Abstract

Background

A comprehensive intuition of the systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as a complex and multifactorial disease, is a biological challenge. Dealing with this challenge needs employing sophisticated bioinformatics algorithms to discover the unknown aspects. This study aimed to underscore key molecular characteristics of SLE pathogenesis, which may serve as effective targets for therapeutic intervention.

Methods

In the present study, the human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) microarray datasets (n = 6), generated by three platforms, which included SLE patients (n = 220) and healthy control samples (n = 135) were collected. Across each platform, we integrated the datasets by cross-platform normalization (CPN). Subsequently, through BNrich method, the structures of Bayesian networks (BNs) were extracted from KEGG-indexed SLE, TCR, and BCR signaling pathways; the values of the node (gene) and edge (intergenic relationships) parameters were estimated within each integrated datasets. Parameters with the FDR < 0.05 were considered significant. Finally, a mixture model was performed to decipher the signaling pathway alterations in the SLE patients compared to healthy controls.

Results

In the SLE signaling pathway, we identified the dysregulation of several nodes involved in the (1) clearance mechanism (SSB, MACROH2A2, TRIM21, H2AX, and C1Q gene family), (2) autoantigen presentation by MHCII (HLA gene family, CD80, IL10, TNF, and CD86), and (3) end-organ damage (FCGR1A, ELANE, and FCGR2A). As a remarkable finding, we demonstrated significant perturbation in CD80 and CD86 to CD28, CD40LG to CD40, C1QA and C1R to C2, and C1S to C4A edges. Moreover, we not only replicated previous studies regarding alterations of subnetworks involved in TCR and BCR signaling pathways (PI3K/AKT, MAPK, VAV gene family, AP-1 transcription factor) but also distinguished several significant edges between genes (PPP3 to NFATC gene families). Our findings unprecedentedly showed that different parameter values assign to the same node based on the pathway topology (the PIK3CB parameter values were 1.7 in TCR vs − 0.5 in BCR signaling pathway).

Conclusions

Applying the BNrich as a hybridized network construction method, we highlight under-appreciated systemic alterations of SLE, TCR, and BCR signaling pathways in SLE. Consequently, having such a systems biology approach opens new insights into the context of multifactorial disorders.

Keywords: SLE, Signaling pathways, BNrich, Cross-platform normalization, Mixture model, Systems biology

Introduction

Called as “the Great Imposter,” systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic and complex autoimmune disease with multisystem manifestations [1, 2]. The disease prevalence is estimated about 5 million people worldwide, and it occurs mostly before the age of 45 years [3–5]. The loss of central and peripheral tolerance to self, as a result of genetic susceptibility or environmental factors, is proposed to be a crucial first step in the SLE development [6, 7].

Certain lines of evidence suggested that a break in central B cell tolerance results in autoreactive clones to reach the periphery [8], which followed by autoantibodies’ production and immune complex deposition and finally damage the end organ [9, 10]. Likewise, an aberrant TCR signaling followed by hyper-responsiveness of T cells has been shown in SLE patients [11]. The genome-wide association studies (GWAS) coupled with gene expression profiling data shed light on the critical role of genes involved in B cell receptor (BCR) and T cell receptor (TCR) signaling pathways in SLE pathogenesis [7]. Despite numerous strong-minded studies have been done, the SLE pathogenesis is still far from clear. Many studies used bioinformatics approach such as enrichment analysis and determined pathways implicated in multifactorial disease pathogenesis. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study with deep insight into the implicated pathways in SLE.

Towards a better intuition of molecular mechanisms involved in multifactorial immune-related diseases especially SLE, lots of researchers acknowledge the gene network approach which helps to prioritize main driver genes and pathways, to propose a better drug development [12]. Bayesian networks (BNs), as a worthwhile powerful gene network construction methods, integrate and model biological data with causal relationships [13–17]. By applying gene expression data of SLE patients, Li et al. recently reconstructed a BN, in which prior edges were randomly sampled based on the text-mining in SLE pathogenesis [12]. Remarkably, some methods such as BNrich were also developed based on BN properties [18] which identifies significant genes (nodes) and biological relationships (edges). The BNrich method has two key concepts: (1) the structure of BN is reconstructed by the signaling pathway structure, and (2) the expression level of the gene (node) is modeled as a regression function of expression levels of its upstream genes (parents) [18].

As a method that is widely used to integrate gene expression data, cross-platform normalization (CPN) (1) increases sample sizes and improves gene signature selection [19–23], (2) rises the heterogeneity of the overall estimate, and (3) decreases the effects of individual study-specific biases [22, 23]. On the other hand, the mixture model, known as a model averaging method, is well documented to integrate node and edge parameters based on their distribution [24].

With systems biology approach, we aimed to illustrate the superiority of using CPN and mixture model method and the BNrich to better understand new aspects of underlying molecular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of complex diseases such as SLE. Here, we concentrated on SLE, BCR, and TCR signaling pathways, which are among the most enriched pathways in SLE, to highlight significant alterations of those pathways in SLE patients compared to healthy controls. Besides the altered gene expression level, we demonstrated several significant intergenic relationships which can be proposed as effective targets for therapeutic intervention in SLE patients.

Methods

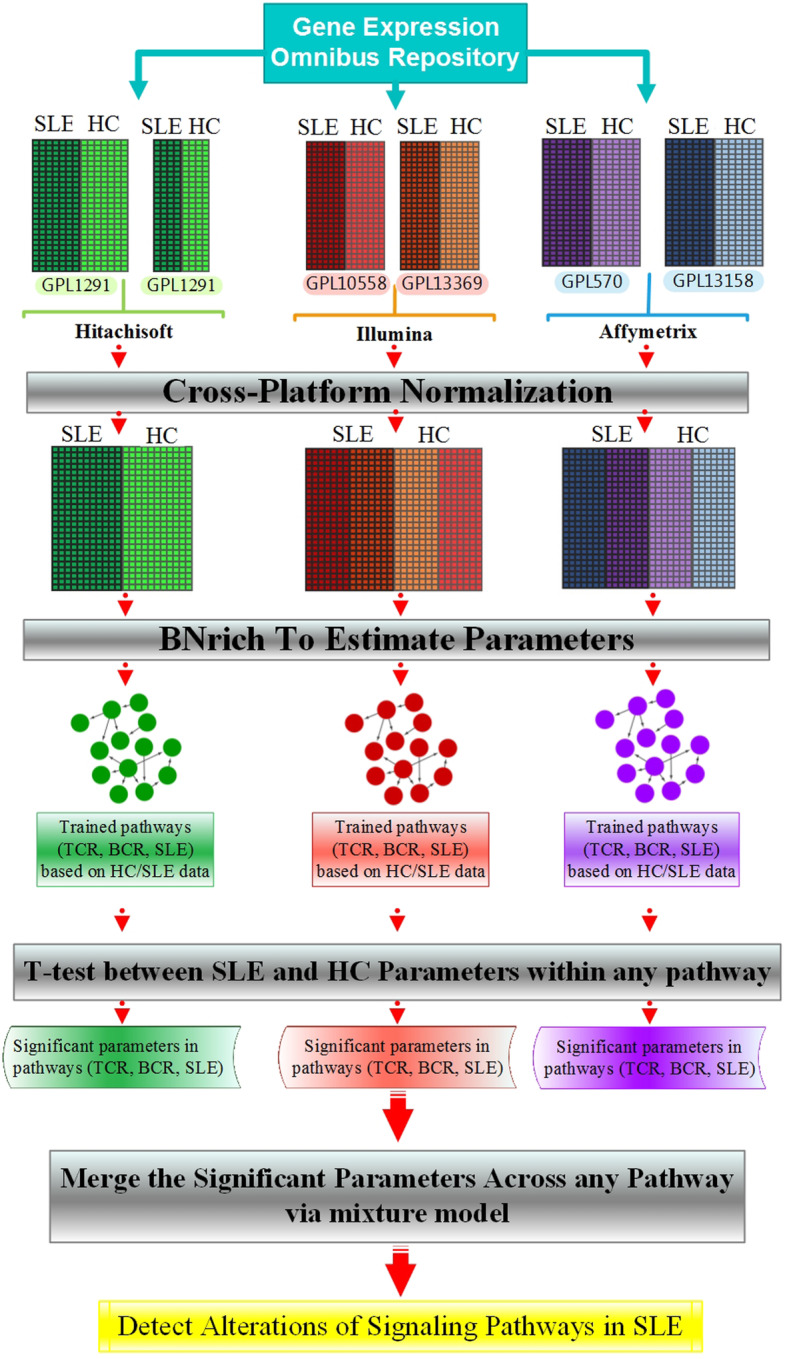

The human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) microarray datasets (n = 6) associated with SLE were downloaded and integrated by CPN method. Subsequently, we employed SLE, TCR, and BCR signaling pathways as structures of BNs and we determined significant node and edge parameters by BNrich method in each dataset independently. Consequently, significant parameters of all datasets were merged through mixture model method and key driver parameters in the selected pathways were defined (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Workflow and analysis procedure to identify signaling pathway alterations in SLE patients. At the first step, human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) microarray datasets associated with SLE, which were generated using three platforms, were downloaded and each paired data related to the same platform integrated by CPN method. Subsequently, SLE, TCR, and BCR signaling pathways were employed as structures of BNs and trained by three major datasets independently by BNrich method. Afterwards, the differences between any paired corresponding parameters related to patients and controls were examined by independent t test. Consequently, the significant parameters merged by the mixture model to achieve the key driver parameters in studied pathways

Gene expression datasets

The human PBMC microarray datasets that contain both SLE patient and healthy control (HCs) samples, published or updated in 2010–2019, were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database: GSE 17755 [25], GSE 12374 [26], GSE 50772 [27], GSE 81622 [28], GSE 121239 [29–31], and GSE 126307 [32]. We described the details of the data in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the datasets used in the study

| No. | GSE no. | GPL/platform | No. of sample | Cell type | Update (year) | Race | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLE patients | Controls | ||||||

| 1 | 17755 | 1291/Hitachisoft | 22 | 55 | PBMC | 2010 | Japanese |

| 2 | 12374 | 1291/Hitachisoft | 11 | 6 | PBMC | 2012 | Japanese |

| 3 | 50772 | 570/Affymetrix | 61 | 20 | PBMC | 2015 | Unknowna |

| 4 | 81622 | 10558/Illumina | 30 | 25 | PBMC | 2016 | Unknownb |

| 5 | 121239 | 13158/Affymetrix | 65c | 20 | PBMC | 2018 | Caucasian/African Americand |

| 6 | 126307 | 13369/Illumina | 31 | 9 | PBMC | 2019 | Several racese |

aThe data were collected in the USA/South San Francisco, but the race of subjects is unknown

bThe data were collected in the USA/Dallas, but the race of subjects is unknown

cOnly the data related to the first visit (v1) samples of any patient were entered in the analysis

dThis subset of the samples is derived from a preliminary dataset which were collected in the USA/Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional, and most of the race of subjects (92.8%) are Caucasian and African American

eThe data collected in USA/Dallas, but the race of subjects is Australian, Australian (Irish/Scottish descent), born in India—ethnicity unknown, Caucasian, Caucasian/Japanese, English, Filipino, Indian, Iraqi, Latin American, Persian, Spanish, and White Australian/Anglo-Celtic

Cross-platform normalization

Each expression dataset was preprocessed and normalized by normalizeQuantiles function from R package limma [33]. Then, we performed CPN [23] with Reduce function in R to integrate each paired gene expression data emanated from the same platform. Finally, we have three major datasets from Affymetrix, Illumina, and Hitachisoft; each platform has a SLE patient group and a HC group. Afterwards, the empirical Bayes method (ComBat) from the R package sva was used for batch effect removal [34].

BNrich approach

To reconstruct BN structures, the SLE (hsa:05322), TCR (hsa:04660), and BCR (hsa:04662) signaling pathways were implemented. All of the pathways were extracted directly from the KEGG database (Release 90.0, April 1, 2019) [35].

In the parameter estimate step, the mean value of the expression for each gene (node) can be modeled as a linear regression of its parents’ (upstream) gene expression [18]. When Y gene has X1, X2…Xp − 1 parents in the network, and and describe the estimations of Y for the SLE patient and HC datasets, respectively, they can be modeled as follows:

| 1 |

In the SLE- and HC-associated trained BNs, the constant coefficient β(s/h)0 demonstrates the expression level of Y gene, known as a node parameter. The coefficients of X1, X2…Xp − 1 are the parameters of the edge in the trained BNs which reveal a biological relationship between two genes, Y and X. For example, the value of βs3 is the edge parameter between Y and X3 genes in the network structure related to SLE patient data and shows the value of the biological relationship between these two genes. The εc and εh are the residual values.

Using Eq. 1, the node and edge parameters of the BN structures (derived from SLE, BCR, and TCR signaling pathways) were estimated for SLE patient- and HC-gene expression datasets of the three related platforms, separately. Subsequently, we compared the parameters of trained networks in SLE patients (βs) with HCs (βh) by independent t test [36] and gained the β∗(j) (j ∈ {A, I, H}) which is the significant parameter based on false discovery rate (FDRj < 0.05) for Affymetrix (A), Illumina (I), and Hitachisoft (H) datasets.

The estimated parameters of BNs have the following distribution [37]:

| 2 |

Accordingly, the significant parameters had been distributed as follows:

| 3 |

Therefore, we had up to three significant parameters for each node (or edge) which are β∗(A), β∗(I), and β∗(H).

Merge significant parameters via mixture model

By using the mixture model approach [38], we merged the significant parameters of three platform-associated datasets and calculated the significant final parameters, both at the node and edge level. The final parameters, βf, have a normal distribution, and their mean and variance were defined by:

| 4 |

where NA = 166, NI = 95, and NH = 94 were the number of subjects in Affymetrix, Illumina, and Hitachisoft. Since the range of the variances across final parameters is varied, their mean is divided by the standard deviation to achieve comparable parameters. Hence, we plotted the figures based on the following definition:

| 5 |

If the parameter β∗(j) in each dataset was not significant, its mean and variance were considered to be zero in calculating the corresponding final parameter. When the βf was associated with the node parameters, the sign of μ∗(βf) indicated upregulation (+) or downregulation (−) of the gene and the absolute value of μ∗(βf) was used to measure the value of activation or inhibition. Where the βf was associated with the edge parameters, the sign of μ∗(βf) indicated increasing (+) or decreasing (−) biological function and the absolute value of μ∗(βf) was used to measure the value of these increased or decreased functions.

Results

Data integration using CPN

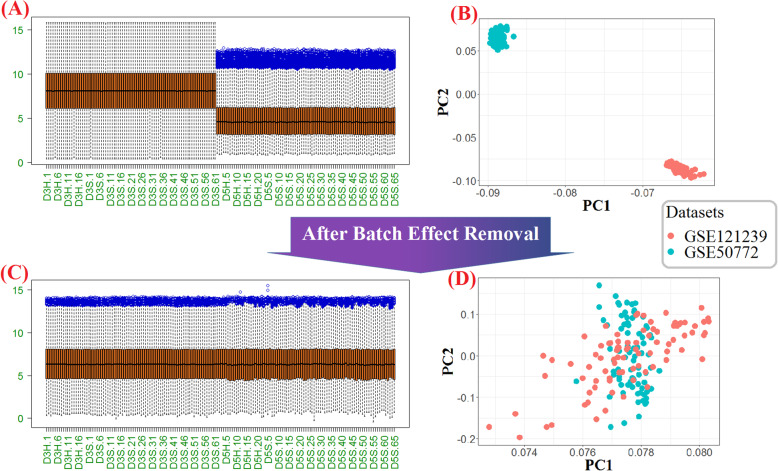

After downloading the six mentioned datasets (Table 1), to reduce the batch effect generated between different arrays, each paired data emanated from the same platform was integrated using the ComBat algorithm. The efficiency of the ComBat process in our integration for batch removal can be verified by the comparative boxplots and principle component analysis (PCA) plots (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1).

Fig. 2.

Graphical demonstration of the batch effect removal using ComBat for Affymetrix platforms. Boxplot (a) and PCA plot (b) show the gene expression distributions and the samples of microarray datasets before batch effects removal respectively. As the same way, Boxplot (c) and PCA plot (b) show the corresponding concepts after batch removal. The boxplots distributions show the normalization and decreasing technical diversities between datasets; and in the horizontal axis, the jth healthy control subjects and the jth SLE patient in the ith dataset were illustrated with DiH.j and DiS.j, correspondingly. In the PCA plots, each dot represents one sample, and the color indicates its dataset

We did not observe any genes lost after performing CPN on Illumina and Hitachisoft related data, while in the Affymetrix platform, information of about 5.4% and 8.5% of genes in the datasets GSE 50772 and GSE 121239 were lost correspondingly. Considering the CPN benefits, we pursue of using all 166 samples of Affymetrix platform simultaneously instead of analyzing 81 or 85 individual samples (Table 2).

Table 2.

The percentage of lost genes after running CPN

| GSE no. | Platform | Genes (n) | Genes after CPN (n) | Lost genes (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50772 | Affymetrix | 19,689 | 18,627 | 5.4 |

| 121239 | 20,351 | 8.5 | ||

| 81622 | Illumina | 30,500 | 30,500 | 0 |

| 126307 | 30,500 | 0 | ||

| 17755 | Hitachisoft | 13,102 | 13,102 | 0 |

| 12374 | 13,102 | 0 |

Identify significant parameters using BNrich

To identify significant parameters, including nodes and edges, in SLE patients against HCs in every major dataset, the SLE, TCR, and BCR signaling pathways were utilized as structures of BN and significant parameters (nodes and edges) were determined using BNrich method. Table 3 presents the number of significant node and edge parameters in the three dataset-associated platforms based on FDR < 0.05 for SLE, TCR, and BCR signaling pathways.

Table 3.

The number of all significant node and edge parameters of BNs extracted from SLE, TCR, and BCR signaling pathways obtained via BNrich

| Signaling pathways | FDR < 0.05 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affymetrix | Illumina | Hitachisoft | ||||

| Nodes | Edges | Nodes | Edges | Nodes | Edges | |

| SLE | 73 | 4 | 108 | 11 | 50 | 7 |

| TCR | 82 | 161 | 81 | 120 | 75 | 75 |

| BCR | 57 | 103 | 68 | 91 | 56 | 60 |

According to our results, 34 significant nodes and the C1QB → C2 edge were common among all datasets in the SLE pathway. Across datasets of all platforms, 53 nodes and 26 edges of the TCR signaling pathway and 36 nodes and 30 edges of the BCR signaling pathway were common. All significant parameters of different platforms, based on three examined signaling pathways, are presented in Additional file 2.

Determine the key driver parameters of signaling pathways via mixture model

To distinguish the altered signaling pathway parameters in SLE patients compared to HCs, the identified significant parameters of all dataset merged by the mixture model method (Eqs. 4 and 5), the range of μ∗(βf) in all nodes and edges are represented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The minimum and maximum final parameter values of nodes and edges in three signaling pathways

| SLE | TCR | BCR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodes | Edges | Nodes | Edges | Nodes | Edges | ||

| μ∗(βf) | Min | − 1.70 | − 0.46 | − 1.68 | − 1.01 | − 1.39 | − 0.96 |

| Max | 2.37 | 0.55 | 1.43 | 1.12 | 1.43 | 0.94 | |

The three nodes and edges that have the extreme values of μ∗(βf) in each desired pathway are illustrated in Table 5, and the all μ∗(βf) represented in Additional file 2.

Table 5.

The top three nodes and edges of the studied pathways

| Nodes | Edges | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down | Up | Increasing biological function | Decreasing biological function | |

| SLE | SNRPD3 | FCGR1A | C1R → C4A | C1QA → C2 |

| HLA-DPB1 | CTSG | C1QB → C4A | CD86 → CD28 | |

| HLA-DMA | ELANE | C4B → C3 | C1S → C4A | |

| TCR | CD3E | BCL10 | RASGRP1 → NRAS | NCK2 → PAK3 |

| PPP3CC | PAK5 | CBLB→FYN | MAP2K1 → MAPK1 | |

| CBLB | MAPK14 | PPP3CB → NFATC3 | CD3E → FYN | |

| BCR | INPP5D | BCL10 | AKT3 → IKBKG | SYK → PIK3AP1 |

| PPP3CC | PIK3AP1 | MAPK1 → FOS | MAP2K1 → MAPK1 | |

| CD81 | IFITM1 | PPP3CC → NFATC1 | VAV1 → RAC2 | |

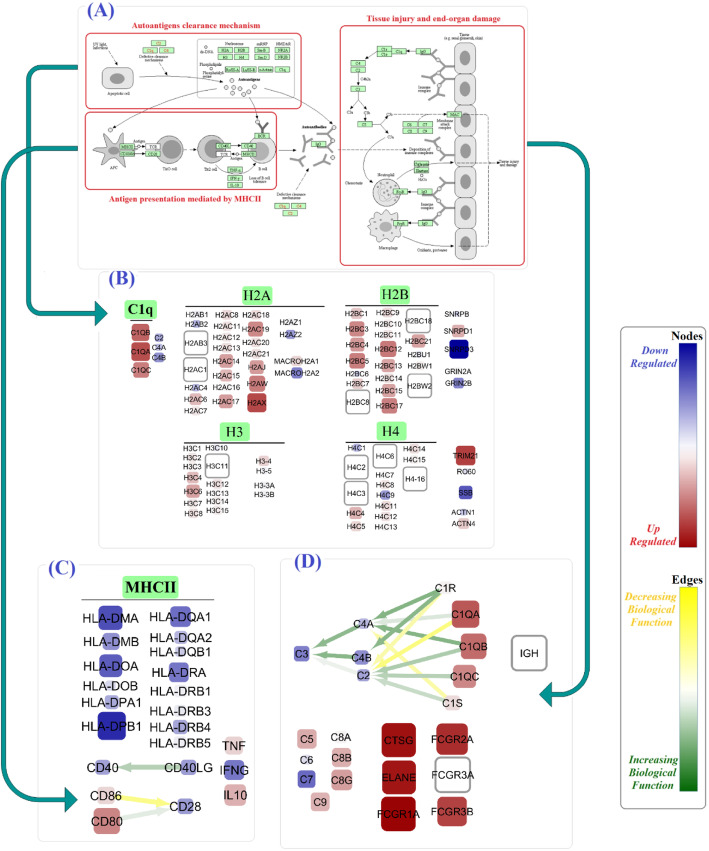

Among genes involved in the clearance mechanism of SLE pathway, TRIM21, H2AX, C1QA, C1QB, H2BC12, and H2BC12 were mostly upregulated. However, SNRPD3, SSB, MACROH2A2, GRIN2B, and C4B were mostly downregulated. In antigen presentation process mediated by MHCII, nodes such as HLA-DPB1, HLA-DMA, CD80, IL10, and TNF and three edges, CD80 and CD86 to CD28 and DD40LG to CD40, were found to be dysregulated.

In addition, our analysis showed that among genes which participated into damaging of the end organ, the expression of genes like FCGR1A, CTSG, ELANE, FCGR3B, FCGR3B, and C1QA were increased and the expression of C7, C3, C4B, C2, and C4A genes were decreased. Particularly, in that functional part of SLE pathway, we also found dysregulation of several important edges like C1R, C1S, and C1QB to C2 (Fig. 3 and Additional file 2).

Fig. 3.

The alterations in SLE signaling pathway based on calculated final parameters. The representation design of KEGG-extracted SLE signaling pathways (a), genes involved in autoantigen clearance (b), antigen presentation mediated by MHCII (c), and tissue injury and end-organ damage (d). The color and size of nodes reflect the values and the absolute values of the μ∗(βf), respectively, and it is equivalent to the upregulation or downregulation of genes. Moreover, the color of the edges reflects the values of the μ∗(βf), respectively, and it is equivalent to the increasing or decreasing biological function

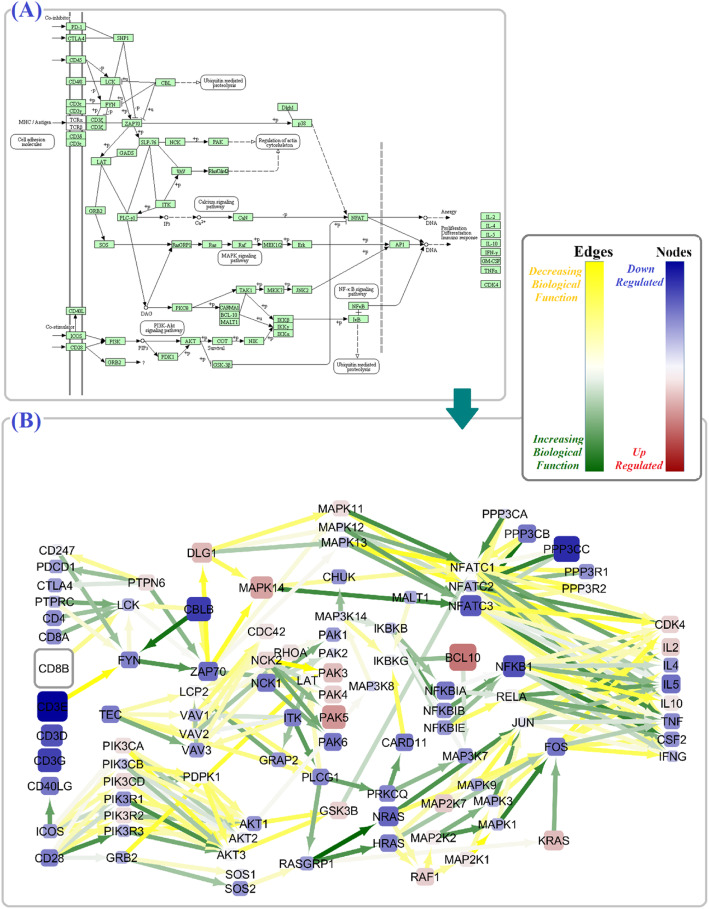

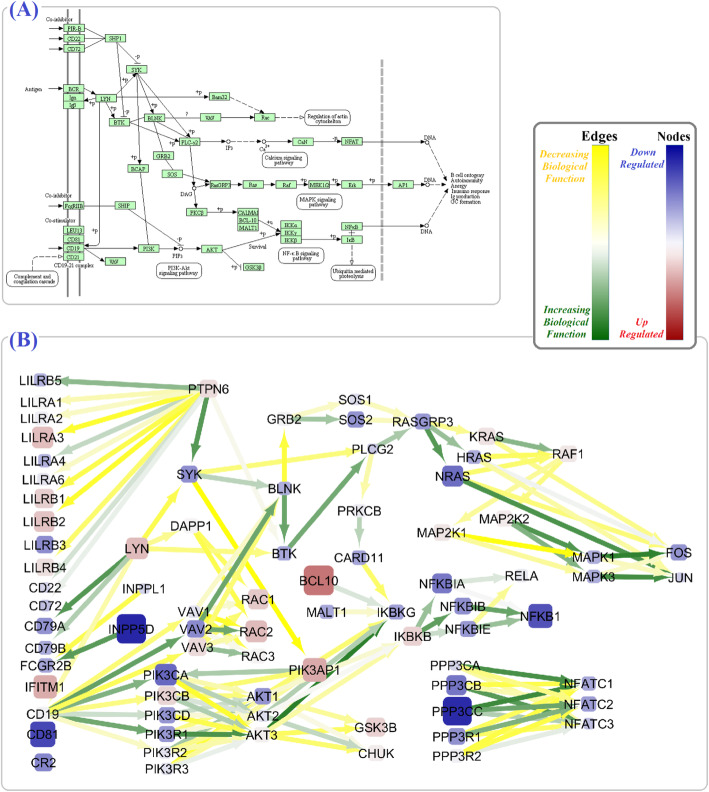

By integrating BCR and TCR signaling pathway information with gene expression data, we identified many of the altered key driver genes in these pathways among SLE patients. Our results revealed 46 shared dysregulated nodes (e.g., AKT1, AKT2, AKT3, MALT1, MAPK3, SOS) and 64 common dysregulated edges (e.g., PIK3CA to AKT1 and AKT2, IKBKB to NFKBIA, NFKBIB and NFKBIE) between these two pathways (Figs. 4 and 5 and Additional file 2).

Fig. 4.

The alterations in TCR signaling pathway. The schematic figure of the TCR signaling pathway in KEGG (a), and the TCR signaling pathway alterations based on calculated final criteria (b). The color and size of nodes reflect the values and the absolute values of the μ∗(βf), respectively, and it is equivalent to the upregulation or downregulation of genes. Moreover, the color of the edges reflects the values of the μ∗(βf), respectively, and it is equivalent to the increasing or decreasing biological function

Fig. 5.

The alterations in the BCR signaling pathway. The schematic figure of the BCR signaling pathway in KEGG (a), and the BCR signaling pathway alterations based on calculated final criteria (b). The color and size of nodes reflect the values and the absolute values of the μ∗(βf), respectively, and it is equivalent to the upregulation or downregulation of genes. Moreover, the color of the edges reflects the values of the μ∗(βf), respectively, and it is equivalent to the increasing or decreasing biological function

Discussion

In the context of identifying SLE gene signature, previous studies have been limited to gene expression level regardless of intergenic relationship. In the present study, for the first time, through data aggregation via BNrich, CPN, and mixture model method, we merged several diverse gene expression data into SLE, TCR ,and BCR signaling pathways and unraveled key genes and intergenic relationships that may serve as effective targets for therapeutic intervention in SLE patients. By using the CPN method, we increased the sample size and decreased the heterogeneity of the samples in comparison to previous studies [25–32]. According to BNrich properties, we could integrate two levels of biological data, gene expression and signaling pathways. Hence, the value of the node and edge parameters in addition to being influenced by gene expression data also depends on the topology of the underlying pathway [18]. For instance, in the Illumina platform, the mean value of the final parameter in PIK3CB gene was 1.7 and − 0.5, and the mean value of the final parameter in edge PPP3CC → NFATC3 was − 0.07 and 0.12, in TCR and BCR signaling pathways, correspondingly (Additional file 2). Moreover, we used the mixture model, as a model averaging method, to determine the key driver parameters across all datasets. In contrast to model selection, the mixture model dramatically minimizes the risk relative to selection [24].

First, we investigated SLE signaling pathway (hsa:05322), which included three sections: (1) autoantigen clearance mechanism, (2) antigen presentation mediated by MHCII, and (3) tissue injury and end-organ damage. The uncleaned apoptotic components which recognized by both the innate and the adaptive immune systems can trigger the pathogenesis of SLE. Therefore, the dysregulation of effective genes involved in the clearance of apoptotic components has a fundamental role in SLE [39–43]. In the same vein, we showed significant upregulation of 69 genes which include TRIM21, C1Q gene family, and SNRPD1 and significant downregulation of 15 genes which include SNRDP3, SSB, and GRIN2B (Fig. 3b). Over the recent years , TRIM21, SSB, and C1Q have gained particular attention in SLE [44–46]. In line with earlier studies, we also underscored the dysregulation of histone gene family (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) [47]. The clearance procedure followed by antigen presentation was mediated by MHCII. While CD80, CD86, IL10, and TNF-α as key mediators of this pathway were distinctively activated, the HLA gene family members (DPB1, DQA1, DMA, etc.) showed the significant reduction (Fig. 3c). The association of HLA genes with childhood- and adult-onset SLE was represented recently [48]. Besides, the elevated level of serum TNF-α has been shown in SLE patients. Using anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies like infliximab and etanercept to treat SLE patients further confirmed the importance of TNF as a targeting agent [49]. Despite the negative results for CD40LG and CD40 node parameters, the edge parameter between them showed a positive biological function. Therefore, we further highlight the therapeutic effect of CD40-CD40LG pathway blockade in SLE [50]. Although CD28 expression was reduced, CD80 → CD28 biological function was enhanced significantly (Fig. 3c). At the end of the SLE signaling pathway, end-organ damage occurs via dysregulation of several genes. Among them, the deficiencies of early complement proteins, including C1, C4, and C2, were strongly associated with the development of SLE [51]. Our results showed that not only the parameters of C3, C7, and C4B were reduced but also C1R → C2, C1QA → C2, and C1S → C4A biological functions were lessened (Fig. 3d). Additionally, our findings showed augmented ELANE, FCGR1A, FCGR2A, FCGR3B, and CTSG node parameters. By applying a multicohort analysis of 7471 transcriptomic profiles, Haynes et al. have just introduced ELANE as an “Under-appreciated SLE MetaSignature.” [52] In a recent study, the FCGR2A polymorphisms have been linked to SLE susceptibility in Mexican patients [46].

As outlined earlier, the fundamental importance of BCR and TCR signaling pathways in SLE pathogenesis has been well established via both clinical and experimental evidence [53–55]. In the TCR signaling pathway, we observed lower expression of several genes like CBLB, PPP3CC, NFKB1, CD3E, and ZAP70. Recently, a study by Matsuo et al. revealed that a genetic mutation in ZAP70 resulted in the TCR signaling defect which followed by T follicular helper (Tfh) cell development and the manifestation of lupus-like systemic autoimmunity [56]. Having several significant edges with the other nodes proposes ZAP70 as a hub gene of the TCR signaling pathway implicated in SLE pathogenesis. Interestingly, the perturbation in TCR culminated to enhanced expression of CDK4, IL2, and IL10 genes. In the BCR signaling pathway, the most up- and downregulated genes were BCL10 and INPP5D, respectively. Furthermore, we also identified significant lower expression of CD79A and CD79B (also known as Igα and Igβ, respectively). In a meta-analysis of GWAS results, Julià et al. reported BCR signaling pathway as the most significant biological process and BCL10 and CD79A among top single markers associated with SLE [57].

Interestingly, our results addressed the dysregulation of several noteworthy node and edge parameters shared by both TCR and BCR signaling pathways. Among them PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and VAV gene homologs were altered; AKT1, AKT2 and VAV1, VAV2 expression levels were particularly reduced (Figs. 4 and 5). Previously, some researcher confirmed these results and proved phosphorylation level of AKT in SLE patients, which further support the major role of PI3K/Akt/TSC/mTOR signaling pathway in the disease [58, 59]. According to our results, the MAPK signaling pathway as an effective subnetwork of TCR and BCR signaling in SLE pathogenesis [59] also displayed a significant dysregulation, especially higher expression of MAPK1, MAPK3, and PPP3CA genes. Similarly, the strong association of PPP3CA with SLE-like disease has been described as new [60]. Moreover, we observed the reduced expression of JUN and FOS together with some increased or decreased biological relations with their neighbors in both TCR and BCR pathways. JUN and FOS are subunits of the transcription factor AP-1 which regulates cytokines and chemokines of TCR and BCR pathways in inflammatory and autoimmune disease [61].

Further investigation will be required to evaluate the efficiency of CD80 and CD86 → CD28, C1R and C1QA → C2, and C1S → C4B biological functions, PI3K/AKT signaling pathways, besides JUN gene as therapeutic targets in SLE disease. Moreover, analyzing the RNA-seq datasets could be better for distinguishing expression levels and biological relationships of genes’ isoforms in considered signaling pathways. It is necessary to examine the BNrich among some other autoimmune diseases in order to identify SLE signature genes more precisely.

Conclusions

In the present study, we exploited BNrich to hybridize intergenic relations inferred from signaling pathways and gene expression profiling to improve the insight about SLE as a complex disease. We figured out the significant genes and intergenic relationships and systemic alterations in SLE, TCR, and BCR signaling pathways. Through cross-platform normalization and meta-analysis, large-enough SLE patients were analyzed. Since multiple platforms were utilized, the effects of individual study-specific biases were reduced.

Notably, the proposed computational methodology can be applied to a variety of complex diseases to illuminate new mechanistic insights in their pathogenesis.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Batch effect removal results. The box plots and PCA plots related to CPN results for Hitachisoft and Illumina platforms.

Additional file 2. Significant and final parameters. The significant parameters of different platforms and the final parameters based on the mixture model in three examined signaling pathways.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mao Tanabe from the Institute of Chemical Research, Kyoto University, for his expert insights in signaling pathways shared with us via several emails, contributing greatly to the quality of this research.

Abbreviations

- BNs

Bayesian networks

- BCR

B cell receptor

- CPN

Cross-platform normalization

- CIA

Collagen-induced arthritis

- FDR

False discovery rate

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- GWAS

Genome-wide association studies

- HC

Healthy control

- IFN

Interferon

- PEA

Pathway enrichment analysis

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Tfh

T follicular helper

- TCR

T cell receptor

Authors’ contributions

SM, ASZ, VRT, and KK established the method and developed the R package of BNrich. SM, ASZ, and VRT performed the data and statistical analysis. SM contributed to the data collection and evaluation. ZS, KK, and SM contributed to the interpretation of data. All authors performed the editing, participated in the finalization of the manuscript, and approved the final draft.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Tehran, Tehran.

Availability of data and materials

The R package of BNrich is available on Cran (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/BNrich/index.html). All gene expression data are available in the GEO database, and the raw data of signaling pathways are available in KEGG.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13075-020-02239-3.

References

- 1.Yang F, Zhai Z, Luo X, Luo G, Zhuang L, Zhang Y, Li Y, Sun E, He Y. Bioinformatics identification of key candidate genes and pathways associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;39:425–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Javinani A, Ashraf-Ganjouei A, Aslani S, Jamshidi A, Mahmoudi M. Exploring the etiopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus: a genetic perspective. Immunogenetics. 2019;71:283–297. doi: 10.1007/s00251-019-01103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, Liang MH, Kremers HM, Mayes MD, Merkel PA, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garris C, Shah M, Farrelly E. The prevalence and burden of systemic lupus erythematosus in a medicare population: retrospective analysis of medicare claims. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2015;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Meas R, Burak MJ, Sweasy JB. DNA repair and systemic lupus erythematosus. DNA Repair (Amst) 2017;56:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zharkova O, Celhar T, Cravens PD, Satterthwaite AB, Fairhurst AM, Davis LS. Pathways leading to an immunological disease: systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:i55–i66. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsokos GC, Lo MS, Reis PC, Sullivan KE. New insights into the immunopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:716–730. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, Young JW, Meffre E, Nussenzweig MC. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science (80-. ) 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanson CL, Wilson TJ, Strauch P, Colonna M, Pelanda R, Torres RM. Type I IFN enhances follicular B cell contribution to the T cell-independent antibody response. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1485–1500. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu HC, Grusdat M, Pandyra AA, Polz R, Huang J, Sharma P, Deenen R, Köhrer K, Rahbar R, Diefenbach A, et al. Type I interferon protects antiviral CD8+ T cells from NK cell cytotoxicity. Immunity. 2014;40:949–960. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsuyama T, Tsokos GC, Moulton VR. Aberrant T cell signaling and subsets in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Li Y, Higgs RE, Hoffman RW, Dow ER, Liu X, Petri M, Wallace DJ, Dörner T, Eastwood BJ, Miller BB, et al. A Bayesian gene network reveals insight into the JAK-STAT pathway in systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One. 2019;14:1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Yu J, Smith VA, Wang PP, Hartemink AJ, Jarvis ED. Advances to Bayesian network inference for generating causal networks from observational biological data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3594–3603. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gendelman R, Xing H, Mirzoeva OK, Sarde P, Curtis C, Feiler HS, McDonagh P, Gray JW, Khalil I, Korn WM. Bayesian network inference modeling identifies TRIB1 as a novel regulator of cell-cycle progression and survival in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:1575–1585. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo, Y.; El Naqa, I.; McShan, D.L.; Ray, D.; Lohse, I.; Matuszak, M.M.; Owen, D.; Jolly, S.; Lawrence, T.S.; Kong, F.-M. (Spring); et al. Unraveling biophysical interactions of radiation pneumonitis in non-small-cell lung cancer via Bayesian network analysis. Radiother.Oncol. 2017, 123, 85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Agrahari R, Foroushani A, Docking TR, Chang L, Duns G, Hudoba M, Karsan A, Zare H. Applications of Bayesian network models in predicting types of hematological malignancies. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6951. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24758-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramos J, Das J, Felty Q, Yoo C, Poppiti R, Murrell D, Foster PJ, Roy D. NRF1 motif sequence-enriched genes involved in ER/PR −ve HER2 +ve breast cancer signaling pathways. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;172:469–485. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4905-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maleknia, S.; Sharifi-Zarchi, A.; Tabar, V.R.; Namazi, M.; Kavousi, K. BNrich: a Bayesian network approach to the pathway enrichment analysis. bioRxiv 2020, 2020.01.13.905448.

- 19.Hamid JS, Hu P, Roslin NM, Ling V, Greenwood CMT, Beyene J. Data integration in genetics and genomics: methods and challenges. Hum Genomics Proteomics. 2009;1:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Larsen MJ, Thomassen M, Tan Q, Sørensen KP, Kruse TA. Microarray-based RNA profiling of breast cancer: batch effect removal improves cross-platform consistency. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Irigoyen A, Jimenez-Luna C, Benavides M, Caba O, Gallego J, Ortuño FM, Guillen-Ponce C, Rojas I, Aranda E, Torres C, et al. Integrative multi-platform meta-analysis of gene expression profiles in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients for identifying novel diagnostic biomarkers. PLoS One. 2018;13:1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Taminau J, Lazar C, Meganck S, Nowé A. Comparison of merging and meta-analysis as alternative approaches for integrative gene expression analysis. ISRN Bioinforma. 2014;2014:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2014/345106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh C, Hu P, Batt J, Santos C. Microarray meta-analysis and cross-platform normalization: integrative genomics for robust biomarker discovery. Microarrays. 2015;4:389–406. doi: 10.3390/microarrays4030389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Yu D, Zou G, Liang H. Optimal model averaging estimation for generalized linear models and generalized linear mixed-effects models. J Am Stat Assoc. 2016;111:1775–1790. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2015.1115762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee HM, Sugino H, Aoki C, Nishimoto N. Underexpression of mitochondrial-DNA encoded ATP synthesis-related genes and DNA repair genes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011;13:R63. doi: 10.1186/ar3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee HM, Mima T, Sugino H, Aoki C, Adachi Y, Yoshio-Hoshino N, Matsubara K, Nishimoto N. Interactions among type I and type II interferon, tumor necrosis factor, and β-estradiol in the regulation of immune response-related gene expressions in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R1. doi: 10.1186/ar2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy WP, Maciuca R, Wolslegel K, Tew W, Abbas AR, Chaivorapol C, Morimoto A, McBride JM, Brunetta P, Richardson BC, et al. Association of the interferon signature metric with serological disease manifestations but not global activity scores in multiple cohorts of patients with SLE. Lupus Sci Med. 2015;2:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.yun lian Whole genome transcription and DNA methylation analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells identified aberrant gene regulation pathways in systemic lupus erythematosus Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE82221 (accessed on Apr 15, 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Zollars E, Courtney SM, Wolf BJ, Allaire N, Ranger A, Hardiman G, Petri M. Clinical application of a modular genomics technique in systemic lupus erythematosus: Progress towards precision medicine. Int J Genomics. 2016;2016:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Toro-Domínguez D, Martorell-Marugán J, Goldman D, Petri M, Carmona-Sáez P, Alarcón-Riquelme ME. Stratification of systemic lupus erythematosus patients into three groups of disease activity progression according to longitudinal gene expression. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:2025–2035. doi: 10.1002/art.40653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petri M, Fu W, Ranger A, Allaire N, Cullen P, Magder LS, Zhang Y. Association between changes in gene signatures expression and disease activity among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. BMC Med Genet. 2019;12:1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Jiang SH, Athanasopoulos V, Ellyard JI, Chuah A, Cappello J, Cook A, Prabhu SB, Cardenas J, Gu J, Stanley M, et al. Functional rare and low frequency variants in BLK and BANK1 contribute to human lupus. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu DI, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leek JT, Johnson WE, Parker HS, Jaffe AE, Storey JD. The SVA package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:882–883. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrade JM, Estévez-Pérez MG. Statistical comparison of the slopes of two regression lines: a tutorial. Anal Chim Acta. 2014;838:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2014.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasserman, L. All of statistics: a concise course in statistical inference. In The American Statistician; 2004; Vol. 59, pp. 161–163&216–217 ISBN 0387402721.

- 38.Wang J, Taaffe MR. Multivariate mixtures of normal distributions: properties, random vector generation, fitting, and as models of market daily changes. INFORMS J Comput. 2015;27:193–203. doi: 10.1287/ijoc.2014.0616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asadipour M, Hassan-Zadeh V, Aryaeian N, Shahram F, Mahmoudi M. Histone variants expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21:1831–1837. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hung T, Pratt GA, Sundararaman B, Townsend MJ, Chaivorapol C, Bhangale T, Graham RR, Ortmann W, Criswell LA, Yeo GW, et al. The Ro60 autoantigen binds endogenous retroelements and regulates inflammatory gene expression. Science (80-. ) 2015;350:455–459. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamiyama R, Yoshimi R, Takeno M, Iribe Y, Tsukahara T, Kishimoto D, Kunishita Y, Sugiyama Y, Tsuchida N, Nakano H, et al. Dysfunction of TRIM21 in interferon signature of systemic lupus erythematosus. Mod Rheumatol. 2018;28:993–1003. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2018.1436028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Espinosa A, Dardalhon V, Brauner S, Ambrosi A, Higgs R, Quintana FJ, Sjöstrand M, Eloranta ML, Gabhann JN, Winqvist O, et al. Loss of the lupus autoantigen Ro52/Trim21 induces tissue inflammation and systemic autoimmunity by disregulating the IL-23-Th17 pathway. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1661–1671. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimada-Sugimoto M, Otowa T, Miyagawa T, Khor SS, Kashiwase K, Sugaya N, Kawamura Y, Umekage T, Kojima H, Saji H, et al. Immune-related pathways including HLA-DRB1*13:02 are associated with panic disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;46:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kunishita Y, Yoshimi R, Kamiyama R, Kishimoto D, Yoshida K, Hashimoto E, Komiya T, Sakurai N, Sugiyama Y, Kirino Y, et al. TRIM21 dysfunction enhances aberrant B-cell differentiation in autoimmune pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2020;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Hachicha, H.; Kammoun, A.; Mahfoudh, N.; Marzouk, S.; Feki, S.; Fakhfakh, R.; Fourati, H.; Haddouk, S.; Frikha, F.; Gaddour, L.; et al. Human leukocyte antigens-DRB1*03 is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus and anti-SSB production in South Tunisia. Int. J. Health Sci. (Qassim). 12, 21–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.De Leeuw K, Kallenberg CGM. Antibodies against c1q. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quiroz EN, Chavez-Estrada V, Macias-Ochoa K, Ayala-Navarro MF, Flores-Aguilar AS, Morales-Navarrete F, Lopez F, de la C, Escorcia LG, Musso CG, Martinez GA, et al. Epigenetic mechanisms and posttranslational modifications in systemic lupus erythematosus. Int. J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Webber D, Cao J, Dominguez D, Gladman DD, Levy DM, Ng L, Paterson AD, Touma Z, Urowitz MB, Wither JE, et al. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) genetic susceptibility loci with lupus nephritis in childhood-onset and adult-onset SLE. Rheumatol. (United Kingdom) 2020;59:90–98. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacob N, Stohl W. Cytokine disturbances in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Karnell JL, Rieder SA, Ettinger R, Kolbeck R. Targeting the CD40-CD40L pathway in autoimmune diseases: Humoral immunity and beyond. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;141:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Macedo ACL, Isaac L. Systemic lupus erythematosus and deficiencies of early components of the complement classical pathway. Front Immunol. 2016;7:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Haynes WA, Haddon DJ, Diep VK, Khatri A, Bongen E, Yiu G, Balboni I, Bolen CR, Mao R, Utz PJ, et al. Integrated, multicohort analysis reveals unified signature of systemic lupus erythematosus. JCI Insight. 2020;5(4):1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Jakez-Ocampo J, Paulín-Vera CM, Gómez-Martín D, Lima G, Vargas-Rojas MI, Llorente L, Rivadeneyra-Espinoza L, Pérez-Romano B, Calva-Cevenini G, Ruiz-Argüelles A, et al. Vß T cell receptor (TCR) genes in circulating cells of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and their healthy relatives. Gac Med Mex. 2018;154:74–79. doi: 10.24875/GMM.17002697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma K, Du W, Wang X, Yuan S, Cai X, Liu D, Li J, Lu L. Multiple functions of B cells in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Sharabi A, Tsokos GC. T cell metabolism: new insights in systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:100–112. doi: 10.1038/s41584-019-0356-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsuo T, Hashimoto M, Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Ito Y, Hikida M, Tsuruyama T, Sakai K, Yokoi H, Shirakashi M, et al. Strain-specific manifestation of lupus-like systemic autoimmunity caused by Zap70 mutation. J Immunol. 2019;202:3161–3172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Julià A, López-Longo FJ, Pérez Venegas JJ, Bonàs-Guarch S, Olivé À, Andreu JL, Aguirre-Zamorano MÁ, Vela P, Nolla JM, de la Fuente JLM, et al. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis identifies five new loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2018;20:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.He J, Ma J, Ren B, Liu A. Advances in systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis via mTOR signaling pathway. Semin Arthritis Rheum. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Beşliu AN, Pistol G, Marica CM, Bǎnicǎ LM, Chiţonu C, Ionescu R, Tǎnǎseanu C, Tamsulea I, Matache C, Stefǎnescu M. PI3K/Akt signaling in peripheral T lymphocytes from systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Roum Arch Microbiol Immunol. 2009;68:69–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilbe M, Kozyrev SV, Farias FHG, Bremer HD, Hedlund A, Pielberg GR, Seppälä EH, Gustafson U, Lohi H, Carlborg Ö, et al. Multiple changes of gene expression and function reveal genomic and phenotypic complexity in SLE-like disease. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:1-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Sui W, Hou X, Che W, Yang M, Dai Y. The applied basic research of systemic lupus erythematosus based on the biological omics. Genes Immun. 2013;14:133–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Batch effect removal results. The box plots and PCA plots related to CPN results for Hitachisoft and Illumina platforms.

Additional file 2. Significant and final parameters. The significant parameters of different platforms and the final parameters based on the mixture model in three examined signaling pathways.

Data Availability Statement

The R package of BNrich is available on Cran (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/BNrich/index.html). All gene expression data are available in the GEO database, and the raw data of signaling pathways are available in KEGG.