Abstract

Background and Purpose

For survivors of Oral Anticoagulation Therapy (OAT) associated Intracerebral Hemorrhage (OAT-ICH) who are at high risk for thromboembolism, the benefits of OAT resumption must be weighed against increased risk of recurrent hemorrhagic stroke. The ε2/ε4 alleles of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, MRI-defined Cortical Superficial Siderosis (CSS) and Cerebral Microbleeds (CMBs) are the most potent risk factors for recurrent ICH. We sought to determine whether combining MRI markers and APOE genotype could have clinical impact by identifying ICH survivors in whom the risks of OAT resumption are highest.

Methods

Joint analysis of data from two longitudinal cohort studies of OAT-ICH survivors: 1) Massachusetts General Hospital ICH study (MGH-ICH); 2) longitudinal component of the Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study. We evaluated whether MRI markers and APOE genotype predict ICH recurrence. We then developed and validated a combined APOE-MRI classification scheme to predict ICH recurrence, using Classification And Regression Tree (CART) analysis.

Results

CSS, CMB and APOE ε2/ε4 variants were independently associated with ICH recurrence following OAT-ICH (all p<0.05). Combining APOE genotype and MRI data resulted in improved prediction of ICH recurrence (Harrell’s C: 0.79 vs. 0.55 for clinical data alone, p=0.033). In the MGH (training) dataset CSS, CMB and APOE ε2/ε4 stratified likelihood of ICH recurrence into high, medium and low risk categories. In the ERICH (validation) dataset yearly ICH recurrence rates for high, medium and low risk individuals were 6.6%, 2.5% and 0.9% respectively, with overall area under the curve of 0.91 for prediction of recurrent ICH.

Conclusion

Combining MRI and APOE genotype stratifies likelihood of ICH recurrence into high, medium and low risk. If confirmed in prospective studies, this combined APOE-MRI classification scheme may prove useful for selecting individuals for OAT resumption following ICH.

Keywords: Intracerebral Hemorrhage, Anticoagulation Agents, Genetics, MRI

INTRODUCTION

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is one of the most feared complications of long-term Oral Anticoagulation Therapy (OAT), and is more severe and more frequently fatal than spontaneous ICH.1, 2 Survivors of OAT-ICH are at high risk for recurrent hemorrhagic stroke, reflecting the effects of underlying cerebral Small Vessel Disease (SVD).1 Individuals diagnosed with OAT-ICH affecting lobar anatomical regions are at higher risk for recurrent cerebral bleeding,3 presumably because of underlying Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA).4, 5 Conversely, OAT substantially decreases the risk of systemic and cerebral thromboembolism in a variety of high-risk conditions common among ICH survivors.6 Therefore, whether to restart OAT after ICH remains an unsolved clinical dilemma. While it has traditionally been assumed that the risks of OAT resumption after ICH generally outweigh the benefits, recent retrospective studies suggest there are subgroups of ICH survivors for whom OAT resumption would be of benefit.3 Tools to effectively stratify ICH recurrence risk are therefore urgently needed.

MRI-based neuroimaging markers of SVD, including cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) and cortical superficial siderosis (CSS), are potent predictors of spontaneous ICH recurrence in patients not on OAT.7–9 The apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε2/ε4 alleles are risk factors for spontaneous lobar ICH (first-ever and recurrent) and for first-ever OAT-related lobar ICH.10, 11 We therefore sought to determine whether combining MRI and APOE data could generate an effective clinical tool to estimate risk of recurrent hemorrhagic stroke after OAT-ICH, especially lobar OAT-ICH. To achieve this goal, we leveraged existing data from two large studies of ICH: the longitudinal study conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and the multi-center Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study.3, 12, 13 Specifically, we sought to determine whether MRI-based SVD markers and APOE ε2/ε4: 1) are associated with ICH recurrence following OAT-ICH; 2) improved prediction of ICH recurrence; and 3) could be incorporated in a classification tool to predict ICH recurrence.

METHODS

Participating Studies and Analysis Plan

We analyzed data from OAT-ICH survivors from two studies. The ICH study conducted at MGH is a single-center, prospective study.4 Participants are consecutive ICH survivors aged ≥ 18 years, admitted from July 1994 to December 2017 with spontaneous ICH. The ERICH study is a multicenter US study of spontaneous ICH, conducted between August 2010 and September 2016.13 Spontaneous ICH was defined in both studies as non-traumatic, abrupt onset of severe headache, altered level of consciousness, and/or focal neurologic deficit associated with a focal collection of blood within the brain parenchyma on neuroimaging. Patients with hemorrhage resulting from trauma, dural venous sinus thrombosis, conversion of an ischemic infarct, rupture of a vascular malformation or aneurysm, malignancies leading to coagulopathy, or brain tumors were excluded in both studies. Because MGH served as a recruitment site for ERICH, all ERICH participants enrolled at MGH were included only in the ERICH analyses, to avoid data duplication.3, 12 We performed the following joint analyses of the MGH and ERICH datasets: 1) association between MRI markers, APOE ε2/ε4 and recurrent hemorrhagic stroke after OAT-ICH; 2) performance of MRI markers and APOE in predicting ICH recurrence. We then sought to create and validate a combined APOE-MRI novel classification scheme to predict ICH recurrence. We elected to conduct initial analyses in the MGH dataset, due to its larger sample size. We then utilized the ERICH dataset to independently evaluate the predictive performance of the risk classification scheme.

Study Participants

We extracted from participating studies data for individuals fulfilling all these criteria: 1) alive at time of discharge; 2) underwent MRI brain within 90 days of enrollment; 3) available APOE genotype data; 4) on OAT at time of ICH. OAT was defined as either: 1) use of oral vitamin K antagonists and international normalized ratio (INR) > 1.5 at time of symptoms’ onset; or 2) use of non-VKA oral anticoagulants documented in medical records within 24 hours of symptoms’ onset. We excluded subjects who had a history of prior ICH (before the index event), as they are already known to be at very high risk for recurrent hemorrhagic stroke.4 Of note, we included OAT-ICH survivors regardless of whether they were restarted on OAT or not during follow-up.

Participants’ Enrollment and Longitudinal Follow-up

Informed consent for study participation was obtained from all participants or their legally designated surrogates. Institutional review boards reviewed and approved all study protocols. Clinical, demographics, and pre-ICH medication exposure data were collected via in-person interview at time of enrollment, supplemented by review of available medical records.3 Follow-up information was obtained via semi-structured telephone interviews conducted at 3 months, 6 months, 12 months and then at 6-month intervals after the first year. Information on Blood Pressure (BP) measurements during follow-up were obtained according to published methodology.4, 12

Neuroimaging

All CT and MRI scans were reviewed for hematoma location and volume by study staff blinded to outcome and genetic data. All imaging analyses were conducted at the neuroimaging analysis center at MGH, for both the MGH and ERICH studies.3 Lobar ICH was defined as selective hematoma involvement of cerebral cortex, cortical-subcortical junction, or both; all other cases were defined as non-lobar.3, 4 ICH volumes were determined on first-available CT scan, using a previously validated semi-automated method.14 We extracted MRI information on cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) and cortical superficial siderosis (CSS), according to the STRIVE recommendarions15, including: 1) CMBs count for lobar and non-lobar locations; 2) presence and pattern (focal vs. disseminated) of CSS.9

Genotyping

We determined APOE genotype on DNA extracted from blood samples. Two single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs7412 and rs429358) were genotyped separately at MGH (for the MGH study) and at University of Miami (ERICH study).10, 13 The rs7412 and rs429358 genotypes determined APOE ε status (ε2ε2, ε3ε3, ε4ε4, ε3ε2, ε3ε4, ε2ε4). Research staff in charge of genotyping was blinded to neuroimaging and clinical data.

Statistical Methods

Variable definition and handling

Age at index ICH was analyzed as a continuous variable. Patients’ sex was analyzed as a binary variable. APOE genotype was analyzed as a binary variable indicating possession of ≥1 copies of either ε2 or ε4. ICH volumes were analyzed as continuous variables. CMBs were analyzed as continuous variables, and CSS was classified as none, focal (involving ≤3 sulci) or disseminated (>3 sulci).9 Categorical variables were compared using Fisher exact test (2-tailed) and continuous variables using the Mann-Whitney rank-sum or unpaired t test as appropriate.

Univariable and Multivariable Models for ICH Recurrence

The primary outcome was recurrent ICH. Univariable analyses used log-rank tests, while multivariable analyses employed Cox regression. All models were censored for death and recurrent ICH. We constructed models incorporating: 1) clinical covariates available at time of ICH with p < 0.20 in univariable analyses; 2) clinical (as before) and MRI data (CMBs counts, CSS severity), 3) clinical and APOE data; 4) clinical, MRI and APOE data. We evaluated predictive performance via Harrel’s C values, compared using the R package compare function.16 All ICH recurrence models included data from both available datasets.

Classification And Regression Tree (CART) analysis

We used Classification And Regression Tree (CART) analysis to combine and prioritize predictors of ICH recurrence. We did not include follow-up information (blood pressure, medication exposures) among eligible predictors, to develop a classification tool to be implementated at time of ICH. The CART analysis used the R package partykit framework.17 All available variables were initially entered into CART, with minimum final node size of 5 patients. Log-rank p-value threshold of 0.05 defined both stopping and splitting criteria. CART identified ideal cut-off points for continuous variables based on predictive power (Harrell’s C). Once CART selected the optimal tree, we confirmed p<0.05 for each of the splits identified and deleted splits not meeting this criterion. Final nodes not meeting criterion of p<0.05 were combined. We utilized the ERICH (validation) dataset to: 1) estimate and compare ICH recurrence rates across CART nodes; 2) compute sensitivity, specificity, and Area under the Curve (AUC) for ICH recurrence (fitting binary predictions obtained via the predict function in the R package partykit).17 We opted a priori to conduct the following additional CART analyses: 1) among individuals who did not resume OAT (asses for potential indication bias); 2) among survivors of lobar vs. non-lobar OAT-ICH (different risks for ICH recurrence). Because of limited number of OAT-ICH survivors resuming anticoagulation during follow-up, separate analyses in this subgroup were not deemed feasible.

All analyses were performed with R software v 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). p-values < 0.05 (2-tailed) were considered statistically significant, after adjustment for multiple testing using the false discovery rate (FDR) method.18

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

RESULTS

Study participants

In the MGH study 1109 ICH survivors (655 lobar, 454 non-lobar) met initial inclusion criteria. Of these, 169 (110 lobar, 59 non-lobar) were diagnosed with OAT-related ICH. In the ERICH study, 489 ICH survivors (218 lobar, 271 non-lobar) met initial criteria; of these 61 (38 lobar, 23 non-lobar) were OAT-ICH cases (Table 1). Among study participants, indications for OAT were atrial fibrillation (n=177, 77%), mechanical valve (n=14, 6%), venous thromboembolism (n=18, 8%), or other miscellaneous (n=13, 9%). Among 169 survivors of OAT-ICH enrolled in the MGH study, there were 32 ICH recurrences during a median follow-up time of 52.1 months (IQR: 33.4 – 62.7). We observed 16 recurrent ICH events among 61 OAT-ICH survivors enrolled in ERICH and followed for a median of 32.1 months (IQR: 28.3 – 38.2). Average loss to follow-up rate across both studies was 1.6% yearly.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Survivors of OAT-ICH

| Variable | MGH ICH (n = 169) | ERICH (n = 61) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Recurrent ICH | Recurrent ICH | No Recurrent ICH | Recurrent ICH | |

| No. of individuals | 137 | 32 | 45 | 16 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (mean, SD in years) | 71.8 (8.3) | 74.7 (7.0) | 69.8 (10.2) | 70.6 (8.9) |

| Sex (Male) | 75 (56) | 17 (53) | 21 (47) | 8 (50) |

| Race / Ethnicity | ||||

| - White | 105 (77) | 22 (69) | 14 (31) | 4 (25) |

| - Black | 16 (12) | 5 (16) | 16 (36) | 6 (38) |

| - Hispanic | 14 (10) | 4 (13) | 15 (33) | 6 (38) |

| - Other | 2 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Education (mean, SD in years) | 14.0 (3.8) | 13.0 (3.7) | 10.8 (3.5) | 11.1 (3.1) |

| Pre-ICH Medical History | ||||

| Hypertension | 104 (76) | 26 (81) | 39 (87) | 15 (94) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 25 (18) | 6 (19) | 18 (40) | 7 (44) |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 37 (27) | 10 (31) | 15 (33) | 6 (38) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score (median, IQR) | 5 (4 – 6) | 5 (4 – 6) | 5 (4 – 6) | 5 (4 – 6) |

| HAS-BLED score (median, IQR) | 3 (3 – 4) | 3 (3 – 4) | 3 (3 – 4) | 3 (3 – 4) |

| Genetic Data | ||||

| APOE ε2 (≥ 1 copy) | 20 (15) | 9 (28) | 7 (16) | 4 (25) |

| APOE ε4 (≥ 1 copy) | 30 (22) | 12 (38) | 10 (22) | 5 (31) |

| Acute ICH Data | ||||

| ICH Location | ||||

| - Lobar | 84 (61) | 26 (81) | 27 (60) | 11 (69) |

| - Non-Lobar | 53 (39) | 6 (19) | 18 (40) | 5 (31) |

| ICH Volume (median, IQR in cc) | 16.6 (8.8 – 26.6) | 17.6 (5.0 – 27.6) | 15.4 (7.3 – 25.5) | 16.3 (6.3 – 28.2) |

| IVH Presence | 43 (31) | 9 (28) | 15 (33) | 6 (38) |

| MRI Data | ||||

| Lobar CMB count (median, IQR) | 0 (0 – 1) | 1 (1 – 2) | 0 (0 – 1) | 1 (1 – 2) |

| Non-Lobar CMB count (median, IQR) | 0 (0 – 1) | 0 (0 – 1) | 0 (0 – 1) | 0 (0 – 1) |

| Cortical Superficial Siderosis | ||||

| - None | 130 (95) | 23 (72) | 42 (93) | 12 (75) |

| - Focal | 4 (3) | 3 (9) | 2 (4) | 1 (6) |

| - Disseminated | 3 (2) | 6 (19) | 1 (2) | 3 (19) |

| Medication Exposure During Follow-up | ||||

| OAT | 38 (28) | 8 (25) | 8 (17) | 2 (13) |

| - Vitamin K Antagonists | 36 (26) | 7 (22) | 7 (16) | 2 (13) |

| - Direct Oral Anticoagulants | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Antiplatelets | 68 (50) | 15 (47) | 17 (38) | 6 (38) |

All values presented as number (percentages), unless otherwise specified

Abbreviations: CMB = Cerebral Microbleeds, ICH = Intracerebral Hemorrhage, IQR = interquartile range, OAT = Oral Anticoagulation Therapy, SD = standard deviation

Association between MRI-based SVD markers, APOE genotype and ICH recurrence

We performed time-to-event analyses to determine predictors of recurrent ICH following OAT-ICH. In joint analysis of both datasets (Supplementary Table I), we identified associations between CMBs, CSS and APOE ε2/ε4 and ICH recurrence in univariable analyses (all p<0.05). Both imaging and genetic markers were independently associated with ICH recurrence after adjustment for covariates of interest (Table 2). We present results of multivariable analyses restricted to lobar and non-lobar OAT-ICH in Supplementary Tables II and III.

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis of ICH Recurrence Risk Among OAT-ICH Survivors

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.04 | 0.99 – 1.09 | 0.091 |

| Education (> 12 years) | 0.90 | 0.80 – 1.01 | 0.069 |

| Lobar CMBs (per each additional CMB) | 1.88 | 1.13 – 3.12 | 0.015 |

| Increasing CSS Severity (None - Focal - Disseminated) | 1.51 | 1.07 – 2.13 | 0.021 |

| APOE ε2 or ε4 (≥ 1 copy) | 1.90 | 1.10 – 3.29 | 0.023 |

Results derived from combined analysis of MGH-ICH and ERICH data (n = 230)

Abbreviations: APOE = Apolipoprotein E, CSS = Cortical Superficial Siderosis, CMB = Cerebral Microbleeds, ICH = Intracerebral Hemorrhage, OAT = Oral Anticoagulation Therapy

MRI-based SVD markers, APOE and ICH Recurrence Prediction

We then determined whether MRI-based SVD markers and APOE genotype enhance prediction of ICH recurrence risk after OAT-ICH. Clinical data alone, without genetics or imaging, had moderate predictive power for ICH recurrence risk (Table 3). Incorporation of MRI or APOE data individually resulted in markedly improved predictive performance. Joint incorporation of MRI and APOE (Table 3) further improved ICH recurrence risk prediction.

Table 3.

Performance of Prediction Models for Risk of Recurrent ICH Following OAT-ICH

| Model | Variables Included | C-statistic (95% CI) | Statistical Comparison (p-value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. Model 1 | vs. Model 2 | vs. Model 3 | |||

| Model 1: - Clinical |

• Clinical Data* | 0.51 (0.48 – 0.54) | - | - | - |

| Model 2: - Clinical - MRI |

• Clinical Data* • CSS: Disseminated • Lobar CMB |

0.70 (0.66 – 0.74) | 0.011 | - | - |

| Model 3: - Clinical - APOE |

• Clinical Data* • APOE ε2 or ε4 (≥ 1 copy) |

0.65 (0.61 – 0.70) | 0.009 | 0.21 | - |

| Model 4: - Clinical - MRI - APOE |

• Clinical Data* • CCS: Disseminated • Lobar CMB • APOE ε2 or ε4 (≥ 1 copy) |

0.79 (0.73 – 0.84) | 0.002 | 0.012 | 0.033 |

Clinical data includes age and educational level.

Results derived from combined analysis of MGH-ICH and ERICH data (n = 230)

Abbreviations: 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval, APOE = Apolipoprotein E, CSS = Cortical Superficial Siderosis, CMB = Cerebral Microbleeds, ICH = Intracerebral Hemorrhage, OAT = Oral Anticoagulation Therapy

Development and Validation of an APOE-MRI Risk Prediction System

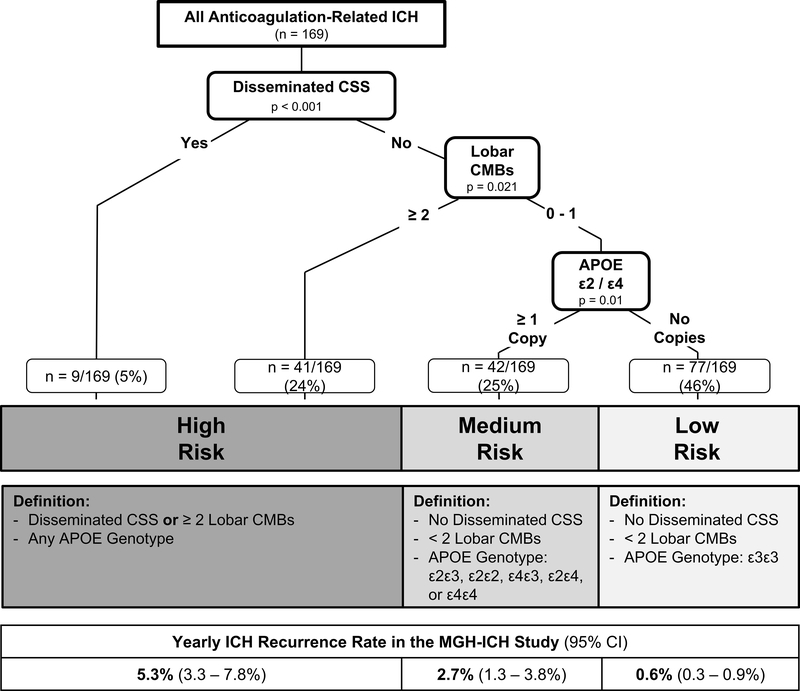

CART analysis in the MGH dataset demonstrated that integrated use of MRI and APOE genotype stratified participants into three significantly different categories of risk for recurrent ICH (Figure 1). Disseminated CSS was the most potent individual predictor for recurrent ICH, followed by CMB count (with a cut-off of ≥ 2 lobar CMBs selected by the algorithm as most informative). Due to limited sample size in individual risk categories, we combined presence of disseminated CSS or ≥ 2 lobar CMBs into the high-risk category for ICH recurrence. Among individuals lacking these high-risk neuroimaging findings (n = 119, 70% of our cohort), the presence of an APOE ε2 or ε4 allele distinguished between those at medium vs. low risk of recurrent ICH.

Figure 1. ICH Recurrence Risk following OAT-related ICH, based on MRI data and APOE Genotype.

Abbreviations: APOE = Apolipoprotein E, CSS = Cortical Superficial Siderosis, CMB = Cerebral Microbleeds, ICH = Intracerebral Hemorrhage, OAT = Oral Anticoagulation Therapy

Validation of the combined APOE-MRI risk classification scheme in the ERICH dataset confirmed significant differences in ICH recurrence rate when comparing the high, medium and low risk groups (p<0.001 for trend comparison across categories, and p < 0.05 for all pair-wide comparison between risk categories) (Table 4). Overall, the APOE-MRI classification scheme demonstrated excellent predictive performance with sensitivity of 0.90, specificity of 0.91, and with overall Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.91.

Table 4.

Yearly ICH Recurrence Rates and Predictive Performance of the APOE-MRI Risk Classification Scheme in the ERICH Validation Dataset.

| Study Participants | No. of ICH Survivors | Yearly ICH Recurrence Rate (95% CI) | p | Predictive Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Risk | Medium Risk | Low Risk | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | |||

| All ICH Survivors | ||||||||

| - all participants | 61 | 6.6 (5.2 – 9.9) | 2.5 (1.8 – 2.8) | 0.9 (0.4 – 1.5) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.54 – 0.99) | 0.91 (0.76 – 0.98) | 0.91 (0.86 – 0.94) |

| - no OAT exposure | 51 | 6.9 (5.4 – 10.4) | 2.3 (1.7 – 2.7) | 1.0 (0.6 – 1.3) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.58 – 0.99) | 0.93 (0.79 – 0.99) | 0.90 (0.84 – 0.93) |

| Lobar ICH Survivors | 38 | 8.8 (5.5 – 10.2) | 3.3 (2.6 – 4.1) | 1.1 (0.7 – 1.8) | <0.001 | 0.70 (0.35 – 0.92) | 0.94 (0.68 – 0.99) | 0.82 (0.76 – 0.90) |

| Non-lobar ICH Survivors | 23 | 4.3 (3.2 – 6.9) | 1.8 (1.0 – 2.9) | 0.5 (0.2 – 1.0) | 0.039 | 0.91 (0.72 – 0.98) | 0.74 (0.42 – 0.95) | 0.80 (0.74 – 0.84) |

Sensitivity analyses

We first applied the APOE-MRI risk classification scheme analysis to individuals not receiving OAT during follow-up (n = 51, see Table 4). Classification into high, medium and low risk categories retained ability to discriminate significant differences in ICH recurrence rates (p<0.001 for trend comparison across categories, and p < 0.05 for all pair-wide comparison between risk categories). We then applied the APOE-MRI risk classification scheme in the ERICH validation dataset in the lobar ICH (n = 38) and non-lobar ICH (n = 23) sub-groups. In both subset analyses (Table 4) classification into high, medium and low risk categories retained ability to discriminate significant differences in ICH recurrence rates (p<0.05 for trend comparison across categories, and p < 0.05 for all pair-wide comparison between risk categories).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate that, among survivors of OAT-ICH, MRI markers of cerebral small vessel disease and APOE variants ε2/ε4 are potent risk factors for recurrent cerebral bleeding. Combining MRI and APOE with established clinical markers for risk of ICH recurrence yielded significant improvement in predictive capacity for repeat ICH. We therefore developed and validated an APOE-MRI risk stratification scheme that successfully distinguished patients at high and low risk for recurrent ICH. Individuals in the high-risk group had up to 10 times the annual risk of recurrent ICH compared to those OAT-ICH survivors whom MRI and APOE identified as low risk.

Our results are concordant with prior studies showing robust associations between CSS, CMBs, APOE and risk of non-OAT related ICH7, 19–21 as well as first-ever lobar OAT-ICH.11 Building on this published evidence, our findings indicate that CAA (the SVD subtyped linked to APOE, CMBs and CSS) plays a critical role in recurrent cerebral bleeding risk after OAT-related ICH. Lobar hematoma location was not selected for inclusion as a key predictor of ICH recurrence by an unbiased algorithm, implying inferior predictive capability than the combination of APOE and MRI data. Taken together with prior evidence indicating that blood pressure control is associated with recurrence risk of both lobar and non-lobar ICH, these findings reflect the mixed hypertensive/amyloid nature of at least a subset of lobar ICH events.4 Our results suggest that the complex underlying pathophysiology of many OAT-ICH cases is better characterized by combining genetic and MRI neuroimaging data.

APOE adds substantially to risk stratification in OAT-ICH survivors, raising the possibility that it may be of clinical utility in this setting. MRI identified fewer than one third of participants in our analyses as high risk for recurrent cerebral bleeding; most OAT-ICH survivors were deemed low risk, as they lacked evidence of disseminated CSS or a high CMB count. However, inclusion of APOE in a combined stratification tool separated this majority of participants into two groups with widely different risks for recurrent hemorrhagic stroke. Individuals with no disseminated CSS, low lobar CMBs count (0 to 1) and APOE ε3ε3 genotype accounted for almost half of all OAT-ICH survivors, and were at very low risk for recurrent ICH.

Our study displays several strengths, including: 1) highly curated individual-level data (including genetic and MRI information); 2) standardized, validated methodology for longitudinal follow-up; 3) independent validation in the racially-balanced ERICH study. There are also several limitations to our approach. Despite having analyzed data from two separate, large ICH studies, our analyses are retrospective in nature and limited in sample size. Study inclusion criteria (especially availability of MRI/APOE data) may have also resulted in patient selection bias. Finally, due to the nature of the data being analyzed, we are unable to determine whether MRI-APOE-based decision making in regard to OAT resumption could directly improve patient outcomes. Our combined APOE-MRI risk classification scheme may aid in identifying high risk individuals (for whom future studies of OAT resumption would warrant careful consideration) vs. low risk individuals (who may be considered for resumption of OAT in the setting of future randomized control studies). Of note, our sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the classification scheme retained excellent predictive performance regardless of exposure to OAT. Ultimately, only a dedicated randomized controlled trial comparing the performance of APOE-MRI risk determination with current standard practices could fully address these limitations.

Summary/Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrate that while MRI data and APOE both predict recurrent ICH in survivors of OAT-ICH, combining them creates a risk stratification tool that better discriminates patients at high and low risk for recurrent ICH. While this combined MRI-APOE prediction scheme of ICH requires further validation in large, prospective studies, it raises the possibility that bedside genetic testing for OAT-ICH survivors could become part of routine clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Study design: SU, AB, JR; Data acquisition: All Authors; Statistical analysis: SU, AB; Study Supervision / Coordination: AB, CK, K.Schwab, ZDP, FDT, CDA, DW, K.Sheth, JR; Manuscript preparation: SU, AB, PK, JR; Manuscript review: All Authors. All statistical analyses performed by: Alessandro Biffi, MD (Massachusetts General Hospital). Drs. Urday, Biffi and Rosand had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

FUNDING

The authors’ work on this study was supported by funding from the US National Institute of Health (K23NS100816, U01NS069763, R01NS093870, and R01AG26484). The funding entities had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding: National Institutes of Health

COMPETING INTERESTS

Dr. Alessandro Biffi is supported by K23NS100816.

Dr. Sebastian Urday reports no disclosures.

Mr. Patryk Kubiszewski reports no disclosures.

Ms. Lee Gilkerson reports no disclosures.

Ms. Padmini Sekar reports no disclosures.

Ms. Axana Rodriguez-Torres reports no disclosures.

Dr. Margaret Bettin reports no disclosures.

Dr. Andreas Charidimou reports no disclosures.

Dr. Marco Pasi reports no disclosures.

Ms. Christina Kourkoulis reports no disclosures.

Ms. Zora DiPucchio reports no disclosures.

Mr. Tyler Behymer reports no disclosures.

Ms. Jennifer Osborne reports no disclosures.

Ms. Misty Morgan reports no disclosures.

Ms. Kristin Schwab reports no disclosures.

Dr. Michael L. James reports no disclosures.

Dr. Steven M Greenberg is supported by R01AG26484

Dr. Anand Viswanathan is supported by R01AG047975, R01AG026484, P50AG005134, K23AG02872605

Dr. M Edip Gurol is supported by K23NS083711, and research grants from AVID (Eli Lilly), Pfizer, and Boston Scientific.

Dr. Bradford B Worrall is supported by KL2TR003016, R21NS106480, U24NS107222, the Australian-American Fulbright Commission and University of Newcastle, and serves as Deputy Editor for Neurology.

Dr. Fernando Testai reports no disclosures.

Dr. Jacob L. McCauley reports no disclosures.

Dr Falcone reports grants from National Institutes of Health, American Heart Association, and Neurocritical Care Society outside the submitted work.

Dr. Carl D. Langefeld reports no disclosures.

Dr. Christopher D. Anderson is supported by R01NS103924, AHA18SFRN34250007, and Massachusetts General Hospital, received research support from Bayer AG, and consulting fees from ApoPharma, Inc.

Dr Hooman Kamel reports serving as co-PI for the NIH-funded ARCADIA trial which receives in-kind study drug from the BMS-Pfizer Alliance and in-kind study assays from Roche Diagnostics, serving as Deputy Editor for JAMA Neurology, serving as a steering committee member of Medtronic’s Stroke AF trial (uncompensated), serving on an endpoint adjudication committee for a trial of empagliflozin for Boehringer-Ingelheim, and having served on an advisory board for Roivant Sciences related to Factor XI inhibition.

Dr. Daniel Woo reports no disclosures related to this manuscript.

Dr Kevin N. Sheth is supported by U24NS107215, U24NS107136, U01NS106513, R01NR018335, AHA17CSA33550004, received research funding from Hyperfine, Bard, Novartis, and Biogen, received consulting fees from Zoll Medical Corporation, and holds equity in Alva Health and Astrocyte Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Dr. Jonathan Rosand is supported by R01NS036695, UM1HG008895, R01NS093870, R24NS092983, and has consulted for New Beta Innovations, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.An SJ, Kim TJ, Yoon BW. Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features of intracerebral hemorrhage: An update. Journal of stroke. 2017;19:3–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witt DM, Delate T, Hylek EM, Clark NP, Crowther MA, Dentali F, et al. Effect of warfarin on intracranial hemorrhage incidence and fatal outcomes. Thrombosis research. 2013;132:770–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biffi A, Kuramatsu JB, Leasure A, Kamel H, Kourkoulis C, Schwab K, et al. Oral anticoagulation and functional outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Annals of neurology. 2017;82:755–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biffi A, Anderson CD, Battey TW, Ayres AM, Greenberg SM, Viswanathan A, et al. Association between blood pressure control and risk of recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage. JAMA. 2015;314:904–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charidimou A, Shoamanesh A, Al-Shahi Salman R, Cordonnier C, Perry LA, Sheth KN, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebral microbleeds and implications for anticoagulation decisions: The need for a balanced approach. International journal of stroke : official journal of the International Stroke Society. 2018;13:117–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy SB, Gupta A, Merkler AE, Navi BB, Mandava P, Iadecola C, et al. Restarting anticoagulant therapy after intracranial hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2017;48:1594–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charidimou A, Martinez-Ramirez S, Shoamanesh A, Oliveira-Filho J, Frosch M, Vashkevich A, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy with and without hemorrhage: Evidence for different disease phenotypes. Neurology. 2015;84:1206–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rensma SP, van Sloten TT, Launer LJ, Stehouwer CDA. Cerebral small vessel disease and risk of incident stroke, dementia and depression, and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2018;90:164–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charidimou A, Martinez-Ramirez S, Reijmer YD, Oliveira-Filho J, Lauer A, Roongpiboonsopit D, et al. Total magnetic resonance imaging burden of small vessel disease in cerebral amyloid angiopathy: An imaging-pathologic study of concept validation. JAMA neurology. 2016;73:994–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biffi A, Sonni A, Anderson CD, Kissela B, Jagiella JM, Schmidt H, et al. Variants at apoe influence risk of deep and lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. Annals of neurology. 2010;68:934–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falcone GJ, Radmanesh F, Brouwers HB, Battey TW, Devan WJ, Valant V, et al. Apoe epsilon variants increase risk of warfarin-related intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2014;83:1139–1146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez-Torres A, Murphy M, Kourkoulis C, Schwab K, Ayres AM, Moomaw CJ, et al. Hypertension and intracerebral hemorrhage recurrence among white, black, and hispanic individuals. Neurology. 2018;91:e37–e44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woo D, Rosand J, Kidwell C, McCauley JL, Osborne J, Brown MW, et al. The ethnic/racial variations of intracerebral hemorrhage (erich) study protocol. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44:e120–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biffi A, Battey TW, Ayres AM, Cortellini L, Schwab K, Gilson AJ, et al. Warfarin-related intraventricular hemorrhage: Imaging and outcome. Neurology. 2011;77:1840–1846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, Cordonnier C, Fazekas F, Frayne R, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet neurology. 2013;12:822–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang L, Chen W, Petrick NA, Gallas BD. Comparing two correlated c indices with right-censored survival outcome: A one-shot nonparametric approach. Statistics in medicine. 2015;34:685–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanadini LG, Steeves JD, Hothorn T, Abel R, Maier D, Schubert M, et al. Identifying homogeneous subgroups in neurological disorders: Unbiased recursive partitioning in cervical complete spinal cord injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014;28:507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsueh HM, Chen JJ, Kodell RL. Comparison of methods for estimating the number of true null hypotheses in multiplicity testing. J Biopharm Stat. 2003;13:675–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Etten ES, Auriel E, Haley KE, Ayres AM, Vashkevich A, Schwab KM, et al. Incidence of symptomatic hemorrhage in patients with lobar microbleeds. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2014;45:2280–2285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez-Ramirez S, Romero JR, Shoamanesh A, McKee AC, Van Etten E, Pontes-Neto O, et al. Diagnostic value of lobar microbleeds in individuals without intracerebral hemorrhage. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2015;11:1480–1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linn J, Halpin A, Demaerel P, Ruhland J, Giese AD, Dichgans M, et al. Prevalence of superficial siderosis in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2010;74:1346–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.