Abstract

Introduction

Changes in personality characteristics are associated with the onset of symptoms in Alzheimer's disease (AD) and may even precede clinical diagnosis. However, personality changes caused by disease progression can be difficult to separate from changes that occur with normal aging. The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) provides a unique cohort in which to relate measures of personality traits to in vivo markers of disease in a much younger sample than in typical late onset AD.

Methods

Personality traits measured with the International Personality Item Pool at baseline from DIAN participants were analyzed as a function of estimated years to onset of clinical symptoms and well‐established AD biomarkers.

Results

Both neuroticism and conscientiousness were correlated with years to symptom onset and markers of tau pathology in the cerebrospinal fluid. Self‐reported conscientiousness and both neuroticism and conscientiousness ratings from a collateral source were correlated with longitudinal rates of cognitive decline such that participants who were rated as higher on neuroticism and lower on conscientiousness exhibited accelerated rates of cognitive decline.

Discussion

Personality traits are correlated with the accumulation of AD pathology and time to symptom onset, suggesting that AD progression can influence an individual's personality characteristics. Together these findings suggest that measuring neuroticism and conscientiousness may hold utility in tracking disease progression in AD.

1. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by the cerebral accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) into plaques and the aggregation of the tau protein into neurofibrillary tangles. These pathological processes, when measured in vivo with cerebrospinal fluid or neuroimaging biomarkers, can begin decades before the manifestation of clinical symptoms. 1 , 2 Nevertheless, the rate of progression into the symptomatic stages of the disease is very heterogeneous, even among individuals who exhibit elevated levels of amyloid. 3 This variability in progression could be due to a number of mechanisms including cognitive reserve, 4 which can protect function even into milder stages of the disease. Thus, it is important to identify individual characteristics or traits that may moderate rates of clinical progression.

One such factor that has received recent attention in the literature is personality. Personality traits refer to enduring characteristics including attitudes, values, social behaviors, and habits that manifest predictably across situations. It is generally agreed upon that personality can be adequately captured by five major factors (collectively known as “the Big Five”): neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. 5 Some common adjectives that describe each of these traits are anxious and worrying (neuroticism), energetic and outgoing (extraversion), curious and insightful (openness), generous and forgiving (agreeableness), and efficient and organized (conscientiousness). 5 These traits have been shown to change with age 6 and are related to a variety of life outcomes including physical health, 7 depressive symptoms, 8 and even mortality. 9 Importantly, personality traits also change with the onset of clinical symptoms of AD. A review of the literature indicates that measures of neuroticism and conscientiousness show the largest and most reliable change before and after the onset of dementia in sporadic AD. 10 These same factors typically also show large differences between cognitively healthy older adults and those with either mild, 11 or very mild, dementia. 12 , 13 Furthermore, evidence suggests that high levels of neuroticism and/or low levels of conscientiousness confer the greatest risk for developing dementia in healthy older adults. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 Given the predictive power of personality, recent guidelines have even suggested incorporating these measures into clinical diagnoses of dementia. 18

The relationship of personality to underlying disease pathology has been recently examined. For example, Tautvydaitė and et al. 19 showed that changes in neuroticism (Cohen's d = ‐0.45) and conscientiousness (Cohen's d = 0.42) were related to abnormal amyloid levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), such that higher neuroticism and lower conscientiousness were associated with more pathology. However, this study was focused primarily on mild or moderately demented participants and personality change was assessed retrospectively, which may be subject to significant recall biases. Another recent study in cognitively normal participants showed that only neuroticism was correlated with levels of the tau protein (higher neuroticism is associated with more tau pathology, Cohen's d = 0.63) in key regions known to be vulnerable to pathological accumulation. 20 Thus, it would appear that both neuroticism and conscientiousness are modestly correlated with accumulating AD pathology, although it should be noted that at least one study has reported a null effect between amyloid and neuroticism. 21

Studies of change in personality and associated risk of dementia prior to the onset of symptoms in sporadic AD are complicated by a number of factors. First and foremost is the heterogeneity of progression in the earliest stages of the disease. As already mentioned, disease pathology can accumulate for decades prior to a clinical diagnosis, and hence study participants may enroll at different stages along the pathology continuum. A second issue involves myriad co‐morbid factors that might influence personality measurement even in cognitively normal older adults, such as depression and physical health. Combinations of these different factors may preclude or artificially inflate the detection of preclinical personality change in an older adult cohort. 8 , 22

We aimed to address these limitations by exploring the relationships among personality, time to onset of dementia symptoms, levels of AD biomarkers, and cognitive change in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) cohort. DIAN is an international observational study of families with presenilin 1 (PSEN1), presenilin 2 (PSEN2), and amyloid precursor protein (APP) autosomal dominant AD mutations. Onset of disease in this population is predictable as persons with a particular mutation tend to develop symptoms at a similar age. 23 Age of symptom onset in autosomal dominant AD (ADAD) is typically 30 to 40 years earlier compared to the far more common sporadic AD. This confers a tremendous opportunity to study AD pathology with little to no confounding from age‐related comorbidities. 24

We address three primary questions in the current study. First, do personality traits discriminate between mutation carriers and noncarriers in DIAN? A prior study in the DIAN cohort showed the largest differences between clinically normal individuals and those with very mild dementia occurred in conscientiousness with smaller effects manifesting in both neuroticism and extraversion, 25 and we expected to replicate this finding with a larger sample size. Our second question was whether baseline differences in personality correlate with difference in levels of key AD biomarkers. Based on the literature reviewed above, we hypothesized that neuroticism and conscientiousness would correlate with levels of AD pathology measured with in vivo biomarkers. The third, and most important, question that we addressed is whether differences in personality traits would directly correlate with longitudinal changes in cognitive performance. An important aspect of the data collection strategy was that personality was assessed using both self‐report as well as ratings from a collateral source. Other studies in sporadic AD have suggested that collateral source ratings of personality provide more diagnostic information than ratings from the participant; 12 , 15 thus, we hypothesized that collateral source reports may provide a more sensitive metric by which to gauge personality change in DIAN.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

Participants in the DIAN observational study complete annual or semi‐annual assessments of clinical and cognitive functioning together with a comprehensive biomarker panel. Currently, there are 20 DIAN performance sites across the United States, Asia, Europe, Australia, and South America. Participants are typically recruited via word of mouth, by family physicians, or via the DIAN Expanded Registry. To be eligible to participate in DIAN, participants must be 18 years of age or older, be the child of an affected individual (known clinically or via genetic testing), and have two non‐sibling collateral sources. The frequency of assessments in DIAN depends on the individual's clinical status and estimated time to symptom onset. All asymptomatic DIAN participants who are <5 years past estimated age of symptom onset return for in‐person visits every other year (prior to 2014 they returned every 3 years), with follow‐up phone calls in off years. Participants who are >5 years past estimated age of onset and asymptomatic will receive yearly follow‐up phone calls only. Symptomatic DIAN participants (defined as Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR] > 0) return for annual in‐person visits. Those participants who know themselves to be mutation positive are >5 years past estimated age of symptom onset and asymptomatic will maintain the every other year in‐person visit schedule.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: The authors reviewed the literature using traditional sources including PubMed and Google Scholar. Personality has been studied extensively as a risk factor for late‐onset Alzheimer's disease (AD). There are few publications that include biomarkers and we were unable to find any that evaluated personality systematically in autosomal dominant AD. Relevant publications were cited.

Interpretation: Assessing personality in autosomal AD provides an opportunity to understand disease‐related personality changes at much younger ages than in late‐onset AD. Conscientiousness and neuroticism were related to markers of neurodegeneration and predicted disease progression and cognitive decline, largely mirroring what is observed in late‐onset AD.

Future directions: The findings suggest that personality may have unique value as an indicator of disease progression. Additional studies should determine the extent to which longitudinal evaluations of personality are necessary to monitor disease progression. Also, the utility of brief personality assessments should be explored.

Data from participants in the current study were taken from DIAN data freeze 13 (cutoff date: June 30, 2018) and were classified based on genetic mutation as either a mutation non‐carrier (NC) or a mutation carrier (MC). Baseline personality data were available on 192 NCs and 304 MCs and of these, 118 NCs and 195 MCs contributed at least one post‐baseline visit. Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of this cohort are provided in Table 1. We can determine when a given individual will begin to experience symptoms by subtracting their current age from the average symptom onset age of all participants with that specific mutation. For NC, the average age of onset for the family mutation was used. If the mutation is unknown (eg, if the mutation was recently discovered), then the age of symptom onset in the affected parent is used. We refer to this measure as the estimated years to onset (EYO), which provides a stable marker of disease progression that is independent from biological indicators.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort at baseline

| Non‐carriers(n = 192) | Mutation carriers(n = 304) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Z score | Min/Max | Mean | SD | Z score | Min/Max | |

| Age (years) | 37.95 | 11.31 | 0.02 | 18/69 | 37.68 | 10.69 | −0.01 | 18/65 |

| Education (years) | 14.92 | 2.79 | 0.14 | 9/26 | 14.24 | 3.05 | −0.09 | 6/29 |

| EYO (years) | −10.29 | 11.88 | −0.06 | −38/23 | −9.17 | 10.71 | 0.04 | −36/12.3 |

| CSF Aβ42 (pg/mL) | 454.09 | 142.80 | 0.34 | 133/905 | 356.64 | 186.94 | −0.21 | 75.6/1049.0 |

| CSF total tau (pg/mL) | 57.139 | 24.567 | −0.46 | 7/174 | 105.41 | 75.09 | 0.28 | 8.2/563/3 |

| CSF pTau (pg/mL) | 28.844 | 10.345 | −0.58 | 10/87 | 59.61 | 36.62 | 0.36 | 12.4/191.4 |

| PIB | 1.055 | 0.148 | −0.57 | 0.85/2.76 | 1.89 | 0.99 | 0.40 | 0.8/5.8 |

| CDR‐SB | 0.008 | 0.062 | −0.36 | 0/0.5 | 1.02 | 2.09 | 0.23 | 0/17 |

| % CDR 0 | 100% | NA | 66% | NA | ||||

| % CDR 0.5 | 0% | NA | 24% | NA | ||||

| % CDR 1 | 0% | NA | 8% | NA | ||||

| % CDR 2 or 3 | 0% | NA | 1% | NA | ||||

| Sex (% female) | 59% | NA | 58% | NA | ||||

| Global cognition | −0.024 | 0.609 | −1.5/1.6 | −0.632 | 1.072 | −3.8/1.64 | ||

| Number of visits | 2.021 | 1.092 | 1/6 | 2.109 | 1.177 | 1/6 | ||

| Duration of follow‐up (years) | 2.422 | 2.427 | 0/8.2 | 37.678 | 10.689 | 0/8.1 | ||

| Self‐reported | ||||||||

| Neuroticism | 61.875 | 15.401 | −0.07 | 35/100 | 63.51 | 14.474 | 0.04 | 31/103 |

| Extraversion | 84.906 | 12.103 | 0.14 | 48/112 | 82.072 | 13.111 | −0.09 | 35/109 |

| Openness | 78.51 | 12.128 | 0.07 | 45/107 | 77.224 | 11.918 | −0.04 | 45/107 |

| Agreeableness | 96.146 | 9.473 | 0.05 | 59/115 | 95.329 | 10.345 | −0.03 | 61/120 |

| Conscientiousness | 96.266 | 11.519 | 0.21 | 58/115 | 91.819 | 13.649 | −0.13 | 52/120 |

| Informant reported | ||||||||

| Neuroticism | 58.812 | 16.567 | −0.22 | 26/102 | 64.532 | 15.712 | 0.14 | 30/105 |

| Extraversion | 85.489 | 12.398 | 0.25 | 44/112 | 79.621 | 15.184 | −0.16 | 36/108 |

| Openness | 76.898 | 10.384 | 0.19 | 46/106 | 73.386 | 11.97 | −0.12 | 38/100 |

| Agreeableness | 97.253 | 10.971 | 0.14 | 65/118 | 94.41 | 12.643 | −0.09 | 46/120 |

| Conscientiousness | 98.215 | 13.83 | 0.28 | 52/120 | 90.539 | 17.43 | −0.18 | 30/119 |

Abbreviations: Aβ42, amyloid beta 42; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CDR‐SB, Clinical Dementia Rating‐Sum of Boxes; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EYO, estimated years to onset; PIB, Pittsburgh compound B; pTau, phosphorylated tau; SD, standard deviation

2.2. Clinical assessment

At each visit, participants were assessed by an experienced clinician for the presence and severity of dementia with the CDR scale. 26 A CDR of 0 indicates no evidence of dementia and 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 indicates very mild, mild, moderate, and severe dementia, respectively. The CDR Sum of Boxes (CDR‐SB) score is also calculated as a finer‐grained measure of clinical impairment. Noncarriers with a CDR score >0 were removed prior to analysis as our focus is on ADAD rather than dementia attributable to other causes.

2.3. Personality assessment

A 120‐item version of the International Personality Item Pool 27 (IPIP‐NEO‐120) was completed by both the participant and a collateral source with respect to the participant. The IPIP‐NEO‐120 is a publicly available personality scale that has been translated into more than 25 languages. The individual is presented with a series of statements (eg, “Does things efficiently”), and is asked to rate the accuracy of the statement on a five‐point scale (1 = very inaccurate, 5 = very accurate). Responses to individual items are summed to form the five major personality domains (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness). Only the five domain scores (not individual items or subscales) were used in the present analyses. The participant rates the statements in reference to themselves whereas the collateral source rates the participant.

Domains formed from the IPIP‐NEO‐120 have been shown to map strongly onto the five‐factor personality model described above. Importantly, the IPIP‐NEO‐120 has high documented reliability (Cronbach's alphas: Neuroticism = 0.90, Extraversion = 0.89,; Openness = 0.81, Agreeableness = 0.86, and Conscientiousness = 0.90) and high correlations with other, established personality inventories. 27 Complete psychometric information and keys for scoring are available at the IPIP website (https://ipip.ori.org/30FacetNEO-PI-RItems.htm).

2.4. Cognitive assessment

All participants in DIAN complete a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery that has been described elsewhere. 25 From the available tests, we created a global cognitive composite score that consists of the Mini‐Mental State Exam (MMSE) 28 total score, Wechsler Memory Scale‐Revised, 29 Logical Memory Delayed Recall, Digit Symbol Substitution Task from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale‐ Revised, 30 and delayed recall of a 16‐item word list. Scores on each test were first standardized to the mean and standard deviation (SD) of DIAN mutation carriers with an EYO < ‐15. Importantly, because many participants are at ceiling on the MMSE, the SD is very small, which weights this test more strongly in the composite. Therefore, an adjusted SD for the MMSE was estimated from a smoothed spline model. 31 The z‐scores were then averaged together with equal weights to create the global composite. Tests are scored such that higher outcomes are indicative of better performance.

2.5. CSF collection

CSF was collected from a lumbar puncture in the morning after fasting as previously described. 32 Samples were shipped to the DIAN biomarker core for processing. Concentrations of Aβ1‐42, total tau, and tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (p‐tau181) were measured with Luminex‐based immunoassay (AlzBio3, Fujirebio, Malverne, PA, USA). Biomarkers were standardized to the mean and SD of the cohort at baseline.

2.6. Amyloid imaging

Amyloid imaging was performed with a bolus injection of ≈15 mCi of [11C] Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB 33 ). Data were used from 40 to 70 minutes post‐injection and were motion corrected and partial volume corrected using methods described elsewhere. 34 , 35 , 36 For each region of interest (ROI), the standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) was calculated using the cerebellum as a reference. A summary score was formed from the average SUVR across the following regions: lateral orbitofrontal, inferior parietal, precuneus, rostral middle frontal, superior frontal, superior temporal, and middle temporal. This value was then z‐scored to the mean and SD of the cohort at baseline.

3. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

3.1. Question 1

To determine whether mutation status influences personality, linear mixed effects (LME) models were constructed using the lme4 37 package in the R statistical environment. Within each set of analyses, we examined each personality factor (both self‐ and informant reported) in separate models. Specifically, we analyzed personality collected at the baseline assessment as a function of mutation status (dummy coded with noncarriers as the reference group), EYO, and the interaction between mutation status and EYO, while also controlling for CDR‐SB, sex, and years of education. The latter two variables have demonstrated correlations with specific personality traits and it is important to control for this shared variance. 38 , 39 Family cluster was included as a random effect. Cohen's d (calculated as [2 × t‐value]/sqrt[df]) is provided as a measure of effect size for all reported outcomes.

3.2. Question 2

We next examined whether levels of in vivo biomarkers (CSF and positron emission tomography [PET] imaging) correlate with personality traits in a subsample of MCs only. LME models were constructed with each personality factor (in separate models) predicted from the following terms: biomarker, baseline EYO, and baseline CDR‐SB, sex, and education with family cluster included as a random effect.

3.3. Question 3

Finally, to determine whether personality traits at baseline moderate rates of change in cognition, we again used LME models with the following terms: baseline EYO, baseline CDR‐SB, sex, education, baseline personality, years in the study (hereafter referred to as “time”), and the personality by time interaction. Random intercepts and slopes of time were included across participants.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Question 1: Baseline personality and mutation status

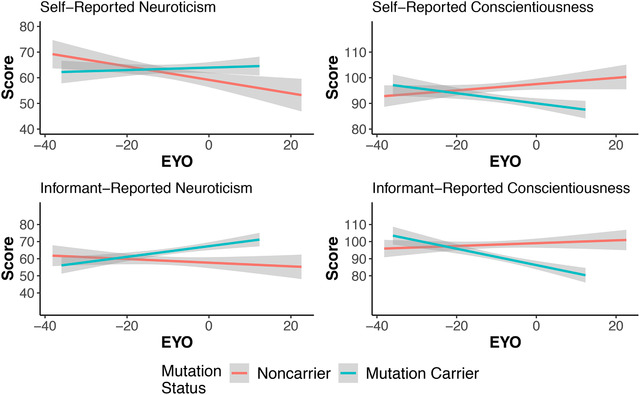

Self‐ and collateral source reports of each personality domain were modestly correlated in NC (Neuroticism = 0.53, Extraversion = 0.61, Openness = 0.63, Agreeableness = 0.42, Conscientiousness = 0.53) and in carriers (Neuroticism = 0.41, Extraversion = 0.58, Openness = 0.65, Agreeableness = 0.35, Conscientiousness = 0.49). For neuroticism, there was a main effect of mutation group (β = 4.34, standard error [SE] = 2.00, P = .03, Cohen's d = 0.20) indicating that MCs exhibited higher levels of neuroticism than NCs. This effect was qualified by a significant group by EYO interaction (β = 0.33, SE = 0.13, P = .01, Cohen's d = 0.23). This interaction indicates that NCs significantly declined in neuroticism across EYO (β = –0.31, SE = 0.09, P < .001, Cohen's d = –0.32) whereas mutation carriers remained stable (β = 0.02, SE = 0.09, P = .87, .02). Similarly, in conscientiousness, the main effect of mutation was significant (β = −5.45, SE = 1.70, P = .001, Cohen's d = –0.29) indicating lower conscientiousness in MCs relative to NCs, and the group by EYO interaction was also significant (β = –0.25, SE = 0.11, P = .02, Cohen's d = –0.21) indicating that NCs tended to increase in conscientiousness across EYO and MCs tended to decrease; however, neither simple effect was statistically significant. These relationships are shown in the top panel of Figure 1. There were no group differences or interactions on any other personality trait (see Table 2 for full model output).

FIGURE 1.

Personality traits as a function of estimated years to symptom onset (EYO) and mutation status (mutation carriers N = 304 for self‐report; 293 for informant report; non‐carriers N = 192 for self‐report, 186 for informant). Significant group by EYO interactions were found for all variables except for informant reported conscientiousness

TABLE 2.

Beta weights (and SEs) for models comparing group differences in personality traits

| Neuroticism | Extraversion | Openness | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self‐report | |||||

| Mutation | 4.34** | −3.03 | −1.12 | −0.003 | −5.45*** |

| (2.00) | (1.74) | (1.60) | (1.26) | (1.70) | |

| EYO | −0.31*** | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.07) | (0.06) | (0.08) | |

| CDR‐SB | 0.13 | −0.80 | −0.46 | 0.03 | −0.72 |

| (0.47) | (0.41) | (0.38) | (0.30) | (0.40) | |

| Sex | −2.58 | −1.71 | −3.49*** | −7.43*** | −3.40*** |

| (1.32) | (1.15) | (1.06) | (0.83) | (1.12) | |

| Education | −0.76*** | 0.10 | 0.59*** | 0.55*** | 0.63*** |

| (0.23) | (0.20) | (0.18) | (0.14) | (0.20) | |

| Mutation × EYO | 0.33** | −0.11 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.25** |

| (0.13) | (0.11) | (0.10) | (0.08) | (0.11) | |

| Constant | 59.19*** | 85.87*** | 79.87*** | 100.80*** | 99.64*** |

| (1.60) | (1.33) | (1.26) | (1.00) | (1.39) |

| Collateral source ratings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | 6.69*** | −4.01** | −2.72 | −1.94 | −5.43*** |

| (2.15) | (1.84) | (1.45) | (1.59) | (2.05) | |

| EYO | −0.16 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.13 |

| (0.10) | (0.08) | (0.06) | (0.07) | (0.09) | |

| CDR‐SB | 1.41*** | −2.76*** | −1.46*** | −1.02*** | −3.11*** |

| (0.50) | (0.43) | (0.34) | (0.37) | (0.48) | |

| Sex | −5.38*** | −0.75 | −3.19*** | −2.94*** | −1.70 |

| (1.43) | (1.22) | (0.97) | (1.05) | (1.36) | |

| Education | −0.80*** | 0.21 | 0.77*** | 0.68*** | 0.86*** |

| (0.25) | (0.21) | (0.16) | (0.19) | (0.24) | |

| Mutation × EYO | 0.30** | −0.14 | −0.16 | −0.09 | −0.21 |

| (0.14) | (0.12) | (0.09) | (0.10) | (0.13) | |

| Constant | 58.55*** | 85.89*** | 78.56*** | 100.76*** | 101.17*** |

| (1.67) | (1.40) | (1.10) | (1.32) | (1.65) |

Note: **P < .05; ***P < .01.

Abbreviations: CDR‐SB, Clinical Dementia Rating‐Sum of Boxes; EYO, estimated years to onset; SE, standard error

The effects were largely the same using ratings from the collateral source (bottom panel of Table 2 and Figure 1). More importantly, there was a main effect of group on neuroticism (β = 6.69, SE = 2.15, P = .002, Cohen's d = 0.29), which was qualified by a group by EYO interaction (β = 0.30, SE = 0.14, P = .03, Cohen's d = 0.20). Once again, the simple slopes indicated that MCs tended to increase in neuroticism across EYO and NCs decreased; however, neither of these comparisons were statistically significant. Finally, MCs were rated as lower on conscientiousness relative to NCs (β = ‐5.42, SE = 2.05, P = .008, Cohen's d = –0.24); however, the group by EYO interaction did not reach significance (P = .10). Extraversion also exhibited a group difference such that MCs were rated as lower on this trait relative to NCs (P < .05, Cohen's d = –0.20); however, the group by EYO interaction was not significant.

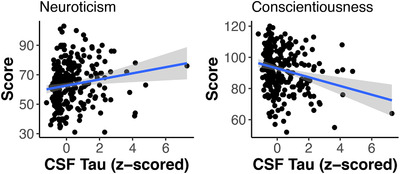

4.2. Question 2: Relationship between personality and biomarkers in mutation carriers at baseline

Only neuroticism and conscientiousness showed a significant and consistent group difference due to mutation status in the self‐report data, so we restricted our subsequent analyses of MCs and biomarkers to only these personality factors. After including terms for baseline EYO, CDR‐SB, sex, and education, both self‐reported neuroticism and conscientiousness were related to levels of AD biomarkers measured in the CSF. Specifically, higher levels of total tau correlated with higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of conscientiousness (β = 2.10, SE = 0.95, P = .03, Cohen's d = 0.28; β = –2.05, SE = 0.86, P = .02, Cohen's d = –0.30 respectively). These effects are shown in Figure 2. Similar relationships were shown between p‐tau and neuroticism (β = 2.42, SE = 1.01, P = .02, Cohen's d = 0.32), and conscientiousness (β = –2.82, SE = 0.92, P = .003, Cohen's d = –0.39). No informant reported measures were significantly associated with AD pathology. Full model output is provided in Table 3.

FIGURE 2.

Higher levels of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tau correlate with higher levels of self‐reported neuroticism at baseline in autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease (ADAD) mutation carriers (N = 257, P = .03) and lower levels of self‐reported conscientiousness (P = .02)

TABLE 3.

Beta weights (SEs) from models predicting neuroticism and conscientiousness from AD biomarkers at baseline

| Variables | Neuroticism | Conscientiousness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self‐ratings | ||||||||

| Aβ1‐42 | 1.65 (1.10) | −0.93 (0.99) | ||||||

| Tau | 2.10** (0.95) | −2.05** (0.86) | ||||||

| pTau | 2.42** (1.01) | −2.82** (0.92) | ||||||

| PiB | −0.38 (1.02) | −1.50 (0.96) | ||||||

| EYO | 0.13 (0.12) | −0.04 (0.11) | −0.08 (0.11) | 0.09 (0.12) | −0.15 (0.11) | −0.04 (0.10) | 0.02 (0.10) | −0.03 (0.11) |

| CDR‐SB | 0.19 (0.58) | −0.23 (0.59) | −0.10 (0.58) | 0.19 (0.50) | −0.96 (0.52) | −0.62 (0.54) | −0.70 (0.52) | −0.61 (0.47) |

| Sex | −1.59 (1.86) | −1.44 (1.82) | −1.63 (1.83) | −2.74 (1.86) | −3.35** (1.65) | −3.39** (1.64) | −3.23** (1.63) | −3.16 (1.72) |

| Education | −0.70** (0.31) | −0.64** (0.30) | −0.67** (0.30) | −0.47 (0.33) | 0.66** (0.28) | 0.64** (0.28) | 0.67** (0.27) | 0.52 (0.31) |

| Collateral source ratings | ||||||||

| Aβ1−42 | −0.17 (1.16) | −2.01 (1.19) | ||||||

| Tau | 1.84 (0.99) | −0.44 (1.02) | ||||||

| pTau | 1.47 (1.05) | −0.73 (1.09) | ||||||

| PiB | −1.36 (1.08) | −1.89 (1.08) | ||||||

| EYO | 0.14 (0.13) | 0.10 (0.11) | 0.09 (0.12) | 0.25** (0.13) | 0.02 (0.13) | −0.08 (0.11) | −0.06 (0.12) | −0.02 (0.13) |

| CDR‐SB | 1.59*** (0.59) | 1.16 (0.61) | 1.35** (0.60) | 1.33** (0.53) | −3.42*** (0.60) | −3.35*** (0.63) | −3.36*** (0.61) | −3.01*** (0.52) |

| Sex | −5.01*** (1.93) | −5.07*** (1.89) | −5.28*** (1.91) | −4.26** (1.98) | 0.02 (1.95) | −0.01 (1.93) | 0.12 (1.94) | −0.91 (1.96) |

| Education | −0.94*** (0.32) | −0.91*** (0.32) | −0.95*** (0.32) | −0.71** (0.35) | 0.92*** (0.33) | 0.89*** (0.33) | 0.88*** (0.33) | 0.89*** (0.35) |

Note: **P < .05; ***P < .01.

Abbreviations: Aβ42, amyloid beta 42; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CDR‐SB, Clinical Dementia Rating‐Sum of Boxes; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EYO, estimated years to onset; PIB, Pittsburgh compound B; pTau, phosphorylated tau; SE, standard error

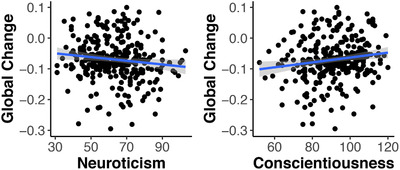

4.3. Question 3: Does personality predict decline in cognition?

In terms of self‐reported personality, levels of neuroticism were not significantly correlated with either baseline cognitive performance or rates of longitudinal cognitive decline. Furthermore, although conscientiousness was not related to cognition at baseline, it was associated with rates of cognitive decline (β = 0.002, SE = 0.001, P = .03, Cohen's d = 0.41), indicating that individuals with higher levels of conscientiousness demonstrated slower rates of change in cognition. These effects are plotted in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Correlation between baseline self‐reported neuroticism and conscientiousness (N = 304) on rate of change in a global cognitive composite in autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease (ADAD) mutation carriers. Lower levels of conscientiouness correspond to faster rates of decline (P = .03). The relationship between cognitive decline and neuroticism was not significant

Turning to the collateral reports, neuroticism correlated with cognitive change (β = –0.002, SE = 0.001, P = .003, Cohen's d = –0.30), indicating that higher neuroticism correlates with faster rates of decline. Conscientiousness was also correlated with rates of decline (β = 0.002, SE = 0.001, P = .01, Cohen's d = 0.45), again indicating that individuals higher in conscientiousness declined more slowly in cognition. Full model output is provided in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Beta weights (SEs) predicting longitudinal cognitive change from conscientiousness and neuroticism

| Cognitive composite | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 0.03 (0.06) | −0.30*** (0.10) | 0.06 (0.04) | −0.30*** (0.09) |

| N (Self) | −0.004 (0.002) | |||

| C (Self) | 0.004 (0.003) | |||

| N (CS) | −0.004 (0.003) | |||

| C (CS) | 0.004 (0.002) | |||

| Baseline EYO | −0.03*** (0.004) | −0.03*** (0.004) | −0.04*** (0.004) | −0.03*** (0.004) |

| Baseline CDR‐SB | −0.28*** (0.02) | −0.27*** (0.02) | −0.27*** (0.02) | −0.26*** (0.02) |

| Sex | −0.25*** (0.07) | −0.23*** (0.07) | −0.27*** (0.08) | −0.24*** (0.07) |

| Education | 0.05*** (0.01) | 0.05*** (0.01) | 0.05*** (0.01) | 0.05*** (0.01) |

| Time × N (Self) | −0.002 (0.001) | |||

| Time × C (Self) | 0.002** (0.001) | |||

| Time × N (CS) | −0.002*** (0.001) | |||

| Time × C (CS) | 0.002** (0.001) | |||

| Constant | −1.06*** (0.25) | −1.67*** (0.28) | −1.11*** (0.28) | −1.71*** (0.26) |

Note: N, Neuroticism; C, Conscientiousness, **P < .05; ***P < .01.

Abbreviations: CDR‐SB, Clinical Dementia Rating‐Sum of Boxes; CS, collateral source; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EYO, estimated years to onset; PIB, Pittsburgh compound B; SE, standard error

5. DISCUSSION

The ultimate goal of this work was to determine whether personality factors are associated with disease onset in ADAD. To this end, our analyses revealed several important findings. First, at baseline, both self‐reported neuroticism and conscientiousness exhibited differential trajectories across the EYO spectrum as a function of mutation status. Neuroticism tended to increase and conscientiousness to decrease in mutation carriers with the reverse being true in the NC. This pattern is consistent with prior reports of neuroticism and conscientiousness producing the largest differences among those at increased risk for late‐onset AD, 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 suggesting that our findings can be generalized to the more common, sporadic form of the disease. We also observed a relationship between personality and EYO in NCs. As these participants do not carry a mutation and would not be expected to harbor substantial AD pathology, it is clear then that both neuroticism and conscientiousness can change in healthy aging, which is consistent with prior reports. 6 , 40 This raises the possibility that normal age‐related personality changes in the MCs may be attenuated or offset by declines that can be attributed to disease processes.

We hypothesized that informant reports of personality might be more sensitive to change than self‐ratings due to changes in insight with advancing disease. 12 Counter to our hypothesis, reports from the collateral source generally converged with self‐reports and in some cases (eg, in terms of correlations with CSF markers) were actually less sensitive markers. Possibly, the differences in age across the two samples may have contributed to this pattern. Specifically, the Duchek et al. 12 sample included much older participants (mean age = 75 years) than the participants in the current analyses (mean age = 37) and this may have contributed to differences in the knowledge of the collateral source. We also conducted post‐hoc analyses correlating self‐rated personality with AD biomarkers while controlling for the cognitive composite score. The results were unchanged, suggesting that baseline differences in cognition are not accounting for baseline differences in personality. Taken together, these results suggest that differences in neuroticism and in conscientiousness might indeed be a sensitive, non‐cognitive marker of disease stage (ie, pathology burden) in ADAD.

A critical component of the current study is the relationship of in vivo markers of AD pathology to personality change. Results suggest that changes in neuroticism and conscientiousness appear specific to neurodegenerative processes in AD. Self‐reported levels of both factors were related to pathological markers of neurodegeneration measured in the CSF (total tau and p‐tau), suggesting that differences in these two important personality characteristics are associated with high levels of AD‐related neurodegeneration. Because our models included terms for CDR scores as well as EYO, these relationships were independent of overt clinical markers of disease progression. We did not observe correlations between amyloid markers (Aβ42 and Pittsburgh compound B [PIB]) and personality traits. It is well established that amyloid becomes abnormal well before active neurodegenerative processes ensue, 1 so this pattern indicates that personality may change relatively late in the disease. Furthermore, other studies have shown a relationship between neuroticism and tau deposition, 20 and volumetric changes. 41 Together, these findings implicate tau pathology as a key correlate of preclinical personality change. Future research should directly examine correlations between regional tau deposition and levels of reported neuroticism in DIAN.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, self‐rated conscientiousness as well as informant reported neuroticism and conscientiousness correlated with the magnitude of cognitive change. Specifically, individuals higher on neuroticism and lower on conscientiousness declined more quickly on a global cognitive composite compared to individuals with the opposite personality profile. We consider two ways to interpret this pattern. First, it is possible that personality independently contributes to cognitive change, in a manner akin to cognitive reserve (ie, protects against detrimental effects of accumulating pathology). The second possibility is that AD pathology (specifically neurodegeneration) produces differences in both personality traits and cognition. Under the latter scenario, CSF tau would be expected to fully mediate the personality–cognition relationship. To adjudicate among these possibilities, we conducted post‐hoc supplementary analyses in which both a personality trait and CSF tau were included as predictors of decline. Critically, with both variables in the model, only tau predicted decline and the influence of personality (both neuroticism and conscientiousness) were no longer significant. Thus, the relationship between personality and cognition is more likely due to the joint relationship with tau pathology.

In many studies of personality traits and cognition in dementia, it is difficult to firmly establish directionality of these relationships. Specifically, it is possible that personality traits demonstrate subtle change due to accumulating AD pathology. Conversely, it is possible that individuals with a specific personality profile (eg, highly conscientious and low in neuroticism) tend to engage in specific behaviors that encourage or prevent accumulation of pathology and mitigates the damaging influence of pathology on cognition. For example, highly neurotic individuals are prone to experience stress and anxiety and repeated exposure to stress has negative consequences for brain function. 42 Similarly, conscientiousness is in part defined by self‐discipline. High levels of this trait may encourage engagement in behaviors that promote health and wellness, 43 which may moderate structural damage in the brain. 44 Other facets of conscientiousness include “dutifulness” and “achievement striving” and hence highly conscientious individuals may be particularly motivated to exert greater effort during cognitive testing, which may produce artificially increased scores relative to a less motivated participant. A detailed investigation of specific personality facets and associated behaviors that moderate the observed relationships with cognitive function and pathology is warranted in future research.

There are a number of strengths of this study including a large prospective sample with a detailed panel of cognitive, personality, and biomarker data available, which provides for a comprehensive evaluation of the relationship between personality traits and AD pathology in a relatively young (and hence free of comorbid conditions) population. Despite the strengths of the study, it should be noted that the majority of participants have been followed for a total of two assessments over a 2‐year time frame. It is possible that the effects observed here will change once more follow‐up assessments become available. Furthermore, some individuals in DIAN are aware of their mutation status, and it is possible that having such knowledge will change the magnitude of personality change across mutation groups. In addition, although many of results were hypothesized a priori (ie, the relationships with neuroticism and conscientiousness), we did conduct a relatively large number of statistical tests, which may been seen as a potential limitation. Finally, our results are correlational only and thus the direction of causality (ie, does AD pathology change personality or does a certain personality profile predispose one to develop AD?) cannot be readily determined. Regardless, in our sample of DIAN participants, we found that neuroticism and conscientiousness correlated with years to symptom onset at the baseline assessment. At the same assessment, self‐reports of these measures correlated with levels of tau pathology in the CSF. Finally, there was initial evidence that changes in biomarkers precede differences in personality. Together these findings suggest that neuroticism and conscientiousness may hold utility in tracking disease progression in AD.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Alison Goate served on the scientific advisory board for Denali Therapeutics from 2015 to 2018. She has also served as a consultant for Biogen, AbbVie, Pfizer, GSK, Eisai, and Illumina. Dr. Benzinger reports grants, non‐financial support, and clinical trial participation involving Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly. She serves as an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Roche, Biogen, Jaansen, and Eisai. She reports unpaid consulting: Siemens, Eisai, ADMDx. She is on the Biogen speakers’ bureau. All of this is outside the scope of the current manuscript. Dr. Neil Graff‐Radford takes part in multicenter treatment trials funded by Novartis, AbbVie, Biogen, and Lilly. Dr. JC Morris is funded by NIH grants # P50AG005681, P01AG003991, P01AG026276, and UF1AG032438. Neither Dr. Morris nor his family owns stock or has equity interest (outside of mutual funds or other externally directed accounts) in any pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. No other conflicts are reported.

Aschenbrenner AJ, Petros J, McDade E, et al. Relationships between big‐five personality factors and Alzheimer's disease pathology in autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2020;12:e12038 10.1002/dad2.12038

Footnotes

Cohen's d was calculated using the following formula (2×t‐value)/sqrt(df). If degrees of freedom were not reported they were estimated based on reported sample size and the number of parameters included in the analysis models.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, et al, others . Clinical and biomarker changes in Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):795‐804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):207‐216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Price JL, McKeel DW, Buckles VD, et al. Neuropathology of nondemented aging: presumptive evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(7):1026‐1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(11):1006‐1012. 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCrae RR, John OP. An introduction to the five‐factor model and its applications. J Pers. 1992;60(2):175‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roberts BW, Walton KE, Viechtbauer W. Patterns of mean‐level change in personality traits across the life course: a meta‐analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(1):1‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turiano NA, Pitzer L, Armour C, Karlamangla A, Ryff CD, Mroczek DK. Personality trait level and change as predictors of health outcomes: findings from a national study of Americans (MIDUS). J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67B(1):4‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hakulinen C, Elovainio M, Pulkki‐R\textbackslasha aback L, Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, Jokela M. Personality and depressive symptoms: individual participant meta‐analysis of 10 cohort studies. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(7):461‐470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jokela M, Batty GD, Nyberg ST, et al. Personality and all‐cause mortality: individual‐participant meta‐analysis of 3947 deaths in 76,150 adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(5):667‐675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Robins Wahlin T‐B, Byrne GJ. Personality changes in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Intl J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(10):1019‐1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pocnet C, Rossier J, Antonietti J‐P, Gunten A. Personality traits and behavioral and psychological symptoms in patients at an early stage of Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(3):276‐283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duchek JM, Balota DA, Storandt M, Larsen R. The power of personality in discriminating between healthy aging and early‐stage Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Socl Sci. 2007;62(6):P353‐P361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rubio MM, Antonietti J, Donati A, Rossier J, Von Gunten A. Personality traits and behavioural and psychological symptoms in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;35(1‐2):87‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duberstein PR, Chapman BP, Tindle HA, et al. Personality and risk for Alzheimer's disease in adults 72 years of age and older: a 6‐year follow‐up. Psychol Aging. 2011;26(2):351‐362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duchek JM, Aschenbrenner AJ, Fagan AM, Benzinger TLS, Morris J, Balota DA. The relation between personality and biomarkers in sensitivity and conversion to Alzheimer type dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;11:1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Terracciano A, Iacono D, O'Brien RJ, et al. Personality and resilience to Alzheimer's disease neuropathology: a prospective autopsy study. Neurobio Aging. 2013;34(4):1045‐1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang H‐X, Karp A, Herlitz A, et al. Personality and lifestyle in relation to dementia incidence. Neurology. 2009;72(3):253‐259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the national institute on aging‐Alzheimer's association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011;7(3):263‐269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tautvydaitė D, Antonietti J, Henry H, von Gunten A, Popp J. Relations between personality changes and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease pathology. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;90:12‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schultz SA, Gordon BA, Mishra S, et al. Association between personality and tau‐PET binding in cognitively normal older adults. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019. 10.1007/s11682-019-00163-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Snitz BE, Weissfeld LA, Cohen AD, et al. Subjective cognitive complaints, personality and brain amyloid‐beta in cognitively normal older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(9):985‐993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goodwin RD, Friedman HS. Health status and the five‐factor personality traits in a nationally representative sample. J Health Psychol. 2006;11(5):643‐654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ryman DC, Acosta‐Baena N, Aisen PS, et al, and the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network . Symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Neurology. 2014;83(3):253‐260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cairns NJ, Perrin RJ, Franklin EE, et al, the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Neuropathologic assessment of participants in two multi‐center longitudinal observational studies: the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN): neuropathologic assessment in ADNI and DIAN. Neuropathology. 2015;35(4):390‐400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Storandt M, Balota DA, Aschenbrenner AJ, Morris JC. Clinical and psychological characteristics of the initial cohort of the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN). Neuropsychology. 2014;28(1):19‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412‐2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnson JA. Measuring thirty facets of the five factor model with a 120‐item public domain inventory: development of the IPIP‐NEO‐120. J ResPers. 2014;51:78‐89. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini‐mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wechsler D, (1987). Manual: Wechsler Memory Scale‐ Revised. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wechsler D, (1981). Manual: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale‐ Revised. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang G, Berry S, Xiong C, et al, For the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Trials Unit . A novel cognitive disease progression model for clinical trials in autosomal‐dominant Alzheimer's disease. Stat Med. 2018;37(21):3047‐3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fagan AM, Xiong C, Jasielec MS, et al. Longitudinal change in CSF biomarkers in autosomal‐dominant Alzheimer's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(226):226ra30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer's disease with Pittsburgh compound‐B: imaging Amyloid in AD with PIB. Ann Neurolo. 2004;55(3):306‐319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eisenstein SA, Koller JM, Piccirillo M, et al. Characterization of extrastriatal D2 in vivo specific binding of [18F](N‐methyl) benperidol using PET. Synapse. 2012;66(9):770‐780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rousset OG, Ma Y, Evans AC. Correction for partial volume effects in PET: principle and validation. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(5):904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rowland DJ, Garbow JR, Laforest R, Snyder AZ. Registration of [18F] FDG microPET and small‐animal MRI. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32(6):567‐572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed‐effects models using lme4 . J Stat Software. 2015;67(1). 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mõttus R, Realo A, Vainik U, Allik J, Esko T. Educational attainment and personality are genetically intertwined. Psychol Sci. 2017;28(11):1631‐1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. South SC, Jarnecke AM, Vize CE. Sex differences in the Big Five model personality traits: a behavior genetics exploration. J Res Pers. 2018;74:158‐165. [Google Scholar]

- 40. McCrae RR, Terracciano A. Universal features of personality traits from the observer's perspective: data from 50 cultures. J Pers Soc Psycho. 2005;88(3):547‐561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jackson J, Balota DA, Head D. Exploring the relationship between personality and regional brain volume in healthy aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(12):2162‐2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Radley JJ, Morrison JH. Repeated stress and structural plasticity in the brain. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4(2):271‐287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bogg T, Roberts BW. Conscientiousness and health‐related behaviors: a meta‐analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(6):887‐919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bugg JM, Head D. Exercise moderates age‐related atrophy of the medial temporal lobe. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(3):506‐514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]