. (2005). Endothelial tetraspanin microdomains regulate leukocyte firm adhesion during extravasation. Blood 105 2852–2861. 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruah J., Wary K. K. (2019). Exosomes in the regulation of vascular endothelial cell regeneration. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 7:353. 10.3389/fcell.2019.00353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher F., Zhang D., Aguilar E., Sakimoto S., Diaz-Aguilar S., Rosenfeld M., et al. (2017). Antibody-mediated inhibition of Tspan12 ameliorates vasoproliferative retinopathy through suppression of beta-catenin signaling. Circulation 136 180–195. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K. A., Lipinski M. J., Doran A. C., Skaflen M. D., Fuster V., McNamara C. A. (2012). Lymphocytes and the adventitial immune response in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 110 889–900. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.263186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang X., Yao J., He Q., Liu M., Duan T., Wang K. (2018). Exosomes from women with preeclampsia induced vascular dysfunction by delivering sFlt (soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase)-1 and sEng (soluble endoglin) to endothelial cells. Hypertension 72 1381–1390. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrin S., Jouannet S., Boucheix C., Rubinstein E. (2014). Tetraspanins at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 127(Pt 17), 3641–3648. 10.1242/jcs.154906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Ma L., Yu L. (2019). WGA is a probe for migrasomes. Cell Discov. 5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Li Y., Ma L., Yu L. (2018). Detection of migrasomes. Methods Mol. Biol. 1749 43–49. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7701-7_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo M., Raposo G., Thery C. (2014). Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 30 255–289. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland B. T., Bowman M. J., Ashman L. K. (2013a). Genetic ablation of the tetraspanin CD151 reduces spontaneous metastatic spread of prostate cancer in the TRAMP model. Mol. Cancer Res. 11 95–105. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland B. T., Bowman M. J., Boucheix C., Ashman L. K. (2013b). Knockout of the tetraspanin Cd9 in the TRAMP model of de novo prostate cancer increases spontaneous metastases in an organ-specific manner. Int. J. Cancer 133 1803–1812. 10.1002/ijc.28204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culp L. A., Black P. H. (1972). Release of macromolecules from BALB-c mouse cell lines treated with chelating agents. Biochemistry 11 2161–2172. 10.1021/bi00761a024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culp L. A., Murray B. A., Rollins B. J. (1979). Fibronectin and proteoglycans as determinants of cell-substratum adhesion. J. Supramol. Struct. 11 401–427. 10.1002/jss.400110314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha-Azevedo B., Schmid S. L. (2015). Migrasomes: a new organelle of migrating cells. Cell Res. 25 1–2. 10.1038/cr.2014.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deissler H., Kuhn E. M., Lang G. E., Deissler H. (2007). Tetraspanin CD9 is involved in the migration of retinal microvascular endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 20 643–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X., Li Q., Hoff J., Novak M., Yang H., Jin H., et al. (2012). Integrin-associated CD151 drives ErbB2-evoked mammary tumor onset and metastasis. Neoplasia 14 678–689. 10.1593/neo.12922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle E. L., Ridger V., Ferraro F., Turmaine M., Saftig P., Cutler D. F. (2011). CD63 is an essential cofactor to leukocyte recruitment by endothelial P-selectin. Blood 118 4265–4273. 10.1182/blood-2010-11-321489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eelen G., de Zeeuw P., Treps L., Harjes U., Wong B. W., Carmeliet P. (2018). Endothelial cell metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 98 3–58. 10.1152/physrev.00001.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H., Tan J., Yin Q. (2015). Effects of recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated CD151 gene transfer on the expression of rat vascular endothelial growth factor in ischemic myocardium. Exp. Ther. Med. 9 187–190. 10.3892/etm.2014.2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Frigola C., Burgaya F., Calbet M., de Lecea L., Soriano E. (2000). Mouse Tspan-5, a member of the tetraspanin superfamily, is highly expressed in brain cortical structures. Neuroreport 11 3181–3185. 10.1097/00001756-200009280-00027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Frigola C., Burgaya F., de Lecea L., Soriano E. (2001). Pattern of expression of the tetraspanin Tspan-5 during brain development in the mouse. Mech. Dev. 106 207–212. 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00436-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesierich S., Berezovskiy I., Ryschich E., Zoller M. (2006). Systemic induction of the angiogenesis switch by the tetraspanin D6.1A/CO-029. Cancer Res. 66 7083–7094. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-06-0391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haining E. J., Yang J., Bailey R. L., Khan K., Collier R., Tsai S., et al. (2012). The TspanC8 subgroup of tetraspanins interacts with A disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10) and regulates its maturation and cell surface expression. J. Biol. Chem. 287 39753–39765. 10.1074/jbc.M112.416503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halper J. (2018). Basic components of vascular connective tissue and extracellular matrix. Adv. Pharmacol. 81 95–127. 10.1016/bs.apha.2017.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemler M. E. (2003). Tetraspanin proteins mediate cellular penetration, invasion, and fusion events and define a novel type of membrane microdomain. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19 397–422. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.153609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemler M. E. (2005). Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6 801–811. 10.1038/nrm1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemler M. E. (2008). Targeting of tetraspanin proteins–potential benefits and strategies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7 747–758. 10.1038/nrd2659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemler M. E. (2014). Tetraspanin proteins promote multiple cancer stages. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14 49–60. 10.1038/nrc3640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo K., Lee S. (2020). TSPAN8 as a novel emerging therapeutic target in cancer for monoclonal antibody therapy. Biomolecules 10:388. 10.3390/biom10030388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr M. J., Mabry S. E., Jennings L. K. (2014). Tetraspanin CD9 regulates cell contraction and actin arrangement via RhoA in human vascular smooth muscle cells. PLoS One 9:e106999. 10.1371/journal.pone.0106999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Xu Q. (2011). Adventitial biology: differentiation and function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31 1523–1529. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Zucker B., Zhang S., Elias S., Zhu Y., Chen H., et al. (2019). Migrasome formation is mediated by assembly of micron-scale tetraspanin macrodomains. Nat. Cell Biol. 21 991–1002. 10.1038/s41556-019-0367-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Miao X., Patarroyo M., Nilsson G. P., Pernow J., Li N. (2016). Tetraspanin CD151 and integrin alpha6beta1 mediate platelet-enhanced endothelial colony forming cell angiogenesis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 14 606–618. 10.1111/jth.13248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim A., Marban E. (2016). Exosomes: fundamental biology and roles in cardiovascular physiology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 78 67–83. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-104929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki T., Takeda Y., Maruyama K., Yokosaki Y., Tsujino K., Tetsumoto S., et al. (2013). Deletion of tetraspanin CD9 diminishes lymphangiogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 288 2118–2131. 10.1074/jbc.M112.424291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen D. K., Fenix A. M., Franklin J. L., Higginbotham J. N., Zhang Q., Zimmerman L. J., et al. (2019). Reassessment of exosome composition. Cell 177 428–445.e18. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D., Jiang Z., Lu D., Wang X., Liang H., Zhang J., et al. (2019). Migrasomes provide regional cues for organ morphogenesis during zebrafish gastrulation. Nat. Cell Biol. 21 966–977. 10.1038/s41556-019-0358-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge H. J., Yang S., Burton J. B., Paes K., Shu X., French D. M., et al. (2009). TSPAN12 regulates retinal vascular development by promoting Norrin- but not Wnt-induced FZD4/beta-catenin signaling. Cell 139 299–311. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R., LeBleu V. S. (2020). The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 367:eaau6977. 10.1126/science.aau6977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamisasanuki T., Tokushige S., Terasaki H., Khai N. C., Wang Y., Sakamoto T., et al. (2011). Targeting CD9 produces stimulus-independent antiangiogenic effects predominantly in activated endothelial cells during angiogenesis: a novel antiangiogenic therapy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 413 128–135. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller R. (2005). Cell migration during gastrulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17 533–541. 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Soyer C., Azorsa D. O., Cazenave J. P., Lanza F. (2000). CD9 participates in endothelial cell migration during in vitro wound repair. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20 360–369. 10.1161/01.atv.20.2.360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko E. M., Lee I. Y., Cheon I. S., Kim J., Choi J. S., Hwang J. Y., et al. (2006). Monoclonal antibody to CD9 inhibits platelet-induced human endothelial cell proliferation. Mol. Cells 22 70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotha J., Zhang C., Longhurst C. M., Lu Y., Jacobs J., Cheng Y., et al. (2009). Functional relevance of tetraspanin CD9 in vascular smooth muscle cell injury phenotypes: a novel target for the prevention of neointimal hyperplasia. Atherosclerosis 203 377–386. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M. B., Zhang C., Shi J., Johnson V., Khandan L., McVey J., et al. (2017). TSPAN12 is a norrin co-receptor that amplifies Frizzled4 ligand selectivity and signaling. Cell Rep. 19 2809–2822. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Clainche C., Carlier M. F. (2008). Regulation of actin assembly associated with protrusion and adhesion in cell migration. Physiol. Rev. 88 489–513. 10.1152/physrev.00021.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S., Shoham T. (2005). The tetraspanin web modulates immune-signalling complexes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5 136–148. 10.1038/nri1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K. (2011). CD63 positions CD62P for rolling. Blood 118 4012–4013. 10.1182/blood-2011-08-372318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Yang X. H., Xu F., Sharma C., Wang H. X., Knoblich K., et al. (2013). Tetraspanin CD151 plays a key role in skin squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene 32 1772–1783. 10.1038/onc.2012.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. F., Zuo H. J., Chai B. L., Peng D., Fei Y. J., Lin J. Y., et al. (2011). Role of tetraspanin CD151-alpha3/alpha6 integrin complex: implication in angiogenesis CD151-integrin complex in angiogenesis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 43 642–650. 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Chen H., Liu D. (2014). Mechanistic perspectives of calorie restriction on vascular homeostasis. Sci. China Life Sci. 57 742–754. 10.1007/s11427-014-4709-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Li Y., Peng J., Wu D., Zhao X., Cui Y., et al. (2015). Discovery of the migrasome, an organelle mediating release of cytoplasmic contents during cell migration. Cell Res. 25 24–38. 10.1038/cr.2014.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsboom G., Rehman J. (2018). Hypoxia signaling in vascular homeostasis. Physiology 33 328–337. 10.1152/physiol.00018.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews A. L., Koo C. Z., Szyroka J., Harrison N., Kanhere A., Tomlinson M. G. (2018). Regulation of leukocytes by TspanC8 tetraspanins and the “molecular scissor” ADAM10. Front. Immunol. 9:1451. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis U. R. (2014). Mechanisms of endothelial cell migration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71 4131–4148. 10.1007/s00018-014-1678-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos M. P., John N., Grabner R., Nossmann S., Gunther B., Vollandt R., et al. (2005). The lamina adventitia is the major site of immune cell accumulation in standard chow-fed apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25 2386–2391. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000187470.31662.fe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau H. D., Piel M., Voituriez R., Lennon-Dumenil A. M. (2018). Integrating physical and molecular insights on immune cell migration. Trends Immunol. 39 632–643. 10.1016/j.it.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu W., Provaznik J., Hackert T., Zoller M. (2020). Tspan8-tumor extracellular vesicle-induced endothelial cell and fibroblast remodeling relies on the target cell-selective response. Cells 9:E319. 10.3390/cells9020319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnai G., Tombaccini D., Ruggieri S. (1984). Ganglioside composition of substrate-adhesion sites of normal and virally-transformed Balb/c 3T3 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 125 142–148. 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80346-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray B. A., Culp L. A. (1981). Multiple and masked pools of fibronectin in murine fibroblast cell–substratum adhesion sites. Exp. Cell Res. 131 237–249. 10.1016/0014-4827(81)90229-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao K., Oka K. (2011). HIF-2 directly activates CD82 gene expression in endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 407 260–265. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarenko I., Rana S., Baumann A., McAlear J., Hellwig A., Trendelenburg M., et al. (2010). Cell surface tetraspanin Tspan8 contributes to molecular pathways of exosome-induced endothelial cell activation. Cancer Res. 70 1668–1678. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikopoulos K., Gilissen C., Hoischen A., van Nouhuys C. E., Boonstra F. N., Blokland E. A., et al. (2010). Next-generation sequencing of a 40 Mb linkage interval reveals TSPAN12 mutations in patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 86 240–247. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninds Stroke Genetics Network [SIGN], and International Stroke Genetics Consortium [ISGC] (2016). Loci associated with ischaemic stroke and its subtypes (SiGN): a genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 15 174–184. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00338-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noy P. J., Gavin R. L., Colombo D., Haining E. J., Reyat J. S., Payne H., et al. (2019). Tspan18 is a novel regulator of the Ca(2+) channel orai1 and von willebrand factor release in endothelial cells. Haematologica 104 1892–1905. 10.3324/haematol.2018.194241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer S. B., Humphreys T. (1971). Isolation of specific macromolecules required for adhesion of mouse tumour cells. Nature 232 125–127. 10.1038/232125a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegtel D. M., Gould S. J. (2019). Exosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 88 487–514. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penas P. F., Garcia-Diez A., Sanchez-Madrid F., Yanez-Mo M. (2000). Tetraspanins are localized at motility-related structures and involved in normal human keratinocyte wound healing migration. J. Invest. Dermatol. 114 1126–1135. 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00998.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng D., Zuo H., Liu Z., Qin J., Zhou Y., Li P., et al. (2013). The tetraspanin CD151-ARSA mutant inhibits angiogenesis via the YRSL sequence. Mol. Med. Rep. 7 836–842. 10.3892/mmr.2012.1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pileri P., Uematsu Y., Campagnoli S., Galli G., Falugi F., Petracca R., et al. (1998). Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science 282 938–941. 10.1126/science.282.5390.938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter K. R., Claude A., Fullam E. F. (1945). A study of tissue culture cells by electron microscopy: methods and preliminary observations. J. Exp. Med. 81 233–246. 10.1084/jem.81.3.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potente M., Gerhardt H., Carmeliet P. (2011). Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell 146 873–887. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana S., Zoller M. (2011). Exosome target cell selection and the importance of exosomal tetraspanins: a hypothesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39 559–562. 10.1042/bst0390559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan P., Kumari R., Verma S. K. (2019). Cardiac fibroblasts and cardiac fibrosis: precise role of exosomes. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 7:318. 10.3389/fcell.2019.00318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlena J., Volger O. L., van Buul J. D., Hekking L. H., van Gils J. M., Bonta P. I., et al. (2009). Endothelial CD81 is a marker of early human atherosclerotic plaques and facilitates monocyte adhesion. Cardiovasc. Res. 81 187–196. 10.1093/cvr/cvn256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins B. J., Culp L. A. (1979). Glycosaminoglycans in the substrate adhesion sites of normal and virus-transformed murine cells. Biochemistry 18 141–148. 10.1021/bi00568a022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J. J., Culp L. A. (1977). Morphology and cellular origins of substrate-attached material from mouse fibroblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 107 139–149. 10.1016/0014-4827(77)90395-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein E. (2011). The complexity of tetraspanins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39 501–505. 10.1042/BST0390501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherberich A., Moog S., Haan-Archipoff G., Azorsa D. O., Lanza F., Beretz A. (1998). Tetraspanin CD9 is associated with very late-acting integrins in human vascular smooth muscle cells and modulates collagen matrix reorganization. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 18 1691–1697. 10.1161/01.atv.18.11.1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Pogoda A., Strecker J. K., Liebmann M., Massoth C., Beuker C., Hansen U., et al. (2018). Dietary salt promotes ischemic brain injury and is associated with parenchymal migrasome formation. PLoS One 13:e0209871. 10.1371/journal.pone.0209871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober A. (2008). Chemokines in vascular dysfunction and remodeling. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28 1950–1959. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.161224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S. H., Kim M. J., Park S. W., Kim J. H., Yu Y. S., Song J. Y., et al. (2016). Large deletions of TSPAN12 cause familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR). Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57 6902–6908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sincock P. M., Fitter S., Parton R. G., Berndt M. C., Gamble J. R., Ashman L. K. (1999). PETA-3/CD151, a member of the transmembrane 4 superfamily, is localised to the plasma membrane and endocytic system of endothelial cells, associates with multiple integrins and modulates cell function. J. Cell Sci. 112(Pt 6), 833–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo A., Mayor R. (2018). Mechanisms of neural crest migration. Annu. Rev. Genet. 52 43–63. 10.1146/annurev-genet-120417-031559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y., Kazarov A. R., Butterfield C. E., Hopkins B. D., Benjamin L. E., Kaipainen A., et al. (2007). Deletion of tetraspanin Cd151 results in decreased pathologic angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Blood 109 1524–1532. 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y., Li Q., Kazarov A. R., Epardaud M., Elpek K., Turley S. J., et al. (2011). Diminished metastasis in tetraspanin CD151-knockout mice. Blood 118 464–472. 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavano S., Heisenberg C. P. (2019). Migrasomes take center stage. Nat. Cell Biol. 21 918–920. 10.1038/s41556-019-0369-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. C., Robbins E. (1963). Observations on microextensions from the surface of isolated vertebrate cells. Dev. Biol. 6 660–673. 10.1016/0012-1606(63)90150-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejera E., Rocha-Perugini V., Lopez-Martin S., Perez-Hernandez D., Bachir A. I., Horwitz A. R., et al. (2013). CD81 regulates cell migration through its association with Rac GTPase. Mol. Biol. Cell 24 261–273. 10.1091/mbc.E12-09-0642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry A. H., Culp L. A. (1974). Substrate-attached glycoproteins from normal and virus-transformed cells. Biochemistry 13 414–425. 10.1021/bi00700a004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y., Ye C., Ren X. S., Qiu Y., Zang Y. H., Xiong X. Q., et al. (2018). Exosome-mediated transfer of ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) from adventitial fibroblasts of spontaneously hypertensive rats promotes vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Hypertension 72 881–888. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugues S., Honjo S., Konig C., Padhan N., Kroon J., Gualandi L., et al. (2013). Tetraspanin CD63 promotes vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2-beta1 integrin complex formation, thereby regulating activation and downstream signaling in endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 288 19060–19071. 10.1074/jbc.M113.468199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda R., Satouh Y., Takemoto M., Nakada-Nakura Y., Liu K., Yokoyama T., et al. (2020). Structural insights into tetraspanin CD9 function. Nat. Commun. 11:1606. 10.1038/s41467-020-15459-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Niel G., D’Angelo G., Raposo G. (2018). Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19 213–228. 10.1038/nrm.2017.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vischer U. M., Wagner D. D. (1993). CD63 is a component of Weibel-Palade bodies of human endothelial cells. Blood 82 1184–1191. 10.1182/blood.v82.4.1184.1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Jacquet L., Karamariti E., Xu Q. (2015). Origin and differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Physiol. 593 3013–3030. 10.1113/JP270033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Yang J., Liu Z. X., Chen B., Liu J., Lan R. F., et al. (2006). [Gene transfer of CD151 enhanced myocardial angiogenesis and improved cardiac function in rats with experimental myocardial infarction]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 34 159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Q., Zhang F., Richardson M. M., Roy N. H., Rodgers W., Liu Y., et al. (2014). CD82 restrains pathological angiogenesis by altering lipid raft clustering and CD44 trafficking in endothelial cells. Circulation 130 1493–1504. 10.1161/circulationaha.114.011096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilting J., Chao T. I. (2015). “Integrated vascular anatomy,” in PanVascular Medicine, ed. Lanzer P. (Berlin: Springer; ), 193–241. 10.1007/978-3-642-37078-6_252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D., Xu Y., Ding T., Zu Y., Yang C., Yu L. (2017). Pairing of integrins with ECM proteins determines migrasome formation. Cell Res. 27 1397–1400. 10.1038/cr.2017.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M., Mugnai G., Serada S., Yagi Y., Naka T., Sekiguchi K. (2013). Substrate-attached materials are enriched with tetraspanins and are analogous to the structures associated with rear-end retraction in migrating cells. Cell Adh. Migr. 7 304–314. 10.4161/cam.25041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez-Mo M., Alfranca A., Cabanas C., Marazuela M., Tejedor R., Ursa M. A., et al. (1998). Regulation of endothelial cell motility by complexes of tetraspan molecules CD81/TAPA-1 and CD151/PETA-3 with alpha3 beta1 integrin localized at endothelial lateral junctions. J. Cell Biol. 141 791–804. 10.1083/jcb.141.3.791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez-Mo M., Barreiro O., Gonzalo P., Batista A., Megias D., Genis L., et al. (2008). MT1-MMP collagenolytic activity is regulated through association with tetraspanin CD151 in primary endothelial cells. Blood 112 3217–3226. 10.1182/blood-2008-02-139394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez-Mo M., Barreiro O., Gordon-Alonso M., Sala-Valdes M., Sanchez-Madrid F. (2009). Tetraspanin-enriched microdomains: a functional unit in cell plasma membranes. Trends Cell Biol. 19 434–446. 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Xiao X., Li S., Mai G., Zhang Q. (2011). Novel TSPAN12 mutations in patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and their associated phenotypes. Mol. Vis. 17 1128–1135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Lai M. B., Pedler M. G., Johnson V., Adams R. H., Petrash J. M., et al. (2018). Endothelial cell-specific inactivation of TSPAN12 (tetraspanin 12) reveals pathological consequences of barrier defects in an otherwise intact vasculature. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 38 2691–2705. 10.1161/atvbaha.118.311689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Kotha J., Jennings L. K., Zhang X. A. (2009). Tetraspanins and vascular functions. Cardiovasc. Res. 83 7–15. 10.1093/cvr/cvp080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Michaelson J. E., Moshiach S., Sachs N., Zhao W., Sun Y., et al. (2011). Tetraspanin CD151 maintains vascular stability by balancing the forces of cell adhesion and cytoskeletal tension. Blood 118 4274–4284. 10.1182/blood-2011-03-339531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. A., Huang C. (2012). Tetraspanins and cell membrane tubular structures. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69 2843–2852. 10.1007/s00018-012-0954-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. A., Kazarov A. R., Yang X., Bontrager A. L., Stipp C. S., Hemler M. E. (2002). Function of the tetraspanin CD151-alpha6beta1 integrin complex during cellular morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 13 1–11. 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. X., Xu J. T., You X. C., Wang C., Zhou K. W., Li P., et al. (2016). Inhibitory effects of hydrogen on proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells via down-regulation of mitogen/activated protein kinase and ezrin-radixin-moesin signaling pathways. Chin. J. Physiol. 59 46–55. 10.4077/CJP.2016.BAE365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Dong E. (2014). New insight into vascular homeostasis and injury-reconstruction. Sci. China Life Sci. 57 739–741. 10.1007/s11427-014-4719-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li H. (2017). Reprogramming interferon regulatory factor signaling in cardiometabolic diseases. Physiology 32 210–223. 10.1152/physiol.00038.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Tan S., Xu J., Wang T. (2018). Hydrogen therapy in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases: from bench to bedside. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 47 1–10. 10.1159/000489737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhang X. J., Li H. (2017). Targeting interferon regulatory factor for cardiometabolic diseases: opportunities and challenges. Curr. Drug Targets 18 1754–1778. 10.2174/1389450116666150804110412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Wu W., Zhang W., Lu Y. W., Tou E., Ye J., et al. (2017). Selective expression of TSPAN2 in vascular smooth muscle is independently regulated by TGF-beta1/SMAD and myocardin/serum response factor. FASEB J. 31 2576–2591. 10.1096/fj.201601021R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K., Erb U., Hackert T., Zoller M., Yue S. (2018a). Distorted leukocyte migration, angiogenesis, wound repair and metastasis in Tspan8 and Tspan8/CD151 double knockout mice indicate complementary activities of Tspan8 and CD51. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1865 379–391. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K., Wang Z., Hackert T., Pitzer C., Zoller M. (2018b). Tspan8 and Tspan8/CD151 knockout mice unravel the contribution of tumor and host exosomes to tumor progression. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 37:312. 10.1186/s13046-018-0961-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zhao X., Lei Y., Zheng J., Peng J., Li Y., Yu L., et al. (2019). Identification of markers for migrasome detection. Cell Discov. 5:27. 10.1038/s41421-019-0093-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman B., Kelly B., McMillan B. J., Seegar T. C. M., Dror R. O., Kruse A. C., et al. (2016). Crystal structure of a full-length human tetraspanin reveals a cholesterol-binding pocket. Cell 167 1041–1051.e11. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoller M. (2009). Tetraspanins: push and pull in suppressing and promoting metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9 40–55. 10.1038/nrc2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo H. J., Lin J. Y., Liu Z. Y., Liu W. F., Liu T., Yang J., et al. (2010). Activation of the ERK signaling pathway is involved in CD151-induced angiogenic effects on the formation of CD151-integrin complexes. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 31 805–812. 10.1038/aps.2010.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo H. J., Liu Z. X., Liu X. C., Yang J., Liu T., Wen S., et al. (2009). Assessment of myocardial blood perfusion improved by CD151 in a pig myocardial infarction model. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 30 70–77. 10.1038/aps.2008.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.