Abstract

T cell receptor (TCR)-based therapeutic cells and agents have emerged as a new class of effective cancer therapies. These therapies work on cells that express intracellular cancer-associated proteins by targeting peptides displayed on major histocompatibility complex receptors. However, cross-reactivities of these agents to off-target cells and tissues have resulted in serious, sometimes fatal, adverse events. We have developed a high throughput genetic platform (termed “PresentER”) that encodes MHC-I peptide minigenes for functional immunological assays and determines the reactivities of TCR-like therapeutic agents against large libraries of MHC-I ligands. In this report, we demonstrated that PresentER could be used to identify the on-and-off targets of T cells and TCR mimic antibodies using in vitro co-culture assays or binding assays. We found dozens of MHC-I ligands that were cross-reactive with two TCR mimic antibodies and two native TCRs and that were not easily predictable by other methods.

Introduction

T cell receptor (TCR)-based therapeutic cells and agents—including adoptive T cells and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)[1], [2], TCR-engineered T cells[3], ImmTACs[4], TCR mimic antibodies[5], and neoantigen vaccines[6], [7]—are cancer therapeutics that target cells expressing intracellular cancer-associated proteins. These agents rely on presentation of peptides derived from cellular, viral or phagocytosed proteins on major histocompatibility complex (MHC), also known as human leukocyte antigen (HLA). However, cross-reactivities of these agents with off-target cells and tissues are difficult to predict and have resulted in serious, sometimes fatal, adverse events[8], [9]. In addition, identifying the antigenic targets of TILs found in tumors is time-consuming, expensive, and complicated[2].

TCR based therapeutics are structurally similar to the TCR on CD8 T cells and thus share both their potential advantages and challenges. For instance, CD8 T cells can theoretically discern whether any MHC-I bound peptide is self, foreign or altered-self. Yet, the number of possible MHC-I ligands that can be encoded by the twenty proteinogenic amino acids is significantly larger than the number of circulating T cells in the human body. In order to account for this discrepancy, TCRs are cross-reactive: most reports suggest that TCRs can recognize hundreds to thousands of distinct pMHC[10]-[14]. Thymic selection in vivo is critical to deplete auto-reactive T cells. Some TCR-based therapeutics are made completely in vitro (e.g., phage display) and thus do not undergo negative selection for the human pMHC repertoire. Other TCR-based therapeutics are isolated from humans but subsequently modified to make them higher affinity, thus potentially introducing new cross-reactivities. As a consequence, each of these agents can be cross-reactive with HLA presented peptides found in normal tissue[15]. A prominent example is an affinity-enhanced TCR directed against an HLA-A*01:01 MAGE-A3 peptide (168-176; EVDPIGHLY), which induced lethal cardiotoxicity in two patients treated with these T cells during a phase I clinical trial. Extensive preclinical testing failed to uncover off-target reactivity; it was later discovered that an epitope derived from Titin (24337-24345; ESDPIVAQY), a structural protein highly expressed by cardiomyocytes, was cross-reactive with the MAGE-A3 TCR[8]. Another TCR directed towards the MAGE-A3 peptide (112-120: KVAELVHFL) led to neuronal toxicity and death in several patients, likely due to cross-reactivity of the TCR to a peptide from the MAGE-A12 protein (112-120: KMAELVHFL)[9]. Hence, a major challenge to the development of safe TCR based therapeutics is the prospective identification of off-tumor, off-target pMHC[16].

Identifying off-tumor, off-target pMHC is challenging because the complete repertoire of HLA ligands found in normal human tissue is unknown. The number of known HLA ligands in humans is rapidly expanding, with reports identifying thousands of novel presented peptides[17], [18]. However, it is unclear how many presented peptides are not known and little is known about the antigens presented on critical tissues such as the nerves, eyes, heart and lungs. Furthemore, cross-reactive pMHC are not easy to identify. Methods to identify cross-reactive targets of TCR-like molecules have been developed by testing yeast[11], [19] or insect-baculovirus[20] cells against soluble TCRs or by staining T cells with libraries of pMHC-tetramers[21], [22]. These approaches are highly valuable, but each has caveats, including time-consuming bacterial purification/refolding of soluble TCRs or expensive synthesis of MHC tetramers. Finally, these methods do not test the most important aspect of T cell therapy: killing of a target cell.

Here, we have developed a mammalian minigene-based method (termed “PresentER”) of encoding libraries of MHC-I peptides. A PresentER minigene encodes a single peptide that is translated directly into the endoplasmic reticulum using a signal sequence. PresentER encoded peptides bypass the endogenous protein processing steps that produce MHC-I peptides from full-length proteins. For the purpose of identifying the targets of T cells, the approach described herein is superior to heterologous expression of full-length cDNA as it avoids the unpredictable effects of peptide processing (including proteasome cleavage, transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) and N-terminal trimming by aminopeptidases). PresentER encoded peptides are non-covalently bound to MHC, as occurs in real cells—as opposed to using a flexible linker covalently tethered to an engineered MHC molecule.

PresentER encoded MHC-I peptides could be used in biochemical and live-cell cytotoxicity assays to sensitively and specifically identify the on-target and off-target ligands of soluble TCR multimers, TCR mimic (TCRm) antibodies, and engineered T cell receptors expressed on lymphocytes. PresentER expressing cells could also be used in immunologic assays such as T cell activation, cytotoxicity, and tumor rejection in naïve, wild-type mice[23]. Using PresentER in pooled library screens, we were able to rapidly discover dozens of peptide ligands of two soluble TCR mimic antibodies, and two engineered-TCR T cells, from among thousands of potential epitopes. For each of the 4 TCR agents studied in this manuscript, multiple cross-reactive peptides were identified, including some which were presented on human cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and Animal Experiments

The T2, HEK293T Phoenix-AMPHO and JY B lymphoblastoid cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CRL-1992; ATCC CRL-3213; ATCC 77441) in 2016. The RMA/S cell line was a generous gift from Dr. Andrea Schietinger in 2016. The TPC1 cell line was a gift from Dr. James Fagin in 2016. GP2-293 packaging cell line were purchased from ClonTech (cat #631458) in 2017. These cell lines were not re-authenticated. T2 cells were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. RMA/S were cultured in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2mmol/L L-glutamine. TPC1 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and 2mmol/L L-glutamine. Cultured cells were regularly tested for mycoplasma. C57BL6/N mice were purchased from Envigo (Envigo:44) and used at 6-24 weeks old. OT-1 mice were purchased from Jackson laboratories (C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J; Jackson 003831) and used at 6-24 weeks old. Experiments involving animals were conducted with the approval of an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at MSKCC (Protocol #96-11-044).

Cloning the PresentER Cassette

The Mouse Stem Cell Virus vector named “MLP” was a generous gift from Dr. Scott Lowe. The 98 amino acid ENV_MMTVC signal peptide from Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus envelope protein (accession #Q85646; Supplemental Table S1) was found in the Signal Peptide Database (http://www.signalpeptide.de/index.php). A DNA construct referred to as the PresentER Cassette was designed as follows: DNA encoding the ENV_MMTVC signal peptide was codon optimized using the Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) Codon Optimization Tool and an SfiI restriction site was added near the 3’-end of the DNA encoding the signal peptide. In doing so, two amino acids were modified: …PQTSLTLFLALL[S>A]VL[G>A]PPPVSG (Supplemental Table S1). A 223nt filler sequence was encoded downstream of this sequence and followed by a second SfiI site. Double stranded DNA encoding the modified signal peptide and filler sequence was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). The DNA was digested with XhoI (NEB cat #R0146) and EcoRI (NEB cat #R3101) and ligated into the XhoI/EcoRI digested MLP vector using T4 DNA ligase (NEB cat #M0202). The PresentER cassette vector and map are available on Addgene (cat #102942).

Cloning individual PresentER constructs

DNA primers encoding individual PresentER minigene antigens were ordered from IDT in the following format: 5’-GGCCGTATTGGCCCCGCCACCTGTGAGCGGG[…]TAAGGCCAAACAGGCC-3’, amplified with PresentER-F and PresentER-R primers (Supplemental Table S1), digested with SfiI (NEB cat #R0123) and purified with the Qiagen MinElute kit (cat #28004). The PresentER Cassette was digested with SfiI, treated with Calf Intestinal Phosphatase (NEB cat #M0290) and purified by agarose gel electrophoresis. The amplicons were ligated into the digested PresentER backbone with T4 ligase and transformed into NEB Stable cells. The PresentER cassette and several example PresentER minigenes are available on Addgene (cat #102946, #102945, #102944, #102943, #102942, #102947). Supplemental Table S4 has a list of PresentER constructs used in this manuscript.

Cloning the PresentER Libraries

Pools of oligonucleotides were synthesized by CustomArray, Inc in the following format: 5’-GGCCGTATTGGCCCCGCCACCTGTGAGCGGG…[24-30nt insert]…TAAGGCCAAACAGGCC-3’. The oligonucleotides were cloned into the PresentER vector in the same way as the individual minigene. After ligation, the ligation products were electroporated into ElectroMAX DH10B cells (Invitrogen #18290015) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Electroporated cells were plated onto four 15cm2 ampicillin plates. Serial dilutions of electroporated cells were plated onto 10cm2 plates to determine the transformation efficiency and number of unique transformed cells. After overnight growth, the colonies were scraped off the plate and grown for 3.5h in Terrific Broth (Sigma-Aldrich cat #T0198) supplemented with 1μg/ml ampicillin at 37°C at 225rpm and plasmid DNA was prepared with the Qiagen MaxiPrep kit (Qiagen cat #12162). Library representation was checked by Illumina sequencing.

Production of retrovirus and library transduced cells

HEK293T Phoenix amphoteric cells were transfected with polyethylenimine (PEI) and the PresentER plasmid (15μg DNA : 45μg PEI) in 10cm2 tissue culture treated plates. Virus was harvested every 12 hours, pooled, concentrated with Clontech Retro-X (Takara Cat #631456). frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C. T2 cells were spinoculated with virus in non-TC treated 6-well plates at 32°C x 2,000xg for 2 hours in complete media supplemented with 4μg/ml of polybrene. RMA-S cells were spinoculated with virus in non-TC treated 6-well plates at 32°C x 1,000xg for 2 hours in complete media supplemented with 4μg/ml of polybrene. Cell media was completely exchanged 12-24h after transduction. Library retrovirus was produced in the same way, except that virus production was scaled up to four 15cm2 plates. The volume of viral supernatant that led to 1/3 maximal transduction efficiency was established for each batch of virus produced by transduction of target cells with serial dilutions of viral supernatant. Transduced cells were selected with 1μg/ml (T2) or 4μg/ml (RMA/S) of puromycin for 2-3 days.

Bioinformatic identification of possible ESK1 and Pr20 off-targets

The peptides included in the PresentER library were found in Uniprot TrEMBL database of reviewed and unreviewed human protein sequences. Substrings of unique 9 and 10 amino acid sequences were collected and affinity to HLA-A*02:01 was calculated using NetMHCPan. All human peptides with predicted HLA-A*02:01 IC50 less than 500nM were compared to the ESK1 and Pr20 cross-reactivity motifs to determine which should be included in the library. All potentially cross-reactive ESK1 ligands and half of the potential Pr20 ligands were included in the library.

Flow cytometry, fluorescence activated cell sorting, antibodies and commercial reagents

Purified ESK1 and Pr20 monoclonal antibodies were provided by Eureka Therapeutics and fluorescently labeled using Innova Biosciences lightning link kits (705-0010) following the manufacturers instructions. The TCR multimer specific to NLVPMVATV (CMV aa495-503)/HLA-A*02:01 was purchased from Altor BioScience (Cat #TCR-CR1-0020). APC labeled antibodies specific to SIINFEKL/H2-Kb (Clone 25-D1.16) were purchased from Ebioscience (Cat #141606). Each labeled antibody or TCR multimer was titered by flow cytometry on antigen-positive and antigen-negative cells. Briefly, cells were stained with decreasing concentrations of antibody and the concentration with optimal signal:background ratio was identified. Cells were stained as follows: Cells were washed twice with ice cold PBS and then incubated for 30 minutes on ice with fluorescently labeled antibody in staining buffer (PBS supplemented with 2% FCS, 0.1% sodium azide and 5mM EDTA). Following staining, cells were washed twice with ice cold staining buffer and resuspended in staining buffer with DAPI. Fluorescence data was collected on LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences) or Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) instruments. Data was analyzed on FlowJo v10.

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) was performed to isolate ESK1 and Pr20 bound T2 cells. T2 cells transduced with library virus were stained with ESK1-APC or Pr20-APC as described above. ESK1 or Pr20 positive and negative cells were sorted on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) instrument. Sorting gates were set-up based on the fluorescence intensity of stained single-minigene control cells (RMF and ALY). Each sort was performed two times for each antibody. Sorted cells were collected and genomic DNA was purified as described below.

Genomic DNA Extraction and Library Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from bulk or sorted cells with the Gentra Puregene kit (Qiagen #158689) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic DNA was amplified with Q5 Polymerase (NEB #M0491) directly using P5Primer and P7BarcodePrimer or with nested PCR (outer primers P5 and MMTV_SP2_R; inner primers PresentER_Short_F and PresentER_Short_R) (Supplemental Table S1). Amplicons were quantitated with PicoGreen and quality control performed by Agilent TapeStation. Sequencing libraries were prepared from amplicons using the KAPA HTP Library Preparation Kit (Kapa Biosystems KK8234) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with 8 cycles of PCR. Barcoded libraries were pooled equimolarly and run on a HiSeq 4000 in a 50bp/50bp paired end run, using the HiSeq 3000/4000 SBS Kit (Illumina).

Screen validation by peptide pulsing

Spot synthesized crude peptides (PepTrack libraries) were ordered from JPT Peptide Technologies for validation of screen hits. Peptides were resuspended in DMSO to 20mg/ml and then diluted to 1mg/ml with PBS. Peptides were pulsed onto T2 cells by supplementing the media of T2 cells with 20-50μg/ml of each peptide. Pulsed cells were stained via flow cytometry as described above with ESK1 or Pr20 to evaluate binding of antibody to pMHC.

Evaluation of ESK1 binding to JY and TPC1

JY and TPC1 cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, blocked with 1:10 human FcR Block (Miltenyi Biotec cat #130-059-901) and stained with unlabeled ESK1 or IgG1 isotype control in staining buffer (Eureka Therapeutics Cat #ET901) for 30m on ice. Cells were washed with staining buffer and labeled with anti-human IgG1 APC antibody (BioLegend Cat #HP6017). Cells were washed twice more in staining buffer and evaluated by flow cytometry.

Generation of AviTagged A6 TCR and A6 tetramers

The A6 and B7 TCRs (Supplemental Table S2) were a generous gift from Dr. Brian Baker. The A6 beta chain plasmid was modified to encode a C-terminal AviTag biotinylation site (GLNDIFEAQKIEWHE). Gibson cloning was used to insert the AviTag site with the following two primers: F: 5’-gcagaaaattgaatggcatgaaTAAGCTTGAATTCCGATCCGG-3’ R: 5’-gcttcaaaaatatcgttcaggccGTCTGCTCTACCCCAGGC-3’. Both the alpha and beta chains were expressed in BL21 (DE3) bacteria (ThermoFisher Scientific cat #C606010) and induced with 1mM IPTG (Sigma-Aldrich cat #16758). The A6 beta chain was co-transfected with a plasmid encoding the BirA enzyme (Addgene #26624) and bacteria were grown with supplemental biotin (0.5mM D-Biotin). Inclusion bodies were harvested and the individual chains were purified and re-folded together according to previously described protocols[24], [25].

Generation of A6 and B7 TCR mammalian expression plasmids

In order to generate full-length mammalian TCR sequences, we used Gibson assembly (NEB cat #E2611) to clone the A6 and B7 alpha/beta chains (Supplemental Table S2) into the pMSGV1 vector backbone.

Isolation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear cells

Written consent to IRB protocol #06-107, conducted according to the common rule, was obtained from four donors over the age of 18 and meeting the inclusion criteria of “healthy participant with no current malignancies.” Blood was collected by venipuncture into heparinized tubes. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by differential density centrifugation using Lymphocyte Separation Medium (Corning Catalog #25072CI) within 24 hours.

Generation of T cells with transgenic TCRs

Plasmids encoding the DMF5 and 1G4 TCRs (Supplemental Table S3) were provided as a kind gift from Dr. Steven A. Rosenberg. TCR retroviral transduction was performed as described previously[26]. Briefly, retroviral particles were generated by transient transfection of the retroviral packaging cell line 293GP cells with the pMSGV1-TCR plasmids and pRD114 plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). Retroviral supernatant was harvested 2 days later and used to transduce PBMCs were stimulated with soluble 50 ng/ml anti-CD3 (clone OKT3, Miltenyi Biotec cat #130-093-387) and 300 IU/ml rhIL-2 (R&D Systems) for 2 days prior to retroviral transduction. Retroviral transductions were performed on Retronectin (Takara) coated non-tissue culture treated 24-wells plates by spinoculation of the retrovirus at 2,000× g, 32°C for 2 hours, followed by addition of activated T cells to the retrovirus containing plates. After overnight incubation at 37°C, T cells were transferred to a tissue-culture treated 24-well plate and expanded in human T cell media (RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% L-Glut, 300 IU/mL rhIL-2). Transduced T cells were used at 10-15 days post-transduction or cryopreserved until used in assays.

ELISPOT and co-culture killing assays

IFN-gamma release ELISPOTs were performed in 200μl of RPMI supplemented with 5% FBS. 50,000 F5 transduced T cells were incubated at 1:1 effector:target (E:T) ratios with T2 cells expressing PresentER minigenes. Controls included: no targets, wild type T2s, 50μg/ml peptide pulsed T2s and PHA treated cells. Co-culture assays was performed in a similar manner: 50,000 T cells were co-cultured in U-bottom plates with mixtures of 50,000 T2 cells expressing PresentER minigenes in mCherry or GFP flavors. Control wells did not contain T cells. Antigen specific target cell lysis was evaluated by flow cytometry 45 hours after co-culture by comparing the percentage of GFP positive cells to the percentage of mCherry cells in each well.

Co-culture library depletion assays

Mouse RMA/S cells were transduced at low multiplicity of infection (MOI) (<0.3) with a library of 5,000 PresentER minigenes encoding wild type H-2Kb peptides (NetMHCPan v4.0 predicted ic50 < 500nM) selected randomly from the mouse proteome (UniProt database UP000000589 of canonical mouse protein sequences) together with several control minigenes encoding known H-2Kb antigens (e.g., chicken ovalbumin SIINFEKL). Transduced cells were selected with puromycin as described above. Spleens from OT-1 or C57B6 mice were removed aseptically, grinded against a 100μm filter, washed with PBS and then cultured in mouse T cell media (RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS + 1% HEPES + 1% sodium pyruvate + 1% HEPES + 1% L-glutamine + 50μM 2-mercaptoethanol + 200 IU/ml hlL2). Splenocytes were activated by adding 1μg/ml anti-CD3e (clone 145-2C11; BD cat #553058) and 1μg/ml anti-CD28 (clone 37.51; BD cat #553295) to the media. RMA/S expressing library minigenes were co-cultured with activated OT-1 or activated C57B6 splenocytes for 4 days in 96-well round bottom plates. To prevent media exhaustion and avoid well-specific effects, all wells were pooled together daily, fresh media was added and cells were re-dispersed onto new 96-well plates. After 96 hours, the cells were removed from the plate, genomic DNA was extracted and minigenes were quantified by Illumina sequencing as described above.

The human T2 library depletion assays were performed in a similar fashion. T2 cells were transduced with minigene libraries encoding HLA-A*02.1 peptides. Library expressing cells were co-cultured with A6, B7, DMF5 or 1G4 T cells for 4 days. Cells were pooled together daily, media was added as needed and cells were re-dispersed onto the plates to prevent media exhaustion and avoid well-specific effects. Finally, cells were harvested, genomic DNA was extracted and minigenes were quantified by Illumina sequencing as above.

Immunopurification of HLA class I ligands

Affinity columns were prepared as follows: 40 mg of Cyanogen bromide-activated-Sepharose® 4B (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# C9142) was activated with 1mM hydrochloric acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# 320331) for 30 min. Subsequently, 0.5 mg of W6/32 antibody (BioXCell, BE0079; RRID: AB_1107730) was coupled to sepharose in the presence of binding buffer (150mM sodium chloride, 50 mM sodium bicarbonate, pH 8.3; sodium chloride: Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# S9888, sodium bicarbonate: Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#S6014) for at least 2 hours at room temperature. Sepharose was blocked for 1 h with glycine (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# 410225). Columns were equilibrated with PBS for 10 min.

T2 cells expressing PresentER constructs were washed three times in ice-cold sterile PBS. Afterwards, cells were lysed in 7.5 ml 1% CHAPS (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# C3023) in PBS, supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche cOmplete, Cat# 11836145001) for 1 hour at 4°C. Cell lysate was centrifuged at 20,000xg for 1 hour at 4°C. Supernatant was passed over column through peristaltic pumps at 1 ml/min flow rate overnight at 4°C. Affinity columns were washed with PBS for 30 min, water for 30 min, then run dry, and HLA complexes subsequently eluted five times with 200 μl 1% trifluoracetic acid (TFA, Sigma/Aldrich, Cat# 02031). For separation of HLA ligands from their HLA complexes, tC18 columns (Sep-Pak tC18 1 cc Vac Cartridge, 50 mg Sorbent per Cartridge, 37-55 μm Particle Size, Waters, Cat# WAT036820) were prewashed with 80% acetonitrile (ACN, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# 34998) in 0.1% TFA and equilibrated with two washes of 0.1% TFA. Samples were loaded, washed again with 0.1% TFA and eluted in 400 μl 30% ACN in 0.1%TFA. Sample volume was reduced by vacuum centrifugation for mass spectrometry analysis.

LC-MS/MS analysis of HLA ligands

Samples were analyzed by high resolution/high accuracy LC-MS/MS (Lumos Fusion, Thermo Fisher). Peptides were desalted and concentrated prior to being separated using direct loading onto a packed-in-emitter C18 column (75um ID/12cm, 3 μm particles, Nikkyo Technos Co., Ltd. Japan). The gradient was delivered at 300nl/min increasing linear from 2% Buffer B (0.1% formic acid in 80% acetonitrile) / 98% Buffer A (0.1% formic acid) to 30% Buffer B / 70% Buffer A, over 70 minutes. MS and MS/MS were operated at resolutions of 60,000 and 30,000, respectively. Only charge states 1, 2 and 3 were allowed. 1.6 Th was chosen as isolation window and collision energy was set at 30%. For MS/MS, maximum injection time was 100ms with an AGC of 50,000.

Mass spectrometry data processing

Mass spectrometry data was processed using Byonic software (version 2.7.84, Protein Metrics, Palo Alto, CA). Mass accuracy for MS1 was set to 6 ppm and to 20 ppm for MS2, respectively. Digestion specificity was defined as unspecific and only precursors with charges 1, 2, and 3 and up to 2 kDa were allowed. Protein FDR was disabled to allow complete assessment of potential peptide identifications. Oxidization of methionine was set as variable modifications for all samples. All samples were searched against UniProt Human Reviewed Database (20,349 entries, http://www.uniprot.org, downloaded June 2017). Peptides were selected with a minimal log prob value of 2 resulting in a 1% false discovery rate. For visualization of mass spectrometry results skyline software (version 3.1, MacCoss Lab Software) was used. Masses of precursors and product ions of peptide target sequences were searched in all relevant .raw files and peak areas of all replicates compared.

Enrichment/depletion analysis

After Illumina sequencing of each sample, reads were mapped to the appropriate PresentER minigene library with Bowtie2. Reads that did not map to the minigenes in the library were discarded. For each sample, the number of reads mapping to each minigene was divided by the total number of reads that mapped to the library. Minigenes with frequencies less than 1/50,000-100,000 reads in untreated or unsorted samples were excluded from further analyses. In order to identify minigenes enriched in the screen, we normalized the frequency of each minigene in the sorted/treated samples by the frequency of each minigene in the unsorted/untreated samples. For experiments with T cell co-cultures, the frequency of each minigene was compared between treatment groups (e.g. A6 co-cultured libraries vs. 1G4 co-cultured libraries). The A6 and B7 enrichment/depletion scores were calculated by dividing the frequency of minigenes in the library after co-culture with A6 or B7 divided by the frequency of minigenes in the library prior to co-culture. For the ESK1/Pr20 enrichment/depletion scores, the frequency of each minigene in the sorted “antibody high” sample was divided by the minigene frequency in the “antibody low” sample.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed in Prism v7 and in the R programming language. Statistical tests are described in the figure legends and include two-tailed t-tests with a significance cutoff of p ≤ 0.05. Receiver operating curves were generated using the R package “plotROC.” {Sachs:2017hx}

Results

PresentER yielded functional MHC-I ligands for biochemical and functional immunological assays

We designed a minigene (“PresentER”) that is capable of generating precisely defined MHC-I antigens in mammalian cells. DNA encoding the MHC-I peptide is short (72-78nt) and inexpensive to synthesize individually or as a pool (Figure 1A and Fig. S1). The peptide is encoded downstream of a signal sequence, thus bypassing the typical processing for MHC-I peptide presentation: proteasomal cleavage, peptide transport into the endoplasmic reticulum and aminopeptidase trimming[27]. The peptide is translated directly into the endoplasmic reticulum, where it binds to MHC and is exported to the surface of the cell. PresentER was designed for pooled screening applications; therefore, the amino acid sequence corresponding to an MHC presented peptide is encoded by DNA only once per minigene and can be sequenced in its entirety in one 50bp sequencing read. In order to demonstrate that PresentER minigenes recapitulated all of the expected characteristics of MHC-I presented antigens, we relied on several fluorescently labeled monoclonal antibodies, multimerized TCRs and engineered T cells. All TCR and TCR-like agents used as reporters of cell surface MHC-I are described in Table 1.

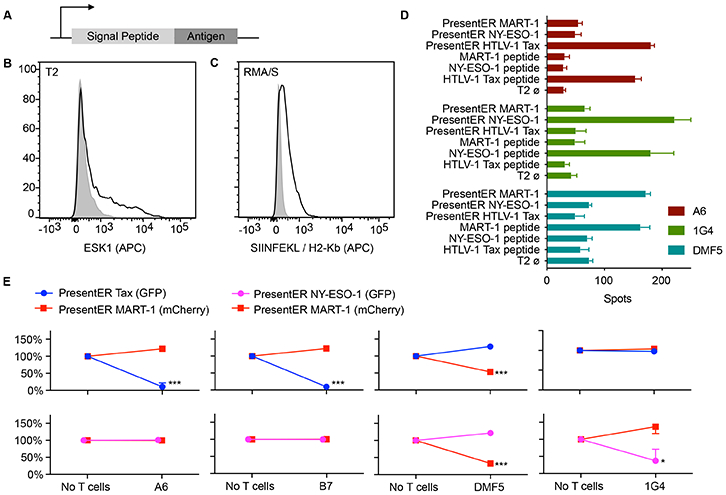

Fig. 1: Design and characterization of PresentER minigene.

(A) The PresentER minigene encodes an ER signal sequence, followed by a peptide antigen and a stop codon. (B) T2 cells expressing PresentER-RMFPNAPYL (black) but not PresentER-ALYVDSLFFL (gray) bind ESK1, a TCR mimic antibody to the complex of RMFPNAPYL/HLA-A*02:01. (C) An antibody to SIINFEKL/H-2Kb binds to RMA/S cells expressing PresentER-SIINFEKL (black), but not to PresentER-MSIIFFLPL (gray). (D) ELISpot of genetically engineered T cells expressing the A6 (target: HTLV-1 Tax:11-19 LLFGYPVYV), DMF5 (target: MART-1:27-35 AAGIGILTV) or 1G4 (target: NY-ESO-1:157-165 SLLMWITQC) TCRs challenged with peptide-pulsed T2 cells or T2 cells expressing PresentER minigenes (3 replicates per condition). Error bars indicate SEM. (E) Results of in vitro co-culture killing assays where A6, B7, DMF5 and 1G4 expressing T cells were incubated with a mixture of T2 cells expressing PresentER-Tax (GFP)/PresentER MART-1 (mCherry), PresentER NY-ESO-1 (GFP)/PresentER MART-1 (mCherry). The change in abundance of the T2 target cells are plotted relative to their abundance in the “No T cells” sample. Each point is the average of 3 replicates. Error bars indicate SEM. Two-tailed t-tests comparing the abundance of each target at the beginning and end of the experiment are designated as *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤0.001.

Table 1:

The target of each TCR and TCR-like agent used in this article.

| Peptide | MHC Allele | Origin | Binds to |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMFPNAPYL | HLA-A2.1 | Human WT1 126-134 | ESK1 (TCR mimic antibody) |

| ALYVDSLFFL | HLA-A2.1 | Human PRAME 300-309 | Pr20 (TCR mimic antibody) |

| SIINFEKL | H-2Kb | Chicken Ovalbumin 257-264 | OT-1 (TCR) 25-D1.16 (TCR mimic antibody) |

| NLVPMVATV | HLA-A2.1 | CMV pp65 495-503 | Altor Biosciences TCR-CR1 |

| LLFGYPVYV | HLA-A2.1 | HTLV-1 Tax 11-19 | A6 (TCR) B7 (TCR) |

| AAGIGILTV | HLA-A2.1 | Human MART-1 27-35 | DMF5 (TCR) |

| SLLMWITQC | HLA-A2.1 | Human NY-ESO-1 157-165 | 1G4 (TCR) |

We have previously isolated and characterized two TCR mimic (TCRm) antibodies that recognize HLA-A*02:01 presented peptides derived from genes aberrantly expressed on cancer cells. ESK1[5] binds to the Wilms tumor (WT1) peptide RMFPNAPYL (WT1:126-134) and Pr20[28] binds to the preferentially expressed antigen of melanoma (PRAME) peptide ALYVDSLFFL (PRAME:300-309). T2 cell lines expressing a PresentER-encoded peptides were bound by ESK1 and Pr20 only when expressing their cognate antigens, but not irrelevant peptides (Fig. 1B and Fig. S2A-D). In order to show that TCR could bind to the minigene-derived MHC-I peptides, we stained PresentER antigen expressing T2 cells with HLA-A*02:01 peptide specific TCR multimers: (1) TCR-CR1 which recognizes NLVPMVATV (Cytomegalovirus pp65:495-503) and (2) A6 which recognizes LLFGYPVYV (HTLV-1 Tax:11-19)[29]. These TCR multimers specifically bound T2 cells expressing their cognate ligand (Fig. S2E-H).

PresentER encoded minigenes could also lead to presentation of peptides on non-human MHC molecules: an antibody against mouse H-2Kb/SIINFEKL bound the Tap2 deficient mouse RMA/S[30] cells expressing PresentER SIINFEKL (Chicken Ovalbumin 257-264) but not cells expressing PresentER MSIIFFLPL (PEDF:271–279) (Fig. 1C). Cell lines with wild-type Tap function could present PresentER driven antigens, as shown by the expression of PresentER-SIINFEKL in EL4 cells (Fig. S3).

We immunoprecipitated peptide-MHC complexes from T2 cells expressing PresentER-RMFPNAPYL or PresentER-ALYVDSLFFL and identified bound peptides by mass spectrometry. RMFPNAPYL and ALYVDSLFFL were identified only in cells encoding those PresentER constructs (Fig. S4A-B). No peptides derived from the ER signal sequence were identified.

In order to confirm that signal sequence mediated delivery of the antigen to the endoplasmic reticulum was the mechanism of MHC-I peptide presentation, we generated minigene constructs with scrambled ER signal sequences. The scrambled signal sequences will not lead to peptide translocation to the ER and thus should abrogate TCRm binding. These minigenes were generated by shuffling the amino acids of the (N-terminal) signal sequence but not the (C-terminal) peptide antigen sequence. In T2 cells expressing two different scrambled signal sequences coupled to peptide antigens ALYVDSLFFL or RMFPNAPYL, we found no binding of ESK1 or Pr20 (Fig. S4C).

Pooled screens using retroviral methods must be “single-copy competent,” meaning that a single DNA copy of the minigene must suffice to yield the desired effect in a cell. If more than one copy is required, the pooled screen will fail because few cells will receive more than one copy of the same minigene[31]. In order to demonstrate that PresentER minigenes were single copy-competent, we infected mouse H-2Kb RMA/S cells with decreasing titers of virus carrying PresentER SIINFEKL (i.e., decreasing multiplicities of infection) and then assayed for SIINFEKL/H-2Kb presentation on the surface of the cell using the 25-D1.16 antibody. SIINFEKL peptides were still found on the surface of the cell after 1,000-fold viral dilution and resultant 15-fold decrease in infection rate (<1% of cells infected). This demonstrated that the PresentER minigene was capable of driving antigen presentation from a single copy of the retroviral minigene, thereby enabling its use in a pooled screen (Fig. S5).

We next tested if PresentER encoded MHC-I antigens could be used in functional T cell assays. In addition to the A6 TCR described above, other genetically engineered T cells to known antigens are described in the literature, including DMF5[3], [32] (specific to MART-1:27-35 HLA-A*02:01/AAGIGILTV), 1G4[33] (specific to NY-ESO-1:157-165 HLA-A*02:01/SLLMWITQC) and B7 (same specificity as the A6 TCR). We transduced T cells from non-HLA-A*02:01 donors with constructs encoding the DMF5, 1G4 or A6 TCRs and then co-cultured these cells with peptide-pulsed or PresentER minigene expressing T2 cells. The T cells released similar amounts of IFNg when exposed to minigene or peptide pulsed cells, demonstrating that PresentER minigenes yield pMHC at levels sufficient to lead to T cell recognition (Fig. 1D).

In order to confirm that engineered T cells could specifically kill T2 cells expressing their cognate antigen, we cloned several PresentER minigenes into a PresentER vector encoding mCherry instead of GFP. Then, we mixed T2 cells expressing peptide A/GFP with T2 cells expressing peptide B/mCherry. For instance, T2 cells expressing PresentER Tax (GFP) were mixed with T2 cells expressing PresentER MART-1 (mCherry). These mixtures were then co-cultured with T cells specific to one of the antigens, or with T cells specific to an irrelevant antigen. After 45 hours, flow cytometry was used to evaluate the percentage of live cells expressing each fluorophore. T cells killed T2 cells expressing their cognate antigens, but not T2 cells expressing an irrelevant antigen (Fig. 1E). This experiment confirmed that T cells selectively eliminated T2 cells expressing their PresentER encoded cognate antigen.

PresentER minigene libraries could be used to discover the MHC-I peptide targets of T cells

To test if PresentER libraries could be used to distinguish MHC-I targets of T cells from irrelevant targets at large scale, we used T cells from OT-1 mice, which express only H-2Kb/SIINFEKL specific TCRs, and T cells from B6 mice, which are poly-specific. Activated splenocytes from OT-1 and B6 mice were co-cultured with RMA/S cells expressing a library of 5,000 randomly selected wild-type H-2Kb peptides as well as several control peptides, including SIINFEKL. The abundance of each minigene after co-culture was assayed by Illumina sequencing. A schematic of the experiment is presented in Fig. 2A. Cells expressing the peptide target of the OT-1 TCR—SIINFEKL—were depleted by more than 1-log while no other minigenes were depleted (Fig. 2B).

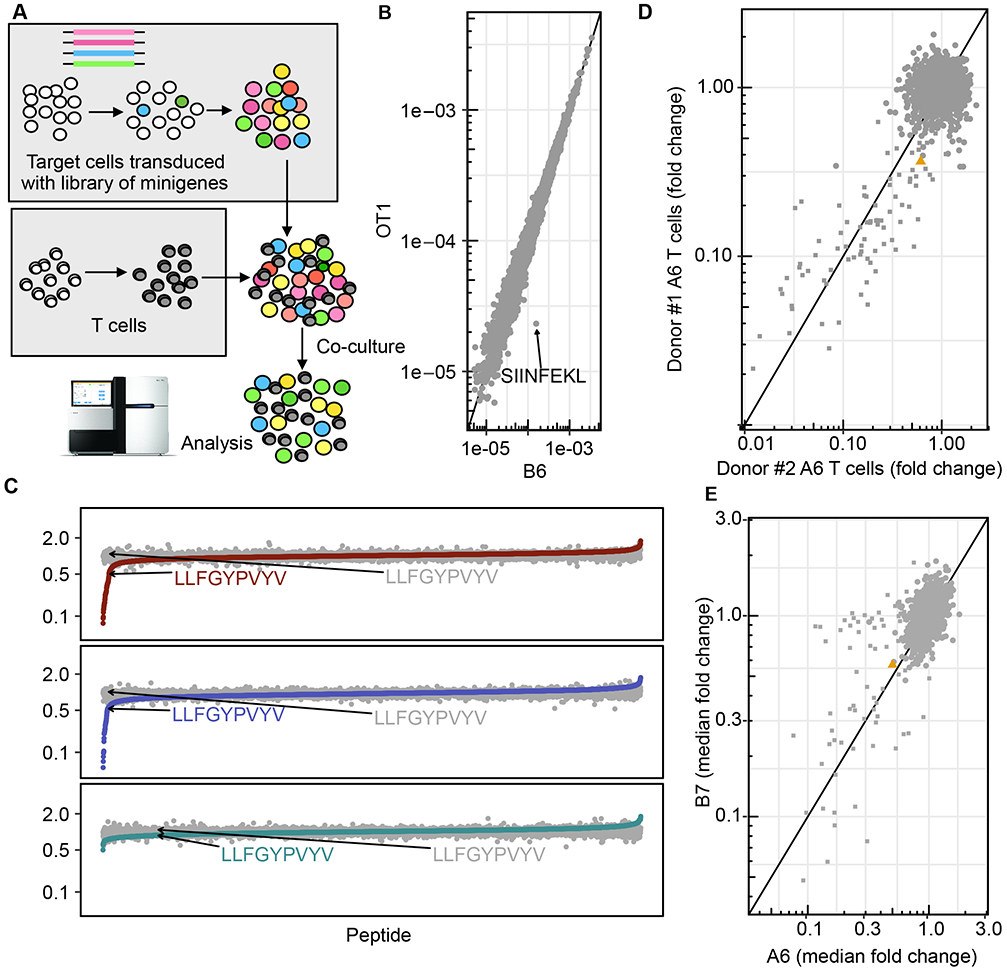

Fig 2: PresentER could be used to discover the peptide targets of T cell receptors.

(A) A schematic depicting how cells expressing a library of minigenes were generated and subsequently co-cultured with native or engineered T cells. (B) The abundance of each H-2Kb antigen minigene encoded by mouse RMA/S target cells after co-culture with activated OT-1 (y-axis) or B6 splenocytes (x-axis). Each point is the median of two biological replicates. (C) The median fold change in abundance of each peptide minigene in the library after co-culture with human T cells expressing the A6 (top), B7 (middle) or DMF5 (bottom) TCR, sorted on median fold change. LLFGYPVYV, the target of A6 and B7, is indicated. Each point is the median fold change across independent replicates (1G4: 4 replicates, DMF5: 2 replicates, A6: 4 replicates, B7: 3 replicates) (D) The median fold change in abundance of each peptide minigene in the A6/B7 library after co-culture with human T cells from two different donors expressing the A6 TCR. Each point is a single experiment/replicate. € The median fold change in abundance of each peptide minigene in the A6/B7 library after co-culture with A6 (x-axis; 4 replicates) or B7 (y-axis; 3 replicates) expressing T cells.

Next, we tested the ability of the PresentER method to discover the targets and off targets of two human TCRs. The A6 and B7 TCR were isolated from a patient with HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) and were found to recognize an HLA-A*02:01 peptide derived from the HTLV-1 virus Tax protein. The A6 TCR in complex with its target was the first human TCR structure to be solved and the biochemical characteristics of both A6 and B7 have been extensively explored[24], [25], [34]. The position-specific binding specificities for the A6 and B7 TCR are mapped by cytotoxicity studies using peptide-pulsed target cells[35]. These features made the A6 and B7 TCRs excellent candidates to use in a screen to validate previously known targets and discover additional targets. Using published data, [35] we generated a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) to predict A6 or B7 targets. We scored the human proteome according to the PSSM to find peptides that might be targets of A6 and B7. We selected 5,000 peptides with high predicted affinity to HLA-A*02.1 that were either highly scored for A6, B7 or both. We also included all single amino acid mutants of LLFGYPVYV. We cloned a library of minigenes encoding these peptides and introduced them into T2 cells. T cells from non-HLA-A*02.1 donors were transduced with plasmids encoding the A6, B7, DMF5 or 1G4 TCR and co-cultured with the library of target cells. The abundance of each minigene was quantified by Illumina sequencing before and after co-culture with T cells expressing each TCR. Fifty-two minigenes were depleted by 2-fold or more after co-culture with A6 T cells and 34 minigenes were similarly depleted by co-culture with B7 T cells. No minigenes were depleted by DMF5 or 1G4 (Fig. 2C). To demonstrate the inter-experimental reliability of minigene depletion by T cell coculture, minigene depletion by A6 T cells from two different PBMC donors was compared. The minigenes that were depleted more than 2-fold between the two donors were 90% concordant (Fig. 2D). All the depleted minigenes were single amino acid substitutions of the Tax peptide. As expected based on prior data[35], the A6 TCR was more promiscuous, recognizing almost twice as many peptides as B7 (Fig. 2E).

In order to examine the ability of the PresentER screen to discover peptide targets of A6 and B7, we focused on the minigenes encoding single amino acid variants of the Tax peptide. Many of these peptides were previously tested for A6 and B7 cytotoxicity by Hausmann et al. [35]. A PSSM depicting this is presented in Fig. 3A-B. Many A6 and B7 ligands validated by Hausmann et al. [35] were depleted in our co-culture assays (Fig. 3C-D). We identified substitutions that were not tested by Hausmann et al [35] but were found to be targets of the TCRs; 19 substitutions led to A6 cytotoxicity and 17 substitutions led to B7 toxicity. These included substitutions at the 2nd and 9th position (revealing unusual MHC anchors), substitutions containing cysteines and differences between glutamic acid, and aspartic acid residues in the same positions (Fig. 3E-F).

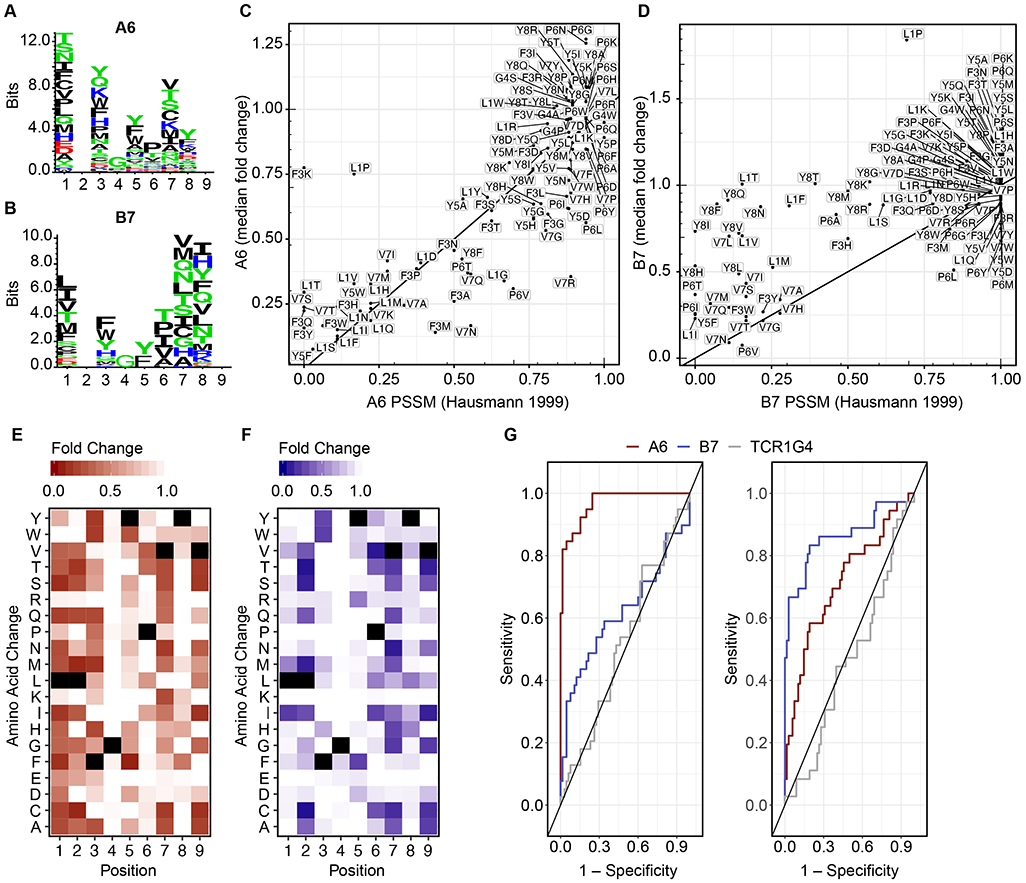

Fig. 3: Previously identified single amino acid variants of the A6 and B7 target peptide were re-identified in the PresentER library screen.

(A-B) Sequence logos showing the PSSM of A6 and B7 derived from Hausmann et al [35]. (C-D) The abundance of each minigene encoding single amino acid mutants of the Tax peptide after co-culture with A6 or B7 (y-axis) in comparison to its PSSM score (x-axis). Each point is the median of four A6 replicates and three B7 replicates (E-F) Heat maps of the single amino acid substituted peptides obtained in the A6 (4 replicates) and B7 (3 replicates) minigene depletion assay experiments, respectively. Black squares indicate the Tax peptide sequence. (G) Receiver operating curves (ROC) show the sensitivity/specificity of the PresentER method using the A6 (left) and B7 (right) TCR experiments.

In order to assess the sensitivity and specificity of a TCR target screening tool such as PresentER, several targets and non-targets must be known for each TCR. For most TCRs, few peptide ligands are known because testing TCR reactivity for a meaningfully large set of synthetic peptides is cost prohibitive. The A6 and B7 TCR are unique in that a large number of peptides have already been tested: 105 out of 133 possible single amino acid mutants of the LLFGYPVYV peptide were tested by Hausmann et al [35] in co-culture killing assays. Using Hausmann’s data as the “ground truth,” we categorized peptides with >25% of maximum killing as “targets” and the rest as “non-targets” and plotted receiver operator curves (ROC) of the PresentER A6 and B7 screens (Fig 3G). The A6 TCR screen was highly sensitive, reaching >90% sensitivity with 85% specificity. The B7 TCR screen was less effective, reaching 70% sensitivity with 85% specificity. 1G4 is plotted for comparison. The sensitivity of PresentER was likely underestimated by this analysis, as the non-physiologic conditions of peptide pulsing in vitro tends to overestimate the T cell activating potential of a peptide

Two peptides that are characterized as weak off targets of the A6 and B7 TCRs in peptide-pulsing assays were also included in the library: S. Cerevisiae Tel1P 549–557 MLWGYLQYV and Human HuD / ELAVL4 87–95 LGYGFVNYI[35]. Neither of these peptides were depleted in the minigene library depletion assays, prompting us to wonder whether these peptides were indeed recognized well by the A6/B7 T cells. We performed an ELISPOT using T2 cells pulsed with peptide or expressing PresentER minigenes. A6 was weakly reactive to the ELAVL4 peptide when pulsing onto T2 cells, but not to ELAVL4 minigene expressing cells. A6 did not react to Tel1p peptide pulsed cells or Tel1p minigene expressing cells. B7 was not reactive to Tel1p or ELAVL4 peptides or PresentER minigenes by ELISPOT (Fig. S6A). T2 co-culture killing assays using minigene expressing peptides were also negative (Fig. S6B). These results suggested that in some cases there may be differences between the peptides that could be pulsed onto cells and peptides that could be presented via a minigene.

PresentER minigene libraries could be used to discover the peptide targets of TCR mimic antibodies

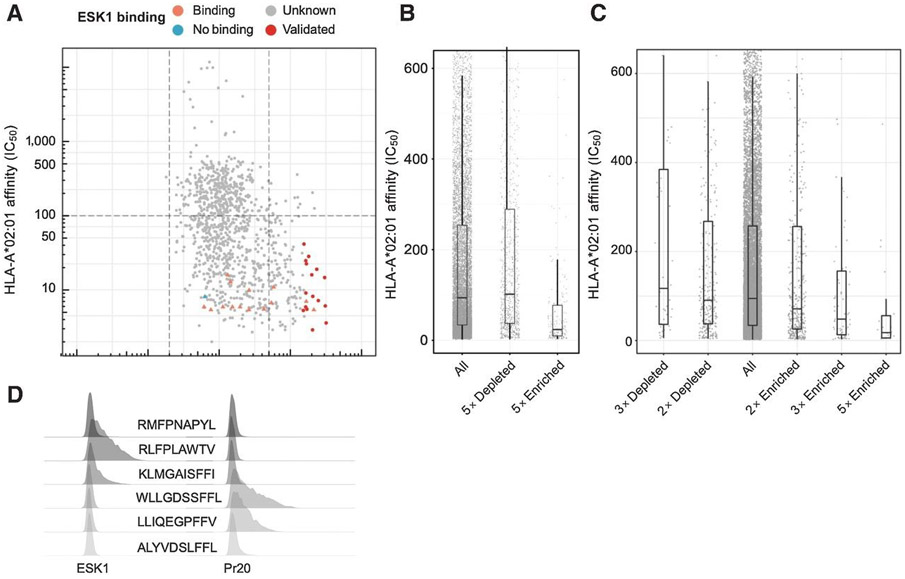

Two anti-cancer antibodies developed by our group—Pr20 and ESK1—have been extensively evaluated in preclinical studies as therapeutic agents. These antibodies were developed using phage display libraries and thus never underwent a thymic-like negative selection process. Therefore, it is unknown whether they might cross-react with peptides presented endogenously on human cells. Based on alanine/residue scanning and structural[36] data, ESK1 binding to RMFPNAPYL depends primarily on the R1 and P4 residues. By contrast, Pr20 binds to the C-terminus of the peptide[28]. Therefore, we constructed a library of possible ESK1 and Pr20 cross-reactive targets by searching the human proteome in silico for 9 and 10-mer peptide sequences matching a motif based on prior biochemical data (Fig. 4A). We located 1,157 and 24,539 potential cross-reactive peptides of ESK1 and Pr20, respectively, with NetMHCPan[37], which predicted HLA-A*02:01 affinity of less than 500nM (Fig 4B). We synthesized a library of 12,472 oligonucleotides that together encoded all of the ESK1 cross reactive peptides, half of the Pr20 cross-reactive targets, the single amino acid mutants of RMF and ALY (termed “CR-ESK1” and “CR-Pr20”, respectively), and positive/negative control peptides (Fig. 4B). Library transduced T2 cells were stained with ESK1 or Pr20, sorted and sequenced. Every minigene was scored for ESK1 and Pr20 enrichment, indicating how frequently it was found in the highly stained cells compared to the poorly stained cells. A schematic of the flow-based screen is presented in Figure 4C.

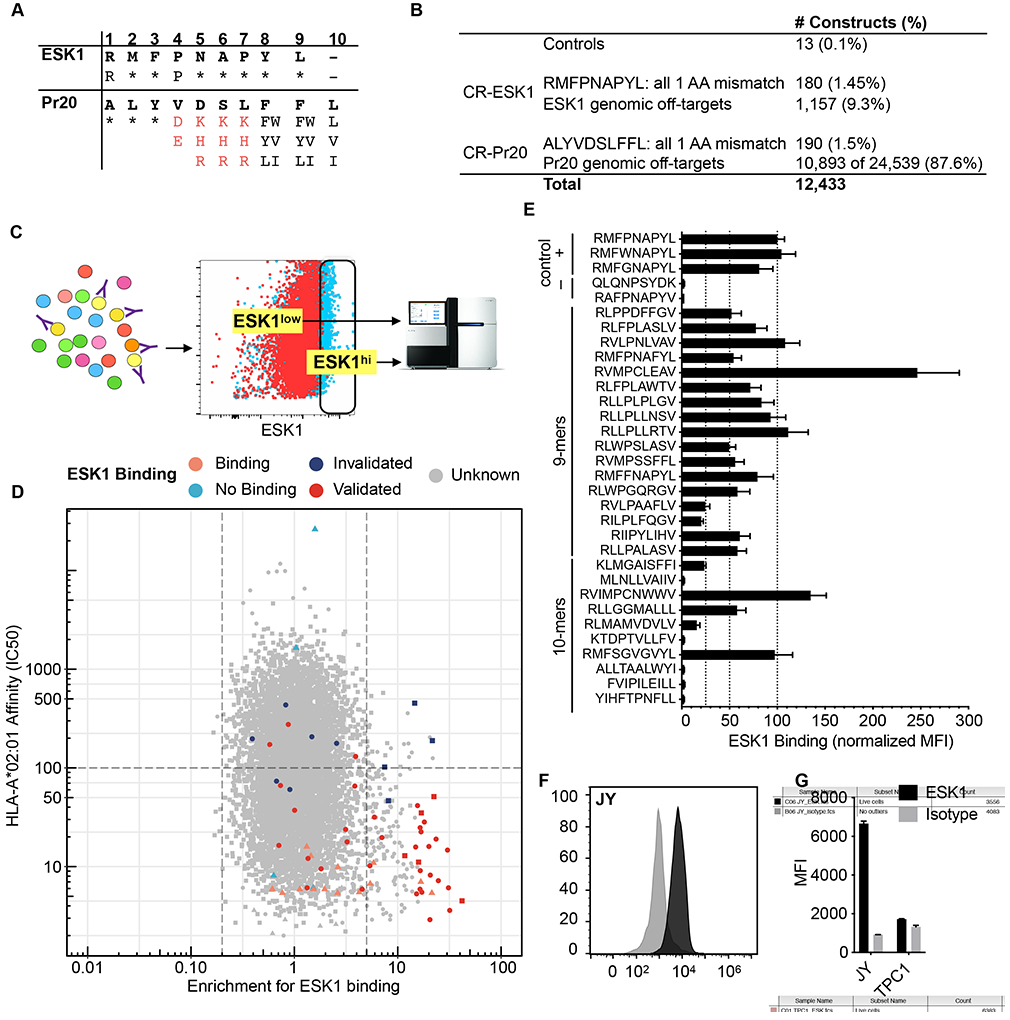

Fig. 4: Discovery of off-targets of the ESK1 TCR mimic antibody.

(A) The motif used to search the human proteome for peptides that might bind to ESK1 and Pr20. Asterisks indicate that any amino acid is allowed. Red characters indicate prohibited amino acids and black characters indicate allowed amino acids at that position. (B) Description of the constructed library. (C) Schematic of the flow-based screen. T2s are transduced at low MOI with retrovirus encoding a pool of PresentER minigenes, selected with puromycin and stained with the TCR mimic antibodies. Fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS) is used to sort antibody binding and non-binding populations for sequencing. (D) Scatterplot of the ESK1 library screen. Each point is a unique peptide minigene plotted as minigene enrichment for ESK1 binding (x-axis; with 1 set as no enrichment; average of two replicates) vs. predicted ic50 (in nM) to HLA-A*02:01 (y-axis). Lower ic50 indicates higher affinity. Control peptides and known ESK1 targets are plotted as triangles; CR-ESK1 as circles and CR-Pr20 as squares. Peptides that validated by peptide pulsing are displayed in dark red. Peptides that did not validate by peptide pulsing are in dark blue. Control ESK1 binders are in orange and control non-binders are in teal. Unknown binding is in gray. (E) 27 peptides that were highly enriched for ESK1 binding and had high predicted affinity to HLA-A*02:01 (from Figure D) were synthesized at microgram scale, pulsed onto T2 cells in triplicate and stained with ESK1. Previously identified cross-reactive targets were included as positive controls. The median fluorescence intensity of ESK1 binding is plotted, normalized to RMFPNAPYL (set at 100 units). Error bars indicate SEM. (F) Representative ESK1 and isotype staining of the JY cell line. (G) Quantification of ESK1 and isotype staining of the JY and TPC1 cell lines in triplicate. Error bars indicate SEM.

First, we wanted to determine if previously known ESK1 ligands were enriched in the sorted cells. Minigenes encoding known ESK1 ligands had higher enrichment scores compared to non-ligands (p=0.032). This suggested that the flow-based screen was able to separate ESK1 binders from non-binders (Fig. S7A). Next, we looked to see which minigenes were enriched in the screen. We found over 100 peptides with ic50 < 500nM which were >5-fold enriched for ESK1 binding. Surprisingly, several of the most enriched peptides that emerged in the ESK1 screen were CR-Pr20 peptides, such as RVIMPCNWWV and RMFSGVGVYL (Fig. 4D). Although these peptides are 10-mers, some bear sequence similarity to the target ligand of ESK1. In order to validate these hits, we synthesized 27 of the enriched peptides, pulsed them onto T2 cells and stained them with ESK1. Of the peptides tested, 22 (81%) showed binding to ESK1, including several which had originally been selected for Pr20 cross-reactivity and did not contain a proline in position 4 (Fig. 4E). These unusual targets could not have been predicted from either the crystal structure of ESK1 or the alanine scanning data.

Next, we wanted to determine if any of the ESK1 targets we had discovered were expressed in a WT1-negative cell line, thus possibly leading to ESK1 binding. Large databases of HLA-A*02:01 peptide ligands isolated from tumors and normal tissue have become available[18], [38]-[40]. Within these databases (including personal correspondence with Department of Immunology members at Tübingen), we found two WT1-negative[41] cell lines that contained ESK1 off-targets discovered in the PresentER screen (TPC-1: RLPPPFPGL, RVMPSSFFL, RLGPVPPGL, JY: KLYNPENIYL, RLVPFLVEL). RMFPNAPYL was not found among the MHC-I ligands immunoprecipitated from these lines. We tested ESK1 binding in each of these lines and found that JY cells bound ESK1 at high intensity, whereas TPC-1 was marginally positive for ESK1 binding (Fig. 4F-G). Thus, PresentER may be used to identify both theoretical and, in some cases, peptides presented on real cells that are bound by ESK1.

A screen of Pr20 cross-reactive ligands was performed in the same manner as described for ESK1. Known Pr20 binders were not enriched relative to the negative controls (p=0.71) (Sup. Fig. 7B). However, twenty peptides were more than 5-fold enriched for Pr20 binding with predicted ic50s of less than 100nM. We synthesized 13 of these peptides, pulsed them onto T2 cells and found that all 13 bound to Pr20 (Sup. Fig. 8).

Peptide-MHC affinity influenced the identified targets of TCR mimic antibodies

Examining only the CR-ESK1 subset of peptides, we noticed that the peptides most enriched for ESK1 binding were also predicted to have the highest affinity for HLA-A*02:01 (Fig. 5A). Peptides that are ≥5-fold enriched for ESK1 binding have a higher affinity for HLA-A*02:01 as compared to the library as a whole and compared to the peptides that were ≥5-fold depleted (median affinity of 31nM, 95nM and 102nM, respectively) (Fig. 5B). We found the same result in the Pr20 screen: the most enriched Pr20 ligands also had the highest affinity to MHC-I. (Fig. 5C). The skew we observed in both ESK1 and Pr20-enriched minigenes towards high-affinity HLA-A*02:01 ligands suggests that minigene expression of peptides selects for presentation of ligands with the highest affinities for HLA-A*02:01. This may be an unexpected feature of PresentER, as affinity to MHC-I is the most important factor in endogenous MHC-I peptide presentation (although high peptide expression levels may overcome low affinity)[17]. We cloned minigenes for four of the most enriched CR-ESK1 (RLFPLAWTV 31.8x; KLMGAISFFI 41.9x) and CR-Pr20 (WLLGDSSFFL 6.5x; LLIQEGPFFV 6.6x) peptides and tested them for binding to ESK1 and Pr20. ESK1 and Pr20 bound cells presenting these peptides at significantly higher amounts than the peptides to which these antibodies were originally isolated (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5: Peptides enriched in TCRm screening were high affinity MHC-I ligands.

(A) Scatterplot of the ESK1 screen with only CR-ESK1 peptides and controls plotted (average of two replicates). Each point is a peptide minigene plotted as enrichment for ESK1 binding (x-axis; 1 is no enrichment) vs. netMHCPan predicted HLA-A*02:01 affinity in ic50 (y-axis; nM). Lower ic50 indicates higher affinity. Control peptides and previously known ESK1 target peptides are plotted as triangles and CR-ESK1 as circles. Validated ESK1 binders are displayed in dark red. (B) The predicted HLA-A*02:01 affinity in IC50 (nM) of all screened peptides compared to peptides which were ≥5-fold depleted or ≥5-fold enriched for ESK1 binding. (C) The predicted HLA-A*02:01 affinity in ic50 (nM) of all screened peptides compared to peptides that were ≥5-fold, ≥3-fold or ≥2-fold enriched in the Pr20 screen and peptides that were ≤3 or ≤2-fold depleted for Pr20 binding. (D) ESK1 and Pr20 staining of T2 cells expressing 6 PresentER minigenes that were highly enriched in the screen.

Discussion

Few methods exist for robust identification of the targets of TILs and the off-targets of TCR-based therapeutic agents and cells. As a consequence, preclinical evaluation of novel therapeutic agents directed towards peptide-MHC are insufficient to prevent harmful off-tumor off-target toxicities, including deaths. A number of approaches can identify the off targets of tumors, but all suffer from key limitations. For instance, animal models of cross-reactivity are not very useful due to species-specific MHC molecules and differences in peptide processing[42]. Yeast/Insect display is highly scalable, but relies on purified and refolded TCRs in vitro, which is not the native format that would be delivered to patients. Screening using MHC tetramers can be effective, but synthesis of large numbers of peptides is expensive. Methods to generate DNA-barcoded tetramers using in vitro transcription and translation are promising and we look forward to future development in this area. However, while these methods are valuable and can elucidate the fundamental biology of TCRs[43], they are poorly suited to preclinical evaluation of novel therapeutics.

PresentER is a mammalian cell-based approach to identify MHC-I ligands of TCR agents at large scale. The PresentER method is a physiologically relevant, scalable method that can be used to identify functional cross-reactivities between MHC-I ligands and TCR agents with excellent sensitivity and specificity. In this report we have demonstrated that it can also be used for immunological assays in vitro while in a separate publication we demonstrated its use in immunological assays in vivo [23].

In this manuscript we used peptide libraries biased towards existing biochemical binding data to study the off targets of T cell receptor like molecules. However, users of the PresentER minigene method could instead generate unbiased libraries. As an example: a library of minigenes including all possible 9-10 amino acid peptides in the human exome that bind to one allele of MHC-I (<1x106) could be constructed for $50,000, compared to the many months to years of work and the millions of dollars needed to do the same with synthesized peptides. This is a trivial sum for the preclinical evaluation of a novel engineered T cell therapeutic compared to the cost of a clinical trial that is halted because of toxicity[8], [9].

We found that some peptides act as TCR/TCRm ligands when pulsed onto T2 cells at supraphysiologic levels, but are not detected when expressed by PresentER minigenes (e.g. A6 and its target ELAVL4). Whether or not these peptides are presented endogenously in any human tissue is unknown. We speculate that some PresentER encoded peptides may never reach the cell surface because they are removed by MHC peptide editors[44] or aminopeptidases. Alternatively, some peptides may be inefficiently loaded onto MHC when they are not transported by Tap or may be unstable once they reach the cell surface. These processes are likely to disproportionately affect peptides with low affinity to MHC. Consequently, the restrictions imposed by cellular machinery may generate more reliable PresentER screening results as compared to peptide pulsing assays. Indeed, we found that peptides with low MHC-I affinity are infrequently off-targets of ESK1 and Pr20 in our screens. However, because of the pooled library approach used here, measurements of affinities and stability are not possible—nor have we been able to identify library peptides by MS/MS, likely because of low absolute abundance. For other applications, the inability to present some low affinity MHC peptides may be undesirable. For instance, some proteins that are highly expressed in human tissues may lead to endogenous peptide presentation despite the low affinity to MHC. Peptides derived from these proteins may not be properly presented when encoded by PresentER minigenes.

Another caveat to our approach is that a large number of target cells are required to ensure library fidelity—at least 1,000 cells per minigene—thus limiting the size of each minigene library to the number of cells that can be manageably cultured. This is solved by splitting large libraries into multiple sub-libraries. Finally, we demonstrated the use of PresentER minigenes for ligands of HLA-A*02:01 and mouse H-2Kb, but not other MHC alleles. In principal, PresentER minigenes should work for any MHC allele because while the peptide binding motifs may differ, the mechanisms of loading and presenting peptides are the same.

Since PresentER screening of TCR relies on T cell co-culture and killing, it may fail to identify pMHC that antagonize TCR function[45]. Moreover, there is even a risk that antagonist peptides found in the library could skew the results by inhibiting T cell activation. However, this is unlikely to be a problem unless the numbers of antagonist peptides in the library is so large as to productively inhibit most of the T cells in the assay.

PresentER can be used for biochemical evaluation of therapeutic TCR based agents such as engineered TCRs and TCR mimic antibodies and discovered dozens of off targets of each. We believe that the minigene method we have described meets an unmet need in the preclinical evaluation of TCR agents. Given that patients have already died as a result of off-tumor off-target toxicity, we propose that off target assessment using libraries of MHC minigenes covering the entire human exome be a routine step in preclinical development of TCR and TCR-like agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Eureka Therapeutics for the ESK1 and Pr20 antibodies; Brian Baker and Lance Hellman for the A6 and B7 TCR plasmids; Yael David for assistance in refolding soluble TCRs; Scott Lowe and Eusebio Manchado Robles for the MSCV backbone and assistance with pooled library cloning; Steven A. Rosenberg for the DMF5 and 1G4 TCR. We thank the Integrated Genomics Operation Core, funded by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG, P30 CA08748), Cycle for Survival, and the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology and the Flow Cytometry core facilities at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for their assistance.

Funding

The project was supported by the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy and the Functional Genomics Initiative at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. RSG is supported by NCI F30 CA200327 and NIGMS T32GM07739. DAS is supported by NCI RO1 CA 55349, P01 CA23766, P30 CA008748. MK is supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant no. KL 3118/1-1. CAK is the recipient of a Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator Award.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest:

MSK has applied for patent protection for the PresentER method, and for the TCRm, on which RSG and DAS, and TD and DAS, respectively, are inventors.

DAS is a consultant for and has equity in Eureka Therapeutics, KLUS, Pfizer, and is on the board of directors of Sellas.

TD is a consultant for Eureka therapeutics.

AYC is currently employed by Pfizer.

CAK Advisory and consulting: Aleta Biotherapeutics, Cell Design Labs, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), Klus Pharma, Obsidian Therapeutics, Rxi Therapeutics.

CAK Honoraria: Kite/Gilead.

CAK Equity holdings: Aleta Biotherapeutics, BMS, Celgene, CVS, Johnson and Johnson,

CAK Clinical Research Support: Kite/Gilead (Inst).

References

- [1].O'Reilly RJ, Dao T, Koehne G, Scheinberg D, and Doubrovina E, “Adoptive transfer of unselected or leukemia-reactive T-cells in the treatment of relapse following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation.,” Semin. Immunol, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 162–172, June 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rosenberg SA and Restifo NP, “Adoptive cell transfer as personalized immunotherapy for human cancer.,” Science, vol. 348, no. 6230, pp. 62–68, April 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Johnson LA, Heemskerk B, Powell DJ, Cohen CJ, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Robbins PF, and Rosenberg SA, “Gene transfer of tumor-reactive TCR confers both high avidity and tumor reactivity to nonreactive peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 177, no. 9, pp. 6548–6559, November 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Oates J, Hassan NJ, and Jakobsen BK, “ImmTACs for targeted cancer therapy: Why, what, how, and which.,” Mol. Immunol, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 67–74, October 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dao T, Yan S, Veomett N, Pankov D, Zhou L, Korontsvit T, Scott A, Whitten J, Maslak P, Casey E, Tan T, Liu H, Zakhaleva V, Curcio M, Doubrovina E, O'Reilly RJ, Liu C, and Scheinberg DA, “Targeting the intracellular WT1 oncogene product with a therapeutic human antibody.,” Sci Transl Med, vol. 5, no. 176, p. 176ra33, March 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sahin U, Derhovanessian E, Miller M, Kloke B-P, Simon P, Löwer M, Bukur V, Tadmor AD, Luxemburger U, Schrörs B, Omokoko T, Vormehr M, Albrecht C, Paruzynski A, Kuhn AN, Buck J, Heesch S, Schreeb KH, Müller F, Ortseifer I, Vogler I, Godehardt E, Attig S, Rae R, Breitkreuz A, Tolliver C, Suchan M, Martic G, Hohberger A, Sorn P, Diekmann J, Ciesla J, Waksmann O, Brück A-K, Witt M, Zillgen M, Rothermel A, Kasemann B, Langer D, Bolte S, Diken M, Kreiter S, Nemecek R, Gebhardt C, Grabbe S, Höller C, Utikal J, Huber C, Loquai C, and Türeci Ö, “Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer,” Nature, vol. 547, no. 7662, pp. 222–226, July 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ott PA, Hu Z, Keskin DB, Shukla SA, Sun J, Bozym DJ, Zhang W, Luoma A, Giobbie-Hurder A, Peter L, Chen C, Olive O, Carter TA, Li S, Lieb DJ, Eisenhaure T, Gjini E, Stevens J, Lane WJ, Javeri I, Nellaiappan K, Salazar AM, Daley H, Seaman M, Buchbinder EI, Yoon CH, Harden M, Lennon N, Gabriel S, Rodig SJ, Barouch DH, Aster JC, Getz G, Wucherpfennig K, Neuberg D, Ritz J, Lander ES, Fritsch EF, Hacohen N, and Wu CJ, “An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma,” Nature, vol. 547, no. 7662, pp. 217–221, July 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cameron BJ, Gerry AB, Dukes J, Harper JV, Kannan V, Bianchi FC, Grand F, Brewer JE, Gupta M, Plesa G, Bossi G, Vuidepot A, Powlesland AS, Legg A, Adams KJ, Bennett AD, Pumphrey NJ, Williams DD, Binder-Scholl G, Kulikovskaya I, Levine BL, Riley JL, Varela-Rohena A, Stadtmauer EA, Rapoport AP, Linette GP, June CH, Hassan NJ, Kalos M, and Jakobsen BK, “Identification of a Titin-derived HLA-A1-presented peptide as a cross-reactive target for engineered MAGE A3-directed T cells.,” Sci Transl Med, vol. 5, no. 197, pp. 197ra103–197ra103, August 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Morgan RA, Chinnasamy N, Abate-Daga D, Gros A, Robbins PF, Zheng Z, Dudley ME, Feldman SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Phan GQ, Hughes MS, Kammula US, Miller AD, Hessman CJ, Stewart AA, Restifo NP, Quezado MM, Alimchandani M, Rosenberg AZ, Nath A, Wang T, Bielekova B, Wuest SC, Akula N, McMahon FJ, Wilde S, Mosetter B, Schendel DJ, Laurencot CM, and Rosenberg SA, “Cancer regression and neurological toxicity following anti-MAGE-A3 TCR gene therapy.,” J. Immunother, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 133–151, February 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ishizuka J, Grebe K, Shenderov E, Peters B, Chen Q, Peng Y, Wang L, Dong T, Pasquetto V, Oseroff C, Sidney J, Hickman H, Cerundolo V, Sette A, Bennink JR, McMichael A, and Yewdell JW, “Quantitating T cell cross-reactivity for unrelated peptide antigens.,” J Immunol, vol. 183, no. 7, pp. 4337–4345, October 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Birnbaum ME, Mendoza JL, Sethi DK, Dong S, Glanville J, Dobbins J, Özkan E, Davis MM, Wucherpfennig KW, and Garcia KC, “Deconstructing the Peptide-MHC Specificity of T Cell Recognition,” Cell, vol. 157, no. 5, pp. 1073–1087, May 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wooldridge L, Ekeruche-Makinde J, van den Berg HA, Skowera A, Miles JJ, Tan MP, Dolton G, Clement M, Llewellyn-Lacey S, Price DA, Peakman M, and Sewell AK, “A single autoimmune T cell receptor recognizes more than a million different peptides.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 287, no. 2, pp. 1168–1177, January 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Boesteanu A, Brehm M, Mylin LM, Christianson GJ, Tevethia SS, Roopenian DC, and Joyce S, “A molecular basis for how a single TCR interfaces multiple ligands.,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 161, no. 9, pp. 4719–4727, November 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Singh NK, Riley TP, Baker SCB, Borrman T, Weng Z, and Baker BM, “Emerging Concepts in TCR Specificity: Rationalizing and (Maybe) Predicting Outcomes.,” J Immunol, vol. 199, no. 7, pp. 2203–2213, October 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Klebanoff CA, Rosenberg SA, and Restifo NP, “Prospects for gene-engineered T cell immunotherapy for solid cancers.,” Nat. Med, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 26–36, January 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chang AY, Gejman RS, Brea EJ, Oh CY, Mathias MD, Pankov D, Casey E, Dao T, and Scheinberg DA, “Opportunities and challenges for TCR mimic antibodies in cancer therapy.,” Expert Opin Biol Ther, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 979–987, August 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Abelin JG, Keskin DB, Sarkizova S, Hartigan CR, Zhang W, Sidney J, Stevens J, Lane W, Zhang GL, Eisenhaure TM, Clauser KR, Hacohen N, Rooney MS, Carr SA, and Wu CJ, “Mass Spectrometry Profiling of HLA-Associated Peptidomes in Mono-allelic Cells Enables More Accurate Epitope Prediction,” Immunity, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 315–326, February 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bassani-Sternberg M, Bräunlein E, Klar R, Engleitner T, Sinitcyn P, Audehm S, Straub M, Weber J, Slotta-Huspenina J, Specht K, Martignoni ME, Werner A, Hein R, H Busch D, Peschel C, Rad R, Cox J, Mann M, and Krackhardt AM, “Direct identification of clinically relevant neoepitopes presented on native human melanoma tissue by mass spectrometry.,” Nat Commun, vol. 7, p. 13404, November 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gee MH, Han A, Lofgren SM, Beausang JF, Mendoza JL, Birnbaum ME, Bethune MT, Fischer S, Yang X, Gomez-Eerland R, Bingham DB, Sibener LV, Fernandes RA, Velasco A, Baltimore D, Schumacher TN, Khatri P, Quake SR, Davis MM, and Garcia KC, “Antigen Identification for Orphan T Cell Receptors Expressed on Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes.,” Cell, December 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Crawford F, Jordan KR, Stadinski B, Wang Y, Huseby E, Marrack P, Slansky JE, and Kappler JW, “Use of baculovirus MHC/peptide display libraries to characterize T-cell receptor ligands.,” Immunol. Rev, vol. 210, no. 1, pp. 156–170, April 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhang S-Q, Ma K-Y, Schonnesen AA, Zhang M, He C, Sun E, Williams CM, Jia W, and Jiang N, “High-throughput determination of the antigen specificities of T cell receptors in single cells.,” Nat Biotechnol, vol. 36, no. 12, pp. 1156–1159, November 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bentzen AK, Marquard AM, Lyngaa R, Saini SK, Ramskov S, Donia M, Such L, Furness AJS, McGranahan N, Rosenthal R, Straten PT, Szallasi Z, Svane IM, Swanton C, Quezada SA, Jakobsen SN, Eklund AC, and Hadrup SR, “Large-scale detection of antigen-specific T cells using peptide-MHC-I multimers labeled with DNA barcodes,” Nat Biotechnol, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 1037–1045, August 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gejman RS, Chang AY, Jones HF, DiKun K, Hakimi AA, Schietinger A, and Scheinberg DA, “Rejection of immunogenic tumor clones is limited by clonal fraction.,” Elife, vol. 7, p. 635, November 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Borbulevych OY, Piepenbrink KH, Gloor BE, Scott DR, Sommese RF, Cole DK, Sewell AK, and Baker BM, “T cell receptor cross-reactivity directed by antigen-dependent tuning of peptide-MHC molecular flexibility.,” Immunity, vol. 31, no. 6, pp. 885–896, December 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Davis-Harrison RL, Armstrong KM, and Baker BM, “Two different T cell receptors use different thermodynamic strategies to recognize the same peptide/MHC ligand.,” J. Mol. Biol, vol. 346, no. 2, pp. 533–550, February 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Stevanović S, Pasetto A, Helman SR, Gartner JJ, Prickett TD, Howie B, Robins HS, Robbins PF, Klebanoff CA, Rosenberg SA, and Hinrichs CS, “Landscape of immunogenic tumor antigens in successful immunotherapy of virally induced epithelial cancer.,” Science, vol. 356, no. 6334, pp. 200–205, April 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bacik I, Cox JH, Anderson R, Yewdell JW, and Bennink JR, “TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing)-independent presentation of endogenously synthesized peptides is enhanced by endoplasmic reticulum insertion sequences located at the amino- but not carboxyl-terminus of the peptide.,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 152, no. 2, pp. 381–387, January 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chang AY, Dao T, Gejman RS, Jarvis CA, Scott A, Dubrovsky L, Mathias MD, Korontsvit T, Zakhaleva V, Curcio M, Hendrickson RC, Liu C, and Scheinberg DA, “A therapeutic T cell receptor mimic antibody targets tumor-associated PRAME peptide/HLA-I antigens.,” J Clin Invest, vol. 127, no. 7, pp. 2705–2718, June 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Garboczi DN, Utz U, Ghosh P, Seth A, Kim J, VanTienhoven EA, Biddison WE, and Wiley DC, “Assembly, specific binding, and crystallization of a human TCR-alphabeta with an antigenic Tax peptide from human T lymphotropic virus type 1 and the class I MHC molecule HLA-A2.,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 157, no. 12, pp. 5403–5410, December 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ljunggren HG, Ohlén C, Höglund P, Franksson L, and Kärre K, “The RMA-S lymphoma mutant; consequences of a peptide loading defect on immunological recognition and graft rejection.,” Int. J. Cancer Suppl, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 38–44, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fellmann C, Zuber J, McJunkin K, Chang K, Malone CD, Dickins RA, Xu Q, Hengartner MO, Elledge SJ, Hannon GJ, and Lowe SW, “Functional identification of optimized RNAi triggers using a massively parallel sensor assay.,” vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 733–746, March 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Johnson LA, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Cassard L, Yang JC, Hughes MS, Kammula US, Royal RE, Sherry RM, Wunderlich JR, Lee C-CR, Restifo NP, Schwarz SL, Cogdill AP, Bishop RJ, Kim H, Brewer CC, Rudy SF, VanWaes C, Davis JL, Mathur A, Ripley RT, Nathan DA, Laurencot CM, and Rosenberg SA, “Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen.,” Blood, vol. 114, no. 3, pp. 535–546, July 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Robbins PF, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Zhao Y, Wargo JA, Zheng Z, Xu H, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Johnson LA, Bennett AD, Dunn SM, Mahon TM, Jakobsen BK, and Rosenberg SA, “Single and dual amino acid substitutions in TCR CDRs can enhance antigen-specific T cell functions.,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 180, no. 9, pp. 6116–6131, May 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ding YH, Smith KJ, Garboczi DN, Utz U, Biddison WE, and Wiley DC, “Two human T cell receptors bind in a similar diagonal mode to the HLA-A2/Tax peptide complex using different TCR amino acids.,” Immunity, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 403–411, April 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hausmann S, Biddison WE, Smith KJ, Ding YH, Garboczi DN, Utz U, Wiley DC, and Wucherpfennig KW, “Peptide recognition by two HLA-A2/Tax11-19-specific T cell clones in relationship to their MHC/peptide/TCR crystal structures.,” J Immunol, vol. 162, no. 9, pp. 5389–5397, May 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ataie N, Xiang J, Cheng N, Brea EJ, Lu W, Scheinberg DA, Liu C, and Ng HL, “Structure of a TCR-Mimic Antibody with Target Predicts Pharmacogenetics.,” J. Mol. Biol, vol. 428, no. 1, pp. 194–205, January 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hoof I, Peters B, Sidney J, Pedersen LE, Sette A, Lund O, Buus S, and Nielsen M, “NetMHCpan, a method for MHC class I binding prediction beyond humans.,” Immunogenetics, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 1–13, January 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schuster H, Peper JK, Bösmüller H-C, Röhle K, Backert L, Bilich T, Ney B, Löffler MW, Kowalewski DJ, Trautwein N, Rabsteyn A, Engler T, Braun S, Haen SP, Walz JS, Schmid-Horch B, Brucker SY, Wallwiener D, Kohlbacher O, Fend F, Rammensee H-G, Stevanovic S, Staebler A, and Wagner P, “The immunopeptidomic landscape of ovarian carcinomas.,” Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, vol. 114, no. 46, pp. E9942–E9951, November 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bassani-Sternberg M, Chong C, Guillaume P, Solleder M, Pak H, Gannon PO, Kandalaft LE, Coukos G, and Gfeller D, “Deciphering HLA-I motifs across HLA peptidomes improves neo-antigen predictions and identifies allostery regulating HLA specificity.,” PLoS Comput Biol, vol. 13, no. 8, p. e1005725, August 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bassani-Sternberg M, Pletscher-Frankild S, Jensen LJ, and Mann M, “Mass spectrometry of human leukocyte antigen class I peptidomes reveals strong effects of protein abundance and turnover on antigen presentation.,” Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 658–673, March 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Li Z, Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Fujiki F, Harada Y, Nakajima H, Masuda T, Fukuda Y, Kawakatsu M, Morimoto S, Katagiri T, Tatsumi N, Hosen N, Shirakata T, Nishida S, Kawakami Y, Udaka K, Kawase I, Oji Y, and Sugiyama H, “Identification of a WT1 protein-derived peptide, WT1, as a HLA-A 0206-restricted, WT1-specific CTL epitope.,” Microbiol. Immunol, vol. 52, no. 11, pp. 551–558, November 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kotturi MF, Assarsson E, Peters B, Grey H, Oseroff C, Pasquetto V, and Sette A, “Of mice and humans: how good are HLA transgenic mice as a model of human immune responses?,” Immunome Res, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 3, June 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Adams JJ, Narayanan S, Birnbaum ME, Sidhu SS, Blevins SJ, Gee MH, Sibener LV, Baker BM, Kranz DM, and Garcia KC, “Structural interplay between germline interactions and adaptive recognition determines the bandwidth of TCR-peptide-MHC cross-reactivity.,” Nat Immunol, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 87–94, January 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hermann C, van Hateren A, Trautwein N, Neerincx A, Duriez PJ, Stevanovic S, Trowsdale J, Deane JE, Elliott T, and Boyle LH, “TAPBPR alters MHC class I peptide presentation by functioning as a peptide exchange catalyst.,” Elife, vol. 4, p. 26, October 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ding YH, Baker BM, Garboczi DN, Biddison WE, and Wiley DC, “Four A6-TCR/peptide/HLA-A2 structures that generate very different T cell signals are nearly identical.,” Immunity, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 45–56, July 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.