Abstract

Chalcone synthase (CHS) is a key enzyme in the flavonoid pathway, participating in the production of phenolic phytoalexins. The rice genome contains 31 CHS family genes (OsCHSs). The molecular characterization of OsCHSs suggests that OsCHS8 and OsCHS24 belong in the bona fide CHSs, while the other members are categorized in the non-CHS group of type III polyketide synthases (PKSs). Biochemical analyses of recombinant OsCHSs also showed that OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 catalyze the formation of naringenin chalcone from p-coumaroyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA, while the other OsCHSs had no detectable CHS activity. OsCHS24 is kinetically more efficient than OsCHS8. Of the OsCHSs, OsCHS24 also showed the highest expression levels in different tissues and developmental stages, suggesting that it is the major CHS isoform in rice. In oschs24 mutant leaves, sakuranetin content decreased to 64.6% and 80.2% of those in wild-type leaves at 2 and 4 days after UV irradiation, respectively, even though OsCHS24 expression was mostly suppressed. Instead, the OsCHS8 expression was markedly increased in the oschs24 mutant under UV stress conditions compared to that in the wild-type, which likely supports the UV-induced production of sakuranetin in oschs24. These results suggest that OsCHS24 acts as the main CHS isozyme and OsCHS8 redundantly contributes to the UV-induced production of sakuranetin in rice leaves.

Keywords: chalcone synthase, sakuranetin, rice, sakuranetin biosynthesis, phytoalexin, UV

1. Introduction

Phytoalexins are antimicrobial secondary metabolites, and their production is induced by pathogen infections and environmental stress [1]. Rice produces a variety of diterpenoid and phenolic phytoalexins in response to pathogen attacks as well as UV stress [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The flavonoid sakuranetin is a well-known phenolic phytoalexin in rice, which is the 7-O-methylated form of naringenin [3,6,7]. Sakuranetin was first isolated from UV-irradiated rice leaves, and was also detected in blast-infected rice leaves [3]. Naringenin O-methyltransferase (OsNOMT) for sakuranetin synthesis was purified from the UV-treated rice oscomt1 mutant and the corresponding gene was identified [8]. The expression of OsNOMT was found to be induced in response to UV irradiation prior to sakuranetin accumulation [5]. Microarray and phytochemical analyses of UV-treated rice leaves revealed that the expressions of phenylpropanoid and flavonoid pathway genes including CHS and chalcone isomerase (CHI) genes are induced by UV and participate in sakuranetin production [5,6,7].

CHS is the first committed enzyme in the flavonoid pathway, which catalyzes the formation of naringenin chalcone from one p-coumaroyl-CoA and three malonyl-CoAs [9,10,11]. Naringenin chalcone is converted to naringenin by CHI to provide C6-C3-C6 backbones for a wide range of flavonoids [12]. The CHS superfamily is known as the plant type III PKS superfamily [9,10,13]. In addition to CHS, plant type III PKSs include diverse biosynthetic enzymes—such as stilbene synthase (STS), curcumin synthase, acridone synthase, bibenzyl synthase, and benzophenone synthase—providing backbones for a variety of plant secondary metabolites [9,10]. Type III PKSs are homodimeric enzymes of two identical subunits and have the Cys-His-Asn catalytic triad at the active site [9,10]. The crystal structures of CHSs, including Medicago sativa CHS2 (MsCHS2), reveal that CHS retains catalytic Cys-His-Asn residues [14,15].

The number of CHS family genes is highly variable among plant species. Eight copies of CHS genes were identified in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) [16]. In maize and soybean, the CHS family consists of 14 genes [17,18]. A moss, Physcomitrella patens, contains 17 CHS members [19]. Citrus species were found to have 77 CHS family genes [20]. Homology searches of databases using the MsCHS2 sequence as a query have shown that the rice genome has more than 27 CHS family genes [21,22]. Several studies have reported the biochemical functions of rice CHS family genes rather than CHS, such as curcuminoid synthase (CUS) and alkylresorcylic acid synthase (ARAS) [21,23,24].

In the present study, we performed the molecular and biochemical characterization of OsCHSs and found that OsCHS8 and OsCHS24 encode the functional CHSs in rice. Analyses of sakuranetin accumulation and the expressions of OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 in a UV-treated oschs24 mutant revealed their roles in sakuranetin biosynthesis under UV stress conditions.

2. Results

2.1. The Rice CHS Family

A search of the MSU RGAP Database revealed 31 genes that were annotated as putative CHSs and/or STSs, which together comprise the CHS family in rice (Table 1). This includes 27 previously identified OsPKSs [22]. CHS is a homodimer of two 40–45 kDa polypeptides [10,11]. Theoretical molecular masses of most OsCHSs were comparable with those of the functional CHSs. OsCHS26–28 and 31 have very short open reading fames (ORFs) of 417–636 base pairs (bp) (Table 1). The ORFs of OsCHS5, 19, 20, and 21 were also significantly shorter than the typical lengths of CHSs, leading to a large deletion in the N-terminal region of CHS (Figure S1). Therefore, these OsCHSs are unlikely to encode functional CHS family enzymes. In contrast, OsCHS11 has a long ORF of 1365 bp encoding a protein of 49.8 kDa, leading to an insertion of 50 amino acids in the middle of the N-terminal region of CHS (Figure S1).

Table 1.

Rice CHS family. The MSU RGAP Database search revealed 31 genes that were annotated as putative CHSs and/or STSs, which comprise the CHS family in rice.

| Locus ID. | Name | Gene Description in the RGAP DB | ORF Length | Protein | Theoretical |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (bp) | Size (aa) | Mass (kDa) | |||

| Os01g41834 | OsCHS1 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1200 | 399 | 41.8 |

| Os04g01354 | OsCHS2 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1182 | 393 | 42.7 |

| Os04g23940 | OsCHS3 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1122 | 373 | 39.9 |

| Os05g12180 | OsCHS4 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1179 | 392 | 42.6 |

| Os05g12190 | OsCHS5 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 939 | 312 | 333 |

| Os05g12210 | OsCHS6 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1179 | 392 | 42.6 |

| Os05g12240 | OsCHS7 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1179 | 392 | 42.7 |

| Os07g11440 | OsCHS8 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1212 | 403 | 43.9 |

| Os07g17010 | OsCHS9 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1209 | 402 | 43.2 |

| Os07g22850 | OsCHS10 | Chalcone and stilbene synthase, putative | 1290 | 429 | 46.5 |

| Os07g31750 | OsCHS11 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1365 | 454 | 49.8 |

| Os07g31770 | OsCHS12 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1218 | 405 | 42.8 |

| Os07g34140 | OsCHS13 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1197 | 398 | 43 |

| Os07g34190 | OsCHS14 | Chalcone and stilbene synthase, putative | 1197 | 398 | 42.6 |

| Os07g34260 | OsCHS15 | Chalcone and stilbene synthase, putative | 1200 | 399 | 42.4 |

| Os10g07040 | OsCHS16 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1197 | 398 | 43.2 |

| Os10g07616 | OsCHS17 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1197 | 398 | 43.2 |

| Os10g08620 | OsCHS18 | Chalcone and stilbene synthase, putative | 1200 | 399 | 43.2 |

| Os10g08670 | OsCHS19 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1032 | 343 | 37.5 |

| Os10g08710 | OsCHS20 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 885 | 294 | 31.6 |

| Os10g09860 | OsCHS21 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1092 | 363 | 39.2 |

| Os10g34360 | OsCHS22 | Stilbene synthase, putative | 1170 | 389 | 42.2 |

| Os11g32620 | OsCHS23 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1224 | 407 | 42.6 |

| Os11g32650 | OsCHS24 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1197 | 398 | 43.4 |

| Os11g35930 | OsCHS25 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 1200 | 399 | 42.9 |

| Os03g47000 | OsCHS26 | Chalcone synthase 1, putative | 417 | 138 | 14.6 |

| Os05g41645 | OsCHS27 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 438 | 145 | 15.6 |

| Os11g32540 | OsCHS28 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 636 | 212 | 22.2 |

| Os11g32580 | OsCHS29 | Chalcone synthase | 1242 | 413 | 43.9 |

| Os11g32610 | OsCHS30 | Chalcone and stilbene synthases, putative | 1206 | 401 | 42.4 |

| Os12g07690 | OsCHS31 | Chalcone synthase, putative | 426 | 142 | 14.9 |

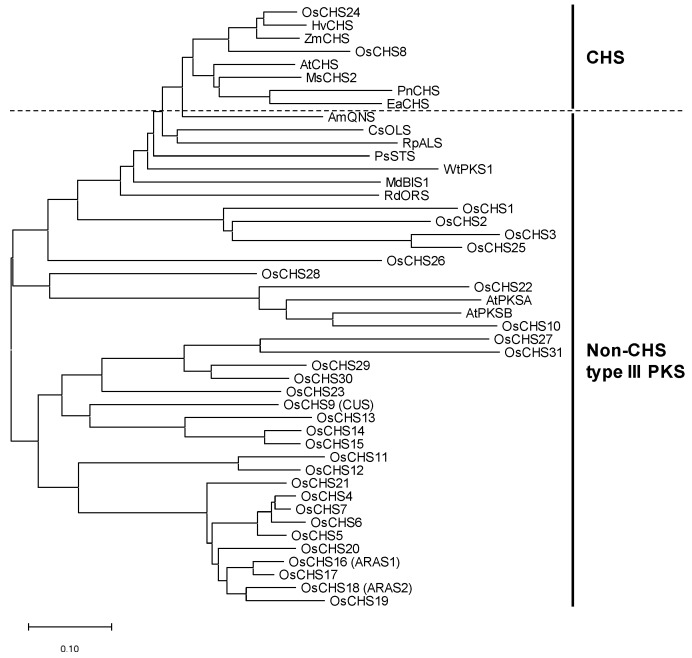

Multiple alignments of the amino acid sequences of OsCHSs and other plant CHSs showed that OsCHS8 and OsCHS24 are highly homologous to other CHSs, showing similarities of 71–94% (Table S1). Phylogenetic analysis also indicated that OsCHS8 and OsCHS24 were closely related to the bona fide CHSs (Figure 1). The other OsCHSs showed similarities of 17–66% to CHSs (Table S1) and were categorized into the non-CHS group of type III PKSs (Figure 1), suggesting that they likely play different metabolic roles than CHS. OsCHS9, OsCHS16, and OsCHS18 showed 55–62% similarities to CHSs (Table S1). OsCHS9 was previously identified as CUS [23]. OsCHS16 and OsCHS18 were demonstrated to encode ARASs [21]. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that OsCHS10 and OsCHS22 are closely related to AtPKSA and AtPKSB, which are involved in the formation of the outer pollen wall (Figure 1) [25,26].

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of OsCHSs and other plant CHS family members. The amino acid sequences were aligned with Clustal-W and the neighbor-joining tree was built with MEGA ver. 6. Amino acid sequences used were AtCHS (AAB35812), ZmCHS (NP_001142246.1) EaCHS (Q9MBB1), HvCHS (CAA41250), MsCHS2 (P30074), PnCHS (BAA87922), AmQNS (AGE44110), CsOLS (B1Q2B6), RpALS (AAS87170), PsSTS (CAA43165), WtPKS1 (AAW50921), MdBIS1 (NP_001315967), RdORS (BAV83003), AtPKSA (O23674), and AtPKSB (Q8LDM2). QNS, OLS, ALS, BIS, and ORS stand for quinolone synthase, olivetol synthase, aloesone synthase, 3,5-dihydroxybiphenol synthase, and orcinol synthase, respectively.

2.2. Analyses of the Conserved Residues and Motifs in the CHS Family

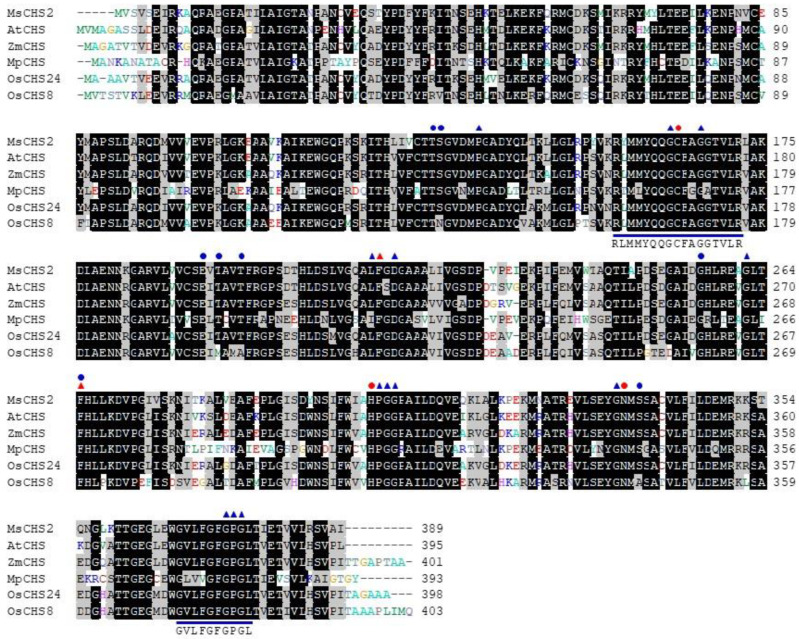

CHS contains three conserved residues, Cys164, His303, and Asn336 (all numbering of residues follows that of MsCHS2), which form a catalytic triad in the type III PKSs [9,10,14]. These catalytic residues are well conserved in most OsCHSs (Figure 2 and Figure S1). OsCHS19, 26, 27, and 31, however, lack more than one residue of the catalytic triad (Figure S1). Two Phe residues (Phe215 and Phe265) have been shown to be conserved in CHSs [9,10,14]. Phe215 is mostly conserved in OsCHSs except OsCHS27 that lacks the residue (Figure 2 and Figure S1). Phe265 is conserved in OsCHS8 and OsCHS24, whereas it is not strictly conserved in the non-CHS group of OsCHSs (Figure 2 and Figure S1). In addition to the catalytic triad, 13 residues shaping the geometry of the active site have been shown to be highly conserved in CHS enzymes [14,27]. These residues were absolutely conserved in about half of OsCHSs, including OsCHS8 and OsCHS24 (Figure 2 and Figure S1). Significant numbers of these residues are missing in OsCHS19, 26, 27 and 31. CHSs have highly conserved motifs of “RLMMYQQGCFAGGTVLR” and “GVLFGFGPGL” [28,29,30]. These motifs are absolutely conserved in OsCHS8 and OsCHS24, but vary in other OsCHSs (Figure 2 and Figure S1). In particular, OsCHS19, 26, and 31 were found to be missing one or both of these motifs. Based on the unusual ORF lengths and variations in the conserved residues and motifs, OsCHS5, 11, 19, 20, 21, 26, 27, and 31 were not expected to encode functional CHS family proteins.

Figure 2.

Multiple alignments of amino acid sequences of OsCHSs and other plant CHSs. The amino acid sequences were aligned with Clustal-W. Amino acid residues that are identical or similar are shaded in black and gray, respectively. Red circles indicate catalytic triad residues in CHSs. Residues marked with red triangles are gatekeeper Phe residues. Blue triangles are conserved residues shaping the active site geometry of CHS. The blue circles indicate residues important in the binding of the coumaroyl moiety and the specificity of cyclization reactions in CHSs. The conserved motifs in CHSs are underlined and their consensus sequences indicated. Amino acid sequences of other plant CHSs used were MsCHS2 (P30074), AtCHS (AAB35812), ZmCHS (NP_001142246), and MpCHS (CAD42328).

2.3. Cloning and Heterologous Expression of OsCHSs

To identify the genes encoding functional CHS proteins, we attempted to clone OsCHSs other than the expected non-functional OsCHSs. The cDNAs of OsCHS1–4, 7–9, 12, 15, 16, 18, 22, 24, and 25 were successfully cloned from rice leaves. Each OsCHS cDNA was inserted into the expression vector pET28a, and then the resulting constructs were transformed in to Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). The recombinant OsCHS protein containing the N-terminal His-tag was produced in E. coli under various growth and induction conditions (Figure S2). OsCHS2, 7, 9, 12, 15, 16, 18, 22, 24, and 25 were successfully expressed as soluble forms in E.coli by 0.1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) under an induction temperature of 25 °C. OsCHS4 and 8 were produced in E.coli at 18 °C and at 0.1 mM IPTG concentration. OsCHS1 and 3 were produced only as insoluble forms under various growth temperatures and IPTG concentrations. The recombinant OsCHS proteins were purified with Ni2+ affinity chromatography (Figure S2).

2.4. CHS Activity and Kinetic Parameters of the Recombinant OsCHSs

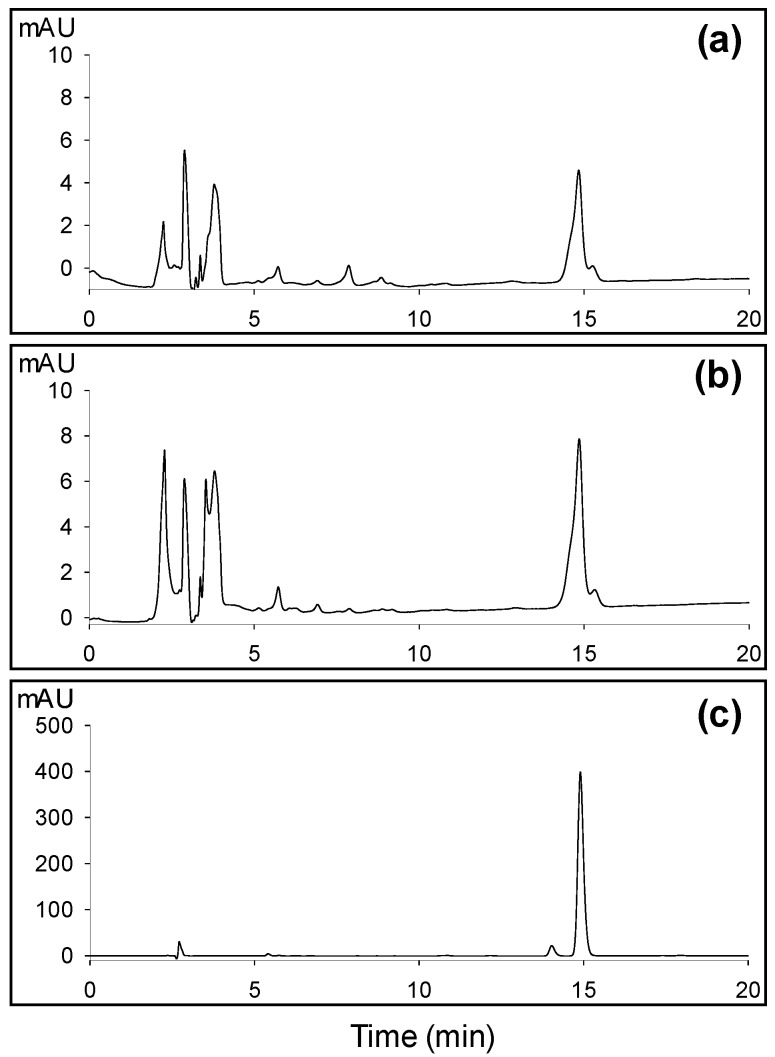

The CHS activity of the recombinant OsCHS proteins was assayed with p-coumaroyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA as substrates. Naringenin chalcone synthesized by CHS is spontaneously converted to naringenin in aqueous solutions [31,32]. Therefore, the CHS activity of the recombinant OsCHSs was determined by analyzing the accumulation of naringenin using HPLC. In accordance with the strong conservation of the important residues of CHS activity, among 12 recombinant OsCHS proteins examined, OsCHS8 and OsCHS24 exhibited CHS activity (Figure 3 and Figure S3). All examined recombinant OsCHSs belonged in the non-CHS group showed no detectable CHS activity (Figure S3). This result suggests that among OsCHS family members, OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 encode biochemically functional CHS proteins.

Figure 3.

CHS activity assay of recombinant OsCHS8 (a) and OsCHS24 (b). The tetrahydroxychalcone was formed from p-coumaroyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA by OsCHS8 and OsCHS24. The resulting chalcone was spontaneously converted to naringenin, which was analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC. (c) HPLC chromatogram of the authentic naringenin.

The kinetic parameters of recombinant OsCHS8 and OsCHS24 were determined towards the p-coumaroyl- and malonyl-CoA substrates (Table 2). The KM values of OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 for p-coumaroyl-CoA were 45.44 and 27.64 µM, respectively (Table 2). Both OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 showed similar affinity for malonyl-CoA, with KM values of 47.42 and 59.38 µM, respectively. OsCHS24 showed a higher catalytic efficiency than OsCHS8, with kcat/KM values of 1137.05 and 539.81 M−1 min−1, respectively.

Table 2.

Steady-state kinetic parameters of recombinant OsCHS24 and OsCHS8

| OsCHS | p-Coumaroyl-CoA | Malonyl-CoA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KM (μM) | Vmax (nmol min−1 mg−1) | kcat (min−1) | kcat/KM (M−1 min−1) | KM (μM) | |

| OsCHS8 | 27.64 ± 4.21 | 0.352 ± 0.02 | 0.0149 | 539.81 | 59.38 ± 13.83 |

| OsCHS24 | 45.44 ± 2.94 | 1.218 ± 0.05 | 0.0517 | 1137.05 | 47.42 ± 8.21 |

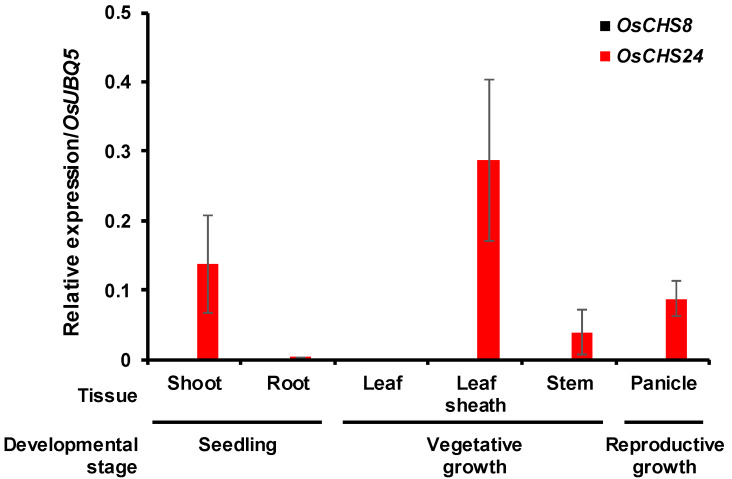

2.5. In Silico and qRT-PCR Analyses of OsCHS Expression

The in silico expression analysis revealed that among OsCHSs, OsCHS24 showed the highest expression levels at different developmental stages (Figure S4). The expression levels of the other OsCHSs were very low at all developmental stages (Figure S4). The quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis also showed that OsCHS24 is highly expressed in shoot tissues at an early growth stage and in the leaf sheath, stem, and panicle tissues in adult rice plants (Figure 4). Hu et al. [22] examined the OsCHS expressions in root, stem, leaf, young flower, and adult flower tissues and found that OsCHS24 was expressed in the rice stem tissue. It was also reported that OsCHS24 was expressed in rice seedlings [33]. The transgenic expression of OsCHS24 was also shown to restore flavonoid accumulation in the Arabidopsis transparent testa 4 mutant [33]. These findings suggest that OsCHS24 acts as the major CHS isoform in rice. The expression of OsCHS8, another gene encoding a functional CHS, was very low at all examined developmental stages and tissues under normal growth conditions.

Figure 4.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 gene expression in rice seedlings and different adult tissues. Shoot and root samples were collected from seven-day-old rice seedlings. Leaf, leaf sheath, stem, and panicle samples were obtained from rice plants in vegetative and reproductive stages. An ubiquitin 5 gene (OsUBQ5) was used as an internal control. Expression levels of each OsCHS gene are presented as relative expression compared to OsUBQ5 mRNA level. qRT-PCR analysis was performed on the triplicated biological samples. The results represent mean ± standard deviation.

2.6. Sakuranetin Accumulation and OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 Expression in the UV-Irradiated oschs24

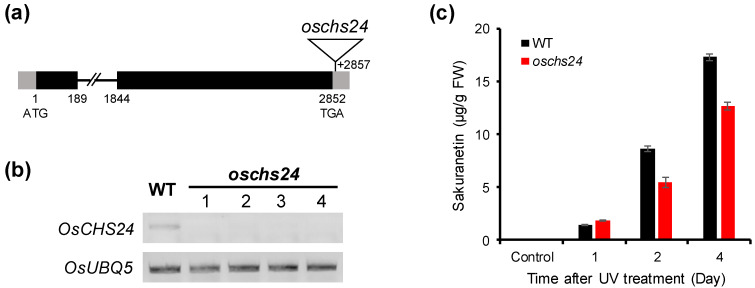

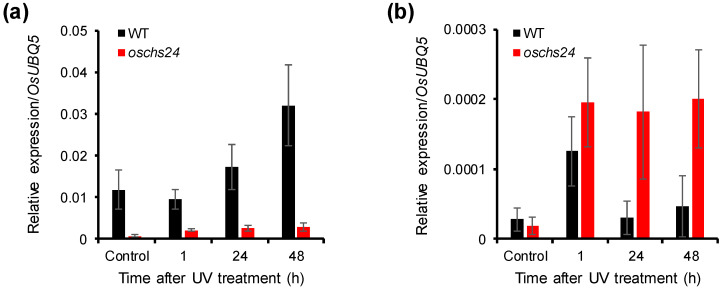

To ascertain the role of OsCHS24 in sakuranetin accumulation, we characterized the oschs24 mutant isolated from the rice T-DNA insertion mutant population [34]. The oschs24 mutant has the T-DNA insertion in the 3’ UTR region of OsCHS24 (Figure 5a). In homozygous oschs24 mutants, the expression of OsCHS24 was mostly suppressed by the insertion of T-DNA (Figure 5b). OsCHS24 expression was increased in wild-type plants by UV irradiation, whereas it was not induced in UV-treated oschs24 leaves (Figure 6a). The sakuranetin content in UV-treated leaves of oschs24 were analyzed to elucidate the effect of the suppressed expression of OsCHS24. The sakuranetin content was not drastically decreased in UV-treated leaves of oschs24 (Figure 5c), although the OsCHS24 expression in oschs24 was mostly suppressed even under UV stress conditions (Figure 6a). The sakuranetin content in oschs24 was 64.6% and 80.2% of that in the wild-type at 2 and 4 days after UV irradiation, respectively (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Characterization of the oschs24 mutant. (a) The gene structure of OsCHS24 showing the T-DNA insertion position of the oschs24 mutant. Black boxes, gray boxes, and lines between boxes indicate exons, UTRs and introns, respectively. A triangle represents the position of the T-DNA insertion in oschs24. (b) RT-PCR analysis of OsCHS24 expression in the leaves of homozygous oschs24 mutants. The homozygous oschs24 plants showed the suppressed expression of OsCHS24. OsUBQ5 was used as an internal control. (c) Accumulation of sakuranetin in wild-type and oschs24 mutant in response to UV irradiation. The leaf samples were collected from UV-treated rice plants 1, 2, and 4 days after UV irradiation. Analyses of the sakuranetin contents were performed on triplicate biological samples. The results represent the mean ± standard deviation. FW; fresh weight.

Figure 6.

Analysis of the OsCHS24 (a) and OsCHS8 (b) expression in oschs24 in response to UV irradiation. Transcript levels of OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 in the wild-type an oschs24 mutants were analyzed by qRT-PCR. An ubiquitin 5 gene (OsUBQ5) was used as an internal control. Expression levels of each OsCHS gene are presented as relative expression compared to the OsUBQ5 mRNA level. qRT-PCR analysis was performed on triplicate biological samples. The results represent mean ± standard deviation.

Unlike OsCHS24, the expression of OsCHS8, which encode another functional CHS isozyme, was immediately increased by UV irradiation. The induced expression levels were maintained for 48 h after UV irradiation (Figure 6b). The OsCHS8 expression, however, reached its peak at 1 h after UV-treatment and then decreased to non-UV-treated levels in the wild-type (Figure 6b). The small decrease of sakuranetin contents and the maintained induction of OsCHS8 in UV-treated oschs24 leaves suggest that OsCHS8 contributes to sakuranetin biosynthesis in oschs24 under UV stress conditions.

3. Discussion

3.1. OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 Encode Functional CHSs in Rice

Although the CHS families are comprised of multiple genes, a few of them act as bona fide CHSs and the others participate in different metabolic processes [20,26,35]. Arabidopsis contains four CHS family genes, of which one gene (AtCHS) has been identified to participate in flavonoid biosynthesis [26,36]. Two Arabidopsis CHS family members (AtPKSA and AtPKSB) have been shown to encode hydroxyalkyl α-pyrone synthases, which are involved in the synthesis of sporopollenin, the major constituent of exine in the outer pollen wall [25,26]. In soybean, two CHS genes were found to be closely related to bona fide CHSs [18]. Of the OsCHSs, OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 were shown to be closely related to other bona fide CHSs (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Each subunit of the CHS homodimer contains an independent active site catalyzing the elongation of the ketide chain on the p-coumaroyl starter molecule and cyclization of the tetraketide intermediate to form the chalcone [9,14]. In CHSs, two gatekeeper Phe residues (Phe215 and Phe265) positioned in the lower portion of the CoA-binding tunnel and the active site cavity were shown to facilitate substrate loading and the proper folding of the tetraketide intermediate in the cyclization reaction [9,10,14]. Along with Cys164, His303, and Asn336, Phe215 were known to be conserved in all CHSs and other type III PKSs [9,14]. Phe265 is important in substrate specificity and is conserved in CHSs, whereas it varies in other type III PKSs [9,10,37]. OsCHS9 includes the substitution of Phe265 with Gly and has no detectable CHS activity (Figures S1 and S3). Instead of CHS, OsCHS9 was shown to encode CUS [23,24]. OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 contain both Phe residues and indeed, exhibited CHS activity. These findings suggest that OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 encode functional CHSs in rice (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Divergent Type III PKSs differ in their preferences for starter molecules, degree of polyketide elongation, and intramolecular cyclization patterns. Subtle changes in the structure of their active sites lead to alterations in their kinetic properties and substrate/product specificities of type III PKSs [9,37,38]. Thr132, Ser133, Glu192, Thr194, Thr197, Gly256, Phe265, and Ser338 in CHS are important in the binding of the coumaroyl moiety and the cyclization reaction [9,10,14]. All of these residues are conserved in OsCHS24, and some of them are substituted in OsCHS8 (Figure 2). In OsCHS8, Ser133, Thr194, Thr197, and Ser338 are substituted for Asn, Met, Ala, and Ala, respectively (Figure 2), which likely leads to the lower catalytic efficiency of OsCHS8 compared to OsCHS24. In Grewia asiatica, two isoforms of CHSs, GaCHS1 and GaCHS2, were characterized to have CHS activity and showed different catalytic efficiencies towards p-coumaroyl-CoA [30]. Although important residues for the CHS function are highly conserved in both GaCHSs, Thr132 and Ser133 are substituted for His and Ala in GaCHS1, respectively, which may lead to differences in the kinetic properties of the isozymes. These residues have shown to be specifically substituted in other type III PKSs and are thought to define the substrate and product specificity of the enzyme [10,37]. The recombinant OsCHS9 protein was shown to have CUS activity catalyzing the formation of bisdemethoxycurcumin from two p-coumaroyl-CoAs and one malonyl-CoA [23,24]. In OsCHS9, Thr132, Thr197, Gly256, and Phe265 are replaced with Asn, Tyr, Met, and Gly, respectively (Figure S1), which enlarges the entrance and downward pocket of the CUS active site to accommodate the p-coumaroyldiketide intermediate and the second coumaroyl unit [24,37]. OsCHS16 and OsCHS18 were identified as ARAS1 and ARAS2, respectively, which catalyze the formation of alkylresorcylic acids from fatty acyl-CoAs and three malonyl-CoAs [21]. In OsCHS16 and OsCHS18, Thr132, Thr197, and Gly256 are substituted with Tyr, Cys, and Met, respectively (Figure S1). Thr132, Gly256, and Phe265 are conserved in both OsCHS24 and OsCHS8, whereas they are mostly substituted with other amino acids in OsCHSs of the non-CHS group—such as OsCHS9, OsCHS16, and OsCHS18 (Figure 2 and Figure S1)—suggesting that these residues are critical for the substrate and product specificity of CHSs.

3.2. OsCHS24 and OsCHS8 Redundantly Contribute to the UV-Induced Accumulation of Sakuranetin in Rice Leaves

As the first committed enzyme for flavonoid biosynthesis, CHS plays an important role in plant defense [11]. It has been demonstrated that the expressions of CHS genes are induced by diverse stresses, which leads to the production of defensive compounds including phytoalexins [11]. The constitutive expression in different developmental stages (Figure S4) and strong CHS activity (Table 2) of OsCHS24 suggest that it is the major CHS isoform in rice. Along with UV-induced sakuranetin accumulation (Figure 5c), OsCHS24 expression was stimulated in rice leaves in response to UV irradiation (Figure 6a). In a previous study, we suggested that the expression of OsCHS24 was induced by UV and is relevant to sakuranetin accumulation in the UV-irradiated rice leaves [5,6]. The oschs24 mutant was analyzed to confirm the role of OsCHS24 in the UV-induced production of sakuranetin. Unexpectedly, the sakuranetin content was not significantly decreased in the UV-treated leaves of oschs24, despite the suppression of OsCHS24 expression (Figure 5c).

Although OsCHS8 encodes functional CHS, its expression levels were very low in different developmental stages and tissues (Figure 4 and Figure S4). Similarly, Shih et al. [33] reported that OsCHS8 expression was not detected in rice seedlings. In wild-type rice leaves, OsCHS8 expression was found to be induced immediately after UV irradiation and then decreased to the non-UV-treated level (Figure 6b). Interestingly, OsCHS8 was more strongly induced in oschs24 leaves than in wild-type leaves, and the induced transcript levels were maintained for 48 h after UV irradiation (Figure 6b), which likely complements the sakuranetin production in oschs24 under UV stress conditions. This finding, along with a small decrease of the sakuranetin content in UV-treated oschs24 leaves, suggests that OsCHS24 acts as the main CHS isoform and OsCHS8 contributes redundantly to the UV-induced production of sakuranetin in rice leaves.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Growth, UV Treatment, and Materials

The seeds of oschs24 mutant (line no. 2C-70073) and its Dongjin background rice (Oryza sativa L. spp. Japonica cv. Dongjin) were obtained from the rice T-DNA insertion mutant population in Crop Biotech Institute, Kyung Hee University, Korea [34]. The wild-type and the oschs24 mutant seeds were sterilized and germinated on Murashige and Skoog medium (Duchefa, Harlem, The Netherlands) in a growth chamber at 28 °C. Seven-day-old seedlings were transferred to soil, and grown in a greenhouse for 6–7 weeks to analyze sakuranetin content. UV-treatment of rice plants was performed according to the methods described by Park et al. [5]. For the expression analysis of OsCHSs, root and shoot samples were collected from seven-day-old seedlings. Rice stem and leaf samples were collected from 10-week-old wild type rice plants, and panicles were collected from 14-week-old rice plants.

Malonyl-CoA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). p-Coumaroyl-CoA was synthesized by the method described by Beuerle and Pichersky [39]. Other reagents used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Thermo-Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), Duchefa, and Samchun Chemicals (Seoul, Korea).

4.2. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

Protein sequences of CHSs and other type III PKSs were obtained from the MSU RGAP database (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/) [40] and the National Center for Biotechnological Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) database. The retrieved sequences were aligned using Clustal-W [41], and the phylogenetic tree was built by the neighbor-joining method using MEGA ver. 6 [42].

4.3. Cloning of OsCHSs

The first strand cDNA was synthesized using SuPrimeScript RT premix (GeNet Bio, Daejeon, Korea) with an oligo dT primer from total RNA extracted from eight-week-old rice leaves with RNAiso (Takara, Shiga, Japan). Cloning primers for OsCHSs and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions are summarized in Table S2. OsCHSs were amplified from the first strand cDNA with SolgTM Pfu DNA Polymerase (SolGent, Daejeon, Korea). The resulting PCR products were subcloned into the pGEMTM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) or the pJET 1.2 blunt cloning vector (Thermo-Fisher Scientific), and then their sequences were confirmed. Each OsCHS was cut with the appropriate restriction enzymes and inserted into the pET28a (+) vector (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA). The resulting OsCHS/pET28a(+) constructs were individually transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells for heterologous expression of OsCHSs.

4.4. Expression and Purification of Recombinant OsCHSs

E. coli cells bearing the OsCHS/pET28a(+) construct were grown at 37 °C until an OD600 of ~0.6 in LB medium containing kanamycin (25 µg/mL). To induce the production of OsCHSs, 0.1 mM IPTG was added into the culture, followed by an additional incubation for 16 h at 18 or 25 °C. After induction, the cells were harvested by centrifugation (5000× g for 15 min). The harvested cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4) supplemented with 1 mg/mL lysozyme and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The cells were suspended in PBS and sonicated on ice, and then centrifuged at 15,900× g for 20 min at 4 °C. The crude extract was mixed with Ni-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and incubated at 4 °C for 2 h with agitation. The mixtures were packed into a chromatography column and washed three times with a five-column volume of 20 mM imidazole in Tris buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl). The recombinant OsCHSs were eluted with 50 to 100 mM imidazole in Tris buffer. The eluted proteins were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

4.5. CHS Activity Assay and Steady-State Kinetics

OsCHS activity was measured according to the method of Zuubier et al. [43]. The enzyme activities of the purified recombinant OsCHSs were examined with p-coumaroyl- and malonyl-CoAs as substrates. The standard enzyme assay consisted of 80 µM p-coumaroyl-CoA and 160 µM malonyl-CoA in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) with 30 µg of recombinant OsCHSs in total volume of 500 µL. The mixtures were incubated at 30 °C for 1h, and extracted twice with ethyl acetate. The extracts were evaporated, and the resulting residues were dissolved in methanol. The reaction products were analyzed using a reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipped with a Sunfire C18 column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) following the elution and detection conditions described by Park et al., (2013). To determine the steady-state kinetic parameters of the CHS reactions, the p-coumaroyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA concentrations used were 5–100 µM and 10–100 µM, respectively. The assays were performed in triplicate and results represented as mean ± standard deviation.

4.6. In Silico and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis of the OsCHS Gene Expression

Microarray data for OsCHSs at different development stages of rice were downloaded from the Genevestigator plant biology database (https://genevestigator.com/gv/doc/intro_plant.jsp) [44]. The normalized data were used to generate heatmap expression patterns using the Multi Experiment Viewer program (http://www.tm4.org/mev.html).

cDNAs synthesized from different tissues and developmental stages of rice were used as a template for qRT-PCR using a Prime Q-Mastermix (GeNet Bio, Daejeon, Korea) on an AriaMx real-time PCR system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Transcript levels were normalized by rice ubiquitin 5 (OsUBQ5) transcripts as a control. The ΔCt method was applied to calculate expression levels. We used primers that showed a single peak in melting curve data. The sequences and annealing temperatures of primers for qRT-PCR are listed in Table S3.

4.7. Analysis of Sakuranetin Content

Rice leaf samples collected from UV-treated and untreated rice plants were ground in liquid nitrogen and extracted with 70% methanol-water for 1 h with agitation. The aqueous methanol extracts were fractionated with ethyl acetate to enrich phenolic compounds. The ethyl acetate phases were dried in vacuo and the residues were dissolved in a small volume of methanol. The phenolic enriched fractions were used to measure sakuranetin contents using HPLC with the method described above.

Abbreviations

| CHS | chalcone synthase |

| PKS | polyketide synthase |

| OsCHS | rice chalcone synthase |

| OsNOMT | rice naringenin O-methyltransferase |

| CHI | chalcone isomerase |

| STS | stilbene synthase |

| MsCHS2 | Medicago sativa chalcone synthase 2 |

| CUS | curcuminoid synthase |

| ARAS | alkylresorcylic acid synthase |

| ORF | open reading frame |

| bp | base pair |

| IPTG | isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| qRT-PCR | quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| HPLC | high-performance liquid chromatography |

| OsUBQ5 | rice ubiquitin 5 |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/11/3777/s1. Figure S1. Multiple alignments of amino acid sequences of OsCHSs and other plant CHSs. Figure S2. Purification of the recombinant OsCHSs heterologously expressed in E. coli. Figure S3. CHS activity assay of recombinant OsCHSs. Figure S4. In silico expression analysis of OsCHSs in different developmental stages of rice plants. Table S1. Amino acid sequence similarity percentage between the OsCHS family members and other plant CHSs. Table S2. Primer sequences and PCR conditions for OsCHS cloning. Table S3. Primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.C., S.H.B., and S.-W.L.; Investigation, H.-L.P., Y.Y., T.-H.L., and M.H.C.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.-H.C. and H.-L.P.; Writing—review and editing, M.-H.C., H.-L.P., S.H.B., T.-H.L., and S.-W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Mid-career Researcher Program (NRF-2016R1A2B4014276 and NRF-2019R1A2B5B01070202) through NRF grant funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Republic of Korea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ahuja I., Kissen R., Bones A.M. Phytoalexins in defense against pathogens. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:73–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cartwright D.W., Langcake P., Pryce R.J., Leworthy D.P., Ride J.P. Isolation and characterization of two phytoalexins from rice as momilactones A and B. Phytochemistry. 1981;20:535–537. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)84189-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kodama O., Miyakawa J., Akatsuka T., Kiyosawa S. Sakuranetin, a flavanone phytoalexin from ultraviolet-irradiated rice leaves. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:3807–3809. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)97532-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters R.J. Uncovering the complex metabolic network underlying diterpenoid phytoalexin biosynthesis in rice and other cereal crop plants. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:2307–2317. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park H.L., Lee S.W., Jung K.H., Hahn T.R., Cho M.H. Transcriptomic analysis of UV-treated rice leaves reveals UV-induced phytoalexin biosynthetic pathways and their regulatory networks in rice. Phytochemistry. 2013;96:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park H.L., Yoo Y., Hahn T.R., Bhoo S.H., Lee S.W., Cho M.H. Antimicrobial activity of UV-induced phenylamides from rice leaves. Molecules. 2014;19:18139–18151. doi: 10.3390/molecules191118139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho M.H., Lee S.W. Phenolic Phytoalexins in Rice: Biological Functions and Biosynthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:29120–29133. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu T., Lin F., Hasegawa M., Okada K., Nojiri H., Yamane H. Purification and identification of naringenin 7-O-methyltransferase, a key enzyme in biosynthesis of flavonoid phytoalexin sakuranetin in rice. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:19315–19325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.351270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austin M.B., Noel J. The chalcone synthase superfamily of type III polyketide synthase. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2003;20:79–110. doi: 10.1039/b100917f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe I., Morita H. Structure and function of the chalcone synthase superfamily of plant type III polyketide synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:809–838. doi: 10.1039/b909988n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dao T.T.H., Linthorst H.J.M., Verpoorte R. Chalcone synthase and its functions in plant resistance. Phytochem. Rev. 2011;10:397–412. doi: 10.1007/s11101-011-9211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yonekura-Sakakibara K., Higashi Y., Nakabayashi R. The origin and evolution of plant flavonoid metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:943. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staunton J., Weissman K.J. Polyketide biosynthesis: A millennium review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001;18:380–416. doi: 10.1039/a909079g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrer J.L., Jez J.M., Bowman M.E., Dixon R.A., Noel J.P. Structure of chalcone synthase and the molecular basis of plant polyketide biosynthesis. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:775–784. doi: 10.1038/11553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liou G., Chiang Y.C., Wang Y., Weng J.K. Mechanistic basis for the evolution of chalcone synthase catalytic cysteine reactivity in land plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:18601–18612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glagoleva A.Y., Ivanisenko N.V., Khlestkina E.K. Organization and evolution of the chalcone synthase gene family in bread wheat and relative species. BMC Genet. 2019;20:30. doi: 10.1186/s12863-019-0727-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han Y., Ding T., Su B., Jiang H. Genome-wide identification, characterization and expression analysis of the chalcone synthase family in maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:161. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vadivel A.K.A., Krysiak K., Tian G., Dhaubhadel S. Genome-wide identification and localization of chalcone synthase family in soybean (Glycin max [L]Merr) BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:325. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1569-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koduri P.K.H., Gordon G.S., Barker E.I., Colpitts C.C., Ashton N.W., Suh D.Y. Genome-wide analysis of the chalcone synthase superfamily genes of Physcomitrella patens. Plant Mol. Biol. 2010;72:247–263. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9565-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z., Yu Q., Shen W., El Mohtar C.A., Zhao X., Gmitter F.G., Jr. Functional study of CHS gene family members in citrus revealed a novel CHS gene affecting the production of flavonoids. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:189. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1418-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuzawa M., Katsuyama Y., Funa N., Horinouchi S. Alkylresorcylic acid synthesis by type III polyketide synthases from rice Oryza sativa. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1059–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu L., He H., Zhu C., Peng X., Fu J., He X., Chen X., Ouyang L., Bian J., Liu S. Genome-wide identification and phylogenetic analysis of the chalcone synthase gene family in rice. J. Plant Res. 2017;130:95–105. doi: 10.1007/s10265-016-0871-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katsuyama Y., Matsuzawa M., Funa N., Horinouchi S. In vitro synthesis of curcuminoids by type III polyketide synthase from Oryza sativa. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:37702–37709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morita H., Wanibuchi K., Nii H., Kato R., Sugio S., Abe I. Structural basis for the one-pot formation of the diarylheptanoid scaffold by curcuminoid synthase from Oryza sativa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:19778–19783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011499107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S.S., Grienenberger E., Lallemand B., Colpitts C.C., Kim S.Y., de Azevedo Souza C., Geoffroy P., Heintz D., Krahn D., Kaiser M., et al. LAP6/POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE A and LAP5/POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE B encode hydroxyalkyl α–pyrone synthases required for pollen development and sporopollemin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2010;22:4045–4066. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.080028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saito K., Yonekura-Sakakibara K., Nakabayashi R., Higashi Y., Yamazaki M., Tohge T., Fernie A.R. The flavonoid biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis: Structural and genetic diversity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013;72:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng X., Bashandy H., Ainasoja M., Kontturi J., Pietiäinen M., Laitinen R.A.E., Albert V.A., Valkonen J.P.T., Elomaa P., Teeri T.H. Functional diversification of duplicated chalcone synthase genes in anthocyanin biosynthesis of Gerbera hybrida. New Phytol. 2014;201:1469–1483. doi: 10.1111/nph.12610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun W., Meng X., Liang L., Jiang W., Huang Y., He J., Hu H., Almqvist J., Gao X., Wang L. Molecular and biochemical analysis of chalcone synthase from Freesia hybrid in flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0119054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y., Dou Y., Wang R., Guan X., Hu Z., Zheng J. Molecular characterization and functional analysis of chalcone synthase from Syringa oblata Lindl. in the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. Gene. 2017;635:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wani T.A., Pandith S.S., Gupta A.P., Chandra S., Sharma N., Lattoo S.K. Molecular and functional characterization of two isoforms of chalcone synthase and their expression analysis in relation to flavonoid constituents in Grewia asiatica L. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0179155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mol J.N.M., Robbinst M.P., Dixon R.A., Veltkamp E. Spontaneous and enzymic rearrangements of naringenin chalcone to flavanone. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:2267–2269. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)83023-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okada Y., Sano Y., Kaneko T., Abe I., Noguchi H., Ito K. Enzymatic reactions by five chalcone synthase homologs from Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004;68:1142–1145. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shih C.H., Chu H., Tang L.K., Sakamoto W., Maekawa M., Chu I.K., Wang M., Lo C. Functional characterization of key structural genes in rice flavonoid biosynthesis. Planta. 2008;228:1043–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0806-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeon J.S., Lee S., Jung K.H., Jun S.H., Jeong D.H., Lee J., Kim C., Jang S., Lee S., Yang K., et al. T-DNA insertional mutagenesis for functional genomics in rice. Plant J. 2000;22:561–570. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamazaki Y., Suh D.Y., Sitthithaworn W., Ishiguro K., Kobayashi Y., Shibuya M., Ebizuka Y., Sankawa U. Diverse chalcone synthase superfamily enzymes from the most primitive vascular plant, Psilotum nudum. Planta. 2001;214:75–84. doi: 10.1007/s004250100586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shirley B.W., Kubasek W.L., Storz G., Bruggemann E., Koornneef M., Ausubel F.M., Goodman H.M. Analysis of Arabidopsis mutants deficient in flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant J. 1995;8:659–671. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.08050659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morita H., Wong C.P., Abe I. How structural subtleties lead to molecular diversity for the type III polyketide synthases. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:15121–15136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV119.006129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jez J.M., Austin M.B., Ferrer J.L., Bowman M.E., Schröder J., Noel J.P. Structural control of polyketide formation in plant-specific polyketide synthases. Chem. Biol. 2000;7:919–930. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(00)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beuerle T., Pichersky E. Enzymatic synthesis and purification of aromatic coenzyme A esters. Anal. Biochem. 2002;302:305–312. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawahara Y., de la Bastide M., Hamilton J.P., Kanamori H., McCombie W.R., Ouyang S., Schwartz D.C., Tanaka T., Wu J., Zhou S., et al. Improvement of the Oryza sativa Nipponbare reference genome using next generation sequence and optical map data. Rice. 2013;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1939-8433-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA 6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuurbier K.W.M., Fung S.Y., Scheffer J.J.C., Verpoorte R. Assay of chalcone synthase activity by high-performance liquid chromatography. Phytochemistry. 1993;34:1225–1229. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(91)80005-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hruz T., Laule O., Szabo G., Wessendorp F., Bleuler S., Oertle L., Widmayer P., Gruissem W., Zimmermann P. Genevestigator V3: A reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Adv. Bioinform. 2008;2008:420747. doi: 10.1155/2008/420747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.