Abstract

In 2007, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) was approved for use in humans at a concentration of 1.5 mg/mL with absorbable collagen sponges as an alternative to autogenous bone grafts for alveolar ridge augmentation, defects associated with extraction sockets, and sinus augmentation. However, the use of supraphysiological doses and the insufficient retention of rhBMP-2, when delivered through collagen sponge, result in dose-dependent side effects related to off-label use. Demineralized dentin matrix (DDM), an osteoinducing bone substrate, has been used as an rhBMP-2 carrier since 1998. In addition, DDM has both microparticle and nanoparticle structures, which do not undergo remodeling, unlike bone. In vitro, DDM is a suitable carrier for BMP-2, with the continued release over 30 days at concentrations sufficient to stimulate osteogenic differentiation. In this review, we discuss the histological outcomes of DDM loaded with rhBMP-2 to highlight the biological functions of exogenous rhBMP-2 associated with the DDM carrier in clinical applications in implant dentistry.

Impact Statement

Demineralized dentin matrix (DDM) has been used as an recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein (rhBMP-2) carrier and osteo-inducing bone substrate to facilitate continued release and stimulate osteogenic differentiation. In this review, we discuss the histological outcomes of DDM loaded with rhBMP-2 in order to highlight the biological functions of exogenous rhBMP-2 associated with the DDM carrier in clinical applications in implant dentistry.

Keywords: bone morphogenetic protein, bone substitute, demineralized dentin matrix

Introduction

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are important growth factors (GFs) involved in enhancing the osteoblastic differentiation of stem cells and promoting bone formation. Among many types of BMPs, recombinant human BMP-2 (rhBMP-2) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2007 for use at a concentration of 1.5 mg/mL with absorbable collagen sponges (ACSs) in sinus and alveolar ridge augmentations for the defects associated with extraction sockets.1

However, this approved concentration is 106-fold higher than the concentration of naturally secreted osteogenic proteins in the human body.2,3 Thus, this high concentration can induce inflammatory side effects by increasing osteoclastic activity in a cancellous bone environment.4 In addition, the administration of rhBMP-2 during surgical procedures is complicated by its short biological half-life, localized action, and rapid clearance.5 Another possible explanation for the limited clinical effectiveness of rhBMP-2 is fast release from ACSs owing to its own mechanical instability and the homogenous loading method (i.e., dipping of ACSs into rhBMP-2), resulting in loss of ∼50% of the protein within the first 2.5 days and almost 100% of the protein after 14 days.6

To overcome these problems, various biomaterials have been investigated as carriers for rhBMP-2 in basic and clinical studies to achieve stable localized rhBMP-2 concentrations for a sufficient period.6–8 Recent efforts have been made to combine synergistic GFs and carrier molecules to lower the required rhBMP-2 dose, and the concentration of rhBMP-2 reached after its release.9,10 However, optimal rhBMP-2 carriers showing mechanical stability and enabling incorporation of the other GFs are still being developed.

Demineralized dentin matrix (DDM) has been shown to have osteoinduction capacity in several in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies.11–13 Moreover, DDM may be a potential carrier of rhBMP-2 because of its stable mechanical structure compared with ACSs and the unique properties of dentin.14–17 As a major component of teeth, dentin is an acid-insoluble, acellular, avascularized type I collagenous scaffold with nanoporous dentinal tubules containing minerals and noncollagenous proteins (NCPs), including GFs.18,19 Among the many human dentin matrix-derived GFs (HD-GFs), endogenous dentin BMPs (ED-BMPs), which are similar to bone matrix-derived BMPs, have been identified and purified, showing similar actions in vivo.20 The dentin matrix comprises four types of calcium phosphate (e.g., hydroxyapatite, β-tricalcium phosphate, amorphous calcium phosphate, and octacalcium phosphate) with low crystalline apatite, which possess higher solubility.21 This biodegradability of the dentin matrix in physiologic conditions presents enlarged microporous dentinal tubules and loosened surface interfibrillar space that facilitate the release of HD-GFs and ED-BMPs.21,22

In 2019, the release profile of rhBMP-2 incorporated with DDM (DDM/rhBMP-2) was postulated according to the type of incorporation method.22 After the release of adsorbed rhBMP-2, dentin degradation and release of ED-BMPs occur according to the principles of natural bone remodeling.22,23 Although few studies have been carried out, the potential applications of DDM as a potential carrier of rhBMP-2 can be evaluated based on available evidence.

Based on this background, the aims of this review were to provide information on histological differences between DDM/rhBMP-2 and DDM alone as an osteoinductive bone substitute and to gain insights into the relationships between rhBMP-2 and ED-BMPs with respect to the postulated release profile of DDM/rhBMP-2 based on histological reports.

Preparation of Demineralized Dentin Matrix as a Carrier for Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 (DDM/rhBMP-2)

Articles comparing DDM/rhBMP-2 with DDM as a control are summarized in Table 1. Among the articles, the first report from Ike and Urist, written in 1998, to apply rhBMP-2 to DDM was included in this review, although there is no histological figure.

Table 1.

Preparation of DDM and DDM/rhBMP-2

| Study/reference | DDM source | Subjects | Feature of carrier | Demineralization | rhBMP-2 dose/loading method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo study | |||||

| Ike 199814 | Human tooth root | Normal, athymic mice/hindquarter muscles | Dentin block (1.0–2.0 mm3, 0.5 g) | 0.6 N HCl (PDM) | 1, 2, and 5 μg rhBMP-2/70 mg DDM: NA (Genetic Institute, Boston, MA) |

| Miyaji 200216 | Rat tooth root | Rats/palatal connective tissue | Dentin block (1 × 1 × 0.3 mm) | 24% EDTA (NA) | 50 and 100 μg/mL rhBMP-2: soaking (Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical, Japan) |

| Murata 201217 | Human DDM | Rats/subcutaneous pocket back | Powder (0.4–0.8 mm) | 0.6 N HCl (CDM) | 5.0 μg BMP-2/70 mg DDM: soaking (Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical, Japan) |

| Um 201627 | Rabbit DDM | Rabbits/calvarium | Powder (300–800 μm) | 0.6 N HCl (PDM) | 50 μg rhBMP-2/300 mg DDM: freeze-drying (Cowelmedi, Busan, Korea) |

| Um 201828 | Rabbit DDM | Mice/thigh muscle | Powder (300–800 μm) | 0.6 N HCl (PDM) | 50 μg rhBMP-2/300 mg DDM: freeze-drying (Cowelmedi, Busan, Korea) |

| Rabbit DDM | Rabbits/calvarium | Powder (300–800 μm) | 0.6 N HCl (PDM) | 50 μg rhBMP-2/300 mg DDM: freeze-drying (Cowelmedi, Busan, Korea) | |

| Clinical Study | |||||

| Um 201729 | Human DDM | Humans/alveolar bone | Powder (300–800 μm) | 0.6 N HCl (PDM) | 0.2 mg/mL rhBMP-2: freeze-drying, (Cowelmedi, Busan, Korea) |

| Jung 201830 | Human DDM | Humans/alveolar bone | Powder (300–800 μm) | 0.6 N HCl (PDM) | 0.2 mg/mL rhBMP-2: freeze-drying (Cowelmedi, Busan, Korea) |

| Um 201931 | Human DDM | Humans/alveolar bone | Powder (300–800 μm) | 0.6 N HCl (PDM) | 0.2 mg/mL rhBMP-2: freeze-drying (Cowelmedi, Busan, Korea) |

CDM, completely demineralized dentin matrix; DDM, demineralized dentin matrix; DDM/rhBMP-2, DDM loaded with rhBMP-2; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; PDM, partially demineralized dentin matrix; NA, not available; rhBMP-2, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein.

DDM is produced by acid extraction of dentin through a process that removes the inorganic mineral component and leaves a type I collagen framework.24 Demineralization also exposes HD-GFs, including ED-BMPs, and improves the osteoinductivity of DDM.25 The degree of demineralization achieved when using 24% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid was not available.16 However, Murata showed complete demineralization using 0.6 N HCl,17 and other studies reported partial demineralization using 0.6 N HCl, with 10–30% minerals remaining.12,17

DDM/rhBMP-2 incorporation is achieved by two methods.22 First, for physical adsorption to the DDM surface, a simple approach in which the DDM scaffold is dipped into the protein solution and left to dry can be used when there is no specific affinity between the protein and carrier molecules. Alternatively, modified physical entrapment of the protein within nanoporous dentinal tubules can be achieved by freeze-drying. The incorporation method of rhBMP-2 on the dentin matrix was not depicted in a study using simple soaking of DDM with rhBMP-2 solution before implantation.14 Thus, the main disadvantage of this adsorption method is the rapid release of rhBMP-2.26 Three other studies used DDM dipped into the rhBMP-2 solution and freeze-dried as a single composite.27–29 In clinical studies,29–31 the rhBMP-2 concentration within DDM/rhBMP-2 was set at 0.2 mg/mL, which is lower than the FDA-approved concentration of 1.5 mg/mL1.

Histological Features of DDM and DDM/rhBMP-2

Four experimental studies14,16,17,28 have evaluated the biological activities of DDM/rhBMP-2 compared with DDM alone at extraskeletal sites. Two experimental studies were performed at skeletal sites,27,28 and one was performed at both sites.28 Among three clinical studies29–31 comparing DDM/rhBMP-2 with DDM alone, one study29 reported the histological features of the dentin matrix, and the other two studies30,31 reported the total amount of bone formation and remaining dentin matrix. Histological comparisons between these materials in experimental and clinical studies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Histological Features of DDM and DDM/rhBMP-2

| Study | Histological findings of DDM | Histological findings of DDM/rhBMP-2 | Don/Rec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo study | Soft tissue | 1 week | Neutrophilic and eosinophilic leukocytes17 | Osteoblast differentiation17 | H/R |

| Fibrous envelope28 | Resorption, enlarge dentinal tubule28 | Rab/M | |||

| 2 weeks | Hard tissue containing cells, lined by fibroblast-like cells. Slight resorption to newly formed hard tissue and dentin surface16 | R/R | |||

| Dense connective tissue17 | Giant cells on surface of DDM. Induced woven bone17 | H/R | |||

| Enlarged dentinal tubule28 | Dentin resorption, NB formation28 | Rab/M | |||

| 3 weeks | No NB formation14 | Rapidly resorbed DDM. Replacement by NB at rates proportional to the quantity of exogenous rhBMP-214 | H/M | ||

| No NB formation17 | Cartilage and active bone with trabecular and cement line17 | H/WR | |||

| 4 weeks | No NB formation16 | Bone formation and resorption16 | R/R | ||

| Bone formation on DDM surface17 | Matured bone with hematopoietic bone marrow17 | H/R | |||

| Calvarium | 2 weeks | Osteoconductive bone formation27 | Osteoinductive bone formation and remodeling27 | H/Rab | |

| 4 weeks | Direct bone formation28 | Bone formation, osteoclastic resorption, and dentin remodeling28 | Rab/Rab | ||

| Clinical study | Gum tissue | 3 months | No resorption but fibrous tissue29 | Autogenous | |

| 6 months | Resorption and cell infiltration29 | Autogenous | |||

| Bone tissue | 3 months | Bone formation31 | Bone bridge, resorption, and remodeling31 | Autogenous | |

| 4 months | Bone formation30 | Bone formation, resorption, and remodeling30 | Autogenous | ||

Don, donor; H, human; R, rat; Rab, rabbit; Rec, recipient; M, mouse; NB, new bone.

DDM and DDM/rhBMP-2 at extraskeletal sites

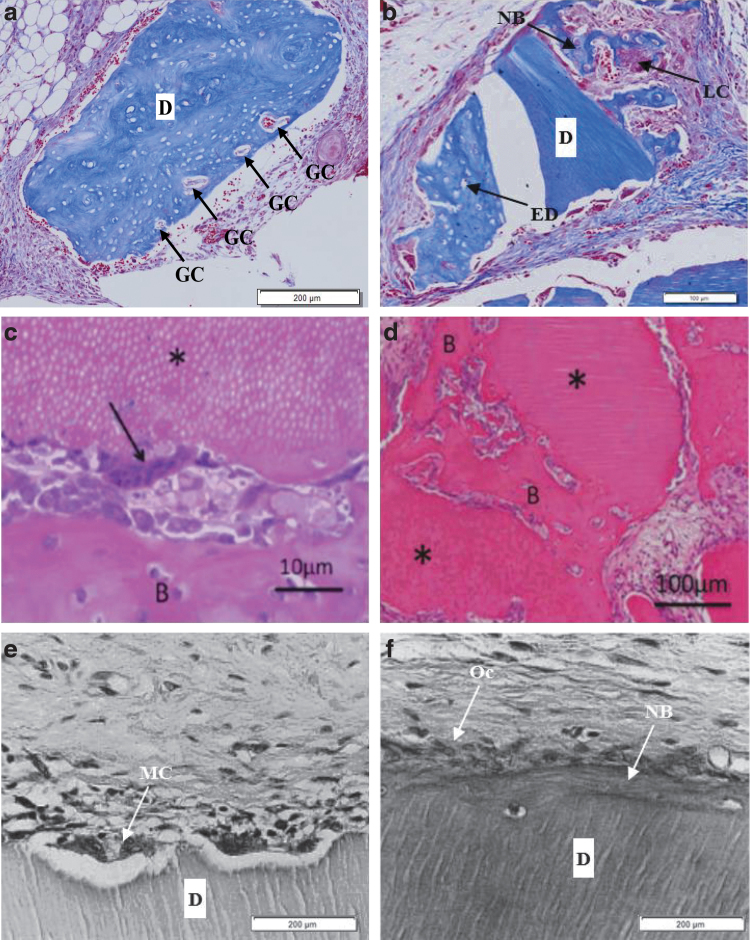

At 3–4 weeks, DDM was surrounded by dense fibrous capsules with abundant fibroblasts. In addition, DDM was lined by fibroblast-like cells without any new hard tissue formation16,17 (Fig. 1a, b). At 4 weeks, in another study,17 there was new bone formation on the surface of DDM lined by fibroblast-like cells (Fig. 1c), whereas the other DDM showed active bone formation with the embedding of osteocytes and lining with osteoblasts28 (Fig. 1d). This demonstrated the applications of DDM as a biocompatible and osteoinductive bone substitute.

FIG. 1.

Histological features of DDM alone implanted at an extraskeletal site. (a) Rat demineralized dentin block (size 1 × 1 × 0.3 mm) alone ( × 100) implanted into masticatory mucosa of the hard palate of Wistar rat at 4 weeks after surgery (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 200 μm).16 The dentin surface was lined by fibroblast-like cells without any new hard tissue formation. (b) Human DDM alone (*) implanted into rat subcutaneous tissues at 3 weeks after surgery (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 10 μm).17 Mesenchymal cells were observed on the DDM surface, and hard tissue formation was not observed. (c) Human DDM alone (*) implanted into the rat subcutaneous tissues at 4 weeks (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 50 μm).17 Induced bone (B) was deposited on the surface of DDM. (d) Rabbit DDM (D) alone implanted in dorsal subcutaneous tissue of mice at 4 weeks (Masson trichrome staining, scale bar = 100 μm), increased deposits of osteoids (O) and NB were observed on the surface of DDM (devoid during pathologic preparation) with blood vessel infiltration with transformed LCs for remodeling.28 D, DDM; DDM, demineralized dentin matrix; LC, lining cell; NB, new bone; O, osteoid.

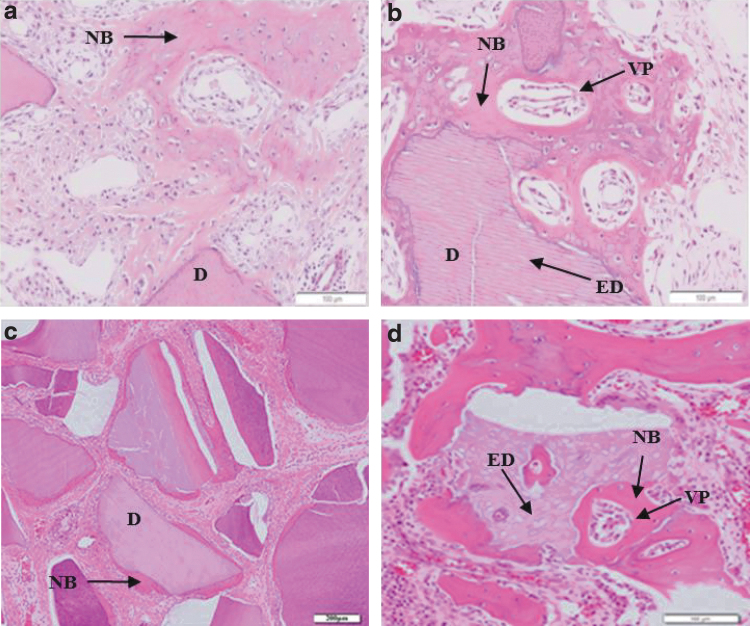

Figure 2 also shows the osteoinductive properties of DDM/rhBMP-2. At 1 week after implantation, DDM/rhBMP-2 was surrounded by dense fibrous capsules and showed enlarged dentinal tubules and resorption cavities28 (Fig. 2a). At 2 weeks, there was new bone formation with osteocyte embedding, lined by fibroblast-like cells. Slight resorption of the dentin surface and newly formed hard tissue were observed28 (Fig. 2b). There were multinuclear giant cells on the surface of DDM, and cuboid osteoblasts were found on induced woven bone, indicated as (B)17 (Fig. 2c). At 3 weeks, active bone formation was observed on the DDM surface17 (Fig. 2d), whereas at 4 weeks, multinucleated cells resembling osteoclasts with resorption lacunae were observed on the dentin surface16 (Fig. 2e). The resorbed dentin surface was filled with new hard tissue formation with a cement line and lined by osteoblast-like cells. This resorption lacuna was replaced with new bone at rates proportional to the quantity of rhBMP-216 (Fig. 2f). Strikingly, bone formation on the DDM surface occurred at the earlier stage of 2 weeks in the presence of DDM/rhBMP-2 compared with that in the presence of DDM alone, which showed bone formation at 4 weeks. Enlargement of dentinal tubules was observed within 2 weeks. Concomitantly, DDM surface resorption by osteoclast-like cells was observed from 1 to 4 weeks. After 3 weeks, there was active bone formation on the DDM surface and replacement of the resorption lacuna with newly formed bones. The total amount of bone formation was greater in the presence of DDM/rhBMP-2 than in the presence of DDM alone in dose-dependent and time-dependent studies.14,17

FIG. 2.

Histological features of DDM/rhBMP-2 implanted at an extraskeletal site. (a) Rabbit DDM/rhBMP-2 (0.2 mg/mL; Cowell BMP, Busan, Korea) implanted in the dorsal subcutaneous tissue of mice (Masson trichrome staining, scale bar = 200 μm) at 1 week after surgery. DDM (D) was surrounded by dense FCs enriched by fibroblast-like cells.28 There were enlarged dentinal tubules (ED) and osteoclastic resorption on the dentin surface on the other side. Multiple collagenolytic resorption (giant cells [GCs]) was observed on the surface of the DDM with active cellular infiltration. (b) At 2 weeks after surgery under the same conditions as in (a) (Masson trichrome staining, scale bar = 100 μm).28 Newly formed osteoids (NB) were deposited on the surface with highly proliferated and phenotypically transformed LCs. There were enlarged dentinal tubules (EDs) and osteoclastic resorption on the dentin surface. (c) Human DDM/rhBMP-2 (5.0 μg/mL; Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Japan) implanted into the rat subcutaneous tissues at 2 weeks after surgery (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 10 μm).17 Multinuclear GCs (arrow) were on surface of DDM (*). Cuboid osteoblasts were lining the surface of induced woven bone as indicated in (B). (d) At 3 weeks after surgery under the same conditions as in (c) (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 100 μm).17 Active bone formation (B) was observed on the DDM surface (*). (e) Rat demineralized dentin blocks (size 1 × 1 × 0.3 mm; × 100) treated with 50 μg/mL rhBMP-2 (Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Japan) implanted into the masticatory mucosa of the hard palate of Wistar rats at 4 weeks after surgery (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 200 μm).16 Multinucleated cells (MCs) resembling osteoclasts with resorption lacunae were observed on the dentin surface (D). (f) Similar conditions as (e), except that the concentration of rhBMP-2 was 100 μg/mL (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 200 μm).16 The resorbed dentin surface was filled with new hard tissue formation (NB) and lined by osteoblast-like cells (Ocs). DDM; DDM/rhBMP-2; ED, enlarged dentinal tubule; FC, fibrous capsule; GC, giant cell; MC, multinucleated cell; Oc, osteoblast-like cell.

Overall, in soft tissue, DDM showed encapsulation with dense fibrous tissue capsules containing abundant fibroblast-like cells within 3 weeks. At 4 weeks, new bone formation on the surface of DDM was observed in soft tissues, suggesting the release of ED-BMPs. However, DDM/rhBMP-2 showed enlarged dentinal tubules and osteoclastic resorption of the dentin surface and osteoinductive bone formation at the early stage of 1–2 weeks. These observations suggest that the additional rhBMP-2 plays a role in both osteoblastic bone formation and osteoclastic resorption of DDM concomitantly, which is replaced with newly formed bone. These dual activities of rhBMP-2 at an early stage may result in an increased bone formation capacity.

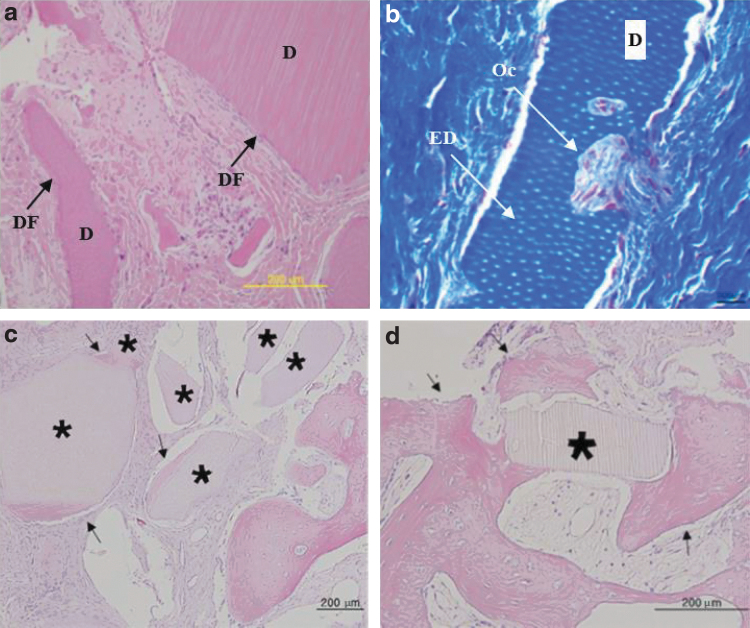

DDM and DDM/rhBMP-2 in rabbit calvarial defects

In the center of rabbit calvaria at 2 weeks, DDM (xenogenic; human DDM implanted into rabbits) alone showed osteoconductive bone migration from the defective margin with abundant osteocytes and blood vessels27 (Fig. 3a). On the other side, DDM/rhBMP-2 (xenogenic; human DDM implanted into rabbits) showed osteoinductive deposits of osteoids on all DDM surfaces, where abundant vascular proliferation and osteocyte embedding were evident during the remodeling process, surrounded by highly vascularized loose fibrous tissues27 (Fig. 3b).

FIG. 3.

Histological features of rabbit DDM and DDM/rhBMP-2 implanted in rabbit calvarial defects. (a) Rabbit DDM alone implanted in the center of rabbit calvarial defects (8 mm diameter) at 2 weeks after surgery (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 200 μm).27 NB migrated from the bone defect margin, which had abundant osteocytes and blood vessels. Fibroblasts around the DDM (D) were phenotypically transformed into osteoblast-like cells. (b) Rabbit DDM/rhBMP-2 (0.2 mg/mL; Cowell BMP, Busan, Korea) implanted under the same conditions as for (a) (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 100 μm).27 There were enlarged dentinal tubules (EDs) on the dentin surface. Osteoinductive deposits of osteoids was evident with the lining of osteoblast-like cells on the surfaces of the osteoids. There was abundant VP in the newly deposited osteoids (NB). (c) Rabbit DDM alone implanted in the center of rabbit calvarial defect (8 mm diameter) at 4 weeks after surgery (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 200 μm) showed a newly deposited osteoid seam around the particle surrounded by dense fibrous connective tissues with scanty vasculature.28 This osteoinductive bone formation on the surface may be induced by the ED-BMPs. (d) Rabbit DDM/rhBMP-2 (0.2 mg/mL; Cowell BMP, Busan, Korea) implanted under the same conditions as in (c) (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 100 μm).28 There were enlarged dentinal tubules (EDs) on the dentin surface. Active NB formation was observed around the particle with resorption of DDM surface. Resorbed surface and lacuna of DDM were replaced with newly formed bone (NB) with VP. ED-BMPs, endogenous dentin BMPs; VP, vascular proliferation.

At 4 weeks, DDM (allogenic) alone showed osteoinductive bone deposition on the dentin matrix surface, surrounded by dense fibrous connective tissue. Vascularized connective tissues were reduced, and there were no remarkable changes in the dentin matrix28 (Fig. 3c). In addition, DDM/rhBMP-2 (allogenic) showed new osteoid deposition on the DDM surface and resorbed lacuna with vessel invasion, where active remodeling occurred28 (Fig. 3d).

Overall, in rabbit calvarial defects, DDM alone showed biocompatibility and osteoconductive bone formation at 2 weeks, whereas DDM/rhBMP-2 showed osteoinductive bone formation infiltrated with vessels and embedded with osteocytes. At 4 weeks in the center of rabbit calvarial defects, DDM alone showed osteoinductive bone formation on the surface without any dentin resorption, whereas DDM/rhBMP-2 showed active bone formation and remodeling.

DDM and DDM/rhBMP-2 in human alveolar bone for socket preservation

In biopsy specimens from humans, DDM alone was obtained from gingival tissue at 3.5 months after the socket preservation procedure. This DDM was surrounded by dense fibrous connective tissues, which were in close contact with the particles, leaving no gaps. The fibrous capsule seemed to consist of inactive, flat fibroblast-like cells29 (Fig. 4a). In contrast, DDM/rhBMP-2 obtained from gingival tissue at 6 months after the socket preservation procedure was resorbed from the surface and internal matrix, which were infiltrated by activated cell layers29 (Fig. 4b).

FIG. 4.

Histological features of human DDM and DDM/rhBMP-2 implanted for socket preservation. (a) Biopsy specimens of human DDM alone in mandibles at 3.5 months after the socket preservation procedure (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 200 μm) under gingival tissue.29 DDM was surrounded by dense fibrous connective tissues (DF), which were in close contact with the particle, leaving no gaps. The FC seemed to consist of inactive flat fibroblast-like cells. Dentin matrix resorption was not observed. (b) Biopsy specimens of human DDM/rhBMP-2 (0.2 mg/mL; Cowell BMP, Busan, Korea) in the maxilla at 6 months after the socket preservation procedure (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 200 μm) under gingival tissue.29 Enlarged dentinal tubules (ED) were observed. Multiple activated cell layers encapsulated the dentin matrix surface. The resorption cavity was infiltrated with osteoclast-like cells (Ocs) that may facilitate the release of ED-BMPs present as matrix- and hydroxyapatite-binding proteins. (c) Trephine biopsy specimens of human DDM alone in the mandible at 3 months after the socket preservation procedure (hematoxylin–eosin staining, scale bar = 200 μm).31 Bone formation (arrows) around the DDM particles (*) surrounded by dense fibrous connective tissue. (d) Trephine biopsy specimens of human DDM DDM/rhBMP-2 (0.2 mg/mL; Cowell BMP, Busan, Korea) in the mandible at 3 months after the socket preservation procedure (hematoxylin–eosin stain, scale bar = 200 μm).31 Active bone formation (arrows) was observed with embedding of osteocytes and lining of osteoblasts around the DDM particles (*), which were surrounded by highly vascularized alveolar tissue. DF, dense fibrous connective tissues.

Three months after the socket preservation procedure in the mandible, human DDM showed osteoinductive and osteoconductive bone formation around the DDM particles and was surrounded by dense fibrous connective tissue. There was no dentin resorption31 (Fig. 4c). For DDM/rhBMP-2, active bone formation was observed with the embedding of osteocytes and the lining of osteoblasts around the DDM particles. In addition, fewer DDM particles remained in the highly vascularized alveolar tissue31 (Fig. 4d).

In clinical studies, DDM showed osteoinductive bone formation on the DDM surface, but no changes in dentin particles lining the soft tissues. Compared with DDM alone, DDM/rhBMP-2 showed faster osteoinductive bone formation and resorption of the dentin matrix, which was replaced with newly formed bone. Consequently, less DDM remained in human studies of DDM/rhBMP-2. Therefore, the results were consistent with observations of DDM/rhBMP-2 in soft tissues.

Major Observations

The goal of this review was to assess the bone formation capacity of DDM/rhBMP-2 compared with DDM alone based on histological findings from in vivo and clinical studies. In addition, we aimed to determine the relationship between rhBMP-2 and ED-BMPs with a focus on the unique properties of DDM versus other rhBMP-2 carriers. Based on histological review, the amount of bone formation with DDM/rhBMP-2 was greater than that with DDM alone. At the same time, DDM/rhBMP-2 had time- and dose-dependent effects, similar to other carriers. Thus, these findings implied that rhBMP-2, incorporated into DDM, may initiate both osteoinductive bone formation and osteoclastic resorption of the dentin matrix simultaneously. Through this osteoclastic resorption, leading to enlarge dentinal tubules, ED-BMPs could be released earlier than DDM alone. Release of ED-BMPs, existing as matrix- and mineral-binding proteins, could then initiate osteoblastic bone formation to facilitate remodeling.

Histological observations

The major histological characteristics of DDM/rhBMP-2 observed in the soft tissues were as follows: (1) early osteoblastic bone formation on the surface of DDM, (2) early osteoclastic resorption of dentin matrix or enlargement of dentinal tubules, and (3) replacement of resorption lacuna in dentin with new bone, as demonstrated by the formation of a cement line. Of note, in rabbit calvarial defects, DDM/rhBMP-2 showed more osteoinductive bone formation and abundant bone remodeling than DDM alone at the early stages of implantation. At later stages, the total amount of bone formation and remodeling was also greater for DDM/rhBMP-2 than for DDM alone. The histological differences between DDM/rhBMP-2 and DDM alone in rabbit calvarial defects were similar to those in soft tissue based on histological reports. In addition, in clinical studies, the bone formation capacity was increased by DDM/rhBMP-2, potentially resulting from the direct bone formation from the release of incorporated rhBMP-2 and newly formed bone deposition in the resorption lacuna of the dentin matrix. As a result, total bone formation and maturation were increased, whereas residual DDM decreased.31

Dose and release profile of rhBMP-2

Ike and Urist and Murata et al. reported that the amount of bone formation or bone remodeling was increased in proportion to the dose and time of rhBMP-2 administration.14,17 In clinical studies, a low dose of rhBMP-2 (0.2 mg/mL) was used; this dose was much lower than that used in most other studies,32–34 although the results were not inferior to those of conventional supraphysiological dosages.29 Therefore, the use of DDM/rhBMP-2 could reduce the threshold therapeutic dose of rhBMP-2 through the unique properties of DDM, which contains NCPs.35 Among many NCPs pre-embedded in the dentin inorganic mineral phase,15,36,37 HD-GFs, including transforming GF β, BMP-2, fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived GF, BMP-7, and BMP-4, have been extensively studied.19 BMP-2, BMP-7, and BMP-4 are present in dentin as ED-BMPs.

In a study of the release of endogenous BMP-7 from DDM (ED-BMP-7), Pietrzak et al.38 proposed a two-compartment model: early release of BMP-7 from the loose compartment and storage of BMP-7 in the tight compartment, resulting in long-term retention. According to their proposal, Um et al.22 also proposed a three-compartment model for DDM. First, early release of physically adsorbed rhBMP-2 occurred from the loosened interfibrillar space pores, whereas modified physically entrapped rhBMP-2 present in the deep dentinal tubules was released during the middle stage. Finally, ED-BMPs were released after degradation of the dentin matrix, modulated by various GFs within the dentin inorganic mineral phase.15,36,37 Analysis of the released kinetics and osteoinductive bone formation of DDM/rhBMP-2 have shown that rhBMP-2 is released at higher concentrations from days 1 to 30 compared with conventional rhBMP-2 carriers.15

Osteoclast activation with rhBMP-2

The main physiological function of osteoclasts in vivo is the resorption of bone matrix, which precedes the formation of new bone in the remodeling cascade. Osteoclastic resorption of DDM was enhanced by the addition of rhBMP-2; this is a distinct histological feature that has not been reported in other studies. This feature could be explained by the observation that dentin and bone are similar in chemical composition and structural organization, both showing collagen and mineral crystal deposition at the micro- and nanometer levels. Moreover, dentin has an absolute number of NCPs, including dentin sialoprotein, osteopontin, dentin matrix protein-1, and matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein,18,19 which are thought to influence cell behavior.39 For example, osteocytic proteins, which are expressed in bone but not in dentin, may suppress osteoclast formation during the bone remodeling process.40,41 As a result, quantification of osteoclastic resorption behaviors revealed 11-fold higher resorption on dentin compared with the bone.42 In contrast, some studies of osteoclast-like cell lines and osteoclasts generated from bone marrow have demonstrated topography-dependent higher resorption on rougher surfaces of the underlying substrate.43 Thus, if the surface topography of the underlying substrate has the potential to directly guide the resorption behavior of osteoclasts (as reflected by the size and number of resorption lacunae and the resorbed area), the enlarged dentinal tubules and the loosened interfibrillar space pore of the dentin after DDM generation may promote osteoclastic resorption influenced by rhBMP-2.22,43

This osteoclast-mediated release of ED-BMPs is a type of dual delivery system.44 After the release of adsorbed rhBMP-2, dentin degradation and the release of ED-BMPs partially follow the principles of natural bone remodeling proposed by Howard et al. as a local “coupling factor” pathway linking bone resorption to subsequent bone formation.45 Accordingly, the synergistic effects of rhBMP-2 and ED-BMPs may be related to the sequential or dual delivery pattern of DDM; rhBMP-2 released at an early stage may directly32,33 activate osteoclastic resorption of dentin matrix, followed by the release of ED-BMPs earlier and easier.15,22 In such a time sequence release pattern, the dose of the administered rhBMP-2 and the concentration of the released rhBMP-2 are important parameters to lower the necessary rhBMP-2 dose and control its release.

In clinical studies with 0.2 mg/mL rhBMP-2 DDM/rhBMP-2, which is much lower than the conventional supraphysiological dosage described in previous reports,1 the results showed almost similar osteoinductive bone formation.14,17,29–34 However, it was unclear why DDM favored osteoclast adhesion and resorption after the addition of rhBMP-2. In addition, the most physiological concentration of rhBMP-2 in terms of both direct osteoinduction activity and stimulation of ED-BMP release by osteoclastic resorption has still not been determined.

Summary

Within the limits of this review, which was conducted using a small number of studies, enhanced resorption of dentin through the addition of rhBMP-2 was detected in both in vivo and clinical studies. Through this review, we observed promoted osteoblastic differentiation of the surrounding mesenchymal stem cells and enhanced osteoinductive bone formation at an early stage through histological analyses. The dose of release profile of rhBMP-2 presented itself as dual or sequential release effects with ED-BMPs. Finally, this review led to the understanding of osteoclast activation with rhBMP-2 by increased resorption of dentin matrix. These observations suggest that DDM could be a promising candidate for rhBMP-2 carrier and that the most suitable dose of rhBMP-2 with DDM should be further optimized and investigated to facilitate the development of more clinically available delivery technologies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yumi Kim for assistance with this study and Prof. Jeong Keun Lee and Prof. Jong Ho Lee for English language assistance.

Authors' Contributions

J.K.K., Y.K.K., B.K.L., D.H.L., and I.W.U. researched data for the article. All authors made substantial contributions to the discussion of content and reviewed and edited the article before submission. J.K.K. and I.W.U. wrote the article. All authors read and approved the final article.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by grants from the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (grant/award no. HI15C1535).

References

- 1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness data [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2007 Mar 9. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf5/P050053b.pdf (accessed December30, 2018)

- 2. Gamradt S.C., and Lieberman J.R.. Genetic modification of stem cells to enhance bone repair. Ann Biomed Eng 32, 136, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. El Bialy I., Jiskoot W., and Reza Nejadnik M.. Formulation, delivery and stability of bone morphogenetic proteins for effective bone regeneration. Pharm Res 34, 1152, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burkus J.K., Sandhu H.S., and Gornet M.F.. Influence of rhBMP-2 on the healing patterns associated with allograft interbody constructs in comparison with autograft. Spine 31, 775, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ruhé P.Q., Boerman O.C., Russel F.G.M., Mikos A.G., Spauwen P.H.M., and Jansen J.A.. In vivo release of rhBMP-2 loaded porous calcium phosphate cement pretreated with albumin. J Mater Sci Mater Med 17, 919, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seeherman H., Wozney J., and Li R.. Bone morphogenetic protein delivery systems. Spine 27, S16, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wozney J.M. Overview of bone morphogenetic proteins. Spine 27, S2, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kempen D.H.R., Lu L., Hefferan T.E., et al. Retention of in vitro and in vivo BMP-2 bioactivities in sustained delivery vehicles for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 29, 3245, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Issa J.P., Bentley M.V., Iyomasa M.M., Sebald W., and De Albuquerque R.F.. Sustained release carriers used to delivery bone morphogenetic proteins in the bone healing process. Anat Histol Embryol 37, 181, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cao L., Wang J., Hou J., Xing W., and Liu C.. Vascularization and bone regeneration in a critical sized defect using 2-N,6-O-sulfated chitosan nanoparticles incorporating BMP-2. Biomaterials 35, 684, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Urist M.R., Dowell T.A., Hay P.H., and Strates B.S.. Inductive substrates for bone formation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 59, 59, 1968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim K.W. Bone induction by demineralized dentin matrix in nude mouse muscles. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg 36, 50, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pang K.M., Um I.W., Kim Y.K., Woo J.M., Kim S.M., and Lee J.H.. Autogenous demineralized dentin matrix from extracted tooth for the augmentation of alveolar bone defect: a prospective randomized clinical trial in comparison with anorganic bovine bone. Clin Oral Implants Res 28, 809, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ike M., and Urist M.R.. Recycled dentin root matrix for a carrier of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein. J Oral Implantol 24, 124, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim Y.K., Um I.W., An H.J., Kim K.W., Hong K.S., and Murata M.. Effects of demineralized dentin matrix used as an rhBMP-2 carrier for bone regeneration. J Hard Tissue Biol 23, 415, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miyaji H., Sugaya T., Miyamoto T., Kato K., and Kato H.. Hard tissue formation on dentin surfaces applied with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in the connective tissue of the palate. J Periodontal Res 37, 204, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murata M., Sato D., Hino J., et al. Acid-insoluble human dentin as carrier material for recombinant human BMP-2. J Biomed Mater Res A 100, 571, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wan C., Yuan G., Luo D., et al. The dentin sialoprotein (DSP) domain regulates dental mesenchymal cell differentiation through a novel surface receptor. Sci Rep 6, 29666, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Avery S.J., Sadaghiani L., Sloan A.J., and Waddington R.J.. Analysing the bioactive makeup of demineralised dentine matrix on bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for enhanced bone repair. Eur Cell Mater 34, 1, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bessho K., Tanaka N., Matsumoto J., Tagawa T., and Murata M.. Human dentin-matrix-derived bone morphogenetic protein. J Dent Res 70, 171, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim Y.K., Kim S.G., Yun P.Y., et al. Autogenous teeth used for bone grafting: a comparison with traditional grafting materials. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 117, e39, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Um I.W., Ku J.K., Lee B.K., Yun P.Y., Lee J.K., and Nam J.H.. Postulated release profile of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) from demineralized dentin matrix. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 45, 123, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Q., Zhang Y., Li B., and Chen L.. Controlled dual delivery of low doses of BMP-2 and VEGF in a silk fibroin–nanohydroxyapatite scaffold for vascularized bone regeneration. J Mater Chem B 5, 6963, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Um I.W., Kim Y.K., and Mitsugi M.. Demineralized dentin matrix scaffolds for alveolar bone engineering. J Indian Prosthodont Soc 17, 120, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bakhshalian N., Nowzari H., Ahn K.M., and Arjmandi B.H.. Demineralized dentin matrix and bone graft: a review of literature. J West Soc Periodontol Periodontal Abstr 62, 35, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luginbuehl V., Meinel L., Merkle H.P., and Gander B.. Localized delivery of growth factors for bone repair. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 58, 197, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Um I.W., Hwang S.H., Kim Y.K., et al. Demineralized dentin matrix combined with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in rabbit calvarial defects. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 42, 90, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Um I.W., Kim Y.K., Jun S.H., Kim M.Y., and Cui N.. Demineralized dentin matrix as a carrier of recombinant human bone morphogenetic proteins: in vivo study. J Hard Tissue Biol 27, 219, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Um I.W., Jun S.H., Yun P.Y., and Kim Y.K.. Histological comparison of autogenous and allogenic demineralized dentin matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 for alveolar bone repair: a preliminary report. J Hard Tissue Biol 26, 417, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jung G.U., Jeon T.H., Kang M.H., et al. Volumetric, radiographic, and histologic analyses of demineralized dentin matrix combined with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 for ridge preservation: a prospective randomized controlled trial in comparison with xenograft. Appl Sci 8, 1288, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Um I.W., Kim Y.K., Park J.C., and Lee J.H.. Clinical application of autogenous demineralized dentin matrix loaded with recombinant human bone morphogenetic-2 for socket preservation: a case series. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 21, 4, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patel Z.S., Young S., Tabata Y., Jansen J.A., Wong M.E.K., and Mikos A.G.. Dual delivery of an angiogenic and an osteogenic growth factor for bone regeneration in a critical size defect model. Bone 43, 931, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lin C.Y., Chang Y.H., Kao C.Y., et al. Augmented healing of critical-size calvarial defects by baculovirus-engineered MSCs that persistently express growth factors. Biomaterials 33, 3682, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Patterson J., Siew R., Herring S.W., Lin A.S., Guldberg R., and Stayton P.S.. Hyaluronic acid hydrogels with controlled degradation properties for oriented bone regeneration. Biomaterials 31, 6772, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. James A.W., LaChaud G., Shen J., et al. A review of the clinical side effects of bone morphogenetic protein-2. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 22, 284, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kisiel M., Klar A.S., Ventura M., et al. Complexation and sequestration of BMP-2 from an ECM mimetic hyaluronan gel for improved bone formation. PLoS One 8, e78551, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reddi A.H. Morphogenetic messages are in the extracellular matrix: biotechnology from bench to bedside. Biochem Soc Trans 28, 345, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pietrzak W.S., Dow M., Gomez J., Soulvie M., and Tsiagalis G.. The in vitro elution of BMP-7 from demineralized bone matrix. Cell Tissue Bank 13, 653, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Azari A., Schoenmaker T., de Souza Faloni A.P., Everts V., and de Vries T.J.. Jaw and long bone marrow derived osteoclasts differ in shape and their response to bone and dentin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 409, 205, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Verborgt O., Gibson G.J., and Schaffler M.B.. Loss of osteocyte integrity in association with microdamage and bone remodeling after fatigue in vivo. J Bone Miner Res 15, 60, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rumpler M., Würger T., Roschger P., et al. Microcracks and osteoclast resorption activity in vitro. Calcif Tissue Int 90, 230, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rumpler M., Wurger T., Roschger P., et al. Osteoclasts on bone and dentin in vitro: mechanism of trail formation and comparison of resorption behavior. Calcif Tissue Int 93, 526, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Matsunaga T., Inoue H., Kojo T., et al. Increase in the potential of osteoblasts to support bone resorption by osteoclasts in vitro in response to roughness of bone surface. Calcif Tissue Int 65, 454, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hu X., Yang P., He J., et al. In vivo self-assembly induced retention of gold nanoparticles for enhanced photothermal tumor treatment. J Mater Chem B 5, 5931, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Howard G.A., Bottemiller B.L., Turner R.T., Rader J.I., and Baylink D.J.. Parathyroid hormone stimulates bone formation and resorption in organ culture: evidence for a coupling mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78, 3204, 1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]