Abstract

Stigmatisation and discrimination are common worldwide, and have profound negative impacts on health and quality of life. Research, albeit limited, has focused predominantly on adults. There is a paucity of literature about stigma reduction strategies concerning children and adolescents, with evidence especially sparse for low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). This systematic review synthesised child-focused stigma reduction strategies in LMIC, and compared these to adult-focused interventions.

Relevant publications were systematically searched in July and August 2018 in the following databases; Cochrane, Embase, Global Health, HMIC, Medline, PsycINFO, PubMed and WorldWideScience.org, and through Google Custom Search. Included studies and identified reviews were cross-referenced. Three categories of search terms were used: (i) stigma, (ii) intervention, and (iii) LMIC settings. Data on study design, participants and intervention details including strategies and implementation factors were extracted.

Within 61 unique publications describing 79 interventions, utilising 14 unique stigma reduction strategies, 14 papers discussed 21 interventions and 10 unique strategies involving children. Most studies targeted HIV/AIDS (50% for children, 38% for adults) or mental illness (14% vs 34%) stigma. Community education (47%), individual empowerment (15%) and social contact (12%) were most employed in child-focused interventions. Most interventions were implemented at one socio-ecological level; child-focused interventions mostly employed community-level strategies (88%). Intervention duration was mostly short; between half a day and a week. Printed or movie-based material was key to deliver child-focused interventions (37%), while professionals most commonly implemented adult-focused interventions (53%). Ten unique, child-focused strategies were all evaluated positively, using a diverse set of scales.

Children and adolescents are under-represented in stigma reduction in LMIC. More stigma reduction interventions in LMIC, addressing a wider variety of stigmas, with children as direct and indirect target group, are needed.

This systematic review is registered under International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews PROSPERO, reference number #CRD42018094700.

Keywords: Stigma, Discrimination, Child, Adolescent, LMIC, Low- and middle-income countries, Intervention, Strategy

1. Introduction

Stigma has been described as a deeply discreditable or undesirable attribute (Goffman, 1963) and further conceptualised as a social process of labelling, stereotyping, and prejudice causing separation, devaluation, and discrimination (Link and Phelan, 2001). Stigmatisation can occur when a person or a group has an identity that is perceived to deviate from locally accepted norms, with many examples, including but not limited to one’s sexual orientation (Cange et al., 2015), having experienced childhood sexual abuse (Barr et al., 2017), living with chronic neurological and mental disorders (Mukolo et al., 2010) or having a disability (Zuurmond et al., 2016).

Stigma is common worldwide, both in high income countries (HIC) and low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), and typically functions to keep people in the group by enforcing social norms, keep people away from the group as a strategy to avoid disease and keep people down to exploit and dominate (Bos et al., 2013). Stigma has been described as a diffuse concept (Manzo, 2004; Pescosolido and Martin, 2015), occurring in several forms for both the populations with lived experience and the general population. Building on previous research, these forms have been recently further categorised in action-oriented and experiential stigma; with self-stigma, provider-based stigma, courtesy stigma, public stigma, and structural stigma as action-oriented, and anticipated, received, endorsed, enacted and perceived stigma as experiential (Pescosolido and Martin, 2015). From whichever perspective, it has profound negative impact on physical and psychosocial well-being (Cross et al., 2011; Nayar et al., 2014), can be more detrimental than the burden of the condition itself (Gronholm et al., 2017) and can impede child health and development outcomes (Nayar et al., 2014). Stigma is inversely correlated with quality of life (Brakel et al., 2010; Janoušková et al., 2017) as it hampers access to services, facilitates harmful coping strategies, decreases support seeking behaviour and disclosure or treatment adherence, is socially and economically restricting, and negatively affects participation and decision-making (Link et al., 1989; Sengupta et al., 2011; Mak et al., 2017; Kaddumukasa et al., 2018).

Stigmatisation concerning children remains under-researched, even with their unique risks for being stigmatised given their lack of power and lower social status in many LMIC contexts (Mukolo et al., 2010). A recent scoping review of health-related stigma outcomes in LMIC indicated the under-representation of children and adolescents in the included studies on high-burden diseases as HIV, tuberculosis (TB), and epilepsy (Kane et al., 2019). A qualitative synthesis on stigma, HIV, and health demonstrated the paucity of studies focusing on children and youth, with only 11% of the included studies focusing on this specific population, of which only one took place in a LMIC (Chambers et al., 2015). Kaushik et al. (2016) recently addressed a knowledge gap concerning stigma of mental illness in children and adolescents globally, however none of the included qualitative studies with child participants were conducted in LMIC.

Stigma reduction interventions aim to reduce both incidence and burden of stigma. Although there appears to be an increase recently in the number of interventions across a wider range of stigmas (Pescosolido and Martin, 2015), there is still a dearth of evidenced interventions to address stigma (Bos et al., 2013), especially in LMIC (Thornicroft et al., 2016; Kemp et al., 2019) with research on children and stigma specifically scarce (Dalky, 2012; Clement et al., 2013). Views on rigour and quality of intervention evaluations diverge, with some authors emphasising low quality (Cross et al., 2011; Bos et al., 2013; Mak et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2019) and others highlighting the presence of moderate to high quality studies (Stangl et al., 2013). There is consensus on the need to use validated, cross-culturally tested instruments (Cross, 2006; Brakel et al., 2010; Bos et al., 2013; Stangl et al., 2013), based on theory (Hanschmidt et al., 2016) and measuring clear constructs of stigma (Brown et al., 2003; Birbeck, 2006; Pescosolido and Martin, 2015).

Despite many groups being subject to stigma, stigma reduction interventions tend to be silo-ed and isolated, focusing on a single stigmatised group, using a disease-specific approach in LMIC (Brakel et al., 2019), mainly for HIV/AIDS (Brown et al., 2003; Nyblade et al., 2009; Sengupta et al., 2011; Stangl et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2018; Kemp et al., 2019), mental illness (Birbeck, 2006; Semrau et al., 2015; Thornicroft et al., 2016; Gronholm et al., 2017; Xu, Huang, Koesters and Ruesch, 2017a; Xu, Rüsch, Huang and Koesters, 2017b; Heim et al., 2018; Kaddumukasa et al., 2018), tuberculosis (Sommerland et al., 2017) and leprosy (Cross, 2006; Brakel et al., 2010). Similarly, in LMIC few reviews have synthesised across stigmatised groups (Heijnders and VanderMeij, 2006; Cross et al., 2011; Hofstraat and Brakel, 2016; Kemp et al., 2019) and few have compared intervention components (Cook et al., 2014; Sommerland et al., 2017; Xu, Rüsch, et al., 2017). Importantly, few have synthesised stigma reduction interventions from the viewpoint of children and adolescents (Clement et al., 2013; Nayar et al., 2014).

The focus of this review is child and adolescent stigma interventions, and the aim of this paper is to synthesise the strategies of stigma reduction interventions in LMIC across stigmatised groups, focusing specifically on strategies applied in relation to children. We have included adult literature for two reasons: first, as point of comparison to frame the findings on differences and similarities with intervention approaches for children and adolescents; and second, because some studies included both adult and child populations.

2. Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Moher et al., 2009).

2.1. Identification of studies

This review analysed published literature of studies describing interventions with a primary objective of reducing stigma. Studies were sought in eight published literature databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, Medline, Cochrane, Global Health, EMBASE, Healthcare Management Information Consortium (HMIC) and WorldWideScience.org; and three Custom Google Search engines that allow searching a set of websites. Two Custom Google Search engines shared by Yale University Library (Public Health Information Resources, 2018) were searched for pre-identified websites of 1803 local non-governmental organisations and 409 inter-governmental organisations. An additional Google Custom Search was designed to include 29 websites of organisations with an expected focus on stigma reduction. Included studies and identified reviews were cross-referenced for additional eligible studies.

2.2. Search terms

Search terms were pre-defined and categorised in the concepts of (a) stigma, (b) intervention, and (c) LMIC setting. Stigma was searched in the title, while terms for intervention and setting were searched via title and/or abstract, depending on database functionality. A full list of search terms and breakdown of database-dependent fields is available in Supplementary Table S1.[INSERT LINK TO ONLINE FILE A] Literature database searches were conducted in July and August 2018 while custom Google Custom Searches were run in November 2018. To reflect changes in search strategy, on 27 May 2019 the PROSPERO record was adjusted to exclude grey literature.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Identified studies were included if they were set in LMIC as defined by the World Bank List of Economies as per June 2017. Studies were required to have a primary objective of reducing stigma and describing an intervention, and interventions were required to have completed or reported outcomes. Articles had to be peer-reviewed. In addition, they were not restricted by publication date, source or language, nor by stigmatised group or intervention target population. Studies were excluded if they; (a) did not include “stigma” in the title, (b) were set in HIC as defined by the World Bank List as per June 2017, (c) did not describe an intervention or (d) had no outcomes or results reported. Studies were also excluded if their full texts were not identified and continued to be missing after three attempts at contacting the first authors or identified study contacts. Discrepancy on inclusion/exclusion was discussed between two researchers [KH, CH] before a final decision was made. In case of continued disagreement, a decision was made through the involvement of a third researcher [MJ].

2.4. Study selection and data extraction

After removing duplications, titles were first screened, after which articles were reviewed based on abstract. Next, full texts of articles were reviewed to assess eligibility. A second researcher [KH] reviewed approximately 15% of the titles and 25% of abstracts to review assessment of the in- and exclusion process. Of the full texts, 100% were screened by two researchers [KH, CH]. Data from included studies were extracted and entered into an Excel document for review. Key data points extracted included population subject to stigma, study design, intervention aims, intervention components, intervention implementation elements, target variants and outcomes/results. Data extraction for all studies was conducted and reviewed by two researchers [KH, CH], who independently reviewed and then compared the first 10% of the text and discussed discrepancies. The rest of the data was extracted by one reviewer [either CH or KH] and checked by the other [either CH or KH], with a third researcher in case of lack of clarity or disagreements [MJ].

2.5. Data analysis

After summarising results in the data extraction table, researchers categorised the interventions based on their strategies or components and socio-ecological levels they belong to, as well as the type of stigmatisation they targeted. The process of categorisation of strategies was inspired by the distillation and matching model (DMM) by Chorpita and colleagues (Chorpita et al., 2005). A similar strategy has been used in other systematic reviews (Jordans et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2017). We used the socio-ecological levels (Bronfenbrenner, 1977) and an initial list of stigma reduction strategies divided under these socio-ecological levels (Heijnders and VanderMeij, 2006) as a starting point to code and categorise the strategies. We expanded this list by adding another strategy and making a sub-division within existing strategies to allow detailing. The results of evaluation studies were coded by three researchers [KH, CH, MJ] using the following codes: negative, neutral or positive results. If a primary scale was identified, the outcome for this scale was leading in the coding. In case no primary scale was identified and the used scales showed a mix of results including positive, the outcomes were coded as positive, except if there was one scale demonstrating a negative result. In this case the outcome was coded as negative.

To distil information at the level of stigma categories, we used the stigma framework of Pescosolido and Martin (2015) with two main categories: experiential and action-oriented stigma. As not every study explicitly stated which category was measured, determinants were assigned based on the study’s explanation compared to the description as formulated by (Pescosolido and Martin, 2015), and the measurement used. Assignments were discussed between two researchers [KH, CH] who independently reviewed content, discussed disagreements, and made a final decision.

After key data were coded and categorised, researchers performed a thematic sub-analysis to investigate the frequency and variety of intervention components across study, intervention and stigma characteristics, comparing against the presence or absence of children and adolescents as an intervention target group.

3. Results

3.1. Included studies

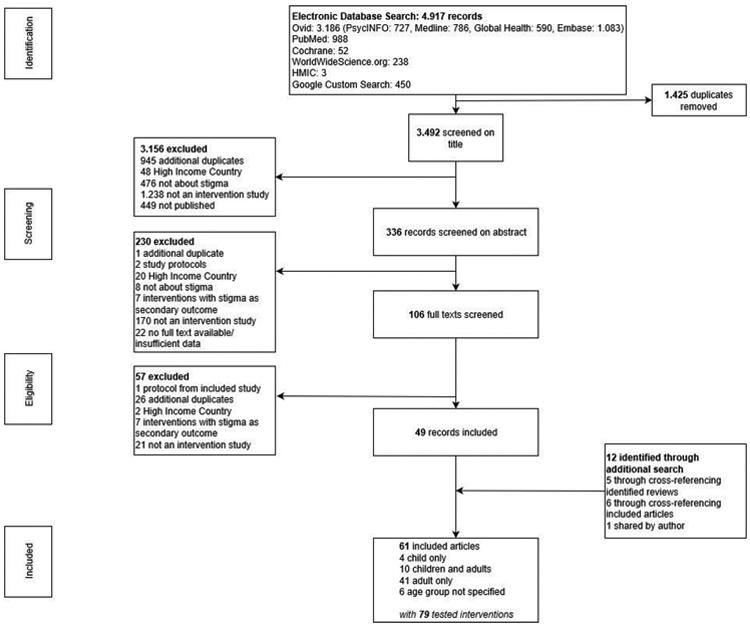

The search yielded 4917 articles; 1425 of which were duplicates. Of the 3492 remaining studies, 3156 were excluded during title screening and 230 were excluded following a review of abstracts, leaving 106 studies for full-text review. Of these, 57 studies were excluded; identifying 49 included studies to be included in the study. Twelve additional studies were added through cross-referencing of included studies and identified reviews, resulting in a total of 61 studies in the review (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Review flow diagram.

In this review, we compared studies, interventions and strategies focusing on children and adolescents, either as target group alone or with adults, or as impact group, with those focusing on adults.

3.2. Study characteristics

Of the 61 included studies, published between 2002 and 2018, only 14 (23%) had a child focus, either as direct target group in isolation (n = 4, 29%), together with adults (n = 9, 64%) or as indirect target group (n = 1, 7%). The other 47 studies (77%) focused on adults or a non-specified audience. The studies (see Table 1 for the main characteristics of the included studies) were conducted in 26 countries, with two taking place in multiple countries. Using the WHO regional classification, 42 interventions (69%) were conducted in South-East Asia and Africa (n = 11, 79% children/adolescents vs n = 31, 66% adults – in the remainder of the results section we will compare these in the same order), of which 13 interventions in India and 8 in South Africa. Nineteen studies were conducted in the Western Pacific, Europe, Eastern Mediterranean, and the Americas. RCTs were the least used study design both for child-focused (n = 2, 14%) and adult-focused interventions (n = 5, 11%), next to qualitative and anecdotal intervention study design (n = 3, 21% vs n = 8, 17%), with uncontrolled pre-post studies being most used in studies with a child focus (n = 5, 36% vs n = 14, 30%), followed by quasi-experimental (n = 4, 29% vs n = 20, 43%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study, year | Country (Setting) |

Stigma label(s) | Age intervention participants (specification) |

Delivery Channelsa |

Contact hours |

Intervention description |

Intervention Components |

RD b |

Results c (measure) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions focused only on children/adolescents | |||||||||

| Ritterbusch (2016) | Colombia (community, health centre) | Mental Illness (substance abuse), Being street-based | Adolescents (People with lived experience) | i | Not reported | Long-term participatory action research including visual research component | Empowerment, Advocacy | 4 | |

| Alemayehu & Ahmed (2008) | Ethiopia (school) | HIV/AIDS | Adolescents (pupils) | Arm 1: l Arm 2: b Arm 2: b Arm 4: b, l |

Half day (arm 1, 2, 3 and 4) | Arm 1: interpersonal dialogue Arm 2: Printed Material Arm 3: short movie Arm 4: combination of all 3 |

Education (all arms) | 2 | All positive (no name) pre-tested questionnaire on blame, coercion, avoidance, sympathetic feelings |

| El-Setouhy & Rio (2003) | Egypt (school) | Filariasis | Children/adolescents (pupils + People living close to them) | a, b | Half day | Comic book read in class and brought home | Education | 3 | |

| Raizada et al. (2004) | India (school) | HIV/AIDS | Adolescents (pupils) | Arm 1: l Arm 2: b Arm 2: b Arm 4: b, l |

Half day (arm 1, 2, 3 and 4) | Arm 1: interpersonal dialogue Arm 2: Printed Material Arm 3: short movie Arm 4: combination of all 3 |

Education (all arms) | 2 | All positive (own: no name) coercive attitude, avoidance, blaming, sympathetic feelings) |

| Interventions focused on children//adolescents and adults | |||||||||

| Yan et al. (2018) | China (school) (+Australia) | Mental Illness (Anorexia) | Adolescents/adults (students) | j | Half day | Social consensus – vignette-based and allocation to in-, out- or neutral group | Social Consensus | 2 | Positive (for in-group) (SDS, Characteristics Scale, Affective Reaction Scale, Severity Scale, Blameworthiness Scale) |

| Lusli et al. (2016) | Indonesia (community, family) | Leprosy | Adolescents/adults (People with lived experience, People Living Close to them, service providers) | f, g | Half day | Rights- and knowledge-based individual, family and group counselling (CBT principles applied, 5 sessions) | IC-CBT, Group Counselling, Care & Support | 1 | Positive SARI Stigma Scale, Participation Scale |

| Jain et al. (2013) | Thailand (community) | HIV/AIDS | Adolescents/adults (People with lived experience + mix) | f, g | Not computable (different dosages) | Campaigns, funfairs, IEC and monthly banking days | Empowerment, Education, Contact | 3 | |

| Dalen (2009) | Uganda (community, schools) | Orphan-hood | Children + adults (mix) | a, l | Not reported | Various: house repair, school fees, counselling/guidance. Income generating activities, awareness raising workshops | Empowerment, Group Counselling, Education | 4 | |

| Geibel et al. (2017) | Bangladesh (health centre) | HIV/AIDS + Sexual Behaviour | Adults (service providers) (impact children) | a | 1–3 days | Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights training, including supplement training on stigma | Training | 3 | |

| Chidrawi et al. (2014) | South Africa (community) | HIV/AIDS | Adolescents/adults (People with lived experience + People living close to them) | f, g, i | 1–2 months (estimate, different dosages) | Community-based intervention with 2-day lecture and activity based workshop, education/contact workshops and implementation of joint projects | Empowerment, Education, Contact | 3 | |

| Zeelen et al. (2010) | South Africa (health centre) | HIV/AIDS | Adolescents/adults (mix) | e | Not reported | Edutainment: storyteller uses dialogue between animals as metaphor to create openness in waiting room of clinic | Education | 4 | |

| Creel et al. (2011) | Malawi (community) | HIV/AIDS | Adolescents/adults/elderly (mix) | Arm 1: c Arm 2: c, i | Half day (both arms) | Both arms: radio diary (PWLE telling about everyday life). 2nd arm includes group discussion. | Education, Contact (arm 1 and 2) | 1 | Positive (adapted, no name) fear, shame, blame and judgement, willingness to disclose |

| Elafros et al. (2013) | Zambia (health centre) | Mental Illness (epilepsy) | Adolescents/adults (People with lived experience) | a, i | 1–3 days | Monthly peer support groups to share life experiences, for medical questions clinical officer present | Empowerment, Self-Help | 3 | |

| O’Leary et al. (2007) | Botswana (community) | HIV/AIDS | Adolescents + Adults (mix) | C | Not reported | Edutainment: story line on HIV stigma within the soap “the bold and the beautiful” | Education | 2 | Positive (no name) stigma scale on attitudes and intent |

| Interventions focused only on adults | |||||||||

| Li et al. (2018) | China (health centre) | Mental Illness (schizo-phrenia) | Adults (People with lived experience) | A | 1–3 days | Psychoeducation (7 modules), Social Skills Training (6 modules), CBT (3 steps) | IC-CBT, Empowerment | 1 | Positive DISC, ISMI |

| Maulik et al. (2017) | India (community) | Mental Illness | Adults (mix) | b, c, d | Not computable (different dosages) | Multi-media anti-stigma campaign sharing (interactive) information and testimonies | Education, Contact | 3 | |

| Lyons et al. (2017) | Senegal (community, health centre) | Sexual behaviour (MSM/FSW) | Adults (vulnerable population + service providers) | g, j, l | Not computable (different dosages) | Integrated intervention: community intervention, clinical and web-based referral system | Empowerment, Training, Policy | 3 | |

| Lohiniva et al. (2016) | Egypt (health centre) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (service providers) | l | 1–3 days | Hospital-based inter-active training programme (5 modules) | Training | 2 | Positive (own) Stigma Score Fear- and value-based stigma |

| Nyblade et al. (2018) | India (Health centre) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (Service Providers) | g, i, j | Half day | Blended learning approach combining tablet and in-person sessions | Training | 3 | |

| Kutcher et al. (2016) | Tanzania (school) | Mental Illness | Adults (service providers) | a | 1–3 days | Training teachers on the African Guide mental health literacy curriculum (6 modules) | Training | 3 | |

| Pulerwitz et al. (2015) | Vietnam (community, health centre) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (service providers) | a, g (both arms) | 1–3 days (arms 1 and 2) (estimate) | Staff training, hospital policy development and supplies provision (1st arm: focus on fear, 2nd arm: more intense training + focus on value/social stigma) | Training, Policy (arm 1 and 2) | 2 | Both positive (adapted) Stigma score Enacted Stigma, Social Stigma, Fear-based stigma |

| Li et al. (2014) | China (health centre) | Mental Illness | Adults (service providers) | A | 0,5 day–1 day | Mental health training course (2 parts) | Training | 3 | |

| Nyamathi et al. (2013) | India (community, family) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (People with lived experience) | a, f | 1–3 days | Empowering, educational and support intervention (Asha-Life) | IC, CBR, Empowerment | 2 | Positive (adapted, no name) Internalised stigma, Disclosure Avoidance Scale |

| Li et al. (2013) | China (health centre) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (service providers) | d, f | 1–3 days | Behavioural and structural change training programme (4 sessions) through popular opinion leaders + 3 refresher | Training | 1 | Positive (adapted, no name) Prejudice (own) providers’ avoidance intent |

| Augustine et al. (2012) | India (health centre) | Leprosy | Adults (People with lived experience) | a | 1–2 weeks | Social Skills training (10 day sessions) with role plays and videos | Empowerment | 3 | |

| Nambiar et al. (2011) | India (health centre) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (People with lived experience, People living close to them, service providers) | c, e | 1–3 days | Educational radio and theatre programme with messages, testimonies and Q&As on the radio | Empowerment | 2 | Positive (adapted, no name) Felt, disclosure and enacted stigma |

| Macq et al. (2008) | Nicaragua (health centre, family) | TB | Adults (People with lived experience + service providers) | a | Not computable | Municipal teams implementing self-identified patient-centred packages including TB clubs and home visits | Self-Help, HCT, Training | 2 | Positive (Rosenberg scale) as determinant for Internalised social stigma |

| Lapinski & Nwulu (2008) | Nigeria (community) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (general population) | b | Half day | Edutainment: fictional story of relatable character contracting HIV, phase of rejection and then acceptance | Education | 2 | Neutral (items adopted) Coercive policies attitudes scale, avoidance scale, blame scale |

| Finkelstein et al. (2007) | Russia (school) | Mental Illness | Adults (students) | Arm 1: j Arm 2: b |

Not reported | 1st arm: short interactive educational messages on stigma 2nd arm: brochures on stigma | Training (arm 1 and 2) | 2 | Both positive (CAMI, SDS) |

| Wu et al. (2008) | China (health centre) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (service providers) | a | Half day | Interactive training programme, including testimonies, role plays and group discussions | Training | 2 | Positive (No name) Attitudes towards PLWHA |

| Apinundecha et al. (2007) | Thailand (community) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (People with lived experience + People living close to them + mix) | d, f, i | Not reported | Participatory community action research with leader engagement, information-sharing and cooperation | Empowerment, Education, Contact, Popular Opinion Leader | 2 | Positive (adapted, no name) Community and family stigma towards PLWHA, PLWHA perceptions of stigma, PLWHA self-stigma, Community stigma towards family of PLWHA |

| Cross & Choudary (2005) | Nepal (community) | Leprosy | Adults (People with lived experience) | g | Not reported | Stigma Eliminating Programme: empowerment through self-care, livelihood and contribution to community development | Empowerment, Self-Help | 2 | Positive Participation Scale |

| Doosti-Irani et al. (2017) | Iran (community) | Diabetes | Adults (People with lived experience + People living close to them + service providers + mix) | k | Not reported | Variety of community, family and organisational activities, such as diabetes walking tour, use of media, conference, contact, changing diabetes centre policies | Empowerment, Care & Support, Policy, Contact, Education, Advocacy | 4 | |

| Rai et al. (2018) | Nepal (health centre) | Mental Illness | Adults (People with lived experience) | g | 1–2 weeks | Participatory research training where service users use PhotoVoice as advocacy and empowerment tool, and provide input into mhGAP training | Empowerment, Training | 4 | |

| Ahuja et al. (2017) | India (school) | Mental Illness | Adults (students) | e, g, i | Half day | One-time education and contact moment, with PowerPoint, dance drama and information from person with lived experience | Education, Contact | 3 | |

| Hofmann-Broussard et al. (2017) | India (community) | Mental Illness | Adults (service providers) | a, f, g | 4–7 days | Manual-based mental health training (12 modules), face-to-face with person with lived experience (recovery) | Training | 2 | Positive (own) Attitudes |

| Cornish (2006) | India (community) | Sexual Behaviour (sex work) | Adults (People with lived experience) | a, g | Not reported | Community intervention: education sessions to PWLE, collective action, meet politicians/academics at press conferences | Empowerment, Self-Help, Advocacy | 4 | |

| Logie et al. (2019) | Swaziland/Lesotho (family + health centre + community) | Sexual Behaviour (LGTBQI) | Adults (students + service providers + mix) | e | Half day | Edutainment: theatre intervention with 3 skits on LGBT stigma, active audience involvement in identifying proper way forward | Education | 4 | |

| Shilling et al. (2015) | Chile (health centre) | Mental Illness | Adults (People with lived experience) | a, i | 1–3 days | Recovery-oriented 10 session constructivist psychoeducation/group sessions (Tree of Life) | Group Counselling | 4 | |

| Shah et al. (2014) | India (health centre) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (Students) | a, g | Half day | PowerPoint and group discussions and shared experience from PWLE | Training | 2 | Positive (no name) intent to discriminate, attitudes towards PLWHA, endorsing coercion, blame |

| Catalani et al. (2013) | India (community) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (vulnerable population) | b (both arms) | Half day (both arms) | Storytelling on HIV stigma through movie (arm 1: feature film, arm 2: illustrated video) | Education, Contact | 2 | Both positive (FGD) attitudes, fear of casual contact |

| Dadun et al. (2017) | Indonesia (community) | Leprosy | Adults ((People with lived experience + People living close to them + mix) | Arm 1: a, g, i Arm 2: a, f, g Arm 3: a, f, g, i |

Not reported | Socio-Economic: loans, business training (arm 1 and 2) Counselling: skills building, peer services (arm 2 and 3) Contact: contact, dialogue interaction (arm 1 and 3) |

Arm 1: Contact, Empowerment Arm 2: Group Counselling, Empowerment Arm 3: Group Counselling, Contact |

1 | All three Positive SARI, EMIC, SDS |

| Monteiro (2014) | Botswana (school) | Mental Illness | Adults (students) | I | 1–2 weeks | Psychopathology course using a didactic approach, incorporation of unplanned self- and peer-disclosure | Training | 4 | |

| Go et al. (2017) | Vietnam (community) | HIV/AIDS + Mental Illness (substance abuse) | Adults (People with lived experience | Arm 1; a Arm 2: b, f Arm 3: a, b, f |

Arm 1: half day (estimate) Arm 2: 1 day (estimate) Arm 3: 1–3 day (estimate) |

Arm 1: Individual and Group Counselling, including PLC Arm 2: Community-wide programme, showing fictional video + follow up sessions Arm 3: combination of 1 and 2 |

Arm 1: IC, Group Counselling Arm 2: Contact, Education Arm 3: combination of arm 1 and 2 |

1 | All three neutral HIV Stigma, IDU Stigma |

| Sermrittirong et al. (2014) | Thailand (community + health centre + family) | Leprosy | Adults (mix + service providers) | Arm 1: a, f Arm 2: a, f Arm 3: f |

Not computable (arm 1, 2 and 3) | Arm 1: formal health care system Arm 2: local volunteers Arm 3: self-help groups |

Arm 1: HCTs, Training, Education Arm 2: IC, Care & Support, Training, Education Arm 3: Self-Help, Empowerment, Education |

2 | 1.neutral 2. positive 3. positive EMIC |

| Francis & Hemson (2006) | South Africa (school) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (students) | i | Half day (estimate) | Participatory visual arts with dialogue | Education | 4 | |

| Uys et al. (2009) | Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania (health centre) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (service providers + People with lived experience) | a, g | 2 weeks–1 month | Information-based and empowerment training based on education and contact | Empowerment, Training | 3 | |

| Tshabalala & Visser (2011) | South Africa (health centre) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (People with lived experience) | a | 1–3 days | 8 CBT sessions, addressing self-worth, guilt, positive reframing, coping skills | IC-CBT | 2 | Positive serithi internalised stigma scale, enacted stigma |

| ÜÇOk et al. (2006) | Turkey (health centre) | Mental Illness (schizo-phrenia) | Adults (service providers) | a | Half day | PowerPoint presentation and interactive discussion | Training | 3 | |

| Altindag et al. (2006) | Turkey (school) | Mental Illness (schizo-phrenia) | Adults (students) | a, b, g | 1 day | Lecture, PLWE sharing personal story and an autobiographical film | Training | 2 | Positive (questions based on SDS) attitude towards care and management of people living with schizophrenia) |

| Finkelstein et al. (2008) | Russia (school) | Mental Illness | Adults (students) | Arm 1: j Arm 2: b |

Not reported | Arm 1: self-paced short educational stigma messages, fictional story, triggering emotions Arm 2: Factual stigma brochures |

Training (both arms) | 2 | Both positive CAMI |

| Bayar et al. (2009) | Turkey (health centre) | Mental Illness | Adults (service providers) | j | Half day | Instructive email about stigma on beliefs, occurrence, negative effects and potential actions | Training | 2 | Positive (no scale identified) |

| Koen et al. (2010) | South Africa (community) | HIV/AIDS | Adults (People with lived experience) | a, f | 1–3 days | 8 sessions group counselling about HIV/AIDS, voluntary counselling and testing, stigma and manifestations, coping, disclosure | Group Counselling | 4 | |

| Peters et al. (2015) | Indonesia (community) | Leprosy | Not specified (mix) | g, i | 0,5–1 day (estimate) | Contact intervention, including testimonies and contact events | Education, Contact | 1 | Positive SDS, EMIC, 6QQ |

| Shamsaei et al. (2018) | Iran (health centre) | Mental illness (caregivers) | Adults (People with lived experience) | a | 1 day | In-person education (4 sessions) to provide information about MI, role of family, experiences in stigma and coping skills | Empowerment | 2 | Positive (own questionnaire) |

| Interventions with non-specified age group | |||||||||

| Prinsloo & Greeff (2016) | South Africa (community) | HIV/AIDS | Not specified (People with lived experience + People living close to them) | g, h | Not computable (different dosages) | Community intervention: door-to-door, community workshops, psychodrama, peer support, active PWLE involvement | Self-Help, Empowerment, Contact | 3 | |

| Dharitri et al. (2015) | India (community) | Mental Illness | Not specified (mix) | b, e, l | 1–2 weeks (estimate, different dosages) | Community education intervention including psychoeducation | Education | 3 | |

| Neema et al. (2012) | Uganda (health centre) | HIV/AIDS | Not specified (People with lived experience) | l | Not reported | Edutainment/Creativity intervention in a clinic’s waiting room | Policy | 3 | |

| Raju et al. (2008) | India (community, health centre) | Leprosy | Not specified (mix) | a, d, f | Not reported | Community-based intervention, with a stigma reduction organising committee initiating activities | Care & Support, CBR + Contact, Education | 3 | |

| Boulay et al. (2008) | Ghana (religious site) | HIV/AIDS | Not specified (mix) | c, d | Not reported | National mass media messages and community-level IEC, complemented at congregational level messages of compassion | Education, popular opinion leader | 3 | |

| Arole et al. (2002) | India (community + health centre) | Leprosy | Not specified (People with lived experience + mix) | Arm 1: a, f Arm 2: a |

Not computable (arm 1 and 2) | Arm 1: Integrated community-based primary health care, including case detection Arm 2: Integration of leprosy with other conditions |

Arm 1: CBR, Policy Arm 2: Policy |

2 | Both positive (no name: qualitative) |

a. Delivery Channels: a (professionals), b (printed material/movie-based), c (mass media), d (local leaders), e (local actors), f (lay community workers/members), g (people with lived experience), h (people living close to them), i (research team), i (web-based), k (mix of channels), i (not reported).

b. RD (Research Design): 1 = RCT including comparisons, 2 = pre-post with control, 3 = pre-post without control, 4 = qualitative/anecdotal.

c. Results: only results of research designs 1 and 2 have been captured.

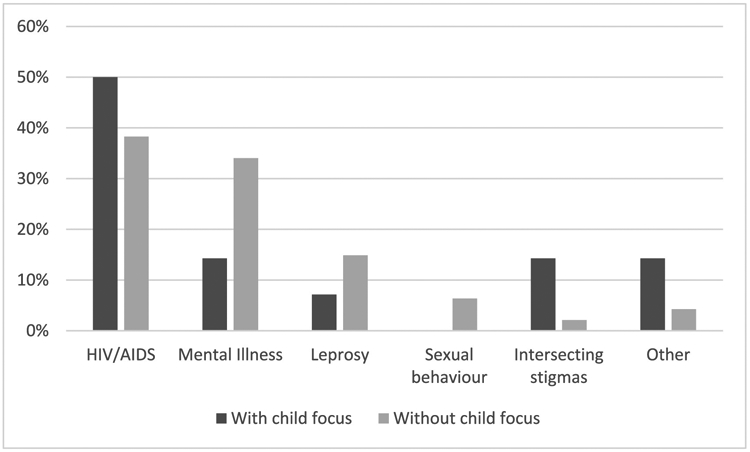

Stigma reduction focused mostly on health-related stigma (n = 13, 93% vs n = 44, 94%), with HIV/AIDS the stigma most addressed in both population groups (n = 7, 50% vs n = 18, 38%). Stigma concerning mental illness is tackled second-most in both population groups (n = 2, 14% vs n = 16, 34%). For studies focusing on children this was either on anorexia or epilepsy specifically, while within adult-focused studies mental illness stigma was mostly targeted broadly (n = 12, 75%), with four studies specifically targeting stigma concerning schizophrenia or caregivers of persons with mental illness (25%). Studies that did not address either HIV/AIDS or mental illness stigma targeted leprosy (n = 1, 7% vs n = 7,15%), sexual behaviour (0% vs n = 3, 6%) or other conditions: filariasis (n = 1, 7% vs 0%), diabetes (0% vs n = 1, 2%), orphan-hood (n = 1, 7% vs 0%) and TB (0% vs n = 1, 2%). Intersecting stigmas were addressed in three studies; two with a focus on children (HIV/AIDS and sexual behaviour, and mental illness (substance abuse) and being street-based), and one adult-focused intervention (HIV/AIDS and mental illness (substance abuse)) (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Proportional division of stigmas addressed in stigma reduction studies with or without a child focus in LMIC.

Two education-based interventions were replicated, one to reduce stigmatisation of mental illness for adults (Finkelstein et al., 2007, 2008) and one focusing on HIV/AIDS stigma for children and adolescents (Raizada et al., 2004; Alemayehu and Ahmed, 2008).

The majority of studies reported action-oriented stigma (n = 57, 93%), of which more than two-thirds only reported action-oriented stigma only (n = 40, 66%). The action-oriented variant mostly reported was public stigma (n = 23, 40%), provider-based stigma (n = 20, 35%) and self-stigma (n = 19, 33%). Courtesy (n = 2, 4%) and institutional stigma (n = 1, 2%) were rarely reported. Experiential stigma was reported in almost one-third of the studies (n = 21, 34%), though seldom in isolation from action-oriented stigma (n = 4, 19%). Perceived stigma (n = 13, 62%) was most often reported, followed by other experiential target variants reported as enacted (n = 9, 43%), received (n = 5, 24%) and anticipated (n = 4, 19%). When we distilled only studies focusing on children it showed a fairly similar pattern for action-oriented stigma (n = 13, 93%) and experiential stigma (n = 4, 28%). Looking at the details however, there were some differences. Within action-oriented stigma, the focus on public stigma was higher (n = 9, 69%), and the focus on self-stigma (n = 2, 15%) and provider-based stigma (n = 1, 8%) lower than in adult-focused interventions. Of the studies that reported experiential stigma, received and perceived stigma were reported most (both n = 2, 50%), followed by anticipated stigma and enacted stigma (both n = 1, 25%). Viewing the stigma types from a target group perspective, most studies (n = 29, 48%) solely focused on the ‘general population’ enacting stigma, followed by studies that purely focused on the population with lived experience (n = 11, 18%). One-fifth focused on both the population with lived experience and general population (n = 12, 20%). In child-focused studies this picture was similar.

3.3. Intervention implementation characteristics

In total, the 61 included studies described 79 interventions. Twenty-one interventions (27%) focused on children as a target group, either in isolation (n = 4) or together with adults (n = 9), or as indirect target group (n = 1). Fifty interventions exclusively targeted adults (n = 50, 63%), and 8 did not specify the age brackets of its target group (10%). The implementation platform most commonly used for child-focused interventions was a school setting (n = 11, 52%). Community settings and health settings were less used in child-focused interventions (n = 8, 38% and n = 4, 19%, respectively) though were the most frequent delivery platforms for interventions with an adult focus (n = 30, 52% and n = 28, 48%, respectively). A family setting (n = 1, 5% vs n = 4, 7%) or religious site (0% vs n = 1, 2%) was rarely used as implementation platform. The majority of the interventions (n = 18, 86% vs n = 46, 79%) were implemented at a single site, and among the interventions implemented across multiple locations (n = 3, 14% vs n = 12, 21%), a combination with at least hospital/health centre and/or community as implementation site were most common in both interventions focusing on children or adults.

The duration of the intervention, or “contact hours”, was often not calculable (n = 1, 5% vs n = 9, 16%) or went unreported (n = 4, 19% vs n = 14, 24%). Of the fifty-one interventions (n = 16, 76% vs n = 35, 60%) where contact hours were reported, interventions most commonly were short and lasted between less than half a day and a week (n = 15, 94% vs n = 30, 86%), with the majority lasting a day or less (n = 13, 87% vs n = 17, 57%). Medium-termed interventions between one week and one month were not observed in child-focused interventions, and they accounted for almost fifteen percent of the contact-hour reporting interventions focusing on adults (n = 5). One child-focused intervention lasted between one and two months, while no interventions were reported to have contact hours beyond two months. The distribution of contact hours demonstrated a significant difference for child-focused interventions and adult-focused interventions, χ (5) = 11.8, p < 0.05, mostly caused by shorter interventions for children.

Of most interventions, the channels of delivery were reported (n = 19, 90% vs n = 55, 95%). Interventions were implemented through a variety of delivery channels. Thirteen child-focused interventions used one delivery channel (68%), while twenty-four adult-focused interventions used two or more modes of delivery (56%). Printed or movie-based material was the most used channel for interventions with a child focus while less so for adult-focused interventions (n = 7, 37% vs n = 10, 18%), followed by members of the research team (n = 4, 21% vs n = 8, 15%) and professionals (n = 4, 21% vs n = 29, 53%). Professionals were the most common delivery channel for adults. Other important delivery channels were people with lived experience (n = 3, 16% vs n = 17, 31%), and lay community members (n = 3, 16% vs n = 14, 25%). Additionally, interventions were implemented by local leaders and actors (n = 1, 5% vs n = 9, 16%), through the web (n = 1, 5% vs n = 5, 9%) and people close by (0% vs n = 1, 2%). Differences between implementation channels used for child-focused and adult-focused interventions were not significant χ (5) = 9.9, p = 0.078.

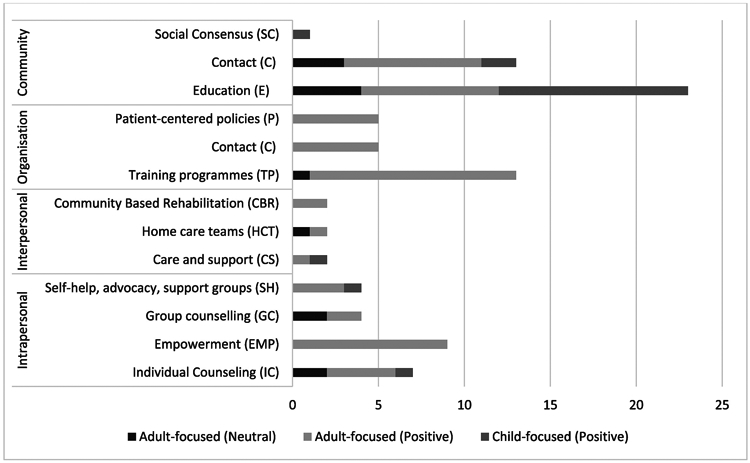

3.4. Intervention strategies

3.4.1. Main strategies

The 21 child-focused interventions implemented 10 unique strategies and 34 strategies in total, while the 58 adult-focused interventions executed 115 strategies within a range of 13 unique strategies. Four strategies accounted for 65% of the total (n = 97), differing in frequency between child- and adult-focused interventions (n = 26, 76% vs n = 71, 62%). The strategy most commonly used for child-focused interventions was community education (n = 16, 47% vs n = 19, 17%) where information was provided to the general public to tackle stigmatising beliefs and adjust attitudes and practice. When adjusting community education to interventions that only target children/adolescents, the strategy was employed at a rate of 90% (n = 9). The second strategy employed was individual empowerment of people with lived experience (n = 5, 15% vs n = 15, 13%) through strengthening people’s livelihood, knowledge on management of the condition, or social skills. The third most commonly implemented strategy was social contact within the community (n = 4, 12% vs n = 14, 12%) where contact between people with lived experience and the general public was facilitated. The fourth strategy, a training programme at service provider level in which staff is trained on stigma versus how to improve services to their clients, was the most employed strategy in adult-focused (n = 23, 20%) though was only used in one child-focused intervention (3%), where adolescents were an indirect target group. Within adult-focused interventions, organisational training programmes were accompanied by social contact between people with lived experience and staff/service providers (n = 9, 8%) and patient-centred policies (n = 8, 7%), though these were implemented as a stand-alone as well.

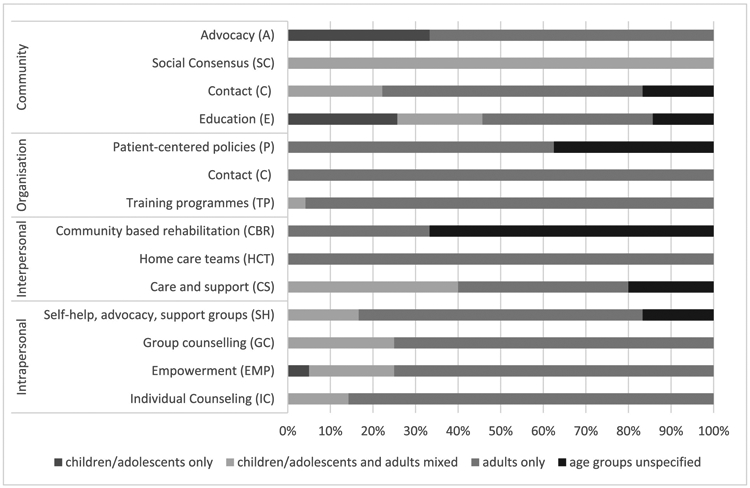

Less frequently employed strategies in both child- and adult-focused interventions (n = 8, 24% vs n = 44, 38%) were group counselling (n = 2, 6% vs n = 6, 5%), individual counselling/cognitive behaviour therapy (n = 1, 3% vs n = 6, 5%), peer groups support (n = 1, 3% vs n = 5, 4%), interpersonal care and support activities for people with lived experience (n = 2, 6% vs n = 3, 3%), and advocacy within the community (n = 1, 3% vs n = 2, 2%). Social consensus (n = 1, 3% vs 0%) was only once used in child-focused interventions, while home-based care (0% vs n = 2, 2%) and community-based rehabilitation (0% vs n = 3, 3%) were only employed in interventions focusing on adults. See Fig. 3 for an overview of which strategies were, in which proportion, used in child- or adult-focused interventions.

Fig. 3.

Proportional division of strategies implemented, divided per socio-ecological level, compared between child- and adult-focused interventions.

3.4.2. Sub-strategies

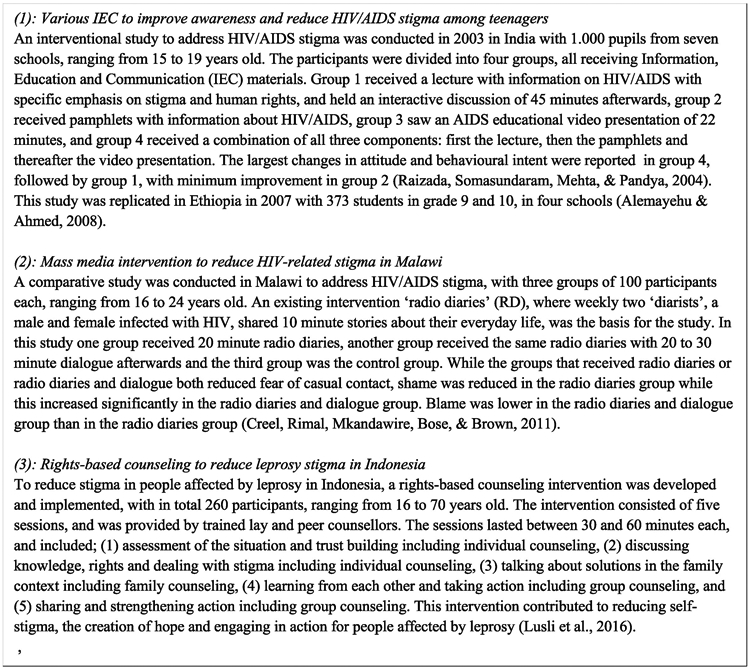

The above-identified four main strategies, namely community education, empowerment, contact within the community and training programmes, are elaborated in this section, through the description of sub-strategies. Further information on the strategies and sub-strategies can be found in Table 2, indicating which were used in child-focused interventions, and how often. Examples of stigma reduction strategies applied to children can be found in Fig. 4.

Table 2.

Adapted Stigma Reduction Intervention Framework (based on Heijnders & Van Der Meij, 2006) including references to included studies.

| Intervention strategy | Intervention sub-strategies, if applicable | Description | Studies describing this (sub)-strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal strategies to reduce stigmatisation | |||

| Individual Counselling | IC | Individual counselling on topics as stress management, positive reframing, challenging dysfunctional beliefs and uncertainty about the future, accompanying person in the stigmatised group to appointments | (Tshabalala and Visser, 2011; Nyamathi et al., 2013; Sermrittirong et al., 2014; Go et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018) |

| IC-CBT | Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: a structured approach in which patients are trained to identify and modify negative beliefs and negative interpretations | (Lusli et al., 2016)b and (Tshabalala and Visser, 2011; Li et al., 2018) | |

| Empowerment | Empowerment - Contact | Facilitated contact between stigmatised, learning from other stigmatised persons | Nambiar et al. (2011) |

| Empowerment – Education | Information for persons from the stigmatised population to understand their condition and to improve it, such as proper nutrition, responsible disclosure management | (Elafros et al., 2013; Chidrawi et al., 2014)b and (Cornish, 2006; Nambiar et al., 2011; Nyamathi et al., 2013; Doosti-Irani et al., 2017; Lyons et al., 2017; Shamsaei et al., 2018) | |

| Empowerment – Livelihood | Strengthening of the economic position of persons from the stigmatised population through monthly supplies, loans or business/agriculture training, basic needs support | (Dalen, 2009; Jain et al., 2013)b and (Cross and Choudary, 2005; Apinundecha et al., 2007; Nyamathi et al., 2013; Sermrittirong et al., 2014; Dadun et al., 2017) | |

| Empowerment – Social Skills | Strengthening the capacity of the persons from the stigmatised population on self-management, social communication skills, reintegration to society | (Ritterbusch, 2016)a and (Augustine et al., 2012; Lyons et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018) | |

| Empowerment – Service User Involvement | Intended and active service user involvement in the stigma reduction intervention strategies | (Uys et al., 2009; Doosti-Irani et al., 2017; Rai et al., 2018) | |

| Empowerment – Value Added | Representatives of the stigmatised population proactively contribute to the wider community | Cross & Choudary (2005) | |

| Group counselling | Sharing, discussing with a group about topic as shared experience, positive identity change, internal stigma, disclosure and coping | (Dalen, 2009; Lusli et al., 2016)b and (Koen et al., 2010; Shilling et al., 2015; Dadun et al., 2017; Go et al., 2017) | |

| Self-help, advocacy, support groups | Mutual support and information exchange, share life experiences, exchange problem-solving advice, encouraging peers to continue or adhere to treatment, collective action | (Elafros et al., 2013)b and (Cross and Choudary, 2005; Cornish, 2006; Macq et al., 2008; Elafros et al., 2013; Sermrittirong et al., 2014; Prinsloo and Greeff, 2016) | |

| Interpersonal strategies to reduce stigmatisation | |||

| Care and support (C&S) | Capacity strengthening of people close to the stigmatised population (e.g. family) about the condition, how to mobilise resources, how to care. | (Lusli et al., 2016)b and (Raju et al., 2008; Sermrittirong et al., 2014; Doosti-Irani et al., 2017) | |

| Home care teams (HCT) | Teams that visit persons from the stigmatised population on a regular basis to strengthen home and self-care | (Macq et al., 2008; Sermrittirong et al., 2014) | |

| Community based rehabilitation (CBR) | Community development for rehabilitation, focusing on reintegration of people from the stigmatised population by organising screening camps, strengthening referral system and follow up of cases, monitoring barriers to treatment adherence | (Arole et al., 2002; Raju et al., 2008; Nyamathi et al., 2013) | |

| Organisational/Institutional strategies to reduce stigmatisation | |||

| Training Programmes within organisations | Training Programme – One Way | Learning takes place through a one-way (one direction) method such as through pamphlets, PowerPoint presentation | (Geibel et al., 2017)b and (Altindag et al., 2006; ÜÇOk et al., 2006; Finkelstein et al., 2008; Macq et al., 2008; Bayar et al., 2009; Uys et al., 2009; Li et al., 2014; Monteiro, 2014; Shah et al., 2014; Pulerwitz et al., 2015; Kutcher et al., 2016; Geibel et al., 2017; Lyons et al., 2017; Nyblade et al., 2018) |

| Training Programme – interactive | Learning takes place through interactive games or discussion methods such as gaming, role plays, movies, drama | (Geibel et al., 2017)b and (ÜÇOk et al., 2006; Finkelstein et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2008; Li et al., 2013; Monteiro, 2014; Sermrittirong et al., 2014; Shah et al., 2014; Pulerwitz et al., 2015; Lohiniva et al., 2016; Geibel et al., 2017; Hofmann-Broussard et al., 2017; Lyons et al., 2017; Nyblade et al., 2018) | |

| Training Programme – Popular Opinion Leader | Strategically making use of influential local leaders to share messages | Li et al. (2013) | |

| Contact | Contact – Direct | Short-term contact within the organisation between staff and people with lived experience to share information and ask questions | (Altindag et al., 2006; Monteiro, 2014; Shah et al., 2014; Hofmann-Broussard et al., 2017; Nyblade et al., 2018) |

| Contact – Direct Cooperation | Interaction or collaboration in the organisation between staff and people with lived experience is facilitated | (Uys et al., 2009; Rai et al., 2018) | |

| Contact – Indirect | Organisational staff has indirect contact with people with lived experience through paper-written, movie-based testimonies or fictional stories | (Altindag et al., 2006; Finkelstein et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2008; Nyblade et al., 2018) | |

| Patient-centred policies | Actions to improve the policy/environment of institutions, such as code of stigma-free practice, better medical environment, universal procedures, confidential referral and integration of services | (Arole et al., 2002; Neema et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013; Pulerwitz et al., 2015; Doosti-Irani et al., 2017; Lyons et al., 2017) | |

| Community strategies to reduce stigmatisation | |||

| Education | Education - One Way | Education through one-way information, such as side slow, lecture, PowerPoint and pamphlets | (Raizada et al., 2004; Alemayehu and Ahmed, 2008)a and (Jain et al., 2013)b and (Apinundecha et al., 2007; Raju et al., 2008; Sermrittirong et al., 2014; Dharitri et al., 2015; Prinsloo and Greeff, 2016; Ahuja et al., 2017; Maulik et al., 2017) |

| Education - Interactive | Education in an interactive manner, such as comic book, role plays, discussion groups, edutainment, theatre | (El-Setouhy and Rio, 2003; Raizada et al., 2004; Alemayehu and Ahmed, 2008)a and (Zeelen et al., 2010; Creel et al., 2011; Jain et al., 2013; Chidrawi et al., 2014)b (Francis and Hemson, 2006; Lapinski and Nwulu, 2008; Raju et al., 2008; Catalani et al., 2013; Sermrittirong et al., 2014; Dharitri et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2015; Prinsloo and Greeff, 2016; Ahuja et al., 2017; Go et al., 2017; Maulik et al., 2017; Logie et al., 2019) | |

| Education - Media | Education through the use of mass media, such as radio and television | (O’Leary et al., 2007; Creel et al., 2011)b and (Boulay et al., 2008; Maulik et al., 2017) | |

| Education - Campaign | In the community going door to door, organising a community walk or awareness raising workshops, community mobilisation | (Dalen, 2009; Jain et al., 2013)b and (Boulay et al., 2008; Doosti-Irani et al., 2017; Go et al., 2017; Maulik et al., 2017) | |

| Education - Popular Opinion Leaders | Local leaders, such as religious leaders, proactively speak out to improve the situation of the stigmatised population through churches or in other places within the community | (Apinundecha et al., 2007; Boulay et al., 2008) | |

| Contact | Contact - Direct | Short-term contact between the general population and representation from the stigmatised population to share information and ask questions | (Jain et al., 2013)b and (Raju et al., 2008; Jain et al., 2013; Chidrawi et al., 2014; Peters et al., 2015; Prinsloo and Greeff, 2016; Ahuja et al., 2017; Dadun et al., 2017; Doosti-Irani et al., 2017) |

| Contact – Direct Cooperation | Interaction or collaboration between the general population and the stigmatised population is facilitated | (Chidrawi et al., 2014)b and (Apinundecha et al., 2007; Raju et al., 2008; Prinsloo and Greeff, 2016) | |

| Contact – Indirect | Community members have indirect contact through paper-written, movie-based testimonies or fictional stories | (Creel et al., 2011)b and (Lapinski and Nwulu, 2008; Creel et al., 2011; Catalani et al., 2013; Peters et al., 2015; Doosti-Irani et al., 2017; Go et al., 2017; Maulik et al., 2017) | |

| Social Consensus | Building on the social consensus theory, aiming to change attitudes by sharing in-/out-group/neutral perceptions | (Yan et al., 2018)b | |

| Advocacy/Protest | Protest campaigns or advocacy actions that aim to influence discriminatory laws through organising conferences, having meetings with policy makers, | (Ritterbusch, 2016)a and (Cornish, 2006; Doosti-Irani et al., 2017) | |

a Strategies or sub-strategies also employed in child-focused interventions.

b Strategy added to Heijnders and Van Der Meij’s framework or further refined through sub-strategies.

Fig. 4.

Exemplar stigma reduction interventions targeting children in LMIC.

Of the 35 interventions using the community education strategy, most were commonly implemented in an interactive manner, in both child-focused (n = 11, 69%) and adult-focused (n = 15, 79%) interventions. This implies that discussion groups and dialogue, role plays, and edutainment shaped the transfer of information. This interactive form was followed in frequency by one-way education (n = 5, 31% vs n = 7, 37%), where information is transferred without interaction. However, where the majority of interactive education community interventions was employed as the only education strategy (n = 7, 63% vs n = 8.53%), one-way education was mostly accompanied by other community education sub-strategies (n = 4, 80% vs n = 6, 86%) as campaigns, media or popular opinion leaders. The latter sub-strategy was only used in adult-focused interventions.

Empowerment strategies were implemented in 20 interventions, of which 25% (n = 5) were child-focused. Strategies to empower have been divided in this review by (1) education, where knowledge about the condition and condition-management is shared, (2) livelihood, where people with lived experience are supported in their livelihood through loans and business training, (3) social skills, where self-management and social communications skills are transferred, (4) service user involvement, where people with lived experience are part of the strategy development and implementation, (5) contact, where people with lived experience get encouraged by other people with lived experience and (6) value added, where people with lived experience proactively contribute to the wider community. Of the interventions using empowerment, the most commonly used sub-strategy was education (n = 2, 40% vs n = 7, 47%), followed by livelihood (n = 2, 40% vs n = 6, 40%) and social skills strengthening (n = 1, 20% vs n = 3, 20%). Service user involvement, contact and value added were only used in adult-focused interventions (n = 5, 34%).

Social contact between the general public and people with lived experience, was used as a strategy in 18 interventions at community level, substantially more in adult-focused (n = 14, 78%) than in child-focused interventions (n = 4, 22%). When the social contact strategy was used, indirect contact, where community members received movie-based or paper-based testimonies or fictional stories, was most employed (n = 2, 50% vs n = 8, 57%), followed by direct contact, a short term form of connection between the general community and representation of people with lived experience (n = 1, 25% vs n = 7, 50%). A third form of social contact is shaped by direct cooperation, where people with lived experience and members from the general community were facilitated to collaborate in a longer-term trajectory. This was used in relatively few social contact interventions (n = 1, 25% vs n = 3, 21%).

Organisational training programmes, implemented in 24 interventions, were also education-based. Only one training programme, one-way and interactive in its knowledge transfer, was child-focused. In adult-focused interventions, one-way education sub-strategies (n = 16, 70%) and interactive forms or learning (n = 14, 61%) were both commonly used. One training programme made use of popular opinion leaders to disseminate information.

3.4.3. Division at socio-ecological levels

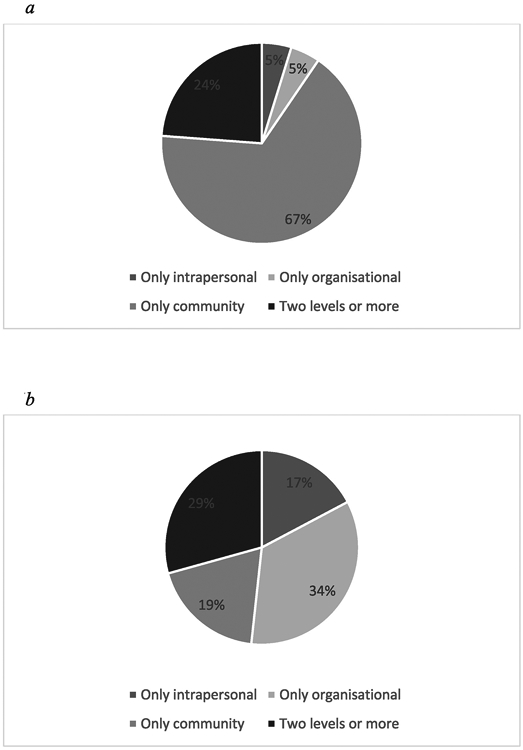

The framework used (Heijnders and VanderMeij, 2006) allocated strategies to specific socio-ecological levels, being intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational, community or institutional/governmental, based on their activities and the groups involved. No interventions at the governmental/institutional level were reported. Almost three quarter of the interventions (n = 16, 76% vs n = 41, 71%) was implemented at one socio-ecological level; only community (n = 14, 88% vs n = 11, 27%), organisational (n = 1, 6% vs n = 20, 49%) or intrapersonal level (n = 1, 6% vs n = 10, 24%). See Fig. 5a and b. Interventions implemented across two or more socio-ecological levels (n = 5, 24% vs n = 17, 29%) most commonly combined strategies at the intrapersonal (n = 5, 100% vs n = 14, 82%), community (n = 4, 80% vs n = 11, 65%) and interpersonal level (n = 1, 20% vs n = 7, 41%). Organisational strategies were only implemented at two levels in adult-focused interventions (n = 8, 47%). The distribution of strategies used in child-focused interventions differed significantly from adult-focused intervention based on the socio-ecological level that is represented, χ (3) = 18.1, p < 0.01, attributed foremost to higher degree of strategies at the community level among child-focused interventions (see Figs. 5a and b).

Fig. 5.

. a Socio-ecological levels employed in child-focused stigma reduction interventions in LMIC. b Socio-ecological levels employed in adult-focused stigma reduction interventions in LMIC.

3.5. Evaluations

More than half of the included papers were evaluation studies (n = 6, 43% vs n = 25, 53%), using an experimental (n = 2, 33% vs n = 5, 20%) or quasi-experimental (n = 4, 67% vs n = 20, 80%) study design. HIV/AIDS stigma was addressed most often in the evaluation studies (n = 4, 67% vs n = 11, 44%); in addition, the studies focused on stigma of mental illness (n = 1, 17% and n = 7, 28%) and leprosy (n = 1, 17% and n = 5, 20%). Two other studies, only adult-focused interventions, addressed TB-stigma (n = 1, 4%), and the intersection of mental illness (substance abuse) and HIV/AIDS (n = 1, 4%).

The 31 evaluation studies described in total 49 interventions (n = 13, 27% vs n = 36, 73%). Child-focused interventions were most commonly implemented within the context of a school (n = 9, 69% vs n = 5, 14%), while adult-focused interventions were mostly conducted at a community site (n = 4, 31% vs n = 21, 58%) or in a health centre/hospital (0% vs n = 17, 47%). Implementation at a family location was limited (n = 1, 8% vs n = 3, 8%) and always in combination with another site. The majority of interventions were implemented at one location (n = 12, 92% vs n = 27, 75%). In evaluation studies where the delivery channel was reported (n = 11, 85% vs n = 35, 97%), the channel most used to reach children was printed or movie-based material (n = 5, 55% vs n = 8, 23%) followed by mass media (n = 3, 27% vs n = 1, 3%), while the adult-focused evaluation interventions were mainly implemented by professionals (0% vs n = 20, 36%), lay community workers (n = 1, 9% vs n = 12, 34%) and people with lived experience (n = 1, 9% vs n = 10, 29%). The majority of the child-focused interventions (n = 9, 82%) used one channel of implementation, while half of the interventions focusing on adults used two or more channels (n = 18, 51%). Contact hours actively spent by participants in the intervention lasted without exception less than a week (both 100%) when reported or calculable (n = 12, 92% vs n = 15, 58%).

In total, the evaluated interventions consisted of 89 strategies (n = 17, 19% vs n = 72, 81%), and all before-mentioned strategies except advocacy were implemented in these interventions; though not evenly shared between child- and adult-focused interventions. Community education was the strategy most implemented in child-focused interventions (n = 11, 65%) and employed regularly in adult-focused interventions (n = 10, 14%) in foremost inter-active form (n = 7, 64% vs n = 8, 80%). Contact at community level (n = 2, 12% vs n = 9, 13%), when conducted, was most often done complementary to community education programmes (n = 2, 100% vs n = 7, 78%). Other strategies used in child-focused interventions were counselling (n = 1, 6% vs n = 6, 8%), group counselling (n = 1, 6% vs n = 4, 6%), care and support (n = 1, 6% vs n = 1, 1%), and social consensus (n = 1, 6% vs 0%). Important strategies only employed in adult-focused interventions were organisational training programmes (0% vs n = 16, 22%), inter-active (n = 10, 63%) and/or one-way (n = 9, 56%) and empowerment (0% vs n = 9, 13%). Strategies implemented to a lesser extent in adult interventions were patient-centred policies (0% vs n = 5, 7%), self-help groups (0% vs n = 3, 4%) and home care teams and community-based rehabilitation (both n = 2, 3%). Of the evaluated interventions, the majority (n = 12, 92% vs n = 26, 72%) was implemented at one socio-ecological level, divided over community (n = 12, 100% vs n = 5, 19%), organisational (0% vs n = 14, 54%) and intrapersonal (0% vs n = 7, 27%) level. All but two multi-level interventions (n = 1, 100% vs n = 8, 80%) were implemented at intra-personal level, either in combination with interpersonal (n = 1, 100% vs n = 3, 38%), organisational (0% vs n = 2, 25%) and/or community level (0% vs n = 6, 75%).

The majority of the strategies reported positive outcomes on stigma reduction, with all child-focused interventions having positive results (n = 13). Of the adult-focused interventions, 86% (n = 31) reported positive outcomes. Some of the strategies employed in the adult-focused interventions (n = 13) were reported to have had no effect, namely community education (n = 4), contact in the community (n = 3), individual counselling (n = 2), group counselling (n = 2), home care teams (n = 1) or training programmes (n = 1). In comparison to how often these strategies were employed, home care teams and group counselling had on overall no effect (100%), followed by individual counselling with 50% of the time no effect, community education (33%) and social contact in the community (27%), training programmes had no effect 8% of the time (See Fig. 6 for more details).

Fig. 6.

Evaluation outcomes of stigma reduction interventions in LMIC, divided in child-focused and adult-focused interventions.

The stigma scales used in these interventions were heterogeneous. One child-focused study used the Bogardus Social Distance Scale (SDS) (Yan et al., 2018), and three adult-focused studies used the SDS as well, while another study used questions based on SDS. The SARI Stigma Scale (SSS) was used by one child-focused and one adult-focused study, both together with the Participation Scale. The Participation Scale was also used by another adult-focused intervention. The Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness (CAMI) was used twice, for adults only, as was the Explanatory Model Interview Catalogue (EMIC). The Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale was used once, for adults, however, internalised stigma was also measured through other means, such as the Serithi Scale and the Rosenberg Scale, as a determinant of internalised stigma, or other, unnamed, scales. Stigma was further measured, both for children and adults, through adapted scales focusing on enacted stigma, blame, disclosure, courtesy, intent to discriminate and attitudes, fear and coercive measures. One scale used with children specifically focused on stigma through characteristics, affective reaction, severity and blameworthiness.

4. Discussion

This systematic literature review showed that, within the overall dearth of evidence in stigma reduction interventions in LMIC, a minority of studies evaluate interventions for children and adolescents. Within these studies, the minority was specifically addressing children only. In the child – adult mixed interventions, children often received the same intervention as the adults. As the stigma context both resembles that of adults as they live in the same environment, but differs at the same time due to being a child (Mukolo et al., 2010), a stigma reduction intervention should take this different context into account.

When comparing child-focused interventions versus those only targeting adults, the review demonstrated that for both groups education-based stigma reduction strategies were most commonly used. Child-focused interventions differed significantly from adult-focused ones in that they were shorter and more often community-based, foremost through school-based educational interventions, accompanied by a contact strategy in less than 25% of the interventions. Half of the contact strategies used in education-based child-focused interventions were face-to-face. For adults, a variety of education-based strategies such as educational empowerment, training programmes or community-based education strategies were employed across socio-ecological levels, with almost 50% accompanied by contact strategies. These two strategies – education-based and contact – have been identified to be the currently most promising approaches (Birbeck, 2006; Cross, 2006) to tackle public stigma, emphasising the importance of information for youth, with positive results augmented if the intervention included a face-to-face contact strategy (Corrigan et al., 2012; Corrigan et al., 2015). Action-oriented was the most targeted stigma type in child- and adult-focused interventions, though the distribution differed between these age groups. Where public stigma, provider-based stigma and self-stigma were evenly distributed in adult-focused interventions, the emphasis in child-focused interventions was on public stigma. The review showed that 86% of the adult-focused strategies reported positive outcomes, and all child-focused interventions including education-based interventions reported positive results. Though the results demonstrated that some scales are used more often, such as SSS, EMIC, SDS, Participation Scale and CAMI, they were mostly used in adult-focused interventions. SDS, Participation Scale and SSS were also used once in child-focused interventions. The variety in scales, next to the limited number of randomised designs, merit caution of conclusions.

Implementation factors are crucial to ensure that potentially effective interventions can be replicated or scaled. This review demonstrated that most interventions lasted less than a week in duration, with child-focused interventions being generally shorter than adult-focused interventions. This may however come at a price: conclusions drawn in an earlier review (Clement et al., 2013) suggest that the most effective interventions are those that are more intensive. Another implementation factor is how or by whom an intervention is implemented. A closer look at the delivery channels in this review indicated that, in reported examples, professionals constituted nearly half of the implementation force. This is disproportionately skewed for adult-focused interventions, however professional staff also implemented 25% of the child-focused interventions, as research staff itself. In under-resourced contexts such as LMIC, where professionals might be scarce or overburdened, for reach as well as sustainability stigma reduction interventions may stand to learn from task-shifting and task-sharing experiences as spearheaded by the mental health field (Fulton et al., 2011; Hoeft et al., 2018). Implementation can also be facilitated by channels easier to replicate and implement, such as printed, movie-based or web-based materials, which this review showed were the most popular delivery channels for child-focused interventions. Replication is an issue in itself; 59 of the included interventions were unique interventions, while two were replications. To further understand the value of a promising intervention, replication is a necessity.

Because stigmatisation is a societal process engrained within the community at individual, interpersonal, organisational, social and institutional level, researchers have long recognised the importance addressing stigma at multiple socio-ecological levels (Rao et al., 2019). The strategies identified within this review, following an existing socio-ecological strategy analysis framework (Heijnders and VanderMeij, 2006), demonstrated that the majority of the interventions was implemented at one socio-ecological level, with very little difference between child- and adult-focused interventions. This finding echoes a recent review stating that single-level interventions are more common (Rao et al., 2019), with the realisation that stigma reduction at multiple levels can improve the outcome (Richman and Hatzenbuehler, 2014; Rao et al., 2019). Parallel to this finding, and recognising stigmatisation as a dynamic social process, we further argue that stigma reduction interventions should anticipate potential positive or negative effects in the wider community. Therefore anticipated effects of the stigma reduction interventions should be assessed among groups beyond the intervention target groups, such as children and adolescents when the intervention might impact them through interaction with the direct target groups, such as service providers.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This review synthesises studies identified through a search of eight databases and through cross-referencing previous reviews; showcasing and comparing strategies used in stigma reduction interventions regardless of stigmatised labels, target group or study design. This is done in a sector and context where information is scarce. For reasons of feasibility, eligible studies had to have the word ‘stigma’ as part of the title. Therefore, potential studies that described intervention studies reducing stigma, but not specifically labelled it as such have not been identified. Furthermore, as the review focused on interventions with a primary focus on stigma reduction, interventions where stigma reduction was a secondary focus were not included. Search terms for setting were based on the World Bank list of 2017, potentially resulting in not identifying studies done in countries that were LMIC earlier, but HIC in 2017. Additionally, we did not approach authors of included studies to share other studies done by them or familiar to them, potentially limiting eligible studies. Another limitation is that intervention data and additional information was extracted from the identified publications as opposed to collecting data from underlying intervention manuals containing further details on strategy. Finally, the quality of the evaluation studies was not examined beyond listing the study designs, so no definitive conclusions can be drawn on the effectiveness of any of the strategies employed.

5. Conclusion

This review synthesised and compared stigma reduction interventions across stigmatised groups in LMIC, specifically highlighting stigma reduction interventions that targeted children and adolescents. We conclude that children remain an under-addressed target group in stigma reduction interventions while their specific situation merits more attention. Positive outcomes were reported on all child-focused interventions and promising interventions were identified, with school-based education-based strategies as the most employed for children and adolescents. As in adult-focused interventions, HIV/AIDS and mental illness were the main stigmas addressed. To advance work in stigma reduction in LMIC, we urge for more evidence-based stigma reduction interventions, consisting of strategies at multiple socio-ecological levels. We recommend that interventions directly target children and adolescents in combination with adults, as well as see children and adolescents as an indirect target group, acknowledging that interventions could impact beyond the direct target group. As current work largely addresses and generates knowledge on strategies to reduce HIV/AIDS and mental illness stigma, and to a limited extent leprosy stigma, we recommend to not only increase efforts in tackling HIV/AIDS, mental health and leprosy stigma, but to go beyond to other characteristics that are subject to stigma, also from an intersectionality perspective. Promising strategies from existing stigma reduction interventions, with stigma drivers and strategies being recognised as globally comparable, can be taken as a starting point, informed by contextual assessments as part of the intervention. Researchers are urged to conduct replication studies of promising interventions.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

There is paucity in stigma reduction strategies for children in LMIC.

Community strategies are significantly more applied for children than for adults.

Intervention duration is significantly shorter for children than for adults.

Stigma reduction interventions should target children both directly and indirectly.

Interventions should address stigma beyond the scope of HIV/AIDS and mental health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Katja Schlegel, Lecturer at the University of Bern, for her support in the inclusion review of Russian articles. We thank Dr. Gabriela Koppenol-Gonzalez, Senior Researcher at War Child Holland, for her help with conducting the chi-square tests.

BAK is supported by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH104310, R21MH111280). KH, AK and MJ are supported by War Child. GT is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King’s College London NHS Foundation Trust, and the NIHR Asset Global Health Unit award The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. GT receives support from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MH100470 (Cobalt study). GT is supported by the UK Medical Research Council in relation the Emilia (MR/S001255/1) and Indigo Partnership (MR/R023697/1) award.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- Ahuja, Dhillon, Juneja, Sharma, 2017. Breaking barriers: an education and contact intervention to reduce mental illness stigma among Indian college students. Psychosoc. Interv 26 (2), 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu, Ahmed, 2008. Effectiveness of IEC interventions in reducing HIV/AIDS related stigma among high school adolescents in Hawassa, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev 22 (3), 232–242. [Google Scholar]

- Altindag, Yanik, Ucok, Alptekin, Ozkan, 2006. Effects of an antistigma program on medical students’ attitudes towards people with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 60 (3), 283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apinundecha, Laohasiriwong, Cameron Lim, 2007. A community participation intervention to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma, Nakhon Ratchasima province, northeast Thailand. AIDS Care 19 (9), 1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arole, Premkumar, Arole, Maury, Saunderson, 2002. Social stigma: a comparative qualitative study of integrated and vertical care approaches to leprosy. (Special issue: integration of leprosy services). Lepr. Rev 73 (2), 186–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, Longmore, Ebenezer, Richard, 2012. Effectiveness of social skills training for reduction of self-perceived stigma in leprosy patients in rural India–a preliminary study. Lepr. Rev 83 (1), 80–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]