Abstract

We identified apolipoprotein E (ApoE) as one of the proteins that are found in complex with complement component C4d in pooled synovial fluid of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients. Immobilized human ApoE activated both the classical and the alternative complement pathways. In contrast, ApoE in solution demonstrated an isoform-dependent inhibition of hemolysis and complement deposition at the level of sC5b-9. Using electron microscopy imaging, we confirmed that ApoE interacts differently with C1q depending on its context; surface-bound ApoE predominantly bound C1q globular heads, whereas ApoE in solution favored the hinge/stalk region of C1q. As a model for the lipidated state of ApoE in lipoprotein particles, we incorporated ApoE into PC/PE liposomes and found that the presence of ApoE on liposomes increased deposition of C1q and C4b from serum when analyzed using flow cytometry. In addition, post-translational modifications associated with RA, such as citrullination and oxidation, reduced C4b deposition, whereas carbamylation enhanced C4b deposition on immobilized ApoE. Post-translational modification of ApoE did not alter C1q interaction but affected binding of complement inhibitors Factor H and C4b-binding protein. This suggests that changed ability of C4b to deposit on modified ApoE may play an important role. Our data show that post-translational modifications of ApoE alter its interactions with complement. Moreover, ApoE may play different roles in the body depending on its solubility, and in diseased states such as RA, deposited ApoE may induce local complement activation rather than exert its typical role of inhibition.

Keywords: Apolipoprotein, ApoE, complement system, human, rheumatoid arthritis, synovial fluid

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that mainly affects the joints. Age, gender, lifestyle, environmental factors, genetic background, infections (1), and the oral, lung-, and intestinal microbiome (2) are all thought to play a role in the onset of RA. In the spectrum of ongoing inflammation, an important part of the innate immune system that is chronically activated in RA is the complement system. The three arms of this system, i.e. the classical, lectin, and alternative pathways are all activated in RA. Although systemic and local evidence of complement activation are well established (3–8), and several mechanisms of complement activation in RA are well documented (i.e. via immune complexes and damaged tissue (9–11)), identification of novel complement activators might provide new ways to approach diagnostics or new lines of therapy via emerging complement inhibitors. Among the targets that we have previously identified as covalently bound by C4d in synovial fluid (SF) of RA patients (12) is apolipoprotein (Apo) E, which indicates that it may be an activator of the classical pathway. ApoE is a multifunctional protein, which has long been recognized for its role in lipid transport (13). Over recent years it was discovered that it also affects major aspects of the immune system, such as antigen- and mitogen-induced T cell activation, defense against certain viral infections, and defense against infectious bacteria such as Listeria monocytogenes and Klebsiella pneumoniae (14, 15).

Many RA patients produce autoantibodies directed at post-translationally modified proteins. One type of these modifications is citrullination, the modification of peptidylarginine to citrulline. Citrullination occurs under physiological conditions but insufficient regulation can induce the formation of neo-epitopes that may promote autoimmune reactions to modified antigens (16), and possibly also to the native protein (17). Notably, ApoE (18) as well as other apolipoproteins (19) have previously been identified as part of the ‘citrullinome’ in RA patient SF.

Antibodies against carbamylated proteins have also been identified in RA patients (20). Carbamylation is a non-enzymatic reaction of amino groups on proteins with isocyanic acid, which can lead to the formation of ε-carbamyl-lysine (also called homo-citrulline) when lysines are the affected residues (21). Neutrophil-derived myeloperoxidase catalyzes the oxidation of thiocyanate in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (21). This occurs at sites of inflammation and atherosclerotic plaques, where thiocyanate is abundant in blood (22). The peroxidase activity may also cause oxidation as a third possible protein modification that could affect morphology, charge, and functionality of a protein.

We hypothesized that native ApoE might be one of the activators of complement in the SF of RA patients. We confirmed that immobilized ApoE activates both the classical and the alternative complement pathways in vitro, but that the interactions of ApoE with the complement system in solution strongly differ from the immobilized form. We found that post-translational modifications can play a role in RA by altering interactions of ApoE with complement and certain complement inhibitors, and inhibition of these post-translational processes may prove useful for future therapeutic strategies.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement, description of patients and controls, and sample handling –

The collection of SF was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. SF was obtained from RA patients, fulfilling the American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA and seeking care at the Department of Rheumatology at Lund University hospital due to a knee joint synovitis that required a therapeutic joint aspiration. Immediately after collection of synovial fluid by aspiration, samples were centrifuged and supernatant was frozen at −80°C for storage. Freeze thaw cycles were kept to a minimum by aliquoting smaller volumes for transport and individual assays, and by thawing and using single aliquots only once.

Affinity chromatography to capture complement component C4d and C3b in complex with their activating targets from synovial fluid of RA patients –

Capture of protein complexes resulting from complement activation in pooled SF was performed as described previously (12), with minor adaptations; here we also used a monoclonal mouse anti-human antibody (IgG1) that recognizes C3b but not C3, so specific for only activated C3 (23). As control, SF was run on a column with corresponding control IgG, i.e. mouse isotype IgG1 (ImmunoTools). Samples were then prepared for analysis by mass spectrometry (MS), performed as described previously (12). All spectra assigned to Apolipoproteins were manually inspected and validated.

Complement deposition-, and binding assays –

Deposition assays with pooled normal human serum and complement binding assays were performed as described previously (12) with minor adaptations. Purified human recombinant ApoE (Novoprotein Apo ε3, and BioPure, Biovision Apo ε2, ε3, and ε4), ApoB (Athens research and technology), and ApoD (Novoprotein) were coated at 10 μg/mL in PBS. For C1q deposition from serum, heat aggregated IgG was coated as a positive control at 1.0 μg/mL because of its relatively strong signal, and for components C4b, C3b, and C9, heat aggregated IgG was coated at 2.5 μg/mL, unless otherwise specified in the graph. C1q was purified from plasma as described (24). For FH binding, ApoE was coated at 1 μg/mL in CBB buffer consisting of 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 (25), blocking was performed in 5% BSA (Fraction V, AppliChem, Saveen and Werner AB) in CBB, and FH binding was performed in CBB. FH and C4BP were expressed and purified as described previously (26, 27). FB depleted serum and FB were purchased from Quidel (Triolab AB) and CompTech, respectively. Colorimetric assays developed with ortho-phenylenediamine tablets (Kem-En-Tec) were spectrophotometrically analyzed at 490 nm, and assays where tetramethylbenzidine solution (Sigma-Aldrich) was used were analyzed at 450 nm as recommended by the manufacturers.

Electron microscopy –

The structure of C1q-ApoE complexes was analyzed by negative staining and electron microscopy as described previously (28). ApoE and C1q were diluted at 10 μg/mL in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. Aliquots of 5 μL were adsorbed to carbon-coated grids for 1 min, then washed with two drops of water, and then stained with two drops of uranyl formate. Glow discharge at low pressure in air was used to render the grids hydrophylic. In some experiments, ApoE was identified by labeling with colloidal thiocyanate gold (29). The grids were analyzed using a Jeol JEM 1230 electron microscope operated at a 60kV accelerating voltage. Images were recorded with a Gatan Multiscan 791 Charge-Coupled Device camera. The experiments were carried out for recombinant Apo-ε3 from Novoprotein and from recombinant ApoE3 from AH Diagnostics Ab (BioPure, Biovision).

Expression and purification of recombinant human peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 enzyme –

Full length human PAD4 with an N-terminal GST-tag was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. GST-PAD4 expression was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside, cells were harvested, and lysate was loaded onto Glutathione Sepharose B resin (GE Healthcare, Life Science). Eluted protein fractions containing PAD4-GST were pooled and dialyzed against buffer for ion exchange chromatography. After purification, eluted protein fractions were concentrated and PAD4 activity was determined on N-α-benzoyl-L-arginine ethyl ester hydrochloride substrate with a colorimetric assay (30).

Post-translational protein modifications –

Oxidation was induced by incubating protein-coated microtiter plates with 2 μg/mL of myeloperoxidase (Sigma-Aldrich) and 50 mM H2O2 (Merck) in PBS (Medicago) for 2h at 37°C. Citrullination was induced by incubating protein-coated microtiter plates with 500 mU/mL human recombinant PAD4 enzyme, in the presence of reducing agent (10 mM dithiothreitol from Fermentas, Thermo Fischer Scientific) in 10 mM Tris buffer (Saveen and Werner AB) with 10 mM CaCl2 (Merck, pH 7.4), for 2h at 37°C. Carbamylation was induced by incubating protein-coated microtiter plates with 0.1 M KCNO (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 4 or 6 h at 37°C.

Assays for assessing complement inhibitory properties –

For C1 complex binding, purified human recombinant ApoE (Novoprotein, 10 μg/mL), heat aggregated human IgG (Baxter Medical AB, 1 μg/mL), and A1AT (C.B. Laurell, 10 μg/mL) were coated on Maxisorp microtiter plates and binding was analyzed using purified C1 (CompTech), as described previously (12). C4b and sC5b-9 inhibition assays and hemolytic assays were performed as described previously (31, 32), with ApoE concentrations of 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL. ApoE isoforms ε2, ε3, and ε4 were purchased from AH Diagnostics Ab (BioPure, Biovision) and plasma-derived ApoE was purchased from Athens Research and Technology. Proline And Arginine Rich End Leucine Rich Repeat Protein was purified from bovine cartilage according to previously published methods (33).

Preparation of liposomes –

Liposomes were prepared as described (34, 35) with minor adaptations. All lipids were from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Sigma-Aldrich). A 1:9 v/v mixture of methanol:chloroform was used as lipid solvent. Egg phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine were used as main constituents in a 1:9 ratio, and a small amount of cholesterol was added into the lipid mixture. After drying the lipid cake, it was resuspended in 25 mM HEPES buffer with 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.7), solubilized by adding n-octyl-beta-D-glucopyranoside to a concentration of 200 mM (Sigma-Aldrich), and sonicated for 3 cycles of 150 s. ApoE was incorporated at a concentration of 6 μg/mL, and liposomes were dialyzed overnight against 25 mM HEPES buffer with 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.7), and then coupled to M-280 streptavidin Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Fischer Scientific) using Biotin-conjugated egg PC. Bodipy-conjugated egg PE was incorporated to visualize the liposomes with a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). ApoE on liposome-coated Dynabeads was detected using mouse anti-human ApoE monoclonal antibody (Novus Biologicals), and complement deposition on liposomes was assayed as described previously for deposition on bacteria (36).

C4d and ApoE ELISAs of SF of 30 RA patients –

ELISA to measure C4d in 5% SF of RA patients was performed as previously described for pooled serum (37) with minor adaptations, instead of ortho-phenylenediamine tablets the assay was performed using tetramethylbenzidine solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and colorimetric development was measured at 450 nm. Human ApoE ELISA kit (#ab233623, Abcam) was used following the manufacturer’s instructions with minor adaptations. Dilutions of SF (1:32000) were used and were kept on ice until shortly before the assay to prevent decay.

Results

Apolipoproteins are opsonized with complement components C4d and C3b in pooled synovial fluid of RA patients

MS was used to analyze the content of eluted fractions of C4d-complexes from pooled SF obtained using an anti-neoC4d-coupled affinity column, and eluted fractions of C3b-complexes from pooled SF run on an anti-neoC3b-coupled affinity column plus the eluates of pooled SF run on the corresponding control columns. In both lists resulting from the MS analyses, apolipoproteins were represented, and the apolipoproteins that were only eluted from the target columns but not from the control columns are listed in Table I. From the C4d column, ApoE, ApoB, and ApoD were detected in the eluate, and from the C3b column, ApoL1 and Apo(a) were detected. As some apolipoproteins are implicated in other age-related diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (38) and age-related macular degeneration (39), that also involve complement activation (40, 41), we proceeded to confirm complement deposition and binding to apolipoproteins that were coated on microtiter plates.

Table I.

Mass spectrometry list of Apolipoproteins eluted from anti-C4d-, and anti-C3b coupled affinity columnsa

| Accession number | Protein Name | Mass kDa | Score | Significant Matches | Unique Peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein targets from neoC4d column: | |||||

| P02649 | Apolipoprotein E | 36,154 | 164 | 5 | 4 |

| P04114 | Apolipoprotein B-100 | 515,605 | 48 | 2 | 6 |

| P05090 | Apolipoprotein D | 21,276 | 102 | 4 | 3 |

| Apolipoprotein targets from neoC3b column: | |||||

| O14791 | Apolipoprotein L1 | 43,974 | 86 | 2 | 2 |

| P08519 | Apolipoprotein(a) | 501,319 | 51 | 2 | 2 |

List of eluted Apolipoproteins in eluate of anti-neoC4d and anti-neoC3b columns, that were absent in control column eluates. Score values are listed as highest seen and accession number refers to the accession number of the protein in the UniProt database.

ApoE activates the classical and the alternative complement pathways

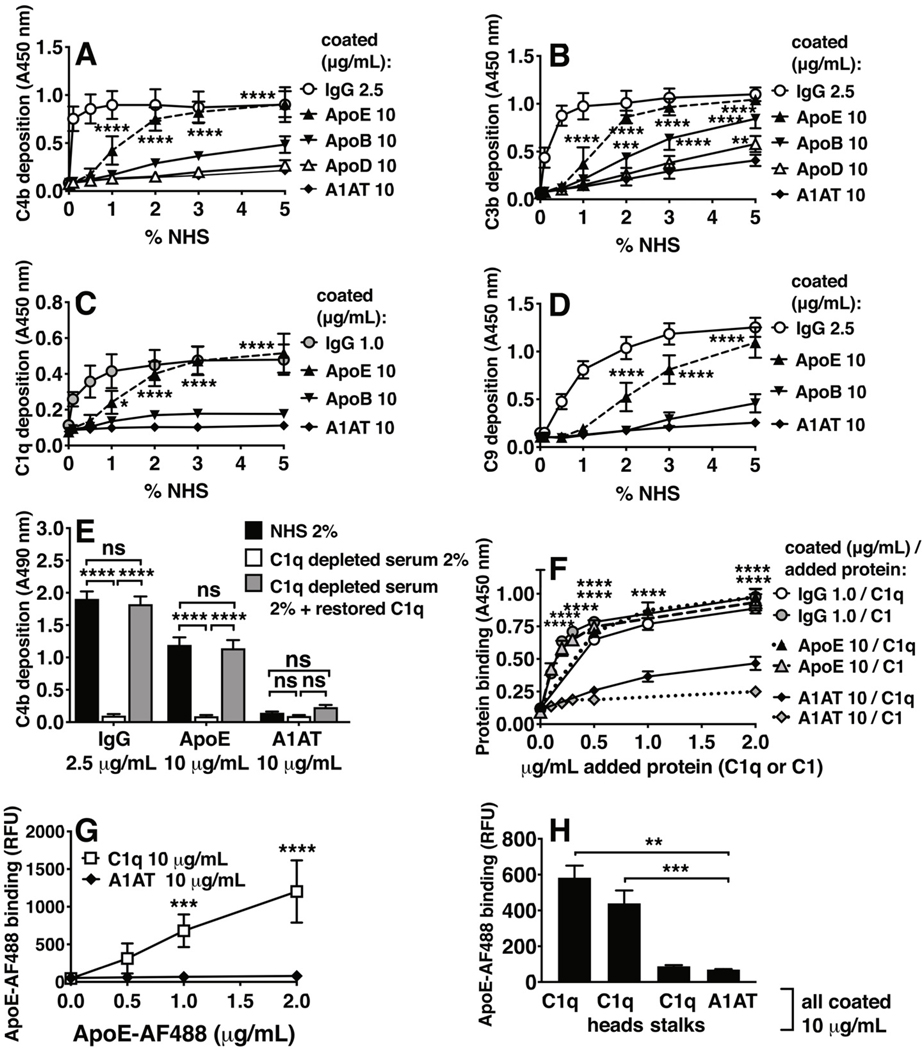

ApoD did not activate C4b or C3b and was not tested further for C1q or C9 (Fig. 1A, 1B). ApoB did not induce deposition of the complement components C4b, C9, and C1q (Fig. 1A–1D) but it triggered some C3b deposition. ApoE, however, induced deposition of all four tested complement components, C4b, C3b, C1q, and C9 (Fig. 1A–1D) and was therefore selected for detailed studies. ApoE-mediated activation was induced via the classical pathway, as serum C1q depletion caused substantial loss of activation, and replenishing C1q almost fully rescued the signal as measured by C4b deposition (Fig. 1E). Direct binding of C1q and C1 to coated ApoE protein, and binding of ApoE to coated C1q protein was observed (Fig. 1F, 1G). In addition, ApoE bound predominantly to coated C1q head groups but no significant binding to coated C1q stalks was observed (Fig. 1H).

Figure 1. Complement deposition and binding to apolipoproteins.

Complement deposition on apolipoproteins was assayed using NHS and C1q-depleted human serum (ΔC1q). (A-D) C4b-, C3b-, C1q-, and C9 deposition from NHS, respectively using classical complement deposition conditions (DGVB++ buffer), on coated proteins h.a. IgG (2.5 μg/mL in A, B, D; 1 μg/mL in C), ApoE (10 μg/mL), and negative control A1AT (10 μg/mL). (E) C4b deposition from 2% NHS, 2% ΔC1q, and 2% C1q-reconstituted serum (ΔC1q + C1q, 3.2 μg/ml, based on 160 μg/ml in 100% serum), on coated proteins h.a. IgG (1.0 μg/mL), ApoE (10 μg/mL), and A1AT (10 μg/mL). (F) C1q and C1 binding to immobilized ApoE (10 μg/mL), h.a. IgG (0.5 μg/mL), and A1AT (10 μg/mL), detected using specific antibodies. (G) Fluorescently labeled ApoE (AF488) binding to immobilized C1q (10 μg/mL), and A1AT (10 μg/mL). (H) Fluorescently labeled ApoE (AF488) binding to full C1q protein, and isolated head-, and stalk domains of C1q (all 10 μg/mL). Mean ± SD (A-D, F, G) or mean + SD (E and H) of three individual experiments are shown. Samples per experiment were analyzed in duplicate and two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test (A-D, F), two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test (E), two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparisons test (G), and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test (H) were applied to determine statistically significant differences compared to control (A1AT), and per coated protein to compare C4b deposition from NHS, C1q-deficient serum, and C1q-replenished serum (E). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. NHS, normal human serum; h.a. IgG, heat-aggregated IgG; ApoE, recombinant human Apolipoprotein E (ε3 isoform from Novoprotein, AF488-labeled protein in G, 2 μg/mL in H); ApoB, Apolipoprotein B; ApoD, apolipoprotein D; A1AT, alpha-1-antitrypsin; RFU, relative fluorescence units.

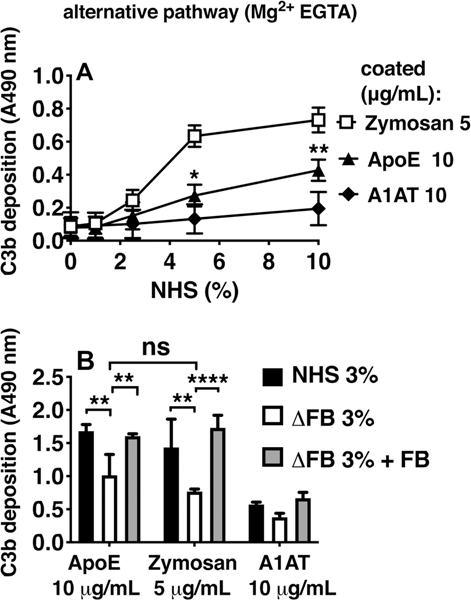

Using Mg2+-EGTA buffer that only allows complement activation via the alternative pathway, ApoE was shown to activate this pathway as well, as measured by C3b deposition (Fig. 2). As expected, the classical pathway assay was more sensitive, detecting robust activation by the positive control below 2% serum, whereas activation of alternative pathway required higher amounts of serum as is well established for other activators of this pathway. C3b deposition was decreased to the same level as that of the positive control, Zymosan, when using FB-depleted serum. Reconstituting FB rescued the signal, indicating that the alternative pathway is also activated by ApoE. The lectin pathway was not activated by ApoE (data not shown).

Figure 2. ApoE activates the alternative complement pathway.

Complement deposition on ApoE was assayed using NHS or Factor B (FB)-depleted serum (ΔFB). (A) C3b deposition using alternative complement deposition conditions (Mg2+-EGTA buffer). (B) C3b deposition from 3% sera: NHS, ΔFB, and FB-reconstituted serum (ΔFB + 6 μg/mL FB, based on 200 μg/mL in 100% serum). Mean ± SD (A) or mean + SD (B) of three individual experiments are shown. Samples per experiment were analyzed in duplicate and two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s (A) or Dunnett’s (B) multiple-comparisons test were applied to determine statistically significant differences. **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001. NHS, normal human serum; Zymosan (5 μg/mL); ApoE, recombinant human apolipoprotein E (ε3 isoform from Novoprotein, 10 and 3 μg/mL in A and B resp.); A1AT, alpha-1-antitrypsin (10 μg/mL).

Interactions of ApoE with the complement system are context-dependent

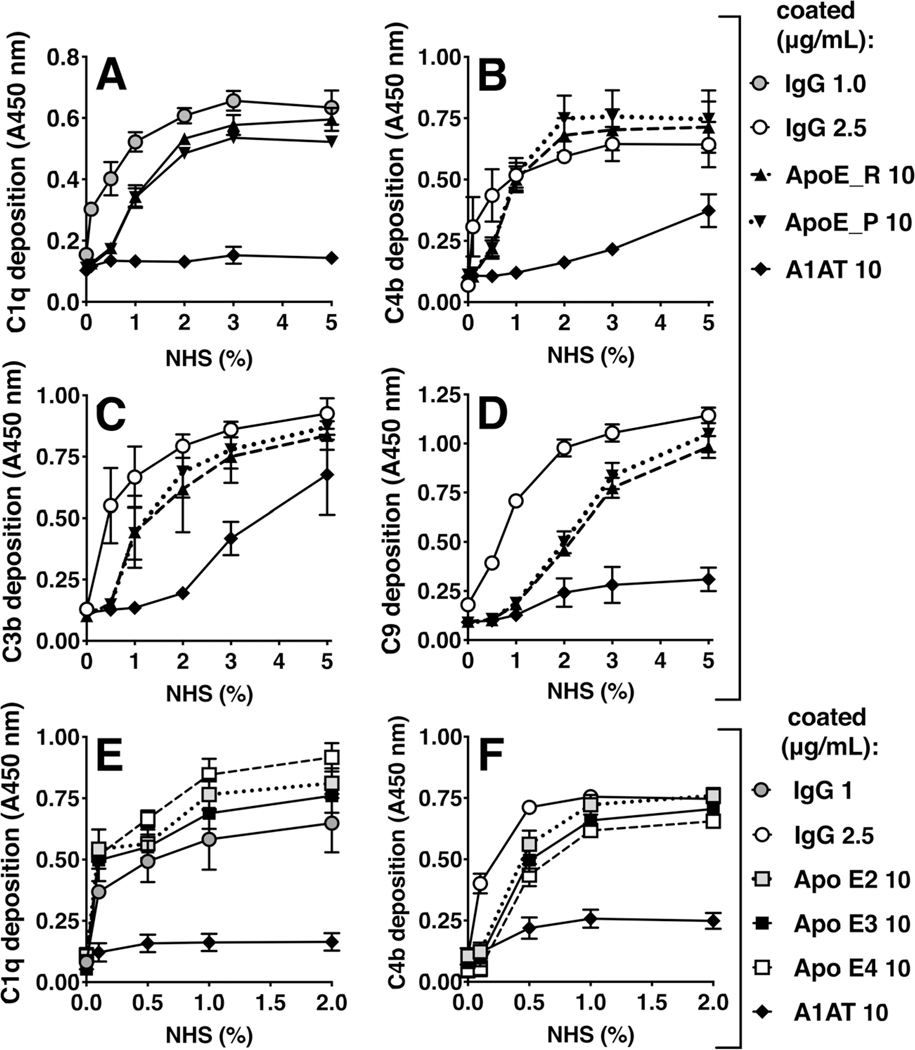

As ApoE isoform is not considered to be a risk factor that affects joint inflammation in RA (42), initial experiments were performed with recombinant human ApoE of the ε3-isoform, which is the most common. This was consistent with a lack of difference in inducing complement activation in follow up experiments, as ApoE-mediated complement activation on immobilized ApoE was not significantly different between recombinantly expressed (ApoE_R) vs. plasma derived ApoE (ApoE_P; Fig. 3A–3D), nor between the different isoforms (Fig. 3E, 3F). In healthy individuals, ApoE is thought to play anti-inflammatory roles (15), and another group recently reported inhibitory properties of ApoE on complement activation (43), so we also explored the possible role of ApoE as an inhibitor of complement activation. First, we tested whether the C1 protein complex would bind to immobilized ApoE, as classical complement pathway inhibitors that bind C1q stalks are unlikely to bind strongly to the full C1 complex (44, 45). As already shown in Fig. 1F, C1 complex bound to coated recombinant ApoE (ε3). Next, we investigated whether preincubating serum with ApoE, inhibited C4b-, or sC5b-9 deposition on a coated positive control, i.e. heat aggregated IgG. At the level of C4b, no inhibition of complement was observed for recombinant ApoE in the tested concentrations, and only moderate inhibition for plasma derived ApoE (Fig. 4A). However, for sC5b-9 in the plate assay, and for the Membrane Attack Complex using hemolytic assays, we observed inhibitory effects for all tested types of ApoE (Fig. 4B, 4C). Using recombinantly expressed (human) isoforms ApoE-ε2, ApoE-ε3, ApoE-ε4, and also testing plasma isolated vs. recombinant ApoE-ε3, we observed that all ApoE types induced a dose-dependent inhibition of sC5b-9 deposition and sheep red blood cell lysis. At the level of sC5b-9, inhibition strength of ApoE-ε3 > ApoE-ε2 > ApoE-ε4. Recombinant ApoE-ε3 and ApoE-ε4 showed similar inhibition of hemolysis to plasma-derived ApoE, and recombinant ApoE-ε2 induced a slightly stronger inhibition compared to ApoE-ε3 and -ε4. Hemolysis inhibition by Apo-ε3 from BioPure was stronger than that induced by Apo-ε3 from Novoprotein, which may in part be due to different activity relating to protein formulation and stability that varies between different manufacturers.

Figure 3. Complement deposition and C1 binding on different types of immobilized ApoE.

Complement deposition on ApoE was assayed using NHS. (A-D) C1q-, C4b-, C3b-, and C9 deposition using classical complement deposition conditions (DGVB++ buffer) on immobilized recombinant ApoE and plasma derived ApoE. (E, F) C1q and C4b deposition on different immobilized ApoE isoforms. Positive control h.a. IgG was coated at 1 μg/mL in A and E, and 2.5 μg/mL in B, C, D, and F; ApoE was coated at 10 μg/mL, and A1AT at 10 μg/mL. For each panel, mean ± SD of three individual experiments are shown. Samples per experiment were analyzed in duplicate and two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test was applied to determine statistically significant differences between plasma-derived and recombinant ApoE or between ApoE isoforms. No statistically significant differences were found for all panels. NHS, normal human serum; IgG, heat-aggregated IgG; ApoE_R, recombinant human Apolipoprotein E of the ε3 isoform from Novoprotein; ApoE_P, plasma-derived Apolipoprotein E; A1AT, alpha-1-antitrypsin; Apo E2, recombinant human Apolipoprotein E of isoform ε2 from Athens Research; Apo E3, recombinant human Apolipoprotein E of isoform ε3 from Athens Research; Apo E4, recombinant human Apolipoprotein E of isoform ε4 from Athens Research.

Figure 4. ApoE inhibition of complement is context dependent.

We analyzed inhibition of C4b and sC5b-9 deposition on positive control (label ‘C’ on x-axis, coated heat-aggregated IgG, 2.5 μg/mL; A, B), and inhibition of sheep erythrocyte lysis by ApoE (panel C), using recombinant ApoE of different isoforms and plasma-derived ApoE. Mean + SD of three individual experiments are shown. Samples per experiment were analyzed in duplicate and two-way ANOVA (A, C), and one-way ANOVA (B) with Dunnett’s post-tests were applied to determine statistically significant differences compared to the uninhibited controls (label ‘C’ in panel A and B, and ‘0 μg/mL’ conditions per protein in panel C). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. IgG, heat-aggregated IgG (2.5 μg/mL); ApoE, Apolipoprotein E (10 μg/mL in panel A); A1AT, alpha-1-antitrypsin (10 μg/mL); C, control on coated IgG, with amboceptor and without inhibitors; BSA, bovine serum albumin (10 μg/mL); C1-inh, C1-inhibitor (20 μg/mL); C4BP, C4b-binding protein; PRELP, Proline And Arginine Rich End Leucine Rich Repeat Protein (50 μg/mL).

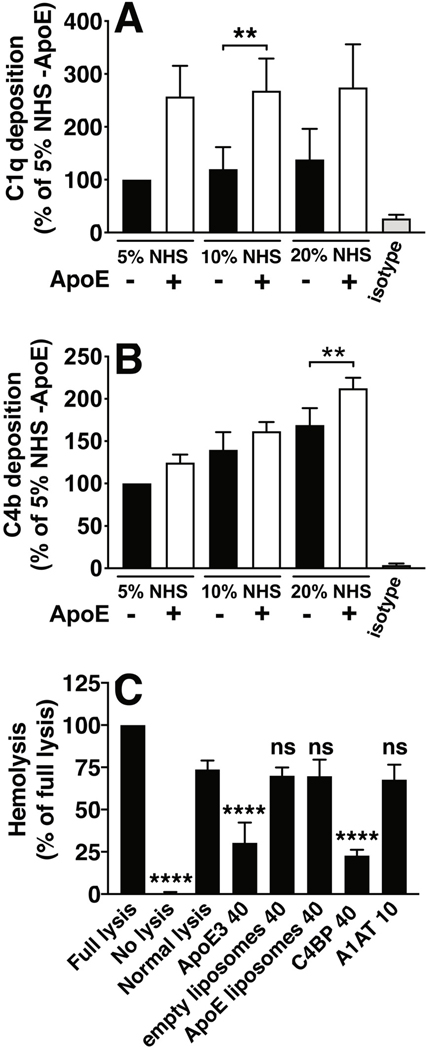

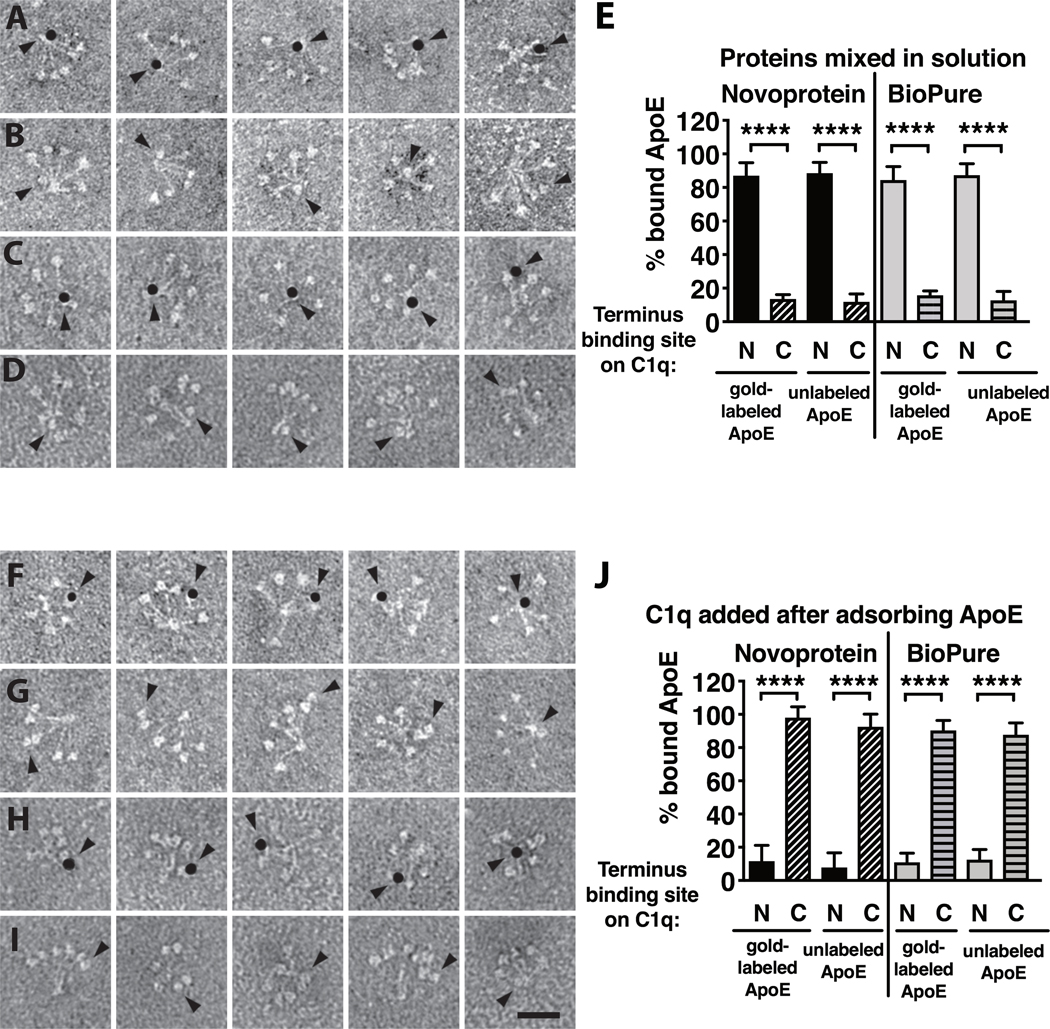

To confirm if ApoE interactions with complement could be context-dependent, i.e. different for immobilized ApoE vs. ApoE in solution, we also performed analysis of C1q-ApoE interactions with electron microscopy. There was a notable difference between adsorbing a solution of premixed C1q and ApoE vs. first adsorbing ApoE to the surface and adsorbing C1q subsequently. As depicted in Fig. 5A–5E, mixing C1q and ApoE in solution resulted in predominantly more ApoE binding to the hinge/stalk region of C1q (Novoprotein 88.5% ± 6.4; BioPure 87.3% ± 6.8) vs. the C1q head groups (Novoprotein 11.8% ± 4.7; BioPure 12.7% ± 5.2 ), while pre-adsorbing ApoE on the surface before adsorbing C1q, resulted in the opposite, i.e. binding occurring mostly via the head groups of C1q (Novoprotein 92.6% ± 7.6; BioPure 87.7% ± 7.1) and less to the stalks (Novoprotein 7.8% ± 8.9; BioPure 12.5% ± 6.0, Fig 5F–5J). To further investigate the interactions of immobilized ApoE with complement in a more physiological setting, we incorporated ApoE into PC/PE liposomes and analyzed complement deposition from serum using flow cytometry. ApoE-carrying liposomes induced a stronger binding of C1q, likely in C1 complex (as most of C1 in serum is in C1 complex), and a slightly stronger deposition of C4b compared to empty liposomes (Fig. 6A, B). In line with these results, we did not observe complement inhibition when ApoE-carrying liposomes were preincubated with normal human serum, and subsequently analyzed for the inhibitory effect on complement mediated sheep erythrocyte hemolysis, while free, unlipidated ApoE did inhibit hemolysis (Fig. 6C).

Figure 5. Electron microscopy of ApoE and C1q interactions.

Recombinant human ApoE of the ε3 isoform from Novoprotein and BioPure, with (A, C) and without (B, D) gold-label and human plasma derived C1q were mixed in solution and adsorbed simultaneously to a dark stained surface to allow for negative imaging. In addition, ApoE with (F, H) and without (G, I) gold-label were allowed to adsorb to a dark stained surface, followed by adsorption of C1q. All experiments were performed once, and per condition 50 fields were evaluated. Quantification of mean + SD of at least 500 counted particles per field is depicted in panels E and J. Scale bar is 25 nm in panel I. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post-test was applied to determine statistically significant differences between conditions, ****p<0.0001. N-terminal ApoE-Au, gold-labeled ApoE bound to the N-terminal stalk region of C1q; C-terminal ApoE-Au, gold-labeled ApoE bound to the C-terminal globular heads of C1q. N-terminal ApoE, non-labeled ApoE bound to the N-terminal stalk region of C1q; C-terminal ApoE, non-labeled ApoE bound to the C-terminal globular heads of C1q.

Figure 6. Flow cytometry analysis and hemolytic assay of complement deposition/inhibition by ApoE-carrying and empty liposomes.

Recombinant human ApoE of the ε3 isoform from Novoprotein was incorporated into PC/PE liposomes which were then coupled to streptavidin Dynabeads and complement deposition from NHS was assessed using primary antibodies against C1q (panel A) and C4b (panel B), followed by AF488-coupled secondary antibodies and mean fluorescence intensity was measured with flow cytometry. In addition, we tested the inhibitory capacity of ApoE when incorporated into liposomes, using a hemolytic assay of sheep erythrocytes. Flow cytometry data are normalized to empty liposomes incubated with 5% NHS as a basal value which was set to 100%, and mean + SD of 8 individual experiments are shown. Flow cytometry samples per experiment were analyzed in duplicate and two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test was applied to determine statistically significant differences between empty liposomes and ApoE-carrying liposomes. Hemolytic assay was performed three times, mean + SD are plotted as percentage of full lysis, and one-way ANOVA with Dunnetts’s multiple-comparisons test was applied to determine statistically significant differences compared with normal lysis. Concentrations provided on y-axis labels are in μg/mL. NHS, normal human serum.

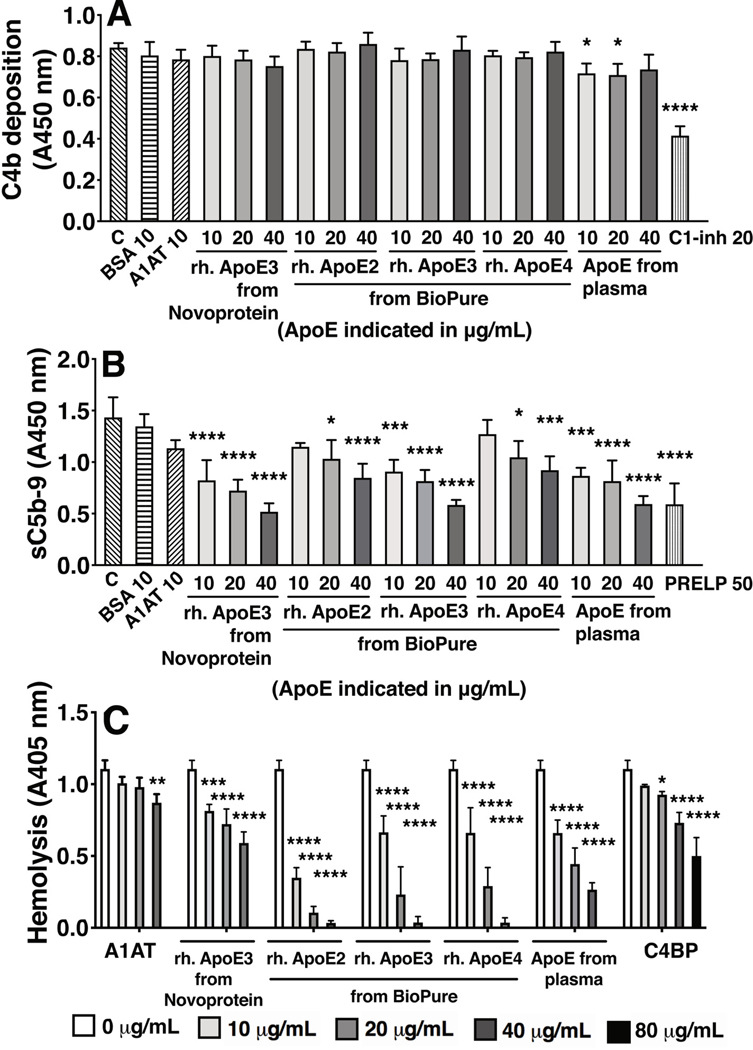

Post-translational modifications alter the capacity of ApoE to induce complement activation

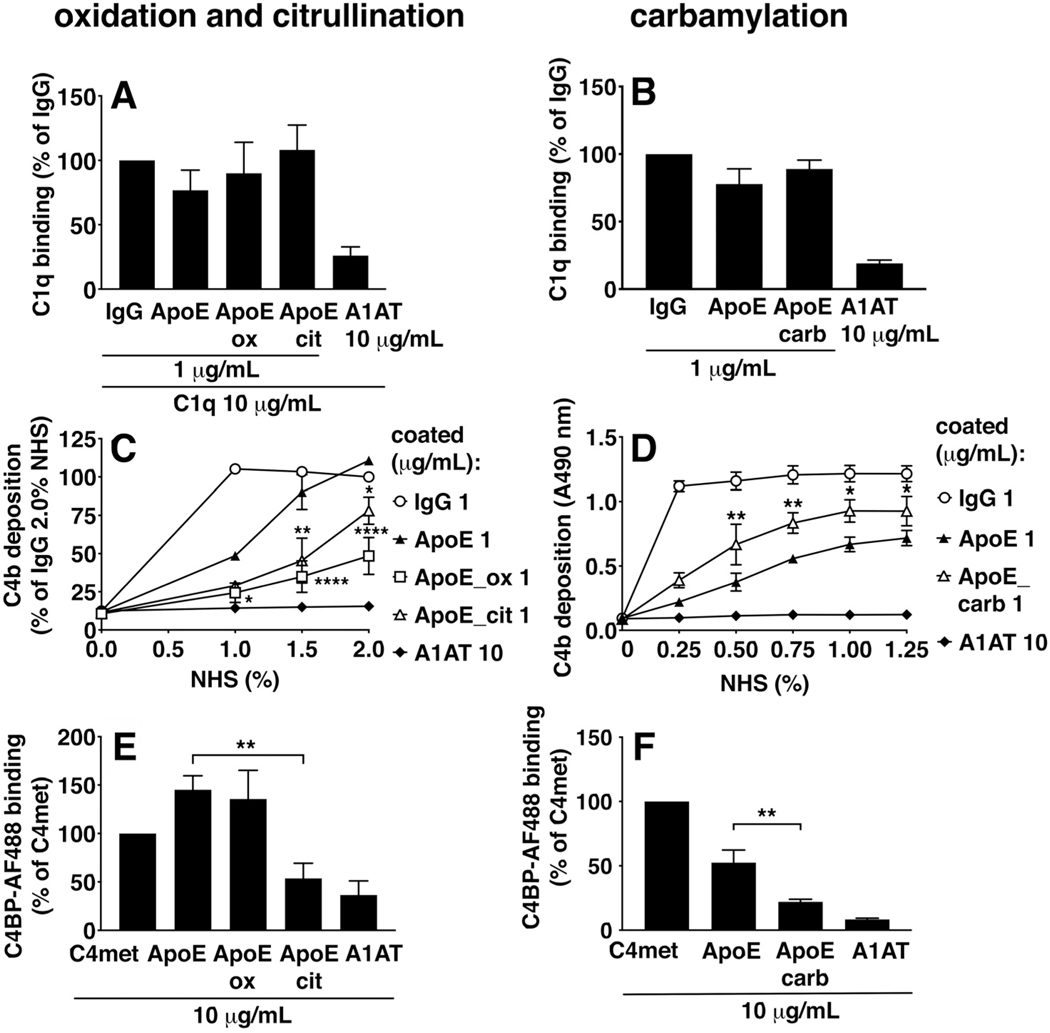

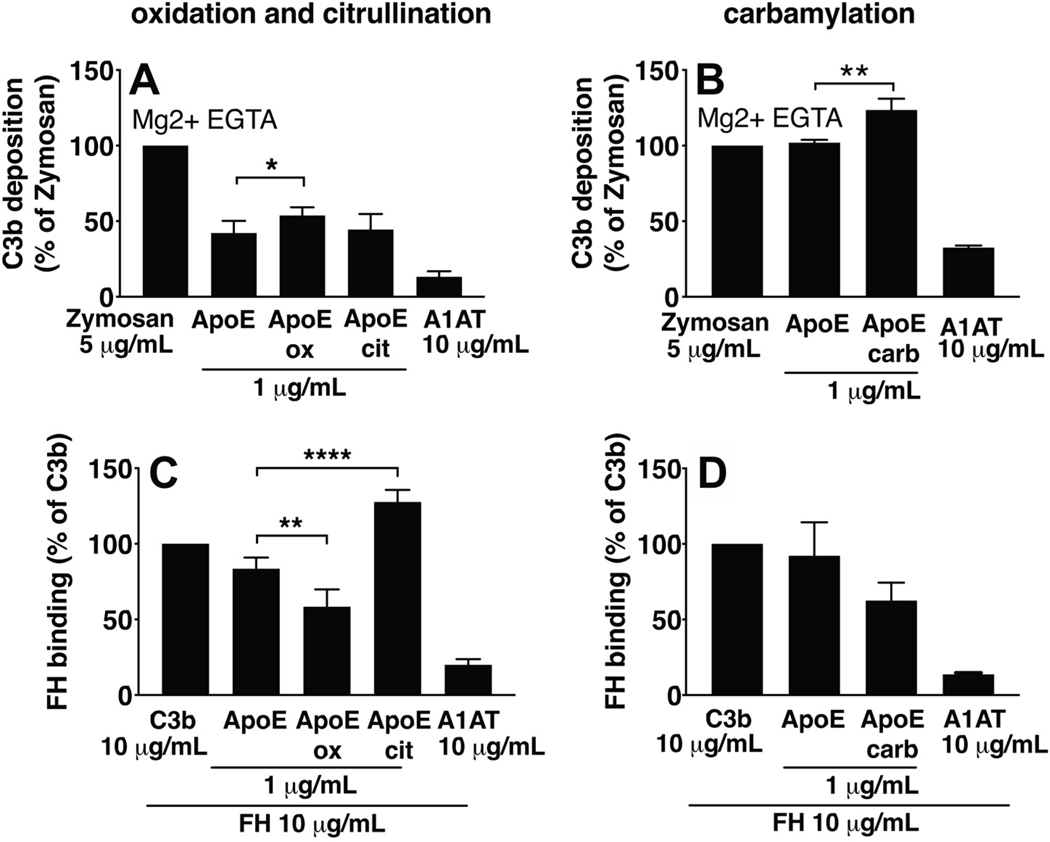

Citrullination, oxidation, and carbamylation were induced on ApoE-coated microtiter plates (Fig. 7 and 8). Considering effects on classical pathway activation, C1q binding was not altered upon citrullination, oxidation (panel 7A), nor carbamylation (panel 7B) of ApoE. C4b deposition was decreased upon ApoE citrullination and oxidation (panel 7C), whereas it was increased upon ApoE carbamylation (panel 7D). As differences in C4BP binding might explain altered interactions with C4b, we tested the effects of ApoE modifications on C4BP binding. We observed that C4BP binding was strongly decreased upon ApoE citrullination, that oxidation had no effect (panel 7E), and that carbamylation of ApoE also decreased C4BP binding (panel 7F). To study the effects of ApoE modifications on the alternative pathway, we measured C3b deposition in Mg2+EGTA buffer (Fig. 8), and found that citrullination of ApoE had no effect (panel 8A), and both oxidation (panel 8A) and carbamylation (panel 8B) of ApoE increased C3b deposition. Differences in both C4BP binding as well as FH binding might explain altered interactions with C3b, so we also studied the effects of ApoE modifications on FH binding. We observed that citrullination of ApoE increased its FH binding (panel 8C), whereas oxidation decreased FH binding (panel 8C), and carbamylation had no effect (panel 8D).

Figure 7. Post-translational modifications of ApoE alter its capacity to activate the classical pathway.

Oxidation, citrullination, and carbamylation were induced on ApoE-coated Maxisorp plates followed by incubation with either protein solutions of C1q (A, B), incubation with NHS to assay C4b deposition in GVB++ buffer (C, D), or incubation with protein solutions of AF488-labeled C4BP (E, F). C1q binding was assayed using primary antibody and HRP-labeled secondary antibody and colorimetric assay, and C4BP binding was assayed using Alexa Fluor 488-prelabeled C4BP and fluorescence measurements. C1q binding, C4b deposition on ApoE_ox and ApoE_cit, and C4BP were normalized to 1 μg/mL IgG (A, B), to 1 μg/mL IgG at 2% NHS (C) or to 10 μg/mL C4met (E, F). Mean + SD (A, B, E, F) or ± SD (C, D) of three individual experiments are shown. Samples per experiment were analyzed in duplicate and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s (A, B, E, F) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s (C, D) multiple-comparisons test were applied to determine statistically significant differences compared to untreated ApoE. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001. IgG, heat-aggregated IgG; ApoE, recombinant human ApoE of the ε3 isoform from Novoprotein; ApoE_ox, oxidized ApoE; ApoE_cit, citrullinated ApoE; ApoE_carb, carbamylated ApoE; A1AT, alpha-1-antitrypsin. C4met, methylamine-treated C4.

Figure 8. The effects of post-translational modifications of ApoE on its capacity to activate the alternative pathway.

Oxidation, citrullination, and carbamylation were induced on ApoE-coated Maxisorp plates, followed by incubation with either NHS in Mg2+-EGTA buffer to assay C3b deposition (A, B), or with protein solutions of FH (C, D). Data per experiment were normalized to the positive controls (Zymosan for A and B; C3b for C and D), and are plotted as a percentage. FH binding was assayed using primary antibody and HRP-labeled secondary antibody and colorimetric assay. Mean + SD of three individual experiments are shown. Samples per experiment were analyzed in duplicate and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test were applied to determine statistically significant differences compared to untreated ApoE. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001. ApoE, recombinant human ApoE of the ε3 isoform from Novoprotein (1 (A) and 10 μg/mL B-D)). ApoE_ox, oxidized ApoE; ApoE_cit, citrullinated ApoE; ApoE_carb, carbamylated ApoE; A1AT, alpha-1-antitrypsin (10 μg/mL). ApoE_ox, oxidized ApoE coated at 10 μg/mL; ApoE_cit, citrullinated ApoE coated at 10 μg/mL; ApoE_carb, carbamylated ApoE coated at 10 μg/mL; A1AT, alpha-1-antitrypsin (10 μg/mL), Zymosan (5 μg/mL), C3b (10 μg/mL).

C4d and ApoE are both present in SF of RA patients but do not correlate with each other or with common disease markers of RA

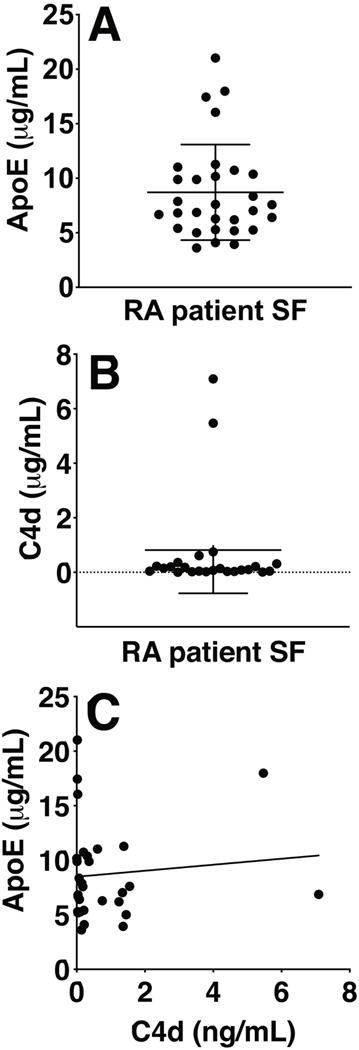

To evaluate if the amount of ApoE in SF of RA patients correlated with the amount of C4d or with common disease markers of RA, both ApoE and C4d were measured in SF from a 30 patients cohort using ELISAs. ApoE and C4d were present in significant amounts in the SF samples (Fig. 9A and 9B), however, no correlation between ApoE and C4d could be detected in this cohort (Fig. 9C). ApoE also did not correlate with any of the documented disease parameters such as ESR, disease duration, SF leukocyte count etc. (data not shown).

Figure 9. ELISA measurements and correlation analysis of C4d and ApoE in SF of RA patients.

A commercial ELISA was used for measuring ApoE (A), and an in-house developed ELISA (B) was used for measuring C4d in the SF of 30 RA patients. Assays were performed once, in single wells, to limit the amount of required patient material. ApoE and C4d concentrations were calculated using standard curves and plotted in ng/mL, with mean ± SD. Using the Spearman R test, no significant correlation was observed between C4d and ApoE in the SF of this cohort (C).

Discussion

Pathogenicity of autoantibodies directed at post-translationally modified targets is one mechanism that could induce or aggravate inflammation in RA, and direct modulation of complement activation by modified protein may also play a role in RA pathogenesis. Therefore, we investigated complement activation by apolipoproteins, which were identified from pooled SF of RA patients, either in complex with C4d or C3b, and we induced post-translational modifications of ApoE in vitro to evaluate possible alterations in complement-activating capacity. We observed that ApoE activated both the classical and alternative complement pathway. Immobilized ApoE was bound by the head groups of C1q; many other ligands that cause activation of C1q bind to the head groups while ligands for the stalk regions generally exert classical pathway inhibition. Therefore the observation that ApoE binds C1q head domains was in line with its ability to activate complement (45). The apparent difference in absorbance signal obtained for C4b deposition from 2% normal serum (panel 1A), and the assay where 2% C1q depleted serum was also included (panel 1E) can be explained by a difference in incubation time with the developing solution, however, the ratio between C4b deposition for IgG vs. ApoE is virtually the same.

Interactions between complement and ApoE have been reported in the context of other diseases such as age-related macular degeneration. Complement activation induces accumulation of ApoE in retinal pigment epithelium cells (46), suggesting that there may be a feedback loop causing increased complement activation and ApoE accumulation, leading to a vicious circle. In Alzheimer’s disease, the isotype of ApoE is considered important in the pathogenesis, and the ε4 isoform has been shown to induce the highest risk with the worst disease outcome (47). This is thought to be related to decreased complement-mediated clearance of beta amyloid (48), as well as increased complement activation by beta amyloid (49). Human ApoE exists in 3 isoforms, ε2, ε3, and ε4, which differ at residue 112 (Site A) and residue 158 (Site B) (50). ε3, with a cysteine on Site A and an arginine on Site B, is the most prevalent isoform and considered as wild type (14). ε2 has an arg158-to-cys modification, and ε4 has a cys112-to-arg alteration (50). ApoE isoforms also predispose differently to cardiovascular disease; Apo-ε2 increases atherogenic lipoprotein levels by binding poorly to low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors, whereas Apo-ε4 increases LDL levels by binding preferentially to triglyceride-rich, very low density lipoproteins, leading to downregulation of LDL receptors (51). Interestingly, in an atherosclerosis mouse model of acute loss of wild type ApoE, this loss induced rapid production of antibodies recognizing rheumatoid disease autoantigens (52). The authors also reported that the immune response that followed loss of ApoE was independent of atherosclerosis but promoted plaque development. In RA patients, the type of expressed isoform has not been found to play a role in the joint as yet (42, 53), but the tertiary structures of the individual isoforms may provide us with clues to study ApoE function after modifications, and raise the question whether certain post-translational modifications can modulate the ε2 and ε3 isoform to adopt an ε4-like conformation for example. Although Apo-ε2 and Apo-ε 4 show a non-significant trend of slightly higher C1q deposition compared to Apo-ε3, it appears in retrospect that mutations unrelated to the natural isoforms are more meaningful (42, 53), as some are strong predictors of inflammation and dyslipidemia in RA. The rationale to study the different isoforms was to evaluate whether that could have been the determinant difference between the results reported by Yin et al. (43) who showed complement inhibition by ApoE, compared to our initial results where we observed the activation of complement. We then confirmed their in vitro findings that all ApoE isoforms inhibit the classical complement pathway by binding C1q in solution, and we also found that ApoE can indeed form complexes with C1q. Our study demonstrated however, that not all ApoE-C1q complexes are created equal, and that the physiologic state of the ApoE molecule is paramount to the way it interacts with C1q. It provides opposite results for ApoE in solution vs. deposited ApoE, determined by the typical binding site of C1q it ligates, i.e. to the head groups when ApoE is deposited, initiating an activating signal, and to the hinge/stalk region of C1q when both molecules are in solution, causing inhibition of complement, and which can be considered the physiological, healthy, normal state that can most likely be found in normal circulation. Although different formulations of recombinant Apo-ε3 can have different stability that could result in different magnitude of effect on complement activation or inhibition, both tested Apo-ε3 demonstrated the dependence on solubility or adsorbed state on the site of C1q binding in the EM experiments. Despite the important and extensive information that Yin et al. have obtained from the use of an ApoE knockout mouse model, this model has the disadvantage that it is difficult to discern the fine distinctions between complement inhibitory vs. complement activating effects of ApoE, due to the absence of the molecule. The nuance of reactions that might occur when ApoE is deposited on a surface followed by complement deposition can not be modeled, and may be overlooked. Another difference between their approach and the current study is that they focused on the effects of oxidized lipids, while we chose to apply our protein modifications directly on ApoE itself, as we expected this would also affect its interactions with complement.

In our binding assays we confirmed the observation that native, unmodified ApoE is capable of binding complement inhibitor FH (54). The interaction was shown previously to occur via CCP domains 5–7 and plays an important role in prevention of complement attack on plasma HDL particles by regulating alternative pathway activation on the surface of these particles. These findings, combined with our current results warrant further investigation of the interactions of FH and ApoE-carrying HDL particles in the context of RA. To the best of our knowledge, we report for the first time that ApoE is also capable of binding C4BP. Considering the interactions with FH, C4BP may play a similar protective role on ApoE-carrying particles. This may suggest that its binding capacity for FH and C4BP would be an important protective mechanism to avoid complement activation by ApoE itself, and perhaps also on its molecular cargo during transport in lipoprotein particles. Moreover, altered binding capacity towards FH and C4BP, induced by post-translational modifications of ApoE, could be an underlying mechanism of increased complement activation in disease. Our findings prompt further studies into the role of these complement inhibitors in regulating complement activation on ApoE in lipoprotein particles.

In addition to its activating capacities, we also found evidence of context-dependent complement inhibition by ApoE. Besides the notion that the effects of ApoE on the body are tissue and cell type specific, our results suggest that ApoE could also play different roles in healthy vs. diseased situations. In our hands, ApoE in solution did not disrupt C4b deposition by aggregated IgG, but did inhibit IgG-induced sC5b-9 formation. This result was consistent with the observed C1q and C4b deposition on liposomes carrying ApoE, demonstrating deposition up to the C4b level. It is tempting to compare the inhibitory effect with the action of another apolipoprotein, ApoJ, or clusterin, which directly inhibits formation of membrane attack complex. Thus, effect of ApoE on terminal complement pathway warrants future studies. In the highly sensitive hemolysis inhibition assay, Apo-ε3 from BioPure appeared to have a stronger inhibitory capacity than that induced by Apo-ε3 from Novoprotein. This could be explained by a difference in protein quality and stability between different manufacturers, and stresses the importance of critical evaluation of the results. In future experiments, this possible difference in stability should be taken into account as we found ApoE to loose its activity within couple of months even upon storage in –80°C. ApoE exists in tetramers, dimers, and monomers, depending on its concentration (55) and it was established that ApoE is required to be in monomeric form to accept lipids and to form a lipid disk as the beginning of a lipoprotein particle, but the consequences for binding other ligands plus the downstream effects are still not clear at this point. Interestingly, serum concentrations of ApoE are estimated to be within a close range of 40 μg/mL (56), suggesting that not all ApoE in circulation would be lipidated, which may provide an in vivo explanation for the inhibitory effects that were observed with the non-lipidated ApoE. It also remains to be studied whether post-translational modifications of ApoE also induce harmful proinflammatory changes in that regard, for example via inhibiting ApoE clearance, causing accumulation, which could then lead to concentration dependent dimerization, tetramerization, and possibly deposition, followed by loss of normal function and contributing to inflammation instead.

Unfortunately, we were not able to measure C4d-ApoE complexes in SF of RA patients using sandwich ELISAs due to high background signals, possibly from ACPA and RF. Upon measuring ApoE and C4d separately in SF of 30 patients we found no correlation between ApoE and C4d (Fig. 9), nor between ApoE and any of the basic clinical parameters that were documented for these patients (ESR, disease duration, SF leukocyte count etc.). This does not exclude the presence of C4d-ApoE complexes, as they may be masked by the abundance of other C4d-bound complement activators, and/or it can be due to interpatient differences in ACPA fine-specificity profiles as reported (57), in case ApoE is an autoantigen in a distinct subpopulation. ApoE is mentioned in a few previous studies as a possible target that causes inflammation in RA (42, 53, 58), and both the presence of antibody directed at citrullinated ApoE (2, 18, 59) as well as the presence of the citrullinated ApoE protein itself (18) have been linked to RA or RA-risk. This supports the notion that our findings are not likely in vitro artefacts. The ApoE we found in covalent complex with C4d might be there because of direct binding of C4d, but might also first have been bound by an autoantibody, which then binds and activates the classical complement pathway. For the patients included in this study that have undergone knee synovial fluid aspiration, no data was available on the status of the damage of the affected knee joint, therefore this could not be analyzed for any correlation with ApoE concentration in the SF. Unfortunately, we neither had access to synovial membrane biopsies from patients, although in light of our findings, this would have been very interesting for a comparison of soluble vs. deposited ApoE, as the major differences in function are more likely to emerge from that particular physical status of ApoE.

The most important findings in our study are that in pooled SF of RA patients, ApoE was found in complex with complement component C4d, but that the interactions of ApoE with the complement system are complex because they are dual and highly context-dependent. In contrast with its capacity to activate the classical and alternative complement pathways in a deposited state, we also confirmed previously reported opposite effects (i.e. complement inhibition) for ApoE in solution. Additionally, we observed that carbamylation appears to enhance ApoE-mediated complement activation. Bearing in mind that we identified ApoE as a covalently bound target of C4d in SF of RA patients (12), these results suggest that in RA, ApoE is likely to be present in an immobilized form in the synovium, either bound to the local tissue or to particulate matter in suspension, where it subsequently may cause complement deposition. Our results call for further investigation into the role of ApoE in natural as well as inflammatory processes in the joint, and evaluation of possible correlations of post-translationally modified ApoE with RA clinical markers and disease severity. Our ongoing research is aimed at answering whether ApoE could be a suitable target for the development of novel therapeutic strategies and diagnostic tests for RA.

Key points.

ApoE was found in a complex with C4d in RA patient SF

Deposited ApoE activates complement while ApoE in solution is inhibitory

Post-translational modifications alter ApoE’s capacity to bind FH and C4BP

Acknowledgements

Ewa Kwasniewicz is a student of Biotechnology at the University of Rzeszow, Poland. We are grateful to the staff in the BioEM Lab, Biozentrum, University of Basel, the Microscopy Facility at the Department of Biology, Lund University, and the Core Facility for Integrated Microscopy (CFIM), Panum Institute, University of Copenhagen, for providing highly innovative environments for electron microscopy. We thank Cinzia Tiberi (BioEM lab), and Ola Gustafsson (Microscopy Facility) for skillful work, Carola Alampi (BioEM lab), Mohamed Chami (BioEM lab) and Klaus Qvortrup (CFIM) for practical help with electron microscopy.

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (Grant 2018-02392, 2016-2075-5.1), the Österlund Foundation, King Gustaf V’s 80th Anniversary Foundation, Lars Hiertas Minne Foundation, The Royal Physiographic Society in Lund, Professor Nanna Svartz Stiftelsen, Längmanska Kulturfonden, as well as grants for clinical research from ALF and Skåne University Hospital. Ewa Kwasniewicz is a student of biotechnology at Rzeszow University, Poland. Ewa Bielecka and Jan Potempa were supported by grants from National Science Center (UMO-2018/30/M/NZ1/00367 and UMO-2018/30/A/NZ5/00650) and NIH/NIDCR (R01 DE022597).

Abbreviations:

- A1AT

α−1-antitrypsin

- ApoE

Apolipoprotein E

- CBB

Coating-Binding-Blocking

- C4BP

C4b-Binding Protein

- FB

Factor B

- FH

Factor H

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NHS

normal human serum

- PAD4

peptidyl arginine deiminase 4

- PC/PE

phosphatidylcholine/ phoshatidyethnolamine

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- SF

synovial fluid

- VBS

Veronal buffered saline

References

- 1.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, and McInnes IB. 2016. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet (London, England) 388: 2023–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demoruelle MK, Bowers E, Lahey LJ, Sokolove J, Purmalek M, Seto NL, Weisman MH, Norris JM, Kaplan MJ, Holers VM, Robinson WH, and Deane KD. 2018. Antibody Responses to Citrullinated and Noncitrullinated Antigens in the Sputum of Subjects With Rheumatoid Arthritis and Subjects at Risk for Development of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. (Hoboken, N.J.) 70: 516–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okroj M, Heinegård D, Holmdahl R, and Blom AM. 2007. Rheumatoid arthritis and the complement system. Ann. Med. 39: 517–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moxley G, and Ruddy S. 1985. Elevated C3 anaphylatoxin levels in synovial fluids from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 28: 1089–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jose PJ, Moss IK, Maini RN, and Williams TJ. 1990. Measurement of the chemotactic complement fragment C5a in rheumatoid synovial fluids by radioimmunoassay: role of C5a in the acute inflammatory phase. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 49: 747–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swaak AJ, Van Rooyen A, Planten O, Han H, Hattink O, and Hack E. 1987. An analysis of the levels of complement components in the synovial fluid in rheumatic diseases. Clin. Rheumatol. 6: 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brodeur JP, Ruddy S, Schwartz LB, and Moxley G. 1991. Synovial fluid levels of complement SC5b-9 and fragment Bb are elevated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 34: 1531–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan BP, Daniels RH, and Williams BD. 1988. Measurement of terminal complement complexes in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 73: 473–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmid FR, Roitt IM, and Rocha MJ. 1970. Complement fixation by a two-component antibody system: immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M anti-globulin (rheumatoid factor). Parodoxical effect related to immunoglobulin G concentration. J. Exp. Med. 132: 673–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SY, Son M, Lee SE, Park IH, Kwak MS, Han M, Lee HS, Kim ES, Kim J-Y, Lee JE, Choi JE, Diamond B, and Shin J-S. 2018. High-Mobility Group Box 1-Induced Complement Activation Causes Sterile Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 9: 705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersson U, and Erlandsson-Harris H. 2004. HMGB1 is a potent trigger of arthritis. J. Intern. Med. 255: 344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogt LM, Talens S, Kwasniewicz E, Scavenius C, Struglics A, Enghild JJ, Saxne T, and Blom AM. 2017. Activation of Complement by Pigment Epithelium–Derived Factor in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Immunol. 199: 1113–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahley RW, and Innerarity TL. 1983. Lipoprotein receptors and cholesterol homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 737: 197–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahley RW, and Rall SCJ. 2000. Apolipoprotein E: far more than a lipid transport protein. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 1: 507–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Wu L-M, and Wu J. 2011. Cross-talk between apolipoprotein E and cytokines. Mediators Inflamm. 2011: 949072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Steendam K, De Ceuleneer M, Tilleman K, Elewaut D, De Keyser F, and Deforce D. 2013. Quantification of IFNgamma- and IL17-producing cells after stimulation with citrullinated proteins in healthy subjects and RA patients. Rheumatol. Int. 33: 2661–2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawalkowska J, Quirke A-M, Ghari F, Davis S, Subramanian V, Thompson PR, Williams RO, Fischer R, La Thangue NB, and Venables PJ. 2016. Abrogation of collagen-induced arthritis by a peptidyl arginine deiminase inhibitor is associated with modulation of T cell-mediated immune responses. Sci. Rep. 6: 26430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Beers JJBC, Schwarte CM, Stammen-Vogelzangs J, Oosterink E, Bozic B, and Pruijn GJM. 2013. The rheumatoid arthritis synovial fluid citrullinome reveals novel citrullinated epitopes in apolipoprotein E, myeloid nuclear differentiation antigen, and beta-actin. Arthritis Rheum. 65: 69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang F, Chen F-F, Gao W-B, Wang H-Y, Zhao N-W, Xu M, Gao D-Y, Yu W, Yan X-L, Zhao J-N, and Li X-J. 2016. Identification of citrullinated peptides in the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis using LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF. Clin. Rheumatol. 35: 2185–2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi J, Knevel R, Suwannalai P, van der Linden MP, Janssen GMC, van Veelen PA, Levarht NEW, van AHM der Helm-van Mil A Cerami TWJ Huizinga REM Toes, and Trouw LA 2011. Autoantibodies recognizing carbamylated proteins are present in sera of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and predict joint damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108: 17372–17377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorisse L, Pietrement C, Vuiblet V, Schmelzer CEH, Köhler M, Duca L, Debelle L, Fornès P, Jaisson S, and Gillery P. 2016. Protein carbamylation is a hallmark of aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113: 1191–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Nicholls SJ, Rodriguez ER, Kummu O, Horkko S, Barnard J, Reynolds WF, Topol EJ, DiDonato JA, and Hazen SL. 2007. Protein carbamylation links inflammation, smoking, uremia and atherogenesis. Nat. Med. 13: 1176–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nilsson B, Ekdahl KN, Svensson KE, Bjelle A, and Nilsson UR. 1989. Distinctive expression of neoantigenic C3(D) epitopes on bound C3 following activation and binding to different target surfaces in normal and pathological human sera. Mol. Immunol. 26: 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tenner AJ, Lesavre PH, and Cooper NR. 1981. Purification and radiolabeling of human C1q. J. Immunol. 127: 648–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swinkels M, Zhang JH, Tilakaratna V, Black G, Perveen R, McHarg S, Inforzato A, Day AJ, and Clark SJ. 2018. C-reactive protein and pentraxin-3 binding of factor H-like protein 1 differs from complement factor H: implications for retinal inflammation. Sci. Rep. 8: 1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin M, Leffler J, Smolag KI, Mytych J, Bjork A, Chaves LD, Alexander JJ, Quigg RJ, and Blom AM. 2016. Factor H uptake regulates intracellular C3 activation during apoptosis and decreases the inflammatory potential of nucleosomes. Cell Death Differ. 23: 903–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blom AM, Kask L, and Dahlback B. 2001. Structural requirements for the complement regulatory activities of C4BP. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 27136–27144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sjoberg A, Onnerfjord P, Morgelin M, Heinegard D, and Blom AM. 2005. The extracellular matrix and inflammation: fibromodulin activates the classical pathway of complement by directly binding C1q. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 32301–32308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baschong W, Lucocq JM, and Roth J. 1985. “Thiocyanate gold”: small (2–3 nm) colloidal gold for affinity cytochemical labeling in electron microscopy. Histochemistry 83: 409–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao Y-F, Hsieh H-C, Liu G-Y, and Hung H-C. 2005. A continuous spectrophotometric assay method for peptidylarginine deiminase type 4 activity. Anal. Biochem. 347: 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okroj M, Mark L, Stokowska A, Wong SW, Rose N, Blackbourn DJ, Villoutreix BO, Spiller OB, and Blom AM. 2009. Characterization of the complement inhibitory function of rhesus rhadinovirus complement control protein (RCP). J. Biol. Chem. 284: 505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nilsson SC, Karpman D, Vaziri-Sani F, Kristoffersson A-C, Salomon R, Provot F, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Trouw LA, and Blom AM. 2007. A mutation in factor I that is associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome does not affect the function of factor I in complement regulation. Mol. Immunol. 44: 1835–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heinegård D, Aspberg A, Franzén A, L P 2002. Non-collagenous glycoproteins in the extracellular matrix, with particular reference to cartilage and bone.,. Wiley-Liss, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins JR, Longnecker K, Fredricks HF, and Van Mooy BAS. 2017. Part 1: Preparation of lipid films for phospholipid liposomes In The remineralization of marine organic matter by diverse biological and abiotic processes., 2nd ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts; 300. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collins JR, Longnecker K, Fredricks HF, and Van Mooy BAS. 2017. Part 2: Extrusion and suspension of phospholipid liposomes from lipid fims. In The remineralization of marine organic matter by diverse biological and abiotic processes., 2nd ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts; 300. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laabei M, Liu G, Ermert D, Lambris JD, Riesbeck K, and Blom AM. 2018. Short Leucine-Rich Proteoglycans Modulate Complement Activity and Increase Killing of the Respiratory Pathogen Moraxella catarrhalis. J. Immunol. 201: 2721–2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kraaij T, Nilsson SC, van Kooten C, Okroj M, Blom AM, and Teng YO. 2019. Measuring plasma C4D to monitor immune complexes in lupus nephritis. Lupus Sci. Med. 6: e000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders AM, Schmader K, Breitner JC, Benson MD, Brown WT, Goldfarb L, Goldgaber D, Manwaring MG, Szymanski MH, and McCown N. 1993. Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele distributions in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease and in other amyloid-forming diseases. Lancet (London, England) 342: 710–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baird PN, Guida E, Chu DT, V Vu HT, and Guymer RH. 2004. The epsilon2 and epsilon4 alleles of the apolipoprotein gene are associated with age-related macular degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45: 1311–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haines JL, Hauser MA, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Olson LM, Gallins P, Spencer KL, Kwan SY, Noureddine M, Gilbert JR, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Agarwal A, Postel EA, and Pericak-Vance MA. 2005. Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science 308: 419–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark SJ, McHarg S, Tilakaratna V, Brace N, and Bishop PN. 2017. Bruch’s Membrane Compartmentalizes Complement Regulation in the Eye with Implications for Therapeutic Design in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Front. Immunol. 8: 1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maehlen MT, Provan SA, de Rooy DPC, van der Helm - van Mil AHM , Krabben A, Saxne T, Lindqvist E, Semb AG, Uhlig T, van der Heijde D, Mero IL, Olsen IC, Kvien TK, and Lie BA. 2013. Associations between APOE Genotypes and Disease Susceptibility, Joint Damage and Lipid Levels in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. PLoS One 8: e60970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yin C, Ackermann S, Ma Z, Mohanta SK, Zhang C, Li Y, Nietzsche S, Westermann M, Peng L, Hu D, Bontha SV, Srikakulapu P, Beer M, Megens RTA, Steffens S, Hildner M, Halder LD, Eckstein H-H, Pelisek J, Herms J, Roeber S, Arzberger T, Borodovsky A, Habenicht L, Binder CJ, Weber C, Zipfel PF, Skerka C, and Habenicht AJR. 2019. ApoE attenuates unresolvable inflammation by complex formation with activated C1q. Nat. Med. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Storm D, Herz J, Trinder P, and Loos M. 1997. C1 inhibitor-C1s complexes are internalized and degraded by the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 31043–31050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sjoberg AP, Manderson GA, Morgelin M, Day AJ, Heinegard D, and Blom AM. 2009. Short leucine-rich glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix display diverse patterns of complement interaction and activation. Mol. Immunol. 46: 830–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang P, Skiba NP, Tewkesbury GM, Treboschi VM, Baciu P, and Jaffe GJ. 2017. Complement-Mediated Regulation of Apolipoprotein E in Cultured Human RPE Cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58: 3073–3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, and Pericak-Vance MA. 1993. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science 261: 921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wildsmith KR, Holley M, Savage JC, Skerrett R, and Landreth GE. 2013. Evidence for impaired amyloid β clearance in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers. Res. Ther. 5: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGeer PL, Walker DG, Pitas RE, Mahley RW, and McGeer EG. 1997. Apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4) but not ApoE3 or ApoE2 potentiates beta-amyloid protein activation of complement in vitro. Brain Res. 749: 135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weisgraber KH, Rall SCJ, and Mahley RW. 1981. Human E apoprotein heterogeneity. Cysteine-arginine interchanges in the amino acid sequence of the apo-E isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 256: 9077–9083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahley RW 2016. Apolipoprotein E: from cardiovascular disease to neurodegenerative disorders. J. Mol. Med. (Berl). 94: 739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Centa M, Prokopec KE, Garimella MG, Habir K, Hofste L, Stark JM, Dahdah A, Tibbit CA, Polyzos KA, Gistera A, Johansson DK, Maeda NN, Hansson GK, Ketelhuth DFJ, Coquet JM, Binder CJ, Karlsson MCI, and Malin S. 2018. Acute Loss of Apolipoprotein E Triggers an Autoimmune Response That Accelerates Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toms TE, Smith JP, Panoulas VF, Blackmore H, Douglas KMJ, and Kitas GD. 2012. Apolipoprotein E gene polymorphisms are strong predictors of inflammation and dyslipidemia in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 39: 218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haapasalo K, van Kessel K, Nissila E, Metso J, Johansson T, Miettinen S, Varjosalo M, Kirveskari J, Kuusela P, Chroni A, Jauhiainen M, van Strijp J, and Jokiranta TS. 2015. Complement Factor H Binds to Human Serum Apolipoprotein E and Mediates Complement Regulation on High Density Lipoprotein Particles. J. Biol. Chem. 290: 28977–28987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garai K, Baban B, and Frieden C. 2011. Dissociation of apolipoprotein E oligomers to monomer is required for high-affinity binding to phospholipid vesicles. Biochemistry 50: 2550–2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siest G, Bertrand P, Qin B, Herbeth B, Serot JM, Masana L, Ribalta J, Passmore AP, Evans A, Ferrari M, Franceschi M, Shepherd J, Cuchel M, Beisiegel U, Zuchowsky K, Rukavina AS, Sertic J, Stojanov M, Kostic V, Mitrevski A, Petrova V, Sass C, Merched A, Salonen JT, Tiret L, and Visvikis S. 2000. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and serum concentration in Alzheimer’s disease in nine European centres: the ApoEurope study. ApoEurope group. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 38: 721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Beers JJBC, Willemze A, Jansen JJ, Engbers GHM, Salden M, Raats J, Drijfhout JW, vander Helm-van Mil AHM, Toes REM, and Pruijn GJM. 2013. ACPA fine-specificity profiles in early rheumatoid arthritis patients do not correlate with clinical features at baseline or with disease progression. Arthritis Res. Ther. 15: R140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terkeltaub RA, Dyer CA, Martin J, and Curtiss LK. 1991. Apolipoprotein (apo) E inhibits the capacity of monosodium urate crystals to stimulate neutrophils. Characterization of intraarticular apo E and demonstration of apo E binding to urate crystals in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 87: 20–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Solow EB, Yu F, Thiele GM, Sokolove J, Robinson WH, Pruhs ZM, Michaud KD, Erickson AR, Sayles H, Kerr GS, Gaffo AL, Caplan L, Davis LA, Cannon GW, Reimold AM, Baker J, Schwab P, Anderson DR, and Mikuls TR. 2015. Vascular calcifications on hand radiographs in rheumatoid arthritis and associations with autoantibodies, cardiovascular risk factors and mortality. Rheumatology (Oxford). 54: 1587–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]