Abstract

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with autism spectrum disorder, used interchangeably with the term autism, are among the most marginalised people in Australian society. This review maps out existing and emerging themes in the research involving Indigenous Australians with autism based on a search of the peer-reviewed and grey literature. Our search identified 1457 potentially relevant publications. Of these, 19 publications met our inclusion criteria and focused on autism spectrum disorder diagnosis and prevalence, as well as carer and service provider perspectives on autism, and autism support services for Indigenous Australians. We were able to access 17 publications: 12 journal articles, 3 conference presentations, 1 resource booklet and 1 dissertation. Findings suggest similar prevalence rates for autism among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, although some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with autism may not receive a diagnosis or may be misdiagnosed. Research on the perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers and Indigenous and non-Indigenous service providers is discussed in relation to Indigenous perspectives on autism, as well as barriers and strategies to improve access to diagnosis and support services. Although not the focus of our review, we briefly mention studies of Indigenous people with autism in countries other than Australia.

Lay Abstract

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with developmental disabilities such as autism are among the most marginalised people in Australian society. We reviewed research involving Indigenous Australians with autism based on a search of the peer-reviewed and grey literature. Our search identified 1457 potentially relevant publications. Of these, 19 publications were in line with our main areas of inquiry: autism spectrum disorder diagnosis and prevalence, carer and service provider perspectives on autism, and autism support services. These included 12 journal publications, 3 conference presentations, 1 resource booklet and 1 thesis dissertation. Findings suggest similar prevalence rates for autism among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, although some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with autism may not receive a diagnosis or may be misdiagnosed. We also discuss research on the perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers and Indigenous and non-Indigenous service providers, as well as barriers and strategies for improving access to diagnosis and support services.

Keywords: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, Australia, autism, autism spectrum disorder, Indigenous

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), used interchangeably with the term autism, is an early onset neurodevelopmental disability characterised by difficulties with social communication coupled with restrictive and repetitive patterns of behaviour or interests (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 5th edition also referred to as DSM-V; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). People with autism are heterogeneous within and beyond these core characteristics, although many individuals exhibit comorbid difficulties in language and learning as well as challenging behaviours (e.g. Armstrong & Jokel, 2012; Baird et al., 2006; Kjelgaard & Tager-Flusberg, 2001). These factors impact early development and can limit daily living, as well as educational, health, social and economic outcomes (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015; Autism Spectrum Australia, 2013; Charman et al., 2011; Gray et al., 2014; Happé et al., 2006; Howlin & Moss, 2012; Tager-Flusberg et al., 2005; Vivanti et al., 2013).

Programmes aimed at enhancing outcomes for individuals with autism emphasise the importance of early intervention (e.g. Koegel et al., 2014; Rogers et al., 2019). However, the opportunity for early intervention is sometimes diminished by adverse social and environmental factors. This is evident in disadvantaged populations, including some Indigenous Australian communities. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are subject to marginalisation brought about by the European invasion of Australian lands in 1788, and the subsequent rolling frontier, and perpetuated by the policies of dispossession and displacement instituted by Australian governments (see Hollinsworth, 2013). At present, Indigenous Australians are among the most disadvantaged people in Australia, with disparities in socio-economic status contributing to a significant gap in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017). This divide is exacerbated by disparities in educational attainment and access to health services (Ou et al., 2010).

The disparity in Indigenous and non-Indigenous health extends to disability. Indigenous Australians experience disability at a rate more than 1.5 times that of the general Australian population and are twice as likely to have a severe or profound form of disability (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2015; Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, 2014). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with a disability are also less likely to access support than other Australians (Gilroy et al., 2013). This inequity means that Indigenous Australians with autism might experience poorer long-term outcomes as compared with non-Indigenous Australians with autism.

The current study

This review was conducted to map the key themes in the research on Indigenous Australians with autism. Our search considered both the peer-reviewed and grey literature to capture existing and emerging research in this field. In addition to providing an overview of the literature, our intention in conducting this review was to identify priorities for future research based on the experiences and perspectives of Indigenous Australians and the service providers that support them.

Method

The methodology for this study was based on the scoping review framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and later enhanced by Levac et al. (2010). This incorporates five distinct phases: (1) development of the research questions, (2) identification of relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting of data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting results. A sixth optional phase of the scoping review, stakeholder consultation, was not undertaken as part of our review.

Development of research questions

An initial Google Scholar search was conducted using ‘Indigenous Australians’ and ‘autism’, and related terms, to identify research on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with autism. The available publications that focused specifically on Indigenous Australians with autism were reviewed and informed development of the following research questions:

What is known about autism diagnosis and prevalence in Indigenous Australian communities?

What is known about how autism is perceived by Indigenous Australians?

What is known about autism diagnosis and support services for Indigenous Australians?

Identification of relevant studies

A keyword search was begun on 22 January 2019 using the Web of Science, PubMed, PsycINFO, ERIC, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, ATSIHealth and APAIS–ATSIS databases. Search terms pertaining to autism (autism OR autistic OR Asperger OR ASD OR PDD) were combined with terms relating to Indigenous peoples (Indigenous OR Aboriginal OR Aborigine OR Torres Strait OR First Nation OR First People). The search was not limited by date, language, subject or publication type.

A search of the grey literature was begun on 28 January 2019. This involved a manual search of the following websites associated with Indigenous Australian and autism organisations: Lowitja Institute, First Peoples Disability Network, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia, Autism Cooperative Research Centre (Autism CRC), Menzies School of Health Research, Poche Indigenous Health Network and Australian Indigenous Psychologists Association. A manual search of proceedings from the following conferences was then completed: National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation Conference, National Indigenous Research Conference, National Aboriginal Wellbeing Conference, Indigenous Allied Health Association National Forum, Aspect Autism in Education Conference and Australasian Society for Autism Research Conference.

Journals with a focus on indigenous health and education were searched individually using the above-mentioned keywords relating to autism (autism OR autistic OR Asperger OR ASD OR PDD). These journals included Indigenous Australia, Australian Aboriginal Studies, The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, Aboriginal Quarterly, Journal of Aboriginal Health, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Information Bulletin. As a final step, reference lists in publications identified as relating to the research questions were searched for other relevant publications.

Study selection

The authors discussed inclusion/exclusion criteria and screening methods following the initial literature search. It was agreed that relatively broad inclusion criteria would be used to consider all publications with reference to autism and Indigenous Australians. Research on autism involving other Indigenous populations was also considered; however, given the focus on Indigenous Australians, we provide only brief mention of these publications. We sought to include publications of all types (journal articles, conference presentations, reports, books or booklets) provided they included some discussion of autism and Indigenous Australians. Publications relating to Indigenous people and disability more generally which mentioned one or more of the ‘autism’ search terms noted in the previous section were also included.

Screening involved a two-step process. Publication titles and abstracts were first screened by the first author to determine relevance to the topics of autism and Indigenous populations. Publications were then read in full in the second step of the screening process to further evaluate relevance to the research questions.

Charting the data

A standard coding form was developed to assist in data extraction. It included sections designed to derive information regarding research topic, title information, publication type, research design and aims, sample characteristics and key findings.

Collating, summarising and reporting results

Publications fell into three categories: (1) previous systematic reviews, (2) autism diagnosis and prevalence in Indigenous Australian communities and (3) carer and service provider perspectives. We did not formally appraise methodological rigour given our aim of mapping the main themes in the research on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with autism. However, we have outlined some gaps in the research in our ‘Discussion’.

Community involvement statement

The first author of the current review has Aboriginal heritage. Other than this, no Aboriginal researchers were consulted when we undertook our review. However, we have emphasised Aboriginal voices by adding an extensive Appendix with quotes from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants involved in the primary studies included in our review. In addition, we presented the results of our review at the recent Lowitja Institute International Indigenous Health and Wellbeing Conference in Darwin, Australia, and sought feedback from Aboriginal researchers (Bailey & Arciuli, 2019). We have adhered to guidelines set by Aboriginal researchers in the writing of this article (Bond et al., 2019). Readers are encouraged to familiarise themselves these guidelines at https://indigenousx.com.au/.

Results

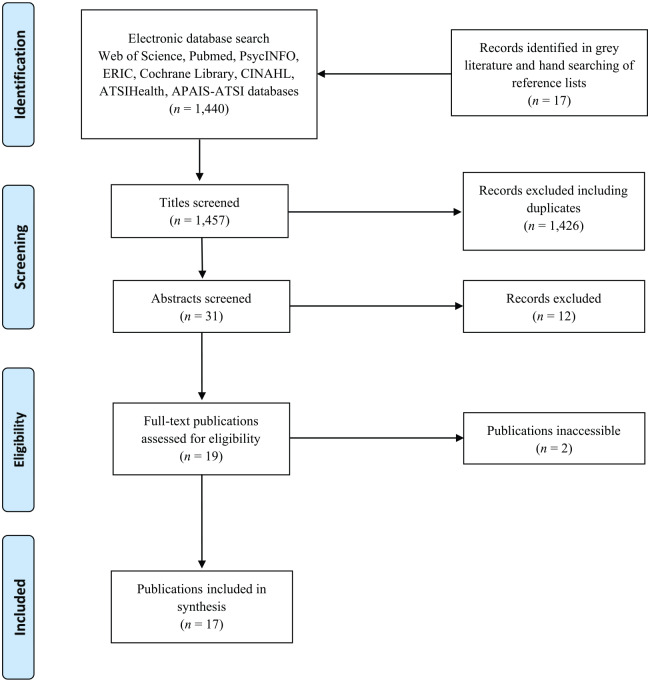

Keyword searches identified a total of 1440 potentially relevant records. An additional 17 titles were identified via a search of the grey literature and a manual search of reference lists. No further publications were found through a manual search of journals known to publish research on Indigenous health and education. After removing duplicates, 31 titles were identified as potentially relating to the topics of autism and Indigenous populations. Abstracts for these publications were reviewed, and a further 12 titles excluded on the basis of focusing on populations other than Indigenous Australians (n = 11) or disabilities other than autism (n = 1). Full text documents could not be accessed for two titles despite efforts to contact the authors (Nogrady, 2008; O’Brien & White, 2014). Results for the search strategy are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of search strategy based on PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1 provides an overview of publication characteristics for the 17 titles included in the review. All but one of the works were published between 2010 and 2018, with a median publication date of 2015. Eight titles (47.06%) were published in the 3 years leading up to the time of writing (2016–2019), marking an increase in research including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with autism in recent times.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included publications.

| Characteristic | Number (n = 17) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Year | ||

| <2009 | 1 | 5.88 |

| 2010–2015 | 8 | 47.06 |

| 2016–2019 | 8 | 47.06 |

| Type | ||

| Journal article | 12 | 70.59 |

| Conference presentation | 3 | 17.65 |

| Thesis dissertation | 1 | 5.88 |

| Booklet | 1 | 5.88 |

| Design/method | ||

| Review | 3 | 17.65 |

| Quantitative | 4 | 23.53 |

| Qualitative | 9 | 52.94 |

| Mixed | 1 | 5.88 |

The search uncovered previous literature reviews and original research on ASD diagnosis and prevalence, as well as the perspectives of carers and service providers for Indigenous Australians with autism. An overview of study methods and key findings are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of methods and findings.

| Topic Authors (year) |

Sample | Methods | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous reviews on Indigenous Australians with autism | |||

| Wilson and Watson (2011) | 3 peer-reviewed journal articles | No formal search procedure. Narrative synthesis | • Limited research on Indigenous Australians with autism |

| Green et al. (2018) | 13 peer-reviewed journal articles 18 grey literature publications |

Systematic integration literature review and narrative synthesis | • Factors in cross-sector collaborations identified at the levels of: (1) government departments, agencies, and policies; (2) communication, financial and human resources, and service delivery; and (3) relationships and intra-professional learning |

| Bennett and Hodgson (2017) | 2 peer-reviewed journal articles | Key word search and narrative synthesis | • Limited research on Indigenous Australians with autism |

| Autism diagnosis and prevalence | |||

| Roy and Balaratnasingam (2010) | 14 Indigenous adults | Developmental history and psychiatric assessment to investigate instances of suspected missed autism diagnosis | • Of 14 adults identified as having an unclear diagnosis of schizophrenia and suspect development, 13 met DSM-IV criteria for autism |

| Leonard et al. (2011) | 393,329 children in Western Australia born between 1984 and 1999 | Univariate analyses to investigate links between socio-demographic characteristics and autism | • Indigenous mothers significantly less likely to have a child diagnosed with autism as compared to Caucasian mothers |

| Graham (2012) | ‘Schools Locator’ database and ‘My School’ website | Enrolments in support schools/total enrolments compared across Indigenous and non-Indigenous students | • Indigenous children equally represented in schools for children with autism Indigenous children significantly over-represented in schools for ‘specific purposes’ |

| Bent et al. (2015) | 15,074 children receiving support through the HCWAP | Mann–Whitney U tests to compare age of diagnosis across Indigenous and non-Indigenous children | • No difference in age of diagnosis between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children Smaller proportion of Indigenous children with Asperger’s syndrome |

| Carer and service provider perspectives | |||

| Casuscelli and Reimer (2017) | Service providers from Positive Partnerships and the First Peoples Disability Network | Project to improve awareness and understanding of autism | • Strategies and materials to improve service access based on the ‘Aboriginal 8 ways of learning’ |

| McDonald and Zetlin (2004) | Service providers from various disability organisations | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups | • Limited awareness of autism Barriers to diagnosis Barriers to support |

| Higgins and Beecher (2010) | Parents and service providers from 20 Indigenous child care centres | Interviews. No formal procedure reported | • Limited awareness of autism Variability in perception of autism Barriers to diagnosis Barriers to support Strategies to improve service access |

| DiGiacomo et al (2013) | 17 service providers and 5 carers of Indigenous children with disabilities | Community forums | • Barriers to diagnosis Barriers to support Strategies to improve service access |

| Green et al. (2016) | 19 carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with disabilities | Semi-structured interviews | • Limited awareness of autism Barriers to support Strategies to improve service access |

| DiGiacomo et al. (2017) | 19 carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with disabilities | Semi-structured interviews | • Barriers to support Strategies to improve service access Impacts on carer health and well-being |

| Green et al. (2018) | 19 carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with disabilities | Semi-structured interviews | • Barriers to support Strategies to improve service access Carers’ experiences with service providers |

| Lilley et al. (2018) | 11 carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with autism | Semi-structured interviews | • Barriers to support Strategies to improve service access Carers’ experiences with diagnostic pathways |

| Positive Partnerships (2018) | 10 carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with autism | Written submission, face-to-face and telephone interview | • Limited awareness of autism Variability in perception of autism across communities Strategies to improve service access Perceived benefits of diagnosis |

| Green (2018) | 24 service providers in Western Sydney | Semi-structured interviews | • Barriers to diagnosis Barriers to support Strategies to improve service access |

Reviews on Indigenous Australians with autism

The search strategy identified three previous reviews of the literature on Indigenous Australians with autism. Two of the reviews focused specifically on research involving children with autism (Bennett & Hodgson, 2017; Wilson & Watson, 2011), while the remaining study considered research involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with disabilities more generally, including those with autism (Green et al., 2014).

A brief paper by Wilson and Watson (2011) provided a commentary and extension on a key word search conducted by Nogrady (2008). Few details were provided regarding the original search by Nogrady;1 however, it was noted that search terms included ‘autism’ and ‘Indigenous populations’. This strategy identified a total of 17 journal articles, only one of which related to the target topic of Indigenous Australians with autism (McDonald & Zetlin, 2004; see below for details). An updated review of the literature was conducted by Bennett and Hodgson (2017), this time using a formal search strategy and published as a Letter to the Editor. Key word searches of the Google Scholar and PubMed databases, dated 18 December 2015, were completed using the terms ‘Indigenous’ OR ‘Aboriginal’ combined with ‘autism’. The strategy identified only two relevant titles – the journal article by Roy and Balaratnasingam (2010) and the review by Wilson and Watson (2011). The authors highlighted continued lack of progress in research with Indigenous Australians with autism, and issued a repeated call for greater resources and attention to be directed towards this area.

Taking a different approach, Green et al. (2014) completed a review of the literature on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with all disabilities, including but not limited to autism. The review, published as a full-length article, focused on issues related to cross-sector collaborations in the delivery of disability support services. A key word search was conducted using electronic databases, followed by a manual search of reference lists and of the grey literature. These identified 31 relevant titles, including 13 peer-reviewed articles and 18 publications from the grey literature. Findings revealed factors affecting service delivery at the government, organisational and carer and service provider levels. Carers and service providers specified the siloed structure of government departments and agencies as one of the primary barriers and suggested that a more consultative approach could assist in developing services that meet the needs of Indigenous children. Other organisational factors that were identified included the use of Aboriginal health and education workers to facilitate and maintain links between support services and Indigenous communities. It was noted that building collaborative relationships with families and the broader community ensures best outcomes for Indigenous people with disabilities.

ASD diagnosis and prevalence in Indigenous Australian communities

Four studies examined issues related to ASD diagnosis and prevalence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (Bent et al., 2015; Graham, 2012; Leonard et al., 2011; Roy & Balaratnasingam, 2010). These were all peer-reviewed journal articles.

Roy and Balaratnasingam (2010) examined potential cases of missed ASD diagnosis in a caseload of Indigenous adults previously diagnosed with schizophrenia. Participants were 215 patients accessing services at the Kimberley Mental Health and Drug Service in Western Australia. Fourteen participants were identified as having an unclear diagnosis of schizophrenia and a suspected history of developmental difficulties. Of these, 13 patients (93%) met criteria for ASD, as per guidelines from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). These findings suggest phenotypical similarities between schizophrenia and ASD, and highlight the usefulness of developmental history in differentiating these disorders. The results also provide an indication that Indigenous Australians with ASD may be misdiagnosed.

A larger-scale study by Leonard et al. (2011) investigated ASD diagnosis for Australians more generally, including prevalence in Indigenous communities. Using the Western Australia Data Linkage System, demographic information was obtained for all children born in Western Australia between 1984 and 1999 (n = 393,329). Analyses showed that Indigenous mothers were significantly less likely than non-Indigenous mothers to have a child diagnosed with ASD. The authors interpreted this finding as reflecting inequities in access to diagnostic services, partly on the basis of previous research involving other minority groups, such as Hispanic children living in the United States (Palmer et al., 2010).

Graham (2012) also investigated issues related to ASD diagnosis and prevalence for Indigenous Australians. In this study, data were drawn from the New South Wales Department of Education and Training ‘Schools Locator’ database and ‘My Schools’ website. Information obtained using these sources showed that Indigenous children comprised approximately 5.5% of all school enrolments but more than 13% of enrolments in schools for specific purposes (SSPs). These included schools for children with low incidence disabilities such as autism (traditional SSPs), schools for children with mental health difficulties (mental health SSPs) and schools for children in the juvenile justice system (juvenile justice SSPs). Further analyses revealed that the overrepresentation of Indigenous children was driven by enrolments in mental health and juvenile justice SSPs. These results suggest that ASD may be similarly prevalent among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Bent et al. (2015) examined the prevalence of ASD in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities using Australian government statistics collected as part of the Helping Children with Autism Package (HCWAP). This scheme was available to all Australian children under 7 years of age with a confirmed diagnosis of ASD. Consistent with earlier studies, analyses showed no significant difference in the age of ASD diagnosis for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. However, Indigenous children were significantly underrepresented in the subgroup of participants diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome as per the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), differentiated from other forms of autism by the absence of language impairment and no delay in cognitive development or age-appropriate self-help skills or adaptive behaviour. This indicates that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with autism may be less likely to receive a diagnosis if they are less severely affected.

Carer and service provider perspectives

Ten publications in the review explored Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carer and service provider perspectives. Three conference presentations and a booklet focused specifically on the perspectives of carers and service providers involved in supporting children with autism (Casuscelli & Reimer, 2017; Higgins & Beecher, 2010; Lilley et al., 2018; Positive Partnerships, 2018). The remaining five peer-reviewed journal articles and thesis considered the perspectives of carers and service providers involved in supporting children with disabilities, including but not limited to autism (DiGiacomo et al., 2013, 2017; Green, 2018; Green et al., 2016, 2018; McDonald & Zetlin, 2004). Key themes identified in these studies included Indigenous perspectives on autism and other disabilities, as well as barriers and strategies to improve access to diagnostic and support services. Examples of carer and service provider comments related to these themes are provided in Appendix 1.

Carers and service providers of children with autism

Higgins and Beecher (2010) examined the perspectives of carer and service providers from 20 child care centres across Australia participating in the Early Days Project (www.autismspectrum.org.au/content/early-days). Carers reported on barriers to service provision, including the influence of racism and a lack of awareness of autism in some communities. Community support, especially that from extended family, was a key protective factor. Service provider interviews focused on increasing service uptake, highlighting regular communication and development of provider–user relationships as key opportunities to improve service delivery. Caution was encouraged regarding the use of the word ‘autism’ as some families can be hesitant to assign diagnostic labels. Differences in family and community structure were also noted as important considerations. For example, inviting extended family or other community members to information sessions and assessments may be appropriate in some instances.

Lilley et al. (2018) summarised preliminary findings from 11 interviews involving carers from across Australia, many of whom had a pre-existing relationship with the Positive Partnerships Program (http://www.positivepartnerships.com.au). Carers acknowledged gaps in community members’ understanding of autism and a distrust of medical labels. Some expressed acceptance of children’s ‘unusual’ characteristics as part of who they are rather than symptoms requiring remediation. Consistent with participants in Higgins and Beecher (2010), community connection was identified as an important factor, with some carers expressing feelings of social isolation. Carers reported difficulties obtaining appropriate school placements and instances of bullying and restrictive classroom practices. Recommendations for improving service provision included ensuring providers complete training in cultural competency, that Aboriginal and Strait Islander people be employed across service provider settings to assist in addressing cultural issues, that providers are flexible around service delivery, and that autism awareness training be offered to local Indigenous communities.

Casuscelli and Reimer (2017) outlined a collaboration again involving Positive Partnerships, and the First Peoples Disability Network, a national organisation which aims to engage and advocate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability. This project set out to develop culturally respectful and relevant materials and approaches to promote awareness and understanding of autism in Indigenous communities. Materials and approaches were designed in line with the ‘Aboriginal 8 ways of learning’: (1) learning through narrative, (2) explicit mapping/visualising of processes, (3) applying kinaesthetic (hands-on) skills to thinking and learning, (4) using images and metaphors to understand concepts, (5) linking content to local art and objects, (6) building on existing knowledge, (7) modelling and scaffolding and (8) applying learning for community benefit. These support materials and others can be found on the Positive Partnerships website (https://www.positivepartnerships.com.au/resources/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples).

One of the resources developed by Positive Partnerships (2018) is a booklet designed to help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families identify children who might have autism. The booklet comprises 10 stories from Indigenous families with an autistic child, collected through written, face-to-face and telephone interviews. In these interviews, carers reflected on their experiences identifying unusual traits in their children, obtaining an autism assessment and diagnosis, and seeking appropriate support. Some carers identified a lack of awareness and understanding of autism in their communities, particularly in remote settings. Most reflected on diagnosis as an important step which helped them understand their child’s behaviour and opened new doors in terms of support service eligibility. Reports were mixed in terms of how communities perceived responses to children with autism ranging from judgemental to accepting.

Carers and service providers of children with disabilities, including autism

An early study by McDonald and Zetlin (2004) investigated barriers to service utilisation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disabilities including autism. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups were conducted with service providers from across Queensland. At the user level, service providers identified limited awareness of support services, hesitation to share one’s disability status, and geographical isolation as the key barriers. Services tended to be geared towards Western cultural assumptions and were felt to have an overly strong clinical/medical focus. Providers described services as insular and noted a lack of collaboration between agencies.

DiGiacomo et al. (2013) reported findings from focus groups involving carers and service providers of children with a range of disabilities living in Western Sydney. Interviews elicited information on barriers to support for Indigenous families. Participants were five carers of children with disabilities including autism (number of children with autism not reported) and 17 service providers. Carers and providers both identified limitations in disability awareness as a key barrier to support for Indigenous families. Other barriers included long waiting lists and unaffordable services. Access pathways were described as unnecessarily complicated and some service providers had a reputation for being difficult to contact, especially in remote settings. Carers reported instances of perceived racism, such as feeling increased scrutiny while accessing support, and expressed concern regarding apparent disregard for Indigenous culture. Recommendations for improving service accessibility included using Indigenous workers to assist families to navigate the health system, ensuring that services recognise the importance of the Aboriginal Community Controlled Sector and a reconciliation agenda, and for service providers to be flexible and responsive around the needs of the whole family.

Green et al. (2016) focused on exploring carers’ experiences of navigating disability support systems. Some carers were delayed in seeking support as a result of receiving inaccurate information from other community members regarding their child’s development. Participants reported being faced with long waiting lists and a lack of assistance when seeking funds for support services. Carers felt they were subjected to inflexible rules set by government departments, such as rigid eligibility criteria, which prevented them from accessing appropriate supports. Carers suggested that experiences could be improved by establishing disability support groups hosted by local Aboriginal health services. Carers also advocated for a centralised support service – assisting carers by having all health records in one place, by scheduling appointments with different health services in close succession and by coordinating service provision with external agencies when required.

Using the same dataset, DiGiacomo et al. (2017) examined the costs involved in supporting Indigenous children with disabilities. Carers reported concerns regarding out-of-pocket expenses associated with accessing support, such as food and transport costs. Other financial costs included having to exit the labour force or having to reduce work hours on account of needing to provide care. In terms of non-financial costs, carers described their physical and psychological health as having been affected over the course of caring for their child. For example, the aggressive behaviours of some children were reported as challenges for caregiving and potential sources of injury to carers and siblings. The detrimental effects of financial and non-financial costs were amplified for some families who had to move to other areas to access services, taking them away from the support of their community.

In a final analysis of the dataset, Green et al. (2018) examined carers’ experiences interacting with disability support services. Some carers reported feeling looked down upon and judged when speaking with service providers. Others perceived the way service providers spoke to and behaved towards them as communicating disrespect. Rushed consultations, hastily prescribed medications and limited questioning about children and family contributed to feelings of dissatisfaction. Parents reported a preference for accessing services at Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations as they felt staff at these organisations had a better understanding of culturally appropriate communication, which facilitated better quality care for their child.

A thesis by Green (2018) explored the perspectives of 24 non-Aboriginal community controlled health, education and social service providers on support services for Indigenous children with disabilities in Western Sydney. The ability of families to recognise children’s candidacy for support was viewed as a key factor related to service utilisation. Families’ ability to navigate complex service landscapes and move between services to access multidisciplinary support were also important factors. Interactions between service providers and families were influenced by provider obligations (e.g. mandatory reporting), communication strategies (e.g. limiting use of jargon), awareness of acceptability issues (e.g. time needed to build relationships) and a focus on supporting carers. Providers recognised that families’ past experiences of racism and stigma influenced clinical interactions and that having non-Aboriginal providers guide support delivery could be negatively associated with the destructive child removal practices of the stolen generation.2 The study highlighted that the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are heterogeneous in terms of supporting children with disabilities.

Indigenous populations outside of Australia

Of the 11 publications involving Indigenous populations outside of Australia identified in the search, six were on topics related to autism. These included two systematic reviews. Lindblom (2014) attempted to account for the lower ASD diagnosis rates found in many Indigenous populations around the world. Potential reasons include cultural differences (e.g. perspectives on developmental disability), geographic factors (e.g. physical access to services, service availability) and the influence of historical oppression and discrimination. A second review by Di Pietro and Illes (2014) examined themes in the published research with Indigenous Canadians. The review uncovered a strong focus (98% of studies included in the review) on foetal alcohol syndrome disorder (FASD), with only one study investigating a disability other than FASD and no studies on ASD. Cappiello and Gahagan (2009) provided an overview of the research on Indigenous people with disabilities in communities around the globe, and Chan et al. (2016) reported on Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities in Taiwan. Participants in the Di Pietro and Illes (2016) study were health care workers involved in supporting Indigenous Canadians with disabilities, including autism and cerebral palsy. Bevan-Brown (2013) revisited three previous studies in an investigation focusing on Māori (Aotearoa/New Zealand) people with disabilities, including autism.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to map key themes in the research on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with autism. We conducted a search of the grey and peer-reviewed literature in line with the scoping review framework of Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and Levac et al. (2010) to answer research questions targeting: (1) autism diagnosis and prevalence in Indigenous Australian communities, (2) how autism is perceived by Indigenous Australians and (3) what is known about autism diagnostic and support services for Indigenous Australians. Eleven publications on autism and six publications on disabilities including but not limited to autism met inclusion criteria. This is higher than the number of titles included in the previous reviews by Wilson and Watson (2011; n = 1) and Bennett and Hodgson (2017; n = 2), reflecting both our comprehensive search strategy and an increasing research interest in Indigenous Australians with autism. The following sections summarise findings relating to our three research questions.

Diagnosis and prevalence of ASD in Indigenous Australian communities

The available studies (n = 4) offer a snapshot of some issues surrounding ASD diagnosis and prevalence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. There is emerging evidence that Indigenous children are diagnosed with ASD at rates lower than their non-Indigenous peers (Leonard et al., 2011). However, rather than a difference in prevalence, this pattern has been interpreted as reflecting reduced access to diagnostic services and greater acceptance of individual differences in some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (Bent et al., 2015; Graham, 2012). These same factors may explain some instances of missed or misdiagnosis of ASD identified among Indigenous adults assessed by Roy and Balaratnasingam (2010). To achieve an accurate measure of ASD prevalence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, changes regarding autism awareness and access to support services are required.

Indigenous Australians’ perceptions of autism

Carers and service providers almost uniformly acknowledged gaps in the awareness and understanding of autism in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. This reflects a fundamental difference in the way disability is perceived in some Indigenous Australian and Western cultures. In contrast to the Western perspective which emphasises impairment and the need for remediation, some Indigenous Australians view disability as a characteristic of the individual, something to be supported by the broader community rather than ameliorated. Indeed, labelling and categorising individuals with regard to their abilities or impairments is considered disrespectful in some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (Ravindran et al., 2017). It is perhaps unsurprising then that some respondents in the reviewed studies reported distrust of medical labels, including ‘autism’ (Positive Partnerships, 2018).

Indigenous views on disability cannot be fully understood without an appreciation of how colonialism and racism have affected and continue to affect the health and well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This requires a longer discussion than can be achieved in the current review (interested readers may wish to consult Hollinsworth, 2013 and King et al., 2014).3 A critical point is that historical poverty, marginalisation, and racism have led some Indigenous communities to perceive disability as just one aspect of more general post-colonisation disadvantage. Attempts to improve outcomes for Indigenous Australians with autism need to consider how differences in perception and lived experience influence service delivery.

Diagnostic and support services for autistic Indigenous Australians

Researchers have highlighted the barriers to service utilisation as well as opportunities to improve service delivery by drawing on the perspectives and experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers and service providers (e.g. Foley, 2003). Participants have been recruited from metropolitan, as well as rural and remote settings, and had similarly diverse perspectives and experiences. Although it is difficult to make summative statements regarding services for all Indigenous Australians, there were common themes reported across studies which speak to the perspectives and experiences of many families.

A theme permeating much of the research included in our review was the critical role of community in supporting Indigenous Australian families with autistic children. Like non-Indigenous people (e.g. Tint & Weiss, 2016), some carers reported feeling isolated and concerned about being judged by certain individuals. Others reported feeling well supported and included in community life. We found that many carer and service provider recommendations for improving service delivery and utilisation reported in previous studies focused on enhancing community awareness of autism and adapting service delivery models to accommodate greater community involvement in diagnostic and support processes.

Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians have reported difficulties associated with reduced service availability in rural and remote settings (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2014). Indigenous and non-Indigenous families have also raised concerns about service affordability and unnecessarily complicated government and service provider policies (Green et al., 2016; National People with Disabilities and Carer Council, 2009). Thus, some barriers appear to be widespread. Addressing these concerns will likely improve accessibility for many Australians.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families reported challenges that were additional to those identified for non-Indigenous families. Carers described instances of perceived racism and disrespect in their interactions with some service providers. Some service providers rushed consultations and used inappropriate, jargonistic language, resulting in carers feeling looked down upon and having their views dismissed as irrelevant. These feelings were exacerbated by the perception of predominately non-Indigenous service providers ‘telling’ families how to support children with disabilities. Many carers preferred accessing services through Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations on account of staff’s cultural awareness and culturally appropriate practices (e.g. recognising that children may be cared for by someone other than a parent). Resources for addressing these provider- and organisational-level factors are available on the Autism Spectrum Australia website (https://www.autismspectrum.org.au/content/cultural-and-indigenous-support); however, there remain many opportunities to optimise these support services.

Carers and service providers identified numerous factors influencing service accessibility at the level of government and service provider policy. Carers expressed confusion regarding funding programmes, including the recently introduced National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), and feelings of frustration trying to coordinate services across health and education settings. Combined with the day-to-day struggles of having a child with a disability, this was a drain on carers’ emotional and physical well-being. There were also concerns about mandatory reporting requirements and government involvement, perpetuated by historical experiences of child removal and dispossession. Key recommendations for improving service accessibility are: greater involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in generating government and service provider policy, clear explanation from service providers regarding reporting requirements before engaging Indigenous families and greater support for carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with autism. These and other recommendations are set out in the Australian Government Plan to Improve Outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with Disability (Department of Social Services, 2017).

Limitations and directions for future research

This review utilised rigorous and transparent search methods consistent with the recommendations of the scoping review framework described by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and later enhanced by Levac et al. (2010). A limitation of our review is that we did not complete the optional sixth phase outlined in the scoping review framework: stakeholder consultation.

Much of the research including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with autism has tended to focus on the perspectives and experiences of carers and support service providers. This has generated a rich pool of information on the barriers to service utilisation and recommendations for improving access to support services for Indigenous families. There has been less of a focus on the implementation of these recommendations, and even less focus on the voices of autistic individuals. Future research addressing these gaps should be led by Indigenous Australians and co-designed with local Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations. Such teams will ensure alignment with local Indigenous needs and values.

Conclusion

This scoping review was designed to map key themes in the research on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with autism. Findings from previous studies suggest similar prevalence of ASD across Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, although some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with ASD may not be diagnosed or may be misdiagnosed. Carers and service providers have highlighted barriers to support service delivery and have also suggested numerous opportunities for improving outcomes for Indigenous individuals with autism. These recommendations, particularly those offered by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, must be considered in the provision and assessment of support services for Indigenous Australians with autism.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Rozanna Lilley from Macquarie University for helpful discussion in conducting our review.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Examples of carer and service provider comments.

| Theme Discussion point |

Comments |

|---|---|

| Perspectives on autism | |

| Acceptance of differences as characteristics of the individual | ‘In the Koorie community anyone who is different is cherished. They don’t need a label – they are cherished anyway’ (Higgins & Beecher, 2010, p. 27) ‘This is how he is – we love him for how he is’ (Higgins & Beecher, 2010, p. 36) |

| Distrust of medical labels | ‘It’s about white people doing the labelling and with this are issues of power. This labelling is on top of all the other labels being given to Aboriginal folk’ (Higgins & Beecher, 2010, p. 35) |

| Role of community | ‘The kids call out to him in town – and it makes my other kids know that he is accepted’ (Higgins & Beecher, 2010, p. 27) ‘I felt very abandoned by friends in the beginning – either that or I alienated myself from them’ (Higgins & Beecher, 2010, p. 28) ‘All the while I was dodging judgemental stares and comments from community members on a daily basis’ (Positive Partnerships, 2018, p. 16) ‘Our community includes our son in everything and he learns traditional dance, stories from our elders and soon we will begin teaching him language’ (Positive Partnerships, 2018, p. 8) |

| Barriers to diagnosis and support services | |

| Community awareness and understanding of disability | ‘It was months after she was diagnosed that I found out how serious this was’ (DiGiacomo et al., 2013, p. 5) ‘I talk to family about [child] being different and still need to explain that he is not being naughty if it seems he is not listening’ (Positive Partnerships, 2018, p. 17) ‘And being Aboriginal as well, you kind of think, oh look, they’ll pick up soon enough . . . you’ve got your elder saying to you, No, they’re right. They’re right. Don’t worry about it. They’ll pick up in their own time’ (Green et al., 2018, p. 1926) ‘So if there’s a speech issue they might just say oh, so and so did that at three years old and now they’re talking fine too’ (Green, 2018, p. 92) ‘I was amazed that a couple with a 13 year-old-child with a disability had never received a service from anyone. They didn’t know we existed, they didn’t know other services existed’ (McDonald & Zetlin, 2004, p. 119) |

| Lack of information | ‘Carers have to do the hard yards to get support’ (DiGiacomo et al., 2013, p. 6) ‘We knew something was wrong, it’s just getting the right people to listen’ (Higgins & Beecher, 2010, p. 29) |

| Pathway complexity | ‘It shouldn’t be this hard’ (DiGiacomo et al., 2013, p. 6) ‘I’m a health professional, even for me sometimes when I’m thinking, oh, where do I go about particular things, so there’s so many different services but how do you know which service you need for your child? . . .’ (Green, 2018, p. 95) ‘Because, um, it’s hard for families to have 20 service providers asking them the same questions over and over. Um, and, you know, it frustrates them’ (Green, 2018, p. 97) |

| Insufficient funding | ‘They’re under-resourced as well and that is all we can do’ (McDonald & Zetlin, 2004, p. 120) |

| Labour force exit | ‘Well I was working. But I have stopped . . . Yeah, the amount of time that I have off. It was my decision, it’s the school, a handful of weeks like every day’ (DiGiacomo et al., 2017, p. 5) |

| Parental well-being | ‘And then, yeah, when she got diagnosed with it – it’s hard . . . I stress a lot, I cry a lot’ (DiGiacomo et al., 2017, p. 6) ‘It’s become very stressful, yeah. At the doctor’s today, before I was going to the hospital, I am on edge and I am, like, fighting doesn’t get it done, but I can’t just sit back and agree anymore and say, yeah don’t worry, you know it’s okay. We will see’ (DiGiacomo et al., 2017, p. 6) |

| Gearing towards Western culture | ‘I know all of the neighbourhood centres in this whole region, and I have lived here for 12 years, so I know every single CDO [Community Development Officer] and every single community centre in the region and I know that they don’t provide services to people from ethnic backgrounds’. (McDonald & Zetlin, 2004, p. 119) |

| Overly clinical/medical approach | ‘People just couldn’t be themselves; they just wanted to talk about stuff and a lot of the stuff they talked about, a lot of it’s around spiritual stuff. You know, it’s not just like spiritual as in religion. You know, like spiritual as in cultural stuff. And the people they talked to just didn’t understand that. It’s still very much clinical, very clinical’ (McDonald & Zetlin, 2004, p. 120) |

| Community priorities | ‘If [a program’s] not the priority at that time for that community or those families it’s not going to happen . . . we were working on school readiness but we couldn’t get to work with the families on school readiness straight away because their biggest issue was they were actually going to be evicted and they had no money for food . . .’ (Green, 2018, p. 110) |

| Waiting lists | ‘I understand there is kids that are a lot worse than [child]. I do understand that. It’s just, with this waiting list, he’d probably be able to speak by then, he wouldn’t even need it . . . And then I got upset, and I said to my mum, it’s like no-one’s out there that wants to help’ (Green et al., 2016, p. 5) ‘Well, I mean, the current, ah – how to say it – the problem with the public system is long waiting lists. So currently speech pathology at the [Community Health Centre] has a two-year waiting list. So, ah, there’s clearly a problem for those who believe in the importance of early intervention’ (Green, 2018, p. 93) |

| Service provider obligations | ‘I mean generally I’d say that a lot of the difficulties we’ve had with Aboriginal children too is around perhaps child protection for a lot of families because that child protection may get involved and then there’s a whole new aspect of the service provision . . . we try and make sure families realise from day one that we get involved that we’re mandatory reporters. That’s part of the general script that we talk to families about, so it’s no surprise and we do tell families if we’re going to do it’ (Green, 2018, p. 116) |

| Influence of racism | ‘A European child with autism would be accepted more than what a little Aboriginal child would be’ (Higgins & Beecher, 2010, p. 33) ‘Because I’m Aboriginal, like, it’s harder to get things done because half the time . . . doctors, hospitals, like, they look down on me, like because of my colour, yeah, the colour of my skin and, like, they talk to me like I don’t know nothing . . . they just talk to me in a rude tone and, like, they, like, give me attitude’ (Green et al., 2018, p. 1926) |

| Rushed consultations | ‘I had [child] to another paediatrician before we started here [ACCHO] with him, and I wasn’t impressed . . . he just looked at her and he said, I think I will medicate her. He didn’t explain anything to me . . . I just went away and I thought well that’s not good enough, you haven’t really asked me anything’ (Green et al., 2018, p. 1927) |

| Service providers’ disregard for Indigenous culture | ‘There is no allowances whatsoever, they just feel that because you’re Australian, we’ve got to be the same as any other Aussie person. Well, it’s not. We’re Indigenous. We’ve got our beliefs and everything, and people don’t understand that’ (Green et al., 2018, p. 1927) |

| Perceived disrespect | ‘They don’t respect me, in a way, like with the kids. Well, mostly with her [child with disability]. I have got one doctor that is really rude and everything . . . The way they talk, and just the actions . . . Well, when they go to check her over . . . just mostly they are thinking that, in my eyes, that I am a bad parent’ (Green et al., 2018, p. 1926) |

| Service provider interaction style | ‘I’m a therapist, I’m probably a lot better at it now than I used to be, but, you know, talking in plain English instead of jargon, therapists quite like the jargon, but I think also teachers can do the same and not speaking in a language that’s understandable for people’ (Green, 2018, p. 112) |

| Disclosure of disability status | ‘This is the thing which keeps a lot of these older folk and disabled folk isolated. They really didn’t want to go out because it was too hard to go and do the shopping maybe. They were embarrassed over going into a store with a disability, that’s how it is’ (McDonald & Zetlin, 2004, p. 119) |

| Financial hardship | ‘The first two we stayed at work and tried to cope, and then with the bad behaviour and that it just got a bit too much. And yeah, so I only work two days a week now, and my husband doesn’t work, he had got a carer’s pension for the children’ (DiGiacomo et al., 2017, p. 5) ‘He was seeing another paediatrician and I just could not afford to send him when he needed to go because it was like a hundred and something dollars. I know that you get money back but its $100 that you have to fork out to pay for it up front’ (DiGiacomo et al., 2017, p. 5) ‘So yep, it doesn’t help a lot of the families that have the younger kids and that’s why – and I’ve always said that that’s why they don’t get seen to the right people because of the financial cost of that’ (Green et al., 2016, p. 7) ‘Costs me about a hundred and two dollars to fill up my car. And that means if I go to (hospital) more than four times a week I have to fill up again’. (Di Giacomo et al., 2017, p. 5) |

| Non-financial costs | ‘It’s tiring and especially when I work nights . . . It’s tiring to, um, drag the kids around and – yeah . . . I mean it is–it’s very tiring, emotionally and physically’ (DiGiacomo et al., 2017, p. 6) ‘So they wanted me, pick her up and then bring her here, drop her off. I said, no, no, no, no, it’s too complicated for me. Pick up the boys, you go to the school, oh no, we can’t do that’ (Green et al., 2016, p. 6) |

| Limited uptake of services | ‘I actually don’t understand why is it that we’re not seeing more Aboriginal families . . . we just seem to see so very few and I don’t quite understand why’ (Green, 2018, p. 99) |

| Geographical isolation | ‘I had a client [names small town some distance away] who was receiving Meals on Wheels, and they actually cut her Meals on Wheels because it was too much on their mileage budget. I mean, okay if it was too much on their mileage budget, alright! We can understand that because of the distance. But nobody saw another alternative for this lady, you know’ (McDonald & Zetlin, 2004, p. 120) |

| Inflexible government policies | ‘. . . the Carer’s Allowance loan was supposed to be coming up, and I wanted to pay the rest of it off to get another loan for [children’s hospital], because I have to pay for an overnight stay with her, and for one of these tests I have to pay for it. And they won’t be able to help me until the 27th of this month. And my appointment is on the 25th’ (Green et al., 2016, p. 7) |

| Strategies to improve access to diagnostic and support services | |

| Community education and training | ‘The community hadn’t had autism right directly in their face until (child) and when I educated them some said ‘oh that’s what was wrong with so and so 20 years ago – he didn’t talk’ (Higgins & Beecher, 2010, p. 26) |

| Building relationships with time and regular communication | ‘Families need to hear the information lots of times to reinforce what’s being said’ (Higgins & Beecher, 2010, p. 34) |

| Centralised team-based Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations | ‘This is why I keep coming back here, because they were fantastic. Ah, um, not only do they help with [child], they help with housing, they help with me with my ex-husband, you know what I mean. Um, they help me with getting some counselling’ (Green et al., 2016, p. 7) |

| Support groups | ‘I think that that would be something that would be helpful for us to just be able to have some sort of connection to other families, in particular Aboriginal families . . . and whether the [Aboriginal health service] can, sort of, do that’ (Green et al., 2016, p. 5) |

| Supporting carers | ‘The most important thing that we can do for the Aboriginal community, um, for the whole community, um, of anyone who has a child with a learning need is to empower that parent – and to make that parent resilient’ (Green, 2018, p. 106) |

| Benefits of autism diagnosis | ‘An autism diagnosis at the age of 4 meant we finally had an answer and we started a journey that has changed our lives for the better’ (p. 6, Positive Partnerships, 2018) ‘The diagnosis opened up new opportunities for us to get real support, including speech pathology and special education’ (Positive Partnerships, 2018, p. 4) |

| Community engagement | ‘The strongest thing about Aboriginals is our support system. I don’t think we’d be able to cope without it’ (Higgins & Beecher, 2010, p. 31) ‘I want my community to connect with him because he doesn’t know how to connect with them’ (Higgins & Beecher, 2010, p. 31) |

Wherever possible, quotes relate to autism. Some quotes are drawn from studies which included individuals with a range of disabilities (e.g. studies by DiGiacomo et al. and Green et al. recruited from developmental clinics or focused predominately on people with developmental disabilities).

The authors were unable to obtain a copy of the Nogrady (2008) article; however, publications included in the review were able to be accessed via the Commonwealth of Australia Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs who edited the literature search.

The term ‘Stolen Generation’ refers to the estimated 1 in 10 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were forcibly removed from their families and communities between the 1910s and the 1970s as a result of assimilation policies adopted by Australian governments. Recommendations for redressing the impacts of the Stolen Generation, including a national apology, reparations and improved access to support services, are discussed in the Bringing them Home Report (Commonwealth of Australia, 1997).

Readers are also referred to Culture is inclusion: A narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability (Avery, 2018), a book brought to the authors’ attention during peer review which provides an in-depth discussion of issues affecting Indigenous Australians with disabilities. This includes comments on education from a parent of a child with autism.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This work was partly supported by a mid-career SOAR research fellowship awarded to Joanne Arciuli by The University of Sydney. SOAR funding also supported the open access fee for this article.

ORCID iD: Joanne Arciuli  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7467-9939

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7467-9939

References

*is used to identify the articles which were included in our review.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong E. S., Jokel A. (2012). Language outcomes for preverbal toddlers with autism. Studies in Literature and Language, 4(3), 1–7. 10.3968/j.sll.1923156320120403.3528 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2014). General social survey (No. 4159.0). https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4159.0

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2015). Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings (No. 4430.0). https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4430.0

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council. (2017). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/oatsih_heath-performanceframework

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2015). The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-health-welfare/indigenous-health-welfare-2015/

- Autism Spectrum Australia. (2013). We belong: The experiences, aspirations and needs of adults with Asperger’s disorder and high functioning autism. https://www.autismspectrum.org.au/uploads/documents/Research/Autism_Spectrum_WE_BELONG_Research_Report-FINAL_LR_R.pdf

- Avery S. (2018). Culture is inclusion: A narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability. First Peoples Disability Network. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey B., Arciuli J. (2019, June). Autism spectrum disorders in Indigenous Australia: A comprehensive scoping review [Paper presentation]. Interactive poster at Lowitja Institute International Indigenous Health and Wellbeing Conference, Darwin, NT, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Baird G., Simonoff E., Pickles A., Chandler S., Loucas T., Meldrum D., Charman T. (2006). Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: The Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). The Lancet, 368, 210–215. 10.1017/S0033291710000991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bennett M., Hodgson V. (2017). The missing voices of Indigenous Australians with autism in research. Autism, 21(1), 122–123. 10.1177/1362361316643696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bent C. A., Dissanayake C., Barbaro J. (2015). Mapping the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in children aged under 7 years in Australia, 2010–2012. Medical Journal of Australia, 202(6), 317–320. 10.5694/mja14.00328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan-Brown J. (2013). Including people with disabilities: An indigenous perspective. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17, 571–583. 10.1080/13603116.2012.694483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond S., Whop L., Drummond A. (2019). The blackfulla test: 11 reasons that indigenous health research grant/publications should be rejected. https://indigenousx.com.au/the-blackfulla-test-11-reasons-that-indigenous-health-research-grant-publication-should-be-rejected/

- Cappiello M. M., Gahagan S. (2009). Early child development and developmental delay in indigenous communities. Pediatric Clinics, 56, 1501–1517. 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Casuscelli L., Reimer J. (2017, 7–9 September). Using ‘strong and deadly’ partnerships to raise awareness and increase understanding of autism in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across Australia [Paper presentation]. Fifth Asia Pacific Autism Conference, Sydney, NSW, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Chan H. L., Liu W. S., Hsieh Y. H., Lin C. F., Ling T. S., Huang Y. S. (2016). Screening for attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and developmental delay in Taiwanese aboriginal preschool children. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 2521–2526. 10.2147/NDT.S113880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman T., Pickles A., Simonoff E., Chandler S., Loucas T., Baird G. (2011). IQ in children with autism spectrum disorders: Data from the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Psychological Medicine, 41, 619–627. 10.1017/S0033291710000991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. (1997). Bringing them home: Report of the national inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children for their families. https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/bringing-them-home-report-1997

- Department of Social Services. (2017). Australian government plan to improve outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability. https://www.dss.gov.au/disability-and-carers/supporting-people-with-disability/resources-supporting-people-with-disability/australian-government-plan-to-improve-outcomes-for-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people-with-disability

- *DiGiacomo M., Delaney P., Abbott P., Davidson P. M., Delaney J., Vincent F. (2013). ‘Doing the hard yards’: Carer and provider focus group perspectives of accessing Aboriginal childhood disability services. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 326 10.1186/1472-6963-13-326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *DiGiacomo M., Green A., Delaney P., Delaney J., Patradoon-Ho P., Davidson P. M., Abbott P. (2017). Experiences and needs of carers of Aboriginal children with a disability: A qualitative study. BMC Family Practice, 18, 96 10.1186/s12875-017-0668-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro N. C., Illes J. (2014). Disparities in Canadian indigenous health research on neurodevelopmental disorders. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 35, 74–81. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro N. C., Illes J. (2016). Closing gaps: Strength-based approaches to research with Aboriginal children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Neuroethics, 9, 243–252. 10.1007/s12152-016-9281-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foley D. (2003). Indigenous epistemology and Indigenous standpoint theory. Social Alternatives, 22(1), 44–52. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=200305132;res=IELAPA [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy J., Donelly M., Colmar S., Parmenter T. (2013). Conceptual framework for policy and research development with Indigenous people with disabilities. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2, 42–58. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=751842945817584;res=IELIND [Google Scholar]

- *Graham L. J. (2012). Disproportionate over-representation of Indigenous students in New South Wales government special schools. Cambridge Journal of Education, 42, 163–176. 10.1080/0305764X.2012.676625 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K. M., Keating C. M., Taffe J. R., Brereton A. V., Einfeld S. L., Reardon T. C., Tonge B. J. (2014). Adult outcomes in autism: Community inclusion and living skills. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3006–3015. 10.1007/s10803-014-2159-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Green A. (2018). Families with an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child with disability: System, service and provider perspectives [Doctoral dissertation]. https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/125644

- *Green A., Abbott P., Davidson P. M., Delaney P., Delaney J., Patradoon-Ho P., DiGiacomo M. (2018). Interacting with providers: An intersectional exploration of the experiences of carers of Aboriginal children with a disability. Qualitative Health Research, 28, 1923–1932. 10.1177/1049732318793416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Green A., Abbott P., Delaney P., Patradoon-Ho P., Delaney J., Davidson P. M., DiGiacomo M. (2016). Navigating the journey of Aboriginal childhood disability: A qualitative study of carers’ interface with services. BMC Health Services Research, 16, 680 10.1186/s12913-016-1926-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Green A., DiGiacomo M., Luckett T., Abbott P., Davidson P. M., Delaney J., Delaney P. (2014). Cross-sector collaborations in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability: A systematic integrative review and theory-based synthesis. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13, 126 10.1186/s12939-014-0126-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happé F., Booth R., Charlton R., Hughes C. (2006). Executive function deficits in autism spectrum disorders and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Examining profiles across domains and ages. Brain and Cognition, 61(1), 25–39. 10.1016/j.bandc.2006.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Higgins J., Beecher S. (2010, 27–29 July). SNAICC/PRC early days project [Paper presentation]. 2010 Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care Conference, Alice Springs, NT, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Hollinsworth D. (2013). Decolonizing indigenous disability in Australia. Disability & Society, 28(5), 601–615. 10.1080/09687599.2012.717879 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P., Moss P. (2012). Adults with autism spectrum disorders. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(5), 275–283. 10.1177/070674371205700502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J. A., Brough M., Knox M. (2014). Negotiating disability and colonisation: The lived experience of Indigenous Australians with a disability. Disability & Society, 29(5), 738–750. 10.1080/09687599.2013.864257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kjelgaard M. M., Tager-Flusberg H. (2001). An investigation of language impairment in autism: Implications for genetic subgroups. Language and Cognitive Processes, 16(2–3), 287–308. 10.1080/01690960042000058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel L. K., Koegel R. L., Ashbaugh K., Bradshaw J. (2014). The importance of early identification and intervention for children with or at risk for autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(1), 50–56. 10.3109/17549507.2013.861511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Leonard H., Glasson E., Nassar N., Whitehouse A., Bebbington A., Bourke J., . . . Stanley F. (2011). Autism and intellectual disability are differentially related to sociodemographic background at birth. PLOS ONE, 6, Article e17875. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lilley R., Pellicano L., Sedgwick M., Carlson B., Kennedy T. (2018, 6–7 December). Different kids, different stories: Indigenous Australian family experiences of autism [Paper presentation]. Fourth Biennial Conference of the Australasian Society for Autism Research, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom A. (2014). Under-detection of autism among First Nations children in British Columbia, Canada. Disability & Society, 29, 1248–1259. 10.1080/09687599.2014.923750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *McDonald C., Zetlin D. (2004). ‘The more things change. . .’: Barriers to community services utilisation in Queensland. Australian Social Work, 57, 115–126. 10.1111/j.1447-0748.2004.00126.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National People with Disabilities and Carer Council. (2009). Shut out: The experience of people with disabilities and their families in Australia. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2012/nds_report.pdf

- Nogrady M. (2008). Autism spectrum disorders in Indigenous children. Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien G., White P. (2014). Is autism rare in very remote Aboriginal communities? Specialist Disability Services Assessment and Outreach Team. [Google Scholar]

- Ou L., Chen J., Hillman K., Eastwood J. (2010). The comparison of health status and health services utilisation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous infants in Australia. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 34, 50–56. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00473.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer R. F., Walker T., Mandell D., Bayles B., Miller C. S. (2010). Explaining low rates of autism among Hispanic schoolchildren in Texas. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 270–272. 10.2105/ajph.2008.150565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Positive Partnerships. (2018). Autism. Our kids, our stories: Voices of Aboriginal parents across Australia. https://www.positivepartnerships.com.au/resources/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/autism-our-kids-our-stories-voices-of-aboriginal-parents-across-australia

- Ravindran S., Brentnall J., Gilroy J. (2017). Conceptualising disability: A critical comparison between Indigenous people in Australia and New South Wales disability service agencies. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 52, 367–387. 10.1002/ajs4.25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S. J., Estes A., Vismara L., Munson J., Zierhut C., Greenson J., . . . Whelan F. (2019). Enhancing low-intensity coaching in parent implemented Early Start Denver Model intervention for early autism: A randomized comparison treatment trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 632–646. 10.1007/s10803-018-3740-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Roy M., Balaratnasingam S. (2010). Missed diagnosis of autism in an Australian indigenous psychiatric population. Australasian Psychiatry, 18(6), 534–537. 10.3109/10398562.2010.498048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision. (2014). Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: Key indicators 2014. https://www.pc.gov.au/research/ongoing/overcoming-indigenous-disadvantage/2014

- Tager-Flusberg H., Paul R., Lord C., Volkmar F., Paul R., Klin A. (2005). Language and communication in autism. In Volkmar F. R., Paul R., Klin A., Cohen D. J. (Eds.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (pp. 335–364). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Tint A., Weiss J. A. (2016). Family wellbeing of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Autism, 20(3), 262–275. 10.1177/1362361315580442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanti G., Barbaro J., Hudry K., Dissanayake C., Prior M. (2013). Intellectual development in autism spectrum disorders: New insights from longitudinal studies. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 354 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wilson K., Watson L. (2011). Autism spectrum disorder in Australian Indigenous families: Issues of diagnosis, support and funding. Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, 35(5), 17–18. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=670577298035246;res=IELHEA [Google Scholar]