Abstract

The goal of this quality improvement project is to improve care planning around preferences for life-sustaining treatments (LST) and daily care to promote quality of life, autonomy, and safety for US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Community Living Center (CLC) (i.e., nursing home) residents with dementia. The care planning process occurs through partnerships between staff and family surrogate decision-makers. It is separate from but supports implementation of the LST Decision Initiative– developed by the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care – which seeks to increase the number, quality, and documentation of goals of care conversations with Veterans who have life-limiting illnesses. We will engage 4–6 VA CLCs in the Mid-Atlantic States, provide teams with audit and feedback reports, and establish learning collaboratives to address implementation concerns and support action planning. The expected outcomes are an increase in CLC residents with dementia who have a documented goals of care conversation and LST plan.

Keywords: Goals of care conversations, person-centered care, dementia, learning collaboratives, audit and feedback, palliative care

Introduction

Dementia is a progressive life-limiting illness characterized by a decline in executive function, memory, language, and decision-making ability that affects the capacity to perform activities of daily living. People with advanced dementia often are cared for in institutional settings (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016) and close to 70% of dementia-related deaths occur in nursing home (NHs) (Karlin, Visnic, McGee, & Teri, 2014). Therefore, efforts to ensure high quality NH care must address the special needs of residents with dementia.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) owns and operates 133 NHs called Community Living Centers (CLCs); one-third of CLC residents have a dementia diagnosis. The VA is committed to person-centered care for all its residents, including those with dementia and in 2008 adopted guidelines for implementing cultural transformation in CLCs (Lemke, 2012). Cultural transformation seeks to shift NHs from impersonal institutions into home-like environments that provide person-centered care (Koren, 2010; Lemke, 2012)

Person-centered care is an approach that places value on the unique qualities, interests, and needs of each individual (American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered Care, 2016). Examples of this approach include providing meaningful choices about preferences such as what to wear, when and what to eat, and what activities the resident likes to participate in (Koren, 2010). Person-centered care has been shown to positively impact residents’ wellbeing, including decreasing behavioral symptoms and reducing psychotropic medication use in dementia (Li & Porock, 2014). While experts agree that personal choices should be honored, there also is recognition that some resident preferences carry risks, such as when a resident with difficulty swallowing chooses to eat foods that are not part of the modified diet. In these cases, clinicians may be reluctant to honor these choices out of concern for the resident’s health, fear of litigation, or being cited by inspectors for negligent care (Behrens et al., 2018; Calkins, 2015; Engel, Kiely, & Mitchell, 2006).

Delivering person-centered care to individuals with dementia is particularity challenging because of their progressive inability to make decisions and communicate many of their preferences. Thus, families and healthcare teams must collaborate to make care decisions that consider the resident’s personal values, clinical situation, and best interests. In some cases, relationships between families and NH staff may become strained due to mismatched expectations, unresolved conflicts, and ineffective communication, thereby creating a significant barrier to appropriate, high quality care (Ersek, Kraybill, & Hansberry, 2000; Givens, Selby, Goldfeld, & Mitchell, 2012; Utley-Smith et al., 2009). In addition, family decision makers report inadequate support and limited communication from staff when making care decisions, which can intensify existing conflict and tension between family and staff (Givens, Kiely, Carey, & Mitchell, 2009).

An important aspect of person-centered care is to honor choices about medical therapies and, in particular, decisions about life-sustaining treatments (LST) at the end of life. Ideally, these decisions should be based on ongoing discussions among NH residents, families, and interdisciplinary team members, and be documented in the care plan (Institute of Medicine, 2014). In 2017, the VA updated its policy guidance regarding eliciting, documenting and honoring seriously ill Veterans’ goals of care and LST decisions. This program, called the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative (LSTDI) includes two key practice standards: (1) practitioners are required to initiate proactive goals of care conversations (GOCC) with seriously ill Veterans (or the Veteran’s surrogate if the Veteran lacks decision making capacity) prior to writing LST orders, and (2) practitioners are required to document these conversations and decisions, using the national standardized Veteran’s Health Administration LST progress note template and order set. Importantly, LST orders are durable; that is, they are accessible and actionable when the Veteran crosses care settings within the VA and remain in effect until they are modified based on a change in the Veteran’s goals of care and LST plan (https://www.ethics.va.gov/LST.asp) (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017; Foglia, Lowery, Sharpe, Tompkins, & Fox, 2018). The LSTDI focuses on all Veterans with serious, life-limiting illness; our project supports those with dementia living in VA-owned and operated CLCs. This paper describes the protocol, including goals and methods for this project, as well as a brief description of early implementation efforts.

Project Overview and Aims

Given the challenges in determining care preferences for CLC residents with dementia, we combined the principles of person-centered care and the LSTDI to design a clinical innovation centered on building partnerships between CLC staff and family surrogate decision-makers to enhance care planning and LST decision-making. This project, Partnership to Enhance Resident Outcomes: Collaborative Care Plans for CLC Residents with Dementia (Partnership Program) is part of a five-year quality improvement and implementation program entitled, Implementing Goals of Care Conversations with Veterans in VA Long-Term Care Settings. The larger project is described in an earlier publication (Zzzz et al., 2016).

Project aims are to:

Implement the Partnership Program at 4–6 VA CLCs;

Enhance implementation of the Partnership Program using audit with feedback and action planning technique and implementing learning collaboratives; and

Evaluate the effectiveness of the Partnership Program in increasing GOCC and documentation of preferences for LST using interrupted time-series analysis.

Methods

Description of the Partnership

To strengthen relationships between families and CLC staff and decrease the stress involved in decision-making (Ersek et al., 2000; Givens et al., 2012), we use principles of shared decision-making to engage family members in structured conversations. We ask family members and the Veteran (if able) to identify 2–3 CLC staff members that they want to participate in meetings dedicated to discussing care preferences and GOCCs. The staff partners can be anyone on the interdisciplinary team whom the family member believes know the Veteran well; including nursing assistants, activities directors, dietitians, nurses, psychologists, chaplains, nurse practitioners, physicians, or physician assistants. In this way, the Partnership Program aims to build support and trust, improve goals of care discussions, and enhance outcomes (Hanson et al., 2017; Pillemer et al., 2003).

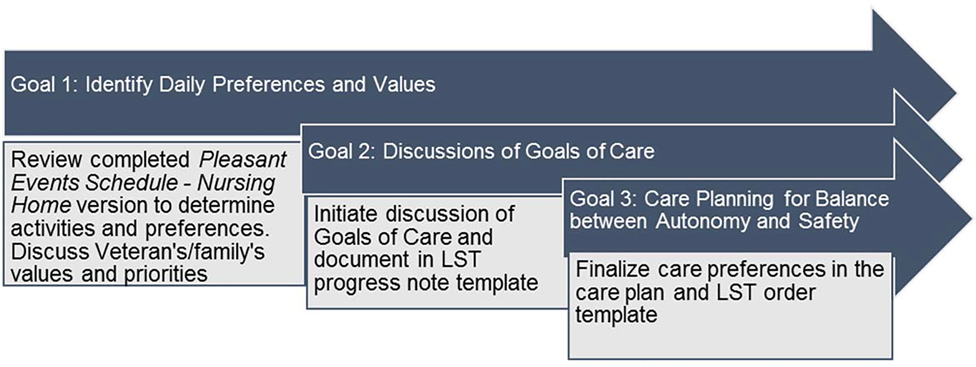

In these meetings, staff work in close collaboration with Veterans and their families to develop care plans to achieve three person-centered goals (Figure 1). The first goal is to identify daily preferences around care and activities. We use a modified version of the Pleasant Events Schedule – Nursing Home Version (PES-NH) to identify activities that the Veteran enjoys (Meeks, Shah, & Ramsey, 2009). The tool includes 30 activities (e.g., listening to music, sharing a meal with friends or family, and attending religious services) and families can write in activities not included in the list. In our project, discussing pleasant events and daily preferences offers a natural segue to exploring broader Veteran and family surrogate values and daily care priorities.

Figure 1.

CLC Partnership to Enhance Resident Outcomes - Goals of Care Conversations Framework

The second goal builds on the activities identified in the PES-NH and introduces the GOCC within the context of those activities. For instance, a family surrogate decision-maker may realize that, due to advanced cognitive impairment, there are very few meaningful activities beyond eating that the Veteran can engage in. Therefore, limiting oral intake and instead using medical-administered nutrition may not align with the pleasure gained from eating. In the Partnership Program, staff support surrogates and identify treatment options that consider the Veteran’s values and preferences.

The third goal supports the balance between autonomy and safety. For example, an older Veteran with dementia may prefer to walk without assistance around the CLC, which poses a risk for falls, wandering outside the facility, or entering other Veterans’ rooms. Determining how to maintain Veteran safety while accommodating preferences through care planning, even when the activity or behavior holds a potential risk, is based upon the Rothschild Foundation’s Process for Care Planning for Resident Choice (Calkins, 2015). Staff systematically assess the Veteran’s functional abilities and engage decision makers in discussing the potential risks and outcomes of respecting these choices as well as the potential consequences of not following these choices.

Partnership Program meetings are aligned with regularly scheduled care planning meetings whenever possible. Originally, we anticipated three separate meetings to achieve the program goals: two meetings to discuss goals around daily preferences, LST, and addressing risks and autonomy and one follow-up meeting to evaluate the care plan and make revisions. Early experiences convinced us that we needed to accomplish the first two goals in one meeting, if possible because of challenges scheduling family visits and staff availability.

Setting

To date we have recruited 5 CLCs located in the mid-Atlantic region of the US. We targeted diverse CLCs in terms of location (rural/urban) and size. Some of the CLCs include designated hospice/palliative care units, and all sites provide short stay (post-acute) and long-term care.

Participants

All new and existing CLC residents (short stay and long-term care) with a documented diagnosis of dementia and moderate to severe cognitive impairment are eligible for the Partnership Program. We identify residents with dementia using data from the VA’s Corporate Data Warehouse. Next, we review the roster of identified residents with dementia with CLC staff (typically the nurse practitioner or physician assistant, nurse, and social worker) to confirm the level of cognitive impairment, identify a family decision-maker, and prioritize residents for the Partnership Program. We prioritize those residents who have recently demonstrated significant weight loss, recurrent infections, worsening cognitive function, falls, or have undergone repeated hospitalizations. Residents can have as many Partnership Program meetings as needed to address changes in status, changing needs, and shifting goals throughout the progression of dementia.

Implementation Strategy

The Partnership Program is a multicomponent complex innovation that requires engagement from various interdisciplinary team members and administrative leaders and changes in practice, organizational processes, and staff attitudes. For these reasons, we developed an implementation strategy to support our clinical innovation (Powell et al., 2012; Powell et al., 2015). Table 1 presents the discrete implementation strategies.

Table 1:

Implementation Strategies (Powell et al., 2015)

| Strategies | CLC Partnership Program Examples |

|---|---|

| Develop educational materials (manuals, toolkits, and other supporting materials) | 1) Process maps to determine eligibility and enrollment; plan for and conduct meeting(s); and document discussion and decisions 2) Detailed protocol for guiding Partnership discussions 3) Brief “tip sheet” about conducting goals of care conversations |

| Conduct educational meetings with stakeholders to teach about the innovation | Quarterly educational webinars with CLC staff on topics important when preparing for and conducting the Partnership meetings and planning care for persons with dementia. |

| Identify and prepare champions | Discuss the roles and characteristics of the site champion (Appendix A) with stakeholders to solicit their interest in serving in this capacity. |

| Audit and provide feedback | Compile and deliver monthly feedback reports that include facility-level data on the percentage of dementia residents with a documented goals of care conversation and complete LST order set. |

| Create a learning collaborative | Site champions engage in monthly calls to review the feedback reports; share ideas and best practices; address barriers together; and develop and/or evaluate action plans to meet their goals. |

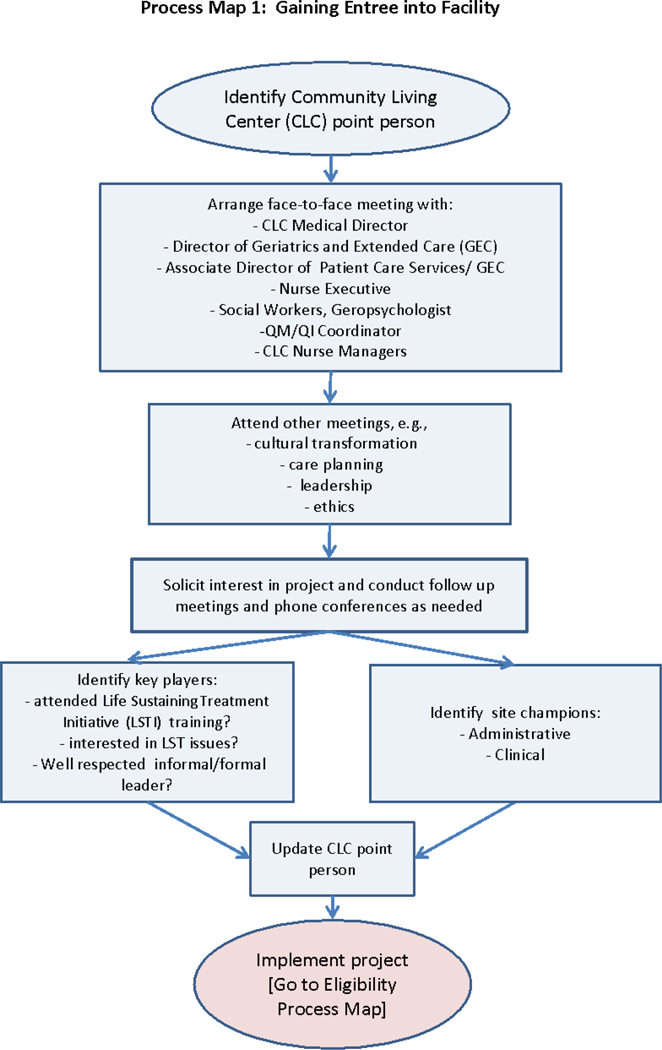

To gain entrée (Figure 2), we initially engage CLCs by identifying a point person or person(s) at the facility, often the local LSTDI coordinators and/or the Associate Chief Nurse for the CLC (analogous to a Director of Nursing in a community NH). These contacts then identify stakeholders who can influence the implementation of the LSTDI and the Partnership. Key personnel differ among facilities but typically include the CLC Medical Director, nurse managers, social workers, psychologists, physicians, advance practice nurses, and chaplains. Others who may be targeted for early engagement include the palliative care consult team members and quality improvement specialists. Next, we conduct a face-to-face site visit to meet staff and leaders who will be involved in the Partnership Program. During the meeting, we explain the program, its relationship with the LSTDI, share program materials and answer questions We also attend a regularly scheduled resident care plan meeting to better understand the local context and we explore local institutional factors that may facilitate or impact implementation (such as other VA initiatives, leadership support, and level of LSTDI engagement). Following the meeting, we write a summary of the visit, identify possible stakeholders who can serve as a site champion, and plan next steps in implementing the Partnership Program.

Figure 2.

Process map for gaining entrée

Because the Partnership Program is a quality improvement project, we largely rely on local staff for its implementation. For this reason, we recruit 1–3 local site champions whose role is to educate, advocate, and build relationships (Kirchner et al., 2012; Ploeg et al., 2010; Shea & Belden, 2016; Soo, Berta, & Baker, 2009). To identify committed, knowledgeable champions we developed a Champion Role Description which we share at the initial site visit (Appendix A). During site visits, we look for stakeholders who exemplify these characteristics, discuss the Champion role with them, and solicit their interest in serving in this capacity.

To support implementation, we distribute educational materials we have developed for CLC staff including a detailed protocol for guiding Partnership discussions. The protocol is an evidence-based standardized discussion tool to ensure consistency with preferred principles and practices of person-centered care and palliative care (Bernacki & Block, 2014; Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017; Koren, 2010; The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2013). We used an iterative process with stakeholder and expert feedback to develop the discussion tool. First, our team of geriatric and palliative care specialists drafted the tool, and two CLC clinicians with expertise in dementia and experience with GOCC provided feedback. Next, three additional geriatric experts provided suggestions for revisions. Lastly, key members of the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care, who developed and piloted the LSTDI, provided input to ensure that our project materials are consistent with and complementary to the overall initiative (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017). We then condensed the comprehensive discussion tool into a one page “tip sheet” that staff could refer to easily (Appendix B).

In addition, we offer quarterly educational live webinars for CLC staff in which focus on select topics related to dementia care, goals of care discussions, and elements of the Partnership Program. Topics were selected based on response from an online survey sent to staff at participating CLCs (Table 2). To enhance participation in the webinars, we offer continuing education credits for social workers, nurses, physicians, and psychologists and we will offer each webinar twice on different days and times. Webinars will be archived for asynchronous viewing.

Table 2.

Topics for Educational Webinars

| Clinical stages of dementia |

| Common complications in dementia (e.g. infections, swallowing difficulties, and weight loss) |

| Challenges with prognostication |

| Identifying specific decisions that many families are asked to make during the course of dementia |

| Roles and expectations of the surrogate decision maker |

| Working with multiple surrogate decision makers |

| Assisting surrogate decision makers to discuss and make difficult decisions |

| Effective ways to introduce a goals of care conversation to surrogate decision makers |

| Using the Pleasant Events Schedule to guide a goals of care conversation |

| How to talk with surrogate decision makers about life-sustaining treatment therapies |

| Discussing the risks and benefits of tube feeding and IV fluids in residents with dementia |

| Roles of interdisciplinary team members in care planning around daily preferences |

| Discussing the risks and benefits of hospitalization for residents with dementia |

| Discussing antibiotic use for residents with dementia |

| Dealing with conflict when surrogates and staff don’t agree about the goals of care |

| Discussing the risks and benefits of CPR for residents with dementia |

| Comfort Care: What does it mean and how do we deliver it to residents with dementia? |

| Other (Specify) |

We use learning collaboratives to bring our multidisciplinary CLC teams together to promote the delivery of the Partnership Program. During learning collaboratives, participants support each other by sharing knowledge, successes, and ideas and strategies to foster quality improvement practices (Gillespie et al., 2016). Our learning collaboratives integrate features of quality improvement collaboratives that participants report as most helpful: a focus on data; team cohesion; organizational context; collaborative faculty or facilitators for the collaborative; and creation of a change package (Hulscher, Schouten, Grol, & Buchan, 2013; Nembhard, 2009). For example, we use a web-based “toolkit” (change package) that includes practice changes integral to the Partnership Program, guidance on conducting and documenting GOCC, sample care plans, and materials for arranging and conducting Partnership meetings.

Audit and feedback is a widely used strategy to improve professional practice either on its own or as a component of multifaceted quality improvement interventions (Ivers et al., 2012). It involves aggregating clinical and other performance data and trending the data over time. The aggregated data summary is provided to individual practitioners, teams, or healthcare organizations. We compile and deliver feedback reports monthly via e-mail to each site (Ivers et al., 2012; Sales, Schalm, Baylon, & Fraser, 2014). Reports present CLC facility-level data covering the percentage of Veterans with dementia having a GOCC documented on the LST progress note template and order set. We engage CLC site staff in monthly calls during which time they review the feedback reports and develop and/or evaluate action plans to meet implementation goals.

In the context of feedback interventions, action planning refers to planned, systematic approaches to responding to gaps in performance (Ivers et al., 2012). Action planning is generally an important component of audit and feedback and learning collaboratives, which routinely use data fed back for the purpose of generating actions to improve quality of care in specific ways. Our learning collaboratives support action planning in association with feedback reports. CLC teams use action planning to test and implement changes in their practice and participants share approaches to overcoming implementation barriers that can contribute to other CLC teams’ action planning.

Evaluation

Our primary outcome measure is documentation of a GOCC and the resulting LST plan using the standardized progress note template entitled “Life-Sustaining Treatment.” The LST template (Table 3) consists of eight fields, four of which are mandatory (decision making capacity; patient’s goals of care; oral informed consent for the life-sustaining treatment plan; and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) status).

Table 3.

Life Sustaining Treatment Decisions Template

| *1. Does the patient have capacity to make decisions about life-sustaining treatments? |

| 2. Who is the person authorized under VA policy to make decisions for the patient if/when the patient loses decision-making capacity? |

| 3. Have you reviewed available documents that reflect the patient’s wishes regarding life-sustaining treatments? Examples: advance directives, state-authorized portable orders (e.g., POLST, MOST), life-sustaining treatment notes/orders. |

| 4. Does the patient (or surrogate) have sufficient understanding of the patient’s medical condition to make informed decisions about life-sustaining treatments? |

|

*5. What are the patient’s goals of care? • Patient’s goals of care in their own words, or as stated by the surrogate: • To be cured of:__________________________ • To prolong life • To improve or maintain function, independence, quality of life • To be comfortable • To obtain support for family/caregiver • To achieve life goals, including: ________________________ |

| 6. What is the current plan for use of life-sustaining treatments? • FULL SCOPE OF TREATMENT in circumstances OTHER than cardiopulmonary arrest. • Limit life-sustaining treatment • No life-sustaining treatment in circumstances OTHER that cardiopulmonary arrest. *CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION (CPR) ○ Full Code: Attempt CPR ○ DNAR/DNR: Do not attempt CPR ○ DNAR/DNR with exception: ONLY attempt CPR during the following procedure:_____________________. • Artificial Nutrition • Artificial Hydration • Mechanical Ventilation • Transfers between Levels of Care • Limit other life-sustaining treatment as follows (e.g., blood products, dialysis) |

| 7. Who participated in this discussion? |

| *8. Who has given oral informed consent for the life-sustaining treatment plan outlined above? |

indicates required field

Using interrupted times series analysis, we will test for significant changes in the percent of CLC residents with dementia at the facility who have a completed LST progress note template. We also will examine and quantify the percentage of non-required fields for each complete (4 mandatory fields documented) LST template to determine comprehensiveness of GOCC (Bernacki & Block, 2014; Hickman, Nelson, Smith-Howell, & Hammes, 2014).

We will aggregate data at the facility level to compare trends in LST documentation between participating facilities and a matched sample of CLCs that did not participate. To identify matched, control sites, we used principal components analysis to create scores for each CLC, with separate principal components for facility characteristics, resident demographics, and case-mix. Separate scores were used to control for strong matching on one set of variables but poor matching on another. We also created a separate principal component for the binary variables for statistical reasons; they are treated differently in principal components analysis. We then used these four scores to calculate the Euclidean distance between the intervention sites and all other CLCs, and chose the 2 closest matches for each study site, not allowing duplicates. We used this method because it ensures better matching. The full data analytic plan is described in a previously published protocol paper (Zzzz et al., 2016).

We also will solicit staff and surrogate perspectives on (a) challenges in implementing the intervention; (b) satisfaction with the intervention; and (c) strategies that promoted its adoption. We expect these data will help us understand how to improve conducting GOCC with surrogate decision makers. CLC champions and staff who participated in Partnership meetings from the participating facilities will be invited to one of three semi-structured focus group interviews via audio or videoconference. We will attempt to recruit groups that include diverse representation from the interdisciplinary team. We will begin the interviews with a statement explaining the purpose of the focus group and a reminder that no identifiable information will be linked to the transcripts. The interview guide will prompt participants to report their perceptions about barriers and facilitators to implementing the Partnership Program and solicit examples of how the Partnership Program model helped them achieve the goals of the LSTDI. We also will ask them to suggest ways to improve the program.

We also will interview 8–10 surrogate decision makers who participated in the Partnership Program to better understand their experience with the intervention components. For example, families will be asked how completing the Pleasant Events Schedule was helpful in identifying preferences for daily care and activities; if they felt better supported making decisions; and how the information discussed during the Partnership meeting made them feel.

We will analyze the data using directed content analysis because we have identified our key concepts/categories a priori: Challenges, Facilitators, and Opportunities for Improvement (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). After initial coding by one team member, our entire team will meet to review coding and develop and define categories and subcodes. Two team members will continue coding the data in its entirety. During weekly analytic meetings, the team will discuss any disagreements in coding, as well as refinements and additions to the initial categories and subcodes until consensus on final coding is reached.

Results and Discussion: Early Implementation Experiences

We piloted the protocol and standardized discussion tool for the CLC Partnership with four family/surrogate decision makers in two participating CLCs; the first author, an experienced geriatric/palliative care nurse practitioner and co-lead on the project role modelled the Partnership. The pilot sessions served as a training mechanism for staff to observe and actively participate in GOCC. In addition, the sessions provided an opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness of the process maps in outlining the identification of appropriate Veterans and their surrogates, contacting the surrogate and scheduling the partnership meeting and proper documentation of the meeting and conducting subsequent following-up meetings.

As per protocol, the surrogates were asked to identify a staff member they would like to work with to develop the Partnership Program care plan. Family members chose a diverse group of clinicians, including licensed practical nurses, certified nursing assistants, social workers, psychologists, and nurses. Family members chose partners whom they trusted and who possessed long-standing, in-depth understanding about the resident. In addition to staff selected by the family, other team members present at the meetings included nurse managers; recreational therapists; resident assessment coordinators; registered dieticians; nurse practitioners and/or physician assistants; social workers; and in one meeting the hospice medical director. Each of the four partnership meetings highlighted the importance of addressing the project-level goals. We describe below some salient components of two of the meetings that were conducted.

Mr. A: Enhancing daily preferences

Mr. A, a CLC resident for approximately 5 years with moderate cognitive impairment enjoys participating in regularly scheduled recreational events. However, when activities are not taking place, he is frequently placed near the nurses’ station so that he can be monitored for safety as he is considered at risk for falls. During the first CLC Partnership meeting, his daughter expressed that she would like to see her father participate in more activities. One of the items that the daughter identified on the PES-NH was attendance at religious services. The daughter described how important spirituality was to her father and, although he attended religious services at the CLC, she asked if he could attend services at the chapel located within the VA acute care hospital located across the street. The CLC social worker suggested that the staff could make arrangements for a van and staff member to take him to the services at the hospital. This example highlights that, even for residents who have been at the CLC for some time, it is worth revisiting preferences for daily activities (Van Haitsma et al., 2014).

Mr. B: Balancing autonomy and risk

Mr. B, a CLC resident with advanced dementia and dysphagia, was prescribed a pureed diet. Despite his advanced illness and limited ability to swallow effectively, Mr. B expressed his displeasure with his diet, therefore his family wanted him to receive a regular diet (even if it meant an increased risk of choking or aspiration). The staff were concerned about the increased choking risk and subsequent events (such as respiratory arrest) because Mr. B’s plan of care included the use of all LSTs; a treatment decision that seemed at odds with a focus on comfort and enjoyment considering his advanced dementia and dysphagia. Discussion in the Partnership meeting focused on the family members’ understanding of the risks and benefits of CPR and artificial ventilation in advanced dementia and the recognition that allowing Mr. B to eat a regular diet would increase the risk of choking, aspiration, pneumonia, and possible cardiac arrest. This line of questioning revealed the family member’s belief that, by changing the Veteran’s medical orders to “do not resuscitate,” he may be denied other types of LSTs such as antibiotics. As a result of the Partnership meeting, the staff set up another meeting with the family and the Veteran’s physician in the CLC to provide more information about LST decisions, determine how to honor this diet choice, mitigate risks, and review alternatives. Using the Rothschild’s approach, the team aimed to maximize Mr. B’s well-being.

Challenges to implementation

After the project started, we found several challenges to carrying out the Partnership Program. First, arranging a time to hold Partnership meetings was difficult due to staff schedules and surrogate time restraints. Therefore, we started to hold Partnership meetings during regularly scheduled care planning meetings when the surrogates were already in attendance. This was well received because the interdisciplinary team was preassembled and prepared to discuss the Veteran’s care, goals, and LST decisions with the surrogates. Second, Champions ran into difficulty with staff buy-in to the program and we found that we needed to provide ongoing consultation through monthly “check-in” calls, which allow Champions to discuss barriers, receive coaching, and identify strategies associated with successful implementation of the intervention. Lastly, staff turnover and competing responsibilities have resulted in our need to identify new Champions and provide continuous training. While time consuming, we find these tasks essential for the success of the project.

In conclusion, this quality improvement project is designed to improve GOCC and care planning around preferences for LST and daily care to promote quality of life, autonomy, and safety for VA CLC residents with dementia. The care planning process takes place through partnerships between CLC staff and family surrogate decision-makers who work together to design and deliver Veteran-centric care. Although these tools and resources were designed for the VA, general LSTDI resources are freely available on the internet (https://www.ethics.va.gov/LST.asp). Specific Partnership Program resources will be added to the website in 2020, and are directly available from the authors.

Throughout the project, we will continue to hold learning collaboratives to review feedback reports and develop and support action plans and conduct quarterly continuing education webinars. We will use mixed methods to evaluate outcomes including documentation of a GOCC on the LST progress note template and order set as well as barriers and facilitators to implementation. We expect this project will have an impact on CLC clinical practice and Veteran and family outcomes by leveraging evidence-based elements and resources within a framework to identify and act upon Veterans’ preferences for care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) [QUE 15-288]. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval

The Corporal Michael J. Crescenz (Philadelphia) Veterans Affairs Medical Center Research and Development Committee reviewed this protocol and deemed it quality improvement and not human subjects research.

References

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered Care. (2016). Person-centered care: A definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc, 64(1), 15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens L, Van Haitsma K, Brush J, Boltz M, Volpe D, & Kolanowski AM (2018). Negotiating risky preferences in nursing homes: A case study of the Rothschild Person-Centered Care Planning Approach. J Gerontol Nurs, 44(8):11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacki RE, & Block SD (2014). Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med, 174(12), 1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins MS, K.; Brush J; Mayer R (2015). A Process for Care Planning for Resident Choice. Retrieved from http://atomalliance.org/download/a-process-for-care-planning-resident-choice/

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2017). Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions: Eliciting, Documenting and Honoring Patient’s Values, Goals, And Preferences. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/publications.cfm?pub=2

- Engel SE, Kiely DK, & Mitchell SL (2006). Satisfaction with end-of-life care for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc, 54(10), 1567–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersek M, Kraybill BM, & Hansberry J (2000). Assessing the educational needs and concerns of nursing home staff regarding end-of-life care. J Gerontol Nurs, 26(10), 16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foglia MB, Lowery J, Sharpe VA, Tompkins P, & Fox E (2018). A Comprehensive approach to eliciting, documenting, and honoring patient wishes for care near the end of life: The Veterans Health Administration’s Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. Advance online publication doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie SM, Olsan T, Liebel D, Cai X, Stewart R, Katz PR, & Karuza J (2016). Pioneering a nursing home quality improvement learning collaborative: A case study of method and lessons learned. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 17(2), 136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens JL, Kiely DK, Carey K, & Mitchell SL (2009). Healthcare proxies of nursing home residents with advanced dementia: Decisions they confront and their satisfaction with decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc, 57(7), 1149–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens JL, Selby K, Goldfeld KS, & Mitchell SL (2012). Hospital transfers of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc, 60(5), 905–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson LC, Zimmerman S, Song MK, Lin FC, Rosemond C, Carey TS, & Mitchell SL (2017). Effect of the Goals of Care Intervention for Advanced Dementia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(1), 24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R, Caffrey C, Rome V, & Lendon J (2016). Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: Data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. Vital Health Stat 3(38), x–xii; 1–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Smith-Howell E, & Hammes BJ (2014). Use of the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment program for patients being discharged from the hospital to the nursing facility. J Palliat Med, 17(1), 43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulscher ME, Schouten LM, Grol RP, & Buchan H (2013). Determinants of success of quality improvement collaboratives: What does the literature show? BMJ Qual Saf, 22(1), 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2015). Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 10.17226/18748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, … Oxman AD (2012). Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev(6), CD000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin BE, Visnic S, McGee JS, & Teri L (2014). Results from the multisite implementation of STAR-VA: a multicomponent psychosocial intervention for managing challenging dementia-related behaviors of veterans. Psychol Serv, 11(2), 200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner JE, Parker LE, Bonner LM, Fickel JJ, Yano EM, & Ritchie MJ (2012). Roles of managers, frontline staff and local champions, in implementing quality improvement: Stakeholders’ perspectives. J Eval Clin Pract, 18(1), 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren MJ (2010). Person-centered care for nursing home residents: the culture-change movement. Health Aff (Millwood), 29(2), 312–317. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke S (2012). Veterans Health Administration: A model for transforming nursing home care. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 26(1–3), 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Li J, & Porock D (2014). Resident outcomes of person-centered care in long-term care: A narrative review of interventional research. Int J Nurs Stud, 51(10), 1395–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks S, Shah SN, & Ramsey SK (2009). The Pleasant Events Schedule - nursing home version: A useful tool for behavioral interventions in long-term care. Aging Ment Health, 13(3), 445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nembhard IM (2009). Learning and improving in quality improvement collaboratives: Which collaborative features do participants value most? Health Serv Res, 44(2 Pt 1), 359–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ, Henderson CR Jr., Meador R, Schultz L, Robison J, & Hegeman C (2003). A cooperative communication intervention for nursing home staff and family members of residents. Gerontologist(2), 96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploeg J, Skelly J, Rowan M, Edwards N, Davies B, Grinspun D, … Downey A (2010). The role of nursing best practice champions in diffusing practice guidelines: A mixed methods study. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs, 7(4), 238–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Bunger AC, … York JL (2012). A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev, 69(2), 123–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, … Kirchner JE (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci, 10, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zzzzz et al. (2016). Implementing goals of care conversations with veterans in VA long-term care setting: a mixed methods protocol. Implement Sci, 11(1), 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales AE, Schalm C, Baylon MA, & Fraser KD (2014). Data for improvement and clinical excellence: report of an interrupted time series trial of feedback in long-term care. Implement Sci, 9, 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea CM, & Belden CM (2016). What is the extent of research on the characteristics, behaviors, and impacts of health information technology champions? A scoping review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, 16, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soo S, Berta W, & Baker GR (2009). Role of champions in the implementation of patient safety practice change. Healthc Q, 12 Spec No Patient, 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. (2013). Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 3rd edition. Retrieved from http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org

- Utley-Smith Q, Colón-Emeric CS, Lekan-Rutledge D, Ammarell N, Bailey D, Corazzini K, … Anderson RA (2009). The nature of staff - family interactions in nursing homes: Staff perceptions. Journal of aging studies, 23(3), 168–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Haitsma K, Abbott K, Heid AR, Carpenter B, Curyto K, Kleban M, … Spector A (2014). The consistency of self-reported preferences for everyday living: Implications for person centered care delivery. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 40(10), 34–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.