Abstract

Background:

As surgery is rarely recommended, there is minimal literature comparing the outcomes of surgery and chemoradiation in N3 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We examined the outcomes of definitive chemoradiation versus multimodality therapy, including surgery, for patients with clinical and pathologic N3 NSCLC.

Methods:

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) was used to identify patients with (1) cT1–3N3M0 NSCLC and (2) cT1–3NxM0 with pN3 NSCLC who were treated with either definitive chemoradiation (CR) or surgery (S) between 2004–2015. A 1:1 propensity score-matched analysis was used to compare outcomes for both treatment groups in each analysis. The primary outcome was overall survival.

Results:

In 935 matched patient pairs with cN3 NSCLC, S was associated with worse survival (hazard ratio [HR] 1.52; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.12–2.05) compared to CR at 6 months, but was associated with a significant survival benefit after 6 months (HR 0.54; 95%CI 0.47–0.63) in multivariable analysis. In 281 pairs of patients with pN3 NSCLC, S had similar survival compared to CR at 6 months (HR 1.71; 95%CI 0.92–3.19), but was associated with improved survival after 6 months (HR 0.76; 95%CI 0.58–0.99). The complete resection rate was 80% and 73% for patients with cN3 and pN3 disease, respectively.

Conclusion:

In patients with clinical or pathologic N3 NSCLC, surgery is associated with similar or worse short-term but improved long-term survival compared to chemoradiation. In a selected group of patients with N3 NSCLC, surgery may have a role in multimodal therapy.

Central Message

In patients with cN3 or pN3 NSCLC, surgery is associated with improved long-term survival compared to chemoradiation.

Introduction

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines recommend definitive concurrent chemoradiation as initial therapy for N3 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)1,2. Surgery is not recommended for N3 disease, which has historically been considered unresectable. However, there is minimal literature on the outcomes of surgery for these patients. Several prospective phase II trials of surgery following chemotherapy or chemoradiation in stage IIIB NSCLC have been published, but these are limited by small subsets of patients with N3 disease ranging from 7 to 32 patients, variable induction regimens, and variable study design with several excluding patients with supraclavicular node involvement3–12. These prospective studies rarely contained subgroup analyses of patients with N3 disease, but showed that patients with stage IIIB lung cancer could undergo surgery with a high complete resection rate, up to 81%4, and with acceptable median survival ranging from 138 to 295 months. Importantly, these prospective studies demonstrated that patients with clinical stage IIIB disease experience a high rate of pathologic nodal downstaging with induction therapy, and that recurrence was both distant and locoregional, suggesting that there is a role for definitive local control.

There are no prospective trials and scant observational studies13–15 comparing chemoradiation to surgery in patients with clinical stage IIIB NSCLC, including those with cN3 disease. There are no studies examining the outcomes of patients with pathologic N3 disease. The management of patients with limited N3 disease who are otherwise operable and demonstrate response to systemic therapy is not clear, and it is possible that these patients may be treated in a similar manner as operable stage IIIA (N2) NSCLC with acceptable short- and long-term results. We performed a retrospective cohort study examining the outcomes of patients with cN3 and pN3 NSCLC undergoing surgery vs. chemoradiation. Given the high incidence of pathologic nodal downstaging and locoregional recurrence in patients with stage IIIB NSCLC, we hypothesized that patients with cN3 NSCLC may experience a survival benefit with surgery compared to definitive chemoradiation. However, we hypothesized that patients with pathologic N3 disease after resection would not have a survival benefit compared to patients with N3 disease who received chemoradiation alone.

Methods

Data Source

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) is a joint effort of the American Cancer Society and the American College of Surgeons, and contains data collected by certified tumor registrars in 1500 centers. It includes data regarding approximately 80% of cancers diagnosed and treated annually in the United States16.

Patient Selection

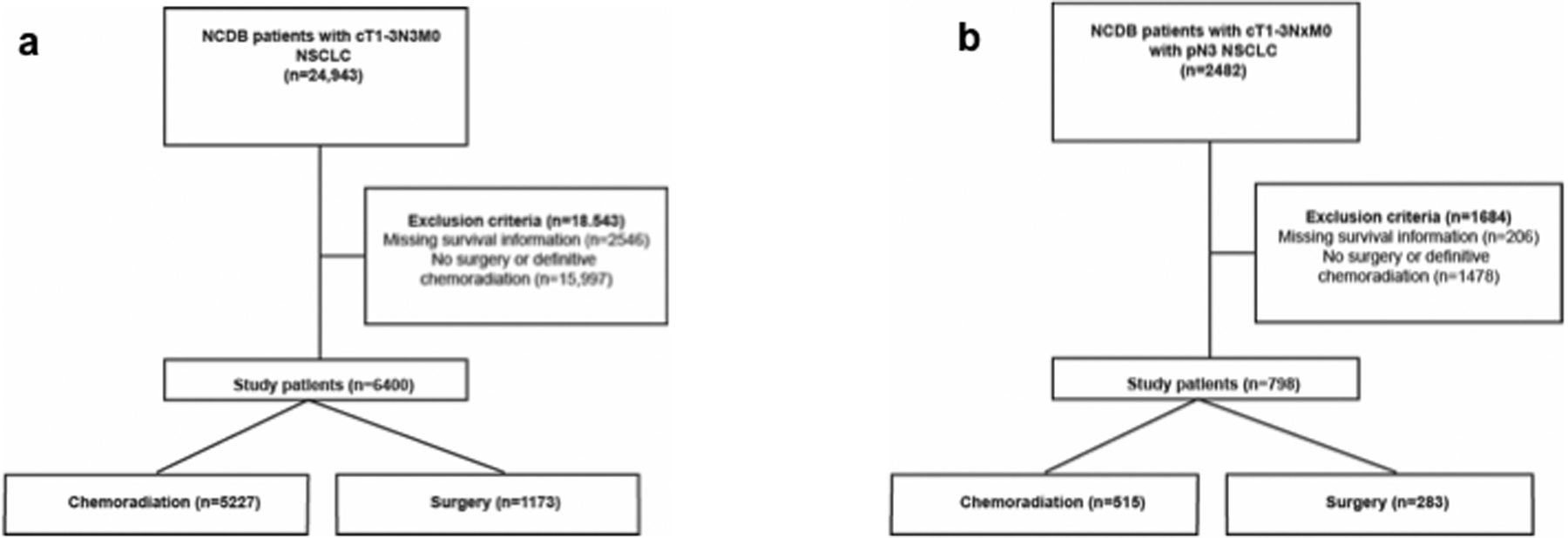

This study was deemed exempt by our Institutional Review Board. In the first part of the study, patients with AJCC 8th Edition clinical T1–3N3M0 NSCLC were identified in the NCDB (2004–2015). Patients with missing survival, staging, or treatment information were excluded (Figure 1A). Patients receiving chemoradiation who were not offered surgery due to poor performance status were also excluded, as were patients who received surgery more than six months after chemoradiation because of the possibility of a salvage procedure. In the second part of the study, patients with clinical T1–3NxM0 NSCLC with pathologic N3 disease were identified. The same exclusion criteria applied (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Patient selection scheme for (a) clinical N3 and (b) pathologic N3 parts of the study.

Patients were grouped by treatment: surgery (S) or definitive chemoradiation (CR). Surgery was defined as any operation, including sublobar and lobar resections. While a lobar resection is considered most appropriate for patients with NSCLC, not all patients can tolerate lobectomy. In order to place the burden of proof on patients undergoing surgery, we included all patients who received a lung resection regardless of type of surgery or receipt of perioperative chemotherapy or radiation in order to obtain the most conservative estimate of the effect of surgery on survival. We performed subgroup analyses on patients receiving lobar resection alone and those receiving multimodal therapy including surgery. Patients who received perioperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy as well as those who received no perioperative therapy were included. The NCDB does not contain information on re-staging after induction therapy. Definitive chemoradiation was defined as administration of chemotherapy and radiation of 60.0 Grey (Gy) or more, in concordance with the NCCN guidelines. Patients who received either sequential or concurrent chemoradiation were included because not all patients can tolerate concurrent chemoradiation. While the NCDB does not explicitly code invasive mediastinal staging, a subset of patients who did not receive surgery have pathologic nodal staging recorded in addition to clinical TNM staging, suggesting that the pathologic stage for these patients reflects the findings of invasive nodal staging. Since the second part of the study focused on patients with proven N3 disease, only patients with cNx-pN3 disease receiving definitive chemoradiation were included. Pathologic nodal downstaging is defined as a lower pathologic nodal stage following surgery compared to initial clinical nodal stage. Since the NCDB does not catalogue restaging after neoadjuvant therapy, any downstaging that occurred as a result of neoadjuvant therapy would only be reflected in the postoperative pathologic stage recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Background characteristics between patients in each group were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum and Pearson’s chi-squared tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. To minimize differences between the study groups, a propensity score-matched analysis was performed in each part of the study using patient and tumor-related variables including age, sex, race, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity condition (CDCC) score, year of diagnosis, insurance status, treatment at an academic center, urban or rural status, histology, and tumor size (T stage). A 1:1 nearest-neighbor algorithm17 was used that utilizes a series of logistic regressions to match control and treatment groups on distance; we used a caliper of 0.15 to eliminate differences and ensure a mean standardized difference ≤ 0.1 for each variable18,19. We have reported the mean standardized differences in Tables 1 and 4. For the analysis of pathologic N3 disease, clinical nodal status was also included in both the multivariable regression and for propensity matching.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of propensity score-matched patients with cN3 non-small cell lung cancer grouped by treatment

| Chemoradiation (n=935) (%) | Surgery (n=935) (%) | Std Mean Difference | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, median) | 67(59–74) | 67(59–74) | 0.01 | 0.98 |

| Sex (female) | 405(43) | 402(43) | 0.07 | 0.93 |

| Race | 0.86 | |||

| White | 818(88) | 811(87) | ||

| Black | 95(10) | 99(11) | 0.01 | |

| Other | 22(2) | 25(3) | 0.02 | |

| Year of diagnosis, median (inter-quartile range) | 2010(2007–2013) | 2010(2008–2012) | −0.007 | 0.80 |

| CDCC Score | 0.75 | |||

| 0 | 526(56) | 519(56) | ||

| 1 | 274(29) | 288(31) | 0.03 | |

| 2+ | 135(14) | 128(14) | −0.02 | |

| Insurance status | 0.65 | |||

| Private | 339(36) | 331(35) | ||

| Government | 562(60) | 576(62) | 0.03 | |

| None | 34(4) | 28(3) | −0.04 | |

| Facility location | 0.62 | |||

| Metro | 701(75) | 711(76) | ||

| Urban | 184(20) | 169(18) | −0.04 | |

| Rural | 50(5) | 55(6) | 0.02 | |

| Academic center | 336(36) | 344(37) | 0.02 | 0.74 |

| Tumor size, median (mm) | 32(22–44) | 30(20–45) | −0.05 | 0.11 |

| Histology | 0.87 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 446(48) | 449(48) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 353(38) | 358(38) | 0.01 | |

| Other | 136(15) | 128(14) | −0.02 | |

| Perioperative chemotherapy | 549(59) | N/A | N/A |

Table 4.

Background characteristics of propensity score-matched patients with pN3 non-small cell lung cancer grouped by treatment

| Chemoradiation (n=221) (%) | Surgery (n=221) (%) | Std Mean Difference | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, median) | 66(58–72) | 65(57–71) | −0.06 | 0.58 |

| Sex (female) | 96(43) | 105(48) | −0.08 | 0.45 |

| Race | 0.96 | |||

| White | 192(87) | 192(87) | ||

| Black | 22(10) | 21(10) | −0.01 | |

| Other | 7(3) | 8(4) | 0.02 | |

| Year of diagnosis, median (inter-quartile range) | 2010(2007–2012) | 2010(2007–2012) | −0.05 | 0.59 |

| CDCC Score | 0.99 | |||

| 0 | 137(62) | 138(62) | ||

| 1 | 62(28) | 62(28) | 0.00 | |

| 2+ | 22(10) | 21(10) | −0.01 | |

| Insurance status | 0.96 | |||

| Private | 89(40) | 88(40) | ||

| Government | 123(56) | 125(57) | 0.02 | |

| None | 9(4) | 8(4) | −0.02 | |

| Facility location | 0.24 | |||

| Metro | 189(86) | 176(80) | ||

| Urban | 25(11) | 33(15) | 0.10 | |

| Rural | 7(3) | 12(5) | 0.10 | |

| Academic center | 82(37) | 86(39) | 0.04 | |

| Tumor size, median (mm) | 28(18–39) | 30(19–40) | −0.01 | 0.77 |

| Histology | 0.85 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 141(64) | 139(63) | 0.44 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 60(27) | 54(24) | −0.06 | |

| Other | 20(9) | 28(13) | 0.10 | |

| Perioperative chemotherapy | N/A | 163(74) | N/A | N/A |

The primary outcome was overall survival, which was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier and Cox Proportional Hazards estimates. In both parts of the study, the Kaplan-Meier curves intersected at about 6–9 months, and the proportional hazards assumption was violated (Schoenfeld residual p<0.05). To resolve this, the cohorts in each analysis were divided into two before the point of intersection (six months) and modeled as time-varying coefficients in a single multivariable Cox model20. The following subgroup analyses were performed: cohort limited to patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy (cN3), lobar resection (cN3 and pN3), an R0 resection (pN3), or perioperative chemotherapy (pN3).

In survival analyses, missing data were handled with complete case analysis for each variable included in the multivariable Cox models. In other descriptive statistics such as pathologic nodal staging, the fraction of missing data is reported for each group. All statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.5 for Mac (Vienna, Austria). A p value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical N3 Disease

A total of 6400 patients met study criteria: 5227 underwent chemoradiation (82%) and 1173 underwent surgery (18%). Compared to CR, S patients had a lower T stage, were less likely to have adenocarcinoma, had more comorbidities, and were more likely to be treated at an academic medical center (Supplemental Table 1). In the S group, 616 patients (53%) received perioperative therapies: 209 (18%) received induction chemotherapy with or without radiation and 407 (37%) received adjuvant chemotherapy. The most common operation was lobectomy, followed by wedge resection, and pneumonectomy. A margin-negative (R0) resection was achieved in 80% of patients. The median survival was 20 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 20–21) for CR and 35 months (95%CI 32–39) for S (Figure 2A). In a multivariable Cox model, S was associated with worse survival compared to CR in the first 6 months (hazard ratio [HR] 1.34; 95%CI 1.07–1.67; p=0.01). After 6 months, there was a significant overall survival benefit with S compared CR (HR 0.54; 95%CI 0.48–0.61; p<0.001). Amongst 5227 CR patients with cN3 disease, only 550 had a pathologic nodal stage recorded (30% missing and 59% pNx): 458 (83%) had pN3 disease, 68 (12%) pN2, 14 (3%) pN1, and 10 (2%) pN0. Amongst S patients (6% missing and 26% pNx), 174 (16%) had pN3, 133 (12%) pN2, 109 (10%) pN1, and 397 (36%) pN0 disease.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for propensity score-matched patients with clinical N3 NSCLC, grouped by treatment of chemoradiation vs. surgery, with log-rank test reported as a p-value and numbers at risk for each group provided beneath the figure. Y axis refers to the percentage of patients alive, and X axis the time, in years, from diagnosis.

A total of 935 pairs of patients were identified by 1:1 propensity score matching. Background characteristics of patients in each group are summarized in Table 1. The median survival was 20 months (95%CI 18–22) and 34 months (95%CI 30–39) for CR and S patients, respectively (Figure 2B). In multivariable analysis, S was associated with worse survival compared to CR within the first six months of diagnosis, but after six months, surgery was associated with a significant benefit in overall survival compared to CR (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards model for independent predictors of survival for propensity score-matched patients with cN3 non-small cell lung cancer

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Hazard Ratio | Lower | Upper | p-value |

| Age (per year) | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | <0.001 |

| Female sex (reference: male) | 0.96 | 0.86 | 1.07 | 0.46 |

| Race (reference: White) | ||||

| Black | 1.05 | 0.87 | 1.26 | 0.61 |

| Other | 1.09 | 0.76 | 1.56 | 0.64 |

| Charleson-Deyo Comorbidity Index (reference: 0) | ||||

| 1 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 1.28 | 0.05 |

| 2+ | 1.26 | 1.08 | 1.49 | 0.004 |

| Year of diagnosis (per year) | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.002 |

| Insurance status (reference: private) | ||||

| Government | 1.09 | 0.94 | 1.25 | 0.25 |

| None | 1.01 | 0.72 | 1.40 | 0.97 |

| Facility location (reference: metro) | ||||

| Urban | 1.00 | 0.87 | 1.15 | 0.98 |

| Rural | 1.21 | 0.96 | 1.52 | 0.11 |

| Academic center | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.98 | 0.02 |

| Tumor size | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.005 |

| Histology (ref: adenocarcinoma) | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 0.95 | 0.83 | 1.07 | 0.38 |

| Other | 1.18 | 1.01 | 1.39 | 0.04 |

| Treatment (reference: chemoradiation) | ||||

| Surgery (<=6 months) | 1.52 | 1.12 | 2.05 | 0.006 |

| Surgery (after 6 months) | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.63 | <0.001 |

Only 209 (18%) patients undergoing surgery received induction chemotherapy, suggesting that a significant fraction of patients with cN3 disease were downstaged by invasive nodal assessment. We therefore performed a propensity score-matched subgroup analysis of only patients receiving surgery following induction therapy, presuming these patients had pathologically demonstrated N2 or N3 disease at the time of presentation. S and CR patients had a median survival of 64 months (95%CI 51–73) and 21 months (95%CI 19–28), respectively. In both unadjusted (Figure 3) and adjusted analysis, patients undergoing surgery with induction therapy experienced better survival compared to those receiving chemoradiation (HR 0.41; 95%CI 0.31–0.55; p<0.001). Of S patients (7% missing, 20% pNx), 131 (86%) had a lower pathologic N stage compared to initial clinical stage, with 81 (53%) demonstrating pN0 disease.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for propensity score-matched patients with clinical N3 NSCLC, grouped by treatment of chemoradiation vs. surgery following induction therapy with log-rank test reported as a p-value and numbers at risk for each group provided beneath the figure. Y axis refers to the percentage of patients alive, and X axis the time, in years, from diagnosis.

In a separate subgroup analysis including only patients receiving a lobar resection, 556 matched pairs of patients were identified. Within the first six months, there was no difference in survival between S and CR (HR 1.03; 95%CI 0.68–2.45; p=0.88), but S was associated with improved survival compared to CR after six months (HR 0.42; 95%CI 0.35–0.51; p<0.001).

Pathologic N3 Disease

A total of 798 patients with pN3 disease met study criteria, of whom 515 (65%) and 283 (35%) underwent CR and S, respectively. The clinical nodal stage of each treatment group is summarized in Table 3. Compared to CR, S patients were more likely to be diagnosed earlier, be treated in a metropolitan area, and be less likely to have adenocarcinoma (Supplemental Table 2). Of S patients, 184 (66%) underwent perioperative chemotherapy: 31 (12%) received induction chemotherapy and 153 (55%) received adjuvant chemotherapy. The most common operation was lobectomy, followed by wedge resection and pneumonectomy. The R0 resection rate was 73%. The median survival for CR and S patients was 22 (95%CI 19–25) and 24 (95%CI 21–29) months, respectively (Figure 4A). In multivariable Cox regression, S was associated with worse survival compared to CR within the first six months (HR 1.69; 95%CI 1.00–2.83; p=0.05). Beyond six months, surgery was associated with a significant survival benefit (HR 0.73; 95%CI 0.58–0.91; p=0.01).

Table 3.

Clinical nodal staging of patients with pN3 NSCLC, grouped by treatment

| Clinical N Stage | Chemoradiation (n=515) (%) | Surgery (n=283) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10(2) | 43(15) |

| 1 | 5(1) | 19(7) |

| 2 | 28(5) | 39(14) |

| 3 | 458(89) | 174(61) |

| X | 14(3) | 8(3) |

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for propensity score-matched patients with pathologic N3 NSCLC, grouped by treatment of chemoradiation vs. surgery with log-rank test reported as a p-value and numbers at risk for each group provided beneath the figure. Y axis refers to the percentage of patients alive, and X axis the time, in years, from diagnosis.

A 1:1 propensity score-matched analysis identified 221 pairs of patients with pN3 disease. The background characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 4. The median survival for CR and S patients was 22 (95%CI 18–28) and 24 (95%CI 19–29) months, respectively (Figure 4B). In multivariable regression, surgery was not associated with a significant survival benefit compared to CR within the first six months after diagnosis (Table 5). However, surgery was associated with a significant survival benefit after six months.

Table 5.

Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards model for independent predictors of survival for propensity score-matched patients with pN3 non-small cell lung cancer

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Hazard Ratio | Lower | Upper | p-value |

| Age (per year) | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.22 |

| Female sex (reference: male) | 0.97 | 0.76 | 1.22 | 0.77 |

| Race (reference: White) | ||||

| Black | 1.06 | 0.72 | 1.57 | 0.76 |

| Other | 1.14 | 0.57 | 2.28 | 0.71 |

| Charleson-Deyo Comorbidity Index (reference: 0) | ||||

| 1 | 1.05 | 0.81 | 1.36 | 0.72 |

| 2+ | 1.46 | 1.00 | 2.14 | 0.05 |

| Year of diagnosis (per year) | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 0.002 |

| Insurance status (reference: private) | ||||

| Government | 1.01 | 0.74 | 1.38 | 0.96 |

| None | 0.71 | 0.35 | 1.45 | 0.34 |

| Facility location (reference: metro) | ||||

| Urban | 0.92 | 0.65 | 1.29 | 0.62 |

| Rural | 0.90 | 0.50 | 1.63 | 0.74 |

| Academic center | 0.86 | 0.68 | 1.09 | 0.22 |

| Tumor size | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.16 |

| Histology (ref: adenocarcinoma) | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1.08 | 0.83 | 1.42 | 0.56 |

| Other | 0.96 | 0.65 | 1.41 | 0.84 |

| Treatment (reference: chemoradiation) | ||||

| Surgery (<=6 months) | 1.71 | 0.92 | 3.19 | 0.09 |

| Surgery (after 6 months) | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.99 | 0.045 |

In a subgroup analysis of 136 matched pairs of patients who received perioperative chemotherapy, there was no difference in survival between S and CR (HR 1.00; 95%CI 0.75–1.34; p=0.99). In a separate analysis of patients who underwent lobar resection, there was no difference in survival between S and CR within six months (HR 1.07; 95%CI 0.49–2.37; p=0.86), but S was associated with improved survival after six months (HR 0.64; 95%CI 0.41–0.79; p=0.01) in 129 matched patient pairs. In a third subgroup analysis limited to patients who received an R0 resection, S was again associated with a survival benefit compared to CR after six months in 151 matched pairs of patients (HR 0.57; 95%ci 0.41–0.79; p<0.001).

Discussion

In this propensity score-matched NCDB analysis, patients with both clinical and pathologic N3 NSCLC experienced similar short term and improved long term survival with surgery compared to definitive chemoradiation. Patients with cN3 disease undergoing surgery had a high rate of pathologic nodal downstaging. To our knowledge, this is the largest study examining the outcomes of patients with N3 lung cancer, and demonstrates that surgery is associated with superior long-term outcomes in a highly selected group of patients.

Our finding that patients with cN3 NSCLC can experience good overall survival after surgery corroborates the small amount of prospective and retrospective data in the literature. Patients undergoing surgery in our study had a median survival of 35 months, comparable to the range of 13 to 29 months reported in prospective studies3,4,21. Similarly, patients in our study had a pathologic nodal downstaging of 51% after surgery, which is comparable to the 30–48% in phase II studies3,6,9. Unfortunately, the prospective studies in stage IIIB NSCLC all contained only small subsets of patients with N3 disease, and generally did not examine this population separately in subgroup analyses. Similarly, a prior NCDB analysis13 of patients with clinical stage IIIB NSCLC demonstrated that multimodal therapy including surgery was associated with a survival benefit compared to chemoradiation alone; however, this study did not report a multivariable subgroup analysis of patients with N3 disease, only included surgery patients who received multimodal therapy, and examined patients with clinical stage IIIB disease alone. These studies did demonstrate that failure after multimodal therapy for cIIIB disease manifested as both distant metastases and local recurrence, suggesting that definitive local control in the form of surgical resection and lymphadenectomy may have a role to play in mitigating recurrence in N3 disease. In addition, the high pathologic downstaging rate in patients who underwent surgery might suggest that there is discordance between clinical and invasive nodal staging in this population, or that patients with response to induction therapy experience superior survival with surgery. The NCDB does not catalogue restaging after induction therapy, so we do not know how many patients with cN3 disease were downstaged before or after surgery. However, only 21% of patients undergoing surgery received neoadjuvant chemotherapy in our study, suggesting that significant downstaging might occur with invasive nodal staging alone. Our study reinforces the importance of invasive nodal staging, especially as studies suggest that a minority of patients nationwide receive invasive staging with significant center variability22,23. Further, in a subgroup analysis of cN3 patients who underwent induction therapy and surgery, we found an 87% pathologic nodal downstaging rate, suggesting that patients with good response to induction therapy were more likely to receive surgery and experience improved survival.

We then expanded our study to investigate the outcomes of patients, regardless of clinical stage, with pathologic N3 disease. As expected, over half of patients with pN3 disease had cN3 disease, with the remainder being upstaged. Prospective studies in stage III NSCLC have demonstrated that pathologic involvement of mediastinal nodes predicts mortality6,9,21, and we hypothesized that patients with pN3 disease undergoing S or CR would experience similar survival. Our finding that mid- to late survival is improved in patients undergoing surgery suggests that in selected patients with persistent N3 disease, surgery can offer acceptable outcomes. Indeed, one prospective study of stage III NSCLC found that patients with N2 and N3 disease were equally likely to have sterilization of mediastinal nodes3, suggesting that patients with N3 disease may have tumor behavior more aligned with N2 rather than T4 disease, and might benefit from multimodal therapy including surgery.

In both parts of our study, we found that early survival, less than about six months, was either similar between S and CR patients or worse for S patients. Examining the survival curves (Figures 2 and 3), the curves for CR patients remain flat early after diagnosis, while the curves for S patients fall immediately. This suggests that there might be immortal time bias in patients receiving CR, who have to survive several weeks to months to successfully receive definitive chemoradiotherapy, while patients undergoing surgery shortly after diagnosis may die soon after from complications related to surgery or from comorbidities. Our time-varying Cox models adjust for this finding.

This study allows us to draw inferences on patients with N3 disease who may most benefit from surgery, which can be augmented by experience from our institution. Our subgroup analysis of cN3 patients who received neoadjuvant therapy suggests that patients who respond well to neoadjuvant therapy may experience improved long-term survival compared to those receiving chemoradiation. In addition, our subgroup analyses on patients receiving lobar resections and margin-negative resections suggest that patients who may tolerate a lobar resection and with a high probability of a margin-negative resection may experience a greater survival benefit. Additionally, our time-varying Cox models suggest that patients who are good candidates for surgery and therefore survive beyond the initial few months following surgery are also more likely to benefit from resection. In our institution, surgery is rarely offered for patients with N3 disease. Surgery is offered to patients who exhibit a significant radiographic response to neoadjuvant therapy, who do not have supraclavicular disease, who are good surgical candidates, and who have non-bulky nodal disease.

Our study has several limitations in addition to those already described. As a retrospective cohort study, there is inherent selection bias that cannot be accommodated for. For instance, patients offered surgery rather than chemoradiation for N3 disease likely had non-bulky, single or oligo-station nodal involvement and a good response to induction therapy, if offered. However, none of these variables nor specific N3 disease location are coded in the NCDB. We did attempt to define this selection bias with a subgroup analysis of cN3 patients undergoing surgery following induction therapy, as discussed above. The NCDB also does not contain information about staging and re-staging techniques used. For instance, while we draw inferences about invasive nodal staging from the pathologic nodal stage reported for patients who did not receive a resection, the NCDB does not explicitly catalogue invasive nodal staging. Patients offered chemoradiation may also have been poor surgical candidates and consequently experienced worse survival. However, we attempted to adjust for such confounding by excluding CR patients who were not offered surgery due to poor fitness, as coded in the database, and by using propensity score matching based on variables like age, comorbidity index, treatment at an academic center, and tumor size. Finally, this study period predates that of the PACIFIC trial24,25, and as a result, we cannot compare the outcomes of patients receiving surgery with those receiving chemoradiation followed by durvalumab. However, the PACIFIC trial also did not report subgroup analyses on patients with N3 disease, and reported an overall median time to death or distant metastasis of 28 months in the treatment arm, which is comparable to the median survival of 35 months observed in S patients with cN3 disease in our study24. The PACIFIC study also does not contain information on how patients were deemed unresectable, which further limits its interpretation. Future research should focus on the potentially complementary effects of surgery and checkpoint inhibition in multimodal treatment of N3 lung cancer.

We report the most comprehensive analysis of outcomes following surgery vs. chemoradiation in patients with N3 NSCLC, finding that while early survival was similar between the groups, surgery was associated with improved long-term survival compared to chemoradiation in patients with cN3 or pN3 lung cancer (Figure 5). In a selected group of patients with N3 NSCLC, surgery may offer superior survival and can be considered as part of multimodal therapy, though prospective, randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate the role of surgery in multimodal therapy for this patient population.

Visual Abstract. In this National Cancer Database (NCDB) study,

surgery was associated with improved long-term overall survival compared to chemoradiation in patients with clinical or pathologic N3 disease. The graphical abstract demonstrates the results of propensity score-matched analysis of clinical (cN3) and pathologic (pN3) patients with hazard ratios (HR) and confidence intervals (95%CI) from time-varying multivariable Cox regression presented in tables and Kaplan-Meier survival curves with numbers at risk beneath.

Supplementary Material

Central Figure.

Surgery has survival benefit in N3 NSCLC.

Perspective Statement.

There is minimal literature on the role of surgery for N3 lung cancer. Our study demonstrates that surgery is associated with a survival benefit even in persistent, pathologic N3 disease compared to chemoradiation, and suggests that surgery may have a role in multimodal therapy for patients with N3 NSCLC.

Acknowledgements and Funding

The American College of Surgeons is in a Business Associate Agreement that includes a data use agreement with each of its Commission on Cancer accredited hospitals. The data used in the study are derived from a de-identified National Cancer Data Base file. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology used or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigators.

Drs. Raman and Voigt were supported by a National Institutes of Health T-32 grant FT32CA093245 in surgical oncology. Dr. Jawitz was supported by a National Institutes of Health T-32 grant 5T32HL069749 in clinical research.

Footnotes

This paper was presented at the American Association of Thoracic Surgeons (AATS) meeting in Toronto in May 2019.

References

- 1.Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-Slideset-Early-and-Locally-Advanced-Non-Small-Cell-Lung-Cancer-NSCLC.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 19];Available from: https://www.esmo.org/content/download/129682/2437285/file/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-Slideset-Early-and-Locally-Advanced-Non-Small-Cell-Lung-Cancer-NSCLC.pdf

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines on Treatment of Small Cell Lung Cancer. 2018;

- 3.DeCamp MM, Rice TW, Adelstein DJ, et al. Value of accelerated multimodality therapy in stage IIIA and IIIB non–small cell lung cancer. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2003;126(1):17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ichinose Y, Fukuyama Y, Asoh H, et al. Induction chemoradiotherapy and surgical resection for selected stage IIIB non–small-cell lung cancer. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2003;76(6):1810–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stupp R, Mayer M, Kann R, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy followed by surgery in selected patients with stage IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre phase II trial. The Lancet Oncology 2009;10(8):785–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grunenwald DH, André F, Le Péchoux C, et al. Benefit of surgery after chemoradiotherapy in stage IIIB (T4 and/or N3) non–small cell lung cancer. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2001;122(4):796–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stamatis G, Eberhardt W, Stüben G, Bildat S, Dahler O, Hillejan L. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy and surgery for selected non-small cell lung cancer IIIB subgroups: long-term results. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 1999;68(4):1144–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiden PL, Piantadosi S. Preoperative chemotherapy (cisplatin and fluorouracil) and radiation therapy in stage III non-small cell lung cancer. A phase 2 study of the LCSG. Chest 1994;106(6 Suppl):344S–347S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pitz CCM, Maas KW, Swieten HAV, de la Rivière AB, Hofman P, Schramel FMNH. Surgery as part of combined modality treatment in stage IIIB non-small cell lung cancer. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2002;74(1):164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albain KS, Crowley JJ, Turrisi AT, et al. Concurrent Cisplatin, Etoposide, and Chest Radiotherapy in Pathologic Stage IIIB Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Southwest Oncology Group Phase II Study, SWOG 9019. JCO 2002;20(16):3454–3460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rusch VW, Albain KS, Crowley JJ, et al. Surgical resection of stage IIIA and stage IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer after concurrent induction chemoradiotherapy. A Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993;105(1):97–104; discussion 104–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albain KS, Swann RS, Rusch VW, et al. Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy with or without surgical resection for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2009;374(9687):379–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bott MJ, Patel AP, Crabtree TD, et al. Role for Surgical Resection in the Multidisciplinary Treatment of Stage IIIB Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2015;99(6):1921–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galetta D, Cesario A, Margaritora S, et al. Enduring challenge in the treatment of nonsmall cell lung cancer with clinical stage IIIB: results of a trimodality approach. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2003;76(6):1802–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeda S Results of pulmonary resection following neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced (IIIA–IIIB) lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;30(1):184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15(3):683–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MatchIt: Nonparametric Preprocessing for Parametric Causal Inference [Internet]. [cited 2019 Apr 18];Available from: https://gking.harvard.edu/matchit

- 18.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 2009;28(25):3083–3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrell FE. Multivariable Modeling Strategies [Internet] In: Harrell Frank E Jr, editor. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. [cited 2019 Apr 6]. p. 63–102.Available from: 10.1007/978-3-319-19425-7_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Han D, Hou Y, Chen H, Chen Z. Statistical inference methods for two crossing survival curves: a comparison of methods. PLoS ONE 2015;10(1):e0116774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albain KS, Rusch VW, Crowley JJ, et al. Concurrent cisplatin/etoposide plus chest radiotherapy followed by surgery for stages IIIA (N2) and IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer: mature results of Southwest Oncology Group phase II study 8805. JCO 1995;13(8):1880–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krantz SB, Howington JA, Wood DE, et al. Invasive Mediastinal Staging for Lung Cancer by The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database Participants. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;106(4):1055–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thornblade LW, Wood DE, Mulligan MS, et al. Variability in invasive mediastinal staging for lung cancer: A multicenter regional study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;155(6):2658–2671.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Overall Survival with Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III NSCLC. New England Journal of Medicine 2018;379(24):2342–2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2017;377(20):1919–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.