Abstract

Tropical marine ecosystems are highly vulnerable to pollution and climate change. It is relatively unknown how tropical species may develop an increased tolerance to these stressors and the cost of adaptations. We addressed these issues by exposing a keystone tropical marine copepod, Pseudodiaptomus annandalei, to copper (Cu) for 7 generations (F1–F7) during three treatments: control, Cu and pCu (the recovery treatment). In F7, we tested the “contaminant-induced climate change sensitivity” hypothesis (TICS) by exposing copepods to Cu and extreme temperature. We tracked fitness and productivity of all generations. In F1, Cu did not affect survival and grazing but decreased nauplii production. In F2-F4, male survival, grazing, and nauplii production were lower in Cu, but recovered in pCu, indicating transgenerational plasticity. Strikingly, in F5-F6 nauplii production of Cu-exposed females increased, and did not recover in pCu. The earlier result suggests an increased Cu tolerance while the latter result revealed its cost. In F7, extreme temperature resulted in more pronounced reductions in grazing, and nauplii production of Cu or pCu than in control, supporting TICS. The results suggest that widespread pollution in tropical regions may result in high vulnerability of species in these regions to climate change.

Subject terms: Tropical ecology, Environmental impact

Introduction

The tropical coastal marine ecosystem in the South China Sea (SCS) is one of the most polluted regions worldwide1–3. High levels of metals have recently been reported in the coastal water of this region4,5, and metal pollution was one of the major causes of a recent massive fish kill in the SCS6. Furthermore, metals are persistent in the environment, and chronic exposure to metals often lasts beyond the course of one generation. Species may respond to multigenerational exposure to metals by evolving in phenotypic plasticity or development of adaptation. The role of phenotypic plasticity and adaptations in shaping the vulnerability of species to metals has been largely ignored in model predictions of ecotoxicological studies and ecological risk assessments of contaminants. Detangling phenotypic plasticity and adaptation is of crucial importance to understand how organisms may persist in nature and to improve ecological risk assessments, especially in the Anthropocene, where no coastal and marine ecosystem is free from anthropogenic disturbance1. A simple, yet powerful method to separate phenotypic plasticity and adaptation includes an experimental setup where organisms first are exposed and thereafter placed in clean conditions to examine if the stress response remains (adaptation) or recovers to control level (plasticity)7.

In general, organisms typically develop increased tolerance to long-term exposures to contaminants as a result of transgenerational plasticity, genetic adaptation, or both8–11. Multiple generational experiments have been applied to test how aquatic animals develop tolerance to stressors, such as metals11, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons10, pesticides12, algal toxins13, and temperature14,15. However, it remains a major challenge to detangle whether phenotypic changes in response to stressors are caused by transgenerational plasticity or from genetic adaptation. Adaptations to one stressor often come at the cost of reduced plasticity16 or reduced capacity to deal with additional stressors17. There is increasing evidence that transgenerational plasticity and adaptations to non-contaminant stressors may alter the sensitivity of organisms to a range of contaminants12,18–21. For example, Dinh et al.22, using space-for-time substitution, showed that thermal adaptation of aquatic insects results in a higher vulnerability to pesticides. This result supports the “climate-induced toxicant sensitivity” hypothesis23. However, the “contaminant-induced climate change sensitivity” hypothesis (TICS)17,23 remains to be tested.

This study aims to experimentally detangle phenotypic plasticity and adaptation as well as the cost of metal adaptation of a keystone tropical marine zooplankton species in response to exposure to a widespread contaminant (Cu) using an evolutionary experiment. We hypothesize that (1) tropical zooplankton develop adaptation to Cu after multigenerational exposure, and (2) the adaptation to Cu makes them more vulnerable to other stressors, particularly warming as predicted by Moe et al.17. To test these hypotheses, the tropical calanoid copepod, Pseudodiaptomus annandalei, was exposed to Cu (15 µg L−1) for seven generations. We quantified the changes in four key fitness traits, including survival, size at maturity, grazing rate (via faecal pellet production) and reproductive success (via nauplii production). A common tropical coastal copepod P. annandalei was chosen as the study organism as it plays an important role as the primary grazer on phytoplankton and small protozoans24,25. P. annandalei also provides the major food sources for marine fish larvae and juveniles in coastal marine ecosystems in SCS26.

Results

F1 generation

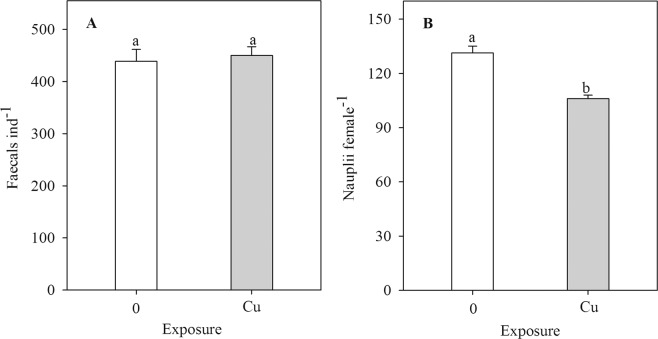

All females survived after 7 days, and survival of males was 72 ± 5% and 76 ± 5% (means ± SEs, n = 5) in control and the Cu treatment, respectively, and did not differ between the two treatments (F1, 8 = 0.20, P = 0.67). Likewise, size at maturity of females showed no statistical significance between the control and Cu treatment, and was 851 ± 8 µm and 864 ± 5 µm (means ± SEs, n = 5), respectively. Faecal pellet production did not differ between Cu and the control treatment (F1, 8 = 0.15, P = 0.71, Fig. 2A). Exposure to Cu reduced nauplii production by 19% compared to the control (F1, 8 = 33.97, P < 0.001, Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Faecal pellet (A) and nauplii production (B) of the F1 generation of Pseudodiaptomus annandalei as a function of Cu treatment. Data are visualized as mean + 1 SE. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences among control and Cu (Duncan Posthoc tests).

F2 – F6 generations

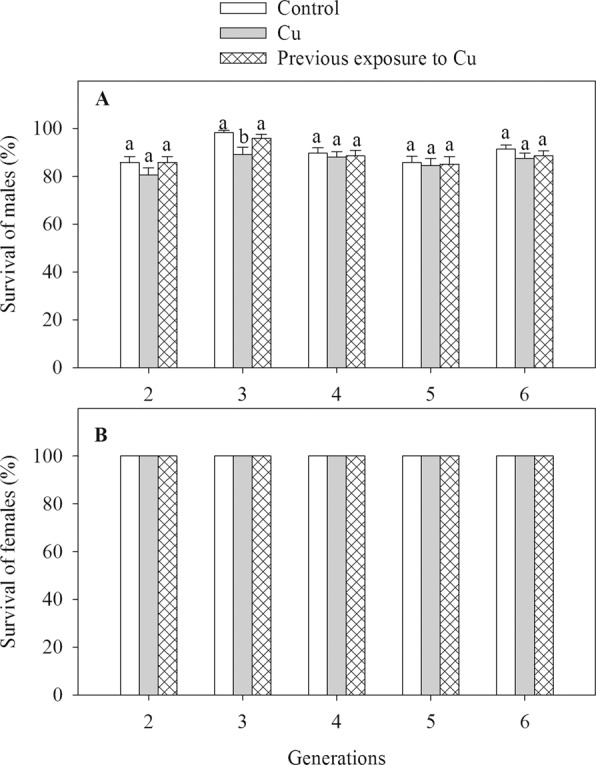

Overall, Cu exposure reduced male survival compared to the control (main effect of Cu, F2, 60 = 5.61, P = 0.006, Fig. 3A), but this pattern was only significant for F3 generation while there was no statistical difference in survival between control and Cu treatments in F2, F4, F5, and F6 generations (Cu × Generation, F8, 60 = 2.16, P = 0.043). Further, survival did not differ between the control and pCu treatment. Across all Cu treatments, male survival did not differ among generations (Generation, F4, 60 = 1.52, P = 0.21). For females, no mortality was observed in any of the generations (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Survival of males (A) and females (B) of Pseudodiaptomus annandalei F2–F6 generations as a function of Cu treatment. Data are visualized as mean + 1 SE. Different letters above the bars of the same generation indicate significant differences among control, Cu and pCu treatment (Duncan Posthoc tests).

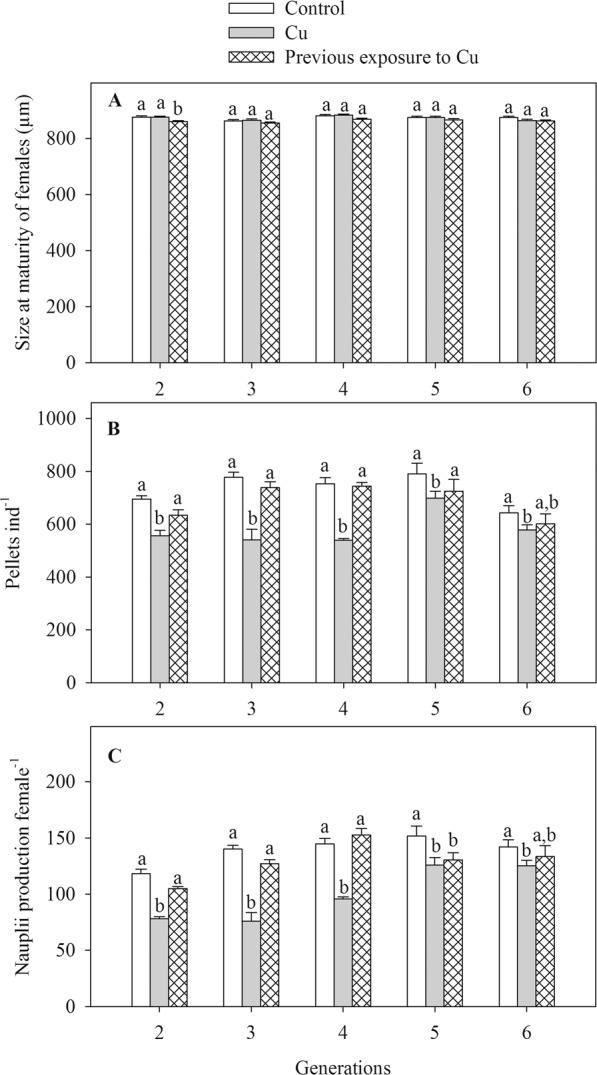

Female size was slightly reduced (~1%) in pCu treatment of F2 generation (Table 1, Fig. 4A). There was no effect of Cu or pCu on the size at maturity of females in F3-F6 generations. While there was a significant effect of generation on the size at maturity of females, the difference was small (~1%), and there was no clear trend of the changes in female size (Table 1, Fig. 4A). There was no interaction between Cu and generation on female size (Table 1).

Table 1.

The results of general linear models testing for the effects of Cu exposure on the size at maturity of females, faecal pellet and nauplii production of Pseudodiaptomus annandalei from F2 to F6 generations. Significant P values are indicated in bold.

| Effects | Size at maturity of females | Faecal pellet production | Nauplii production | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df1, df2 | F | P | df1, df2 | F | P | df1, df2 | F | P | |

| Cu | 2, 60 | 10.29 | <0.001 | 2, 60 | 40.21 | <0.001 | 2, 60 | 63.21 | <0.001 |

| Generation | 4, 60 | 6.05 | <0.001 | 4, 60 | 10.82 | <0.001 | 4, 60 | 21.17 | <0.001 |

| Cu × Generation | 8, 60 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 8, 60 | 3.21 | 0.004 | 8, 60 | 5.28 | <0.001 |

Figure 4.

Size at maturity of females (A), faecal pellet (B) and nauplii production (C) of Pseudodiaptomus annandalei F2-F6 generations as a function of Cu treatment. Data are visualized as mean + 1 SE. Different letters above the bars of the same generation indicate significant differences among control, Cu and pCu treatment (Duncan Posthoc tests).

Faecal pellet production was lower in the Cu treatment than in control, and this difference was more pronounced in F2-F4 generations, generating a main effect of Cu and the interaction of Cu × Generation (Table 1, Fig. 4B). In F2-F6 generations, faecal pellet production of pCu treatment was not statistically different from the control (Duncan Posthoc test, all P-values > 0.10). In F2-F4 generations, faecal pellet production of pCu copepods was higher than that of Cu-exposed copepods. Across Cu treatments, faecal pellet production varied from 10–20% among generations (Table 1).

Cu treatment and generations interacted to affect reproduction (Fig. 4C). From F2 to F3 generations, nauplii production was 34–46% lower in Cu-exposed females than in control females. Nauplii production of Cu-exposed females increased by 22 and 60% in F4 and F5 generations, respectively, compared to the F2 generation (Duncan Posthoc test, all P-values < 0.001). Nauplii production of F6 generation remained at the same level as in the F5 generation (Duncan Posthoc test, P-value > 0.05); both were about 83–88% compared to the nauplii production of control females. For the nauplii production of pCu females, it recovered to the control level in F2-F4, but it was as low as the Cu-exposed females in F5 and F6 generations.

Nauplii production covaried positively with fecal pellet production (F1, 509 = 643.84, P < 0.001, linear regression equation: Nauplii = 0.16 × faecals + 1.89, R2 = 0.57).

F7 generation

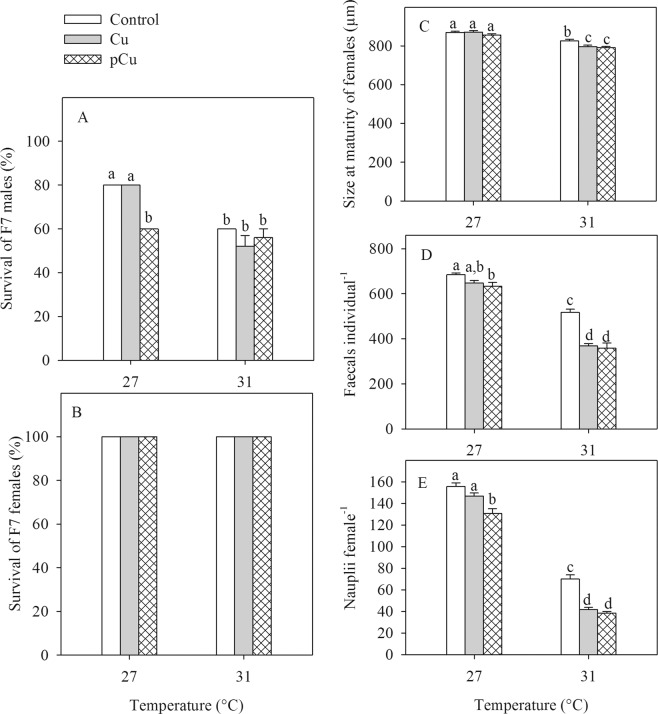

For males, there was no difference in survival between control and Cu treatments at 27 °C, both had higher survival than in all other treatments (main effect of Cu). In the control and Cu treatment, the survival was considerably lower at 31 °C than at 27 °C (main effect of Temperature, F1, 24 = 67.60, P < 0.001) while temperature did not alter copepod survival in pCu, generating the Cu × Temperature interaction (F2, 24 = 11.2, P < 0.001, Fig. 5A). The survival of females was 100% in all treatments (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Survival of males (A) and females (B), faecal pellet (C) and nauplii production (D) of Pseudodiaptomus annandalei F7 generation as a function of Cu and temperature treatments. Data are visualized as mean + 1 SE. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences among treatments (Duncan Posthoc tests).

Size at maturity of females was reduced by 2 and 3% in Cu and pCu, respectively (main effect of Cu, Table 2, Fig. 5C). Across all three Cu treatments, size at maturity was 7% smaller at 31 °C compared to 27 °C (main effects of Temperature, Table 2, Fig. 5C). Generally, faecal pellet and nauplii productions were approximately 15 and 17%, and 17 and 25% lower in Cu and pCu treatments, respectively, compared to the control (main effects of Cu, Table 2, Fig. 5D,E). Across all Cu treatments, faecal pellet and nauplii production decreased by 37 and 65%, respectively, at 31 °C compared to 27 °C (main effect of temperature, Table 2, Fig. 5D,E). The Cu-induced reduction in faecal pellet and nauplii production was stronger at 31 °C than at 27 °C (interactions of Cu × Temperature, Table 2, Fig. 5E).

Table 2.

The results of general linear models testing for the effects of Cu exposure and temperature on the size at maturity of females, faecal pellet and nauplii production of Pseudodiaptomus annandalei of the F7 generation. Significant P values are indicated in bold.

| Effects | Size at maturity of females | Pellet production | Nauplii production | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df1, df2 | F | P | df1, df2 | F | P | df1, df2 | F | P | |

| Cu | 2, 24 | 5.89 | 0.008 | 2, 24 | 30.23 | <0.001 | 2, 24 | 40.92 | <0.001 |

| Temperature | 1, 24 | 109.49 | <0.001 | 1, 24 | 400.81 | <0.001 | 1, 24 | 1321.0 | <0.001 |

| Cu × Temperature | 2, 24 | 2.83 | 0.079 | 2, 24 | 9.29 | 0.0010 | 2, 24 | 4.89 | 0.016 |

Discussion

Copper is known to be highly toxic at elevated concentrations to marine organisms such as amphipods27, corals28, gastropods29, and worms30. In the present study, exposure to the ecologically relevant concentration of Cu did not affect survival and faecal pellet production but strongly reduced nauplii production. Nauplii production is a highly sensitive indicator of Cu toxicity in copepods31. We did not observe mortality of Cu-exposed copepods in the F1 generation, which is in agreement with the result of the range finding test (Supplementary Information S1). Cu exposure concentration of 15 µg L−1 is approximately 20 and 70 times lower than the reported 48h-LC50 of 310 µg Cu L−1 for Tigriopus fulvus31 and 48h-LC50 of 1024 µg Cu L−1 for T. japonicus32, respectively. Biandolino et al.31 showed that the number of nauplii per brood of T. fulvus was not affected by exposure to Cu concentrations of 15–60 µg L−1, suggesting that Cu did not affect the embryonic development and hatching success. In this study, nauplii production of P. annandalei was lower in the Cu treatment compared to the control, which may be the result of a higher number of aborted egg sacs and a lower number of broods produced per female in Cu-exposed copepods. In support, we found in a companion study that exposure to 15 µg Cu L−1 resulted in a four-time increase in the number of aborted egg sacs of P. annandalei compared to the control treatment (Doan X.N. Pham, Q.H., and Dinh K.V., in prep.). Other copepod species such as T. fulvus also shows a higher number of aborted egg sacs and a lower number of broods in Cu-exposed females31. Importantly, a lower nauplii production was observed while the faecal pellet production (a proxy for grazing rate10,25,33) was similar between Cu-exposed individuals and the control, indicating a higher energy expenditure on somatic maintenance and other physiological responses to deal with Cu. Exposure to Cu may trigger upregulation of metallothioneins34, cytochrome P450, heat shock proteins, ferritin, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and glutathione S-transferase (GST). These play a role in xenobiotic metabolism, detoxification, antioxidant defense or stress response of marine copepods, such as T. japonicus35,36 and other marine species, such as Mytilus coruscus37.

While there was no lethal effect of Cu on F1 and on females of F2-F6 generations, males of F3 had lower survival in the Cu treatment, indicating a cumulative impact of Cu over generations like the cumulative effect of Cd on copepod T. japonicus11. This result is also in agreement with a generally higher contaminant sensitivity of males compared to females (no mortality observed for females). A higher contaminant sensitivity of males is common in copepod species38–40, which may be explained by the faster contaminant elimination in females via transfer to their eggs11,40–42.

As for survival, the reduced pellet production in F2-F4, but not in F1, may be a result of the accumulative effect of Cu exposure over generations. The lower grazing rate of marine copepods as a result of contaminant exposure has previously been observed33,43,44. The lower faecal pellet production suggests a lower energy intake, thereby less energy will be available for maintenance and reproduction. This may be further intensified by the metal-inhibited food digestion through depressing the activity of digestive enzymes, such as carbonxypeptidase B and chymotrypsin-like proteinase to break down ingested proteins from prey into amino acids, materials for the cellular metabolism11. Indeed, Cu-exposed females had a lower nauplii production. A positive correlation between faecal pellet and nauplii production was observed, which is similar to the finding in the copepod Acartia tonsa exposed to pyrene10, and this further supports our prediction of the metal-induced reduction in nauplii production mediated by grazing.

In our study, we found two important patterns of phenotypic plasticity and development of adaptation to Cu: (i) the transgenerational plasticity of F2-F4 in response to Cu exposure, and (ii) the development of adaptation to Cu in F5 and F6 generations. The F2-F4 generations of P. annandalei showed transgenerational plasticity in response to Cu exposure. Indeed, faecal pellet and nauplii production were lower in Cu-exposed copepods, but recovered in pCu-exposed copepods (no statistical difference between these two treatments), an indication of phenotypic plasticity7,45,46. Importantly, we found strong evidence of the development of adaptation to Cu of P. annandalei in F5 generation. The nauplii production of Cu-exposed females increased substantially compared to F2-F4 generations. Furthermore, nauplii production of pCu-exposed females did not return to the control level, and did not differ from the nauplii production of Cu-exposed females. Patterns of F5 generation were confirmed in the F6 generation. These results are in agreement with the prediction that the development of adaptation to contaminants (e.g. road salt - NaCl) in zooplankton species, such as Daphnia pulex, occurs within 5–10 generations. The cost of Cu adaptation was revealed when offspring from exposed parents was returned to the control, their nauplii production was not recovered like in F2-F4 generations. Interestingly, faecal pellet production of pCu-females was as high as that of the control, but their nauplii production was lower, indicating an energetic cost of adaptation.

It has been generally hypothesized that adaptation to contaminants may reduce the capacity of organisms to deal with climatic stressors, and vice versa (reviewed by Moe et al.17). Our study, using an evolutionary experiment, revealed that the development of Cu adaptation consistently resulted in stronger reductions in faecal pellet and nauplii production in P. annandalei under elevated temperature. Indeed, at 27 °C nauplii production was only reduced by 6% and 16% in Cu and pCu, respectively, yet at 31 °C it was reduced by 40% and 45% compared to the control. A similar pattern was observed for faecal pellet production with 5% and 7% reductions in Cu and pCu at 27 °C and 29% and 31% reduction at 31 °C compared to the control treatments at the respective temperatures. Nauplii production is a key trait for population growth. Our result provides strong empirical evidence for the “contaminant-induced climate change sensitivity” hypothesis (TICS)17,23. Metal contaminations are widespread in the coastal regions4,5 and are expected to become more severe in the near future from the rapid industrialization and urbanization6. Metal pollutions may cause higher vulnerability of marine species to environmental changes such as temperature (this study), ocean acidification47 and hypoxia48,49.

We also found a general and important pattern of the negative effect of temperature extremes alone on the performance of P. annandalei. Specifically, exposure to 31 °C resulted in lower survival (males), smaller size at maturity of females, lower faecal pellet and nauplii production. Lower male survival indicates that the temperature of 31 °C itself was lethal for P. annandalei. Such extreme temperatures are often observed in the shallow water in the tropical coastal regions of the South China Sea25 and are predicted to increase in frequency, duration, and severity in the coming years50. The temperature-induced reduction in size at maturity is a universal pattern that has been observed in various marine species from phytoplankton to fish51–56. The smaller size at maturity of female copepods typically show a lower grazing rate and fecundity53,57. Indeed, lower faecal pellet and nauplii production were observed at 31 °C than at 27 °C

Environmental pollution is a serious issue in tropical regions, particularly in the South China Sea1,2,5,6. Our study clearly shows that tropical zooplankton species can evolve in both transgenerational plasticity and development of metal adaptation as adaptive responses to exposure to ecologically relevant concentration of Cu. More generally, transgenerational plasticity and evolution of adaptations may occur widespread in nature as species have to cope with long-term changes in environmental factors such as the gradual increase in temperature58,59 and ocean acidification60,61. We revealed that the evolution of metal adaptation comes at the cost of reducing the capacity to deal with additional stressors; here we examined elevated temperature. This is important as increasing temperature, especially from marine heatwaves in this region62 is predicted to seriously affect the structures, function, and ecological services of the coastal ecosystems63. Detangling the transgenerational plasticity and evolution of adaptations to one stressor (Cu) and the associated costs would be the point of departure for tackling more complex issues on how marine species may persist, thrive or collapse under multiple-stressor conditions64.

Finally, our study showed that the negative effects of Cu on the survival, grazing, and reproductive success of P. annandalei, a key coastal zooplankton species, was found at Cu concentrations 10 times lower than the safety level of the current Vietnamese regulations65. While the impacts of widespread contaminants, such as metals4–6, on coastal species of this region are relatively unknown and poorly studied, newly emerging pollutants, such as plastics, arise rapidly2,66. The South China Sea is identified to be particularly vulnerable to climate change15, and climate change may further interact with contaminants to exacerbate the combined impact17,67. Altogether, it challenges efforts of biodiversity protection and management in one of the most biologically diverse and productive ecosystems on Earth, where substantial biodiversity loss has been documented6,68,69.

Materials and methods

Study species

The calanoid copepod Pseudodiaptomus annandalei distributes abundantly in tropical coastal ecosystems in the South China Sea region26,70. They are important grazers on small plankton71 and prey for fish larvae and juveniles26. The development time of P. annandalei lasts from 9 to 11 days at a temperature range of 25–34 °C15,72. On average, a female produces 0.8 clutches per day (9 clutches or 18 egg sacs in 11 days72. Each female can carry two egg sacs at a time, and each egg sac contains 4–10 eggs72. More than 90% of the eggs hatch into nauplii within 24 h at a temperature range of 28–30 °C24.

Adult copepod P. annandalei (approximately 2,000 individuals) were collected from Cam Ranh Bay in October 2017. They were transferred to the Laboratory of Live Feed in Aquaculture, The National Centre, where they were cultured in two tanks (200 L) at 27 °C and salinity of 20 ppt with ambient light and photoperiod (12 h light: 12 h dark cycle). The culture density was not controlled but varied between 150–300 individuals L−1, giving a total of 30,000–50,000 individuals per tank, which is approximately 30–50 times higher than the recommended culture density of copepods to maintain genetic diversity7,73. They were fed ad libitum on the microalga Thalassiosira pseudonana. To examine the performance of the F0 generation, copepods were collected randomly from the two tanks and mixed. Five groups of 5 males and 5 egg-carrying females (F0) were used to measure faecal pellet and nauplii production for 7 days. The average fecundity and the feacal pellet production of F0 were 21 ± 6 nauplii female−1 day−1, and 116 ± 15 pellets individual−1 day−1 (mean ± SD, n = 5).

Microalgal culture

The diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana was cultivated in quartz glass bottles (volume = 3 L) in sterilized seawater at salinity 24 ppt enriched with f/2 media74. The cultivation system was placed in an air-conditioned room controlled at 25 ± 1 °C and continuous light. When the cultures reached a density of 12–16 million cells mL−1, algae were harvested to feed copepods. The harvested microalgae were then diluted by clean seawater to the designated food concentration of approximately 800 µg C L−1 for the copepods.

Range finding tests

Prior to the evolutionary experiment, P. annandalei were exposed to one of five Cu2+ (hereafter Cu) concentrations: 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 and 120 µg Cu L−1 for 24 h. The survival, faecal pellet and nauplii production were quantified. Males had lower survival at Cu concentrations of 60–120 µg Cu L−1 (Fig. S1A, Supplementary Information S1). Survival of females was 100% in all Cu concentrations (Fig. S1B, Supplementary Information S1). The lowest Cu concentrations which resulted in reductions of faecal pellet and nauplli production were 15 and 30 µg Cu L−1, respectively (Fig. S1C,D, Supplementary Information S1). We selected an exposure concentration of 15 µg L−1 for the evolutionary experiment as this was the lowest concentration, which caused a significant negative effect on P. annandalei (i.e., the LOEC). This is ecologically relevant as the Cu concentrations >60 µg L−1 have recently reported for Vietnamese coastal water5, and approximately an order of magnitude below the safety level based on the National Regulations for Marine and coastal water quality (QCVN-10-MT-2015-BTNMT65).

To test whether the exposure concentration of Cu (15 µg Cu L−1) affect T. pseudonana, algae (180,000–200,000 cells mL−1) were exposed to either control (i.e., no Cu added) or Cu treatment (15 µg Cu L−1; five replicates per treatment) for 24 h. The initial and final algal densities were estimated by counting the number of cells in 1 mL-Lugol fixed samples. The final density of T. pseudonana were 184,000 ± 4,000 and 172,000 ± 4,899 cell mL−1 and did not statistically differ between Cu and the control treatment (ANOVA F1, 8 = 3.6, P = 0.09).

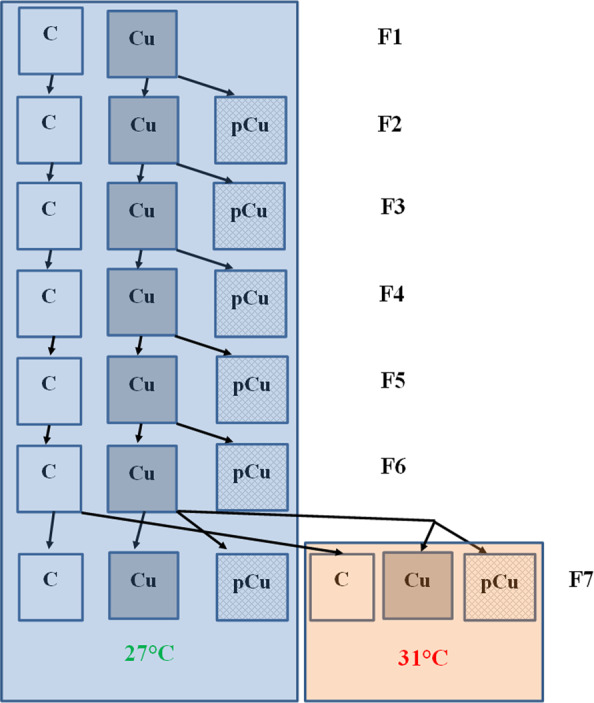

Experimental design and setup

To test the how copepods may evolve in transgenerational plasticity and development of tolerance to metals (hypothesis 1), we exposed P. annandalei to Cu (0 vs 15 µg L−1) and tracked the changes in four key fitness-related traits: survival, size at maturity, grazing (faecal pellet production) and reproductive success (nauplii production). All parameters were determined in each generation until the development of Cu adaptation revealed by an improved performance (i.e., increased survival, faecal pellet and nauplii production) of copepods in Cu treatment, and that the performance of pCu copepods did not differ from those in the Cu treatment. The evolution of Cu adaptation appeared in F5 generation, which was then confirmed in F6 generation. From F2 to F6, the Cu treatment was split into two treatments: one group was continuously exposed to the same Cu concentration (15 µg L−1; Cu treatment) as in the previous generation(s), and the other group was returned to control conditions (i.e., Cu-free seawater; pCu treatment)7 (Fig. 1). This experimental design allows detangling whether, and when, the response of copepods were a result of phenotypic plasticity or the development of metal adaptation7. To further test whether the increased tolerance to metals may come at the cost of reducing the tolerance to another stressor (hypothesis 2), we used offspring produced by the F6 generation in an experimental setting crossing three Cu treatments (0, Cu and pCu) and two temperatures (27 and 31 °C) (Fig. 1). The later temperature simulated a 4 °C increase in mean temperature by 2100 due to global warming, scenario RCP 8.3 – “business as usual”75, and has often been recorded in the coastal water of the South China Sea25.

Figure 1.

Experimental design diagram for testing the transgenerational plasticity and evolution of Cu tolerance of the tropical copepod Pseudodiaptomus annandalei. Cu: copper treatment: copepods were directly exposed to Cu; pCu: Cu pre-exposure treatment: offspring from Cu-exposed parents were returned to the control condition. F1-F7 refers to generations 1 to 7, respectively.

To prepare the exposure solution, CuSO4*5H2O (purity >99%, Merck, Germany) was dissolved in MQ-water. The exposure solution of 15 µg Cu L−1 was obtained by diluting the stock solution with clean seawater (20 ppt salinity).

To start the experiment, 200 females (F0) carrying two egg sacs were collected from the culture, they were placed in a 5-L glass bottle at room temperature of 27 °C and fed ad libitum with T. pseudonana. All nauplii were collected after 30h15 and ca. 150 nauplii were randomly assigned to each of 10 1-L bottles (five control and five Cu bottles) to start the F1 generation. The exposure solutions and algal food were renewed daily. When copepods developed into adults, three steps were performed:

-

(i)

Five males and five females carrying two egg sacs were collected from each of the experimental bottles and transferred to another 1-L bottle of the same treatment to quantify the faecal pellet and nauplii production for 7 days. Each treatment had five replicates. Faecal pellets and nauplii were daily collected by filtering the water content in each bottle through a filter (mesh size = 30 μm). The content was poured into a plastic Petri dish, carefully rinsed and fixed in Lugol (4% final concentration). The number of faecal pellets and nauplii was counted under a microscope (SZ40, Olympus, Japan). The faecal pellet production was the cumulated faecal pellets produced by an individual over 7 days of the observation period. Likewise, the nauplii production was as the cumulated nauplii female−1 in 7 days. We checked mortality daily while refreshing the medium.

-

(ii)

Ten females carrying two egg sacs were collected from each of the five 1-L control bottles and two groups of 10 females carrying two egg sacs were collected from each of five Cu-treatment bottles to start five control, five Cu, and five pCu bottles, respectively. All females produced nauplii for 30 h, then ~150 nauplii from each bottle were used to start the F2 generation (5 controls, 5 Cu and 5 pCu treatments). Other experimental conditions (food, temperature, salinity) were similar to the F1 generation. F3-F6 generations were started in the same way. For the F7 generation, each Cu treatment (control, Cu and pCu) was crossed with one of two temperatures (27 or 31 °C), resulting 6 treatments × 5 replicates = 30 experimental units (1-L bottles).

-

(iii)

After producing nauplii for 30 h, 10 females from each group in step ii were fixed in Lugol (final concentration of 4%) and the prosome length (µm) was measured as the size at maturity. The average size at maturity of females from each 1-L experimental bottle was used for statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses

One-way ANOVAs were used to test for the effects of Cu exposure on survival, size of females at maturity, faecal pellet and nauplii production of the F1 generation. For F2-F6 generations, we ran general linear models (GLMs) to test for the effects of Cu and pCu on the survival, size at maturity of females, faecal pellet and nauplii production across five generations. In these models, Cu treatment and generation were included as fixed factors. For all GLMs, we tested the assumption of normality of the error distributions with Shapiro-Wilk tests and the homogeneity of variances with Levene’s tests76. Survival, size at maturity of F7 females were were log(x + 1)-transformed to meet GLM model assumptions77,78. Following the ANOVAs and GLMs, we used Duncan posthoc tests for multiple comparisons, particularly among control, Cu and pCu treatmemts. Statistical differences were considered significant if P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were done in Statistica 12 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, United States). Data are presented in the figures as the means + SEs.

Data deposition

Data for this study are available at the Dryad Digital Repository when the manuscript is accepted for publication.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the grant B2019-TSN-562-08, Program 562, to Khuong Van Dinh. We thank Hanoi Forum HNQT/QL/01.18 for supporting the article publication fee.

Author contributions

K.V.D., H.T.D., H.S. and K.N.T. designed the experiment; H.T.D. and H.T.P. conducted the experiment and collected data. K.V.D. performed statistical analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript with assistance from H.T.D. All authors contributed to the later version of the manuscript; all authors read and approved the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Khuong V. Dinh, Email: khuong.dinh@wsu.edu

Kiem N. Truong, Email: kiemtn@vnu.edu.vn

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-67096-1.

References

- 1.Halpern BS, et al. A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science. 2008;319:948–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1149345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jambeck JR, et al. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science. 2015;347:768–771. doi: 10.1126/science.1260352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu Y, et al. Major threats of pollution and climate change to global coastal ecosystems and enhanced management for sustainability. Environ. Pollut. 2018;239:670–680. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen XV, Tran MH, Le TD, Papenbrock J. An assessment of heavy metal contamination on the surface sediment of seagrass beds at the Khanh Hoa Coast, Vietnam. B. Environ. Contam. Tox. 2017;99:728–734. doi: 10.1007/s00128-017-2191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le XS, Nguyen VB. Assessment of heavy metal concentration (copper, lead and zinc) in the seawater environment in typical coastal island communes. Vietnam Environment Administration Magazine - Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Vietnam. 2018;III:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dinh KV. Vietnam’s fish kill remains unexamined. Science. 2019;365:333–333. doi: 10.1126/science.aay6007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colin SP, Dam HG. Testing for resistance of pelagic marine copepods to a toxic dinoflagellate. Evol. Ecol. 2005;18:355–377. doi: 10.1007/s10682-004-2369-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klerks PL, Weis JS. Genetic adaptation to heavy metals in aquatic organisms: A review. Environ. Pollut. 1987;45:173–205. doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(87)90057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dam HG. Evolutionary adaptation of marine zooplankton to global change. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2013;5:349–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-121211-172229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krause KE, Dinh KV, Nielsen TG. Increased tolerance to oil exposure by the cosmopolitan marine copepod Acartia tonsa. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;607–608:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang MH, Zhang C, Lee JS. Quantitative shotgun proteomics associates molecular-level cadmium toxicity responses with compromised growth and reproduction in a marine copepod under multigenerational exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:1612–1623. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran TT, Janssens L, Dinh KV, Stoks R. Transgenerational interactions between pesticide exposure and warming in a vector mosquito. Evol. Appl. 2018;11:906–917. doi: 10.1111/eva.12605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dao T-S, Vo T-M-C, Wiegand C, Bui B-T, Dinh KV. Transgenerational effects of cyanobacterial toxins on a tropical micro-crustacean Daphnia lumholtzi across three generations. Environ. Pollut. 2018;243:791–799. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donelson JM, Munday PL, McCormick MI, Pitcher CR. Rapid transgenerational acclimation of a tropical reef fish to climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012;2:30–32. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doan XN, et al. Extreme temperature impairs growth and productivity in a common tropical marine copepod. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:4550. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40996-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly MW, Pankey MS, DeBiasse MB, Plachetzki DC. Adaptation to heat stress reduces phenotypic and transcriptional plasticity in a marine copepod. Funct. Ecol. 2017;31:398–406. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moe SJ, et al. Combined and interactive effects of global climate change and toxicants on populations and communities. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013;32:49–61. doi: 10.1002/etc.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinh Van K, et al. Susceptibility to a metal under global warming is shaped by thermal adaptation along a latitudinal gradient. Glob. Change Biol. 2013;19:2625–2633. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stoks R, Debecker S, Dinh KV, Janssens L. Integrating ecology and evolution in aquatic toxicology: insights from damselflies. Freshw. Sci. 2015;34:1032–1039. doi: 10.1086/682571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janssens L, Dinh KV, Debecker S, Bervoets L, Stoks R. Local adaptation and the potential effects of a contaminant on predator avoidance and antipredator responses under global warming: a space-for-time substitution approach. Evol. Appl. 2014;7:421–430. doi: 10.1111/eva.12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vera-Chang MN, et al. Transgenerational hypocortisolism and behavioral disruption are induced by the antidepressant fluoxetine in male zebrafish Danio rerio. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E12435–E12442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811695115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dinh Van K, Janssens L, Debecker S, Stoks R. Temperature- and latitude-specific individual growth rates shape the vulnerability of damselfly larvae to a widespread pesticide. J. Appl. Ecol. 2014;51:919–928. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noyes PD, Lema SC. Forecasting the impacts of chemical pollution and climate change interactions on the health of wildlife. Curr. Zool. 2015;61:669–689. doi: 10.1093/czoolo/61.4.669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grønning JB, Doan NX, Dinh TN, Dinh KV, Nielsen TG. Ecology of Pseudodiaptomus annandalei in tropical aquaculture ponds with emphasis on the limitation of production. J. Plankton Res. 2019;41:741–758. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbz053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doan NX, et al. Temperature- and sex-specific grazing rate of a tropical copepod Pseudodiaptomus annandalei to food availability: implications for live feed in aquaculture. Aquacult. Res. 2018;49:3864–3873. doi: 10.1111/are.13854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chew LL, Chong VC, Tanaka K, Sasekumar A. Phytoplankton fuel the energy flow from zooplankton to small nekton in turbid mangrove waters. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012;469:7–24. doi: 10.3354/meps09997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prato E, Parlapiano I, Biandolino F. Sublethal effects of copper on some biological traits of the amphipod Gammarus aequicauda reared under laboratory conditions. Chemosphere. 2013;93:1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwarz JA, Mitchelmore CL, Jones R, O’Dea A, Seymour S. Exposure to copper induces oxidative and stress responses and DNA damage in the coral Montastraea franksi. Comp. Biochem. Phys. C Toxicol. & Pharmacol. 2013;157:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holan JR, King CK, Sfiligoj BJ, Davis AR. Toxicity of copper to three common subantarctic marine gastropods. Ecotox. and Environ. Safe. 2017;136:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caldwell GS, Lewis C, Pickavance G, Taylor RL, Bentley MG. Exposure to copper and a cytotoxic polyunsaturated aldehyde induces reproductive failure in the marine polychaete Nereis virens (Sars) Aquat. Toxicol. 2011;104:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biandolino F, Parlapiano I, Faraponova O, Prato E. Effects of short- and long-term exposures to copper on lethal and reproductive endpoints of the harpacticoid copepod Tigriopus fulvus. Ecotox. and Environ. Safe. 2018;147:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwok KWH, Leung KMY. Toxicity of antifouling biocides to the intertidal harpacticoid copepod Tigriopus japonicus (Crustacea, Copepoda): Effects of temperature and salinity. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005;51:830–837. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dinh KV, Olsen MW, Altin D, Vismann B, Nielsen TG. Impact of temperature and pyrene exposure on the functional response of males and females of the copepod Calanus finmarchicus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;26:29327–29333. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-06078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amiard JC, Amiard-Triquet C, Barka S, Pellerin J. & Rainbow, P. S. Metallothioneins in aquatic invertebrates: Their role in metal detoxification and their use as biomarkers. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006;76:160–202. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ki JS, et al. Gene expression profiling of copper-induced responses in the intertidal copepod Tigriopus japonicus using a 6K oligochip microarray. Aquat. Toxicol. 2009;93:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim B-M, et al. Heavy metals induce oxidative stress and trigger oxidative stress-mediated heat shock protein (hsp) modulation in the intertidal copepod Tigriopus japonicus. Comp. Biochem. Phys. C Toxicol. & Pharmacol. 2014;166:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu K, et al. Effects of low concentrations copper on antioxidant responses, DNA damage and genotoxicity in thick shell mussel Mytilus coruscus. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2018;82:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dipinto LM, Coull BC, Chandler GT. Lethal and sublethal effects of the sediment-associated PCB aroclor 1254 on a meiobenthic copepod. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1993;12:1909–1918. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620121017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medina M, Barata C, Telfer R, Baird DJ. Age- and sex-related variation in sensitivity to the pyrethroid cypermethrin in the marine copepod Acartia tonsa Dana. Arch. Environ. Con. Tox. 2002;42:17–22. doi: 10.1007/s002440010286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kadiene EU, Bialais C, Ouddane B, Hwang JS, Souissi S. Differences in lethal response between male and female calanoid copepods and life cycle traits to cadmium toxicity. Ecotoxicology. 2017;26:1227–1239. doi: 10.1007/s10646-017-1848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McManus GB, Wyman KD, Peterson WT, Wurster CF. Factors affecting the elimination of PCBs in the marine copepod Acartia tonsa. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 1983;17:421–430. doi: 10.1016/0272-7714(83)90127-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toxværd K, Dinh KV, Henriksen O, Hjorth M, Nielsen T. Impact of pyrene exposure during overwintering of the Arctic copepod Calanus glacialis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:10328–10336. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b03327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koski M, Stedmon C, Trapp S. Ecological effects of scrubber water discharge on coastal plankton: Potential synergistic effects of contaminants reduce survival and feeding of the copepod Acartia tonsa. Mar. Environ. Res. 2017;129:374–385. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen BH, et al. Maternal polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) transfer and effects on offspring of copepods exposed to dispersed oil with and without oil droplets. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A Curr. Issues. 2017;80:881–894. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2017.1352190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Byrne M, Foo SA, Ross PM, Putnam HM. Limitations of cross- and multigenerational plasticity for marine invertebrates faced with global climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2020;26:80–102. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brander SM, Biales AD, Connon RE. The role of epigenomics in aquatic toxicology. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017;36:2565–2573. doi: 10.1002/etc.3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ivanina AV, Sokolova IM. Interactive effects of metal pollution and ocean acidification on physiology of marine organisms. Curr. Zool. 2015;61:653–668. doi: 10.1093/czoolo/61.4.653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blewett TA, Simon RA, Turko AJ, Wright PA. Copper alters hypoxia sensitivity and the behavioural emersion response in the amphibious fish Kryptolebias marmoratus. Aquat. Toxicol. 2017;189:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fitzgerald, J. A. et al. Sublethal exposure to copper supresses the ability to acclimate to hypoxia in a model fish species. Aquat. Toxicol. 217, 10.1016/j.aquatox.2019.105325 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Froehlich HE, Gentry RR, Halpern BS. Global change in marine aquaculture production potential under climate change. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018;2:1745–1750. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0669-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sommer U, Peter KH, Genitsaris S, Moustaka-Gouni M. Do marine phytoplankton follow Bergmann’s rule sensu lato? Biol. Rev. 2017;92:1011–1026. doi: 10.1111/brv.12266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daufresne M, Lengfellner K, Sommer U. Global warming benefits the small in aquatic ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12788–12793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902080106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horne CR, Hirst AG, Atkinson D, Neves A, Kiorboe T. A global synthesis of seasonal temperature-size responses in copepods. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2016;25:988–999. doi: 10.1111/geb.12460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pan YJ, et al. Effects of cold selective breeding on the body length, fatty acid content, and productivity of the tropical copepod Apocyclops royi (Cyclopoida, Copepoda) J. Plankton Res. 2017;39:994–1003. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbx041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gibbin EM, et al. Can multi-generational exposure to ocean warming and acidification lead to the adaptation of life history and physiology in a marine metazoan? J. Exp. Biol. 2017;220:551–563. doi: 10.1242/jeb.149989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheung WWL, et al. Shrinking of fishes exacerbates impacts of global ocean changes on marine ecosystems. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013;3:254–258. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiørboe T, Sabatini M. Scaling of fecundity, growth and development in marine planktonic copepods. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1995;120:285–298. doi: 10.3354/meps120285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Merilä J, Hendry AP. Climate change, adaptation, and phenotypic plasticity: the problem and the evidence. Evol. Appl. 2014;7:1–14. doi: 10.1111/eva.12137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Donelson JM, Salinas S, Munday PL, Shama LNS. Transgenerational plasticity and climate change experiments: Where do we go from here? Glob. Change Biol. 2018;24:13–34. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Calosi, P. et al. Adaptation and acclimatization to ocean acidification in marine ectotherms: an in situ transplant experiment with polychaetes at a shallow CO2 vent system. Philos. T. R. Soc. B368, 10.1098/rstb.2012.0444 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Lee, Y. H., Jeong, C. B., Wang, M. H., Hagiwara, A. & Lee, J. S. Transgenerational acclimation to changes in ocean acidification in marine invertebrates. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 153, 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111006 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Yao Y, Wang J, Yin J, Zou X. Marine heatwaves in China’s marginal seas and adjacent offshore waters: past, present, and future. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 2020;125:e2019JC015801. doi: 10.1029/2019JC015801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smale DA, et al. Marine heatwaves threaten global biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019;9:306–312. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0412-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crain CM, Kroeker K, Halpern BS. Interactive and cumulative effects of multiple human stressors in marine systems. Ecol. Lett. 2008;11:1304–1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vietnamese Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. (ed Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment) 10 (Hanoi, 2015).

- 66.Cai MG, et al. Lost but can’t be neglected: Huge quantities of small microplastics hide in the South China Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;633:1206–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Landis WG, et al. Global climate change and contaminants, a call to arms not yet heard? Integr. Environ. Assess. 2014;10:483–484. doi: 10.1002/ieam.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barlow J, et al. The future of hyperdiverse tropical ecosystems. Nature. 2018;559:517–526. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Worm B, et al. Impacts of biodiversity loss on ocean ecosystem services. Science. 2006;314:787–790. doi: 10.1126/science.1132294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hwang JS, et al. Patterns of zooplankton distribution along the marine, estuarine, and riverine portions of the Danshuei ecosystem in northern Taiwan. Zool. Stud. 2010;49:335–352. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dhanker R, Kumar R, Hwang JS. Predation by Pseudodiaptomus annandalei (Copepoda: Calanoida) on rotifer prey: Size selection, egg predation and effect of algal diet. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2012;414:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2012.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Golez MSN, Takahashi T, Ishimaru T, Ohno A. Post-embryonic development and reproduction of Pseudodiaptomus annandalei (Copepoda: Calanoida) Plankt. Biol. Ecol. 2004;51:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Colin SP, Dam HG. Latitudinal differentiation in the effects of the toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium spp. on the feeding and reproduction of populations of the copepod Acartia hudsonica. Harmful Algae. 2002;1:113–125. doi: 10.1016/S1568-9883(02)00007-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guillard RR, Ryther JH. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms: I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (Cleve) Gran. Can. J. Microbiol. 1962;8:229–&. doi: 10.1139/m62-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.IPCC. Climate change 2013: The physical science basis: Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- 76.Quinn, G. P. & Michael, K. J. Experimental design and data analysis for biologists. 537 (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- 77.Warton DI, Hui FKC. The arcsine is asinine: the analysis of proportions in ecology. Ecology. 2011;92:3–10. doi: 10.1890/10-0340.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dinh KV, et al. Delayed effects of chlorpyrifos across metamorphosis on dispersal-related traits in a poleward moving damselfly. Environ. Pollut. 2016;218:634–643. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.