Abstract

Little is known about factors impacting poor post-school outcomes for transition age students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Guided by the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) implementation science framework, we sought to better understand the interdependent impacts of policy, organizational, provider, and individual factors that shape the transition planning process in schools, and the subsequent process through which transition plans are implemented as youth access services and gain employment after school. We conducted focus groups with individuals with ASD, parents, classroom teachers, school administrators, adult service providers, and state policymakers (10 groups, n = 40). Participants described how core tenets of the individualized education planning process were not reliably implemented: planning was characterized by inappropriate goal-setting, ineffective communication, and inadequate involvement of all decision-makers needed to inform planning. After school, youth struggled to access the services stipulated in their transition plans due to inadequate planning, overburdened services, and insufficient accountability for adult service providers. Finally, a failure to include appropriate skill-building and insufficient inter-agency and community relationships limited efforts to gain and maintain employment. Diverse stakeholder perspectives illuminate the need for implementation efforts to target the provider, organizational, and policy levels to improve transition outcomes for individuals with ASD.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, transition planning, COMPASS, stakeholders, implementation science, EPIS

Introduction

Since 1990, U.S. federal education law has required public schools to provide transition services as part of the Individualized Education Program (IEP) for students with disabilities (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), 1990). The 2004 re-authorized IDEA (IDEA, 2004) defines transition services as a coordinated set of activities for a child with a disability that are: (a) designed to be a results-oriented process that is focused on improving the academic and functional achievement of the child with a disability to facilitate the child’s movement from school to post-school activities, including post-secondary education, vocational education, integrated employment, continuing and adult education, adult services, independent living, or community participation; and (b) based on the individual child’s needs, taking into account the child’s strengths, preferences, and interests (Sec. 1401). Further, transition planning should include IEP goals linked to post-secondary outcomes that are based on personalized strengths and interests of the student. The planning process, which must be explicitly enumerated in the IEP by the student’s 16th birthday, encourages a seamless transition by including IEP goals linked to post-secondary outcomes and allowing students with disabilities to stay in school until they earn a regular diploma or until their 22nd birthday.

The importance of transition planning and services was further emphasized by the U.S. Congress in 2014 by the passage of the Workforce Investment and Opportunities Act (WIOA). For individuals with barriers to employment, WIOA’s purpose was to increase “access to and opportunities for the employment, education, training and support services they need to succeed in the labor market” (Section 2). WIOA placed a special emphasis on students with the most significant disabilities, including students with intellectual and developmental disabilities and autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Despite legislative mandates to facilitate successful transitions for individuals with disabilities from school to adult life, transition planning and implementation are falling short for many students with ASD (Hendricks & Wehman, 2009; Kucharczyk et al., 2015) suggesting a gap between policy and practice. Compared to adults with other disabilities, post-school outcomes are the poorest for individuals with ASD, who have the lowest employment rate and the highest rate of no activities after school of any IDEA disability classification (Taylor & Seltzer, 2011). Further, the IEPs of individuals with ASD are more likely to have goals that require assistance or specify a non-competitive job setting (Cameto, Levine, & Wagner, 2004; Roux et al., 2013), and individuals with ASD are more likely to be living with parents and are least likely to have lived independently compared to those with learning, intellectual, or emotional disabilities (Anderson, Shattuck, Cooper, Roux, & Wagner, 2013). Students with ASD who do achieve independent living tended to be White, from households with higher incomes, and have higher adult daily/independent living skills levels (Chiang, Cheung, Li, & Tsai, 2013).

Unfortunately, our knowledge about the reasons behind these dismal findings is limited; a few studies have provided some insight. Kucharczyk and colleagues (2015) conducted a qualitative study with stakeholders to understand the issues associated with the use of evidence based practices (EBPs) during transition for students with ASD. Stakeholders noted a) few or no EBPs for transition (Wong et al., 2015) and b) that even those practices with some empirical support are limited by problems in implementation. In other words, transition practices were not delivered as intended, lacking the participation of vital personnel, active involvement of youth, and effective communication. Another common finding is the lack of student participation in transition planning (Geiseke-Smith, 2015) and the potential negative impact this has on post high school adjustment (Galler, 2013). Relatedly, frequently, plans to achieve postsecondary outcomes were left to students and parents to implement instead of educators (Ruble, McGrew, Wong, Adams & Yu, 2019). Moreover, most studies have tended to focus on narrow research questions, for example, identifying factors related to specific transition goals, such as attending college (Geiseke-Smith, 2015; Heck-Sorter, 2012), or the usefulness of specific strategies, including person-centered planning, to improve the IEP transition process (Hagner, Kurtz, May, & Cloutier, 2014; Ruble, McGrew, Toland, Dalrymple, Adams, & Snell-Rood, 2018).

However, as a best practice, transition planning is inherently cross-disciplinary and cross-organizational and thus unique: while the IEP process in schools is well studied as an evidence-based practice, transition planning’s ultimate implementation in employment and community settings is articulated as a set of mandated aspirational policies and guidelines/practices, without sufficient research to identify and define the specific intervention components that will lead to successful outcomes. Therefore, perhaps unsurprisingly, few to no studies have evaluated the complex, interwoven and multilevel factors across organizations and settings potentially impacting the transition process for students with ASD broadly. Thus, there is a need to understand further the multi-faceted barriers to transition planning, starting in schools and transitioning to community and employment settings. We employed qualitative methods to explore the processes contributing to poor transition outcomes for youth with ASD, using an implementation science framework to capture the perspectives of diverse policy, organizational, provider, and individual level stakeholders that shape transition processes and outcomes. As part of a larger intervention study, focus groups were conducted to understand how interacting policy, organizational, provider and individual-level factors shape different aspects of transition, namely, a) the transition planning process and implementation of the process that occurs in schools, and how young adults with ASD b) access services after graduation, and c) gain and maintain employment. We explored these aspects of transition (planning, adult services, and employment) through the lens of implementation science constructs adapted from the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) conceptual model (Aarons et al., 2014; Moullin et al., 2019). Drawing on these constructs, in each aspect of transition we studied, we examined 1) implementation practices (i.e., critical players, services, processes, outcomes); 2) barriers and facilitators; 3) the role of collaborative relationships (i.e., inter-agency, intra-organization, family-practitioner) and policies (i.e., federal, state, school); and 4) what additional measures could evaluate outcomes. In so doing, we will identify how implementation of existing EBPs can be improved and point toward additional best practices to strengthen different components of the complex transition process.

Method

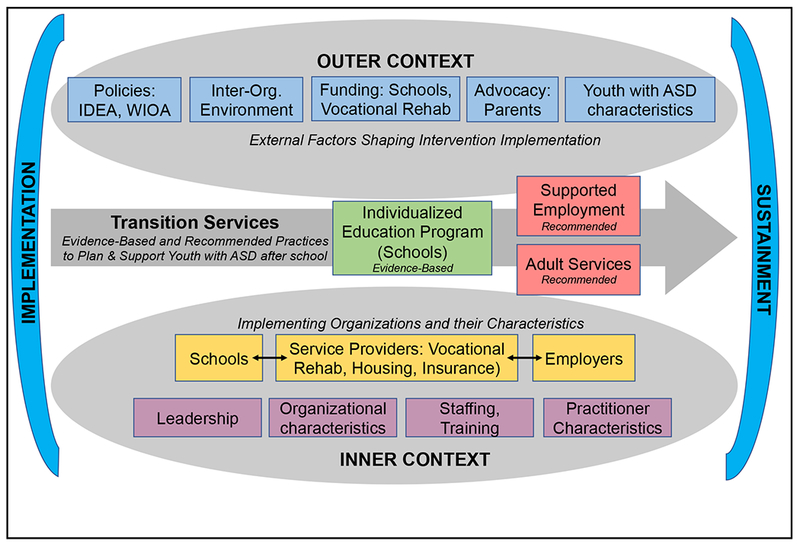

This study describes stakeholder perspectives from a larger project to adapt and test a consultation intervention called the Collaborative Model for Promoting Competence and Success (COMPASS) for transition age students. COMPASS is a manualized intervention (Ruble, Dalrymple, & McGrew, 2012) to improve IEP outcomes through systematic assessment of personal and environmental strengths and challenges that lead to selection of pivotal skills (social, communication, and learning/work skills) that underlie educational success and are notably impaired in children with ASD. As shown in Figure 1, the EPIS conceptual model assisted in the design and analysis of our study due to its focus on the interacting multi-level policies, long-term collaborative relationships, and organizational and provider factors that impact how best practices are sustained (Aarons et al., 2014; Moullin et al., 2019). In particular, we asked how these factors impacted the best practices critical to the implementation and sustainment of transition, such as IEPs, student-centered planning with key players, supported employment, and adult services. Unlike other implementation science models that concentrate on the factors supporting adoption and implementation of new EBPs, the focus on sustainment in EPIS enabled us to explore the ongoing inner context (organizational, practitioner-level) and outer context (inter-organizational, policy) that shape the numerous best practices vital to successful transition that have been mandated in policy since 2004.

Figure 1.

The EPIS framework shows interacting multi-level policies, collaborative relationships, and organizational factors that impact how Transition Services, as a complex intervention, is implemented long-term. Adapted from Moullin et al 2019.

Participants

Guided by implementation science sampling practices to maximize variation, we collected perspectives from stakeholders across varied roles (e.g., personnel) and contexts (e.g., patient/family, provider, systems-level) shaping implementation (Aarons & Palinkas, 2007). We conducted 10 focus groups with stakeholders (N = 40) representing the multiple contexts affecting implementation: individuals with ASD (N = 4), parents and caregivers (N = 16), school providers (classroom teachers; school psychologists; N = 3), school administrators (N = 4), adult service providers (service agencies; vocational rehabilitation counselor; N = 5), and state agency administrators, including directors of advocacy agencies and policy makers from vocational rehabilitation (VR), special education, Medicaid, and developmental disabilities (N = 8). Administrators of state agencies and school systems were approached directly about the study. Parents were recruited from a local parent support group and from a school serving low-income/resource parents. Names of school and adult providers were recommended by special education administrators, VR administrators, or from research team contacts. We recruited individuals with ASD who were college students attending the university where the principal investigator works. Our inclusion criteria included the ability to understand and speak English. Thus, only individuals with ASD who had verbal skills commensurate with chronological age were recruited.

There were 42 participants across the 10 focus groups, with 40 unique participants (see Table 1). Participant demographics, shown in Table 1, are broadly representative of the midwestern state in which all focus groups were conducted. The busy work schedules of our targeted groups limited focus group sizes. With the exception of the State Autism Committee, which had 10 participating members, groups consisted of two to four participants and were composed of individuals of similar role (e.g., parents) or title (e.g., school administrator) to ensure comfort in speaking openly about issues related to transition, school services, and adult services (Carey & Asbury, 2012).

Table 1.

Description of Participants

| Focus Group Name | Gender | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |

| 1. State Autism Committee | 8 | 2 |

| 2. Policymakers Group 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. Parent Group 1 | 4 | 0 |

| 4. Policymakers Group 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 5. School Providers | 4 | 0 |

| 6. Parent Group 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 7. School Administrators | 4 | 0 |

| 8. Adult Service Providers | 3 | 0 |

| 9. Individuals with ASD | 1 | 3 |

| 10. Parent Group 3 | 3 | 0 |

Note. Female participants were 88% White, 6% Black, and 6% Latina. All male participants were White.

Procedure

The moderator used a semi-structured interview to ask a series of open-ended questions guided by the EPIS framework concerning implementation (e.g., critical players, processes, and outcomes); barriers and facilitators to transition planning; collaborative relationships and policies; and suggested measures to evaluate additional outcomes (see Appendix 1). We made slight variations to questions to reflect participant roles and simplified questions for individuals with ASD. Focus groups were conducted by the second author and at least one research assistant and lasted about one hour. Participants were offered compensation of $50.

Focus group audio recordings were transcribed and entered into MAXQDA qualitative data analysis software. Initially, the first and second authors read interviews to identify primary themes in the data, which they defined in an initial codebook (Saldaña, 2013). Using an iterative, consensus-building process, research team members further refined the primary themes, developing a detailed codebook with code definitions, typical and atypical exemplars, and exclusions (Guest & MacQueen, 2008). The identified codes aligned with components of EPIS (e.g., related to implementation of best practices, collaborative relationships to support implementation). To ensure dependability among multiple investigators, coding pairs conducted inter-rater reliability tests of each code by applying codes to transcripts, discussing findings, and then refining code definitions until agreement reached at least 80%. Using the final codebook, we applied codes line by line to the interviews in coding dyads. These steps strengthened the trustworthiness of our findings through triangulating code definition across investigators and checking the individual coding processes through collaboration (Brantlinger, Jimenez, Klingner, Pugach, & Richardson, 2005). Sub-codes were then re-grouped to integrate them across key practices across the transition process to understand code interrelationships in producing poor transition outcomes. For ease of reading, some quotes in the results presented below have been edited. Lastly, we presented our results to the Kentucky Commission on ASD, subcommittee on transition and adult services for checking.

Results

Results are divided into three primary aspects of transition and further explicated in relation to constructs within the EPIS framework: 1) the planning process that takes place in schools to help students with ASD prepare for transition; 2) the struggle to initiate life beyond school; and 3) efforts to gain and maintain employment.

Transition Planning

Though participants commented on many individual successes in transition, all remarked that transition planning was plagued by problems. Planning was characterized by inappropriate goal-setting, ineffective communication between stakeholders, and inadequate involvement of all decision-makers needed to inform planning, echoing the critical role of collaborative relationships and the involvement of key players in planning as articulated within the EPIS model. Undergirding each of these limitations, planning did not account adequately for the full continuum of abilities within ASD.

Inadequate implementation of transition planning: goals.

Participants described how best practices in planning were designed to determine both what options are optimal for individuals with ASD after school and what skills would need to be acquired in the interim to fulfill those goals. As one parent stated, “I’ve always thought [transition planning] should begin with the end in mind.” Yet many participants described implementation of planning that was divorced from student abilities, needs, and talents. Parents in particular stressed how planning practices must include setting realistic goals, requiring planners to think beyond educational outcomes to student interests and abilities. “Instead of just how many word sentences can they average,” explained one parent, planners should “get to know [students] and what they do like and what they can do in their spare time.” Parents and school providers suggested that appropriate vocational interest inventory tools and exposing students to more options in the community could generate more imaginative goals.

Inadequate implementation of transition planning: assessment.

Many participants reported frustration with the way student abilities were assessed—with the consequence that goals often were inappropriate. In some cases, parents felt that transition planners, including VR, formulated inadequate goals: “they go to the very lowest level and it’s like ‘they just can’t do this’ and ‘they can’t do that’” instead of raising the bar and saying ‘yes, I think they might be able to do this.’” Conversely, other parents expressed frustration that unrealistic goals were set for their children that surpassed their abilities: “Instead of saying this kid’s going to college, we [need to] just say this kid’s going to graduate from school and he is going to be able to ride the bus and go downtown, maybe get his own apartment.” Many commented that transition planning was better tailored to meet the needs of students with average IQ, leaving many students with intellectual disability with insufficient planning. In other cases, because parents assumed that students would continue to live at home, there was inadequate planning for where the individual would reside when living with parents was no longer an option. Participants of all groups felt that continued education to prepare for jobs was not given adequate consideration. To produce more equitable outcomes, transition planning needed to be highly individualized to account for the range of skills present on the spectrum. Further, several barriers to planning were identified, for example, transition planning needed to accommodate the logistical hurdles that many parents faced in participating and the obstacles they faced in supporting their children after school due to social and economic conditions.

Inadequate implementation of transition planning: skill building.

Parents and school providers noted that inappropriate goal setting led to inappropriate plans to identify and develop individuals’ skills. One parent recounted that when meeting with vocational rehabilitation, she had no answer to the counselor’s question about her child’s job skills because this had not been accounted for in planning: “Well, who teaches them the job skills?” Parents felt that schools prioritized educational skills over the skills more relevant to reaching long-term goals in independent living and employment. Explained one parent: “It doesn’t matter if they can, you know, quote the Pythagorean Theorem if they’re telling someone ‘well you have a big nose, your hair looks bad.’ They’re not going to get very far.” Several noted that many schools did not provide necessary skills for specific jobs, safety, independent living, money management, and taking public transit.

Collaborative relationships required for EBP unclear.

IEP meetings were viewed as crucial for facilitating transition planning, but across the board, participants agreed that success was limited by ineffective communication processes and decision-making, as well as absences of key players. Some parents felt that meetings were dominated by unfamiliar language that prevented their meaningful participation in assessing student abilities and goal-setting. One parent complained, “You go into these IEP meetings and they start putting all these terms to things that the teachers all understand, but you’re like listening to them just like what?” In response, parents did not ask questions about crucial services and remained confused about what to expect. Other parents simply did not participate due to lack of awareness about the purpose of meetings, negative experiences at schools, or work demands. At times, all players’ fears of overstepping prevented effective action.

Organizational resources and policies for adult services not made available through transition planning.

All participants agreed that student outcomes greatly depended on which transition team members were involved in IEP meetings. Discussion needed to include a thorough review of the advantages and drawbacks of using particular benefits, such as Medicaid waiver services. The providers that would often be vital to students’ success post-transition frequently were not included within transition meetings, much less potential employers. This could impact students with the most significant disabilities most profoundly, because of their increased reliance on these services after school. Thus, many students scrambled to connect to services after transition, making uninformed decisions. One service provider bemoaned the long-term service consequences of these exclusions: “[Individuals and parents] don’t even get to hear what is voc rehab and what will it do from now ‘til, you know, ‘til the grave basically. Or what is Michelle P. [the state’s non-residential Developmental Disabilities (DD) Waiver]? What is SCL [Supports for Community Living, the state residential DD Waiver]? Because they’re only there for an hour and it’s all focused on the academics and what’s on the IEP.” However, without enough information on regulations related to salary caps affecting Medicaid or Supplemental Security Income (SSI), many individuals with ASD were discouraged from pursuing any employment at all, fearful they would lose benefits (cf., Turcotte et al., 2015). VR counselors played a crucial role in explaining how individuals could work and still receive the benefits they were entitled to. Yet VR counselors were frequently absent from meetings due to large caseloads that limited their ability to participate. In some places, however, highly successful transition outcomes were due to strong leadership within schools or particularly strong VR personnel.

Responsibility for planning implementation shifts from practitioners to families.

The onus of transition planning, many parents felt, was placed on them. Despite the group participation in planning meetings, one parent complained, “It’s up to the parent, like after you leave that meeting, everyone says they’re going to do all of this stuff and nothing gets done.” Parents who felt overburdened by responsibilities in the transition meeting suggested that meetings should not only identify the necessary steps, but also who is responsible for implementing them. In contrast, providers and teachers noted conflict between student needs and parental support, particularly when parents advocated for outcomes that conflicted with student needs or desires.

Practitioners not identified for implementation of transition planning over long-term.

Respondents noted that schools were good at setting the goals, but implementation was often the challenge, commented one parent: “I was looking [at the goals] and I was like ‘Wow, these are great IEP objectives. If only they would have done them!’” At present, schools are not accountable to reach the IEP goals—leading some school administrators and policy makers to wonder if a standard of measurement could influence the planning process. In addition, many parents and policymakers hoped for resources that could provide a map of the options available to young adults with ASD that would “guide you through the next ten years.” Such a resource could inform parents and individuals to be better prepared before IEP meetings, and could also enable networking and advocacy among families.

As outlined by EPIS, an EBP requires identification and involvement of the key critical players acting conjointly within a set of interdisciplinary collaborative relationships to provide effective services. In contrast, as noted consistently by several participants above, transition planning lacked an inter-organizational structure to support and sustain collaborative planning and implementation of services. Key players tended to operate within separate and usually different organizational policies, goals and priorities that supported their unique mandates (employment, academic achievement) with no clear process for creating and sustaining the kind of integrative planning and goals needed for successful transition.

Steps to improve implementation of transition planning.

Participants of all backgrounds suggested that IEP meetings could be improved by holding planning sessions beforehand to prepare participants to make decisions at the actual meeting. Direct, continued communication between school providers, families and individuals with ASD, and community providers would improve understanding and enable more educated decision-making. Collaborative, accessible language would ensure that meeting participation was more equitable. Many recommended that the key players (e.g., employer, service providers) needed for effective transition planning might vary depending on student needs.

“Like a Precipice”: Entering the World beyond School

Service capacity lacking for young adults post-transition despite policy mandates.

Rather than a transition, noted one policymaker, adults with ASD transitioning to the world beyond school face more of a “precipice.” School administrators, adult service providers, and policymakers reported that the gap between school and adult services often felt abrupt, with services not tailored to individual needs. Further, though policies directed that supportive services be provided for adults with disabilities, without a mandate, they lacked capacity to serve those in need. “Those adult programs,” noted one policymaker, “they have their limits and their waiting lists,” since service providers hesitate to “hold a place that you can bill somebody else.” After school, no one guided adults with ASD and their families through their options to access adult services including housing, social security, insurance, and transportation. Many families delayed applying for waiver programs until their children reached adulthood because they were unaware of the extensive waitlists entailed. But, an adult service provider noted, “you have to be in emergency status to even get funding for [a] residential [waiver]. If they’re living with mom and dad, that’s not [considered] a crisis.”

Inadequate oversight and accountability of implementation of adult services.

Another barrier to services was the decreased accountability for providing adult services. As one parent commented, “Many people in the schools do it with pleasure, not all, but many do. But they have a law. The law says they have to do a transition, they have to set goals. But when they are sent to another agency, there is no law.” If agencies claimed they lacked workers matching the needs of individuals, there were no forms of redress, even when the services were secured. After transition, one parent reported, some services, like VR, “start out strong and they fade away real quickly.”

Little training for adult service providers to work with adults with ASD.

Many providers had very little training on how to approach individuals with ASD and assess their needs, leaving families to fill the gap. Accordingly, participants stressed that it was vital for providers to have an existing relationship with them at the time of transition.

Policies differentiating between children and adults limit access to adult services.

After age 18, many students who had received special education services for ASD no longer qualified for community-based services because the eligibility criteria changed. Families played a crucial role in making the transition, yet they needed more support. As the student transitioned out of school, parents switched from advocating for a child to advocating for an adult—requiring learning an entirely new system of regulations related to guardianship and waivers. The effect was that many students eligible for waivers or Supplemental Security Income (SSI) did not apply, much less access the other services to which they were entitled. When parents were not involved there was a risk that the “systems take over,” decreasing the likelihood that individuals have an appropriate fit for their needs. To change this, one policymaker noted that there is a need for increased awareness: “we need to make sure families really understand what is out there and what might be available.” For individuals who did work, families had to negotiate asset limits which constituted a “huge, huge problem for families because when the child earns the money, you have to turn around and spend it. And spending it may not be the best thing for that child,” observed another policymaker. Yet not all adults with ASD had families who had the ability to advocate for them, let alone any family at all.

Need for collaborative community relationships to enhance best practices.

Parents and policymakers hoped that adults with ASD could have a meaningful role in the community, but agreed that further community investment was needed to make this happen. The help needed was both practical—to facilitate work, for instance—and also to provide a more enriching life. “A lot of what goes on after school,” commented one parent; “[is] related to being a member of clubs or being a part of a faith community or having friends.” Yet “if there aren’t connections made before [students with ASD] leave school”—whether to mentors, peers, other community members—then after transition, “there’s nothing, there’s no life for them, socially, to practice those social skills and to communicate in a safe way. They’re going to sit at home.” Such connections needed to be deliberately facilitated, because adults with ASD were unlikely to continue communicating with their high school peers. Building networks with older adults with ASD who had already made the transition would be particularly helpful. Community life was deemed essential—“She needs to be out and about. She needs to have something that gives her self-worth,” commented another parent.

Measurement of transition outcomes long-term.

It was essential that transition outcomes were measured long-term, including employment and independent living. Individuals with ASD mentioned that personal growth and the decrease of behavior supports should also be measured. It was important to continue to assess needs and re-evaluate goals even several years after transition, soliciting feedback from co-workers and community members as well.

Similar to the transition planning process, a lack of a collaborative structure with the capacity to support inter-organizational cooperation in goals, processes and services was a clear barrier to transition success. Moreover, critical transition service providers typically focus on goals, services and outcomes that are limited, non-integrative and constrained by traditional organizational structures and thus tend to miss the central point of transition, maximizing overall quality of life (e.g., housing independence, social integration).

Employment

Transition planning does not address educational benchmarks necessary for employment.

As participants reflected on employment outcomes, many wished that transition had included more extensive preparation for employment, both in terms of a diploma and the specific skills students would need. In the interest of accommodating different abilities, all schools in the state offered an alternative certificate/diploma to those individuals with ASD unable to complete the general diploma requirements. Yet for individuals with ASD pursuing employment, lacking a regular diploma made them ineligible for many jobs, noted parents and adult service providers. “You can’t even get a job at McDonald’s without a high school diploma,” explained one service provider; “And then they end up kind of with no leg to stand on, employment, education, whatever.”

Insufficient assessment of employment abilities, opportunities.

VR funds supported employment, but many parents and adult service providers expressed frustration that VR sometimes played a role in obstructing employment. For individuals with ASD, there were often assumptions about what jobs were appropriate. As one parent explained, “Some people have a box, [and they say] ‘These are the jobs that people like you can do…and they don’t look at job carving.” In some cases, VR counselors under-estimated individuals’ abilities, discounting their potential for employment. Participants noted that personal connections facilitated many job opportunities, but individuals with ASD often lacked those essential connections.

Need to implement job-specific support.

Parents and policymakers deemed it imperative that job agencies help provide supports to individuals throughout placement and employment. Explained one policy maker: “The single biggest barrier we have towards long-term employment for kids [is that] when they transition, there are very few services that are available to support them to keep their job.” All participants agreed on the continued need to provide training for specific work contexts. If individuals’ interests were defined before transition, they could be given internships and vocational training to prepare them for specific contexts, such as being a veterinary assistant. More pre-employment instruction would help assess students’ needs for further development “before we throw you through the front door and [you] lose the job,” as one adult service provider voiced. Participants explained the imperative that students learn the ability to describe their skills to employers, communicate with co-workers, and follow workplace norms.

Need for ongoing assessment of employment needs.

After some initial job experience, there was a need to re-evaluate individuals’ needs over the long-term, asserted parents, school and service providers. “What happens a lot of times,” explained one parent, is that individuals “get placed and they get stuck, and they don’t get to really realize that there are people that change their mind.” Job placement needed to be continuous. At the same time, employment was not always the best option—participants expressed ambivalence about how to identify when to quit exploring employment and form alternatives to employment.

Collaborative community relationships needed to support employment of young adults with ASD.

Some participants communicated frustration that their efforts to prepare individuals for the world of employment were wasted on a community not prepared for them. As one parent described, “you can educate and train the individual with autism to have all these pre-vocational skills and vocational skills, but if the community and the employers aren’t educated themselves, that’s gonna be an issue” (cf., Krieger et al., 2018). Employers simply did not hold an adequate understanding of ASD and consequently did not consider employing them, much less entertain how individuals could ultimately help their bottom line. Business owners needed to know that individuals with ASD are, as one school provider commented, “not gonna sit in the corner and play video games all day or rock or whatever. They have something that they can offer to your business or to your organization.” Once business owners understood types of disabilities, they could be encouraged to adjust the environment and envision how individuals could fit into their workflow.

Our findings show that poor implementation of identifying goals and building skills during the IEP process pose long-term barriers to employment for young adults with ASD. As adults, they find that there are few people in community and job-based roles to support their employment goals, much less little organizational structure to support their needs long-term.

Discussion

Our purpose was to identify the issues around transition planning and implementation of transition IEPs for students with ASD in the United States. As noted above, although transition planning and services are inherently cross-disciplinary and cross-organizational, in practice services tend to be segregated with poor integration, communication and collaboration across critical providers. Research also has tended to focus on narrow factors related to a single organization or level (e.g., the role of the schools in the annual transition IEP planning meeting), potentially missing the critical role of non-school related employment and community adult service providers (Committee on Children with Disabilities, 1999; Mason, Mc-Gahee-Kovac, & Johnson, 2004; Selembier & Furney, 1997; Southward & Kyzar, 2017; Wehman et al., 2014). To help understand the complex, multi-level barriers to transition planning and outcomes, we used an innovative multi-level implementation science approach. We employed the EPIS framework to parse the interrelationships between outer context factors (including policies, characteristics of individuals receiving the intervention) and inner context factors (including staffing, organizational characteristics) impacting the multiple organizations delivering transition services (schools, service providers, employers). Accordingly, we sought input from a variety of policy, organizational, provider, and individual level stakeholders that inform transition processes and outcomes. Drawing on these diverse perspectives, we gained a holistic understanding of how outcomes are impacted by the resources of individuals; the skills, involvement, and dedication of education and other providers; organizational processes of schools, employers, and providers; and policies at the school, community, and state levels. The close alignment between our findings and the factors outlined within the EPIS framework increases our confidence that we have understood and identified the important critical concerns.

Extending the work of others (Hendricks & Weyman, 2009; Kucharczyk et al., 2015), we identified processes and practitioners that limit the effectiveness of transition planning; and we found barriers and facilitators to implementing postsecondary plans to engage in services and gain employment. We attempted to address the perspectives of self-advocates and policymakers less emphasized in previous research, given the key role of policymakers in facilitating planning at the local level, and the essential voice of self-advocates in describing their own desired futures (Galler, 2013). In the following discussion, we discuss the implications of our findings for improving the implementation of transition planning and offer suggestions based on our findings on the ways that collaborative relationships and other best practices could strengthen access to services and employment.

Strengthening Implementation of Transition Planning

Implementation of high quality transition planning.

Though IEPs are, by definition, “individualized,” our study shows that in practice they often are not, with harsh long-term effects. Given the broad heterogeneity of students with ASD, there is a profound need for educators to reemphasize the importance of individualized transition goals that clearly reflect students’ needs, gifts, and interests (Kucharczyk et al., 2015; Ruble & Dalrymple, 1996). These goals must include measurable outcomes. There is a critical need to align functional and academic goals and programming between the high school and the student’s future environments (Findley, Wong, Ruble, & McGrew, 2019; Hagner et al., 2012), particularly because recent research shows that only a quarter of IEPs contain goals related to education/training, employment, and independent living (Findley et. al. 2019). Unless the transition team plans with the “end goal in mind” (as one respondent noted), the skills required to meet long-term goals will be unattainable for students with ASD.

Involving necessary providers and organizations in planning.

Respondents noted the problematic absence of key providers in the planning process. Even when present, providers’ effectiveness was compromised by an incomplete understanding of members’ roles; this was especially the case for parents who reported difficulty understanding the various roles and responsibilities of other team members, especially given preliminary findings that parents and students were the primary persons responsible for the implementation of plans related to postsecondary goals (Ruble, McGrew, Wong Adams, & Yu, 2019). The absence of individuals with ASD themselves also was a specific concern with potential deleterious impacts on transition outcomes (Galler, 2013). Respondents also noted that even the best transition goals were of little value if the team did not ensure the necessary services and supports, and if the team did not subsequently monitor the achievement of these goals, echoing other studies (Nuehring & Sitlington, 2003). Without multiple agencies coordinating long-term follow-up, young adults with ASD will face unnecessary breaks in services and diminished post-school outcomes.

Improving Implementation of Postsecondary Plans: The Need for Additional Best Practices

Identifying practitioners and processes to guide postsecondary plans.

In nearly all of our focus groups, the importance of educating families and students about the available resources to achieve post-school goals was a clear theme, again a finding that clearly points to the need for parent and student support for knowledge, skill and navigation. Recent intervention studies have demonstrated the importance of parent-mediated interventions for accessing the adult service system (Taylor, Hodapp, Burke, Waitz-Kudla, & Rabideau, 2017). Such interventions are critical given the myriad of post-school options, the range of potential resources, and bureaucratic literacy required to access resources. Transition processes must offer coherent and accessible information for both families and students in a way that maps out the process and responsible actors at each point. Moreover, when transitions were successful, it was attributed by several of our respondents to a transition “champion” who may have been part of the school system or adult services. This notion of a point-person in the process could perhaps be further developed into the idea of a transition navigator (Russa, Matthews, & Owen-DeSchryver, 2014) who would work with the student and the family across agencies to ensure the provision of needed services and supports, to answer questions, and to monitor outcomes—a position much more likely to enable success than referral alone.

Strengthening inter-agency relationships between schools and employers to improve planning and employment implementation.

Respondents consistently noted the need for students with transition goals of employment to have community-based opportunities early on to begin career exploration and learn job skills. Their perceptions are wholly consistent with the best predictors of employment for youth with significant disabilities: that community-based vocational evaluation and job training, and especially paid employment while still in high school, leads to positive post-school vocational outcomes (Carter, Austin, & Trainor, 2012; Test, 2012). Our findings suggest that education and developmental disability state agencies must work in close collaboration with VR to plan and implement WIOA services for transition-age students with ASD, that policy makers across these agencies proactively define and create these linkages, and that practitioners understand the specific plans related to job support, education, and post-secondary counseling in their state. Moreover, we should note the importance of Pre-Employment Transition Services (Pre-ETS), including job exploration counseling, work-based learning, job readiness training, post-secondary counseling, and instruction in self-advocacy (Work Force Innovation and Opportunities Act, Section 422). With WIOA, states are now mandated to expend a minimum of 15 percent of their federal match dollars on pre-employment transition services for youth with disabilities (WIOA, Sec. 419). These services align very strongly with the recommendations of our stakeholders, including providing more community-based options, training for specific work contexts, the use of vocational interest inventories, the development of job skills and work behaviors, and financial management, benefits counseling, and self-advocacy with employers.

Increasing the role of VR and the community through transition process.

Our respondents noted the need to educate broader elements of the community about youth and young adults with ASD. Thus, several of our participants commented on the importance of getting VR to the table, especially in the early years of the transition process, and insuring that VR counselors have a clear understanding of the needs, abilities, and challenges of their clients with ASD. Consistent with our findings, Nuehring and Sitlington (2003) identified the need for increased education of vocational service providers to improve transition planning. Moreover, echoing findings in the broader literature (Krieger et al., 2018), our respondents noted the importance of educating and preparing the community itself, including employers, about how employees with ASD can make valuable contributions to their businesses if given a chance.

Limitations

Although our focus group participants included four state policy leaders, we cannot assume that policymakers would have the same views in other states, given the heterogeneity among individual state contexts. We recruited school and adult service provider representatives from within urban and rural school districts, and parents and self-advocates from local ASD advisory and advocacy groups. Within the self-advocates group, only youth with ASD attending college participated. Their views may not be generalizable to other providers, or to other families and self-advocates. Though we made efforts to recruit parents from several low-income schools and held one focus group for Latino parents, our sample may have over-represented parents involved in ASD advocacy who possess a different experience of transition. Finally, we relied on the reported experiences of our focus group members.

Implications for Policymakers, Organizations, Providers, and Individuals with ASD and Families

For policymakers and organizations: Ensure that school, VR, and adult service agency providers have a common framework for transition that includes: a) an understanding of the roles and responsibilities of each; b) the evidence-based practices that do result in positive post-school outcomes for students with ASD; and c) the resources across agencies that can contribute to successful transitions. This framework can be created and sustained through inter-agency agreements and professional development requirements.

For policymakers and organizations: Create an inter-agency, long-term follow-up and tracking system to measure post-school success for former students with ASD. This would extend current practices in which school systems survey a sample of their former students with IEPs one year after graduation and VR conducts a 60-day follow-up of successfully placed clients.

For organizations: The option of transition navigators must be considered. Indeed, this role could clearly address the intent of WIOA, and could be jointly funded through schools and VR, in that VR is required to spend 15% of its federal match to address the pre-employment training needs of students with disabilities.

For providers and individuals/families: Individual student teams should consider using the pre-employment transition services noted under WIOA as designated IEP services to support measurable student goals. Self-advocacy training, work-based learning, and counseling on employment and post-secondary educational options reflect evidence-based practices promoting positive post-school outcomes for youth with disabilities.

Conclusion

The transition from school to the adult world is particularly problematic for those with ASD. Stakeholders identified a need for careful assessment and planning to craft appropriate goals and the strategies to achieve them and better linking of schools to multiple agencies, organizations, and people. However, all too often, individual, organizational, and policy barriers act to interfere with a successful transition. Clearly, further research is needed to understand these barriers and to identify and test interventions to address them. Just as the problem exists across multiple levels, solutions do as well: within and between the multiple organizations, agencies, and actors involved. Future research on interventions that focus on transition planning processes, including interagency communication and coordination is necessary.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant Number 5R34MH104208-02 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. We are grateful to the teachers, families, and children who generously donated their time and effort. We extend our thanks to special education directors and principals for allowing their teachers to participate.

Appendix 1: Focus Group Guide

- What are the critical elements of good IEP transition planning?

- What would we observe or see as a result of good transition planning?

- Who should be involved?

- Who are the critical players?

- What are the key services that we should be described in the transition plan?

- What are the main barriers or challenges now that make it difficult to achieve good IEP transition planning?

- What are policy barriers, funding, workforce, and interagency barriers?

- What are potential solutions to these challenges?

- Are any of these challenges particular to autism, or are some of these barriers common for other adults with intellectual disabilities?

- Let’s move now to discuss the implementation of the transition plan, how we go about achieving our goals. What are the critical elements of a good transition intervention?

- Specifically, what would we be able to observe with a good transition intervention?

- What services, agencies, organizations, federal, state and local that could/should be accessed and included?

- What are the main barriers or challenges for good transition intervention?

- What are policy barriers, funding, workforce, and interagency barriers

- What are potential solutions to these challenges?

- Are any of these challenges particular to autism, or are some of these barriers common for other adults with intellectual disabilities?

- Do you have plans in the place, short term or long term for changing your transition planning or intervention services?

- How do you know if transition planning has been successful (what intervention outcomes should we expect)?

- How does your agency currently measure transition outcomes?

- What are your future plans for measuring transition outcomes?

- How do you use the outcomes for changing, planning, or adapting your programs?

- How could we best observe this or know it has been achieved?

References

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Horwitz SM (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(1), 4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA & Palinkas LA Implementation of Evidence-based Practice in Child Welfare: Service Provider Perspectives. Adm. Policy Ment. Heal. Ment. Heal. Serv. Res. 34, 411–419 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KA, Shattuck PT, Cooper B, Roux AM, & Wagner M (2013). Prevalence and correlates of postsecondary residential status among young adults with and autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 18(5): 562–570. doi: 10.1177/1362361313481860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantlinger E, Jimenez R, Klingner J, Pugach M, & Richardson V (2005). Qualitative studies in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Cameto R, Levine P, & Wagner M (2004). Transition planning for students with disabilities: A special topic report of findings from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) (pp. 89). SRI International, Menlo Park, CA., USA: National Center for Special Education Research. 400 Maryland Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20202. Tel: 800-437-0833; Fax: 202-401-0689; Web site: http://ies.ed.gov/ncser/. [Google Scholar]

- Carey MA, & Asbury J (2012). Focus group research. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carter E, Austin D, & Trainor A (2012). Predictors of postschool employment outcomes for young adults with severe disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 23, 50–63. doi: 10.1177/1044207311414680 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang HM, Cheung YK, Li H, & Tsai LY (2013). Factors associated with participation in employment for high school leavers with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(8), 1832–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Children With Disabilities. (1999). The pediatrician’s role in development and implementation of an Individual Education Plan (IEP) and/or an Individual Family Service Plan (IFSP). Pediatrics, 104(1), 124–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley JA, Wong WH, Ruble LA, McGrew JH (2019). Preliminary investigation of individualized education program quality for transition age youth with autism. Manuscript in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Friedman N, Warfiled M, & Parish S (2013). Transition to adulthood for individuals with autism spectrum disorders: Current issues and future perspectives. Neuropsychiatry, 3(2), 181–192. doi: 10.2217/npy.13.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galler C (2013). Voice of young adults with autism and their perspective on life choices after secondary education. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. [Google Scholar]

- Geiseke-Smith KM (2015). Transition services in the public school system for adolescents with ASD. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, & MacQueen K (2008). Handbook for team-based qualitative research. Lanham: Altamira. [Google Scholar]

- Hagner D, Kurtz A, May J, & Cloutier H (2014). Person-Centered Planning for Transition-Aged Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Rehabilitation, 80(1), 4–10. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1587-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagner D, Kurtz A, Cloutier H, Arakelian C, Brucker DL, & May J (2012). Outcomes of a family-centered transition process for students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 27(1), 42–50. doi: 0.1177/1088357611430841 [Google Scholar]

- Heck-Sorter BL (2012). A qualitative case study exploring the academic and social experiences of students with ASD on their transition in to and persistence at a 4 year public university. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks DR, & Wehman P (2009). Transition from school to adulthood for youth with autism spectrum disorders: Review and recommendations. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(2), 77–88. doi: 10.1177/1088357608329827 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (1990). Public Law 101-476.

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (2004). 20 U.S.C. § 1401.

- Kucharczyk S, Reutebuch CK, Carter EW, Hedges S, El Zein F, Fan H, & Gustafson JR (2015). Addressing the needs of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Considerations and complexities for high school interventions. Exceptional Children, 81(3), 329–349. doi: 10.1177/0014402914563703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason CY, McGahee-Kovac M, & Johnson L (2004). How to help students lead their IEP meetings. Teaching Exceptional Children, 36(3), 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Rabin B, & Aarons GA (2019). Systematic review of the exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implementation Science, 14(1), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuehring ML, & Sitlington PL (2003). Transition as a vehicle moving from high school to an adult vocational service provider. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 14(1), 23–35. doi: 10.1177/088572889702000106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roux AM, Shattuck PT, Cooper BP, Anderson KA, Wagner M, & Narendorf SC (2013). Postsecondary employment experiences among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(9), 931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble LA, & Dalrymple NJ (1996). An alternative view of outcome in autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 11(1), 3–14. doi: 10.1177/108835769601100102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble LA, Dalrymple NJ, & McGrew JH (2010). The effects of consultation on Individualized Education Program outcomes for young children with autism: The Collaborative Model for Promoting Competence and Success. Journal of Early Intervention, 32(4), 286–301. doi: 10.1177/1053815110382973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble LA, Dalrymple NJ, McGrew JH (2012). Collaborative model for promoting competence and success for students with ASD. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-2332-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble LA, McGrew JH, Toland M, Dalrymple N, Adams M, & Snell-Rood C (2018). Randomized control trial of COMPASS for improving transition outcomes of students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble L, McGrew J, Wong V, Adams M, & Yu Y (2018). A Preliminary Study of Parent Activation, Parent-Teacher Alliance, Transition Planning Quality, and IEP and Postsecondary Goal Attainment of Students with ASD, manuscript revised and resubmitted. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ruble LA, McGrew JH, Toland MD, Dalrymple NJ, & Jung LA (2013). A randomized controlled trial of COMPASS web-based and face-to-face teacher coaching in autism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 81(3), 566–572. doi: 10.1037/a0032003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russa MB, Matthews AL, & Owen-DeSchryver JS (2014). Expanding supports to improve the lives of families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 17(2), 95–104. doi: 10.1177/1098300714532134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Salembier G, & Furney KS (1997). Facilitating participation: Parents’ perceptions of their involvement in the IEP/transition planning process. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 20(1), 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sanford C, Newman L, Wagner M, Cameto R, Knokey AM, & Shaver D (2011). The post-high school outcomes of young adults with disabilities up to 6 years after high school: Key findings from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) (NCSER 2011-3004) (pp. 106). Menlo Park, CA: SRI International. [Google Scholar]

- Shogren K, Wehmeyer M, Palmer S, Rifenbark G, & Little T (2015). Relationships between self-determination and postschool outcomes for youth with disabilities. Journal of Special Education, 48, 256–267. doi: 10.1177/0022466913489733 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Southward JD, & Kyzar K (2017). Predictors of competitive employment for students with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 52(1), 26. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, & Seltzer MM (2011). Employment and post-secondary educational activities for young adults with autism spectrum disorders during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(5), 566–574. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1070-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Hodapp RM, Burke MM, Waitz-Kudla SN, & Rabideau C (2017). Training parents of youth with autism spectrum disorder to advocate for adult disability services: Results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(3), 846–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Test D (2012). Evidence-based instructional strategies for transition. Baltimore: Paul Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte PL, Côté C, Coulombe K, Richard M, Larivière N, & Couture M (2015). Social participation during transition to adult life among young adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: Experiences from an exploratory multiple case study. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 31(3), 234–252. [Google Scholar]

- Wehman P, Schall C, Carr S, Targett P, West M, & Cifu G (2014). Transition from school to adulthood for youth with autism spectrum disorder: What we know and what we need to know. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 25(1), 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wong C, Odom SL, Hume KA, Cox AW, Fettig A, Kucharczyk S, Brock M, Plavnick J, Fleury V, & Schultz TR (2015). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 1951–1966. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2351-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Work Force Innovation and Opportunities Act (WIOA), PL 113-128, Stat. 1425. Retrieved from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-113publ128/pdf/PLAW-113publ128.pdf