Abstract

Infant respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis in the first 6 months of life was associated with increased odds of pneumonia, otitis media, and antibiotic prescription fills in the second 6 months of life. These data suggest a potential value of future RSV vaccination programs on subsequent respiratory health.

Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus, bronchiolitis, pneumonia, otitis media, infant antibiotics

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most common cause of respiratory infections in infants and often leads to hospitalization. The majority of RSV hospitalizations are in previously healthy, term infants [1]. RSV immunoprophylaxis is an effective strategy to reduce morbidity in high-risk infants, yet it is costly, burdensome to administer, and only recommended for a very small number of infants in specific risk groups [2]. As of 8 July 2019, although over 50 candidate RSV vaccines are in clinical trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Respiratory+Syncytial+Virus+%28RSV%29&term=vaccine&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=), there are no currently approved vaccines for disease prevention.

Infant RSV bronchiolitis is associated with an increased risk of early childhood wheezing and asthma [3]. While RSV impacts the developing immune system, microbiome, and airway epithelium [3], information on the risk of non-wheezing respiratory outcomes following RSV bronchiolitis in infants is largely unknown. The objective of this study was to determine whether RSV bronchiolitis during infancy was associated with an increased risk of the most common non-wheezing respiratory sequela during infancy: pneumonia, otitis media, and antibiotic utilization. A comprehensive understanding of the subsequent risks associated with RSV bronchiolitis is critical to understanding the burden of disease outside of the acute infection, as well as a value-added proposition of RSV vaccination programs for disease prevention, particularly for low- and middle-income countries.

METHODS

We conducted a population-based cohort study of infants born between 1995–2007 and continuously enrolled in the Tennessee Medicaid Program (TennCare) during the first year of life. Infants included in the study were ≥35 weeks estimated gestational age and born between 1 June and 31 December of each year (see Supplementary Figure 1). We excluded infants with a chronic medical disorder, receipt of RSV immunoprophylaxis in the first year of life, and/or pneumonia, otitis media, or an antibiotic prescription fill during the first 6 months of life. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University and the Tennessee Department of Public Health.

The main predictor variable was bronchiolitis from birth to age ≤6 months during the first RSV season of life (1 November to 31 March). RSV bronchiolitis was defined by the use of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes for acute bronchiolitis (466.1, 466.11, or 466.19) during a healthcare encounter, which we had previously validated based on viral identification [4]. Infants were classified based upon the most severe healthcare encounter they experienced for bronchiolitis: hospitalization, emergency department visit, outpatient visit, or none. The main outcome variables were pneumonia, otitis media, and/or antibiotic fill during the second 6 months of life (months 7–12), requiring at least a 30-day gap between the last episode of RSV bronchiolitis in the exposure window and the outcomes. The associations between RSV bronchiolitis in the first 6 months of life and ever having pneumonia, otitis media, and/or an antibiotic prescription fill during the second 6 months of life, as well as the severity-dependent relationship between RSV bronchiolitis healthcare encounters and these outcomes, were assessed using multivariable logistic regression. In a subset of infants whose mothers were also enrolled in TennCare with the mother’s asthma status available, we repeated the analyses, adjusting for maternal asthma status. All analyses were performed using R-software version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org). Additional information on methodology can be found in the Supplementary Material.

RESULTS

A total of 123 301 infants were included in the study. During the first 6 months of life, 8440 infants (6.8%) had at least 1 healthcare visit for RSV bronchiolitis. Key demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Infants with RSV bronchiolitis in the first 6 months of life were more likely to have pneumonia (3.4% vs 2.5%, respectively), otitis media (42.4% vs 35.6%, respectively), and/or an antibiotic fill (77.6% vs 74.2%, respectively) in the second 6 months of life, compared to those without RSV bronchiolitis in the first 6 months of life. RSV bronchiolitis increased the odds for pneumonia (unadjusted odds ratio [OR], 1.41 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.24–1.59]; adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.36 [95% CI, 1.20–1.54]), otitis media (OR, 1.33 [95% CI, 1.27–1.39]; aOR, 1.32 [95% CI, 1.26–1.38]), and antibiotic fills (OR, 1.21 [95% CI, 1.14–1.29]; aOR, 1.24 [95% CI, 1.16–1.32]).

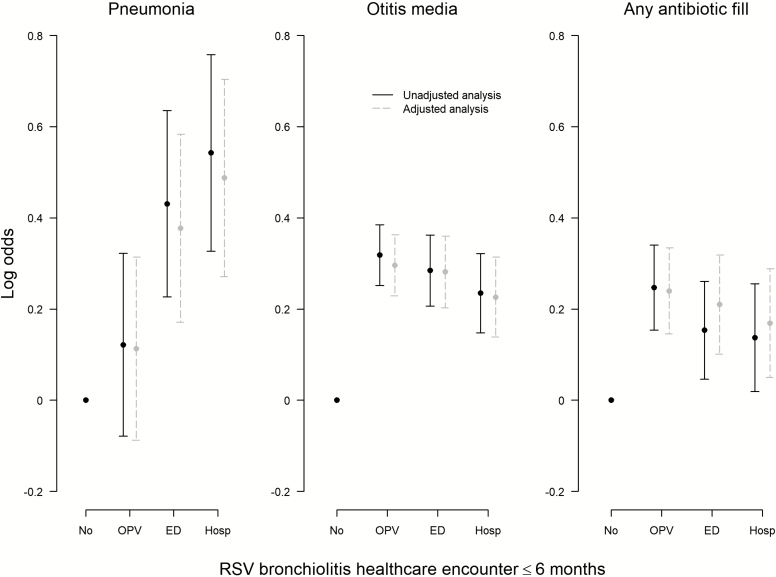

A dose-dependent relationship was observed between the increasing severity of RSV bronchiolitis during the first 6 months of life, as measured by the level of the healthcare encounter, and the relative odds of developing pneumonia in the second 6 months of life (Figure 1). Compared to those who did not experience RSV bronchiolitis in the first 6 months of life, the adjusted odds of ever having pneumonia during the second 6 months of life were 1.63 (95% CI, 1.31–2.02), 1.46 (95%, CI 1.19–1.79), and 1.12 (95% CI, .92–1.37) for subjects whose most severe healthcare encounters for RSV bronchiolitis in the first 6 months of life were a hospitalization, an emergency department visit, or an outpatient visit, respectively. In contrast, the odds of ever having otitis media or an antibiotic fill during the second 6 months of life did not differ by the severity of the RSV bronchiolitis healthcare encounter in the first 6 months of life.

Figure 1.

Association between the most severe RSV bronchiolitis healthcare encounter experienced in the first 6 months of life and pneumonia, otitis media, and/or antibiotic fill during the second 6 months of life (n = 123 301). Adjusted odds ratios were calculated using multivariable logistic regression. All regression models were adjusted for infant sex, infant race, birth weight, gestational age at delivery, mode of delivery, twin birth, region of residence, number of living siblings at home, maternal education level, and maternal smoking during pregnancy. No indicates no respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in a healthcare encounter. Abbreviations: ED, emergency department visit; Hosp, hospitalization; OPV, outpatient visit; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

The relationship between infant RSV bronchiolitis and outcomes was unchanged when adjusting for maternal asthma in the subset of children whose mothers were enrolled in TennCare prior to delivery and for whom a maternal history could be ascertained (n = 51 475). Compared to those who did not experience RSV bronchiolitis in the first 6 months of life, the adjusted odds of ever having pneumonia, otitis media, and/or an antibiotic fill in the second 6 months of life were 1.34 (95% CI, 1.13–1.59), 1.26 (95% CI, 1.18–1.34), and 1.23 (95% CI, 1.14–1.34), respectively.

DISCUSSION

RSV bronchiolitis during the first 6 months of life was associated with an increased risk of subsequent pneumonia, otitis media, and antibiotic prescription fills. A dose-dependent relationship was observed between the increasing severity of RSV bronchiolitis during the first 6 months of life and the risk of developing pneumonia, but not the risk of developing otitis media or filling an antibiotic in the second 6 months of life. However, most antibiotic prescriptions were likely for otitis media [5], consistent with the nearly identical patterns seen in the otitis media and antibiotic prescription fill data.

Previous reports on the incidence of otitis media following RSV infection have been conflicting and limited by small sample sizes. Kafetzis et al [6] reported no difference in the incidence of otitis media between RSV-positive and RSV-negative infants at both 6 weeks and 6 months after discharge. Conversely, Kristjansson et al [7] noted increases in the incidences of otitis media and antibiotic use among children who had previously had RSV, compared to those who had no history of infection. Increased risk of pneumonia (with and without wheezing) following RSV infection have been previously found within 2 African populations [8, 9]. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to systematically and simultaneously assess the risk of the most common non-wheezing respiratory sequela during infancy subsequent to RSV bronchiolitis.

There are several potential biologic mechanisms by which RSV might contribute to subsequent adverse health outcomes. An RSV infection of the respiratory epithelium has been shown to decrease mucociliary clearance of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae while promoting bacterial adherence, virulence, and an increased bacterial load [10]. The durations of the cytopathic and functional effects on the epithelium and microbiota are not known but could contribute to later infant respiratory morbidity. In addition, infant RSV infection leads to a skewed Type 2 immune response that is commonly associated with allergic airway inflammation, potentially predisposing children to pathogens within the middle ear and respiratory tract [11]. In support of an impact of RSV prevention on later respiratory morbidity, one of the first trials of RSV intravenous immunoglobulin (an immunoglobulin from normal, healthy individuals that contains a high concentration of protective antibodies against RSV, and likely other pathogens) in high-risk infants not only reduced the incidence of RSV-associated hospitalizations, but also resulted in lower rates of otitis media [12].

We acknowledge some limitations of this study. Although we could not confirm RSV infections by laboratory testing, we used an algorithm that has been previously validated based on viral identification [4]. Pneumonia and otitis media were ascertained using administrative data, which could lead to misclassification. However, the use of ICD-9 codes to identify these conditions has been previously validated [13].

Our findings provide evidence of significant, longer-term burdens of non-wheezing respiratory outcomes in childhood following RSV bronchiolitis. These findings support the potential long-term impacts of RSV vaccine programs for healthy children and may have particular impact on the uptake of these vaccines in low- and middle-income countries. Future studies to confirm causality, including randomized, controlled trials or observational follow-ups following vaccine introduction, are needed to demonstrate whether the prevention of RSV can reduce the incidences of pneumonia, otitis media, and antibiotic use throughout early childhood.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the Tennessee Bureau of TennCare and the Tennessee Department of Health, Office of Policy, Planning & Assessment, for providing the study data.

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of is the National Institutes of Health.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number 5 T32 HL087738-14 to B. M. D.; grant number K24 AI 077930 to T. V. H.).

Potential conflicts of interest. T. V. H. has received grants from the National Institutes of Health and the World Health Organization and personal fees for participation in the Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infant/Maternal Health Advisory Board from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Boyce TG, Mellen BG, Mitchel EF Jr, Wright PF, Griffin MR. Rates of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection among children in Medicaid. J Pediatr 2000; 137:865–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Red book: 2012. Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29 ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Openshaw PJM, Chiu C, Culley FJ, Johansson C. Protective and harmful immunity to RSV infection. Annu Rev Immunol 2017; 35:501–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Turi KN, Wu P, Escobar GJ, et al. Prevalence of infant bronchiolitis-coded healthcare encounters attributable to RSV. Health Sci Rep 2018; 1:e91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vaz LE, Kleinman KP, Raebel MA, et al. Recent trends in outpatient antibiotic use in children. Pediatrics 2014; 133:375–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kafetzis DA, Astra H, Tsolia M, Liapi G, Mathioudakis J, Kallergi K. Otitis and respiratory distress episodes following a respiratory syncytial virus infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 2003; 9:1006–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kristjánsson S, Skúladóttir HE, Sturludóttir M, Wennergren G. Increased prevalence of otitis media following respiratory syncytial virus infection. Acta Paediatr 2010; 99:867–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Munywoki PK, Ohuma EO, Ngama M, Bauni E, Scott JA, Nokes DJ. Severe lower respiratory tract infection in early infancy and pneumonia hospitalizations among children, Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19:223–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weber MW, Milligan P, Giadom B, et al. Respiratory illness after severe respiratory syncytial virus disease in infancy in The Gambia. J Pediatr 1999; 135:683–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brealey JC, Sly PD, Young PR, Chappell KJ. Viral bacterial co-infection of the respiratory tract during early childhood. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2015; 362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Legg JP, Hussain IR, Warner JA, Johnston SL, Warner JO. Type 1 and type 2 cytokine imbalance in acute respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 168:633–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reduction of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization among premature infants and infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia using respiratory syncytial virus immune globulin prophylaxis. The PREVENT Study Group. Pediatrics 1997; 99:93–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cadieux G, Tamblyn R. Accuracy of physician billing claims for identifying acute respiratory infections in primary care. Health Serv Res 2008; 43:2223–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.