Abstract

Each year millions of pilgrims perform the annual Hajj from more than 180 countries around the world. This is one of the largest mass gathering events and may result in the occurrence and spread of infectious diseases. As such, there are mandatory vaccinations for the pilgrims such as meningococcal vaccines. The 2019 annual Hajj will take place during August 8–13, 2019. Thus, we review the recommended and mandated vaccinations for the 2019 Hajj and Umrah. The mandatory vaccines required to secure the visa include the quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine for all pilgrims, while yellow fever, and poliomyelitis vaccines are required for pilgrims coming from countries endemic or with disease activity. The recommended vaccines are influenza, pneumococcal, in addition to full compliance with basic vaccines for all pilgrims against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, measles, and mumps. It is imperative to continue surveillance for the spread of antimicrobial resistance and occurrence of all infectious diseases causing outbreaks across the globe in the last year, like Zika virus, MDR-Typhoid, Nipah, Ebola, cholera, chikungunya and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus.

Keywords: Hajj, pilgrimage, mass gathering, vaccine requirements, Saudi Arabia

1. INTRODUCTION

Each year millions of people from more than 180 countries gather to perform the annual Hajj pilgrimage in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. The Hajj season occurs at a fixed time each year from 8th to 13th day of the 12th month (Dhu al-Hijjah) in the Islamic calendar [1]. The Islamic/Lunar calendar is 11 days shorter than the Gregorian calendar [1]. This year the annual Hajj is expected to take place during August 8–13, 2019. The annual Hajj is one of the largest recurring mass gathering in the world and is the most studied mass gathering [1–8]. The number of pilgrims traveling to Saudi Arabia is based on the number of Muslims in each country and is calculated as one pilgrim per 1000 Muslims in the specific country [7]. The annual pilgrimage number had increased from 58,584 in 1920 to 3,161,573 in 2012 and of those pilgrims in 2012 about 1,752,932 were international pilgrims coming from outside Saudi Arabia [5]. The international pilgrims arrive to Saudi Arabia mainly by air and others may travel via land [4,8,9]. In previous years, there were occurrences of Hajj-related outbreaks [10–14] such as the 1987 international meningococcal disease outbreak caused by Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A [15–17], and serogroup W135 [18], and the 2000–2001 N. meningitidis outbreak [14,15]. Thus, the annual Hajj requirements are updated annually in response to the occurrence of newly emerging infectious diseases such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [1,6,19] and the occurrence of international outbreaks such as Ebola [7,8]. The recommended vaccinations for the Hajj are updated annually [6–9,20]. The 2019 required and recommended vaccinations were issued by the Saudi Ministry of Health [20]. Here, we summarize the 2019 Hajj mandatory and recommended vaccinations and discuss the possible impact of newly occurring outbreaks internationally, one of the most globally spread outbreaks is measles [21–23].

2. MANDATORY AND RECOMMENDED VACCINATION FOR THE 2019 HAJJ

The recommended and mandatory vaccinations for pilgrims are summarized in Table 1. These vaccines include mandatory vaccinations (meningococcal vaccination, poliomyelitis vaccine, and yellow fever vaccine); recommended vaccination (influenza), and other immunization against vaccine-preventable diseases (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, measles and mumps).

Table 1.

Required and recommended vaccination for the 2019 Hajj season

| Pilgrims coming from | Vaccination | |

|---|---|---|

| Yellow fever | Africa: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sudan, South Sudan, Togo and Uganda |

|

| South and Central America: Argentina, Venezuela, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Bolivia, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago | ||

| Meningococcal vaccine (polysaccharide or conjugate) | (a) Any visitor | (a) Vaccination with ACYW135: vaccine within the last 3 years (polysaccharide vaccines); within 5 years (conjugate vaccines), and >10 days before arriving Saudi Arabia |

| (b) Visitors from African meningitis belt: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal and Sudan | (b) ACYW135 vaccine (as above) | |

| (c) Pilgrims from within Saudi and the Hajj workers: all citizens and residents of Medina and Makkah | (c) ACYW135 vaccine (as above) | |

| Poliomyelitis | (a) Pilgrims from areas with active poliovirus transmission of a wild or vaccine-derived poliovirus: Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan | (a) At least one dose of bivalent oral polio vaccine (bOPV), or inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), in the last 12 months and ≥ 4 weeks prior to departure |

| (b) Countries at risk of polio reintroduction: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Guinea, Laos People’s Democratic Republic, Madagascar, Myanmar, Niger, and Ukraine | (b) As above | |

| (c) Countries which remain vulnerable to Polio: Afghanistan, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Syria, Myanmar, Yemen and Somalia | (c) As above and additionally those pilgrims will receive 1 dose of OPV on arrival to Saudi Arabia | |

| Seasonal influenza | All pilgrims (internal and international) and all health-care workers in the Hajj area | A recommendation |

| Cholera | No specific vaccine requirement |

2.1. Meningococcal Vaccination

The carriage rate of N. meningitidis was 3.4% arriving pilgrims [24]. The requirement of a bivalent A and C meningococcal vaccine for pilgrims came in effect in 1987 after the occurrence of meningococcal outbreaks [8], and the quadrivalent (A,C,Y, W135) vaccine became a requirement May 2001 [25,26] after the occurrence of two meningococcal outbreaks with serogroup W135 in 2000 and 2001 [27–29]. Subsequent to the introduction of the meningococcal vaccination during the Hajj, the mean numbers of cases per year of Hajj-related invasive meningococcal disease decreased from 13 in 1995 to 2 cases in 2011 [26]. A meningococcal vaccine is required for all pilgrims and specifically a conjugate vaccine is required for healthcare workers working at the Hajj. In a previous study, 97-100% of international pilgrims had the recommended meningococcal vaccination with the quadrivalent vaccine [24]. In recent years, N. meningitidis serogroup B vaccine became available [30] and a study showed that the majority of 3.4% of pilgrims with N. meningitidis carriage were due to serogroup B [24]. However, it was felt that this vaccine is not required due to insufficient data from the Hajj [24]. In previous years, ciprofloxacin (500 mg tablets) was administered as an oral chemoprophylaxis to pilgrims arriving from the African meningitis belt [6,8,15,31,32]. These recommendations were based on studies showing the carriage rate of N. meningitidis of 3.6% and 1.4% in a paired cohort of pilgrims from high endemic countries at arrival and departure, respectively [24]. However, the role of ciprofloxacin in eradicating the carrier sates of N. meningitidis showed a rate of 5.2% before and 4.6% after the Hajj following a single dose of ciprofloxacin (p = 0.65) [33]. The carriage rate of N. meningitidis among returning pilgrims varies from 0% to 0.6% [33–36]. Thus, ciprofloxacin was not adopted as a strategy post-Hajj and the current recommendations from the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia reserve the option to administer prophylactic antibiotics to some travelers at the points of entry if deemed necessary [20].

2.2. Poliomyelitis

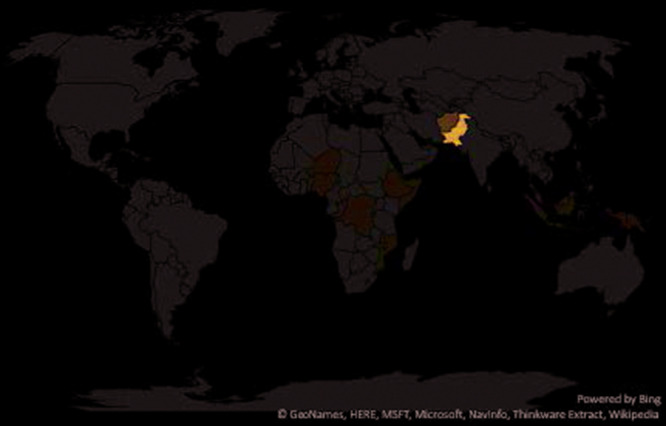

Although poliomyelitis is a vaccine preventable disease, its eradication is delayed by the potential spread by international travelers [37]. The number of poliomyelitis in 2018 and 2019 across many countries is shown in Figure 1, data were based on the Polio Global Eradication Initiative [38]. According to the World Health Organization, Saudi Arabia had been poliomyelitis free since October, 1995 [39]. However, a case was reported on January 24, 1998, and the virus was closely related to a strain in Afghanistan/Pakistan, and another case in 2004 was in a Sudanese child [39]. Based on a mathematical model, there is a possibility of 21 importations of poliovirus into Saudi Arabia via Hajj pilgrims [40]. Of the total 1,722,372 pilgrims in 2017, 25% were from polio priority countries [41]. It is also important to note that poliomyelitis is a disease of children <5 years old and the number of those among pilgrims is very small [42]. The Hajj requirement for people coming from polio priority countries is summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1. Compliance with this requirement was 99.5% among pilgrims from at-risk countries: Pakistan, India, Nigeria, and Afghanistan [19].

Figure 1.

A world map showing countries where pilgrims are required to have poliomyelitis vaccination.

2.3. Yellow Fever Vaccinations

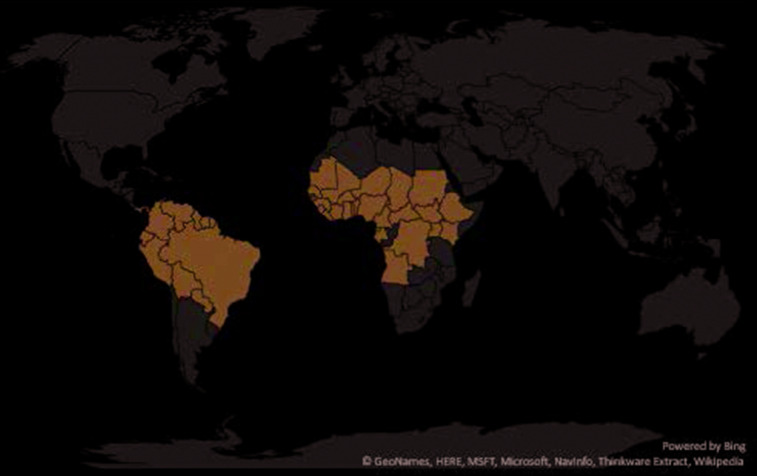

Yellow fever vaccines are required by the International Health Regulations (IHR) for travelers from areas at risk of yellow fever transmission [43]. According to Annex 7 of the IHR in 2005, the WHO World Health Assembly approved lifelong protection of yellow fever vaccination and validity begins 10 days after the date of vaccination [44]. The updated international travel and health lists the following countries as at risk of yellow fever [45] is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A map showing the updated international travel and health lists of countries at risk of yellow fever.

2.4. Influenza Vaccinations

The prevalence of the occurrence of influenza virus among pilgrims varies depending on the study type and the diagnostic tool used with a range of 0–28.6% [36,46–62]. Influenza vaccine decreases development of influenza like-illness among pilgrims [63]. It is recommended that Hajj and Umrah pilgrims receive seasonal influenza vaccination [64]. However, influenza vaccine is currently not obligatory for pilgrims and thus compliance rate was 7.1–100% [63,65,66].

2.5. Pneumococcal Disease

There are limited data on the occurrence of pneumococcal disease among pilgrims. In a systematic review, the carriage of pneumococcal vaccine serotype was higher in the post-Hajj period compared with the pre-Hajj period [67] and the available data do not support a firm recommendation for the Streptococcus pneumoniae vaccination. However, it is known that 7–37% of pilgrims are older adults (>65 years old), and the compliance rate with S. pneumoniae vaccination is 5% among pilgrims [68].

2.6. Newly Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases and the Risk during the Annual Hajj

The MERS-CoV was described only few weeks before the 2012 Hajj season and created a significant fear of the spread of this newly discovered virus [47,56,69]. Multiple studies examined departing pilgrims with no evidence of MERS transmission [19,36,50,52,53,60,62,69–74]. However, there were few reports of MERS-CoV cases associated with the mini-Hajj, the Umrah [75,76]. Currently, pilgrims are advised to observe hand hygiene and follow cough etiquette and avoid contacts with camels [8]. This is also important to avoid the occurrence of diarrheal diseases. Few studies described the incidence and etiology of diarrhea among pilgrims [5]. In the past, cholera caused multiple outbreaks during the Hajj and the last ones were after the Hajj in 1984–86 and 1989 [42,77]. Contributing factors to the development of diarrheal disease are inadequate food hygiene, asymptomatic carriers of bacteria, and mass food preparation.

2.7. Measles and Rubella

There are multiple recent outbreaks of measles around the world. Since 2017, the number of measles cases increased 300% in the first 3 months of 2019 and multiple outbreaks in the United States [78–81]. There were reports of the occurrence of measles outbreak in relation to mass gathering events such as an international youth sporting event in USA resulting in cases in eight states [23], and the occurrence of measles among attendees of a church gathering and in the 2010 Taizé festival in France [21,22]. However, till date there is no reported outbreaks of measles during the Hajj. Few studies confirmed the occurrence of measles in relation to other mass gatherings and had been reported and recently reviewed [82]. The Saudi Ministry of Health strongly recommends that pilgrims update their immunization [1].

3. CONCLUSION AND COMMENTS

As usual, the Saudi Ministry of Health continues to observe the occurrence of any disease outbreaks around the world and issues recommendations for Hajj vaccinations and preventive measures [1,8]. There are mandated vaccines and additional recommended vaccines based on the available data and risk of spread of any disease. It is a cumulative experience from each Hajj and the dedication to provide a safe and healthy pilgrimage that draw on these guidelines and drive the annual planning for each Hajj [5,83,84].

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

All authors have no funding.

REFERENCES

- [1].Al-Tawfiq JA, Gautret P, Memish ZA. Expected immunizations and health protection for Hajj and Umrah 2018 —an overview. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2017;19:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gautret P, Benkouiten S, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Hajj-associated viral respiratory infections: a systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:92–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gautret P, Benkouiten S, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. The spectrum of respiratory pathogens among returning Hajj pilgrims: myths and reality. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:83–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA. Hajj: preparations underway. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:E331. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(13)70079-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Memish ZA, Zumla A, Alhakeem RF, Assiri A, Turkestani A, Al Harby KD, et al. Hajj: infectious disease surveillance and control. Lancet. 2014;383:2073–82. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60381-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Mass gathering medicine: 2014 Hajj and Umra preparation as a leading example. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;27:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA. The Hajj in the time of an ebola outbreak in West Africa. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014;12:415–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. The Hajj: updated health hazards and current recommendations for 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:20295. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23078811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Mass gatherings and infectious diseases: prevention, detection, and control. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26:725–37. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lucidarme J, Scott KJ, Ure R, Smith A, Lindsay D, Stenmark B, et al. An international invasive meningococcal disease outbreak due to a novel and rapidly expanding serogroup W strain, Scotland and Sweden, July to August 2015. Eurosurveillance. 2016;21:30395. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es.2016.21.45.30395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wilder-Smith A, Goh KT, Barkham T, Paton NI. Hajj-associated outbreak strain of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup W135: estimates of the attack rate in a defined population and the risk of invasive disease developing in carriers. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:679–83. doi: 10.1086/367858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Aguilera J-F, Perrocheau A, Meffre C, Hahné S. Outbreak of serogroup W135 meningococcal disease after the Hajj pilgrimage, Europe, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:761–7. doi: 10.3201/eid0808.010422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dull PM, Abdelwahab J, Sacchi CT, Becker M, Noble CA, Barnett GA, et al. Neisseria meningitidis Serogroup W-135 Carriage among US travelers to the 2001 Hajj. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:33–9. doi: 10.1086/425927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Al-Tawfiq JA, Clark TA, Memish ZA. Meningococcal disease: the organism, clinical presentation, and worldwide epidemiology. J Travel Med. 2010;17:3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Al-Gahtani YM, El Bushra HE, Al-Qarawi SM, Al-Zubaidi AA, Fontaine RE. Epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of meningococcal meningitis in Makkah (Mecca), Saudi Arabia, 1992. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;115:399–409. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800058556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Moore PS, Reeves MW, Schwartz B, Gellin BG, Broome CV. Intercontinental spread of an epidemic group A Neisseria meningitidis strain. Lancet. 1989;334:260–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Novelli VM, Lewis RG, Dawood ST. Epidemic group A meningococcal disease in Haj pilgrims. Lancet. 1987;330:863. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lingappa JR, Al-Rabeah AM, Hajjeh R, Mustafa T, Fatani A, Al-Bassam T, et al. Serogroup W-135 meningococcal disease during the Hajj, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:665–71. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.020565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Memish ZA, Assiri A, Almasri M, Alhakeem RF, Turkestani A, Al Rabeeah AA, et al. Prevalence of MERS-CoV nasal carriage and compliance with the Saudi health recommendations among pilgrims attending the 2013 Hajj. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:1067–72. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Saudi Ministry of Health Health Regulations - 2019/1440H-Hajj and Umrah Health Regulations. n.d. https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Hajj/HealthGuidelines/HealthGuidelinesDuringHajj/Pages/HealthRequirements.aspx (accessed June 22, 2019).

- [21].Parker AA, Staggs W, Dayan GH, Ortega-Sánchez IR, Rota PA, Lowe L, et al. Implications of a 2005 measles outbreak in Indiana for sustained elimination of measles in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:447–55. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa060775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pfaff G, Lohr D, Santibanez S, Mankertz A, van Treeck U, Schonberger K, et al. Spotlight on measles 2010: measles outbreak among travellers returning from a mass gathering, Germany, September to October 2010. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:pii: 19750. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21172175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chen T-H, Kutty P, Lowe L, Hunt E, Blostein J, Espinoza R, et al. Measles outbreak associated with an international youth sporting event in the United States, 2007. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:794–800. doi: 10.1097/inf.0b013e3181dbaacf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Almasri M, Azhar EI, Yasir M, Al-Saeed MS, et al. Neisseria meningitidis nasopharyngeal carriage during the Hajj: a cohort study evaluating the need for ciprofloxacin prophylaxis. Vaccine. 2017;35:2473–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Borrow R. Meningococcal disease and prevention at the Hajj. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2009;7:219–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.05.003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19717104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Memish Z, Al Hakeem R, Al Neel O, Danis K, Jasir A, Eibach D. Laboratory-confirmed invasive meningococcal disease: effect of the Hajj vaccination policy, Saudi Arabia, 1995 to 2011. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:pii: 20581. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.37.20581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Memish ZA, Venkatesh S, Ahmed QA. Travel epidemiology: the Saudi perspective. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:96–101. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00364-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mayer LW, Reeves MW, Al-Hamdan N, Sacchi CT, Taha M-K, Ajello GW, et al. Outbreak of W135 meningococcal disease in 2000; not emergence of a new W135 strain but clonal expansion within the electophoretic type-37 complex. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1596–605. doi: 10.1086/340414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Issack MI, Ragavoodoo C. Hajj-related Neisseria meningitidis serogroup w135 in Mauritius. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:332–4. doi: 10.3201/eid0803.010372. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11927036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Folaranmi T, Rubin L, Martin SW, Patel M, MacNeil JR. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in persons aged ≥10 years at increased risk for serogroup B meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:608–12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26068564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Memish ZA. Meningococcal disease and travel. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:84–90. doi: 10.1086/323403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shibl A, Tufenkeji H, Khalil M, Memish Z. Consensus recommendation for meningococcal disease prevention for Hajj and Umra pilgrimage/travel medicine. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19:389–92. doi: 10.26719/2013.19.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Alborzi A, Oskoee S, Pourabbas B, Alborzi S, Astaneh B, Gooya MM, et al. Meningococcal carrier rate before and after hajj pilgrimage: effect of single dose ciprofloxacin on carriage. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:277–82. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18561718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wilder-Smith A, Barkham TMS, Chew SK, Paton NI. Absence of Neisseria meningitidis W-135 electrophoretic Type 37 during the Hajj, 2002. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:734–7. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.020725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wilder-Smith A, Barkham TMS, Earnest A, Paton NI. Acquisition of W135 meningococcal carriage in Hajj pilgrims and transmission to household contacts: prospective study. BMJ. 2002;325:365. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7360.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Memish ZA, Assiri A, Turkestani A, Yezli S, Al Masri M, Charrel R, et al. Mass gathering and globalization of respiratory pathogens during the 2013 Hajj. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:571.e1–571.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mushtaq A, Mehmood S, Ur Rehman MA, Younas A, Ur Rehman MS, Malik MF, et al. Polio in Pakistan: social constraints and travel implications. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015;13:360–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Polio GLobal Eradication Initiative Polio Today. n.d. http://polioeradication.org/polio-today/polio-now/this-week/ (accessed June 23, 2019).

- [39].WHO EMRO Polio eradication initiative. n.d. http://www.emro.who.int/polio/countries/saudi-arabia.html (accessed June 23, 2019).

- [40].Wilder-Smith A, Leong W-Y, Lopez LF, Amaku M, Quam M, Khan K, et al. Potential for international spread of wild poliovirus via travelers. BMC Med. 2015;13:133. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0363-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Elachola H, Chitale RA, Ebrahim SH, Wassilak SGF, Memish ZA. Polio priority countries and the 2018 Hajj: leveraging an opportunity. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2018;25:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ahmed QA, Arabi YM, Memish ZA. Health risks at the Hajj. Lancet. 2006;367:1008–15. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68429-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].WHO International Health Regulations (IHR) 2005. https://www.who.int/ihr/finalversion9Nov07.pdf (last accessed July 25, 2019).

- [44].World Health Organization New yellow fever vaccination requirements for travellers. 2016 http://www.who.int/ith/updates/20160727/en/ (accessed August 18, 2017).

- [45].World Health Organization Countries with risk of yellow fever transmission and countries requiring yellow fever vaccination. 2016 http://www.who.int/ith/2016-ith-annex1.pdf?ua=1 (accessed August 20, 2017).

- [46].Rashid H, Shafi S, Booy R, El Bashir H, Ali K, Zambon MC, et al. Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infections in British Hajj pilgrims. Emerg Health Threats J. 2008;1:e2. doi: 10.3134/ehtj.08.002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22460211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kandeel A, Deming M, Elkreem EA, El-Refay S, Afifi S, Abukela M, et al. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 and Hajj pilgrims who received predeparture vaccination, Egypt. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1266–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1707.101484. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21762583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ziyaeyan M, Alborzi A, Jamalidoust M, Moeini M, Pouladfar GR, Pourabbas B, et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection among 2009 Hajj Pilgrims from Southern Iran: a real-time RT-PCR-based study. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6:e80–e4. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Memish ZA, Assiri AM, Hussain R, Alomar I, Stephens G. Detection of respiratory viruses among pilgrims in Saudi Arabia during the time of a declared influenza A(H1N1) pandemic. J Travel Med. 2012;19:15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Refaey S, Amin MM, Roguski K, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Uyeki TM, Labib M, et al. Cross-sectional survey and surveillance for influenza viruses and MERS-CoV among Egyptian pilgrims returning from Hajj during 2012–2015. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2016;11:57–60. doi: 10.1111/irv.12429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ashshi A, Azhar E, Johargy A, Asghar A, Momenah A, Turkestani A, et al. Demographic distribution and transmission potential of influenza A and 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 in pilgrims. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:1169–75. doi: 10.3855/jidc.4204. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25212081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Annan A, Owusu M, Marfo KS, Larbi R, Sarpong FN, Adu-Sarkodie Y, et al. High prevalence of common respiratory viruses and no evidence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Hajj pilgrims returning to Ghana, 2013. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20:807–12. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Benkouiten S, Charrel R, Belhouchat K, Drali T, Nougairede A, Salez N, et al. Respiratory viruses and bacteria among pilgrims during the 2013 Hajj. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1821–7. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Gautret P, Charrel R, Benkouiten S, Belhouchat K, Nougairede A, Drali T, et al. Lack of MERS coronavirus but prevalence of influenza virus in French pilgrims after 2013 Hajj. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:728–30. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Rashid H, Shafi S, Haworth E, El Bashir H, Ali KA, Memish ZA, et al. Value of rapid testing for influenza among Hajj pilgrims. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2007;5:310–3. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Rashid H, Shafi S, Haworth E, El Bashir H, Memish ZA, Sudhanva M, et al. Viral respiratory infections at the Hajj: comparison between UK and Saudi pilgrims. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:569–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Alborzi A, Aelami MH, Ziyaeyan M, Jamalidoust M, Moeini M, Pourabbas B, et al. Viral etiology of acute respiratory infections among Iranian Hajj pilgrims, 2006. J Travel Med. 2009;16:239–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Moattari A, Emami A, Moghadami M, Honarvar B. Influenza viral infections among the Iranian Hajj pilgrims returning to Shiraz, Fars province, Iran. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6:e77–e9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Barasheed O, Almasri N, Badahdah A-M, Heron L, Taylor J, McPhee K, et al. Pilot randomised controlled trial to test effectiveness of facemasks in preventing influenza-like illness transmission among Australian Hajj pilgrims in 2011. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2014;14:110–6. doi: 10.2174/1871526514666141021112855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Barasheed O, Rashid H, Alfelali M, Tashani M, Azeem M, Bokhary H, et al. Viral respiratory infections among Hajj pilgrims in 2013. Virol Sin. 2014;29:364–71. doi: 10.1007/s12250-014-3507-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Memish ZA, Almasri M, Turkestani A, Al-Shangiti AM, Yezli S. Etiology of severe community-acquired pneumonia during the 2013 Hajj—part of the MERS-CoV surveillance program. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;25:186–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Aberle JH, Popow-Kraupp T, Kreidl P, Laferl H, Heinz FX, Aberle SW. Influenza A and B viruses but not MERS-CoV in Hajj pilgrims, Austria, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:726–7. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Alfelali M, Khandaker G, Booy R, Rashid H. Mismatching between circulating strains and vaccine strains of influenza: effect on Hajj pilgrims from both hemispheres. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:709–15. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1085144. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26317639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Saudi Ministry of Health Hajj 1438 Hijrah (2017) - Health Regulations. 2017 http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Hajj/Pages/HealthRegulations.aspx (accessed August 18, 2017).

- [65].Alfelali M, Barasheed O, Tashani M, Azeem MI, El Bashir H, Memish ZA, et al. Changes in the prevalence of influenza-like illness and influenza vaccine uptake among Hajj pilgrims: a 10-year retrospective analysis of data. Vaccine. 2015;33:2562–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Al-Tawfiq JA, Benkouiten S, Memish ZA. A systematic review of emerging respiratory viruses at the Hajj and possible coinfection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2018;23:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Edouard S, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA, Yezli S, Gautret P. Impact of the Hajj on pneumococcal carriage and the effect of various pneumococcal vaccines. Vaccine. 2018;36:7415–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.09.017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30236632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Prevention of pneumococcal infections during mass gathering. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:326–30. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1058456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Al-Tawfiq JA, Smallwood CAH, Arbuthnott KG, Malik MSK, Barbeschi M, Memish ZA. Emerging respiratory and novel coronavirus 2012 infections and mass gatherings. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19:S48–S54. doi: 10.26719/2013.19.supp1.s48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Atabani SF, Wilson S, Overton-Lewis C, Workman J, Kidd IM, Petersen E, et al. Active screening and surveillance in the United Kingdom for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in returning travellers and pilgrims from the Middle East: a prospective descriptive study for the period 2013–2015. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:10–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].ProMed Novel coronavirus – Eastern Mediterranean (03); Saudi comment. 2013 http://promedmail.org/post/20130326.1603038 (accessed February 12, 2013).

- [72].Griffiths K, Charrel R, Lagier J-C, Nougairede A, Simon F, Parola P, et al. Infections in symptomatic travelers returning from the Arabian peninsula to France: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:414–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Gautret P, Charrel R, Belhouchat K, Drali T, Benkouiten S, Nougairede A, et al. Lack of nasal carriage of novel corona virus (HCoV-EMC) in French Hajj pilgrims returning from the Hajj 2012, despite a high rate of respiratory symptoms. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:E315–E7. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Baharoon S, Al-Jahdali H, Al Hashmi J, Memish ZA, Ahmed QA. Severe sepsis and septic shock at the Hajj: etiologies and outcomes. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2009;7:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Sridhar S, Brouqui P, Parola P, Gautret P. Imported cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome: an update. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015;13:106–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Al-Tawfiq JA, Zumla A, Memish ZA. Travel implications of emerging coronaviruses: SARS and MERS-CoV. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014;12:422–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Gautret P, Benkouiten S, Sridhar S, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Diarrhea at the Hajj and Umrah. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015;13:159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].McDonald R, Ruppert PS, Souto M, Johns DE, McKay K, Bessette N, et al. Notes from the field: measles outbreaks from imported cases in Orthodox Jewish communities — New York and New Jersey, 2018–2019. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:2131–3. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Patel M, Lee AD, Redd SB, Clemmons NS, McNall RJ, Cohn AC, et al. Increase in measles cases — United States, January 1–April 26, 2019. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:2127–30. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Carlson A, Riethman M, Gastañaduy P, Lee A, Leung J, Holshue M, et al. Notes from the field: Community outbreak of measles — Clark County, Washington, 2018–2019. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:2134–5. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Mahase E. Measles cases rise 300% globally in first few months of 2019. BMJ. 2019;365:l1810. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Gautret P, Steffen R. Communicable diseases as health risks at mass gatherings other than Hajj: what is the evidence? Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Al-Tawfiq JA, Gautret P, Benkouiten S, Memish ZA. Mass gatherings and the spread of respiratory infections. Lessons from the Hajj. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:759–65. doi: 10.1513/annalsats.201511-772fr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Elachola H, Assiri A, Turkestani AH, Sow SS, Petersen E, Al-Tawfiq JA, et al. Advancing the global health security agenda in light of the 2015 annual Hajj pilgrimage and other mass gatherings. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;40:133–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]