Abstract

Cerebral oxygen extraction fraction is an important physiological index of the brain’s oxygen consumption and supply and has been suggested to be a potential biomarker for a number of diseases such as stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, sickle cell disease, and metabolic disorders. However, in order for oxygen extraction fraction to be a sensitive biomarker for personalized disease diagnosis, inter-subject variations in normal subjects must be minimized or accounted for, which will otherwise obscure its interpretation. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the physiological underpinnings of normal differences in oxygen extraction fraction. This work used two studies, one discovery study and one verification study, to examine the extent to which an individual’s end-tidal CO2 can explain variations in oxygen extraction fraction. It was found that, across normal subjects, oxygen extraction fraction is inversely correlated with end-tidal CO2. Approximately 50% of the inter-subject variations in oxygen extraction fraction can be attributed to end-tidal CO2 differences. In addition, oxygen extraction fraction was found to be positively associated with age and systolic blood pressure. By accounting for end-tidal CO2, age, and systolic blood pressure of the subjects, normal variations in oxygen extraction fraction can be reduced by 73%, which is expected to substantially enhance the utility of oxygen extraction fraction as a disease biomarker.

Keywords: Oxygen extraction fraction, end-tidal CO2, T2-Relaxation-Under-Spin-Tagging, variation, venous oxygenation

Introduction

Cerebral oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) is a key physiological index of the homeostasis of oxygen demand and supply in the human brain. Previous studies suggested that brain OEF, even just measured at a global level, may be a useful biomarker in a variety of diseases, such as stroke,1–4 arteriostenosis,5,6 Alzheimer’s disease,7 multiple sclerosis,8 metabolic disorder,9 anorexia,10 end stage renal disease,11 hepatic encephalopathy,12 and sickle cell disease.5,13,14 Therefore, quantitative assessment of OEF is of potential clinical value for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of neurological conditions.

Multiple imaging modalities have been used to measure OEF in humans. Positron emission tomography (PET) with 15O-labeled tracers have been used extensively for OEF determination,15 although its use has diminished in recent years due to the need of on-site cyclotron, arterial sampling, and the exposure to ionizing radiation. Near-infrared optical spectroscopy has also been used to measure OEF of the brain, especially in neonates in whom the depth of light penetration is sufficient.16 More recently, with the advances of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) methods, a number of techniques have been proposed to measure cerebral OEF without any exogenous agent,17–31 thus potentially enabling the routine assessment of OEF in adult human patients. These techniques were based on the association between blood oxygenation level and MR properties of the blood, such as T2,17–22 susceptibility,23–29 and phase.30,31 These approaches allow the determination of brain OEF on standard MRI within just a few minutes.17–19,21–26

However, one issue that remains to cloud the prospect of OEF as a useful biomarker in brain diseases is the fact that there exist considerable inter-subject variations in OEF within the healthy population.32–35 For example, in a multi-center study involving 250 healthy subjects, an inter-subject coefficient of variation (CoV) of 16% in OEF was observed using a T2-Relaxation-Under-Spin-Tagging (TRUST) MRI method.33 Similarly, an inter-subject CoV of 13% in OEF has been reported by Ito et al. in a multi-center study of 70 healthy volunteers using the 15O-PET method.34 These inter-subject variations are expected to obscure the interpretation of OEF data and weaken the power of OEF as a diagnostic marker. Therefore, it is important to investigate the physiological underpinnings of OEF variations among normal subjects.

End-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2), the partial pressure of CO2 in the exhaled air at end-expiration and closely related to the arterial CO2 level (PaCO2),36,37 is known to have a major influence on cerebral hemodynamic parameters.38,39 Moreover, it has been reported in a within-subject setting (e.g. before and after hypercapnia challenge) that EtCO2 is negatively associated with cerebral OEF.24,40–42 Therefore, we hypothesized that variations in OEF among normal subjects can be partly attributed to their differences in EtCO2. In this work, we conducted two studies, one discovery study and one verification study, to examine the extent to which EtCO2 can explain inter-subject variations in cerebral OEF. In addition, we investigated the potential effects of other physiological parameters, including systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and heart rate (HR), on OEF.

Material and methods

Participants

Two studies were performed. Study 1 was a discovery study conducted on young healthy adults. Study 2 was a verification study conducted on a larger cohort of elderly subjects with normal cognitive functions. The study protocols were approved by Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board. Both studies were performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines of Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board, which were based on The Belmont Report, the Declaration of Helsinki, and The Nuremberg Code. All subjects gave written informed consents before participating in the study.

In Study 1, we recruited 10 young adult volunteers (24.0 ± 3.2 years old, ranging from 19 to 31 years old; 4 females, 6 males) via local advertisements. All subjects were in general good health according to self-report.

In Study 2, 25 cognitively normal elderly subjects (69.5 ± 6.7 years old, ranging from 59 to 83 years old; 18 females, 7 males) were recruited. All subjects enrolled in this study had a score of 0 in the Clinical Dementia Rating and a mean score of 27.6 ± 1.6 (mean ± SD) in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and were assigned the status of cognitively normal via a consensus between a neuropsychologist, a gerontologist, and a psychiatrist, based on their medical histories and performances on cognitive tasks. Subjects with any other medical, psychiatric, or neurological conditions that could affect cognition were also excluded.

Measurement of OEF

Whole brain OEF was evaluated using TRUST MRI. The details of TRUST have been described previously.17,18 Briefly, TRUST MRI is based on the well-established relationship between blood oxygenation and blood T2.43 To isolate pure venous blood signal from surrounding tissues, TRUST utilizes radiofrequency (RF) pulses to label the incoming venous blood and acquires labeled and control images by alternating the RF pulses. Pair-wise subtraction of control and labeled images yields pure venous blood signal in the superior sagittal sinus (SSS), eliminating partial-volume effects. The T2 of the blood signal was quantified by exploiting T2-preparation with varying numbers of refocusing RF pulses, which is characterized by the effective echo time (eTE). Blood T2 is then converted to venous oxygenation (Yv) via known calibration plots.43 Finally, OEF can be computed by

| (1) |

where Ya is the arterial oxygenation, and was assumed to be 98% in this work.

MRI experiments

In Study 1, the subjects were scanned on a 3T Siemens Prisma system (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Each subject underwent three TRUST scans. A nasal cannula (Model 4000F-7, Salter Labs, Arvin, CA, USA) was used to sample the exhaled gas during the TRUST scans, and EtCO2 was measured using a capnograph device (Capnogard Model 1265, Novametrix Medical Systems, Wallingford, CT, USA). To improve data stability, the OEF and EtCO2 were averaged across the three TRUST scans.

In Study 2, the subjects were scanned on a 3T Philips Achieva system (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). Each subject underwent one TRUST scan, among other MRI sequences. EtCO2 of the subject during the TRUST scan was sampled by nasal cannula (Model 4000F-7, Salter Labs, Arvin, CA, USA) and recorded with a capnograph device (NM3 Respiratory Profile Monitor, Model 7900, Philips Healthcare, Wallingford, CT, USA). We also collected other physiological parameters, which were SBP, DBP, and HR, from each subject during the same visit as the MRI scan. SBP, DBP, and HR were measured at the brachial level in seated position using automatic devices (Patient Monitor Model 3150M, Invivo, Orlando, FL, USA; Omron Model BP742N, Omron Healthcare, Lake Forest, IL, USA), and were measured twice before the MRI scan and twice after the MRI scan. Values of SBP, DBP, and HR were averaged across the four measurements for each subject. In addition, the hematocrit level was measured from each subject through a blood draw.

In both studies, the MRI experiments were performed using a body coil for transmission and a 32-channel head coil for receiving. Foam padding was placed around the head to minimize motion during the MRI scans. TRUST was performed with the following sequence parameters: field of view = 220 × 220 × 5 mm3, repetition time = 3 s; inversion time = 1.02 s; voxel size = 3.44 × 3.44 × 5 mm3; labeling slab thickness = 100 mm; gap = 22.5 mm; four eTEs: 0, 40, 80 and 160 ms; and scan duration = 1.2 min. The echo time (TE) of TRUST was 6.5 ms in Study 1 on the Siemens scanner and 3.6 ms in Study 2 on the Philips scanner. The difference in TE was due to the slightly different implementations of the TRUST pulse sequence on the two MR vendors. A previous report on multi-vendor comparison of TRUST MRI has demonstrated that the performance of these two implementations is highly compatible.44

Data processing

The TRUST MRI data were processed with in-house MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA) scripts, following established procedures reported in the literature.17 Briefly, after motion correction, pair-wise subtraction between control and labeled images was conducted to obtain the difference images, on which a preliminary region of interest (ROI) was drawn encompassing the SSS. Four voxels inside the ROI with the highest signal intensities were selected as the final mask. Blood signals in the final mask were spatially averaged for each eTE and were fitted monoexponentially as a function of eTEs to obtain the T2 of blood. Blood T2 was then converted to Yv using well-established calibration plots, considering hematocrit of the subject.43 In Study 1, hematocrit was assumed to be 0.42 for males and 0.40 for females; whereas in Study 2, hematocrit used the subject-specific measured values. In addition, as a metric of the quality of Yv data, the width of the 95% confidence interval of 1/T2 was quantified from the monoexponential fitting procedure, and was hereafter referred to as ΔR2. TRUST scans with ΔR2 ≥ 5 Hz would suggest a poor data quality and were excluded from statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

In Study 1, linear regression analyses were performed using OEF as the dependent variable and EtCO2 as the independent variable. Age was included as a covariate, since the association between age and OEF has been reported in multiple studies.33,45–47 Gender was not considered as a covariate because it has been shown to be not associated with OEF in recent literature.33 A P value less than 0.05 is considered significant.

Based on the data in Study 1, power calculation was performed for Study 2. The power calculation used the slope and EtCO2 standard deviation measured in Study 1. For the standard deviation of the dependent variable, OEF, we used results in Study 1 but also considered the fact that Study 2 was performed in elderly individuals who may have larger measurement noise and that the TRUST sequence was performed only once. The power calculation used the “Power and Sample Size Calculation” software48 and revealed that the power to observe a significant association between EtCO2 and OEF was 97%.

In Study 2, since we have multiple candidate modulators of OEF, step-wise linear regression analyses were performed to investigate the dependence of OEF on physiological parameters. In these analyses, OEF was the dependent variable and the candidate independent variables were EtCO2, SBP, DBP, and HR. Age was always included in the regression model. The candidate independent variables were added to the regression model in a step-wise manner, starting from the most significant one until there were no more variables with a P < 0.05.

Results

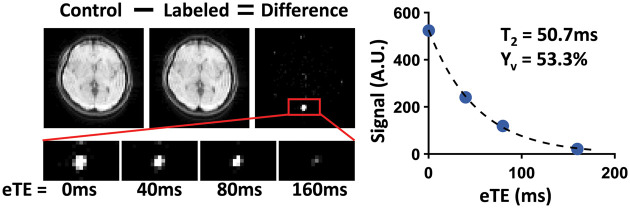

Figure 1 shows a representative data set of TRUST MRI. Subtraction of labeled image from the control yields strong venous blood signal in the SSS, which decays with eTEs. The scatter plot shows the averaged blood signal as a function of eTEs as well as the monoexponential fitting results. Table 1 summarizes the physiological measurements.

Figure 1.

A representative data set of TRUST MRI. Subtraction of the labeled image from the control yields strong venous blood signal in the SSS, which decays with eTEs. The control and labeled images are only shown for eTE = 0 ms, while the zoomed-in views of difference images are shown for all four eTEs. The plot on the right displays averaged blood signal as a function of eTEs. The blood T2 obtained from monoexponential fitting and the corresponding Yv are also shown.

eTE: effective echo time.

Table 1.

Summary of physiological measurements.

| Parameter | Study 1 | Study 2 |

|---|---|---|

| EtCO2 (mmHg) | 38.4 ± 2.6 | 34.3 ± 4.3 |

| SBP (mmHg) | − | 145.5 ± 19.5 |

| DBP (mmHg) | − | 85.4 ± 12.3 |

| HR (beats per minute) | − | 70.8 ± 10.5 |

| Hematocrit | − | 0.41 ± 0.03 |

HR: heart rate; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

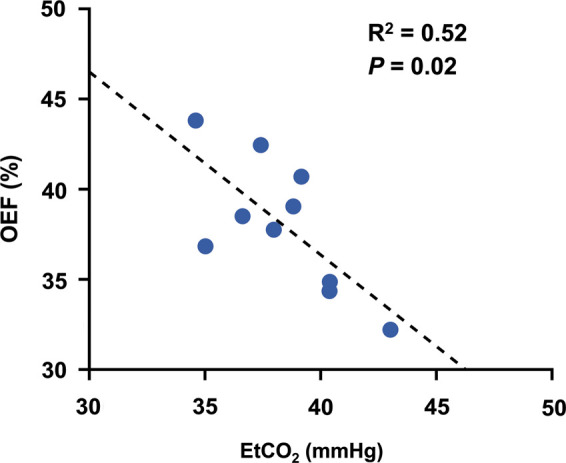

For data from Study 1, one TRUST scan of one subject was excluded due to a ΔR2 ≥ 5 Hz, and the remaining two TRUST scans were used to compute the OEF of this subject. The OEF and EtCO2 of the young subjects in Study 1 were 38.0 ± 3.7% and 38.4 ± 2.6 mmHg, respectively, which were in good agreement with previous reports on young healthy subjects.32,41 Figure 2 shows a scatter plot of OEF and EtCO2 across subjects. Univariate linear regression showed that OEF was negatively correlated with EtCO2 (P = 0.02, R2 = 0.52). The association between OEF and EtCO2 remained significant (P = 0.04) after adding age as a covariate, as shown in Table 2. Individuals with a higher EtCO2 tend to have a lower OEF, at a rate of −0.90 ± 0.36% per mmHg CO2.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of OEF and EtCO2 for young healthy subjects (N = 10). The dashed line shows the fitting curve.

OEF: oxygen extraction fraction; EtCO2: end-tidal carbon dioxide.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression using OEF (%) as the dependent variable in young healthy subjects, R2 = 0.59.

| Variables | β ± SE | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.33 ± 0.28 | 0.29 |

| EtCO2 | −0.90 ± 0.36 | 0.04 |

β: standardized beta coefficient; SE: standardized error; EtCO2: end-tidal carbon dioxide.

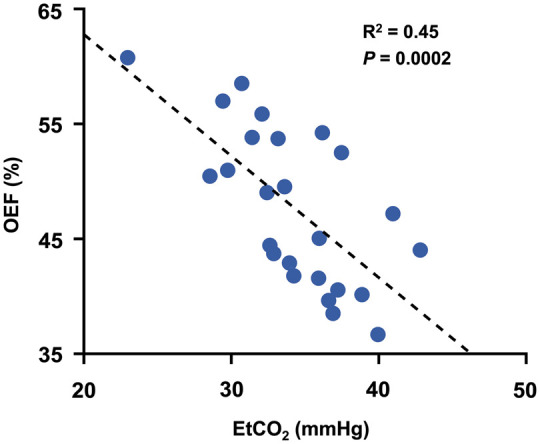

For data from Study 2, all TRUST scans had ΔR2 < 5 Hz. The OEF and EtCO2 of the elderly subjects were 47.7 ± 6.8% and 34.3 ± 4.3 mmHg, respectively. A two-sample t-test assuming equal variance revealed that the elderly subjects in Study 2 had a lower EtCO2 (P = 0.01) and higher OEF (P = 0.0002) than the young subjects in Study 1. These observations are in agreement with previous reports on these physiological variables.45,46,49 The SBP, DBP, and HR of the elderly subjects were 145.5 ± 19.5 mmHg, 85.4 ± 12.3 mmHg and 70.8 ± 10.5 beats per minute, respectively. Figure 3 displays a scatter plot of OEF and EtCO2 across subjects, showing a strong negative correlation (P = 0.0002, R2 = 0.45). Table 3 summarizes the results of stepwise linear regression analyses. It was found that OEF is negatively associated with EtCO2 (P = 2 × 10−6), but positively associated with age (P = 0.002) and SBP (P = 0.01). Importantly, EtCO2 alone can explain about 50% of the inter-subject variations in OEF, which is similar to the findings in Study 1. Furthermore, age, EtCO2, and SBP together can account for a total of 73% of the normal variations in OEF. HR and DBP did not enter the final stepwise model (P > 0.1). However, further investigation suggested that HR, DBP, and SBP contributed similar sources of variations to OEF, in that when only one of these three was included in the model (without the other two), their effect on OEF was significant (see Supplementary Table S1 and S2).

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of OEF and EtCO2 for cognitively normal elderly subjects (N = 25). The dashed line indicates the fitting curve.

OEF: oxygen extraction fraction; EtCO2: end-tidal carbon dioxide.

Table 3.

Stepwise linear regression using OEF (%) as the dependent variable in cognitively normal elderly subjects.

| Variables | β ± SE | P | ΔModel R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.40 ± 0.12 | 0.002 | 0.13 |

| EtCO2 | −1.19 ± 0.18 | 2 × 10−6 | 0.49 |

| SBP | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

β: standardized beta coefficient; SE: standardized error; EtCO2: end-tidal carbon dioxide.

Discussion

This work demonstrated that across normal subjects, OEF is inversely correlated with EtCO2. From the slope of the linear regression results, it appeared that one unit (i.e. mmHg) increase of EtCO2 corresponds to approximately one unit (i.e. %) decrease in OEF. Furthermore, EtCO2 alone can account for about 50% of inter-subject variations in OEF. These findings were reproducible in two different populations (young and elderly subjects) and on two different MR systems (Siemens and Philips). In addition, OEF is positively associated with age and SBP. By accounting for EtCO2, age, and SBP, inter-subject variations in OEF can be reduced by 73%, which may significantly improve the sensitivity of OEF as a disease biomarker.

As an important index of the homeostasis of the brain’s oxygen metabolism, OEF has found clinical utility in a large number of diseases. For example, increased OEF has been demonstrated to be a strong and independent predictor of stroke risk in patients with cerebral arterial occlusive diseases.1–4 Decreased OEF values have been reported in patients with mild cognitive impairment7 and patients with multiple sclerosis,8 while elevated OEF has been found in patients with moyamoya disease,5 hepatic encephalopathy,12 or end-stage renal disease.11 Alterations in OEF have also been reported in sickle cell disease patients, although it is still controversial whether OEF is elevated5,14 or diminished.13 It is also possible that OEF can be used for treatment monitoring and thereby developing new interventions (i.e. endpoint in clinical trials). However, due to considerable inter-subject variations in OEF even in the healthy population,32–35 the detection of disease-related abnormalities in OEF is mostly based on a group level. In this work, we demonstrated that by accounting for EtCO2 alone, inter-subject variations in OEF can be reduced by about 50%. Given that EtCO2 can be easily measured with a commercial capnograph device, recording of EtCO2 during OEF measurements may be a cost-effective approach to enhance the sensitivity of detecting disease-related abnormalities on an individual level. Another approach to evaluate the effect size of EtCO2 on OEF is to study the extent of EtCO2 variations in daily life. Based on our data, EtCO2 variations within the same scan session is 0.5 ± 0.4 mmHg (mean ± SD). A previous study reported that between-day variations in EtCO2 were 1.06 mmHg.50 EtCO2 was found to increase during intensive exercise,51,52 but returned to pre-exercise level a few minutes after exercise.51 Food consumption could also have an effect on EtCO2. Patik et al. reported a slight increase in EtCO2 (by about 2 mmHg) after fast-food meal,53 while Zwillich et al. found no significant change in EtCO2 after carbohydrate-rich or protein-rich meal.54 Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that an individual’s OEF would change by 2–3% just by day-to-day variations.

The mechanism underlying the observed inverse correlation between OEF and EtCO2 is likely related to the vasoactive effect of CO2. CO2 is known to be a potent vasodilator. Higher EtCO2 is expected to result in a higher cerebral blood flow (CBF). In an intra-subject setting, it is well established from previous 15O-PET and MRI studies that increases in blood CO2 content result in an augmentation in CBF.38,41,49,55 Several prior reports have also noted a similar relationship in an inter-subject setting, in that there exists a positive association between EtCO2 and CBF across individuals.56,57 If brain metabolic rate is similar (or not as variable) across subjects, it can be readily derived that OEF will be lower in individuals with a higher EtCO2, as OEF is related to the ratio between metabolism and CBF. There are also reports that a higher EtCO2 may result in a lower metabolic rate of the brain due to a tissue acidosis effect of CO2.41,58,59 This effect would also result in a lower OEF. There is also a possibility that a lower OEF may result in decreased activity in chemoreceptor neurons in the brain that innervates the respiratory neurons in the brain stem, resulting in a reduced respiration and thereby a higher EtCO2.60 However, in studies of cerebral arterial occlusion patients, the results of EtCO2 were mixed, with some showing slightly higher61 and others showing slightly lower62 EtCO2 in occlusion patients.

The influence of EtCO2 on other cerebral physiological parameters has also been reported. Besides the association between EtCO2 and CBF,56,57 it has also been suggested that, across subjects, baseline EtCO2 is inversely correlated with cerebrovascular reactivity measured with BOLD MRI and CO2 inhalation.63

It should be emphasized that the present study reports physiological associations on an inter-subject level. Intra-subject correlations between OEF and EtCO2 have been reported previously. For example, it is known that, when an individual’s arterial CO2 is elevated by inhalation of hypercapnic gas or by breath-holding, OEF decreases as a result of CBF increase.24,40–42 However, to our best knowledge, no prior studies have reported this relationship in an inter-subject setting. We note that it is not trivial to extend intra-subject observations to inter-subject, because inter-subject variations in physiological parameters are often caused by multiple factors. In the case of OEF, many other sources, such as basal metabolic rate, intake of caffeine, vasoactive medications, and so on, could have resulted in variations in OEF across individuals. Therefore, the observations in this study are novel in that it identifies EtCO2 as the leading physiological factor that explains normal inter-subject variations in OEF.

Besides the negative correlation between OEF and EtCO2, in Study 2, we also found that after adjusting for EtCO2, OEF is positively associated with age and SBP. The increase in OEF with age agreed with previous reports using 15O-PET oximetry47,64 or TRUST MRI.33,45,46 Increased OEF with age is thought to be attributed to a decrease in CBF with age,45–47 as well as additional effects of an elevation in cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen.45,46 As for the blood pressure, it has been previously reported that OEF is positively associated with mean arterial blood pressure,65,66 which is thought to be a compensatory response to a diminished CBF at high blood pressures.65–67 It is worth noting that in univariate linear regression analyses, OEF showed no significant associations with age (P = 0.07) or SBP (P = 0.26), whereas the associations became significant after accounting for EtCO2 (P = 0.002 for age; P = 0.01 for SBP). This finding provides an early indication that consideration of EtCO2 reduces noise in the data and helps reveal the dependence of OEF on other physiological (and potentially pathological) factors.

We observed that elderly subjects in Study 2 had significantly lower EtCO2 than the young subjects in Study 1. This is consistent with previous literature that EtCO2 in subjects more than 50 years of age was significantly lower than young subjects less than 30 years of age.68 Additionally, De Vis et al. reported that young subjects (aged 28 ± 3 years) had a mean EtCO2 of 39 ± 3 mmHg and elderly subjects (aged 66 ± 4 years) had a significantly lower EtCO2 of 35 ± 3 mmHg,49 which agreed well with our observations.

There are a few limitations of the present work. First, the measurements of OEF in this work were on a whole brain level, without spatial information. Thus, it is not clear whether the association between OEF and EtCO2 is region dependent. As new region-specific OEF techniques become available,19,20,22,26,30,31 spatial specificity of this relationship should be studied. However, it should be pointed out that the strengths of the TRUST MRI technique used in this study include its short scan time (1.2 min), excellent test–retest reproducibility,32 and scalability across multiple sites33 and across different MR vendors.44 A second limitation is that the studies performed in this work were focused on normal subjects. Future work is needed to investigate the extent to which this relationship can hold in patients with brain diseases. For example, in diseases where vascular reserve is exhausted or severely impaired such as in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease69–71 and arteriostenosis,62,72 the dependence of OEF on EtCO2 will be attenuated or even abolished. Therefore, caution needs to be taken when applying the relationship reported in the present study in diseased populations. A third limitation is that blood pressure in this study was measured at seated position, while the MRI-OEF measure was obtained at supine position. There have been some reports that blood pressure measured at different positions could yield slightly different values.73–78 We had chosen to conduct the blood pressure measurement at seated position to be consistent with standard clinical practice and to reduce patient burden. We expect that, as long as the measurement is always performed at seated position, the observed relationship will be applicable.

In conclusion, the present work suggests that across normal subjects, OEF is inversely correlated with EtCO2, and about 50% of the inter-subject variations in OEF can be attributed to their EtCO2 differences. We also found that OEF is positively associated with age and SBP. If EtCO2, age, and SBP information can be obtained from the subjects, one can reduce the variation of OEF data by 73%, which is expected to substantially enhance the utility of OEF as a disease biomarker.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Normal variations in brain oxygen extraction fraction are partly attributed to differences in end-tidal CO2 by Dengrong Jiang, Zixuan Lin, Peiying Liu, Sandeepa Sur, Cuimei Xu, Kaisha Hazel, George Pottanat, Sevil Yasar, Paul Rosenberg, Marilyn Albert and Hanzhang Lu in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 MH084021, R01 NS106711, R01 NS106702, R01 AG047972, R21 NS095342, R21 NS085634, P41 EB015909 and UH2 NS100588.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

DJ acquired the data, analyzed the data, and drafted the article. ZL, PL, and CX acquired the MRI data. SS, KH, and GP recruited subjects, acquired, and analyzed cognitive test data. SY, PR, and MA analyzed and interpreted the cognitive and clinical data. HL designed the study, guided the experiments and data analyses, and revised the article.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this paper can be found at the journal website: http://journals.sagepub.com/home/jcb

References

- 1.Derdeyn CP, Videen TO, Yundt KD, et al. Variability of cerebral blood volume and oxygen extraction: stages of cerebral haemodynamic impairment revisited. Brain 2002; 125: 595–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamauchi H, Fukuyama H, Nagahama Y, et al. Evidence of misery perfusion and risk for recurrent stroke in major cerebral arterial occlusive diseases from PET. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996; 61: 18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grubb RL, Jr, Derdeyn CP, Fritsch SM, et al. Importance of hemodynamic factors in the prognosis of symptomatic carotid occlusion. JAMA 1998; 280: 1055–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derdeyn CP, Videen TO, Grubb RL, Jr, et al. Comparison of PET oxygen extraction fraction methods for the prediction of stroke risk. J Nucl Med 2001; 42: 1195–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watchmaker JM, Juttukonda MR, Davis LT, et al. Hemodynamic mechanisms underlying elevated oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) in moyamoya and sickle cell anemia patients. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018; 38: 1618–1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavec M, Usenius JP, Tuunanen PI, et al. Assessment of cerebral hemodynamics and oxygen extraction using dynamic susceptibility contrast and spin echo blood oxygenation level-dependent magnetic resonance imaging: applications to carotid stenosis patients. Neuroimage 2004; 22: 258–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas BP, Sheng M, Tseng BY, et al. Reduced global brain metabolism but maintained vascular function in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 1508–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ge Y, Zhang Z, Lu H, et al. Characterizing brain oxygen metabolism in patients with multiple sclerosis with T2-relaxation-under-spin-tagging MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 403–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pascual JM, Liu P, Mao D, et al. Triheptanoin for glucose transporter type I deficiency (G1D): modulation of human ictogenesis, cerebral metabolic rate, and cognitive indices by a food supplement. JAMA Neurol 2014; 71: 1255–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheng M, Lu H, Liu P, et al. Cerebral perfusion differences in women currently with and recovered from anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res 2015; 232: 175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng G, Wen J, Lu H, et al. Elevated global cerebral blood flow, oxygen extraction fraction and unchanged metabolic rate of oxygen in young adults with end-stage renal disease: an MRI study. Eur Radiol 2016; 26: 1732–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng G, Lu H, Yu W, et al. Severity-specific alterations in CBF, OEF and CMRO2 in cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Eur Radiol 2017; 27: 4699–4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bush AM, Coates TD, Wood JC. Diminished cerebral oxygen extraction and metabolic rate in sickle cell disease using T2 relaxation under spin tagging MRI. Magn Reson Med 2018; 80: 294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan LC, Gindville MC, Scott AO, et al. Non-invasive imaging of oxygen extraction fraction in adults with sickle cell anaemia. Brain 2016; 139: 738–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mintun MA, Raichle ME, Martin WR, et al. Brain oxygen utilization measured with O-15 radiotracers and positron emission tomography. J Nucl Med 1984; 25: 177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roche-Labarbe N, Carp SA, Surova A, et al. Noninvasive optical measures of CBV, StO(2), CBF index, and rCMRO(2) in human premature neonates' brains in the first six weeks of life. Hum Brain Mapp 2010; 31: 341–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu H, Ge Y. Quantitative evaluation of oxygenation in venous vessels using T2-relaxation-under-spin-tagging MRI. Magn Reson Med 2008; 60: 357–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu F, Uh J, Liu P, et al. On improving the speed and reliability of T2-relaxation-under-spin-tagging (TRUST) MRI. Magn Reson Med 2012; 68: 198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo J, Wong EC. Venous oxygenation mapping using velocity-selective excitation and arterial nulling. Magn Reson Med 2012; 68: 1458–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolar DS, Rosen BR, Sorensen AG, et al. QUantitative Imaging of eXtraction of oxygen and TIssue consumption (QUIXOTIC) using venular-targeted velocity-selective spin labeling. Magn Reson Med 2011; 66: 1550–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain V, Magland J, Langham M, et al. High temporal resolution in vivo blood oximetry via projection-based T2 measurement. Magn Reson Med 2013; 70: 785–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnamurthy LC, Liu P, Ge Y, et al. Vessel-specific quantification of blood oxygenation with T2-relaxation-under-phase-contrast MRI. Magn Reson Med 2014; 71: 978–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wehrli FW, Fan AP, Rodgers ZB, et al. Susceptibility-based time-resolved whole-organ and regional tissue oximetry. NMR Biomed 2017; 30: e3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain V, Langham MC, Floyd TF, et al. Rapid magnetic resonance measurement of global cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen consumption in humans during rest and hypercapnia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 1504–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernandez-Seara MA, Techawiboonwong A, Detre JA, et al. MR susceptometry for measuring global brain oxygen extraction. Magn Reson Med 2006; 55: 967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He X, Yablonskiy DA. Quantitative BOLD: mapping of human cerebral deoxygenated blood volume and oxygen extraction fraction: default state. Magn Reson Med 2007; 57: 115–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu B, Liu T, Spincemaille P, et al. Flow compensated quantitative susceptibility mapping for venous oxygenation imaging. Magn Reson Med 2014; 72: 438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.An H, Lin W. Quantitative measurements of cerebral blood oxygen saturation using magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2000; 20: 1225–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haacke EM, Lai S, Reichenbach JR, et al. In vivo measurement of blood oxygen saturation using magnetic resonance imaging: a direct validation of the blood oxygen level-dependent concept in functional brain imaging. Hum Brain Mapp 1997; 5: 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan AP, Bilgic B, Gagnon L, et al. Quantitative oxygenation venography from MRI phase. Magn Reson Med 2014; 72: 149–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan AP, Benner T, Bolar DS, et al. Phase-based regional oxygen metabolism (PROM) using MRI. Magn Reson Med 2012; 67: 669–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu P, Xu F, Lu H. Test-retest reproducibility of a rapid method to measure brain oxygen metabolism. Magn Reson Med 2013; 69: 675–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu P, Dimitrov I, Andrews T, et al. Multisite evaluations of a T2-relaxation-under-spin-tagging (TRUST) MRI technique to measure brain oxygenation. Magn Reson Med 2016; 75: 680–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ito H, Kanno I, Kato C, et al. Database of normal human cerebral blood flow, cerebral blood volume, cerebral oxygen extraction fraction and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen measured by positron emission tomography with 15O-labelled carbon dioxide or water, carbon monoxide and oxygen: a multicentre study in Japan. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2004; 31: 635–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coles JP, Fryer TD, Bradley PG, et al. Intersubject variability and reproducibility of 15O PET studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2006; 26: 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barton CW, Wang ES. Correlation of end-tidal CO2 measurements to arterial PaCO2 in nonintubated patients. Ann Emerg Med 1994; 23: 560–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McSwain SD, Hamel DS, Smith PB, et al. End-tidal and arterial carbon dioxide measurements correlate across all levels of physiologic dead space. Respir Care 2010; 55: 288–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grubb RL, Jr, Raichle ME, Eichling JO, et al. The effects of changes in PaCO2 on cerebral blood volume, blood flow, and vascular mean transit time. Stroke 1974; 5: 630–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vazquez AL, Cohen ER, Gulani V, et al. Vascular dynamics and BOLD fMRI: CBF level effects and analysis considerations. Neuroimage 2006; 32: 1642–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng SL, Ravi H, Sheng M, et al. Searching for a truly “iso-metabolic” gas challenge in physiological MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 715–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu F, Uh J, Brier MR, et al. The influence of carbon dioxide on brain activity and metabolism in conscious humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen JJ, Pike GB. Global cerebral oxidative metabolism during hypercapnia and hypocapnia in humans: implications for BOLD fMRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010; 30: 1094–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu H, Xu F, Grgac K, et al. Calibration and validation of TRUST MRI for the estimation of cerebral blood oxygenation. Magn Reson Med 2012; 67: 42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang D, Liu P, Li Y, et al. Cross-vendor harmonization of T2-relaxation-under-spin-tagging (TRUST) MRI for the assessment of cerebral venous oxygenation. Magn Reson Med 2018; 80: 1125–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng SL, Dumas JA, Park DC, et al. Age-related increase of resting metabolic rate in the human brain. Neuroimage 2014; 98: 176–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu H, Xu F, Rodrigue KM, et al. Alterations in cerebral metabolic rate and blood supply across the adult lifespan. Cereb Cortex 2011; 21: 1426–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aanerud J, Borghammer P, Chakravarty MM, et al. Brain energy metabolism and blood flow differences in healthy aging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 1177–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dupont WD, Plummer WD, Jr. Power and sample size calculations for studies involving linear regression. Control Clin Trials 1998; 19: 589–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Vis JB, Hendrikse J, Bhogal A, et al. Age-related changes in brain hemodynamics: a calibrated MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 2015; 36: 3973–3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crosby A, Robbins PA. Variability in end-tidal PCO2 and blood gas values in humans. Exp Physiol 2003; 88: 603–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yunoki T, Horiuchi M, Yano T. Kinetics of excess CO2 output during and after intensive exercise. Jpn J Physiol 1999; 49: 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herholz K, Buskies W, Rist M, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow in man at rest and during exercise. J Neurol 1987; 234: 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patik JC, Tucker WJ, Curtis BM, et al. Fast-food meal reduces peripheral artery endothelial function but not cerebral vascular hypercapnic reactivity in healthy young men. Physiol Rep 2018; 6: e13867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zwillich CW, Sahn SA, Weil JV. Effects of hypermetabolism on ventilation and chemosensitivity. J Clin Invest 1977; 60: 900–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rostrup E, Law I, Blinkenberg M, et al. Regional differences in the CBF and BOLD responses to hypercapnia: a combined PET and fMRI study. Neuroimage 2000; 11: 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henriksen OM, Kruuse C, Olesen J, et al. Sources of variability of resting cerebral blood flow in healthy subjects: a study using 133Xe SPECT measurements. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 787–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shirahata N, Henriksen L, Vorstrup S, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow assessed by 133Xe inhalation and emission tomography: normal values. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1985; 9: 861–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thesen T, Leontiev O, Song T, et al. Depression of cortical activity in humans by mild hypercapnia. Hum Brain Mapp 2012; 33: 715–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zappe AC, Uludag K, Oeltermann A, et al. The influence of moderate hypercapnia on neural activity in the anesthetized nonhuman primate. Cereb Cortex 2008; 18: 2666–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kandel ER, Jessell TM, Schwartz JH, et al. Principles of neural science., 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clifton GL, Haden HT, Taylor JR, et al. Cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity after carotid artery occlusion. J Neurosurg 1988; 69: 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Vis JB, Petersen ET, Bhogal A, et al. Calibrated MRI to evaluate cerebral hemodynamics in patients with an internal carotid artery occlusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015; 35: 1015–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Vis JB, Hou X, Liu P, et al. Influence of end-tidal CO2 on cerebrovascular reactivity mapping: within-subject and across-subject effects. In: Proceedings of the 26th international society of magnetic resonance in medicine annual meeting Paris, France, 16–21 June 2018, p.0053. Berkeley, CA: International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.

- 64.Leenders KL, Perani D, Lammertsma AA, et al. Cerebral blood flow, blood volume and oxygen utilization. Normal values and effect of age. Brain 1990; 113(Pt 1): 27–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fujii K, Sadoshima S, Okada Y, et al. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism in normotensive and hypertensive patients with transient neurologic deficits. Stroke 1990; 21: 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakane H, Ibayashi S, Fujii K, et al. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism in hypertensive patients with cerebral infarction. Angiology 1995; 46: 801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dai W, Lopez OL, Carmichael OT, et al. Abnormal regional cerebral blood flow in cognitively normal elderly subjects with hypertension. Stroke 2008; 39: 349–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dhokalia A, Parsons DJ, Anderson DE. Resting end-tidal CO2 association with age, gender, and personality. Psychosom Med 1998; 60: 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hartmann SE, Pialoux V, Leigh R, et al. Decreased cerebrovascular response to CO2 in post-menopausal females with COPD: role of oxidative stress. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: 1354–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bernardi L, Casucci G, Haider T, et al. Autonomic and cerebrovascular abnormalities in mild COPD are worsened by chronic smoking. Eur Respir J 2008; 32: 1458–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van de Ven MJ, Colier WN, Van der Sluijs MC, et al. Ventilatory and cerebrovascular responses in normocapnic and hypercapnic COPD patients. Eur Respir J 2001; 18: 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Donahue MJ, Ayad M, Moore R, et al. Relationships between hypercarbic reactivity, cerebral blood flow, and arterial circulation times in patients with moyamoya disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 38: 1129–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation 2005; 111: 697–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Netea RT, Lenders JW, Smits P, et al. Influence of body and arm position on blood pressure readings: an overview. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Netea RT, Smits P, Lenders JW, et al. Does it matter whether blood pressure measurements are taken with subjects sitting or supine? J Hypertens 1998; 16: 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zachariah PK, Sheps SG, Moore AG. Office blood pressures in supine, sitting, and standing positions: correlation with ambulatory blood pressures. Int J Cardiol 1990; 28: 353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jamieson MJ, Webster J, Philips S, et al. The measurement of blood pressure: sitting or supine, once or twice? J Hypertens 1990; 8: 635–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cicolini G, Pizzi C, Palma E, et al. Differences in blood pressure by body position (supine, Fowler's, and sitting) in hypertensive subjects. Am J Hypertens 2011; 24: 1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Normal variations in brain oxygen extraction fraction are partly attributed to differences in end-tidal CO2 by Dengrong Jiang, Zixuan Lin, Peiying Liu, Sandeepa Sur, Cuimei Xu, Kaisha Hazel, George Pottanat, Sevil Yasar, Paul Rosenberg, Marilyn Albert and Hanzhang Lu in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism