Abstract

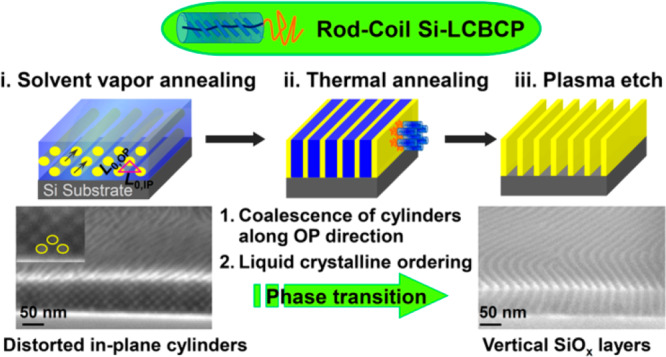

Silicon-containing block copolymer thin films with high interaction parameter and etch contrast are ideal candidates to generate robust nanotemplates for advanced nanofabrication, but they typically form in-plane oriented microdomains as a result of the dissimilar surface energies of the blocks. Here, we describe a two-step annealing method to produce vertically aligned lamellar structures in thin film of a silicon-containing rod–coil thermotropic liquid crystalline block copolymer. The rod–coil block copolymer with the volume fraction of the Si-containing block of 0.22 presents an asymmetrical lamellar structure in which the rod block forms a hexatic columnar nematic liquid crystalline phase. A solvent vapor annealing step first produces well-ordered in-plane cylinders of the Si-containing block, then a subsequent thermal annealing promotes the phase transition from in-plane cylinders to vertical lamellae. The pathways of the order–order transition were examined by microscopy and in situ using grazing incidence small-angle X-ray scattering and wide-angle X-ray scattering.

Keywords: silicon-containing block copolymer, liquid crystal block copolymer, thin film, solvent vapor annealing, thermal annealing, vertical orientation

Developing nanomaterials with high-fidelity microstructures and understanding their ordering kinetics plays a central role in creating functional materials. The self-assembly of block copolymers (BCPs) in thin film geometry can generate well-ordered nanoscale patterns making them particularly useful in a range of applications including nanolithography,1,2 high-performance separation and ion-conducting membranes,3 templates for fabrication of metal nanoparticles and nanoalloy arrays,4,5 and high surface area supports for catalysis and energy storage.3 BCP nanofabrication strategies are often based on pattern transfer from the BCP via etching processes, and thus BCP materials with one or more etch-resistant blocks are good candidates.6 Silicon-containing BCPs (Si-BCPs) comprising blocks such as PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane), PFS (polyferrocenylsilane), and POSS (polyoctahedral silsesquioxanes) combined with an organic block not only offer high etch contrast for the fabrication of nanopatterns, but also offer smaller feature sizes due to the high interaction parameter (χ) resulting from the chemical incompatibility between the Si-containing block and the organic block.6−10 Therefore, there has been considerable study directed toward the synthesis and self-assembly of Si-BCPs in bulk and thin films.6,11−14

The large difference in surface energy (γ) between the Si-containing block and the organic block and the preferential wetting of the substrate by one block typically lead to in-plane orientation of lamellar and cylindrical microdomains in thin films of Si-BCPs.15,16 Vertical orientation of the microdomains is often useful, for example, in making pores or channels for filtration membranes or lithography templates.17−19 This can be accomplished by neutralizing the thin film interfaces so that Δγ = γAS– γBS = 0, where A represents the A block, B the B block, and S the bounding surface, e.g., by functionalization of substrate surfaces using brush layers,20,21 the use of topcoats, or a filtered plasma treatment to cross-link the film surface prior to annealing.22 Annealing methods such as cold zone annealing and solvent vapor annealing promote vertical alignment of microdomains in thin films.23,24

By incorporation of liquid crystalline (LC) components into block copolymers,25 LC block copolymers (LCBCPs) can be designed to produce hierarchical ordered supramolecular nanostructures with additional contributions to control microdomain morphologies and orientations from the interplay between the LC ordering and microphase separation.26−28 For example, the cylindrical morphology of photoresponsive LCBCPs has been directed from random or in-plane orientation to an out-of-plane arrangement upon photoirradiation,29−31 and a magnetic field can also induce the alignment of LC mesogens and microdomains. For conformationally asymmetric rod–coil LCBCPs, special phase behaviors including asymmetric phase diagrams and anisotropic morphologies such as zigzag and wavy lamellae are driven by the contribution of the geometrical asymmetry and the rod organization,32,33 and provide the ability to produce asymmetrical patterns and thin lamellae.

A class of high-χ silicon-containing LCBCPs can be designed that combine the merits of the silicon-containing BCPs and the LCBCPs. Our previous work on a mesogen-jacketed liquid crystalline polymer (MJLCP) consisting of a silicon-containing rod–coil LCBCP, poly(dimethylsiloxane)-b-poly{2,5-bis[(4-methoxyphenyl)-oxycarbonyl]styrene} (PDMS-b-PMPCS, or DM), showed the potential of these materials to produce well-ordered nanostructures in which the liquid-crystalline PMPCS block influences the microphase separation behavior in bulk and thin films.34 Long-range ordered thin film morphologies of the cylindrical rod–coil PDMS-b-PMPCS were achieved through a combination of substrate functionalization and thermal annealing.35 However, regulating the vertical orientation of the silicon-containing LCBCP is still unexplored.

In this work, we demonstrate a two-step annealing approach toward the fabrication of long-range ordered through-thickness vertical lamellar microdomains in a compositionally asymmetrical PDMS-b-PMPCS rod–coil BCP with volume fraction of PDMS ∼ 22.5%. Solvent annealing was first utilized to produce a distorted in-plane cylindrical initial morphology with the rod block in an amorphous state. A subsequent thermal anneal of the in-plane cylindrical morphology resulted in vertical lamellae with hexagonal columnar nematic liquid crystalline ordering of the rod block parallel to the substrates. The orientation and ordering of the lamellar structure was examined by GISAXS and GIWAXS, and the morphologies were confirmed by SEM. The lamellae were converted into vertical SiOx fins by oxygen plasma etching, or into PMPCS lamellae by etching away the PDMS using a CF4 plasma. This work illustrates intriguing opportunities for controlling the vertical orientation of microdomains in a high-χ BCP by introducing a LC block.

Results and Discussion

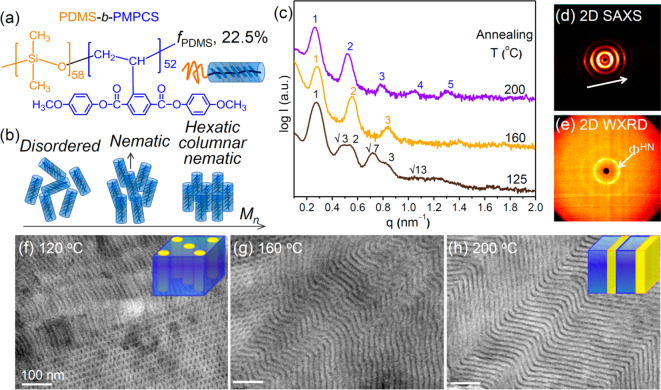

The conformationally asymmetrical PDMS-b-PMPCS (DM, Figure 1a) block copolymer has a high χ value estimated as about 4 times that of the well-studied high-χ BCP PDMS-b-PS (χPDMS-b-PMPCS ≈ 4χPDMS-b-PS).12,35 The phase behavior of the thermotropic liquid crystalline PMCPS is highly dependent on its molecular weight (MW) and the thermal annealing temperature. PMPCS with lower MW (<12 kg/mol) is amorphous over the entire temperature range before decomposition, whereas PMPCS with intermediate MW (12–17 kg/mol) is amorphous at low temperatures and transitions into a columnar nematic LC phase on annealing. PMPCS with higher MW forms a hexatic columnar nematic LC at high temperatures.36,37 The disordered phase, nematic columnar phase, and hexatic columnar nematic phase are illustrated in Figure 1b. In addition, once the PMPCS rods arrange into the LC phase, the LC ordering is preserved upon heating up to decomposition or upon cooling to room temperature.35 The molecular weight and phase behavior of the PMPCS block therefore have a great influence on the microphase separation of the PDMS-b-PMPCS BCP in bulk and thin film.35

Figure 1.

(a) Chemical structure of PDMS-b-PMPCS block copolymer and (b) schematic illustrations of the disordered phase, nematic columnar LC phase, and hexatic columnar nematic LC of PMPCS. (c) 1D SAXS profiles of bulk BCP samples after thermal annealing at indicated temperatures. (d, e) 2D SAXS and WAXS patterns after annealing at 200 °C, and (f–h) TEM images of samples annealed at 125, 160, and 200 °C, with structural schematics in the insets of f and h. All scale bars in the TEM images are 100 nm.

Bulk Morphology of the PDMS-b-PMPCS Liquid Crystal Block Copolymer

We first describe the effect of thermal annealing on the morphology and ordering of bulk D58M52. The liquid crystalline phase behavior of the PMPCS block was first confirmed by the one-dimensional (1D) wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) experiments (Figure S1). The 1D WAXD profiles of the as-cast and heated samples below 150 °C show an amorphous halo, but a sharp and intense peak at q* ≈ 3.956 nm–1 corresponding to a d-spacing of 1.57 nm appears when the annealing temperature exceeds 160 °C, consistent with the nematic liquid crystalline phase above 160 °C. We combined small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) profiles and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) results to identify the microphase separation behavior upon annealing at 125, 160, and 200 °C (Figure 1). The sample annealed at 125 °C forms hexagonally packed PDMS cylindrical microdomains (HEX) with periodicity of 24 nm, demonstrated by the scattering peaks with a scattering vector ratio of 1:√3:2:√7:3:√13 with the primary scattering peak q* at 0.260 nm–1 in the SAXS profile (Figure 1c) and the cylindrical patterns in the TEM image (Figure 1f). After annealing at 160 °C, the SAXS peaks present a scattering vector ratio of 1:2:3 with the q* at 0.260 nm–1 and a d-spacing value of 24.0 nm, indicating that the nanostructure transforms to a lamellar structure (LAM) when the PMPCS transformed into the liquid crystalline phase. TEM indicates a mixed morphology of LAM and HEX as well as wavy lamellae formed by the merging of cylinders perpendicular to their axes (Figure 1g). On further increasing the annealing temperature to 200 °C, a highly ordered lamellar nanostructure formed with periodicity of 23.8 nm indicated by higher order scattering peaks appearing in the SAXS profiles, and zigzag lamellae are observed in TEM experiments (Figure 1h). The 2D SAXS and 2D WAXD pattern (Figures 1d,e) of the 200 °C annealed sample illustrate the hierarchical structure. 2D SAXS presents several pairs of diffraction arcs originating from the layer structure indicating well orientated lamellae (Figure 1d). 2D WAXD presents 6-fold symmetric scattering patterns (Figure 1e) indicating the hexatic columnar nematic liquid crystalline phase (ΦHN) of the rigid PMPCS block, which further demonstrates the conformational asymmetry of the D58M52. These data show that the D58M52 self-assembled into a LAM structure with the PMPCS rod block forming the ΦHN LC phase. The formation of the hexatic columnar nematic ΦHN LC instead of the nematic LC phase previously reported for D58M4435 is attributed to the higher MW and narrow polydispersity of the PMPCS block in the D58M52. The strong tendency for ordering of the LC block promotes the formation of LAM even though the composition is highly asymmetric (fPDMS ∼ 22.5%). The asymmetry of LAM structure was demonstrated by TEM (Figure 1h) in which the darker PDMS domain is much thinner than the lighter PMPCS domain. The asymmetrical LAM structure is schematically illustrated in the inset of Figure 1h.

Well-Ordered In-Plane Cylinders in Thin Films via Solvent Vapor Annealing

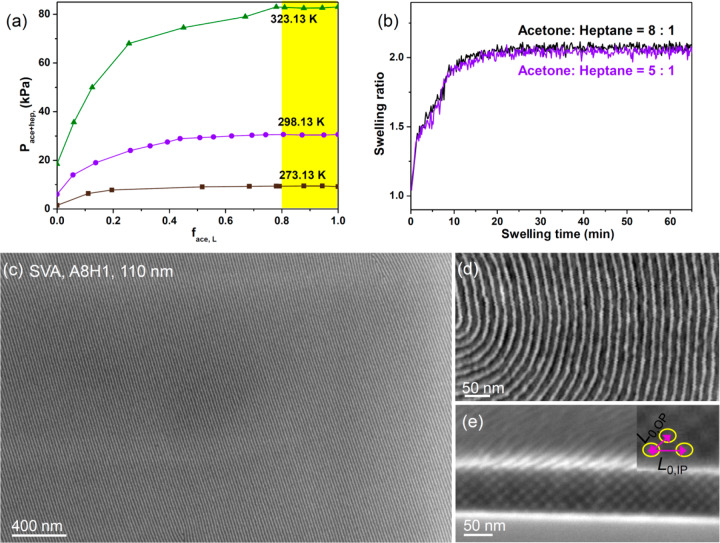

We now describe the morphology of thin films of the D58M52 thin films, which were spin-coated with initial thickness 50–110 nm on PS brush-functionalized silicon substrates then treated by solvent vapor annealing (SVA). SVA provides fast ordering and orientation tunability by lowering the energy barrier and the χN value,38 and the selectivity of the solvent vapor toward different polymer blocks influences the chain conformation and the effective volume fraction in the swelled state and provides a convenient method to obtain a range of morphologies from a single BCP.14,39 According to the solubility parameters of the PDMS (δPDMS = 15.3 MPa1/2) and PMPCS (δPMPCS = 20.7 MPa1/2), we chose acetone (δace = 19.8 MPa1/2) and heptane (δhep = 15.2 MPa1/2) as the constituents of the solvent vapor.14,40 The acetone:heptane mixture is a nonideal solution and the partial pressure of acetone is much higher than that of heptane. On the basis of the experimental data for the binary liquid system of acetone and heptane,41,42 the total vapor pressure of the acetone:heptane mixture as a function of the molar ratio of acetone is plotted in Figure 2a. When the mole ratio of acetone in the mixed solvents was higher than 0.8, the total vapor pressure is estimated to approach the partial pressure of acetone at 298 K, ∼30.6 kPa. The saturated swelling ratio of the film was maintained close to 2.0 (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Plots of reported values for total partial pressure of acetone and heptane (Pace+hep) as a function of the mole fraction of the acetone in the liquid (face,L).41,42 (b) Swelling ratios as a function of swelling time within different solvent mixtures. Representative (c, d) top-view and (e) cross-section SEM images of long-range ordered oxidized PDMS cylindrical nanopatterns with in-plane orientation formed after SVA with volumetric ratio of acetone:heptane 8:1. The inset in (e) is a higher magnification SEM image showing the cylinder–cylinder distances. The PMPCS block was in an amorphous phase after the RT SVA.

The as-cast film shows the presence of poorly ordered PDMS spheres and short worm-like structures (Figure S2). SVA in a vapor produced from acetone:heptane volumetric ratios of 8:1 to 5:1 led to well-ordered in-plane PDMS cylinders. Figure 2c displays a pattern of in-plane cylinders formed in the 110 nm thick thin film after annealing using acetone:heptane 8:1. Figure 2d shows a higher magnification image in which the silica patterns in the upper layer of cylinders appear brighter than the lower layer,2 and Figure 2e shows a cross-section with 8 layers of in-plane cylinders. The cylinder-to-cylinder distance in the in-plane direction (L0,IP) is 21.0 nm, and the cylinder-to-cylinder distance in out-of-plane direction, L0,OP, is 16.9 nm (2/√3 × 110 nm/7.5) based on the initial film thickness (110 nm) and the number of layers under the asymmetric wetting condition. Therefore, the solvent vapor annealing resulted in distorted hexagonally packed in-plane cylinders with distortion factor (L0,OP/L0,IP) ∼ 0.80. The distortion is attributed to the reduction in film thickness during deswelling.43 In the cylindrical microdomain array formed by SVA at room temperature, the thermotropic PMPCS remains in the disordered phase,37 although we expect a preference for the semirigid rods to orient perpendicular to the intermaterial dividing surface.34

Transformation of In-Plane Cylinders Formed by Solvent Vapor Annealing into Vertically Orientated Lamellae by Thermal Annealing

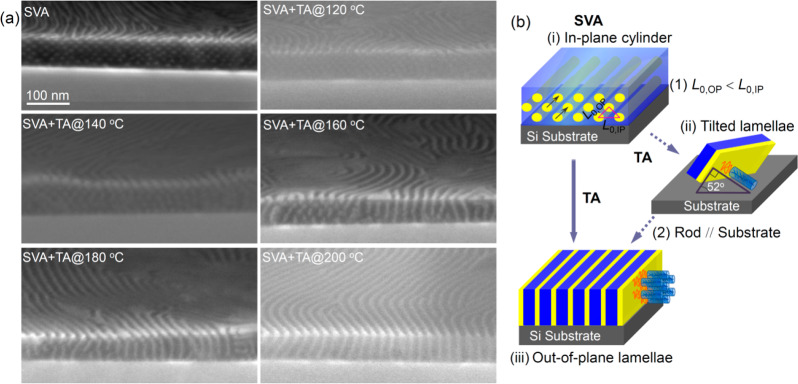

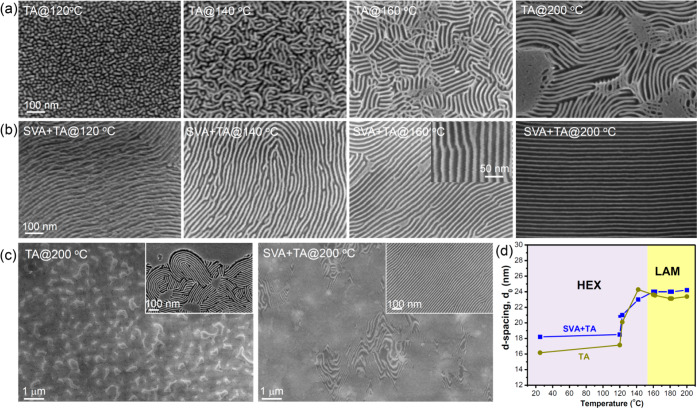

We now discuss the effect of a subsequent thermal anneal (TA) in a preheated vacuum oven for 12–24 h on the in-plane cylindrical microdomains formed by SVA. A series of SEM micrographs in Figure 3a shows the cross sections of 100 nm thick films after SVA and subsequent thermal annealing (SVA + TA) at 120, 140, 160, 180, and 200 °C. After TA at 120 and 140 °C for 24 h, the morphologies preserved the in-plane cylindrical structure that had formed by SVA, though the 140 °C anneal eliminated the distortion of the cylinder array and introduced terracing at the top surface. The in-plane center-to-center distance increased to 26 nm, and the number of layers of cylinders decreased from 7 after SVA to a terraced surface with 6 and 5 layers of cylinders after SVA + TA at 140 °C.

Figure 3.

(a) Representative cross-section SEM images showing oxidized PDMS microdomains of the D58M52 thin films after solvent vapor annealing (SVA) and a second-step thermal annealing (SVA + TA) at the indicated temperatures. (b) Schematic illustration of (i) the distorted in-plane cylinders after SVA, (ii) the transient tilted lamellae, and (iii) the out-of-plane lamellae after thermal annealing, with the in-plane aligned hexatic columnar nematic LC phase.

When the annealing temperature was 160 °C, just above the LC transition temperature, the cylinders began to elongate and merge in the out-of-plane direction, leading to a mixed morphology of distorted cylinders, discontinuous lamellae, and full lamellae. As the annealing temperature further increased to 180 °C, the cylinders were almost completely replaced by lamellae, often tilted with respect to the substrate. After annealing at 200 °C, a well-ordered vertical lamellar morphology was present throughout the thickness of the film. The width of the vertical oxidized PDMS layer is 6.2 nm, and that of the vacant space corresponding to PMPCS is about 17.8 nm, resulting in an asymmetrical line/space ratio ∼1:2.9, in reasonable agreement with the calculated thickness ratio between PDMS and PMPCS layers (about 1:3.3) based on the volume fraction of the copolymer. Through-thickness vertical lamellae were produced in a series of films with thickness 40–160 nm by the two step annealing method, Figure S3.

As a comparison we also applied the two step annealing method to thin films of another LCBCP, D58M44 with fPDMS ∼ 25%.35Figure S4a displays well-ordered in-plane PDMS cylinders after SVA in a vapor produced from an acetone:heptane volumetric ratio of 8:1. The cylinder array is distorted as the film deswells during the drying process such that the layer spacing measured along the out-of-plane direction is smaller than that measured in-plane. After subsequent thermal annealing at 200 °C for 72 h, the cross-section of the thin film still presents in-plane PDMS cylinders, but the array was no longer distorted (Figure S4b,c). These results are consistent with our previous study that D58M44 forms cylindrical microdomains after thermal annealing at 200 °C without SVA.35

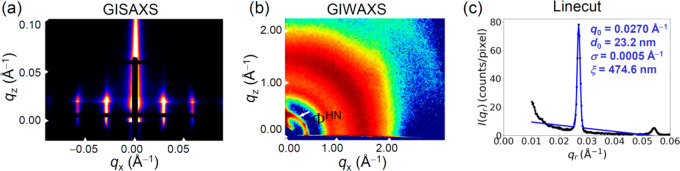

The phase transition as well as the vertical LAM and the organization of the rod block in D58M52 films were further corroborated by simultaneous grazing incidence small angle X-ray 6,scattering (GISAXS) and grazing incidence wide angle X-ray scattering (GIWAXS) analysis of the 150, 160, and 200 °C thermally annealed thin films, Figure S5 and Figure 4a–c. The GISAXS profile of the 150 °C annealed film displays arc-shaped scattering peaks, indicative of dominant in-plane cylinders (Figure S5). After annealing at 160 and 180 °C, the GIWAXS presents an intense scattering ring indicative of nematic LC ordering. The higher order peaks appear in the qx plane of the GISAXS profile but the scattering peaks are spread into arcs, which demonstrates the phase transformation from in-plane-cylinders to lamellae and also indicates the tilted intermediate LAM structure.

Figure 4.

2D (a) GISAXS and (b) GIWAXS patterns and (c) the corresponding line cut profile of the film after thermal annealing at 200 °C for 48 h.

For the 200 °C thermally annealed film, the vertical streaks in the qx plane of the GISAXS data and the second- and third-order peaks (Figure 4a) are indicative of the well-ordered vertical lamellar morphology. The first Bragg reflection with scattering peak at qx ∼ 0.0270 Å–1 corresponds to a d-spacing of 23.2 nm. The large correlation length (ξ, 474 nm) and low value of the full width at half-maximum (σ, 0.0005 Å–1) indicate a highly ordered nanostructure (Figure 4c).43 The GIWAXS profile (Figure 4b) displays 6-fold symmetric scattering patterns, indicated by two intense scattering peaks where one is located at the qz axis with qz = 0.395 Å–1 and the other is located at an angle of ∼60° to the qz axis, demonstrating the hexagonal nematic liquid crystalline phase oriented parallel to the substrate. The schematic in Figure 3b(iii) illustrates the hierarchical nanostructure of the vertically oriented LAM structure resulting from the two step annealing method, deduced from the GISAXS and GIWAXS results.

The transition of the in-plane HEX to out-of-plane LAM structure of the BCP is attributed to the following factors. Above the LC ordering temperature of the rod block, the stable phase of this BCP is lamellar, thus the cylindrical structure tends to transform to lamellae when the film was subjected to thermal annealing. The distortion of the HEX structure that resulted from SVA, in which L0,OP < L0,IP, favors coalescence of the cylinders along their closer-packed direction (Figure 3b(i)) to form lamellae oriented at about 52° to the substrate plane. The rod block is expected to orient perpendicular to the intermaterial dividing surfaces of the lamellar structure,44i.e., at 38° to the substrate plane (Figure 3b(ii)). However, further annealing leads to perpendicular lamellae which allows the rigid rods to lie parallel to the substrate forming the highly ordered liquid crystalline phase (Figure 3b(iii)). Finally, the PS brush-functionalized substrate is expected to contribute to stabilizing perpendicular lamellae by decreasing the difference in interfacial tension between the two blocks with respect to the substrate, according to the sequence of solubility parameters δPDMS (15.3 MPa1/2) < δPS (18.5 MPa1/2) < δPMPCS (20.7 MPa1/2).14,40

Comparison with Single-Step Thermal Annealing

Having demonstrated the structural evolution of the as-cast D58M52 film under SVA + TA, we now compare the behavior of the film under TA alone (Figure 5a). When the as-cast thin films are thermally annealed at 120 and 140 °C for 48 h, which is just above the glass transition temperature of the rod block but below the liquid crystalline ordering temperature, the structure coarsens slightly compared to the as-cast film, Figure S2, forming spheres and short cylinders at 120 °C and interconnected cylinders at 140 °C consistent with the asymmetrical composition and the slow ordering dynamics of this rod–coil block copolymer. When the annealing temperature increased to just above the liquid crystalline ordering temperature of ∼160 °C, the morphology developed into short lamellae connected by cylinders. The lamellae are mainly perpendicular to the substrate but significant fractions of tilted and parallel lamellae were present. When the temperature increased to 200 °C, the ordering of the vertically aligned lamellae was improved but some in-plane lamellae remained. The increase in annealing temperature lowers χN and the kinetic barrier for ordering,38 and the LC ordering of the PMPCS improved, consistent with the ordering of cylinders in a prior study of a rod–coil BCP.35

Figure 5.

Representative top-view SEM images of oxidized PDMS nanopatterns formed in DM rod–coil BCP thin films after a single-step thermal annealing (a) and after solvent vapor annealing-thermal annealing (b) at 120, 140, 160, and 200 °C. The scale bars of all main SEM images are the same as in that of TA@120 °C. (c) Low magnified SEM images of the TA at 200 °C (left) and SVA + TA at 200 °C (right). (d) Plots of in-plane d-spacing value as a function of annealing temperature for the TA and SVA + TA.

In comparison, performing SVA + TA yielded a better ordered morphology at each temperature. The cross-section morphology of samples annealed in a two-step SVA + TA was already described in Figure 3, and Figure 5b shows plan-view images for comparison with the thermally annealed films in Figure 5a. The SVA + TA films formed cylinders after annealing at 120 and 140 °C, and perpendicular lamellae at 160 and 200 °C, in each case with longer correlation lengths than the corresponding samples thermally annealed without SVA. Figure 5c shows low-magnification SEM images in which the sample annealed only at 200 °C exhibits regions of in-plane lamellae over the majority of its surface, whereas the sample processed with SVA + TA 200 °C consists mainly of perpendicular lamellae. Figure S6 shows a top-view SEM image of the thin film after SVA + TA 200 °C, etched only by 30 s CF4 plasma to remove the PDMS, which further illustrates the vertical lamellar morphology of the LC block.

The periodicity of the in-plane cylinders or lamellae is plotted in Figure 5d vs annealing temperature. For the HEX we plot the layer spacing, √3/2 times the center to center spacing of the cylinders, to compare with the layer spacing of the LAM. Compared with the as-cast thin film with periodicity ∼16.5 nm, SVA leads to periodicity of 18.2 nm (= √3/2 × 21 nm). Thermal annealing in the temperature range 120–140 °C raised the periodicity further, and it stabilized at ∼24 nm above 160 °C for the LAM structure with the rod block in the liquid crystalline state.

These results show that SVA is an effective way of improving the order obtained during a subsequent TA step. Although there have been many studies on solvent vapor annealing,39,45−47 thermal annealing,23,45 and thermo/solvent annealing,48 we have herein reported a two-step SVA + TA to produce vertically oriented lamellae in a high-χ silicon-containing block copolymer.

A thermodynamic argument can be invoked to show that the free energy difference and the energy barrier is lower for the transformation from the preordered HEX (formed by SVA) to LAM compared to that from the disordered BCP to LAM. The free energy difference between a general initial state and the final LAM structure (ΔFini–lam) can be written as the contribution of three terms, with an assumption of incompressibility:49

where ΔUini–lam and ΔSini–lam are internal energy and entropy differences corresponding to the microphase separation or order–order transformation that occurs, and ΔSiso–LC is the entropy difference corresponding to the LC phase transition of the rod block. The LC phase transition does not present an enthalpy change.37

For thermal annealing (TA 200 °C), the initial phase is the disordered state:

For solvent plus thermal annealing (SVA + TA 200 °C), the initial phase consists of well-ordered in-plane cylinders:

In either case the PMPCS rod block experienced a transition from isotropic to LC, thus the ΔSiso–LC values are equivalent. Due to the unfavorable interaction between the PDMS and PMPCS, the internal energy difference = ΔUdis–lam should be negative, thus ΔUdis–lam < 0, but ΔUhex–lam → 0 and ΔUhex–lam < ΔUdis–lam. The free energy per chain can be approximated by the contact energy between blocks, and the entropy per chain for the ideal mixed phase (disordered phase) is considered to be zero,50 thus, ΔSdis–lam > 0, and ΔSdis–lam > ΔShex–lam. Therefore, ΔFdis–lam > ΔFhex–lam, and the HEX structure lies between the disordered phase and the LAM structure on the thermodynamic pathway.

Moreover, the more disordered phase must overcome a higher kinetic barrier to transform into a well-ordered structure,38 thus the energy barrier for the HEX-LAM transition should be lower than that for the disordered-LAM transition. These arguments suggest that the initial ordering provided by the SVA process promotes the transition into the final LAM structure under thermal annealing, leading to more highly ordered and less defective lamellae. The two step thermal annealing process can be described analogously. Two step thermal annealing led to better ordering than a single step thermal annealing (Figure S7). However, since the first step thermal annealing such as at 140 °C (Figure 5a) resulted in poorly ordered cylinders without the distortion factor produced by SVA, the random coalescence of cylinders in both in-plane and out-of-plane directions into lamellae during the second two step thermal annealing produced lamellae of mixed orientation.

Conclusion

A two-step annealing method has been shown to yield vertical ordering of lamellae in a liquid crystalline block copolymer with a silicon-containing block. Solvent annealing the as-cast film induces a well-ordered morphology of in-plane cylinders which transforms further into out-of-plane asymmetric lamellae on thermal annealing, promoted by the thermally induced ordering of the LC block. The HEX-LAM structural evolution was probed using cross-sectional microscopy, GISAXS and GIWAXS, highlighting the dynamic pathway of the phase transition and the hierarchical structure and relative orientation of the microdomains and the LC. This work demonstrates a facile two-step solvent plus thermal annealing technique for orientation control of a silicon-containing block copolymer. Considering the robustness and vertical orientation of the lamellae, and the ability of substrate features to template a similar LCBCP, these results offer useful routes for nanofabrication.

Experimental Section

Block Copolymer Materials and Bulk Phase Characterization

The D58M52 rod–coil block copolymer as shown in Figure 1a was synthesized through the atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) method, similarly to a previous report.34 The polymer, D58M52, has a molar mass of 25.3 kg/mol, consisting of 4.5 kg/mol PDMS and 20.8 kg/mol PMPCS, and the polydispersity index was 1.05. The volume fraction of the PDMS was fPDMS ∼ 0.225 calculated from the 1H NMR results. The D58M44 with a molar mass of 22.2 kg/mol and fPDMS ∼ 0.25 was also used.34,35

To identify the phase behavior of the D58M52 in bulk, small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) measurements were carried out on a Xeuss 2.0 instrument (Xenocs) using Cu Kα radiation at a wavelength of 0.154 nm with source operated at 50 kV and 0.6 mA. One-dimensional (1D) wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) experiments were performed on a Philips X’Pert Pro diffractometer with a 3 kW ceramic tube as the X-ray source (Cu KR) and an X’celerator detector. In both SAXS and WAXS profiles, the scattering vector q is defined as q = 4π/λ[sin θ], where the scattering angle is 2θ, and the d-spacing (d) is given by 2π/q. The phase morphologies of bulk samples were further characterized by TEM (FEI, USA) at 200 kV. 80–100 nm thick sections for TEM characterization were ultramicrotomed from a sample embedded in an epoxy resin and were collected on carbon-coated 400-mesh copper grids. Two-dimensional (2D) WAXD experiments were performed using a Bruker D8Discover diffractometer with VANTEC 500 as a 2D detector. The sample for 2D SAXS and WAXD experiments was a drawn fiber prepared using a pair of tweezers at 180 °C.

Preparation and Self-Assembly of BCP Films

Solutions of the D58M52 were made in toluene with concentration 3.0 and 4.0 wt %. Films with thickness ranging from 40 to 160 nm were obtained by spin-coating on as-received Si substrates and on PS brush-functionalized silicon substrates at various spin speeds.35 The film thickness was obtained from a reflectometry system (Filmetrics F20–UV) by measuring the reflectance spectra of the BCP thin film within a wavelength range of 300–1000 nm.

Solvent vapor annealing of the DM films was carried out for 3 h in a solvent reservoir annealing system consisting of a closed chamber of volume 80 cm3. The sample was supported above 6 mL of liquid acetone:heptane mixture in the chamber with volumetric ratio range of 8:1–5:1, corresponding to molar ratio 16:1–10:1. The chamber had a loosely fitted lid that allowed the vapor to leak out slowly at room temperature, 23 ± 2 °C, with humidity 76% (Liquid solvent is still present after 3 h annealing; complete evaporation of the solvent takes 15–24 h).4

Thermal annealing of the DM films was carried out at different temperatures under vacuum (20 Torr) for 24–72 h at each temperature.

GISAXS and GIWAXS Measurements

The GISAXS and GIWAXS measurement were performed at the Complex Materials Scattering (CMS, 11-BM) beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source II at Brookhaven National Laboratory. The X-ray energy was 13.5 keV, and beam size adjusted to 200 μm horizontal by 50 μm vertical. SAXS data were collected using a pixel-array detector (Dectris Pilatus 2M) positioned 5.090 m downstream of the sample; WAXS data were collected using a fiber-coupled CCD detector (Photonic Sciences) positioned 0.231 m downstream. Conversion to q-space was performed using a standard sample (silver behenate) for calibration. We define qz to be the vertical (film normal) direction, and qx to be the orthogonal horizontal (in-plane) direction.

Morphology Characterization of BCP Films

Before characterizing the morphologies of the thin films by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the annealed BCP thin films were subjected to selective plasma etching. Two different etching protocols were used. The first is a two-step reactive ion etching (Plasma-Therm 790) consisting of a 50 W CF4 plasma at 15 mTorr for 5 s to remove the PDMS wetting layer on the surface and a 90 W O2 plasma at 6 mTorr for 5–10 s to selectively etch the PMPCS matrix, leaving oxidized PDMS microdomains on the substrates. The second method is a one-step etching using a 50 W CF4 plasma at 15 mTorr for 30 s to remove the PDMS wetting layer on the surface and the PDMS microdomains under the wetting layer. The morphologies of the etched BCP thin films were characterized using a Zeiss Merlin high resolution SEM at 2 kV. Cross sections of the films were subjected to 5 s O2 plasma etching at 6 mTorr before SEM imaging.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from NSF DMR-1606911 and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51403132) are gratefully acknowledged. Shared experimental facilities of CMSE, an NSF MRSEC under award DMR-1419807, and the NanoStructures Laboratory were used. This research used resources of the Center for Functional Nanomaterials and the National Sunchrotron Light Source II, which are U.S. DOE Office of Science Facilities, operated at Brookhaven National Laboratory under contract No. DE-SC0012704.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.9b09702.

Additional data regarding 1D WAXS profiles of bulk sample during thermal annealing, SEM image of films of various thicknesses after various annealing and etching processes, GISAXS and GIWAXS profiles of the films after the second-step thermal annealing at different temperatures (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Arora H.; Du P.; Tan K. W.; Hyun J. K.; Grazul J.; Xin H. L.; Muller D. A.; Thompson M. O.; Wiesner U. Block Copolymer Self-Assembly–Directed Single-Crystal Homo- and Heteroepitaxial Nanostructures. Science 2010, 330, 214–219. 10.1126/science.1193369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.; Lennon E. M.; Fredrickson G. H.; Kramer E. J.; Hawker C. J. Evolution of Block Copolymer Lithography to Highly Ordered Square Arrays. Science 2008, 322, 429–432. 10.1126/science.1162950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell T. P.; Chai Y. 50th Anniversary Perspective: Putting the Squeeze on Polymers: A Perspective on Polymer Thin Films and Interfaces. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 4597–4609. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b00418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mun J. H.; Chang Y. H.; Shin D. O.; Yoon J. M.; Choi D. S.; Lee K.-M.; Kim J. Y.; Cha S. K.; Lee J. Y.; Jeong J.-R.; Kim Y.-H.; Kim S. O. Monodisperse Pattern Nanoalloying for Synergistic Intermetallic Catalysis. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 5720–5726. 10.1021/nl403542h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y.; Cha S. K.; Ha H.; Lee S.; Seo H. K.; Lee J. Y.; Kim H. Y.; Kim S. O.; Jung W. Unravelling Inherent Electrocatalysis of Mixed-Conducting Oxide Activated by Metal Nanoparticle for Fuel Cell Electrodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 245–251. 10.1038/s41565-019-0367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo T.-Y.; Krishnan M. R.; Lu K.-Y.; Ho R.-M. Silicon-Containing Block Copolymers for Lithographic Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2018, 77, 19–68. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2017.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aissou K.; Mumtaz M.; Fleury G.; Portale G.; Navarro C.; Cloutet E.; Brochon C.; Ross C. A.; Hadziioannou G. Sub-10 nm Features Obtained from Directed Self-Assembly of Semicrystalline Polycarbosilane-Based Block Copolymer Thin Films. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 261–265. 10.1002/adma.201404077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aissou K.; Mumtaz M.; Marcasuzaa P.; Brochon C.; Cloutet E.; Fleury G.; Hadziioannou G. Highly Ordered Nanoring Arrays Formed by Templated Si-Containing Triblock Terpolymer Thin Films. Small 2017, 13, 1603184. 10.1002/smll.201603184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho Y.; Aissou K.; Mumtaz M.; Kwon W.; Pécastaings G.; Mocuta C.; Stanecu S.; Cloutet E.; Brochon C.; Fleury G.; Hadziioannou G. Laterally Ordered Sub-10 nm Features Obtained From Directed Self-Assembly of Si-Containing Block Copolymer Thin Films. Small 2015, 11, 6377–6383. 10.1002/smll.201500439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J. W.; Park W. I.; Kim M.-J.; Ross C. A.; Jung Y. S. Highly Tunable Self-Assembled Nanostructures from a Poly(2-Vinylpyridine-b-Dimethylsiloxane) Block Copolymer. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 4095–4101. 10.1021/nl2016224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M.; Yue K.; Huang J.; Liu C.; Zhou Z.; Wang J.; Wu K.; Shan W.; Shi A.-C.; Cheng S. Z. D. Highly Asymmetric Phase Behaviors of Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxane-Based Multiheaded Giant Surfactants. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 1868–1877. 10.1021/acsnano.7b08687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borah D.; Rasappa S.; Senthamaraikannan R.; Kosmala B.; Shaw M. T.; Holmes J. D.; Morris M. A. Orientation and Alignment Control of Microphase-Separated PS-b-PDMS Substrate Patterns via Polymer Brush Chemistry. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 88–97. 10.1021/am302150z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.; Cheng L.-C.; Gadelrab K. R.; Ntetsikas K.; Moschovas D.; Yager K. G.; Avgeropoulos A.; Alexander-Katz A.; Ross C. A. Double-Layer Morphologies from a Silicon-Containing ABA Triblock Copolymer. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 6193–6202. 10.1021/acsnano.8b02851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L.-Y.; Liao F.; Cheng L.-C.; Lee S.; Ran R.; Shen Z.; Ross C. A. Core–Shell and Zigzag Nanostructures from a Thin Film Silicon-Containing Conformationally Asymmetric Triblock Terpolymer. ACS Macro Lett. 2019, 8, 852–858. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.9b00283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotrik K. W.; Hannon A. F.; Son J. G.; Keller B.; Alexander-Katz A.; Ross C. A. Morphology Control in Block Copolymer Films Using Mixed Solvent Vapors. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 8052–8059. 10.1021/nn302641z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavakkoli K. G. A.; Nicaise S. M.; Gadelrab K. R.; Alexander-Katz A.; Ross C. A.; Berggren K. K. Multilayer Block Copolymer Meshes by Orthogonal Self-Assembly. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10518. 10.1038/ncomms10518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang J.; Kim S. H.; Drockenmuller E.; Misner M. J.; Russell T. P.; Hawker C. J. Defect-Free Nanoporous Thin Films from ABC Triblock Copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 7622–7629. 10.1021/ja0608141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J.; Yao X. P.; Liou J. Y.; Sun W.; Sun Y. S.; Wang Y. Membranes with Highly Ordered Straight Nanopores by Selective Swelling of Fast Perpendicularly Aligned Block Copolymers. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9961–9974. 10.1021/nn403847z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. Y.; Gwyther J.; Manners I.; Chaikin P. M.; Register R. A. Metal-Containing Block Copolymer Thin Films Yield Wire Grid Polarizers with High Aspect Ratio. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 791–795. 10.1002/adma.201303452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang E.; Pruzinsky S.; Russell T. P.; Mays J.; Hawker C. J. Neutrality Conditions for Block Copolymer Systems on Random Copolymer Brush Surfaces. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 5299–5303. 10.1021/ma990483v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giammaria T. J.; Ferrarese Lupi F.; Seguini G.; Sparnacci K.; Antonioli D.; Gianotti V.; Laus M.; Perego M. Effect of Entrapped Solvent on the Evolution of Lateral Order in Self-Assembled P(S-r-MMA)/PS-b-PMMA Systems with Different Thicknesses. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 31215–31223. 10.1021/acsami.6b14332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J.; Suh H. S.; Ko Y.; Nah Y.; Lee J.-C.; Yeom B.; Char K.; Ross C. A.; Son J. G. Universal Perpendicular Orientation of Block Copolymer Microdomains Using a Filtered Plasma. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2912. 10.1038/s41467-019-10907-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samant S.; Strzalka J.; Yager K. G.; Kisslinger K.; Grolman D.; Basutkar M.; Salunke N.; Singh G.; Berry B.; Karim A. Ordering Pathway of Block Copolymers under Dynamic Thermal Gradients Studied by In Situ GISAXS. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 8633–8642. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Kim B.; Xu J.; Hofmann T.; Ocko B. M.; Russell T. P. Lateral Ordering of Cylindrical Microdomains Under Solvent Vapor. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 1278–1284. 10.1021/ma802480s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tschierske C. Liquid Crystal Engineering - New Complex Mesophase Structures and Their Relations to Polymer Morphologies, Nanoscale Patterning and Crystal Engineering. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1930–1970. 10.1039/b615517k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. Photoresponsive Liquid Crystalline Block Copolymers: From Photonics to Nanotechnology. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 781–815. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen B. D.; Gu X.; Hexemer A.; Gann E.; Segalman R. A. Liquid Crystalline Orientation of Rod Blocks within Lamellar Nanostructures from Rod–Coil Diblock Copolymers. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 6531–6534. 10.1021/ma101056r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osuji C.; Ferreira P. J.; Mao G.; Ober C. K.; Vander Sande J. B.; Thomas E. L. Alignment of Self-Assembled Hierarchical Microstructure in Liquid Crystalline Diblock Copolymers Using High Magnetic Fields. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 9903–9908. 10.1021/ma0483064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Li X.; Dong Z.; Huang S.; Yu H. Vertical Orientation of Nanocylinders in Liquid-Crystalline Block Copolymers Directed by Light. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 24864–24872. 10.1021/acsami.7b06086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinadhan M.; Choo Y.; Kawabata K.; Kaufman G.; Feng X.; Di X.; Rokhlenko Y.; Mahajan L. H.; Ndaya D.; Kasi R. M.; Osuji C. O. Controlling Orientational Order in Block Copolymers Using Low-Intensity Magnetic Fields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, E9437–E9444. 10.1073/pnas.1712631114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickmans K.; Bögels G. M.; Sánchez-Somolinos C.; Murphy J. N.; Leclère P.; Voets I. K.; Schenning A. P. H. J. 3D Orientational Control in Self-Assembled Thin Films with Sub-5 nm Features by Light. Small 2017, 13, 1701043. 10.1002/smll.201701043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. T.; Thomas E. L.; Ober C. K.; Mao G. P. Self-Assembled Smectic Phases in Rod-Coil Block Copolymers. Science 1996, 273, 343–346. 10.1126/science.273.5273.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J.; Jiang Y.; Zhang X.; Yan D.; Chen J. Z. Y. Phase Diagram of Rod–Coil Diblock Copolymer Melts. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 9060–9070. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b02235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L.-Y.; Zhou Y.; Fan X.-H.; Shen Z. Remarkably Rich Variety of Nanostructures and Order–Order Transitions in a Rod–Coil Diblock Copolymer. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 5308–5316. 10.1021/ma400944z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L.-Y.; Lee S.; Cheng L.-C.; Huang H.; Liao F.; Ran R.; Yager K. G.; Ross C. A. Thin Film Self-Assembly of a Silicon-Containing Rod–Coil Liquid Crystalline Block Copolymer. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 679–689. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye C.; Zhang H.-L.; Huang Y.; Chen E.-Q.; Lu Y.; Shen D.; Wan X.-H.; Shen Z.; Cheng S. Z. D.; Zhou Q.-F. Molecular Weight Dependence of Phase Structures and Transitions of Mesogen-Jacketed Liquid Crystalline Polymers Based on 2-Vinylterephthalic Acids. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 7188–7196. 10.1021/ma049195b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.-F.; Shen Z.; Wan X.-H.; Fan X.-H.; Chen E.-Q.; Ma Y.; Zhou Q.-F. Mesogen-Jacketed Liquid Crystalline Polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3072–3101. 10.1039/b814540g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur S. M.; Thapar V.; Ramirez-Hernandez A.; Nealey P. F.; de Pablo J. J. Defect Annihilation Pathways in Directed Assembly of Lamellar Block Copolymer Thin Films. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 9974–9981. 10.1021/acsnano.8b04202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavis M. A.; Smilgies D.-M.; Wiesner U. B.; Ober C. K. Widely Tunable Morphologies in Block Copolymer Thin Films through Solvent Vapor Annealing Using Mixtures of Selective Solvents. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 3057–3065. 10.1002/adfm.201404053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton A. F. M. In Handbook of Polymer-Liquid Interaction Parameters and Solubility Parameters; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 1990; pp 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Maripuri V. O.; Ratcliff G. A. Measurement of Isothermal Vapor-Liquid Equilibriums for Acetone-n-Heptane Mixtures Using Modified Gillespie Still. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1972, 17, 366–369. 10.1021/je60054a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterle I. L. J.; Wagner Z.; Fontaine J. C.; Sosnkowska-Kehiaian K.; Kehiaian H. V. In Landolt-Börnstein—Group IV Physical Chemistry; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; pp 1326–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L.-C.; Gadelrab K. R.; Kawamoto K.; Yager K. G.; Johnson J. A.; Alexander-Katz A.; Ross C. A. Templated Self-Assembly of a PS-Branch-PDMS Bottlebrush Copolymer. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 4360–4369. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenneti K. K.; Chen X.; Li C. Y.; Tu Y.; Wan X.; Zhou Q.-F.; Sics I.; Hsiao B. S. Perforated Layer Structures in Liquid Crystalline Rod–Coil Block Copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15481–15490. 10.1021/ja053548k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X.; Gunkel I.; Hexemer A.; Russell T. P. Controlling Domain Spacing and Grain Size in Cylindrical Block Copolymer Thin Films by Means of Thermal and Solvent Vapor Annealing. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 3373–3381. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b00429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paik M. Y.; Bosworth J. K.; Smilges D.-M.; Schwartz E. L.; Andre X.; Ober C. K. Reversible Morphology Control in Block Copolymer Films via Solvent Vapor Processing: An In Situ GISAXS Study. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 4253–4260. 10.1021/ma902646t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y. S.; Ross C. A. Solvent-Vapor-Induced Tunability of Self-Assembled Block Copolymer Patterns. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2540–2545. 10.1002/adma.200802855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y.; Chen W.-C.; Borsali R. Carbohydrate-Based Block Copolymer Thin Films: Ultrafast Nano-Organization with 7 nm Resolution Using Microwave Energy. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1701645. 10.1002/adma.201701645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abetz V.; Stadler R.; Leibler L. Order-Disorder and Order-Order-Transitions in AB and ABC Block Copolymers: Description by a Simple Model. Polym. Bull. 1996, 37, 135–142. 10.1007/BF00313829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates F. S.; Fredrickson G. H. Block Copolymers—Designer Soft Materials. Phys. Today 1999, 52, 32–38. 10.1063/1.882522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.