Abstract

Objective

Vascular endothelium plays a fundamental role in regulating endothelial dysfunction, resulting in structural changes that may lead to adverse outcomes of hypertension. The aim of this study was to systematically evaluate the effect of a combination of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) and Western medicine on vascular endothelial function in patients with hypertension.

Methods

We systematically searched the literature for studies published in Chinese and English in PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database, Wanfang Data, and China Science and Technology Journal Database. Databases were searched using terms concerning or describing CHM, hypertension, vascular endothelium, and randomized controlled trials. RevMan 5.3.0 was used for data analysis. If the included studies were sufficiently homogeneous, quantitative synthesis was performed; if studies with different sample sizes and blind methods were used, subgroup analyses were performed. GRADEpro was selected to grade the current evidence to reduce bias in our findings.

Results

In this review, 30 studies with 3,235 patients were enrolled. A relatively high selection and a performance bias were noted by risk of bias assessments. Meta-analysis showed that the combination of CHM and conventional Western medicine was more efficient than conventional Western medicine alone in lowering blood pressure (risk ratio, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.16 to 1.26) and increasing nitric oxide (95% CI, 1.24 to 2.08; P < 0.00001), endothelin-1 (95% CI, −1.71 to −1.14; P < 0.00001), and flow-mediated dilation (95% CI, 0.98 to 1.31; P <0.00001). No significant difference was observed between the combination of CHM and conventional Western medicine and conventional Western medicine alone for major cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. CHM qualified for the treatment of hypertension. The GRADEpro presented with low quality of evidence for the available data.

Conclusion

CHM combined with conventional Western medicine may be effective in lowering blood pressure and improving vascular endothelial function in patients with hypertension. To further confirm this, more well-designed studies with large sample sizes, strict randomization, and clear descriptions about detection and reporting processes are warranted.

Keywords: blood pressure, hypertension, Traditional Chinese Medicine, systematic review, meta-analysis

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the primary cause of death- and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) worldwide and is responsible for 12.9 million deaths and 0.3 billion DALYs each year (Lozano et al., 2012; Murray et al., 2012), for which high blood pressure (BP) is the strongest risk factor (Writing Group et al., 2016). In 2015, 1.13 billion individuals were reported to have CVDs worldwide (Collaboration, 2017). The vascular endothelium plays a fundamental role in regulating the vascular tone and structure as well as endothelial dysfunction, resulting in structural changes that may lead to adverse outcomes of hypertension (Juonala et al., 2006). Well-maintained endothelial function and integrity are of great significance in numerous conditions, including hypertension, inflammatory and cardiovascular diseases, and their risk factors (Sattar et al., 2003; Touyz and Briones, 2011).

Antihypertensive agents, including diuretics, beta-adrenergic blocking agents (β-blockers), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are mostly used in the treatment of CVDs. However, around half of the patients are incapable of effectively controlling their BP by drug therapy owing to the associated cost, adverse reactions, and complications (Shaw et al., 1995). Behavioral interventions, such as exercise, weight loss, and salt intake casn control and help lower the BP, but these are hard to comply with.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has proven to be an important part of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) because of efficacious clinical practice in China, although its mechanism remains unclear (Harris et al., 2012). Many studies have shown that hypertension can be effectively managed by Chinese herbal medicine (CHM), acupuncture, and tai chi (Shih et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2007; Yin et al., 2007; Kim and Zhu, 2010). In clinics, patients with essential hypertension are commonly treated with CHM combined with antihypertensive agents. However, there is no systematic summary available of the RCTs examining the efficacy of CHM plus antihypertensive drugs (CPAD) for vascular endothelial function in patients with essential hypertension. Thus, to critically assess the efficacy of CPAD for essential hypertension, we performed this systematic review.

Methods

This meta-analysis was carried out and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2010). A protocol has been registered in PROSPERO for this review (registration number: CRD42019140743).

Inclusion Criteria

Participants

In this meta-analysis, we did not restrict based on patient's age, gender, course of disease, case source, nationality, or race. In the original literature, the definition of hypertension is consistent with past guidelines (systolic BP [SBP] ≥140 mmHg or diastolic BP [DBP] ≥90 mmHg) (Hypertension Alliance (China) et al., 2019). The exclusion criteria included (a) subjects with hypertension complicated by other serious CVDs, hepatic failure, or renal failure, (b) secondary hypertension, (c) gestational hypertension, or (d) isolated systolic hypertension.

Intervention

According to the 2015-edition of the Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China, compiled by the China Food and Drug Administration, CHM was defined as herbal agents and materials derived from the botanical herbal products, minerals, and animal sources. CHMs were prepared into various forms such as decoctions, tablets, pills, powders, granules, capsules, oral liquids, and injections. Based on the TCM pattern identification and treatment by experienced doctors, usually a compound formula consists of two or more herbs to obtain a synergistic effect under certain circumstances. All types of CPADs without considering the dose, method of dosing, composition of the formula, or time of drug administration were compared with the Western medicine. The comparisons included in this study were as follows: (a) CHM combined with CCB vs CCB; (b) CHM combined with ACEI vs ACEI; (c) CHM combined with ARB vs ARB; (d) CHM combined with diuretic vs diuretic; (e) CHM combined with multiple antihypertensive drugs (CCB/ACEI/ARB/diuretic/β-blocker) vs multiple antihypertensive drugs.

Control

As mentioned above, the control could be CCB, ACEI, ARB, diuretic, β-blocker alone, or multiple antihypertensive drugs.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were 24 h ambulatory BP monitoring (24 h-SBP and 24 h-DBP), SBP, DBP, and therapeutic effectiveness with reference to the standards of Chinese Medicine Clinical Research of New Drugs Guiding Principles. Marked effectiveness was considered as: DBP decreased ≥20 mmHg but did not reach normal level; or 10 mmHg ≤ DBP decrease < 20 mmHg and reached normal level; BP decrease <10 mmHg with normal level; or 10 mmHg ≤ DBP decrease < 20 mmHg but did not reach normal level; or SBP decrease ≥ 30 mmHg but did not reach normal level; ineffectiveness: DBP decreased < 20 mmHg and did not reach normal levels. Secondary outcomes were nitric oxide (NO), endothelin-1 (ET-1), flow-mediated dilation (FMD), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), angiotensin II (Ang II), von Willebrand factor (vWF), and transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ-1). Among them, NO protects the vascular endothelial function, whereas increase in ET-1, VEGF, hs-CRP, Ang II, vWF, and TGFβ-1 adversely affects vascular endothelial function. The decrease in FMD indicates an impairment of the vascular endothelial function.

Study Type

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that combined CHM with antihypertensive drugs to treat hypertensive patients regardless of blinding, were included. To minimize publication bias, there was no restriction on language and time.

Literature Searches

We conducted a systematic search of studies published in Chinese and English using the following databases: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials(CENTRAL), Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database (CNKI), Wanfang Data, and China Science and Technology Journal Database (VIP). These databases were searched from inception to April 2019. Terms related to CHM, hypertension, and RCTs were searched in these databases. The search was not restricted by language or publication dates. The search strategy that suited each database was as follows: (“Hypertension” OR “High Blood Pressure”) AND (“Endothelium, Vascular” OR “Endothelium”) AND (“Medicine, Chinese Traditional” OR “Drugs, Chinese Herbal” OR “Traditional Chinese Medicine” OR “Chinese medicine” OR “Chinese medica” OR “Chinese drug” OR “Chinese patent medicine” OR “CHM” OR “Herbal medicine” OR “Chinese Herbal Drug” OR “Chinese Plant Extract”).

After removing duplicates, two investigators independently screened the titles and abstracts of the articles obtained via initial search for relevance. Abstracts that did not meet our criteria were excluded, and few abstracts with insufficient information regarding the inclusion criteria were further reviewed. The full texts of the remaining results were further determined by the same investigators but by blinding to each other's review. All disagreements were resolved by consensus. The flow chart of the study selection is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and study selection.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted in duplicate by two investigators independently and were inputted to a dedicated database. The data extracted from each article included basic information (study ID, document type, author, and publication year), participant's demographic details (sample size, age, and sex), diagnostic criteria, inclusion and exclusion criteria, study drug and control treatment, outcomes, fall outs, follow-up duration, and outcomes. Disagreements regarding the extracted data were settled by a third reviewer (AAN).

Risk of Bias Assessment

We used the Cochrane Collaboration “risk of bias” (ROB) tool for ROB assessment. Referring to the Cochrane Handbook criteria for assessing ROB in the ROB assessment tool, two investigators independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using RevMan 5.3.0. Following the handbook, the assessment of ROB was graded as low, unclear, or high based on the following seven aspects: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcomes assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcomes data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other biases. All differences during ROB assessment were resolved by consensus.

Statistical Analyses

RevMan 5.3.0 was used to analyze the results of this study. For binary data, estimates were described as relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous data, the weighted mean difference (MD) or standard mean difference (SMD) and 95% CIs were calculated. Only complete case data were selected for further analysis. Heterogeneity between the studies in effect measures was assessed using both the chi-squared test and the I2 statistic (Higgins et al., 2003) with an I2 value >50%, indicative of substantial heterogeneity. Sufficiently homogeneous distribution allowed the use of quantitative synthesis in both statistics and clinic. When the I2 value was lower than 50% and P >0.10, a fixed-effect model was adopted; otherwise, a random-effect model was suitable.

Because of significant heterogeneity in primary outcomes, studies with different sample sizes and bindings were subjected to separate subgroup analyses. As few results of the subgroup analysis revealed low methodological quality of the included studies and significant positive results, no further sensitivity analyses were performed.

As the least number of studies in each project was 10, a funnel plot was drawn to detect publication bias. To minimize bias in our findings, we selected the online software GRADEpro to summarize findings for outcomes to evaluate the available evidence. The assessment included biases including risk, inconsistency (heterogeneity), indirect, imprecision, and publication biases; each evidence was graded as very low, low, moderate, or high.

Results

Literature Screening

Herein, we have described the literature retrieval process. A total of 578 potentially relevant articles from seven electronic databases were retrieved after the literature search. After removal of duplicates, 395 articles were identified. After going through the titles and abstracts, 272 articles that were case reports, case series, reviews, and animal studies irrelevant to hypertension were excluded. After reading the full text of the remaining 123 articles, 93 studies were further removed for at least one of the following reasons: no RCT (n = 11); participants failing to meet the inclusion criteria (n = 24); duplicates (n = 4); therapeutic measures failing to meet the predetermined inclusion criteria (n = 28), no Western medicine used in the control group (n = 5), and no BP data for extraction (n = 21). Thirty articles in accordance with the inclusion criteria were identified.

Characteristics of Included Studies

The enrolled 30 articles were published between 2010 and 2019, in which all studies related to comparison of CPAD group vs antihypertensive drug group (Control group). In the CPAD group, the standard, type, and dosage of antihypertensive drugs used were identical to those in the control group.

In total, 3,235 patients were randomly divided into a CPAD group and a control group, all of whom were from China, including 1,388 women. The average age of the participants ranged from 36.0 to 77.3 years. All trials could be accessed via full texts. Treatment duration lasted 4–24 weeks, and most of them lasted 8 weeks (11/30, 37%). The primary outcomes measure was reported. Among them, a 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring was reported in seven studies (Xu et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2014; Weng and Lin, 2015; Teng et al., 2016; Cao et al., 2019; Sun, 2019), SBP and DBP in 24 (Xu et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2012; Qian et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Ou and Li, 2014; Lu et al., 2015; Zhang, 2015; Bian, 2016; Feng et al., 2016; Sheng and Wang, 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Zeng W. Y. et al., 2017; Zeng Z. C. et al., 2017; Gao and Li, 2017; Li, 2017; Li et al., 2017; Ruan et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018; Luo, 2018; Shi et al., 2018), treatment efficiency in 16 (Xu et al., 2010; Shen et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Ou and Li, 2014; Lu et al., 2015; Bian, 2016; Sheng and Wang, 2016; Teng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Gao and Li, 2017; Ruan et al., 2017; Zeng W. Y. et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018; Luo, 2018; Sun, 2019), NO in 18 (Xu et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2010; Qian et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014; Zhang, 2015; Bian, 2016; Feng et al., 2016; Sheng and Wang, 2016; Teng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Gao and Li, 2017; Li et al., 2017; Zeng Z. C. et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2018; Cao et al., 2019), ET-1 in 19 (Xu et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2010; Qian et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014; Zhang, 2015; Bian, 2016; Feng et al., 2016; Sheng and Wang, 2016; Teng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Gao and Li, 2017; Li et al., 2017; Zeng W. Y. et al., 2017; Zeng Z. C. et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2018; Cao et al., 2019), FMD in 8 (Gao et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2013; Weng and Lin, 2015; Zhang, 2015; Wu et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Zeng W. Y. et al., 2017; Sun, 2019), VEGF in 5 (Ou and Li, 2014; Lu et al., 2015; Li, 2017; Ruan et al., 2017; Luo, 2018). hsCRP), hs-CRP in 5 (Gao et al., 2012; Qian et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Bian, 2016; Wang et al., 2016), Ang II in 3 (Sheng and Wang, 2016; Zeng Z. C. et al., 2017; Sun, 2019), vWF in 3 (Wu et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Zeng W. Y. et al., 2017), and TGFβ-1 in 2 studies (Ruan et al., 2017; Luo, 2018) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Certainty | NO of patients | Effect | Certainty | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | CHM combined with west medicine | West Medicine |

Relative (95% CI) |

Absolute (95% CI) |

||

| 24 h-SBP | ||||||||||||

| 7 | randomized trials |

seriousa | seriousb | not serious | not serious | none | 408 | 403 | – | SMD 0.85 lower (1.43 lower to 0.26 lower) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW |

CRITICAL |

| 24 h-DBP | ||||||||||||

| 7 | randomized trials |

seriousa | seriousb | not serious | not serious | none | 408 | 403 | – | SMD 0.76 lower (1.29 lower to 0.24 lower) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW |

CRITICAL |

| SBP | ||||||||||||

| 24 | randomized trials |

seriousa | seriousb | not serious | not serious | none | 1,259 | 1,264 | – | MD 8.3 lower (10.4 lower to 6.19 lower) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW |

CRITICAL |

| DBP | ||||||||||||

| 24 | randomized trials |

seriousa | seriousb | not serious | not serious | none | 1,259 | 1,264 | – | SMD 0.93 lower (1.13 lower to 0.74 lower) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW |

CRITICAL |

| NO | ||||||||||||

| 18 | randomized trials |

seriousa | seriousb | not serious | not serious | publication bias strongly suspectedc | 973 | 969 | – | SMD 1.66 higher (1.24 higher to 2.08 higher) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW |

CRITICAL |

| ET-1 | ||||||||||||

| 19 | randomized trials |

seriousa | seriousb | not serious | not serious | none | 1,056 | 1,053 | – | SMD 1.42 lower (1.71 lower to 1.14 lower) |

⨁◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| FMD | ||||||||||||

| 8 | randomized trials |

seriousa | seriousb | not serious | not serious | none | 418 | 424 | MD 1.14 higher (0.98 higher to 1.31 higher) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW |

CRITICAL | |

CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Explanations:

ano-blinded.

I2 >50%.

The funnel plot is asymmetrical.

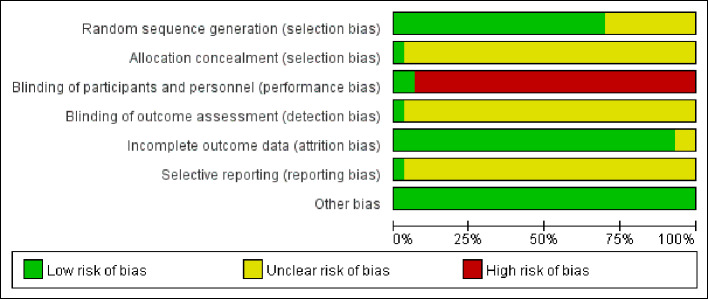

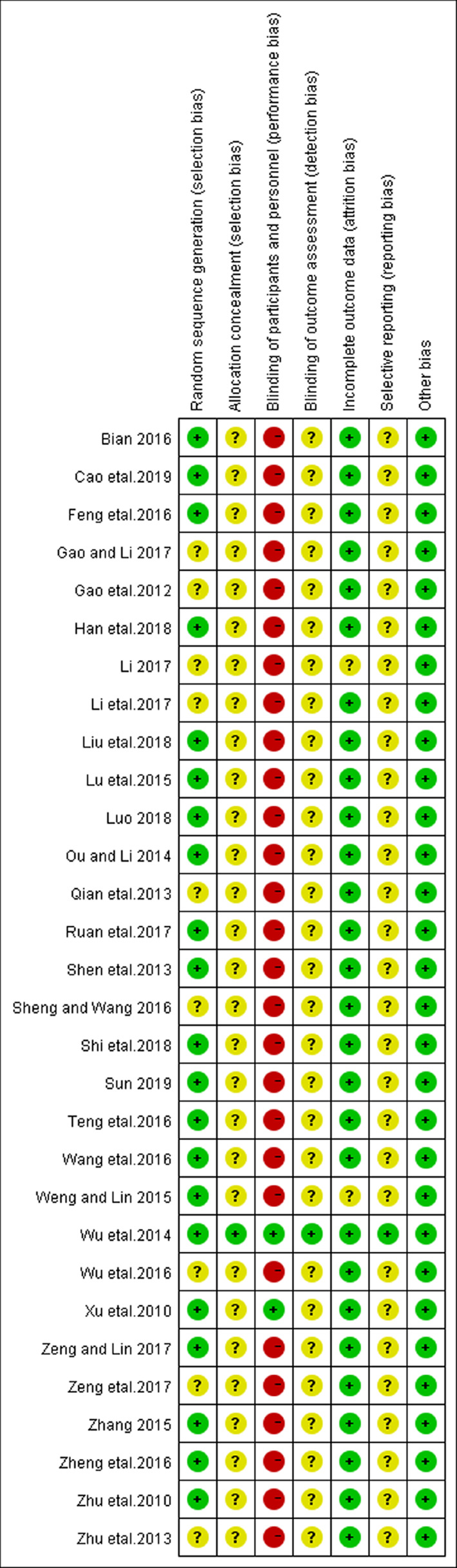

ROB Assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted the data from these included studies and conducted an ROB assessment using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for ROB assessment. In this systematic review, all 30 trials were reported as RCTs. Of 30, 18 reported the generation of the allocation sequence. Among them, 15 used a random number table (Zhu et al., 2010; Shen et al., 2013; Ou and Li, 2014; Lu et al., 2015; Bian, 2016; Feng et al., 2016; Teng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Ruan et al., 2017; Zeng Z. C. et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018; Luo, 2018; Shi et al., 2018), two used a randomization list generated with an SAS software package (Wu et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2019) and one used the stratified block randomization (Sun, 2019). Only one trial (Wu et al., 2014) reported allocation concealment. Two trials reported the use of double blinding (Xu et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2014). Three trials reported withdrawals (Gao et al., 2012; Teng et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016). No protocols for the included studies were available for us to investigate the selective reporting. We found only one study (Wu et al., 2014) that is included in this review to be at low risk for selective reporting, with the remaining 29 studies being assessed as high risk. No other potential sources of bias were detected. The ROB in the included studies is shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: reviewing authors' judgments regarding each risk of bias item for each included study.

Efficacy Analyses

BP

Seven trials (Xu et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2014; Weng and Lin, 2015; Teng et al., 2016; Cao et al., 2019; Sun, 2019) reported the treatment effects on BP, as measured by the 24 h ambulatory BP monitor (24h-SBP and 24h-DBP), including a total of 1,211 patients. We found that 24 h-SBP (I2 = 93%, P < 0.00001) and 24h-DBP (I2 = 92%, P < 0.00001) were highly heterogeneous; thus, we further conducted a subgroup analysis and selected a random-effects model to classify Western medicines for improving 24 h-SBP into CCB (MD = −0.63, 95% CI [−1.07, −0.19], P = 0.005), ACEI (MD = −0.49, 95% CI [−1.00, 0.02], P = 0.06), diuretic (MD = −0.5, 95% CI [−1.01, −0.02], P = 0.06), and combined intervention (MD = −2.4, 95% CI [−2.78, −2.03], P = 0.00001). Meanwhile, Western medicines used to improve 24 h-DBP were also classified into CCB (MD = −0.62, 95% CI [−1.12, −0.12], P = 0.01), ACEI (MD = −0.38, 95% CI [−0.89, 0.13], P = 0.15), diuretic (MD = −0.42, 95% CI [−0.93, 0.09], P = 0.11), and combined intervention (MD = −2.02, 95% CI [−2.38, −1.67], P = 0.00001). Compared with Western medicine, combined with CHM based on CCB and combined intervention could remarkably reduce 24 h-SBPand 24 h-DBP, but CHM combined with ACEI and diuretic showed no obvious improvement (Figures 4A, B).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the comparison between CHM combined with conventional Western medicine and conventional Western medicine alone for (A) 24 h-SBP, (B) 24 h-DBP, (C) SBP, (D) DBP, and (E) therapeutic efficacy.

Twenty-four trials (Xu et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2012; Qian et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Ou and Li, 2014; Lu et al., 2015; Zhang, 2015; Bian, 2016; Feng et al., 2016; Sheng and Wang, 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Gao and Li, 2017; Li, 2017; Li et al., 2017; Ruan et al., 2017; Zeng W. Y. et al., 2017; Zeng Z. C. et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018; Luo, 2018; Shi et al., 2018) reported the therapeutic effects on BP as measured by SBP and DBP, including a total of 2,523 patients. We found that both SBP (I2 = 95%, P <0.00001) and DBP (I2 = 81%, P <0.00001) displayed great heterogeneity. We further conducted a subgroup analysis and selected a random-effects model to classify Western medicines for improving SBP into CCB (MD = −8.83, 95% CI [−11.22, −6.44], P < 0.00001), ACEI (MD = −6.45, 95% CI [−7.89, −5.01], P < 0.00001), ARB (MD = −12.01, 95% CI [−17.52, −6.51], P < 0.00001), and combined intervention (MD = −6.83, 95% CI [−11.96, −1.71], P <0.00001). Meanwhile, Western medicine for improving DBP was divided into CCB (MD = −1.07, 95% CI [−1.27, −0.86], P < 0.00001), ACEI (MD = −0.95, 95% CI −1.77 to −0.13, P = 0.02), ARB (MD = −12.01, 95% CI [−17.52, −6.51], P <0.00001), and combined intervention (MD = −6.83, 95% CI [−11.96, −1.71], P < 0.00001). Compared with Western medicine, combined application of CHM based on CCB, ACEI, ARB, and combined intervention could significantly reduce SBP and DBP (Figures 4C, D).

Sixteen trials reported (Xu et al., 2010; Shen et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Ou and Li, 2014; Lu et al., 2015; Bian, 2016; Sheng and Wang, 2016; Teng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Gao and Li, 2017; Ruan et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018; Luo, 2018; Sun, 2019) reported therapeutic effectiveness, including a total of 1,912 patients. The heterogeneity was low (I2 = 0%, P = 0.89); thus, we selected a fixed-effect model to analyze the therapeutic effectiveness. The efficacy of CHM combined with Western medicine in treating hypertension was significantly higher than that of Western medicine alone. (RR = 1.21, 95% CI [1.16, 1.26], P < 0.00001; Figure 4E).

Vascular Endothelial Function

Eighteen trials reported the treatment effects on NO (Xu et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2010; Qian et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014; Zhang, 2015; Bian, 2016; Feng et al., 2016; Sheng and Wang, 2016; Teng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Gao and Li, 2017; Li et al., 2017; Zeng Z. C. et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2018; Cao et al., 2019), including a total of 1,942 patients. We found that NO had a large heterogeneity (I2 = 94%, P < 0.00001). Then, we conducted a subgroup analysis and selected a random-effects model, and divided the Western medicine used to improve NO into CCB (SMD = 1.02, 95% CI [0.59, 1.45], P < 0.00001), ACEI (SMD = 1.22, 95% CI [0.37, 2.06], P = 0.005), ARB (SMD = 2.31, 95% CI [1.44, 3.17], P < 0.00001), and combined intervention (SMD =2.82, 95% CI [1.57, 4.07], P < 0.00001). Compared with Western medicine, combined application of CHM based on CCB, ACEI, ARB, and combined intervention could significantly improve the NO levels (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the comparison between CHM combined with conventional Western medicine and conventional Western medicine alone for (A) NO, (B) ET-1, (C) FMD, (D) VEGF, (E) hs-CRP, (F) Ang II, (G) vWF, and (H) TGFβ-1.

Nineteen trials, including a total of 2,109 patients, reported the treatment effects on ET-1 (Xu et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2010; Qian et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014; Zhang, 2015; Bian, 2016; Feng et al., 2016; Sheng and Wang, 2016; Teng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Gao and Li, 2017; Li et al., 2017; Zeng W. Y. et al., 2017; Zeng Z. C. et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2018; Cao et al., 2019). ET-1 was associated with high heterogeneity (I2 = 89%, P < 0.00001). We performed a subgroup analysis and selected random-effects model. The Western medicine used to improve ET-1 was divided into CCB (SMD = −1.11, 95% CI [−1.48, −0.75], P < 0.00001), ACEI (SMD = −1.40, 95% CI [−2.08, −0.71], P < 0.00001), ARB (SMD = −2.15, 95% CI [−2.88, −1.42], P < 0.00001), and combined intervention (SMD = −1.44, 95% CI [−1.94, −0.95], P < 0.00001). Compared with Western medicine, combined application of CHM based on CCB, ACEI, ARB, and combined intervention decreased ET-1 levels (Figure 5B).

Eight trials including a total of 842 patients reported treatment effects on FMD (Gao et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2013; Weng and Lin, 2015; Zhang, 2015; Wu et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Zeng W. Y. et al., 2017; Sun, 2019). FMD had a large heterogeneity (I2 = 64%, P = 0.004); therefore, we performed a subgroup analysis and selected the random-effects model. The Western medicine used to improve FMD was divided into CCB (MD = 0.77, 95% CI [0.46, 1.07], P <0.00001), ARB (MD = 0.80, 95% CI [−0.39, 1.99], P = 0.19), diuretic (MD = 2.77, 95% CI [1.10, 4.44], P = 0.001), and combined intervention (MD =1.29, 95% CI [1.09, 1.49], P < 0.00001). Compared with Western medicine, combined application of CHM based on CCB, diuretic, and combined intervention could significantly improve FMD levels, but ARB combined with CHM showed no significant improvement (Figure 5C).

Five trials including a total of 490 patients reported treatment effects on VEGF (Ou and Li, 2014; Lu et al., 2015; Li, 2017; Ruan et al., 2017; Luo, 2018). As VEGF had a large heterogeneity (I2 = 97%, P < 0.00001), we selected a random-effects model. As the number of trials was less than 10, subgroup analysis was not performed. Compared with Western medicine, CPAD could significantly reduce the VEGF levels (SMD = −2.59, 95% CI [−4.05, −1.12], P = 0.0005, Figure 5D).

Five trials including a total of 530 patients reported the treatment effects on hs-CRP (Gao et al., 2012; Qian et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Bian, 2016; Wang et al., 2016). As hs-CRP had a large heterogeneity (I2 = 90%, P < 0.00001), we selected a random-effects model. As the number of trials was less than 10, subgroup analysis was not conducted. Compared with Western medicine alone, CPAD could greatly reduce the hs-CRP levels (SMD = −0.97, 95% CI [−1.56, −0.38], P = 0.001, Figure 5E).

Three trials including 306 patients reported treatment effects on Ang II (Sheng and Wang, 2016; Zeng Z. C. et al., 2017; Sun, 2019). Ang II was associated with high heterogeneity (I2 = 98%, P < 0.00001). We selected random-effects model. As the number of trials was less than 10, subgroup analysis was not continued. Results revealed that compared with Western medicine, CPAD could reduce Ang II level (SMD = −4.01, 95% CI [−6.46, −1.55], P = 0.001, Figure 5F).

Three trials including a total of 387 patients reported the effects of treatment on vWF (Wu et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016; Zeng W.Y. et al., 2017). We found that the heterogeneity in vWF was low (I2 = 0%, P = 0.38), and thus we selected a fixed-effect model. The results showed that compared with Western medicine alone, CPAD could significantly reduce the vWF levels (SMD = −19.55, 95% CI [−22.27, −16.83], P < 0.00001, Figure 5G).

Two trials including 186 patients reported the treatment effects on TGFβ-1 (Ruan et al., 2017; Luo, 2018). We found that its heterogeneity was low (I2 = 0%, P = 0.38). We selected a fixed-effect model. The results showed that compared with the Western medicine alone, CPAD could significantly reduce the TGFβ-1 levels (SMD = −39.54, 95% CI [−55.98, −23.09], P < 0.00001, Figure 5H).

Adverse Event

Of all the included studies, four studies (Gao et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2014; Teng et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016) reported losses to follow, and nine (Wu et al., 2014; Ou and Li, 2014; Lu et al., 2015; Weng and Lin, 2015; Bian, 2016; Wu et al., 2016; Zeng Z. C. et al., 2017; Luo, 2018; Shi et al., 2018) studies reported adverse events. On initial recruitment, there were 3,265 patients whose blood pressures were measured. Altogether, 24 cases failed to follow-up and we finally collected 3,235 cases (99.09%) with complete data. Of nine studies reporting adverse events, five reported no adverse events during the study and three described the frequency of adverse effects in detail. The adverse reactions of the CPAD and control groups included edema of the lower extremity, flushing, and headache. All the reported adverse reactions were not aggravated and they all disappeared after symptomatic treatment.

GRADE Evidence Profile

The GRADE evidence profile and summary of the findings are detailed in Table 2. Due to serious ROB in study methods, the heterogeneity and reporting bias, overall quality of evidence for 24 h-SBP, 24 h-DBP, SBP, DBP, NO, ET-1, and FMD were assessed as very low quality, low quality, indicating that these estimates were uncertain, and further studies are likely to influence our confidence when estimating CHM effects (Table 2).

Table 2.

GRADEpro evidence grading.

| Studies | Total (N) |

Diagnosis standard | Intervention group | Control group | Treatment duration |

Outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size (M/F) |

Age | Intervention | Sample size (M/F) |

Age | Control | |||||

| Wu et al., 2014 | 137 | Chinese guidelines published in 2005 and 2010 for the management of hypertension |

47 (33/14) |

47.58 ± 5.02 | Bushen Qinggan decoction (Gastrodia elata Blume 30 g, Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq. 30 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 30 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 15 g, and bitter butyl tea 15 g) & Control | 45 (29/16) |

48.34 ± 4.25 | amlodipine | 8 weeks | 24 h-SBP, 24 h-DBP, NO, ET-1 |

| Qian et al., 2013 | 72 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2005) | 36 (18/18) |

66.0 ± 8.7 | Jiangzhi Kangyanghua mixture (Reynoutria multiflora (Thunb.) Moldenke, Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge, Forsythia suspensa (Thunb.) Vahl, Pueraria montana var. lobata (Willd.) Maesen & S.M.Almeida ex Sanjappa & Predeep) & Control | 36 (19/17) |

65.8 ± 8.9 | amlodipine + valsartan | 8 weeks | SBP, DBP, NO, ET-1, hs-CRP |

| Gao et al., 2012 | 114 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2005) | 57 (31/26) |

68.42 ± 8.85 | Yindanxinnaotong soft capsule [ginkgo leaves (0.5 g crude drug per capsule) (Ginkgo biloba L., Mant.); miltiorrhiza (0.5 g crude drug per capsule) (Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge); herba erigeromtis (0.3 g crude drug per capsule) (Erigeron breviscapus (Vaniot) Hand.-Mazz.); gynostemma pentaphyllum (0.3 g crude drug per capsule (Ginostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino); hawthorn (0.4 g crude drug per capsule)) Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge); allium sativum (0.4 g crude drug per capsule) (Allium sativum L.); panax notoginseng (0.2 g crude drug per capsule) (Panax notoginseng (Burkill) F.H.Chen); and borneol (0.01 g crude drug per capsule] & Control | 59 (34/25) |

67.69 ± 8.67 | multiple antihypertensive drugs (CCB, ACEI/ARB, β-blocker, diuretic et al.) | 6 months | SBP, DBP, FMD |

| Zhu et al., 2013 | 124 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 62 (35 /27) |

45.4 ± 6.75 | Qingnao Jiangya tablets (Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, Prunella vulgaris L., Sophora japonica L., Magnetitum, Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC., Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge, Whitmanian pigra Whitman, Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv, Senna obtusifolia (L.) H.S.Irwin & Barneby, Pheretima aspergillum (E.Perrier), Hyriopsis cumingii (Lea)) & Control | 62 (34/28) |

44.9 ± 6.97 | captopril | 8 weeks | SBP, DBP, hs-CRP |

| Shen et al., 2013 | 66 | internal medicine | 31 (18/13) |

60.13 ± 8.72 | Tianma Gouteng granules (Gastrodia elata Blume Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq., Concha haliotidis 15 g, Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 10 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan 20 g, Leonurus cardiaca L., Taxillus chinensis (DC.) Danser, Reynoutria multiflora (Thunb.) Moldenke, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa) & Control | 35 (22/13) |

60.09 ± 12.13 | multiple antihypertensive drugs (CCB, ACEI/ARB, β-blocker, diuretic et al.) | 4 weeks | SBP, DBP, FMD |

| Ou and Li, 2014 | 72 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2006) | 34 (17/17) |

49.7 ± 8.9 | Chinese Medicine of Resolving Phlegm and Dredging Collaterals (Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 15 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 15 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 10g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 10 g, Leonurus cardiaca L. 15 g, Lycopus lucidus var. hirtus (Regel) Makino & Nemoto 10 g, Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan 10 g, Gastrodia elata Blume 10 g, Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq.10 g, Prunella vulgaris L. 10 g, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. 5 g) & Control | 34 (18/16) |

50.3 ± 9.0 | multiple antihypertensive drugs (CCB, ACEI/ARB, β-blocker, diuretic et al.) | 12 weeks | SBP, DBP, VEGF |

| Li et al., 2017 | 105 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 53 (36 /19) |

65.9 ± 5.3 | Annao pill (Bovis calculus artifactus, Sus scrofadomestica brisson, Cinnabaris, Borneolum syntheticum, Bubalus bubalis Linnaens, Pteria martensii (Dunker), Scutellaria baicalensis georgi, Coptis chinensis Franch, Gardenia jasminoides ellis, Realgar, Curcuma wenyujin Y.H. Chen et C.Ling, Gypsum fibrosum, haematitum, Hyriopsis cumingii (Lea), Mentha haplocalyx Briq.) & Control | 52 (31/21) |

66.2 ± 5.2 | multiple antihypertensive drugs (CCB, ACEI, aspirin, citicoline) | 8 weeks | SBP, DBP, NO, ET-1 |

| Liu et al., 2018 | 110 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 55 (36 /19) |

54.69 ± 5.81 | Ziyin Huoxue decoction (Cornus officinalis Siebold & Zucc. 15 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 12 g, Ligusticum striatum DC. 12 g, Chinemys reevesii (Gray) 12 g, Ligustrum lucidum W.T.Aiton 12 g, Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge 12 g Lycium barbarum L. 12 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 12 g (Praeparata), Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 10 g , Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 10 g, Phellodendron chinense C.K.Schneid 10 g.) & Control | 55 (32/33) |

53.21 ± 5.43 | amlodipine besylate | 8 weeks | SBP, DBP, NO, ET-1 |

| Sheng and Wang, 2016 | 126 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2005) | 63 (37/26) |

69.78 ± 1.60 | Bushen Huoxue decoction (Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Dioscorea japonica Thunb. 10 g, Cornus officinalis Siebold & Zucc. 10 g, Lycium barbarum L. 10 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 10 g, Achyranthes bidentata Blume 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Carthamus tinctorius L. 10 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides ‘Chuanxiong' 10 g, Ginkgo biloba L. 10 g.) & Control | 63 (35/28) |

70.47 ± 1.58 | multiple antihypertensive drugs (CCB, ACEI) | 4 weeks | SBP, DBP, NO, ET-1, Ang II |

| Teng et al., 2016 | 170 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 85 (50/35) |

69.2 ± 5.9 | Bushen Huoxue decoction (Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 30 g, Lycium barbarum L. 20 g, Cornus officinalis Siebold & Zucc. 10 g, Alisma plantago-aquatica subsp. orientale (Sam.) Sam. 10 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 10g, Paeonia × suffruticosa Andrews 10g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 15 g, Taxillus chinensis (DC.) Danser 20g, Apocynum venetum L. 15 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 10g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Prunus davidiana (Carrière) Franch. 10 g, Carthamus tinctorius L. 6 g, Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan 15 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 20 g) & Control | 85 (48/37) |

69.8 ± 6.1 | multiple antihypertensive drugs (CCB, ACEI) | 12 weeks | 24 h-SBP, 24 h-DBP, ET-1, NO |

| Gao and Li, 2017 | 80 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 40 (19/21) |

68.17 ± 3.28 | Bushen Jieyu decoction (Taxillus chinensis (DC.) Danser 15 g, Ligustrum lucidum W.T.Aiton 15 g, Bupleurum chinense DC. 12 g, Epimedium brevicornu Maxim. 12 g, Gastrodia elata Blume 12 g, Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq. 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 12 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 9 g, Mentha canadensis L. 6 g, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. 6 g) & Control | 40 (22/18) |

68.52 ± 4.26 | amlodipine besylate | 8weeks | SBP, DBP, ET-1, NO |

| Wu et al., 2016 | 60 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 30 (14/16) |

68.16 | Compound Qima capsule & Control | 30 (15/15) |

69.77 | Nifedipine Controlled released Tablets | 4 weeks | SDP, DBP, FMD, vWF |

| Li, 2017 | 110 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention | 55 (30/25) |

56.8 ± 8.9 | Modified Wendan decoction (Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. 10 g, Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 10 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 10 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. 6 g, Bambusa beecheyana Munro 3 g) & Control | 55 (28/27) |

55.5 ± 8.5 | amlodipine | 12 weeks | SBP, DBP, VEGF |

| Lu et al., 2015 | 126 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2005) | 63 (32/31) |

59.73 ± 11.59 | Modified Wendan decoction (Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. 10 g, Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 10 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 6 g, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. 10 g, Bambusa beecheyana Munro 3 g) & Control | 63 (33/30) |

58.16 ± 10.97 | AmlodiieMaleateTalet | 12 weeks | SBP, DBP, VEGF |

| Wang et al., 2016 | 86 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention | 42 (27/15) |

54.19 ± 12.48 | Pinggan Qianyang decoction (Sigesbeckia glabrescens (Makino) Makino 15 g, Prunella vulgaris L. 15 g, Concha haliotidis 15 g, Styphnolobium japonicum (L.) Schott 15 g, Gastrodia elata Blume 15g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 15 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 15 g, Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan 10 g, Taxillus chinensis (DC.) Danser 10 g, Plantago asiatica L. 15 g) & Control | 44 (26/18) |

53.48 ± 12.37 | amlodipine besylate | 6 months | SBP, DBP, hs-CRP, NO, ET-1 |

| Feng et al., 2016 | 86 | WHO/ISH Guidelines for the Treatment of Hypertension (1999) | 43 (30/13) |

62.75 ± 1.42 | Qiwei Tiaoya granules (Gastrodia elata Blume 1.5 g, Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq. 3 g, Concha haliotidis 3.6 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 2.4 g, Arctium lappa L. 1.8 g, Testudinis carapax et plastrum 3 g, Carapax trionycis 3 g), Zhibai Dihuang Pills & Control | 43 (30/13) |

61.37 ± 3.84 | Perindopril Tablets | 8 weeks | SBP, DBP, ET-1, NO |

| Cao et al., 2019 | 120 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 60 (33/27) |

58.68 ± 9.37 | Jianpi Tongluo decoction (Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 15 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 15 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 10 g, Pheretima aspergillum(E.Perrier) 12 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 12 g, Carthamus tinctorius L. 10 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides ‘Chuanxiong' 10 g) & Control | 60 (31/29) |

57.48 ± 8.58 | amlodipine besylate | 4 weeks | 24 h-SBP, 24 h-DBP, ET-1, NO |

| Zeng W. Y. et al., 2017 | 180 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 90 (48/42) |

56.17 ± 6.73 | Quyu Huoxue decoction (Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq. 30 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 15 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 15 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 15 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 15 g, Gastrodia elata Blume 15 g, Alisma plantago-aquatica subsp. orientale (Sam.) Sam. 15 g, Leonurus cardiaca L. 15 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 10 g) & Control | 90 (51/39) |

56.33 ± 6.80 | multiple antihypertensive drugs (CCB, ARB, diuretic) | 3 months | SBP, DBP, FMD, ET-1, vWF |

| Zheng et al., 2016 | 160 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 80 (45/35) |

68.1 ± 7.9 | Songling Xuemaikang capsule (Pinus pinea L., Pueraria lobate (Willd).Ohwi, Pteria martensii (Dunker)), Qiju Dihuang Pill (Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC., Cornus officinalis Sieb.et Zucc., Dioscotea opposita Thunb. Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf, Alisma orientale (Sam.) Juzep., Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bge., Phellodendron chinense Schneid.) & Control | 80 (47/33) |

67.5 ± 7.2 | antihypertensive drugs (CCB, ARB, diuretic) | 12 weeks | SBP, DBP, FMD, NO, ET-1, vWF, |

| Han et al., 2018 | 82 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 41 (23/18) |

69.8 ± 3.15 | Danshen Dripping pills (Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge., Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F.H.Chen,, Borneolum syntheticum) & Control | 41 (25/16) |

69.51 ± 3.14 | Telmisartan | 12 weeks | SBP, DBP, NO, ET-1 |

| Zeng Z. C. et al., 2017 | 60 | Chinese expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in the elderly | 30 (17/13) |

49.80 ± 6.45 | Tianma Gouteng decoction (Gastrodia elata Blume 20 g, Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq. 10 g, Concha haliotidis 15 g, Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis 10 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 10 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 10 g, Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan 20 g, Leonurus cardiaca L. 10 g, Taxillus chinensis (DC.) Danser 15 g, Reynoutria multiflora (Thunb.) Moldenke 10 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 15 g) & Control | 30 (9/21) |

71.97 ± 7.82 | multiple antihypertensive drugs (CCB, ARB) | 8 weeks | SBP, DBP, Ang II, NO, ET-1 |

| Sun, 2019 | 120 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 60 (33/27) |

58.17 ± 9.25 | Tianma Gouteng decoction (Gastrodia elata Blume 10 g, Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq. 15 g, Concha haliotidis 15 g, Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis 30 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 10 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 15 g, Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan 15 g, Leonurus cardiaca L. 15 g, Taxillus chinensis (DC.) Danser 15 g, Reynoutria multiflora (Thunb.) Moldenke 30 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 15 g) | 60 (37/23) |

58.95 ± 8.43 | felodipine | 3 months | 24 h-SBP, 24 h-DBP |

| Weng and Lin, 2015 | 60 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 30 (17/13) |

49.80 ± 6.45 | Tianma Gouteng decoction (Gastrodia elata Blume 9 g, Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq. 9 g, Concha haliotidis 9 g, Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis 18 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 9 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 9 g, Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan 9 g, Leonurus cardiaca L. 12 g, Taxillus chinensis (DC.) Danser, Reynoutria multiflora (Thunb.) Moldenke 9 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 9 g) & Control | 30 (15/15) |

52.30 ± 5.37 | hydrochlorothiazide | 12 weeks | 24 h-SBP, 24 h-DBP, FMD |

| Bian, 2016 | 134 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 67 (43/24) |

56.6 ± 8.3 | Tianma Gouteng decoction (Gastrodia elata Blume 20 g, Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq. 15 g, Concha haliotidis 15 g, Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis 15 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 15 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 15 g, Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan 15 g, Leonurus cardiaca L. 15 g, Taxillus chinensis (DC.) Danser 15 g, Reynoutria multiflora (Thunb.) Moldenke 10 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 10 g) & Control | 67 (43/24) |

58.3 ± 8.7 | levamlodipine besylate | 8 weeks | SBP, DBP, hs-CRP, NO, ET-1 |

| Xu et al., 2010 | 189 | WHO/ISH Guidelines for the Treatment of Hypertension (1999) | 96 (52/44) |

53.0 ± 8.9 | Tianma Huangqin pills (Gastrodia elata Blume, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi) & Control | 93 (40/53) |

51.2 ±7.8 | multiple antihypertensive drugs (CCB, ACEI/ARB, β-blocker, diuretic et al.) | 6 weeks | SBP, DBP, 24 h-SBP, 24 h-DBP, ET, NO |

| Shi et al., 2018 | 130 | Chinese expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in the elderly | 65 (34/31) |

72.8 ± 4.3 | Tianzhi decoction (Gastrodia elata Blume 10 g, Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq. 30 g, Whitmania pigra Whitman 6 g, Pueraria montana var. lobata (Willd.) Maesen & S.M.Almeida ex Sanjappa & Predeep 30 g, Senna obtusifolia (L.) H.S.Irwin & Barneby 20 g, Achyranthes bidentata Blume 20 g, Prunella vulgaris L. 10 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Chrysanthemum × morifolium (Ramat.) Hemsl. 10 g) & Control | 65 (36/29) |

71.6 ± 3.7 | irbesartan | 4 weeks | SBP, DBP, ET, NO |

| Ruan et al., 2017 | 70 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 35 (20/15) |

42.10 ± 4.98 | Tongmai Huazhuo decoction (Carthamus tinctorius L. 20 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 15 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 30 g, Thespesia populnea (L.) Sol. ex Corrêa 30 g, Typha orientalis C.Presl 15 g, Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge 25 g, Raphanus raphanistrum subsp. sativus (L.) Domin 20 g) & Control | 35 (18/17) |

40.98±5.00 | amlodipine besylate | 8 weeks | SBP, DBP, TGFβ-1, VEGF |

| Zhang, 2015 | 80 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2005) | 40 (23/17) |

51.6 ± 7.2 | Xuefu Zhuyu decoction (Prunus davidiana (Carrière) Franch. 12 g, Carthamus tinctorius L. 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 12 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 10 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides ‘Chuanxiong' 5 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 10 g, Achyranthes bidentata Blume 10 g, Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC. 5 g, Bupleurum chinense DC. 3 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 5 g, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. 3 g) & Control | 40 (25/15) |

52.3 ± 8.4 | candesartan cilexeti | 8 weeks | SBP, DSP, NO, ET -1, FMD |

| Luo, 2018 | 116 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2010) | 58 (33/25) |

69.1 ± 8.4 | Yiqi Huoxue Tongluo decoction (Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 50 g, Pheretima aspergillum(E.Perrier) 15 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 15 g, Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan 15 g, Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 10 g, Prunus davidiana (Carrière) Franch. 6 g, Carthamus tinctorius L. 6 g, Cinnamomum cassia (L.) J.Presl 6 g, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. 6 g) & Control | 58 (35/23) |

68.8±8.5 | multiple antihypertensive drugs (CCB, ARB, diuretic) | 4 weeks | SBP, DSP, TGFβ-1, VEGF |

| Zhu et al., 2010 | 90 | Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertention (2005) | 30 (19/11) |

51.32 ± 5.73 | Yishen Pinggan decoction (Eucommia ulmoidesOliv., Taxillus chinensis (DC.) Danser, ramulus Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq.) Miq., Apocynum venetum L., Pueraria montana var. lobata (Willd.) Maesen & S.M.Almeida ex Sanjappa & Predeep lobatae, Cyathula officinalis K.C.Kuan) & Control | 30 (21/9) |

53.21 ± 5.43 | benazepril | 3 months | 24 h-SBP, 24 h-DBP, ET, NO |

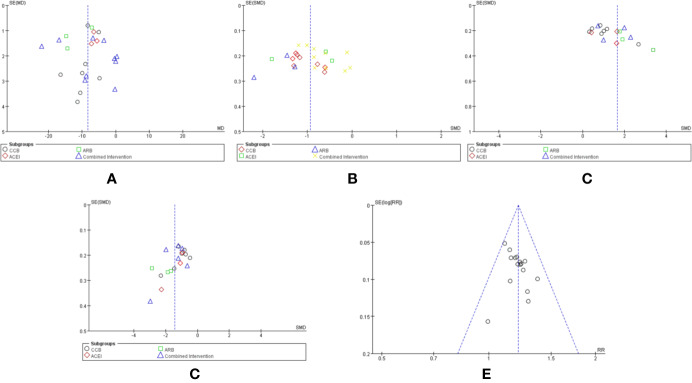

Publication Bias

Funnel plot analysis for the outcomes of SBP (A), DBP (B), NO (C), ET-1 (D), and therapeutic effects (E) was performed to explore the publication bias. The funnel plot was asymmetric, suggesting a mild publication bias in this systematic review (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Funnel plot of the comparison between CHM combined with conventional Western medicine and conventional Western medicine alone for SBP (A), DBP (B), NO (B), ET-1 (D), and therapeutic effects (E).

Discussion

TCM herbal formulas have always been recommended as complementary and alternative treatments for hypertension in China and other countries (Xiong et al., 2018). With the concerns of long-term medication and adverse reactions of antihypertensive drugs, some mild to moderate hypertensive patients who are not willing to take antihypertensive drugs would prefer CHM either used alone or in combination with antihypertensive drugs. In their opinion, TCM was efficacious in improving symptoms, reducing fluctuations in BP, improving vascular endothelial function associated with hypertension, and reducing the amount of conventional Western medicine despite its bitter and slightly sweet taste (Wu et al., 2014). In addition, as CHM has been used for thousands of years, it seems to be relatively safe (Xiong et al., 2015). However, whether TCM is beneficial for hypertension on vascular endothelial function is not well recognized until now. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of the published RCTs to sum up the effects of TCM for hypertension treatment on vascular endothelial function and provide the latest level of evidence for patients, policymakers, and clinicians.

Summary of Main Results

As compared with the conventional Western medicines, the results of this meta-analysis showed marked improvements in BP and vascular endothelial function for hypertensive patients treated with CPAD, although there was some heterogeneity among these studies. NO and ET are essential substances synthesized and secreted mainly by endothelial cells for dilatation and vascular contraction, respectively, and their levels in blood were used to evaluate vascular endothelial injury (Zhong et al., 2011). FMD is a conventional assessment of conduit artery function with great cardiovascular insight (Broxterman et al., 2019). Meta-analysis in this study proves that CPAD could obviously protect vascular endothelial function in hypertensive patients by increasing the serum NO levels, reducing that of ET, and improving FMD. Hypertension is also related to endothelial dysfunction. Hypoxia induced by vascular endothelial injury is one of the most important factors in inducing VEGF expression. VEGF is an important mediator of the Ang II-induced inflammatory reaction of vasculature. It releases VEGF, attracts circulating neutrophils and monocytes, and increases the production of inflammatory mediators, leading to hypertension (Zhao et al., 2004). VEGF and other inflammatory markers are greatly elevated in hypertensive patients, especially in patients with uncontrolled BP, and VEGF levels are directly related to the levels of SBP and CRP (Marek-Trzonkowska et al., 2015). VWF and TGFβ-1 are also vital indicators for the evaluation of vascular endothelial injury (Ryan et al., 2003; Kido et al., 2008). This meta-analysis showed that compared with conventional Western medicines, remarkable improvements were displayed in VEGF, hs-CRP, vWF, and TGFβ-1 for hypertensive patients treated with CPAD. We conducted a subgroup analysis of the above results with more than 10 studies. The antihypertensive drugs were divided into CCB, ACEI, ARB, diuretics, and combination drugs. The results showed that CHM combined with CCB and combined intervention could significantly improve 24 h-SBP, 24 h-DBP, SBP, DBP, NO, ET-1, and FMD. CHM combined with ACEI could remarkably improve SBP, DBP, NO, ET-1, but failed to reduce 24 h-SBP and 24 h-DBP. CHM combined with ARB could greatly improve SBP, DBP, NO, and ET-1, but failed to increase FMD. CHM combined with diuretics could obviously increase FMD but failed to reduce 24 h-SBP and 24 h-DBP. Moreover, the completion rate of all studies was more than 99% without severe adverse events, indicating that CHM might be an effective and safe choice for hypertension by alleviating symptoms and improving the well-being of hypertensive patients.

Strengths and Limitations

In clinical practice, antihypertensive Western medicines have a clear curative effect, but all of them have certain side effects. They cannot be completely eliminated from clinical use, and it is impossible to avoid situations where some patients may not be willing to take Western drugs and may not fully meet the needs of clinical treatment for hypertension. TCM classic herbal formulas with fixed herbs, definite curative effects, and fewer adverse effects for certain diseases have been practiced since ancient times (Xiong et al., 2017). Meanwhile, TCM classic herbal formulas have been recommended as complementary and alternative treatments in China and other countries. Thus, in Asian countries, some hypertensive patients have turned to TCM treatment with fewer adverse effects (Xiong et al., 2013). A previous meta-analysis demonstrated that a TCM adjuvant to antihypertensive drugs might be beneficial for hypertensive patients for lowering BP, improving depression, regulating blood lipids, and inhibiting inflammatory responses (Xiong et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018; Xiong et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2019; Xiong et al., 2019). However, these studies do not focus on vascular endothelial function injury, which is one of the most common reactions of hypertension and plays a vital role in the occurrence and development of hypertension. The combination of CHM and Western medicine for essential hypertension treatment has become a trend in East Asia. At present, there is no definite index for evaluating the function of the vascular endothelium. To comprehensively evaluate the function of the vascular endothelium, we included many blood indicators to ensure that the results are comprehensive. The evaluation of the vascular endothelial function has not been included as one of the important factors affecting the cardiovascular prognosis of patients in the latest hypertension treatment guidelines. Moreover, there are no drugs specifically for vascular endothelial injury. The analysis in this study may provide some evidence for further improvement of the treatment guidelines.

After quantitative synthesis, our review is the first to demonstrate that CPAD can lower BP and improve vascular endothelial function in patients with hypertension, suggesting that TCM as an adjuvant therapy could be used for hypertension treatment by alleviating symptoms and improving the well-being.

However, there are some limitations to our review. We only conducted a search based on Chinese and English studies, and it is possible that articles related to CPAD for hypertension may have been published in other languages. Moreover, in this systematic review, we did not consider differences in the composition and dosage of CPAD and the course of medication, which may have some influence on treatment efficacy. The methodological quality of the included trials was quite low, except that CPAD was difficult to blind. The included studies had other flaws, including poor randomization and allocation concealment. According to the GRADE system, the evidence of CPAD for hypertension treatment was assessed to be of very low, low, or moderate quality. Therefore, evidence supporting CPAD in the treatment of patients with hypertension was inconclusive.

Implications for Research

In this review, CPAD may be effective and safe for the treatment of hypertension, but the methodological quality of the included studies was poor, evidence for efficacy and safety was insufficient, and clinical heterogeneity was large; therefore, great attention should be paid when interpreting current evidence and potential findings. Further research is needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CPAD for treating hypertension. Rigorous RCTs with large sample sizes and high-quality methodologies are required to explore the efficacy of CPAD in clinic and provide evidence-based data for promoting the use of CPAD.

Conclusion

To summarize, our meta-analysis suggests that compared with conventional Western medicine alone, CPAD might be effective in reducing BP levels and improving vascular endothelial function in patients with hypertension. As there are some methodological limitations to the studies included, these findings are required to be interpreted carefully. To further strengthen this evidence, new, well-designed studies with large sample sizes, strict randomization, and detailed descriptions about the detection and reporting processes are warranted.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Author Contributions

LH, MW, and WR: Conceived and designed the experiments. WR, JL, LL, DY, and RY: Performed the experiments. RQ, LL, and JL: Searched the literature. WR, LH, and RY: Data extraction and risk of bias assessments. WR, MW, and LL: Analyzed the data. WR: Wrote the paper. WR, MW, JL, LL, DY, RY, and LH: Read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81573777) and the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (no. 7162172). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer YS declared a shared affiliation, with no collaboration, with several of the authors, WR, DY, MW, RY, and LL, to the handling editor at the time of review.

Abbreviations

CHM, Chinese herbal medicine; ROB, Risk of bias; CVD, Cardiovascular disease; DALYs, Death- and disability-adjusted life-years; BP, Blood pressure; b-blocker, Beta-adrenergic blocking agents; ACEI, Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, Angiotensin II receptor blockers; CCB, Calcium channel blockers; TCM, Traditional Chinese Medicine; CAM, Complementary and alternative medicine; CHM, Chinese herbal medicine; CPAD, CHM plus antihypertensive drugs; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; SBP, Systolic blood pressure; DBP, Diastolic blood pressure; NO, Nitric oxide; FMD, Flow mediated dilation; VEGF, Vascular endothelial growth factor; hs-CRP, Highsensitivity C-reactive protein; Ang II, Angiotensin II; vWF, von Willebrand Factor; TGFb-1, Transforming growth factor b-1; RCTs, Randomized controlled trials; RR, Relative risk; CI, Confidence interval; MD, Mean difference; SMD, Standard mean difference.

References

- Bian W. S. (2016). Impact of Tianmagoutengyin combined with Levamlodipine Besylate on blood pressure, serum inflammatory cytokines levels and vascular endothelial function of patients with essential hypertension. Pract. J. Cardiac Cereb. Pneumal Vasc. Dis. 24 (05), 87–89. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-5971.2016.05.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broxterman R. M., La Salle D. T., Zhao J., Reese V. R., Richardson R. S., Trinity J. D. (2019). Influence of dietary inorganic nitrate on blood pressure and vascular function in hypertension: Prospective Implications for Adjunctive Treatment. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 127 (4). 10.1152/japplphysiol.00371.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S. P., Gu N., Song Y. H., Liu X. Q. (2019). Clinical research of tonifying spleen and dredging collaterals formula in treating hypertension clinical research of tonifying spleen and dredging collaterals formula in treating hypertension. Liaoning J. Traditional Chin. Med. 46 (03), 533–535. 10.13192/j.issn.1000-1719.2019.03.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Wang Y., He Z., Wang D., Yan X., Xie P. (2018). Tianma Gouteng decoction for essential hypertension: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. (Baltimore) 97 (8), e9972. 10.1097/MD.0000000000009972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaboration N.C.D.R.F. (2017). Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19.1 million participants. Lancet 389 (10064), 37–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31919-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. H., Sun Z. Y., Bai W. J., Zhu Z. H. (2016). Observation on the curative effect of qiwei tiangyan granule hezhi bai dihuang pill in treating Yin deficiency and Yang hyperactivity hypertension. J. Guangxi Univ. Chin. Med. 19 (02), 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gao H. F., Li J. (2017). Clinical observation and effect on endothelial function of Bushen Jieyu decoction in old patients with hypertension and depression state. J. Shanxi Coll. Traditional Chin. Med. 18 (04), 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Dong X., Zhong F., Guo W. F., Nie H. X., Liu J. W., et al. (2012). Effect of Yindanxinnaotong soft capsule on vascular endothelium-dependent vasodilatation function and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in elderly patients with hypertension. Mod. J. Integr. Traditional Chin. West. Med. 21 (28), 3084–3086. [Google Scholar]

- Han L., Song S. Y., Wang M. N., Li L., Tang Y., Chen G. H. (2018). Efffects of telmisartan combined with Danshen dripping pills on blood pressure vascular endothelial function in patients of primary grade 2 hypertension. Anhui Med. Pharm. J. 22 (02), 352–355. [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. E., Cooper K. L., Relton C., Thomas K. J. (2012). Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: a systematic review and update. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 66 (10), 924–939. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02945.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J., Altman D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327 (7414), 557–560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Chen Y., Cai H., Chen D., He X., Li Z., et al. (2019). Herbal medicine (Zhengan Xifeng Decoction) for essential hypertension protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. (Baltimore) 98 (6), e14292. 10.1097/MD.0000000000014292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hypertension Alliance (China), Hypertension Branch of China Association for the Promotion of International Exchanges in Healthcare, China Committee for the Revision of Hypertension Prevention and Control, China Healthcare International Exchange Promotion Association, Hypertension Branch Hypertension Branch of Chinese Geriatrics Society (2018). Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Chin. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 24 (01), 24–56. 10.3969/j.issn.1007-5410.2019.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juonala M., Viikari J. S., Ronnemaa T., Helenius H., Taittonen L., Raitakari O. T. (2006). Elevated blood pressure in adolescent boys predicts endothelial dysfunction: the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Hypertension 48 (3), 424–430. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000237666.78217.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kido M., Ando K., Onozato M. L., Tojo A., Yoshikawa M., Ogita T., et al. (2008). Protective effect of dietary potassium against vascular injury in salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension 51 (2), 225–231. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim L. W., Zhu J. (2010). Acupuncture for essential hypertension. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 16 (2), 18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Meng H., Zhang X. L., Zhang W. (2017). Effects of normal therapy assisted with Annao pill on endothelial function, hemorheology and hemodynamics in elderly patients with hypertension with vertigo. Mod. J. Integr. Traditional Chin. West. Med. 26 (23), 2521–2524. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-8849.2017.23.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Y. (2017). Effect of flavoured and warm-dan decoction combined with amlodipine on serum VEGF level in patients with phlegm-dampened hypertension. Asia-Pac. Traditional Med. 13 (12), 135–136. 10.11954/ytctyy.201712057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. C., Zhang H. F., Chang L. L., Liu Y. J., Chen G. J., Cui W. Y. (2018). Effects of amlodipine combined with ziyin huoxue prescription on platelet membrane protein and vascular endothelial function in patients with hypertension and coronary heart disease. Prev. Treat Cardio-Cerebral-Vascular Dis. 18 (05), 399–402. 10.3969/j.issn.1009-816x.2018.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano R., Naghavi M., Foreman K., Lim S., Shibuya K., Aboyans V., et al. (2012). Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380 (9859), 2095–2128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z. S., Zeng J. Q., Yu F., Sun Q. G. (2015). Effects of Modified Wendan Decoction Combined with Amlodipine Tablets on TCM Constitution and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor of Phlegm-damp Hypertension Patients. Chin. J. Inf. Traditional Chin. Med. 27, 32–35. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-5304.2015.07.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S. F. (2018). Clinical Study on Yiqi Huoxue Tongluo Tang Combined with Western Medicine for Senile Primary Hypertension. J. New Chin. Med. 50 (10), 59–61. 10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2018.10.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marek-Trzonkowska N., Kwieczynska A., Reiwer-Gostomska M., Kolinski T., Molisz A., Siebert J. (2015). Arterial Hypertension Is Characterized by Imbalance of Pro-Angiogenic versus Anti-Angiogenic Factors. PloS One 10 (5), e0126190. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., Group P. (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 8 (5), 336–341. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. J., Vos T., Lozano R., Naghavi M., Flaxman A. D., Michaud C., et al. (2012). Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380 (9859), 2197–2223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Q. W., Li M. Q. (2014). Influence of Chinese Medicine of Resolving Phlegm and Dredging Collaterals in Treating Hypertension Patients with Accumulation of Phlegm and Blood Stasis. Chin. J. Inf. Traditional Chin. Med. 21 (06), 18–20. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-5304.2014.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W. D., Fang Z. Y., Jiang W. M., Lu H. T. (2013). Effect of Jiangzhi Kangyanghua mixture on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and vascular Endothelial functions of hypertension patients. China J. Chin. Materia Med. 38 (20), 3583–3586. 10.4268/cjcmm20132034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan L., Jiao X. M., Li J., Wang C. L., Li T. (2017). Effect of Tongmai Huazhuo Decoction in the treatment of hypertension patients with syndrome of intermin-gled phlegm and blood stasis and its influence on transforming growth factor-β1, vascular endothelial growth factor, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1. China Med. Herald 14 (16), 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S. T., Koteliansky V. E., Gotwals P. J., Lindner V. (2003). Transforming growth factor-beta-dependent events in vascular remodeling following arterial injury. J. Vasc. Res. 40 (1), 37–46. 10.1159/000068937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattar N., McCarey D. W., Capell H., McInnes I. B. (2003). Explaining how “high-grade” systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 108 (24), 2957–2963. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099844.31524.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw E., Anderson J. G., Maloney M., Jay S. J., Fagan D. (1995). Factors associated with noncompliance of patients taking antihypertensive medications. Hosp Pharm. 30 201-203 (3), 206–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z. J., Zhang Y., Wang Y. J., Wang X. L. (2013). Study on clinical efficacy and endothelial function protection of Tianma Gouteng Granule in interfering primary hypertension patients with hyperactivity of liver-yang. J. Chin. Physician 15 (6), 744–747. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1008-1372.2013.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng H. E., Wang H. L. (2016). Effects of Kidney-Tonifying and Blood-Activating Formula on the Vascular Endothelial Function of Patients with Senile Hypertension Due to Kidney and Liver Deficiency Complicated with Blood Stasis Syndrome. Henan Traditional Chin. Med. 36 (08), 1407–1409. 10.16367/j.issn.1003-5028.2016.08.0574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Duan K. Q., Shi Y. H., Xi X. Y., Meng F. F., Cheng H. (2018). Curative effect of Tianzhi decoction with irbesartan in treating senile hypertension with Yin-deficiency-Yang-hyperactivity and blood stasis syndrome. Clin. Medication J. 16 (10), 40–44. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-3384.2018.10.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shih H. C., Lee T. H., Chen S. C., Li C. Y., Shibuya T. (2005). Anti-hypertension effects of traditional Chinese medicine ju-ling-tang on renal hypertensive rats. Am. J. Chin Med. 33 (6), 913–921. 10.1142/S0192415X05003545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M. Y. (2019). Effects of Tianma Gouteng Decoction on Blood Pressure Variability and Protective Mechanism of Vascular Endothelium in Patients with Essential Hypertension. J. Changchun Univ. Chin. Med. 35 (02), 261–263. 10.13463/j.cnki.cczyy..02.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Y. H., Xie Y., Shi X. Z. (2016). Effect of Bushen Huoxue Decoction to Blood Pressure Variability and Quality of Life of Patients with Kidney Deficiency and Blood Stasis-type Hypertension. Chin. J. Exp. Traditional Med. Formulae 22 (20), 173–177. 10.13422/j.cnki.syfjx.2016200173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz R. M., Briones A. M. (2011). Reactive oxygen species and vascular biology: implications in human hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 34 (1), 5–14. 10.1038/hr.2010.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Zhang J. D., Feng J. B., Yin H. Q., Liu F. Y., Wang Y. (2007). Effect of traditional Chinese medicine Qin-Dan-Jiang-Ya-Tang on remodeled vascular phenotype and osteopontin in spontaneous hypertensive rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 110 (1), 176–182. 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. T., Liu Y. J., Zhang X. X., Wang Y. H. (2016). Clinical observation of pinggan qianyang prescription in the treatment of early and middle primary hypertension with hyperactivity of liver Yang. Shaanxi J. Traditional Chin. Med. 37 (08), 982–984. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-7369.2016.08.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weng J. L., Lin E. P. (2015). Clinical Study on Tianma Gouteng Decoction in Treatment of Patients With Hypertension and Improving Vascular Compliance and Endothelial Function. China Health Stand. Manage. 6 (24), 124–126. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-9316.2015.24.090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Writing Group M., Mozaffarian D., Benjamin E. J., Go A. S., Arnett D. K., Blaha M. J., et al. (2016). Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 Update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 133 (4), e38–360. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Zhang J., Zhao Y., Chen J., Liu Y. (2014). Chinese herbal medicine bushen qinggan formula for blood pressure variability and endothelial injury in hypertensive patients: a randomized controlled pilot clinical trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014, 804171. 10.1155/2014/804171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. G., Wang H. Q., Jin L. L., Huang P. H., Feng N. N. (2016). Effect of compound qima capsule on factors related to vascular endothelial injury in patients with qi deficiency, phlegm and turbidized hypertension. Liaoning J. Traditional Chin. Med. 43 (01), 86–88. 10.13192/j.issn.1000-1719.2016.01.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X., Yang X., Liu Y., Zhang Y., Wang P., Wang J. (2013). Chinese herbal formulas for treating hypertension in traditional Chinese medicine: perspective of modern science. Hypertens. Res. 36 (7), 570–579. 10.1038/hr.2013.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X., Wang P., Zhang Y., Li X. (2015). Effects of traditional Chinese patent medicine on essential hypertension: a systematic review. Med. (Baltimore) 94 (5), e442. 10.1097/MD.0000000000000442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X., Che C. T., Borrelli F., Moudgil K. D., Caminiti G. (2017). Evidence-Based TAM Classic Herbal Formula: From Myth to Science. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017, 9493076. 10.1155/2017/9493076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X. J., Yang X. C., Liu W., Duan L., Wang P. Q., You H., et al. (2018). Therapeutic efficacy and safety of Traditional Chinese Medicine classic herbal formula Longdanxiegan decoction for hypertension: A systematic review and meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 466. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X., Wang P., Duan L., Liu W., Chu F., Li S., et al. (2019). Efficacy and safety of Chinese herbal medicine Xiao Yao San in hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine 61, 152849. 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.152849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Tang K. Q., Hu H. L., Wang G. L, Jin Z. A. (2010). Treatment of 96 cases of hyperactivity hypertension with gastrodia huangqin pill. Traditional Chin. Med. Res. 23 (09), 30–32. 10.3969/j.issn.1001-6910.2010.09.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin C., Seo B., Park H. J., Cho M., Jung W., Choue R., et al. (2007). Acupuncture, a promising adjunctive therapy for essential hypertension: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Neurol. Res. 29 Suppl 1, S98–103. 10.1179/016164107X172220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W. Y., Gu S. H., Yuan Y., Ji X. B., Wang Y. C., Li Y. (2017). Effect of removing blood stasis and activating blood circulation on refractory hypertension and its effect on endothelin-1 and p-selectin. Mod. J. Integr. Traditional Chin. West. Med. 26 (22), 2437–2439. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-8849.2017.22.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z. C., Lin F. X., Wu Z. J., Song Y. Z., Wu W. (2017). Effect of gastrodia elata decoction on neuroendocrine system and vascular endothelial function in elderly patients with hypertension. Traditional Chin. Med. J. 16 (06), 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. H. (2015). Forty Cases of Primary Hypertension Treated with Blood Stasis Expelling Decoction Combined with. Henan Traditional Chin. Med. 35 (06), 1412–1414. 10.16367/j.issn.1003-5028.2015.06.0592 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Ishibashi M., Hiasa K., Tan C., Takeshita A., Egashira K. (2004). Essential role of vascular endothelial growth factor in angiotensin II-induced vascular inflammation and remodeling. Hypertension 44 (3), 264–270. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000138688.78906.6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Lin Z., Zheng P., Ye M. F. (2016). Effects of Songling Xuemaikang capsule combined with Qiju Dihuang pill on vascular endothelial function in Patients with Elderly Hypertension with Deficiency of Liver and Kidney and Internal Static Blood Obstruction. Chin. J. Exp. Traditional Med. Formulae 22 (18), 164–168. 10.13422/j.cnki.syfjx.2016180164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong G. W., Chen M. J., Luo Y. H., Xiang L. L., Xie Q. Y., Li Y. H., et al. (2011). Effect of Chinese herbal medicine for calming Gan and suppressing hyperactive yang on arterial elasticity function and circadian rhythm of blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension. Chin J. Integr. Med. 17 (6), 414–420. 10.1007/s11655-011-0761-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X. Y., Liang X. D., Hu Z. R., Chang X. T., Liu L. M. (2010). Effects of Yishen Pinggan Decoction for ambulatory blood pressure, renal function and vascular endothelial function of hypertensive patients with early renal damage. Chin. Traditional Patent Med. 32 (04), 544–547. 10.3969/j.issn.1001-1528.2010.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M., Zang Y. F., Ma C. H. (2013). Sixty-two Cases of Essential Hypertension with Yin Deficiency and Yang Excess Treated by Supplementing Qingnao Jiangya Tablets. Chin. J. Exp. Traditional Med. Formulae 19 (04), 292–294. 10.13422/j.cnki.syfjx.2013.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.