Abstract

The purpose of this study was to clarify the roles of ERM proteins (ezrin/radixin/moesin) in the regulation of membrane localization and transport activity of transporters at the human blood–brain barrier (BBB). Ezrin or moesin knockdown in a human in vitro BBB model cell line (hCMEC/D3) reduced both BCRP and GLUT1 protein expression levels on the plasma membrane. Radixin knockdown reduced not only BCRP and GLUT1, but also P-gp membrane expression. These results indicate that P-gp, BCRP and GLUT1 proteins are maintained on the plasma membrane via different ERM proteins. Furthermore, moesin knockdown caused the largest decrease of P-gp and BCRP efflux activity among the ERM proteins, whereas GLUT1 influx activity was similarly reduced by knockdown of each ERM protein. To investigate how moesin knockdown reduced P-gp efflux activity without loss of P-gp from the plasma membrane, we examined the role of PKCβI. PKCβI increased P-gp phosphorylation and reduced P-gp efflux activity. Radixin and moesin proteins were detected in isolated human brain capillaries, and their protein abundances were within a 3-fold range, compared with those in hCMEC/D3 cell line. These findings may mean that ezrin, radixin and moesin maintain the functions of different transporters in different ways at the human BBB.

Keywords: Blood–brain barrier, ERM proteins, P-glycoprotein, breast cancer resistance protein, glucose transporter 1

Introduction

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) strictly regulates the transfer of materials via multiple transporters in brain capillary endothelial cells. Changes in transporter functions due to drug exposure or central nervous system (CNS) diseases are associated with the development of multidrug resistance and the exacerbation of CNS diseases.1 Thus, an understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying changes in transporter functions at the BBB, as well as the development of tools to modulate those functions, should be helpful for the treatment of CNS diseases.

The ERM protein family consists of three closely related proteins, ezrin (EZN), radixin (RDX) and moesin (MSN). ERM proteins are required for the maintenance of plasma membrane localization by crosslinking actin filaments with plasma membrane proteins.2 They are also involved in the regulation of transporter function in various organs. For example, RDX-knockout mice showed conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and liver injury, caused by the loss of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2), a bilirubin-secreting transporter, from the bile canalicular membrane.3 Although ERM proteins are pathologically important in the regulation of transporters, their roles in maintaining the transport system at the BBB have not yet been fully clarified.

Kobori et al.4 reported that repeated treatment of rats with morphine increased P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and MSN protein expression levels at the plasma membrane of brain capillary endothelial cells, which facilitated P-gp-mediated morphine efflux from the brain. Furthermore, they found that MSN was co-immunoprecipitated with P-gp in isolated brain capillaries from untreated rats.4 Based on these results, Kobori et al. hypothesized that the decreased morphine concentration in the brain after repeated dosing was caused by an increase of P-gp function via the upregulation of MSN at the BBB. However, the expression levels of various proteins might be affected by morphine exposure, and independent proteins can be non-specifically co-immunoprecipitated. Therefore, it is still unclear whether or not MSN is involved in the upregulation of P-gp efflux activity. RDX-knockout mice showed decreased P-gp protein expression in the small-intestinal membrane, together with increased absorption of orally administered rhodamine 123, a substrate of P-gp.5 These results indicate that RDX is involved in the maintenance of P-gp efflux function at the small intestine. In contrast, the elimination of rhodamine 123 from kidney, which is the main organ of rhodamine 123 excretion, was not altered in RDX-knockout mice.5 This suggests that RDX does not regulate P-gp function in the kidney. Moreover, in an osteosarcoma cell line, linkage between EZR and P-gp is essential to establish P-gp-mediated multidrug resistance.6 Overall, it appears that the molecular mechanisms through which ERM proteins regulate transporter function may vary depending on the organs or cells. Thus, it is possible that ERM proteins have different roles in the BBB from those in other organs and cells.

We have previously established an LC-MS/MS-based simultaneous protein quantification method for multiple transporters7 and have succeeded in simultaneously quantifying the protein expression amounts of many transporters in the plasma membrane fraction of a human brain capillary endothelial model cell line (hCMEC/D3).8 Therefore, the application of this quantification method to the plasma membrane fraction of brain capillary endothelial cells in which EZR, RDX or MSN has been specifically knocked down should enable us to clarify which ERM protein regulates the plasma membrane localization of which transporter at the BBB.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to clarify which ERM proteins are involved in the maintenance of membrane localization and transport activity of which transporters in hCMEC/D3 cells, in order to help understand the differences in the roles of EZR, RDX and MSN in the maintenance of various transport systems at the human BBB.

Materials and methods

Reagents and subjects

[3H]Vinblastine sulfate was purchased from American Radioisotope Labeled Chemicals Inc. (MO, USA). Dantrolene sodium salt was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). [3H]3-O-Methyl-D-glucose was purchased from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA, USA). PSC833 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). Recombinant PKCβI protein was purchased from SignalChem (Richmond, Canada). Frozen brain cortex of a Japanese subject (77-year-old male, who had died of Guillain–Barre syndrome; post-mortem interval 2 h) was kindly provided by Dr. Takashi Suzuki of Tohoku University Hospital. A part of this same brain had been used in our previous studies.9,10 This study was done with written informed consent from the donor (or his next of kin). All experiments were approved by the Ethics Committees of Tohoku University School of Medicine and the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tohoku University and were conducted and reported in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (and as revised in 1983). Peptide probes were synthesized by Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) or Scrum Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) (>95% purity). Other reagents were commercial products of analytical grade.

siRNA transfection of hCMEC/D3 cells

A human brain capillary endothelial model cell line (hCMEC/D3)11 was kindly provided by Dr. Pierre-Olivier Couraud (Institut Cochin, Paris, France). hCMEC/D3 cells were seeded on 10 cm dishes coated with collagen type I (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and cultured in EBM-2 medium (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum “Gold” (PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria), 10 mM HEPES (PAA Laboratories), 1 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; Sigma), 1.4 µM hydrocortisone (Sigma), 5 µg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma), 1% chemically defined lipid concentrate (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen) in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37℃. The experiments using hCMEC/D3 cells were all performed with cells at passage 33, except for the experiments in Supplementary Figure 2, for which the cells were used at passage 34 or 35. siRNA transfection of hCMEC/D3 cells was performed as described previously.12 EZR siRNA (Stealth RNAi™ HSS111283, HSS111284 and HSS111285), RDX siRNA (Stealth RNAi™ HSS109150, HSS109151 and HSS109152) and MSN siRNA (Stealth RNAi™ HSS106735, HSS106736 and HSS106737) were purchased from Invitrogen; these mixtures of three kinds of siRNAs were used for transfection in order to ensure effective suppression of the expression of ERM proteins. Stealth RNAi™ siRNA Negative Control Med GC Duplex (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used as a negative control. siRNAs were transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). The siRNA treatment of hCMEC/D3 cells was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. hCMEC/D3 cells were seeded on collagen-coated 24-well plates (for uptake assay) or 10 cm dishes (for LC-MS/MS analysis) at a density of 2 × 104 cells/cm2. The cells were cultured in the medium without antibiotics for 12 to 18 h, and then treated with a mixture of three kinds of siRNAs at 50 nM (16.7 nM of each of the three siRNAs) against EZR, RDX, or MSN, or 50 nM negative control siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX and Opti-MEM® I Reduced Serum Medium (Invitrogen). The cells were cultured for 72 h, and used for experiments.

Isolation of the brain capillary fraction from human cerebrum

Human brain capillary fraction was prepared as described by Ito et al.13 For details, see Supplementary Method 1.

Preparation of whole-cell lysate and plasma membrane fraction of hCMEC/D3 cells

The whole-cell lysate and plasma membrane fraction of hCMEC/D3 cells were obtained as described by Hoshi et al.12 For details, see Supplementary Method 2.

Quantitative targeted absolute proteomics of transporters, ERM proteins and membrane proteins in hCMEC/D3 cells and human brain capillaries

The absolute protein expression amounts of transporters, ERM proteins and membrane proteins in hCMEC/D3 cells and human brain capillaries were determined using our established quantitative targeted absolute proteomics (QTAP) technique.7 For details, see Supplementary Methods 3 and 4. The probe peptides for the protein quantification are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Uptake assay to determine P-gp, BCRP or MRP1 efflux activity

Uptake assay was performed as described by Hoshi et al.12 with minor modifications.12 hCMEC/D3 cells were seeded onto collagen type I-coated 24-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/cm2. After 72 h post-siRNA transfection, uptake assay was conducted. The cell surface was washed twice with 500 µL of extracellular fluid (ECF) buffer (122 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 3 mM KCl, 0.4 mM K2HPO4, 10 mM D-glucose, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 300 ± 10 mOsm) and pre-incubated with 200 µL serum-free culture medium (EBM-2; Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) for 30 min at 37℃. To initiate uptake, the pre-incubation medium was removed and 200 µL serum-free culture medium containing transporter substrate, 50 nM [3H]vinblastine for P-gp and MRP1 or 2 µM dantrolene for BCRP, was added. After incubation for 60 min at 37℃, the cell surface was quickly washed four times with 500 µL of ice-cold ECF buffer. When cells were treated with inhibitor, 10 µM PSC833 for P-gp, 2 µM Ko143 for BCRP or 50 µM MK571 for MRP1, we used serum-free culture medium that contained these compounds during both the pre-incubation and uptake procedures. Stock solutions were prepared as follows: dantrolene, PSC833, Ko143 and MK571 were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, and vinblastine was dissolved in ethanol. During the uptake assay, the final concentration of organic solvent was less than 0.1%. Vehicle controls included the same concentration of the corresponding organic solvent. NaOH solution (5 mol/L, 200 µL) was added to the wells and the plates were incubated at room temperature overnight to lyse the cells, and then HCl solution (5 mol/L, 200 µL) was added for neutralization. In the case of dantrolene measurement, NaOH solution containing furosemide was used as an internal standard. The radioactivity of [3H]vinblastine in each well was measured by liquid scintillation counting. For the measurement of dantrolene concentration, the neutralized solution was centrifuged at 4℃ and 17,360 g for 5 min, and the supernatant was subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. The LC-MS/MS settings are described in Supplementary Method 5. Total protein amount in each well was measured by the Lowry method with DC protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Cell-to-medium ratio (µL/mg protein) was calculated from the concentration of vinblastine or dantrolene in the cells (mol/mg protein) divided by that in the incubation medium (mol/µL). Efflux activity of P-gp, BCRP or MRP1 was estimated according to Hoshi et al.12

Uptake assay to determine GLUT1 influx activity

hCMEC/D3 cells were prepared as described above. The cells were washed twice with 500 µL of glucose-free ECF buffer and pre-incubated with 200 µL glucose-free ECF buffer for 30 min at 37℃. The pre-incubation medium was removed and 200 µL glucose-free ECF buffer containing 0.11 nM [3H]3-O-methyl-D-glucose (3-OMG) was added to initiate uptake. After incubation for a predetermined time, 10, 20 or 30 s at 37℃, the cells were quickly washed four times with 500 µL of ice-cold glucose-free ECF buffer. The radioactivity in each well was measured as described above.

Quantification of P-gp phosphorylation in P-gp-transfected LLC-PK1 cells

P-gp-transfected LLC-PK1 cells were cultured in SILAC medium (Thermo) containing stable isotope-labeled or unlabeled amino acids as described in Supplementary Method 6. The sample preparation procedure is described in Supplementary Method 7 and Supplementary Figure 1. LC-MS/MS settings and data calculation procedures are given in Supplementary Method 8.

Membrane vesicle uptake

Inside-out membrane vesicle uptake assay was performed to determine P-gp efflux transport activity, as described in Uchida et al.14 with minor modifications. For details, see Supplementary Method 9.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined as described by Hoshi et al.12 All statistical analyses were performed under the null hypothesis, assuming that the means of the compared groups were equal. Comparison between two groups was performed by use of an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (equal variance) or Welch's test (unequal variance) according to the result of the F test. For more than two groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's test was performed to determine the statistical significance of differences between datasets. If the p-value was less than 0.05, the difference was considered as statistically significant and the null hypothesis was rejected. No formal power calculation was performed to estimate the required sample size, as a sample size of 3–4 is used in uptake assay and QTAP analysis of hCMEC/D3 cells and isolated human brain capillaries, which successfully differentiated the changes of transporter activity and protein expression amount.9,12 Indeed, when uptake assays were conducted at three different cell passages using a sample size of 3–4 in each case (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 2), changes of transport activity were consistently differentiated, indicating that the assay is robust, and the outcome is not affected by the use of cells at different passages. These results further indicate that the sample number that we employed in our uptake assay can reliably distinguish changes of transport activity. No randomization or blinding was performed in this study.

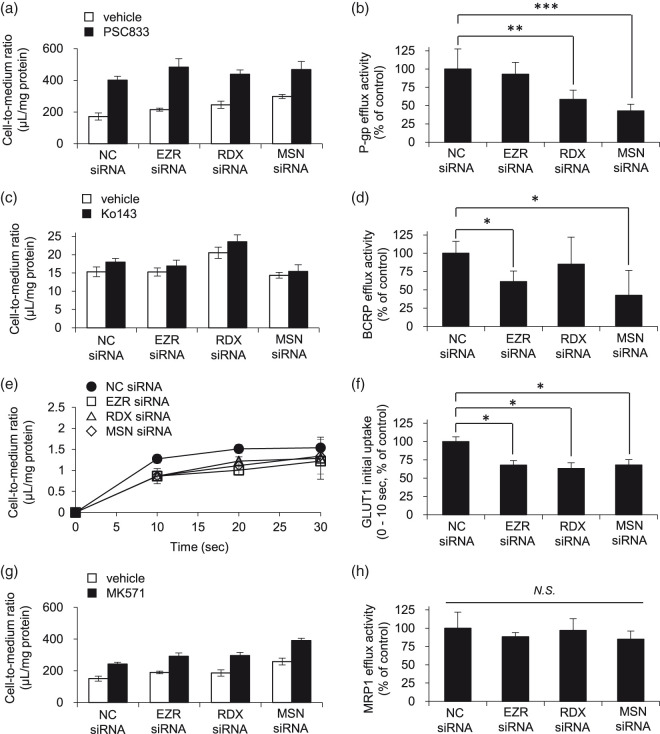

Figure 1.

Effect of ERM protein knockdown on the transport activities of P-gp, BCRP, GLUT1 and MRP1. (a, b) The cellular uptake of P-gp substrate vinblastine was expressed as the cell-to-medium ratio, as described in Materials and methods. Each column represents the mean ± SD of four individual wells. Based on the data in Figure 1(a), P-gp efflux activity was calculated from the cell-to-medium ratio in the absence and presence of PSC833 according to Materials and methods. (c, d) BCRP efflux activity was estimated from the cell-to-medium ratio of BCRP substrate dantrolene in the absence and presence of BCRP inhibitor Ko143 as described above. Each column represents the mean ± SD of three individual wells. (e, f) GLUT1 substrate 3-OMG was incubated with hCMEC/D3 cells in the glucose-free ECF buffer for a predetermined time (10, 20 or 30 s). The concentration of 3-OMG at the time zero was assumed to be zero. Each value represents mean ± SD of three individual wells. Initial influx rate was calculated from the slope of the cell-to-medium ratio of 3-OMG during 0 to 10 s. (g, h) MRP1 efflux activity was estimated from the cell-to-medium ratio of MRP1 substrate vinblastine in the absence and presence of MRP1 inhibitor MK571 as described above. Each column represents the mean ± SD of four individual wells. Dunnett’s test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences between transport activity in negative control siRNA-treated and EZR, RDX or MSN siRNA-treated conditions. NC siRNA: negative control siRNA; N.S.: not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

Results

Effect of ERM protein knockdown on the protein expression amounts of BBB transporters in hCMEC/D3 cells

ERM proteins function as cross-linkers between membrane proteins and the actin cytoskeleton, serving to maintain the proper localization of membrane proteins. Decrease of ERM protein expression causes loss of ERM protein binding partners from the plasma membrane.2 So, we first examined which transporter localizations to the plasma membrane were maintained by ERM proteins in a human BBB model cell line, hCMEC/D3.11 To assess the precise roles of each of EZR, RDX and MSN, we transfected hCMEC/D3 cells with siRNA against EZR, RDX or MSN and quantified the protein expression amounts of transporters in the plasma membrane fraction. As targets, we selected P-gp, breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1), glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1), and 4F2 heavy chain (4F2hc), which were previously detected in hCMEC/D3 cells by our LC-MS/MS quantification method.8 EZR, RDX or MSN siRNA transfection significantly reduced the protein expression amounts of EZR, RDX or MSN in the plasma membrane fraction by 46.6%, 50.0% or 50.5%, respectively (Table 1). As an off-target effect, the protein expression amount of MSN was reduced by 11.4% in EZR siRNA-transfected cells. No compensation effect was observed after any single siRNA transfection, since the expression amounts of ERM proteins in the plasma membrane fraction did not significantly increase. The substantial knockdown of the ERM proteins suggests that these siRNA-transfected cells are suitable models to examine the roles of the ERM proteins. In the case of whole-cell lysate, the protein expression amounts of EZR, RDX and MSN were significantly reduced by 38.4%, 74,7% and 43.3% in the corresponding siRNA-transfected cells. As an off-target effect, the protein expression amount of EZR was increased by 25.1% in MSN siRNA-transfected cells.

Table 1.

Effect of ERM knockdown on the protein expression amounts of membrane proteins in hCMEC/D3 cells.

| Protein expression amounts (fmol/µg protein) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC siRNA | EZR siRNA | RDX siRNA | MSN siRNA | |

| EZR | ||||

| PM | 9.79 ± 1.00 | 5.23 ± 0.32** | 8.35 ± 0.16 | 11.0 ± 0.6 |

| WC | 4.58 ± 0.24 | 2.82 ± 0.20*** | 4.46 ± 0.58 | 5.73 ± 0.56* |

| RDX | ||||

| PM | 4.22 ± 0.44 | 4.82 ± 0.42 | 2.11 ± 0.28*** | 4.49 ± 0.52 |

| WC | 1.83 ± 0.12 | 2.06 ± 0.42 | 0.463 ± 0.160*** | 2.21 ± 0.50 |

| MSN | ||||

| PM | 29.7 ± 1.2 | 26.3 ± 0.6* | 31.3 ± 1.2 | 14.7 ± 0.4*** |

| WC | 11.0 ± 0.6 | 10.5 ± 1.0 | 10.4 ± 0.4 | 6.24 ± 0.84*** |

| Proteins significantly decreased in PM by ERM siRNA | ||||

| P-gp | ||||

| PM | 7.02 ± 0.32 | 6.99 ± 0.17 | 5.66 ± 0.33* | 6.27 ± 0.12 |

| WC | 2.38 ± 0.22 | 2.51 ± 0.16 | 2.22 ± 0.16 | 2.17 ± 0.34 |

| BCRP | ||||

| PM | 2.41 ± 0.18 | 1.58 ± 0.02** | 1.42 ± 0.08*** | 1.67 ± 0.06*** |

| WC | 0.827 ± 0.094 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 0.873 ± 0.052 | 1.05 ± 0.12 |

| GLUT1 | ||||

| PM | 23.0 ± 1.4 | 17.8 ± 1.2** | 15.7 ± 1.2*** | 17.2 ± 1.0* |

| WC | 5.39 ± 0.36 | 5.23 ± 0.33 | 5.98 ± 0.52 | 6.17 ± 0.62 |

| Proteins NOT decreased in PM by ERM siRNA | ||||

| MRP1 | ||||

| PM | 2.13 ± 0.40 | 2.46 ± 0.54 | 1.97 ± 0.34 | 1.98 ± 0.42 |

| WC | 0.881 ± 0.292 | 1.07 ± 0.32 | 0.734 ± 0.352 | 0.930 ± 0.164 |

| ENT1 | ||||

| PM | 3.72 ± 0.40 | 3.18 ± 0.08 | 4.09 ± 0.32 | 5.58 ± 0.24*** |

| WC | 2.08 ± 0.14 | 2.18 ± 0.10 | 1.86 ± 0.08 | 2.72 ± 0.24 |

| 4F2hc | ||||

| PM | 4.45 ± 0.34 | 5.59 ± 0.60 | 5.61 ± 0.66 | 7.82 ± 0.94*** |

| WC | 2.68 ± 0.30 | 2.63 ± 0.08 | 1.78 ± 0.22* | 2.40 ± 0.22 |

| Caveolin-1 | ||||

| PM | 68.1 ± 2.6 | 65.2 ± 2.0 | 60.8 ± 3.6 | 59.6 ± 5.2 |

| WC | 26.5 ± 2.2 | 30.7 ± 1.0 | 27.2 ± 1.2 | 26.5 ± 2.4 |

| Na+/K+ATPase | ||||

| PM | 42.0 ± 3.4 | 40.7 ± 1.4 | 42.4 ± 2.4 | 42.1 ± 2.0 |

| WC | 13.5 ± 1.4 | 13.7 ± 1.2 | 12.9 ± 0.8 | 12.7 ± 0.8 |

Note: hCMEC/D3 cells were transfected with negative control, EZR, RDX or MSN siRNA and cultured for 72 h post transfection. Plasma membrane fraction and whole-cell lysate of hCMEC/D3 cells were digested with lysyl endopeptidase and trypsin. The digests were injected into the LC-MS/MS together with internal standard peptides. Each value represents the mean ± SD of 3-4 product ions in a single PRM analysis. Dunnett’s test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences between the protein expression amounts in negative control siRNA and EZR, RDX or MSN siRNA-transfected hCMEC/D3 cells.

p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

NC siRNA: negative control siRNA; PM: plasma membrane; WC: whole-cell lysate.

Next, we examined the effects of EZR, RDX or MSN knockdown on the protein expression amounts of transporters in the plasma membrane fraction of hCMEC/D3 cells (Table 1). EZR or MSN knockdown significantly decreased BCRP and GLUT1, while RDX knockdown significantly decreased P-gp, BCRP and GLUT1 in the plasma membrane fraction. In contrast, the protein expression amounts of P-gp, BCRP and GLUT1 in whole-cell lysate were unchanged. These results indicate that localization of P-gp, BCRP and GLUT1 to the plasma membrane requires ERM proteins.

No significant decreases in the expression amounts of other proteins at the plasma membrane were observed in EZR, RDX or MSN siRNA-transfected cells. The fact that caveolin-1 expression in the plasma membrane was unchanged indicates that caveolae-mediated endocytosis is not affected by ERM knockdown.

Effect of ERM protein knockdown on the transport activities of P-gp, BCRP, GLUT1 and MRP1 in hCMEC/D3 cells

Next, we examined whether transport activity is suppressed by the decrease of transporter expression at the plasma membrane in ERM protein knockdown-hCMEC/D3 cells, focusing on P-gp, BCRP and GLUT1. MRP1 efflux activity was also measured as a negative control, because MRP1 showed no change of protein expression amount in ERM-knockdown hCMEC/D3 cells. The efflux activities of P-gp, BCRP and MRP1 were determined from the effect of inhibitors (PSC833 for P-gp, Ko143 for BCRP, MK571 for MRP1) on substrate efflux transport (vinblastine for P-gp and MRP1, dantrolene for BCRP). The influx activity of GLUT1 was estimated from the initial uptake rate of 3-OMG, a GLUT1 substrate. The transport activities were calculated from the values of cell-to-medium ratio as described in Materials and methods. We found that P-gp efflux activity was significantly decreased in RDX- or MSN-knockdown cells (Figure 1(a) and (b)). BCRP efflux activity was suppressed by knockdown of EZR or MSN (Figure 1(c) and (d)). Also, GLUT1 initial uptake rate was decreased in EZR-, RDX- or MSN-knockdown cells (Figure 1(e) and (f)). In the case of MRP1, there was no change of MRP1 efflux activity in any of the ERM-knockdown cells (Figure 1(f) and (g)). In order to assess the possible effect of passage difference of the cells, P-gp efflux activities were compared among cells at three different passage numbers. The extent of decrease of P-gp efflux activity due to ERM knockdown was similar in all cases (Figure 1(b), Supplementary Figure 2(b) and (d)).

It has been reported that transport activity is not necessarily correlated with protein expression amount in the plasma membrane under pathological condition and drug exposure, especially under pathological conditions and upon exposure to drugs.15–17 Thus, ERM proteins may not only alter the transporter membrane localization, but also regulate the transport function at the cell membrane. To investigate whether the decrease of transport function was caused by the loss of transporter expression at the plasma membrane, alteration of the transport function at the cell membrane, or both, we compared the extents of decrease of transport activity and protein expression amount at the plasma membrane in ERM protein knockdown-hCMEC/D3 cells (Table 2). There was no significant difference between the % reduction of P-gp expression amount and efflux activity in EZR- or RDX-knockdown cells, whereas the % reduction of P-gp efflux activity was significantly higher than that of P-gp expression amount in MSN-knockdown cells. Since P-gp efflux activity and its membrane localization were equally decreased by RDX knockdown, these results suggested that RDX supports P-gp efflux activity by maintaining the plasma membrane localization of P-gp at the BBB. It was also suggested that MSN knockdown decreases P-gp efflux activity without changing the P-gp protein expression level at the plasma membrane. As for BCRP, no significant difference of % reduction between BCRP expression amount and efflux activity was observed in EZR- or MSN-knockdown cells. In contrast, the % reduction of BCRP expression amount in the plasma membrane was significantly higher than that of BCRP efflux activity in RDX-knockdown cells. These findings indicate that EZR and MSN are involved in the maintenance of BCRP function at the plasma membrane, whereas RDX knockdown decreases the membrane localization of BCRP, but not its function. As for GLUT1, there was no statistically significant difference of % reduction between GLUT1 expression amount in the plasma membrane and influx activity in any of the ERM-knockdown cells. This result suggests that all the ERM proteins contribute to maintaining GLUT1 function in the plasma membrane at the BBB.

Table 2.

Comparison of the % reductions of transport activity and protein expression amount due to ERM knockdown.

| % reduction of protein expression amount in PM by ERM siRNA | % reduction of transport activity by ERM siRNA | |

|---|---|---|

| P-gp | ||

| EZR siRNA | 0.503 ± 2.434 | 8.67 ± 12.74 |

| RDX siRNA | 21.4 ± 8.0 | 33.0 ± 5.7 |

| MSN siRNA | 10.8 ± 1.7 | 58.1 ± 8.8*** |

| BCRP | ||

| EZR siRNA | 34.3 ± 0.6 | 50.4 ± 15.1 |

| RDX siRNA | 41.1 ± 3.0 | 3.13 ± 13.48* |

| MSN siRNA | 30.7 ± 2.8 | 62.3 ± 14.7 |

| GLUT1 | ||

| EZR siRNA | 22.6 ± 5.6 | 32.2 ± 7.3 |

| RDX siRNA | 32.0 ± 5.0 | 35.9 ± 13.0 |

| MSN siRNA | 25.4 ± 4.6 | 31.9 ± 9.7 |

Note: Data of protein expression amount in plasma membrane fraction and transport activity were taken from Table 1 and Figure 1, respectively. The % reduction was calculated as follows; for protein expression amount in plasma membrane fraction, 100 × [(protein expression amount in negative control siRNA-transfected cells) – (protein expression amount in ERM siRNA-transfected cells)]/[protein expression amount in negative control siRNA-transfected cells]; for transport activity, 100 × [(transport activity in negative control siRNA-transfected cells) – (transport activity in ERM siRNA-transfected cells)]/[transport activity in negative control siRNA-transfected cells]. Each value represents the mean ± SD. Student’s t-test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences between % reductions of protein expression amount and transport activity. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005.

PM: plasma membrane fraction.

Involvement of P-gp phosphorylation in the reduction of P-gp efflux activity

There was a significant discrepancy between the changes in P-gp efflux activity and plasma membrane expression in MSN-knockdown hCMEC/D3 cells. So, we next investigated the regulatory mechanism of P-gp function via MSN at the BBB. Previous studies have revealed that the activation of protein kinase C βI (PKCβI) reduced P-gp efflux activity without the loss of P-gp protein expression at the plasma membrane in rat BBB.15,16 Moreover, MSN knockdown increased the phosphorylation level of myosin light chain (MLC), which is a substrate of PKCβI, in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells.18,19 These findings suggest that PKCβI-mediated P-gp phosphorylation causes a decrease of P-gp efflux activity in MSN-knockdown hCMEC/D3 cells. However, there has been no report indicating the involvement of P-gp phosphorylation in the reduction of P-gp efflux activity based on direct measurement of the P-gp phosphorylation level.

Thus, to clarify whether or not PKCβI-mediated P-gp phosphorylation reduces P-gp efflux activity, we first examined the effect of PKCβI on the phosphorylation level of P-gp. Among the phosphorylation sites in P-gp, the linker region (approximately Glu633 to Tyr709) has a crucial role in ATP hydrolysis and substrate recognition.20 Thus, a change of phosphorylation in the linker region might affect the P-gp efflux activity. Based on in silico peptide selection criteria,7 we selected two peptides (DSGSSLIR positioned at 653-660 and SICGPHDQDR positioned at 667-676), including four possible phosphorylation sites, for LC-MS/MS measurement. Since the protein expression amount of P-gp in hCMEC/D3 cells was insufficient to permit detection of phosphorylated P-gp, we used P-gp-transfected LLC-PK1 cells21 for this purpose. We found that the phosphorylation levels of the two peptides were significantly increased after treatment of the plasma membrane fraction isolated from P-gp-transfected LLC-PK1 cells with recombinant PKCβI protein (Figure 2(a)). This result demonstrates that PKCβI phosphorylates amino acid residues in the linker region of P-gp.

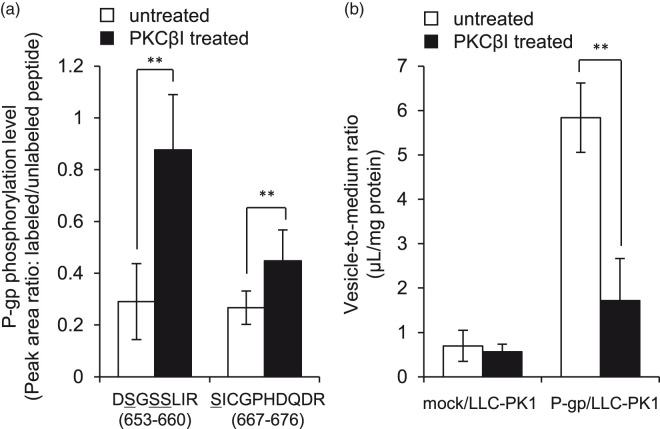

Figure 2.

PKCβI-mediated phosphorylation of P-gp reduced the efflux transport activity. (a) The membrane proteins isolated from P-gp-transfected LLC-PK1 cells were mixed with kinase assay buffer containing PKCβI for 15 min at 37℃, and then enzymatically digested under denaturing conditions. The peak area ratio was calculated from the peak areas of unlabeled and labeled peptides. Each column represents the mean ± SD of peak area ratio from three (for DSGSSLIR) or nine (for SICGPHDQDR) product ions in duplicate analysis. Possible phosphorylation sites are indicated with underlines. (b) Membrane vesicles isolated from mock or P-gp-transfected LLC-PK1 cells were pre-incubated with kinase assay buffer containing recombinant PKCβI at 37℃ for 15 min. The uptake assay was performed by the incubation with transport assay mixture containing NMQ at 37℃ for 10 min. Each column represents the mean ± SD from four independent experiments (vehicle; n = 14, PKCβI; n = 8). Student’s t-test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences between vehicle and PKCβI-treated conditions. mock/LLC-PK1: mock transfected LLC-PK1; P-gp/LLC-PK1: P-gp-transfected LLC-PK1, **p < 0.01.

Next, we investigated the effect of P-gp phosphorylation by PKCβI on the P-gp efflux activity, as measured in terms of uptake of N-methylquinidine (NMQ), a substrate of P-gp, by inside-out membrane vesicles. Recombinant PKCβI treatment significantly decreased the vesicle-to-medium ratio in the inside-out vesicles prepared from P-gp-transfected LLC-PK1 cells (Figure 2(b)). In contrast, no significant change was observed in mock-transfected LLC-PK1 cells. Thus, PKCβI increased the phosphorylation level of P-gp, which suppressed the P-gp efflux activity in P-gp-transfected LLC-PK1 cells. These findings suggest that PKCβI-mediated P-gp phosphorylation caused the decrease of P-gp efflux activity in MSN-knockdown hCMEC/D3 cells.

Quantitative targeted absolute proteomics of ERM proteins in human brain capillaries

In order to see whether ERM proteins might also control transporter functions in the human BBB, we investigated the protein expression amounts of ERM proteins in isolated human brain capillaries, in comparison with hCMEC/D3 cells (Table 3). The protein expression amount of MSN was greatest among the three ERM proteins in both isolated human brain capillaries and hCMEC/D3 cells. The difference in the expression amounts of RDX or MSN between human isolated brain capillaries and hCMEC/D3 cells was within a 3-fold range. The expression amount of EZR in human isolated brain capillaries was under the limit of quantification. These results indicate that ERM proteins contribute to the maintenance of transporter function not only in the in vitro model, but also in the in vivo BBB, at least for RDX and MSN.

Table 3.

Comparison of protein expression amounts of ERM proteins in isolated human brain capillaries and hCMEC/D3 cells.

| Protein expression amount (fmol/µg protein) | Ratio hBCAP/ hCMEC_D3 | |

|---|---|---|

| MSN | ||

| hBCAP | 3.77 ± 0.42 | 0.341 |

| hCMEC/D3 | 11.0 ± 0.6 | |

| RDX | ||

| hBCAP | 1.42 ± 0.27 | 0.776 |

| hCMEC/D3 | 1.83 ± 0.12 | |

| EZR | ||

| hBCAP | U.L.Q. < 1.92 | <0.418 |

| hCMEC/D3 | 4.58 ± 0.24 |

Note: Isolated human brain capillaries from cerebrum (whole-cell lysate) were digested with lysyl endopeptidase and trypsin. The digests were injected into LC-MS/MS together with internal standard peptides. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three to four product ions in a single PRM analysis. Protein expression amounts in whole-cell lysate of hCMEC/D3 cells were taken from Table 1.

hBCAP: human brain capillaries, U.L.Q.: under the limit of quantification.

Discussion

In this work, we clarified the roles of the ERM proteins in the maintenance of P-gp, BCRP and GLUT1 localization and function at the plasma membrane by means of knockdown of studies in a model cell line, hCMEC/D3. We found that P-gp was not regulated by EZR, although the localization of P-gp at the plasma membrane was supported by RDX. Further, although MSN was not required for the maintenance of P-gp localization at the plasma membrane, MSN was involved in the regulation of P-gp efflux activity. All of the ERM proteins served to maintain the localization of BCRP at the plasma membrane. However, unlike EZR and MSN, RDX did not affect BCRP efflux activity, even though the maintenance of BCRP localization was weakened by RDX knockdown. All the ERM proteins contributed to the maintenance of GLUT1 influx activity at the plasma membrane.

Kobori et al.4 demonstrated that repeated treatment of rats with morphine increased P-gp and MSN protein expression levels in the plasma membrane of the brain capillary fraction. They also reported an interaction between P-gp and MSN in untreated rat BBB, based on a co-immunoprecipitation study.4 These findings indicated that the decreased morphine concentration in the brain after repeated doses of morphine is caused by the increase of P-gp-mediated morphine efflux via upregulation of MSN at the BBB. However, it remained unclear whether MSN controlled P-gp efflux activity and expression at the plasma membrane. In this study, we demonstrated that P-gp efflux activity was significantly reduced by knockdown of MSN. This result suggests that the increased MSN expression contributed to the upregulation of P-gp efflux activity at the BBB in morphine-treated rats. The % reduction of P-gp efflux activity was greatest in MSN-knockdown cells, among all the ERM-knockdown cells. Furthermore, MSN was the most abundant ERM protein in hCMEC/D3 cells and human isolated brain capillaries. These findings suggest that MSN has an important role in the regulation of P-gp function at the BBB. However, MSN did not affect the expression amount of P-gp at the plasma membrane, so the previous report of elevated expression of P-gp at the plasma membrane in response to morphine administration may be mediated by a non-MSN mechanism.

Interestingly, MSN knockdown significantly reduced P-gp efflux activity without decreasing P-gp expression amount at the plasma membrane. It was reported that MSN knockdown increased the phosphorylation level of MLC, a substrate of PKCβI, in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells,18,19 suggesting that PKCβI was activated by MSN knockdown. Thus, we hypothesized that PKCβI-mediated P-gp phosphorylation caused the reduction of P-gp efflux activity without loss of P-gp from the plasma membrane. Indeed, we confirmed that PKCβI treatment significantly decreased P-gp efflux activity and increased the phosphorylation levels of amino acids in the linker region in P-gp-expressing membrane vesicles. These results suggest that MSN knockdown induced PKCβI-mediated P-gp phosphorylation in the linker region, and this led to suppression of P-gp efflux activity in hCMEC/D3 cells.

Although EZR was present in hCMEC/D3 cells, it was not detected in isolated human brain capillaries. However, there are a number of possible explanations for this. Firstly, it should be noted that the protein expression amount of EZR in hCMEC/D3 cells (4.58 fmol/µg protein) was close to the limit of quantification (1.92 fmol/µg protein). Thus, it is possible that EZR is also expressed at a level near the lower limit of quantification in isolated human brain capillaries. Secondly, even though we confirmed that there was no gene mutation or post-translational modification in the selected peptides using UniProtKB, there might be some unknown modification or mutation, resulting in failure to detect the target peptides. Further, the sample preparation procedures might not be optimal for EZR. We previously validated the efficient solubilization and digestion of glut1 in mouse brain capillaries and human P-gp in P-gp-overexpressing cells by comparing quantification values obtained with the QTAP method and with binding assays or immunoblotting.7 However, apparent protein abundances can vary from method to method and from protein to protein.22–26 Indeed, a previous comprehensive proteomics analysis identified EZR in isolated bovine brain capillary endothelial cells.27 Thus, method optimization for EZR may enable us to detect EZR at the human BBB in the future.

It is important to know how well hCMEC/D3 cells reflect the molecular mechanisms in the human BBB. Urich et al. found that the mRNA expression levels of transporters, receptors and tight-junction proteins, which are representative determinants of BBB phenotype, were significantly lower in hCMEC/D3 cells than in mouse brain capillary endothelial cells,28 and in particular, mRNA expression levels of P-gp, BCRP and GLUT1 were 38 -, 40 - and 62-fold lower in hCMEC/D3 cells. However, mRNA expression levels of transporters in human liver do not necessarily correlate with the protein expression amounts: among 12 transporters, only organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1) showed a relatively high correlation between mRNA expression level and protein expression amount, while 11 other transporters showed no correlation.29 On the other hand, the transport activities of organic cation/carnitine transporter 1 (OCTN1) and MRP1 were correlated with the respective protein expression amounts in human lung epithelial cells.30 As regards the suitability of hCMEC/D3 cells as a human brain capillary endothelial model, Ohtsuki et al.8 found that the protein expression amounts of 11 out of 12 transporters, including P-gp, BCRP and GLUT1, in hCMEC/D3 cells were within a 4-fold range as compared with those in isolated human brain capillaries (in the case of MRP1, the protein expression amount was determined only in hCMEC/D3 cells). Furthermore, as shown in Table 3, the protein expression amounts of RDX and MSN were within a 3-fold range in hCMEC/D3 cells and isolated human brain capillaries. Therefore, although there are differences of protein abundance, it seems likely that the hCMEC/D3 cell line can serve a useful model for examining the molecular mechanisms of transport systems at the human BBB. Further study is needed to clarify the extent to which this mechanism is reflected at the human BBB.

hCMEC/D3 cells have been reported to maintain a nontransformed phenotype for a limited number of passages (up to 35).11 However, it is unclear whether or not the regulatory mechanisms of transporter function are also maintained over this range of passages. In this study, we confirmed that the % decrease of P-gp efflux activity in ERM-knockdown cells was similar among cells at three different passage numbers. Although the uptake time was different in the experiments using cells at passage 33 (60 min) and at passages 34 and 35 (5 min), the P-gp efflux activity is calculated as the ratio of the inhibitory effect of PSC833, a P-gp inhibitor, on vinblastine excretion by the experimental group (treated with ERM siRNA) to the control group (treated with negative control siRNA), i.e. P-gp efflux activity is evaluated as % of control. Thus, as long as the control group and the experimental group have the same uptake time, the calculated P-gp efflux activity should not depend on the actual value of the uptake time. We previously confirmed that there was no difference in the extents of decrease of P-gp efflux activity (% of control) in H2O2-treated hCMEC/D3 cells measured at uptake time of 5, 20 and 60 min.31 Therefore, we consider that the values of P-gp efflux activity (% of control) obtained at passages 33, 34 and 35 in this work are comparable, and that the regulatory mechanism found in this study is well maintained, at least within this range of passage numbers.

Inadequate drug exposure in the CNS because of the functions of drug efflux transporters at the BBB is likely a major cause of the lack of drug efficacy in several CNS diseases. For example, the anticancer drug temozolomide is the only drug with proven activity against high-grade gliomas, but its brain penetration is limited by P-gp and BCRP, and drug resistance may appear during long-term treatment.32,33 Opioid analgesics such as morphine are widely used for cancer pain management, but repeated treatment with morphine leads to increased drug tolerance due to the upregulation of P-gp function and BCRP expression at the BBB.4,34 In this study, we demonstrated that MSN knockdown markedly decreased P-gp and BCRP efflux activities in hCMEC/D3 cells. Furthermore, MSN is the most abundantly expressed of the ERM proteins in both hCMEC/D3 cells and isolated human brain capillaries. Notably, repeated treatment of rats with morphine increased MSN expression at the BBB,4 suggesting that P-gp- and BCRP-mediated drug resistance could be caused by the upregulation of MSN. If this is the case, MSN at the BBB would be a potential drug target to overcome drug resistance, because the suppression of MSN at the BBB could reduce the P-gp and BCRP efflux functions and thus improve drug delivery into the CNS. Further studies will be needed to determine the extent to which MSN contributes to the development of tolerance to temozolomide and morphine.

Previous reports have showed that the quinocarmycin analog DX-52-1 binds to RDX and MSN and disrupts their binding to actin, as well as transmembrane proteins.35,36 Thus, inhibition of the interactions between ERM proteins and transmembrane proteins by DX52-1 could be a suitable approach for testing the usefulness of targeting MSN to improve drug delivery into the CNS. Although our present findings support this idea, it is essential to consider the potential side effects of targeting MSN. For example, MSN is an important regulator of the immune system,37 playing a non-redundant role in lymphocyte homeostasis. MSN-gene-inactivated mice exhibit lymphopenia in the peripheral blood and lymph nodes due to impaired egress of lymphocytes from lymphoid organs.38 Therefore, it will be important to examine in detail whether targeting MSN to improve CNS drug delivery would be both effective and safe.

In conclusion, our results indicate that the ERM proteins serve to maintain the plasma membrane localizations and transport activities of P-gp, BCRP and GLUT1 in a human BBB model cell line. Furthermore, EZR, MSN and RDX have distinct roles in regulating these transporter functions. In particular, MSN is the most abundantly expressed of the three ERM proteins, and may play a predominant role in maintaining the transport functions of two major drug-efflux transporters, P-gp and BCRP, at the BBB.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplemental Material for Distinct roles of ezrin, radixin and moesin in maintaining the plasma membrane localizations and functions of human blood–brain barrier transporters by Yutaro Hoshi, Yasuo Uchida, Takashi Kuroda, Masanori Tachikawa, Pierre-Olivier Couraud, Takashi Suzuki and Tetsuya Terasaki in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Acknowledgements

We thank A Niitomi and N Handa for their secretarial assistance.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aids from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for Young Scientists (A) [KAKENHI: 16H06218], Scientific Research (B) [KAKENHI: 17H04004], Bilateral Open Partnership Joint Research Program (between Finland and Japan), and JSPS Research Fellow [KAKENHI: 266383]. This study was also supported in part by Grants-in-Aids from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas [KAKENHI: 18H04534], and from Nakatomi Foundation and Takeda Science Foundation.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Tetsuya Terasaki is a full professor at Tohoku University, and also a director of Proteomedix Frontiers Co., Ltd. This study was not supported by Proteomedix Frontiers Co., Ltd., and his position at Proteomedix Frontiers Co., Ltd. did not influence the design of the study, the collection of the data, the analysis or interpretation of the data, the decision to submit the manuscript for publication, or the writing of the manuscript and did not present any financial conflicts. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Yutaro Hoshi and Yasuo Uchida: Study design/conception, analysis/acquisition of data, drafting of manuscript. Takashi Kuroda: Analysis/acquisition of data. Masanori Tachikawa and Tetsuya Terasaki: Study design/conception, revision of manuscript. Pierre-Olivier Couraud: Providing hCMEC/D3 cells. Takashi Suzuki: Providing human brain tissues.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this paper can be found at the journal website: http://journals.sagepub.com/home/jcb

References

- 1.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron 2008; 57: 178–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawaguchi K, Yoshida S, Hatano R, et al. Pathophysiological roles of ezrin/radixin/moesin proteins. Biol Pharm Bull 2017; 40: 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kikuchi S, Hata M, Fukumoto K, et al. Radixin deficiency causes conjugated hyperbilirubinemia with loss of Mrp2 from bile canalicular membranes. Nat Genet 2002; 31: 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobori T, Fujiwara S, Miyagi K, et al. Involvement of moesin in the development of morphine analgesic tolerance through P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2014; 29: 482–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yano K, Tomono T, Sakai R, et al. Contribution of radixin to P-glycoprotein expression and transport activity in mouse small intestine in vivo. J Pharm Sci 2013; 102: 2875–2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brambilla D, Zamboni S, Federici C, et al. P-glycoprotein binds to ezrin at amino acid residues 149-242 in the FERM domain and plays a key role in the multidrug resistance of human osteosarcoma. Int J Cancer 2012; 130: 2824–2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamiie J, Ohtsuki S, Iwase R, et al. Quantitative atlas of membrane transporter proteins: development and application of a highly sensitive simultaneous LC/MS/MS method combined with novel in-silico peptide selection criteria. Pharm Res 2008; 25: 1469–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohtsuki S, Ikeda C, Uchida Y, et al. Quantitative targeted absolute proteomic analysis of transporters, receptors and junction proteins for validation of human cerebral microvascular endothelial cell line hCMEC/D3 as a human blood-brain barrier model. Mol Pharm 2013; 10: 289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uchida Y, Ohtsuki S, Katsukura Y, et al. Quantitative targeted absolute proteomics of human blood-brain barrier transporters and receptors. J Neurochem 2011; 117: 333–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchida Y, Ito K, Ohtsuki S, et al. Major involvement of Na(+)-dependent multivitamin transporter (SLC5A6/SMVT) in uptake of biotin and pantothenic acid by human brain capillary endothelial cells. J Neurochem 2015; 134: 97–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weksler BB, Subileau EA, Perriere N, et al. Blood-brain barrier-specific properties of a human adult brain endothelial cell line. FASEB J 2005; 19: 1872–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshi Y, Uchida Y, Tachikawa M, et al. Actin filament-associated protein 1 (AFAP-1) is a key mediator in inflammatory signaling-induced rapid attenuation of intrinsic P-gp function in human brain capillary endothelial cells. J Neurochem 2017; 141: 247–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito K, Uchida Y, Ohtsuki S, et al. Quantitative membrane protein expression at the blood-brain barrier of adult and younger cynomolgus monkeys. J Pharm Sci 2011; 100: 3939–3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchida Y, Kamiie J, Ohtsuki S, et al. Multichannel liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry cocktail method for comprehensive substrate characterization of multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 transporter. Pharm Res 2007; 24: 2281–2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigor RR, Hawkins BT, Miller DS. Activation of PKC isoform beta(I) at the blood-brain barrier rapidly decreases P-glycoprotein activity and enhances drug delivery to the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010; 30: 1373–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkins BT, Rigor RR, Miller DS. Rapid loss of blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein activity through transporter internalization demonstrated using a novel in situ proteolysis protection assay. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010; 30: 1593–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noack A, Noack S, Hoffmann A, et al. Drug-induced trafficking of p-glycoprotein in human brain capillary endothelial cells as demonstrated by exposure to mitomycin C. PLoS One 2014; 9: e88154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adyshev DM, Moldobaeva NK, Elangovan VR, et al. Differential involvement of ezrin/radixin/moesin proteins in sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced human pulmonary endothelial cell barrier enhancement. Cell Signal 2011; 23: 2086–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haidari M, Zhang W, Willerson JT, et al. Disruption of endothelial adherens junctions by high glucose is mediated by protein kinase C-beta-dependent vascular endothelial cadherin tyrosine phosphorylation. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2014; 13: 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato T, Kodan A, Kimura Y, et al. Functional role of the linker region in purified human P-glycoprotein. FEBS J 2009; 276: 3504–3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uchida Y, Ohtsuki S, Kamiie J, et al. Blood-brain barrier (BBB) pharmacoproteomics: reconstruction of in vivo brain distribution of 11 P-glycoprotein substrates based on the BBB transporter protein concentration, in vitro intrinsic transport activity, and unbound fraction in plasma and brain in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2011; 339: 579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klammer AA, MacCoss MJ. Effects of modified digestion schemes on the identification of proteins from complex mixtures. J Proteome Res 2006; 5: 695–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brun V, Dupuis A, Adrait A, et al. Isotope-labeled protein standards: toward absolute quantitative proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 2007; 6: 2139–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brun V, Masselon C, Garin J, et al. Isotope dilution strategies for absolute quantitative proteomics. J Proteomics 2009; 72: 740–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proc JL, Kuzyk MA, Hardie DB, et al. A quantitative study of the effects of chaotropic agents, surfactants, and solvents on the digestion efficiency of human plasma proteins by trypsin. J Proteome Res 2010; 9: 5422–5437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balogh LM, Kimoto E, Chupka J, et al. Membrane protein quantification by peptide-based mass spectrometry approaches: studies on the organic anion-transporting polypeptide family. J Proteomics Bioinform 2012; 6: 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pottiez G, Duban-Deweer S, Deracinois B, et al. A differential proteomic approach identifies structural and functional components that contribute to the differentiation of brain capillary endothelial cells. J Proteomics 2011; 75: 628–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urich E, Lazic SE, Molnos J, et al. Transcriptional profiling of human brain endothelial cells reveals key properties crucial for predictive in vitro blood-brain barrier models. PLoS One 2012; 7: e38149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohtsuki S, Schaefer O, Kawakami H, et al. Simultaneous absolute protein quantification of transporters, cytochromes P450, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases as a novel approach for the characterization of individual human liver: comparison with mRNA levels and activities. Drug Metab Dispos 2012; 40: 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakamoto A, Suzuki S, Matsumaru T, et al. Correlation of organic cation/carnitine transporter 1 and multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 transport activities with protein expression levels in primary cultured human tracheal, bronchial, and alveolar epithelial cells. PLoS One 2012; 7: e38149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoshi Y, Uchida Y, Tachikawa M, et al. Oxidative stress-induced activation of Abl and Src kinases rapidly induces P-glycoprotein internalization via phosphorylation of caveolin-1 on tyrosine-14, decreasing cortisol efflux at the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab Epub ahead of print 9 January 2019. DOI: 10.1177/0271678X18822801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Gooijer MC, de Vries NA, Buckle T, et al. Improved brain penetration and antitumor efficacy of temozolomide by inhibition of ABCB1 and ABCG2. Neoplasia 2018; 20: 710–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haar CP, Hebbar P, Wallace GC, et al. Drug resistance in glioblastoma: a mini review. Neurochem Res 2012; 37: 1192–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yousif S, Chaves C, Potin S, et al. Induction of P-glycoprotein and Bcrp at the rat blood-brain barrier following a subchronic morphine treatment is mediated through NMDA/COX-2 activation. J Neurochem 2012; 123: 491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahsai AW, Zhu S, Wardrop DJ, et al. Quinocarmycin analog DX-52-1 inhibits cell migration and targets radixin, disrupting interactions of radixin with actin and CD44. Chem Biol 2006; 13: 973–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu X, Morales FC, Agarwal NK, et al. Moesin is a glioma progression marker that induces proliferation and Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation via interaction with CD44. Cancer Res 2013; 73: 1142–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shcherbina A, Bretscher A, Kenney DM, et al. Moesin, the major ERM protein of lymphocytes and platelets, differs from ezrin in its insensitivity to calpain. FEBS Lett 1999; 443: 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirata T, Nomachi A, Tohya K, et al. Moesin-deficient mice reveal a non-redundant role for moesin in lymphocyte homeostasis. Int Immunol 2012; 24: 705–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplemental Material for Distinct roles of ezrin, radixin and moesin in maintaining the plasma membrane localizations and functions of human blood–brain barrier transporters by Yutaro Hoshi, Yasuo Uchida, Takashi Kuroda, Masanori Tachikawa, Pierre-Olivier Couraud, Takashi Suzuki and Tetsuya Terasaki in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism