Abstract

HIV continues to disproportionately impact African American (AA) communities. Due to delayed HIV diagnosis, AAs tend to enter HIV treatment at advanced stages. There is great need for increased access to regular HIV testing and linkage to care (LTC) services for AAs. AA faith institutions are highly influential and have potential to increase the reach of HIV testing in AA communities. However, well-controlled full-scale trials have not been conducted in the AA church context. We describe the rationale and design of a 2-arm cluster randomized trial to test a religiously-tailored HIV testing intervention (Taking It to the Pews [TIPS]) against a standard information arm on HIV testing rates among AA church members and community members they serve. Using a community-engaged approach, TIPS intervention components are delivered by trained church leaders via existing multilevel church outlets using religiously-tailored HIV Tool Kit materials/activities (e.g., sermons, responsive readings, video/print testimonials, HIV educational games, text messages) to encourage testing. Church-based HIV testing events and LTC services are conducted by health agency partners. Control churches receive standard HIV education information. Secondarily, HIV risk/protective behaviors and process measures on feasibility, fidelity, and dose/exposure are assessed. This novel study is the first to fully test an HIV testing intervention in AA churches – a setting with great reach and influence in AA communities. It could provide a faith-community engagement model for delivering scalable, wide-reaching HIV prevention interventions by supporting AA faith leaders with religiously-appropriate HIV toolkits and health agency partners.

Keywords: African Americans, HIV testing, faith-based, multilevel intervention, community-based participatory research, Theory of Planned Behavior

INTRODUCTION

African Americans (AAs) continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV.1 In 2016, rates of new HIV infection were 8 and 16 times higher among AAs males and females than white males and females, respectively. Despite having similar delayed HIV diagnosis as whites,2 AAs are less likely to maintain care and achieve viral suppression, and tend to die from AIDS sooner,1–5 indicating the need to expand delivery of healthcare services with AAs across the HIV care continuum, including early and routine HIV testing, and linkage to care.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV screening guidelines recommend routine testing of persons aged 13 to 64 in medical settings.6 Using this strategy, individuals don’t have to be high risk to receive HIV testing. Yet, many AAs have limited access to medical settings, and missed HIV testing opportunities with AAs in these settings remain high.7–9 Routine testing also does little for AAs who have limited access to health services, and a myriad of testing barriers have been noted (e.g., HIV stigma, risk denial, distance to testing).10–13

It is estimated that 15 to 18% of people living with HIV are unaware of their status and may contribute to nearly 40% of all new HIV cases.14–16 The Updated National HIV/AIDS Strategy includes recommendations to extend the reach of HIV awareness and testing in heavily burdened, ethnic minority communities and calls for the faith community to assist with these efforts.17

AA faith institutions are highly influential and have a history of mobilizing AA communities for social and political change,18 and could greatly assist in increasing HIV awareness and access to testing. Most AA churches provide multilevel channels of communication for reaching congregants that might reduce barriers and increase HIV testing access for underserved AAs. Specifically, AA churches: a) have high congregant attendance, with greater church attendance in Southern and Midwestern regions of the country;19–20 b) are led by pastors who can greatly influence members’ health behaviors;21–22 c) engage congregants in frequent common religious activities (e.g., collective worship, testimonials, scripture reading) where culturally-religiously tailored prevention testing messages can be infused;23–25 d) emphasize taking care of one’s body -- seen as the “temple of God,”22 e) have a history of coordinating health-related activities;18,23–25 f) have outreach ministries (e.g., clothing/food programs, social services)23 that reach community members at great risk for HIV; and g) have infrastructure (e.g., meeting space, membership management/communication systems) and volunteers23–24 that can coordinate prevention and testing activities.

Studies have shown that many AA churches are willing to provide HIV testing services.26–30 However, faith leaders have also reported implementation challenges, including church capacity issues (e.g., lack of HIV training, church-appropriate HIV materials, time, resources), and controversies regarding certain risk behaviors (e.g., same sex relationships, injection drug use) and risk reduction strategies (e.g., condom use, clean needles).23,31–33 Past research has demonstrated the feasibility and impact of HIV testing interventions in AA churches with pastoral promotion of HIV testing in church service sermons and trained church leaders delivering religiously-tailored messages and educational materials interpersonally, through ministry groups, and in church services as key components.30,34–35 For example, using similar components, a pilot study (N=2 randomized AA churches) conducted by Derose and colleagues found significant increases in receipt of HIV testing in the intervention church compared to control at 6-months (32 versus 13%).34 Our most recent pilot study (n=4 randomized AA churches) used similar components, pastors modeling receipt of HIV testing from the pulpit, and HIV testing reminders via telephone tree messaging systems and also achieved significant increases in HIV testing compared to controls at 6 months (47 versus 28%) and 12 months (59% versus 42%).35 Though increasing in practice,26–28,30,34–35 no rigorously tested, well-controlled full-scale trials have been conducted in the AA church context.

This paper describes the design of a clustered, randomized community trial to test a culturally-religiously tailored, multilevel, church-based HIV testing intervention (Taking It to the Pews [TIPS]) against a standard information condition on HIV testing rates among adult AA church and community members.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Background and collaborating study partners

Using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, we implemented 2 earlier pilot phases of the TIPS religiously-culturally tailored multilevel intervention to address the many challenges reported by churches in addressing HIV.27,35 Our pilot studies demonstrated: a) trained church leaders can expertly deliver an HIV testing intervention using a prepackaged, supportive church-appropriate HIV tool kit;23,27,35 b) tool kit materials/activities designed with assistance from faith leaders were highly acceptable/feasible and increased reach to church members and community members using outreach services;23,27,35,36 c) church members will get tested during church-based HIV testing events,35,36 especially when exposed to TIPS,35 and d) significant increases in HIV testing rates could be achieved.35,36 Additionally, pilot participants were most frequently exposed to intervention components delivered at the churchwide level, particularly pastoral sermons and printed materials (e.g., brochures, church bulletins, posters, resource tables).35 However, the pilots were not appropriately powered, and post study focus groups indicated the need for additional modifications in the materials (e.g., testimonials and voice/text messages to further encourage testing). The focus groups and our health agency partners also indicated the need for onsite linkage to care services for persons who test positive for HIV to ensure timely receipt and maintenance of HIV healthcare services, and support with addressing social determinants of HIV health outcomes (e.g., access to health insurance, affordable food, housing, transportation). These issues were addressed collaboratively with our partners in the refinement of TIPS for this clinical trial.

Using our (CBPR) approach, faith and health agency partners were involved in all aspects of the TIPS pilot studies and are fully involved in the clinical trial.27,35 Calvary Community Outreach Network (CCON) is our primary faith organization partner, and has been the long-time convener of the National Church Week of Prayer (NCWP; formerly “Black Church Week of Prayer”) for the Healing of AIDS in Kansas City (KC), which traditionally provided church-based HIV testing with minimal uptake. CCON assisted the study team in linking to KC Missouri and KC Kansas churches that could possibly meet our church selection criteria and assisted with survey and procedures development. Through all phases of our pilot studies and in preparation for the clinical trial, AA faith leaders assisted in developing and refining many of the religiously-culturally tailored TIPS materials/activities, which were packaged in a TIPS HIV Tool Kit (described below) for easy delivery in existing church services and activities in intervention arm churches.23,35 Faith leaders also participated in identifying the study outcome (receipt of HIV testing), implementing and evaluating the intervention, discussing study progress, and coordinating community meetings to discuss and disseminate results from the pilot studies.

Our health agency partners include the KC Missouri Health Department (KCHD; provides clinic and community-based HIV testing services), KC CARE Health Center (a federally qualified health center; provides clinic and community HIV testing services and linkage to care services), and Kansas University (KU) JayDoc Clinic (provides clinic and community-based health services by supervised medical students). For the clinical trial, health agency partners provide HIV testing, counseling services, and testing results to all persons seeking HIV testing onsite at each participating church and their outreach ministries. Additionally, KC CARE assists the KCHD with testing services and provides a linkage to care staff member to be onsite at all intervention churches’ HIV testing events. Linkage to care services include getting participants who test positive for HIV immediately into HIV care along with assisting individuals with getting insurance coverage, a medical home, and basic needs (e.g., housing, food, clothing) met.

In planning for the clinical trial, we unified our faith-based and health agency partnerships to create the KC FAITH Initiative Community Action Board (CAB), which includes more than 50 representatives from faith, health, community, and academic organizations and people with HIV.37 The CAB meets 4 to 5 times per year to review study progress, address challenges, assist in interpreting study findings, and plan next steps for the trial and our other faith-based studies. The CAB also assists in refining culturally-religiously tailored TIPS Tool Kit materials to ensure appropriateness and acceptability for use in AA churches.

Guiding Theoretical, Ecological and Community-Engaged Framework

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) was used to guide development of the study’s intervention components. TPB posits that behavioral intentions predict if a person will engage in a particular behavior, and attitudinal beliefs, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control influence intentions.38 The Social-Ecological Model guides delivery of the intervention components. It posits using multilevel intervention strategies to address overlapping influences of individual, social, organizational, and community level factors on the uptake/maintenance of behaviors. As barriers are removed and multilevel, supportive, capacity building mechanisms are established, behavior change becomes more attainable and sustainable.39 We combined the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Social-Ecological Model to form an overarching Ecologically-expanded Theory of Planned Behavior framework for HIV testing intervention development, delivery, and scalable dissemination through AA churches.

Research Design and Rationale

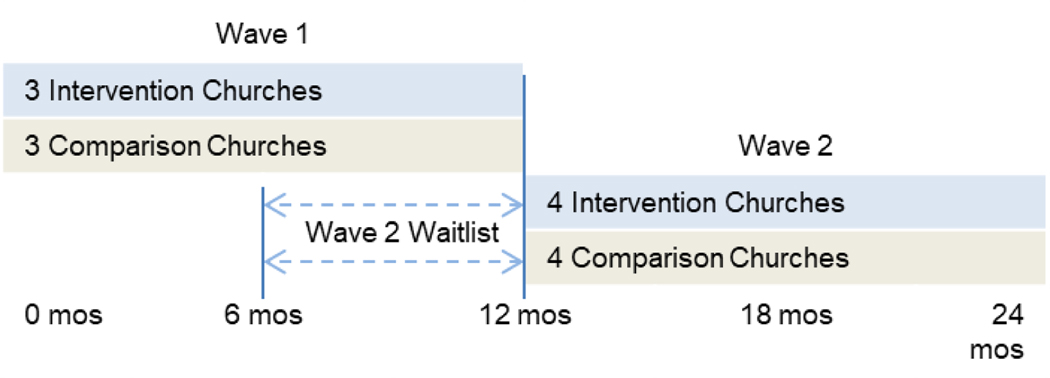

Our primary outcome is self-reported receipt of HIV testing (tested vs. not tested) during the study period with church members and community members at six and twelve months. Additionally, objective data on the aggregate number of HIV tests given at each participating church is provided by the KCHD. We are using a two-arm, cluster randomized design with 14 churches (seven intervention and seven standard information control churches) matched on church membership size and denomination. The TIPS intervention arm receives culturally and religiously tailored materials/activities packaged in the TIPS Tool Kit to promote and encourage HIV screening (e.g., pastoral sermon guides, responsive readings, brochures, testimonials, text/email/phone messages) as well as tool implementation training, and access to HIV testing and linkage to healthcare services during church events – primarily Sunday church services, and community outreach events. The control arm receives standard HIV education and access to HIV screening services at their church or community outreach events. To optimize study management, six churches participate in study activities in Wave 1, and eight churches participate in Wave 2, as shown in Figure 1. Churches were randomly assigned to intervention or standard information arms within their Wave. The eight Wave 2 churches are waitlisted and complete 2 baseline surveys (baselineA and baselineB). BaselineB surveys are completed six months after baselineA surveys. This “no-activity” time period was established to simulate a pure control arm with no studies activities, including no church-based HIV testing, and to optimize use of project resources. After completing baselineB surveys, the eight Wave 2 churches cross over to begin participation in their respective assigned study arm’s activities, as shown in Figure 1. All participating churches hold three HIV testing events. Additionally, after completion of control arm activities, all control arm churches receive the TIPS training, manual, and HIV Tool Kit along with technical assistance to implement the TIPS intervention.

Figure 1.

Study Design and Timeline

Church sites and participants

Churches.

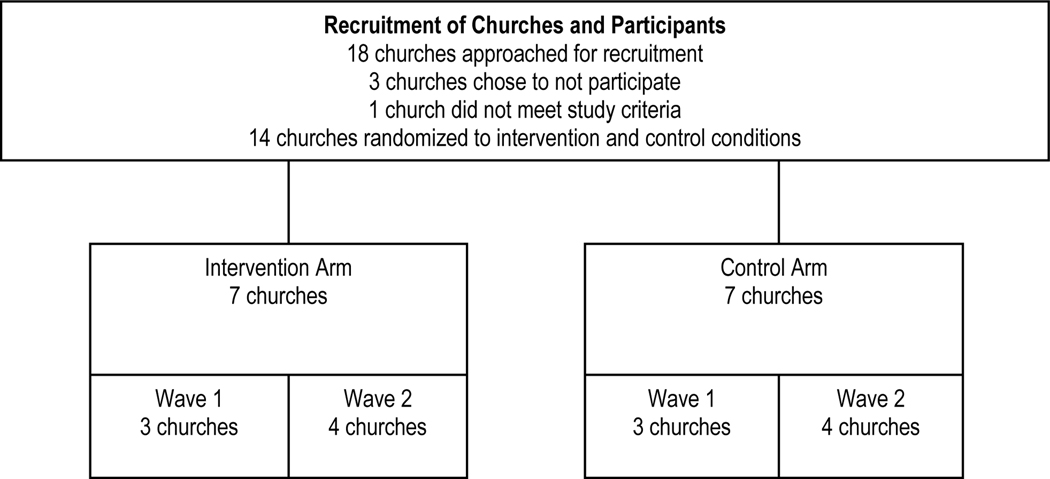

Participating churches in the KC MO and KC KS urban areas were recruited with assistance from CCON. Church recruitment began with interested church leaders attending one of four study informational group meetings. These meetings were followed by in-depth individual meetings with interested senior pastors and the study’s lead investigator and project director in order to provide more information and determine whether their church met selection criteria. This criteria included: a) a minimum of 150 adult church members who regularly attended Sunday services; b) an active church outreach ministry (e.g., food/clothing pantry, social services, daycare) that served a minimum of 50 adult community members who receive services at least four times per year; c) commitment from the pastor to assist in study activities; d) commitment from 2 to 3 church health liaisons (CHLs), identified by their pastor to assist with the study to coordinate and implement all study activities in their respective arm; and e) pastor and CHL’s commitments to attend trainings and booster meetings. All participating churches agreed to hold 3 HIV testing events over a 12-month period. Of the 18 churches approached, 2 churches met study criteria but decided to not participate due to competing interests, and another church did not participate since it did not meet study criteria and had looming church repairs.

Each of the recruited church’s senior pastor signed a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) to agree to participate in the study. The MOAs included roles and responsibilities of participating churches and the study team. The MOAs also included church selection criteria. Of the 14 churches, prior to study launch, 1 church determined that they were not ready to participate in the study after signing the MOA and was subsequently replaced with 2 smaller sister churches that joined together as 1 church to meet study criteria and participate in the study. The 14 churches were randomized to participate in the study with 7 intervention and 7 control churches, as shown in Figure 2. Churches were randomized by the study statistician using a computer-generated randomization sequence. All participating churches receive: a) $3,000 for assisting in study delivery and recruitment-retention activities; b) $1,600 in stipends for CHLs coordinating study activities; and c) up to $1,200 in technology upgrades (e.g., phone message system for HIV testing and survey event reminders), for a total of $5,800 per church. Monetary reimbursements are disbursed to churches after completion of the baseline survey and every six months as they complete their designated study activities. All churches also receive promotional items (t-shirts and banners).

Figure 2.

Church Recruitment and Randomization

Participants.

Impact is tracked among church and community member participants from the 14 churches. Church and community members are recruited by study team members. Recruitment activities include having the lead investigator and project director provide study information during/after church services. Community members are recruited similarly during churches’ outreach ministries (e.g., food/clothing pantries, social services, afterschool programs, church-community health ministry programs). Participants are screened using self-report to meet the following criteria: a) aged 18 to 64; b) willing to participate in three surveys after church services; c) willing to provide contact information (i.e., 2 phone numbers, mailing/email address, phone numbers for 2 persons with whom they have ongoing contact; and d) regularly attend church (at least once a month) or use church outreach services (at least four times per year). Prior HIV testing is not an exclusion for participation.

All participant enrollment occurs prior to the start of any treatment group activities. Participants complete surveys at baseline (two baseline surveys for Wave 2 participants), 6, and 12 months. They receive $25 for completing baseline surveys (including $25 for additional waitlist baseline for Wave 2 participants), $25 for 6-month surveys, and $30 for 12-month surveys. Participants create unique study ID codes that they can reproduce at each survey event by answering a series of questions (e.g., last letter of mother’s first name). This protection was requested by faith leaders to increase confidentiality and was used in pilot studies.35 Study procedures were approved by the University of Missouri-Kansas City institutional review board.

Partner and pastor/church health liaison training

Training of healthy agency partners.

Prior to the start of the study, the study team held a training meeting with the full KCHD communicable disease staff and KC CARE linkage to care staff to discuss the pilot study lessons learned, procedures for conducting church-based HIV testing for the current study, and AA church culture. Also, a planning meeting was held with the KCHD and KC CARE supervisory staff to discuss study procedures and adapt each organization’s relevant forms and procedures to ensure efficient coordination and implementation of the testing events onsite at participating church locations. In the training meetings, health agency partners expressed the importance of testing for other STDs along with HIV in participating churches. These discussions resulted in decisions to make STD information and testing (chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis) available as a value-added service with the church-based HIV testing services. As guided by these meetings, all study HIV testing events are held onsite during church services (primarily on Sunday morning/afternoons) and community outreach ministry activities. Study staff, CHLs, and pastors are not involved in providing these services in any manner. All HIV testing, counseling, feedback of results, and linkage to care services are solely provided by health agency partners. However, study staff provide ongoing technical assistance to CHLs and health agency partners in coordinating the HIV testing events.

Training of pastors and CHLs.

To ensure intervention fidelity, pastors and CHLs are trained in their respective study arm’s implementation procedures, as shown in Table 1, using a scripted, study implementation manual. They are also trained on intervention background topics to better prepare them to address questions from church and community members. Health agency partners attend these trainings to meet pastors/CHL teams, serve as a resource, and answer any questions church teams may have about HIV testing procedures. The trainings are also used to plan and schedule delivery of respective study arm activities in targeted church services and ministries. These activities include drafting an implementation timeline and discussing implementation strategies specific to the CHL’s respective study arm. For instance, CHLs in the intervention arm are trained on how to use each TIPS tool item/activity and to promote HIV testing through all church communication outlet levels (e.g., individual-interpersonal, ministry groups, church services, community). They then determine and plan how to incorporate delivery of tools within existing church activities based on their church calendar. CHLs in the control arm are trained on use of the standard information materials and how/when to deliver them, including limits in delivery of these materials. All CHLs are trained on how to report their study arm’s implementation activities via an online data tracking tool to assist in evaluating study arm implementation feasibility and reach regarding the multilevel components. Four formal trainings are included: 2 trainings (1 group and 1 at the individual church) prior to and 2 trainings during the 12-month intervention phase. Additionally, booster trainings and technical assistance are provided with each church, as needed. CHL’s receive user-friendly study manuals including samples of all toolkit materials to be used in their respective study arm.

Table 1.

Pastor and Church Health Liaison Training Curriculum Per Treatment Arm

| Core Curriculum Components | TIPS | Standard Information |

|---|---|---|

| Study and HIV background | • What is TIPS? • History of TIPS • Why engage the church in HIV education and testing? • What is HIV/AIDS? • How is HIV transmitted? • How can we reduce HIV in the African American community? • How can TIPS benefit your church? |

• Study background information • What is HIV/AIDS? • How is HIV transmitted? • How can participating in this study benefit your church? |

| Implementation of study arm activities | • Role of church health liaison in implementing the TIPS intervention • Project implementation timeline • HIV testing events coordination and tailored promotion of church-based testing •TIPS HIV Tool Kit materials • Tools description • Tools delivery scheduling and distribution |

• Role of church health liaison in implementing standard arm activities • Project implementation timeline • HIV testing events coordination and scripted non-tailored/limited promotion of church-based testing • Standard HIV educational materials scheduling and distribution |

| Intervention evaluation | • Survey events coordination • Implementation data tracking on delivery of TIPS HIV Tool Kit materials • Post-study focus groups |

• Survey events coordination • Implementation data tracking on standard HIV educational materials |

Description of Intervention and Control Arms

Intervention Arm.

Each intervention church appoints at least two CHLs who deliver TIPS intervention activities and organize their church-based HIV testing events. Intervention churches hold a TIPS Kick-off event where a sermon, a responsive reading, and two church bulletins are delivered along with the first HIV testing event. After the Kick-off, liaisons deliver one to two Tool Kit materials/activities per month through targeted multilevel church activities, as shown in Table 2, with a minimum of 24 tools over 12 months. Two additional HIV testing events are also conducted (one for community members). HIV testing events are open and free to all persons who seek screening, including non-study members. Delivery of intervention components coincide with existing, multilevel church activities through: a) a communitywide initiative; b) churchwide services, c) inreach/outreach ministry groups; and d) individual level activities over 12 months. Details on the multilevel intervention activities are described below and are outline in Table 2.

Table 2.

Intervention and Control (Standard Information) Group Activities

| Intervention Group Activities (via TIPS Religiously-tailored HIV Tool Kit materials)23 | Standard Information Group Activities (via Standard Non-tailored HIV materials) |

|---|---|

|

Community: • HIV testing events • HIV testing event activities coordination checklist • Participation in citywide TIPS activities |

Community: • HIV testing events |

|

Churchwide Services: • HIV testing events • Linkage to care services • HIV testing event activities coordination checklist • Pastoral sermons (sermon and comment guides) • Pastoral modeling of receipt of testing • Responsive readings • Church bulletin inserts and brochures • Posters, banners, and church fans • Flyers |

Churchwide Services: • HIV testing events • HIV testing dates printed in church program bulletins • Brochures |

|

Ministry Groups (inreach and outreach): • HIV education (seminars and games) • HIV testing printed/video testimonials and facilitator guides |

Ministry Groups (inreach and outreach): • Brochures |

|

Interpersonal/Individual: • Print materials (brochures, bible bookmarks, resource list, HIV risk checklist) • HIV testing event voice message/text reminders • Individual meetings with HIV service providers (counseling, testing results, linkage to care) |

Interpersonal/Individual: • Brochures and resource list • Individual meeting with HIV service providers (counseling and testing results) |

Community level activities.

Using TIPS HIV screening event checklist/forms to request specific HIV testing services (e.g., screening dates, whether condoms can be distributed), CHLs coordinate an HIV testing event for the community by notifying KCHD and KC CARE. To increase communitywide opportunities for HIV testing and impact, CHLs participate in quarterly TIPS initiative meetings with other collaborating partners.

Provision of HIV testing and linkage to care services.

HIV testing and sexual/drug risk counseling are provided by appropriately trained KCMOHD and KC CARE staff. Both health agency partners use OraQuick® Advance, a diagnostic test that: is approved for oral fluid, plasma, and fingerstick specimens; provides accurate results in 20 minutes with over 99% accuracy; and is ideal for both clinical and non-clinical settings.40 Standard procedures for positive result confirmation (blood test processed by state lab) and follow-up counseling are followed. To ensure privacy/confidentiality of counseling and testing procedures, test results and counseling at church sites are held in private rooms, which all churches are required to have available. Free HIV testing services are also provided at KC CARE and KCHD clinics for church and community members who do not want to get tested in church settings. All health partners’ reports on all HIV testing results are sent to the KCHD following their established procedures. KCHD and KC CARE conduct follow-ups with study participant and nonparticipant church and community members on their results as needed. KCHD and KC CARE report total number of persons tested/receipt of results and de-identified results with demographics (e.g., age, gender) per church to study staff. Individual participants’ results are not shared with church leaders, members, or study staff.

KC CARE linkage to care services are available onsite to anyone in need immediately after receipt of testing, and with additional counseling and support for anyone in participating churches who newly (or previously) test positive for HIV. Available linkage to care services include maintaining contact until individuals are engaged in treatment and linked to a case manager, providing 90 days of intensive case management, serving as health advocates by assisting with attaining health insurance and attending health pr"ovider appointments with clients, and providing linkages to community resources (e.g., food, housing, transportation).

Churchwide services level.

Churchwide activities begin with the TIPS Kick-off event described above. During subsequent targeted church services (e.g., Sunday morning, bible study), CHLs coordinate delivery of 1 to 2 tools per month (see Table 2), primarily with ushers, the media team, and the church secretary to ensure tools are widely delivered to congregants in church services. Pastors deliver sermons and comments from the pulpit with assistance from Tool Kit materials (e.g., sermon, comment guides) to promote and normalize HIV testing and reduce HIV risk and stigma. They do so from the perspective of HIV being a chronic disease deserving compassion similar to other chronic diseases and as a health disparity needing church and community attention and awareness. They also deliver motivating HIV testing reminders from the pulpit at two weeks and one week prior to HIV testing event. At opportune times, pastors deliver a brief message to community members where/when appropriate (e.g., parents’ meetings, before prayer at a free meal event) to promote testing. Two church service-based HIV testing events are held (community members are also be invited): one during the Kick-off and one during a special Sunday service (e.g., World AIDS Day, Family and Friends Day). CHLs use TIPS Tool Kit forms for HIV testing event requests to coordinate church testing events with health agency partners. They also use planning checklist tools (e.g., pastor role modeling receipt of HIV screening in front of congregants; HIV screeners explaining screening process while testing pastor; pastor encouraging everyone/celebrating number of persons tested throughout service to reduce possible rumors about persons getting tested) to coordinate delivery of TIPS activities with pastors, ushers, and media team to encourage HIV testing.

Ministry Group (Inreach and Outreach) level.

HIV health educators from partnering organizations conduct HIV education seminars with church leaders to further enhance their knowledge about the disease, transmission, risk reduction, and testing. Tool Kit HIV education seminar materials (e.g., testimonial videos, printed role model story testimonials, HIV education games [e.g. HIV Wheel of Awareness, HIV Testing Jeopardy]) and facilitator guides are used to assist in conducting seminars. In all outreach contexts, every effort is made to expose community member participants to the full array of church-wide intervention materials along with church pastors modeling receipt of HIV testing at appropriate times during outreach ministry group events (e.g., during daycare/church school parents’ meetings, prior to blessing food at food pantry events).

Interpersonal/Individual level activities.

Church and community members receive self-help materials including: HIV education/risk reduction and myths/facts brochures and church bulletins tailored to gender and age, videos of male and female testimonials that encourage HIV testing messages, and a brief (<20 minute) video on HIV risk reduction and importance of HIV screening for AAs hosted by a well-known AA male pastor from the Kansas City metro area. Automated text messages with motivating HIV testing event reminders to church and community members are delivered via churches’ telephone messaging systems to increase intentions to seek HIV testing. These reminders are sent two weeks and one week prior to each of the testing events at their church.

Standard Information Arm.

Control churches receive standard multilevel HIV education information similar in type to those being provided to the intervention churches. These churches receive: a) non-tailored project materials (e.g., brochures, announcements in church bulletins, flyers) collected from health organizations and b) standard, non-tailored HIV testing events coordinated by CHLs.

To maintain standard information group fidelity, the fidelity plan (described below) is followed with this arm’s church pastors and CHLs. These churches will receive TIPS training and all HIV Tool Kit materials after the completion of 12-month assessments.

Fidelity Plan

Treatment fidelity is guided by recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium Treatment Fidelity Workgroup on study design, training providers, delivery of treatment, receipt of treatment, and enactment of treatment skills using.41 Treatment fidelity in this study is addressed using: a) standardized church leader group trainings and a scripted study manual on study design/implementation (e.g., dose, intensity, and quality of treatment group activities) specific to each research arm; b) technical assistance and pre-study and booster trainings with structured practice/role play and the same trainers to minimize/correct treatment delivery drift with church leaders; c) direct observation guides/checklists (aligned with the manual) to assess dose/intensity/quality/attendees of implemented activities in designated church services/ministries and HIV testing events; d) an online documentation system for church leaders to monitor their implementation activities; and e) pre-posttest HIV testing and process measures on intervention exposure and study satisfaction to assess receipt, quality, and access to treatment activities with study participants.

Technical Assistance

The study team provides ongoing technical assistance via trainings/meetings with CHLs. Much of the technical assistance is focused on planning implementation of Tool Kit materials/activities (nontailored materials for standard information group), survey events, and HIV testing events. We conduct monthly reviews with CHLs on their study arm’s implementation activities, send monthly email reminders about planned upcoming activities to ensure study implementation fidelity efforts are on track, and are available to pastor and CHLs to answer questions and assist in problem solving study-related issues.

Measures

All survey measures (self-reported) are widely used and well-validated through use in our prior studies and their demonstrated psychometric properties. Primary and secondary outcome measures are assessed at baseline, 6 and 12 months. As mentioned earlier, Wave 2 churches will complete two baseline surveys (baselineA and baselineB) and thereby complete a total of 4 surveys with the final survey completed 12 months from baselineB.

Primary outcome measures.

Self-reported receipt of HIV testing (ever, last 12 months, most recent) is measured using items adapted from national surveys and our pilot studies on participants’ HIV screening behaviors and beliefs.35,36,42 These measures include items on receipt of HIV screening (ever, past year, past 6 months), estimated date when last tested, reasons tested, facilitators/barriers to testing, where testing was received including non-church testing sites, and factors motivating receipt of church-based testing (e.g., pastoral message, friend tested, free HIV test), and other STD screenings. Objective aggregate HIV testing data is provided by health agency partners and include total number of individuals tested/receiving results, demographics (e.g., age, gender), and number of HIV-positive tests per church. HIV test results are not linked to individual participants or to their self-reported data due to pastors strongly discouraged this approach.

Secondary outcome measures.

HIV sexual risk behaviors are assessed on condom use, number and gender of partners, and vaginal, oral, and anal sex (ever, last 12 months) adapted from the sexual practice items from the Wisconsin HIV Prevention Evaluation Work Group,43 and on history of STD (chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis) testing (ever, last 12 months, most recent).

Potential Mediators.

Several self-report measures are used to assess potential mediating variables that are presumed to be affected by our interventions. Based on feasibility and pilot study findings, TPB measures (attitudes, subjective norms, perceived control, and behavioral intent) related to HIV testing were developed in accordance with detailed guidelines provided by Fishbein et al.44 Attitudes are assessed regarding church-based HIV screening (e.g., “Knowing my HIV status is important to my health true”). Subjective norms are assessed regarding social pressure to comply with HIV screening and personal motivation to comply with specific referents’ (AA church, pastor, church members, family, friends, doctors) opinions (e.g., “My friends think I should/should not get screened for HIV” and “When it comes to getting screened for HIV, I do/do not want to do what my friends think I should do”. Perceived behavioral control is assessed to ascertain beliefs and perceived power to get screened for HIV (e.g., “My church is likely/unlikely to offer screening [control belief]” and “Having screening available at this church will make it easy/difficult to access screening [perceived power]”). Behavioral intentions to get screened for HIV (e.g., “It is likely/unlikely I will get screened for HIV this year.”) are also assessed. HIV stigma is measured with items adapted from national HIV stigma studies45,46 (e.g., “If you were going to be tested for HIV, how concerned would you be that you might be treated differently or discriminated against if your test results were positive for HIV?”). HIV knowledge is measured with items addressed in the intervention arm and adapted from the HIV Knowledge Questionnaire47 (e.g., “You can get HIV from a mosquito”).

Potential Moderating Variables:

Other HIV-related risk factors (e.g., trading sex for drugs, sex under the influence of substances, homelessness, incarceration, STD diagnoses, drug use) are assessed (ever, last 12 months).43 Religiosity is measured with items from the Religious Background and Behavior survey on participants’ engagement in church activities (e.g., prayed, meditated, attended a worship service) and religious identity (e.g., atheist, spiritual, religious; last 12 months).48 Receipt of health screenings (e.g., blood pressure, cholesterol, Pap test) and health care (e.g., annual exams) are also assessed (ever, last 12 months). Demographics including age, gender, sexual orientation, relationship status, income, education, insurance, and housing status are collected.

Process Evaluation Measures.

Intervention exposure measures (last 6 months, last 12 months) include items on participants’ exposure to each intervention component (e.g., printed brochures and bulletins, pastoral sermons, responsive readings, HIV testing testimonials, HIV education seminar, HIV testing events). Participant satisfaction measures (last 6 months, last 12 months) assess satisfaction with various aspects of the study (e.g., “I felt confident that my test results would remain private”). CHLs use an online documentation system to track their church’s implementation activities and costs. The system allows CHLs to efficiently report on: number and type (e.g., young/older adult, women, men) of persons exposed to their church’s respective study arm implementation activities; interactions with health agency partners, costs, time spent, and communication and technology strategies used; community partners’ support; qualitative feedback). Research team members check these data monthly for accuracy and completeness. The research team collects similar information (e.g., number of attendees, member feedback, mood of the setting, sermon content, tools used) by attending TIPS-designated church services, HIV seminars, and HIV testing events using direct observation fidelity guides/checklists. Post-study focus groups with church leaders and church/community members are conducted with intervention CHLs, church leaders, and church and community members to inquire about their satisfaction with the study procedures and materials, church challenges and facilitators associated with delivery the HIV intervention study, acceptability of receipt of church-based HIV testing and protection of privacy, personal and/or community barriers to receiving church-based HIV testing, suggestions for improving the feasibility of disseminating and implementing the intervention with AA churches, and their intentions to carry on HIV screening activities after the end of the grant with the support of technical assistance.

Power analysis

Sample size calculations were based on: a) change in past year expected HIV testing rates (primary outcome) from baseline to 12-month assessment and b) a group randomization and matched pair design based on a range of 5 to 7 paired churches (10 to 14 churches). To calculate power, we used Hayes’ approach for cluster randomized trials through the specification of a coefficient of variation (CV) of cluster rates, which defines relative variation between clusters.49 We used our TIPS pilot study findings as the basis of our analysis (there are no other known studies on pre-post HIV testing rates with AA participants nested in churches). Based on our CV estimates, we would have sufficient power with 10 to 12 churches (110 baseline participants per church; ≥65 participants at 12 months) to achieve 84% to 91% power, respectively, to detect this difference with a Type I error rate of 5%; these power calculations are conservative. Therefore, of the 70 church and 40 community member recruitment goal per church, we conservatively estimate 70% and 40% retention rates, respectively, to achieve a final sample of ≥65 participants per church at 12 months to adequately power the proposed study. However, we included 14 churches, 7 churches per arm, to protect power against possible church attrition; therefore establishing an overall recruitment goal of 1,540 participants.

Data analyses

Our primary outcome is self-reported receipt of HIV testing (tested vs. not-tested) at 12 months. We will also examine outcomes at 6 months. All primary analyses on receipt of HIV testing will use intent-to-treat analyses and will code participants lost to follow-up as “nontesters.” Churches are the unit of randomization, and participants nested in churches will be the level of analysis. Therefore, differences between intervention and standard information groups will be analyzed using random effects logistic regression to account for the clusters and the pairing, or matching, of churches.50 Multilevel, multivariate models will include fixed-effect terms for experimental condition and potential mediators and moderators, as well as random effect terms for church nested in treatment condition and individual nested within church. Adjusted odds ratios for HIV testing (and confidence intervals) will be computed for mediators/moderators. Other covariates will be added as indicated by univariate analyses conducted on baseline data. We will use R and SAS statistical software generalized estimating equations and generalized linear mixed modeling for data analyses to determine if there is a difference in HIV screening rates over time between intervention and standard information groups with/without adjusting for covariates.51-52

Mediation analyses will examine to what extent possible intervention effects on HIV testing might be explained by potential mediators, including TPB-based variables (attitude, normative beliefs, behavioral control, intentions) and other covariates (HIV stigma, HIV knowledge, intervention exposure). Effects of potential moderators’ ability to modify the strength/direction of the potential causal relationship will be tested using interaction tests in a multifactorial model.

Discussion

This is the first study to use a clustered, randomized controlled design powered to examine the effect of an HIV testing intervention in AA churches on HIV testing rates with church-populations. Unique to this study, we have included community member participants served through participating churches’ outreach ministries (e.g., food/clothing, shelter, and social service programs) to demonstrate the wide reach of the churches with community populations that may be at increased risk for HIV. This approach can assist in achieving National HIV/AIDS Strategy goals in expanding the reach of HIV awareness and testing in ethnic minority communities.17

We are using a CBPR approach that fully engages faith leaders in every aspect of the research process. Faith leaders established the research agenda, assisted the research team in developing the religiously-tailored TIPS Tool Kit, and are trained to implement the intervention and assist in evaluating intervention implementation. One of the goals for TIPS’ religious-tailoring was to have the tools fit into the natural activities that happen in most church settings (e.g., pastors preaching sermons, ushers handing out church bulletins, members call-response responsive readings, persons giving their testimonies about their lived experiences, ministries playing games to convey educational information in a fun way to makes it easier to talk about topics that have not traditionally been talked about in church).23,27,35 This strategy is consistent with prior church-based HIV testing interventions,34–35,53–54 and is intended to meld the intervention into the existing church communication and activities infrastructure that exists in most AA churches to increase exposure, acceptability, and sustainability. Many of the religiously-tailored tools, including the pastoral sermons guides and comments, testimonials, text messages, and educational games, were created by church leaders.23 Faith leaders’ and CAB members’ engagement in these activities provided input on procedures and design of tools based on common AA church activities and context along with culturally-appropriate language, images, and narratives. TIPS intervention materials and activities were designed for acceptability among members and ease in delivery through existing multilevel church outlets. Use of a socio-ecological model and the TPB may assist in increasing members’ exposure to intervention components and in shifting church and community members’ attitudes, normative beliefs, behavioral control, and intentions regarding getting tested for HIV, as was found in the pilot study.35 Additionally, studies indicate the importance of cultural appropriateness for adoption, appropriateness, and sustainability of health promotion interventions and the uptake and maintenance of health behaviors.55–57

Also unique to this study, the HIV testing events take place at participating during Sunday morning church services and during community outreach ministry events. This approach was recommended by faith leaders to increase access to HIV testing services, reduce HIV-related stigma, and normalize receipt of HIV testing. Key to the implementation of this component is having church-based HIV testing also coincide with church services, including Wednesday night bible study, special events such as “Family and Friends Day,” and ongoing community outreach services and special events. The tagline created by faith leaders to encourage testing in the TIPS intervention arm was “Take someone’s hand. Get tested together.” Also, HIV testing is free to anyone seeking testing, whether or not they are study participants.

Additionally, church-based HIV testing and distribution of non-tailored information is offered in control churches similar in ways previously offered in NCWP events when minimal uptake of HIV testing occurred. However, to simulate a control arm without any religiously-tailored/non-tailored promotion activities or church-based HIV testing, Wave 2 churches participate in a 6-month “waitlist” phase before crossing over to active participation in their assigned study arm. This design assists in managing resources in testing TIPS against a “control” condition while providing an opportunity to determine if any differences in uptake of testing are found based on tailoring and non-tailoring when church-based HIV testing opportunities are (and are not) available. Although HIV stigma is not a primary outcome for this study, the literature is replete with studies that indicate stigma is a key barrier to receipt of HIV testing. Therefore, the design of the intervention has taken this into consideration, and HIV stigma is being addressed, including in compassion and HIV testing promotion messages by pastors and toolkit materials, and assessed.

This study has potential to greatly inform the feasibility and impact of a religiously-tailored HIV testing intervention in AA churches but still has some limitations regarding its design and implementation. For example, the study primarily aims to examine rates of HIV testing, which aligns with CDC routine HIV testing recommendations.6 Therefore, it is not powered to assess other important HIV care continuum outcomes, such as engagement in care and treatment outcomes for persons who test positive. Also, churches have flexibility in choice and timing of delivery of most tools. This decision was made to more to understand church’s autonomous use of tools, and to also determine the relative impact of the tools and delivery dosage.

Given the many strengths of churches, which includes stable high church attendance among AAs, a focus on health and taking care of one’s body, and the availability of space to support health promotion programs, faith-based settings may be an ideal setting for health promotion programming. Also, many churches now have health ministries that are charged with implementing health promotion programming for their members and the community.30 As HIV continues to burden many countries around the world, church-based HIV awareness and testing interventions may be an important component in extending reach of national and international HIV prevention strategies. Therefore, providing AA churches with church-appropriate supportive tools and training to implement such interventions, including coordination of church-based HIV testing events with health agencies, could greatly enhance AA church reach and impact on HIV testing with their members and the community members they serve, and potentially with other HIV burdened populations worldwide.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the tremendous contributions of our faith and health organization partners and are truly grateful for the church leaders’ commitments to implement the TIPS project with their church members and community members served through their outreach ministries.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01MH099981].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2017. 2018; Vol 29. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

- 2.Dailey AF, Hoots BE, Hall HI, et al. Vital Signs: Human Immunodeficiency Virus Testing and Diagnosis Delays — United States. MMWR. 2017;66:1300–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandra A, Billioux VG, Copen CE, Balaji A, DiNenno E. HIV testing in the US household population aged 15–44: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 2006–2010. National Health Stat Rep. 2012;4(58):1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017: With special feature on mortality. Hyattsville, MD. 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data. 2018;23:No. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR. 2006;55:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wejnert C, Prejean J, Hoots B, et al. Prevalence of missed opportunities for HIV testing among persons unaware of their infection. JAMA 2018;319:2555–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen K, Berkley-Patton J, Shah B, Aduloju-Ajijola N, Bauer A, Bowe Thompson C, & Lister S (revise/resubmit). HIV risk and sociodemographic factors associated with physician-advised HIV testing: What factors are overlooked in African American populations? Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin T, Hicks C, Samsa G, McKellar M. Diagnosing HIV infection in primary care settings: missed opportunities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(7):392–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cope AB, Powers KA, Serre ML, et al. Distance to testing sites and its association with timing of HIV diagnosis. AIDS Care. 2016;28(11):1423–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy ME, Wilton L, Phillips G, et al. Understanding structural barriers to accessing HIV testing and prevention services among black men who have Ssex with men (BMSM) in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2014;8(5): 972–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gwadz M, Leonard NR, Honig S, Freeman R, Kutnick A, Ritchie AS. Doing battle with “the monster:” how high-risk heterosexuals experience and successfully manage HIV stigma as a barrier to HIV testing. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sionean C, Le BC, Hageman K, et al. HIV Risk, Prevention, and Testing Behaviors Among Heterosexuals at Increased Risk for HIV Infection — National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 21 U.S. Cities, 2010. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2014;63(14):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 U.S. dependent areas—2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(3):Part A. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2010_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_17_no_3.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gopalappa C, Farnham PG, Chen YH, Sansom SL. Progression and transmission of HIV/AIDS (PATH 2.0). Med Decis Making. 2017;37(2):224–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States 2010–2015. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-23-1.pdf.

- 17.White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020. Washington, DC: The White House; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The Black Church and the African American Experience. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pew Research Center. A religious portrait of African Americans. Washington, DC: Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. 2009. Available at http://www.pewforum.org/2009/01/30/a-religious-portrait-of-african-americans/]. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pew Research Center. America’s Changing Religious Landscape. Washington, DC: 2015. May. Available at: http://www.pewforum.org/files/2015/05/RLS-05-08-full-report.pdf.

- 21.Davis DT, Bustamante A, Brown CP, et al. (1994). The urban church and cancer control: A source of social influence in minority communities. Public Health Rep. 109;4:500–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, & Levin J. (2004). Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks: CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berkley-Patton J, Thompson CB, Martinez DA, et al. Examining church capacity to develop and disseminate a religiously appropriate HIV tool kit with African American churches. J Urban Health. 2013;90(3):482–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derose KP, Mendel PJ, Palar K, et al. Religious congregations’ involvement in HIV: A case study approach. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(6):1220–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agate LL, Cato-Watson DM, Mullins JM, et al. Churches United to Stop HIV (CUSH): a faith-based HIV prevention initiative. J Nat Med Assoc. 2005;97(7 Suppl):60S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berkley-Patton J, Bowe-Thompson C, Bradley-Ewing A et al. Taking It to the Pews: A CBPR-guided HIV awareness and screening project with Black churches. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(3):218–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffith DM, Campbell B, Allen JO, Robinson KJ, Stewart SK. YOUR Blessed Health: an HIV-prevention program bridging faith and public health communities. Pub Health Rep. 2010;125(1_suppl):4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whiters DL, Santibanez S, Dennison D, Clark HW. A case study in collaborating with Atlanta-based African-American churches: A promising means for reaching inner-city substance users with rapid HIV testing. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2010;7(1):103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pichon LC, Powell TW. Review of HIV testing efforts in historically Black churches. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2015;12(6):6016–6026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pichon LC, Powell TW, Ogg SA, Williams AL, Becton-Odum N. Factors influencing Black Churches’ readiness to address HIV. J Rel Health. 2016;55(3):918–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berkley-Patton J, Hawes SM, Moore E, et al. Examining facilitators and barriers to HIV testing in African American churches using a community-based participatory research approach. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(Suppl. 1):s277. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart JM, Thompson K, Rogers C. African American church based HIV testing and linkage to care: Assets, challenges, and needs. Culture Health & Sexuality. 2016;18(6):669–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derose KP, Griffin BA, Kanouse DE, et al. Effects of a pilot church-based intervention to reduce HIV stigma and promote HIV testing among African Americans and Latinos. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(8):1692–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berkley-Patton J, Bowe Thompson C, Moore E, et al. Feasibility and outcomes of an HIV testing intervention in African American churches. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(1):76–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berkley-Patton J, Bowe Thompson C, Moore E, et al. An HIV testing intervention in African American churches: Pilot study findings. Annals Beh Med. 2016;50(3):480–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berkley-Patton J, Thompson CB, Bradley-Ewing A, et al. Identifying health conditions, priorities, and relevant multilevel health promotion intervention strategies in African American churches: A faith community health needs assessment. Eval Program Plann. 2017;67:19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ajzen I The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bronfenbrenner U The ecology of human development: Experiments by design and nature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenwald JL, Burstein GR, Pincus J, Branson B. A rapid review of rapid HIV antibody tests. Cur Infect Dis Rep. 2006;8:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellg AJ, Resnick B, Minicucci DS, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psych. 2004;23(5):443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2009. 2011. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2009report/pdf/cover.pdf.

- 43.Wisconsin HIV Prevention Evaluation Work Group. Behavioral risk assessment tool (BRAT). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/evaluation/health_depts/guidance/strat-handbook/pdf/Appendix87.pdf.

- 44.Fishbein M, Triandis HC, Kanfer FH, et al. Factors influencing behavior and behavior change In Baum A, Revenson T, Singer J (Eds.). Handbook of Health Psychology. 2001;3–18. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herek GM, Capitanion JP, Widaman KF. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1991–1999. Am J Pub Health. 2002;92(3):371–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herek GM. AIDS and stigma in the United States. Am Behav Sci. 1999;42(7):1130–1147. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carey MP, Schroder KE. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV knowledge questionnaire (HIV-KQ-18). AIDS Educ Prev. 2002:14;174–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. A measure of religious background and behavior for use in behavior change research. Psych Addict Behav. 1996;10(2):90. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayes RJ, Bennett S. Simple sample size calculation for cluster-randomized trials. Int J Epidem. 1999;28(2):319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. A random-effects ordinal regression model for multilevel analysis. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):933–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: : the R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. ISBN: 3–900051-07–0. Available at http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 52.SAS Institute Inc 2013. SAS/ACCESS® 9.4 Interface to ADABAS: Reference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wingood GM, Lambert D, Renfro T, Ali M, DiClemente RJ. A Multilevel Intervention With African American Churches to Enhance Adoption of Point-of-Care HIV and Diabetes Testing, 2014–2018. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S2):S141–S144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Payán Denise D., Flórez Karen R., Bogart Laura M., Kanouse David E., Mata Michael A., Oden Clyde W. & Derose Kathryn P. (2019) Promoting Health from the Pulpit: A Process Evaluation of HIV Sermons to Reduce HIV Stigma and Promote Testing in African American and Latino Churches, Health Communication, 34:1, 11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tobin K, Kuramoto SJ, German D, et al. Unity in diversity: results of a randomized clinical culturally tailored pilot HIV prevention intervention trial in Baltimore, Maryland, for African American men who have sex with men. Health Educ Behav. 2012;40(3):286–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bogart LM, Mutchler MG, McDavitt B, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Rise, a Community-Based Culturally Congruent Adherence Intervention for Black Americans Living with HIV. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(6):868–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]