Introduction

Currently around one in five children in the US are obese.1 Obese children are more likely than normal weight children to remain obese as adults,2–6 and more likely to develop diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer at a younger age and face shorter life expectancies.6–14 Higher population levels of obesity are attributed to a number of factors, including consuming food outside the home, consuming larger portion sizes and high intake of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs).15–19 Recent research has suggested a plateauing of obesity levels in children and adolescents20,21 and a decline in energy intakes of US households with children.22 Despite these declines, around two thirds of dietary energy still derives from highly-processed food sources.23–26 More recently an important crossover RCT by Hall et al showed that a diet of ultra-processed foods was linked with 2.4lbs weight gain over two weeks. In contrast, subjects had an average weight loss of 2lbs in two weeks when switching from an ultra-processed diet to a less processed one,27 clarifying the significance of the many studies linking ultra-processed foods with lower dietary quality,28 higher obesity prevalence,27,29,30 and all-cause mortality.31 Previous studies have also shown that disparities in dietary quality exist in certain demographic subgroups,32,33 and that non-Hispanic black children and adolescents and lower income households had the largest increase in snack food intake over the past 35 years.34

In the US, the term “junk foods” is often used to describe commonly-known “less healthy” food categories such as confectionery, ice cream and salty snacks. In the literature, the term is often used when observing the effects of bans on marketing to children, or in relation to “junk food” taxes. Both marketing bans and junk food taxes usually involve a set of inclusion/exclusion criteria. For example, both Mexico and Hungary have implemented “junk food” taxes, with cutoffs for energy density (Mexico) and salt, sugar and caffeine (for Hungary) used to determine what qualifies as “junk food” to be taxed.35–37 However, there is no consistent definition. Increasingly, studies have begun using degree of food processing to define less healthy foods (e.g. “ultra-processed” versus “minimally processed”).26,38 Nutrient profiling is also used in multiple countries to support consumers in identifying healthier products.39

In 2016, Chile implemented the most comprehensive set of obesity-preventive regulations to date in the world, including strict regulations for the marketing of foods to children.40,41 This law was based on a nutrient profiling model that delineated foods high in total sugar, saturated fat, sodium or calories using both nutrient levels and the presence of added sugar, salt and saturated fat ingredients (as a proxy for degree of processing). Since Chile’s ground-breaking regulations, similar warning labels have been adopted in Israel,42 Peru and Uruguay. Chile’s regulations came in three phases of increasing stringency. All subsequent countries that adopted this type of regulation began with criteria close to Chile’s second phase.

In this study, the proportion of calories and nutrients of concern consumed by children and adolescents in the US that would be considered “junk food” using the Chilean regulation’s phase 2 nutrient criteria and whether these changed between 2003-2016 was examined. In addition, the proportion of calories and nutrients of concern consumed by children and adolescents in the US that would be considered “junk food” in 2013-16 using the Chilean regulation’s phase 2 nutrient criteria as well as the regulation’s ingredient criteria was examined.

Methods

Survey population:

Data were obtained from four nationally representative surveys of food intake in 13,016 US children and adolescents: NHANES 2003–2004, NHANES 2005– 2006 (NHANES 03–06), NHANES 2013-14 and NHANES 2015-2016 (NHANES 13-16) (Table 1). NHANES is based on a multistage, stratified area probability sample of noninstitutionalized US households. Detailed information about each survey and its sampling design has been published previously.43 By utilizing secondary USDA and NHANES data, we were exempt from institutional review board concerns.

Table 1:

Sociodemographic characteristics for US children <=18 years

| 2003-06 | 2013-16 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of observations | 7,336 | 5,680 |

| % Male | 49.4 | 50.4 |

| Age group (%) | ||

| 2-5 years | 22.8 | 23.8 |

| 6-11 years | 26.1 | 36.7 |

| 12-18 years | 51.2 | 39.4 |

| Race-ethnicity (%) | ||

| Mexican American | 31.6 | 22.2 |

| Other Hispanic | 3.4 | 11.2 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 27.3 | 27.9 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 32.6 | 23.8 |

| Other race | 5.2 | 14.9 |

| Household income (%) | ||

| <185% Federal Poverty Level | 55.7 | 57.9 |

| 185-350% Federal Poverty Level | 23.6 | 22.4 |

| >350% Federal Poverty Level | 20.8 | 19.7 |

| Head of household education (%) | ||

| Less Than High School Diploma | 32.2 | 23.9 |

| High School Diploma | 24.8 | 22.1 |

| More Than High School Diploma | 43.0 | 54.1 |

Junk food definition:

While the Chilean regulation was first implemented in 2016, the nutrient thresholds were set to become increasingly stringent over a series of three implementation dates, beginning in 2016 and ending in 2019. The phase 2 criteria were utilised for this analysis, on the basis that these criteria are most widely used in the literature and were adopted by Israel after seeing the extensive reformulation industry undertook after the first phase of the Chilean regulations.37,42 Nutritional content of each food consumed in NHANES was compared to the Phase 2 thresholds from the Chilean regulation for energy, saturated fat, total sugars and sodium per 100g (Supplementary Table 1).41 Products that exceeded the nutrient thresholds were considered “junk foods” in this analysis and will be referred to as “junk foods” throughout this paper. The Chilean regulation also includes an ingredient criterion, with products containing added sugars (e.g. sucrose), saturated fat (e.g. palm oil) or sodium (e.g. table salt) ingredients as well as exceeding the nutrient criteria considered junk foods. Ingredient data for NHANES 2003-06 was not available for this research, and so we have not included the ingredient criteria in our change analysis. However, Steele et al24,25 have recently used the NOVA classification to identify products in NHANES that would be considered “ultra-processed” based on added saturated fat, sugar and salt ingredients. This team, along with collaborators at the CDC, provided data identifying products from NHANES 2013-16 that have added sugar, added saturated fat and/or added salt ingredients. Using these data, overall results for 2013-16 are shown using both the nutrient criteria alone, and also including the added ingredient criteria in the Chilean regulation (Supplementary Figure 1). For sensitivity analyses duplicate results tables for Chile’s much more stringent phase 3 criteria are available upon request from the authors.

Dietary data:

To examine trends over time from surveys with different collection methods on days 1 and 2, the first day’s data (a single, interviewer-administered 24-h dietary recall) collected from each individual was used (as recommended by the USDA) and appropriate weights and adjustments were used for the sample design provided.

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) food grouping system:

All foods reported in the USDA surveys were assigned to one of UNC-CH’s food groups.44 To determine which food groups to focus on in reporting, data were pooled for all survey years (2003-2016). In order to focus on food categories of interest the analysis was limited to categories with >50% of products classified as junk food under the Chilean Phase 2 nutrient criteria. All remaining food sources were grouped together (Supplementary Table 2). Mean intake and proportion of calories, saturated fat, total sugar and sodium provided by each food category was calculated.

Statistical analysis:

Analysis was undertaken in 2019. Junk food intake was examined using three age groups (2-5 y, 6-11 y, and 12-18 y), five race-ethnic groups (Mexican-American, Other Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black and Other Race), two genders (Male and Female), three income groups (<185%, 185-350% and >350% of the Federal Poverty Level) and three head of household education groups (less than high school, high school diploma, and more than high school). Mean intake and proportion of calories and other nutrients of concern deriving from junk food overall and within each food category within each subgroup was determined, as were the mean number of junk food items consumed per day. The proportion of foods and beverages consumed by NHANES participants that were considered “junk food” was also calculated. Survey methods were used within STATA to account for the clustering that is inherent in the NHANES sampling methodology and weighting for national representativeness, so as to allow statistically significant differences between survey cycles to be identified using Student’s t-test. Unadjusted models were used to ensure the representativeness of the US population was maintained in each survey cycle examined. A p-value of <0.01 was considered significant. STATA version 14.1 was used for analysis.

Results

Overall intake trends

Between 2003-06 and 2013-16 there was an almost 10 percentage point decrease (71.1% to 61.3%; p<0.01) in the proportion of foods consumed by US children and adolescents that were classified as junk food under the Chilean nutrient criteria (Table 2). A significant decrease was seen in mean intake and proportion of intake of calories (1610 to 1367 kcal/d; p<0.01), total sugar (88.8 to 64.2g/d; p<0.01), saturated fat (22.6 to 20.5g/d; p<0.01) and sodium (2306 to 2044mg/d; p<0.01) deriving from junk foods between survey years (Table 3). Between 2003-06 and 2013-16 the mean number of junk food items consumed each day decreased from 10.1 to 8.4 (p<0.01; Table 3). Despite this, almost 75% of calories consumed and 90% of total sugars consumed in 2013-16 derived from junk foods (Table 3).

Table 2:

Proportion of food reported consumed by US children and adolescents classified as junk foods in NHANES 2003-2016, by food category

| All Children | Age 2-5y | Age 6-11y | Age 12-18y | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003-06 | 2013-16* | 2013-16** | 2003-06 | 2013-16* | 2013-16** | 2003-06 | 2013-16* | 2013-16** | 2003-06 | 2013-16* | 2013-16** | |

| Ready-to-eat cereals | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 99.9 |

| Confectionery | 99.9 | 98.2 | 98.2 | 99.8 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 99.9 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 99.9 | 98.2 | 98.2 |

| Dairy with added sugar | 99.9 | 99.9 | 87.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 76.3 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 92.6 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 89.7 |

| Salty snacks | 99.9 | 100.0 | 99.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 98.7 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 99.4 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 98.9 |

| Processed meat, poultry and fish | 99.4 | 98.5 | 79.5 | 97.9 | 98.6 | 81.4 | 100.0 | 98.7 | 80.0 | 99.8 | 98.3 | 77.8 |

| Breads | 66.2 | 44.7 | 44.6 | 72.4 | 42.9 | 42.9 | 69.0 | 45.4 | 45.3 | 60.3 | 44.9 | 44.9 |

| Juices | 98.1 | 94.4 | 1.2 | 98.7 | 92.5 | 0.7 | 97.3 | 95.2 | 1.7 | 98.1 | 95.6 | 1.4 |

| Cheese & cheese products | 97.6 | 98.5 | 33.2 | 97.1 | 97.2 | 31.6 | 95.7 | 98.4 | 34.4 | 99.4 | 99.3 | 33.2 |

| Desserts | 92.3 | 93.1 | 89.9 | 89.7 | 90.2 | 88.9 | 92.0 | 91.8 | 88.0 | 94.5 | 97.0 | 92.9 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | 90.4 | 87.8 | 86.7 | 87.1 | 87.9 | 86.4 | 90.2 | 87.1 | 86.0 | 91.7 | 88.5 | 87.5 |

| Sandwiches, burgers and pizzas | 79.9 | 76.8 | 69.5 | 80.0 | 80.4 | 72.9 | 81.7 | 78.9 | 72.1 | 78.4 | 73.4 | 65.7 |

| All other foods | 49.4 | 38.4 | 16.1 | 50.8 | 39.4 | 13.3 | 49.7 | 39.4 | 16.9 | 48.2 | 36.7 | 17.2 |

| Total for all foods | 71.1 | 61.3 | 43.5 | 71.3 | 61.4 | 39.8 | 71.8 | 63.1 | 45.9 | 70.2 | 59.6 | 43.5 |

junk food is defined by utilizing the Chilean nutrition profile model phase 2 nutrient criteria

junk food is defined by utilizing the Chilean nutrition profile model phase 2 nutrient criteria in addition to the NOVA criteria for level of processing to identify products with added sugar, saturated fat and sodium ingredients

Table 3:

Nutrient intake deriving from junk food sources overall and by demographic subgroup

| Junk food items, n/d | Per capita energy intake from junk food | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003-06 | 2013-16 | 2013-16# | 2003–2006 | 2013-16 | 2013-16# | ||||

| Mean intake (kcal/d) | % total energy intake | Mean intake (kcal/d) | % total energy intake | Mean intake (kcal/d) | % total energy intake | ||||

| All children, 2-18 years | 10.1 | 8 4** | 6.0 | 1610 | 77.0 | 1367** | 72.2** | 1072* | 56.6* |

| Age group | |||||||||

| 2–5 years | 11.2 | 9.3** | 6.0 | 1256 | 76.1 | 1070** | 71.9** | 784* | 52.7* |

| 6-11 years | 10.7 | 9.2** | 6.7 | 1615 | 78.0 | 1428** | 73.6** | 1151* | 59.3* |

| 12-18 years | 9.0 | 7.4** | 5.4 | 1792 | 76.6 | 1470** | 71.2** | 1157* | 56.0* |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Males | 10.3 | 8.6** | 6.1 | 1774 | 77.7 | 1510** | 73.4** | 1178* | 57.3* |

| Females | 9.9 | 8.3** | 5.8 | 1436 | 76.3 | 1210** | 71.0** | 963* | 56.5* |

| Head of household education | |||||||||

| Less Than High School Diploma | 9.4 | 7.7** | 5.4 | 1490 | 74.7 | 1282** | 69.3** | 993* | 53.7* |

| High School Diploma | 10.2 | 8.2** | 6.0 | 1666 | 78.5 | 1337** | 72.8** | 1045* | 56.9* |

| More Than High School Diploma | 10.3 | 8.8** | 6.2 | 1618 | 76.9 | 1412** | 73.1** | 1112* | 57.6* |

| Household income | |||||||||

| <185% Federal Poverty Level | 9.8 | 8.0** | 5.7 | 1579 | 76.5 | 1330** | 71.7** | 1043* | 56.2* |

| 185-350% Federal Poverty Level | 10.0 | 8.7** | 6.1 | 1618 | 78.4 | 1408** | 72.9** | 1092* | 56.6* |

| >350% Federal Poverty Level | 10.5 | 9.0** | 6.3 | 1654 | 76.7 | 1407** | 73.1** | 1113* | 57.8* |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Mexican American | 9.5 | 7.7** | 5.5 | 1489 | 73.1 | 1290** | 70.4** | 994* | 54.2* |

| Non-Hispanic White | 10.4 | 8.9** | 6.2 | 1682 | 78.9 | 1410** | 74.6** | 1096* | 58.0* |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 9.6 | 8.2** | 6.2 | 1564 | 76.4 | 1369** | 71.4** | 1134* | 59.2* |

| Per capita saturated fat intake from junk food | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2006 | 2013-16 | 2013-16# | ||||

| Mean intake (g/d) | % intake | Mean intake (g/d) | % intake | Mean intake (g/d) | % intake | |

| All children, 2-18 years | 22.6 | 71.1 | 20.5** | 61.3** | 14.5* | 43.4* |

| Age group | ||||||

| 2–5 years | 18.1 | 71.3 | 16.2** | 61.4** | 10.4* | 39.5* |

| 6-11 years | 22.8 | 71.8 | 21.9 | 63.1** | 16.1* | 46.5* |

| 12-18 years | 24.9 | 70.2 | 21.5** | 59.6** | 15.3* | 42.3* |

| Sex | ||||||

| Males | 25.0 | 71.9 | 22.6** | 62.8** | 16.0* | 44.4* |

| Females | 20.2 | 70.1 | 18.3** | 59.9** | 13.0* | 42.6* |

| Head of household education | ||||||

| Less Than High School Diploma | 21.1 | 70.0 | 19.3 | 60.8** | 13.6* | 42.8* |

| High School Diploma | 23.4 | 73.1 | 19.5** | 63.4** | 13.7* | 44.6* |

| More Than High School Diploma | 22.7 | 70.4 | 21.3** | 61.0** | 15.1* | 43.3* |

| Household income | ||||||

| <185% Federal Poverty Level | 22.3 | 71.3 | 19.3** | 62.2** | 13.8* | 44.5* |

| 185-350% Federal Poverty Level | 22.4 | 72.5 | 21.6 | 61.8** | 15.1* | 43.1* |

| >350% Federal Poverty Level | 23.4 | 69.8 | 21.5** | 60.2** | 15.2* | 42.7* |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Mexican American | 20.5 | 68.0 | 19.0 | 60.4** | 13.5* | 42.8* |

| Non-Hispanic White | 23.9 | 72.2 | 21.7** | 62.4** | 15.1* | 43.3* |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 21.2 | 72.0 | 18.6** | 63.8** | 14.3* | 49.1* |

| Per capita total sugar intake from junk food | ||||||

| 2003–2006 | 2013-16 | 2013-16# | ||||

| Mean intake (g/d) | % intake | Mean intake (g/d) | % intake | Mean intake (g/d) | % intake | |

| All children, 2-18 years | 88.8 | 93.9 | 64.2** | 90** | 58.8* | 82.4* |

| Age group | ||||||

| 2-5 years | 57.7 | 92.4 | 41.2** | 86.9** | 38.3* | 80.7* |

| 6-11 years | 88.1 | 94.5 | 65.8** | 90.5** | 61.0* | 83.9( |

| 12-18 years | 105.9 | 94.2 | 74.7** | 91.2** | 67.6* | 82.5* |

| Sex | ||||||

| Males | 99.9 | 94.2 | 71.4** | 90.5** | 65.4* | 82.9* |

| Females | 77.1 | 93.6 | 56.7** | 89.6** | 52.0* | 82.2* |

| Head of household education | ||||||

| Less Than High School Diploma | 80.3 | 94.2 | 59.9** | 89.5** | 54.2* | 80.9* |

| High School Diploma | 94.9 | 94.5 | 65.0** | 90.8** | 58.9* | 82.2* |

| More Than High School Diploma | 88.8 | 93.5 | 65.8** | 89.9** | 60.8* | 83.0* |

| Household income | ||||||

| <185% Federal Poverty Level | 85.5 | 94.4 | 62.8** | 89.8** | 57.8* | 82.6* |

| 185-350% Federal Poverty Level | 92.6 | 93.7 | 66.3** | 89.8** | 59.5* | 80.5* |

| >350% Federal Poverty Level | 90.8 | 93.5 | 65.1** | 90.2** | 60.0* | 83.2* |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Mexican American | 79.8 | 94.7 | 54.4** | 90.1** | 50.2* | 83.1* |

| Non-Hispanic White | 93.4 | 93.9 | 67.9** | 90.4** | 61.1* | 81.4* |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 87.1 | 94.5 | 68.3** | 90.1** | 64.2* | 84.7* |

| Per capita mean sodium intake from junk food (mg) | ||||||

| 2003–2006 | 2013-16 | 2013-16# | ||||

| Mean intake (mg/d) | % intake | Mean intake (mg/d) | % intake | Mean intake (mg/d) | % intake | |

| All children, 2-18 years | 2306 | 72.1 | 2044** | 67.1** | 1681* | 55.2* |

| Age group | ||||||

| 2-5 years | 1705 | 70.8 | 1523** | 67.9 | 1227* | 54.7* |

| 6-11 years | 2296 | 73.0 | 2096** | 68.5** | 1771* | 57.9* |

| 12-18 years | 2630 | 72.0 | 2269** | 65.6** | 1842* | 53.3* |

| Sex | ||||||

| Males | 2548 | 73.2 | 2286** | 68.6** | 1866* | 56.0* |

| Females | 2050 | 70.9 | 1794** | 65.6** | 1491* | 54.5* |

| Head of household education | ||||||

| Less Than High School Diploma | 2078 | 69.1 | 1939 | 63.9** | 1591* | 52.4* |

| High School Diploma | 2394 | 74.0 | 2023** | 67.4** | 1662* | 55.4* |

| More Than High School Diploma | 2337 | 72.0 | 2099** | 68.2** | 1729* | 56.2* |

| Household income | ||||||

| <185% Federal Poverty Level | 2218 | 71.0 | 1998** | 66.1** | 1647* | 54.5* |

| 185-350% Federal Poverty Level | 2306 | 73.3 | 2117** | 68.2** | 1735* | 55.9* |

| >350% Federal Poverty Level | 2445 | 72.8 | 2081** | 68.6** | 1713* | 56.5* |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Mexican American | 2049 | 67.4 | 1983 | 65.4 | 1605* | 52.9* |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2423 | 74.3 | 2102** | 70** | 1716* | 57.2* |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2277 | 71.1 | 2061** | 65.5** | 1793* | 57.0* |

Chilean criteria plus NOVA ultraprocessed foods; Note: Data from NHANES 2003-2004, NHANES 2005-2006, NHANES 2013-2014 and NHANES 2015-2016. Results have been weighted to be nationally representative. NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Different from 2013-16 (p<0.05)

Different from 2003-06 (p<0.05)

Note: 100% of participants consumed products considered junk food

Note: Results for Other Hispanic and Other Race not shown

Note: junk food is defined by utilizing the Chilean nutrition profile model phase 2 criteria for nonbasic food groups containing excessive added sugar, salt, saturated fat or energy density in addition to foods classified as ultraprocessed under NOVA

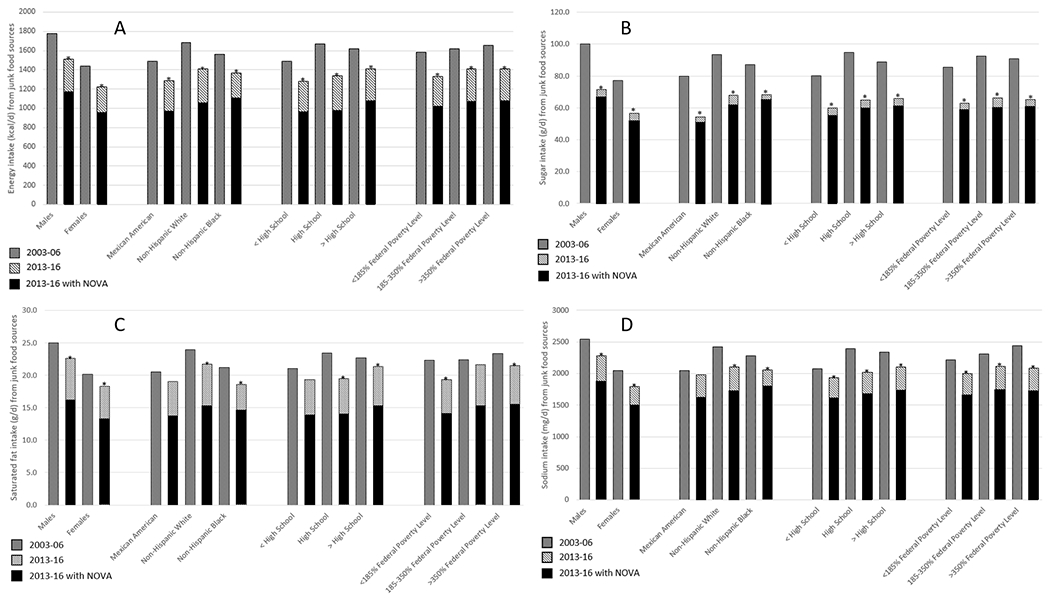

All subgroups showed a significant decrease in mean calorie intake (Figure 1A) and total sugar (Figure 1B) deriving from junk foods between 2003-06 and 2013-16. Almost all subgroups also had a significant decrease in saturated fat (Figure 1C) and sodium (Figure 1D), with some exceptions. For example, Mexican Americans were the only race/ethnic subgroup to not show a significant decrease in saturated fat and sodium intake deriving from junk foods (Figure 1C and 1D). The lowest education group also showed no significant decreases in mean saturated fat or sodium intake deriving from junk foods. Non-Hispanic whites had the highest mean energy, total sugar, saturated fat and sodium intake deriving from junk foods of all race-ethnic groups (Figure 1). The highest income group had the highest absolute intake of energy, saturated fat and sodium.

Figure 1:

Nutrient intake from junk food sources, 2003-2016.

A: Energy intake (kcal/d) from junk food sources

B: Sugar intake (g/d) from junk food sources

C: Saturated fat intake (g/d) from junk food source

D: Sodium intake (mg/d) from junk food sources

Overall intake including the added ingredient criteria

The addition of the added ingredient criteria to the 2013-16 data resulted in a decrease in the amount and proportion of calories, sugar, saturated fat and sodium deriving from junk foods (Table 3). The largest difference was in saturated fat, with a decrease from 20.5g (61.3%) to 14.5g (43.4%). The smallest difference was in sugar, with a decrease from 64.2g (90%) to 58.8g (82.4%). Overall, the proportion of calories deriving from junk food was overestimated by 28% using the Chilean regulation’s nutrient criteria without the added ingredient criteria. Saturated fat was overestimated by 41%, sodium by 22%, and sugar by only 9%. Overestimates were due to differences in a few key food categories (outlined in the following section). When the added ingredient criteria were included in analysis, non-Hispanic black children and adolescents consumed the highest proportion of calories, sugar and saturated fat from junk food, yet non-Hispanic white children and adolescents consumed the highest proportion when the added ingredient criteria were not included (Figure 1).

Food group trends

There was a large decrease in mean calorie intake deriving from SSBs between 2003-16 (185 to 98kcal/d; p<0.01, Supplementary Table 3). Despite less than half of products consumed from the Bread category classified as junk foods in 2013-16, >80% of calories, total sugar, saturated fat and sodium in this category derived from junk foods. Mean calorie intake from Juice products decreased between 2003-16 (57 to 38kcal/d; p<0.01).

100% of calories in Dairy with added sugar, Ready-to-eat cereals and Salty snacks derived from junk foods in both time periods (Table 2), although there was a significant decrease in mean calories deriving from junk foods for Ready-to-eat cereals (70 to 58kcal/d; p<0.01, Supplementary Table 3). Significant increases in mean total sugar intake deriving from junk foods was seen in Sandwiches, burgers and pizzas and Salty snacks (p<0.01 for both, Supplementary Table 4), and a large increase in mean sodium intake deriving from junk foods in Sandwiches, burgers and pizzas (p<0.01, Supplementary Table 5).

Mean calories deriving from junk food sources in Burgers, sandwiches and pizzas increased in some subgroups between 2003-16; Age 2-5y (113 to 151kcal/d; p<0.01), Age 6-11y (220 to 275kcal/d; p<0.01), the lowest education group (214 to 288kcal/d; p<0.01), Mexican Americans (231 to 333kcal/d; p<0.01) and non-Hispanic blacks (215 to 253kcal/d; p<0.01) (Supplementary Table 3).

Key food group findings including the added ingredient criteria

The overall differences in estimates without the inclusion of the added ingredient criteria were driven by a few key categories. For example, calorie intake from Juices decreased from 38kcal/d to lkcal/d with the addition of the ingredient criteria (Supplementary Table 6). Similarly, mean sodium intake from Cheese and cheese products decreased from 104mg/d to 48mg/d and mean calorie intake from 39kcal/d to 11kcal/d. Sandwiches, burgers and pizzas also had a decrease in mean calorie contributions from 260kcal/d to 230kcal/d and mean sodium from 582mg/d to 513mg/d. For categories such as Ready-to-eat cereals and Confectionery results remained the same with and without the added ingredient criteria.

Discussion

This study showed that over a 14-year period, the proportion of foods reported consumed by US children and adolescents that were considered junk foods under the Chilean regulation’s nutrient criteria decreased by about 10 percentage points. Despite this decrease, >70% of total calories and >90% of total sugar intake derived from junk foods in 2013-16. Even with the addition of the added ingredient criteria used to identify junk foods in NHANES 2013-16, 57% of energy, 82% of total sugar, 55% of sodium and 43% of saturated fat consumed by US children and adolescents derived from junk foods. This is in line with previous research showing that the US population has a high intake of foods high in added sugar and solid fats45 and with research in US children from 2003-10 showing that although total calorie intake from junk foods had declined over time, intake was still unacceptably high.46 It is also in line with research from other western countries showing a large proportion of energy intake derives from foods generally considered less healthy.45,47

No subgroup examined had <69% of calories deriving from junk foods in 2013-16, an interesting finding considering studies from various western countries show disparities exist between race-ethnic and education groups in the types of foods consumed, with lower socio-economic groups often having a higher intake of unhealthy foods.34,48,49 One previous study observed that non-Hispanic black and Hispanic households with children purchased less highly processed foods from stores than non-Hispanic whites, although this study found that non-Hispanic blacks purchased a higher amount of sugar.50

It is concerning that such a large proportion of US children and adolescent total sugar intake derives from junk foods. The American Heart Association recommends US children and adolescents consume <10% of daily calories from sugar sources. With our finding that US children in 2013-16 were consuming on average at least 82% (59g or 236kcals) of total sugar per day from junk food sources, it is clear there is scope for improvement.

The Chilean regulation was implemented in 2016. Although limited research exists as to the effectiveness of the regulation (due to its infancy), early research has found that the food marketing regulation can be effective at reducing the use of child-directed marketing for unhealthy products, with one study finding that breakfast cereals using child-directed strategies decreased from 43% before implementation to 15% following implementation.51 In the US, a number of country-wide and state-based policies have been implemented attempting to reduce the purchase of, and hence consumption of, less healthy foods for children and adolescents. For example, some major food and beverage companies previously signed up to the Better Business Bureau’s CFBAI and pledged that they will only market healthier foods to children and adolescents.52 Despite this high-level commitment, research into the scheme has demonstrated that the pledge is often not upheld, with one study reporting that 88% of CFBAI-member company advertisements seen on TV by children promoted products high in saturated fat, sugar, or sodium.53 This, along with findings from this study lend support to exploring the implementation of established schemes restricting the marketing of foods to children, such as Chile’s criteria.

This analysis had some limitations. Reported dietary data has limitations in misreporting and it can vary by age, gender and race-ethnicity.54 Despite each survey being linked to the same FNDDS USDA food composition table there may have been changes in nutrient composition based on different assay techniques which cannot be accounted for. One limitation was that only the nutrient criteria component of the Chilean regulation was used and not the added ingredient component for the trends analysis. Data for ingredients were not available for 2003-06, however were available for 2013-16 data and showed that mean calorie intake from junk foods was overestimated by ~28% when only the nutrient criteria and not the added ingredient criteria were used. Categories like Cheese and cheese products and Juices had a substantial decrease in calories deriving from junk foods with the addition of the added ingredient criteria, however other categories like Confectionery and Ready-to-eat cereals showed no change. What this shows is that by relying solely on nutrient criteria, products such as juices which don’t meet the nutrient criteria due to higher levels of sugar would not be considered junk food under the Chilean regulation as the sugar derives from natural (not added) sugar sources.

Conclusions

Despite noted reductions over 14 years, children and adolescents in the US are still getting a large amount of calories from junk foods, creating a trajectory for long term weight gain and cardio-metabolic problems. Between 56-70% of total calories, 43-61% of saturated fat intake, 82-90% of sugar intake and 55-67% of sodium intake among US children and adolescents derived from junk foods in 2013-16. With reports from the Institute of Medicine55 and Federal Trade Commission56 suggesting that stronger nutrition standards for foods and beverages marketed to children are needed, the implementation of a scheme such as the Chilean criteria is critical to ensure US children are not exposed to products that are high in energy, added sugar, saturated fat and sodium. Future research should examine how other factors influence junk food intake, such as social and family aspects, exposure to unhealthy food marketing, screen time and physical activity levels. This study should be considered as one example to help guide policy regulations regarding the foods and beverages that are accessible in schools and/or marketed to children, adolescents and their caregivers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We also wish to thank Karen Ritter for exceptional assistance with the data management. We got exceptional assistance from Euridice Martinez, the University of Sao Paulo, whose software allowed us to calculate all the Chilean ingredient criteria for 2013-16.

Funding sources: Funding for this work comes primarily from Arnold Ventures with additional support from the Carolina Population Center NIH grant P2C HD050924.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: All authors have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth K. Dunford, Food Policy Division, The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia; Department of Nutrition, Gillings Global School of Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA.

Barry Popkin, Department of Nutrition, Gillings Global School of Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA; Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA.

Shu Wen Ng, Department of Nutrition, Gillings Global School of Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA; Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood Obesity Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/obesity/facts.htm. Accessed July 20, 2019.

- 2.Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9(5):474–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Racial differences in the tracking of childhood BMI to adulthood. Obes Res. 2005;13(5):928–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Lobstein T. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1(1):11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serdula MK, Ivery D, Coates RJ, Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Byers T. Do obese children become obese adults? A review of the literature. Prev Med. 1993;22(2):167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Power C, Lake J, Cole TJ. Review: Measurement and long-term health risks of child and adolescent fatness. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21(7). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvard School of Public Health. Child Obesity: Too Many Kids Are Too Heavy, Too Young. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/obesity-prevention-source/obesity-trends/global-obesity-trends-in-children/. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 8.World Health Organization. Childhood overweight and obesity. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/en/. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 9.Sun SS, Liang R, Huang TTK, et al. Childhood Obesity Predicts Adult Metabolic Syndrome: The Fels Longitudinal Study. J Pediatr. 2008;152(2):191–200.e191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Must A, Strauss RS. Risks and consequences of childhood and adolescent obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35(7):891–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1138–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniels S Complications of obesity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes. 2009;33:S60–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Consideration of the evidence on childhood obesity for the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity: report of the ad hoc working group on science and evidence for ending childhood obesity, Geneva, Switzerland: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/206549. Accessed August 13, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duffey KJ, Gordon-Larsen P, Ayala GX, Popkin BM. Birthplace is associated with more adverse dietary profiles for US-born than for foreign-born Latino adults. J Nutr. 2008;138(12):2428–2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duffey KJ, Popkin BM. Causes of increased energy intake among children in the U.S., 1977-2010. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(2):e1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. https://www.who.int/end-childhood-obesity/publications/echo-report/en/. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 18.Frederick CB, Snellman K, Putnam RD. Increasing socioeconomic disparities in adolescent obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(4):1338–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Committee on Obesity Prevention Policies for Young Children. Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Policies. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13124/early-childhood-obesity-prevention-policies. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 20.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in Obesity Prevalence Among Children and Adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 Through 2013-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2292–2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng SW, Slining MM, Popkin BM. Turning point for US diets? Recessionary effects or behavioral shifts in foods purchased and consumed. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(3):609–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eicher-Miller HA, Fulgoni VL 3rd, Keast DR. Contributions of processed foods to dietary intake in the US from 2003-2008: a report of the Food and Nutrition Science Solutions Joint Task Force of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, American Society for Nutrition, Institute of Food Technologists, and International Food Information Council. J Nutr. 2012;142(11):2065S–2072S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steele EM, Baraldi LG, da Costa Louzada ML, Moubarac J-C, Mozaffarian D, Monteiro CA. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e009892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steele EM, Popkin BM, Swinburn B, Monteiro CA. The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Popul Health Metr. 2017;15(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poti JM, Mendez MA, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Is the degree of food processing and convenience linked with the nutritional quality of foods purchased by US households? Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;99(1):162–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall KD. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: A one-month inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019. 30:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costa Louzada ML, Martins AP, Canella DS, et al. Ultra-processed foods and the nutritional dietary profile in Brazil. Revista de saude publica. 2015;49:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Louzada ML, Baraldi LG, Steele EM, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and obesity in Brazilian adolescents and adults. Prev Med. 2015;81:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canhada SL, Luft VC, Giatti L, et al. Ultra-processed foods, incident overweight and obesity, and longitudinal changes in weight and waist circumference: the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Public Health Nutr. 2019:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rico-Campà A, Martínez-González MA, Alvarez-Alvarez I, et al. Association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and all cause mortality: SUN prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2019;365:l1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Income and race/ethnicity are associated with adherence to food-based dietary guidance among US adults and children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):624–635.e626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hiza HA, Casavale KO, Guenther PM, Davis CA. Diet quality of Americans differs by age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education level. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(2):297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunford EK, Popkin BM. 37 year snacking trends for US children 1977-2014. Ped Obes. 2018;13(4):247–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Batis C, Rivera JA, Popkin BM, Taillie LS. First-Year Evaluation of Mexico’s Tax on Nonessential Energy-Dense Foods: An Observational Study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(7):e1002057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holt E Hungary to introduce broad range of fat taxes. Lancet (London, England). 2011;378(9793):755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Cancer Research Fund International. NOURISHING Database. https://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-database. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 38.Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Moubarac J-C, Levy RB, Louzada MLC, Jaime PC. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2017;21(1):5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Labonte ME, Poon T, Gladanac B, et al. Nutrient Profile Models with Applications in Government-Led Nutrition Policies Aimed at Health Promotion and Noncommunicable Disease Prevention: A Systematic Review. Adv Nutr. 2018;9(6):741–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez Osiac L, Pizarro Quevedo T. [Law of Food Labelling and Advertising: Chile innovating in public nutrition once again]. Revista chilena de pediatria. 2018;89(5):579–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corvalán C, Reyes M, Garmendia ML, Uauy R. Structural responses to the obesity and non-communicable diseases epidemic: Update on the Chilean law of food labelling and advertising. Obes Rev. 2019;20(3):367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Endevelt R, Itamar Grotto, Rivka Sheffer, Rebecca Goldsmith, Maya Golan, Joseph Mendlovic, Moshe Bar-Siman-Tov. Policy and practice - Regulatory measures to improve the built nutrition environment for prevention of obesity and related morbidity in Israel. Public Health Panorama. 2017;3(4):567–575. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perloff BP, Rizek RL, Haytowitz DB, Reid PR. Dietary intake methodology. II. USDA’s Nutrient Data Base for Nationwide Dietary Intake Surveys. J Nutr. 1990;120 Suppl 11:1530–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popkin BM, Haines PS, Siega-riz AM. Dietary patterns and trends in the United States: the UNC-CH approach. Appetite. 1999;32(1):8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(10): 1477–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bleich SN, Wolfson JA. Trends in SSBs and snack consumption among children by age, body weight, and race/ethnicity. Obesity. 2015;23(5):1039–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mercille G, Receveur O, Macaulay AC. Are snacking patterns associated with risk of overweight among Kahnawake schoolchildren? Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(2):163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernandez-Alvira JM, Bornhorst C, Bammann K, et al. Prospective associations between socio-economic status and dietary patterns in European children: the Identification and Prevention of Dietary- and Lifestyle-induced Health Effects in Children and Infants (IDEFICS) Study. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(3):517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gates A, Skinner K, Gates M. The diets of school-aged Aboriginal youths in Canada: a systematic review of the literature. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2015;28(3):246–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poti JM, Mendez MA, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Highly Processed and Ready-to-Eat Packaged Food and Beverage Purchases Differ by Race/Ethnicity among US Households. J Nutr. 2016;146(9):1722–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mediano Stoltze F, Reyes M, Smith TL, Correa T, Corvalan C, Carpentier FRD. Prevalence of Child-Directed Marketing on Breakfast Cereal Packages before and after Chile’s Food Marketing Law: A Pre- and Post-Quantitative Content Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):E4501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Better Business Bureau. Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative. https://www.bbb.org/council/the-national-partner-program/national-advertising-review-services/childrens-food-and-beverage-advertising-initiative/. Accessed December 2, 2019.

- 53.Powell LM, Harris JL, Fox T. Food marketing expenditures aimed at youth: putting the numbers in context. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(4):453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Livingstone MB, Robson PJ, Wallace JM. Issues in dietary intake assessment of children and adolescents. Br J Nutr. 2004;92 Suppl 2:S213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Institute of Medicine. Food marketing to children and youth: Threat or opportunity? http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2005/Food-Marketing-to-Children-and-Youth-Threat-or-Opportunity.aspx. Accessed December 2, 2019.

- 56.Federal Trade Commission. A review of food marketing to children and adolescents. https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/review-food-marketing-children-and-adolescents-follow-report/121221foodmarketingreport.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.