Abstract

Aim

To examine a hypothetical model of physical activity and health outcomes (cardiovascular risk and quality of life) based on the information–motivation–behavioural skills model in adults.

Design

A cross‐sectional survey.

Methods

A total of 165 adults with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome were recruited between October 2016 and September 2017 from the outpatient clinic in South Korea. Data were collected on the model constructs such as cognitive function, social support, depressive symptoms, barriers to self‐efficacy, physical activity and quality of life. A hypothetical model was tested using the AMOS 25.0 program.

Results

Cognitive function and barriers to self‐efficacy had a direct effect on physical activity. Physical activity had a direct effect on cardiovascular risk, while social support and depressive symptoms had a direct effect on quality of life.

Conclusions

The information–motivation–behavioural skills model can predict physical activity and, in turn, cardiovascular risk and quality of life in adults with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, depression, metabolic syndrome, osteoarthritis, physical activity, quality of life, self‐efficacy, social support

1. INTRODUCTION

With global ageing and the growing obesity epidemic, osteoarthritis is one of the most rapidly increasing chronic conditions (Deshpande et al., 2016; Nelson, 2018; Osteoarthritis Research Society International, 2016). Osteoarthritis, which occurs most often in the knees and hips, can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) owing to activity limitations associated with severe joint pain and negatively affect quality of life (QoL) (Barbour, Helmick, Boring, & Brady, 2017). In South Korea, the prevalence rates for doctor‐diagnosed osteoarthritis were 10.9% and 21.7% for all adults and those aged 50 years and above in 2017, respectively (Korea Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2018). Osteoarthritis is linked to increased rates of comorbidity (Suri, Morgenroth, & Hunter, 2012), including metabolic syndrome, obesity, cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which adversely affect QOL (Liu, Waring, Eaton, & Lapane, 2015). People with metabolic syndrome are more susceptible to develop osteoarthritis (Afifi et al., 2018; Chadha, 2016). The most common components of metabolic syndrome in patients with knee osteoarthritis include abdominal obesity (90%), hypertension (40%) and diabetes (15%) (Afifi et al., 2018). A systematic review of cohort studies (Nelson, 2018) reported that patients with osteoarthritis have a higher risk of CVD. Three studies confirm evidence of the association of osteoarthritis with CVD. For example, the incident CVD events with osteoarthritis were 1.22‐fold higher in Italians (Veronese et al., 2016) and 1.15‐fold higher in Taiwanese (Chung, Lin, Ho, Lai, & Chao, 2016) compared to those without osteoarthritis. Also, in a cohort study of middle‐aged British women with 23‐year follow‐up, those with both radiographic osteoarthritis and knee pain had 4‐fold higher risk for CVD‐related mortality than those without radiographic osteoarthritis and knee pain (Kluzek et al., 2016). Risk management including physical activity may slow disease progression and reduce CVD risk in adults with osteoarthritis (Suri et al., 2012).

Physical activity provides health benefits to people with chronic conditions including osteoarthritis and metabolic syndrome (DiPietro et al., 2019; Pedersen & Saltin, 2015; Rausch Osthoff et al., 2018). However, despite the known benefits of regular physical activity, the global proportion of people who are active enough to enjoy these health benefits is low and decreases with age. Worldwide, 23% of adults are physically active, with up to 54% of adults being sedentary in some high‐income countries (Lindsay Smith, Banting, Eime, O'Sullivan, & Uffelen, 2017). In particular, people with osteoarthritis are more likely to exhibit comorbidities, barriers to physical activity and inactive lifestyles relative to the general population (Gay, Guiguet‐Auclair, Mourgues, Gerbaud, & Coudeyre, 2019). Increased daily duration of physical activity could reduce the risk of developing metabolic syndrome in adults with osteoarthritis (Liu et al., 2015). Although physical activity has consistently been associated with enhanced QoL and lower CVD risk (DiPietro et al., 2019; Jeong et al., 2019; White, Wojcicki, & McAuley, 2009), additional effort is required to determine whether this relationship is direct or occurs through other psychosocial factors in adults with osteoarthritis. In addition, previous studies have reported that suitable theory‐based intervention strategies could be more effective in enhancing behavioural adherence than intervention strategies lacking a theoretical foundation (Chang, Choi, Kim, & Song, 2014; Conn, Enriquez, Ruppar, & Chan, 2016).

2. BACKGROUND

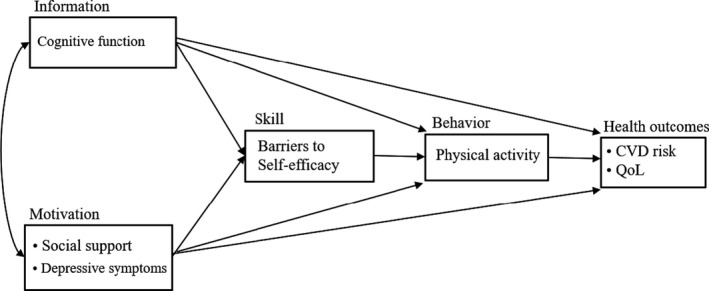

The information–motivation–behavioural skills (IMB) model is a framework that is commonly used to enhance understanding of predictive factors for health behaviour and outcomes (Chang et al., 2014; Fisher, Fisher, Amico, & Harman, 2006). The IMB model posits that each element (i.e. information, motivation and behavioural skills) exerts a direct effect on health behaviour, but that behavioural skills would mediate the effect of information and motivation on health behaviour (Figure 1). Studies have reported that certain factors such as cognitive function (information), social support (extrinsic motivation), depressive symptoms (intrinsic motivation) and self‐efficacy to overcome barriers (behavioural skills) are associated with physical activity. An emerging body of evidence has identified that physical activity levels and engagement in leisure activities are predictors of cognitive function (Gamage, Hewage, & Pathirana, 2019). A recent systematic review involving older adults suggested that people with greater social support for physical activity are more likely to engage in physical activity during leisure time (Lindsay Smith et al., 2017). Moreover, people with knee osteoarthritis who engage in sufficient physical activity have been shown to display significantly lower levels of depressive symptoms relative to those who do not engage in sufficient physical activity (Mesci, Icagasioglu, Mesci, & Turgut, 2015). Further, some studies have demonstrated that greater self‐efficacy for physical activity enhanced physical activity engagement (Curtis & Windsor, 2019; Rush et al., 2019).

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized information–motivation–behavioural skills model of physical activity

The IMB model has been applied to explain adherence to health behaviour, including physical activity, in various samples (Fisher et al., 2006; Mayberry & Osborn, 2014; Nelson et al., 2018). However, further empirical research is required to improve the model's robustness in predicting physical activity and its outcomes (CVD risk and QoL) in adults with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome, which are prevalent comorbidities. Furthermore, in predicting physical activity adherence using the IMB model, it is unclear which factors should be considered to promote physical activity in people with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome.

The aim of this study was to examine a hypothetical model of physical activity and health outcomes based on the IMB model in adults with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome. We hypothesized that information (cognitive function), motivation (social support and depressive symptoms) and behavioural skills (barriers to self‐efficacy) would be associated with physical activity and its outcomes (CVD risk and QoL) (Figure 1).

3. METHODS

3.1. Design

This study used a cross‐sectional survey design.

3.2. Participants and setting

The study included 165 adults with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome from the outpatient clinic at a university hospital located in an urban area in South Korea. The sample size was determined based on the recommendation that at least 150 responses are needed for structural equation modelling research (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Participants were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: doctor diagnosed with osteoarthritis and at risk for metabolic syndrome based on any one of the following National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Adult Treatment Panel III criteria (Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, & Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults, 2001): (a) abdominal obesity, defined in the Asian population (Lee et al., 2007) as a threshold of waist circumference (WC) of ≥85 cm for women and ≥90 cm for men; (b) total cholesterol (TC) level of ≥200 mg/dl or triglyceride level of ≥150 mg/dl; (c) high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol level of <50 mg/dl for women and <40 mg/dl for men; (d) elevated blood pressure (BP), systolic BP ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 85 mmHg; and (e) fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level of ≥100 mg/dl. Participants were classified as diabetic or hypertensive if they were taking medications for diabetes or hypertension, respectively. The exclusion criterion was adults diagnosed with major depressive disorder as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Cognitive function

Cognitive function was evaluated using the Short Form of the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE‐SF). The MMSE‐SF measures orientation to time (2 points) and place (2 points), memory (3 points), and attention and calculation (3 points). Possible scores range from 0–10, with higher scores denoting better cognitive function (Haubois et al., 2011). Scores of 6 or more indicate normal cognitive function. The MMSE‐SF was administered and scored by a Registered Nurse.

3.3.2. Social support

The Duke–UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (DUFSSQ) was used to measure the amount and types of perceived emotional social support (Broadhead, Gehlbach, de Gruy, & Kaplan, 1988). It includes eight items pertaining to having a confidant (i.e. someone to talk to, socialize with and receive advice from) and affective support (i.e. being shown love and affection). Items were scored using a five‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 (much less than I would like) to 5 (as much as I would like). Higher scores reflect higher levels of perceived emotional social support. Cronbach's alpha was 0.91 in a previous study with the South Korean population (Kim et al., 2015) and 0.92 in this study, indicating satisfactory internal consistency.

3.3.3. Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies‐Depression (CES‐D) scale (Radloff, 1977). The CES‐D scale assesses the frequency with which each of 20 events occurred during the preceding 7 days. The 20‐item CES‐D scale consists of both positive and negative affect. Items were scored using a four‐point Likert scale (0–3) ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). To determine a depressive symptoms score, the item responses were summed with a total score ranging from 0–60. Scores of 16 or more indicate more depressive symptoms. Cronbach's alpha was 0.90 in a previous study (Radloff, 1977) and .93 in this study, indicating satisfactory internal consistency.

3.3.4. Barriers to self‐efficacy

Barriers to self‐efficacy were assessed by the Barriers Self‐Efficacy Scale (BARSE) (McAuley, 1992). This 13‐item scale reflects participants' perceived confidence to exercise three times per week or for 150 min per week while overcoming frequently identified exercise barriers. Participants report their confidence to perform the exercise on a 100‐point percentage scale with 10‐point increments, ranging from 0% (not at all confident) to 100% (highly confident). The confidence ratings for the items are summed and then divided by the total number of items in the scale, resulting in a possible self‐efficacy score of 0–100. Higher scores indicate higher barriers to self‐efficacy. Cronbach's alpha was 0.88 in middle‐aged adults in a previous study (McAuley, 1992) and 0.91 in this study, indicating satisfactory internal consistency.

3.3.5. Physical activity

The seven‐item International Physical Activity Questionnaires (IPAQ) short form was used to assess PA levels. The IPAQ short form assesses engagement in PA during the preceding 7 days and the duration of three types of activities: (a) vigorous PA, (b) moderate PA and (c) walking. Total duration (minutes) across these types of activities was used to calculate total metabolic equivalents of task (METs)‐min/week based on the following formula: (8.0 METs × total duration of vigorous activity) + (4.0 METs × total duration of moderate activity) + (3.3 METs × total duration of walking) (Ainsworth et al., 2000). Spearman's rho clustered around 0.8, indicating acceptable stability (Craig et al., 2003).

3.3.6. Quality of life

The five‐item World Health Organization Well‐Being Index—Short version (WHO‐5) was used to measure subjective general psychological general well‐being (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2019). The scale consists of five items concerned with feeling cheerful, relaxed, vigorous, rested and fulfilled over the last 14 days. Items are rated on a five‐point Likert scale from 0 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). The possible total raw score ranges from 0 (absence of well‐being) to 25 (maximal well‐being). Because scales measuring QoL are conventionally converted to a percentage scale from 0 (absent) to 100 (maximal), the guidelines recommend that the raw score be multiplied by 4 (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2019). Cronbach's alpha for the scale was 0.78 in this study.

3.3.7. CVD risk

The 10‐year absolute CVD risk (as a percentage) was calculated using the Framingham risk equation (D'Agostino et al., 2008). The 10‐year general CVD risk profile for use in primary care, based on the study conducted by Framingham, consists of the following seven items: sex, age, systolic BP, body mass index (BMI), treatment for hypertension, diabetes and smoking status. Ten‐year CVD risk levels were classified as follows: low: <10%, moderate: 10% to 20% and high: >20%. CVD includes myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death and other incidents including ischaemic heart disease, stroke or death resulting from peripheral vascular disease.

3.4. Data collection

The participants were patients who visited an orthopaedic outpatient clinic with osteoarthritis symptoms; physicians reviewed their medical records and conditions and identified potential participants who met the study inclusion criteria. The researcher and a trained staff member confirmed whether patients on the list were eligible for participation. The researcher explained the study in detail to patients considered eligible, and those who agreed to participate provided written informed consent. All survey questionnaires were self‐reported. The staff assisted patients who needed help to answer the questionnaires, and the survey took approximately 20 min to complete. Demographic and disease‐related data were collected on age, sex, education, current smoker, types of osteoarthritis and comorbidity diseases. A trained nurse conducted a face‐to‐face cognitive assessment and measured BP and WC manually using a mercury sphygmomanometer (HM‐1101) and tape measure (Hico), respectively, at the outpatient clinic. Blood test results (TC and FPG) were obtained from participants' electronic medical records. The data were collected between October 2016–September 2017. This study followed the STROBE checklist for reporting this study.

3.5. Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows and SPSS AMOS version 25.0 (IBM Corp.) were used to perform the data analysis. Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients were used to summarize each of the IMB construct scores and to explore correlations between variables, respectively. There were no missing data. The data were examined to determine whether the assumption of multivariate non‐normality was met; variables with skewness of <2.0 and kurtosis of <7.0 were considered acceptable (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). All variables showed acceptable skewness and kurtosis, with the exception of MET‐min/week of physical activity (skewness = 2.676, kurtosis = 7.740). Therefore, 5,000 bootstrapped samples were used to calculate Bollen–Stine chi‐square and to estimate robust standard errors, bias‐corrected p values for parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for indirect effects (Chernick, 2008). Model fit was examined using the following additional indices: chi‐square mean/degree of freedom (CMIN/DF, χ2/df), comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI, values > 0.90 represent an acceptable fit and > 0.95 a good fit), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR, < 0.08 indicated acceptable fit) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, ≤ 0.06 with a CI of 0.00–0.08 indicated a good fit) (Kline, 2005).

3.6. Ethics

The institutional review board at the institution with which the first author was affiliated approved the study (SBR‐SUR‐16‐355). Participants were informed about the study purpose, voluntary nature of participation, confidentiality, risks and benefits, and compensation and provided with contact details of the person to whom they were to address questions. In addition, participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study any time without penalty. All participants signed a written informed consent form.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Participants' general and diseases‐related characteristics

The sociodemographic and disease‐related characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The participants' mean age was 72.44 years (SD = 12.74, range 49–88), and 90.9% of them were women. In addition, 89.1% of participants had completed six or more years of education, and 96.4% were non‐smokers. Moreover, 77.0% of participants had been diagnosed with primary osteoarthritis and 58.8% had undergone surgery for osteoarthritis. Most participants had at least one comorbid disease, and hypertension (78.8%) was the most prevalent comorbidity.

TABLE 1.

Participants characteristics (N = 165)

| Variables | N (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72.44 ± 12.74 | |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 15 (9.1) | |

| Women | 150 (90.9) | |

| Education (years) | ||

| <6 | 18 (10.9) | |

| 6–9 | 96 (58.2) | |

| 10–12 | 28 (17.0) | |

| ≥13 | 23 (13.9) | |

| Current smoker | ||

| Yes | 6 (3.6) | |

| No | 159 (96.4) | |

| Type of osteoarthritis | ||

| Primary | 127 (77.0) | |

| Secondary | 38 (23.0) | |

| Operation for osteoarthritis | ||

| Yes | 97 (58.8) | |

| No | 68 (41.2) | |

| Metabolic risk factors | ||

| WC (cm) | ||

| Women | 85.29 ± 7.78 | |

| Men | 90.36 ± 4.88 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.89 ± 2.93 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 133.35 ± 12.74 | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 79.79 ± 7.12 | |

| TC (mg/dl) | 167.79 ± 42.40 | |

| FPG (mg/dl) | 115.31 ± 30.13 | |

| Management of metabolic syndrome | ||

| Medication, yes | 154 (93.3) | |

| Exercise, yes | 43 (26.1) | |

| Diet, yes | 33 (20.0) | |

| Complementary, yes | 11 (6.7) | |

| Comorbidity diseases | ||

| Hypertension, yes | 130 (78.8) | |

| Dyslipidaemia, yes | 97 (58.8) | |

| Osteoporosis, yes | 81 (49.1) | |

| Diabetes, yes | 43 (26.1) | |

| Other, yes | 34 (20.6) | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; TC, total cholesterol; WC, waist circumference.

4.2. Descriptive statistics and correlations of study variables

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the study variables. The mean (SD) scores for cognitive function, social support, depressive symptoms and barriers to self‐efficacy were 8.74 (1.08) out of 10, 24.92 (8.10) out of 40, 16.63 (10.58) out of 60, and 43.20 (18.32) out of 100, respectively. The mean (SD) scores for total physical activity time and total physical activity level were 47.24 (54.75) min/week and 769.01 (1,081.64) MET‐min/week; in addition, the most frequently reported activity was walking at 614.81 (855.60) MET‐min/week, and one‐third of participants (N = 55) engaged in regular physical activity (≥600 MET‐min/week). The mean (SD) score for 10‐year CVD risk based on the Framingham formula was 23.10% (7.89). Regarding levels of CVD risk, 66.7% of participants were at high‐risk for CVD (≥20%). The mean (SD) score for QoL was 38.79 (19.37) out of 100.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics of study variables (N = 165)

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Skewness |

|---|---|---|

| Information | ||

| Cognitive function | 8.74 ± 1.08 | −0.401 |

| Motivation | ||

| Social support | 24.92 ± 8.10 | −0.038 |

| Depressive symptoms | 16.63 ± 10.58 | 0.920 |

| Behavioural skills | ||

| Barriers to self‐efficacy | 43.20 ± 18.32 | 0.358 |

| Behaviour | ||

| Physical activity (total time, min/week) | 47.24 ± 54.75 | 2.312 |

| Physical activity (total level, MET‐min/week) | 769.01 ± 1,081.64 | 2.676 |

| Health outcomes | ||

| CVD risk (%) | 23.10 ± 7.89 | −0.682 |

| Quality of life (score) | 38.79 ± 19.37 | 0.308 |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; MET, metabolic equivalent; SD, standard deviation.

Physical activity level was significantly positively correlated with cognitive function (r = .215, p = .006), barriers to self‐efficacy (r = .280, p < .001) and QoL (r = .216, p = .005), whereas it was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (r = −.196, p = .012). CVD risk was correlated with cognitive function, social support and barriers to self‐efficacy (all ps < .05), but not QoL (p = .957). QoL was correlated with depressive symptoms, social support, barriers to self‐efficacy and physical activity level (all ps < .05).

4.3. An empirical test of the IMB model of physical activity

The hypothesized model of physical activity showed a good fit to the data: χ 2(8) = 12.977, p = .113, CMIN/DF = 1.622, CFI = 0.977, TLI = 0.920, RMSEA = 0.062 and SRMR = 0.0438 (Figure 2). Social support, depressive symptoms, cognitive function and age explained 20.4% of the variance in barriers to self‐efficacy, which then was significantly associated with and explained 12.2%, 18.6% and 32.3%, of the variances in physical activity, CVD risk and QoL, respectively (ps < .05; see Figure 2 and Table 3). Cognitive function and barriers to self‐efficacy directly affected physical activity (β = 0.186, p = .020; β = 0.250, p = .005, respectively), whereas social support and depressive symptoms affected physical activity through self‐efficacy. Physical activity had a direct effect on cardiovascular risk (β = −0.151, p = .046), whereas social support and depressive symptoms directly affected quality of life (β = 0.146, p = .049; β = −0.448, p < .001 respectively).

FIGURE 2.

An empirical test of the hypothesized information–motivation–behavioural skills model of physical activity using path model with standardized path coefficients (β) in adults with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

TABLE 3.

Total, direct and indirect effects for hypothesized model

| Endogenous variables | Exogenous variables | SMC | Direct effect β (p) | Indirect effect β (p) | Total effect β (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers to self‐efficacy | Age | 0.204 | 0.180 (.019) | 0.180 (.019) | |

| Cognitive function | 0.052 (.499) | 0.052 (.499) | |||

| Social support | 0.250 (.007) | 0.250 (.007) | |||

| Depressive symptoms | −0.212 (.009) | −0.212 (.009) | |||

| Physical activity | Age | 0.122 | 0.021 (.770) | 0.045 (.014) | 0.066 (.364) |

| Cognitive function | 0.186 (.020) | 0.013 (.449) | 0.199 (.021) | ||

| Social support | −0.076 (.300) | 0.063 (.006) | −0.013 (.888) | ||

| Depressive symptoms | −0.093 (.293) | −0.053 (.008) | −0.145 (.090) | ||

| Barriers to self‐efficacy | 0.250 (.005) | 0.250 (.005) | |||

| CVD risk | Age | 0.186 | 0.409 (<.001) | −0.010 (.249) | 0.399 (<.001) |

| Cognitive function | −0.030 (.048) | −0.030 (.048) | |||

| Social support | 0.002 (.685) | 0.002 (.685) | |||

| Depressive symptoms | 0.022 (.045) | 0.022 (.045) | |||

| Barriers to self‐efficacy | −0.038 (.042) | −0.038 (.042) | |||

| Physical activity | −0.151 (.046) | −0.151 (.046) | |||

| Quality of life | Age | 0.323 | 0.008 (.215) | 0.008 (.215) | |

| Cognitive function | 0.023 (.109) | 0.023 (.109) | |||

| Social support | 0.146 (.049) | −0.002 (.654) | 0.145 (.052) | ||

| Depressive symptoms | −0.448 (<.001) | −0.017 (.117) | −0.465 (<.001) | ||

| Barriers to self‐efficacy | 0.029 (.111) | 0.029 (.111) | |||

| Physical activity | 0.116 (.152) | 0.116 (.152) |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; SMC, squared multiple correlation; SRW, standard regression weight; β, standardized coefficient.

5. DISCUSSION

We used the IMB model as a framework to assess physical activity adherence and its outcomes, such as CVD risk and QoL, in patients with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome. To the best the authors' knowledge, this was the first study to examine whether the IMB model could explain physical activity and, in turn, CVD risk and QoL, in adults with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome, which are prevalent comorbidities.

The overall findings partially supported the hypothesized model. Regarding physical activity, the model revealed that cognitive function and barriers to self‐efficacy were significantly associated with physical activity. In a previous study, performance in cognitive function tasks predicted physical activity both directly and indirectly via self‐efficacy in older adults with metabolic disorders (Olson et al., 2017). However, in the current study, we observed only a direct association between cognitive function and physical activity. While this implies that maintaining good cognitive function is necessary for physical activity, many studies have shown that physical activity could be beneficial for the maintenance or improvement of cognitive function (Carvalho, Rea, Parimon, & Cusack, 2014). A systematic review of 27 randomized controlled trials, conducted to examine the effects of exercise on cognitive function in older individuals, reported that physical activity was beneficial to cognitive function (Carvalho et al., 2014). These findings indicate that physical activity and cognitive function influence each other. Therefore, people with low cognitive function require greater support for physical activity.

As expected, based on the IMB model, the current results showed that barriers to self‐efficacy were directly associated with physical activity. Consistent with this finding, self‐efficacy has previously been shown to be directly related to physical activity in older adults with metabolic disease (Olson et al., 2017). Moreover, a systematic review of social cognitive theory and physical activity reported that self‐efficacy was consistently associated with physical activity (Young, Plotnikoff, Collins, Callister, & Morgan, 2014). The current results showed that the factors directly associated with barriers to self‐efficacy were age, social support and depressive symptoms. Similarly, a previous study that reviewed 25 qualitative studies examining barriers to and facilitators of physical activity in people with knee and hip osteoarthritis reported that older age was a perceived barrier to physical activity (Kanavaki et al., 2017). In addition, studies reported that physical activity was negatively associated with increasing age (Stubbs, Hurley, & Smith, 2015) and influenced by perceived ageing (Gay et al., 2019), implying that age was a biomedical barrier self‐efficacy.

In this study, social support was directly associated with barriers to self‐efficacy, consistent with the IMB model. These results indicate that good social support could help adults with osteoarthritis to overcome barriers to self‐efficacy. Moreover, Kanavaki et al. (2017) reviewed qualitative studies regarding barriers and facilitators of physical activity for individuals with osteoarthritis and reported that social support was a facilitator of physical activity. Social support also was indirectly associated with physical activity through barriers to self‐efficacy in the current study. Previous studies have demonstrated that social support was a potential influencing factor for physical activity in adults with knee and hip osteoarthritis (Peeters, Brown, & Burton, 2015; Stubbs et al., 2015). In addition, people with greater social support for physical activity, particularly from family members, are more likely to engage in physical activity (Lindsay Smith et al., 2017). Therefore, encouragement to engage in physical activity and increased support from family members and medical staff could be beneficial.

In the current study, while depressive symptoms were directly associated with barriers to self‐efficacy, they were not directly associated with physical activity. In contrast, another study reported that participants who engaged in sufficient physical activity displayed significantly fewer depressive symptoms relative to those who did not (Mesci et al., 2015). In addition, a Japanese study involving people with osteoarthritis reported that those who experienced depression reported visiting healthcare providers and emergency rooms and were more likely to be hospitalized, increasing their health‐related burden (Tsuji, Nakata, Vietri, & Jaffe, 2019). Moreover, a study reported that people with osteoarthritis were at increased risk for depression (Tsuji et al., 2019). Therefore, it would be helpful to screen this population for depressive symptoms, as they could affect barriers to self‐efficacy. Furthermore, it is essential to recognize that low levels of physical activity could be a potential warning sign of depression. Therefore, people with depressive symptoms require additional support for physical activity adoption and maintenance.

Moreover, the results showed that age and physical activity were significantly associated with CVD risk in people with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies in which physical activity exerted beneficial effects and decreased CVD risk (Jeong et al., 2019; Lear et al., 2017). In addition, PA was more beneficial to individuals with CVD risk than it was to healthy people without CVD risk (Jeong et al., 2019). Higher levels of leisure and non‐leisure physical activity were associated with a lower risk of mortality and CVD events in individuals from 17 low‐, middle‐ and high‐income countries (Lear et al., 2017). Furthermore, other studies have confirmed that adults with osteoarthritis who engaged in physical activity could be protected from CVD risk (Curtis et al., 2017). These findings indicate that physical activity is a key factor in reducing CVD risk. Therefore, interventions that focus on fostering physical activity could make a positive contribution to the reduction of CVD risk in adults with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome.

In the current study, QoL was directly significantly associated with social support and depressive symptoms; however, physical activity was not significantly directly associated with QoL. Therefore, further studies exploring the factors associated with QoL and those that mediate the relationship between physical activity and QoL are warranted. Furthermore, this study showed that higher levels of social support and lower levels of depressive symptoms were significantly associated with increased QoL, while low levels of cognitive function were associated with reduced physical activity. Therefore, an integrated approach that includes encouragement to engage in physical activity through education regarding health benefits and opportunities to participate in physical activity programmes, provision of social support, reduction of depressive symptoms and promotion of self‐efficacy to overcome barriers to exercise could be beneficial in improving health outcomes (QoL and CVD risk) in people with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome.

This study was subjected to some limitations. For example, the data were collected from a single university hospital in South Korea via convenience sampling. Therefore, the generalizability of these results is limited because of the small, relatively homogeneous sample. In addition, the path model was based on a cross‐sectional design, which limited inference regarding causality. Furthermore, another possible source of bias is the self‐reported nature of the questionnaires, which could have entailed response bias and affected the results. Therefore, the use of objective physical activity data would be preferable in future research. Moreover, to increase generalizability and confirm the findings (i.e. causal inferences or predictive relationships between study variables), future research should use larger and more diverse samples, with a multicentre approach and longitudinal design.

6. CONCLUSION

The current findings provide evidence indicating that physical activity plays an important role in CVD risk in people with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome. These findings showed that people with higher levels of depressive symptoms displayed greater barriers to self‐efficacy, demonstrating the importance of reducing depressive symptoms in people with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome.

7. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

The results suggested that physical activity was associated with health outcome such as CVD risk, and social support and depressive symptoms were important factors associated with health outcomes such as QoL. These results confirm that the IMB model is suitable for prediction of physical activity in this population, and interventions targeting physical activity using this model could improve adherence to physical activity, lower CVD risk and improve QoL. Based on the study results, recommendations for nurses include educating patients and family members about the importance of physical activity to decrease CVD risk and promote QoL. Nurses can incorporate screening for self‐efficacy to overcome barriers to physical activity into routine clinical practice. Nurses can screen, provide nursing interventions and refer, when indicated, those adults who have depressive symptoms, cognitive decline and limited social support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed meet the authorship criteria according to the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors and are in agreement with the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge with gratitude the cooperation of the study participants and clinical staff of outpatient clinics in Suwon, Korea.

Kim C‐J, Kang HS, Kim JS, Won YY, Schlenk EA. Predicting physical activity and cardiovascular risk and quality of life in adults with osteoarthritis at risk for metabolic syndrome: A test of the information‐motivation‐behavioral skills model. Nursing Open. 2020;7:1239–1248. 10.1002/nop2.500

Funding information

This work was supported by a 2016 research grant from the Department of Nursing Science, Graduate School, Ajou University to CK. Grant no. (M‐2016‐00014).

REFERENCES

- Afifi, A. E. A. , Shaat, R. M. , Gharbia, O. M. , Boghdadi, Y. E. , Eshmawy, M. M. E. , & El‐Emam, O. A. (2018). Osteoarthritis of knee joint in metabolic syndrome. Clinical Rheumatology, 37(10), 2855–2861. 10.1007/s10067-018-4201-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, B. E. , Haskell, W. L. , Whitt, M. C. , Irwin, M. L. , Swartz, A. M. , Strath, S. J. , & Leon, A. S. (2000). Compendium of Physical Activities: An update of activity codes and MET intensities. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 32(Supplement), S498–S516. 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐5 (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J. C. , & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two‐step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, K. E. , Helmick, C. G. , Boring, M. , & Brady, T. J. (2017). Vital signs: Prevalence of doctor‐diagnosed arthritis and arthritis‐attributable activity limitation – United States, 2013–2015. MMWR. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report, 66(9), 246–253. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6609e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead, W. E. , Gehlbach, S. H. , de Gruy, F. V. , & Kaplan, B. H. (1988). The Duke‐UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Medical Care, 26(7), 709–723. 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, A. , Rea, I. M. , Parimon, T. , & Cusack, B. J. (2014). Physical activity and cognitive function in individuals over 60 years of age: A systematic review. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 9, 661–682. 10.2147/CIA.S55520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadha, R. (2016). Revealed aspect of metabolic osteoarthritis. Journal of Orthopaedics, 13(4), 347–351. 10.1016/j.jor.2016.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S. J. , Choi, S. , Kim, S. A. , & Song, M. (2014). Intervention strategies based on information‐motivation‐behavioral skills model for health behavior change: A systematic review. Asian Nursing Research, 8(3), 172–181. 10.1016/j.anr.2014.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chernick, M. R. (2008). Bootstrap methods: A guide for practitioners and researchers (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, W. S. , Lin, H. H. , Ho, F. M. , Lai, C. L. , & Chao, C. L. (2016). Risks of acute coronary syndrome in patients with osteoarthritis: A nationwide population‐based cohort study. Clinical Rheumatology, 35(11), 2807–2813. 10.1007/s10067-016-3391-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. , Cohen, P. , West, S. G. , & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/ correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Conn, V. S. , Enriquez, M. , Ruppar, T. M. , & Chan, K. C. (2016). Meta‐analyses of theory use in medication adherence intervention research. American Journal of Health Behavior, 40(2), 155–171. 10.5993/AJHB.40.2.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, C. L. , Marshall, A. L. , Sjöström, M. , Bauman, A. E. , Booth, M. L. , Ainsworth, B. E. , … Oja, P. (2003). International physical activity questionnaire: 12‐country reliability and validity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 35(8), 1381–1395. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, G. L. , Chughtai, M. , Khlopas, A. , Newman, J. M. , Khan, R. , Shaffiy, S. , & Mont, M. A. (2017). Impact of physical activity in cardiovascular and musculoskeletal health: Can motion be medicine? Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, 9(5), 375–381. 10.14740/jocmr3001w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, R. G. , & Windsor, T. D. (2019). Perceived ease of activity (but not strategy use) mediates the relationship between self‐efficacy and activity engagement in midlife and older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 23(10), 1367–1376. 10.1080/13607863.2018.1484882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino, R. B. Sr , Vasan, R. S. , Pencina, M. J. , Wolf, P. A. , Cobain, M. , Massaro, J. M. , & Kannel, W. B. (2008). General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 117(6), 743–753. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande, B. R. , Katz, J. N. , Solomon, D. H. , Yelin, E. H. , Hunter, D. J. , Messier, S. P. , & Losina, E. (2016). Number of persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US: Impact of race and ethnicity, age, sex, and obesity. Arthritis Care & Research, 68(12), 1743–1750. 10.1002/acr.22897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro, L. , Buchner, D. M. , Marquez, D. X. , Pate, R. R. , Pescatello, L. S. , & Whitt‐Glover, M. C. (2019). New scientific basis for the 2018 U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 8(3), 197–200. 10.1016/j.jshs.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (2001). Executive summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA, 285(19), 2486–2497. 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J. D. , Fisher, W. A. , Amico, K. R. , & Harman, J. J. (2006). An information‐motivation‐behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychology, 25(4), 462–473. 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamage, M. W. K. , Hewage, C. , & Pathirana, K. D. (2019). Associated factors for cognition of physically independent elderly people living in residential care facilities for the aged in Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 10.1186/s12888-018-2003-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay, C. , Guiguet‐Auclair, C. , Mourgues, C. , Gerbaud, L. , & Coudeyre, E. (2019). Physical activity level and association with behavioral factors in knee osteoarthritis. Annals of Physical & Rehabilitation Medicine, , 62(1), 14–20. 10.1016/j.rehab.2018.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubois, G. , Annweiler, C. , Launay, C. , Fantino, B. , de Decker, L. , Allali, G. , & Beauchet, O. (2011). Development of a short form of Mini‐Mental State Examination for the screening of dementia in older adults with a memory complaint: A case control study. BMC Geriatrics, 11, 59 10.1186/1471-2318-11-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S. W. , Kim, S. H. , Kang, S. H. , Kim, H. J. , Yoon, C. H. , Youn, T. J. , & Chae, I. H. (2019). Mortality reduction with physical activity in patients with and without cardiovascular disease. European Heart Journal, 40(43), 3547–3555. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanavaki, A. M. , Rushton, A. , Efstathiou, N. , Alrushud, A. , Klocke, R. , Abhishek, A. , & Duda, J. L. (2017). Barriers and facilitators of physical activity in knee and hip osteoarthritis: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. British Medical Journal Open, 7(12), e017042. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C. J. , Schlenk, E. A. , Kim, D. J. , Kim, M. , Erlen, J. A. , & Kim, S. E. (2015). The role of social support on the relationship of depressive symptoms to medication adherence and self‐care activities in adults with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(9), 2164–2175. 10.1111/jan.12682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kluzek, S. , Sanchez‐Santos, M. T. , Leyland, K. M. , Judge, A. , Spector, T. D. , Hart, D. , … Arden, N. K. (2016). Painful knee but not hand osteoarthritis is an independent predicotr of mortaliy over 23 years follow‐up of a population‐based cohort of middle‐aged women. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 75(10), 1749–1756. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). Korea Health Statistics 2017: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VII‐2). Retrieved from https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/sub04/sub04_03.do [Google Scholar]

- Lear, S. A. , Hu, W. , Rangarajan, S. , Gasevic, D. , Leong, D. , Iqbal, R. , … Yusuf, S. (2017). The effect of physical activity on mortality and cardiovascular disease in 130 000 people from 17 high‐income, middle‐income, and low‐income countries: The PURE study. Lancet, 390(10113), 2643–2654. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31634-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. Y. , Park, H. S. , Kim, D. J. , Han, J. H. , Kim, S. M. , Cho, G. J. , … Yoo, H. J. (2007). Appropriate waist circumference cutoff points for central obesity in Korean adults. Diabetes Research & Clinical Practice, 75(1), 72–80. 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay Smith, G. , Banting, L. , Eime, R. , O'Sullivan, G. , & van Uffelen, J. G. Z. (2017). The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity, 14(1), 56 10.1186/s12966-017-0509-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. H. , Waring, M. E. , Eaton, C. B. , & Lapane, K. L. (2015). Association of objectively measured physical activity and metabolic syndrome among US adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care & Research, 67(10), 1371–1378. 10.1002/acr.22587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry, L. S. , & Osborn, C. Y. (2014). Empirical validation of the information‐motivation‐behavioral skills model of diabetes medication adherence: A framework for intervention. Diabetes Care, 37(5), 1246–1253. 10.2337/dc13-1828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley, E. (1992). The role of efficacy cognitions in the prediction of exercise behavior in middle‐aged adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(1), 65–88. 10.1007/BF00848378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesci, E. , Icagasioglu, A. , Mesci, N. , & Turgut, S. T. (2015). Relation of physical activity level with quality of life, sleep and depression in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Northern Clinics of Istanbul, 2(3), 215–221. 10.14744/nci.2015.95867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, A. E. (2018). Osteoarthritis year in review 2017: Clinical. Osteoarthritis & Cartilage, 26(3), 319–325. 10.1016/j.joca.2017.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, L. A. , Wallston, K. A. , Kripalani, S. , LeStourgeon, L. M. , Williamson, S. E. , & Mayberry, L. S. (2018). Assessing barriers to diabetes medication adherence using the information‐motivation‐behavioral skills model. Diabetes Research & Clinical Practice, 142, 374–384. 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.05.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson, E. A. , Mullen, S. P. , Raine, L. B. , Kramer, A. F. , Hillman, C. H. , & McAuley, E. (2017). Integrated social‐ and neurocognitive model of physical activity behavior in older adults with metabolic disease. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 272–281. 10.1007/s12160-016-9850-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osteoarthritis Research Society International (2016). Osteoarthritis: A serious disease. Retrieved from https://www.oarsi.org/sites/default/files/docs/2016/oarsi_white_paper_oa_serious_disease_121416_1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, B. K. , & Saltin, B. (2015). Exercise as medicine ‐ evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 25, 1–72. 10.1111/sms.12581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, G. M. , Brown, W. J. , & Burton, N. W. (2015). Psychosocial factors associated with increased physical activity in insufficiently active adults with arthritis. Journal of Science & Medicine in Sport, 18(5), 558–564. 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES‐D scale: A self‐report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch Osthoff, A. K. , Niedermann, K. , Braun, J. , Adams, J. , Brodin, N. , Dagfinrud, H. , & Vliet Vlieland, T. P. M. (2018). 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 77(9), 1251–1260. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush, C. L. , Hooker, S. A. , Ross, K. M. , Frers, A. K. , Peters, J. C. , & Masters, K. S. (2019). Brief report: Meaning in life is mediated by self‐efficacy in the prediction of physical activity. Journal of Health Psychology, 10.1177/1359105319828172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs, B. , Hurley, M. , & Smith, T. (2015). What are the factors that influence physical activity participation in adults with knee and hip osteoarthritis? A systematic review of physical activity correlates. Clinical Rehabilitation, 29(1), 80–94. 10.1177/0269215514538069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suri, P. , Morgenroth, D. C. , & Hunter, D. J. (2012). Epidemiology of osteoarthritis and associated comorbidities. PM & R, 4(Suppl. 5), S10–S19. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, T. , Nakata, K. , Vietri, J. , & Jaffe, D. H. (2019). The added burden of depression in patients with osteoarthritis in Japan. Clinicoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 11, 411–421. 10.2147/CEOR.S189610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronese, N. , Trevisan, C. , De Rui, M. , Bolzetta, F. , Maggi, S. , Zambon, S. , … Sergi, G. (2016). Association of osteoarthritis with increased risk of cardiovascular diseases in the elderly: Findings from the Progetto Veneto Anziano study cohort. Arthritis and Rheumatology, 68(5), 1136–1144. 10.1002/art.39564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, S. M. , Wojcicki, T. R. , & McAuley, E. (2009). Physical activity and quality of life in community dwelling older adults. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes, 7, 10 10.1186/1477-7525-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe (2019). Wellbeing measures in primary health care/the DepCare project. Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0016/130750/E60246.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. D. , Plotnikoff, R. C. , Collins, C. E. , Callister, R. , & Morgan, P. J. (2014). Social cognitive theory and physical activity: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 15(12), 983–995. 10.1111/obr.12225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]