Abstract

Background

Increasing the number of women in surgical subspecialties has been challenging, especially in orthopaedics, in which the percentage of women has remained relatively the same for the past several decades. Certain subspecialties, such as pediatric orthopaedics, have a greater proportion of women than other orthopaedic subspecialties do. Women in leadership roles in a specialty society (for example, on the board of directors) may serve as role models and help attract women to our specialty, leading to increased diversity. As the proportion of women in a specialty society increases, the leadership (board of directors) of the society might reflect the gender composition of that society’s membership. It is not known whether gender diversity in orthopaedic societies is reflected in their leadership.

Question/purposes

(1) Does the percentage of women members in a specialty society correlate with the percentage of women on its board of directors? (2) Does having a junior position on an orthopaedics subspecialty society’s board of directors correlate with an increased percentage of women on its board of directors?

Methods

We queried the executive directors of each of the 23 societies of the Board of Specialty Societies of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons to obtain the number and percentage of women members in each society, the number of women on each society’s board of directors, the criteria for becoming a board member, and the presence or absence of junior board members. All 23 societies responded. We supplemented the data by reviewing these societies’ bylaws. Society bylaws were studied to determine if the presence of a junior board member affected the percentage of women on its board of directors. We correlated the percentage of women in each society with the percentage of women on that society’s board of directors and compared this across the studied societies.

Results

We found a strong correlation between the percentage of women in a society and the percentage of women on the society’s board of directors (r2 = .2333; p = .0495). The subspecialty society with the highest percentage of women (26%), the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America, did not have the highest percentage of women on its board of directors (three of 20 members were women, 15%). The subspecialty society with the highest percentage of women on its board of directors, the Orthopaedic Research Society (seven of 16 members, 44%), did not have the highest percentage of women (25%). There was no correlation between presence of a junior board member and increased percentage of women in an orthopaedic society, nor was there a correlation between the presence of a junior board member and percentage of women on the board of directors in a society.

Conclusions

There is a correlation between the number of women members in an orthopaedic specialty society and the number of women on its board of directors. The correlation is not explained by the presence of a junior member position, which may be inspiring to younger women. Although a correlation exists, we could not predictably match societies with the highest percentage of women members to those with the highest percentage of women on their boards of directors, and vice versa. This study reveals the current percentage of women in orthopaedic specialty societies and the percentage of women in leadership positions. This is the first step towards diversity of gender in orthopaedics.

Level of Evidence

Level III, prognostic study.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, the percentage of women in medical schools has steadily increased. In 1975, 20.5% of medical students were women [3]. By 2015, this number had increased to 46.8% [3]. Running parallel to this trend is another: the increasing percentage of women entering surgical subspecialties. From 1978 to 2013, the percentage of urology residents who were women increased from 0.9% to 23.8% [11]. In 2013, the percentage of plastic surgeons who were women was reported to be 14.2%, and that for women general surgeons was 17.6% [1]. However, the percentage of women in orthopaedic surgery has not kept pace with the percentage of women in other surgical subspecialties. The percentage of women residents in orthopaedic surgery has remained relatively the same. According to the 2014 Orthopaedic Practice in the US Survey, the percentage of women in orthopaedics has increased, but only marginally, from 4.0% in 2008 to 5.7% in 2014 [4]. The results of the 2016 Orthopaedic Practice in the US Survey showed a similar trend; only 4.0% of orthopaedic surgeons aged 60-69 and 13.6% of orthopaedic surgeons younger than 40 were women [5]. As of 2018, 35.2% of practicing physicians were women [2]. The leadership of orthopaedic societies appears to reflect their membership; boards of directors are composed mostly of men. However, as the number of women in orthopaedic societies has increased, has the composition of the board of directors undergone a similar trend?

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) includes orthopaedic surgeons of all subspecialties. Subspecialty societies have a relationship with the AAOS through the Board of Specialty Societies, which is composed of 23 member societies. The intent of this study was to examine the percentage of women members and the percentage of women on the board of directors of orthopaedic specialty societies and the AAOS. To better understand the number of women in leadership roles in orthopaedic societies (that is, on the boards of directors), we wished to obtain objective data regarding women’s membership in specialty societies and in the AAOS. The leadership of specialty societies ideally correlates with at least as high a percentage of women on the board of directors as being reflective of the membership. Ideally, a society’s leadership would reflect the makeup of the membership in terms of the percentage of women. The inverse is also true, because women leaders and role models ideally attract more women into their field. In addition, some societies have positions on their board of directors specifically for more junior members. Because women members might comprise a younger or more junior portion of a particular society, and because the percentage of women in orthopaedic surgery residency is higher than the percentage of women in the AAOS, this study also sought to examine the presence of junior board positions in correlation with the percentage of women on the boards of directors of these societies. It is not known whether gender diversity in orthopaedic societies is reflected in their leadership. We therefore sought to determine the correlation between the percentage of women members in a specialty society and the percentage of women on that society’s board of directors. Because younger members are more likely to be women than older members, another strategy to promote gender diversity may be to reserve junior positions on societies’ boards of directors. We also attempted to correlate the presence of a junior board position with the percentage of women on the board of directors.

We therefore asked: (1) Does the percentage of women members in a specialty society correlate with the percentage of women on its board of directors? (2) Does having a junior position on an orthopaedics subspecialty society’s board of directors correlate with an increased percentage of women on its board of directors?

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

We queried 23 societies, including six surgical interest societies, belonging to the Board of Specialty Societies of the AAOS in 2018 (Table 1). We sent a survey to the executive directors of the Board of Specialty Societies to obtain objective data on memberships and board of director compositions. We contacted the executive directors via email with permission from the Board of Specialty Societies. Institutional review board approval was not necessary because this was a survey in which we did not collect personal data.

Table 1.

Board of Specialty Societies member organizations 2018

Description of Experiment, Treatment or Surgery

We asked each society to provide the percentage (not the raw number) of women members in their society, the gender composition of the board of directors (number of women and total number of people on the board of directors), the requirements for eligibility to be on the board of directors, and a description of the eligibility of junior members, if such a position existed.

We also reviewed the website of each of the societies of the Board of Specialty Societies for details on board composition and a description of requirements for board of directors positions.

Variables, Outcome Measures, Data Sources, and Bias

Our primary study endpoint was to determine whether there was a correlation between the percentage of women in orthopaedic subspecialty societies and in the AAOS and the percentage of women on that society’s board of directors. To assess this, we queried the subspecialty societies and AAOS to obtain the percentage of women in each society and the percentage of women on the society’s boards of directors.

Our secondary study endpoint was to determine whether the presence of a junior board member correlated with a higher percentage of women in a society’s membership or on that society’s board of directors. To assess this, we queried the societies to determine which had junior board members, and we examined the correlation between the presence of junior board members and a higher percentage of women on that society’s board of directors.

To obtain data, we sent electronic mail to the executive directors of the specialty societies and AAOS, and we followed up with a phone call if necessary. We then calculated the number of women members of each society as a percentage of the total membership of that society. We obtained the number of women on each specialty society’s board of directors through survey results and review of the society’s website. We then calculated this number as a percentage of the total composition of the board of directors. The percentage of women on the surgical specialty society’s board of directors was tabulated and placed in ascending order.

Accounting

All 23 societies responded with the percentage of women on their board of directors and presence of junior board member positions. Three of the 23 societies (13%) did not provide the percentage of women in their society (the Limb Lengthening and Reconstruction Society, American Association for Hand Surgery, and American Spinal Injury Association). The following two societies were not included in the statistical analysis: the Ruth Jackson Orthopaedic Society and the J. Robert Gladden Orthopaedic Society. The Ruth Jackson Orthopaedic Society’s mission is to “promote professional development of and for women in orthopaedics throughout all stages of their careers” [15] and the mission of the J. Robert Gladden Orthopaedic Society is to “increase diversity within the orthopaedic profession and promote the highest quality musculoskeletal care for all people” [13]. The J. Robert Gladden Orthopaedic Society is a pluralist, multicultural organization designed to meet the needs of underrepresented minority orthopaedic surgeons and to advance the ideals of excellent musculoskeletal care for all patients, with particular attention to underserved groups. Because these societies are mission-driven for women and underrepresented minorities and their mission mindfully represents diversity, we excluded them from the sample. We wanted the results of our study to reflect women’s membership in surgical specialty groups and their representation on these societies’ boards of directors.

Statistical Analysis, Study Size

A statistical analysis comparing the percentage of women in orthopaedic societies with the percentage of women on these societies’ board of directors was performed using a regression analysis; r2 and p value were reported. We compared the presence or absence of junior members on the board of directors with the percentage of women in the society using a t test. We compared the presence or absence of junior members on the board of directors with the percentage of women on the board of directors using a t test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant for all three comparisons. The statistics were analyzed using a Casio linear regression calculator (https://keisan.casio.com, Casio Computer Company, Tokyo, Japan, 2009).

Results

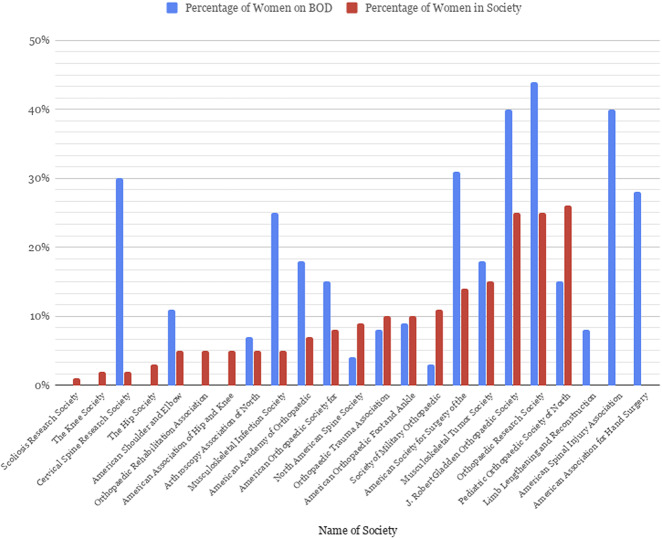

There was a strong correlation between the percentage of women in a society and the percentage of women on its board of directors (r2 = .2333; p < .05) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The percentage of women in specialty societies compared with the percentage of women on the boards of directors is shown. There was a strong correlation between the percentage of women in a particular society and the percentage of women on its board of directors (r2 = .2333; p = .0495; p < 0.001).

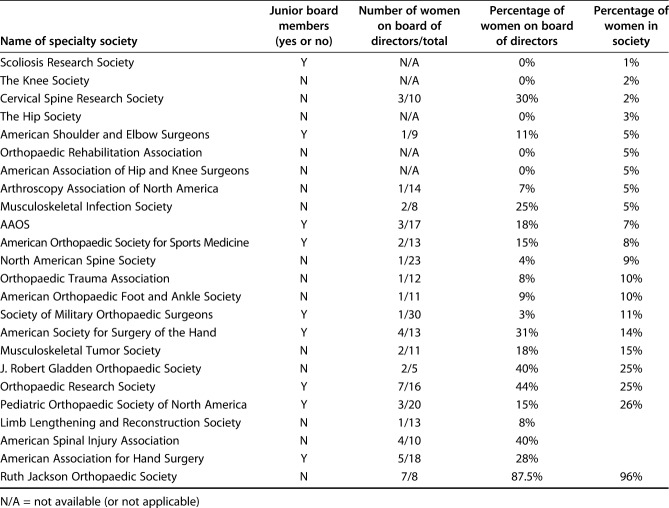

Nine surgical societies had a higher percentage of women on their boards of directors than in their societies (Fig. 2): the Cervical Spine Research Society (three of 10 board of directors members were women, 30%; 2% women members in the society), American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (one of nine board of directors members were women, 11%; 5% women members), Arthroscopy Association of North America (one of 14 board of directors members were women, 7%; 5% women members), Musculoskeletal Infection Society (two of eight were women, 25%; 5% women members), AAOS (three of 17 were women, 18%; 7% women members), American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (two of 13 were women, 15%; 8% women members), American Society for Surgery of the Hand (four of 13 were women, 31%; 14% women members), Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (two of 11 were women, 18%; 15% women members), and Orthopaedic Research Society (seven of 16 were women, 44%; 25% women members). Ten societies had a higher percentage of women in their societies than on their board of directors: the Scoliosis Research Society (1% women members; 0 women on the board of directors), Knee Society (2% women members; 0 women on the board of directors), Hip Society (3% women members; 0 women on the board of directors), Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Association (5% women members; 0 women on the board of directors), American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (5% women members; 0 women on the board of directors), North American Spine Society (9% women members; one of 23 board members was a woman [4%]), Orthopaedic Trauma Association (10% women members; one of 12 board members was a woman [8%]), American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (10% women members; one of 11 board members was a woman [9%]), Society of Military Orthopaedic Surgeons (11% women members; one of 30 board members was a woman [3%]), and the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (26% women members; three of 20 board members were women [15%]) (Table 2). The Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America ranked first in the percentage of women members, but it ranked sixth for the percentage of women on its board of directors.

Fig. 2.

The percentage of women in specialty societies compared with the percentage of women on the boards of directors is shown for each orthopaedic society queried. Five surgical societies had a higher percentage of women on their board of directors than in their societies: the Cervical Spine Research Society, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons, Arthroscopy Association of North America, American Society for Surgery of the Hand, and the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society.

Table 2.

Presence of junior members and gender demographics for specialty societies

Other Relevant Findings

Five surgical societies (22%) and one specialty interest society reported having no women on their board of directors. These were the Scoliosis Research Society, Knee Society, Hip Society, Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Society, and American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons.

Although certain societies have a “junior board member,” in which the age requirement of active year requirement is lower (defined as a board member either under a certain age or within a specified number of years of beginning practice) the presence of a junior board member did not correlate with an increased percentage of women on the board of directors (t = .79; p = .22) or with an increased percentage of women in the society (t = 1.18; p = .13).

Discussion

Increasing gender diversity in orthopaedics is an important goal. Examples outside orthopaedic surgery suggest that under some circumstances, women may have better outcomes when treated by women physicians. For example, women were more likely to survive a heart attack when their emergency department physician was a woman [10]. In addition, women college students were found to be more likely to accept HPV vaccine from a woman physician or clinician [12]. These studies suggest that better care is delivered from a more diverse physician workforce. Gender diversity in thought and leadership best serves the medical profession. Physicians should mirror the population they serve, which is made up of 51% women. Women comprise more than 50% of medical school classes and have for some time. Increasing the percentage of women in some surgical subspecialties has been a challenge. Although some surgical subspecialties see increasing percentages of women, the number of women in orthopaedics has remained relatively the same for the past several years, at 13% to 15% of residents [14, 16, 17]. Gender diversity in orthopaedic leadership may improve gender diversity in orthopaedic societies.

This study has several limitations. We examined each society’s membership and the composition of its board of directors in 2017, at one point in time. This is useful because transparency in the gender composition of specialty societies is an important baseline to establish. In the future, we plan to examine trends, with a repeat analysis in 5 years. Second, we did not query the societies regarding the percentage of women who were candidates for membership. We only included full and active members of these societies. The increased percentage of women residents, which has been greater than 10% every year since 2004-2005, might contribute to an increase in the percentage of women in orthopaedic societies [16]. Currently, it is not clear if there is attrition of women residents who do not join societies or practice orthopaedic surgery after residency. Even without the gender percentage of junior or candidate members, the percentage of women who are active members compared with the percentage of women on a society’s board of directors is imperative to understand as a baseline from which to improve. We also did not ask about the number of women and the total number of members in each society, only the percentage of women in these societies. This oversight made statistical comparisons problematic, but we feel that knowing the percentages of women in these societies is still useful for comparison with the percentage of board of directors who are women. Further research is necessary to determine whether the higher percentage of women in leadership roles in orthopaedic societies correlates with an increase in women joining the subspecialty and society.

There was a strong correlation between the percentage of women in a society and the percentage of women on that society’s board of directors. This study determined that women in orthopaedic societies are reflected in their societies’ leadership to some degree. As this is studied over time, it remains to be seen whether the percentage of women in a society’s leadership predicts the percentage of women who will join that society in the future, or whether the percentage of women in an orthopaedic society predicts the percentage of women who will serve in that society’s leadership in the future. The intent of transparent reporting of this information is to encourage the field of orthopaedics to increase gender diversity in career choice, membership, and leadership. The boards of directors of both the American Society for Surgery of the Hand and American Association for Hand Surgery are more than 25% women. Likewise, gender diversity among orthopaedic hand surgeons has markedly increased, from 5% to 10% in 1995 to 15% to 20% in 2012 [6]. The American Society for Surgery of the Hand has taken active steps to increase diversity; its diversity committee collaborates with committees from other societies to increase awareness, education, and services for diverse populations. Women in orthopaedics, similar to men, require expertise and experience to become leaders. Seniority is a component, and as women enter the ranks of their societies, time must be spent in committee work and other involvement to earn a seat among leaders. The hand societies may be at the forefront of this phenomenon. When a minority reaches 25%, a tipping point exists at which that minority’s influence over the group becomes substantial [8]. The hand societies have reached this tipping point. The expectation is that minority input from women in leadership will trigger change at a faster pace in the future.

This study demonstrates that even in specialty societies with a high percentage of women members, leadership roles do not correlate with membership composition, and more work needs to be done. In the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society, Orthopaedic Research Society, and J. Robert Gladden Society, 26%, 25%, and 25% of members, respectively, are women. The board of directors of the J. Robert Gladden Society is 40% women, perhaps bolstered by this society’s mission to promote diversity. The Orthopaedic Research Society’s board of directors has the highest percentage of women among all of the nongender diversity-specific specialty societies. This society’s membership includes biologists, veterinarians, and engineers in addition to orthopaedic surgeons. One of the seven women on this society’s board of directors is an orthopaedic surgeon. The Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America’s percentage of women members far exceeds the percentage of women on its board of directors. The percentage of women applying to pediatric orthopaedic fellowships echoes the percentage of women in the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America at 25% (79 of 318 members) as of 2016 [7]. The disparity between the percentage of women members and the percentage of women on the boards of directors of these societies may be owing to a time delay; perhaps the women who will ascend to leadership positions have not had sufficient time to gain appropriate expertise and experience. In addition, boards of directors tend to comprise academic surgeons. Women comprise only 18% of orthopaedic academic faculty [9]. Societies should aim to reflect the diversity of membership in their leadership positions. Women who have ascended to leadership positions cannot be alone in this pursuit. Men as allies are imperative to diversity, and a recommendation is for men to join the mission to diversify orthopaedic surgery, to maintain excellence in patient care by reflecting our patient population and striving for diversity of thought.

There was no correlation between the presence of a junior board member and a higher percentage of women on a society’s board of directors. Our supposition that the presence of a junior board member on a society’s board of directors would correlate with a higher percentage of women was not apparent in these data. We based this supposition on a theory that women are younger and newer to society membership, and that junior board membership might create an entry point to leadership to include these women at a higher rate than the more senior positions. The junior board member position is an opportunity to increase gender diversity because the group of women at this career stage is larger than for senior positions. This did not appear to be the case in our analysis, but with time and more of these junior board membership opportunities, women might gain leadership experience and rise in the leadership ranks in specialty societies. Societies that wish to increase diversity may choose to use this strategy to include qualified younger women in leadership positions.

The number and percentage of women in orthopaedic surgery is increasing overall. This study has provided an understanding of which orthopaedic societies have the highest and lowest percentages of women members, and which society's leadership reflects diversity (or lack thereof) of women. Transparency is the beginning step toward diversity and inclusion, and ultimately equity. This is a first step in creating transparency. We hope that this information will inform societies and be useful to them as they consider ways to include more women in society leadership and in our profession. In addition, as women in orthopaedic residency choose their specialty, facts for understanding the gender composition of these specialties may be useful.

Acknowledgments

We thank the executive directors of the studied orthopaedic societies for providing us with the information required to do this study.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that neither she, nor any member of her immediate family, has no commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that her institution waived approval for the reporting of this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

References

- 1.AAMC 2014 Physician Specialty Data Book. Available at https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/439208/specialtydataandreports.html. Date accessed: February 14, 2018.

- 2.AAMC 2018 Physician Specialty Data Book. Available at https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/492560/1-3-chart.html. Date accessed: February 14, 2018.

- 3.AAMC Table 1: Medical Students, Selected Years, 1965-2015. Available at https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/. Date accessed: February 14, 2018.

- 4.AAOS OPUS 2014. Available at www.aaos.org/2014OPUSReport. Accessible to AAOS members. Date accessed: February 14, 2018.

- 5.AAOS OPUS 2016. Available at www.aaos.org/2016OPUSReport. Accessible to AAOS members. Date accessed: February 14, 2018.

- 6.Bae GH, Lee AW, Park DJ, Maniwa K, Zurakowski D, ASSH Diversity Committee, Day CS. Ethnic and gender diversity in hand surgery trainees. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:790-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannada LK. Women in orthopaedic fellowships: what is their match rate, and what specialties do they choose? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1957-1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centola D, Becker J, Brackbill D, Baronchelli A. Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention. Science. 2018;360:1116-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chambers CC, Ihnow SB, Monroe EJ, Suleiman LI. Women in orthopaedic surgery—Population trends in trainees and practicing surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient–physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:8569-8574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halpern JA, Lee UJ, Wolff EM, Mittal S, Shoag JE, Lightner DJ, Kim S, Hu JC, Chughtai B, Lee RK. Education: women in urology residency, 1978-2013: a critical look at gender representation in our specialty. Urology. 2016;92:20-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez ND, Daley EM, Young L, Kolar SK, Wheldon C, Vamos CA, Cooper D. HPV vaccine recommendations: does a health care provider's gender and ethnicity matter to Unvaccinated Latina college women? Ethn Health. 2017;1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robert Gladden J. Orthopaedic Society Mission. Available at http://www.gladdensociety.org/index.php/about/mission. Date accessed: February 14, 2018.

- 14.O'Connor MI. Medical school experiences shape women students' interest in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1967-1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruth Jackson Orthopaedic Society Mission. Available at http://www.rjos.org/index.php/about. Date accessed: February 14, 2018.

- 16.Van Heest AE, Agel J. The uneven distribution of women in orthopaedic surgery resident training programs in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Heest AE, Fishman F, Agel J. A 5-year update on the uneven distribution of women in orthopaedic surgery residency training programs in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]