Abstract

Aim

Ethical competence is a crucial component for enabling good quality care but there is insufficient qualitative research on healthcare professionals' views on ethical competence. The aim of this study was to investigate healthcare professionals' views on ethical competence in a student healthcare context.

Design

A qualitative design and a hermeneutical approach were used.

Methods

The material consists of texts from interviews with healthcare professionals (N = 10) in a student healthcare context. The method was inspired by content analysis.

Results

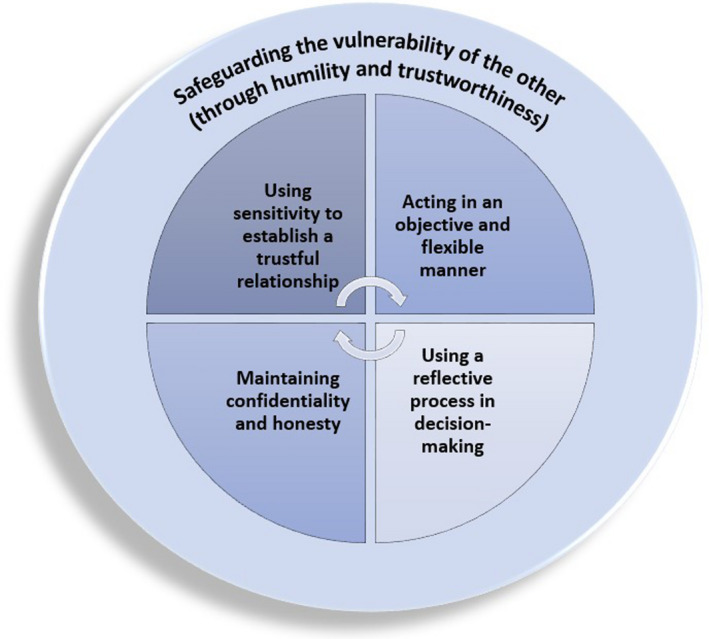

One main theme and four subthemes emerged. The main theme was as follows: safeguarding the vulnerability of the other. The subthemes were as follows: using sensitivity to establish a trustful relationship, acting in an objective and flexible manner, using a reflective process in decision‐making, and maintaining confidentiality and honesty. Future research should focus on investigating ethical competence from various perspectives in student health care, for example the student perspective or observational studies.

Keywords: competence, ethics, nurses, nursing

1. INTRODUCTION

Ethical competence is a fundamental qualification or capacity that healthcare professionals need in daily practice to identify the ethical dimensions inherent in their decision‐making. Ethical competence can help healthcare professionals find the best possible solution for patients (Kulju, Stolt, Suhonen, & Leino‐Kilpi, 2016) and is thereby an essential component of high‐quality care. Researchers have found that nurses often lack sufficient expertise in evaluating ethical matters, are not always capable of recognizing ethical issues (Atabay, Ҫangarli, & Penbek, 2015; Corley, 2002; Ulrich et al., 2010) and are not always aware of the ethical decisions they face and make (Storaker, Nåden, & Sæteren, 2017). The concept of ethical competence has still not been sufficiently researched in the healthcare context (Kangasniemi, Pakkanen, & Korhonen, 2015). To our knowledge, there is insufficient qualitative research on healthcare professionals' views on ethical competence in a student healthcare context.

2. BACKGROUND

Ethics refers to the science or study of morals, ethical principles and decision‐making skills (Thompson, Melia, & Boyd, 2006) and concerns the values and principles related to human conduct (Beauchamp & Childress, 2009). Kunyk and Austin (2012) state that ethics is an essential component of all nursing practice. According to the International Council of Nurses' (2012) Code of Ethics for Nurses, nurses have four basic responsibilities: to promote health, to prevent illness, to restore health and to alleviate suffering. In their practice, nurses should also respect human rights, which includes cultural rights, the right to life, choice and dignity and nurses should treat patients with respect. Professional ethics refers to the moral norms and regulations shared by an occupational group (Beauchamp & Childress, 2009), which are also linked to an organization and used to address morally unclear circumstances (Frankel, 1989). Professional ethics guide nurses' everyday work (Poikkeus, Numminen, Suhonen, & Leino‐Kilpi, 2014) and are used to help prevent ethical mistreatment (Brecher, 2014). Those seeking help in a student healthcare context can be considered particularly vulnerable, especially emerging adults who are still developing own identities. Little is known about ethical competence in the student healthcare context, especially healthcare professionals' views on ethical competence and how ethical mistreatment can be inhibited.

In health care, ethical competence is a fundamental but complex concept (De Casterlé, Izumi, Godfrey, & Denhaerynck, 2008). Park and Peterson (2006) find that ethical competence is a broad and universal competence that guides other competencies but is not noticeably distinct. Kulju et al. (2016) maintain that ethical competence can be considered an umbrella concept in a healthcare context, because it is indirectly part of all competence. In the European Qualifications Framework, the European Commission (2010) defines ethical competence as a meta‐competence; it is an internal component of knowledge, skills and competence and essential for the development of responsibility and autonomy. In the World Health Organization's Global Competency Model (2012), several core qualities linked to ethical competence are listed: active listening, understanding, responsibility, collegiality, identifying conflicts, respect, confidentiality and personal values.

Highly prioritized in healthcare, ethical competence takes the form of ethical committees and ethical rounds in healthcare systems (Chao, Chang, Yang, & Clark, 2017). As a concept, ethical competence encompasses human growth, skills and knowledge, education and the evaluation of professionals (Kulju et al., 2016). In their integrative review, Kangasniemi et al. (2015) discern a link between professional ethics and clinical competence (Chadwick & Thompson, 2000; Dobrowolska, Wrońska, Fidecki, & Wysonkinski, 2007; Liaschenko & Peter, 2004; Vanaki & Memarian, 2009). Others maintain that ethical competence is a part of professional competence (Cheetham & Chivers, 1996; Paganini & Yoshikawa Egry, 2011). Ethical competence is acquired through experience and role models (Höglund, Eriksson, & Helgesson, 2010) and is based on virtues, principles and critical reflection (Eriksson, Helgesson, & Höglund, 2007). It is also considered a state of being, which includes one's personal characteristics, one's doing (actions based on judgements in accordance with principles) and, for example one's familiarity with the law (Eriksson et al., 2007). Ethical competence entails the ability to reflect on and use new patterns of actions with patients, that is critically evaluate the best possible solution from the options available in an ethically challenging situation (Bolmsjö, Sandman, & Andersson, 2006; Jomsri, Kunaviktikul, Ketefian, & Chaowalit, 2005; Kavathatzopoulos, 2003).

In their daily work, healthcare professionals must balance between the external pragmatic values espoused in effective, productive and economic practices and the values espoused in individualized high‐quality health care (Goethals, Gastmans, & de Casterlé, 2010; Palese, Vianelli, De Maino, & Bortoluzzi, 2012). Nurses must navigate ethical situations on a daily basis, which requires the integration of both individual and professional perspectives. When providing quality care, nurses encounter ethical challenges related to the patients themselves (Ulrich et al., 2010) as well as disease and treatment (Palese et al., 2012; Winterstein, 2012).

Ethical competence is often described as an experience acquired through the combination of knowledge and practice. For example, Park and Peterson (2006) find that individuals who do not possess strength of character might not “do what is correct” or “take correct action” in a given situation. Kulju et al. (2016) also maintain that ethical competence concerns character strength, ethical awareness, moral judgement skills and the willingness to do good. The prerequisites for ethical competence are professional virtues, experience of professionalism, human communication, ethical knowledge and a supportive organizational environment (Robichaux, 2016).

As concerns the formation or development of ethical competence, Kavathatzopoulos (2003) underscores the importance of theoretical ethical knowledge. Paganini and Yoshikawa Egry (2011) also maintain that ethical knowledge is needed to develop professional ethical competence. Still, Kävlemark Sporrong, Arnetz, Hansson, Westerholm, and Höglund (2007) argue that those who merely possess theoretical ethical knowledge do not automatically possess actual ethical competence. Lechasseur, Caux, Dollé, and Legault (2018) define ethical knowledge as the knowledge constructed from a mix of philosophical, theoretical and practical knowledge, where pertinent contexts and individuals are taken into consideration. They also maintain that as part of the process whereby ethical competence is developed, these different types of knowledge are brought together through ethical reflection.

Some researchers argue that even though ethical reflection and ethical decision‐making seem to be intertwined or closely related, the concepts are dissimilar (Lechasseur et al., 2018). Regarding ethical reflection, some researchers find that ethical sensitivity as a part of ethical competence can in the healthcare context be considered to be interconnected with own moral values through reflection, i.e., a nurse’s ability to detect ethical problems and tensions in relation to others and evaluate ethical aspects (Lechasseur et al., 2018; Lützen, Dahlqvist, Eriksson & Norberg, 2006). Monteverde (2014) also maintains that professionals' implementation of ethics in the healthcare context requires ethical reflection. Ethical decision‐making can be considered to be linked to ethical competence that is based on ethical sensitivity (Han, Kim, Kim, & Ahn, 2010). Ethical decision‐making is the intentional process through which nurses consider different actions in relation to outcomes for a particular situation, thereafter deciding the best course of action in accordance with ethical action (Lechasseur et al., 2018). Ethical action is the outcome of reflection, analysis and judgement (Paganini & Yoshikawa Egry, 2011).

Building on Rest's (1994) model of moral development, Baerøe and Norheim (2011) maintain that strengthening moral sensitivity, moral judgement, moral motivation and moral character can positively influence an individual's ethical competence. Bolmsjö et al. (2006) and Nordström and Wangmo (2018) state that ethical competence is needed in health care to prevent mistreatment and unethical practices. Moreover, when healthcare professionals' ethical competence is developed, nurses' advocacy skills also develop (Lechasseur et al., 2018).

In their integrative review, Kangasniemi et al. (2015) find that a research gap exists between conceptual and philosophical research regarding whether professional ethics can help expand patients' understanding of own health situation (Brecher, 2014; Dobrowolska et al., 2007; González‐de Paz, Kostov, Sisó‐Almirall, & Zalbalegui‐Yárnoz, 2012). Poikkeus et al. (2014) also maintain that the way where ethical competence is defined is insufficient, which is in line with Goethals et al. (2010), who find a lack of clarity regarding the concept. Despite extensive research on the patient, healthcare professionals' ethical competence is still limited (Koskenvuori, Stolt, Suhonen, & Leino‐Kilpi, 2019) and knowledge of professional ethics in practice is lacking (González‐de Paz et al., 2012; Kangasniemi et al., 2015; Liaschenko & Peter, 2004).

2.1. Aim

The aim of this study was to investigate healthcare professionals' views on ethical competence in a student healthcare context.

2.2. Research question

What is healthcare professionals' views on ethical competence in a student healthcare context?

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Design and method

A hermeneutical approach inspired the qualitative design of the study (Gadamer, 1999) and content analysis the study method (Kyngäs & Vanhanen, 1999). The data are comprised of texts from interviews with healthcare professionals working in a student healthcare context.

Individual, semi‐structured interviews of 10 healthcare professionals aged between 26–61 about their views on ethical competence in a student healthcare context were undertaken. The participants included nine women and one man: eight were public health nurses, one psychiatric nurse and one therapist/psychologist. The participants had similar (middle‐class) socioeconomic backgrounds and were recruited in cooperation with the leading head nurse for a public healthcare organization in an urban area of Finland. The leading head nurse recommended suitable health professionals, who were then sent a written invitation to participate in the study. The researchers contacted these professionals by phone and gave a detailed oral presentation of the study and schedule interviews for those interested in participating. The most experienced researcher developed the interview guide. The interview guide themes included, for example how the participants' define ethical competence, their thoughts on ethical competence, examples of how they use ethical competence in daily practice and specific ethically challenging situations they have experienced in practice alongside deeper reflection on and an illumination of their actions as related to these experiences.

The participants' work experience in student health care varied between 1–27 years and encompassed students and adolescents. Four participants had over 20 years of work experience in health care. The semi‐structured interviews lasted between 30–60 min and were conducted in the participants' workplace settings. The interviews were later transcribed.

3.1.2. Analysis

The interpretation of the data in the analysis was guided by Gadamer's hermeneutics (1999). When reading the text material from the interviews, the researchers approached the material with openness and diligence. The researchers read the data material several times, highlighted keywords and sentences and added their reflections on particular text phrases. The interpretation included a repetitive process of moving back and forth between the parts of the text and the whole; even when the reading shifted between interpretation and understanding, an understanding of the whole was sought. During this process, the researchers allowed the reading to challenge their pre‐understanding, while simultaneously preventing it from steering the process of interpretation. As a last step, the researchers invited their pre‐understanding into the scientific discourse when forming the main theme and subthemes. See Table 1 for an example of the data analysis.

TABLE 1.

Example of the analysis

| Meaningful unit | Code | Subtheme | Main theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| I start to look at the person, facial expression, gestures etc. … and do they have the courage to look at you or…and then I carefully start to ask questions to find out what is going on. That is, I wait a little first before I begin to talk. |

I start to look at the person, facial expressions etc. I carefully start to ask questions… I wait a little first before I begin to talk… |

Using sensitivity to establish a trustful relationship |

Safeguarding the vulnerability of the other An example of a quotation categorized under the main theme: “I invest a lot in the first appointment… to provide a sense of security, so that they can trust me and [know] that I know what I am doing and have experience… Ethical competence also has to do with the students being allowed to choose, and to begin by offering their view on their situation, even if I know what I know and have heard what I have heard… and I always try to show that you are important, you can sit here as long as you like. Ethics is also that I try to convey all my knowledge to the patient so that he or she will feel better.” |

3.1.3. Ethics

The guidelines for ethical research delineated by the Finnish National Advisory Board on Research Ethics (2012) have been followed throughout the course of this research. Ethical approval was sought for the study and permission to conduct the data was given by the healthcare organization. The researchers contacted each participant by telephone and provided information about the study purpose, voluntary participation, confidentiality and the right to withdraw from the study at any time. The researchers also sought informed consent from the participants regarding participation and the storage of data. The participants were even informed both orally and in writing about the intention to publish the study results.

4. RESULTS

One main theme and four subthemes were seen. The main theme was as follows: safeguarding the vulnerability of the other. The subthemes were as follows: using sensitivity to establish a trustful relationship, acting in an objective and flexible manner, using a reflective process in decision‐making, and maintaining confidentiality and honesty (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study findings: Ethical competence in a healthcare context

4.1. Safeguarding the vulnerability of the other

We found that ethical competence entails safeguarding the vulnerability of the other, which emerged as the main theme. We even discerned that humility and trustworthiness, interwoven into all of the subthemes, formed a particularly critical component of ethical competence in the student healthcare context seen here. Acting with humility and trustworthiness is a fundamental component of ethical competence, because doing so helps healthcare professionals create a sense of security, maintain objectivity and demonstrate that the other is being taken seriously. It also enables healthcare professionals to reveal their ethical stance through both verbal and non‐verbal actions. The participants emphasized that healthcare professionals must “see” the patient and respect the patient's concerns: “I try to create a peaceful and confidential situation with my voice and [body language] when students come here. That kind of thing” (P4). The participants noted that sometimes students wait a long time before having the courage to make an appointment and talk about their concerns. According to the participants, it is important that healthcare professionals are not judgemental and instead create a sense of security. We saw that such safeguarding of the patient's vulnerability can be realized when healthcare professionals act in a kind manner and allowing the patient to freely express him/herself:

I invest a lot in the first appointment… to provide a sense of security, so that they can trust me and [know] that I know what I am doing and have experience… Ethical competence also has to do with the students being allowed to choose and to begin by offering their view on their situation, even if I know what I know and have heard what I have heard… and I always try to show that you are important, you can sit here as long as you like. (P3)

Also interwoven into each of the subthemes was that ethical competence, which includes showing respect for and treating everyone equally, enables good quality care. We found that ethical competence formed the basis that enabled care quality and ethics and that both ethical competence and ethics may assist healthcare professionals in their decision‐making in practice, seen here when the participants focus on their ethical inner values. This is in line with Kangasniemi et al. (2015), who maintain that professional ethics is founded on professional (Chadwick & Thompson, 2000; Dobrowolska et al., 2007; Liaschenko & Peter, 2004; Memarian, Salsali, Vanaki, Ahmadi, & Hajizadeh, 2007) and personal values (Rassin, 2008). In this study, the participants noted that ethical competence entailed treating each patient equally, regardless of own preconceptions or the patient's background. We furthermore discerned that the participants perceived that healthcare professionals should be aware of own values, as this was the foundation on which they derived their ethics and which allowed them the “strength” to treat all individuals equally: “First of all, you will need to stop and think about your values such as what kind of impact or help you want to give to the patients, what kind of nurse you want to be, how others see you and so on” (P4). The participants revealed that ethical competence included knowing the good and bad aspects of things and that the basis for equal (and thus good quality) care was understanding that each patient has his/her own value. “It's about knowing about both the good and bad aspects of things and that when you make decisions being able to compare these with your own values” (P4). The participants considered ethical competence to be a fundamental component of professional competency and therefore essential to the enabling of good quality care. The participants stated that their work included to protect life, prevent disease and promote health. They even noted that ethical competence is important in the workplace and during inter‐professional interaction. They described ethical competence as both a learned skill and something inherent that cannot be learned, but noted that experience facilitates ethical competence; the more experience one has the easier it is to provide ethical care. The participants even maintained that doing something “from the heart” as a healthcare professional enables ethics to emerge and fosters ethical action. This was seen as treating the patient in a holistic manner, that is taking the whole person into account when determining care or treatment, showing commitment to the patient and demonstrating trustworthiness:

For me there is no question whether we need ethical competence or not, because if we do not have it, we cannot give good care. I do not even think about doing it, because I [provide care] from the heart. …Also if you do it from the heart ethics comes along with that… I take the whole person into consideration when I evaluate what kind of care or treatment he/she needs and then also show the person that I am committed to him/her. I do what I promised to do, that's important. (P7)

4.2. Using sensitivity to establish a trustful relationship

In this theme, we saw that to establish common understanding, the participants used sensitivity to “get on the same wavelength” as the patient. This also helped create a trustful healthcare professional–patient relationship, which we interpret as safeguarding the patient's dignity. The participants noted that establishing a trustful relationship required time and that the length of time needed depended on the individual patient. They maintained that it was highly important that they as healthcare professionals calmly listened and used sensitivity to understand the patient's point of view without judgement or assumptions:

You try to be kind when meeting and receiving patients. … I show them where they can hang their coats and where to sit when they arrive. And I usually ask ‘You have a concern, what is it?’. And I allow them to speak, I don't say anything else. I believe it's important that they get to start.... (P2)

The participants maintained that a trustful relationship was built by spending a great deal of time with each patient, which allowed them as healthcare professionals to begin to understand the patient and eventually reach common understanding:

You have to be on the same wavelength to reach them… you can't be haughty… they don't open up if you come there like some prophet … I have a more listening and humility‐based approach… because I want them to come back…. (P1)

The participants perceived that discussion was important to the establishment of common understanding, which in turn facilitated a joint effort to find the best possible solution for the patient. One participant revealed that occasionally a student has waited so long before making an appointment that he/she merely sinks into the chair and says nothing:

I start to look at the person, facial expression, gestures etc. … and do they have the courage to look at you or…and then I carefully start to ask questions to find out what is going on. That is, I wait a little first before I begin to talk. (P2)

4.3. Acting in an objective and flexible manner

In this theme, we found that acting in an objective and flexible manner was also a central component in good and ethical care. The participants maintained they found it important to take each patient's concerns seriously and treat each patient with dignity. To treat each patient in an equal manner, the participants revealed that it was important to act in an as objective a manner as possible, noting that all patients have the right to the same level of care. The participants also maintained that it was essential to accept the patient in front of them as a unique human being, that is to “see” the other: “It means to be able to accept their ways and reasons why they act the way they do. Sometimes it is against your own principles and such… but you can learn to understand [the other]…” (P1). The participants perceived that common understanding could be achieved through communication. As a healthcare professional, this could entail showing an interest in the patient, asking the patient questions, being flexible and understanding and navigating differences of opinion:

Ethical competence means to treat everyone in a correct way. Yes, there is one thing to think about, which is what is my opinion and what is the student's opinion and can we meet each other… I have to listen to the [student's opinion] at first… and then [my opinion] and then it is about the combination of that, that you like meet in the middle of the opinions. (P6)

The participants noted that work experience could help them manage own feelings and act in an objective manner. They stated that workplace guidance was essential, because this allowed them the opportunity to reflect on and freely express their feelings, when maintaining an objective manner they cannot show disgust and so on in front of a patient:

You have to put your own feelings aside… To have the support from the team and group workplace guidance and to show that you have the right to negative feelings…To realize, to yourself, that you don't have to like this person, who may have hurt [another person] very deeply. You can think that you are only human yourself and have the right to feel this way, but you don't have the right to say how you feel…. (P3)

The participants stated that to get to know a patient, including his/her opinions, it was important to remember to be question‐oriented. They additionally revealed that reading through the patient's records/file facilitated them in showing interest in helping the patient with his/her situation. We find that this allowed the participants to act in a flexible manner, that is it helped them navigate the patient's opinions and reach common understanding:

I show an interest by having the background information at hand and manage to establish reciprocal communication… that can be attained by asking… so that we can talk with each other… they should be allowed to be themselves… you should be honest with them. It should be easy to reach student healthcare services and feel good to be there…. (P2)

4.4. Using a reflective process in decision‐making

In this theme, we found that the participants used various strategies, for example relying on previous experience (including knowledge of what is right or wrong) or asking follow‐up questions, to facilitate their decision‐making process and that the overall decision‐making process can be considered a reflective process. The participants revealed that even though theoretical knowledge is the basis of all ethical knowledge, such as right versus wrong, they often decided on a specific course of action “in the moment.” They perceived that previous professional experience of ethically difficult situations gave them the tools they needed to make ethical decisions in the present, which in turn allowed them to safeguard the patient's dignity in a given situation.

The participants revealed that showing humility during the decision‐making process was important: “Ethical competence requires theory and knowing what generally is right or wrong… but then you have to decide in the moment, according to experience, what is the ethically right thing to do” (P3). The participants perceived that the purpose of student healthcare services was to enable students to make better health and life choices. They noted that this was not always a matter of providing the correct answer but was instead about listening to the patient and showing humility. The participants emphasized that showing humility includes acting in a non‐judgemental manner and not assigning blame, even if a patient chooses to do something detrimental to his/her health. They instead stressed that the patient's right to self‐determination should be respected and that their role as healthcare professionals included helping the patient find the best possible solution for the given situation. They furthermore related that during each visit they perceived that they should show humility because each visit is unique:

To be ethically correct you should treat all visits and people who arrive as if it were the first time you meet that person. It takes a certain amount of humility. … to be ethical in front of the person, who says that I don't know anything about this person when he or she arrives… Humility is a central part of the ethical approach. …especially if we are talking about vulnerable people… You should be very sensitive then. Ethics becomes especially important in such a situation. (P2)

The participants even revealed that when seeking to understand the patient it is important to ask questions and reflect on what the patient is trying to say. One participant stated that ethical competence was something that evolves from work experience: “You need an ethical attitude because otherwise you do not understand what they are trying to tell you… at the beginning I did not understand this, but now I ask more questions…” (P1). The participants maintained that to improve ethical competence it is important to realize that no healthcare professional is perfect nor knows everything. There is always room for improvement, but this requires motivation, education and the willingness to develop. The participants perceived that there was always room for improvement regarding their ethical competence, noting that they could show their patients more respect and compassion or even give better explanations. They mentioned that there were risks associated with solely relying on past professional experience, which can be equated to an inability to see things in an objective or impartial manner: “OK, this is such a person with such a problem, then we do this!” (P9). One participant even emphasized that there were risks associated with healthcare professionals misjudging own capabilities and attempting to do more than they should:

I would define it as being truthful to what you know and what you're able to do and work in that context. And if you are not capable of doing something, don't push it because it's not about how much you know or your ego, but the important thing is to help the patient… in this case. (P5)

4.5. Maintaining confidentiality and honesty

In this theme, we saw that the participants perceived confidentiality and honesty to be central to the establishment of a trustful healthcare professional–patient relationship. The participants noted that their patients could be worried about confidentiality, that is that instructors or peers would learn details about a private health matter and that this in turn would have an impact on the student's studies. We saw that the participants perceived that the safeguarding of a student's dignity could sometimes be encapsulated in a single, critical issue:

One of the things I have to tell them is that the things they are going to tell me are not something that I am going to tell the instructors. It's nothing that I will tell the school and that it stays at student healthcare. (P6)

The participants stressed that assuring patients of confidentiality can be especially important in ethically complex situations:

I have had cases from the simplest things to the most complex… I have couples where you cannot tell the other person what they told you during their private sessions even though they have the right or are entitled to know. So it is this type of ethics… It's important to know when and at what point you need to keep it confidential. (P5)

We discerned that it was important for healthcare professionals to accept the unique person before them, because this comprises the ethical foundation on which everything else is built. We saw that this included healthcare professionals “entering” the patient's world in an attempt to understand the unique patient. The participants maintained that it was important to allocate a sufficient amount of time for appointments, especially first appointments, because doing so demonstrated that the patient was taken into consideration. They also revealed that trust could be gradually increased when they were tangibly able to help a patient. They furthermore noted that being honest was essential in the ethically caring relationship:

I [schedule] enough time for the first appointment because I think the first time when they come here it is important that they feel that I listen to them. …I try to give them as much space as possible and then I make sure that if I promise them something and …that I also make sure I do it. (P7)

The participants revealed that regarding ethically difficult or challenging situations, support from colleagues was important; being able to discuss with other professionals and or even refer a case to another professional was critical.

5. DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to investigate healthcare professionals' views on ethical competence in a student healthcare context. We found that ethical competence entails safeguarding the vulnerability of the other and that humility and trustworthiness formed a particularly critical component. Interwoven into all of the subthemes were both humility and trustworthiness and ethical competence in the form of showing respect for and treating everyone equally, which enables good quality care. Ethical competence in the form of showing respect for and treating everyone equally enables good quality care, because ethical competence facilitates ethical decision‐making in practice. This can be compared with Jomsri et al. (2005), who find that ethical competence includes the ability to identify value conflicts and ethical dimensions. They also note that logical reasoning supports an individual's ability to choose between values.

Ethical competence in a student healthcare context was also seen to be related to using sensitivity to establish a trustful relationship, acting in an objective and flexible manner, using a reflective process in decision‐making and maintaining confidentiality and honesty. The subthemes were seen to be closely related to one another, which is in line with previous research where researchers have found that ethical competence consists of diverse and multipart components (De Araujo Sartorio & Pavone Zoboli, 2010; Hickman & Wocial, 2013; Vynckier, Gastmans, Cannaerts, & de Casterlé, 2015) that are strongly connected to one other (Trobec & Starcic, 2014). Poikkeus et al. (2014) and Lechasseur et al. (2018) maintain that ethical competence consists of ethical sensitivity, ethical knowledge, ethical reflection, ethical decision‐making, ethical action and ethical behaviour, which corresponds to our findings.

We furthermore saw that ethical competence entails using sensitivity to establish a common understanding with the patient, to realize a trustful healthcare professional–patient relationship. Listening calmly and time emerged as important factors that enable healthcare professionals to “get on the same wavelength” as a patient. This in turn facilitated the establishment of a trustful relationship, which also included using discussion to get to know the patient, his/her values and way of life—which can be considered a basis for enabling ethical competence in praxis. In this study, to be calm enabled healthcare professionals to flexibly engage in discussions in accordance with the patient's pace and needs, which can be compared with active listening. The World Health Organization (2012) lists the following core qualities as being linked to ethical competence: active listening, understanding and respecting others. Ma (2006) likewise relates ethical competence to altruistic performance in practice. In this study, the participants sought to demonstrate skill and professionalism without being haughty and used facial expressions and gestures to establish a common understanding when seeking the best possible solution for a patient. Through such, healthcare professionals indicate that the patient is the most important person in the room, which provides a sense of security. Healthcare professionals should remember that some students might be truly vulnerable and safeguarding the vulnerability of the other was seen here to be fundamental to ethical competence. This can be compared with ethical sensitivity and Lützen et al. (2006) and Lechasseur et al. (2018) also stress that ethical sensitivity is a crucial part of ethical competence, seen in a nurse's ability to detect ethical problems and tensions in relation to others. This is in line with Torralba (2002), who finds that vulnerable individuals in care need nurses who possess the inner virtues of responsibility and solidarity. Torralba moreover emphasizes that the ethical basis for caring lies in seeing the other and the other's vulnerability. He argues that individualized care that includes emotional management, sensitivity, personal involvement, confidentiality, excellent communicative skills and psychological knowledge is needed and that such should be combined with moral character, which he refers to as a professional ethos (2002). Ethical competence even entails virtues such as empathy (Dupoux & Jacob, 2007), because ethical competence requires virtues to be developed within an individual (Begley, 2005; Eriksson et al., 2007).

In this study, we saw that healthcare professionals should act in an objective and flexible manner, to treat each patient in an equal manner. This corresponds with Torralba (2002), who states that for a professional ethos to evolve, an individual must first establish a personal ethos through the creation of diverse virtues, which then permeate the professional ethos. Other virtues that nurses can develop include, according to Torralba (2002), compassion, competence, confidence and conscience. In this study, we even found that acting in an objective and flexible manner was a central component in good and ethical care and thus ethical competence. Healthcare professionals should in an objective manner manage and affirm different opinions and be flexible regarding care actions, which should be tailored to each student. Healthcare professionals should take patients' concerns seriously and treat each patient with dignity. Healthcare professionals can show interest in patients by asking questions.

We also saw that using a reflective process in decision‐making can be beneficial. This means, for example using experience‐based skills and reflecting on previous, similar situations to be able to make decisions about the present situation and patient (e.g. Bolmsjö et al., 2006; Jomsri et al., 2005; Kavathatzopoulos, 2003).

We argue that regular reflective meetings, where healthcare professionals discuss ethical issues, can enhance staff's ethical competence in a student healthcare context. We contend that further enhancement of ethical competence will facilitate healthcare professionals in “being open” with each student and help them to demonstrate humility: the realization that each situation requires reflection and being open to the patient's voice and perspective. This can be compared with Lechasseur et al. (2018), who maintain that ethical competence consists of ethical reasoning, ethical action and ethical behaviour. They further note that through a linking of these components, an understanding of how ethical competence evolves and is advanced by healthcare professionals can occur (Lechasseur et al., 2018). Park and Peterson (2006) find that character strength is needed to take the right action. Similarly, Kulju et al. (2016) relate ethical competence to character strength, ethical awareness, moral judgement skills and willingness to do good. We found that healthcare professionals can learn and advance their ethical approach through experience.

We even found that ethical competence entails maintaining confidentiality and honesty. Here, we saw that confidentiality and honesty are central to the establishment of a trustful healthcare professional–patient relationship. This is in line with Höglund et al. (2010), who consider honesty and loyalty toward patients to be important elements of ethical competence. Corley (2002) and Goethals et al. (2010) even define ethical competence as an ethical action that demands ethical knowledge of legislation (De Schrijver & Maesschalck, 2013; Iltanen, Leino‐Kilpi, Puukka, & Suhonen, 2012) and knowledge of values, principles and ethical codes (Schank & Weis, 2001).

5.1. Limitations

One limitation might be the study recruitment process. The head nurse was familiar with the participants she recommended, which can entail a risk. However, we found that such familiarity led to a selection of individuals suitable for the study purpose and with the potential to provide trustful data, as seen in the rich and vivid data that emerged. Another limitation might be that several researchers conducted the interviews, but the researcher most experienced with interviews conducted most. One strength is that ten participants freely expressed their views on ethical competence in their daily practice. Another is that the researchers together discussed the questions in the interview guide to ensure reliability and even both conducted the data analysis and discussed the final themes created. This study therefore can be considered to reliably represent healthcare professionals' views on ethical competence in a student healthcare context. The findings can also be considered transferable to other healthcare and nursing contexts, particularly those with extra vulnerable patient groups, for example paediatric or psychiatric health care. The findings might have been different with more male participants or more healthcare professional variation, which may limit the generalizability and comparability of the findings. Nevertheless, the findings seen here can potentially help other healthcare professionals better understand ethical competence, which makes this study defensible. In the future, it could be useful to conduct focus group interviews with students or observational studies.

6. CONCLUSION

We saw that safeguarding the vulnerability of the other is a particularly important component of ethical competence in a student healthcare context. Further essential components of ethical competence include using sensitivity to establish a trustful relationship, acting in an objective and flexible manner, using a reflective process to make decisions and maintaining confidentiality and honesty. Further research should include other healthcare professionals, for example midwives or healthcare students.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no sources of conflicts.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jessica Hemberg: Study conception and design, data analysis, discussion, and drafted the manuscript at all stages. Håkan Hemberg: Study conception, data analysis, discussion and provided critical reflections.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants in this study as well as Caroline Anna Pantling, Soko Sakamoto, Frida Kristjankroon, Kazuya Kanata, Kyoko Kobayashi, Leonie Brose and Radhika Velaz López who participated in this research project with data collection.

Hemberg J, Hemberg H. Ethical competence in a profession: Healthcare professionals' views. Nursing Open. 2020;7:1249–1259. 10.1002/nop2.501

REFERENCES

- Atabay, G. , Ҫangarli, B. G. , & Penbek, Ş. (2015). Impact of ethical climate on moral distress revisited: Multidimensional view. Nursing Ethics, 22, 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baerøe, K. , & Norheim, O. F. (2011). Mapping out structural features in clinical care calling for ethical sensitivity: A theoretical approach to promote ethical competence in healthcare personnel and clinical ethical support services (CESS). Bioethics, 25, 394–402. 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2011.01909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, T. L. , & Childress, J. F. (2009). Principles of biomedical ethics (6th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, A. M. (2005). Practicing virtue: A challenge to the view that a virtue centered approach to ethics lacks practical content. Nursing Ethics, 12, 622–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolmsjö, I. A. , Sandman, L. , & Andersson, E. (2006). Everyday ethics in the care of elderly people. Nursing Ethics, 13, 249–263. 10.1191/0969733006ne875oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecher, B. (2014). What is professional ethics? Nursing Ethics, 21(2), 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, R. , & Thompson, A. (2000). Professional ethics and labor disputes: Medicine and nursing in the United Kingdom. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 9, 483–497. 10.1017/S0963180100904067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao, S. Y. , Chang, Y. C. , Yang, S. C. , & Clark, M. J. (2017). Development, implementation and effects of an integrated web‐based teaching model in a nursing ethics course. Nurse Education Today, 55, 31–37. 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham, G. , & Chivers, G. (1996). Towards a holistic model of professional competence. Journal of European Industrial Training, 20, 20–30. 10.1108/03090599610119692 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corley, M. C. (2002). Nurse moral distress: A proposed theory and research agenda. Nursing Ethics, 9, 636–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Araujo Sartorio, N. , & Pavone Zoboli, E. L. (2010). Images of a “good nurse” presented by teaching staff. Nursing Ethics, 17, 687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Casterlé, B. D. , Izumi, S. , Godfrey, N. S. , & Denhaerynck, K. (2008). Nurses' responses to ethical dilemmas in nursing practice: Meta‐analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68, 540–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schrijver, A. , & Maesschalck, J. (2013). A new definition and conceptualization of ethical competence In: Cooper T., & Fenzel D. (Eds.) Achieving ethical competence for public service leadership (pp. 29–50). New York, NY: ME Sharpe Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolska, B. , Wrońska, I. , Fidecki, W. , & Wysonkinski, M. (2007). Moral obligations of nurses based on the ICN, UK, Irish and Polish codes of ethics for nurses. Nursing Ethics, 14, 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupoux, E. , & Jacob, P. (2007). Universal moral grammar: A critical appraisal. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, S. , Helgesson, G. , & Höglund, A. T. (2007). Being, Doing and Knowing: Developing Ethical Competence in Healthcare. Journal of Academic Ethics, 5, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . (2010). Explaining the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/ploteus/sites/eac‐eqf/files/brochexp_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Finnish National Advisory Board on Research Ethics . (2010) Responsible conduct of research and produces for handling allegations of misconduct in Finland – RCS guidelines. Helsinki, Finland: Retrieved from http://www.tenk.fi/sites/tenk.fi/files/HTK_ohje_2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, M. S. (1989). Professional codes: Why, how and with what impact? Journal of Business Ethics, 8, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, H.‐G. (1999). Truth and method. New York, NY: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Goethals, S. , Gastmans, C. , & de Casterlé, B. D. (2010). Nurses' ethical reasoning and behavior: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47, 635–650. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González‐de Paz, L. , Kostov, B. , Sisó‐Almirall, A. , & Zalbalegui‐Yárnoz, A. (2012). A Rasch analysis of nurses' ethical sensitivity to the norms of the code of conduct. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2747–2760. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04137.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.‐S. , Kim, J. , Kim, Y.‐S. , & Ahn, S. (2010). Validation of a Korean version of the Moral Sensitivity Questionnaire. Nursing Ethics, 17, 99–105. 10.1177/0969733009349993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, S. E. , & Wocial, L. D. (2013). Team‐based learning and ethics education in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education, 52, 696–700. 10.3928/01484834-20131121-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höglund, A. T. , Eriksson, S. , & Helgesson, G. (2010). The role of guidelines in ethical competence‐building: Perceptions among research nurses and physicians. Clinical Ethics, 5, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Iltanen, S. , Leino‐Kilpi, H. , Puukka, P. , & Suhonen, R. (2012). Knowledge about patients' rights among professionals in public healthcare in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 26, 436–448. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00945.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Nurses (ICN) . (2012). Retrieved from https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline‐files/2012_ICN_Codeofethicsfornurses_eng.pdf

- Jomsri, P. , Kunaviktikul, W. , Ketefian, S. , & Chaowalit, A. (2005). Moral competence in nursing practice. Nursing Ethics, 12, 582–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangasniemi, M. , Pakkanen, P. , & Korhonen, A. (2015). Professional ethics in nursing: An integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71, 1744–1757. 10.1111/jan.12619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavathatzopoulos, I. (2003). The use of information and communication technology in the training for ethical competence in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 48, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kävlemark Sporrong, S. , Arnetz, B. , Hansson, M. G. , Westerholm, P. , & Höglund, A. T. (2007). Developing ethical competence in healthcare organisations. Nursing Ethics, 14, 825–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskenvuori, J. , Stolt, M. , Suhonen, R. , & Leino‐Kilpi, H. (2019). Healthcare professionals' ethical competence: A scoping review. Nursing Open, 6, 5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulju, K. , Stolt, M. , Suhonen, R. , & Leino‐Kilpi, H. (2016). Ethical competence: A concept analysis. Nursing Ethics, 23, 401–412. 10.1077/0969733014567025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunyk, D. , & Austin, W. (2012). Nursing under the influence: A relational ethics perspective. Nursing Ethics, 19, 380–389. 10.1177/0969733011406767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyngäs, H. , & Vanhanen, L. (1999). Sisällön analyysi. [Content analysis]. Hoitotiede, 11, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lechasseur, K. , Caux, C. , Dollé, S. , & Legault, A. (2018). Ethical competence: An integrative review. Nursing Ethics, 25, 694–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaschenko, J. , & Peter, E. (2004). Nursing ethics and conceptualization of nursing: Profession, practice and work. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 46, 488–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lützen, K. , Dahlqvist, V. , Eriksson, S. , & Norberg, A. (2006). Developing the concept of moral sensitivity in healthcare practice. Nursing Ethics, 13, 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H. K. (2006). Moral competence as a positive youth development construct: Conceptual bases and implications for curriculum development. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 18, 371–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memarian, R. , Salsali, M. , Vanaki, Z. , Ahmadi, F. , & Hajizadeh, E. (2007). Professional ethics as an important factor in clinical competence in nursing. Nursing Ethics, 14, 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteverde, S. (2014). Undergraduate healthcare ethics education, moral resilience and the role of ethical theories. Nursing Ethics, 21, 385–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordström, K. , & Wangmo, T. (2018). Caring for elder patients: Mutual vulnerabilities in professional ethics. Nursing Ethics, 25, 1004–1016. 10.1177/0969733016684548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganini, M. C. , & Yoshikawa Egry, E. (2011). The ethical component of professional competence in nursing: An analysis. Nursing Ethics, 18, 571–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palese, A. , Vianelli, C. , De Maino, R. , & Bortoluzzi, G. (2012). Measures of cost containment, impact of the economical crisis and the effect perceived in nursing daily practice: An Italian crossover study. Nursing Economics, 30(86–93), 119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, N. , & Peterson, C. (2006). Moral competence and character strengths among adolescents: The development and validation of the values in action inventory of strengths for youth. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 891–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlish, C. , Brown‐Saltzman, K. , Jakel, P. , & Rounkle, A.‐M. (2012). Nurses' responses to ethical challenges in oncology practice: And ethnographic study. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 591–600. 10.1188/12.CJON.592-600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poikkeus, T. , Numminen, O. , Suhonen, R. , & Leino‐Kilpi, H. (2014). A mixed‐method systematic review: Support for ethical competence of nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70, 256–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassin, M. (2008). Nurses' professional and personal values. Nursing Ethics, 15, 614–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rest, J. R. (1994). Background: Theory and research In Rest J. R., & Narvaez D. (Eds.), Moral development in the professions: Psychology and applied ethics (pp. 1–26). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Robichaux, C. (2016). Ethical competence in nursing practice. competencies, skills and decision‐making. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Schank, M. J. , & Weis, D. (2001). Service and education share responsibility for nurses' value development. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 17, 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storaker, A. , Nåden, D. , & Sæteren, B. (2017). From painful busyness to emotional immunization: Nurses' experiences of ethical challenges. Nursing Ethics, 24, 556–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, I. E. , Melia, K. M. , & Boyd, K. M. (2006). Nurs Ethics (5th ed.). Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone. [Google Scholar]

- Torralba, F. (2002). Ética del cuidar: Fundamentos, Contextos y problemas. [Ethics of care: foundations, contexts and problems.] Madrid, p. 17.

- Trobec, I. , & Starcic, A. I. (2014). Developing nursing ethical competences online versus in the traditional classroom. Nursing Ethics, 22, 352–366. 10.1177/0969733014533241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, C. M. , Taylor, C. , Soeken, K. , O'Donnell, P. , Farrar, A. , Danis, M. , & Grady, C. (2010). Everyday ethics: Ethical issues and stress in nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66, 2510–2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanaki, Z. , & Memarian, R. (2009). Professional ethics: Beyond the clinical competency. Journal of Professional Nursing, 25, 285–291. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2009.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vynckier, T. , Gastmans, C. , Cannaerts, N. , & de Casterlé, B. D. (2015). Effectiveness of ethics education as perceived by nursing students: Development and testing of a novel assessment instrument. Nursing Ethics, 22, 287–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterstein, T.‐B. (2012). Nurses' experiences of the encounter with elder neglect. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 44, 55–62. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2012). WHO Global Competency Model. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/employment/WHO_competencies_EN.pdf [Google Scholar]