Abstract

In this study, we describe the additive manufacturing of porous three-dimensionally (3D) printed ceramic scaffolds prepared with hydroxyapatite (HA), β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), or the combination of both with an extrusion-based process. The scaffolds were printed using a novel ceramic-based ink with reproducible printability and storability properties. After sintering at 1200°C, the scaffolds were characterized in terms of structure, mechanical properties, and dissolution in aqueous medium. Microcomputed tomography and scanning electron microscopy analyses revealed that the structure of the scaffolds, and more specifically, pore size, porosity, and isotropic dimensions were not significantly affected by the sintering process, resulting in scaffolds that closely replicate the original dimensions of the 3D model design. The mechanical properties of the sintered scaffolds were in the range of human trabecular bone for all compositions. All ceramic bioinks showed consistent printability over a span of 14 days, demonstrating the short-term storability of the formulations. Finally, the mass loss did not vary among the evaluated compositions over a period of 28 days except in the case of β-TCP scaffolds, in which the structural integrity was significantly affected after 28 days of incubation in phosphate-buffered saline. In conclusion, this study demonstrates the development of storable ceramic inks for the 3D printing of scaffolds of HA, β-TCP, and mixtures thereof with high fidelity and low shrinkage following sintering that could potentially be used for bone tissue engineering in load-bearing applications.

Impact statement

In this study, we developed a novel ceramic ink for the preparation of porous ceramic scaffolds useful in bone tissue engineering. The ready-to-use ink can be stored for at least 14 days and printed using printing parameters compatible with any commercially available bioprinter. The composition of the ink can be adapted to incorporate the most relevant ceramics for bone tissue engineering, including hydroxyapatite and β-tricalcium phosphate, without affecting the printability or storability properties. The high ceramic content of the ink and the low shrinkage after sintering enable the custom fabrication of patient-specific tissue-engineered scaffolds.

Keywords: 3D printing, sintering, bone regeneration, ceramic ink, calcium phosphate, hydroxyapatite

Introduction

Bone defects due to trauma, osteodegenerative disease, or tumor resection pose a clinical challenge which may require a therapeutic solution that promotes host bone cell proliferation while providing a structural framework to withstand the loading conditions experienced by bone tissue.1 Autografts and allografts are used clinically to repair or regenerate bone defects, but may have issues of incomplete integration with the host tissue, graft failure, arthrofibrosis, infection, and long-term failure of their mechanical strength.2,3 For many of the experimental treatments developed in recent years, including the use of synthetic scaffolds, a variety of challenges still exist that prevent the proper formation of new tissue that replicates the structure and function of native bone tissues.4–6

Calcium phosphates, such as hydroxyapatite (HA) and β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), are considered the most relevant ceramics in bone tissue engineering because of their reported osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties.7,8 The sintering of ceramic powders using high temperatures for a prolonged amount of time is a common strategy for the preparation of ceramic scaffolds.9 In general, these scaffolds are prepared in the form of cubes or cylinders and need to be adapted to the specific location during surgery to match the defect site, resulting in an increase in the surgery time and the poor fit and shape compared to the defect environment and structure. The lack of precision and accuracy in the fabrication of bone tissue engineering scaffolds remains a challenge for the replication of the structure of trabecular bone due to its intricacy and high interconnectivity while maintaining appropriate mechanical properties.4

Advancements in tissue engineering techniques have adopted additive manufacturing methods such as three-dimensional (3D) printing for the fabrication of complex tissue scaffolds.10,11 Three-dimensional printing technologies have enabled the production of scaffolds with customized dimensions using a wide range of materials and geometries.11–14 Most of the material compositions used for 3D printing in bone regeneration applications include polymeric materials alone or in combination with ceramics to impart the scaffolds with osteoconductive signals and mechanical properties similar to those of bone tissue.15–19 However, the amount of ceramic content in the printing formulations was limited due to the lack of printability at concentrations higher than 30–40 w/w% of ceramic in the polymer phase.15

One popular method of additive manufacturing for ceramic scaffolds is selective laser sintering (SLS).20 However, this method incurs some disadvantages, such as the reliance on exacting printing parameters and the need for excessive, potentially cost-prohibitive volumes of material to fill the powder bed. In addition, SLS is limited in its capacity for fabricating pore and material gradients to mimic the physiological intricacies of human trabecular bone tissue more closely due to the laborious process of interchanging powder bed material.21

Alternatively, extrusion-based 3D printing methods can be used to form ceramic powders into predefined 3D structures using a binding component. Postprocessing sintering steps burn out the binder and generate porosity, while allowing ceramic particles to fuse grain boundaries to strengthen the scaffold.22–24 However, the structural shrinkage of the constructs during the sintering process may limit their use in patient-specific applications despite the use of design compensation strategies.25 The shrinkage ratio is mainly dependent on the concentration of ceramics and the sintering temperature.26,27 Previous investigations have attempted to prepare highly concentrated ceramic inks to reduce scaffold shrinkage using water- or oil-based formulations that must usually be printed immediately after preparation to avoid drying or aggregation of the ceramic microparticles.27–29

In this work, we aimed to develop a printable and storable ceramic-based ink for the preparation of sintered scaffolds of HA, β-TCP, and mixtures thereof with mechanical and structural properties similar to those of trabecular bone tissue. The two major advancements illustrated in this study are (1) the preparation of a storable ink with high ceramic content, and (2) the preparation of highly precise and reproducible 3D structures with less than 5% structural shrinkage upon sintering. The structures of the printed and sintered scaffolds were analyzed by means of microcomputed tomography (microCT) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The effect of the sintering process on the architecture of the scaffolds was investigated in terms of pore size, fiber width, and overall porosity. Furthermore, the mechanical properties of the scaffolds were assessed in a compressive mechanical testing apparatus. The storability and printing reproducibility of the developed inks were investigated for 14 days by means of printability under preset conditions. Finally, the dissolution of the scaffolds was characterized for 28 days in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Materials and Methods

Materials

HA (average diameter 25.1 μm) and sintered β-TCP (average diameter 5.3 μm) powders were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). E-Shell® 300, a methacrylate-based photocurable resin consisting of tetrahydrofurfuryl methacrylate, urethane dimethacrylate, and diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide, was acquired from EnvisionTEC (Gladbeck, Germany). All chemicals were used as received.

Ink preparation and scaffold printing

Printable inks were prepared by dispersing the ceramic powders in E-Shell 300. To this end, HA, β-TCP, or 50:50 w/w% β-TCP:HA (hereafter referred to as TCP/HA) powders were placed in a mortar. Thereafter, E-Shell 300 was added to the powder dropwise to obtain a 70:30 w/w% ratio of ceramic to E-Shell 300. The components were then mixed using a pestle until homogeneous slurry was formed. The inks were then loaded in printing cartridges with a 20G needle (inner diameter: 0.60 mm). Next, cylindrical scaffold designs (diameter 10 mm; height 5 mm) were created in SketchUp (Trimble, Sunnyvale, CA) and sliced into 16 layers (0.32 mm slicing thickness) using BioplotterRP software (EnvisionTEC, Gladbeck, Germany). A filling pattern was designated by drawing parallel straight continuous fibers with a 1.4 mm on-center spacing. Each two consecutive layers were designed to have the same orientation to form vertical pores for complete pore interconnectivity within the scaffold. The next two consecutive layers were then printed with the same pattern at a 90° rotated orientation.

Extrusion-based 3D printing was then performed using a 3D-Bioplotter Manufacturer (EnvisionTEC, Gladbeck, Germany). All ceramic ink compositions were printed using a printing pressure of 1 bar, printing speed of 12 mm/s, and needle offset of 0.2 mm. After the extrusion of each layer, an ultraviolet (UV) head was used to cure the deposited ceramic ink for 10 s. The scaffolds used for morphological, structural, mechanical, and dissolution analyses were printed with the abovementioned 3D model design with 16 layers in total, while scaffolds used for the storability studies were also printed with 8 layers in total. After printing, the scaffolds were sintered in a furnace at 1200°C for 6 h. The sintering program consisted of an initial heating to 400°C to remove the organic components, performed at a slow rate of 1°C increase/min to prevent the formation of cracks.30 Then, the samples were heated at 2°C increase/min up to 1200°C, followed by a dwell time of 6 h. Finally, scaffolds were allowed to cool to room temperature.

Characterization of the structure

The crystal structures of the unsintered ceramic powders and sintered ceramic scaffolds were determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) with Cu Ka radiation (40 kV, 40 mA) and analyzed using a D/MAX Ultima II X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan) operated at a step size of 0.02° over the 2θ range of 20–50° at room temperature. Sintered ceramic scaffolds were ground to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle before the analysis. Rietveld refinement was used to calculate the detailed crystal structural information of the ceramic scaffolds after the sintering process, as described previously.31 The Rietveld method uses the crystal structure and diffraction peaks to generate an XRD pattern via a process of least-squares refinement, which minimizes the differences between the observed and calculated patterns. Specifically, Rietveld refinement performed with HighScore Plus 3.0d (PANalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands) was applied in the present work. The background (“Chebyshev I” function), zero drift, absorption, lattice parameters, and atomic coordinates were refined, and the peak shape parameters were set as a modified pseudo-Voigt (PV) function. The refined lattice parameters, phosphate concentrations, and R-values are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The initial models for the refinements were derived from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD)-reported structures (#923, #97500 and #171549 for α-TCP, β-TCP, and HA, respectively).

The mass change of the binder during the burnout process was determined by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (TGA Q50; TA Instruments, New Castle, DE). Briefly, a 20 mg sample crosslinked under the same conditions as in the printing methodology was heated from 22°C to 120°C at a rate of 10°C/min, equilibrated at 120°C for 20 min, and heated to 600°C at 10°C/min. The TGA furnace was purged with argon (75 mL/min) during the heating process and with air during the cooldown.

The functional groups present in the chemical structures of the raw materials (E-Shell 300, HA, and β-TCP) and the scaffolds before and after sintering were determined by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (Nicolette IS50; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) over a wave number range of 400–4000 cm−1 and with a resolution of 0.5 cm−1.

The structure and morphology of the scaffolds before and after the sintering process were assessed by SEM and microCT. For SEM, samples were sputter-coated with gold and imaged at different magnifications using a Quanta 400 ESEM FEG SEM (FEI, Hillsboro, OR). MicroCT analysis was carried out using a SkyScan 1272 X-ray MicroCT (Bruker, Kontich, Belgium) with a pixel resolution of 7 μm and a Cu 0.1+ filter. Images were reconstructed using NRecon software, and 3D renderings were obtained using CTVox software. Analysis of scaffold shrinkage was carried out by comparing the diameter and height of the unsintered and sintered scaffolds with Data Viewer software. Porosity was determined by CTAn analysis software to quantify the volume within the region of interest that was not occupied by radiopaque material (void volume), using a threshold of 21.5 μm, which excluded the micropores from consideration. Pore interconnectivity was assessed by measuring the fraction of void volume accessible from outside of the scaffold through interconnections of at least 21.5 μm diameter between void volumes in adjacent voxels.32

Mechanical characterization

Scaffolds (n = 5; 10 mm in diameter, 5 mm height) were tested using a compressive mechanical testing apparatus (858 MiniBionixII®, MTS, Eden Prairie, MN; 10 kN load cell) and evaluated using the TestStar 790.90 mechanical data analysis package included in the manufacturer's software. Uniaxial compression testing was carried out following the guidelines of the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM).33 The height-to-diameter aspect ratio of the scaffolds was maintained at 1:2, to facilitate uniaxial load application and avoid buckling events.34 The test analyzed the compressive strength and modulus through compression applied perpendicularly to the printing plane with a crosshead speed of 2 mm/min after an initial preload of 25 N. Stress/strain curves were calculated from the load versus displacement data using the initial dimensions of the sample.

Dissolution

The sintered scaffolds (n = 3 per time point) were immersed in 5 mL of PBS (pH 7.4) and incubated at 37°C in an orbital shaker at 110 rpm. Every 2 days, the dissolution buffer solution was removed, its pH level was measured using an Accumet pH/ORP Meter (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and fresh PBS was added to replace the buffer solution. At 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days, scaffolds were removed from PBS, washed with distilled water, and vacuum-dried for 48 h. Dissolution was then calculated as shown in Eq. 1:

| Eq. (1) |

where Mi and Mf represent the initial mass and final mass at each time point, respectively.

MicroCT and XRD analyses as described in Section 2.3 were also performed to investigate the structural and compositional changes of the scaffolds after the 28-day incubation period, respectively.

Ink storability

The printing properties of the composite ceramic inks were monitored for 14 days. Briefly, inks were prepared as explained in Section 2.2 and placed in printing syringes. The ink-filled syringes were placed in the printing heads, and scaffolds (3 replicates per ink, 8 layers high) were printed using the same printing parameters as in Section 2.2. The pore size, fiber width, and porosity of the printed scaffolds were evaluated by microCT to analyze the effect of ink storage on the overall structure of the constructs.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's multiple comparison post-test were used to investigate the effect of printing, storage and sintering on the shrinkage, pore size, fiber width, and porosity of the scaffolds and the pH monitoring. Two-way ANOVA was performed with post hoc analysis Tukey's multiple comparison to evaluate the mass loss in the degradation media. Differences were considered significant for p < 0.05.

Results

Morphology of the printed and sintered scaffolds

In this work, we developed a storable ceramic-based ink for the printing of porous scaffolds with high ceramic content using a commercial 3D printer. The viscosity of the slurry was optimized for printing by varying the ceramic-to-polymeric binder ratio to allow for extrusion using a 20G needle. The accuracy and reproducibility of the printing were tested by printing cylindrical 3D porous scaffolds with a diameter of 10 mm and a height of 5 mm (Fig. 1). The porosity of the scaffolds was achieved by depositing fibers with a 1.4 mm on-center spacing, leading to the formation of open horizontal pores with an approximate size of 800 μm. The printing of two consecutive layers in the same orientation allowed for the formation of vertical pores with an approximate size of 600 μm height, ensuring the complete interconnectivity of the pores of the scaffold.

FIG. 1.

Top-view optical images (left column), and top-view (middle column) and cross-sectional (right column) microCT images of HA (A–C), β-TCP (D–F), and TCP/HA (G–I) ceramic scaffolds after printing (unsintered). The images demonstrated the reproducibility of the printing of scaffolds composed of 16 layers. The microCT analysis also showed the horizontal porosity achieved by changing the orientation of the fibers by 90° at every second layer. Scale bars = 2 mm (left column) or 1 mm (middle and right columns). β-TCP, β-tricalcium phosphate; HA, hydroxyapatite; microCT, microcomputed tomography.

The microscopic analysis of the ceramic scaffolds after the sintering process at 1200°C was used to characterize the superficial morphology of the constructs (Figs. 2 and 3). The micrographs showed the uniform horizontal pore size and fiber width in all printed scaffolds, with horizontal macropores of ∼800 μm size, in accordance with the designed macropore structure. The high-magnification SEM micrographs showed the different morphologies of the ceramic particles after the sintering process. HA scaffolds presented a structure with well-sintered particles and homogeneous microporosity, and β-TCP scaffolds showed particles interconnected by necks suggesting a partial melting of the ceramic during the sintering process. The analysis of the surface of TCP/HA scaffolds confirmed the presence of two particle populations corresponding to the sintered HA and, similarly to the β-TCP scaffolds, the partial melting of the β-TCP particles during the sintering process was also revealed. The SEM images also revealed the presence of microporosity in the structure of the scaffolds, with open micropores in the 5–10 μm range (Fig. 2A–C). The open micropores were evenly distributed throughout the structure regardless of scaffold composition.

FIG. 2.

SEM micrographs highlighting the surface structure of HA (A, D), β-TCP (B, E), and TCP/HA (C, F) scaffolds after sintering at 1200°C for 6 h. Scale bars = 30 μm (A–C) or 300 μm (D–F). SEM, scanning electron microscopy.

FIG. 3.

Top-view images of HA (A), β-TCP (B), and TCP/HA (C), scaffolds sintered at 1200°C, with images obtained from microCT reconstructions. Scale bars = 1 mm.

The overall volumes, fiber widths, and pore sizes of the HA, β-TCP, and TCP/HA scaffolds were measured before and after sintering using the microCT scans to evaluate the effect of the sintering process on the dimensions of the scaffolds (Fig. 4A–C). The resulting analysis showed that for all scaffolds, independent of composition, the constructs possessed a similar structure, including fiber width and pore size. Furthermore, the dimensions of the scaffolds after sintering decreased by less than 5% for all compositions in both horizontal (4.8% ± 1.3% for HA, 4.3% ± 0.7% for β-TCP, and 4.0% ± 1.4% for TCP/HA scaffolds) and vertical (4.8% ± 1.4%, 4.2% ± 1.6%, and 1.7% ± 0.7% for HA, β-TCP, and TCP/HA, respectively) axes, thus maintaining the structural parameters of the design with high fidelity (Fig. 4D). Despite the limitations of scanning resolution, ceramic particles can be seen after sintering, probably due to the densification that occurred during the sintering process at high temperatures.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of fiber width (A), pore size (B), and porosity (C) of the ceramic scaffolds before and after sintering at 1200°C for 6 h, as evaluated by microCT. The value for each composition is represented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5 samples). Fiber width and pore size results represent 5 scaffolds with 50 measurements per scaffold. No significant differences (n.s.) were found in the fiber width, pore size, or porosity of the scaffolds before and after sintering among scaffolds of different compositions. (D) Shrinkage percentage of the ceramic scaffolds after sintering at 1200°C for 6 h compared with the unsintered scaffolds. The value of height shrinkage percentage for TCP/HA is significantly lower (*) compared with HA (p < 0.05) as signified by the asterisk; otherwise, the shrinkage percentages for each composition do not display significant differences.

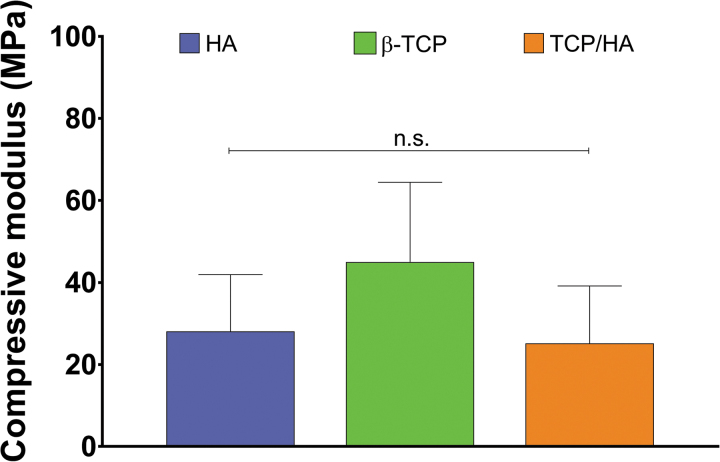

Compressive mechanical testing results showed the mechanical strength of the ceramic scaffolds (n = 5; Fig. 5). The compressive moduli of the HA (28.0 ± 13.8 MPa) and TCP/HA (25.1 ± 14.0 MPa) scaffolds, and β-TCP scaffolds (44.9 ± 19.4 MPa) were statistically similar.

FIG. 5.

Compressive modulus of ceramic-sintered scaffolds. No statistically significant differences (n.s.) were found among the compressive moduli of the HA, β-TCP, and TCP/HA scaffolds. Data reported as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5 scaffolds).

Analysis of composition

XRD was used to characterize the crystal structure of the HA, β-TCP, and TCP/HA scaffolds before and after sintering. Figure 6A shows the XRD diffractogram of the raw powders and scaffolds sintered at 1200°C. The raw HA, β-TCP, and TCP/HA mixture powders showed peak intensities matching the ICSD patterns for each component. Similarly, sintered β-TCP scaffolds showed peak intensities according to the powder diffraction pattern of the β-TCP ICSD card, suggesting that the sintering process did not alter the crystal structure of the scaffold composition. In contrast, the diffractogram of sintered HA scaffolds showed the presence of peak intensities corresponding to the composition of α-TCP. Indeed, the Rietveld refinement of the acquired diffractogram (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Fig. S1) revealed the transformation of ∼34% of the HA into α-TCP. Similarly, the TCP/HA-sintered scaffolds showed the presence of α-TCP peaks in the powder diffraction pattern. The Rietveld refinement indicated that the phase composition of the TCP/HA samples included ∼73% of β-TCP, 12% of α-TCP, and 15% of HA. The low values for R expected (Rexp), R predicted (Rp), and R weighted profile (Rwp) confirmed the successful and reliably performed refinements. Also, the generated goodness-of-fit values obtained were adequate for each composition.

FIG. 6.

(A) Represents the X-ray diffractograms of HA, β-TCP, and TCP/HA powders and scaffolds sintered at 1200°C for 6 h. (B) Shows the FTIR spectra of the E-Shell® 300 and HA and β-TCP scaffolds before and after sintering. FTIR, Fourier-transform infrared.

Table 1.

Results of the Rietveld Refinement Analysis for the Quantification of the Phase Composition of HA-, β-TCP-, and TCP/HA-Sintered Scaffolds, Including Relevant Fit Parameters Rexp, Rp, Rwp, GOF

| Sample | Composition |

Results of Rietveld refinement |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-TCP (wt%) | β-TCP (wt%) | HA (wt%) | Rexp (%) | Rp (%) | Rwp (%) | GOF | α-TCP (wt%) | β-TCP (wt%) | HA (wt%) | |

| HA | 0 | 0 | 100 | 12.95 | 14.88 | 20.87 | 2.59 | 34.0 | 0 | 66.0 |

| TCP/HA | 0 | 50 | 50 | 13.94 | 7.22 | 9.68 | 0.48 | 11.9 | 73.3 | 14.8 |

| β-TCP | 0 | 100 | 0 | 9.06 | 9.35 | 12.6 | 1.95 | 0.5 | 98.8 | 0.7 |

GOF, goodness of fit; TCP, tricalcium phosphate; HA, hydroxyapatite.

The mass loss of the binder during the burnout segment of the sintering process was evaluated using TGA to elucidate the presence of binder in the samples after sintering. The results showed that the onset of thermal degradation of the binder began at ∼280°C and was completed at 480°C, at which point all of the binder present in the scaffold was eliminated (remaining mass <1%, Supplementary Fig. S2).

FTIR analysis was used to evaluate the chemical composition of the scaffolds before and after sintering at 1200°C (Fig. 6B). The main chemical groups of the binder, including C–H stretching peak (2952 cm−1) and C–O stretching peak (1720 cm−1), were not present in the samples after sintering. The representative sharp peaks of the O–H bending mode (630 cm−1) and the double degenerate bending vibration of PO43− in HA (602 and 563 cm−1) were found in the HA samples before and after sintering.35 In the β-TCP samples, 604 and 544 cm−1 sharp peaks were observed, corresponding to the vibrational modes of PO43− in β-TCP.36 An incipient signal was observed in the 1720–1740 cm−1 range of the β-TCP-sintered scaffold that may be attributed to a contamination of the sample. Carbonyl groups, and specifically those present in methacrylate polymers, decompose at temperatures under 560°C, values considerably lower than the sintering temperature used in this work.37,38

Storability studies

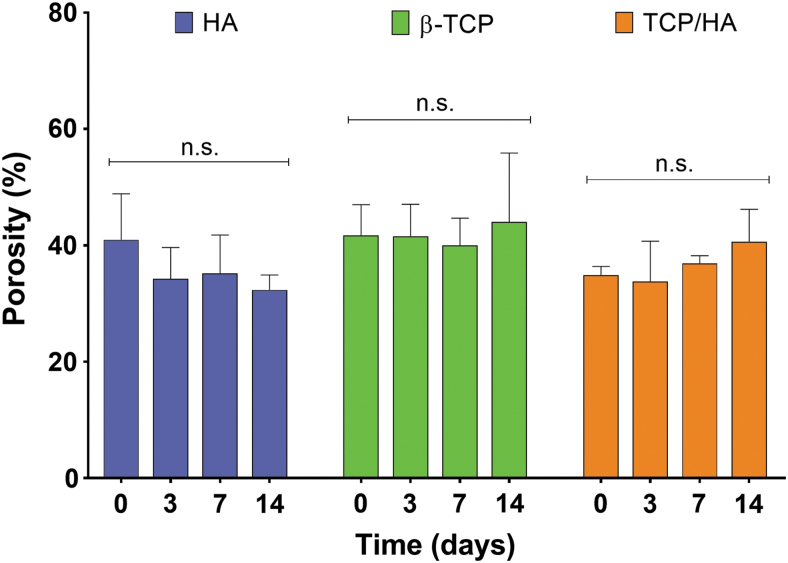

The storability of the ceramic inks was evaluated by tracking the changes in printing conditions for up to 14 days. The printing parameters set for the printing of scaffolds immediately after preparing the inks were still suitable to obtain scaffolds with similar structures after 14 days of ink storage. MicroCT reconstructions of the scaffolds printed at 0, 3, 7, and 14 days after ink preparation revealed that, using the same printing parameters, the structure and pattern of the obtained scaffolds were not significantly altered (Fig. 7). Porosity measurements of the scaffolds revealed that printing of the inks using the same printing conditions throughout the 14-day period led to scaffolds with similar porosities (p > 0.05), as shown in the microCT analysis (Fig. 8).

FIG. 7.

Top-view and side-view images of unsintered HA, β-TCP, and TCP/HA scaffolds prepared using the same printing conditions for each composition after 0, 3, 7, and 14 days after ink preparation. Results showed that the storage of the ink for up to 14 days does not affect the printability and, therefore, allows for similar structure and morphology of the resulting scaffolds. Scale bar = 1 mm.

FIG. 8.

Porosity of unsintered HA, β-TCP, and TCP/HA scaffolds printed 0, 3, 7, and 14 days after ink preparation. Porosity was evaluated from microCT scans of the scaffolds after printing (n = 5; results expressed as mean ± standard deviation). Results showed that the porosity of the scaffolds printed using the same printing parameters for each condition was not significantly affected (n.s.) by the storage of the ink for up to 14 days.

Dissolution studies

The dissolution of sintered scaffolds immersed in PBS at 37°C was monitored for up to 28 days (Fig. 9A). At this last time point, β-TCP scaffolds lost their structural integrity and were fragmented in multiple pieces, whose masses were summed for this final measurement, and the dissolution study was discontinued upon this observation. The scaffold mass was not found to be significantly different after incubation in the PBS solution for 28 days, for which the β-TCP scaffold mass differed from the other two compositions (p < 0.05) but was similar to previous β-TCP time points (p > 0.05). The pH values of the dissolution buffer solution were also monitored throughout the dissolution course (Fig. 9B). The pH of the buffer solution for HA and TCP/HA scaffolds decreased during the first days of incubation from 7.4 to 6.90 ± 0.03 and 6.99 ± 0.02, respectively. In contrast, the pH of the incubation medium for β-TCP scaffolds increased to 7.59 ± 0.02 after scaffold immersion. However, within 21 days, all compositions stabilized at pH 7.36 ± 0.02 and no statistical differences were found for the remainder of the study (p > 0.05).

FIG. 9.

Dissolution of sintered HA, β-TCP, and TCP/HA scaffolds described through (A) remaining mass percentage over 28 days, showing stable mass retention and (B) pH changes over time, showing a slight increase in pH for β-TCP-containing scaffolds and then remaining constant around pH 7.4 values. Error bars indicate mean ± standard deviation for n = 3. Shared letters (and n.s.) indicate no significant difference between groups (n = 3; p > 0.05).

The structure of the scaffolds after 28 days of incubation in PBS was evaluated using microCT (Fig. 10). These results showed that the HA and TCP/HA scaffolds maintained a homogeneous macroscopic structure similar to that of the scaffolds before incubation. However, the 28-day incubation substantially affected the structural integrity of β-TCP scaffolds, and microCT scanning was performed on the largest recoverable fragment remaining within the dissolution buffer. Although no appreciable mass loss was measured, a breakdown in the structure was evident. Microscopic alterations in the structure of the scaffolds were found in the microCT analysis. The presence of structural defects parallel to the axis of the fibers was identified in the HA scaffolds (Fig. 10A). However, these changes were found throughout the structure of the β-TCP scaffolds (Fig. 10B, C).

FIG. 10.

MicroCT of the HA-sintered (A), β-TCP-sintered, not intact due to loss of structural integrity during dissolution (B), and TCP/HA-sintered (C) scaffolds after 28 days in PBS. Images were obtained from the reconstruction of microCT scans of freeze/dried scaffolds. The β-TCP scaffold is partially shown due to the loss of the integrity of the constructs after 28 days of incubation. Scale bar = 1 mm. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

The crystal structure of the scaffolds was evaluated after 28 days of incubation using XRD (Fig. 11). β-TCP scaffolds appeared to have similar phase composition after immersion in PBS. However, HA and TCP/HA scaffolds showed notable dissimilarities in the phase composition after the dissolution study. In contrast to the diffraction patterns obtained for scaffolds containing HA (both HA and TCP/HA scaffolds) after sintering yet before dissolution, the presence of α-TCP peaks was not found in these scaffolds after incubation in PBS.

FIG. 11.

X-ray diffractograms of the scaffolds before and after 28 days of incubation in PBS.

Discussion

Calcium phosphates have been proven to be beneficial for scaffold mineralization and regeneration of bone tissue.7,8 Integrating this material into a scaffold may not only serve to enhance the mechanical properties of an implant but can also encourage bone growth.15,16 Three-dimensional printing of ceramic-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering can allow for the fabrication of scaffolds, which mimic both the porous architecture and material composition of trabecular bone. In this work, we developed a ceramic-based ink with a high concentration of calcium phosphates for the 3D printing of HA- and β-TCP-containing scaffolds with different compositions.

In this study, we focused on trabecular bone due to the challenging requirements of fabricating scaffolds to support this tissue type. While cortical bone presents a simpler structure with very low porosity that may be easily achieved using 3D printing or other fabrication techniques, bone tissue engineering scaffolds intended to facilitate trabecular bone formation require fabrication approaches that enable a precise and highly porous structure to better replicate the complex morphology of trabecular bone.6

The fabrication of HA-, β-TCP-, and TCP/HA-sintered scaffolds occurred by creating a viscous mixture of ceramic particles and a commercially available polymer. The scaffolds were printed, UV crosslinked, and sintered to obtain constructs with mechanical properties similar to trabecular bone tissue and structural properties that closely resemble the initial 3D model, as confirmed by analyzing the fiber width, pore size, and scaffold porosity using microCT and SEM. The printability of the inks enabled the creation of highly interconnected structures. The printing pattern used in this study led to material contours that filled potential pore volume on the sides of the scaffolds; the use of a pattern featuring disconnected parallel strands may be used instead to improve accessibility of the internal pore volume from outside the scaffold. The printability and storability of the ceramic-based inks were demonstrated by performing extrusion-based 3D printing with different ceramic compositions over a period of 2 weeks. As a comparison, previous ceramic inks reported in the literature presented a shelf life in the 0.5–6-h range.27–29 Furthermore, similar porosities obtained for each composition in the structural characterization and the storability studies (p > 0.05) also demonstrated the reproducibility and printing fidelity of the developed inks. The dissolution profile of the sintered scaffolds was studied by immersing the scaffolds in PBS for 28 days and measuring the mass loss and pH changes in the buffer solution.

E-Shell 300 is a photocurable resin mainly used in stereolithography. We used it as a binder to allow for the incorporation of ceramic phase content in the inks up to 70 w/w% without resulting in nonprintable highly viscous slurries. The UV crosslinking step introduced after the extrusion of each layer led to the solidification of the deposited fibers, avoiding collapse during the printing of subsequent layers due to the weight of the structure. Therefore, the fabrication of scaffolds with notable height while maintaining a high printing fidelity and reproducibility was enabled. Furthermore, the UV exposure time (10 s) that leads to the crosslinking and hardening of the material is shorter compared with other postprocessing strategies such as hardening or drying steps that strongly affect the manufacturing time.39 The resulting printed scaffolds also present adequate mechanical properties, thus facilitating handling40 and postprinting processing steps such as sintering.41,42

According to the SEM and microCT analyses, the printed scaffolds showed a high printing fidelity compared with the designed 3D model, including a porosity similar to trabecular bone tissue (20–70%), and significant micropore presence. While scaffolds printed with different compositions displayed some variation in fiber and pore morphologies, these differences were not statistically significant. The similar printability of inks with different compositions used in this study allowed for the preparation of scaffolds with designer structures. Moreover, the deposition of two consecutive layers in the same orientation allowed for the creation of the vertical pores larger than 300 μm, which can enable cell migration throughout the structure of the scaffolds.43

Due to the resolution limits of microCT analysis, only macroporosity (pores larger than the resolution of the scan) could be quantified, resulting in a potential underestimation of total porosity (macro- and microporosity). However, evaluation of the scaffolds' macroporosity can lend insight into the potential for cellular infiltration and osteogenesis after scaffold implantation. A previous study from our group highlighted the effect of pore size and macroporosity on the mechanical properties of implantable scaffolds and the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in vitro.16

The sintering process further eliminated the organic components of the slurries, as shown in the TGA, including any resin and/or photoinitiator that might cause deleterious effects when implanted in vivo.44 Similarly, FTIR analysis confirmed the complete removal of organic compounds from the samples after sintering. The presence of high ceramic concentrations in a scaffold composition is usually reported to lead to the formation of cracks due to the impeded diffusion of the organic vapors through the material.45 While a lower ceramic content would favor the release of the gas products from the incineration of the organic phase, it would markedly increase the shrinkage of the scaffolds.25 Therefore, a slower heating rate of 1°C/min up to 400°C was effectively introduced in the sintering program to minimize any adverse effects of the organic burnout on the structure of the scaffolds. The removal of the organic compounds had no apparent effect on the overall structure of the scaffolds, with no apparent fractures on the surface of the fibers, as shown in the SEM analysis.25,39,46 The SEM analysis of sintered scaffolds revealed partial melting of the β-TCP particles during the sintering process. However, the resulting scaffolds possessed a compressive modulus similar to that of the sintered HA scaffolds.

Moreover, the crystal structure of the sintered scaffolds was detected by XRD. Previous studies have indicated that α-TCP crystals can be generated from the HA scaffolds during the sintering treatment at temperatures above 1200°C due to polymorphic transformation.47–50 It has been reported previously that the presence of α-TCP phase in ceramic scaffolds obtained by sintering processes can lead to the formation of microcracks in the scaffold structure, which can result in a significant decrease in the mechanical properties of the constructs.47 However, the compressive moduli of the scaffolds in the present study (20–70 MPa range) were significantly higher than the previously reported ceramic scaffolds with similar porosities.39 The obtained results for all of the compositions were in the lower range of the compressive modulus for trabecular bone tissue.14

One of the main disadvantages of the use of sintering in tissue engineering applications is potential volumetric shrinkage due to sintering and removal of the binder at high temperatures.51,52 Due to the marked reduction in size compared with the designed 3D-printed models, the regeneration process may fail due to structural mismatching.53 The prediction of shrinkage due to sintering has been attempted before using mathematical equations.25,53 However, the unaccounted-for influence of different variables such as sintering temperature and dwell time, ceramic concentration, and scaffold density or porosity leads to inaccurate predictions for actual clinical translation. The analysis of sintered scaffold structures in the present study showed that the linear shrinkage of the structure of the constructs was less than 5% compared with the initial printed scaffolds. Furthermore, no significant effect on the fiber width, pore size, and total porosity of the scaffolds was observed due to the sintering process. Previous works reported the linear relationship between the processing time and sintering temperature on the shrinkage and mechanical properties of ceramic scaffolds. The achievement of mechanical properties suitable for trabecular bone implantation is usually associated with high degrees of shrinkage. Researchers have tried to remedy this by scaling up the 3D model to account for the predicted further shrinkage of the sintered scaffolds, leading to potential inaccuracy and mismatching with the defect site.54 In this study, we hypothesize that the low shrinking ratio and maintenance of printing fidelity during the sintering process were due to the high ceramic content of the scaffolds as well as the chosen sintering conditions.27 This property can be beneficial for the precise and faithful fabrication of personalized implants for bone tissue engineering.

The degradation rates of HA and β-TCP scaffolds have been extensively studied both in vitro and in vivo.55,56 HA dissolution is known to be significantly slower than that of β-TCP. Previous studies showed that differences in the dissolution rate of HA and β-TCP scaffolds in aqueous media can only be observed after prolonged incubation times.57 Moreover, previous works reported the higher resorption rates of β-TCP compared with HA after in vivo implantation.56 The mass loss of HA, β-TCP, and TCP/HA scaffolds was not significantly different after 28 days in PBS when compared with day 0. However, the structural integrity of β-TCP scaffolds was compromised after 28 days of incubation, which impeded the continuation of the dissolution study. While no significant mass loss was detected for scaffolds of this composition, β-TCP is known to exhibit a higher dissolution capacity in aqueous medium than HA,58 and increased local dissolution may have interfered with the interactions between the sintered particles. Analysis of the phase composition of the scaffolds containing HA in their composition (HA and TCP/HA) changed after immersion in PBS. The lack of α-TCP in the structure after this incubation period may be explained by the phase transformation of α-TCP into HA in water.59

As discussed above, the use of ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering can provide a biodegradable structure to withstand the mechanical stress experienced by bone while supporting the attachment and proliferation of relevant cell types for tissue regeneration. While the present work did not explore demonstrations of the scaffolds' biological behavior due to the extensive characterization of these materials' behavior in the literature,58,60,61 future efforts extending this work to biological evaluations will focus on in vitro analysis of cytocompatibility and osteogenic differentiation, and on in vivo studies of bone formation resulting from modulation of pore and material gradients using this approach.

The biofabrication of personalized ceramic scaffolds with a porous structure matching that of the injured tissue remains a challenge. Printable ceramic-based inks are extremely limited, and current manufacturing techniques are overly and unduly complex. The development of an extrusion-printed storable ceramic ink is a significant advantage compared with existing approaches such as SLS, since it requires significantly less sample material and fabrication time, thus decreasing costs and improving scalability. Furthermore, the search for personalized scaffold fabrication strategies relies on the precise reconstruction of the target tissue's geometry and structural attributes within the printed construct. The combination of a concentrated ceramic ink and appropriate sintering conditions enabled the preparation of pure ceramic scaffolds with high-fidelity structural attributes compared with the original 3D model design. These scaffolds also maintained mechanical properties relevant for bone tissue engineering. In summary, the developed ink may establish a new cost-effective tool for the preparation of complex ceramic constructs for applications that require high fidelity and precision.

Conclusion

Calcium phosphates have been proven to be beneficial for scaffold mineralization and regeneration of bone tissue. three-dimensional printing may enable the fabrication of bone tissue engineering scaffolds mimicking the geometry and material composition of bone. In this work, we successfully fabricated ceramic scaffolds with interconnected porous structure. The inks containing 70% HA, β-TCP, or TCP/HA were extruded using the same printing parameters for up to 14 days after preparation. The printed scaffolds were sintered at 1200°C without significantly affecting the structure of the constructs. The low shrinkage (<5%) of the scaffolds after sintering enabled the creation of scaffolds with precise morphology from a 3D model. Specifically, the scaffolds prepared in this study presented pore sizes and mechanical properties relevant for bone tissue engineering. The scaffolds also showed no noticeable degradation in PBS after 28 days. In conclusion, this study exhibits the development of storable and printable ceramic-based inks for the fabrication of HA- and β-TCP-containing scaffolds that could potentially be used for bone tissue engineering in load-bearing applications.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (P41 EB023833). L.D-G. acknowledges Consellería de Cultura, Educación e Ordenación Universitaria for a postdoctoral fellowship (Xunta de Galicia, Spain; ED481B 2017/063). G.L.K. is supported by the Robert and Janice McNair Foundation MD/PhD Student Scholar Program.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Lee P., Tran K., Chang W., et al. Bioactive polymeric scaffolds for osteochondral tissue engineering: in vitro evaluation of the effect of culture media on bone marrow stromal cells. Polym Adv Technol 26, 1476, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bose S., Roy M., and Bandyopadhyay A.. Recent advances in bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Trends Biotechnol 30, 546, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Polo-Corrales L., Latorre-Esteves M., and Ramirez-Vick J.E.. Scaffold design for bone regeneration. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 14, 15, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chocholata P., Kulda V., and Babuska V.. Fabrication of Scaffolds for bone-tissue regeneration. Materials (Basel) 12, 568, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ghassemi T., Shahroodi A., Ebrahimzadeh M.H., Mousavian A., Movaffagh J., and Moradi A.. Current concepts in scaffolding for bone tissue engineering. Arch Bone Jt Surg 6, 90, 2018 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Qu H., Fu H., Han Z., and Sun Y.. Biomaterials for bone tissue engineering scaffolds: a review. RSC Adv 9, 26252, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang B., Caetano G., Vyas C., Blaker J., Diver C., and Bártolo P.. Polymer-ceramic composite scaffolds: the effect of hydroxyapatite and β-tri-calcium phosphate. Materials (Basel) 11, 129, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kattimani V.S., Kondaka S., and Lingamaneni K.P.. Hydroxyapatite-past, present, and future in bone regeneration. Bone Tissue Regen Insights 7, 9, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ma H., Feng C., Chang J., and Wu C.. 3D-printed bioceramic scaffolds: from bone tissue engineering to tumor therapy. Acta Biomater 79, 37, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Popov A., Malferrari S., and Kalaskar D.M.. 3D bioprinting for musculoskeletal applications. J 3D Print Med 1, 191, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sears N., Dhavalikar P., Whitely M., and Cosgriff-Hernandez E.. Fabrication of biomimetic bone grafts with multi-material 3D printing. Biofabrication 9, 11, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bittner S.M., Guo J.L., Melchiorri A., and Mikos A.G.. Three-dimensional printing of multilayered tissue engineering scaffolds. Mater Today 21, 861, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Turnbull G., Clarke J., Picard F., et al. 3D bioactive composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Bioact Mater 3, 278, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jariwala S.H., Lewis G.S., Bushman Z.J., Adair J.H., and Donahue H.J.. 3D printing of personalized artificial bone scaffolds. 3D Print Addit Manuf 2, 56, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bittner S.M., Smith B.T., Diaz-Gomez L., et al. Fabrication and mechanical characterization of 3D printed vertical uniform and gradient scaffolds for bone and osteochondral tissue engineering. Acta Biomater 90, 37, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith B.T., Bittner S.M., Watson E., et al. Multimaterial dual gradient three-dimensional printing for osteogenic differentiation and spatial segregation. Tissue Eng Part A 26, 239, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Di Luca A., Szlazak K., Lorenzo-Moldero I., et al. Influencing chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stromal cells in scaffolds displaying a structural gradient in pore size. Acta Biomater 36, 210, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diaz-Gomez L., Kontoyiannis P.D., Melchiorri A.J., and Mikos A.G.. Three-dimensional printing of tissue engineering scaffolds with horizontal pore and composition gradients. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 25, 411, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Diaz-Gomez L.A., Smith B.T., Kontoyiannis P.D., Bittner S.M., Melchiorri A.J., and Mikos A.G.. Multimaterial segmented fiber printing for gradient tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 25, 12, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chua C.K., Leong K.F., Tan K.H., Wiria F.E., and Cheah C.M.. Development of tissue scaffolds using selective laser sintering of polyvinyl alcohol/hydroxyapatite biocomposite for craniofacial and joint defects. J Mater Sci Mater Med 15, 1113, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chivel Y. New approach to multi-material processing in selective laser melting. Phys Procedia 83, 891, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gao C., Deng Y., Feng P., et al. Current progress in bioactive ceramic scaffolds for bone repair and regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 15, 4714, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feng P., Niu M., Gao C., Peng S., and Shuai C.. A novel two-step sintering for nano-hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Sci Rep 4, 5599, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zeng Y., Yan Y., Yan H., et al. 3D printing of hydroxyapatite scaffolds with good mechanical and biocompatible properties by digital light processing. J Mater Sci 53, 6291, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li X., Yuan Y., Liu L., et al. 3D printing of hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate scaffold with hierarchical porous structure for bone regeneration. Bio Design Manuf 2019, 15, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karimzadeh A., Ayatollahi M.R., Bushroa A.R., and Herliansyah M.K.. Effect of sintering temperature on mechanical and tribological properties of hydroxyapatite measured by nanoindentation and nanoscratch experiments. Ceram Int 40, 9159, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilson C.E., van Blitterswijk C.A., Verbout A.J., Dhert W.J.A., and de Bruijn J.D.. Scaffolds with a standardized macro-architecture fabricated from several calcium phosphate ceramics using an indirect rapid prototyping technique. J Mater Sci Mater Med 22, 97, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Erdal M., Dag S., Jande Y., and Tekin C.M.. Manufacturing of functionally graded porous products by selective laser sintering. Mater Sci Forum 631, 253, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Martínez-Vázquez F.J., Perera F.H., Miranda P., Pajares A., and Guiberteau F.. Improving the compressive strength of bioceramic robocast scaffolds by polymer infiltration. Acta Biomater 6, 4361, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Perera F.H., Martínez-Vázquez F.J., Miranda P., Ortiz A.L., and Pajares A.. Clarifying the effect of sintering conditions on the microstructure and mechanical properties of β-tricalcium phosphate. Ceram Int 36, 1929, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Young R.A. The Rietveld method. International Union of Crystallography Monographs on Crystallography. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moore M.J., Jabbari E., Ritman E.L., et al. Quantitative analysis of interconnectivity of porous biodegradable scaffolds with micro-computed tomography. J Biomed Mater Res 71A, 258, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Standard Test Method for Compressive Properties of Rigid Plastics. ASTM D695–15. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao S., Arnold M., Ma S., et al. Standardizing compression testing for measuring the stiffness of human bone. Bone Joint Res 7, 524, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xidaki D., Agrafioti P., Diomatari D., et al. Synthesis of hydroxyapatite, β-Tricalcium phosphate and biphasic calcium phosphate particles to act as local delivery carriers of curcumin: loading, release and in vitro studies. Materials (Basel) 11, 13, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ferreira M., Brito A., Brazete D., et al. Doping β-TCP as a strategy for enhancing the regenerative potential of composite β-TCP-alkali-free bioactive glass bone graft. Materials (Basel) 12, 4, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gałka P., Kowalonek J., and Kaczmarek H.. Thermogravimetric analysis of thermal stability of poly(methyl methacrylate) films modified with photoinitiators. J Therm Anal Calorim 115, 1387, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stawski D., and Nowak A.. Thermal properties of poly (N, N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate). PLoS One 14, 11, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kumar A., Akkineni A.R., Basu B., and Gelinsky M.. Three-dimensional plotted hydroxyapatite scaffolds with predefined architecture: comparison of stabilization by alginate cross-linking versus sintering. J Biomater Appl 30, 1168, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hokmabad V.R., Davaran S., Ramazani A., and Salehi R.. Design and fabrication of porous biodegradable scaffolds: a strategy for tissue engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 28, 1797, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Farzadi A., Waran V., Solati-Hashjin M., Rahman Z.A.A., Asadi M., and Osman N.A.A.. Effect of layer printing delay on mechanical properties and dimensional accuracy of 3D printed porous prototypes in bone tissue engineering. Ceram Int 41, 8320, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Butscher A., Bohner M., Doebelin N., Hofmann S., and Müller R.. New depowdering-friendly designs for three-dimensional printing of calcium phosphate bone substitutes. Acta Biomater 9, 9149, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bružauskaitė I., Bironaitė D., Bagdonas E., and Bernotienė E.. Scaffolds and cells for tissue regeneration: different scaffold pore sizes—different cell effects. Cytotechnology 68, 355, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pfaffinger M., Mitteramskogler G., Gmeiner R., and Stampfl J.. Thermal debinding of ceramic-filled photopolymers. Mater Sci Forum 825, 75, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lin K., Sheikh R., Romanazzo S., and Roohani I.. 3D printing of bioceramic scaffolds—barriers to the clinical translation: from promise to reality, and future perspectives. Materials (Basel) 12, 2660, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hwa L.C., Rajoo S., Noor A.M., Ahmad N., and Uday M.B.. Recent advances in 3D printing of porous ceramics: a review. Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci 21, 323, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ou S.-F., Chiou S.-Y., and Ou K.-L.. Phase transformation on hydroxyapatite decomposition. Ceram Int 39, 3809, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hung I.-M., Shih W.-J., Hon M.-H., and Wang M.-C.. The properties of sintered calcium phosphate with [Ca]/[P] = 1.50. Int J Mol Sci 13, 13569, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liu H.S., Chin T.S., Lai L.S., et al. Hydroxyapatite synthesized by a simplified hydrothermal method. Ceram Int 23, 19, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kivrak N., and Taş A.C.. Synthesis of calcium hydroxyapatite-tricalcium phosphate (HA-TCP) composite bioceramic powders and their sintering behavior. J Am Ceram Soc 81, 2245, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fierz F.C., Beckmann F., Huser M., et al. The morphology of anisotropic 3D-printed hydroxyapatite scaffolds. Biomaterials 29, 3799, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Du X., Fu S., and Zhu Y.. 3D printing of ceramic-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: an overview. J Mater Chem B 6, 4397, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Roopavath U.K., Malferrari S., Van Haver A., Verstreken F., Rath S.N., and Kalaskar D.M.. Optimization of extrusion based ceramic 3D printing process for complex bony designs. Mater Des 162, 263, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lee G., Carrillo M., McKittrick J., Martin D.G., and Olevsky E.A.. Fabrication of ceramic bone scaffolds by solvent jetting 3D printing and sintering: towards load-bearing applications. Addit Manuf 33, 101107, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lu J., Descamps M., Dejou J., et al. The biodegradation mechanism of calcium phosphate biomaterials in bone. J Biomed Mater Res 63, 408, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sheikh Z., Abdallah M.-N., Hanafi A., Misbahuddin S., Rashid H., and Glogauer M.. Mechanisms of in vivo degradation and resorption of calcium phosphate based biomaterials. Materials (Basel) 8, 7913, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Houmard M., Fu Q., Genet M., Saiz E., and Tomsia A.P.. On the structural, mechanical, and biodegradation properties of HA/β-TCP robocast scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater 101, 1233, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bouler J.M., Pilet P., Gauthier O., and Verron E.. Biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics for bone reconstruction: a review of biological response. Acta Biomater 53, 1, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lodoso-Torrecilla I., Grosfeld E., Marra A., et al. Multimodal porogen platforms for calcium phosphate cement degradation. J Biomed Mater Res Part A 107, 1713, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhao N., Wang Y., Qin L., Guo Z., and Li D.. Effect of composition and macropore percentage on mechanical and in vitro cell proliferation and differentiation properties of 3D printed HA/β-TCP scaffolds. RSC Adv 7, 43186, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rh. Owen G., Dard M., and Larjava H.. Hydoxyapatite/beta-tricalcium phosphate biphasic ceramics as regenerative material for the repair of complex bone defects. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater 106, 2493, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.