Summary

Worldwide, millions of children live in institutions, which runs counter to both the UN-recognised right of children to be raised in a family environment, and the findings of our accompanying systematic review of the physical, neurobiological, psychological, and mental health costs of institutionalisation and the benefits of deinstitutionalisation of child welfare systems. In this part of the Commission, international experts in reforming care for children identified evidence-based policy recommendations to promote family-based alternatives to institutionalisation. Family-based care refers to caregiving by extended family or foster, kafalah (the practice of guardianship of orphaned children in Islam), or adoptive family, preferably in close physical proximity to the biological family to facilitate the continued contact of children with important individuals in their life when this is in their best interest. 14 key recommendations are addressed to multinational agencies, national governments, local authorities, and institutions. These recommendations prioritise the role of families in the lives of children to prevent child separation and to strengthen families, to protect children without parental care by providing high-quality family-based alternatives, and to strengthen systems for the protection and care of separated children. Momentum for a shift from institutional to family-based care is growing internationally—our recommendations provide a template for further action and criteria against which progress can be assessed.

Introduction

Between 5 million and 6 million children (aged 0–18 years) worldwide are estimated to live in institutions rather than in family-based care settings, although this estimate is based on scarce data and might be an underestimate.1 A December 2019 UN General Assembly Resolution on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Children recognises that a child should grow up in a family environment to have a full and harmonious development of her or his personality and potential; urges member states to take actions to progressively replace institutionalisation with quality alternative care and redirect resources to family and community-based services; and calls for “every effort, where the immediate family is unable to care for a child with disabilities, to provide quality alternative care within the wider family, and, failing that, within the community in a family setting, bearing in mind the best interests of the child and taking into account the child's views and preferences”.2

Key messages.

-

•

Global actors should work jointly to support the progressive elimination of institutions and promote family-based care

-

•

National child protection systems should be grounded in a continuum of care that prioritises the role of families

-

•

Local programmes should address the drivers of institutionalisation and address the specific needs of each child and family

-

•

Donors and volunteers should redirect their funding and efforts to community-based and family-based programmes

-

•

Community-based and family-based programmes are fiscally efficient and promote long-term human capital development

-

•

More efforts to improve data, information, and evidence to inform policies and programmes are urgently needed

More than 250 non-governmental organisations and UNICEF have endorsed detailed recommendations for this resolution (panel 1 ).3 These recommendations include the need to prioritise the role of families in the lives of children, to prevent child separation and strengthen families, to protect children who do not have parental care by providing high-quality family-based alternatives within the community, to recognise the harm of institutionalisation, and to strengthen systems for the care and protection of children. Concerted global efforts to reform systems for the care of children by keeping families together by strengthening families and building up family support services in communities, putting in place alternative family-based care, and progressively replacing institutional care with quality alternatives in a safe and structured manner are under way and should be promoted.

Panel 1. Excerpts from the non-governmental organisation key recommendations for the December 2019 UN General Assembly Resolution on the rights of the child3.

Recognise and prioritise the role of families

-

•

States are responsible for promoting parental care, preventing unnecessary child separation, and facilitating reintegration where appropriate

-

•

Families have a crucial role in physical, social, and emotional development, health, and intergenerational poverty reduction

-

•

Services delivered to children are most effective when they consider the vital role of family

Protect children without parental care and ensure high-quality, appropriate alternative care

-

•

Comprehensive systems for the welfare and protection of children should be supported to address the complex needs of children at risk of, or in, alternative care

-

•

Formal alternative care should be temporary

-

•

Care options should prioritise kinship care, foster care, adoption, kafalah, and cross-border reunification

-

•

Registration, licensing, and oversight should be in place for all formal care options

Strengthen systems for the welfare and protection of children

-

•

States should strengthen community-based, national, and cross-border systems for child protection that assess and meet the needs of vulnerable children

-

•

Policies should be implemented to protect children from abuse while in the care of an adult

Improve data collection and regular reporting

-

•

States should recognise that the sustainable development goals will not be achieved if children without parental care are neglected, and that not all children are being counted

-

•

Rigorous data collection by national authorities is important, and should be duly supported by international cooperation

-

•

Data should be collected longitudinally, with gaps addressed, and evidence building supported

Support families and prevent unnecessary family–child separation

-

•

States are called upon to strengthen family-centred policies such as parental leave, childcare, and parenting support

-

•

States should address drivers of separation, protect children, and provide high-quality social services

-

•

States are encouraged to work to change norms, beliefs, and attitudes that drive separation

-

•

States should recognise that reintegration is a process requiring preparation, support, and follow-up

Recognise the harm of institutional care for children and prevent institutionalisation

-

•

The harm that institutions do to the growth and development of children and the increased risks of violence and exploitation should be recognised

-

•

States should phase out institutions and replace them with family and community-based services

-

•

States should address how volunteering and donations can lead to unnecessary family–child separation

-

•

States should enact and enforce policies to prevent trafficking of children into institutions

Ensure adequate human and financial resources

-

•

States should recognise that funding for institutions can exacerbate unnecessary family–child separation and institutionalisation

-

•

States should allocate human and financial resources for child and family welfare services

-

•

States should provide resources for a trained social-service workforce

Ensure full participation of children without parental or family care

-

•

States should reaffirm the rights of all children to free expression and to have their views taken into account

-

•

States should strengthen mechanisms for participation of children in planning and implementing policies and services

-

•

States should establish a competent monitoring mechanism such as an ombudsperson

In part 1 of this Commission, published in The Lancet Psychiatry, our accompanying systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies of the developmental and mental health costs of institutional deprivation, and the benefits of family strengthening and progressive elimination of institutionalisation,4 supports this view. The systematic review highlights the associations between institutional care as typically practised and delays in physical growth, brain development, cognition, and attentional competence. Weaker associations were found between institutional care and adverse effects on physical health and socioemotional development. Overall, we found that the longer children spent in an institution, the worse their outcomes were. While in institutions, children are usually isolated from kinship networks that have a crucial role in their societies, and typically do not participate in social, cultural, religious, and economic activities in their communities. Furthermore, removal from institutions and placement in family-based care is associated with substantial, if incomplete, recovery in key developmental domains: generally, the shorter the duration of institutional placement and the earlier in life such placements occur, the better the outcomes. Based on these findings, the conclusion of part 1 of this Commission is that there is an urgent need to implement policies and practices to promote family strengthening and family care, and to progressively eliminate the institutionalisation of children.4

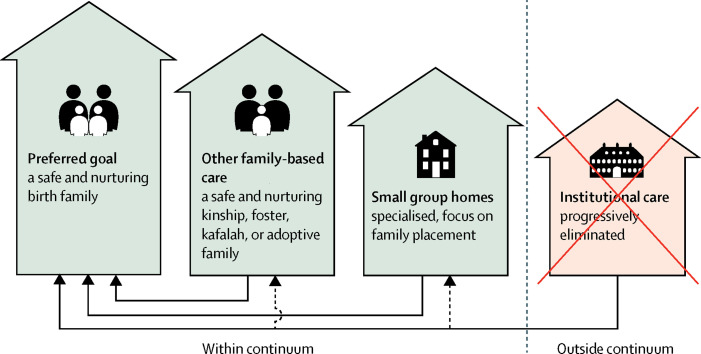

We define an institution as a publicly or privately managed and staffed collective living arrangement for children that is not family based, such as an orphanage, children's institution, or infant home. The recommendations that were endorsed for the UN General Assembly Resolution recognise that “in specific cases it may be necessary to provide quality, temporary, specialized care in a small group setting”,3 for the shortest period and with the objective of child reintegration or, if this reintegration is not possible or in the child's best interests, a safe, nurturing, and stable alternative family setting or supported independent living should be provided. Such residential care can have a role in a system for child welfare. This care might be necessary in very few situations, such as those regarding the immediate safety of the child, unaccompanied children, or children with some highly specialised physical or psychiatric needs. The use of the word institution in this Commission (and the objective of the progressive elimination of institutions) therefore does not include the temporary and specialised residential care outlined in the recommendations3 endorsed for the UN General Assembly Resolution. We emphasise that a poor-quality small group setting that does not meet the standards set in those recommendations can be harmful to the wellbeing and protection of children.

We also observe that policy makers should develop a more comprehensive continuum of care that is family centred and grounded in the best interests of the child. The continuum should include programmes and services that prevent children from being separated from families, promote effective reintegration programmes for children who are separated from families, and focus available resources on quality alternative care options, including kinship care, foster care, adoption, and kafalah.

This Commission presents a comprehensive set of recommendations that address drivers of institutionalisation and that promote family-based care at the global, national, and local levels in three sections. Each section describes policy goals and approaches to implementation for a specific set of elements (actors, processes, or stages) that we believe to be central to delivering on the overall policy of promoting systems of care that are focused on the family. Section 1 focuses on the role of global actors that are key to driving the process of promoting family care and quality family-based alternative care, and progressively eliminating the role of institutions in care systems. These global actors include multilateral organisations, international non-governmental organisations, global funders, faith-based organisations, and volunteer organisations. Section 2 focuses on ways to implement change at the national systems level. Policy recommendations for national-level actors relate to issues such as building momentum for change, mobilising a shared vision, supporting and resourcing quality implementation, and monitoring and evaluating reform. Section 3 focuses on policy and practice at the local (ie, community and family) level to promote changes that place importance on strengthening families and family-based care for children, safely and substantially reducing the use of institutional care, and improving the processes of transition from institutional to high-quality family-based care (including families of origin and alternative care). The global, national, and local sections have a common structure: first, context is given and the most pertinent background considerations are presented; second, the specific policy goals are presented and strategies for change are recommended; third, implementation approaches are outlined; and finally, approaches to monitoring and evaluation of indicators relevant to children and families, policies, programmes, and services are discussed.

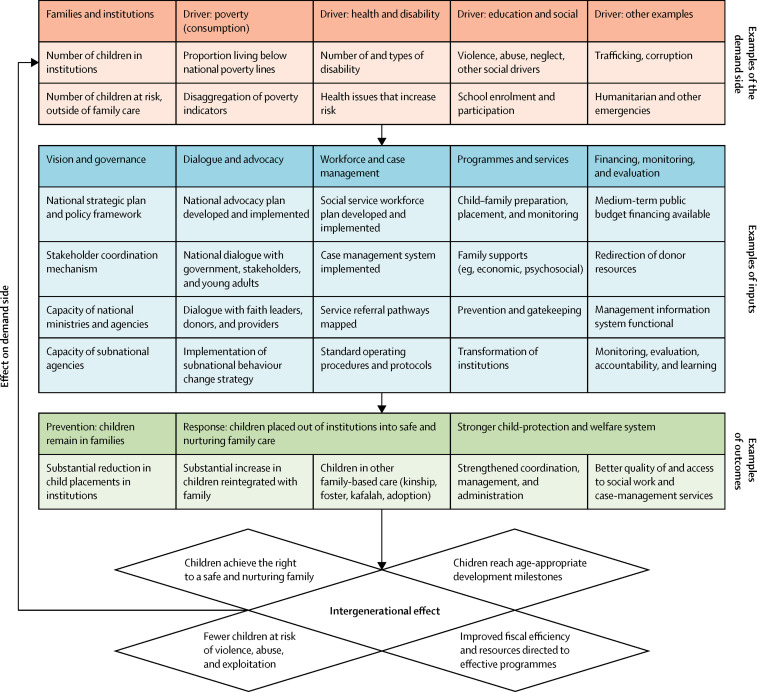

Although the recommendations we make in this Commission are, of necessity, presented at a somewhat generalised level, we include a further reading panel of examples and approaches, with additional suggested resources in the appendix. A model of change that illustrates the linkages between the demand for services, the inputs and outputs from programming that strengthens care for children, and the effect on the welfare of children is presented in figure 1 .

Figure 1.

A model for improving children's care outcomes

A systemic cross-sectoral approach will yield benefits across generations.

Section 1: The role of global actors

International organisations influence national policies, norms, and behaviours to varying degrees across a wide range of matters such as health, climate, education, and social welfare.5, 6, 7, 8 Some global actors have worked to promote family care for children, whereas others have had a major role in developing and supporting institutional care around the world.4 This section provides recommendations for global actors, such as multilateral organisations, international non-governmental organisations, global funders, faith-based organisations, and volunteer organisations, to promote policies, resources, and programmes that are supportive of family-based care for children, and to transform care systems to enable a substantial, well planned, and safe progressive elimination of the role of institutions in children's care systems.

Global context

Families carry out crucial socialising, protective, economic, mediating, and nurturing functions for children.9 These functions are essential elements for improving developmental outcomes, which are in turn supportive of long-term human and social capital development. For example, stable family and social environments are known to influence the ability of children to attend and perform well in school, and to affect the health status of a child.10, 11 International organisations have begun to promote the inclusion of early childhood development programmes in national poverty reduction and social development strategies, and these programmes are promotive of family strengthening. However, by definition, early childhood development programmes do not directly address the needs of older children and adolescents, and in some cases do not target the specific risk factors for child separation from the family and institutional placement, such as disability, physical and sexual abuse, migration, natural disasters, and trafficking. Other than programmes for early childhood development, policies to strengthen systems for child welfare and protection tend to be at the margins of the development dialogue in many countries, despite the potential for these systems to contribute to human capital.

We first consider three types of multilateral organisation that could have a greater role in promoting a fuller continuum of care and the transformation of care systems for children: UN agencies with the mandate to support the rights of children, such as UNICEF, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights; international development agencies, such as the World Bank; and regional organisations and development banks.

Multilateral organisations have a long history of supporting the importance of family life for children (including, to the extent possible, with parents or, if necessary, with extended family or other appropriate alternative care) as articulated in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child,12 the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities,13 and the Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children.14 UNICEF has promoted child protection and reduced reliance on institutions since the early 2000s,15 but its global 2018 budget for justice for children (which includes alternative care programming) of around US$100 million is a small fraction of the total overseas development assistance in the same year of more than $150 billion.16, 17 While some regional organisations, such as the EU (panel 2 ), Organization of American States, and Association of Southeast Asian Nations, have issued policies or strategies supporting family-based care for children, the engagement of these organisations in the care and protection of children is limited, although it is growing.24, 25, 26

Panel 2. Promoting care reform in the EU.

Hundreds of thousands of children are living in institutions across the EU. Over the past decade, many countries in the EU have rapidly expanded efforts to promote family-based care for children and have reduced their reliance on institutions. A group of global and regional experts produced the 2012 Common European Guidelines on the Transition from Institutional to Community-based Care18 to establish a strategy and framework for regional reform. Following the production of these guidelines, EU regulations on investment funds included provisions promoting the transition from institutional to community-based care.19 The European Commission began to invest actively in deinstitutionalising systems of care in countries such as Bulgaria, where EU funds supported family and alternative care placements.20 Subsequently, the 2016 EU Guidelines for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of the Child21 promoted alternative care for children and the related right to participate in community life.

At the time of writing, the European Commission has proposed a regulation for the Neighbourhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument for 2021–27 that would include strengthening of systems for child protection and prohibiting investments by European Structural and Investment Funds in institutions, regardless of size.22 Some EU members have developed policies, strategies, and action plans for reforming care and reducing the role of institutions, including Croatia, Greece, Latvia, Romania, Poland, and Serbia.23 Europe's progress has resulted from a combination of European Commission reviews of the evidence on child institutionalisation, an increased global focus on the issue of children outside of family care, and strong civil society advocacy, including by key stakeholders such as organisations that promote the rights of individuals with disabilities. The European Commission should continue its efforts to align its care reform policies internally among members, regionally with pre-accession and neighbouring countries, and in its global external assistance.

We next consider three other types of international agencies that also have a key role in transforming care systems for children globally: bilateral agencies, such as government aid agencies; private funders, such as philanthropists; and international non-governmental organisations. To varying degrees, these agencies have been taking a progressively more prominent role in the dialogue on child rights and the role of institutional care. These agencies vary in size, approach, expertise, and resources: some are direct service providers, others fund services provided by third parties, and some have an advisory or influencing role, encouraging and directing transformation remotely. The international agencies we consider can broadly be defined in terms of three characteristics that can influence the operation of care systems: (1) resources—the deployment of resources to support and leverage the work of local government and civil society actors; (2) information, knowledge, expertise, and practice—the facilitation of access to evidence and expertise; and (3) influence—the mobilisation of financial networks and decision makers to influence policy and practice and to leverage funding.

When directed effectively, these international agencies can have a vital positive role in catalysing care transformation; however, if misdirected, they can distort care systems by reinforcing outdated approaches that are not aligned with the needs and rights of communities, households, and children.27

Many global faith-based organisations inspired by the teachings of Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindi, Jewish and other religious traditions are also engaged in a variety of initiatives concerning the care of children, and we consider these organisations next. Faith traditions can be powerful agents for change given their ability to mobilise consistent and predictable resources to some of the most marginalised places in the world. Often, these organisations have primarily promoted institutions as the model of care for children. However, a growing number of faith-based organisations are recognising the harmful effects of institutional care, and have increasingly refocused their efforts on transitioning children from institutional to family-based care (appendix p 3).28, 29, 30, 31, 32

Finally, we consider volunteers, visitors, and private donations, which are all important drivers of institutionalisation. The practice of combining holiday with voluntary activity on service projects abroad is popular with many young people, families, and faith missions. Often inspired by good intentions, volunteers work alongside staff in institutions and so in principle can add to the available resources that a child receives. In practice, this is often not the case, and volunteering during holidays (sometimes referred to as voluntourism) can have a series of unintended consequences.33 Institutionalised care is often characterised by fragmentation because of its regimented nature, high child-to-caregiver ratio, multiple shifts to cover continuous care, and the high turnover of underpaid and insufficiently trained staff.4, 34 Volunteers can unintentionally add to this neglectful and fragmented care, especially in situations in which visitors stay in institutions for only a few days, weeks, or months, thus increasing the instability of the care arrangement. This instability can cause children to feel abandoned and might reinforce indiscriminate behaviours. Furthermore, most of the volunteers have not been trained in caring for children, let alone in taking care of children with physical and mental health delays and impairments.35, 36 Volunteers are also important funders of institutions (panel 3 ).

Panel 3. The negative effects of volunteering.

Volunteering in institutions can elevate the risks to children living in those institutions.33 Many of the institutions in which volunteers work and that are funded and supported by volunteer organisations are of low quality, with unregulated and unsupervised facilities. Some institutions are known to serve as centres for trafficking and child sexual exploitation.37 A study in Malawi noted that more than 50% of the institutions for children included in the study were engaged in direct recruiting of children from families by the institution staff or other individuals.38 Even more concerning is that volunteers working in institutions during holidays are often not required to complete child-protection certification and training that is deemed essential in countries with more developed systems for child welfare. In many cases, volunteers have to pay to work in institutions, with money going directly to travel agencies in their own country and to local institution directors, creating a profitable voluntourism industry, which might be partly based on child trafficking.39, 40

ReThink Orphanages estimated the voluntourism industry to be worth around US$2·6 billion, involving 1·6 million people each year, although the precise proportion of this industry devoted to residential institutions for children is unknown.41 Some forms of volunteering can have beneficial outcomes,42 but volunteering at institutions for children carries great risks of perpetuating and even intensifying the fragmented care that children in institutions receive. The growth of voluntourism might have led to an increase in the number of institutions around the world, in particular, and not accidentally, in regions such as Nepal or Cambodia, which are attractive to young tourists.39, 43 One estimate found that at least 248 institutions for children in Cambodia were being financially supported by voluntourism.44 Several sectors are implicated in voluntourism, including the travel sector (including commercial gap year programmes) and the educational sector (eg, stimulating voluntourism as part of their curriculum or to build a more impressive curriculum vitae for students).45

Policy aims

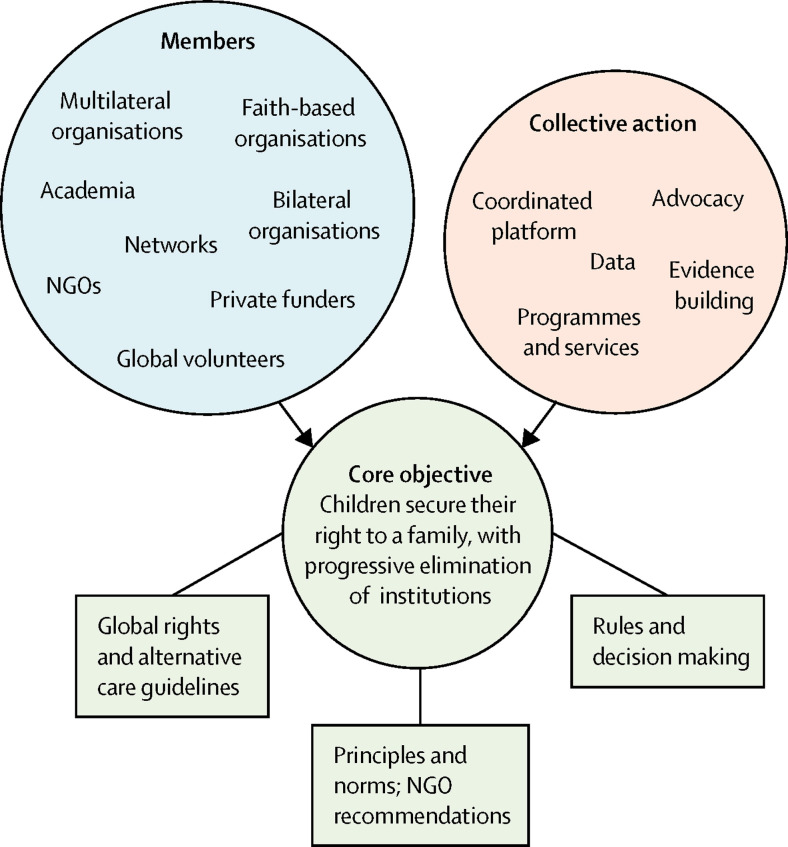

We propose the development of a fully-fledged, coordinated, and integrated global initiative promoting family-based care of children that supports the December 2019 UN General Assembly Resolution and aligns with the endorsed recommendations for this resolution.2, 3 This initiative would frame “sets of implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actors' expectations converge in a given area of international relations”,46 in this case, the welfare, care, and protection of children (figure 2 ). The global initiative should promote coordinated, collaborative, evidence-based, and resourced policies, programmes, and services that are embedded in international frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).47 The initiative should also promote family-based care and the progressive elimination of institutions as key components of national-level development strategies that aim for long-term and intergenerational poverty reduction, strengthening of human capital, and stronger local communities through a comprehensive continuum of care for children. All international agencies should work in a way that is aligned to local realities so that these agencies can stimulate and support government and local civil society to have a key role in the transformation of care processes. This role includes engaging the voice and participation of young people in identifying and supporting ways to transform care for children. It is essential that reform is culturally and contextually rooted and that international agencies promote sustainable national systems of care.

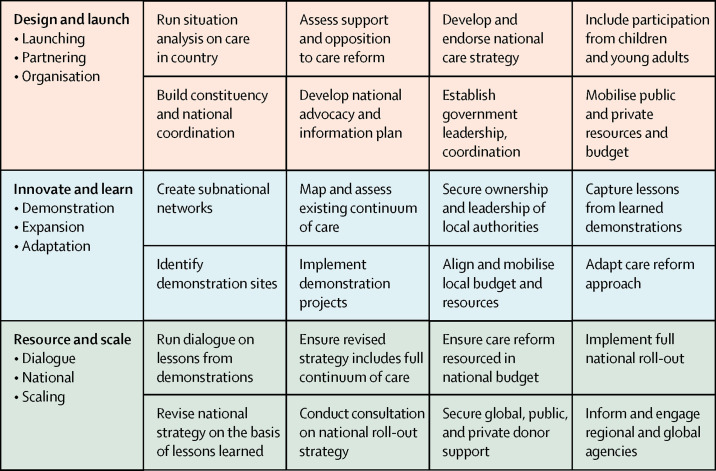

Figure 2.

Key elements of a global initiative on transforming the care of children

NGO=non-governmental organisation.

We commend the growing commitment of faith-based organisations to prioritise family-based care, support, and reintegration over institutional care, as well as policy initiatives that halt the volunteer industry in institutions for children over a transition period that enables the safe divestment and redirection of responses towards family-centred alternatives. Volunteer and faith-based inputs should be redirected to alternatives to institutional care—eg, actions to strengthen local family support systems and protective child services, and facilitating systems of kinship, kafalah, foster, and adoptive care of abandoned children. The progressive elimination of institutions for children in low-income countries might fail unless the contribution of high-income countries48 to the continuation of institutions is acknowledged and redirected.

Strategies for change

We recommend that the global initiative we have proposed be developed following the alignment of global rights with the mission of development-focused organisations on key principles, norms, and approaches that promote family strengthening and the progressive elimination of institutions, with special reference to the recommendations for the UN General Assembly Resolution on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Children (figure 2). Evidence of success will be shown in three ways: (1) active coordination between multilateral organisations on the right of children to family life and the role of families in the development agenda; (2) global and regional advocacy and evidence building; and (3) multilateral resource mobilisation and technical assistance to support the recommendations for the UN General Assembly Resolution. Family strengthening, family-based care (family of origin and alternative care), and progressive elimination of institutions should be incorporated into the social protection and welfare, health, education, justice, and interior sectoral strategies and programmes of multilateral organisations. The goal of our recommendation for this global strategy is both to secure the right of a child to a family and to promote recognition that supportive family dynamics improve human and social capital outcomes across the entire life of a child.49, 50, 51, 52

We have identified five ways in which multilateral organisations can affect the pursuance of this goal: (1) by engaging in advocacy and public information; (2) by issuing policy statements on children outside of, or at risk of losing, parental or family care; (3) by highlighting and generating evidence related to the benefits of safe and nurturing family-based care, the harms of institutionalisation, and examples of the reform process; (4) by supporting and resourcing government policies and programmes, including by providing technical assistance to support family-based care, the reintegration of children, and the progressive elimination of institutions, and by financing projects that show the benefits of a family-centred child welfare system; and (5) by pressing for the assemblage of data relevant for monitoring the situation of children in all forms of care. Multilateral organisations can advocate globally to show that the institutionalisation of children is not an appropriate or cost-effective response to poverty, risk, vulnerability, or the loss of family, and they can work together to issue joint resolutions, strategies, and statements on the norms and approaches for supporting family-based care and the progressive elimination of institutions. Multilateral organisations can also mobilise global evidence to promote stronger systems for child welfare and protection, with the human and financial capacity to make use of social work and case management approaches to provide individualised support services to children and families.53 These organisations can also work with governments to ensure that public policy and medium-term budget frameworks have adequate provision for the support of a child welfare system that strengthens families, prevents child separation, and promotes the safe transition of children into family-based care.

Non-governmental organisations should develop effective case management systems, implemented by trained professionals, for developing plans for the children and families they work with. These plans should be based on an assessment of the circumstances of each child and family, and ensure regular support and monitoring of placements by trained social service providers.54 The Faith to Action Initiative55 has prepared tools and resources on evidence-based approaches to care for faith-based organisations, and these resources can be consulted and used by organisations supporting institutions abroad. These resources include information about why the transition to family care is needed, how to understand and plan for the transition, how to engage key stakeholders including staff who work in institutions, how to develop a business model to sustain the transition, how to prepare children and families and support a continuum of care, and approaches for monitoring and evaluation of programmes, services, and child placements.

Faith-based organisations also have a unique potential to work to update knowledge, attitudes, and practices in their communities to strengthen families and to promote the importance of the welfare and protection of the child. The effect of these organisations can be felt globally through the voice and advocacy of recognised faith leaders, as well as locally through the words spoken by religious leaders at faith gatherings in their communities. Faith-based organisations should work in tandem with government and other local agencies and organisations to support stronger systems for child protection and to progressively eliminate the reliance on institutions. Such collaborations can be facilitated by a recognition of the practical experience and community knowledge that faith-based organisations can bring to the dialogue on improving care for children. In this sense, the policy recommendations for faith-based organisations are generally not distinct from other global organisations, and include the need for good evidence and data and reliable programmes and services that promote safe and nurturing family-based care for children.

We recommend that fiscal policies in high-income countries promote family-based care over supporting institutions in low-income countries. Policy makers should review tax breaks for donations and financial transfers to institutions by volunteers, and identify processes that reduce incentives to support institutions in a deliberate and phased manner that does not cause unconsidered reactions that could be harmful for children in the short term. Travel agencies that focus on volunteering in institutions should be regulated more strictly. Educational systems should be discouraged from promoting, and be encouraged to prohibit, volunteering in institutions in the curriculum. A self-assessment tool on ethical and responsible student travel has been developed to inform trips abroad and should be used by volunteers.56 Policy also has a role in informing public opinion of the detrimental effects of seemingly altruistic contributions of time or money to the institutions. Universities, colleges, and vocational schools can cooperate to build professional and scientific capacity for family support and child protection. That said, an immediate cutoff of funding to any institution could be harmful to the children residing there: existing donors to institutions should accordingly work on supporting a short-term transition plan to ensure that children and families are well supported.

Implementation of change

Numerous successful global initiatives with a focus on rights and development issues are being developed and supported by multilateral organisations. Universal Health Coverage 2030 (UHC2030) supports the health-related SDGs and coordinates the work of 66 partners, including 13 multilateral organisations, in four areas: advocacy, accountability, knowledge exchange and learning, and civil society engagement.57 Multilateral organisations such as the UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the World Bank, and UNICEF have also come together under the Global Partnership for Education, which aims to strengthen education systems in low-income countries.58 These and similar collaborations have been well positioned to coordinate international efforts to improve health and wellbeing by issuing global frameworks, strategies, action plans, goals, initiatives, statements, declarations, codes of practice, regulations, and documents, and have substantial convening power at the global, regional, and country levels (eg, at summits, conferences, and evidence reviews). These collaborations are good examples of how a global initiative might be formulated around care for children.

UN declarations have been a catalyst for multilateral coordination, as evidenced by the founding of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria by the G8 in 2001.59 The December 2019 UN General Assembly Resolution on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Children has been a similar opportunity for multilateral organisations to collaborate. UNICEF's mandate, which includes a global child protection portfolio and the ability to engage directly with member governments on policy, suggests that this organisation might be best placed to coordinate multilateral engagement in the protection of children who are at risk of, or placed in, institutional care. International agencies should make policy and funding commitments to transform care systems on the basis of an evidence-based acceptance of the right of a child to live in a family environment and of the harm that institutions do to the development of children. For example, the UK Aid Direct60 official funding guidance from the UK Government's Department for International Development does not accept funding proposals from non-governmental organisations for residential children's institutions. This funding guidance is consistent with a cross-government policy position stating that “[t]he UK government will continue to tackle the underlying drivers of institutionalisation and work towards the long-term process of de-institutionalisation”.61 A US Government strategy for 2019–23, Advancing Protection and Care for Children in Adversity (appendix p 4),62 commits to improving care for children by building strong beginnings and by placing family first in its international development funding. This commitment can be leveraged to encourage other governments to support the transformation of care for children and to recognise the roles of some governments in influencing care reform in other countries.

When conducting dialogue at a national level, international agencies should do a thorough analysis of the care system of that country, including budgets, finances, and its cultural context, by consulting with national and local government and civil society, so that support can be directed to where it is most needed and effective. Efforts by international agencies should complement and enhance national governmental initiatives and should avoid establishing parallel systems of care that embrace both institutions and programmes for child welfare. International agencies should use their resources to develop and strengthen models of practice across the continuum of care by piloting proof of concept examples to convince national stakeholders that change is achievable, economically sustainable, and will deliver better outcomes for children. International agencies can have a vital role in championing the views of communities and children, including children with disabilities, who are often left behind in development initiatives (panel 4 ). International agencies need to help to make the case for reform by uncovering human rights abuses and concerns; examples of such work include the investigations by Human Rights Watch into the institutional systems in Kazakhstan64 and Russia.65

Panel 4. Children with disabilities.

The right of children to family life is clearly articulated in the Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities.13 Children with disabilities have been disproportionately represented in institutions around the world, presenting substantial concerns about the effect on their development, health, and welfare, their exposure to abuse, and their isolation from their families and communities. Children with disabilities are often placed in institutions because families have few resources and supports, and the children often face stigma and discrimination in their communities. The US Agency for International Development has supported the preparation of a guidance document providing practical recommendations for organisations working with children with disabilities in low-income and middle-income countries.63 The guidance summarises the rights of children with disabilities, the types and effects of disabilities, and the social model of disability. The approach promotes fully inclusive services and programmes for children with disabilities and is based on the development and strengthening of case management systems that can identify and assess children with disabilities and support the identification and implementation of a case plan for each child. The approach also includes measures that are focused on engaging communities and overcoming stigma and discrimination. UNICEF estimates that there are 90 million children with disabilities globally, and institutionalisation is only one dimension of the challenges these children face. Global organisations can have a crucial role in helping countries to develop and implement policies, strategies, programmes, and services for all children with disabilities, while also ensuring that children with disabilities who live in institutions, and are therefore generally most at risk, are a focal point of their efforts.

International agencies have, in many situations, helped to drive care reform at national, regional, and global levels. Many examples also exist of situations in which the practices of international organisations can distort care systems, despite laudable intentions. By establishing parallel systems of care, these organisations can divert valuable resources away from family and community services. For example, research in Haiti has found that an estimated US$100 million per year is channeled into institutions for children from international funders, which is approximately 130 times more money than the annual budget for the Haitian child protection agency.66 The availability of these resources, which are often well intentioned, distorts Haitian care practices by driving the establishment of new institutions, some of which are established with the aim of securing profits. At the same time as funding institutions, international agencies have, at times, imposed practices that are insensitive to local systems, culture, and capacity. These practices can lead to inappropriate forms of care, short-term projects that do not tackle the root causes of the problem, or the provision of working incentives, such as salaries and daily living allowances, that can reduce the effectiveness of intervention activities.67

Some faith-based organisations are beginning to make the implementation of care reform possible. Changing the Way We Care, a consortium of Catholic Relief Services, Lumos, and Maestral International that has been funded by the MacArthur Foundation, the US Agency for International Development, and the GHR Foundation, is mobilising resources to support a transition from faith-based care in institutions to strengthening families, and to progressively eliminate institutions for children through a combination of dialogue and demonstration projects.68 In May 2019, the International Union of Superiors General, representing around 600 000 Catholic Sisters from 80 countries, held a 2-day workshop to discuss the importance of family-based care of children and the need to shift away from institutional care,29 and Catholic Relief Services incorporated family care and reduced reliance on institutions in its 2019 Vision 2030 strategy, which covers more than 100 countries.69 The planned 2020 annual summit of the Christian Alliance for Orphans includes sessions on preventing family separation, strengthening systems for child protection, addressing reintegration of children into family-based care, and supporting alternatives to institutions.28, 70 The Organization of Islamic Cooperation has announced that the Day of the Orphan would be observed on the 15th day of Ramadan every year.71 These and similar initiatives are encouraging, but implementation support will be needed to ensure that well meaning initiatives are designed with appropriate assessment, referral, support, and protective mechanisms to enhance outcomes for child welfare. These outcomes should be regularly monitored and assessed.

Securing political will to address the issue of volunteering for or visiting institutions for children in low-income countries has been challenging. In 2018, the Dutch Parliamentary Committee for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation initiated a policy debate on discouraging voluntourism with an extensive report by Wybren van Haga.72 In a first reaction to this report, the Dutch Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation questioned the need to focus specifically on voluntourism, because the more fundamental problem was poverty, and solutions would already be embedded in policies to reduce poverty and secure children's rights more generally.73 However, in a meeting with the Dutch Parliamentary Committee, the report was received positively by many psychological, anthropological, and legal experts.74 In a subsequent, final response, the minister announced the installation of a committee to study the issue and to outline possible policy implications.75 Australia has so far been the most successful country in developing specific legislation on volunteering in children's institutions, and is a potential model for other countries (panel 5 ). Faith-based organisations have been increasingly engaged in discussions about the effect of voluntourism and are beginning to acknowledge the negative consequences of volunteer work with children in institutions.78

Panel 5. Legal reform in Australia.

In 2017, the Australian Parliament initiated a committee to inquire into establishing a modern slavery act. Submissions to the committee highlighted that the availability of donations and volunteers helps to create incentives for sustaining or expanding the number of institutions for children operating outside of the law or without regulation. 57·5% of Australian universities advertise institution placements for students and 14% of secondary schools visit, volunteer at, or fundraise for overseas institutions. Submissions indicated that many children in institutions do have a living parent, but that parents perceive, or have been told by institution recruiters, that their child will escape poverty through access to education and a better life in the institution. In their submission to the committee, the ReThink Orphanages coalition of non-governmental organisations reported that once in the institution, “children are often kept in poor health, poor conditions and are malnourished in order to elicit more support in the form of donations and gifts”.76

The committee heard evidence from Ms Sinet Chan, who had been placed in an institution in Cambodia. Ms Chan had been subject to physical neglect, and physical and sexual abuse in the institution, and was used as a commodity for the institution: “The orphanage got its funding from the tourists and, when the tourists came, we needed to perform for them to make them happy, like singing a song, playing games with them and learning English and Japanese. Sometimes they would buy us some clothes or food, but we were not allowed to keep them. The director of the orphanage would take them back to the market and sell everything…We worked so hard to generate income for the orphanage. It was only later that I realised I was being exploited and used like a slave”.76The committee concluded that there is persuasive evidence that “children are trafficked into orphanages for the purposes of exploitation to elicit donations from foreign tourists,” and “take advantage of voluntourists”.76 The committee recommended that statutory measures should be implemented to reduce the flows of money and voluntourism that sustain orphanages at the expense of sustaining and enriching family life, and that this situation should be considered a form of modern slavery.

The Australian Government has committed to policy changes to increase responsible donation and volunteering to avoid supporting institution trafficking, including work with the Education Council to reduce institution placements for university students. The Modern Slavery Act was passed in Australia in 2018; in an explanatory memorandum to the Act, “the trafficking and/or exploitation of children in orphanages”77 is explicitly stated, and individuals who engage in it are considered to be enacting modern slavery.

Monitoring and evaluation of change

International commitments to reforming the care of children can be monitored through assessments of the extent to which global agencies are successful in creating a global initiative to strengthen families and communities and progressively eliminate institutions, along with evidence on how resources and funding are being redirected to those purposes.79 International agencies should take advantage of their position to coordinate substantial global advocacy initiatives, such as the 2016 All Children Count campaign.38 This campaign collected more than 250 signatories from organisations, non-governmental organisations, and academics to encourage the UN Statistical Commission and Inter-Agency Expert Group on SDG Indicators to improve and expand data collection methodologies, in order to ensure that all children living outside of households, who are often not captured in data collection instruments such as household surveys, are represented. The Changing the Way We Care68 initiative is preparing a comprehensive and cross-cutting set of monitoring tools that could be used to track global progress on care. Monitoring tools have also been prepared by a group of agencies facilitated by the Better Care Network and Save the Children, as well as by MEASURE Evaluation.80, 81, 82

The millions of children living in institutions have not been monitored regularly, and the number of these children has not been systematically counted. Multilateral organisations can help to address the urgent need to improve the collection and reporting of data about children in institutions.1 Multilateral organisations should closely coordinate on these efforts to improve the quality and reliability of data and include them in the ongoing dialogue on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which strives to “provide children and youth with a nurturing environment for the full realization of their rights and capabilities, helping our countries to reap the demographic dividend including through…cohesive communities and families”.47 At the national level, global organisations should support and resource efforts to provide high-quality longitudinal data and information about family care, including information about children living without parental care, while ensuring that collection methods are ethical and support the privacy of children. Global organisations can also help to strengthen national administrative data collection on all forms of alternative care by basing data collections systems on comprehensive and secure individual records for each child.

Key recommendations

We have six key recommendations for measures that global actors should enact to reform care for abandoned children. (1) International agencies should launch a joint global initiative to support key principles, norms, and approaches that promote family strengthening, family-based care, and progressive elimination of institutions. (2) International agencies should promote and support improved data collection, monitoring, and reporting on children outside of family care as part of increased organisational accountability. (3) International organisations should make policy and funding commitments to transform care systems for children, addressing the drivers of institutionalisation, supporting the strengthening of government social and child protection systems, targeting trafficking of children into and from institutions, and progressively redirecting funding from institutions to family-based care over a deliberate, phased, and safe transition period. (4) Stakeholders should incorporate the views of children and young adults in development initiatives—particularly the views of individuals who are commonly over-looked, such as children with disabilities—and highlight the case for reform by uncovering human and child rights abuses and concerns. (5) Faith-based organisations and leaders should work with other stakeholders and use their voices to change knowledge, attitudes, and practices in their communities to promote the importance of the welfare and protection of children in family-based care, and to strengthen families. (6) Volunteer input should be redirected to alternatives to institutional care—eg, actions to strengthen local family support systems and protective child services and supporting systems of kinship, kafalah, foster, and adoptive care of abandoned children.

Section 2: The role of national-level actors

In this section, we focus on four key elements that are related to the transformation of care systems at the national level: the current context of most national systems; policy aims for strengthening national care systems and promoting family-based care; how to develop or strengthen national policies; and implementation and monitoring of national reforms.

National context

Momentum towards the transformation of national care systems has multiple drivers, including the availability of global research; national commitment to international conventions, standards, and guidelines; accelerating economic growth, reduction of poverty, and welfare enhancement; and support from international, national, and local agencies.83, 84, 85, 86 Even when supportive of reducing institutionalisation, low-income countries generally have little capacity to provide access to quality services for child welfare and protection for a variety of reasons, including poor funding and inadequate human resources.87, 88, 89 The policy priorities of governments often conflict between preventing institutional care and developing new services and transforming their care system.90 Additionally, because many institutions are not financed through government budgets, the costs of these institutions are often not visible to policy makers.91, 92 Clear strategies are necessary to incorporate care reform in initiatives for national development and poverty reduction that cut across sectors, and to mobilise the related resources.

Successful reform of care for children is complex, and although there is ample evidence of challenges, documentation of processes that work at the country level is scarce (but see panel 6 ).

Panel 6. Care reform in Rwanda.

In Rwanda, the process of reformation of care for children was initiated in 2012 and was driven in part by demands from children, made through the National Children's Summit. Several important processes were key to the success of the reformation process in Rwanda. Baseline data had already been collected in 2011, showing that there were 3323 children and adolescents in 33 different institutions, and these data helped to monitor progress over time.93 In 2012, the Child Care Reform Strategy was developed and approved by the Rwandan Cabinet, which articulated the shared vision for a system for the family-based care of children in Rwanda. The reform was supported by the 2003 Constitution of Rwanda, the 2011 National Integrated Child Rights Policy, and the Child Protection Laws of Rwanda. All of the national legal and policy frameworks emphasise the importance of families and of the right of children to grow up in families. In 2012, the Tubarerere Mu Muryango (TMM) programme, translated as Let's Raise Children in Families, was developed to help to operationalise the strategy for the reform of care for children, and included key goals, targets, and timelines. This programme was led and overseen by a national authority, the National Commission for Children, with systematic implementation in collaboration with implementing partners. A national 2-year mass media campaign accompanied the implementation of the first phase of TMM, which focused on increasing understanding of the harm caused by institutional care, and the benefits for children growing up in families. By the end of the first phase of the TMM programme, 12 institutions had closed and a further 14 institutions had transformed to provide community-based services. From 2012 to 2017, more than 3000 children and adolescents had been placed into family-based care or independent living.93

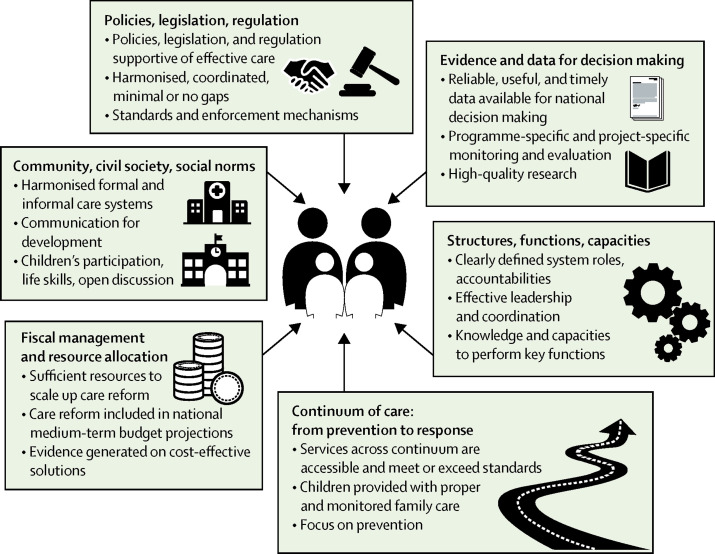

Evidence is consistent in suggesting that contexts and conditions that vary between countries are taken into strong consideration when supporting and implementing changes in care systems at the national level. For this reason, there is no single way to successfully reform care for children at the national level. Our goal in this section of the Commission is to identify a series of useful factors and elements that might be important across nations with diverging cultural, economic, and political conditions. In particular, some initiatives are beginning to provide evidence that national reform of care for children must take a systems approach by working at multiple levels of society, including policy and national legislation, service development and delivery, public awareness and social norms, workforce, implementation mechanisms, management information and data systems, and resources including public budgets (figure 3 ).81, 94

Figure 3.

Key elements of a national care system

Policy aims

We recommend that all national policies, legislation, and regulations promote, support, and resource family-based care for children and family strengthening, while progressively transforming their care systems and eliminating the role of institutions. This aim should be backed by national advocacy efforts to build constituencies for change, with a strategic framework put in place to address priorities in strengthening systems for child welfare and protection. These reforms should be considered consistent with, and promotive of, national efforts to reduce poverty, to improve health and education status, and to reduce social problems such as violence, substance misuse, and children coming into conflict with the law. To secure this vision and strategy, it is essential that political will is generated across the full spectrum of political interests and individual roles, ensuring that key champions for reform are in positions of influence both within government and across the care system. These key champions should include individuals within non-governmental organisations, faith leaders, and people with lived experience of institutionalisation, including children and young people. This political will needs to be complemented by changes in public knowledge, attitudes, and practices that might currently accept the option of child institutionalisation as a viable (or even preferred) option for a child, or that might raise issues of stigma for children placed into a family.

This vision needs to be underpinned by a realistic and appropriately resourced plan to safely transform care systems to work in the best interests of children. National plans should be based on consultations with key national and international partners to ensure that these plans are informed by international experience of care reform. These consultations will help to ensure that the process, timing, and phasing are set at a pace that is realistic, are based on a thorough assessment of the needs and rights of children and their families, and cover the range of provision required across the continuum of need, from early help and family support services to alternative care (figure 4 ).93 Successful reform of care for children is underpinned by high-quality care and practice and is informed by meaningful child participation that is ethically done and effectively monitored and evaluated.95 The goal of reform is to ensure that national policies promote increased access to high-quality programmes and services that address the drivers of institutionalisation and support the placement of children in safe and nurturing families. Children who are at risk of losing parental care, or who are without parental care, should also be enumerated and monitored.

Figure 4.

The care continuum

Small, high-quality residential care facilities should be few in number and at the margins of the system.

Strategies for change

The ability to identify the sources of support for, and resistance against, change to care systems is a crucial first step in building effective movement. National leaders of care transformation should do a detailed stakeholder analysis, identifying the individuals or groups with influence over a nation's system for child protection and the broader systems (such as welfare, family support, health and disability, education, criminal justice, and housing) that can affect the risk of a child entering the care system. Such an analysis should assess and map the awareness, motivations, attitudes, and commitment towards care transformation among these diverse stakeholders (appendix p 5). This analysis will inform the development of an advocacy strategy to ensure that the key decisions and decision makers are mapped and targeted to build momentum for reform and to ensure that reform is enshrined in relevant policies and guidance.

Reforming systems requires an understanding of the barriers against change and the levers for change. Plans should therefore be developed on the basis of a thorough evaluation of the existing care system. This evaluation should include collection of reliable data on the numbers of children in institutional and other forms of care; identification of the needs and number of vulnerable families and children who are at risk of separation; identification of opportunities and incentives for promoting family strengthening and family-based care; analysis of existing services and gaps in those services; identification of barriers to family-based alternative care; consideration of current policy and legislative framework; understanding of community and public attitudes and behaviours towards care for children; assessment of the capacity of the existing social workforce; evaluation of existing funding streams and practices to carefully identify policies and practices that perpetuate institutionalisation and inhibit efforts towards care transformation; and making the investment case for reform.96, 97, 98 Analysis should not be limited to infants and should include all children in institution-based care, and should incorporate evidence-based practices for all children who cannot live with their families.90

The system for the care of children, including residential care and short-term treatment facilities, should be closely overseen by designated government authorities, and should be in line with the principles of necessity and suitability as per global conventions and instruments. Governments, service providers, and civil society should formulate a vision of a coherent system for the care of children, ensuring that this system is oriented towards family care for children and is situated within a broader system of child protection.99 Resources are available to help map child-protection systems and to evaluate and prioritise the needs of these systems, and these resources are highly relevant and useful for countries that are engaged in care reform.53, 82 Furthermore, countries should understand the wider social norms, attitudes, and practices that promote and perpetuate child–family separation, institutionalisation, and the absence of comprehensive family support and family-based alternative care, including discrimination against ethnic and cultural minority groups, discrimination against children with disabilities, gender-based discrimination, discrimination based on sexual orientation, attitudes towards children affected by violence, and attitudes towards adolescent parents. The same research that gathers information on these social norms can discover insights into the cultural acceptance of both traditional (such as informal kinship care) and more novel forms of care for children, providing important foundations for future care planning and the development of models such as adoption and foster care. The insights that are gathered will be key to influencing stakeholder engagement throughout the transformation process, especially to align different motivations and to build a common purpose among different actors.

Building engagement through a nationally adopted framework that outlines a plan to support child welfare and protection and to progressively eliminate institutions is a powerful tool to ensure the sustainability of the process to prevent institutionalisation, enhance the quality of alternative care, and preserve families. We recommend that governments develop such frameworks together with national and local authorities, non-governmental and community-based organisations, and with the participation of children and families. Convening relevant ministries and organisations can reduce the challenges in coordinating services and mobilising resources (appendix p 6).100 Monitoring progress and identifying problems can be done more effectively using a shared implementation framework and targets.

Implementation of change

The recent history of care reform highlights two major ways in which implementation can be done ineffectively. The first involves top-only national policy proclamations and strategies that are announced with little meaningful stakeholder engagement and scant consideration of the practicalities of implementation. Such efforts typically flounder because the gap between policy aspiration and operational reality is inevitably exposed. The second involves bottom-only projects and initiatives to transform individual institutions in isolation from the national policy context, with little attention paid to the wider drivers leading children to enter care. In such cases, even when improved outcomes are secured for the individual children and families supported by these projects, the reforms do not have the scale to reach all vulnerable children, nor do they have the breadth of scope to effectively tackle the underlying causes of institutionalisation.

Interventions at the systemic level are more likely than either the top-only or bottom-only approaches to promote the transfer of resources from institutions to alternative care programmes and services. We argue that safe, effective, and sustainable care transformation is a dynamic process that requires the building of a broad constituency of support, the mobilisation of a movement for change spanning actors from different sectors, and a national system to support children and families at all levels. Without these foundations in place, efforts aimed at reform are likely to be piecemeal and short lived. Reform must be reinforced by a shared understanding of the problem, including of the costs and harms of institutionalisation to children, families, and society, and of the relative benefits of family-based care alternatives. The drivers of institutionalisation are complex and multifaceted and require actors from multiple agencies and levels to work together to tackle the issues that lead to family separation. It is crucial to understand norms, attitudes, and practices that contribute to institutionalisation, and to understand the informal family and community mechanisms that can both mediate and mitigate risks to children and families. Policy makers need to be provided with evidence of successful reform from relatable contexts. Programme managers and service providers currently working in the system need to be able to envision how their own roles can change for the better as reform unfolds.

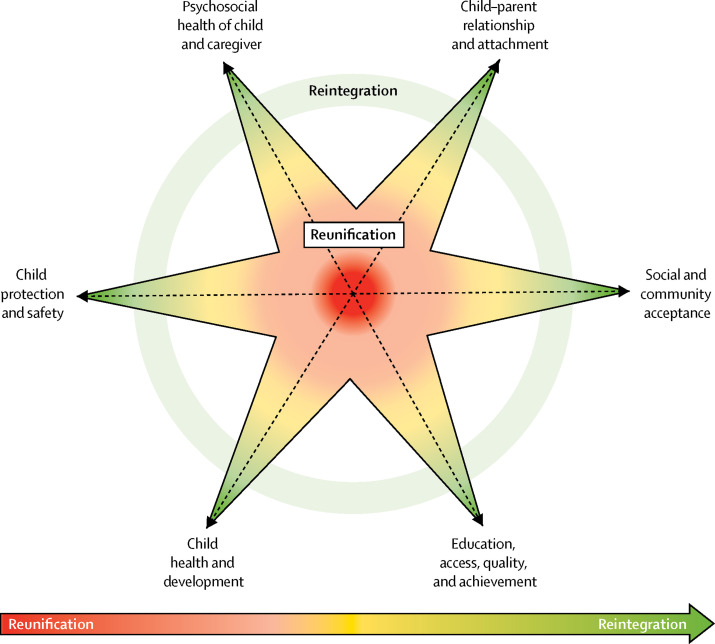

Once a shared understanding of the problem is secured, one of the main challenges in implementing successful reform of care for children is the absence of a common national vision, strategy, and plan for reform. It is important for governments to develop an overarching vision that outlines the ambition for reform and key milestones throughout the process. Governments should ensure that the vision for the care system is supported by a strong legislative basis with a national authority that is mandated to coordinate the implementation.101 This high-level vision sets the overall goal of reform and can act as a broad and accessible statement for partners involved in supporting the care system, including public and private contributors, to confirm a shared commitment. As already noted, the perspectives of children and young adults should be included in developing such a national vision, and the strategy should be inclusive of key risk groups, such as children with disabilities. Once agreed, this vision can be underpinned by a high-level strategy that outlines the intent, objectives, resourcing requirements, management and coordination structures, and resourcing implications. One approach to considering how to scale up national care reform efforts is illustrated in figure 5 .

Figure 5.

Model for scaling up national care reform

The content and sequencing of measures to scale depend on country context.

To meet the goals outlined in this section, we recommend that national governments create partnerships, develop a qualified workforce, and provide appropriate funding. We recommend that reform of care for children is led by government but involves strong national partnerships with others to take forward implementation. Partnerships could be implemented with groups such as civil society organisations, bilateral and multilateral organisations that provide technical support and funding, and local organisations. Partnerships should be coordinated through a national coordination platform led by the national authority.102 Implementation of a reform strategy cannot take place without personnel who can dedicate substantial time to the process and who are able to professionally assess children and families, work alongside institutions and communities, place children in families, and follow up placements. These roles are best suited to qualified professionals such as social workers.103 The government should ensure that standards are in place, with monitoring and inspection, and that there are opportunities for development for the social workforce. Additionally, it is important not to neglect the skills needed to plan and monitor the reform process, which is a major initiative for social change that requires dedicated professionals to oversee and support it. These skills can be supported by a robust training system, which in some contexts might benefit from partnering with universities and experts operating abroad.

One of the main principles of funding care reform is to progressively reduce and redirect resources that can contribute to the placement of children in institutions.104 National budgets for such a reform should include resources over the short, medium, and long term to fund the continuum of care at a level that will ensure access to, and quality of, services. UNICEF and Changing the Way We Care have been actively supporting public expenditure reforms, including costing and budgeting, to support the resourcing of care for abandoned children. The care transformation process also requires the systematic identification and redirection of both public and private resources from institutional to family-based care as the number of children in care decreases (panel 7 ).

Panel 7. Addressing structural and financial barriers in Jordan.

In 2011, with the support of UNICEF and Columbia University (New York, NY, USA) and its Global Center in Amman, the Government of Jordan launched an initiative to develop a foster-care system to support the transition of children from institutions to families. The initiative was approved by the religious Ifta Council and endorsed by the royal family of Jordan. The programme was piloted in one city, and later expanded to predominantly three cities, serving around 260 foster placements. There were several contextual challenges during the programme development. These included the nascent stage of the professionalisation of social work and limited governmental capacities (both logistic and human resources). To compensate for those needs, a public–private partnership was developed in which the Jordanian Government outsourced the majority of the required services through carefully selected partner non-governmental organisations. The programme also incorporated evidence-based psychosocial interventions (adapted specifically for foster care in the Jordanian context), together with an assessment of each child so that the appropriate support for foster families could be identified and provided before actual placements start. Because of an absence of Arabic literature on optimum foster care and psychosocial interventions, manuals were developed with step-by-step guides on the selected interventions. Moreover, an extensive training module was developed to enable parasocial-work practitioners to implement the adopted interventions in adherence with programme standards. This module included 20 h of training, followed by shadow training and clinical supervision. To protect the quality of services, strengthen implementation, and promote expansion of the programme, comprehensive standard operating procedures were also developed. However, despite these good practices, the programme is now facing challenges due to budget cuts and a high turnover of previously trained paraprofessionals. Although many children remained with families, some (19 of 260) were placed back into children's institutions because of inadequate financial and psychosocial support for foster families. Inadequate budgets meant there were insufficient resources to support a comprehensive system for the welfare and protection of children, or to improve outcome monitoring for children who are placed in care. Although national policies are important, it is crucial to have strong local ownership, accountability, and collaboration to build the foster-care model. It is also important to have systems in place to ensure placement monitoring and reintegration support. Jordan is learning from these and other lessons to further strengthen and expand the foster-care system.

In many cases, investments will need to be made to support the transition from institutions, but because institutions are generally much more costly than programmes for child welfare and protection, cost savings can be used for family care and for strengthening services in the community. Modelling the financial implications of reform is essential because without a long-term resourcing plan, the reform process could be unsustainable, and resistance might be encountered from institutions concerned about losing employment and funding for their business.90

Monitoring and evaluation of change

It is crucial to ensure that a monitoring and evaluation plan is developed to support and assess the implementation of a national strategy for reform of care for children. Although many countries have strategies that include methods for tracking the progress made, often these strategies neither represent nor include a nationally agreed framework for either alternative care for children or the linkages to child protection or strengthening families. Governments tend to collect and report administrative data, if they collect data at all, which are often largely quantitative in nature. Qualitative data that can help the authorities to contextualise and interpret the quantitative data, and help to answer questions about the quality of care and the outcomes of alternative care for children, are available at the service level and at the levels of local, subnational, and national authorities. Often institutions for the care of children have their own information systems and use the data they collect to plan care for individuals. However, the qualitative data collected in individual institutions are not systematically analysed and aggregated and are therefore not used at the national level to inform policy making, planning, and programming. Various national stakeholders collect data that could be relevant for children in alternative care; however, these data are often not integrated into national reports. A strengthened monitoring and evaluation system will act as a basis for robust governance arrangements and performance, which are necessary for the achievement of evidence-based policy-making, budget decisions, programming, management, and accountability in developing and delivering family-based services.

The main challenges in relation to the monitoring and evaluation of reforms to the care of children relate to the insufficient capacities of governments and other stakeholders who are involved in reform to design, plan, and implement effective policies and frameworks and to the inability of governments and other stakeholders to mobilise resources to boost these capacities. Governments often are not able to establish a robust baseline of all children in institutional care or to conceptualise an effective monitoring and evaluation framework that covers the complex process of transforming a system for the care of children. Additionally, in the process of implementing reforms of care for children, governments tend to ignore the monitoring and evaluation system elements (eg, data collection and analysis) that are already in place, and fail to bring these elements together in a comprehensive and interoperable framework for alternative care. The capacity issue is also exacerbated by the inability of governments to identify and provide earmarked funding to cover the costs of effective systems to monitor alternative care at any level, particularly the costs associated with building the capacity of organisations involved in implementation, such as civil society organisations and the private sector.

First, monitoring and evaluation strategies and policies should be child-centred, should consider the developmental stage and needs of each child, and recognise that the goal of a system for the care of children includes strengthening family ties and preventing child–parent separation. Hence, plans for reform should not only target service provision, but also the developmental outcomes of children and family functioning.