Abstract

Background

Tigecycline is a last-resort antibiotic used to treat severe infections caused by extensively drug-resistant bacteria. Recently, novel tigecycline resistance genes tet(X3) and tet(X4) have been reported, which pose a great challenge to human health and food security. The current study aimed to establish a TaqMan-based real-time PCR assay for the rapid detection of the tigecycline-resistant genes tet(X3) and tet(X4).

Results

No false-positive result was found, and the results of the TaqMan-based real-time PCR assay showed 100% concordance with the results of the sequencing analyses. This proposed method can detect the two genes at the level of 1 × 102 copies/μL, and the whole process is completed within an hour, allowing rapid screening of tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes in cultured bacteria, faeces, and soil samples.

Conclusion

Taken together, the TaqMan-based real-time PCR method established in this study is rapid, sensitive, specific, and is capable of detecting the two genes not only in bacteria, but also in environmental samples.

Keywords: Tigecycline resistance, TaqMan, Real-time PCR

Background

With the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), only a few antibiotics are available to treat severe infections caused by extensively drug-resistant (XDR) bacteria, which poses a great challenge to human health and food security. Tigecycline and colistin are last-resort drugs to treat infections caused by carbapenem-resistance Enterobacteriaceae [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) classified the two antibiotics as critically important antimicrobials, and their usage should be severely restricted (http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/antimicrobials-fifth/en/) [2]. Since the recent reports of colistin resistance genes (mcr), the clinical application of colistin has become more limited [2, 3], turning tigecycline into the ultimate treatment option.

In May 2019, two tigecycline resistance genes, tet(X3) and tet(X4), were discovered, which can inactivate the entire family of tetracycline antibiotics, including tigecycline and the newly US FDA-approved drugs eravacycline and omadacycline [4]. Tet(X3) and tet(X4) are the first plasmid-borne tet(X) genes, encoding proteins with 386 amino acids and 385 amino acids, respectively, and showing 85.1 and 94.3% identity, respectively, with the original tet(X) from Bacterioides fragilis [4, 5].

To date, both genes have been identified in humans, animals, meat, and environmental samples [4, 6–8]. In three representative provinces of China, tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes have been identified in animals and meat for consumption at a high proportion of 43.3% [4], indicating the wide transmission of tigecycline resistance. Recent studies showed that the presence of tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes can significantly increase the resistance to tigecycline, and the construction of a tet(X4)-containing bacterial strain, namely, Escherichia coli JM109 + pBAD24-tet(X4), increases the MIC value of tigecycline by 64-fold compared with the original host strain [8].

Therefore, it is necessary to establish an efficient method for simultaneous screening the tigecycline-resistant genes tet(X3) and tet(X4) in different samples. Nowadays, real-time PCR assays are widely used in laboratories domestically and overseas. Compared to conventional PCR, real-time PCR has superior sensitivity, reproducibility, precision, and high throughput capability [9]. In this study, we designed a rapid, sensitive TaqMan-based multiplex real-time PCR assay for the specific detection of the tigecycline resistance genes tet(X3) and tet(X4), and further evaluated using cultured bacteria, faeces and soil samples.

Results

Primers and probes

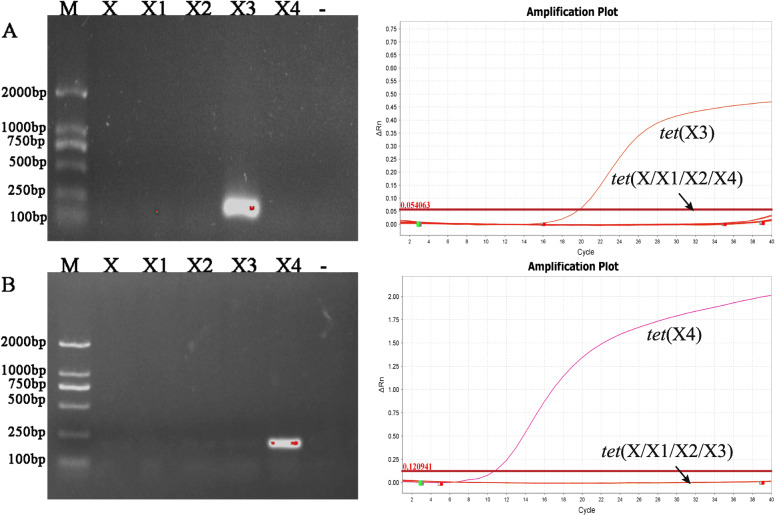

The results of the NCBI Primer BLAST module indicated that no genes other than tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes matched the primer sequences designed in this study. Similarly, the results of conventional and real-time PCR also indicated the high specificity of primers and probes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Conventional PCR amplification and real-time PCR amplification curve for tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes. a–b were the electrophoresis gel (left) and amplification curve (right) of tet(X3) and tet(X4). M: Marker. -: negative control. X3 was tet(X3) positive strain. X4 was tet(X4) positive strain. X, X1, X2 were negative strains

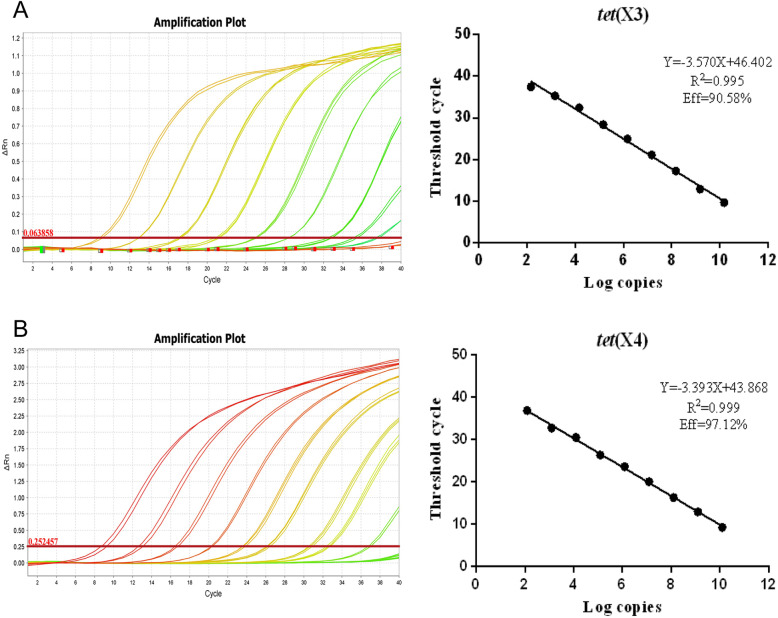

Real-time PCR and standard curve analysis

Standard curves were obtained using 10-fold serial dilutions of plasmids pTET(X3) and pTET(X4), containing the tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes to determine the detection limit of the proposed method. The detection range of copies was 1.49 × 102–1.49 × 1010 copies/μL for tet(X3) and 1.23 × 102–1.23 × 1010 copies/μL for tet(X4), and cycle threshold (CT) ranges were 37.435–9.663 for tet(X3) and 36.894–9.273 for tet(X4).

Linear standard curves for real-time PCR are shown in Fig. 2. The amplification efficiencies were calculated using the formula E = 10(− 1/slope) − 1 [10]. R2 values were 0.995 and 0.999, respectively, and efficiency was 90.58 and 97.12% for the tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes, respectively. The sensitivity of analysis was linear within the dynamic range of 9 dilutions. These results reveal that these two real-time PCR tests are accurate for quantitative detection of tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes.

Fig. 2.

Real-time PCR amplification curves and standard curves. a–b Show real-time PCR amplification curves and standard curves tet(X3) and tet(X4)

Specificity and sensitivity evaluation

To confirm the specificity of the assay, two E. coli DH5α strains carrying tet(X3) or tet(X4) were used as the positive control, while E. coli ATCC25922 and three E. coli DH5α strains containing tet(X), tet(X1) or tet(X2), respectively, were used as the negative control. Each sample was tested three times independently (n = 3). The results of TaqMan-based real-time PCR were 100% concordance with the results of conventional PCR (Table 1& Fig. 1), which proved that the two primer sets and probes were highly specific for their target gene.

Table 1.

Detection of tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes in isolates

| Isolate | Origin | Species | Gene | Gene Location | Real-time PCR for tet(X) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tet(X3) | tet(X4) | Ct ± SD | |||||

| ATCC25922 | – | E. coli | – | – | – | – | Undetermined |

| DH5α-tet(X) | – | E. coli | tet(X) | Plasmid | – | – | Undetermined |

| DH5α-tet(X1) | – | E. coli | tet(X1) | Plasmid | – | – | Undetermined |

| DH5α-tet(X2) | – | E. coli | tet(X2) | Plasmid | – | – | Undetermined |

| DH5α-tet(X3) | – | E. coli | tet(X3) | Plasmid | + | – | 9.66 ± 0.00 |

| DH5α-tet(X4) | – | E. coli | tet(X4) | Plasmid | – | + | 9.27 ± 0.00 |

| CB13 | Chicken | E. coli | tet(X3) | Plasmid | + | – | 19.05 ± 0.05 |

| CB14 | Chicken | E. coli | tet(X3) | Plasmid | + | – | 21.06 ± 0.08 |

| CB15 | Chicken | E. coli | tet(X3) | Plasmid | + | – | 19.24 ± 0.10 |

| CB42 | Chicken | E. coli | tet(X3) | Plasmid | + | – | 19.24 ± 0.16 |

| DZ47 | Chicken | E. coli | tet(X4) | Plasmid | – | + | 21.90 ± 0.12 |

| AZ28 | Chicken | E. coli | tet(X4) | Plasmid | – | + | 14.79 ± 0.01 |

| DZ4R | Chicken | A. baumannii | tet(X4) | Plasmid | – | + | 13.42 ± 0.07 |

| NM4 | Chicken | A. baumannii | tet(X4) | Plasmid | – | + | 14.23 ± 0.13 |

| DZ27 | Chicken | E. coli | tet(X4) | Plasmid | – | + | 17.76 ± 0.13 |

| DZ24 | Chicken | E. coli | tet(X4) | Plasmid | – | + | 14.35 ± 0.10 |

| DZ65 | Chicken | A. baumannii | tet(X4) | Plasmid | – | + | 21.05 ± 0.05 |

| DZ24 | Chicken | E. coli | tet(X4) | Plasmid | – | + | 18.33 ± 0.09 |

To further validate the method, genetic DNA extracted from bacteria, faeces and soil samples (three independent technical replicates) was selected to conduct the real-time PCR assay for screening. In this study, some E. coli and A. baumannii isolates of animal origin were selected for verification, including 4 tet(X3) positive strains and 8 tet(X4) positive strains (Table 1). The CT ranges were 19.05–21.06, 13.42–21.05 for tet(X3), tet(X4) genes (Table 1). The results of real-time PCR and previous sequencing analyses were completely consistent, showing high specificity of the method. Moreover, a total of 24 faeces and soil samples from chickens, pigs, and cattle were collected for further evaluation. We were able to detect the two genes in metagenomes extracted from 19 faeces and soil samples, and the relative abundance was normalized using 16S rRNA (gene copies/106 copies of the 16S rRNA gene) [11, 12]. The real-time PCR assay showed that the normalized copies range from 101 to 105 for genes tet(X3) and tet(X4) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Detection of tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes in faeces and soil samples. The relative abundance of tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes (copies /per 1,000,000 copies of 16S rRNA) in the soil and faeces samples

Discussion

Since the first discovery of the tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes, these two plasmid-mediated tigecycline resistance genes have been widely reported, suggesting that they are spreading at an alarming rate. It is noteworthy that the tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes have been identified not only in humans and animals, but also in the environment [4, 13, 14]. There is a pressing need to establish a fast screening assay for tigecycline resistance genes. So far, there are three reports of fast screening of tet(X3) and tet(X4), multiplex PCR methods, tetracycline inactivation method, and SYBR Green based real-time PCR, all three methods have approved the effectiveness of methods [15–17]. Compared to traditional detection methods, like conventional PCR and phenotypic method, real-time PCR assays are more sensitive, specific, time-efficient, and labour-saving [18]. Besides, real-time PCR methods can detect genes in different type of samples other than bacteria. Lately, Fu et al. reported a SYBR Green-based real-time PCR assay for rapid detection of tet(X) variants, with a detection limit range from 102 to 105, 1–103 per 106 copies of 16S rRNA for tet(X3) and tet(X4), respectively. To date, the method based on real-time PCR using TaqMan probe has not been previously proposed.

In this study, we developed a TaqMan-based multiplex real-time PCR assay for the detection of the tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes. Both tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes have been successfully identified not only in bacteria isolates, but also directly from faeces and soil samples, with a minimum of 1 copy per 105 copies of 16S rRNA and a maximum of 104 copies per 105 copies of 16S rRNA. Besides, we used constructed E. coli DH5α-tet(X) strains as positive control and bacteria isolates of animal origin to evaluate the specificity of the method. The E. coli ATCC25922 was used as negative control. In our method, only specific amplicons can be bonded by TaqMan probes, which is different from the SYBR-Green dye. The SYBR-Green can bind any double strand DNA fragments in the PCR reaction without any specificity, so melting curve analysis will be necessary to identify the single peak for the PCR reaction. According to the Fig. 1, our method has high specificity, whereas other tet(X) genes couldn’t be amplified. A limitation of the proposed method is that these genes cannot be detected simultaneously in a single reaction. However, there are no reports of the co-existence of these two genes. Because tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes are usually accompanied with MDR [9], different combinations of such detection methods are flexible and convenient.

Although tigecycline usage has never been approved in animal husbandry, tetracyclines have been widely used in China and many other countries. The total consumption of tetracyclines reached 13,666 tons in 2018 in China, which may provide ongoing selective pressure for the production of tigecycline resistance genes. Many studies have shown that tet(X4) can be captured by a range of mobile elements circulating among bacterial strains [4, 6–8], importantly, with the international trade of food-producing animals and their derivatives, a novel antibacterial mechanism may appear. It is of great importance to monitor and eradicate these genes, especially in countries with high tetracycline consumption.

Conclusion

Overall, we developed a TaqMan-based multiplex real-time PCR method in this study for the rapid detection of tigecycline resistance genes, tet(X3) and tet(X4). This assay can be widely applied to all laboratories equipped with a qPCR machine, and the whole process could be completed within an hour. It is highly sensitive and specific, and can detect and quantify tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes accurately in cultured bacteria isolates, faeces and environmental samples.

Methods

Bacteria strains and environmental samples

All the E. coli and A. baumannii strains from animal origin used in this study (Table 1) were collected from three poultry farm in Shandong Province, and were identified by conventional PCR and MALDI-TOF before. Five tet(X) variant genes were cloned into the PMD-19 T vector (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan), and then transferred into the DH5α cell, including DH5α-tet(X), DH5α-tet(X1), DH5α-tet(X2), DH5α-tet(X3) and DH5α-tet(X4) (Table 1). A total of 24 faeces and soil samples collected from chickens, pigs, and cattle farms from Sichuan Province were then used for further evaluation (Fig. 1).

DNA extraction

Bacteria were incubated at 37 °C in Brain Heart Infusion broth with agitation at 200 rpm to achieve enough colonies for DNA extraction. Hipure Bacterial DNA Kit (Magen, Guangdong, China) were used to extract bacterial genome according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The DNeasy PowerSoil (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used to extract metagenomic DNA from faeces and soil.

Primer and probe design

The nucleotide sequences of tet(X3) and tet(X4) were obtained from GenBank. The specific real-time PCR primers and TaqMan probes for these genes (Tables 2 & 3) were designed using Primer Express software (ABI-Applied Biosystems Incorporated, Foster City, CA), and the NCBI Primer-BLAST module (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ tools/primer-blast/) was used to initially validate their specificity. Then, conventional and real-time PCR were both conducted to evaluate the specificity of primers and probes.

Table 2.

Primers for real-time PCR detection of tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Gene | Product length | Accession No. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tet(X3)-qF | CAGGACAGAAACAGCGTTGC | tet(X3) | 179 bp | MK134375.1 | This study |

| tet(X3)-qR | GCAGCATCGCCAATCATTGT | ||||

| tet(X4)-qF | TTGGGACGAACGCTACAAAG | tet(X4) | 181 bp | MK134376.1 | This study |

| tet(X4)-qR | CATCAACCCGCTGTTTACGC |

Table 3.

Probes for detection of tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes

| Probe | Sequence (5′-3′) | Gene | Accession No. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tet(X3)-P | AAGATTTTCCAAATGGAGTGAAG | tet(X3) | MK134375.1 | This study |

| tet(X4)-P | TCGTGTGACATCATCT | tet(X4) | MK134376.1 | This study |

Standard curves and PCR conditions

The tet(X3) and tet(X4) genes were cloned into the pMD19-T vector separately, and then transferred into DH5α cells. Standard curves were established using real-time PCR on a QuantStudio™ 7 Flex Real-Time PCR System (ABI-Applied Biosystems Incorporated, Foster City, CA) using 10-fold serial dilutions of the recombinant plasmid DNA with original concentration of 47 ng/μL and 39.4 ng/μL for tet(X3) and tet(X4), respectively. Multiplex PCR reactions were performed in a total reaction volume of 20 μL, including 0.4 μL of each primer, 0.4 μL of probe, 0.4 μL of Passive Reference Dye (50×) (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China), 10 μL of 2× TansStart® Probe qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China), 1.0 μL of DNA template, and 7.4 μL of ddH2O. Each pair of primers and probes were optimized to a final concentration of 0.2 pM. Real-time PCR reaction conditions were as follows: a cycle of 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 55 °C for 30 s.

Specificity and sensitivity tests

To evaluate the specificity of the proposed method, DH5α strains containing tet(X), tet(X1), tet(X2), tet(X3) and tet(X4), respectively, were used to conduct the real-time PCR assay (Table 1). Genomic DNA extracted from bacteria, faeces and soil samples from different origin was then used to further validate the specificity and sensitivity of the method.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- AMR

Antimicrobial resistance

- XDR

Extensively drug resistant

- WHO

World Health Organization

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- MIC

Minimal inhibitory concentration

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- CT

Cycle threshold

- 16S rRNA

16S ribosomal Ribonucleic Acid

- MDR

Multi-drug resistant

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- MALDI-TOF

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-Time of Flight

Authors’ contributions

SW, ZS, and SD designed the study; YL performed the experiments; YL analyzed the data; SW and YL wrote the manuscript. And all authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant [2016YFD0501301, 2016YFD0501304 & 2016YFD0501305]. None of the funders were involved in designing and conducting of the study, analysis of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The data and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yiming Li, Email: liyiming@cau.edu.cn.

Zhangqi Shen, Email: szq@cau.edu.cn.

Shuangyang Ding, Email: dinghy@cau.edu.cn.

Shaolin Wang, Email: shaolinwang@outlook.com.

References

- 1.Rodríguez-Baño J, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez B, Machuca I, AJCmr P. Treatment of infections caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-, AmpC-, and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;31(2):e00079–e00017. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00079-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y-Y, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi L-X, Zhang R, Spencer J, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Partridge SR, Di Pilato V, Doi Y, Feldgarden M, Haft DH, Klimke W, et al. Proposal for assignment of allele numbers for mobile colistin resistance (mcr) genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(10):2625–2630. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He T, Wang R, Liu D, Walsh TR, Zhang R, Lv Y, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated high-level tigecycline resistance genes in animals and humans. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(9):1450–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Guiney DG, Jr, Hasegawa P, Davis CE. Expression in Escherichia coli of cryptic tetracycline resistance genes from Bacteroides R plasmids. Plasmid. 1984;11(3):248–252. doi: 10.1016/0147-619X(84)90031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bai L, Du P, Du Y, Sun H, Zhang P, Wan Y, et al. Detection of plasmid-mediated tigecycline-resistant gene tet (X4) in Escherichia coli from pork, Sichuan and Shandong provinces, China, February 2019. Euro Surveill. 2019;24(25):1900340. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.25.1900340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun C, Cui M, Zhang S, Wang H, Song L, Zhang C, Zhao Q, Liu D, Wang Y, JJEm S, et al. Plasmid-mediated tigecycline-resistant gene tet (X4) in Escherichia coli from food-producing animals, China, 2008–2018. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8(1):1524–1527. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1678367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun J, Chen C, Cui C-Y, Zhang Y, Liu X, Cui Z-H, et al. Plasmid-encoded tet (X) genes that confer high-level tigecycline resistance in Escherichia coli. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(9):1457–1464. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0496-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higuchi R, Fockler C, Dollinger G, Watson R. Kinetic PCR analysis: real-time monitoring of DNA amplification reactions. Nat Biotechnol. 1993;11(9):1026–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Subirats J, Royo E, Balcázar JL, Borrego CM. Real-time PCR assays for the detection and quantification of carbapenemase genes (Bla KPC, Bla NDM, and Bla OXA-48) in environmental samples. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2017;24(7):6710–6714. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-8426-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Q, Yang W, Wang S, Zheng W, Xiang-dang D, Jiang H, et al. Prevalence and Abundance of Florfenicol and Linezolid Resistance Genes in Soils Adjacent to Swine Feedlots. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32192. doi: 10.1038/srep32192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiwei B, Jian W, Xun P, Zhimin Q. Dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes and their potential removal by on-farm treatment processes in nine swine feedlots in Shandong Province, China. Chemosphere. 2017;167:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen C, Chen L, Zhang Y, Cui C-Y, Wu X-T, He Q, Liao X-P, Liu Y-H, Sun J. Detection of chromosome-mediated tet (X4)-carrying Aeromonas caviae in a sewage sample from a chicken farm. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(12):3628–3630. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen C, Cui C-Y, Zhang Y, He Q, Wu X-T, Li G, et al. Emergence of mobile tigecycline resistance mechanism in Escherichia coli strains from migratory birds in China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8(1):1219–1222. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1653795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji K, Xu Y, Sun J, Huang M, Xu J, Jiang C, et al. Harnessing efficient multiplex PCR methods to detect the expanding Tet(X) family of Tigecycline resistance genes. Virulence. 2020;11(1):49–56. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2019.1706913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui Z-H, Ni W-N, Tang T, He B, Zhong Z-X, Fang L-X, et al. Rapid Detection of Plasmid-Mediated High-Level Tigecycline Resistance in Escherichia Coli and Acinetobacter Spp. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020. 10.1093/jac/dkaa029. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Yulin F, Liu D, Song H, Liu Z, Jiang H, Wang Y. Development of a multiplex real-time PCR assay for rapid detection of Tigecycline resistance gene tet(X) variants from bacterial, faeces, and environmental samples. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64(4):e02292–e02219. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02292-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Law JW-F, Ab Mutalib N-S, Chan K-G, Lee L-HJ. Rapid methods for the detection of foodborne bacterial pathogens: principles, applications, advantages and limitations. Front Microbiol. 2015;5:770. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The data and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.