Abstract

Background

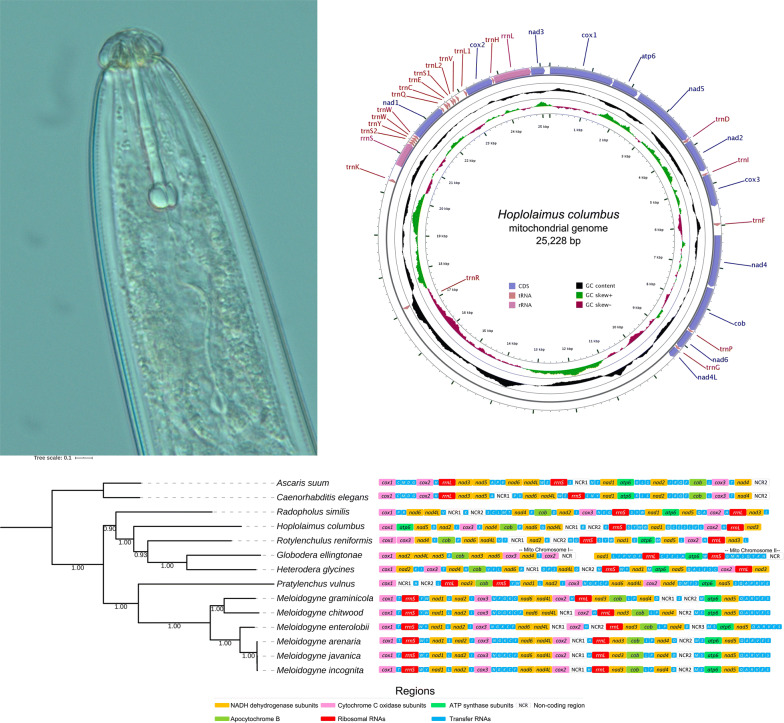

The plant-parasitic nematode Hoplolaimus columbus is a pathogen that uses a wide range of hosts and causes substantial yield loss in agricultural fields in North America. This study describes, for the first time, the complete mitochondrial genome of H. columbus from South Carolina, USA.

Methods

The mitogenome of H. columbus was assembled from Illumina 300 bp pair-end reads. It was annotated and compared to other published mitogenomes of plant-parasitic nematodes in the superfamily Tylenchoidea. The phylogenetic relationships between H. columbus and other 6 genera of plant-parasitic nematodes were examined using protein-coding genes (PCGs).

Results

The mitogenome of H. columbus is a circular AT-rich DNA molecule 25,228 bp in length. The annotation result comprises 12 PCGs, 2 ribosomal RNA genes, and 19 transfer RNA genes. No atp8 gene was found in the mitogenome of H. columbus but long non-coding regions were observed in agreement to that reported for other plant-parasitic nematodes. The mitogenomic phylogeny of plant-parasitic nematodes in the superfamily Tylenchoidea agreed with previous molecular phylogenies. Mitochondrial gene synteny in H. columbus was unique but similar to that reported for other closely related species.

Conclusions

The mitogenome of H. columbus is unique within the superfamily Tylenchoidea but exhibits similarities in both gene content and synteny to other closely related nematodes. Among others, this new resource will facilitate population genomic studies in lance nematodes from North America and beyond.

Keywords: Hoplolaimus, Lance nematode, Ecdysozoa, Mitochondrial genome, Phylogeny, de novo assembly

Background

In the phylum Nematoda, plant-parasitic species can be distinguished from animal parasites as well as non-parasitic relatives because their mouthparts and stylet are well developed allowing them to penetrate sturdy plant cell walls while digging and feeding [1, 2]. A number of plant-parasitic nematodes are currently recognized as major pathogens of agricultural crops worldwide, which leads to more than 150 billion USD losses annually in the USA [3]. In a recent USA survey of agricultural pathogens, six main genera of plant-parasitic nematodes were recognized as serious crop threats [1]: cyst nematodes (Heterodera spp.); lance nematodes (Hoplolaimus spp.); root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.); lesion nematodes (Pratylenchus spp.); reniform nematodes (Rotylenchulus spp.); and dagger nematodes (Xiphinema spp.). Moreover, some of the above pathogens, like lance nematodes, can damage horticultural fields, golf courses, and turfgrasses. These plant-parasitic nematodes can also cause serious indirect environmental problems by favoring chemical overuse during nematode management [4].

Lance nematodes are all species of migratory ecto-endo parasites with a distinct cephalic region and a massive well-developed stylet [4]. According to the current taxonomical view that relies on a combination of molecular and morphological characters, lance nematodes belong to the class Chromadorea, infraorder Tylenchomorpha [2, 4–6]. They exhibit a wide range of hosts, including, among others, turf grasses, cereals, soybean, corn, cotton, sugar cane, and some trees [1, 4, 7]. They live in soil, feed on plant roots, move inside or around plant tissue, and destroy cortex cells, that can result in root necrotic lesions [8]. Hoplolaimus columbus, also known as the ‘Columbia lance nematode’, is considered among the most economically important species in the world [1]. This nematode was described as a new species from samples collected in Columbia, South Carolina, USA. Later, the same species was reported in the states of North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana [8–10]. In the field, H. columbus is parasitic on cotton and soybean, on which pathogenicity has been demonstrated; production losses for cotton are typically 10–25%, and losses for soybean can be as high as 70% in the southeastern USA [11–14]. Although H. columbus has been found in some Asian countries [2], there are no reports yet of crop damage in the region. Hoplolaimus columbus belongs to the subgenus Basirolaimus together with 17 other nematode species [2]. Species in the subgenus Basirolaimus have been reported in Asian countries, including China, India and Japan [2]. Nonetheless, the only species in the subgenus Basirolaimus so far recognized as a major agricultural pathogen is H. columbus (i.e. in the USA) [2, 15, 16]. Considering its wide distribution and damage to crops, a better genomic understanding of H. columbus would prove helpful to understand its population genetic structure and effects, or the lack thereof, on commercially relevant crops.

Morphological characteristics alone have limited function to distinguish among closely related species in the genus Hoplolaimus given the remarkable similarity of internal and external organs and body parts among closely related species [5, 7]. Molecular markers have been shown to be useful for species identification and for understanding phylogenetic relationships and population genetics in different species of lance nematodes [5, 15–17]. Although previous work has provided valuable insights for nematode phylogeny [18–21], it has been noticed that short nuclear and/or mitochondrial gene markers are sometimes uninformative for revealing fine to moderate population genetic structure within a species [22]. This shortcoming can be addressed by developing genomic resources in this relevant group of lance nematodes. Although the genomes of a number of plant-parasitic nematodes have been sequenced and analyzed before [23–28], no genomic resources exist for lance nematodes, yet.

In this study, we de novo sequenced and assembled the complete mitochondrial genome of the Columbia lance nematode H. columbus. Other than annotating and providing a detailed description of the mitochondrial chromosome in this crop pathogen, we used protein-coding genes to explore phylogenetic relationships among plant-parasitic nematodes belonging to the class Chromadorea, superfamily Tylenchoidea.

Methods

Collection of specimens, DNA extraction and whole-genome amplification

Soil samples containing specimens of H. columbus were collected from the Edisto Research Center in Blackville, South Carolina (33°21’56.2”N, 81°19’46.9”W) and transported to Clemson University for further study. In the laboratory, nematodes were first extracted from soil samples using the sugar centrifugal flotation method [29]. A few fixed specimens were then identified using diagnostic key characters under an optical microscope [30]. Next, live nematodes (n = 9) were submerged into distilled water, starved for two weeks, and placed in a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution (Aaron Industry, Clinton, SC, USA) for 5 min before washing them in distilled water three times to eliminate potential microorganisms inhabiting their surface. Then, the same nematodes were placed separately in DNA Away solution (Molecular BioProducts Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) to eliminate potential DNA and DNase contamination and washed three times using PCR-grade water. Total DNA from each H. columbus specimen was extracted using a Sigma-Aldrich extract-N-Amp kit (XNAT2) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The whole genome size of H. columbus was estimated to be ~300 million bp using flow cytometry [31, 32]. Whole-genome amplification (WGA) of each individual nematode was then performed using an Illustra Ready-To-Go GenomiPhi V3 DNA amplification kit (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Three WGA replicates per nematode were performed, and the one with the highest DNA concentration tested using a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was selected for the next generation sequencing library preparation.

Library preparation and whole genome shotgun sequencing

The Nextera XT kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for library preparation using the manufacturer’s instructions. Library concentration and fragment size distribution after library preparation were determined using a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), respectively. Sequencing was conducted in an Illumina MiSeq with the v3 chemistry kit. A total of ~56 million reads (paired-end 300 bp) were generated and 98.11% of these reads were of high-quality. Approximately 13 Gb of sequence data had a quality score (Q-score) > 30.

Mitochondrial genome assembly and annotation

Two assembly methods were employed to reconstruct the mitochondrial genome of H. columbus. The first method employed the program NOVOPlasty 2.7.2 [33]. Reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic-0.36 [34] and assembled in NOVOPlasty using the following options: K-mer = 31; insert range = 1.6; and insert range strict = 1.2. A partial cox1 gene sequence belonging to H. columbus available on GenBank (KP864628) was used as a ‘seed’ during the assembly. A total of 110,852 reads were used for the final assembly that generated a circular DNA molecule with an average coverage of 1,476x. The second method used the programs MIRA and MITObim (mitochondrial baiting and iterative mapping) [35, 36]. The parameter settings for mitochondrial genome assembly using this second strategy were: NW:mrnl = 0; AS:nop = 1; SOLEXA_SETTINGS; CO:msr = no. After 15 iterations, MITObim assembled the mitochondrial genome of H. columbus. Mitochondrial genome chromosomes assembled using the two methods above were identical to each other.

After mitochondrial genome assembly, protein-coding genes (PCGs) and non-coding regions were predicted using the invertebrate mitochondrial code (genetic code 5) on the MITOS web server (http://mitos.bioinf.uni-leipzig.de/index.py) [37]. Annotation curation and start + stop codon corrections were conducted using the ExPASy translate tool (https://web.expasy.org/translate/) [38]. Secondary structures of tRNA genes were predicted using MiTFi [39] as implemented in MITOS and depicted using the web server FORNA (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/forna/) [40]. For the rrnS and rrnL genes, locations were first detected using MiTFi. Then, the entire sequence of each rRNA gene was predicted using NCBI BLAST comparisons with other nematode rrnS and rrnL sequences available in GenBank. Codon usage of the different PCGs was examined using Sequence Manipulation Suite (SMS) (http://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/index.html) [41]. The entire mitochondrial genome was depicted using CGView Server (http://stothard.afns.ualberta.ca/cgview_server/) [42].

Two relatively long non-coding regions found in the mitochondrial genome of H. columbus were analyzed in detail. Microsatellite sequences in these regions were detected using Microsatellite Repeats Finder (http://insilico.ehu.es/mini_tools/microsatellites/) [43], tandem repeats were detected using Tandem Repeats Finder 2016 v4.09 (https://tandem.bu.edu/trf/ trf.basic.submit.html) [44], and putative hairpin structures were predicted and visualized in the RNAFold webserver (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at//cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi) [45].

Mitophylogenomics in the superfamily Tylenchoidea

The phylogenetic analysis included full mitochondrial genomes belonging to a total of 14 nematode species in the class Chromadorea, of which 12 were plant-parasitic nematodes in the superfamily Tylenchoidea (Table 1). Caenorhabditis elegans (non-parasitic) and Ascaris suum (animal-parasitic) were used as outgroup terminals in our phylogenetic analysis. Each of a total of 12 PCGs (see results) was first aligned using MAFFT version 7 [46] and output files converted into Phylip format using the web server Phylogeny.fr [47, 48]. Then, poorly aligned positions in each of the 12 PCG sequence alignments were trimmed using BMGE (block mapping and gathering with entropy) [49]. SequenceMatrix [50] was used to concatenate all 12 PCG alignments in the following order: atp6-cox1-cox2-cox3-cytb-nad1-nad2-nad3-nad4-nad4L-nad5-nad6. The GTR + G nucleotide substitution model (Additional file 1: Table S1) selected using SMS (smart model selection) (http://www.atgc-montpellier.fr/sms/) [51] was used for maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis conducted on the web server IQ-Tree (http://www.iqtree.org/) [52] with the default settings but enforcing the GTR + G model of nucleotide substitution. A total of 100 bootstrap replicates were employed to explore support for each node in the resulting phylogenetic tree that was depicted using the web server iTOL (Interactive Tree of Life) (https://itol.embl.de/) [53].

Table 1.

Species used for phylogenetic analyses and protein-coding gene order survey in this study

| Species | GenBank ID | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| Ascaris suum | HQ704901.1 | 14,311 |

| Caenorhabditis elegans | NC_001328.1 | 13,794 |

| Globodera ellingtonae (I) | KU726971.1 | 17,757 |

| Globodera ellingtonae (II) | KU726972.1 | 14,365 |

| Heterodera glycines | HM640930.1 | 14,915a |

| Hoplolaimus columbus | MH657221 | 25,228 |

| Meloidogyne arenaria | NC_026554.1 | 17,580 |

| Meloidogyne chitwoodi | KJ476150.1 | 18,201 |

| Meloidogyne enterolobii | KP202351.1 | 17,053 |

| Meloidogyne graminicola | KJ139963.1 | 19,589 |

| Meloidogyne incognita | KJ476151.1 | 17,662 |

| Meloidogyne javanica | NC_026556.1 | 18,291 |

| Radopholus similis | FN313571.1 | 16,791 |

| Rotylenchulus reniformis | CM003310.1 | 24,572 |

| Pratylenchus vulnus | NC_020434.1 | 21,656 |

aIncomplete genome

Results and discussion

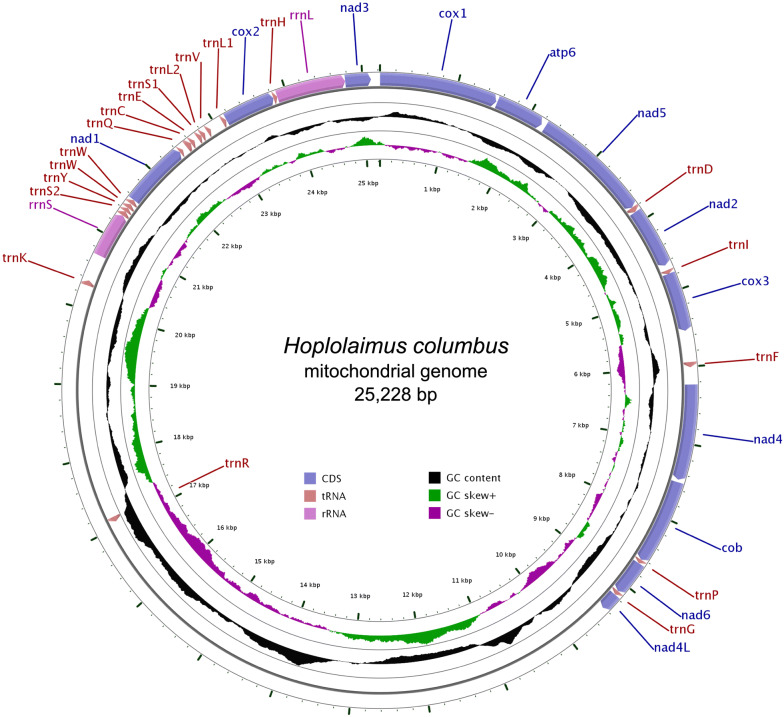

The complete mitogenome of H. columbus was de novo assembled into a closed-circular DNA molecule of 25,228 bp in length (GenBank: MH657221; Fig. 1). The nucleotide composition of the entire mitochondrial genome was A = 28.46% (n = 7179 bp), T = 46.12% (n = 11,634 bp), C = 8.45% (n = 2132 bp), and G = 16.97% (n = 4281 bp). We also observed one R (position 3768, purine, A or G) and one Y (position 10529, pyrimidine, C or T). The mitogenome was strongly biased towards A + T (74.57%). The GC skew ((G - C)/(G + C)) and AT skew ((A - T)/(A + T)) values were 0.3351 and -0.2369, respectively. The mitogenome of H. columbus comprises 12 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 19 transfer RNA genes, 2 ribosomal RNA genes, and 2 large non-coding regions. The atp8 gene was missing in the assembled mitogenome in agreement to that reported for other plant-parasitic nematodes [25–28] (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Circular genome map of Hoplolaimus columbus mitochondrial DNA. The map is annotated and depicts 12 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 2 ribosomal RNA genes (rrnS (12S ribosomal RNA) and rrnL (16S ribosomal RNA)) and 19 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes. The inner circle depicts GC content along the genome. The putative non-coding region likely involved in the initiation of the mitogenome replication is not annotated

Table 2.

Gene annotation and arrangement in the mitochondrial genome of Hoplolaimus columbus from South Carolina, USA

| Name | Type | Start | Stop | Length | Start codon | Stop codon | Direction | Anticodon | Intergenic space |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cox1 | Protein | 1 | 1536 | 1536 | TTA | TAG | Forward | 116 | |

| atp6 | Protein | 1551 | 2192 | 642 | ATT | TAG | Forward | 14 | |

| nad5 | Protein | 2248 | 3788 | 1541 | TTA | TT | Forward | 55 | |

| trnD | tRNA | 3789 | 3858 | 70 | Forward | GUC | 0 | ||

| nad2 | Protein | 3859 | 4650 | 792 | TTA | TAG | Forward | 0 | |

| trnI | tRNA | 4715 | 4770 | 56 | Forward | GAU | 64 | ||

| cox3 | Protein | 4766 | 5533 | 768 | TTA | TAA | Forward | − 5 | |

| trnF | tRNA | 5941 | 6009 | 69 | Forward | GAA | 407 | ||

| nad4 | Protein | 6232 | 7476 | 1245 | TTG | TAA | Forward | 222 | |

| cob | Protein | 7509 | 8618 | 1110 | ATA | TAG | Forward | 32 | |

| trnP | tRNA | 8619 | 8672 | 54 | Forward | UGG | 0 | ||

| nad6 | Protein | 8673 | 9122 | 450 | TTA | TAA | Forward | 0 | |

| trnG | tRNA | 9123 | 9179 | 57 | Forward | UCC | 0 | ||

| nad4L | Protein | 9182 | 9412 | 231 | TTA | TAG | Forward | 2 | |

| NCR1 | |||||||||

| trnR | tRNA | 17145 | 17074 | 72 | Reverse | UCG | 7661 | ||

| NCR2 | |||||||||

| trnK | tRNA | 20303 | 20371 | 69 | Forward | UUU | 3157 | ||

| rrnS | rRNA | 20720 | 21317 | 598 | Forward | 348 | |||

| trnS2 | tRNA | 21318 | 21380 | 63 | Forward | UGA | 0 | ||

| trnY | tRNA | 21380 | 21435 | 56 | Forward | GUA | -1 | ||

| trnW | tRNA | 21436 | 21496 | 61 | Forward | UCA | 0 | ||

| trnW | tRNA | 21502 | 21561 | 60 | Forward | CCA | 5 | ||

| nad1 | Protein | 21563 | 22422 | 860 | TTA | GT | Forward | 1 | |

| trnQ | tRNA | 22423 | 22472 | 50 | Forward | UUG | 0 | ||

| trnC | tRNA | 22532 | 22604 | 73 | Forward | GCA | 59 | ||

| trnE | tRNA | 22606 | 22661 | 56 | Forward | UUC | 1 | ||

| trnS1 | tRNA | 22714 | 22771 | 58 | Forward | UCU | 52 | ||

| trnL2 | tRNA | 22772 | 22827 | 56 | Forward | UAA | 0 | ||

| trnV | tRNA | 22864 | 22917 | 54 | Forward | UAC | 36 | ||

| trnL1 | tRNA | 23095 | 23150 | 56 | Forward | UAG | 177 | ||

| cox2 | Protein | 23154 | 23823 | 670 | TTA | T | Forward | 3 | |

| trnH | tRNA | 23824 | 23875 | 52 | Forward | GUG | 0 | ||

| rrnL | rRNA | 23876 | 24776 | 901 | Forward | 0 | |||

| nad3 | Protein | 24777 | 25112 | 336 | ATT | TAA | Forward | 0 |

The PCGs in the mitochondrial genome of H. columbus contained 10,811 nucleotide residues: A = 2712 (26.64%); T = 5210 (51.17%); C = 693 (6.81%); and G = 1565 (15.37%). The strong A + T bias (77.81%) was within the known range reported for mitochondrial genomes in the superfamily Tylenchoidea [25–28]. Among the 12 PCGs, the 2 longest genes were nad5 (1541 bp) and cox1 (1536 bp), and the 2 shortest genes were nad4L (213 bp) and nad3 (336 bp) (Table 2). There were 8 genes that used the start codon TTA (cox1, cox2, cox3, nad1, nad2, nad4L, nad5 and nad6). Both atp6 and nad3 genes used the start codon ATT. The rather unusual start codons TTG of nad4 and ATA of cob have also been reported in other nematode species [25, 27]. Most of the PCGs used the complete stop codon TAG (cox1, atp6, nad2, cob and nad4L) or TAA (cox3, nad4, nad6 and nad3). The exceptions were three genes with incomplete stop codons; nad5(TT); nad1(GT); and cox2(T) (Table 2). The most frequently used codons in the PCGs were TTT (Phe, n = 601 time used, 17.72% of the total), TTA (Leu, n = 398, 11.74%), ATT (Ile, n = 262, 7.73%), ATA (Met, n = 139, 4.10%), AAT (Asn, n = 135, 3.98%), TAT (Tyr, n = 145, 4.28%). Less frequently used codons included GCG (Ala, n = 1, 0.03%), CGC (Arg, n = 1, 0.03%), ACG (Thr, n = 1, 0.03%), CAC (His, n = 2, 0.06%), and TCG (Ser, n = 2, 0.06%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Codon usage analysis of PCGs in the mitochondrial genome of Hoplolaimus columbus from South Carolina, USA

| AmAcid | Codon | Number | /1000 | Fraction | AmAcid | Codon | Number | /1000 | Fraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala | GCG | 1 | 0.29 | 0.02 | Pro | CCG | 3 | 0.88 | 0.05 |

| GCA | 11 | 3.24 | 0.17 | CCA | 13 | 3.83 | 0.23 | ||

| GCT | 43 | 12.68 | 0.66 | CCT | 31 | 9.14 | 0.55 | ||

| GCC | 10 | 2.95 | 0.15 | CCC | 9 | 2.65 | 0.16 | ||

| Cys | TGT | 20 | 5.9 | 0.77 | Gln | CAG | 16 | 4.72 | 0.47 |

| TGC | 6 | 1.77 | 0.23 | CAA | 18 | 5.31 | 0.53 | ||

| Asp | GAT | 65 | 19.17 | 0.94 | Arg | CGG | 8 | 2.36 | 0.3 |

| GAC | 4 | 1.18 | 0.06 | CGA | 7 | 2.06 | 0.26 | ||

| Glu | GAG | 37 | 10.91 | 0.43 | CGT | 11 | 3.24 | 0.41 | |

| GAA | 50 | 14.74 | 0.57 | CGC | 1 | 0.29 | 0.04 | ||

| Phe | TTT | 601 | 177.23 | 0.96 | Ser | AGG | 37 | 10.91 | 0.12 |

| TTC | 23 | 6.78 | 0.04 | AGA | 82 | 24.18 | 0.26 | ||

| Gly | GGG | 38 | 11.21 | 0.19 | AGT | 68 | 20.05 | 0.22 | |

| GGA | 67 | 19.76 | 0.34 | AGC | 3 | 0.88 | 0.01 | ||

| GGT | 85 | 25.07 | 0.42 | TCG | 2 | 0.59 | 0.01 | ||

| GGC | 10 | 2.95 | 0.05 | TCA | 30 | 8.85 | 0.1 | ||

| His | CAT | 49 | 14.45 | 0.96 | TCT | 80 | 23.59 | 0.26 | |

| CAC | 2 | 0.59 | 0.04 | TCC | 10 | 2.95 | 0.03 | ||

| Ile | ATT | 262 | 77.26 | 0.94 | Thr | ACG | 1 | 0.29 | 0.02 |

| ATC | 16 | 4.72 | 0.06 | ACA | 17 | 5.01 | 0.27 | ||

| Lys | AAG | 45 | 13.27 | 0.35 | ACT | 43 | 12.68 | 0.67 | |

| AAA | 82 | 24.18 | 0.65 | ACC | 3 | 0.88 | 0.05 | ||

| Leu | TTG | 101 | 29.78 | 0.17 | Val | GTG | 17 | 5.01 | 0.07 |

| TTA | 398 | 117.37 | 0.68 | GTA | 76 | 22.41 | 0.33 | ||

| CTG | 7 | 2.06 | 0.01 | GTT | 118 | 34.8 | 0.52 | ||

| CTA | 29 | 8.55 | 0.05 | GTC | 18 | 5.31 | 0.08 | ||

| CTT | 43 | 12.68 | 0.07 | Trp | TGG | 36 | 10.62 | 0.44 | |

| CTC | 5 | 1.47 | 0.01 | TGA | 45 | 13.27 | 0.56 | ||

| Met | ATG | 36 | 10.62 | 0.21 | Tyr | TAT | 145 | 42.76 | 0.93 |

| ATA | 139 | 40.99 | 0.79 | TAC | 11 | 3.24 | 0.07 | ||

| Asn | AAT | 135 | 39.81 | 0.98 | End | TAG | 5 | 1.47 | 0.56 |

| AAC | 3 | 0.88 | 0.02 | TAA | 4 | 1.18 | 0.44 |

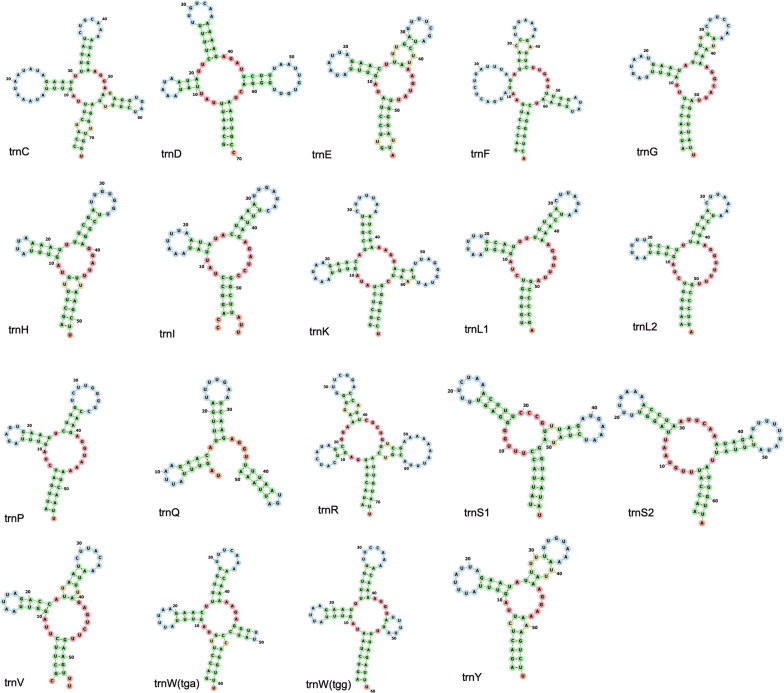

According to the prediction by MiTFi, the mitogenome of H. columbus comprises 19 tRNAs genes, ranging in length from 50 bp (trnQ) to 73 bp (trnC), including 2 trnW genes with different anticodons (UCA and CCA). Most of the tRNA genes encoded in the same direction as the PCGs and the two rRNA genes (rrnS and rrnL), except for the trnR gene which encoded in the opposite direction. There were 4 tRNA genes missing: trnA, trnM, trnN and trnT. Structure predictions of the different tRNAs are shown in Fig. 2. Most often, nematode tRNAs do not exhibit a regular canonical cloverleaf structure, either lacking the T-arm or missing both arms [54, 55]. In H. columbus, variable loops were found on the acceptor stem (trnC and trnE), on the T-stem (trnC, trnR, trnS1 and trnV), and on the anticodon arm (trnE, trnF, trnG, trnR, trnV and trnY). The T-arm was missing in trnE, trnG, trnH, trnL1, trnL2, trnP, trnV and trnY. The D-arm was missing in trnS1 and trnS2. The predicted structure of the trnW(tga) gene had a T-stem but no a T-loop.

Fig. 2.

Secondary structure of tRNAs in the mitochondrial genome of Hoplolaimus columbus predicted by MITFI and FORNA

The rrnS and rrnL genes identified in the mitochondrial genome of H. columbus were 598 bp and 901 bp nucleotide long, respectively (Fig. 1). The rrnS gene was located between trnK and trnS2. The rrnL gene was located next to nad3, between rrnL and nad3, in agreement to that reported for the mitogenomes of Pratylenchus vulnus, Meloidogyne chitwoodi and M. incognita. The overall nucleotide composition of the rrnS gene was A = 30.10%, T = 39.96%, C = 11.37%, and G = 21.57%, and that of the rrnL gene was A = 32.41%, T = 45.84%, C = 7.33%, and G = 14.43%.

Gene overlaps (6 bp in total) were found in 2 gene junctions: trnI-cox3 (5 bp) and trnS2-trnY (1 bp) (Table 2). In turn, relatively short intergenic spaces ranging from 1 to 116 bp were found in 12 gene junctions. Relatively long intergenic spaces were observed in the gene junctions cox3-trnF (407 bp), trnF-nad4 (222 bp), and trnV-trnL1 (177 bp). Microsatellite repeats were detected in some of the above intergenic spaces (Additional file 1: Table S2). Cases of both overlaps and long intergenic spaces have been reported in mitogenomes of plant-parasitic nematodes [25–28].

Two long non-coding regions were identified, which might be useful in the future for nematode population genetics. One long non-coding region was located between the nad4L and trnR genes (NCR1, 7661 bp), and the second one was located between the trnR and trnK genes (NCR2, 3157 bp) (Fig. 1, Table 2). Long non-coding regions > 4000 bp have been reported in other plant-parasitic nematodes such as Pratylenchus vulnus (6847 bp), Meloidogyne chitwoodi (5404 bp), and Meloidogyne incognita (4097 bp), but H. columbus has the longest non-coding regions reported so far. The two regions were heavily A + T rich with an overall base composition of A = 29.79%, T = 39.86%, C = 10.90%, and G = 19.44% in NCR1, and A = 28.10%, T = 50.71%, C = 5.35%, and G = 15.84% in NCR2. Microsatellite repeats were detected in the two NCRs (Additional file 1: Table S3). Tandem repeat finder detected 13 repeats in NCR1 (the longest consensus size of a repeat was 237 bp, and the shortest one was 34 bp long) and 5 repeats in NCR2 (the longest consensus size of a repeat was 23 bp, and the shortest one was 18 bp) (Additional file 1: Table S4). No tandem repeat was found in other shorter intergenic spaces. Secondary structure prediction analysis using RNAFold detected a large number of hairpin structures in the two long NCRs (Additional file 2: Figure S1). Furthermore, a large number of microsatellite sequences were detected in the two non-coding regions (n = 104 and 72 in NCR1 and NCR2, respectively). Altogether, the observed high A + T rich nucleotide content, tandemly repeated sequences, and predicted hairpin secondary structures suggest that these two NCRs are possibly involved in the initiation of replication in the mitochondrial genome of H. columbus; all these features have been observed in the putative mitochondrial genome control region/D-loop of other invertebrates [56–60].

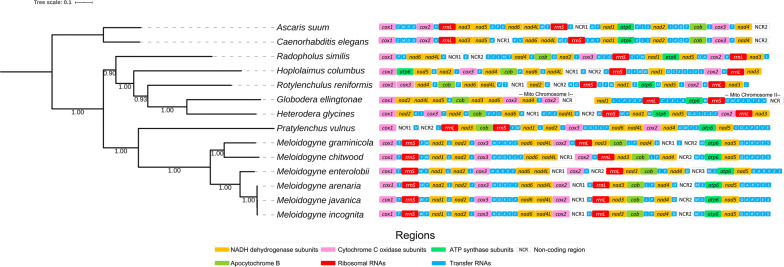

The ML phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 3) confirmed the monophyly of the superfamily Tylenchoidea and placed H. columbus in a monophyletic clade together with Radopholus similis, Rotylenchulus reniformis, Heterodera glycines and Globodera ellingtonae, in agreement with previous molecular phylogenies [24–28]. Our results also supported the position of H. columbus as belonging to the family Hoplolaimidae. Moreover, the analysis revealed Pratylenchus vulnus to be sister to the genus Meloidogyne, and all species belonging to the genus Meloidogyne clustered together into a well-supported monophyletic clade. De Ley & Blaxter [6] recently suggested to classify Meloidogininae as a fully separate family based on the SSU rDNA phylogenies, and their view is supported by our mitophylogenomic analysis.

Fig. 3.

Mitochondrial gene synteny and phylogenetic analysis of Hoplolaimus columbus and related species. Phylogenetic tree obtained from Maximum Likelihood analysis was based on a concatenated alignment of nucleotides of the 12 protein-coding genes that presented in accessible mitochondrial genomes of plant-parasitic nematodes in the class Chromodorea, superfamily Tylenchoidea. In the analysis, Caenorhabditis elegans and Ascaris suum were used as the outgroup. Numbers at the branches represent bootstrap values. The optimal molecular evolution model estimated with SMS was the GTR model for all 12 partitions

The synteny of protein-coding genes, ribosomal RNA genes, and non-coding regions observed in H. columbus was compared with that of other species in the same superfamily Tylenchoidea with completely annotated mitogenomes available in GenBank (Fig. 3). The mitogenome synteny of Rotylenchulus reniformis was not available in GenBank and was predicted in this study using the web server MITOS. A unique gene order was found in H. columbus, and this order is somewhat similar to that reported for other species in the same superfamily (Fig. 3). A visual comparison between phylogenetic relatedness and gene synteny also suggests that synteny might represent a useful phylogenetic character in this clade; a correlation between phylogenetic relatedness and gene synteny was observed in the studied plant-parasitic nematodes (Fig. 3) although variability is relatively high considering that the comparison was made among different genera belonging to the superfamily Tylenchoidea.

Conclusions

This study de novo assembled, for the first time, the mitochondrial genome of H. columbus, a result that also represented the first mitochondrial genome description for the genus Hoplolaimus. The mitogenome of H. columbus had a relatively large size compared to that of other plant-parasitic nematodes, exhibits long non-coding regions, and has a unique gene order within the superfamily Tylenchoidea. The mitophylogenomic analysis also agreed with a previous phylogenic hypothesis established using the SSU rDNA marker, and confirmed the taxonomic relationships among species in the superfamily Tylenchoidea. Ultimately, we envision that this new genomic resource in H. columbus will help to improve our knowledge about the biology and population genetics of this economically and ecologically relevant agricultural pathogen both in Asia and North America

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Model selection for phylogenetic analysis by smart model selection (SMS). Table S2. Microsatellite repeats in intergenic spaces. Table S3. Microsatellite repeats in non-coding regions. Table S4. Tandem repeats in non-coding regions.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Secondary structure prediction analysis of non-coding regions in the mitochondrial genome of Hoplolaimus columbus by FORNA.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge South Carolina Cotton Board award number SC15-130.

Abbreviations

- ML

maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis

- NCR

non-coding region

- PCGs

protein coding genes

- rrnS

12S ribosomal RNA

- rrnL

16S ribosomal RNA

- SSU rDNA

small subunit ribosomal DNA

- tRNA

transfer RNA

Authors’ contributions

XM, PA, VPR and JAB conceived, designed and supervised the study, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by project SC15-130 from the South Carolina Cotton Board granted to PA.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The mitochondrial genome sequence is available in the GenBank database under the accession number MH657221.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xinyuan Ma, Email: xm@g.clemson.edu.

Paula Agudelo, Email: pagudel@clemson.edu.

Vincent P. Richards, Email: vpricha@clemson.edu

J. Antonio Baeza, Email: baeza.antonio@gmail.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13071-020-04187-y.

References

- 1.Koenning SR, Overstreet C, Noling JW, Donal PA, Becker JO, Fortnum BA. Survey of crop losses in response to phytoparasitic nematodes in the United States for 1994. J Nematol. 1999;31:587–618. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siddiqi MR. Tylenchida parasites of plants and insects. 2. Wallingford: CABI Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abadm P, Gouzy J, Aury J, Castagnone-Sereno P, Danchin EGJ, Deleury E, et al. Genome sequence of the metazoan plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sher SA. Revision of the Hoplolaiminae (Nematoda) II. Hoplolaimus Daday, 1905 and Aorolaimus N. Gen. Nematologica. 1963;9:267–296. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bae CH, Robbins RT, Szalanski AL. Molecular identification of some Hoplolaimus species from the USA based on duplex PCR, multiplex PCR and PCR-RFLP analysis. Nematology. 2009;11:471–480. [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Ley P, Blaxter ML. Systematic position and phylogeny. In: Lee DL, editor. The biology of nematodes. London: Taylor and Francis; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma X, Agudelo P, Mulluer JD, Knap HT. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of Hoplolaimus stephanus. J Nematol. 2011;43:25–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis SA, Fassuliotis G. Lance nematodes, Hoplolaimus spp., in the Southern United States. In: Riggs RD, editor. Nematology in the southern region of the United States. Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station: Southern Cooperative Series Bulletin; 1982.

- 9.Astudillo GE, Birchfield W. Pathology of Hoplolaimus columbus on sugarcane. Phytopathology. 1980;70:565. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gazaway WS, Armstrong B. First report of Columbia lance nematode (Hoplolaimus columbus) on cotton in Alabama. Plant Dis. 1994;78:640. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appel JA, Lewis SA. Pathogenicity and reproduction of Hoplolaimus columbus and Meloidogyne incognita on Davis soybean. J Nematol. 1984;16:349–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis SA, Smith FH, Powell WM. Host-parasite relationships of Hoplolaimus columbus on cotton and soybean. J Nematol. 1976;8:141–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller JD, Sanders GB. Control of Hoplolaimus columbus on late-planted soybean with aldicarb. J Nematol. 1987;19:123–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noe JP. Damage functions and population changes of Hoplolaimus columbus on cotton and soybean. J Nematol. 1993;25:440–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holguin CM, Baeza JA, Mueller JD, Agudelo P. High genetic diversity and geographic subdivision of three lance nematode species (Hoplolaimus spp.) in the United States. Ecol Evol. 2015;5:2929–2944. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holguin CM, Ma X, Mueller JD, Agudelo P. Distribution of Hoplolaimus species in soybean fields in South Carolina and North Carolina. Plant Dis. 2016;100:149–153. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-12-14-1332-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma X, Robbins RT, Bernard EC, Holguín CM, Agudelo P. Morphological and molecular characterisation of Hoplolaimus smokyensis n. sp. (Nematoda: Hoplolaimidae), a lance nematode from Great Smoky Mountains National Park, USA. USA. Nematology. 2019;21:923–935. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blaxter ML, De Ley P, Garey JR, Liu LX, Scheldeman P, Vierstraete A, et al. A molecular evolutionary framework for the phylum Nematoda. Nature. 1998;392:71–75. doi: 10.1038/32160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holterman M, van der Wurff A, van den Elsen S, van MEgen H, Bongers T, Holovachov O, et al. Phylum-wide analysis of SSU rDNA reveals deep phylogenetic relationships among nematodes and accelerated evolution toward crown Clades. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1792–1800. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Elsen S, Holovachov O, Karssen G, van Megen H, Helder J, Bongers T, et al. A phylogenetic tree of nematodes based on about 1200 full-length small subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Nematology. 2009;11:927–950. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powers TO, Todd TC, Burnell AM, Murray PCB, Fleming CC, Szalanski AL, et al. The rDNA internal transcribed spacer region as a taxonomic marker for Nematodes. J Nematol. 1997;29:441–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon C, Frati F, Beckenbach A, Crespi B, Liu H, Flook P. Evolution, weighting, and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial gene sequences and a compilation of conserved polymerase chain reaction primers. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1994;87:651–701. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Kern E, Kim T, Sim M, Kim J, Kim Y, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of two Plectus mitochondrial genomes (Nematoda: Plectida) supports a sister group relationship between Plectida and Rhabditida within Chromadorea. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;107:90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun L, Zhuo K, Lin B, Wang H, Liao J. The complete mitochondrial genome of Meloidogyne graminicola (Tylenchina): a unique gene arrangement and its phylogenetic implications. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e98558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sultana T, Kim J, Lee S, Han H, Kim S, Min G, et al. Comparative analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequences confirms independent origins of plant-parasitic nematodes. BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphreys-Pereira DA, Elling AA. Mitochondrial genomes of Meloidogyne chitwoodi and M. incognita (Nematoda: Tylenchina): comparative analysis, gene order and phylogenetic relationships with other nematodes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2014;194:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J, Lee S, Gazi M, Kim T, Jung D, Chun J, et al. Mitochondrial genomes advance phylogenetic hypotheses for Tylenchina (Nematoda: Chromadorea) Zool Scripta. 2015;44:446–462. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips WS, Brown AMV, Howe DK, Peetz AB, Blok VC, Denver DR, et al. The mitochondrial genome of Globodera ellingtonae is composed of two circles with segregated gene content and differential copy numbers. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:706. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3047-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkins WR. A rapid centrifugal-flotation technique for separating nematodes from soil. Plant Dis. 1964;48:692. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Handoo Z, Golden AM. A key and diagnostic compendium to the species of the genus Hoplolaimus Daday, 1905 (Nematoda: Hoplolaimidae) J Nematol. 1992;24:45–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leroy S, Duperray C, Morand S. Flow cytometry for parasite nematode genome size measurement. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;128:91–93. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dierckxsens N, Mardulyn P, Smits G. NOVOPlasty: de novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e18. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;15:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chevreux B, Wetter T, Suhai S. Genome sequence assembly using trace signals and additional sequence information. In: Computer Science and Biology: Proceedings of the German Conference on Bioinformatics (GCB), 4–6 October 1999. Hanover, Germany; 1999;99:45–56.

- 36.Hahn C, Bachmann L, Chevreux B. Reconstructing mitochondrial genomes directly from genomic next-generation sequencing reads—a baiting and iterative mapping approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e129. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernt A, Donath A, Jühling F, Externbrink F, Florentz C, Fritzsch G, et al. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol Phyl Evol. 2013;69:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Artimo P, Jonnalagedda M, Arnold K, Baratin D, Csardi G, de Castro E, et al. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:597–603. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jühling F, Pütz J, Bernt M, Donath A, Middendorf M, Florentz C, et al. Improved systematic tRNA gene annotation allows new insights into the evolution of mitochondrial tRNA structures and into the mechanisms of mitochondrial genome rearrangements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:2833–2845. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kerpedjiev P, Hammer S, Hofacker IL. Forna (force-directed RNA): simple and effective online RNA secondary structure diagrams. Bioinformatics. 2015;1:3377–3379. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stothard P. The Sequence Manipulation Suite: JavaScript programs for analyzing and formatting protein and DNA sequences. Biotechniques. 2000;28:1102–1104. doi: 10.2144/00286ir01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grant JR, Stothard P. The CGView Server: a comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:181–184. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bikandi J, San Millán R, Rementeria A, Garaizar J. In silico analysis of complete bacterial genomes: PCR, AFLP-PCR and endonuclease restriction. Bioinformatics. 2004;22:798–799. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Höner zu Siederdissen C. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol Biol. 2011;6:26. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuraku S, Zmasek CM, Nishimura O, Katoh K. aLeaves facilitates on-demand exploration of metazoan gene family trees on MAFFT sequence alignment server with enhanced interactivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:22–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, et al. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:465–469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dereeper A, Audic S, Claverie JM, Blanc G. BLAST-EXPLORER helps you building datasets for phylogenetic analysis. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Criscuolo A, Gribaldo S. BMGE (Block Mapping and Gathering with Entropy): selection of phylogenetic informative regions from multiple sequence alignments. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaidya G, Lohman DJ, Meier R. SequenceMatrix: concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics. 2011;27:171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2010.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lefort V, Longueville J, Gascuel O. SMS: smart model selection in PhyML. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:2422–2424. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trifinopoulos J, Nguyen LT, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:232–235. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:256–259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palomares-Rius JE, Cantalapiedra-Navarrete C, Archidona-Yuste A, Blok VC, Castillo P. Mitochondrial genome diversity in dagger and needle nematodes (Nematoda: Longidoridae) Sci Rep. 2017;7:41813. doi: 10.1038/srep41813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang D, Hewitt G. Insect mitochondrial control region: a review of its structure, evolution and usefulness in evolutionary studies. Biochem Syst Ecol. 1997;25:99–120. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuhn K, Streit B, Schwenk K. Conservation of structural elements in the mitochondrial control region of Daphnia. Gene. 2008;420:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li T, Yang J, Li Y, Cui Y, Xie Q, Bu W, et al. A mitochondrial genome of Rhyparochromidae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) and a comparative analysis of related mitochondrial genomes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:351375. doi: 10.1038/srep35175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baeza JA. The complete mitochondrial genome of the Caribbean spiny lobster Panulirus argus. Sci Rep. 2018;8:17690. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baeza JA, Sepúlveda FA, González MT. The complete mitochondrial genome and description of a new cryptic species of Benedenia Diesing, 1858 (Monogenea: Capsalidae), a major pathogen infecting the yellowtail kingfish Seriola lalandi Valenciennes in the South-East Pacific. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:490. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3711-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jacob JE, Vanholme B, Van Leeuwen T, Gheysen G. A unique genetic code change in the mitochondrial genome of the parasitic nematode Radopholus similis. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:192. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Model selection for phylogenetic analysis by smart model selection (SMS). Table S2. Microsatellite repeats in intergenic spaces. Table S3. Microsatellite repeats in non-coding regions. Table S4. Tandem repeats in non-coding regions.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Secondary structure prediction analysis of non-coding regions in the mitochondrial genome of Hoplolaimus columbus by FORNA.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The mitochondrial genome sequence is available in the GenBank database under the accession number MH657221.