Abstract

Objectives

To examine electronic cigarette use, reasons for use and perceptions of harm among university students.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

University students across New Zealand.

Methods

We analysed data from a 2018 cross-sectional survey of university students, weighted to account for undersampling and oversampling by gender and university size. χ2 tests were used to compare e-cigarette use, reasons for use and perceptions of harm by age, gender, ethnicity and cigarette smoking.

Participants

The sample comprised 1476 students: 62.3% aged 18–20 years, 37.7% aged 21–24 years; 38.6% male, 61.4% female; 7.9% Māori and 92.1% non-Māori.

Results

40.5% of respondents (95% CI 37.9 to 43.1) reported ever, 6.1% (4.9–7.4) current and 1.7% (1.1–2.5) daily use. Regardless of frequency, 11.5% of vapers had vaped daily for ≥1 month, 70.2% of whom used nicotine-containing devices; 80.8% reported not vaping in indoor and 73.8% in outdoor smoke-free spaces. Among ever vapers, curiosity (67.4%), enjoyment (14.4%) and quitting (2.4%) were common reasons for vaping. 76.1% (73.4–78.7) of respondents believed e-cigarettes were less harmful than cigarettes.

More males than females reported vaping (ever, current, daily and daily for ≥1 month), nicotine use and belief that e-cigarettes were less harmful than cigarettes. More participants aged 18–20 years reported not vaping in outdoor smoke-free spaces, vaping out of curiosity and belief that e-cigarettes were less harmful than cigarettes, while more participants aged 21–24 years vaped daily for ≥1 month and for enjoyment. More Māori than non-Māori ever vaped. More cigarette smokers than non-smokers vaped (ever, current, daily and daily for ≥1 month), used nicotine and vaped to quit, while more non-smokers did not vape in smoke-free spaces and vaped out of curiosity.

Conclusions

Our results suggest high prevalence of e-cigarette ever and current use, particularly among males and smokers. Many vaped out of curiosity and perceived e-cigarettes as less harmful than cigarettes.

Keywords: public health, epidemiology, preventive medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study in New Zealand to examine e-cigarette use in university students.

Data were weighted to improve representation of the New Zealand university population.

The main limitation of this study is that sampling was not random and our convenience sample is susceptible to volunteer bias, which could lead to underestimation or overestimation of prevalence estimates.

INTRODUCTION

Electronic cigarette or e-cigarette use (vaping) has become increasingly popular in in recent years,1–14 particularly among youth and smokers. However, the role of vaping in tobacco control remains controversial. Proponents argue that vaping could potentially help smokers cut down or quit altogether and reduce the public health burden from smoking,8 12 15–21 while opponents argue that it might undermine current tobacco control policies and create new nicotine addicts who could potentially transition to smoking.15 17 18 20 In the background of this debate, vaping continues to expand globally and in New Zealand (NZ). A 2013 study reported that 23% of adult smokers and 39% of recent quitters in NZ ever vaped;22 in 2014, 13.1% of NZ adults aged 15 years or older reported ever vaping and 0.8% were current vapers,23 and a recent systematic review noted that ever e-cigarette use among adults and adolescents had increased in NZ, but current use remained low.24

A number of studies have reported vaping among adults aged 18–24 years. In a study that examined the differences in vaping between college and non-college participants aged 18–24 years, Buu and colleagues reported that 15.36% of non-college and 9.61% of college participants vaped in the past 30 days (p<0.001).25 Delveno et al examined how patterns of e-cigarette use among adults differ between smokers and non-smokers using data from the 2014 National Health Interview Survey and reported that among those aged 18–24 years, 21.6% ever tried an e-cigarette, 4.3% vaped ‘somedays’ and 0.9% vaped daily.3 Li and others examined e-cigarette ever and current use (current users vaped at least once a month or more frequently) among NZ adults using data from the 2014 Health and Lifestyles Survey (HLS) and found that among 18–24 year olds, 25.8% ever vaped and 0.2% currently vaped.23 A 2016 study that assessed 2-year trends and predictors of e-cigarette use in 27 European Union member states during 2012–2014 reported that 5.75% of participants aged 18–24 years ever vaped.4

In NZ, literature suggests that adolescents and young adults are more likely to try e-cigarettes than older adults are. Data from the New Zealand Health Survey, an annual survey of a nationally representative sample of over 13 000 adults ‘usually resident’ in NZ, show that in 2018/2019 people aged 18–24 years had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette ever use (47.3%) and current use (8.8%), and third highest prevalence of daily use (4.5%; 4.9% in 35–44 years, 5.1% in 25–34 years).26 Using the 2011/2012 data from the New Zealand Smoking Monitor (NZSM), Li and colleagues found those aged 18–24 years were four times as likely to have ever purchased an e-cigarette than those aged ≥45 years;27 White and colleagues reported almost tripling of e-cigarette ever use among NZ adolescents from 7.9% in 2012 to 19.9% in 2014;14 and the 2017 ASH Year 10 students survey (a national survey of New Zealand students aged 14–15 years, with a 49% school participation rate) reported that 29.1% ever vaped and 1.9% vaped daily.28

Data on vaping among tertiary students (college or university) in NZ are lacking. Current research on e-cigarette use among tertiary students predominantly comes from the United States (US) and Europe. The prevalence of e-cigarette ever use across US studies ranges from 27% to 45%,29–33 with common predictors being cigarette smoking and male gender, while the prevalence of ever vaping in Europe ranges from 23%–31% with a common predictor being smoking (current or previous).34–36 Further, a study of Korean students aged 19–29 years (n=2167) found that 21.2% ever vaped (96.3% of whom also tried conventional cigarettes).37 In this study, male gender, smoking and close friends or siblings who smoke were predictors for e-cigarette use.

University students face a range of social, emotional and educational challenges,38 and experience fundamental changes in social contexts and identity, as they transition to life away from home.39 Greater independence and new friends may predispose students to experiment with new situations and products, including e-cigarettes. Given NZ’s aspirations to reduce smoking to minimal levels by the year 2025,40 it is vital to understand patterns of electronic cigarette use among young adults, a population at risk for future tobacco addiction.

This study sought to estimate the prevalence and reasons for vaping, and the perceived harm of e-cigarettes compared with tobacco cigarettes, among university students aged 18–24 years in NZ. This age band was chosen for three reasons: (1) it had not been studied previously in a tertiary education context in NZ; (2) it had the highest e-cigarette ever and current use in NZ (national estimates), and (3) it allowed for comparisons with prevalence estimates at national26 and international3 4 6 23 25 33 41 levels that used a similar age band. This information would contribute to our understanding of the uptake of e-cigarettes in this population and potentially contribute to tobacco prevention policy considerations that promote public health locally and beyond.

METHODS

We analysed data from a March–May 2018 cross-sectional survey of university students across NZ. The survey collected data on vaping, smoking and the Smokefree 2025 goal, which aims to reduce the prevalence of smoking to five percent or less by the year 2025.40 This paper concentrates on the data on vaping.

The survey aimed to recruit a minimum of 1062 participants, with a good mix of domestic, international, Māori (the Indigenous population of NZ) and non-Māori students. This estimate assumed random sampling and was based on the 2016 Universities NZ data that showed the total NZ university students population of 172 000; CI of 95%; estimated ever-vaping proportion of 0.5 (conservative estimate), and margin of error of 3%.42

Random sampling was not possible due to lack of access to complete enrolment lists of students from the universities to facilitate this approach. A convenience sample was used and we recognise that volunteer bias could lead to underestimation or overestimation of prevalence estimates. Data were weighted based on gender and institution size, as in our previous work,43 to partly address this.

The survey

Currently enrolled students at any university in NZ were eligible to participate. Participation was voluntary and participants were free to join online or in person. The survey was distributed widely online (on respective university students’ association Facebook pages) and through direct contact with research assistants (RAs) from participating universities.43 RAs were provided with training and supervision to collect and relay data securely to the principal investigator. Students received a description of the study and were required to consent to participation by answering ‘Yes’ to the question, ‘Do you agree to take part in this survey?’ before completing the questionnaire. This study employed both an online and a paper-based survey tool. The online questionnaire allowed participants to click on a link on a computer or smart phone and submit responses electronically, while the paper questionnaire was distributed and responses collected by RAs. Participants could enter a draw to win one of ten NZ$100 cash prizes after survey completion as a token of appreciation. Internet Protocol address (IP address) was used to remove duplicate entries in the online route. Data were deidentified before analysis.

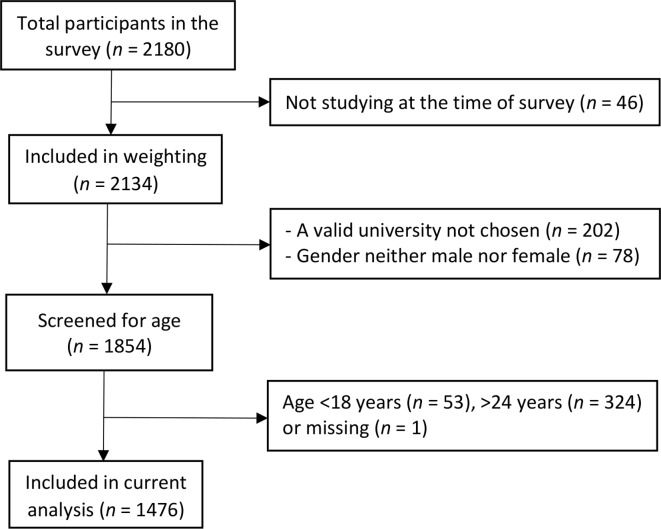

The questionnaire used previously validated items. The ethnicity question was based on the NZ census,44 questions on e-cigarette use were adapted from Pearson and others45 and questions on smoking were adapted from the NZ Tobacco Use Survey.46 Further, the questionnaire was piloted on 22 students at the University of Canterbury in October 2017 using recruitment and data collection approaches described previously. A total of 2180 students took part in the survey and 1476 met the criteria for inclusion in this analysis (see figure 1).43

Figure 1.

Flowchart of selection of participants included in this study.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in this project.

Survey measures

Items on demographic characteristics, cigarette smoking and e-cigarette use are described below.

Demographic characteristics

Information on age, gender, ethnicity, years lived in NZ and university was accessed. Age-specific analyses compared participants aged 18–20 years with participants aged 21–24 years. Ethnicity-specific analyses compared Māori with non-Māori, as in previous studies.47–49 This was done using the concept of prioritised ethnicity50 where each respondent is allocated to a single ethnic group based on the ethnic groups they identify with, for the purpose of analysis. In this analysis, all respondents who selected Māori among the ethnic groups that they identified with were classified as Māori and respondents who did not select Māori were classified as non-Māori. We used the time lived in NZ as a proxy to infer the numbers of domestic students (six years or more) and international students (five years or less), similar to a previous study.43 Respondents could choose one or more university from a list of all eight NZ universities, where they were currently enrolled. We used this variable to assess the representativeness of the sample in relation to the general NZ university student population.

E-cigarette use (vaping)

All questions on e-cigarette use behaviour (except use in smoke-free spaces), reasons for use and perceptions of harm were adapted from Pearson and others.45 Respondents were asked ‘Have you ever tried an e-cigarette or vaping device?’, with response options of ‘Yes’ and ‘No’. Those who answered ‘Yes’ were defined as ‘ever vapers’. Ever vapers were asked ‘How often do you currently use an e-cigarette or vaping device?’, with response options of ‘Daily or almost daily’, ‘Less than daily, but at least once a week’, ‘Less than weekly, but at least once a month’, ‘Less than monthly’, ‘Not at all’ and ‘Don’t know’. Respondents who reported using an e-cigarette or vaping device daily or almost daily were defined as ‘daily vapers’ and those who used an e-cigarette at least once a month or more frequently were defined as ‘current vapers’ as in previous research.30 35 51

Use in smoke-free spaces was tested by two questions which had similar responses. The first question asked ‘How often do you vape/use an e-cigarette in indoor spaces where smoking is banned?’ and the second question asked ‘How often do you vape/use an e-cigarette in outdoor spaces where smoking is banned?’ The response options for both questions were ‘Never’, ‘Almost never’, ‘Sometimes’, ‘Fairly often’ and ‘Very often’. For analysis, the options were dichotomised into ‘Never/almost never’ and ‘Other’ due to small numbers in the three response options outside never/almost never. This question was relevant to participants who vaped daily, weekly, monthly or less than monthly.

Reasons for use were tested by ‘What is (was) your primary reason for using an e-cigarette or vaping device?’ with response options of ‘To quit smoking’, ‘To cut down on smoking’, ‘To use when I cannot or I am not allowed to smoke’, ‘To avoid returning to smoking’, ‘Because I enjoy(ed) it’, ‘Curiosity/just wanted to try them’, ‘To save money compared with purchasing cigarettes’, ‘Some other reason’ and ‘Don’t know’. The three most reported reasons for vaping (ie, to quit smoking, enjoyment and curiosity/just wanted to try them) were used in analysis. This question was relevant to participants who ever vaped.

Perceptions of harm were tested by ‘Compared with tobacco cigarettes, how harmful are e-cigarettes to a person’s health?’ with the response options as ‘Much less harmful than cigarettes’, ‘Somewhat less harmful than cigarettes’, ‘About the same as cigarettes’, ‘Somewhat more harmful than cigarettes’, ‘Much more harmful than cigarettes’ and ‘Don’t know’. For analysis, the response options were dichotomised into much less/somewhat less harmful and other due to small numbers in the response options outside much less/somewhat less harmful. This question was relevant to all participants.

Tobacco use

Ever smoking was tested by ‘Have you ever smoked cigarettes or tobacco at all, even just a few puffs?’ with response options of ‘Yes’ and ‘No’. Respondents who answered ‘Yes’ were further asked ‘Which of the following best describes how often you smoke cigarettes or tobacco now?’ with response options of ‘At least once a day’, ‘At least once a week’, ‘At least once a month’ and ‘Less often than once a month’. Respondents who reported smoking at least once a month or more frequently were defined as current smokers, consistent with previous studies.43 52–55

Data analysis

χ2 tests were used to compare the prevalence of e-cigarette use, reasons for use and perceptions of harm by age (18–20 years vs 21–24 years), gender (male vs female), ethnicity (Māori vs non-Māori) and smoking status (current smokers vs non-smokers). Responses were weighted to account for undersampling and oversampling based on gender and institution size.43 However, inconsistent reporting of necessary summary data across universities meant that weights to account for undersampling and oversampling with respect to age and ethnicity could not be calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.25, and two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. CIs were reported where appropriate.

RESULTS

The sample included 1476 participants. Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of the sample, while table 243 compares the sample with the NZ university student population in 2018. Besides age, there were no other significant differences in the characteristics of participants, and the overall e-cigarette use behaviour based on recruitment approach (online or in person) (online supplementary appendix 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Variable | Sample (n=1476) % |

| Age | |

| 18–20 years | 919 (62.3) |

| 21–24 years | 557 (37.7) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 569 (38.6) |

| Female | 907 (61.4) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Māori | 117 (7.9) |

| Non-Māori | 1359 (92.1) |

| Years lived in NZ | |

| ≤5 years | 307 (20.8%) |

| ≥6 years | 1164 (78.9%) |

| Missing data | 5 (0.3) |

NZ, New Zealand.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of participants in this study versus NZ university students in 2018

| This paper | NZ university students in 2018 (%)* | ||

| Unweighted (%) | Weighted (%) | ||

| Student type | |||

| Domestic | 79.1 | 77.5 | 82 |

| International | 20.9 | 22.5 | 18 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Māori | 7.9 | 6.9 | 9.6 |

| Non-Māori | 92 | 93.1 | 90.4 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 38.6 | 40.8 | 41.8 |

| Female | 61.4 | 59.2 | 58.2 |

*Source: Ministry of Education.63 Data extracted from Excel sheets ENR.31, ENR.32 and ENR.34.

NZ, New Zealand.

bmjopen-2019-035093supp001.pdf (99.9KB, pdf)

E-cigarette use; overall

Use behaviour: 40.5% of the sample (95% CI 37.9% to 43.1%) reported ever, 6.1% (95% CI 4.9% to 7.4%) current and 1.7% (95% CI 1.1% to 2.5%) daily use; about 98% of the sample responded. Regardless of vaping frequency, 11.5% (95% CI 8.6% to 14.9%) of vapers had vaped daily for ≥1 month, 70.2% (95% CI 55.1% to 82.7%) of whom had used nicotine-containing devices, 80.8% (95% CI 75.5% to 85.3%) reported not vaping in indoor and 73.8% (95% CI 68.0% to 79.0%) in outdoor smoke-free spaces.

Reasons for use: Among ever vapers, curiosity (67.4%, 95% CI 62.7% to 71.9%), enjoyment (14.4%, 95% CI 11.2% to 18.1%) and quitting (2.4%, 95% CI 1.2% to 4.4%) were the most common reasons for vaping.

Perceptions of harm: Regardless of vaping status, 76.1% (95% CI 73.4% to 78.7%) of respondents believed that e-cigarettes were less harmful (much less harmful—28.6%, somewhat less harmful—47.5%) to a person’s life than tobacco cigarettes: 70.5% of the sample responded to this question.

E-cigarette use by age

Participants aged 18–20 years were significantly more likely than participants aged 21–24 years to report not vaping in outdoor smoke-free spaces (78.2% vs 67.0%, p=0.043), curiosity as the primary reason for use (74.7% vs 56.1%, p<0.001) and belief that e-cigarettes were less harmful than tobacco cigarettes (79.6% vs 69.9%, p<0.001), while participants aged 21–24 years were significantly more likely than participants aged 18–20 years to report daily use for a month or more (16.5% vs 8.1%, p=0.008) and enjoyment as the primary reason for use (21.3% vs 9.9%, p=0.001) (table 3).

Table 3.

E-cigarette use behaviour, reasons for use and perceptions of harm; by age group

| 18–20 years | 21–24 years | Total | P value | |

| Use behaviour | ||||

| Ever use (n=1425) | ||||

| Yes | 351 (39.8) | 226 (41.7) | 577 (40.5) | 0.467 |

| No | 532 (60.2) | 316 (58.3) | 848 (59.5) | |

| Current use (n=1448) | ||||

| Yes | 46 (5.1) | 41 (7.4) | 87 (6.0) | 0.077 |

| No | 849 (94.9) | 512 (92.6) | 1361 (94.0) | |

| Daily use (n=1449) | ||||

| Yes | 11 (1.2) | 13 (2.3) | 24 (1.7) | 0.105 |

| No | 884 (98.8) | 541 (97.7) | 1425 (98.3) | |

| Daily use for a month or more (n=428) | ||||

| Yes | 21 (8.1) | 28 (16.5) | 49 (11.4) | 0.008 |

| No | 237 (91.9) | 142 (83.5) | 379 (88.6) | |

| Use of nicotine (n=47) | ||||

| Yes | 14 (73.7) | 19 (67.9) | 33 (70.2) | 0.668 |

| No | 5 (26.3) | 9 (32.1) | 14 (29.8) | |

| Use in indoor smokefree spaces (n=266) | ||||

| No | 131 (82.9) | 83 (76.9) | 214 (80.5) | 0.221 |

| Other* | 27 (17.1) | 25 (23.1) | 52 (19.5) | |

| Use in outdoor smokefree spaces (n=262) | ||||

| No | 122 (78.2) | 71 (67.0) | 193 (73.7) | 0.043 |

| Other* | 34 (21.8) | 35 (33.0) | 69 (26.3) | |

| Reasons for use | ||||

| To quit smoking (n=417) | ||||

| Yes | 5 (2.0) | 5 (3.0) | 10 (2.4) | 0.484 |

| No | 248 (98.0) | 159 (97.0) | 407 (97.6) | |

| For enjoyment (n=417) | ||||

| Yes | 25 (9.9) | 35 (21.3) | 60 (14.4) | 0.001 |

| No | 228 (90.1) | 129 (78.7) | 357 (85.6) | |

| Curiosity/just wanted to try them (n=417) | ||||

| Yes | 189 (74.7) | 92 (56.1) | 281 (67.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 64 (25.3) | 72 (43.9) | 136 (32.6) | |

| Perceptions of harm | ||||

| Less harmful than cigarettes (n=1022) | ||||

| Yes | 520 (79.6) | 258 (69.9) | 778 (76.1) | <0.001 |

| Other† | 133 (20.4) | 111 (30.1) | 244 (23.9) | |

The cells contain rounded weighted counts and sometimes the marginal totals are not exactly the sum of the component cells.

*Includes sometimes, fairly often and very often.

†Includes about same as cigarettes, somewhat more harmful than cigarettes, much more harmful than cigarettes and do not know.

E-cigarette use by gender

Males were significantly more likely than females to report ever (51.2% vs 33.1%, p<0.001), current (8.8% vs 4.1%, p<0.001) and daily use (3.1% vs 0.7%, p=0.001), daily use for ≥1 month (16.1% vs 6.8%, p=0.003), using nicotine-containing devices (77.1% vs 45.5%, p=0.046) and belief that e-cigarettes were less harmful than tobacco cigarettes (81.1% vs 72.8%, p=0.002) (table 4).

Table 4.

E-cigarette use behaviour, reasons for use and perceptions of harm; by gender

| Male | Female | Total | P value | |

| Use behaviour | ||||

| Ever use (n=1425) | ||||

| Yes | 296 (51.2) | 280 (33.1) | 576 (40.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 282 (48.8) | 566 (66.9) | 848 (59.6) | |

| Current use (n=1448) | ||||

| Yes | 52 (8.8) | 35 (4.1) | 87 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| No | 538 (91.2) | 823 (95.9) | 1361 (94.0) | |

| Daily use (n=1449) | ||||

| Yes | 18 (3.1) | 6 (0.7) | 24 (1.7) | 0.001 |

| No | 572 (96.9) | 852 (99.3) | 1424 (98.3) | |

| Daily use for a month or more (n=428) | ||||

| Yes | 36 (16.1) | 14 (6.8) | 50 (11.7) | 0.003 |

| No | 188 (83.9) | 191 (93.2) | 379 (88.3) | |

| Use of nicotine (n=47) | ||||

| Yes | 27 (77.1) | 5 (45.5) | 32 (69.6) | 0.046 |

| No | 8 (22.9) | 6 (54.5) | 14 (30.4) | |

| Use in indoor smokefree spaces (n=266) | ||||

| No | 114 (79.2) | 100 (82.0) | 214 (80.5) | 0.566 |

| Other* | 30 (20.8) | 22 (18.0) | 52 (19.5) | |

| Use in outdoor smokefree spaces (n=262) | ||||

| No | 107 (75.9) | 87 (71.3) | 194 (73.8) | 0.400 |

| Other* | 34 (24.1) | 35 (28.7) | 69 (26.2) | |

| Reasons for use | ||||

| To quit smoking (n=417) | ||||

| Yes | 8 (3.7) | 2† (1.0) | 10 (2.4) | 0.076 |

| No | 210 (96.3) | 197 (99.0) | 407 (97.6) | |

| For enjoyment (n=417) | ||||

| Yes | 35 (16.1) | 25 (12.6) | 60 (14.4) | 0.310 |

| No | 183 (83.9) | 174 (87.4) | 357 (85.6) | |

| Curiosity/just wanted to try them (n=417) | ||||

| Yes | 139 (63.8) | 142 (71.4) | 281 (67.4) | 0.098 |

| No | 79 (36.2) | 57 (28.6) | 136 (32.6) | |

| Perceptions of harm | ||||

| Less harmful than cigarettes (n=1022) | ||||

| Yes | 338 (81.1) | 440 (72.8) | 778 (76.2) | 0.002 |

| Other‡ | 79 (18.9) | 164 (27.2) | 243 (23.8) | |

The cells contain rounded weighted counts and sometimes the marginal totals are not exactly the sum of the component cells.

*Includes sometimes, fairly often and very often.

†Expected cell count less than 5.

‡Includes about same as cigarettes, somewhat more harmful than cigarettes, much more harmful than cigarettes and do not know.

E-cigarette use by ethnicity

Māori respondents were significantly more likely to report ever vaping (57.1% vs 39.2%, p<0.001) compared with non-Māori respondents. All other comparisons were not significant (online supplementary appendix 2).

bmjopen-2019-035093supp002.pdf (128.5KB, pdf)

E-cigarette use by smoking status

Cigarette smokers were significantly more likely than non-smokers to report ever (71.9% vs 36.7%, p<0.001), current (13.7% vs 5.1%, p<0.001) and daily use (5.6% vs 1.2%, p<0.001), daily use for ≥1 month (21.7% vs 8.6%, p<0.001), using nicotine-containing devices (88.2% vs 60.0%, p=0.042) and use to quit smoking (6.8% vs 1.2%, p=0.002), while non-smokers were significantly more likely than cigarette smokers to report not vaping in indoor (84.5% vs 69.2%, p=0.007), or in outdoor (77.4% vs 62.5%, p=0.019) smoke-free spaces and to report curiosity as the primary reason for use (71.1% vs 53.4%, p=0.002) (table 5).

Table 5.

E-cigarette use behaviour, reasons for use and perceptions of harm; by smoking status

| Cigarette smoker | Non-smoker* | Total | P value | |

| Use behaviour | ||||

| Ever use (n=1425) | ||||

| Yes | 110 (71.9) | 466 (36.7) | 576 (40.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 43 (28.1) | 805 (63.3) | 848 (59.6) | |

| Current use (n=1448) | ||||

| Yes | 22 (13.7) | 66 (5.1) | 88 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 139 (86.3) | 1222 (94.9) | 1361 (93.9) | |

| Daily use (n=1449) | ||||

| Yes | 9 (5.6) | 15 (1.2) | 24 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| No | 152 (94.4) | 1273 (98.8) | 1425 (98.3) | |

| Daily use for a month or more (n=428) | ||||

| Yes | 20 (21.7) | 29 (8.6) | 49 (11.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 72 (78.3) | 307 (91.4) | 379 (88.6) | |

| Use of nicotine (n=47) | ||||

| Yes | 15 (88.2) | 18 (60.0) | 33 (70.2) | 0.042 |

| No | 2† (11.8) | 12 (40.0) | 14 (29.8) | |

| Use in indoor smokefree spaces (n=266) | ||||

| No | 45 (69.2) | 169 (84.5) | 214 (80.8) | 0.007 |

| Other‡ | 20 (30.8) | 31 (15.5) | 51 (19.2) | |

| Use in outdoor smokefree spaces (n=262) | ||||

| No | 40 (62.5) | 154 (77.4) | 194 (73.8) | 0.019 |

| Other‡ | 24 (37.5) | 45 (22.6) | 69 (26.2) | |

| Reasons for use | ||||

| To quit smoking (n=417) | ||||

| Yes | 6 (6.8) | 4† (1.2) | 10 (2.4) | 0.002 |

| No | 82 (93.2) | 325 (98.8) | 407 (97.6) | |

| For enjoyment (n=417) | ||||

| Yes | 12 (13.5) | 49 (14.9) | 61 (14.6) | 0.738 |

| No | 77 (86.5) | 280 (85.1) | 357 (85.4) | |

| Curiosity/just wanted to try them (n=417) | ||||

| Yes | 47 (53.4) | 234 (71.1) | 281 (67.4) | 0.002 |

| No | 41 (46.6) | 95 (28.9) | 136 (32.6) | |

| Perceptions of harm | ||||

| Less harmful than cigarettes (n=1022) | ||||

| Yes | 76 (72.4) | 702 (76.6) | 778 (76.1) | 0.342 |

| Other§ | 29 (27.6) | 215 (23.4) | 244 (23.9) | |

The cells contain rounded weighted counts and sometimes the marginal totals are not exactly the sum of the component cells.

*Includes never smokers and smokers who smoke less than once a month.

†Expected cell count less than 5.

‡Includes sometimes, fairly often and very often.

§Includes about same as cigarettes, somewhat more harmful than cigarettes, much more harmful than cigarettes and don’t know.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in New Zealand to estimate the prevalence of e-cigarette use, reasons for use and perceptions of harm among university students. We report the prevalence of ever (40.5%), current (6.1%) and daily use (1.7%). Ever, current and daily use were all significantly higher in males than females and in cigarette smokers than non-smokers. Curiosity was the most reported reason for vaping among respondents in our sample (67.4%). In our subanalyses, we also found curiosity reported as the primary reason for vaping by respondents aged 18–20 years compared with respondents aged 21–24 years, and by survey respondents who only vape compared with respondents who vape and use cigarettes. The majority of vapers (regardless of frequency) did not vape in indoor (80.8%) or outdoor (73.8%) spaces where smoking is banned (ie, smoke-free spaces), and 76.1% of respondents perceived e-cigarettes to be less harmful than tobacco cigarettes.

The current study has a number of limitations. We used a cross-sectional convenience sample and respondents may have completed the survey based on personal interest in the topic, possibly overestimating reported estimates. However, the questionnaire included questions on tobacco use, e-cigarettes and the Smokefree 2025 goal, which would appeal to a wider student population. A convenience sample is also susceptible to volunteer bias, which could lead to underestimation or overestimation of prevalence estimates.43 We weighted the data based on gender and university size to partially address this: there was insufficient information to allow weighting to account for age and ethnicity. Further, while the cross-sectional design is suitable for estimating prevalence, it is susceptible to non-response bias. The response rate for an important question on perceptions of harm was only 70.5% and it is unclear whether non-responders were non-vapers who did not see the question as relevant to them or respondents who chose not to respond. Lastly, some respondents may have been ineligible to participate or may have submitted multiple entries and/or haphazardly selected responses in an effort to complete the survey and enter the prize draw. We used IP addresses to identify and remove duplicate entries, and the responses were similar regardless of the recruitment approach (online supplementary appendix 1).

E-Cigarette use behaviour

Our estimate of ever use is low compared with the national ever use prevalence estimate in the same age group (ie, 40.5% vs 47.3%), but prevalence estimates of current (8.8% vs 8.8%) and daily use (4.5% vs 4.5%) were similar.26 The reported e-cigarette ever use in the present study is consistent with two previously reported estimates (37%–45%) among university students in the US.31 32 However, our study used more recent data and the sample had a larger proportion of males (38.6%), compared with the previous two studies (21%–22% males).31 32 Current e-cigarette use in the present study was similar to a previous study of French college students (5.7%),35 but lower than other studies among college/university students (7.5%–14.9%).25 30–33

Consistent with previous research,29 32 33 51 males were significantly more likely than females to report ever, current and daily use. This was expected considering that cigarette smoking is strongly associated with e-cigarette use,23 29 30 35 37 51 and our previous work using the same sample found significantly higher smoking prevalence (ever, current and daily) in males compared with females.43 Similarly, our findings of higher prevalence of e-cigarette use among cigarette smokers compared with non-smokers are consistent with those reported elsewhere.2 23 56 A finding of e-cigarette use behaviour by ethnicity differing significantly only for ever use (Māori 57.1%, non-Māori 39.2%, p<0.001) mirrors that of cigarette smoking (in the same sample) where only ever smoking was significantly different (Māori 75.2%, non-Māori 48.0%, p<0.001).43

Vaping in indoor and outdoor smoke-free spaces was uncommon, with 80.8% of vapers (regardless of vaping frequency) reporting that they did not vape in indoor smoke-free spaces and 73.8% reporting that they did not vape in outdoor smoke-free spaces. Non-smokers and younger participants (18–20 years) were more likely to report not vaping in smoke-free spaces than cigarette smokers and older participants, respectively. Using data drawn from Wave 2 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) dataset (2014–2015),57 Dunbar and colleagues found that 54.0% of respondents aged 18–24 years who vaped and smoked cigarettes (ie, dual users) reported vaping in smoke-free spaces. Overall, reported e-cigarette use to cut down on cigarette smoking (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.86 to 3.05), as an alternative to quitting (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.37 to 2.13), or because of belief that e-cigarettes help people to quit cigarette smoking (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.92) were significantly associated with increased odds of vaping in smoke-free places.57 In our present study, however, it was not clear whether the high prevalence of not vaping in smoke-free spaces was because of existing smoke-free regulations and/or enforcement of any such regulations or whether it was based solely on vapers’ own judgement. Further research is needed to monitor patterns of e-cigarette use in smoke-free spaces and the perceptions of non-vapers who share these spaces.

Reasons for use

Overall, curiosity was the leading reason for e-cigarette use (67.4% of respondents), similar to previous research.14 23 Younger participants and non-smokers were more likely to report vaping out of curiosity compared with older participants and cigarette smokers, respectively. This was expected given the low prevalence of cigarette smoking in younger participants in this sample.43 The second most commonly reported reason for vaping was enjoyment (14.4%), with only 2.4% of respondents reporting vaping to quit smoking. Considering that about 11% of the sample currently smoked43 and the vast majority of cigarette smokers vape, it is very likely that some vapers used e-cigarettes as a substitute to cigarette smoking or when they were not allowed, or unable to, smoke. If this is indeed true, it would support the concerns about vaping potentially creating new nicotine addicts, rather than helping smokers to quit.15 17 18 20

Perceptions of harm

The overall proportion of participants who perceived e-cigarettes to be less harmful than tobacco cigarettes was higher in the present study in comparison to previous estimates at national level (76.1% vs 38%).58 Males were more likely than females (81.1% vs 72.8%, p=0.002) and younger participants were more likely than older participants (79.6% vs 69.9%, p<0.001) to believe that e-cigarettes were less harmful than tobacco cigarettes.

Analysis of data from the 2016 HLS, a nationally representative, face-to-face, in-home survey that monitors the health behaviours and attitudes of NZ people aged 15 years and over shows that 45% of participants aged 15–24 years agreed that e-cigarettes were ‘safer’ than smoked cigarettes.58 In previous population surveys, many vapers and cigarette smokers perceived e-cigarettes to be less harmful than tobacco cigarettes.9 10 12 27 34 56 59–62 We did not find any significant differences in the perceptions of cigarette smokers and non-smokers about the harmfulness of e-cigarettes compared with tobacco cigarettes. However, the overall response rate for this question was low (70.5%). It is possible that non-responders were non-vapers who did not see the question as relevant to them.

Strengths of this study include a sample that had reasonably similar characteristics to the 2018 NZ university student population (table 2) making our findings potentially generalisable to the wider NZ university student population aged 18–24 years. Second, the numbers, characteristics of participants and the responses obtained from participants using the two recruitment routes were similar (online supplementary appendix 1). Furthermore, the questionnaire was available online and in person to reach a wider student community and to increase the response rate.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data suggest high prevalence of ever e-cigarette use but current use and daily use were low overall. About two-thirds of students had positive perceptions of e-cigarettes/vaping, and many vapers seemed to respect smoke-free spaces. These are encouraging findings from a public health perspective. Continued monitoring of patterns of use, particularly in older students, males, Māori and smokers is required to better understand how vaping trends impact on cigarette smoking in this important population group.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge university students across New Zealand who took part in the study and research assistants who supported data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: BW planned the study, collected and analysed data, and wrote the manuscript. MW-B, AR and RCG contributed to the planning, study design and the manuscript. PC contributed to study design, data collection and analysis.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: University of Canterbury Human Ethics Committee. Research Ethics ID: HEC 2017/42/LR-PS.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1.Eastwood B, Dockrell MJ, Arnott D, et al. . Electronic cigarette use in young people in Great Britain 2013-2014. Public Health 2015;129:1150–6. 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czoli CD, Hammond D, White CM. Electronic cigarettes in Canada: prevalence of use and perceptions among youth and young adults. Can J Public Health 2014;105:e97–e102. 10.17269/cjph.105.4119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Steinberg MB, et al. . Patterns of electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:715–9. 10.1093/ntr/ntv237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filippidis FT, Laverty AA, Gerovasili V, et al. . Two-Year trends and predictors of e-cigarette use in 27 European Union member states. Tob Control 2017;26:98–104. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gravely S, Fong GT, Cummings KM, et al. . Awareness, trial, and current use of electronic cigarettes in 10 countries: findings from the ITC project. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:11691–704. 10.3390/ijerph111111691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yong H-H, Borland R, Balmford J, et al. . Trends in e-cigarette awareness, trial, and use under the different regulatory environments of Australia and the United Kingdom. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:1203–11. 10.1093/ntr/ntu231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dockrell M, Morrison R, Bauld L, et al. . E-Cigarettes: prevalence and attitudes in Great Britain. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:ntt057:1737–44. 10.1093/ntr/ntt057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayers JW, Ribisl KM, Brownstein JS. Tracking the rise in popularity of electronic nicotine delivery systems (electronic cigarettes) using search query surveillance. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:448–53. 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adkison SE, O'Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, et al. . Electronic nicotine delivery systems: international tobacco control four-country survey. Am J Prev Med 2013;44:207–15. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rooke C, Amos A. News media representations of electronic cigarettes: an analysis of newspaper coverage in the UK and Scotland. Tob Control 2014;23:507–12. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douglas H, Hall W, Gartner C. E-Cigarettes and the law in Australia. Aust Fam Physician 2015;44:415–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etter J-F, Bullen C. Electronic cigarette: users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction 2011;106:2017–28. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03505.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, et al. . Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2013;382:1629–37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61842-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White J, Li J, Newcombe R, et al. . Tripling use of electronic cigarettes among New Zealand adolescents between 2012 and 2014. J Adolesc Health 2015;56:522–8. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell K, Keane H. Nicotine control: e-cigarettes, smoking and addiction. Int J Drug Policy 2012;23:242–7. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biener L, Hargraves JL. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use among a population-based sample of adult smokers: association with smoking cessation and motivation to quit. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:127–33. 10.1093/ntr/ntu200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cahn Z, Siegel M. Electronic cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy for tobacco control: a step forward or a repeat of past mistakes? J Public Health Policy 2011;32:16–31. 10.1057/jphp.2010.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riker CA, Lee K, Darville A, et al. . E-Cigarettes: promise or peril? Nurs Clin North Am 2012;47:159–71. 10.1016/j.cnur.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hitchman SC, Brose LS, Brown J, et al. . Associations between e-cigarette type, frequency of use, and quitting smoking: findings from a longitudinal online panel survey in Great Britain. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:1187–94. 10.1093/ntr/ntv078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palazzolo DL. Electronic cigarettes and vaping: a new challenge in clinical medicine and public health. A literature review. Front Public Health 2013;1:56. 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polosa R, Caponnetto P, Morjaria JB, et al. . Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e-cigarette) on smoking reduction and cessation: a prospective 6-month pilot study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:786. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Newcombe R, Walton D. The use of, and attitudes towards, electronic cigarettes and self-reported exposure to advertising and the product in general. Aust N Z J Public Health 2014;38:524–8. 10.1111/1753-6405.12283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Newcombe R, Walton D. The prevalence, correlates and reasons for using electronic cigarettes among New Zealand adults. Addict Behav 2015;45:245–51. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merry S, Bullen CR. E-Cigarette use in new Zealand-a systematic review and narrative synthesis. N Z Med J 2018;131:37–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buu A, Hu Y-H, Wong S-W, et al. . Comparing American College and noncollege young adults on e-cigarette use patterns including polysubstance use and reasons for using e-cigarettes. J Am Coll Health 2019:1–7. 10.1080/07448481.2019.1583662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health New Zealand Health Survey: Annual Data Explorer - Tobacco use. Available: https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2018-19-annual-data-explorer/_w_07aaf3d4/#!/explore-indicators [Accessed 15 Nov 2019].

- 27.Li J, Bullen C, Newcombe R, et al. . The use and acceptability of electronic cigarettes among New Zealand smokers. N Z Med J 2013;126:48–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Action for Smokefree 2025 ASH Year 10 Snapshot - E-cigarettes, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenne DR, Mix D, Banks M, et al. . Electronic cigarette initiation and correlates of use among never, former, and current tobacco cigarette smoking college students. J Subst Use 2016;21:491–4. 10.3109/14659891.2015.1068387 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Littlefield AK, Gottlieb JC, Cohen LM, et al. . Electronic cigarette use among college students: links to gender, Race/Ethnicity, smoking, and heavy drinking. J Am Coll Health 2015;63:523–9. 10.1080/07448481.2015.1043130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Copeland AL, Peltier MR, Waldo K. Perceived risk and benefits of e-cigarette use among college students. Addict Behav 2017;71:31–7. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allem J-P, Forster M, Neiberger A, et al. . Characteristics of emerging adulthood and e-cigarette use: findings from a pilot study. Addict Behav 2015;50:40–4. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saddleson ML, Kozlowski LT, Giovino GA, et al. . Risky behaviors, e-cigarette use and susceptibility of use among college students. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;149:25–30. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pénzes M, Foley KL, Balázs P, et al. . Intention to experiment with e-cigarettes in a cross-sectional survey of undergraduate university students in Hungary. Subst Use Misuse 2016;51:1083–92. 10.3109/10826084.2016.1160116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tavolacci M-P, Vasiliu A, Romo L, et al. . Patterns of electronic cigarette use in current and ever users among college students in France: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011344. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zarobkiewicz MK, Wawryk-Gawda E, Woźniakowski MM, et al. . Tobacco smokers and electronic cigarettes users among Polish universities students. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 2016;67:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeon C, Jung KJ, Kimm H, et al. . E-Cigarettes, conventional cigarettes, and dual use in Korean adolescents and university students: prevalence and risk factors. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;168:99–103. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amin SAEZ, Omran HMEY, Shaheen HM. Smoking among university students in Kafr El-Sheikh Universi. Menoufia Medical Journal 2016;29:1092–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kenford SL, Wetter DW, Welsch SK, et al. . Progression of college-age cigarette samplers: what influences outcome. Addict Behav 2005;30:285–94. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parliament NZ. Government Response to the Report of the Maori Affairs Select Committee on its Inquiry into the tobacco industry in Aotearoa and the consequences of tobacco use for Maori (Final Response. New Zealand Parliament: Wellington, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giovenco DP, Delnevo CD. Prevalence of population smoking cessation by electronic cigarette use status in a national sample of recent smokers. Addict Behav 2018;76:129–34. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Universities New Zealand New Zealand's Universities - Key Facts and Stats: summary of information sources. Universities New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wamamili B, Wallace-Bell M, Richardson A, et al. . Cigarette smoking among university students aged 18-24 years in New Zealand: results of the first (baseline) of two national surveys. BMJ Open 2019;9:e032590. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Statistics New Zealand Census definitions and forms. Statistics New Zealand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearson JL, Hitchman SC, Brose LS, et al. . Recommended core items to assess e-cigarette use in population-based surveys. Tob Control 2018;27:341–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ministry of Health New Zealand Smoking Monitor (New Zealand Tobacco Use Survey) Questionnaire 2011/12, 2010. Available: https://www.hpa.org.nz/sites/default/files/Questionnaire%20for%20HSC%20website-FINAL-120413.pdf [Accessed 02 Jun 2019].

- 47.Kypri K, Baxter J. Smoking in a new Zealand university student sample. N Z Med J 2004;117:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kypri K, Paschall MJ, Langley J, et al. . Drinking and alcohol-related harm among New Zealand university students: findings from a national web-based survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009;33:307–14. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00834.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bramley D, Riddell T, Whittaker R, et al. . Smoking cessation using mobile phone text messaging is as effective in Maori as non-Maori. N Z Med J 2005;118:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ministry of Health Presenting Ethnicity: Comparing prioritised and total response ethnicity in descriptive analyses of New Zealand Health Monitor surveys. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spindle TR, Hiler MM, Cooke ME, et al. . Electronic cigarette use and uptake of cigarette smoking: a longitudinal examination of U.S. college students. Addict Behav 2017;67:66–72. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alexander C, Piazza M, Mekos D, et al. . Peers, schools, and adolescent cigarette smoking. J Adolesc Health 2001;29:22–30. 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00210-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ling PM, Neilands TB, Glantz SA. Young adult smoking behavior: a national survey. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:389–94. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Health Sponsorship Council, InFact . Public opinion about tobacco regulation: health and lifestyle surveys 2008-2010. Wellington: Health Sponsorship Council, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Health Sponsorship Council, InFact . Public Opinion about a smokefree New Zealand. Wellington: Health Sponsorship Council, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 56.McNeill A. E-Cigarettes: an evidence update. A report commissioned by public health England. Public Health England 2015;3. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dunbar ZR, Giovino G, Wei B, et al. . Use of electronic cigarettes in smoke-free spaces by smokers: results from the 2014–2015 population assessment on tobacco and health study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:978 10.3390/ijerph17030978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Health Promotion Agency Data release: Updated preliminary analysis on 2016 Health & Lifestyle Survey electronic cigarette questions. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Etter J-F. Electronic cigarettes: a survey of users. BMC Public Health 2010;10:231. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee C, Yong H-H, Borland R, et al. . Acceptance and patterns of personal vaporizer use in Australia and the United Kingdom: results from the International tobacco control survey. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;185:142–8. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong LP, Mohamad Shakir SM, Alias H, et al. . Reasons for using electronic cigarettes and intentions to quit among electronic cigarette users in Malaysia. J Community Health 2016;41:1101–9. 10.1007/s10900-016-0196-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tan ASL, Bigman CA. E-Cigarette awareness and perceived harmfulness: prevalence and associations with smoking-cessation outcomes. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:141–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ministry of Education Students enrolled at New Zealand's tertiary institutions: Provider based enrolments - Statistical Tables [cited 05 Nov 2019], 2018. Available: https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/tertiary-education/participation

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035093supp001.pdf (99.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035093supp002.pdf (128.5KB, pdf)