Coxiella burnetii is the causative agent of human Q fever, eliciting symptoms that range from acute fever and fatigue to chronic fatal endocarditis. C. burnetii is a Gram-negative intracellular bacterium that replicates within an acidic lysosome-like parasitophorous vacuole (PV) in human macrophages. During intracellular growth, C. burnetii delivers bacterial proteins directly into the host cytoplasm using a Dot/Icm type IV secretion system (T4SS).

KEYWORDS: Coxiella burnetii, apoptosis, eIF2α, intracellular, macrophage, unfolded protein response

ABSTRACT

Coxiella burnetii is the causative agent of human Q fever, eliciting symptoms that range from acute fever and fatigue to chronic fatal endocarditis. C. burnetii is a Gram-negative intracellular bacterium that replicates within an acidic lysosome-like parasitophorous vacuole (PV) in human macrophages. During intracellular growth, C. burnetii delivers bacterial proteins directly into the host cytoplasm using a Dot/Icm type IV secretion system (T4SS). Multiple T4SS effectors localize to and/or disrupt the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and secretory transport, but their role in infection is unknown. During microbial infection, unfolded nascent proteins may exceed the folding capacity of the ER, activating the unfolded protein response (UPR) and restoring the ER to its normal physiological state. A subset of intracellular pathogens manipulates the UPR to promote survival and replication in host cells. In this study, we investigated the impact of C. burnetii infection on activation of the three arms of the UPR. An inhibitor of the UPR antagonized PV expansion in macrophages, indicating this process is needed for bacterial replication niche formation. Protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) signaling was activated during infection, leading to increased levels of phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor α, which was required for C. burnetii growth. Increased production and nuclear translocation of the transcription factor ATF4 also occurred, which normally drives expression of the proapoptotic C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP). CHOP protein production increased during infection; however, C. burnetii actively prevented CHOP nuclear translocation and downstream apoptosis in a T4SS-dependent manner. The results collectively demonstrate interplay between C. burnetii and specific components of the eIF2α signaling cascade to parasitize human macrophages.

INTRODUCTION

Coxiella burnetii is the causative agent of zoonotic Q fever, with livestock serving as common mammalian reservoirs for the pathogen yet remaining largely asymptomatic. Q fever presentation in humans ranges from acute (flu-like symptoms, fever, and fatigue) to chronic (potentially fatal endocarditis) disease (1, 2). Acute symptoms can be alleviated by doxycycline treatment, while chronic disease is difficult to combat with currently available antibiotics and requires a prolonged treatment course (up to 1.5 years). To initiate disease following inhalation, C. burnetii is phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages, wherein the pathogen undergoes a biphasic life cycle. During this transition, C. burnetii converts from a nonreplicative, metabolically inactive small cell variant (SCV) morphological form to a large cell variant (LCV) form that replicates to high numbers over the course of 1 to 2 weeks (3). SCV to LCV transition and replication occurs within a unique, acidic, lysosome-like parasitophorous vacuole (PV). The PV forms through heterotypic fusion with autophagosomes, endosomes, and lysosomes and is required for bacterial replication and disease progression. During infection, C. burnetii uses a Dot/Icm type IV secretion system (T4SS) to deliver bacterial effector proteins into the host cytoplasm to control numerous events (19), including vesicular fusion and apoptosis prevention (4, 5). The importance of the T4SS was highlighted in studies showing that loss of IcmD or IcmL, inner membrane components of the T4SS, prevents cytosolic delivery of effectors, PV formation, bacterial replication, and inhibition of apoptosis (6, 7). The nature of effectors, and the critical processes they control, is a major focus in the C. burnetii field.

A subset of T4SS effectors localizes to and/or disrupts the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and secretory transport (6, 8), suggesting C. burnetii actively subverts ER-mediated processes. ER-resident calnexin surrounds the PV, indicating close association with this important host organelle that regulates vesicular trafficking and protein delivery to target sites (8). During microbial infection, unfolded proteins can exceed ER folding capacity, activating the unfolded protein response (UPR) to revert the ER to its physiological state (9). Levels of proteins entering the ER are decreased by downregulating polypeptide synthesis and translocation. ER chaperones are then activated to increase cellular capacity for protein folding. Unfolded proteins remaining in the ER are subject to ER-associated degradation (ERAD) by the proteasome. Apoptotic cell death ultimately occurs if homeostasis is not achieved.

The UPR consist of three distinct arms that activate specific downstream responses: (i) inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α) that activates autophagy, (ii) protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) activation that promotes apoptosis, and (iii) activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) activation and nuclear translocation that regulate lipid synthesis (10). The ER chaperone 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78/BiP) signals ER stress sensors and activates the UPR. IRE1α activation leads to splicing of X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1) mRNA and downstream translation and nuclear translocation of the transcription factor XBP1s (spliced form). PERK stimulation results in apoptosis through activation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), translocation of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) to the nucleus, and production of proapoptotic C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP). ATF6 translocates to the Golgi apparatus, undergoes site-specific cleavage, and then translocates into the nucleus.

Certain intracellular pathogens manipulate the UPR and/or ERAD to promote intracellular replication (11–14). Intracellular Orientia tsutsugamushi induces the UPR and impedes ERAD to stockpile amino acids until bacteria enter log phase (12). Legionella pneumophila infection triggers the UPR in alveolar macrophages, and the pathogen uses T4SS effectors to suppress the UPR by blocking BiP and CHOP production (13). L. pneumophila also secretes effectors that inhibit XBP1 activation (13). In contrast, Brucella spp. require a functional ER for infection and trigger the UPR to enable intracellular replication, using T4SS-secreted VceC to activate IRE1α (14). Together, these related pathogen activities highlight the significance of UPR modulation in infectious disease caused by intracellular bacteria.

Here, we used the established THP-1 human macrophage-like cell model (15, 16) to assess the requirement of the UPR for efficient C. burnetii replication. Results show phosphorylated levels of eIF2α increased during C. burnetii infection in a T4SS-dependent manner, leading to increased production and nuclear translocation of ATF4. Importantly, phosphorylation of eIF2α was required for optimal PV expansion and bacterial replication. A downstream consequence of ATF4 activity is expression of proapoptotic CHOP (9). Interestingly, while CHOP production increased during C. burnetii infection, the pathogen actively inhibited ER stress-induced apoptosis in a T4SS-dependent manner by inhibiting nuclear translocation of CHOP.

RESULTS

UPR inhibition antagonizes C. burnetii PV expansion.

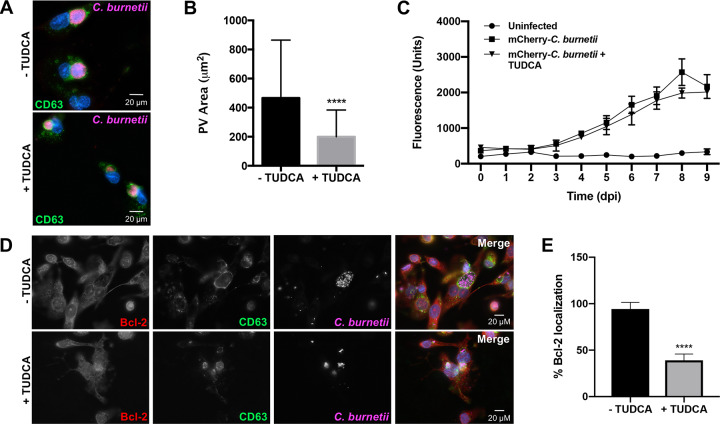

The PV decorates with ER-resident calnexin and associates with the host sterol-binding protein ORP1L (17), and numerous T4SS effectors localize to and disrupt the ER and secretory transport (6, 8). Therefore, we predicted C. burnetii modulates ER processes, such as the UPR, to regulate ER stress and promote PV formation and maintenance. To test this hypothesis, we first assessed whether ER stress is essential for PV expansion in THP-1 human macrophage-like cells. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), an ER stress-reducing chaperone that prevents unfolded protein aggregation by eliciting BiP production and blocks calcium-mediated apoptosis by decreasing intracellular calcium (18), was used as a general UPR inhibitor. Effects of TUDCA on PV expansion were assessed using immunofluorescence microscopy at 72 h postinfection (hpi) (Fig. 1A), and results show that TUDCA treatment significantly decreased PV expansion (∼500 μm2 for wild type compared to ∼200 μm2 for TUDCA-treated cells) (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that preventing the UPR during C. burnetii infection of macrophages inhibits PV expansion.

FIG 1.

UPR inhibition antagonizes C. burnetii PV expansion. (A) THP-1 cells were infected with C. burnetii for 72 h with or without TUDCA (500 μg/ml). Cells were processed for microscopy using antibodies against C. burnetii (violet) and CD63 (green), and DNA was stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; blue). TUDCA-treated cells contain PVs with decreased area compared to that of untreated cells. (B) Average areas of PVs in experiment shown in panel A. More than 50 vacuoles were measured per condition. ****, P < 0.0001, and error bars indicate the standard deviations from the means. A significant decrease in PV expansion occurred in TUDCA-treated cells. (C) THP-1 cells infected with mCherry-expressing C. burnetii were treated with TUDCA (500 μg/ml) every 24 h for 9 days and compared to untreated infected cells. Uninfected cells served as a measure of background fluorescence. Error bars indicate standard deviations from the means. No significant difference in fluorescence was observed from 0 to 9 days postinfection (dpi) between TUDCA-treated and untreated infected cells, indicating UPR inhibition does not prevent C. burnetii growth. (D) C. burnetii-infected THP-1 cells at 72 hpi with or without TUDCA treatment were processed for microscopy using antibodies against C. burnetii (violet), CD63 (green), and Bcl-2 (red), and DAPI stained DNA (blue). (E) Quantification of cells in experiment shown in panel D was performed in duplicates of >100 cells per condition. ****, P < 0.0001, and error bars indicate the standard deviations from the means. A significant decrease in Bcl-2 recruitment to the PV was observed in TUDCA-treated infected cells, indicating Bcl-2 is not recruited to the PV when the UPR is suppressed.

To determine if decreased PV size corresponded to less efficient bacterial replication, we monitored C. burnetii growth in THP-1 cells treated with TUDCA. Fluorescence-based growth curves were used to monitor increases in mCherry-expressing C. burnetii fluorescence (corresponding to viable bacteria) in the presence or absence of TUDCA from 1 to 9 days postinfection (dpi) (Fig. 1C). No significant increase in fluorescence intensity was observed at any time postinfection when treated cells were compared to nontreated macrophages, suggesting UPR inhibition does not significantly impact bacterial replication. Fluorescence growth curve analysis was complemented by quantification of bacterial genomes in infected and treated samples, confirming bacterial replication was not significantly altered by TUDCA (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Although C. burnetii replication was not significantly altered by TUDCA, decreased PV expansion suggests inefficient fusion with intracellular components that could impact cell signaling events. TUDCA antagonizes nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) activation, decreasing levels of antiapoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) (19). C. burnetii promotes NF-κB activation and recruits Bcl-2 to the PV membrane (20). Bcl-2 alters PV development, and C. burnetii modulates interplay between this protein and associated proteins, including beclin-1. Therefore, it is plausible that TUDCA perturbs Bcl-2 recruitment to the PV membrane, interfering with proper vacuole formation. To assess this possibility, infected THP-1 cells treated with TUDCA were processed for microscopy to detect Bcl-2 localization to the PV as a readout of normal PV development. Compared to that in untreated infected cells, Bcl-2 recruitment to the PV in TUDCA-treated cells significantly decreased, as evidenced by diminished colocalization with vacuolar CD63 at the PV membrane (Fig. 1D and E). These results suggest the UPR aids proper PV formation events.

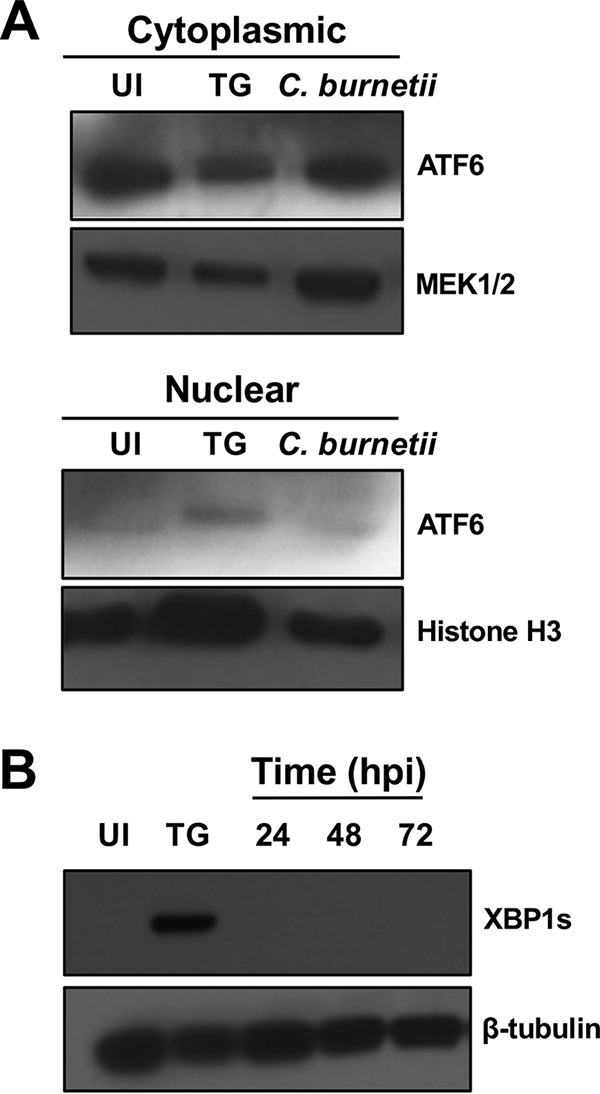

ATF6 and IRE1α are not activated in response to C. burnetii.

Inhibiting the UPR decreased PV size, suggesting C. burnetii usurps this host response to control vacuolar events. However, specific branches of the UPR activated in response to C. burnetii are unknown. We first investigated activation of ATF6 and IRE1α. During ER stress, ATF6 translocates to the Golgi apparatus, where two site-specific proteases cleave the protein, and fragmented ATF6 translocates to the nucleus. Fragmented ATF6 functions as a transcription factor to regulate chaperone and lipid synthesis-related gene expression (9). C. burnetii modulates host cell lipid signaling to generate the PV membrane (21, 22), suggesting ATF6 activity could benefit the pathogen. We first assessed production and nuclear translocation of ATF6 by immunoblot analysis. Thapsigargin (TG), an ER stress-inducing molecule that increases cytosolic calcium and arrests the sarcoplasmic reticulum/ER calcium ATPase (23, 24), was used to activate ATF6 in uninfected cells as a positive control. We then isolated cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins and performed immunoblot analysis to detect ATF6 in respective cell fractions. As shown in Fig. 2A, ATF6 did not translocate to the nuclei of C. burnetii-infected cells, suggesting this pathway is not activated in response to the pathogen.

FIG 2.

ATF6 and IRE1α are not activated by C. burnetii. (A) Immunoblot analysis of the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of infected cells (72 hpi) was performed using an antibody against ATF6. MEK1/2 and histone H3 served as the cytoplasmic and nuclear loading controls, respectively. TG-treated cells served as the positive control, and uninfected cells served as a negative control. UI, uninfected cells. C. burnetii infection does not trigger increased ATF6 nuclear translocation compared to that in uninfected cells. (B) Immunoblot analysis comparing XBP1s in C. burnetii-infected whole-cell lysates (24 to 72 hpi) to that in uninfected and TG-treated cells. β-Tubulin served as the loading control. XBP1s is not produced during infection.

We next investigated the IRE1α pathway that initiates with dimerization and phosphorylation of IRE1α, resulting in downstream splicing of XBP1 to XBP1s, a transcription factor that translocates to the nucleus and regulates expression of genes involved in protein chaperoning and folding (9). IRE1α is triggered by other pathogenic bacteria in pro- and antibacterial manners. For example, intracellular infection by Staphylococcus aureus triggers IRE1α activation and consequent macrophage bactericidal activity through enhanced production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), while Brucella abortus requires activation of this pathway for fusion with ER-derived vacuoles and bacterial replication (25, 26), indicating diverse IRE1α activity during intracellular pathogen infection. To assess IRE1α activation during C. burnetii infection, production of XBP1s, the spliced isoform of XBP1, was assessed by immunoblot analysis. As shown in Fig. 2B, XBP1s was not detectable during infection, suggesting the IRE1α pathway is not activated in response to C. burnetii.

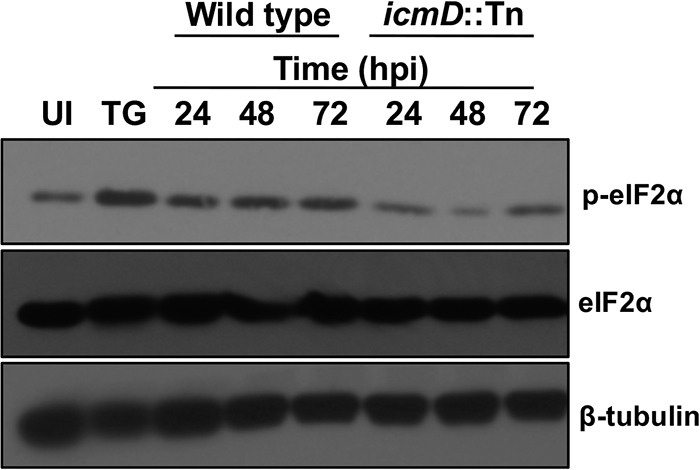

Phosphorylated eIF2α levels increase during C. burnetii infection in a T4SS-dependent manner.

The third arm of the UPR involves PERK, which dimerizes and autophosphorylates during times of ER stress (9). PERK then phosphorylates and activates eIF2α. eIF2α activity elicits production and nuclear translocation of the transcription factor ATF4, and nuclear ATF4 regulates production of numerous proteins, including proapoptotic CHOP. Studies by George et al. show PERK kinase activity is necessary for proper inclusion formation and shedding of the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia muridarum (27). To assess PERK activation during C. burnetii infection, we conducted an immunoblot analysis of eIF2α. Figure 3 shows that phosphorylated eIF2α levels increased substantially during wild-type C. burnetii infection of THP-1 cells.

FIG 3.

Phosphorylated eIF2α levels increase during C. burnetii infection in a T4SS-dependent manner. Immunoblot analysis of wild-type and IcmD mutant C. burnetii-infected cells (24 to 72 hpi) was performed using antibody against eIF2α and phosphorylated eIF2α. TG-treated cells served as the positive control, and β-tubulin served as the loading control. C. burnetii promotes increased levels of phosphorylated eIF2α compared to that in uninfected cells, whereas IcmD mutant-infected cells do not contain increased levels of phosphorylated eIF2α.

To determine if increased eIF2α phosphorylation is actively triggered by C. burnetii, we assessed infection by IcmD-deficient bacteria (icmD::Tn) in which the T4SS is rendered nonfunctional by a Himar1 transposon insertion in icmD (5). Levels of phosphorylated eIF2α were substantially lower in IcmD mutant-infected cells than those with wild-type infection and did not increase relative to phosphorylated eIF2α in uninfected cells (Fig. 3). The requirement of a functional T4SS for increased eIF2α phosphorylation during C. burnetii infection indicates bacterial effectors actively regulate this activity.

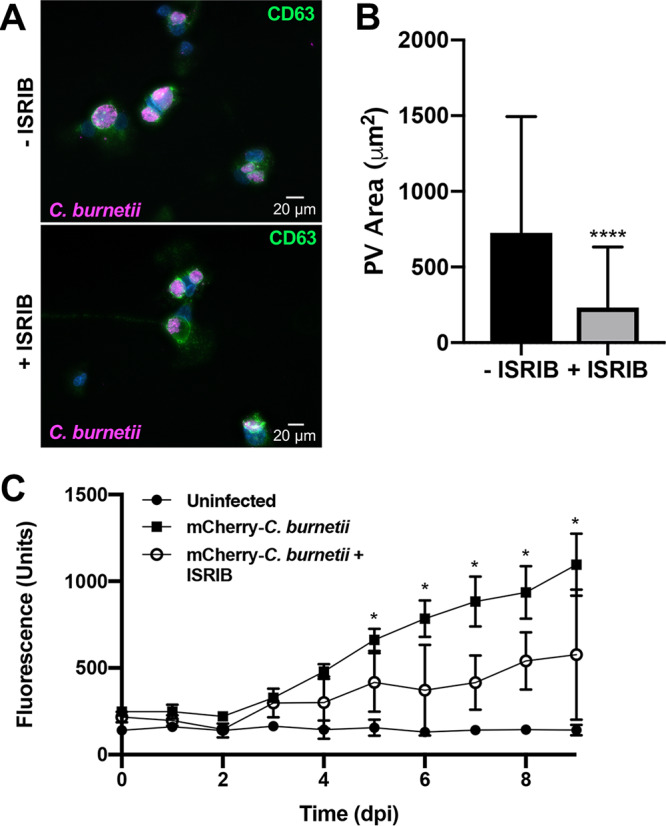

eIF2α activity is required for PV expansion and intracellular C. burnetii replication.

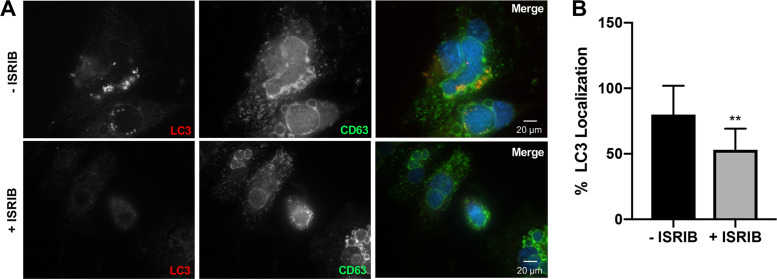

To determine if eIF2α activity is essential for C. burnetii PV expansion and bacterial replication, we treated infected cells with integrated stress response inhibitor (ISRIB), a chemical that reverses the effects of eIF2α phosphorylation (28). Using microscopy to monitor PV expansion (Fig. 4A), ISRIB reduced the PV area from ∼600 μm2 to ∼250 μm2 compared to that in untreated cells (Fig. 4B), suggesting eIF2α phosphorylation is crucial for bacterial replication niche development. Next, fluorescence-based growth curve analysis was used to determine the importance of eIF2α for bacterial replication. We observed a significant decrease in bacterial growth in ISRIB-treated cells compared to that in untreated cells with wild-type infection alone (Fig. 4C). Reduction in bacterial replication in ISRIB-treated infected samples was confirmed by quantification of bacterial genomes (see Fig. S2). Together, these results indicate eIF2α activity is essential for C. burnetii PV formation and bacterial proliferation.

FIG 4.

eIF2α activity is required for C. burnetii intracellular growth. (A) C. burnetii-infected THP-1 cells (72 hpi) in the presence or absence of ISRIB (10 μM) were processed for microscopy using antibodies against C. burnetii (violet) and CD63 (green), and DAPI stained DNA (blue). (B) The areas of >50 PVs were measured under each condition. ****, P < 0.0001, and error bars indicate the standard deviations from the means. ISRIB significantly decreased PV size. (C) THP-1 cells were infected with mCherry-expressing C. burnetii for 9 days in the presence or absence of ISRIB (10 μM). mCherry fluorescence was compared to that in uninfected cells. *, P < 0.05, and error bars indicate the standard deviations from the means. eIF2α activity is necessary for efficient C. burnetii intracellular growth.

To address possible mechanisms of decreased PV expansion and bacterial replication in macrophages treated with ISRIB, we assessed autophagosome association with the PV. C. burnetii actively engages autophagy by recruiting microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3)-positive autophagosomes to the PV in a T4SS-dependent manner, and progression through the autophagic pathway increases PV formation and bacterial load (29, 30). Figure 5A and B show that infected cells treated with ISRIB contained significantly fewer LC3-positive PVs than untreated cells. These data suggest C. burnetii is unable to recruit existing autophagosomes when eIF2α activity is suppressed, hindering progression through the autophagic pathway.

FIG 5.

Inhibition of eIF2α activity prevents autophagosome recruitment to the PV. (A) C. burnetii-infected THP-1 cells in the presence or absence of ISRIB (10 μM) were processed for microscopy using antibodies against LC3 (red) and CD63 (green), and DAPI stained bacterial and host DNA (blue). (B) PV areas were measured from >50 cells. **, P < 0.01, and error bars indicate the standard deviations from the means. eIF2α activity was required for LC3 decoration of the PV membrane.

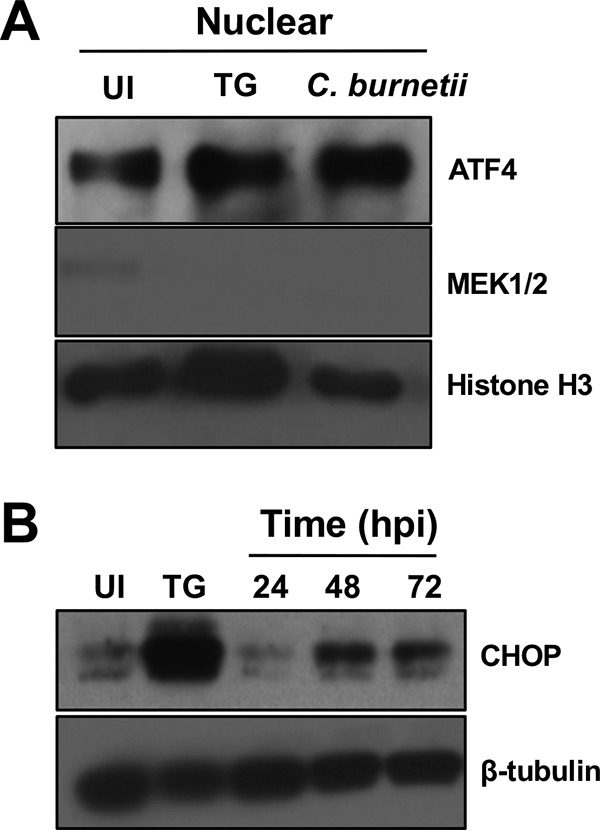

ATF4 and CHOP are produced during C. burnetii infection.

Downstream effects of eIF2α phosphorylation include production and nuclear translocation of ATF4 (9). atf4 expression increases at the peak of C. muridarum infection and aids amino acid transport and resistance to oxidative stress (27). C. burnetii is auxotrophic for 11 amino acids (31) and also combats intravacuolar ROS (32). Thus, to assess whether ATF4 is modulated by C. burnetii, we investigated ATF4 protein production and nuclear translocation in infected THP-1 cells compared to that in uninfected and TG-treated cells. Figure 6A shows increased levels of nuclear ATF4 in infected cells and TG-treated cells compared to that in uninfected cells. Nuclear ATF4 activity increases expression and production of CHOP following induction of the UPR (9). As shown in Fig. 6B, CHOP levels increased substantially during infection compared to that in uninfected cells. These results suggest that C. burnetii triggers increased production and nuclear localization of ATF4, culminating in the production of proapoptotic CHOP.

FIG 6.

ATF4 and CHOP are produced in C. burnetii-infected cells. (A) Immunoblot analysis of ATF4 in nuclear fractions was performed at 72 hpi. Histone H3 served as the loading control. TG served as the positive control. Levels of nuclear ATF4 increased in infected cells. (B) Immunoblot analysis of CHOP in whole-cell lysates (24 to 72 hpi) showed that higher levels of CHOP are produced in infected cells than in uninfected cells. β-Tubulin served as the loading control.

C. burnetii antagonizes ER stress-induced apoptosis in a T4SS-dependent manner.

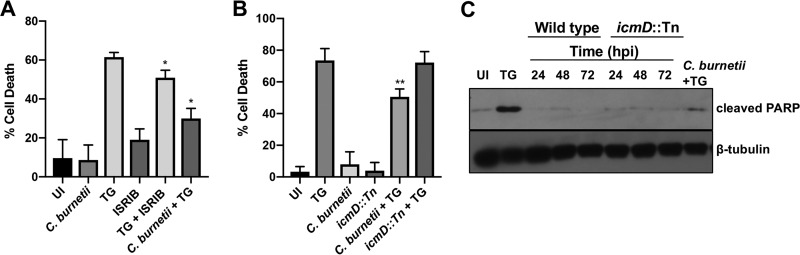

C. burnetii actively prevents intrinsic and extrinsic host cell apoptosis using T4SS effectors to alter host signaling (5, 33–35). TG-induced ER stress leads to cell death through multiple mechanisms, including CHOP-induced apoptosis following mitochondrial permeabilization, cytochrome c release, tribbles homolog 3 (TRB3) production, and inhibition of Bcl-2 family protein activity (36). As proapoptotic CHOP is produced during C. burnetii infection, but infected cells do not undergo apoptosis, we assessed whether C. burnetii actively prevents TG-induced cell death. As shown in Fig. 7A, C. burnetii infection did not trigger significant cell death as expected, while TG treatment resulted in ∼60% cell death. When C. burnetii-infected cells were treated with TG, cell death significantly decreased compared to that with TG alone (∼30%), suggesting C. burnetii antagonizes TG-induced apoptosis. We next assessed whether C. burnetii prevention of TG-induced death requires a functional T4SS. We performed viability assays comparing IcmD mutant-infected cells to cells infected with wild-type bacteria. Figure 7B shows that significant rescue of TG-induced cell death occurred in wild-type C. burnetii-infected cells but not IcmD mutant-infected cells, indicating C. burnetii uses T4SS effectors to prevent TG-induced cell death.

FIG 7.

C. burnetii antagonizes TG-induced apoptosis in a T4SS-dependent manner. (A) Cell death was assessed in THP-1 cells infected with wild-type C. burnetii and treated with ISRIB (10 μM) and compared to that in uninfected (UI) and TG-treated cells. ISRIB combined with TG treatment provided proof of concept for rescue of TG-induced death by reversing eIF2α phosphorylation. C. burnetii efficiently inhibits TG-induced death. (B) Cell death was assessed in THP-1 cells infected with wild-type or IcmD mutant bacteria using control conditions as for the data shown in panel A. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; error bars indicate the standard deviations from the means. IcmD-deficient C. burnetii did not rescue cells from TG-induced death. (C) Immunoblot analysis of cells infected with wild-type or IcmD mutant bacteria (24 to 72 hpi) and TG-treated C. burnetii-infected cells (72 hpi) was conducted using an antibody against cleaved PARP. Uninfected (UI) and TG-treated cells served as controls, and β-tubulin served as the loading control. C. burnetii antagonized TG-induced PARP cleavage, indicating decreased apoptosis.

To determine if C. burnetii specifically antagonizes TG-induced apoptotic cell death, we next analyzed cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP). PARP typically repairs DNA to promote genome stability; however, cleavage of PARP by caspase-3 inactivates the protein’s repair function and is a classical marker of apoptosis (16). Therefore, we assessed levels of cleaved PARP in infected THP-1 cells and cells treated with TG. Compared to that in uninfected and C. burnetii-infected cells, TG-treated cells contained increased levels of cleaved PARP (Fig. 7C). In contrast, C. burnetii-infected cells treated with TG contained decreased levels of cleaved PARP compared to levels in those with TG treatment alone. These data suggest C. burnetii actively antagonizes TG-induced apoptosis.

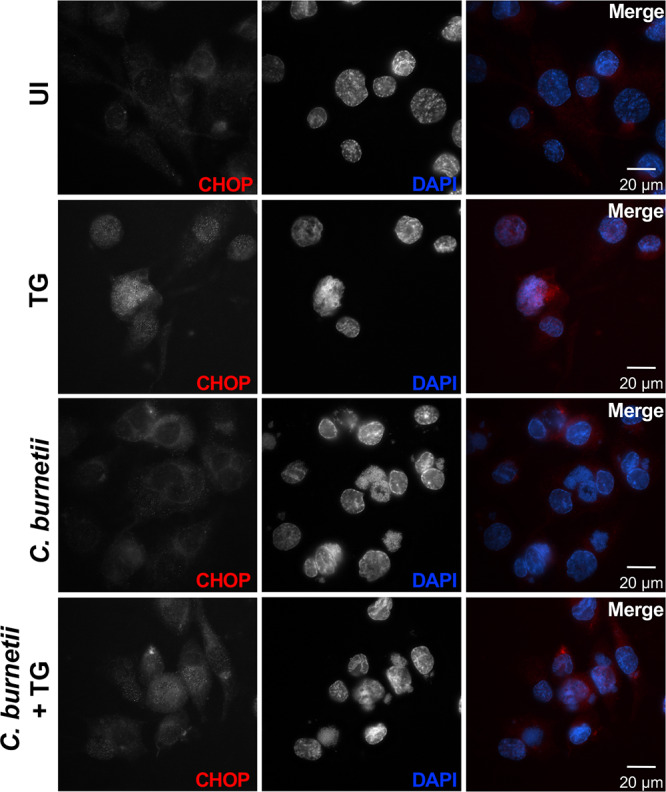

CHOP does not localize to the nucleus during C. burnetii infection.

After canonical activation of the eIF2α pathway, CHOP translocates to the nucleus, regulates Bcl-2 family protein production, and upregulates and interacts with TRB3, ultimately triggering apoptotic cell death (37). Interestingly, C. burnetii actively prevents apoptosis despite CHOP production. Therefore, we assessed CHOP localization in C. burnetii-infected cells. Microscopy analysis revealed that TG-treated cells contained obvious nuclear CHOP as expected (Fig. 8; see Fig. S3, black arrows). In contrast, CHOP did not preferentially localize to the nucleus of C. burnetii-infected or uninfected control cells. In C. burnetii-infected cells treated with TG, we observed reduced CHOP localization to the nucleus compared to that with TG treatment alone (Fig. 8). While overall CHOP intensity was increased in TG-treated infected cells compared to that in uninfected (UI) cells and those with infection alone, C. burnetii infection antagonized TG-induced nuclear localization, as evidenced by increased intensity of CHOP in the cytoplasm (Fig. S3, asterisks). These results indicate that while CHOP protein levels increase during infection, C. burnetii prevents increased CHOP nuclear localization as an effective method for preventing ER stress-induced apoptosis.

FIG 8.

CHOP does not localize to the nucleus of C. burnetii-infected cells. Uninfected (UI), TG-treated, C. burnetii-infected, or C. burnetii-infected TG-treated THP-1 cells were processed for microscopy using an antibody against CHOP (red), and DAPI (blue) was used to visualize bacterial and host DNA. Increased CHOP was present in the nuclei of TG-treated cells (positive control) but did not localize to the nuclei of C. burnetii-infected cells or uninfected cells. CHOP nuclear translocation was decreased in TG-treated infected cells compared to that in cells with TG treatment alone, indicating C. burnetii actively prevents CHOP nuclear translocation.

DISCUSSION

Here, we investigated the importance of the host UPR during C. burnetii infection of human macrophage-like cells, identifying a critical role for eIF2α in PV formation and bacterial replication. Several intracellular pathogens trigger the UPR to enhance survival and promote intracellular growth. For example, Brucella spp. and Salmonella spp. use secreted proteins to induce the UPR and promote efficient intracellular replication (14, 38). Likewise, ER stress-reducing TUDCA alters C. burnetii PV fusion events and Bcl-2 recruitment but does not prevent bacterial replication. Interestingly, eIF2α-specific ISRIB limits LC3 recruitment to the PV, inhibits proper vacuole formation, and antagonizes C. burnetii growth. Thus, C. burnetii usurps distinct components of the UPR to promote infection, adding a novel component to our understanding of unique mechanisms used by intracellular pathogens to parasitize host cells.

The UPR consists of three major yet distinct arms that are activated in response to different stresses. The IRE1α and ATF6 branches of the UPR are not activated during C. burnetii infection, contrary to reports of other pathogens, such as S. aureus and L. pneumophila, respectively (13, 25). However, it remains unknown whether C. burnetii actively prevents activation of these arms or simply never stimulates either pathway. In contrast to the pathogens mentioned above, C. burnetii infection of human macrophage-like cells triggers eIF2α activation downstream of PERK, highlighting the selective response to infection. Activation of eIF2α is an effector-driven process, as infection with T4SS-defective C. burnetii does not increase levels of phosphorylated eIF2α. Currently, the specific effector(s) responsible is unknown. Potential candidate effectors include CBU0372, CBU1825, and CBU1576, which localize to the ER and/or disrupt host cell secretory transport (6), and CpeC, CirA, and CBU1379a that reportedly interact with UPR-related components (39). The ability of these effectors to activate eIF2α signaling awaits future testing.

In contrast to general relief of the UPR using TUDCA, eIF2α activation is required for both PV expansion and C. burnetii replication, as prevention of protein activity reduces PV area and decreases bacterial numbers. A likely mechanism for this reduction is inefficient autophagosome recruitment, an event that is required for efficient intracellular growth by providing nutrients and membrane for C. burnetii and the expanding PV, respectively (3, 29). Autophagosomal LC3 is not efficiently recruited to PV in eIF2α-inhibited cells, suggesting C. burnetii uses UPR components to engage autophagy and promote vacuole expansion. Activation of the eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP pathway is implicated in the induction of autophagy-related gene expression. Importantly, expression of multiple autophagy-associated genes requires ATF4 binding to the amino acid response element (AARE), independent of CHOP (40). ATF4 is produced during C. burnetii infection, and it is plausible that nuclear translocation of the protein results in induction of autophagy. Thus, ISRIB likely prevents expression of autophagic genes downstream of eIF2α activation, resulting in decreased localization of LC3 to the PV.

Additional downstream aspects of eIF2α activation, including nuclear translocation of ATF4 and consequent production of proapoptotic CHOP, occur during C. burnetii infection, but these events do not result in apoptosis of infected host cells, contrary to the canonical effects of prolonged UPR activation. C. burnetii actively prevents host cell apoptosis, including TG-induced death, in a T4SS-dependent manner. C. burnetii actively inhibits increased CHOP translocation to the nucleus, highlighting a second potential effector-mediated event related to the UPR. Similarly, the intracellular chlamydial organism Simkania negevensis, which harbors a T4SS and a type III secretion system (T3SS), blocks nuclear translocation of CHOP during ER stress in HeLa cells (41). While the mechanism of how C. burnetii prevents CHOP nuclear translocation is unknown, the benefits to host cell parasitism are clear. C. burnetii requires sustained activation of the master cell survival regulator protein kinase B (Akt) to maintain host cell viability (42). CHOP promotes expression of TRB3, an intracellular pseudokinase that directly inhibits Akt activity by binding to Ser473 and Thr308, preventing phosphorylation of Akt at these residues and triggering apoptosis (43, 44). However, these sites are phosphorylated during C. burnetii infection (42), indicating the pathogen prevents this CHOP activity. CHOP also inhibits expression of Bcl-2, which interacts with the autophagy protein beclin-1 in C. burnetii-infected cells (20). Decreased Bcl-2 production during infection would prevent interplay between these two proteins, disrupting the ability of the pathogen to modulate autophagy and apoptosis. However, Bcl-2 levels remain stable in C. burnetii-infected cells (45), again demonstrating the pathogen blocks CHOP-dependent gene regulation. Together, these findings further expand our understanding of methods used by C. burnetii to ensure long-term viability of host cells.

While ER stress activates the PERK pathway of the UPR leading to eIF2α phosphorylation, three additional kinases can also regulate this event. Further work is needed to determine if PERK, general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2), protein kinase R (PKR), and/or heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI) activate eIF2α during C. burnetii infection. PERK dimerizes and autophosphorylates in response to ER stress when BiP dissociates from an inactive receptor to chaperone unfolded proteins in the ER, and UPR activation is often assessed by increased BiP production. For example, Brucella melitensis upregulates the UPR in macrophages, evidenced by increased BiP translation (14). In contrast, BiP levels do not increase during C. burnetii infection (data not shown), suggesting another kinase may be responsible for eIF2α activation. HRI is essential to the virulence of intracellular bacteria, including Yersinia and Listeria, by promoting proper type III secretion system (T3SS) function and postinvasion trafficking, respectively (46). GCN2 triggers eIF2α phosphorylation in response to amino acid starvation during Salmonella intracellular infection and triggers an inflammatory cytokine response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (47). PKR, historically regarded as a viral stress response element, is also stimulated by LPS and inflammatory cytokines. Avirulent C. burnetii, used in this study, triggers proinflammatory cytokine production during early stages of infection (48) but contains a truncated LPS compared to that in virulent isolates, highlighting the need to investigate the potential role of GCN2 and PKR during C. burnetii growth in macrophages. Moreover, C. burnetii elicits increased levels of phosphorylated c-Jun and phosphorylated Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) at early times postinfection (42), further suggesting a role for PKR activation (49).

Collectively, the present results demonstrate that C. burnetii engages distinct components of the host UPR and that eIF2α activity is essential for C. burnetii replication in human macrophages. Importantly, C. burnetii prevents consequent ER stress-induced apoptosis in a T4SS-dependent manner, adding to our ability to model pathogen manipulation of host cell death. Future investigation of the interplay between C. burnetii and the eIF2α pathway, and the T4SS effectors responsible, will advance understanding of the pathogen’s ability to trigger specific host responses that are critical for intracellular survival and disease progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eukaryotic cell culture.

THP-1 human monocytes (TIB-202; American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in 5% CO2. Overnight treatment of THP-1 cells with phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA; 200 nM) was used to differentiate monocytes into adherent macrophage-like cells. Medium containing PMA was removed 24 h prior to infection and replaced with fresh medium lacking PMA. All samples in respective experiments were collected at a single time point postseeding.

C. burnetii cultivation.

Wild type C. burnetii (avirulent Nine Mile II [NMII], RSA 439, clone 4) was cultured in acidified citrate cysteine medium (ACCM) for 7 days at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 2.5% O2. For mCherry-expressing bacteria, chloramphenicol (3 μg/ml) was added to ACCM cultures, and IcmD mutant bacteria (icmD::Tn) were grown in ACCM containing kanamycin (350 μg/ml). At 7 days postinoculation, cultures were collected by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in sucrose phosphate (SP) buffer. C. burnetii stocks were stored in SP buffer at −80°C. Infections were performed using a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 to 30.

C. burnetii growth curve and genome equivalent analysis.

THP-1 cells were cultured in black-wall, 96-well glass-bottom plates in phenol red-free medium. Cells were infected with mCherry-expressing C. burnetii and inhibitors were added daily (TUDCA [Calbiochem], 500 μg/ml; ISRIB [Sigma], 10 μM). Relative mCherry fluorescence (excitation, 585 nm; emission, 620 nm) was measured from 1 to 9 dpi using a Synergy H1 plate reader (BioTek). Fluorescence readings from mCherry-expressing C. burnetii-infected cells were compared to those from uninfected control cells in each experiment. To complement fluorescence-based data, standard genome equivalent assays were performed for the conditions described above. Briefly, THP-1 cells were harvested by scraping and centrifugation, followed by DNA isolation (Qiagen DNeasy Ultraclean Microbial kit) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Genomes were enumerated in duplicates using quantitative PCR as described previously (50).

Immunoblot analysis.

Cells were lysed in buffer containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; 1%), Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 7.4), EDTA (5 mM), and protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma). Ten micrograms of total protein was separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10% or 4% to 15%) and transferred to a 0.2-μm pore polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with Tris-buffered saline (150 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6]) containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Membranes were probed overnight at 4°C with antibodies against human BiP (Cell Signaling), phosphorylated (p)-eIF2α (Cell Signaling), eIF2α (Cell Signaling), ATF4 (Cell Signaling), CHOP (Cell Signaling), XBP1s (Cell Signaling), ATF6 (Abcam), histone H3 (Cell Signaling), MEK1/2 (Cell Signaling), or cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP; Cell Signaling) in 5% nonfat milk or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were used, and WesternBright chemiluminescence reagents (Advansta) allowed visualization of proteins. β-Tubulin (Sigma) served as the loading control.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 3 min and then incubated overnight at 4°C in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% BSA to block nonspecific binding. Samples were incubated with antibodies against CD63 (BD Biosciences), Bcl-2 (Cell Signaling), LC3B (Cell Signaling), CHOP (Cell Signaling), or C. burnetii for 1 h at RT. Samples were washed 3 times with PBS, and respective secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, 594, or 647 (Invitrogen) were incubated with samples for 1 h at RT. Samples were visualized using a Ti-U microscope with a 40× dry or 60× oil immersion lens objective, and images were captured with a D5-QilMc digital camera (Nikon). All images were analyzed using NIS-Elements software (Nikon). PV area was determined using NIS-Elements 5-point area measurement analysis.

Cell fractionation.

THP-1 cells were harvested by scraping into PBS and centrifuging at 600 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Nuclear extracts were separated from cytosolic fractions using a BioVision nuclear/cytosol extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracts were stored at −80°C prior to analysis. Immunoblot analysis was used to detect proteins in respective fractions. Histone H3 (Cell Signaling) and MEK 1/2 (Cell Signaling) served as the nuclear and cytoplasmic controls, respectively.

Cell viability assays.

A colorimetric Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo) was used to determine cell viability according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Uninfected THP-1 cells were compared to cells treated with ISRIB (10 μM) for 72 h, cells infected with wild-type or icmD::Tn C. burnetii for 72 h, and cells treated with thapsigargin (TG; 2 μM) (Abcam) for 24 h. TG served as the positive control for ER stress-induced cell death. WST-8 [2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, monosodium salt] was then added to each sample in a 96-well plate for 4 h at 37°C. A450 was measured for each condition, and cell viability was calculated using the formula [(Atest − Abackground)/(Acontrol − Abackground)] × 100. Medium alone served as the background control, and untreated uninfected cells served as the negative control.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using unpaired, parametric Student’s t tests (GraphPad Prism 8). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant, as indicated in individual figures. All data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments unless otherwise noted.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by funding to D.E.V. from the NIH/NIAID (R21AI127931), the NIH/NIGMS (P20GM103625), and the Arkansas Biosciences Institute.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson A, Bijlmer H, Fournier PE, Graves S, Hartzell J, Kersh GJ, Limonard G, Marrie TJ, Massung RF, McQuiston JH, Nicholson WL, Paddock CD, Sexton DJ. 2013. Diagnosis and management of Q fever–United States, 2013: recommendations from CDC and the Q Fever Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep 62:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooke RJ, Kretzschmar ME, Mutters NT, Teunis PF. 2013. Human dose response relation for airborne exposure to Coxiella burnetii. BMC Infect Dis 13:488. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voth DE, Heinzen RA. 2007. Lounging in a lysosome: the intracellular lifestyle of Coxiella burnetii. Cell Microbiol 9:829–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Schaik EJ, Chen C, Mertens K, Weber MM, Samuel JE. 2013. Molecular pathogenesis of the obligate intracellular bacterium Coxiella burnetii. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:561–573. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beare PA, Gilk SD, Larson CL, Hill J, Stead CM, Omsland A, Cockrell DC, Howe D, Voth DE, Heinzen RA. 2011. Dot/Icm type IVB secretion system requirements for Coxiella burnetii growth in human macrophages. mBio 2:e00175-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00175-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber MM, Chen C, Rowin K, Mertens K, Galvan G, Zhi H, Dealing CM, Roman VA, Banga S, Tan Y, Luo ZQ, Samuel JE. 2013. Identification of Coxiella burnetii type IV secretion substrates required for intracellular replication and Coxiella-containing vacuole formation. J Bacteriol 195:3914–3924. doi: 10.1128/JB.00071-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey KL, Newton HJ, Luhrmann A, Roy CR. 2011. The Coxiella burnetii Dot/Icm system delivers a unique repertoire of type IV effectors into host cells and is required for intracellular replication. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002056. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham JG, Winchell CG, Sharma UM, Voth DE. 2015. Identification of ElpA, a Coxiella burnetii pathotype-specific Dot/Icm type IV secretion system substrate. Infect Immun 83:1190–1198. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02855-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. 2005. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Biochem 74:739–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cullinan SB, Diehl JA. 2006. Coordination of ER and oxidative stress signaling: the PERK/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 38:317–332. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pillich H, Loose M, Zimmer KP, Chakraborty T. 2012. Activation of the unfolded protein response by Listeria monocytogenes. Cell Microbiol 14:949–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodino KG, VieBrock L, Evans SM, Ge H, Richards AL, Carlyon JA. 2017. Orientia tsutsugamushi modulates endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation to benefit its growth. Infect Immun 86:e00596-17. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00596-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treacy-Abarca S, Mukherjee S. 2015. Legionella suppresses the host unfolded protein response via multiple mechanisms. Nat Commun 6:7887. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith JA, Khan M, Magnani DD, Harms JS, Durward M, Radhakrishnan GK, Liu YP, Splitter GA. 2013. Brucella induces an unfolded protein response via TcpB that supports intracellular replication in macrophages. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003785. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howe D, Shannon JG, Winfree S, Dorward DW, Heinzen RA. 2010. Coxiella burnetii phase I and II variants replicate with similar kinetics in degradative phagolysosome-like compartments of human macrophages. Infect Immun 78:3465–3474. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00406-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voth DE, Howe D, Heinzen RA. 2007. Coxiella burnetii inhibits apoptosis in human THP-1 cells and monkey primary alveolar macrophages. Infect Immun 75:4263–4271. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00594-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Justis AV, Hansen B, Beare PA, King KB, Heinzen RA, Gilk SD. 2017. Interactions between the Coxiella burnetii parasitophorous vacuole and the endoplasmic reticulum involve the host protein ORP1L. Cell Microbiol 19:e12637. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seyhun E, Malo A, Schafer C, Moskaluk CA, Hoffmann RT, Goke B, Kubisch CH. 2011. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress, acinar cell damage, and systemic inflammation in acute pancreatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301:G773–G782. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00483.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodrigues CM, Sola S, Nan Z, Castro RE, Ribeiro PS, Low WC, Steer CJ. 2003. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid reduces apoptosis and protects against neurological injury after acute hemorrhagic stroke in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:6087–6092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031632100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vazquez CL, Colombo MI. 2010. Coxiella burnetii modulates Beclin 1 and Bcl-2, preventing host cell apoptosis to generate a persistent bacterial infection. Cell Death Differ 17:421–438. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilk SD. 2012. Role of lipids in Coxiella burnetii infection. Adv Exp Med Biol 984:199–213. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4315-1_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howe D, Heinzen RA. 2006. Coxiella burnetii inhabits a cholesterol-rich vacuole and influences cellular cholesterol metabolism. Cell Microbiol 8:496–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lytton J, Westlin M, Hanley MR. 1991. Thapsigargin inhibits the sarcoplasmic or endoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase family of calcium pumps. J Biol Chem 266:17067–17071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park SW, Zhou Y, Lee J, Lee J, Ozcan U. 2010. Sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2b is a major regulator of endoplasmic reticulum stress and glucose homeostasis in obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:19320–19325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012044107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abuaita BH, Burkholder KM, Boles BR, O'Riordan MX. 2015. The endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor inositol-requiring enzyme 1alpha augments bacterial killing through sustained oxidant production. mBio 6:e00705-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00705-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taguchi Y, Imaoka K, Kataoka M, Uda A, Nakatsu D, Horii-Okazaki S, Kunishige R, Kano F, Murata M. 2015. Yip1A, a novel host factor for the activation of the IRE1 pathway of the unfolded protein response during Brucella infection. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004747. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.George Z, Omosun Y, Azenabor AA, Partin J, Joseph K, Ellerson D, He Q, Eko F, Bandea C, Svoboda P, Pohl J, Black CM, Igietseme JU. 2017. The roles of unfolded protein response pathways in Chlamydia pathogenesis. J Infect Dis 215:456–465. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sidrauski C, McGeachy AM, Ingolia NT, Walter P. 2015. The small molecule ISRIB reverses the effects of eIF2alpha phosphorylation on translation and stress granule assembly. Elife 4:e05033. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winchell CG, Graham JG, Kurten RC, Voth DE. 2014. Coxiella burnetii type IV secretion-dependent recruitment of macrophage autophagosomes. Infect Immun 82:2229–2238. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01236-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutierrez MG, Vazquez CL, Munafo DB, Zoppino FC, Beron W, Rabinovitch M, Colombo MI. 2005. Autophagy induction favours the generation and maturation of the Coxiella-replicative vacuoles. Cell Microbiol 7:981–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandoz KM, Beare PA, Cockrell DC, Heinzen RA. 2016. Complementation of arginine auxotrophy for genetic transformation of Coxiella burnetii by use of a defined axenic medium. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:3042–3051. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00261-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brennan RE, Russell K, Zhang G, Samuel JE. 2004. Both inducible nitric oxide synthase and NADPH oxidase contribute to the control of virulent phase I Coxiella burnetii infections. Infect Immun 72:6666–6675. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6666-6675.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bisle S, Klingenbeck L, Borges V, Sobotta K, Schulze-Luehrmann J, Menge C, Heydel C, Gomes JP, Lührmann A. 2016. The inhibition of the apoptosis pathway by the Coxiella burnetii effector protein CaeA requires the EK repetition motif, but is independent of survivin. Virulence 7:400–412. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1139280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klingenbeck L, Eckart RA, Berens C, Luhrmann A. 2013. The Coxiella burnetii type IV secretion system substrate CaeB inhibits intrinsic apoptosis at the mitochondrial level. Cell Microbiol 15:675–687. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luhrmann A, Nogueira CV, Carey KL, Roy CR. 2010. Inhibition of pathogen-induced apoptosis by a Coxiella burnetii type IV effector protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:18997–19001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004380107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohoka N, Yoshii S, Hattori T, Onozaki K, Hayashi H. 2005. TRB3, a novel ER stress-inducible gene, is induced via ATF4-CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death. EMBO J 24:1243–1255. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iurlaro R, Munoz-Pinedo C. 2016. Cell death induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. FEBS J 283:2640–2652. doi: 10.1111/febs.13598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antoniou AN, Lenart I, Kriston-Vizi J, Iwawaki T, Turmaine M, McHugh K, Ali S, Blake N, Bowness P, Bajaj-Elliott M, Gould K, Nesbeth D, Powis SJ. 2019. Salmonella exploits HLA-B27 and host unfolded protein responses to promote intracellular replication. Ann Rheum Dis 78:74–82. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallqvist A, Wang H, Zavaljevski N, Memisevic V, Kwon K, Pieper R, Rajagopala SV, Reifman J. 2017. Mechanisms of action of Coxiella burnetii effectors inferred from host-pathogen protein interactions. PLoS One 12:e0188071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.B'chir W, Maurin A-C, Carraro V, Averous J, Jousse C, Muranishi Y, Parry L, Stepien G, Fafournoux P, Bruhat A. 2013. The eIF2alpha/ATF4 pathway is essential for stress-induced autophagy gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res 41:7683–7699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehlitz A, Karunakaran K, Herweg JA, Krohne G, van de Linde S, Rieck E, Sauer M, Rudel T. 2014. The chlamydial organism Simkania negevensis forms ER vacuole contact sites and inhibits ER-stress. Cell Microbiol 16:1224–1243. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Voth DE, Heinzen RA. 2009. Sustained activation of Akt and Erk1/2 is required for Coxiella burnetii antiapoptotic activity. Infect Immun 77:205–213. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01124-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang W, Cheng J, Sun A, Lv S, Liu H, Liu X, Guan G, Liu G. 2015. TRB3 mediates renal tubular cell apoptosis associated with proteinuria. Clin Exp Med 15:167–177. doi: 10.1007/s10238-014-0287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cravero JD, Carlson CS, Im HJ, Yammani RR, Long D, Loeser RF. 2009. Increased expression of the Akt/PKB inhibitor TRB3 in osteoarthritic chondrocytes inhibits insulin-like growth factor 1-mediated cell survival and proteoglycan synthesis. Arthritis Rheum 60:492–500. doi: 10.1002/art.24225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luhrmann A, Roy CR. 2007. Coxiella burnetii inhibits activation of host cell apoptosis through a mechanism that involves preventing cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Infect Immun 75:5282–5289. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00863-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shrestha N, Boucher J, Bahnan W, Clark ES, Rosqvist R, Fields KA, Khan WN, Schesser K. 2013. The host-encoded heme regulated inhibitor (HRI) facilitates virulence-associated activities of bacterial pathogens. PLoS One 8:e68754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castilho BA, Shanmugam R, Silva RC, Ramesh R, Himme BM, Sattlegger E. 2014. Keeping the eIF2 alpha kinase Gcn2 in check. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843:1948–1968. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dragan AL, Kurten RC, Voth DE. 2019. Characterization of early stages of human alveolar infection by the Q fever agent Coxiella burnetii. Infect Immun 87:e00028-19. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00028-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams BR. 2001. Signal integration via PKR. Sci STKE 2001:re2. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.89.re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Graham JG, MacDonald LJ, Hussain SK, Sharma UM, Kurten RC, Voth DE. 2013. Virulent Coxiella burnetii pathotypes productively infect primary human alveolar macrophages. Cell Microbiol 15:1012–1025. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.