Abstract

Organoids are a valuable three-dimensional (3D) model to study the differentiated functions of the human intestinal epithelium. They are a particularly powerful tool to measure epithelial transport processes in health and disease. Though biological assays such as organoid swelling and intraluminal pH measurements are well established, their underlying functional genomics are not well characterized. Here we combine genome-wide analysis of open chromatin by ATAC-Seq with transcriptome mapping by RNA-Seq to define the genomic signature of human intestinal organoids (HIOs). These data provide an important tool for investigating key physiological and biochemical processes in the intestinal epithelium. We next compared the transcriptome and open chromatin profiles of HIOs with equivalent data sets from the Caco2 colorectal carcinoma line, which is an important two-dimensional (2D) model of the intestinal epithelium. Our results define common features of the intestinal epithelium in HIO and Caco2 and further illustrate the cancer-associated program of the cell line. Generation of Caco2 cysts enabled interrogation of the molecular divergence of the 2D and 3D cultures. Overrepresented motif analysis of open chromatin peaks identified caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2) as a key activating transcription factor in HIO, but not in monolayer cultures of Caco2. However, the CDX2 motif becomes overrepresented in open chromatin from Caco2 cysts, reinforcing the importance of this factor in intestinal epithelial differentiation and function. Intersection of the HIO and Caco2 transcriptomes further showed functional overlap in pathways of ion transport and tight junction integrity, among others. These data contribute to understanding human intestinal organoid biology.

Keywords: functional genomics, gene expression, intestinal organoids, open chromatin

INTRODUCTION

Human colon organoids are three-dimensional (3D) cell culture models used to study the differentiation and function of the intestinal epithelium in vitro [reviewed in (8, 29)]. In comparison to 2D cell cultures, organoids have the advantages of multicellular complexity and tissue structure facilitating functional assays. Leucine-rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5)-positive stem cells were first identified through lineage-tracing and shown to give rise to all other cell types in the mouse small intestine (2). Subsequently, single LGR5+ stem cells alone were found to be sufficient for establishing intestinal organoids in vitro (41) in Matrigel (Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma extracellular matrix) (26) supplemented with the Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 and the Notch-agonist peptide Jagged. This protocol was later optimized to generate organoid cultures, both from human small intestine and from mouse and human colon (34, 40). In addition to primary human crypts as a source for LGR5+ stem cells, differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells into similar intestinal organoids has also been achieved (31, 43).

Intestinal organoids provide useful models to study many aspects of human intestinal disease including ulcerative colitis (15, 51), Crohn's disease (45), and colon cancer (56). Among their most extensive applications is the investigation of dysfunction of the intestinal epithelium in the common inherited disorder cystic fibrosis (CF). CF is caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, which encodes an anion channel that is pivotal to the normal functions of many epithelial tissues. In the apical membrane of the intestinal epithelium CFTR drives salt and water transport into the lumen of the gut, a process that can be readily modeled by organoid swelling assays (14). Intestinal organoids generated from patients with the most common CF pathogenic variant F508del, showed impaired swelling in response to forskolin activation of CFTR when compared with wild-type (WT) organoids. Moreover, repair of F508del by gene editing restored a normal swelling phenotype (42). Organoid swelling was also used as a benchmark readout for drug development for mutant CFTR correctors (3, 13), including testing of read-through agents to correct “stop” mutations (57) and small molecule screens in mouse intestinal organoids carrying the common CF variant G542X (32). Other translational applications of enterocyte-enriched intestinal organoids include assays of dietary lipid metabolism (25, 30).

Though widely accepted for their utility in physiological assays, to date, the functional genomics of intestinal organoids have not been investigated in detail. Although the transcriptome of intestinal organoids has been documented both in bulk cell populations by microarray (41) and by single cell RNA-Seq (21), the mechanisms underlying the coordinated regulation of organoid gene expression are currently not well established. Early single cell RNA-Seq analysis of mouse intestinal organoids suggested the presence of six major cell types (21), correlating closely with previous immunodetection of five cell types in the human intestinal epithelium, together with the additional transit amplifying cells (40). The cell-type markers used include alkaline phosphatase for mature enterocytes, mucin 2 (MUC2) for goblet cells, chromogranin A (ChgA) or synaptophysin for enteroendocrine cells, doublecortin like kinase 1 (DCLK1) for Tuft cells and lysozyme (Lysz) for Paneth cells, BMI-1 proto-oncogene, polycomb ring finger (BMI1) for transit amplifying cells. Of note the abundance of enterocytes was substantially higher in human compared with mouse organoids (49), though this may be an artifact of different analysis protocols. Overall, based on gene expression data the human intestinal organoids closely reflect human intestinal epithelium.

Our first goal was to generate comprehensive functional genomics data on wild-type (WT) human intestinal organoids (HIO) by integrating RNA-Seq data with genome-wide open chromatin analysis, to document the transcriptional network of HIOs. A second objective was to compare the organoid data to a well-studied cellular model of the intestinal epithelium that is commonly used to test CFTR function. Analysis of open chromatin is a powerful way to profile the distribution of cis-regulatory elements across the genome. The location of these sites mark active loci and key architectural features of the genome such as topological domain boundaries (TADs) that restrict the interaction of enhancers with nontarget genes outside a specific TAD (36). Moreover, bioinformatics pipelines can be used to predict the transcription factors (TFs) that bind within open chromatin peaks (24), thus revealing likely candidates in the transcriptional network coordinating the differentiation and function of a tissue or cell type. Here we investigate the open chromatin landscape of undifferentiated HIOs by using Omni Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin (ATAC)-Seq. Next, we intersect these data with the organoid transcriptome shown by RNA-Seq and thus identify key regulatory networks in the HIO model. Finally, we compare the HIO open chromatin profile to that of the human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line Caco2 (16), which is widely used to model colonic epithelium (35). This comparison, which includes Caco2 cells grown in monolayer and as 3D cysts, reveals many similarities between HIO and Caco2 cells, but also some key functional differences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line and human intestinal organoid culture.

Caco2 cells were purchased from ATCC (ATCC HTB-37) and routinely cultured as monolayers in DMEM (low glucose) with 10% FBS. For Caco2 cyst cultures, 2 × 104/ml Caco2 cells were resuspended in 50% Matrigel (Corning #356231) in culture media. Then 35 μL Matrigel droplets were placed in individual wells of a 24-well plate and grown in CMRL1066 media supplemented with 15% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine. 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 0.2 U/ml insulin, 10−10 M cholera toxin, and 25 ng/ml EGF. The protocol of Miyoshi and Stappenbeck (34) for colon organoid subculture and expansion was used with minor modifications. Tissue samples were obtained from the Department of Surgical Pathology at the Cleveland Clinic under Institutional Review Board protocol (17-1167). Adjacent normal intestinal crypts were harvested from surgical resections of patients with adenocarcinoma. Briefly, tissue was first rinsed in HBSS (Hanks’ buffered saline solution), and blotted to remove excess mucus. Colonic mucosal strips (~4) were cut from tissue, placed in 60 mm dishes, and minced with scissors such that they could pass through a 1 ml pipette tip. Tissue fragments were then suspended in a collagenase solution (2 mg/ml Type I collagenase and 50 mg/ml gentamicin in wash medium [DMEM F/12 containing 10% FBS, 1% Pen/Strep, and 1% L-glutamine)] and digested at 37°C until colonic crypts were liberated (~30–40 min). The crypts were then washed in wash medium, counted, and plated in 15 μl Matrigel to have ~5,000 crypts per Matrigel bead, in 24-well tissue culture plates. Intestinal stem cells were then cultured at 37°C in 50% L-WRN cell conditioned medium containing 10 μM Y-27632 and 500 nM A-83-01. To passage organoids, dissociation buffer (1 mM DTT, 0.5M EDTA in PBS) was added to break up Matrigel beads, following which organoids were trypsinized for 1 min at 37°C. Wash medium was added to neutralize trypsin, and organoids were washed twice and then plated in Matrigel and cultured with conditioned medium. Typically, organoids were passaged 1:3 every week. Fresh medium was added to wells every other day.

ATAC-Seq and data analysis.

Omni Assay for Transposase Accessible Chromatin and deep sequencing (Omni-ATAC-Seq) was performed on human intestinal organoid as described previously (7, 11, 46) with minor modifications. Technical replicates were performed on two different organoid donors. ATAC-Seq libraries were purified with Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter) with a sample to bead ratio of 1:1.2 and eluted in Buffer EB (Qiagen). High-quality ATAC-Seq libraries were confirmed by robust nucleosome repeat distributions on Tapestation (Agilent) analysis and sequenced (50 bp SE) on a HiSeq4000 instrument. Sequence reads were aligned to the hg19 genome. All ATAC-Seq data were analyzed using the ENCODE-DCC/atac-seq-pipeline (2019-JUL) and satisfied key quality control parameters. The pipeline peak set output parameter was set to irreproducible discovery rate (IDR) at a threshold of 0.1. Alignment files were filtered and Tn5 shifted, then imported into DiffBind (ver. 2.10.0) to identify statistically significant differential open regions. For peak overlap analysis of Omni-ATAC-Seq data, peaks from the different cell types were called individually, then extended to 500 bp. Peaks from Caco2 and HIO were merged to create a union peak set (10, 43). Then a Caco2/HIO unique peak set was generated by comparison with this union peak set. Motif enrichment graphs in Fig. 4, A and B, were generated as follows: the peak set was analyzed using the peak files with hg19 default parameters in Homer (v4.11, 10-24-2019) (24), the ranking of motifs were plotted against the –Log10 P value of the statistical signature of these motifs using ggplot2 (50) in R.

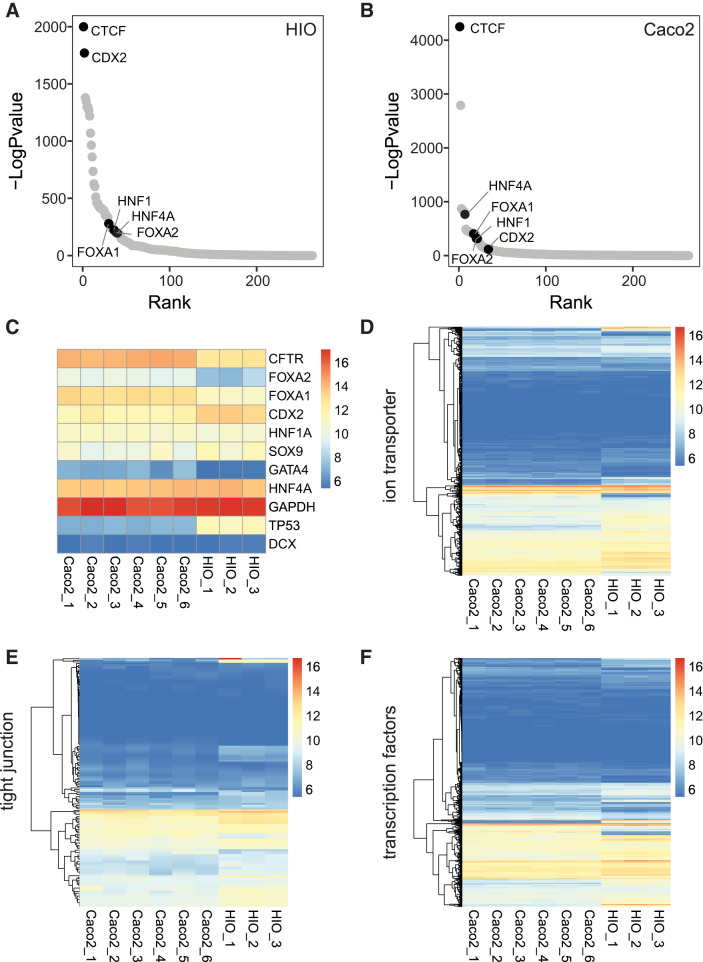

Fig. 4.

Open chromatin and gene expression profiling in human intestinal organoid (HIO) and Caco2 show signature features of intestinal epithelial cells and similarity of functional genomics between HIO and Caco2. Transcription factor motifs ranked by enrichment under global open chromatin peaks in HIO (A) and Caco2 (B). C: heatmap showing expression of key marker genes, including positive (GAPDH) and negative (DCX) controls. D–F: heatmaps showing expression of ion transporter family genes (GO:0006811, n = 1,730) (D); tight junction genes (GO:0070160, n = 156) (E); transcription factors (n = 1,639) (F).

RNA-Seq and data analysis.

RNA-Seq data were generated from organoids from three different donors (NL1609, NL1612, NL1615), two of which (NL1609, NL1615) were also used for the ATAC-Seq experiments. Briefly organoids grown in Matrigel were washed three times in PBS, and RNA was harvested using the Qiagen RNAeasy Mini kit (Qiagen #74104) with the supplied RLT buffer, according to manufacturer’s protocol. Directional cDNA libraries were made using the Illumina TruSeq RNA library kit and sequenced (100 bp PE) on an Illumina HiSeq2500 machine, according to standard Illumina protocols. Caco2 RNA-Seq data were from GSE130226. Paired sequencing reads were aligned to the hg38 transcriptome using STAR (ver. 2.7.0e_0320). Aligned files were imported into Featurecounts (ver. 1.6.1), which outputs raw counts for each feature and then imported into DESeq2 (ver. 1.22.2) with default statistical parameters to calculate the significant differential gene expression values. Volcano plots were made by EnhancedVolcano (6) (ver. 1.0.1). Heatmaps in Fig. 4 were generated using the R package pheatmap (27). Read count values for intrasample comparisons were normalized to transcript size (values used in Fig. 2). ATAC-Seq and RNA-Seq data are at GEO: GSE140458.

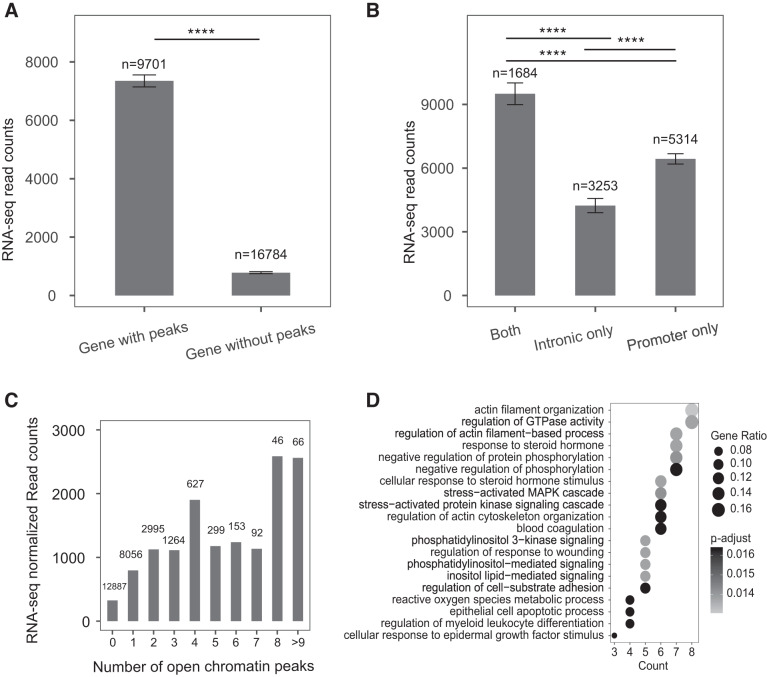

Fig. 2.

Human colon organoid gene expression and correlation with nearby chromatin accessibility. A, B: histogram of mean DESeq2 normalized RNA-Seq read counts for genes binned by their association with open chromatin peaks within 20 kb (A). ****P < 0.0001 by Welch modified two-sample t test. B: subgroups of genes with nearby open chromatin peaks in their promoters, introns, or both. ****P < 0.0001 by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. C: histogram of mean DESeq2 normalized RNA-Seq read counts normalized to transcript size for genes binned by number of associated open chromatin peaks. D: enriched gene ontology pathways for genes with nine or more open chromatin peaks nearby. Size and color of dots represent number of genes and significance of enrichment, respectively. Gene ratio is ratio of enriched genes compared with total number of genes.

Pathway and gene ontology analyses.

The package clusterProfiler (ver. 3.9) in R (ver. 3.5.2) was used (1, 33, 47, 53) to obtain gene ontology categories. The transcription factor gene list was obtained from (28).

Statistical analysis.

For comparing open chromatin peak signals, we used DiffBind. DiffBind statistics are built on DEseq2 and edgeR. To compare RNA-Seq read counts, P values were calculated and adjusted by DESeq2. For data in Fig. 2 we used statistical tests in baseR: Fig. 2A uses the Welch modified two-sample t test; Fig. 2B uses Tukey's multiple-comparisons test. To enrich pathways from gene lists, we used Benjamini and Hochberg adjusted P values using the enrichGO package. For motif enrichment from a set of open chromatin peaks, we used the Homer package statistics to calculate and adjust P values.

RESULTS

We performed Omni ATAC-Seq and RNA-Seq on human colon organoids and on Caco2 cells and cysts. Briefly, crypts were isolated from resected human colon tissue and plated into Matrigel in which they formed organoids within 7–10 days (Fig. 1A). The epithelial cell marker villin (VIL1) was used for organoid validation (Suppl. Fig S1; all supplemental material is available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11962731). The organoids were then isolated from Matrigel, disassociated to single cells, and lysed for the ATAC-Seq protocol. Organoid cultures from the same donors were used for RNA-Seq library preparation.

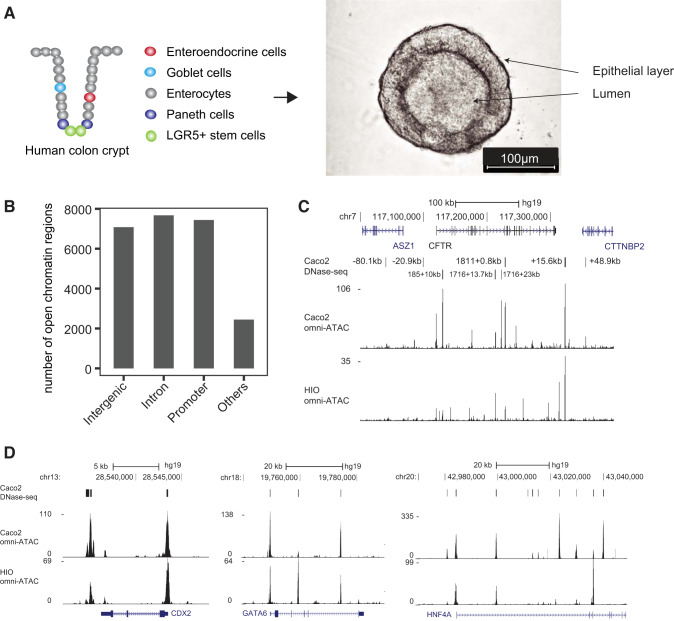

Fig. 1.

Human colon organoid generation and chromatin accessibility profiling. A: cartoon illustrating the study workflow and an example of mature human colon organoids. B: genomic distribution of the open chromatin regions profiled from ATAC-Seq of colon organoids. C: UCSC Genome Browser view of the open chromatin profile of HIO (top) and Caco2 (bottom) at the CFTR gene locus (chr7:117,000,000–117,400,000), peak files are combined DHS of previous DNase-Seq data. We used CF legacy nomenclature, DHS outside of the gene are named based on its distance to TSS, DHS inside the gene are named based on its cDNA location plus intronic distance. D: UCSC Genome Browser view of the open chromatin profile at the CDX2 gene locus (chr13:28,532,000–28,548,000), GATA6 (chr18:19,740,000–19,790,000), and HNF4A (chr20:42,970,000–43,049,000). DHS, DNase I hypersensitive sites; HIO, human intestinal organoid.

Open chromatin defines genes and pathways involved in intestinal function.

In total, 42,894 HIO ATAC-Seq peaks passed the IDR threshold of 0.1 and were used for subsequent analysis as high confidence peaks. After merging peaks that overlapped by more than one base pair, we used 24,635 peaks for further analyses. The distribution of these peaks (Fig. 1B) was consistent with our previous mapping of regions of open chromatin in multiple epithelial cell types by DNase-Seq (4, 5, 19), which showed many cis-regulatory elements (CREs) are located in intronic and intergenic sites. The distribution of the open chromatin peaks also demonstrated a ratio that is consistent with reported ATAC-Seq peak distributions for other tissue types (39). Our data show 28% of peaks are located within intronic regions and 25% within intergenic regions. We analyzed the distribution of ATAC-Seq peaks with respect to the nearest genes. Among HIO open chromatin peaks, 8,247 of all 24,635 genomic regions (33.48%) were located more than 20 kb away from a gene (Suppl. Fig. S2). For one locus, CFTR, we compared the open chromatin map generated here by ATAC-Seq with our previous extensive characterization by DNase-chip and DNase-Seq (37, 52, 55). Strong concordance in the location of peaks of open chromatin was observed between DNase-Seq and ATAC-Seq (Fig. 1C). Moreover, we observed robust open chromatin signals at the promoters of several intestinal lineage-defining genes including caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2) and also at other important TFs in the intestinal epithelium such as hepatocyte nuclear factor 4A (HNF4A) and GATA-binding protein 6 (GATA6) (Fig. 1D). A gene ontology process enrichment analysis of nearest genes to the high confidence peaks revealed pathways associated with general metabolic processes (Suppl. Fig. S3). Together, these results suggest the open chromatin regions identified by ATAC-Seq in human intestinal organoids are enriched for CREs of genes that are important in intestinal epithelial function.

Intestinal gene expression is associated with specific regions of open chromatin.

Since regions of open chromatin are associated with active genes and their CREs, we hypothesized that the likelihood of expressed genes being located close to ATAC-Seq peaks (within 20 kb) would be greater than that of transcriptionally inactive genes. To test this, we stratified genes based on the presence of associated open chromatin and observed that genes with adjacent ATAC-Seq peaks were expressed at a higher level (Fig. 2A). Next, we asked if the distribution of open chromatin relative to gene bodies had an impact on gene activity. All genes were binned based on the presence of promoter peaks only, peaks solely within introns, or peaks in both locations. Genes with peaks of open chromatin within 20 kb show significantly higher expression that those lacking these features (Fig. 2A). The expression of genes with open chromatin only at the promoter is significantly higher than those exhibiting intron peaks of open chromatin only, but genes with both open chromatin at the promoter and within introns are most highly expressed (Fig. 2B). These data are consistent with our previous observations in other epithelial cell types (19). Gene expression values measured by RNA-Seq read counts were then binned according to the number of associated ATAC-Seq peaks (1–8 or 9 and more) (Fig. 2C, Suppl. Table S1). Though there was no direct correlation between gene expression levels (normalized to transcript length) and number of peaks of open chromatin, a trend was observed toward genes with high numbers of peaks being more highly expressed than those with 0 or few peaks. Notably the gene with the most associated peaks (n = 20) was Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4, previously known as gut-enriched Krüppel-like factor or GKLF), which is a key activating transcription factor in the intestinal epithelium (54). Also among the genes with nine or more open chromatin peaks nearby is CFTR, which is critical for normal fluid transport in the intestinal epithelium, and the marker of single layer epithelial cells keratin 8 (KRT8). The RNA-Seq data for several genes were validated by RT-qPCR (Suppl. Fig. S4.). Genes with nine or more open chromatin peaks nearby were subjected to a gene ontology process enrichment analysis using Clusterprofiler (Fig. 2D). The results identified many genes and biological processes that are relevant to intestinal epithelial function. These include phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulatory subunit 1 (PI3KR1) and other genes with a role in actin filament organization (22), Runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) among steroid hormone response genes, and KLF4 together with other genes with a role in epithelial response to wounding (38). This analysis reveals the biological relevance of the intestinal organoid culture model to human intestinal function.

Human intestinal organoids and Caco2 cells exhibit global differences in open chromatin and gene expression.

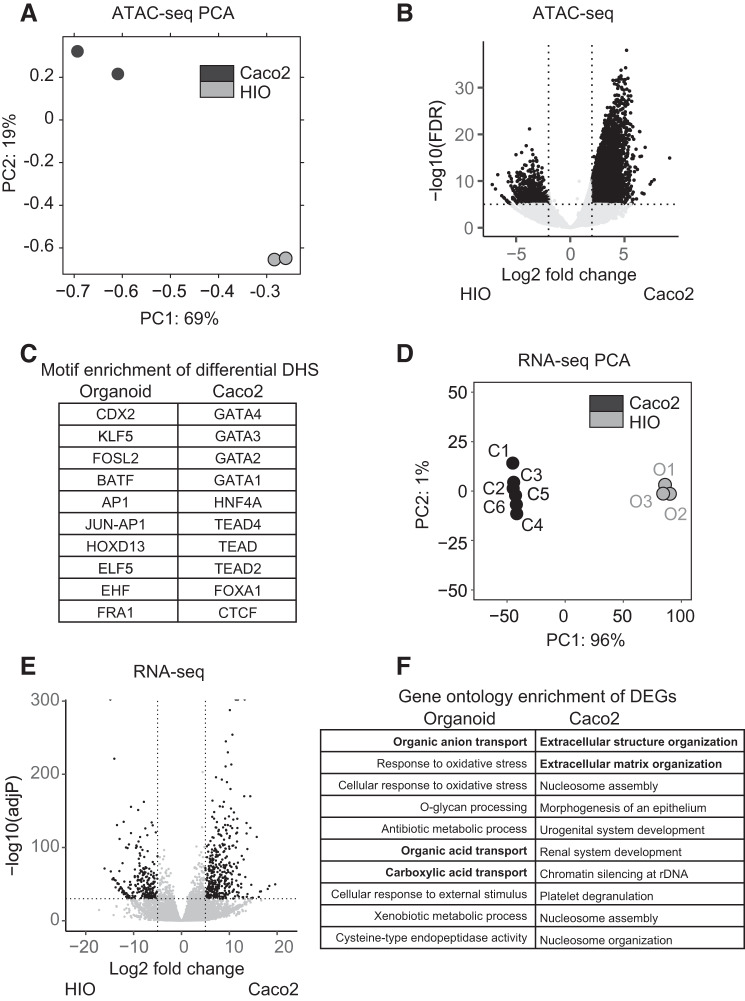

Caco2 is a widely used model for investigating intestinal epithelial function; however, as a colon cancer cell line it does not exhibit normal intestinal epithelial physiology. We predicted that the global differences between the open chromatin profiles of HIO and Caco2 cells would reflect the higher physiological relevance of the organoids. First, principal component analysis (PCA) of the HIO and Caco2 cell ATAC-Seq peaks was performed and showed that the biological replicates of the human organoid samples clustered closely together as did the Caco2 cells, though the HIO and Caco2 samples were strongly divergent (Fig. 3A). To find differentially open chromatin sites between HIO and Caco2 cells, high confidence peaks were merged from both data sets to form a common set of 50,630 peaks, and the number of reads counted. The volcano plot (statistical significance correlated with fold-change) (Fig. 3B) identified thousands of significantly differentially open chromatin sites between HIO and Caco2 cells; 7,713 open chromatin sites are significantly more open in Caco2; and 979 are specific to HIO. The result of a search for transcription factor binding motif enrichment within differential open chromatin regions is illustrated in Fig. 3C (the full lists are shown in Suppl. Table S2, A and B). There is no overlap between the top 10 most overrepresented motifs in the HIO and Caco2 cell ATAC-Seq peaks. Consistent with our earlier observation of a robust peak of open chromatin at the CDX2 gene promoter, binding motifs for this factor are highly enriched in the organoid-specific peak sets (>15%) (Suppl. Table S2, A and B). Similarly, a prominent ATAC-Seq peak seen at the Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) gene promoter correlates with substantial enrichment of its motifs in organoid open chromatin. The overrepresented motifs in Fig. 3C indicate an important role for CDX2 and KLF5, together with the Ets-family transcription factors Ets homologous factor (EHF) and E47-like factor 5 (ELF5) specifically in organoids (17, 18). In contrast, GATA factor motifs are the most overrepresented in Caco2 cells.

Fig. 3.

Open chromatin regions and gene expression distinguish human colon organoids from Caco2 cells. A: principal component analysis (PCA) plot of all replicates of Caco2 and human intestinal organoid (HIO) ATAC-Seq profiles with percentage variance labeled. B: volcano plot of the differentially open chromatin regions between HIO and Caco2. Significant differentially open sites are shown in black. FDR, false discovery rate. C: top 10 enriched motifs for the differentially open regions in HIO and Caco2 ATAC-Seq. D: PCA plot of all replicates of Caco2 and HIO RNA-Seq profiles with percentage variance labeled. E: volcano plot of the differentially expressed genes between HIO and Caco2. Significant differentially expressed genes are highlighted in black. F: gene ontology enrichment for genes differentially expressed (DGEs) in HIO and Caco2 RNA-Seq.

Next, we compared gene expression profiles between HIOs and Caco2 cells. The PCA plot in Fig. 3D shows global gene expression profiles of three HIO samples clustering together, as do the profiles of five replicas of Caco2 cells, though there is substantial separation between the organoid and cell line samples. The volcano plot in Fig. 3E shows hundreds of significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between HIO and Caco2 cells with 369 genes more highly expressed in Caco2 and 227 genes in HIO, again highlighting the difference between these two cell populations. Gene ontology process enrichment analysis on these DEGs (Fig. 3F) shows that the organoids better reproduce the functions of normal human intestinal epithelium function than do Caco2 cells. As examples, O-glycan processing, which is a critical part of the decoration of intestinal mucins (23), and organic ion transport (44) are processes identified in HIO, whereas DEGs in Caco2 correlate more strongly with epithelial development and extracellular matrix-related functions.

Common features of open chromatin and gene expression in human intestinal organoids and Caco2 cells grown in monolayers or cysts.

Though we observed global differences in the open chromatin profiles and gene expression between HIOs and Caco2 cells, which reinforced the utility of the organoids to better assay functions of the intestinal epithelium, the two models also have many common features. Here we consider the peaks of open chromatin that are shared between both cell types and the overlap in their gene expression profiles. Motif enrichment analysis on the ATAC-Seq peaks in common between HIOs (Fig. 4A) and Caco2 cells (Fig. 4B) identified motifs highly enriched in both culture models, with the top 40 enriched motifs shown in Suppl. Table S3, A and B. These include Forkhead Box A2 (FOXA2), HNF1 Homeobox A (HNF1a), and CDX2, which are all lineage-defining TFs for epithelial cells. Since there is overlap between the TFs that are overrepresented in differential and common peaks of open chromatin between HIO and Caco2 cells, this suggests that the combination of a complex of TFs and their cofactors likely underlies the differential occupancies. Also, not unexpectedly, given its pivotal role in chromatin architecture and at invariant TAD boundaries, the most overrepresented motif in both data sets is that for the architectural protein CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF). Gene expression comparisons between HIO and Caco2 also reveal similarities between the two cell types for several genes of importance in intestinal epithelial function (Fig. 4C). CFTR is highly expressed in both models, as are other genes involved in ion transport (Fig. 4D), tight junctions (Fig. 4E), and encoding transcription factors (Fig. 4F). Among the very few ion channels that are differentially expressed between HIOs and Caco2 are calcium-activated chloride channel protein 1 (CLCA1) and calcium-activated chloride channel protein 4 (CLCA4), which are more abundant in HIO. Together, the data indicate that both Caco2 cells and HIOs are of value to study aspects of enterocyte function.

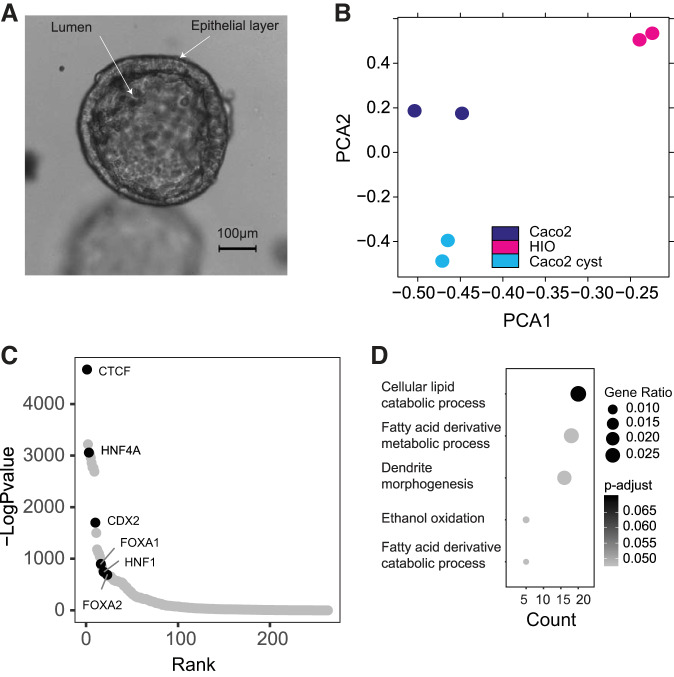

In addition to analyzing Caco2 cells grown as monolayers, we developed Caco2 cysts in Matrigel, where the cells form hollow spherical structures similar to HIOs (Fig. 5A). ATAC-Seq analysis shows that the open chromatin profile of Caco2 cells changes in the transition from 2D to 3D cysts. The PCA plot (Fig. 5B) shows substantial differences between HIO and Caco2 cells in monolayer and organoids, and strong overlap of biological replicates. First, a comparison of the overrepresented motifs in genome-wide open chromatin in Caco2 cysts (Fig. 5C) compared with Caco2 cells (Fig. 4B) identifies the motifs for the intestinal transcription factors HNF4A and CDX2 only in the organoids (Fig. 5C). This suggests a global change in the Caco2 transcriptional program is occurring during the 2D to 3D transition. To examine whether these changes impact the biological processes in Caco2 cells, we compared peaks of open chromatin in Caco2 cysts and HIOs, to identify those unique to HIOs. Next, a gene ontology process enrichment analysis was performed on genes associated with HIO-restricted peaks lying within the locus and the 20 kb upstream and downstream flanking regions. This analysis revealed enrichment of pathways involved in lipid and fatty acid metabolism (Fig. 5D). These processes were absent from an identical gene ontology analysis of the Caco2 cyst-unique open chromatin peak set. These results suggest that while growth as organoids drives Caco2 cells toward the primary intestinal epithelial transcriptional program, the cells may still lack the ability to perform key functions of the normal tissue.

Fig. 5.

Open chromatin profiling of Caco2 cysts shows signature features of their functional genomics. A: a Caco2 cyst grown in 3D in Matrigel. B: principal component analysis (PCA) plot of all replicates of Caco2 cysts, Caco2 cells and human intestinal organoid (HIO) ATAC-Seq profiles. C: transcription factor motifs ranked by enrichment under global open chromatin peaks in Caco2 cysts. D: gene ontology process enrichment analysis for genes associated with HIO unique open chromatin peaks when compared with Caco2 cysts.

DISCUSSION

With the expanding use of organoids to model intestinal processes and diseases, the HIO open chromatin landscape that we document here provides an important framework for understanding the genomic and epigenetic determinants of gene regulation in the intestinal epithelium. Our data are particularly relevant to investigating CFTR function and regulation. Intestinal organoid swelling is a robust assay for CFTR function and is used to monitor the impact of mutations in the CFTR gene and variants in the noncoding regions of the locus. An accurate map of the location of active CREs across the CFTR locus in HIO is required for these experiments, and hence our data provide an important resource. Our ATAC-Seq profiling in intestinal organoids shows that some of the CREs identified previously in intestinal cell lines are conserved, enabling accurate predictions of the activating transcription factor recruited to these elements and of features of the local chromatin architecture. We also found novel peaks of open chromatin that were found only in organoids, and further studies will be required to determine their role in CFTR gene regulation. In addition to the relevance of our data to CF it may contribute to understanding the mechanisms underlying other intestinal diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). For example, a previous genome-wide association study identified HNF4A as a locus of relevance to ulcerative colitis (2a), and Hnf4A null mice exhibit an IBD-like phenotype (12). These results are consistent with our data suggesting that HNF4A is a critical TF in both HIO and Caco2 cysts.

Our study also illustrates the power of combined functional genomics analyses to reveal important features of a differentiated tissue. Using information from ATAC-Seq peaks alone to predict active genes in HIO, gene ontology process enrichment analysis identified general cellular processes rather than intestine-specific ones (Suppl. Fig. S3). However, integration of the HIO RNA-Seq data identified 66 genes with novel peaks of open chromatin nearby that correlated with expression, and these were associated with several epithelial-specific functions (Fig. 2D). Also of note is the expression of a substantial number of genes with intronic peaks of open chromatin but none at their promoters, suggesting that either ATAC-Seq is less effective at detecting promoters or that these genes may use alternative promoters or other regulatory mechanisms to drive expression (Fig. 2D).

While our previous work profiled open chromatin regions in colon adenocarcinoma cell lines (16), the extent to which these cell lines represent the functional genomics of the colonic epithelium was unknown. Here we uncover the similarities and the differences between HIO and Caco2 cells, which are commonly used as a model for enterocytes. Gene expression levels and the enrichment of TFs in peaks of open chromatin illustrate the limitations of Caco2 cells (Fig. 4). Although many genes that are critical for normal intestinal function are expressed similarly in HIO and Caco2 cells, others are not. Notable differences include the intestine-specific master regulator gene CDX2, which is second only to CTCF in its motif enrichment among open chromatin peaks in HIOs but is far less enriched in Caco2 cell peaks. Loss of CDX2 expression is associated with ~20% of colorectal cancer cases and is a strong prognostic biomarker (20). In contrast, increased expression of CDX2 is observed in human endoderm differentiation into intestinal lineages (48). The oncogenic pioneer factor FOXA1 was more highly expressed in Caco2 cells than in HIOs, and this observation could be a tumorigenesis-related event, perhaps correlating with the potential of FOXA1 to reprogram open chromatin. Of note, our data from Caco2 cysts suggest that though 3D culture conditions enhance the utility of this cell line to mirror normal intestinal function, the associated changes are insufficient to fully recapitulate the biological pathways evident in HIOs. Our functional genomics results reinforce the physiological data from others that show the superiority of HIO as a valuable resource for mechanistic studies on the molecular basis of intestinal disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01 HL094585 (A. Harris), and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (Harris 16G0, 15/17XX0, and 18P0), Department of Defense PR150084 (M. Longworth), Cure for IBD Foundation and VeloSano grants (M. Longworth).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.Y., G.R., and A.H. conceived and designed research; S.Y., G.R., J.L.K., S.H., A.P., M.D., J.B., S.-H.L., M.L., and A.H. performed experiments; S.Y., G.R., J.L.K., M.L., and A.H. analyzed data; S.Y. and G.R. interpreted results of experiments; S.Y. and G.R. prepared figures; S.Y., G.R., and A.H. drafted manuscript; S.Y., J.L.K., S.H., M.D., J.B., S.-H.L., M.L., and A.H. edited and revised manuscript; S.Y., G.R., J.L.K., S.H., A.P., M.D., J.B., S.-H.L., M.L., and A.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Pieter Faber and colleagues at the University of Chicago Genomics Core for NGS, also Dr. Stevephen Hung for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G; The Gene Ontology Consortium . Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 25: 25–29, 2000. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449: 1003–1007, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Barrett JC, Lee JC, Lees CW, Prescott NJ, Anderson CA, Phillips A, Wesley E, Parnell K, Zhang H, Drummond H, Nimmo ER, Massey D, Blaszczyk K, Elliott T, Cotterill L, Dallal H, Lobo AJ, Mowat C, Sanderson JD, Jewell DP, Newman WG, Edwards C, Ahmad T, Mansfield JC, Satsangi J, Parkes M, Mathew CG, Donnelly P, Peltonen L, Blackwell JM, Bramon E, Brown MA, Casas JP, Corvin A, Craddock N, Deloukas P, Duncanson A, Jankowski J, Markus HS, Mathew CG, McCarthy MI, Palmer CN, Plomin R, Rautanen A, Sawcer SJ, Samani N, Trembath RC, Viswanathan AC, Wood N, Spencer CC, Barrett JC, Bellenguez C, Davison D, Freeman C, Strange A, Donnelly P, Langford C, Hunt SE, Edkins S, Gwilliam R, Blackburn H, Bumpstead SJ, Dronov S, Gillman M, Gray E, Hammond N, Jayakumar A, McCann OT, Liddle J, Perez ML, Potter SC, Ravindrarajah R, Ricketts M, Waller M, Weston P, Widaa S, Whittaker P, Deloukas P, Peltonen L, Mathew CG, Blackwell JM, Brown MA, Corvin A, McCarthy MI, Spencer CC, Attwood AP, Stephens J, Sambrook J, Ouwehand WH, McArdle WL, Ring SM, Strachan DP; UK IBD Genetics Consortium; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 . Genome-wide association study of ulcerative colitis identifies three new susceptibility loci, including the HNF4A region. Nat Genet 41: 1330–1334, 2009. doi: 10.1038/ng.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkers G, van Mourik P, Vonk AM, Kruisselbrink E, Dekkers JF, de Winter-de Groot KM, Arets HGM, Marck-van der Wilt REP, Dijkema JS, Vanderschuren MM, Houwen RHJ, Heijerman HGM, van de Graaf EA, Elias SG, Majoor CJ, Koppelman GH, Roukema J, Bakker M, Janssens HM, van der Meer R, Vries RGJ, Clevers HC, de Jonge HR, Beekman JM, van der Ent CK. Rectal Organoids Enable Personalized Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis. Cell Rep 26: 1701–1708.e1703, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bischof JM, Gillen AE, Song L, Gosalia N, London D, Furey TS, Crawford GE, Harris A. A genome-wide analysis of open chromatin in human epididymis epithelial cells reveals candidate regulatory elements for genes coordinating epididymal function. Biol Reprod 89: 104, 2013. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.110403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bischof JM, Ott CJ, Leir SH, Gosalia N, Song L, London D, Furey TS, Cotton CU, Crawford GE, Harris A. A genome-wide analysis of open chromatin in human tracheal epithelial cells reveals novel candidate regulatory elements for lung function. Thorax 67: 385–391, 2012. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blighe K. EnhancedVolcano: Publication-ready volcano plots with enhanced colouring and labeling. 2019.

- 7.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods 10: 1213–1218, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clevers H. Modeling Development and Disease with Organoids. Cell 165: 1586–1597, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corces MR, Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Greenside PG, Chan SM, Koenig JL, Snyder MP, Pritchard JK, Kundaje A, Greenleaf WJ, Majeti R, Chang HY. Lineage-specific and single-cell chromatin accessibility charts human hematopoiesis and leukemia evolution. Nat Genet 48: 1193–1203, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ng.3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corces MR, Trevino AE, Hamilton EG, Greenside PG, Sinnott-Armstrong NA, Vesuna S, Satpathy AT, Rubin AJ, Montine KS, Wu B, Kathiria A, Cho SW, Mumbach MR, Carter AC, Kasowski M, Orloff LA, Risca VI, Kundaje A, Khavari PA, Montine TJ, Greenleaf WJ, Chang HY. An improved ATAC-seq protocol reduces background and enables interrogation of frozen tissues. Nat Methods 14: 959–962, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darsigny M, Babeu JP, Dupuis AA, Furth EE, Seidman EG, Lévy E, Verdu EF, Gendron FP, Boudreau F. Loss of hepatocyte-nuclear-factor-4alpha affects colonic ion transport and causes chronic inflammation resembling inflammatory bowel disease in mice. PLoS One 4: e7609, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dekkers JF, Berkers G, Kruisselbrink E, Vonk A, de Jonge HR, Janssens HM, Bronsveld I, van de Graaf EA, Nieuwenhuis EE, Houwen RH, Vleggaar FP, Escher JC, de Rijke YB, Majoor CJ, Heijerman HG, de Winter-de Groot KM, Clevers H, van der Ent CK, Beekman JM. Characterizing responses to CFTR-modulating drugs using rectal organoids derived from subjects with cystic fibrosis. Sci Transl Med 8: 344ra84, 2016. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad8278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dekkers JF, Wiegerinck CL, de Jonge HR, Bronsveld I, Janssens HM, de Winter-de Groot KM, Brandsma AM, de Jong NW, Bijvelds MJ, Scholte BJ, Nieuwenhuis EE, van den Brink S, Clevers H, van der Ent CK, Middendorp S, Beekman JM. A functional CFTR assay using primary cystic fibrosis intestinal organoids. Nat Med 19: 939–945, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nm.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dotti I, Salas A. Potential Use of Human Stem Cell-Derived Intestinal Organoids to Study Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 24: 2501–2509, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fogh J, Wright WC, Loveless JD. Absence of HeLa cell contamination in 169 cell lines derived from human tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 58: 209–214, 1977. doi: 10.1093/jnci/58.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fossum SL, Mutolo MJ, Tugores A, Ghosh S, Randell SH, Jones LC, Leir SH, Harris A. Ets homologous factor (EHF) has critical roles in epithelial dysfunction in airway disease. J Biol Chem 292: 10938–10949, 2017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.775304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fossum SL, Mutolo MJ, Yang R, Dang H, O’Neal WK, Knowles MR, Leir SH, Harris A. Ets homologous factor regulates pathways controlling response to injury in airway epithelial cells. Nucleic Acids Res 42: 13588–13598, 2014. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillen AE, Yang R, Cotton CU, Perez A, Randell SH, Leir SH, Harris A. Molecular characterization of gene regulatory networks in primary human tracheal and bronchial epithelial cells. J Cyst Fibros 17: 444–453, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graule J, Uth K, Fischer E, Centeno I, Galván JA, Eichmann M, Rau TT, Langer R, Dawson H, Nitsche U, Traeger P, Berger MD, Schnüriger B, Hädrich M, Studer P, Inderbitzin D, Lugli A, Tschan MP, Zlobec I. CDX2 in colorectal cancer is an independent prognostic factor and regulated by promoter methylation and histone deacetylation in tumors of the serrated pathway. Clin Epigenetics 10: 120, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s13148-018-0548-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grün D, Lyubimova A, Kester L, Wiebrands K, Basak O, Sasaki N, Clevers H, van Oudenaarden A. Single-cell messenger RNA sequencing reveals rare intestinal cell types. Nature 525: 251–255, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nature14966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guinebault C, Payrastre B, Racaud-Sultan C, Mazarguil H, Breton M, Mauco G, Plantavid M, Chap H. Integrin-dependent translocation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase to the cytoskeleton of thrombin-activated platelets involves specific interactions of p85 alpha with actin filaments and focal adhesion kinase. J Cell Biol 129: 831–842, 1995. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanisch FG. O-glycosylation of the mucin type. Biol Chem 382: 143–149, 2001. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell 38: 576–589, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jattan J, Rodia C, Li D, Diakhate A, Dong H, Bataille A, Shroyer NF, Kohan AB. Using primary murine intestinal enteroids to study dietary TAG absorption, lipoprotein synthesis, and the role of apoC-III in the intestine. J Lipid Res 58: 853–865, 2017. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M071340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleinman HK, Martin GR. Matrigel: basement membrane matrix with biological activity. Semin Cancer Biol 15: 378–386, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolde R. Pheatmap: pretty heatmaps. R package version 61: 617, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambert SA, Jolma A, Campitelli LF, Das PK, Yin Y, Albu M, Chen X, Taipale J, Hughes TR, Weirauch MT. The Human Transcription Factors. Cell 172: 650–665, 2018. [Erratum in Cell 175: 598; 599, 2018] doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lancaster MA, Knoblich JA. Organogenesis in a dish: modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science 345: 1247125, 2014. doi: 10.1126/science.1247125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li D, Dong H, Kohan AB. The Isolation, Culture, and Propagation of Murine Intestinal Enteroids for the Study of Dietary Lipid Metabolism. Methods Mol Biol 1576: 195–204, 2017. doi: 10.1007/7651_2017_69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCracken KW, Howell JC, Wells JM, Spence JR. Generating human intestinal tissue from pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Nat Protoc 6: 1920–1928, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McHugh DR, Steele MS, Valerio DM, Miron A, Mann RJ, LePage DF, Conlon RA, Cotton CU, Drumm ML, Hodges CA. A G542X cystic fibrosis mouse model for examining nonsense mutation directed therapies. PLoS One 13: e0199573, 2018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mi H, Huang X, Muruganujan A, Tang H, Mills C, Kang D, Thomas PD. PANTHER version 11: expanded annotation data from Gene Ontology and Reactome pathways, and data analysis tool enhancements. Nucleic Acids Res 45, D1: D183–D189, 2017. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyoshi H, Stappenbeck TS. In vitro expansion and genetic modification of gastrointestinal stem cells in spheroid culture. Nat Protoc 8: 2471–2482, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mouchel N, Henstra SA, McCarthy VA, Williams SH, Phylactides M, Harris A. HNF1alpha is involved in tissue-specific regulation of CFTR gene expression. Biochem J 378: 909–918, 2004. doi: 10.1042/bj20031157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narendra V, Bulajić M, Dekker J, Mazzoni EO, Reinberg D. CTCF-mediated topological boundaries during development foster appropriate gene regulation. Genes Dev 30: 2657–2662, 2016. doi: 10.1101/gad.288324.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ott CJ, Blackledge NP, Kerschner JL, Leir SH, Crawford GE, Cotton CU, Harris A. Intronic enhancers coordinate epithelial-specific looping of the active CFTR locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 19934–19939, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900946106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ou L, Shi Y, Dong W, Liu C, Schmidt TJ, Nagarkatti P, Nagarkatti M, Fan D, Ai W. Kruppel-like factor KLF4 facilitates cutaneous wound healing by promoting fibrocyte generation from myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Invest Dermatol 135: 1425–1434, 2015. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogerson C, Britton E, Withey S, Hanley N, Ang YS, Sharrocks AD. Identification of a primitive intestinal transcription factor network shared between esophageal adenocarcinoma and its precancerous precursor state. Genome Res 29: 723–736, 2019. doi: 10.1101/gr.243345.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato T, Stange DE, Ferrante M, Vries RG, Van Es JH, Van den Brink S, Van Houdt WJ, Pronk A, Van Gorp J, Siersema PD, Clevers H. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology 141: 1762–1772, 2011. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459: 262–265, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwank G, Koo BK, Sasselli V, Dekkers JF, Heo I, Demircan T, Sasaki N, Boymans S, Cuppen E, van der Ent CK, Nieuwenhuis EE, Beekman JM, Clevers H. Functional repair of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in intestinal stem cell organoids of cystic fibrosis patients. Cell Stem Cell 13: 653–658, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spence JR, Mayhew CN, Rankin SA, Kuhar MF, Vallance JE, Tolle K, Hoskins EE, Kalinichenko VV, Wells SI, Zorn AM, Shroyer NF, Wells JM. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature 470: 105–109, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stieger B, Hagenbuch B. Organic anion-transporting polypeptides. Curr Top Membr 73: 205–232, 2014. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800223-0.00005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki K, Murano T, Shimizu H, Ito G, Nakata T, Fujii S, Ishibashi F, Kawamoto A, Anzai S, Kuno R, Kuwabara K, Takahashi J, Hama M, Nagata S, Hiraguri Y, Takenaka K, Yui S, Tsuchiya K, Nakamura T, Ohtsuka K, Watanabe M, Okamoto R. Single cell analysis of Crohn’s disease patient-derived small intestinal organoids reveals disease activity-dependent modification of stem cell properties. J Gastroenterol 53: 1035–1047, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1437-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swahn H, Sabith Ebron J, Lamar K-M, Yin S, Kerschner JL, NandyMazumdar M, Coppola C, Mendenhall EM, Leir S-H, Harris A. Coordinate regulation of ELF5 and EHF at the chr11p13 CF modifier region. J Cell Mol Med 23: 7726–7740, 2019. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.The Gene Ontology Consortium The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res 47, D1: D330–D338, 2019. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai YH, Hill DR, Kumar N, Huang S, Chin AM, Dye BR, Nagy MS, Verzi MP, Spence JR. LGR4 and LGR5 Function Redundantly During Human Endoderm Differentiation. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2: 648–662, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Flier LG, Clevers H. Stem cells, self-renewal, and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Annu Rev Physiol 71: 241–260, 2009. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu P, Becker H, Elizalde M, Masclee A, Jonkers D. Intestinal organoid culture model is a valuable system to study epithelial barrier function in IBD. Gut 67: 1905–1906, 2018. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang R, Kerschner JL, Gosalia N, Neems D, Gorsic LK, Safi A, Crawford GE, Kosak ST, Leir SH, Harris A. Differential contribution of cis-regulatory elements to higher order chromatin structure and expression of the CFTR locus. Nucleic Acids Res 44: 3082–3094, 2016. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16: 284–287, 2012. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang W, Chen X, Kato Y, Evans PM, Yuan S, Yang J, Rychahou PG, Yang VW, He X, Evers BM, Liu C. Novel cross talk of Kruppel-like factor 4 and beta-catenin regulates normal intestinal homeostasis and tumor repression. Mol Cell Biol 26: 2055–2064, 2006. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2055-2064.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Z, Ott CJ, Lewandowska MA, Leir SH, Harris A. Molecular mechanisms controlling CFTR gene expression in the airway. J Cell Mol Med 16: 1321–1330, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao J, Bulek K, Gulen MF, Zepp JA, Karagkounis G, Martin BN, Zhou H, Yu M, Liu X, Huang E, Fox PL, Kalady MF, Markowitz SD, Li X. Human Colon Tumors Express a Dominant-Negative Form of SIGIRR That Promotes Inflammation and Colitis-Associated Colon Cancer in Mice. Gastroenterology 149: 1860–1871, 2015. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zomer-van Ommen DD, Vijftigschild LA, Kruisselbrink E, Vonk AM, Dekkers JF, Janssens HM, de Winter-de Groot KM, van der Ent CK, Beekman JM. Limited premature termination codon suppression by read-through agents in cystic fibrosis intestinal organoids. J Cyst Fibros 15: 158–162, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]