Abstract

Information processing speed is often altered following a concussion. Few portable assessments exist to evaluate simple reaction time (SRT) in hospitals and clinics. We evaluated the use of a SRT application for mobile device measurement. 27 healthy adults (age = 30.7 ± 11.5 years) completed SRT tests using a mobile device with Sway, an application for SRT testing. Participants completed computerized SRT tests using the Computerized Test of Information Processing (CTIP). Test-retest reliability was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) between Sway trials. Pearson correlations and Bland-Altman analyses were used to assess criterion validity between Sway and CTIP means. ICC comparisons between Sway tests were all statistically significant. ICCs ranged from 0.84 – 0.90, with p-values <0.001. A one-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences between trials (F3,104 = 1.35, p = 0.26. Pearson correlation between Sway and CTIP outcomes yielded a significant correlation (r = 0.59, p = 0.001). The mean difference between measurement methods was 43.7 ms, with limits of agreement between −140.8 – 53.4 ms. High ICC indicates Sway is a reliable method to assess SRT. A strong correlation and clinically acceptable agreement between Sway and the computer-based test indicates that Sway is suited for rapid administration of SRT testing in healthy individuals. Future research using Sway to assess altered information processing in a population of individuals after concussion is warranted.

Keywords: Information processing, assessment, concussion, sports, mobile device

INTRODUCTION

Concussions are difficult injuries for healthcare providers to identify and manage. The challenges in managing individuals following a concussion are in part due to the highly variable symptoms following injury and the lack of objective biomarkers that indicate progression of recovery (Echemendia, Giza, & Kutcher, 2015). Clinical teams are left to determine when an athlete is safe to return to sport even without baseline neurocognitive and functional assessments to measure recovery. The American Medical Society for Sports Medicine recommends all concussion symptoms should be resolved before returning athletes to sport using a step-wise increase in exercise and sports-specific activities (Harmon et al., 2013). Without objective tests evaluating an athlete’s current functioning to pre-injury status, sports medicine clinicians must rely on subjective symptom assessment, which may lead to underestimating full recovery (Makdissi et al., 2010). However, prematurely returning athletes back to play before full recovery poses serious risk for further brain injury (Wetjen, Pichelmann, & Atkinson, 2010).

Slowed information processing abilities are common after a concussion (Warden et al., 2001). Changes in a person’s ability to react quickly to external stimuli has important prognostic utility, as slow simple reaction times after concussion have been correlated with a longer time needed to recover of function (Norris, Carr, Herzig, Labrie, & Sams, 2013). Slowed reaction time can persist even after athletes report physical symptoms have resolved (Warden et al., 2001). Assessing reaction time may help prevent premature return to play recommendations and thus limit the potential for further neurological injury.

Many different clinical tests of reaction time exist, although most require computerized programs and specialized equipment. An exception was developed by Eckner et al. required no specialized equipment, being a measuring stick coated in high friction tape and embedded in a weighted rubber disk (Eckner, Kutcher, & Richardson, 2010). The device is released by the tester and caught as quickly as possible by the subject. Although equipment for this test is easily obtainable and affordable, the test itself has low between season test-retest reliability (Eckner, Kutcher, & Richardson, 2011) and poor validity (MacDonald et al., 2014).

Mobile devices may provide clinical teams with a readily accessible alternative for objective evaluation of reaction time. Many mobile devices now contain tri-axial accelerometers used by downloadable applications (apps) created for a variety of clinical uses. The Sway app (Sway Medical, Tulsa, OK) quantifies a person’s ability to react by collecting acceleration data from device movement during motion-based movement tests. However, establishing the reliability and validity of mobile device apps for use in reaction time assessment is essential prior to more wide-spread adoption of this technology in clinical settings.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the ability of Sway to measure accurate reaction times in healthy individuals using the mobile device’s tri-axial accelerometer. The first aim of this study was to determine the reliability Sway reaction time tests across a series of repeated trials conducted during the same testing session. The second aim of the study was to assess validity of reaction time data collected by Sway relative to a computerized standard reaction time test. We hypothesized that Sway would demonstrate good test-retest reliability, and that Sway reaction times and computer-based reaction times would show strong correlation coefficients.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty-seven healthy volunteers between the ages of 18 and 60 were recruited from a public university’s medical center and participated in the study. Individuals reporting known orthopedic, musculoskeletal, or neurologic injury in the prior 6 months were excluded. All subjects reported they had not consumed substances or medications prior to testing that may affect reaction times during the study. All subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation in accordance with requirements for this study set forth by the Institutional Review Board.

Outcome Measures

The Sway app (version 2.1.1) was downloaded from the Apple App Store® and installed on the mobile devices used for simple reaction time (SRT) testing (Apple iPod Touch 5th Gen, iOS Version 7.1, Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA). Sway is an FDA-approved app for assessing balance using the integrated tri-axial accelerometers of mobile devices. The original balance-only version of the testing protocol was modified to include a simple reaction time protocol by having subjects tilt the device in response to a change in screen color. Sway records this movement by sampling the acceleration data at a frequency of 1000 Hz during each trial. Sway determines a latency response time at the end of each trial, which is the difference in time between the color change and the onset of user-initiated tilt of the mobile device. Each test block consisted of 5 trials, with randomized between-trial pauses to prevent the user anticipating when to respond to the stimulus. A mean Latency Response Time was calculated across the 5 trials. Each subject performed four test blocks (4 × 5 trials).

The Computerized Test of Information Processing (CTIP, Version V.5 software kit, PsychCorp, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) was used for SRT method comparison. The CTIP software was installed on a desktop PC (Hewlett Packard Compaq 8200 Elite, Hewlett Packard Company, Palo Alto, CA). The CTIP software has been used to assess information processing abilities in individuals with brain injury (Tombaugh, Rees, Stormer, Harrison, & Smith, 2007) and multiple sclerosis (Reicker, Tombaugh, Walker, & Freedman, 2007; Tombaugh, Berrigan, Walker, & Freedman, 2010). The CTIP test has shown to be sensitive to the information processing changes taking place after brain injury and is used to clinically discriminate between uninjured and mild brain injury patients (Willison & Tombaugh, 2006). The software contains 3 different reaction time assessments: Simple reaction time, choice reaction time, and semantic reaction time (Tombaugh et al., 2007). The simple reaction time subtest of the CTIP was used for comparison to Sway SRT trials.

Procedures

Prior to SRT testing, demographic information was obtained. Participants were seated in a comfortable and upright position, while holding the mobile device with both hands. Participants read on-screen instructions to react to changes in the screen color by quickly shaking the device. Researchers verified each participant’s understanding of on-screen instructions and visually demonstrated the appropriate shaking motion. Participants then performed SRT test blocks using Sway. Each participant completed 4 SRT test blocks while seated, with each test block including 5 separate trials. Twenty total trials for each participant were used to evaluate both test-retest reliability and learning/fatigue effects after repeated measures. Latent response times were recorded in milliseconds (ms). Participants rested for 2 minutes between each test.

After completing the 4 Sway tests, participants then completed the SRT subtest from the CTIP. Participants were seated comfortably in front of a computer screen and were instructed to react as quickly as possible to randomly-timed visual stimulus changes, represented by a large ‘X’ appearing on the computer monitor. Participants were instructed to react by clicking the spacebar on the computer’s keyboard with their dominant hand’s index finger. Participants were given 10 practice trials to familiarize themselves with the test procedure, per the CTIP SRT test protocol (Tombaugh et al., 2007). Following the practice trials, subjects completed total 30 trials. Latent response times were recorded in ms. Each complete session lasted between 10 and 15 minutes.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R, a statistical computing language (version 3.4.1). First, data was screened for any potential outliers resulting from technical errors. Sway reaction time results for each test block were averaged together for use in reliability testing, using an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (3,k). Learning and fatigue effects from repeated Sway tests were evaluated using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare differences in mean reaction times across trials. SRT outcomes from each participant’s Sway and CTIP tests were averaged separately for validity testing. Agreement of the two SRT measurement methods was assessed with Bland-Altman analysis and descriptions of the limits of agreement (Bland & Altman, 1986). Pearson product-moment correlations coefficients were calculated to assess criterion validity and the strength of association between Sway and CTIP reaction time test means. Lastly, a post hoc power analysis was conducted to report the achieved power of the Pearson product moment correlation test. Inferential statistics were tested at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Twenty-seven participants were included in the study. The 27 subjects (12 men, 15 women) ranged in age from 18 to 59 years, with a mean age of 30.96 years (SD = 12.07). The mean Sway reaction time from participants was 284.31 ms (range: 185.50 – 450.25 ms). The mean CTIP reaction time from participants was 328.01 ms (range: 242.40 – 452.50 ms).

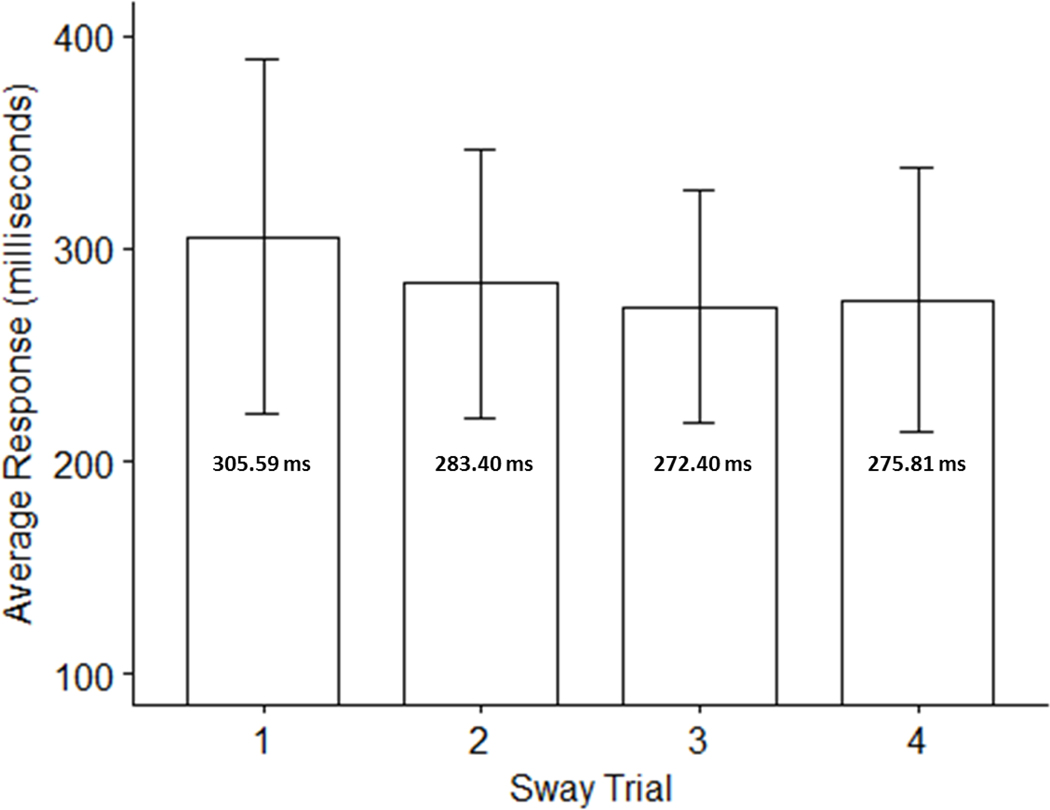

Results from Sway SRT trials are presented in Table 1. The ICC comparisons demonstrated significant reliability during repeated measurements for Sway tests (ICC = 0.713, p <0.001, 95% CI = 0.56 – 0.84). A one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine whether there were statistically significant differences in Sway reaction times over the course of the 4 trials, assessing for learning and fatigue effects. Comparison of reaction times across trials did not yield statistically significant differences in reaction times (Figure 1; F3,104 =1.35, p = 0.26).

TABLE 1:

Sway SRT results across trials

| Sway Trial | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Trial 1 | 305.59 ms (83.50) | 161.00 – 527.00 |

| Trial 2 | 283.40 ms (63.32) | 184.00 – 470.00 |

| Trial 3 | 272.41 ms (54.72) | 190.00 – 409.00 |

| Trial 4 | 275.81 ms (62.08) | 202.00 – 445.00 |

ms = milllseconds; SD = standard deviation; SRT = simple reaction time;

Figure 1:

Mean Sway motion-based reaction times across trials No statistically significant differences between trials were noted (F3,104 =1.35, p = 0.26).

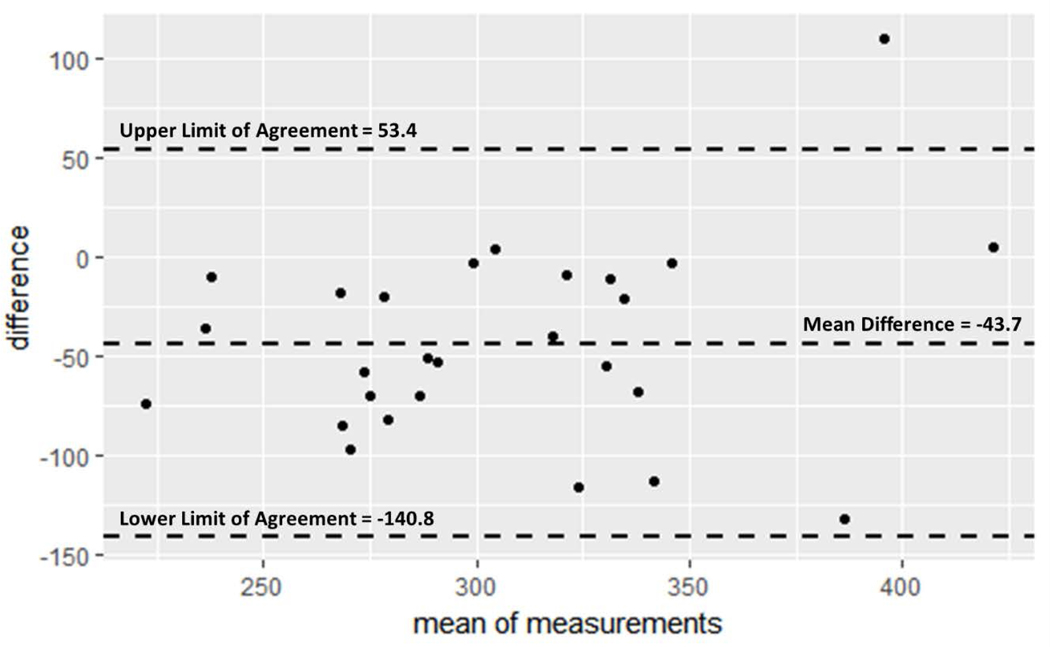

Agreement between Sway and CTIP as a method for SRT measurement was assessed via Bland-Altman analysis. The mean difference between pairwise Sway and CTIP results was −43.7 ms, again indicating Sway results were faster in nature. The Bland-Altman limits of agreement, represented by the mean difference d ± 1.96 standard deviations (SD), were −140.8 ms to 53.4 ms. Bland-Altman results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Bland-Altman plot with limits of agreement Average CTIP results were subtracted from average Sway results, yielding the ‘difference’ value plotted on the y axis. Mean of measurements on x axis represent the average pairwise value obtained from the two measures. Limits of agreement were calculated by taking the mean difference ± 1.96 SD. See Bland & Altman (1986) further detail. Both measures used milliseconds.

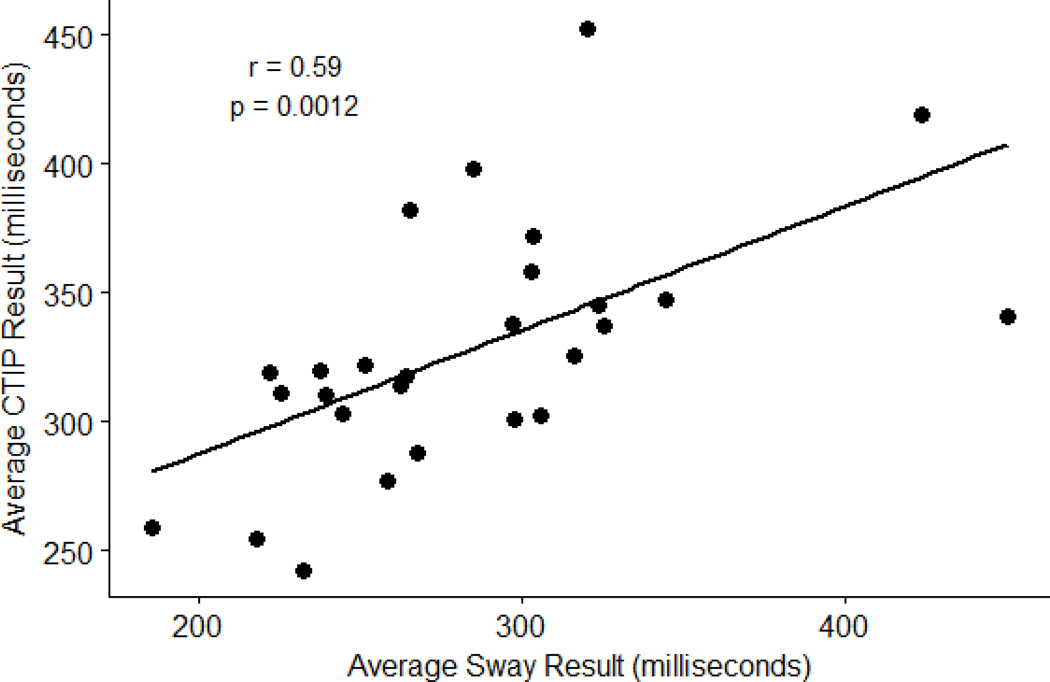

Criterion validity was assessed by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients between mean Sway and CTIP reaction tests (Figure 3). Participants had an average response time of 284.31 ± 59.10 ms, while average response time on CTIP test were 328.01 ± 48.12 ms. The Sway app was positively correlated with the CTIP test [r (25) = 0.590, p = 0.001]. A post-hoc power analysis was conducted and returned an observed power of 0.96 (n = 27, α < 0.05, effect size = 0.59).

Figure 3:

Pearson Correlation results between Sway and CTIP tests CTIP = Computerized Test of Information Processing; r = Pearson Correlation Coefficient; p = p-value.

DISCUSSION

Establishing reliability and validity of an assessment is vital to ensure clinical interpretation is appropriate and trusted. Our study evaluated Sway, a mobile device app, to measure reaction time in healthy individuals. Our first aim assessed the test re-test reliability of Sway reaction time tests repeated over time. While there is a noticeable decrease in mean response times after the first trial, we found no statistically significant differences between the trials. We attribute the difference in means to a possible learning effect, as the subsequent trials required less time overall. The current testing procedures described by Sway did not include a practice trial to allow the person to acclimate to the motion-based assessment, and thus, clinicians should consider multiple test trials to reach accurate SRT consensus.

The second aim of the study assessed criterion validity of motion-based SRT measurement by examining the relation of data collected by Sway and computerized reaction time tests. We found a moderate positive correlation between means produced from the Sway app and CTIP results. Eckner et al (2010) compared computerized reaction time assessment with a novel clinical reaction time test and found a significant correlation (r = 0.445, p < 0.001). Similarly, MacDonald et al (2014) assessed the same method in a younger population and found a weaker correlation (r = 0.229, p < 0.001). It should be noted that while the correlations were significant (p < 0.05), the statistic of interest for correlational analysis is the Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficient (Mukaka, 2012). While the magnitude of the strength of association should always be considered with the context of data, the coefficients produced in the previous studies signify a fair relationship (Portney & Watkins, 2009). Our study produced a stronger association and can be classified as a moderate to good relationship.

Additionally, we sought to assess the agreement between the two SRT measurement methods via the popular Bland-Altman analysis. While these two methods appear to agree well, there are some notable differences. First, the mean difference between the two methods as −43.7 ms, which should be accounted for if these two methods need a direct comparison. For instance, adding 43.7 ms to an individual’s Sway result could produce a reliable comparison to an expected CTIP in this sample. Second, all but one pairwise difference fell outside the limits of agreement, thus providing evidence for agreement between these two measurement methods. Lastly, the limits of agreement range spans nearly 200 milliseconds (−140.8, 53.4). In the context of concussion assessment, this range is acceptable for clinical interpretation of SRT. This range of agreement should be considered when considering Sway for clinical use in alternative settings.

Our results should be considered with several limitations. First, our procedures assessed healthy non-athletes in an isolated laboratory environment. This established a controlled setting to assess the Sway application, and we acknowledge testing athletes in busy sporting environments is drastically different. Additionally, randomization of measurement order did not occur. Future work should randomize testing order of participants to evaluate measurement order effects. We also evaluated the Sway application on a single type of mobile device. Clinicians in the field may have access to other products for testing purposes and our results may not generalize to these other mobile devices. Finally, we evaluated a total of 27 healthy individuals, a relatively small and homogenous sample. However, despite the small sample size, our study was adequately powered to detect a significant effect. Future studies now have justification for including a larger, diverse population to verify the generalizability of these present findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study found the Sway application to be a valid and reliable tool for assessing SRT in healthy adults in a controlled environment. While these results are promising, continued research in non-laboratory settings and across a diverse population is needed prior to regular use of Sway in clinical settings.

Acknowledgements:

This project was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society RG 4914A1/2 and the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Science 1KL2TR00011. Sway Medical, LLC. donated access to the SWAY application and database.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Bland JM, & Altman D. (1986). Statistical Methods for Assessing Agreement Between Two Methods of Clinical Measurement. The Lancet, 327(8476), 307–310. 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echemendia RJ, Giza CC, & Kutcher JS. (2015). Developing guidelines for return to play: Consensus and evidence-based approaches. Brain Injury, 29(2), 185–194. 10.3109/02699052.2014.965212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckner JT, Kutcher JS, & Richardson JK. (2010). Pilot evaluation of a novel clinical test of reaction time in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I football players. Journal of Athletic Training, 45(4), 327–332. 10.4085/1062-6050-45.4.327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckner JT, Kutcher JS, & Richardson JK. (2011). Between-Seasons Test-Retest Reliability of Clinically Measured Reaction Time in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Athletes. Journal of Athletic Training, 46(4), 409–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon KG, Drezner JA, Gammons M, Guskiewicz KM, Halstead M, Herring SA, … Roberts WO. (2013). American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine, 23(1), 1–18. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald J, Wilson J, Young J, Duerson D, Swisher G, Collins C, & Meehan WP. (2014). Evaluation of a Simple Test of Reaction Time for Baseline Concussion Testing in a Population of High School Athletes. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine, 25(1), 43–48. 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000096.Full [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makdissi M, Darby D, Maruff P, Ugoni A, Brukner P, & McCrory PR. (2010). Natural History of Concussion in Sport. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 38(3), 464–471. 10.1177/0363546509349491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukaka MM. (2012). Statistics corner: A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Medical Journal, 24(3), 69–71. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris JN, Carr W, Herzig T, Labrie DW, & Sams R. (2013). ANAM4 TBI Reaction Time-Based Tests Have Prognostic Utility for Acute Concussion. Military Medicine, 178(7), 767–774. 10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portney LG, & Watkins MP. (2009). Correlation In Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice (3rd ed., pp. 523–538). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. [Google Scholar]

- Reicker LI, Tombaugh TN, Walker L, & Freedman MS. (2007). Reaction time: An alternative method for assessing the effects of multiple sclerosis on information processing speed. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 22(5), 655–664. 10.1016/j.acn.2007.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN, Berrigan LI, Walker LAS, & Freedman MS. (2010). The Computerized Test of Information Processing (CTIP) Offers an Alternative to the PASAT for Assessing Cognitive Processing Speed in Individuals With Multiple Sclerosis. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, 23(3), 192–198. 10.1097/WNN.0b013e3181cc8bd4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN, Rees L, Stormer P, Harrison AG, & Smith A. (2007). The effects of mild and severe traumatic brain injury on speed of information processing as measured by the computerized tests of information processing (CTIP). Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 22(1), 25–36. 10.1016/j.acn.2006.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warden DL, Bleiberg J, Cameron KL, Ecklund J, Walter J, Sparling MB, … Arciero R. (2001). Persistent prolongation of simple reaction time in sports concussion. Neurology, 57(3), 524–526. 10.1212/WNL.57.3.524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetjen NM, Pichelmann MA, & Atkinson JLD (2010). Second impact syndrome: Concussion and second injury brain complications. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 211(4), 553–557. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willison J, & Tombaugh TN. (2006). Detecting simulation of attention deficits using reaction time tests. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 21(1), 41–52. 10.1016/j.acn.2005.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]